Abstract

Objective:

The most common form of measurement of breath alcohol content (BrAC) is through the use of a diode catheter. This study aims to test the accuracy of breath alcohol analysis through different manipulations.

Methods:

BrAC was measured after individuals consumed each standardized beer until they reached a 0.1 BrAC. Then, the individuals were breath analyzed while not providing full effort, using the side of their mouths, immediately after hyperventilating, 5 and 10 min after hyperventilation, immediately after a sip of water, and 5 min after that water.

Results:

There were 54 individuals. Two baselines were used as the controls. The first baseline was a mean BrAC of. 104 with standard deviation of +0.008 for poor effort, side of mouth, and hyperventilating. The second baseline used for drinking water manipulations was a BrAC of 0.099 + 0.11. Poor effort (mean + standard deviation: 0.099 ± 0.10, P < 0.0001), immediately after hyperventilating (0.086 ± 0.011, P < 0.0001), 5 min after hyperventilating (0.099 ± 0.009, P < 0.0001), and 10 min after hyperventilating (0.099 ± 0.011, P < 0.0001) were all found to be statistically significant in their ability to lower BrAC. Both immediately after water (0.084 ± 0.011, P < 0001) and 5 min after drinking water (0.096 ± 0.13, P < 0.0001) were found to have significantly altered the BrAC.

Conclusion:

Our research shows that manipulations can alter BrAC readings significantly. Breath analyzer operators should be cognizant of these methods that may lead to falsely lower BrAC readings.

Keywords: Alcohol intoxication, breath alcohol content, breathalyzer

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use in the United States is pervasive among the general population. Its use has far-ranging impacts on society from influencing productivity at work to litigious issues to a major factor in much of the trauma seen in emergency departments. Specifically, in the emergency department, its use not only impacts the general health of a patient but also in the acute setting can determine disposition, treatment, and legal competency. It is, therefore, necessary to use objective measurements to determine a patient's serum blood alcohol content (BAC). Breath alcohol content (BrAC) is a commonly measured value to estimate serum alcohol levels. BrAC can be obtained by infrared spectrophotometry or through the use of electrochemical fuel cell technology. The most common form of measurement by police and medical personnel is through the use of a diode catheter that measures the amount of ethanol detected in the breath. One of the most common breathalyzers used is the Alco-Sensor IV which uses fuel cell technology to convert alcohol detected with deep lung breaths and convert it to acetic acid and use the electrons released to detect an electrical current and convert it into a BrAC which uses fuel cell. There have been very few studies done using breathalyzers and specifically, no studies looking at manipulations that may affect the BrAC readings. Previous studies have sought to determine the accuracy of BrAC compared to serum (blood alcohol concentration). Using an Alco-Sensor III, researchers found a strong correlation between BrAC and BAC in cooperative patients.[1] Others have found that breathalyzers often underestimate by >0.01 approximately 61% of the time.[2] The area where point of care breath alcohol analyzers are employed the most is likely those used by police officers to detect roadside sobriety. The well-known and devastating side effects of driving while under the influence of alcohol make it imperative to use accurate and rapid tests to determine sobriety, for safety and legal reasons. The reliability of commercial breath alcohol tests in cooperative patients is well established; however, there have not been studies that have investigated the accuracy of these tests while being manipulated by the individual being tested.

The present study aims to test the accuracy of breath analysis through a range of manipulations that may be employed, consciously or surreptitiously, to alter BrAC readings. This is a topic of great interest to many people since the breathalyzer is used often, and breathalyzer readings are often relayed to hospital staff from prehospital providers. The accuracy of these readings may affect the treatment of individuals in the emergency department and trauma bay since elevated readings may explain altered mental status. In addition, BrAC levels may affect the disposition of patients as well as the reliability of their decisions regarding medical care.

