Abstract

Background

Sex may be an important modifier of brain health in response to risk factors. We compared brain structure and function of older overweight and obese women and men with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Cross-sectional cognitive assessments and magnetic resonance images were obtained in 224 women and 95 men (mean age 69 years) with histories of type 2 diabetes mellitus and overweight or obesity. Prior to magnetic resonance images, participants had completed an average of 10 years of random assignment to either multidomain intervention targeting weight loss or a control condition of diabetes support and education. Total (summed gray and white) matter volumes, white matter hyperintensity volumes, and cerebral blood flow across five brain regions of interest were analyzed using mixed-effects models.

Results

After covariate adjustment, women, compared with men, averaged 10.9 [95% confidence interval 3.3, 18.5; ≈1%] cc greater summed region of interest volumes and 1.39 [0.00002, 2.78; ≈54%] cc greater summed white matter hyperintensity volumes. Sex differences could not be attributed to risk factor profiles or intervention response. Their magnitude did not vary significantly with respect to age, body mass index, intervention assignment, or APOE-ε4 genotype. Sex differences in brain magnetic resonance images outcomes did not account for the better levels of cognitive functioning in women than men.

Conclusions

In a large cohort of older overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus, differences in brain volumes and white matter disease were apparent between women and men, but these did not account for a lower prevalence of cognitive impairment in women compared with men in this cohort.

Trial registration

Keywords: Sex, Brain imaging, Diabetes, Obesity

The prevalence of cognitive impairment may differ between women and men depending on age and other risk factors (1,2). Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and midlife obesity may account for some of this. These conditions independently increase risks for cognitive impairment (3,4) and they disproportionately affect women more than men (5,6). Despite this, in the large Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) cohort of overweight or obese adults with T2DM, ages 55–87 years, the prevalence of cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment or dementia) has been reported to be markedly lower among women than men: adjusted odds ratio of 0.55 [95% confidence interval 0.43, 0.71] (7).

A subset of this cohort underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess brain structure and cerebral blood flow (CBF). We examined whether women and men differed in brain volumes, white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volumes, and CBF and, if so, whether these aligned with differences seen for cognitive impairment. T2DM is associated with impaired brain structure and function (8,9) and obesity is associated with reduced CBF and microvasculature damage (10,11), however it is not known whether sex differences in brain structure and function are evident among older adults with both conditions. Across other cohorts, differences between sexes in rates of brain atrophy and the presence of white matter disease are inconsistent (1,12,13). Studies are more consistent in finding that CBF tends to be greater among women than men (13–15).

We also examined whether sex differences in brain structure and function were associated with relative imbalances in risk factors. Some risk factors may be more potent in one sex than the other (eg, APOE-ε4 in women), some may be more common in one sex than the other (eg, smoking in men), and some risk factors may be particular to one sex (eg, menopause) (1,16,17).

Methods

The Look AHEAD trial design and methods have been published (18,19). It was a multicenter, single-blinded randomized controlled trial that recruited 5,145 volunteers during 2001–2004 with T2DM, ages 45–76 years, and with body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 kg/m2 (>27 kg/m2 if on insulin). Study protocols and consent forms were approved by Institutional Review Boards.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to a multidomain Intensive Lifestyle Intervention or a Diabetes Support and Education comparator, which continued until 2012 (19). Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group and individual sessions focused on diet modification and increased physical activity to induce and maintain at least 7% average weight losses (20). Diabetes Support and Education group sessions focused on improving diet, physical activity, and social support (21).

Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Participants from three Look AHEAD clinics who had no contraindications and who provided separate informed consent underwent brain MRI. Images were acquired 10–12 years from Look AHEAD enrollment. These clinics had originally enrolled 999 participants. By the start of the MRI study, 77 had died (9.8% of males and 6.3% of females, p = .04). Of the 922 survivors, 319 (26% of males and 40% of females: p < .001) ultimately provided study MRIs for volumes; 310 (97%) MRIs met quality control standards for CBF assessment (22).

Standard protocols were used for brain tissue segmentation and region of interest (ROI) labeling for volumes and ROI-specific WMH volumes (23–25). CBF was assessed with multiphase pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling with background suppression for labeling the endogenous blood water (26), and expressed in units of mL/100 g/min, which includes an adjustment for local gray matter voxel occupancy. Measures from five nonoverlapping ROIs were analyzed: frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes and the limbic region (ie, the frontal cingulate, parietal cingulate, insula, and perirhinal cortex) (22).

