Abstract

Plants from Alisma species belong to the genus of Alisma Linn. in Alismataceae family. The tubers of A. orientale (Sam.) Juzep, also known as Ze Xie in Chinese and Takusha in Japanese, have been used in traditional medicine for a long history. Triterpenoids are the main secondary metabolites isolated from Alisma species, and reported with various bioactive properties, including anticancer, lipid-regulating, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral and diuretic activities. In this brief review, we aimed to summarize the phytochemical and pharmacological characteristics of triterpenoids found in Alisma, and discuss their structure modification to enhance cytotoxicity as well.

Keywords: triterpenoids, Alisma, structure, anticancer, lipid-regulation

Introduction

Plants from the genus of Alisma Linn. (Alismataceae) are widely distributed in temperate regions and subtropics of the northern hemisphere, belonging to 11 species. Six species were found in China and Asia, including A. canaliculatum, A. gramineum, A. nanum, A. orientale, A. plantago-aquatica and A. lanceolatum (Flora of China Committee, 1992). The tubers of A. orientale, known as Ze Xie in Chinese or Takusha in Japanese, have been used as diuretic and detumescent medications for a long history (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2015). It is also used to treat obesity, diabetes and hyperlipidemia nowadays.

Phytochemical studies have revealed that triterpenoids are dominant components in tubers of Alisma plants. A total of 118 triterpenoids have been isolated and identified from Alisma species so far. Most of them contain protostane tetracyclic aglycones, whereas glycosides are rarely found in other plants. These triterpenoids have been considered as chemotaxonomic markers of the genus (Zhao et al., 2007). A small amount of other kinds of compounds have also been isolated from A. orientale, including diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, polysaccharides, phytosterols, amino acids, flavonoids and fatty acids (Zhang et al., 2017). The presence of triterpenoids attributes to the bioactivities of A. orientales (Tian et al., 2014; Shu et al., 2016), such as alisol A 24-acatate (2), and alisol B 23-acetate (47) (Choi et al., 2019).

Alisols have shown a series of biological activities, such as anticancer (Law et al., 2010), lipid-regulating (Cang et al., 2017), anti-inflammatory (Kim et al., 2016), antibacterial (Jin et al., 2012), antiviral (Jiang et al., 2006), and diuretic activities (Zhang et al., 2017). Since alisol B 23-acetate (47) exhibits a significant anti-tumor activity, structure-based modification on alisol B 23-acetate (47) gives a profound change of activity.

This paper aims to systematically review triterpenoids from Alisma species, involving their phytochemical characteristics, biosynthesis, bioactivities and structure modification.

Triterpenoids

Starting from 1968, triterpenoids have been isolated from Alisma genus successively (Murata et al., 1968). All these compounds contain protostane tetracyclic skeleton with the structural characteristics of trans-fusions for A/B, B/C and C/D rings, α-methyl submitted at C-8, β-methyl at C-10, β-methyl at C-14 and side chain at C-17. At present there are 101 protostane triterpenoids, 12 nor-protostanes, and 5 seco-protostanes reported from Alisma. According to the changes of side chains submitted at C-17, protostane triterpenoids from Alisma are divided into four classes, including open aliphatic chains, epoxy aliphatic chains, spiro hydrocarbon at C-17, and epoxy at C-16, C-23 or C-16, C-24. The individual triterpenoids were detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

A total of 118 triterpenoids isolated and identified from Alisma genus.

| No. | Name | Skeleton structure | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | Double bond position | Source | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTOSTANES WITH OPEN ALIPHATIC CHAINS AT C-17 | |||||||||||

| 1 | alisol A | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a |

| 2 | alisol A 24-acetate | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOAc | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a |

| 3 | alisol A 23-acetate | A | βOH | H | βOAc | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a |

| 4 | 11-deoxyalisol A | A | H | H | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002b |

| 5 | 23-o-methyl alisol A | A | βOH | H | βOMe | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 6 | 25-o-methoxy-alisol A | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OMe | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 7 | 16-oxo-alisol A | A | βOH | O | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 8 | 16-oxo-alisol A-23-acetate | A | βOH | O | βOAc | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2015 |

| 9 | 16-oxo-alisol A-24-acetate | A | βOH | O | βOH | βOAc | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2015 |

| 10 | 16-oxo-11-deoxy- alisol A | A | H | O | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 11 | 5β,29-dihydroxy alisol A | A (5βOH) | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OH | OH | Δ13(17) | A. plantago-aquatica | Wang et al., 2017b |

| 12 | 25-o-butyl alisol A | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OBu | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Zhang et al., 2017 |

| 13 | alisol E | A | βOH | H | βOH | αOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1993 |

| 14 | alisol E-23-acetate | A | βOH | H | βOAc | αOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1993 |

| 15 | alisol E-24-acetate | A | βOH | H | βOH | αOAc | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1993 |

| 16 | 25-o-ethylalisol A | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OEt | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 17 | alisol H | A | H | O | O | H | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 |

| 18 | 16β-methoxyalisol E | A | βOH | βOMe | βOH | αOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 19 | 16β,25-dimethoxyalisol E | A | βOH | βOMe | βOH | αOH | OMe | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 20 | 16β-hydroperoxyalisol E | A | βOH | βOOH | βOH | αOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 21 | 11,24-dihydroxy-alisol H | A | βOH | O | O | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 |

| 22 | alisol T | A | βOH | βOMe | OH | H | OH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 23 | alismanin I | A | βOH | H | O | OH | H | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yi et al., 2019 |

| 24 | 15,16-dihydroalisol A. | A | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ13(17), 15(16) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 25 | alismanol D | A | H | H | H | αOH | OH | H | Δ9(11), 12(13) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 26 | 24-epi-alismanol D | A | H | H | H | βOH | OH | H | Δ9(11), 12(13) | A. orientalis | Xin et al., 2018 |

