Abstract

The transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) governs anti-oxidant, innate immune and cytoprotective responses, and its deregulation is prominent in chronic inflammatory conditions. To examine the hypothesis that Nrf2 might be implicated in systemic sclerosis (SSc), we investigated its expression, activity and mechanism of action in SSc patient samples and mouse models of fibrosis, and evaluated the effects of a novel pharmacological Nrf2 agonist. We found that both expression and activity of Nrf2 were significantly reduced in SSc patient skin biopsies, and showed negative correlation with inflammatory gene expression. In skin fibroblasts, Nrf2 mitigated fibrotic responses by blocking canonical TGF-β-Smad signaling, while silencing Nrf2 resulted in constitutively elevated collagen synthesis, spontaneous myofibroblast differentiation and enhanced TGF-β responses. Bleomycin treatment of Nrf2-null mice resulted in exaggerated fibrosis. In wildtype mice, treatment with a novel pharmacological Nrf2 agonist 2-trifluoromethyl-2'-methoxychalone prevented dermal fibrosis induced by TGF-β. These findings are the first to identify Nrf2 as a cell-intrinsic anti- fibrotic factor with key roles in maintaining extracellular matrix homeostasis, and a pathogenic role in SSc. Pharmacological re-activation of Nrf2 therefore represents a novel therapeutic strategy toward effective treatment of fibrosis in SSc.

Keywords: fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, fibroblast, TGF-β, Smad, reactive oxidative species, oxidative stress, Nrf2

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is characterized by microvascular and immune dysregulation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which together drive perisstent multi-organ fibrosis[1]. The pathogenesis of SSc remains poorly understood, and consensus regarding optimal treatment remains elusive. Transcriptome analysis of SSc skin biopsies has identified distinct and stable intrinsic gene expression subsets with evidence of prominent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway activation [2]. By orchestrating fibrotic responses including myofibroblast differentiation, ROS generation, extracellular matrix synthesis and stiffening, TGF-β plays a central role in SSc pathogenesis [1].

In earlier studies aimed at identifying effective therapies to attenuate fibroblast activation, we showed that 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) mitigated TGF-β-induced fibrotic responses, normalized constitutive activation of SSc fibroblasts [3] and ameliorated experimental skin fibrosis in the mouse [4]. CDDO is a synthetic oleanane triterpenoid with favorable drug-like properties and a broad range of biological activities. The effects and mechanisms of action of CDDO appear to be context- and dose-dependent. In particular, the ubiquitously expressed and functionally pleiotropic leucine zipper transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) has been implicated as a mediator of certain CDDO responses [3]. In the absence of cellular stress, cellular Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytosol in a transcriptionally-inactive form due to its binding to the Keap1-Cul3-Rbx1 E3 ligase complex, which targets Nrf2 for rapid proteasomal degradation. Upon activation, Keap1 cysteine residues undergo oxidoreduction, liberating Nrf2, which then translocates into the nucleus where it binds to antioxidant responsive elements (ARE) controlling the transcription of genes encoding anti-oxidant and cytoprotective genes [5]. In addition, Keap1-independent mechanisms involving posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and interactions with cofactors are also emerging as important mechanisms for regulating Nrf2 activation [6]. Nrf2 controls cytoprotective, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory gene transcription [5]. The balance of Nrf2 activation is tightly regulated, and impaired Nrf2 function is linked to chronic metabolic, malignant, inflammatory, degenerative and fibrotic diseases [6–11].

Our studies identified a key role for Nrf2 in mediating the anti-fibrotic effects elicited by CDDO. These findings led us to explore the potential involvement of Nrf2 in fibrosis in SSc. We demonstrate that Nrf2 expression and activity are significantly reduced in SSc skin biopsies and explanted skin fibroblasts. Forced expression of Nrf2 in normal fibroblasts resulted in abrogated stimulation of collagen synthesis, myofibroblast differentiation and ROS generation through disruption of canonical TGF-β signaling. Mice lacking Nrf2 showed enhanced sensitivity to bleomycin-induced scleroderma in vivo, while wildtype mice treated with a novel pharmacological Nrf2 activator (2-trifluoromethyl-2'-methoxychalone, TMC), a heterocyclic chalcone derivative compound, showed attenuated skin fibrosis. Together, our results identify, for the first time, Nrf2 as cell-autonomous negative regulator of cutaneous fibrogenesis and demonstrate impaired Nrf2 expression and activity associated with fibrosis in SSc. Reduced Nrf2 is likely to contribute to disease persistence and progression, suggesting that pharmacological restoration of Nrf2 signaling might represent a novel approach to treating this intractable disease.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects and cell culture