Cognitive Function

Cognitive assessments were performed by centrally trained and certified staff (27). Verbal learning and memory were assessed with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, speed of processing and working memory were assessed with the Digit Symbol Coding test, executive functions were assessed with the Modified Stroop Color and Word Test and the Trail Making Test-Part B, attention was assessed with the Trail Making Test-Part A, and global cognitive functioning was assessed with the Modified Mini-Mental Status exam. Administrations occurred within an average of 19 days of MRI. Scores were z-transformed and ordered so higher scores reflected better performance. A composite measure was the average z-score across tests (27).

Other Measures

Demography, lifestyle, and medical history were assessed by self-report (18). Prescription medications were verified and weight and blood pressure were measured annually. Fasting blood specimens were analyzed centrally, annually for 4 years and every other year thereafter. For participants providing consent, TaqMan genotyping for the rs7412 and rs429358 single-nucleotide polymorphisms was used to assign APOE-ε4 allele status.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of women and men at their most recent assessment prior to MRI were compared using chi-square and t-tests. Mixed effects models (22,28), controlling for intraindividual correlations among ROIs, were used to estimate ROI-specific and summed volumes and WMH volumes using linear contrasts. These models were also used to estimate ROI-specific and across-ROI mean CBF. The distributions of WMH volumes were skewed. To preserve additivity for summing means, we did not use data transformations to improve the symmetry of WMH distributions, however parallel analyses using offset logarithmic transformations yielded similar findings. Clinic site and interactions between ROIs and both intervention assignment and age were included as covariates in models. An interaction between ROIs and intracranial volume was additionally included as a covariate for ROI volumes: this allows relationships that volumes have with intracranial volume to vary among ROIs, which were markedly different (p < .001). Owing to an imbalance by sex in diastolic blood pressure, and for consistency with prior reports (22), most recent systolic and diastolic blood pressure were included as covariates in analyses of CBF. ROI volume was not included as a covariate when analyzing CBF because it was unrelated (p = .98).

The risk factors that we considered as potential explanators of sex differences were chosen from those examined in earlier Look AHEAD publications (7,22,23). We additionally examined use of biguanides, statins, and aspirin as potential modifiers. Adding BMI at the time of Look AHEAD enrollment as a covariate did not affect results, so it was not included.

We examined the consistency of sex-related differences across subgroups formed by current age, most recent BMI, APOE-ε4 carrier status, and intervention assignment using tests of interactions. Associations that measures had with cognitive function scores were assessed with mixed effects models. Inverse probability modeling was used to assess the sensitivity of findings to missing data (Supplementary Exhibit 1).

Results

Table 1 describes sex differences in factors known or suspected to be related to brain MRI outcomes. Compared with men, women were more likely to be African American, have less formal education, and consume less alcohol. Women and men had similar BMIs, however women had lost a significantly greater percentage of BMI during the trial. Compared with men, they had lower diastolic blood pressures and greater declines in diastolic blood pressure since baseline, and slightly higher HbA1c levels, but similar durations of diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics at the Most Proximal Assessment Prior to MRI: Mean (Standard Deviation) or N (Percent)

| Characteristic | Women N = 224 | Men N = 95 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MRI | 69.0 (6.6) | 69.3 (6.0) | .75 |

| Years, Look AHEAD enrollment to MRI | 10.4 (0.3) | 10.4 (0.5) | .97 |

| Intervention assignment | |||

| Diabetes Support & Education | 114 (50.9%) | 41 (43.2%) | .21 |

| Intensive Lifestyle Intervention | 110 (49.1%) | 54 (56.8%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | ||

| African-American | 62 (27.7%) | 8 (8.4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 150 (67.0%) | 83 (87.4%) | |

| Other, multiple | 12 (5.4%) | 4 (4.2%) | |

| Education | .002 | ||

| High school | 46 (20.5%) | 8 (8.4%) | |

| College graduate | 84 (37.5%) | 28 (29.5%) | |

| Post college | 86 (38.4%) | 57 (60.0%) | |

| Other | 8 (3.6%) | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Alcohol intake at baseline, miss = 85 |