| 27 | alismanol A | A | H | O | O | αOH | OH | H | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 28 | alismanol C | A | H | O | βOAc | αOH | OH | H | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 29 | 16-oxo-11-anhydro alisol A | A | H | O | βOH | βOH | OH | H | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 30 | 16-oxo-11-anhydroalisol A 24-acetate | A | H | O | βOH | βOAc | OH | H | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Ma et al., 2016 |

| 31 | 3-oxo-11β,23-dihydroxy-24,24-dimethyl−26,27-dinorprotost-13(17)-en-25-oic-acid | A | βOH | O | H | βOH | COOH | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2013 |

| 32 | alismanin B | A | βOH | O | H | βOH | H | H | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Wang et al., 2017a |

| 33 | 25-anhydroalisol A | B | βOH | H | βOH | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a | ||

| 34 | 11-acetate-25-anhydroalisol A | B | βOAc | H | βOH | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a | ||

| 35 | 24-acetate-25-anhydroalisol A | B | βOH | H | βOH | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a | ||

| 36 | 11-deoxy-25-anhydro-alisol E. | B | H | H | βOH | αOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | ||

| 37 | alisol X | B | βOH | H | H | O | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Xu et al., 2012 | ||

| 38 | 23-acetate-25-anhydroalisol E | B | H | H | βOAc | αOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Han et al., 2013 | ||

| 39 | 24-acetate-25-anhydroalisol E | B | H | H | βOH | αOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Han et al., 2013 | ||

| 40 | alismanol B | B | H | O | βOH | αOH | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | ||

| 41 | 7-oxo-16-oxo-11-anhydro alisol A | C | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | |||||||

| 42 | alismanol M | D | A. orientale | Xin et al., 2016 | |||||||

| 43 | 13,17-epo-alisol A | E | βOH | αOH | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002b | |||||

| 44 | 13,17-epoalisol A 24-acetate | E | βOH | αOAc | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002b | |||||

| 45 | 11-deoxy-13,17-epoxy-alisol A | E | H | βOH | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 | |||||

| PROTOSTANES WITH EPOXY ALIPHATIC CHAINS AT C-17 | |||||||||||

| 46 | alisol B | F | βOH | H | H | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 47 | alisol B 23-acetate | F | βOH | H | H | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 48 | 11-deoxy-alisol B-23-acetate | F | H | H | H | H | βMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 49 | 11-deoxy-alisol B | F | H | H | H | H | βMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 50 | 16β-acetoxy alisol B | F | βOH | H | βOAc | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Cang et al., 2017 |

| 51 | 16α-acetoxy alisol B | F | βOH | H | αOAc | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Cang et al., 2017 |

| 52 | 16β-hydroxyalisol B-23-acetate | F | βOH | H | βOH | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng and Lou, 2001 |

| 53 | 16β-methoxyalisol B-23- acetate | F | βOH | H | βOMe | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Jin et al., 2012 |

| 54 | 16β-ethoxy alisol B 23-acetate | F | βOH | H | βOEt | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Zhang et al., 2017 |

| 55 | alisol C | F | βOH | H | O | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 56 | 11-deoxy-alisol C-23-acetate | F | H | H | O | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 |

| 57 | 11-deoxy-alisol C | F | H | H | O | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. plantago-aquatica | Fukuyama et al., 1988 |

| 58 | 20-hydroxyalisol C | F | βOH | H | O | OH | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 |

| 59 | alisol C 23-acetate | F | βOH | H | O | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. plantago-aquatica | Fukuyama et al., 1988 |

| 60 | alisol M-23-acetate | F | βOH | βOH | O | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 61 | alisol N-23-acetate | F | βOH | βOH | H | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 62 | 16β-hydroperoxyalisol B | F | βOH | H | βOOH | H | αMe | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 63 | 16β-hydroperoxyalisol B 23-acetate | F | βOH | H | βOOH | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 |

| 64 | alisol L | F | H | H | O | H | αMe | βOH | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2015 |

| 65 | alisol L-23-acetate | F | H | H | O | H | αMe | βOAc | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 |

| 66 | 13β,17β-epoxy-alisol B | G | βOH | βOH | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 | |||||

| 67 | 13β,17β-epoxy-23- acetate-alisol B | G | βOH | βOAc | A. orientale | Jin et al., 2012 | |||||

| 68 | 11-deoxy-13β,17β-epoxy-alisol B 23-acetate | G | H | βOAc | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 | |||||

| 69 | alisol D | G | βOH | αOAc | A. plantago-aquatica | Fukuyama et al., 1988 | |||||

| 70 | alisol D 11-acetate | G | βOAc | αOAc | A. plantago-aquatica | Fukuyama et al., 1988 | |||||

| 71 | 11-deoxyalisol D | G | H | αOAc | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 | |||||

| 72 | alisol J−23 acetate | H | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 | |||||||

| 73 | alisol K-23-acetate | I | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 | |||||||

| 74 | alismanol O | J | H | A. orientale | Xin et al., 2016 | ||||||

| 75 | alismanol P | J | αOH | A. orientale | Xin et al., 2016 | ||||||

| 76 | alisolide H | K | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||||

| 77 | alisolide G | L | O | αOAc | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||

| 78 | alisol Q 23-acetate | L | O | βOAc | A. orientale | Jin et al., 2012 | |||||

| 79 | alisol S 23-acetate | L | βOH | βOAc | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 | |||||

| 80 | alisolide I | M | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||||

| 81 | alismaketone A-23-acetate | N | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1997 | |||||||

| PROTOSTANES WITH SPIRO HYDROCARBON AT C-17 | |||||||||||

| 82 | alismanol Q | O | A. orientale | Xin et al., 2016 | |||||||

| 83 | alisol U | P | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 | |||||||

| 84 | alisol V | Q | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 | |||||||

| 85 | alisolide D | R | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||||

| 86 | alisolide E | S | βOH | Δ12(13) | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||

| 87 | alisolide F | S | H | Δ9(11), 12(13) | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | |||||

