Abstract

Introduction

An unmet burden of surgical disease exists worldwide and is disproportionately shouldered by low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). As the field of global surgery grows to meet this need, ethical considerations need to be addressed. Currently, there are no formal guidelines to help inform relevant stakeholders of the ethical challenges and considerations facing global surgical collaborations. The aim of this scoping review is to synthesise the existing literature on ethics in global surgery and identify gaps in the current knowledge.

Methods

A scoping review of relevant databases to identify the literature pertaining to ethics in global surgery was performed. Eligible articles addressed at least one ethical consideration in global surgery. A grounded theory approach to content analysis was used to identify themes in the included literature and guide the identification of gaps in existing literature.

Results

Four major ethical domains were identified in the literature: clinical care and delivery; education and exchange of trainees; research, monitoring and evaluation; and engagement in collaborations and partnerships. The majority of published literature related to issues of clinical care and delivery of the individual patient. Most of the published literature was published exclusively by authors in high-income countries (HICs) (80%), and the majority of articles were in the form of editorials or commentaries (69.1%). Only 12.7% of articles published were original research studies.

Conclusion

The literature on ethics in global surgery remains sparse, with most publications coming from HICs, and focusing on clinical care and short-term surgical missions. Given that LMICs are frequently the recipients of global surgical initiatives, the relative absence of literature from their perspective needs to be addressed. Furthermore, there is a need for more literature focusing on the ethics surrounding sustainable collaborations and partnerships.

Keywords: surgery, qualitative study, review, public health

Key questions.

What is already known?

There is a significant need for equitable access to safe and timely surgical care worldwide, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries.

Academic interest and participation in global surgery is growing.

No overarching guidelines on the ethical practice of global surgery exist.

What are the new findings?

The current literature on ethics of global surgery focuses on four domains: clinical care, education, research and collaborations.

Most literature published focuses on the ethics of direct patient care only.

The majority of literature published comes from authors in high-income countries and there is little original research on the topic.

What do the new findings imply?

There is a need for original research and the perspectives of authors from low-income and middle-income countries when discussing the ethics of global surgery.

The scope of ethics of global surgery should encompass domains beyond clinical care and delivery.

An ethical framework for global surgery should be pursued with significant and meaningful involvement from low-income and middle-income country authors.

Introduction

Global surgery, the ‘enterprise of providing improved and equitable surgical care to the world’s population’, has garnered increasing attention over the last two decades.1 A number of academic and policy developments, most significantly the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery, have drawn attention to the staggering burden of surgical disease harboured by low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). An estimated of 5 billion people worldwide lack timely access to safe and affordable surgical care, and 143 million surgical procedures worldwide are required to make up this shortfall.2 The international academic community has responded to this healthcare crisis with increasing participation in global surgical initiatives and collaborations, as evidenced by an increasing number of publications on the topic,3 the development of academic positions in global surgery,4 the growth of formalised education programmes in international surgery,5 and the recognition of international surgical electives by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.6 Despite this growing attention to the field of global surgery, little has been published to critique or guide the ethics of global surgical endeavours.

While history has shown a preponderance of short-term medical service trips for participants from high-income countries (HICs) to travel to low-income countries, there is a lack of quality evidence to support the effectiveness of these initiatives.7 Furthermore, global health has been moving instead towards a focus on sustainability through bilateral educational exchanges, reciprocal partnerships and systems-level interventions.8 It follows then, that global surgery should also be evaluated and conducted in a manner that ensures sustainability and an appropriate transfer of knowledge and skill. However, little is known about the ethics of transnational global surgical endeavours and whether they differ significantly from ethical considerations in a broader global health discourse. Part of this evaluation includes understanding and addressing the ethical challenges that may be unique to global surgery. The overall aim of this scoping review is to synthesise the existing literature related to ethical challenges and considerations in global surgical partnerships involving HICs and LMICs. The literature has been analysed for its thematic content and gaps in the literature identified. This analysis provides insights into the ethical issues that may be encountered in global surgical partnerships and may serve as a springboard for the future development of an ethical framework to guide the field of global surgery as it matures.

Methods

The framework for scoping reviews developed by Arksey and O’Malley9 was used to conduct this review. This framework consists of five stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) data charting and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. This method was chosen because it allows for a broad assessment of the available literature, easy replication of the search strategy, transparency through the process and good reliability of the study findings. Each step is described in further detail below.

Identifying the research question

This scoping review focused on mapping the available literature that pertains to ethical principles in the global surgery. The study question was: What are the ethical considerations reported in the current literature to guide the practice of global surgery?

Identifying relevant studies

To identify relevant studies, a systematic search of the following databases was conducted: PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. No restrictions were placed on date, but studies were restricted to the English language. A wide definition of key words was used to identify a broad range of articles for potential inclusion. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used were: Ethics, Morals, Specialties Surgical, Developing Country and Global Health. MeSH terms used varied slightly depending on the database being queried. Keywords used included: ‘global surger*’, ‘global health’, ‘low and middle income countr*’, ‘lmic’, ‘ethic*’, ‘moral*’ and ‘developing countr*’. A hand search of the reference lists of identified articles was also undertaken. No restrictions were placed on publication type. A full example of the search strategy is available in online supplementary file 1.

bmjgh-2020-002319supp001.pdf (13.6KB, pdf)