<.001 | ||

| None | 90 (58.4%) | 24 (30.0%) | |

| <1 drink per day | 55 (35.7%) | 43 (53.8%) | |

| ≤2 drinks per day | 9 (5.8%) | 13 (16.2%) | |

| Mean drinks/wk over follow-up | 1.4 (2.2) | 3.9 (4.4) | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| Most recent assessment | 33.6 (5.8) | 32.7 (4.2) | .18 |

| Percent change from baseline | −6.7 (9.4) | −4.1 (8.5) | .02 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Systolic | |||

| Most recent assessment | 130.0 (18.7) | 128.4 (16.9) | .48 |

| Change from baseline | 1.2 (19.9) | −2.2 (18.2) | .15 |

| Diastolic | |||

| Most recent assessment | 66.3 (9.5) | 69.5 (7.6) | .004 |

| Change from baseline | −5.5 (8.4) | −1.6 (9.6) | <.001 |

| Current medication use | |||

| Insulin | 13.8% | 9.4% | .31 |

| Biguanides | 59.2% | 56.5% | .67 |

| Statins | 48.6% | 59.8% | .07 |

| Aspirin | 36.8% | 46.1% | .14 |

| Antihypertensive medications | 83.4% | 88.4% | .25 |

| Duration of diabetes, miss = 3 | .76 | ||

| <5 years | 47.1% | 48.9% | |

| ≥5 years | 51.1% | 51.1% | |

| HbA1c, % | |||

| Most recent assessment | 7.47 (1.55) | 7.10 (1.28) | .047 |

| Change from baseline | 0.15 (1.52) | −0.15 (1.20) | .08 |

| Most recent assessment < 6.5% | 15.2% | 21.8% | .19 |

| APOE-ε4, alleles, miss = 38 | |||

| None | 144 (73.1%) | 66 (78.6%) | .33* |

| 1 | 51 (25.9%) | 18 (21.4%) | |

| 2 | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Years from menopause to MRI, miss = 22 | |||

| 0–9 | 11 (5.4%) | NA | |

| 10–19 | 75 (37.1%) | ||

| 20+ | 116 (57.4%) | ||

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy | |||

| Never | 104 (46%) | NA | |

| Ever | 120 (54%) |

MRI = magnetic resonance images.

*Carriers versus noncarriers.

Table 2 lists results from mixed effects models assessing sex differences in summed ROI-specific volumes, WMH volumes, and mean and ROI-specific CBF. Women had a relatively greater mean (standard error, [95% confidence interval]) difference in summed volumes across the five ROIs of 10.9 (3.9, [3.3, 18.5]) cc (ie, about 1%). Their frontal and parietal lobe volumes were larger (95% percent confidence intervals for sex differences excluded zero). The mean difference in summed WMH volumes between women and men was 1.39 (0.71, [0.00002, 2.78]) cc (ie, about 54%), with confidence intervals excluding zero for the same two lobes. Mean CBF across ROIs was slightly greater among women than men, however the 95% confidence interval for its overall difference did not exclude zero: 2.44 (1.57, [−0.64, 5.50]) mL/100 g/min.

Table 2.

Mean Covariate-Adjusted ROI Volume, WMH Volume, and CBF by Sex

| Region | Volumes (cc)† Mean (SE) | Mean Difference: Women Minus Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Sum over ROIs | 900.8 (1.8) | 890.0 (3.0) | 10.9 (3.9) | [3.3, 18.5]* |

| Frontal lobe | 363.0 (1.1) | 356.4 (1.9) | 6.6 (2.4) | [1.8, 11.4]* |

| Limbic region | 34.4 (0.2) | 34.8 (0.3) | −0.5 (0.4) | [−1.2, 0.3] |

| Occipital lobe | 120.3 (0.4) | 119.9 (0.8) | 0.3 (1.0) | [−1.6, 2.2] |

| Parietal lobe | 177.8 (0.6) | 172.3 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.3) | [2.8, 8.1]* |

| Temporal lobe | 205.2 (0.5) | 206.3 (0.9) | −1.0 (1.1) | [−3.3, 1.2] |

| Region | WMH volumes (cc)‡ Mean (SE) | Mean Difference: Women Minus Men | ||

| Women | Men | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Sum over ROIs | 3.97 (0.39) | 2.58 (0.59) | 1.39 (0.71) | [0.00002, 2.78]* |

| Frontal lobe | 1.82 (0.17) | 1.14 (0.26) | 0.69 (0.31) | [0.06, 1.30]* |

| Limbic region | 0.023 (0.009) | 0.022 (0.009) | 0.001 (0.001) | [−0.000, 0.002] |

| Occipital lobe | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.33 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | [−0.12, 0.06] |