| 88 | neoalisol | T | βOH | βOH | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a | |||||

| 89 | neoalisol 11.24-diacetate | T | βOAc | βOAc | A. orientalis | Peng et al., 2002a | |||||

| PROTOSTANES WITH FUSED RING AT C-16 AND C-17 | |||||||||||

| 90 | 16,23-oxidoalisol B | U | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Nakajma et al., 1994 | |||||

| 91 | alisol I | U | βH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1999 | |||||

| 92 | alisol F | V | βOH | βOH | OH | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1993 | |||

| 93 | alisol F-24-acetate | V | βOH | βOAc | OH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Peng and Lou, 2001 | |||

| 94 | 25-o-methylalisol F | V | βOH | βOH | OMe | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Chen et al., 2018 | |||

| 95 | 11-anhydroalisol F | V | H | βOH | OH | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientalis | Hu et al., 2008a | |||

| 96 | alisol O | V | H | βOAc | OH | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. plantago-aquatica | Jiang et al., 2006 | |||

| 97 | 25-anhydroalisol F | W | βOH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Hu et al., 2008a | |||||

| 98 | 11,25-anhydro-alisol F | W | H | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientalis | Hu et al., 2008b | |||||

| 99 | alismaketone B-23-acetate | X | βOH | αOAc | Δ13(17) | A. orientale | Matsuda et al., 1999 | ||||

| 100 | alismanol E | X | H | O | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | ||||

| 101 | alismanol J | Y | A. orientalis | Zhang et al., 2017 | |||||||

| NOR-PROTOSTANES | |||||||||||

| 102 | alismanol H | Z | H | Me | A. orientalis | Zhang et al., 2017 | |||||

| 103 | alismanin A | Z | C6H5 | H | A. orientale | Wang et al., 2017a | |||||

| 104 | alisolide A | a | O | βOH | C-17R | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | ||||

| 105 | alisolide B | a | O | βOOH | C-17S | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | ||||

| 106 | alisolide C | a | βOH | βOH | C-17S | A. plantago-aquatica | Jin et al., 2019 | ||||

| 107 | alisolide | b | A. orientalis | Xin et al., 2018 | |||||||

| 108 | 17-epi-alisolide | c | A. orientalis | Xin et al., 2018 | |||||||

| 109 | alismanol F | d | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | |||||||

| 110 | alismanol G | e | H | O | Ac | Δ11(12), 13(17) | A. orientale | Mai et al., 2015 | |||

| 111 | alismanol I | e | βOH | O | OH | Δ13(17) | A. orientalis | Zhang et al., 2017 | |||

| 112 | alisol R | e | βOH | H | O | Δ12(13) | A. orientale | Li et al., 2017 | |||

| 113 | 13β,17β-epoxy-24,25,26,27 -tetranor-alisol A 23-oic acid | f | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2007 | |||||||

| SECO-PROTOSTANES | |||||||||||

| 114 | alismanin C | g | A. orientale | Wang et al., 2017a | |||||||

| 115 | alismaketone C-23-acetate | h | A. orientale | Matsuda et al., 1999 | |||||||

| 116 | alismalactone-23-acetate | i | H | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1997 | ||||||

| 117 | 3-methyl-alismalactone 23-acetate | i | Me | A. orientale | Yoshikawa et al., 1997 | ||||||

| 118 | alisol P | j | A. orientale | Zhao et al., 2007 | |||||||

Protostanes With Open Aliphatic Chains at C-17

Forty-five protostanes with open aliphatic chains at C-17 (1–45) have been identified as shown in Figure 1. Alisol A (1) is a representative compound of this type. Hydroxyl groups may substitute at C-29 (11) (Wang et al., 2017b), disubstitute at C-23/C-24 (19) and C-23/C-25 (43-45) (Nakajma et al., 1994; Peng et al., 2002b), or trisubstitute at C-23, C-24, and C-25 (41, 42). The hydroxyl group at C-23 or C-24 is easily acetylated. Moreover, double bond may form at C-25 and C-26_(38, 39) (Han et al., 2013), or C-25 may be substituted by carboxyl group (31) (Zhao et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the protostanes with open aliphatic chains at C-17.

Carbonyl groups substitute at C-16 (8, 9) (Zhao et al., 2015), disubstitute at C-7/C-16 (41) (Mai et al., 2015) or C-16/C-23 (21) (Yoshikawa et al., 1999), or substitute at C-24 (37) (Xu et al., 2012) or C-23 (23) (Yi et al., 2019). Hydroxymethyl groups substitute at C-16 (18) (Li et al., 2017) or disubstitute at C-16/C-25 (19).

Protostanes With Epoxy Aliphatic Chains at C-17

Thirty-six protostanes with epoxy aliphatic chains at C-17 (46–81) have been found in the genus of Alisma and their structures are listed in Figure 2. Alisol B 23-acetate (47) is a representative compound of this type. Epoxy group usually forms at C-24 and C-25 (46–73, 77–79, 81) (Fukuyama et al., 1988), and C-23 may be substituted by hydroxyl (66) or acetoxyl group (67–71).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the protostanes with epoxy aliphatic chains at C-17.

Except for epoxy ring, tetrahydrofuran ring from C-20 to C-24 (74, 75) and seven-membered peroxic ring from C-20 to C-25 (76) are also existed in the side chains at C-17.

Protostanes With Spiro Hydrocarbon at C-17

Eight protostanes with spiro hydrocarbon at C-17 (82–89) have been isolated from the genus of Alisma as shown in Figure 3. Oxaspiro-nonane moiety is generated between D ring and its side chain with C-17 as spiro hydrocarbon. Methyl group substituted at C-20 with α- (82) (Xin et al., 2016) or β- (85) (Jin et al., 2019) conformation. Alisol U (83) differs from alisol V (84) by forming an epoxy at C-24 and C-25.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the protostanes with spiro hydrocarbon at C-17.