METHODS

This was an observational study involving healthy nonalcoholic (self-reported) volunteers over the age of 21 years. It was approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board Committee, and it was also registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ID NCT02580318). The study was conducted on the grounds of a Level 1 trauma center and under the direct supervision of the sober investigators. The participants were thoroughly screened prior to participation to ensure their safety. Participants were not allowed to participate if they suffered from the following diseases: alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, kidney/bladder stones, kidney disease, liver disease, or stomach ulcers. Participants were screened for alcoholism, a condition that may have affected results due to known alcohol metabolism differences in chronic users, using the validated CAGE questionnaire (Have you ever felt you needed to Cut down on your drinking? Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? Have you ever felt Guilty about drinking? Have you ever felt you needed a drink first thing in the morning, an “Eye opener”, to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?). Organ transplant patients, dialysis patients, and patients with alcohol or wheat allergies were also not allowed to participate. Female patients had a urine pregnancy test done to ensure they were not pregnant before consuming alcohol. The participant was also advised that their voluntary participation may lead to a hangover including mild nonlife-threatening symptoms such as feeling thirsty or dehydrated, fatigue, headache, nausea, vomiting, feeling weak, difficulty concentrating, photophobia, phonophobia, increased sweating, insomnia, anxiety, feeling depressed, and trembling or shaking.

The study was conducted during multiple sessions involving approximately 3–6 participants in each session. The volunteers gathered at the study location with the investigators and signed informed consent. Then, each participant was provided the same type of beer (12 ounces of 5.2% alcohol by volume Belgium style wheat ale). Participants consumed beer until they reached a BrAC of 0.1 measured with a hospital breathalyzer (Alco-Sensor IV) that had been recently calibrated. The Alco-Sensor IV is an evidential grade handheld breath alcohol tester. It is considered to be the most widely used and popular handheld breath alcohol tester available. To properly assess the number of beers required to attain a BrAC of 0.1, the participants were breath analyzed 15 min after they finished each beer, until they reached the goal of 0.1 ± 0.005. The number of beers consumed and the associated BrAC after each beer was recorded for each participant. No participant was ever forced to drink more alcohol than they felt comfortable consuming and they were able to withdraw from the study at any time.

Once the participants reached a 0.1 BrAC, they were taken to a separate area away from the other participants and again breath analyzed after various time intervals and maneuvers. First, the individuals were breath analyzed while not providing full effort (but enough to achieve a reading). Next, they blew into the breathalyzer out of the side of their mouths. Then, they were breath analyzed immediately after hyperventilating (10 breaths in 10 s) and at 5 and 10 min after hyperventilation. Finally, they used the breathalyzer immediately after a sip of water and 5 min after that water. All of the data were recorded by one of the study investigators, and the participants were blinded to their results.

On completion of the manipulations, all participants remained at the study site, under the direct supervision of the investigators, until their BrAC fell below 0.08. Sober nonparticipants drove all study participants' home. To ensure additional safety of the participants, the investigators were not drinking, so there were sober health-care providers on site, and hospital security was available, if needed.

Descriptive statistical analyses as well as Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient were employed to determine if any statistically significant correlation existed for any of the manipulations.

RESULTS

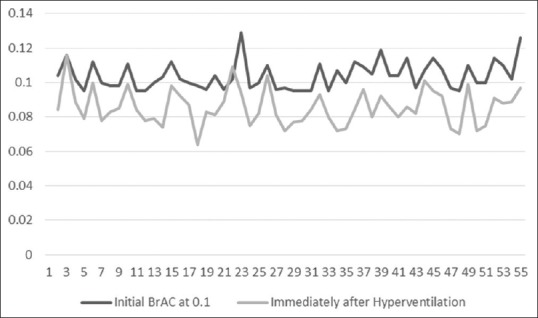

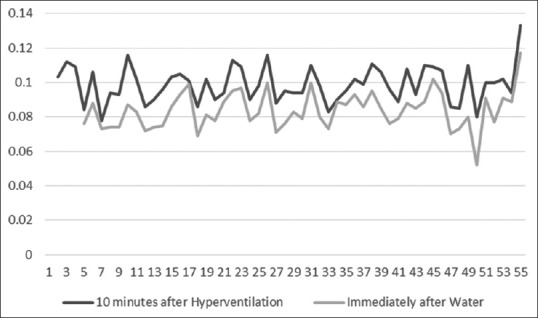

A total of 54 participants were enrolled, 33 males and 21 females, mostly Caucasian, with a mean age of 28.7. Separate paired sample t-tests were conducted for the normally distributed values. There were two baselines used as the controls to evaluate for statistically significant deviation after employing each manipulation. The first baseline, as recorded after the patient reached a BrAC of 0.01, was a mean BrAC of 0.104 with standard deviation of +0.008 for poor effort, side of mouth, and hyperventilating. The second baseline used for drinking water manipulations was a BrAC of 0.099 + 0.11 (the average BrAC 10 min after individuals were asked to hyperventilate). Poor effort, immediately after hyperventilating [Figure 1], 5 min after hyperventilating, and 10 min after hyperventilating were all found to be statistically significant in their ability to lower BrAC. Both immediately after water [Figure 2] and 5 min after drinking water were found to have significantly altered the BrAC. Having individuals use the breathalyzer from the side of their mouth, as opposed to the center, as the instructions suggest, did not cause any statistically significant difference [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Baseline breath alcohol content versus breath alcohol content immediately after hyperventilation

Figure 2.