| Parietal lobe | 0.93 (0.12) | 0.47 (0.18) | 0.46 (0.22) | [0.03, 0.89]* |

| Temporal lobe | 0.87 (0.10) | 0.60 (0.16) | 0.28 (0.19) | [−0.09, 0.64] |

| Region | CBF (mL/100 g/min)§ Mean (SE) | Mean Difference: Women Minus Men | ||

| Women | Men | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Overall mean | 51.10 (0.85) | 48.65 (1.30) | 2.44 (1.57) | [−0.64, 5.50] |

| Frontal lobe | 47.69 (0.96) | 45.73 (1.46) | 1.96 (1.77) | [−1.43, 5.44] |

| Limbic region | 54.17 (1.00) | 53.48 (1.52) | 0.70 (1.84) | [−2.92, 4.32] |

| Occipital lobe | 56.30 (1.08) | 50.69 (1.65) | 5.63 (1.99) | [1.71, 9.55]* |

| Parietal lobe | 50.26 (1.06) | 47.88 (1.61) | 2.37 (1.95) | [−1.46, 6.21] |

| Temporal lobe | 46.67 (0.89) | 45.10 (1.35) | 1.57 (1.64) | [−1.66, 4.80] |

Notes: Interactions between sex and ROIs: volume (p < .001), WMH volume (p = .050), CBF (p = .005). CBF = cerebral blood flow, ROI = regions of interest, WMH = white matter hyperintensity.

*Confidence interval excludes 0.

†Adjustment for clinic and interactions of ROIs with intracranial volume, intervention assignment, and age.

‡Adjustment for clinic, ROI volumes, and interactions of ROIs with age and intervention assignment.

§Adjustment for clinic, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and interactions of ROIs with age and intervention assignment.

Overall, estimated sex differences from models fitted with inverse probability weighting (Supplementary Exhibit 2) were similar to those without weighting.