Study selection

A total of 4865 references were identified from the six databases searched in November 2018. After the removal of duplicates (1542), 3353 studies were screened. Screening was completed in two stages: (1) screening by title and/or abstract and (2) full-text screening. Two reviewers screened records at each stage, with a third resolving conflicts. Studies describing general medical ethics without a surgical context, lacking a global perspective and those focusing on strictly military or humanitarian crisis medicine were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they focused on advanced reproductive technologies, female genital mutilation, abortion and transplant tourism. Articles were included if they addressed one or more ethical considerations within the context of global surgery. When deciding which articles to exclude, an effort was made to focus on ethical issues pertaining to the practice of global surgery itself. The exclusion list does contain major issues of ethical concern, but the ethical considerations involved are much broader than the practice of global surgery and would require a level of ethical analysis that is outside the scope of this project. A repeat search was run in August 2019 to include studies published between October 2018 and August 2019 prior to manuscript submission, which identified an additional 512 studies. After removal of duplicates of this repeat search, 265 studies were added to screening for a total of 3618 studies screened.

Charting the data

A standard set of information was then collected from each of the studies identified for inclusion using a data charting form created for this review in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Santa Rosa, California, USA; 2016). The country of study origin and type of publication were recorded. Information pertaining to ethical considerations and issues in global surgery was extracted from the studies.

Collating, Summarising and reporting the results

After data extraction, results were summarised and are reported in section 3. The grounded theory approach reported by Strauss and Corbin10 was used to analyse the ethical content of all included studies. Open coding was used to identify abstract concepts reported in the literature and attempts made to group them first into emerging themes and then into categories and subcategories. As this was a non-linear analysis process, articles were then re-examined to confirm that no codes or themes initially identified were missed and that saturation was achieved. The results of the content analysis have been represented in tables and charts.

Patient and public involvement

As this research represents a review of previously published literature rather than clinical research, patients were not directly involved in the design, conduct, assessment or dissemination of this study.

Results

Descriptive analysis

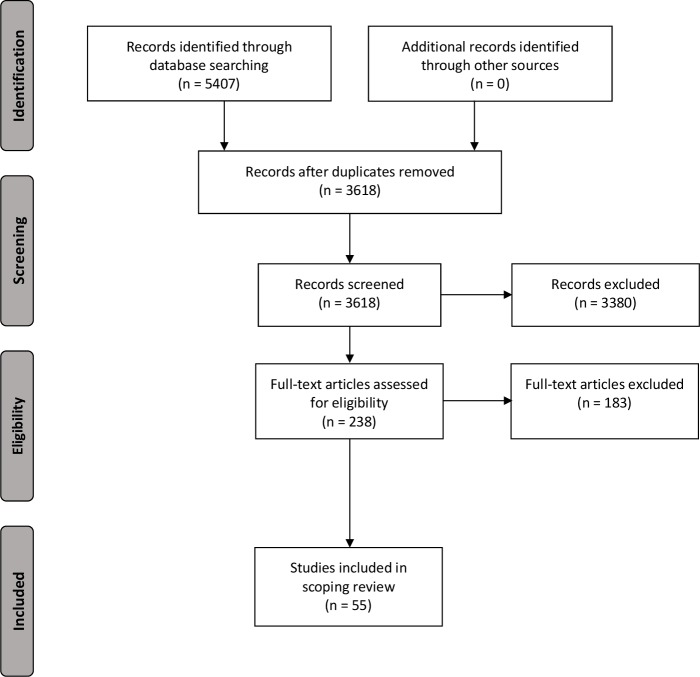

The search yielded 5407 studies. After the removal of duplicates and screening the titles and abstracts for relevance, a total of 238 full-text articles were reviewed for inclusion. Of those, 55 were included in the final analysis. This is summarised in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses chart (figure 1).11 Included articles were published between 2005 and 2019 (table 1).

Figure 1.

: PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.11

Table 1.

Summary of literature included in scoping review and domains identified in each article

| First author, year (reference no) |

Countries | Type of publication | Domains referenced in each article (bullet point(·)indicates a theme identified in that article) |

|||

| Clinical care and delivery | Education, Exchange of Trainees and certification | Research, Monitoring and evaluation | Engagement in collaborations and partnerships | |||

| Ahmed, 201712 | UK | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Aliu, 201444 | USA | Original research | · | · | ||

| Almeida, 201813 | Canada Spain |

Original research | · | · | · | |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG)14 | USA | Committee opinion | · | · | · | |

| ACOG15 | USA | Committee opinion | · | · | · | |

| Berkley, 201958 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Bernstein, 200416 | Canada | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Butler, 201617 | USA | Suggested guidelines with commentary | · | · | · | · |

| Coors, 201518 | USA | Original research | · | · | ||

| Cordes, 201819 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | · |

| Cunningham, 201920 | Nigeria USA |

Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | · |

| Dunin De Skyrzzno, 201821 | Burundi UK |

Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Elobu, 201450 | Uganda | Original research | · | · | · | · |

| Erickson, 201351 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Eyal, 201459 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Fallah, 201845 | Canada USA |

Original research | · | |||

| Fenton, 201952 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Ferrada, 201746 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Gishen, 201560 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Hardcastle, 201861 | South Africa | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Harris, 201922 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Howe, 201453 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Howe, 201323 | Canada Nigeria |

Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Hughes, 201324 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Ibrahim, 201525 | Canada | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Isaacson, 201026 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Jesus, 201027 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Kingham, 200928 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Klar, 201863 | Canada | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Krishnaswami, 20184 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Martin, 201429 | USA | Original Research | · | |||

| Mock, 201830 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Mohan, 201847 | UK | Committee opinion | · | · | ||

| Nguah, 201454 | Ghana | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Nouvet, 201855 | UK | Original research | · | |||

| Ott, 201131 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Pean, 201932 | Haiti USA |

Commentary and suggested guidelines | · | · | · | |

| Precious, 201433 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Ramsey, 200762 | Canada | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Sahuquillo, 201464 | Spain Uruguay |

Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Selim, 201456 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Sheth, 201534 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Small, 201448 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Steyn, 201935 | South Africa | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Swendseid, 201957 | Haiti USA |

Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Thiagarajan, 201436 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Wall, 201437 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Wall, 201365 | USA | Commentary/editorial and case study | · | |||

| Wall, 201138 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | ||

| Wall, 200839 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | · | · | |

| Wall, 200640 | USA | Commentary/editorial | · | |||

| Wall, 200841 | USA | Case study | · | |||

| Wall, 200742 | Ghana USA |

Commentary and suggested guidelines | · | · | ||

| Wall, 200543 | Kenya Nigeria USA |

Suggested guidelines | · | · | ||

| Wright, 201949 | UK | Symposium | · | · | ||

| Total no of articles referencing each domain: | 49 | 32 | 17 | 30 | ||

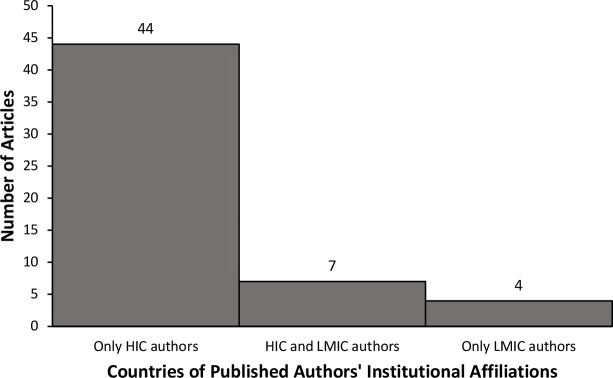

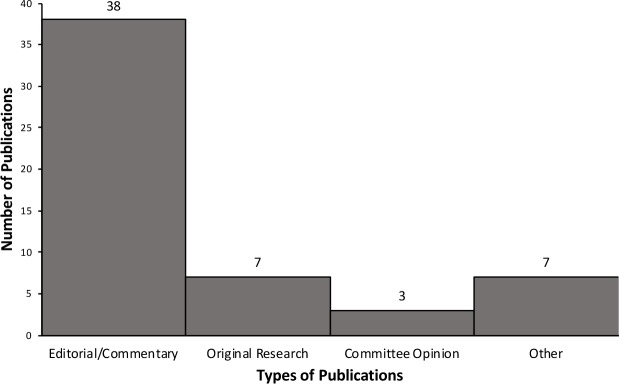

Of the 55 articles included, the vast majority (70.9%) were published by authors affiliated with academic institutions in the USA, followed by Canada (12.7%) and countries of the UK (9.1%). When assessed by country income level as defined by the World Bank, 80% of publications were published exclusively by authors from HICs. There were four studies with exclusively LMIC authorship listed, and seven collaborations between HIC and LMIC authors (figure 2). Most articles were commentaries or editorials (38, or 69.1%) and only seven (12.7%) were original research studies (figure 3). The majority of studies (34, or 61.8%) did not specify which LMIC country the study took place in or which LMIC partners were involved, or they reflected only hypothetical case studies.

Figure 2.

Number of articles per country of published author’s institutional affiliations, organized by income level as classified by the World Bank Atlas Method (HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country).

Figure 3.

Number of each type of publication identified in this scoping review on ethical considerations in global surgery.

Emerging domains

Content analysis identified four major domains in the literature on the ethics of global surgery: (1) the ethics of clinical care and delivery; (2) ethics of education, exchange of trainees and certification; (3) ethics of research, monitoring and evaluation and (4) ethics of engagement and collaboration in partnerships. Most of the literature framed these topics with considerations that related primarily to a visiting surgical team or practitioner (typically from an HIC) and those that related to a hosting surgical team or practitioner (typically from an LMIC). The four domains are described below in greater detail and summarised in box 1.

Box 1. Summary of domains and themes identified in the ethics of global surgery.

Domain 1: Clinical care and delivery

Potential exhaustion of local resources:

Local resources (human and material) may be diverted from more dire basic needs to less urgent, surgical missions.13 17 18 20 22–25 31 45 50–53

Continuity of care and follow-up:

Long-term follow-up plans for patient care should be accounted for in global surgical undertakings.12 14 15 17–20 24 25 27 29 30 32–37 39–43 45 48 51 54–57

Patient, procedure and location selection:

Opportunities for access to surgical missions are not always equitable; patient and procedure selection can be ethically fraught in light of limited resources.13 17–20 23–27 31–33 36 37 40 41 48 52–54 57–59

Variations in standard of care and preparedness of global surgical practitioners:

Global surgical procedures may be performed outside of scope of training and can result in compromised quality of patient care; limited resources available to manage complex surgical diseases can lead to variations in standards of care.12–17 19 20 22 23 26–28 32 33 37 39–49

Cultural awareness, disclosure and informed consent:

Visiting practitioners may be unaccustomed to cultural, social, religious and linguistic differences of the hosting community; challenges with ethical informed consent and disclosure may exist in unfamiliar environments.4 12–43