Healthy adult volunteers and patients with SSc were recruited from the Northwestern Scleroderma Program. Skin biopsies were performed after informed consent and in compliance with Northwestern University Institutional Review Board for Human Studies. Primary cultures of fibroblasts were established by explantation, and propagated ex vivo as described [4]. At early confluence, fresh media containing indicated concentrations of CDDO (RAID, NCI, Rockville, MD) or human recombinant TGF-β2 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) were added to the cultures. Incubation were continued for up to 48 h. In selected experiments, cultures were preincubated with cycloheximide (25 µg/ml) or MG132 (10 µM), the Nrf2 activators tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) or sulforaphane (SFN) (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or a novel pharmacological Nrf2 agonist TMC (Cureveda LLC, Halethorpe, MD). Cytotoxicity was evaluated by LDH cytotoxicity assays (Biovision, Mountain View, CA) and by Trypan blue dye exclusion.

Bleomycin- and Ad-TGFβ1-induced skin fibrosis

Using experimental protocols institutionally approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Johns Hopkins University and Northwestern University, dermal fibrosis was induced by two distinct approaches: daily subcutaneous (s.c.0 injections of bleomycin, or single s.c. injection of adenovirus expressing constitutively-active TGF-β1 [4]. In the first approach, female 6–8 week-old Nrf2 knockout mice (Nrf2KO, C57BL/6 background) [12] and wildtype littermates were in parallel given bleomycin via daily s.c. injection (10 mg/kg in PBS) for 14 days and sacrificed on day 21. In an alternate approach, replication-deficient type 5 adenovirus encoding a constitutively active mutant form of TGF-6 β1 (Ad-TGF-β1, 1 × 109 pfu/mouse) was injected once s.c., and mice were sacrificed six weeks later [4]. TMC (400 mg/kg, dissolved in 10% ethanol, 35% sesame oil, and 55% Cremophor-EL (Sigma) or vehicle was given by oral gavage every other day from day 0 through day 41. Lesional skin was harvested and analyzed as previously described [4]. Briefly, consecutive 4-µm serial sections of paraffin-embedded skin tissue from mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Trichrome [13]. Dermal thickness, defined as the distance between the epidermal-dermal and dermal-subcutaneous adipose junctions, was determined at five random locations/slide for each mouse [14]. Collagen deposition in skin was determined by IHC using antibodies to Type III collagen [15]. To quantify myofibroblasts, skin sections were immunostained with anti-αSMA antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies (all Vector labs, Peterborough, UK). Spindle-shaped cells positive for αSMA in the dermis in six randomly chosen high-power fields were counted by two observers in a blinded manner [16]. Experimental groups consisted of 4–6 mice per group.

Transient transfection assays

The Nrf2-dependent ARE-Luc [17], and Nrf2 constructs used for transient transfection assays, were from Dr. Mark Hannink (University of Missouri) [18]. The [SBE]4-TK-Luc reporter contains 4 copies of the consensus Smad-binding element linked to the minimal thymidine kinase promoter and luciferase genes [19]. RNAi was used to knock down cellular Nrf2 or Keap1. Transient transfection assays were performed as described [4]. Confluent foreskin fibroblasts were cotransfected with reporter and expression vectors or empty vectors using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen), and incubated with TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for up to 48 h. Whole cell lysates were prepared and analyzed using Dual-Luciferase Reporter assays (Promega, Madison, WI). pRLTK-luc was used in each experiment as an internal control. For RNAi-mediated gene silencing, fibroblasts were transfected with target-specific short interfering RNA (siRNA) (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) or scrambled control siRNA (10 nM unless otherwise indicated). Twenty-four hours following transfection, fresh media containing TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) or CDDO (2.5 µM) were added to the cultures, and incubation was continued for a further 24 h.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from confluent fibroblasts using Quick RNATM Miniprep (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) as described [4]. Reverse transcription for qPCR was performed using qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and real-time qPCR was performed on an ABI-Prism 7300 (Applied Biosystem, Forster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [4]. Relative mRNA expression levels, normalized to Gapdh expression in each sample, were determined by calculating ΔΔCt (Applied Biosystem).