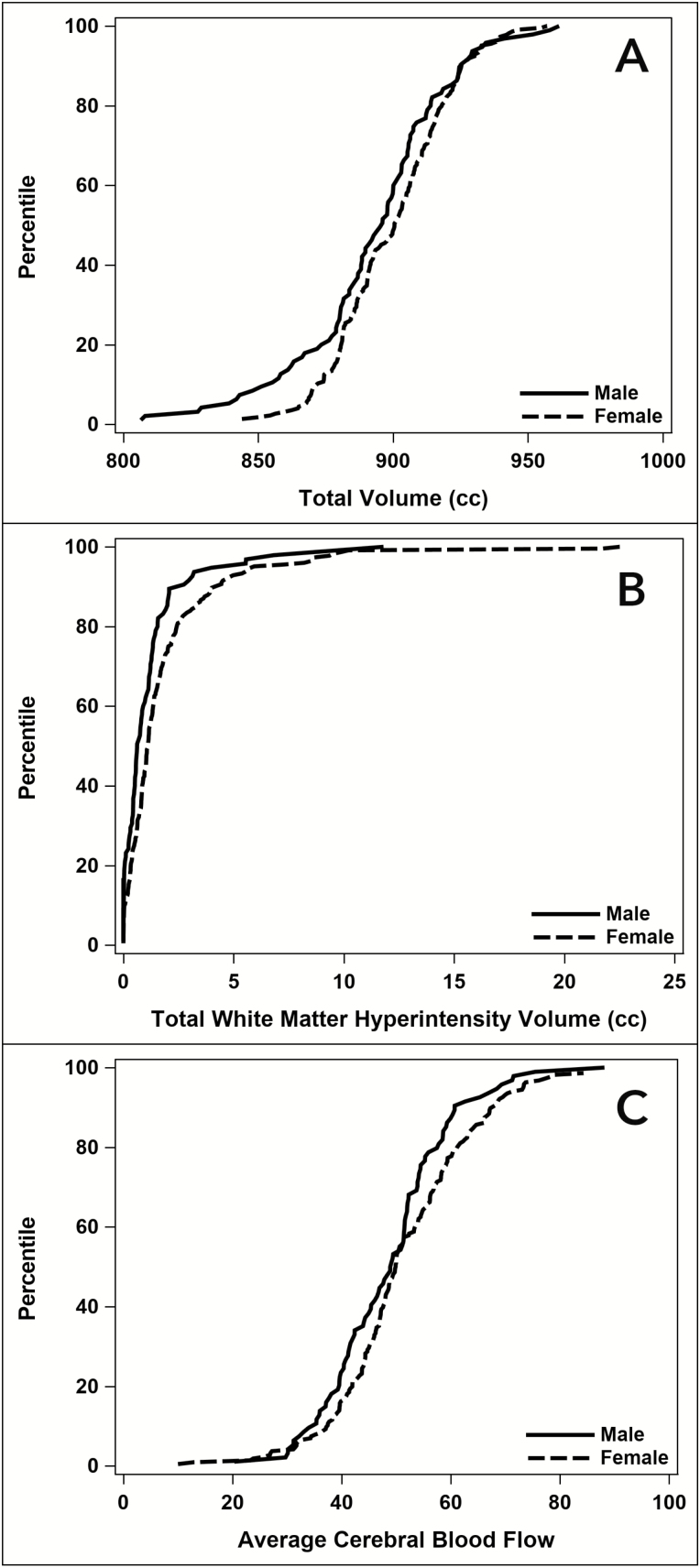

Figures 1A–C portray the cumulative distributions of covariate-adjusted summed ROI and WMH volumes and mean CBF by sex. The distributions of summed ROI volumes and mean CBF for women were shifted toward greater values throughout most of the range.

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution of (A) adjusted summed brain volumes, (B) summed white matter hyperintensity volumes, and (C) mean cerebral blood flows by sex.

Additional covariate adjustment for education, race/ethnicity, most recent and change in diastolic blood pressure, baseline and on-trial alcohol intake, most recent HbA1c, and change in BMI from baseline (sex differences in Table 1) did not materially affect results, as portrayed in Supplementary Exhibit 2. The confidence intervals for mean differences in summed ROI volumes and WMH volumes with additional covariate adjustment continued to exclude zero: mean 14.7 (5.0, [4.9, 24.7]) and mean 1.41 (0.71, [0.02, 2.81]), respectively; See Supplementary Exhibit 3). The confidence interval for CBF did not: mean 2.24 (1.65, [−1.01, 5.48]).

We examined whether sex differences in MRI outcomes varied by age and most recent BMI (with cut points 70 years and 35 kg/m2), intervention assignment, and APOE-ε4 status (carrier vs noncarrier) using tests of interactions (Supplementary Exhibit 4). None reached nominal statistical significance (all p ≥ 0.08), however power was limited.

Table 3 portrays sex differences in cognitive function test scores, without and with adjustment for the MRI outcomes. Women tended to outperform men on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test immediate and delayed memory tests and in composite cognitive function. Covariate adjustment for all MRI outcomes did not materially attenuate differences between sexes seen for any cognitive test without this adjustment (and confidence intervals indicating relatively better performance for women on the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam and Digit Symbol Coding tests now excluded zero). In models including all three MRI outcomes as predictors, summed ROI volumes were positively associated with performance on the Digit Symbol Coding, Stroop, and Trails A and B tests and composite cognitive function. Summed WMH volumes were inversely associated with performance on Rey delayed recall, the Digit Symbol Coding test, and composite cognitive function. Average CBF was inversely associated with the Trails-A test.

Table 3.

Mean Cognitive Function Scores With Adjustment for (a) Age, Education, Race/Ethnicity, Clinic, and Intervention Assignment and (b) With Additional Adjustment for Summed Brain Volumes, Summed WMH Volumes, and Average CBF

| Cognitive Test† | Z-score Mean (SE) | Mean Difference: Women Minus Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Adjustment for age, education, race/ethnicity, clinic, and intervention assignment | ||||

| 3MSE | 0.196 (0.062) | 0.000 (0.097) | 0.195 (0.118) | [−0.037, 0.427] |

| AVLT | ||||

| Immediate | 0.145 (0.067) | −0.399 (0.104) | 0.544 (0.127) | [0.295, 0.793]* |

| Delayed | 0.290 (0.068) | −0.412 (0.107) | 0.702 (0.129) | [0.447, 0.956]* |

| Stroop | 0.098 (0.058) | 0.233 (0.091) | −0.135 (0.111) | [−0.353, 0.083] |

| DSC | 0.190 (0.058) | −0.018 (0.091) | 0.208 (0.111) | [−0.009, 0.426] |

| Trail Making | ||||

| A | 0.139 (0.053) | 0.160 (0.083) | −0.021 (0.101) | [−0.220, 0.178] |

| B | 0.090 (0.060) | 0.081 (0.088) | 0.010 (0.107) | [−0.200, 0.220] |

| Composite | 0.170 (0.041) | −0.024 (0.064) | 0.193 (0.077) | [0.042, 0.346]* |

| Additional adjustment for intracranial volume, summed brain volumes, summed WMH volumes, and mean CBF | ||||

