Abstract

Purpose

One aspect of the hidden curriculum of medicine is specialty disrespect (SD)—an expressed lack of respect among medical specialties that occurs at all levels of training and across geographic, demographic, and professional boundaries, with quantifiable impacts on student well-being and career decision making. This study sought to identify medical students’ perceptions of and responses to SD in the learning environment.

Methods

We conducted quantitative and content analysis of an annual survey collected between 2008 and 2012 from 702 third- and fourth-year students at the University of Washington School of Medicine. We describe the frequency of reported SD, its self-rated impact on student specialty choice, and major descriptive categories.

Results

Nearly 80% of respondents reported experiencing SD in the previous year. A moderate or strong impact on specialty choice was reported by 25.9% of respondents. In our sample, students matching into family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, and emergency medicine were most likely to report exposure. Content analysis identified two new concepts not previously reported. Internecine strife describes students distancing themselves from both disrespecting and disrespected specialties, while legitimacy questions the validity of the targeted specialty.

Conclusions

SD is a consistent and ubiquitous part of clinical training that pushes students away from both disrespecting and disrespected specialties. These results emphasize the need for solutions aimed at minimizing disrespect and mitigating its effects upon students.

Introduction

The hidden curriculum reflects a professional culture within medicine that is “implicitly taught by example.”1–4 The hidden curriculum has unintended consequences on student career choice and emotional well-being.5–15

Specialty disrespect (SD) is one element of the hidden curriculum, encompassing unwarranted, negative, and denigrating comments made by trainees and physicians about different specialties.8 SD affects all specialties, starting early and touching most medical students by graduation, especially those interested in family medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, and general surgery.6,8–10,16–18 Students witnessing disrespectful communication and behaviors are more likely to face stress, depression, and substance misuse.19,20

We analyzed survey data from students regarding SD. We seek to determine if the prevalence remains high and to assess how students, regardless of their specialty of choice, contextualize and respond to disrespect in the learning environment.

Methods

Data Source

Between 2008 and 2011, medical students at the University of Washington were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding the learning environment at the end of the third and fourth years (approximately 400 students per year). We analyzed transcribed, deidentified data from the three SD questions of the yearly learning environment survey between 2008 and 2011. Questions included:

“Were you exposed to disrespectful comments about specialties during your previous clerkship year?” (Yes/No)

“Did disrespectful comments about specialties have any impact on career choice?” Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale defining 1 as “not at all” and 5 as “strong impact,” with no definition offered for 2, 3, or 4.

A free-response space for comments.

The University of Washington School of Medicine Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

Respondents

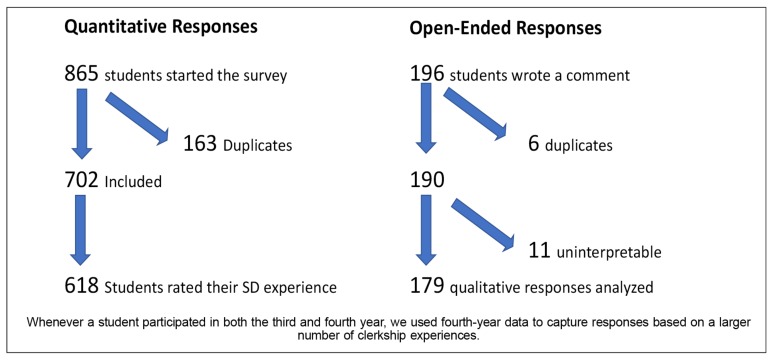

Our final quantitative analysis included 702 unique survey responses from either third- or fourth-year students. The response rate, 39.3%–40.5%, is inexact due to students extending their education, changing the denominator between entering and graduating classes. There were 190 unique student responses for the content analysis. Eleven additional free-response excerpts were excluded due to inapplicable or uninterpretable content (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of Study Participants

Data Analysis

We used χ2 testing with Predictive Analytics Software (PASW) 18.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). We used Dedoose for content analysis (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). Two family medicine faculty, two family medicine residents, and a second-year medical student developed a coding framework emergent from the data to describe themes, which were discussed as a group and further refined for coding.21 After finalizing the framework, the student and two faculty members (Fleiss’ κ statistic=0.87) independently coded all excerpts. Multiple codes could be applied to individual excerpts. After independently coding, the team of three convened to compare coding, resolving disparities via consensus.22,23

We considered students’ use of “primary care” or “generalist” as references to general pediatrics, general internal medicine, or family medicine.24 We considered “surgery” as a reference to general surgery but “surgeons” as a reference to general surgery, surgical subspecialties, or obstetrics/gynecology.