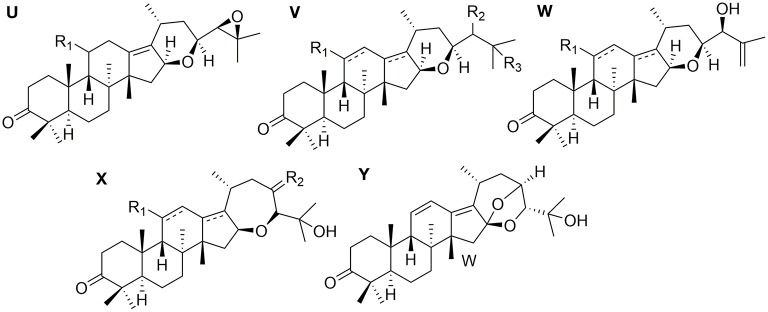

Protostanes With Fused Ring at C-16 and C-17

Twelve protostanes with fused-ring at C-16 and C-17 (90–101) have been isolated from Alisma as shown in Figure 4. Tetrahydropyrane ring is fused at C-16 and C-17 (90–98) (Yoshikawa et al., 1993; Peng and Lou, 2001; Hu et al., 2008a,b; Chen et al., 2018). Oxacycloheptane ring is fused at C-16 and C-17 (99–101). Alismanol J (101) differs from alismaketone B-23-acetate (99) by forming an oxygen bridge between C-16 and C-23.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of the protostanes with fused ring at C-16 and C-17.

Nor- and seco-protostanes

Twelve nor-protostanes (102–113) have been found in Alisma, including two demethyl-protostanes (102, 103) and ten tetranorprotostanes (104–113). Among C-2 may be submitted by carbanyl group (109) (Mai et al., 2015). The configuration of C-17 is determined (107, 108) (Xin et al., 2018).

Only five seco-protostanes (114–118) have been known in Alisma, including two 13, 17-seco-protostanes (114, 115) (Matsuda et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2017a) and three 2, 3-seco-protostanes (116–118) (Yoshikawa et al., 1997). Their structures were detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of the nor- and seco-protostanes.

Biosynthesis

Alisma triterpenoids is commonly biosynthesized through mevalonic aid (MVA) pathway (Zhang et al., 2018) as shown in Figure 6. Three molecules of acetyl-CoA are catalyzed by enzymes to form mevalonate acid (MVA) (Vinokur et al., 2014). It is catalyzed by mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase to produce isopentyl pyrophosphate (IPP), which reacts with dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) to generate geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) by farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase of A. orientale (AOFPPS) (Peng et al., 2018). Squalene is synthesized by squalene synyase of A. orientale (AOSS) (Shen et al., 2013), which is then catalyzed by squalene epoxidase of A. orientale (AOSE) to produce 2,3-oxidosqualeneand further to form protostane tetracyclic skeleton (Zhang et al., 2018). AOFPPS and AOSS are rate-limiting enzymes in Alisma triterpenoids biosynthesis pathway (Zhou et al., 2018).

Figure 6.

Biosynthesis pathway of Alisma triterpenoids.

Fresh materials of A. orientalis are naturally rich in alisol B 23-acetate (47) (Zhu and Peng, 2006), which can convert into alisol A 24-acetate (2), alisol A (1), and alisol B (46) after processing at high temperature (Zheng et al., 2006). Other triterpenoids, such as alisol A (1) (Peng et al., 2002a) and their derivatives, were formed during the drying process (Yoshikawa et al., 1994).

Bioactivities

Alisma orientale is traditionally used to treat oliguria, edema, gonorrhea with turbid urine, leukorrhea, diarrhea, dizziness and hyperlipidemia (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2015). Modern pharmacological studies have demonstrated its diuretic and lipid-lowering efficiency, together with anticancer, lipid-regulating, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral activities.

Anticancer Activities

Recently, the experiments in vitro highlight that alisols induce apoptosis and autophagy in human tumor cells, such as lung cancer (Wang et al., 2018), ovarian cancer (Zhang et al., 2016), and prostate cancer (Huang et al., 2006) cell lines. The cytotoxicities of alisol B 23-acetate (47), cancer cell lines, including L1210 and K562 leukemia alisol C 23-acetate (59), alisol B (46) and alisol A 24-acetate (2) are examined on several cells, B16-F10 melnoma cells, A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells, SK-OV3 ovarian cells, HT 1080 fibrosarcoma cells. The results show that alisol B 23-acetate (47), alisol C 23-acetate (59) and alisol A 24-acetate (2) have weaker inhibitory activities against all the tested cancer cells with ED50 values in the range of 10~20 μg/ml, while alisol B (46) exhibits significant effect on SK-OV3, B16-F10, and HT1080 with ED50 values of 7.5, 7.5, and 4.9 μg/ml, respectively (Lee et al., 2001). Moreover, alisol F 24-acetate (93) and alisol B 23-acetate (47) are found inducing cell apoptosis via inhibiting P-glycoprotein mediation and reversing the multidrug resistance in cancer cell lines (Wang et al., 2004; Hyuga et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2016).

Alisol B (46) targets on Ca2+-ATP enzymes in the sarcoplasmic reticulum or endoplasmic reticulum to induce autophagy of cancer cells (Law et al., 2010). This compound can also induce cell apoptosis by inhibiting the invasion and metastasis of SGC7901 cells (Xu et al., 2009).

Alisol B 23-acetate (47) can inhibit the proliferation of PC-3 prostate cancer (Huang et al., 2006), and induce the apoptosis of lung cancer A549 and NCI-H292 cells through the mitochondrial caspase pathway (Wang et al., 2018). Alisol B 23-acetate (47) obviously inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cell lines and induces accumulation of the G1 phase in a concentration-dependent manner. The protein levels of cleaved poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) and the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 are up-regulated, while the levels of CDK4, CDK6 and cyclin D1 are down-regulated after alisol B 23-acetate (47) treatment. Moreover, it can up-regulate the expression levels of IRE1α and Bip, and down regulate MMP-2 and MMP-9 in a dose- and time- dependent manner (Zhang et al., 2016). However, current studies of Alisma triterpenoids are limited into drug screening in vitro, and their anticancer activities need to be validated in vivo.