Immunoprecipitation and Western analysis

Fibroblast cultures were harvested at the end of the incubation, and equal amounts of whole cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis, or were first immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies followed by Western analysis [4]. After electrophoresis proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, blocked with 10% fat-free milk in TBST buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20), and incubated with the following primary antibodies: Nrf2, Keap1, Smad1/2/3 (each at 1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), p300, histone H4 (1:1000, Millipore), GAPDH (1:3000, Invitrogen), α-SMA (1:2000; Sigma) or Type I collagen (1:400; Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Antigen–antibody complexes were visualized by chemiluminescence (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), and band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded skin biopsies from SSc patients and healthy controls using primary antibodies that bind to human Nrf2 (Santa Cruz) at 1:100 dilution [11]. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin, and substitution of the primary antibody with isotype-matched irrelevant IgG served as negative controls. Slides were scanned with the TissueFAXSi-plus imaging system (TissueGnostics, Austria). A series of separate images per field of view (FOV) were taken automatically, collected and merged afterwards to a virtual sample in TissueFAXSi-plus (TissueGnostics). Images were analyzed with TissueQuest software (TissueGnostics). Using the software, hematoxylin for nuclei and Nrf2 stain were applied as markers. To achieve optimal cell detection, the following parameters were adjusted: nuclei size and discrimination by area. To evaluate positive cells, scattergrams were created, allowing the visualization of corresponding positive cells in the source region of interest using the real-time back gating feature [20]. The cut-off discriminates between false events and specific signals according to cell size and intensity of staining. The number of Nrf2-positive cells in the dermis was determined from 3 randomly selected hpf (0.2 µm2/each). For immunofluorescence, tissues were incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), followed by DAPI staining [21]. Images were obtained using a Nikon-A1 Confocal microscope. The proportion of dermal cells with double staining (protein of interest plus marker protein) was determined by calculating the ratio of double-positive cells to single-positive cells from at least three representative images.

For mouse studies, lesional skin was harvested at the end of the experiment, and examined by histochemistry or immunofluorescence. Nonspecific goat IgG served as a negative antibody control. Following stringent washing, slides were examined under an Axioskope microscope or Zeiss UV Meta 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The numbers of α-SMA positive fibroblast-like interstitial cells in the dermis were determined from 5 randomly selected hpf in each biopsy by two observers blinded to the experimental conditions.

Determination of cellular ROS

To examine the contribution of endogenous ROS to the antifibrotic effects of Nrf2 activators, fibroblasts were pre-incubated in media with D(+)-galactose (5 µM) in the presence of galactose oxidase (Sigma) prior to addition of CDDO. Confluent fibroblasts incubated in media with D(+)-galactose and galactose oxidase were washed with PBS, and incubated with 2 µM H2-DCFDA (Invitrogen) for 15 min. Fibroblasts were then washed and resuspended in PBS for analysis in a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with excitation and emission wave lengths of 475 and 525 nm, respectively. For each analysis 50,000 events were recorded.

Analysis of gene expression and measurement of pathway activation

Gene expression changes induced by CDDO in fibroblasts were examined genome-wide (GEO accession number GSE47616). Genes showing >2 fold up-regulation in CDDO-treated compared to control fibroblasts (p<0.05, FDR<0.05) were selected for further analysis.

To interrogate the expression of Nrf2 target genes and assess Nrf2 pathway activation, we selected the top 30 Nrf2-upregulated and top 30 Nrf2-downregulated genes from a dataset generated by transfection with siNrf2 or siKeap1 in lung fibroblasts [22]. This gene list was extracted from a combined SSc skin biopsy microarray dataset (GSE9285 and GSE45485) [2]. Nrf2 pathway scores were calculated based on previously published approaches [23]. The mean and SD levels for of each Nrf2-regulated gene in the healthy (ctr) group (meanctr and SDctr) were used to standardize expression levels of each gene for each biopsy. The standardized expression levels were subsequently summed for each biopsy to provide an Nrf2 signature score: , where i = each of the Nrf2-regulated genes, Gene iSSc = the gene expression level in each SSc patient, and Mean ictr = the average gene expression in controls. For Nrf2 induced genes, k=1; for Nrf2 suppressed genes, k=−1.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD of multiple determinations. GraphPad Prism Software V.6.0 was used for statistical analyses. Differences between the groups were tested for their statistical significance by paired student t tests for related samples and Mann-Whitney U non-parametrical test for non-related samples. p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

CDDO induces expression and function of Nrf2 by preventing its degradation

We showed previously that the synthetic oleanane triterpenoid CDDO abrogated TGF-β-dependent fibrotic responses in mesenchymal cells in vitro, and mitigated fibrosis in mouse models [4]. Intriguingly, while CDDO is a known agonist for the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ, we found that its anti-fibrotic effects were largely independent of PPAR-γ [4]. In order to characterize the mechanisms and mediators underlying CDDO’s potent anti-fibrotic effects, we examined genome-wide changes induced by CDDO treatment in fibroblasts. By microarray transcriptome analysis, we found that 10 of the 20 genes most highly up-regulated by CDDO treatment for 24 h in normal human fibroblasts were recognized Nrf2 targets (Table 1) [24]. These findings suggested that Nrf2 mediated the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO in fibroblasts, and therefore we focused our studies on Nrf2.

Table 1.