Results

A χ2 test of goodness-of-fit between the study cohort with the overall medical school classes entering between 2005–2008 demonstrated that gender and specialty choice were not significantly different between the study cohort and corresponding medical school classes (Tables 1 and 2). Third-year students comprised 70.5% of the population. Over three quarters (79.7%, n=505) reported exposure to SD in the previous year; the rate varied by specialty choice and was highest among students who matched in family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and emergency medicine (Table 2). While the average impact on specialty choice was 1.90 out of 5, a quarter of students (25.5%) indicated that SD had moderate to strong impact on their specialty choice by marking 3–5 on the Likert scale.

Table 1.

Demographics of Survey Respondents

| Demographic Characteristic | Sample Percent N (%) n = 702 |

Reference Percent*** N (%) N=990 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Gender* | ||

| Female | 50.9 | 51.8 |

| Male | 44.6 | 44.2 |

|

| ||

| Residency Match** | ||

| Family medicine | 15.1 | 16.0 |

| Internal medicine | 14.8 | 14.7 |

| Pediatrics | 8.4 | 7.9 |

| General surgery | 5.7 | 7.5 |

| Emergency medicine | 7.7 | 6.8 |

| Primary care internal medicine | 6.3 | 6.1 |

| Other | 42.0 | 41.0 |

χ2:0.069, df=1, P=0.79

χ2: 2.881, df=6, P=0.823

Reference group is the entire entering class for the corresponding years 2005–2009.

Table 2.

Percentage of Students Experiencing Specialty Disrespect by Residency Match (n=618)***

| Specialty | Number Experiencing Specialty Disrespect | Number Entering Residency | Percent Experiencing Specialty Disrespect |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Family medicine | 93 | 106 | 87.7 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 34 | 39 | 87.2 |

| Emergency medicine | 47 | 54 | 87.0 |

| Pediatrics | 50 | 59 | 84.7 |

| Psychiatry | 21 | 25 | 84.0 |

| Internal medicine | 83 | 104 | 80.0 |

| General surgery | 32 | 40 | 80.0 |

| Primary care internal medicine | 35 | 44 | 79.5 |

| All others | 110 | 147 | 74.8 |

| Total | 505 | 618 | 79.7 |

Residency match data for 2013 was not available at the time of writing.

Content analysis identified four major domains of SD: (1) occurrence, (2) content, (3) impact on student, and (4) student responses (Table 3). “Occurrence” described the sources and targets of SD, including specialty and role. “Content” described the nature of SD. “Impact” could reflect the emotional impact on the student, or the student’s subsequent interest in the target or source specialty. Student responses ranged from humor, to accommodation, to true concerns. The analysis also revealed two concepts not previously described: legitimacy and internecine strife. Comments regarding legitimacy went further than just diminishing the worth or reputation of the specialty, instead indicating to students that the speaker felt that the specialty’s existence was unnecessary. Disrespectful comments had the potential to decrease students’ interest in both source and target specialties, a mutually destructive pattern we termed “internecine strife.”

Table 3.

Code Applications by Content Area, Number and Percent of Available Excerpts (n =179)

| Theme | Subtheme | Number of Excerpts | Percent of All Excerpts | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Occurrence | 146 | 81.6 | ||

| 1a. Source of specialty disrespect | 84 | 46.9 | ||

| Everyone | 21 | 11.7 | “every specialty has another specialty they bad mouth” | |