Lipid-Lowering Effects

One of A. orientale traditional effects is to treat hyperlipidemia. Studies have shown that the extracts of A. orientale tubers have potential effects on hyperlipidemia diseases (Park et al., 2014; Jang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Miao et al., 2017). Alisol B 23-acetate (47) and alisol A 24-acetate (2) reduce the levels of TC and LDL-C in hyperlipidemia mice via inhibiting the activity of HMG-CoA reductase (Murata et al., 1970; Xu et al., 2016). According to the evaluations of alisols on inhibiting pancreatic lipase, the IC50 of alisol F 24-acetate (93) on pancreatic lipase was 45.5 μM (Cang et al., 2017). Studies results show that alisol B 23-acetate (47) can bound plasma protein (Xu et al., 2014).

Alisol A (1), alisol A 24-acetate (2) and alisol B (46) can decrease TG level in plasma by improving lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity (Xu et al., 2018). The effects of alisols with epoxy aliphatic chain at C-17 on LPL are stronger than those with an open aliohatic chain at C-17. Hydroxyl groups submitted at C-14, C-22, C-28, C-30, and an acetyl group at C-29 are necessary for lipid-regulation action of alisols.

Anti-inflammatory

Alisol B 23-acetate (47) prevents the production of NO in RAW264.7 cells by inhibiting iNOS mRNA expression (Kim et al., 1999). Alisol A 24-acetate (2) effectively alleviates liver steatosis by down-regulating SREBP-1c, ACC, FAS genes and up-regulating CPT1 and ACOX1 genes to activate AMPK signaling pathway and inhibit inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 levels (Zeng et al., 2016). In addition, alisol B (46) and alisol B 23-acetate (47) significantly inhibit the production of leukotriene and the release of β-hexosaminidase in the concentrations of 1–10 mM (Lee et al., 2012).

Antibacterial

Alisol B (46), alisol B 23-acetate (47), alisol C 23-acetate (59), and alisol A 24-acetate (2) have significant bacteriostatic actions on four gram positive and four gram negative antibiotic resistant strains with the MICs ranged from 5 to 10 μg/ml (Jin et al., 2012). In addition, alisol A (1), 25-o-ethylalisol A (16), 11-deoxyalisol A (4), alisol E 24-acetate (15) and 25-anhydroalisol F (97) fight off gram-positive strains of bacillus subtilis and staphylococcus aureus with MICs ranged from 12.5 to 100 mg/ml (Ma et al., 2016).

Antiviral

Studies have shown that alisols from A. orientale exhibit obvious anti-hepatitis b virus effect (Jiang et al., 2006). Alisol F (92) and alisol F 24-acetate (93) significantly inhibit the secretion of HBV surface antigen with an IC50 value of 7.7 and 0.6 μM, and HBVe antigen secretion with an IC50 value of 5.1 and 8.5 μM, respectively. A series of derivatives of alisol A (1) obtained after structural modification also showed potential effect (Zhang et al., 2008, 2009).

Structure Modification

Alisol B 23-acetate can induce apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cell lines (Xu et al., 2015), and structure modification on alisol B 23-acetate (47) allows to obtain a diverse of derivatives (Lee et al., 2002). Alisol B 23-acetate (47) reacts with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature to gain 13β, 17β-epoxy-23-acetate-alisol B (67), and reacts with NH2OH.HCl in pyridine and MeOH to achieve amination at C-3. Deacetylation of alisol B 23-acetate (47) by NaOH yields alisol B (46). Although there is no significant difference of inhibition effect on B16-F10 and HT1080 cell lines between 13β, 17β-epoxy-23-acetate-alisol B (67) (ED50 values of 17 and 18 μg/ml) and alisol B 23-acetate (47) (ED50 values of 20 μg/ml, respectively), alisol B (46) (B16-F10 and HT1080 with ED50 values of 5.2 and 3.1 ug/ml), amination at C-3 of alisol B 23-acetate (47) (with ED50 values of 7.5 and 5.1 ug/ml) show exhibited greater activation against B16-F10 and HT1080 cancer cells. It indicates that deacetylation of C-23 and amination at C-3 significantly enhance the inhibition effect on B16-F10 and HT1080 cell lines.

Four hydroxyl groups of alisol A (1) are usually the target sites for modification by reacting with acetic anhydride in N, N′- dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and 4-dimethylamnopyridine. Alisol A (1) can also dehydrate by SOCl2 in the presence of anhydrous pyridine. The assessments of anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) activities suggest alisol A (1) analogs with acetoxyl groups at C-11, C-23, C-24 or the epoxy ring at C-13 and C-17 increase the effects on HBV. Dehydration at C-25/C-26 enhances its sensitivity on HBV (Zhang et al., 2008, 2009).

Biotransformation of alisol A (1) also derives a series of active compound by several bacteria strains, such as C. elegans AS 3.2028 and P. janthinellum AS 3.510. Alisol A (1) can inhibit the proliferation of HCE-2 cells on the IC50 of 99.65 ± 2.81 μM (Zhang et al., 2017). The activity screening results reveal hydroxylation at C-7 and C-12 increases the inhibiting effects of alisol A (1) on human carboxylesterase 2 (IC50 values of 7.39 ± 1.21 and 3.73 ± 0.76 μM) and the acetyl group at C-23 or C-24 also increases its inhibition effect on HCE-2 cells (IC50 values of 3.78 ± 0.21 and 6.11 ± 0.46 μM).

Taken together, epoxidation at C-13 and C-17, hydroxylation at C-23, C-7/C-12, amination at C-3, and dehydration at C-25/C-26 contribute to the activities of protostane tetracyclic skeleton of A. orientale, including anticancer activity, anti-hepatitis B virtus, and the inhibiting activity on human carboxylesterase 2.