Domain 2: education, exchange of trainees and certification

Non-transference of knowledge:

Global surgical endeavours may fail to include an educational component for transferring knowledge (clinical, structural or otherwise) or skills to LMIC communities.4 12–14 16 17 19 20 25–27 30 32 33 37 39 41 49 51 56

Relevance of educational activities:

Knowledge or skills taught may be not relevant to host communities or require resources not readily available rendering them futile.19 20 23 25 30 50 59

Level of visiting trainee supervision:

Visiting surgical trainees may be requested to work in settings of limited supervision which may be inappropriate for their skill level.12 15 17 27 28 32 35 47 49 58 60–62

Preparedness of trainees to work in host communities:

Visiting trainees may be unfamiliar with surgical diseases or presentations in hosting communities and their added complexity; visiting trainees may lack insight or preparedness to deal with cultural and linguistic challenges in unfamiliar environments.4 12 17 20 27 35 47 49 60–62

Impact of visiting trainees on local educational programmes:

The presence of visiting global surgical trainees may detract from learning opportunities for local trainees.17 20 30 50 58

Reciprocity of global surgical training programmes:

Overseas training opportunities may be frequently available for HIC surgical trainees, but bidirectional exchanges or similar opportunities for LMIC trainees are not as frequently available.13 20 30 51 58

Human capital flight:

Emigration of trainees away from LMICs may result in ‘brain drain’ and a loss of healthcare providers in those regions.13 17 20 30 35 53 59 63

Domain 3: research, monitoring and evaluation

Involving and crediting researches from LMICs in collaborative research:

Global surgical research activities may neglect to involve researchers from local communities where research occurs or researchers from LMIC may not be adequately credited or involved in publication in global surgical research partnerships.4 17 19 20 22 30 32 35 50

Obligations for institutional ethics review:

Formal research ethics approval from both host and visitor’s institutions should be obtained for global surgical research; if institutional ethics review boards are not available in an LMIC setting, consideration should be given to helping develop research capacity.17 19 22 39 42 64 65

Relevance of research activities:

Research performed in LMICs may be done for the benefit of another external population and may be unlikely to benefit local populations.4 50 64 65

Protection of vulnerable populations in research:

Global surgical research may involve vulnerable populations that are susceptible to exploitation for personal, financial or academic gain; research activities in LMICs present with challenges to informed consent and disclosure as patients may be vulnerable or lack viable alternatives to care.20 39 42 64 65

Monitoring of surgical outcomes:

Global surgical endeavours may fail to monitor and study post-operative complications and surgical outcomes for ongoing quality and process improvement.17 19 20 22 32 34 37–39 43

Domain 4: engagement in collaborations and partnerships

Sustainability in global surgical collaborations:

Global surgical collaborations and partnerships may lack capacity building or fail to plan for sustainability and long-term results.4 12–15 17–20 23 25 27 30–32 37–39 42 44 49 55 63

Involvement of local communities in collaborative partnerships:

Partnerships may fail to adequately involve the hosting institution in planning and coordinating for collaborative efforts.17 20 30 31

Donation of funds and materials:

Donated funds/materials may be inappropriate, unhelpful, expired or not cost-effective. Conflicts of interest or corruption may influence the donation of funds or materials.13 17–20 22–26 31 35 50 51 57

Potential dependence on external donations:

Donations of material or financial aid may undermine local supply chains or result in dependence on external aid sources.12 22 32 37 63

HIC, high-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country.

Clinical care and delivery

One of the most prominently reported domains identified in the literature involved the ethics of delivering clinical care in global surgery (n=49 papers). This term was used to describe ethical considerations relating directly to patient care in global surgery.

The domain of clinical care and delivery predominantly identified the issues of cultural awareness, disclosure and informed consent as ethical concerns.12–43 Authors reported that language barriers, cultural differences or disparate interpretations of patient autonomy could lead to ethical distress over informed consent and ethical disclosure for surgical practitioners in unfamiliar environments. Another frequently identified theme in the included articles was variations in standard of care in different locations and the preparedness of global surgical practitioners to practice in low-resource settings.12–17 19 20 22 23 26–28 32 33 37 39–49 This theme included considerations on whether or not it was ethical to accept a perceived lower standard of care due to resource limitations, the problems caused by visiting teams being unprepared to perform surgery in resource-limited settings, and questions of whether or not to perform procedures outside of a visiting surgical practitioner’s usual scope of practice when considering patients’ limited access to care.

In the literature, global surgical initiatives also created ethical conflicts by exhausting local resources, typically by focusing on or prioritising a single type of operation or specialty at the expense of other types of surgeries happening in that hospital.13 17 18 20 22–25 31 45 50–53 Ethical concerns were also identified in the setting of short-term surgical trips failing to plan for adequate postoperative care and follow-up care for patients.12 14 15 17–20 24 25 27 29 30 32–37 39–43 45 48 51 54–57 Finally, the ethical and equitable distribution of limited resources in regards to selection of patients, procedures or hosting communities was also commonly reported as an area of moral distress in global surgery.13 17–20 23–27 31–33 36 37 40 41 48 52–54 57–59