| Specialists | 19 | 10.6 | “specialists are disrespectful” | |

| Surgical specialties | 19 | 10.6 | “surgeons constantly criticize” | |

| General surgeons | 16 | 8.9 | ||

| Internal medicine | 10 | 5.1 | ||

| Primary care | 6 | 3.4 | ||

| Family medicine | 3 | 1.7 | ||

| 1b. Role of source of specialty disrespect | 53 | 29.6 | ||

| Faculty/attending | 35 | 19.6 | ||

| Residents | 12 | 6.7 | ||

| Students | 4 | 2.2 | ||

| Other | 2 | 1.1 | ||

| 1c. Target of Specialty Disrespect | 118 | 65.9 | ||

| Family medicine | 57 | 31.8 | ||

| Primary care | 23 | 12.8 | ||

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 12 | 6.7 | ||

| Specialists | 8 | 4.5 | ||

| General surgery | 8 | 4.5 | ||

| 2. Content or nature of specialty disrespect | 50 | 27.9 | ||

| Legitimacy | 24 | 13.4 | “Don’t you want to be a real doctor?” (in regard to choosing family med as a career)” “you could teach a monkey to do that” |

|

| Intelligence | 13 | 7.3 | “you’re too smart” | |

| Finances | 8 | 4.5 | “get ready for food stamps,” “radiologists…only care about money;” | |

| Quality of life | 8 | 4.5 | ||

| Undesirable environment | 7 | 3.9 | “Ob/Gyn is filled with people who are tough to get along with.” | |

| 3. Impact of Specialty Disrespect | 73 | 40.8 | ||

| Emotion | 35 | 19.6 | “the disrespectful comments about my career path were very disheartening.” “disrespectful comments… made me resentful.” “self conscious” “ashamed.” |

|

| Interest in target specialty | 27 | 15.1 | “I was thinking of going into Family Med but was discouraged by all the terrible comments” “I am still going to pick Fam Med, but it made me not want to” “Everyone knocks Ob/Gyn. But I still love it.” |

|

| Interest in Source Specialty | 11 | 6.1 | “Surgeons being rude toward other specialties…made me not want to be a surgeon” “Family med hates on everyone else which made me actually dislike family medicine.” |

|

| 4. Student response | 47 | 27.4 | ||

| 4a. Accommodation | 27 | 15.1 | ||

| Humor | 11 | 6.1 | “everybody jokes” “usually in good fun” |

|

| Harmless | 8 | 4.5 | “harmless banter” | |

| Grain of salt | 4 | 2.1 | “grain of salt” | |

| True concern | 2 | 1.1 | “most I would not qualify as disrespectful just a real concern for [patient] safety/care” “self-flagellation by primary care MDs…not without some truth” |

|

| Tradition | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| Human nature | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| 4b. Criticism | 22 | 12.3 | “I thought we were all adults” | |

| Systemic issue | 12 | 6.7 | “this needs to be addressed at every level” “This is disappointing…[and] sad given this is a ‘primary care’ school” “despite [the school]’s reputation as being a very strong school for primary care … the primary care specialties were still disrespected by many other specialties.” “we certainly need to work on improving respect … between dif [sic] specialties.” |

|

| Individual issue | 10 | 5.6 | “very disappointing and reflects poorly on [the speaker]” |

Conclusions

At our institution, nearly four out of five students reported experiencing SD, which reinforces the high rate of specialty disrespect as well as the specialties named as sources and targets reported in studies across nearly two decades and several continents.8–10,17,18

This study revealed two novel concepts: legitimacy and a pattern that we termed internecine strife. “Legitimacy” was applied to comments directed at scope of practice, credentials, or survival of the target specialty. While others have described similar ideas, SD comments undermining specialty legitimacy tell the listener that, beyond having a different scope of practice or lesser earning potential, the specialty is neither real nor worthwhile.10 While comments regarding the legitimacy of the subject specialty often passed from more to less specialized providers, it also went the other way.

The pattern we call “internecine strife” describes the power of SD to push students away from both source and target specialties. Internecine strife may explain the findings of Hunt, et al, that SD dissuaded students interested in surgery and family medicine at nearly equal levels, countering their hypothesis that family medicine would be singularly impacted by SD.9

Notably, the most common source of SD in our sample was “everyone.” The range of implicated specialties reinforces that no specialty is immune to disrespectful conduct, including family medicine.9,10,17 While students at our institution identified family medicine as the most disrespected specialty and students matching into family medicine were most likely to report exposure to disrespect, several comments clearly identify family medicine providers engaged in disrespect. We must see ourselves not just as targets, but also as agents whose behavior can and must change.