| 3MSE | 0.227 (0.070) | −0.105 (0.119) | 0.332 (0.153) | [0.030, 0.634]* |

| AVLT | ||||

| Immediate | 0.105 (0.073) | −0.316 (0.125) | 0.422 (0.162) | [0.103, 0.740]* |

| Delayed‡ | 0.244 (0.075) | −0.324 (0.127) | 0.570 (0.165) | [0.244, 0.892]* |

| Stroop‡ | 0.148 (0.065) | 0.135 (0.111) | 0.013 (0.143) | [−0.268, 0.295] |

| DSC‡,§ | 0.245 (0.065) | −0.122 (0.111) | 0.367 (0.143) | [0.086, 0.648]* |

| Trail Making | ||||

| A‡,|| | 0.203 (0.058) | 0.032 (0.100) | 0.171 (0.129) | [−0.083, 0.425] |

| B‡ | 0.121 (0.062) | −0.021 (0.106) | 0.142 (0.136) | [−0.126, 0.410] |

| Composite‡,§ | 0.195 (0.045) | −0.090 (0.077) | 0.285 (0.100) | [0.089, 0.481]* |

*Confidence interval excludes 0.

†3MSE: Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; AVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Stroop: Modified Stroop Color and Word Test; DSC: Digit Symbol Coding test.

‡Significant relationship with summed brain volumes (p ≤ .05).

§Significant inverse relationship with summed WMH volumes (p ≤ .05).

||Significant inverse relationship with average CBF (p ≤ .05).

Discussion

Our analysis comparing brain MRI outcomes of older overweight and obese women and men with T2DM who were volunteers for a clinical trial of multidomain lifestyle intervention yielded three principal findings. First, across the five ROIs we examined, women had relatively greater adjusted summed ROI and WMH volumes and slightly (but overall not significantly) greater mean CBF. Second, these sex differences could not be attributed to imbalances in the risk factors we examined and did not vary significantly by age, obesity level, intervention assignment, and APOE-ε4 carriage. Third, although women tended to outperform men on tests of memory and composite cognitive function, these differences could not be attributed to differences in MRI outcomes.

Sex Differences in MRI Outcomes

There is considerable heterogeneity among studies of sex differences in brain volumes, with some reporting women having relatively smaller brain volumes (29), smaller amygdalar and hypothalamic ROI volumes (30), and larger hippocampal volumes (31), however the reasons for any differences are unclear (32). The degree to which T2DM and obesity may differentially affect women’s and men’s brain volumes is unknown. Our findings align with several past reports that global CBF is consistently higher in women than in men (13–15), although this trend did not reach nominal levels of statistical significance when averaged across the five ROIs.

Independence of Sex Differences From Risk Factor Imbalances and Subgrouping

Sex differences in MRI outcomes did not appear to be affected by traditional risk factors such as blood pressure, obesity level, alcohol intake, or measures of glycemic control, nor by changes in these risk factors over the prior ten years. Among women, the MRI outcomes were not associated with years from menopause or prior use of hormone therapy after controlling for age. Differences did not vary significantly between subgroups based on age, BMI, and intervention assignment.

We were surprised that APOE-ε4 did not attenuate differences between women and men with respect to any of the MRI outcomes. Although trends did not reach statistical significance, compared with women, men carrying APOE-ε4 tended to have even worse ROI and WMH volumes and lower CBFs than seen for sex difference comparisons among noncarriers. APOE-ε4 in women, compared with men, has been shown to lead to steeper declines in cognitive function, increased risks for Alzheimer’s disease, and altered brain connectivity (2,33,34). Among those with mild cognitive impairment, APOE-ε4 alleles are more strongly associated with lower hippocampal volumes among women compared with men (35). However, the relationship between APOE genotype and cognition may be altered among individuals with T2DM, for example APOE-ε2 may not be protective (36).