Education, exchange of trainees and certification

The next domain identified in the literature on the ethics of global surgery was that of education, exchange of trainees and issues relating to certification (n=32). The literature emphasised the value of teaching and transferring knowledge to LMIC communities, with ethical standards not being met when global surgical endeavours failed to prioritise education and knowledge transfer.4 12–14 16 17 19 20 25–27 30 32 33 37 39 41 49 51 56 In some cases, educational initiatives were attempted, but knowledge and skills passed on were not relevant for LMIC settings (eg, if the resources required to perform a procedure were not readily available, then educating on such a procedure was futile).19 20 23 25 30 50 59

Other ethical issues in education focused on the exchange of medical students or surgical trainees. This typically focused on visiting trainees from HICs travelling to LMICs for electives or observerships in global surgery. The adequacy of preparation of these visiting surgical trainees was an important ethical consideration identified, including a lack of familiarity with medical conditions frequently encountered in their host community, as well as the social, cultural and linguistic challenges that trainees encountered in these unfamiliar environments.4 12 17 20 27 35 47 49 60–62 The level of supervision of visiting trainees may have differed relative to their home training environment, resulting in moral distress for the visiting surgical trainee over the safe care of patients.12 15 17 27 28 32 35 47 49 58 60–62 Furthermore, the literature identified that trainees from HICs travelling to LMICs may impact local education programs by taking away surgical experience from local trainees whose education would be more likely to benefit the local community.17 20 30 50 58 There were also concerns of equity in global surgical training exchanges: while overseas training opportunities may be easily available for surgical trainees from HICs, reciprocal opportunities for trainees from LMICs are rarely available.13 20 30 51 58 Finally, the ethics of exchange of trainees is further complicated by the issue of human capital flight or the ‘brain drain’ effect. The emigration of surgical trainees away from LMICs can further deplete resources in already resource-limited settings.13 17 20 30 35 53 59 63

Research, monitoring and evaluation

The third domain identified, the ethics of research, monitoring and evaluation in global surgery, was relatively under-reported domain in the literature (n=17). This domain was used to describe all literature pertaining to surgical research initiatives in or conc

erning LMICs, surgical innovation, monitoring of outcomes and formal evaluation processes for global surgical endeavours. The literature that did discuss this topic placed an emphasis on the necessity for equitable research partnerships between host and visiting communities, including equal opportunities for authorship.4 17 19 20 22 30 32 35 50 The literature also recommended that efforts should be made to obtain formal research ethics approval from all involved partner institutions prior to embarking on surgical research.17 19 22 39 42 64 65 Some suggested that if formal ethics review boards did not exist at the planned site of research, efforts should be made to help create an ethics review board and develop research capacity for that institution; if this could not be accomplished, the research should not be undertaken.17 39 64

Ethical concerns were also identified with the potential for surgical research to exploit vulnerable populations and a failure to obtain adequate informed consent in light of these vulnerabilities.20 39 42 64 65 The available published literature also suggested that ethical global surgical research needed to be relevant and likely to benefit to the host communities to further protect against ethical violations.4 50 64 65

A deficiency in monitoring and evaluation of surgical outcomes was identified by several articles. It was noted, however, that monitoring of surgical outcomes should be made ‘mandatory in order to prevent inadvertent harm (and) the exploitation of patients for goals other than their own welfare’.41 Monitoring was viewed as necessary for the process and quality improvement required to improve global surgical care in resource-limited settings.17 19 20 22 32 34 37–39 43

Engagement in collaboration and partnerships

The engagement of global surgery practitioners and institutions in the creation of long-term sustainable partnerships and collaborations was seen as a priority by several of the articles referenced (n=30). Details on how to best accomplish ethical collaborations, however, were often sparse. The literature reviewed proposed that successful partnerships should be equitable, reciprocal and long term, with the intent of creating sustainability so an eventual transition of care back to the host institution can take place. Yet a lack of capacity building and failure to plan for long-term sustainability was referenced by several articles as an ethical concern with many global surgical initiatives.4 12–15 17–20 23 25 27 30–32 37–39 42 44 49 55 63 Even when partnerships were created with the intent of introducing sustainability, there was often a failure to adequately consult and include LMIC communities and institutions in collaborations.17 20 30 31 The literature was not specific enough to evaluate whether the examples of partnerships discussed reflected singular short-term missions, recurrent occurrences or long-term collaborations.

Ethical considerations also arose regarding the donation of materials, supplies and funding.13 17–20 22–26 31 35 50 51 57 In some cases, concerns were identified with material and financial donations that were expired, inappropriate, unhelpful or not cost-effective for the setting to which they were donated. Other articles discussed conflicts of interest or corruption that influenced how, when, and where donations are made. Finally, concerns were raised that donations to LMIC institutions could contribute to a reliance on external aid sources and undermine local supply chains, acting as a hindrance to capacity-building and sustainability in the long run.12 22 32 37 63

Discussion

The goal of this scoping review was to provide an understanding of the current ethical landscape associated with global surgery. Four discrete domains were identified as important pillars of global surgical activity requiring ethical consideration. These were: clinical care and delivery; education, exchange of trainees and certification; research, monitoring and evaluation; and engagement in partnerships and collaborations. Our review demonstrated that the domain of clinical care and delivery was over-represented relative to the other domains, with the majority of the literature focused on the clinical ethics of individual patient–doctor relationships. There was also a dearth of original research (most of the literature was in the form of commentaries or editorials), and a reporting bias from HICs, specifically the USA. The literature tended to disclose its own issues of bias and recommended increased reporting from the perspective from LMICs.