Our findings are subject to limitations, including being a single institution survey with limited participation from fourth-year students, selection and recall bias, and a team largely comprised of family physicians.17 Finally, our coding framework was emergent from the data rather than a priori designed.

In a time of provider shortage, efforts to increase the supply of primary care physicians can no longer fail to directly confront the hidden curriculum. Teamwork is paramount to the delivery of safe and effective health care, and respect among medical professionals must be the cornerstone of the relationships between team members within our training institutions.25

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Doug Shaad, PhD, and Laura-Mae Baldwin, MD.

Funding/Support

The University of Washington School of Medicine Medical Student Research Training Program supported this work. The funding institution had no role in the study design, in collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authorship team and not an official position of the institution or funder.

Presentations

Alston MT. Specialty Disrespect at a Primary Care School: Student Perspectives. Presentation at the Western Student Medical Research Forum, Carmel, CA, January, 2013. Kost A, Cawse-Lucas J. The Impact of Specialty Disrespect on Primary Care Residency Choice. Presented as a Work-in-Progress at the 47th Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, San Antonio, TX, May 6, 2014.

References

- 1.Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in physicians’ professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 2003 78(12):1203–1210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 1998 73(4):403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians. The hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1S1):S16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahood SC. Medical education: beware the hidden curriculum. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Can Fam Physician. 2011 57(9):983–985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ellsbury KE, Stritter FT. A study of medical students’ specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 1997 72(6):534–541. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J, Kutob R. Comments heard by US medical students about family practice. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Fam Med. 2003 35(8):573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolhurst H, Stewart M. Becoming a GP—a qualitative study of the career interests of medical students. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Aust Fam Physician. 2005 34(3):204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamien BA, Bassiri M, Kamien M. Doctors badmouthing each other. Does it affect medical students’ career choices? [Accessed December 10, 2018];Aust Fam Physician. 1999 28(6):576–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt DD, Scott C, Zhong S, Goldstein E. Frequency and effect of negative comments (“badmouthing”) on medical students’ career choices. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 1996 71(6):665–669. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199606000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes D, Tumiel-Berhalter LM, Zayas LE, Watkins R. “Bashing” of medical specialties: students’ experiences and recommendations. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Fam Med. 2008 40(6):400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markert RJ. Why medical students change to and from primary care as career choice. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Fam Med. 1991 23(5):347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third- and fourth-year students’ focus-group discussions. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 1997 72(7):635–640. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199707000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natanzon I, Ose D, Szecsenyi J, Campbell S, Roos M, Joos S. Does GPs’ self-perception of their professional role correspond to their social self-image?—a qualitative study from Germany. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selva Olid A, Zurro AM, Villa JJ, et al. Universidad y Medicina de Familia Research Group (UNIMEDFAM) Medical students’ perceptions and attitudes about family practice: a qualitative research synthesis. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stagg P, Prideaux D, Greenhill J, Sweet L. Are medical students influenced by preceptors in making career choices, and if so how? A systematic review. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Rural Remote Health. 2012 12:1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips SP, Clarke M. More than an education: the hidden curriculum, professional attitudes and career choice. Med Educ. 2012;46(9):887–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hearst N, Shore WB, Hudes ES, French L. Family practice bashing as perceived by students at a university medical center. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Fam Med. 1995 27(6):366–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens MB, Lennon C, Durning SJ, Maurer D, DeZee K. Professional badmouthing: who does it and how common is it? [Accessed December 10, 2018];Fam Med. 2010 42(6):388–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson TJ, Gill DJ, Fitzjohn J, Palmer CL, Mulder RT. The impact on students of adverse experiences during medical school. Med Teach. 2006;28(2):129–135. doi: 10.1080/01421590600607195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber R. Basic Content Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuendorf KA. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.King JE. Software solutions for obtaining a kappa-type statistic for use with multiple raters. Presentation at Southwest Educational Research Association Annual Meeting; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersdorf RG. The doctor is in. [Accessed December 10, 2018];Acad Med. 1993 68(2):113–117. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 1: the nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):845–852. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318258338d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]