Conclusion

The present work systematically summarized the information concerning the phytochemistry, bioactivities and structure modification of triterpenoids in Alisma species. To date, more than 100 protostane-type terterpenoids have been isolated and identified. Alisols are reported with anticancer, lipid-regulating, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. Structure modification might contribute to the investigation of the therapeutic potential of alisols.

Author Contributions

MJ designed the review and was responsible for the study conception. PW and MJ wrote the paper. PW, TS, and RS contributed to summarizing the phytochemistry and structure modification studies on triterpenoids. MH, RW, and JL contributed to summarizing the bioactivity studies on triterpenoids.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National major new drug creation science and technology major special support project (Nos. 2018ZX09735-002 and 2018YFC1707904) and the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (No. 18JCZDJC97700).

References

- Cang J., Wang C., Huo X. K., Tian X. G., Sun C. P., Deng S., et al. (2017). Sesquiterpenes and triterpenoids from the rhzomes of Alisma orientalis and their pancreatic lipase inhibitory activities. Phytochem. Lett. 19, 83–88. 10.1016/j.phytol.2016.12.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Yang T., Wang M. C., Chen D. Q., Yang Y., Zhao Y. Y. (2018). Novel RAS inhibitor 25-O-methylalisol F attenuates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tubulo-interstitial fibrosisi by selectively inhibiting TGF-β-mediated Smad3 phosphorylation. Phytomedicine 42, 207–218. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission (2015). Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. Beijing: China Medical Science. [Google Scholar]