Breath alcohol content 10 min after hyperventilation versus breath alcohol content immediately after water

Table 1.

Statistical analysis

| Manipulation | Mean BrAC±SD | P |

|---|---|---|

| Poor effort | 0.099±0.010 | <0.0001 |

| Side of the mouth | 0.102±0.009 | <0.17 |

| Hyperventilation (immediate) | 0.086±0.011 | <0.0001 |

| Hyperventilation (5 min) | 0.099±0.009 | <0.0001 |

| Hyperventilation (10 min) | 0.099±0.011 | <0.0001 |

| Drinking water (immediate) | 0.084±0.011 | <0.0001 |

| Drinking water (5 min) | 0.096±0.013 | <0.0001 |

BrAC: Breath alcohol content, SD: Standard deviation

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Our sample size (n = 54) is fairly small. We used only one type of commercially available analyzer (Alco-Sensor IV). Other technologies and methods of analyzing breath alcohol (as in other than using diode catheter) may or may not be able to be manipulated through the techniques employed in this study. Furthermore, there may be other techniques that were not used that could more significantly alter BrAC readings. We did not investigate methods or materials that may also falsely elevate a person's BrAC which could have dramatic legal consequences as well.

There were also five data points that were not recorded while the individuals were undergoing manipulations: one BrAC value in the side of the mouth phase, one in the poor effort phase, and three within the drinking water manipulation. In these instances, the recorded value was left blank on our data collection by one of the recorders. However, this overall likely had no effect on our data analysis.

DISCUSSION

This small study of 54 participants showed that a range of manipulations can alter a breath analyzer by a statistically significant amount. However, as in all studies, statistical and clinical significance may not always be the same. Specifically, drinking water and hyperventilating both significantly altered the BrAC readings insofar as there may a noticeable and clinically significant difference. Given that we know BrAC is a point of care test, operators should be aware of these limitations in accuracy and potential for erroneous readings.

Our choice of manipulations stemmed from a priori hypotheses as to which maneuvers may affect BrAC. Additionally, maneuvers were selected that can be employed without any significant effort or that can be easily concealed or performed covertly. It is likely that there are many more manipulations that would result in alteration of BrAC which may be studied in the future. Different foods or liquids other than water may alter BrAC as well; however, these may be more easily identified. Hyperventilation and water likely are able to artificially decrease measured BrAC due to interfering with the alcohol content in exhaled breaths. Hyperventilation specifically might alter the measured BrAC due to increasing the amount of air measured from dead space that does not participate in gas exchange. The air measured after hyperventilation, therefore, has less dissolved alcohol.

In the emergency department as well as in a litigious or law enforcement environment, breath analyzer operators should be cognizant of these various methods that may lead to falsely lower (or higher) BrAC readings. The level at which now all states have set the legal BAC limits to 0.08 (and in most states 0.04 for commercial drivers). A situation in which the user used a manipulation like hyperventilation to falsely lower their actual BrAC by 0.02 or more is entirely plausible given the results of our study. It may be prudent to employ other methods (as in direct blood draw alcohol levels) if there is a high index of suspicion of inaccurate readings.

CONCLUSION

Our research shows that manipulations can alter BrAC readings. Specifically, hyperventilation and drinking water before using the breathalyzer were shown to significantly lower the BrAC readings. Breath analyzer operators should be cognizant of these methods that may lead to falsely lower BrAC readings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gibb KA, Yee AS, Johnston CC, Martin SD, Nowak RM. Accuracy and usefulness of a breath alcohol analyzer. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:516–20. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80517-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding P, Field PH. Breathalyzer accuracy in actual law enforcement practice:A comparison of of blood-and breath-alcohol results in Wisconsin drivers. J Forensic Sci. 1987;32:1235–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]