The focus on direct patient care in global surgery ethics comes as no surprise. The majority of global surgery initiatives still take the form of short-term surgical missions, with the primary goal of delivering surgical service, and most of the literature reflected this. Additionally, physicians and surgeons are well oriented to the supreme importance of the doctor–patient relationship and have a firm grasp of classic biomedical ethics principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice that affect particularly the domain of clinical care and delivery. Unfortunately, in the complex arena of global surgery, focusing on individual patient care at the expense of system level change and limiting ethical discussion to a single ethical framework will likely fall short in producing a sustainable ethical solution.

All four domains identified in the literature need to be addressed when considering global surgical initiatives, with collaboration and partnership forming the foundation. The reporting bias from HICs betrays a lack of collaboration and true partnership with LMIC institutions reflected in many initiatives. This neglect of equitable and sustainable partnerships has echoes of neo-colonialism that must be abandoned if we are to achieve an ethical solution that respects and upholds the unique cultures, beliefs and priorities of LMIC partners. Once an equitable partnership is established, all other domains can be incorporated into a long-term sustainable plan that is consistently informed by ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

It is also likely that additional domains exist that are not recognised in the current literature. Potential domains identified independently by the authors include the ethics of the impact of global surgery on the local economy and on the environment. In the literature reviewed, only Fenton et al52 identified environmental concerns as a potential ethical issue in global surgery. With a more balanced discussion including input from LMIC partners, it is likely that further domains would be uncovered and emphasised. The authors would purport that these domains, though not directly related to patient care, are essential to consider as potential bystander casualties in global surgical initiatives. This speaks to the importance of widening the ethical framework from biomedical ethics alone to the addition of relational, business and environmental ethics.

The use of grounded theory as a method for analysing data is not without controversy. While a comprehensive explication of the method is not possible within the confines of this scoping review, it is important to highlight some of concerns associated with this approach. Theorised as a purely inductive approach at its inception,66 some grounded theorists argue for a truly emergent process of category construction from the data. In this more idealist approach, the standpoint of the researcher is not influenced by preconceived notions of the conceptual structure that will evolve. One can argue that this neutral perspective is not only difficult to achieve; it is also perhaps not even the most desirable because it would seem to require that new knowledge emerges in isolation from the broader conceptual network it is in fact grounded in.67 68 It is important to understand that isolationism is unlikely to be realised and thus, it is critical to address the perspectives that are present and missing in a grounded theory approach.

These considerations are of particular importance to a scoping review such as the one undertaken by these authors; the data and the domains that emerge are derived largely from the perspective of HICs. The interpretation of the data and the thematic analysis was also undertaken by researchers situated within an HIC, some of whom are also engaged in the practice of global surgery. This perspectivism does not necessarily entail that the results are false, but rather that they should be interpreted with both caution and an openness to being interrogated for their veracity. The authors of this study recognise the limitations inherent in this grounded theory approach to the extant literature.

The results of this scoping review highlight these significant gaps in the literature. In an attempt to mitigate these weaknesses and build on the strengths, the results of this scoping review should be used to inform a broader ethical framework of global surgery. The creation of an ethical framework will require a more extensive, iterative process, involving multinational stakeholders, with the specific aim of addressing the perspectives of LMIC partners to assess the internal and external validity of these identified domains. Given the identified gaps, it is anticipated that the identified domains will evolve and that new domains may emerge through this process.

In recognising that international collaborations can bring differing worldviews together, future work will need to be undertaken to inform the ethical foundations of global surgery. Currently, the discourse itself is heavily influenced by HIC ethical principles. This influence may not capture and pay adequate respect to the diversity of values that can inform ethical obligations and the principles that are meant to express them. For example, traditional medical ethics dominated by European and North American discourse typically emphasises autonomy and the individual, and this may not necessarily be sufficient for practice in low-resource settings, where an emphasis on the common good or community-focused public health ethics may predominate.69 Even apparent similarities in how these ethical principles are expressed need to be explored for the meanings that underlie them. Future work needs to consider the importance of building a dialogue that explores and discovers shared values and meanings; work that will seek a common moral grounding for interactions with patients, between teams and within the broader community of stakeholders who are impacted by global surgery.

Conclusion

As the arena of global surgery continues to mature it must also become self-reflective. This literature review demonstrates that the academic surgical community has identified the importance of ethics in global surgery and concedes that the best ethical standards and practices are not always realised. In this setting, ethical practice extends beyond individual patient care to encompass education, partnership and collaboration, and research. A notable gap in the literature was found in the paucity of reporting from LMIC institutions. This perhaps illustrates the crux of the issue with ethics: ethical and equitable solutions cannot be achieved unless and until all stakeholders are present at the table. Given that LMICs are frequently the recipients of global surgical initiatives, the relative absence of their voice in the literature reviewed is a substantive deficiency that requires urgent attention. Any attempt to address the ethical considerations that arise in these collaborations must take into account the perspectives and experiences of the LMIC participants. The lack of original research is a concern, not because ethical principles are empirically derived, but because global surgical ethics should be informed by the experiences of the patients, families and communities that these surgical missions are meant to serve. Similarly, because addressing the disparity in access to the benefits of surgery worldwide requires sustainable, collaborative partnerships to be established, the limited attention in the literature to the ethics of these partnerships in the delivery of surgical care is another gap that requires focused attention. Without meaningful stakeholder input into the current ethical discourse it is likely that domains of concern, and the broader range of perspectives required to inform them, are missing. The authors hope that this literature review will stimulate more primary research in this field of study with more equitable representation from LMIC partners.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the University of Alberta’s Office of Global Surgery, Department of Surgery and the John Dossetor Health Ethics Centre; Kaiyang Fan; and the 2019 Bethune Round Table Conference on Global Surgery for facilitating discussions on the topic of ethics in global surgery. We would like to acknowledge the McMaster Health Sciences library services for input regarding search strategy for this scoping review. Finally, we would like to extend our appreciation to the manuscript reviewers who provided valuable feedback on this project.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @akalhinai

CLG, TR and AAH contributed equally.