Sex Differences in Cognitive Function

Women outperformed men in tests of memory and overall composite cognitive function in this subset of the Look AHEAD cohort, similarly as seen in the full cohort (35). This is consistent with reports from many studies of adults. Although overall, cognitive functions had modest associations with summed ROI volumes, these did not appear to account for sex differences in cognitive function. Perhaps this is because the MRI outcomes were cross-sectional and did not capture the dynamic and possibly indirect nature of relationships that brain structure and function have with cognitive function. However, this inability to attribute sex differences in cognitive function to differences in MRI outcomes provides some support to the hypothesis that the underlying mechanisms most important to the sex differences in cognitive function are not strongly related to the MRI outcomes we examined. We note, however, that we did not examine subregions (eg, hippocampus), measures of microstructure (eg, with diffusion tensor imaging), or other physiologic measures (eg, default mode network).

Implications of Findings

Our findings here and in our prior report of the markedly lower rate of cognitive impairment among Look AHEAD women compared with men (7) provide several insights. First, sex differences in both the measured MRI outcomes and cognitive impairment could not be attributed to differences in the profiles of the traditional risk factors that were assessed. They also were unrelated to achieved weight loss or assignment to the Look AHEAD multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention, even though this was associated with larger brain volumes, smaller WMH volumes, and greater overall CBF (22,23). As noted earlier, although sex differences in cognitive function were evident, these were not attributable to MRI structural measures and CBF, although power may have been limited. In particular, women tended to outperform men cognitively, particularly on memory tasks, despite greater volumes of WMH. Presence of APOE-ε4 alleles appeared to attenuate differences in cognitive impairment (7), but had no effect on sex differences in MRI outcomes.

In total, these findings suggest that the relatively better cognitive functioning and less cognitive impairment we observed among older women with T2DM may not be driven by mechanisms closely linked to global measures of cerebrovascular disease or brain atrophy, but perhaps to other protective mechanisms that may be countered by the APOE-ε4 genotype. APOE-ε4 disrupts brain insulin signaling, is associated with greater levels of neuroinflammation and gliosis, and alters fatty acid delivery to the brain (35). There is some evidence that these effects are stronger in women (2,37).

Riedel and colleagues (2) hypothesize that the APOE-ε4 positive brain is more dependent on ketone-based energy metabolism (to augment glucose-based metabolism), and that in women, by suppressing the ketogenic system, estrogen may adversely affect brain function in APOE-εε4 carriers compared with noncarriers. Thus, the increased levels of endogenous estrogens associated with overweight and obesity in Look AHEAD women may have adversely affected the energy metabolism of APOE-ε4 carriers compared with non-carriers. This metabolic pathway may have acted on cognitive function somewhat separately from the MRI outcomes we describe.

Limitations

Differential follow-up and missing data may have biased our results: although supporting analyses do not point to any large effects, we cannot rule out the potential that unmeasured factors may have introduced biases. Analyses were not prespecified and should be considered exploratory: to emphasize this we primarily report confidence intervals rather than results from inference, however these are not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Our MRI measures were limited to brain volumes, WMH, and CBF, and we cannot rule out that sex differences in subregions, microstructure, or brain networks could explain sex differences in cognitive performance. The sex differences with respect to brain volumes, while statistically significant, were small. The cohort, as eligible volunteers for a clinical trial, may not represent general populations. Power was limited for assessing differences in MRI outcomes among some subgroups. Analyses were based on cross-sectional relationships.

Summary

In a cohort of overweight and obese adults with T2DM, compared with men, women tended to have greater levels of subclinical cerebrovascular disease, but larger brain volumes and, perhaps, modestly greater CBF. We could not account for these differences with traditional risk factors. These sex differences in brain structure and blood flow did not appear to account for the lower prevalence in of cognitive impairment in women compared with men in the cohort.

Funding

The Look AHEAD Brain MRI ancillary study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: DK092237-01. Additional support was provided bythe Action for Health in Diabetes ADRD Study (Look AHEAD-MIND) R01AG058571.

The Action for Health in Diabetes is supported through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346); and the Wake Forest Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P30AG049638-01A1). JAL was also additionally supported by K24AG045334. HNY was supported by the NIH grants R21AG056518, R01AG055770 and R01AG054434.

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors Contributions: All authors meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

Sponsors Role: Representatives from the Look AHEAD sponsor (NIDDK) reviewed this manuscript prior to submission, serving on the Look AHEAD Publications and Presentations Committee, but had no direct role in its development and final submission.