- Choi E., Jang E., Lee J. H. (2019). Pharmacological activities of Alisma orientale against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome: literature review. Evid. Based Comple. Alternat. Med. 2019:2943162. 10.1155/2019/2943162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora of China Committee (1992). Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press Beijing; 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama Y., Pei-Wu G., Rei W., Yamada T., Nakagawa K. (1988). 11-deoxyalisol C and alisol D: new protostane-type triterpenoids from Alisma plantago-aquatica. Planta Med. 1988, 445–447. 10.1055/s-2006-962495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. W., Kwun M. J., Kim K. H., Choi J. Y., Oh S. R., Ahn K. S., et al. (2013). Ethanol extract of alismatis rhizoma reduces acute lung inflammation by suppressing NF-κB and activating Nrf2. J. Ethnopharmacol. 146, 402–410. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. Y., Guo Y. Q., Gao W. Y., Chen H. X., Zhang T. J. (2008b). A new triterpenoid from Alisma orientalis. Chin. Chem. Lett. 19, 438–440. 10.1016/j.cclet.2008.01.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. Y., Guo Y. Q., Gao W. Y., Zhang T. J., Chen H. X. (2008a). Two new triterpenes from the rhizomes of Alisma orientalis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 10, 487–790. 10.1080/10286020801948441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. T., Huang D. M., Chueh S. C., Teng C. M., Guh J. H. (2006). Alisol B acetate, a triterpene from alismatis rhizoma, induces bax nuclear translocation and apoptosis in human hormone-resistant prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Cancer Lett. 231, 270–278. 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyuga S., Shiraishi M., Hori A., Hyuga M., Hanawa T. (2012). Effect of kampo medicines on MDR-1-mediated multidrug resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma HuH-7/PTX cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 35, 1729–1739. 10.1248/bpb.b12-00371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang M. K., Han Y. R., Nam J. S., Han C. W., Kim B. J., Jeong H. S., et al. (2015). Protective effect of Alisma orientale extract against hepatic steatosis via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 26151–26165. 10.3390/ijms161125944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. Y., Zhang X. M., Zhang F. X., Liu N., Zhao F., Zhou J., et al. (2006). A new triterpene and anti- hepatitis B virus active compounds from Alisma orientalis. Plant Med. 72, 951–954. 10.1055/s-2006-947178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. G., Jin Q. L., Kim A. R., Choi H., Lee J. H., Kim Y. S., et al. (2012). A new triterpenoid from Alisma oientale and their antibacterial effect. Arch. Pharm. Res. 35, 1919–1926. 10.1007/s12272-012-1108-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q. H., Zhang J. Q., Hou J. J., Lei M., Liu C., Wang X., et al. (2019). Novel C-17 spirost protostane-type triterpenoids from Alisma plantago-aquatica with anti-inflammatory activity in Caco-2 cells. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 9, 809–818. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. H., Song H. H., Ahn K. S., Oh S. R., Sadikot R. T., Joo M. (2016). Ethanol extract of the tuber of Alisma orientale reduces the pathologic features in a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mouse model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 188, 21–30. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N. Y., Kang T. H., Pae H. O., Choi B. M., Chung H. T., Myung S. W., et al. (1999). In vitro inducible nitric oxide synthesis inhibitors from Alismatis rhizoma. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 22, 1147–1149. 10.1248/bpb.22.1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law B. Y. K., Wang M. F., Ma D. L., Al-Mousa F., Michelangeli F., Cheng S. H., et al. (2010). Alisol B, a novel inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) ATPase pump, induces autophagy, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 718–730. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Kwon O. S., Jin H. G., Woo E. R., Kim Y. S., Kim H. P. (2012). The rhizomes of Alisma orientale and Alisol derivatives inhibit allergic response and experimental atopic dermatitis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 35, 1581–1587. 10.1248/bpb.b110689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. M., Kho Y. H., Min B. S., Kim J. H., Na M. K., Kang S. J., et al. (2001). Cytotoxic triterpenoides from Alismatis rhizome. Arch. Pharm. Res. 24, 524–526. 10.1007/BF02975158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. M., Min B., Bae K. (2002). Chemical modification of alisol B 23-acetate and their cytotoxic activity. Arch. Pharm. Res. 25, 608–612. 10.1007/BF02976929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. M., Chen X. J., Luo D., Fan M., Zhang Z. J., Peng L. Y., et al. (2017). Protostane-type triterpenoids from Alisma orientale. Chem. Biodivers. 14:e1700452. 10.1002/cbdv.201700452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Jin S. N., Song C. W., Chen C., Zhang Y., Xiang Y., et al. (2016). The metabolic change of serum lysophosphatidylcholines involved in the lipid lowering effect of triterpenes from Alismatis rhizoma on high-fat diet induced hyperlipidemia mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 177, 10–18. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. J., Han L., Bi X. X., Wang X. B., Mu Y., Guan P. P., et al. (2016). Structures and biological activities of the triterpenoids and sesquiteropenoids from Alisma orientale. Phytochemistry 131, 150–157. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai Z. P., Zhou K., Ge G. B., Wang C., Huo X. K., Dong P. P., et al. (2015). Protostane triterpenoids from the rhizome of Alisma orientale exhibit inhibitortory effects on human carboxylesterase2. J. Nat. Prod. 78, 2372–2380. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H., Kageura T., Toguchida I., Murakami T., Kishi A., Yoshikawa M. (1999). Effects of sesquiterpenes and triterpenes from the rhizome of Alisma orientale on nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages: absolute stereostructures of alismaketones B 23-acetate and -C 23-acetate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 3081–3086. 10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00536-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao H., Zhang L., Chen D. Q., Chen H., Zhao Y. Y., Ma S. C. (2017). Urinary biomarker and treatment mechanism of rhizoma alismatis on hyperlipidemia. Biomed. Chromatograp. 31:e3829. 10.1002/bmc.3829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T., Shinohara M., Hirata T., Kamiya K., Nishikawa M., Miyamoto M. (1968). New triterpenes of alisma plantago-aquatica L. Var. Orientale samuels. Tetrahedron Lett. 9, 103–108. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)98735-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T. Y., Imai T., Hirata T., Miyamoto M. (1970). Biological-active trieterpenes of Alismatis rhizoma.I. isolation of the Alisols rhizoma. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 18, 1347–1353. 10.1248/cpb.18.1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajma Y., Satoh Y., Katsumata M., Tsujiyama K., Ida Y., Shoji J. (1994). Terpenoids of Alisma Orientale rhizome and the crude drug Alismatis Rhizoma. Phytochemistry 36, 119–127. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97024-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G. X., Li T. T., Zeng Q. Q., Wang X. M., Zhu Y. (2016). Alisol F 24 acetate enhances chemosensitivity and apoptosis of MCF-7/DOX cell by inhibiting P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux. Molecules 21:183 10.3390/molecules21020183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. J., Kim M. S., Kim H. R., Kim J. M., Hwang J. K., Yang S. H., et al. (2014). Ethanol extract of Alimatis rhizome inhibits adipocyte differentiation of OP9 cells. Evid. Based Comple. Altern. Med. 2014:415097 10.1155/2014/415097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng B., Nielsen L. K., Kampranis S. C., Vickers C. E. (2018). Engineered protein degradation of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase is an effective regulatory mechanism to increase monoterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. 47, 83–93. 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G. P., Lou F. C. (2001). Study on triterpenes in rhizoma alismatis from Sichuan. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 13, 1–4. 10.1633/j.1001-6880.2001.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G. P., Zhu G. Y., Lou F. C. (2002a). Study on two new constituents of triterpenes from rhizoma alismatis II. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 14, 5–8. 10.1633/j.10001-6880.2002.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G. P., Zhu G. Y., Lou F. C. (2002b). Study on triterpenes in rhizoma alismatis from Sichuan III. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 14, 7–10. 10.16333/j.1001-6880.2002.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X. Y., Gu W., Zhou J. J., Wu Q. N., Xu F., Gao J. (2013). Gene cloning of squalene synthase in Alisma orientalis and its bioinformatic analysis. Chin. Trad. Herb. Drug. 44, 604–609. 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2013.05.