Contributors: CLG, TR and AAH contributed equally to this paper as joint first authors. AS, CM and TR conceptualised the study. TR created the search strategy and compiled studies. Title, abstract and full-text screening was completed by AAH, CM and TR. Data extraction was performed by CLG, and analysis was performed by AAH, CM and CLG. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Funding: Funding was provided by the University of Alberta’s Office of Global Surgery.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to this study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Bath M, Bashford T, Fitzgerald JE. What is 'global surgery'? Defining the multidisciplinary interface between surgery, anaesthesia and public health. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001808. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet 2015;386:569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sgrò A, Al-Busaidi IS, Wells CI, et al. Global surgery: a 30-year bibliometric analysis (1987-2017). World J Surg 2019;43:2689–98. 10.1007/s00268-019-05112-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnaswami S, Stephens CQ, Yang GP, et al. An academic career in global surgery: a position paper from the Society of university surgeons Committee on academic global surgery. Surgery 2018;163:954–60. 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stawicki SP, Nwomeh BC, Peck GL, et al. Training and accrediting international surgeons. Br J Surg 2019;106:e27–33. 10.1002/bjs.11041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudson MM, Tarpley MJ, Numann PJ. Global surgery opportunities for U.S. surgical residents: an interim report. J Surg Educ 2015;72:e60–5. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery LM. Short-Term medical missions: enhancing or eroding health? Missiology 1993;21:333–41. 10.1177/009182969302100305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sykes KJ. Short-Term medical service trips: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e38–48. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research : Techniques and procedures for developing Grounded theory. 2nd edition Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc, 1998: 3–217. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed F, Grade M, Malm C, et al. Surgical volunteerism or voluntourism - Are we doing more harm than good? Int J Surg 2017;42:69–71. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almeida JP, Velásquez C, Karekezi C, et al. Global neurosurgery: models for international surgical education and collaboration at one university. Neurosurg Focus 2018;45:e5. 10.3171/2018.7.FOCUS18291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 466: ethical considerations for performing gynecologic surgery in low-resource settings abroad. ACOG Comm Opin 2010;116:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 759: ethical considerations for performing gynecologic surgery in low-resource settings abroad. ACOG Comm Opin 2018;132:E221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein M. Ethical dilemmas encountered while operating and teaching in a developing country. Can J Surg 2004;47:170–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler MW. Developing pediatric surgery in low- and middle-income countries: an evaluation of contemporary education and care delivery models. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:43–50. 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coors ME, Matthew TL, Matthew DB. Ethical precepts for medical volunteerism: including local voices and values to guide RhD surgery in Rwanda. J Med Ethics 2015;41:814–9. 10.1136/medethics-2013-101694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cordes SR, Robbins KT, Woodson G. Otolaryngology in low-resource settings: practical and ethical considerations. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2018;51:543–54. 10.1016/j.otc.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham AJ, Stephens CQ, Ameh EA, et al. Ethics in global pediatric surgery: existing dilemmas and emerging challenges. World J Surg 2019;43:1466–73. 10.1007/s00268-019-04975-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunin De Skrzynno SC, Di Maggio F. Surgical consent in sub-Saharan Africa: a modern challenge for the humanitarian surgeon. Trop Doct 2018;48:217–20. 10.1177/0049475518780531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris MJ, Junkins SR. A philosophical primer for your first global anesthesia experience. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 2019;9:25–30. 10.1007/s40140-019-00304-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howe KL, Malomo AO, Bernstein MA. Ethical challenges in international surgical education, for visitors and hosts. World Neurosurg 2013;80:751–8. 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes SA, Jandial R. Ethical considerations in targeted paediatric neurosurgery missions. J Med Ethics 2013;39:51–4. 10.1136/medethics-2012-100610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibrahim GM, Bernstein M. Models of neurosurgery international aid and their potential ethical pitfalls. Virtual Mentor 2015;17:49–55. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2015.17.01.pfor1-1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isaacson G, Drum ET, Cohen MS. Surgical missions to developing countries: ethical conflicts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;143:476–9. 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jesus JE. Ethical challenges and considerations of short-term international medical initiatives: an excursion to Ghana as a case study. Ann Emerg Med 2010;55:17–22. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kingham TP, Muyco A, Kushner A. Surgical elective in a developing country: ethics and utility. J Surg Educ 2009;66:59–62. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin BM, Love TP, Srinivasan J, et al. Designing an ethics curriculum to support global health experiences in surgery. J Surg Res 2014;187:367–70. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mock C, Debas H, Balch CM, et al. Global surgery: effective involvement of US academic surgery: report of the American surgical association Working group on global surgery. Ann Surg 2018;268:557–63. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ott BB, Olson RM. Ethical issues of medical missions: the clinicians' view. HEC Forum 2011;23:105–13. 10.1007/s10730-011-9154-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pean CA, Premkumar A, Pean M-A, et al. Global orthopaedic surgery: an ethical framework to prioritize surgical capacity building in low and middle-income countries. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019;101:01358. 10.2106/JBJS.18.01358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Precious DS. Important pillars of charity cleft surgery: the avoidance of "safari surgery". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014;117:395–6. 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheth NP, Donegan DJ, Foran JRH, et al. Global health and orthopaedic surgery-A call for international morbidity and mortality conferences. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;6C:63–7. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.11.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steyn E, Edge J. Ethical considerations in global surgery. Br J Surg 2019;106:e17–19. 10.1002/bjs.11028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiagarajan RI, Scheurer MA, Salvin JW. Great need, scarce resources, and choice: reflections on ethical issues following a medical mission. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:311–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall AE. Ethics in global surgery. World J Surg 2014;38:1574–80. 10.1007/s00268-014-2600-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wall LL. Ethical concerns regarding operations by volunteer surgeons on vulnerable patient groups: the case of women with obstetric fistulas. HEC Forum 2011;23:115–27. 10.1007/s10730-011-9153-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Hancock BD. Ethical aspects of urinary diversion for women with irreparable obstetric fistulas in developing countries. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:1027–30. 10.1007/s00192-008-0559-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Lassey AT, et al. Humanitarian ventures or 'fistula tourism?': the ethical perils of pelvic surgery in the developing world. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2006;17:559–62. 10.1007/s00192-005-0056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wall LL, Wilkinson J, Arrowsmith SD, et al. A code of ethics for the fistula surgeon. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;101:84–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wall LL. Ethical issues in vesico-vaginal fistula care and research. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007;99 Suppl 1:S32–9. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wall LL. Hard questions concerning fistula surgery in third World countries. J Womens Health 2005;14:863–6. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aliu O, Corlew SD, Heisler ME, et al. Building surgical capacity in low-resource countries: a qualitative analysis of task shifting from surgeon volunteers' perspectives. Ann Plast Surg 2014;72:108–12. 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31826aefc7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fallah PN, Bernstein M. Barriers to participation in global surgery academic collaborations, and possible solutions: a qualitative study. J Neurosurg 2018:1–9. 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrada P, Sakran JV, Dubose J, et al. Above and beyond: a primer for young surgeons interested in global surgery. Bull Am Coll Surg 2017;102:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohan HM, Fitzgerald E, Gokani V, et al. Engagement and role of surgical trainees in global surgery: consensus statement and recommendations from the association of surgeons in training. Int J Surg 2018;52:366–70. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Small BM, Hurley J, Placidi C. How do we choose? J Clin Ethics 2014;25:308–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright NJ, Ade-Ajayi N, Lakhoo K. Global surgery symposium. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:234–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, et al. Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery 2014;155:585–92. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erickson BA, Gonzalez CM. International surgical missions: how to approach, what to avoid. Urology Times 2013;41:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fenton KN, Cardarelli M, Molloy F, et al. Ethics in humanitarian efforts: when should resources be allocated to paediatric heart surgery? Cardiol Young 2019;29:36–9. 10.1017/S1047951118001713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howe EG. Epilogue: ethical goals for the future. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:323–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguah SB. Ethical aspects of arranging local medical collaboration and care. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:314–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nouvet E, Chan E, Schwartz LJ. Looking good but doing harm? perceptions of short-term medical missions in Nicaragua. Glob Public Health 2018;13:456–72. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1220610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selim NM. Teaching the teacher: an ethical model for international surgical missions. Bull Am Coll Surg 2014;99:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swendseid B, Tassone P, Gilles PJ, et al. Taking free flap surgery abroad: a collaborative approach to a complex surgical problem. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;160:426–8. 10.1177/0194599818818459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berkley H, Zitzman E, Jindal RM. Formal training for ethical dilemmas in global health. Mil Med 2019;184:8–10. 10.1093/milmed/usy246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eyal N. Pediatric heart surgery in Ghana: three ethical questions. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:317–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gishen K, Thaller SR. Surgical mission TRIPS as an educational opportunity for medical students. J Craniofac Surg 2015;26:1095–6. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardcastle TC. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg 2008;32:1562. 10.1007/s00268-007-9449-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramsey KM, Weijer C. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg 2007;31:2067–9. 10.1007/s00268-007-9243-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klar G, Zalan J, Roche AM, et al. Ethical dilemmas in global anesthesia and surgery. Can J Anaesth 2018;65:861–7. 10.1007/s12630-018-1151-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sahuquillo J, Biestro A. Is intracranial pressure monitoring still required in the management of severe traumatic brain injury? ethical and methodological considerations on conducting clinical research in poor and low-income countries. Surg Neurol Int 2014;5:133993. 10.4103/2152-7806.133993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wall AE, Kodner IJ, Keune JD. Surgical research abroad. Surgery 2013;153:723–6. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of Grounded theory. New York, NY: AldineTransaction Publishers, 1967: 237–9. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldkuhl G, Cronholm S. Adding theoretical grounding to grounded theory: toward multi-grounded theory. Int J Qual Methods 2010;9:187–205. 10.1177/160940691000900205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thornberg R. Informed Grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 2012;56:243–59. 10.1080/00313831.2011.581686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwartz L, Hunt M, Sinding C, et al. Models for humanitarian health care ethics. Public Health Ethics 2012;5:81–90. 10.1093/phe/phs005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2020-002319supp001.pdf (13.6KB, pdf)