Conflict of Interest

MAE is a member of the editorial board of The Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Snyder HM, Asthana S, Bain L, et al. Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: a think tank convened by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Riedel BC, Thompson PM, Brinton RD. Age, APOE and sex: triad of risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;160:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, et al. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1556–1560. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Profenno LA, Porsteinsson AP, Faraone SV. Meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease risk with obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290:1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lovejoy JC, Sainsbury A; Stock Conference 2008 Working Group Sex differences in obesity and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Obes Rev. 2009;10:154–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Espeland MA, Carmichael O, Yasar S, et al. ; Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Research Group Sex-related differences in the prevalence of cognitive impairment among overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1184–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manschot SM, Brands AM, van der Grond J, et al. ; Utrecht Diabetic Encephalopathy Study Group Brain magnetic resonance imaging correlates of impaired cognition in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen Y, Zhao B, Yan L, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic and white matter changes of type 2 diabetes revealed by multi-TI arterial spin labeling and double inversion recovery sequence. Front Neurol. 2017;8:717. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Selim M, Jones R, Novak P, Zhao P, Novak V. The effects of body mass index on cerebral blood flow velocity. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0490-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alpert MA, Omran J, Bostick BP. Effects of obesity on cardiovascular hemodynamics, cardiac morphology, and ventricular function. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5:424–434. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0235-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lemaître H, Crivello F, Grassiot B, Alpérovitch A, Tzourio C, Mazoyer B. Age- and sex-related effects on the neuroanatomy of healthy elderly. Neuroimage. 2005;26:900–911. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function, and chemistry. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnes JN. Sex-specific factors regulating pressure and flow. Exp Physiol. 2017;102:1385–1392. doi: 10.1113/EP086531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xing CY, Tarumi T, Meijers RL, et al. Arterial pressure, heart rate, and cerebral hemodynamics across the adult life span. Hypertension 2017;69:712–720. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nebel RA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, et al. Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: a call to action. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1171–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yin ZG, Wang QS, Yu K, Wang WW, Lin H, Yang ZH. Sex differences in associations between blood lipids and cerebral small vessel disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;28:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD; Look AHEAD Research Group Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2456(03)00064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL; Look AHEAD Research Group Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. New Eng J Med. 2013;369:145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L; Look AHEAD Research Group The Look AHEAD Study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity 2006;14:737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wesche-Thobaben JA; The Look AHEAD Research Group The development and description of the diabetes support and education (comparison group) intervention for the Action for Health in Diabetes Trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8:320–329. doi: 10.1177/1740774511405858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Espeland MA, Luchsinger JA, Neiberg RH, et al. Long term impact of intensive lifestyle intervention on cerebral blood flow. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:120–126. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Espeland MA, Erickson K, Neiberg RH, et al. Brain and white matter hyperintensity volumes after 10 years of random assignment to lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:764–771. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coker LH, Espeland MA, Hogan PE, et al. Change in brain and lesion volumes after CEE therapies: the WHIMS-MRI studies. Neurology 2014;82:427–434. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lao Z, Shen D, Liu D, et al. Computer-assisted segmentation of white matter lesions in 3D MR images using support vector machine. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jung Y, Wong EC, Liu TT. Multiphase pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling (MP-PCASL) for robust quantification of cerebral blood flow. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:799–810. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Bray GA, et al. ; Action for Health In Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Movement and Memory Subgroup; Look AHEAD Research Group Long-term impact of behavioral weight loss intervention on cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1101–1108. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD.. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Courchesne E, Chisum HJ, Townsend J, et al. Normal brain development and aging: quantitative analysis at in vivo MR imaging in healthy volunteers. Radiology 2000;216:672–682. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au37672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Horton NJ, et al. Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:490–497. doi. org/10.1093/cercor/11.6.490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Filipek PA, Richelme C, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS Jr. The young adult human brain: an MRI-based morphometric analysis. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:344–360. doi: doi.org/10.1093/cercor/4.4.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Henriksen OM, Jensen LT, Krabbe K, Larsson HB, Rostrup E. Relationship between cardiac function and resting cerebral blood flow: MRI measurements in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2014;34:471–477. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Altmann A, Tian L, Henderson VW, Greicius MD; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Investigators Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:563–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.24135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1178–1189. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fleisher A, Grundman M, Jack CR Jr, et al. Sex, apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 status, and hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:953–957. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palmer Allred ND, Raffield LM, Hardy JC, et al. APOE genotypes associate with cognitive performance but not cerebral structure: diabetes heart study MIND. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2225–2231. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pontifex M, Vauzour D, Minihane AM. The effect of APOE genotype on Alzheimer’s disease risk is influenced by sex and docosahexaenoic acid status. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;69:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.