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Z. H., Pu J., Chen L., Zhang Y. B., Rahman K., Qin L., et al. (2016). Alisma orientale: ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional chinese medicine. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2, 227–251. 10.1142/S0192415X16500142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Chen H., Zhao Y. Y. (2014). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and quality control of Alisma orientale (Sam.) juzep: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 158, 373–387. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur J. M., Korman T. P., Cao Z., Bowie J. U. (2014). Evidence of a novel mevalonate pathway in archaea. Biochemistry 25, 4161–4168. 10.1021/bi500566q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Huo X. K., Luan Z. L., Cao F., Tian X. G., Zhao X. Y., et al. (2017a). Alismanin A, a triterpenoid with a C34 skeleton from Alisma orientale as a natural agonist of human pregnane X receptor. Org. Lett. 19, 5645–5648. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhang J. X., Shen X. L., Wan C. K., Tse K. W., Fong W. F. (2004). Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by alisol B 23-acetate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 843–855. 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. X., Li H. Z., Wang X. N., Shen T., Wang S. Q., Ren D. M. (2018). Alisol B-23-acetate, a tetracyclic triterpenoid isolated from Alisma orientale, induces apoptosis in human lung cancer cells via the mitochondrial pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 1015–1021. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L., Zhao J. C., Liang J. H., Tian X. G., Huo X. K., Feng L., et al. (2017b). A bioactive new protostane-type triterpenoid from Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. orientale (sam.) juzep. Nat. Prod. Res. 11, 776–781. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1408106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X. L., Mai Z. P., Wang X. C., Liang D. S., Zhang B. (2016). Protostane alisol derivatives from the rhizome of Alisma orientale. Phytochem. Lett. 16, 8–11. 10.1016/j.phytol.2016.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin X. L., Zhao X. Y., Huo X. K., Tian X. G., Sun C. P., Zhang H. L., et al. (2018). Two new protostane-type triterpnoids from Alisma orientalis. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 189–194. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1344660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Zhang H. D., Xie X. (2012). New triterpenoids from rhizoma alisma. Chin. Trad. Herb. Drugs 43, 841–843. [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Lu Q. A., Gu W., Chen J., Fang F., Zhao B., et al. (2018). Studies on the lipid-regulating mechanism of alisol-based compounds on lipoprotein lipase. Bioorg. Chem. 80, 347–360. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Wu Q. N., Chen J., Gu W., Fang F., Zhang L. Q., et al. (2014). The binding mechanisms of plasma protein to active compounds in Alisma orientale rhizomes (Alismatis Rhizoma). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 4099–4105. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Yu H., Lu C., Chen J., Gu W. (2016). The cholesterol -lowering effect of alisol acetate based on HMG-CoA reductase and its molecular mechanism. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016:4753852 10.1155/2016/4753852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Li T., Qiu J. F., Wu S. S., Huang M. Q., Lin L. G., et al. (2015). Anti-proliferative activities of terpenoid isolated from Alisma orirntalis and their structure activity relationships. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 15, 228–235. 10.2174/1871520614666140601213514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. H., Zhao L. J., Li Y. (2009). Alisol B acetate induces apoptosis of SGC7901 cells via mitochondrial and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases/Akt signaling pathways. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 2870–2877. 10.3748/wjg.15.2870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Bai R., An Y., Liu T. T., Liang J. H., Tian X. G., et al. (2019). A natural inhibitor from Alisma orientale against human carboxylesterase 2: kinetics, circular dichroism spectroscopic analysis, and docking simulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 133, 184–189. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Hatakeyama S., Tanaka N., Fuhuda Y., Yamahara J., Murakami N. (1993). Crude drug from aquatic plants. I. on the constituents of Alismatis Rhizoma. (1). absolute stereostructures of Alisols E 23-acetate, F, and G, three new protostane-type triterpenes from Chinese Alismatis Rhizoma. Chem. pharm. Bull. 41, 1948–1954. 10.1248/cpb.41.1948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Muraakami T., Ikebata A., Ishikado A., Murakami N., Yamahara J., et al. (1997). Absolute stereostructures of Alismalactone 23-acetate and Alismaketone-A-23-acetate, new seco-protostane and protostane-type triterpenes with vasorelaxant effects from Chinese Alismatis Rhizoma. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 45, 756–758. 10.1248/cpb.45.756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Tomohro N., Murakami T., Ikebata A., Matsude H., Matsude H., et al. (1999). Studies on Alismatis Rhizoma. III. stereostructures of new protostane-type triterpenes,aliaols H, I, J-23-acetate, K-23-acetate, L-23-acetata, M-23-acetate, and N-23-acetate, from the dried rhizome of Alisma orientale. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 147, 524–528. 10.1248/cpb.47.524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Yamaguchi S., Chatani N., Matsuoka T., Yamahara J., Murakami N., et al. (1994). Crude drugs from aquaticplants. III. quantitative analysis of triterpene constituents in Alismatis rhizoma by means of high performance liquid chromatography on the chemical change of the constituents during Alismatis rhizoma processing. Yakuqaku Zasshi. 114, 241–247. 10.1248/yakushi1947.114.4_241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Tang W. J., Yin J. J., Feng L. J., Li Y. B., Yao X. R., et al. (2016). Alisol A 24-acetate prevents hepatic steatosis and metabolic disorders in HepG2 cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 40, 453–464. 10.1159/000452560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. L., Xu Y. L., Tang Z. H., Xu X. H., Chen X., Li T., et al. (2016). Effects of alisol B 23-acetate on ovarian cancer cells: G1 phase cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, migration and invasion inhibition. Phytomedicine 23, 800–809. 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Jiang Z. Y., Luo J., Cheng P., Ma Y. B., Zhang X. M., et al. (2008). Anti-HBV agents. part 1: synthesis of alisol A derivatives: a new class of hepatitis B virus inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 4647–4650. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Jiang Z. Y., Luo J., Liu J. F., Ma Y. B., Guo R. H., et al. (2009). Anti-HBV agents. part 2: synthesis and in vitro anti-hepatitis B virus activities of alisol A derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 2148–2153. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. J., Bai G., Chen C. Q., Xu J., Han Y. Q., Long S. X. (2018). Research pathways of Q-marker of compound Chinese medicine based on five principles. Chin. Trad. Herb. Drugs 49, 1–13. 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2018.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. J., Huo X. K., Tian X. G., Feng L., Ning J., Zhao X. Y., et al. (2017). Novel protostane-type triterpenoids with inhibitory human carboxylesterase 2 activities. Rsc. Adv. 7, 28702–28710. 10.1039/C7RA04841F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Godecke T., Gunn J., Duan J. A., Che C. T. (2013). Protostane ang fusidane triterpenes: a mini- review. Molecules 18, 4054–4080. 10.3390/molecules18044054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Xu L. J., Che C. T. (2007). Alisolide, alisols O and P from the Alisma orientale. Phytochemistry 69, 527–532. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. L., Huang X. Q., Li X. Y., Zhang F. F., Chen S. N., Ye M., et al. (2015). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of major teiterpenoids in Alismatis rhizome by high performance liquid chromatography/diode-array detector/quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry and ultra-performance liquid chromatography/triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Molecules 20, 13958–13981. 10.3390/molecules200813958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. F., Zhu Y. L., Peng G. P. (2006). Transformation of alisol B 23-acetate in processing drug of Alisma orientale. Chin. Trad. Herb. Drugs 37, 1479–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Tian R., Gu W., Geng C., Wu Q. N., Xu F. (2018). Prokaryotic expression, functional verification and immunoassay of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase of Alisma orientale (sam.) juzep. Acta Pharm. Sin. 53, 1571–1577. 10.16438/j.0513-4870.2018-0401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. L., Peng G. P. (2006). Progress in the study on chemical constituents of Alisma orientalis. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 18, 348–351. 10.16333/j.1001-6880.2006.02.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]