Top 20 genes most up-regulated by CDDO treatment in fibroblasts

| Symbol | Description | -fold change |

|---|---|---|

| HMOX1* | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 9.9913 |

| OSGIN1* | oxidative stress induced growth inhibitor 1 | 8.3737 |

| SRXN1* | sulfiredoxin 1 | 5.7883 |

| PGD* | phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 5.1085 |

| ABCC3 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 3 | 4.94 |

| GCLM* | glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit | 4.3192 |

| NQO1* | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinine 1 | 4.0421 |

| PIR | pirin (iron-binding nuclear protein) | 4.0085 |

| ABCB6 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 6 | 3.4155 |

| G6PD* | glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | 3.4114 |

| TXNRD1* | thioredoxin reductase 1 | 3.3575 |

| HBA2 | hemoglobin, alpha 2 | 3.1227 |

| LOC344887 | NmrA-like family domain containing 1 pseudogene | 3.0058 |

| FTH1* | ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 | 2.7833 |

| CREG1 | cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes 1 | 2.7827 |

| KLF2 | Kruppel-like factor 2 (lung) | 2.7499 |

| TXNRD1* | thioredoxin reductase 1 | 2.7241 |

| SLC2A1 | solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 1 | 2.6658 |

| ATP6V0A1 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit a1 | 2.6059 |

| SLC48A1 | solute carrier family 48 (heme transporter), member 1 | 2.5192 |

Confluent normal skin fibroblasts were incubated in media with CDDO (2.5 uM) or DMSO for 24 h. RNA was isolated and subjected to Illumina microarray analysis as described in Material and Methods (GEO accession number GSE47616).

known Nrf2 target genes.

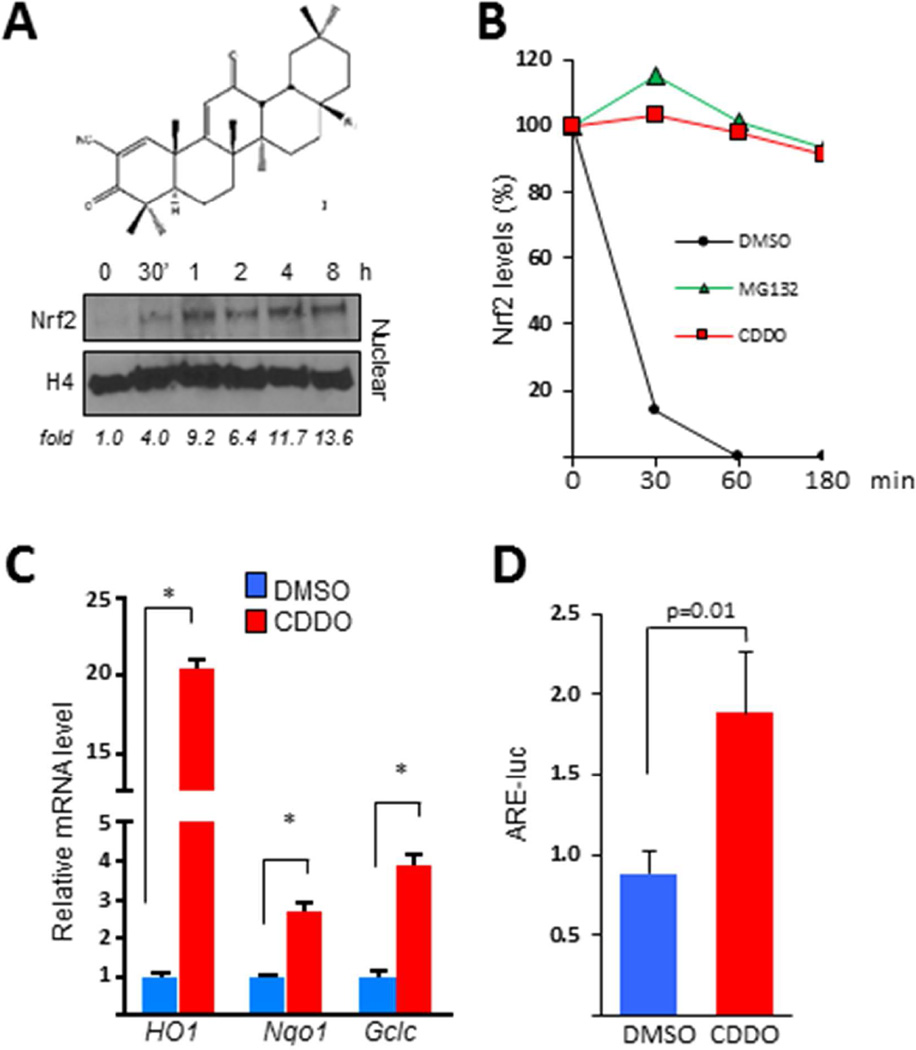

Normal skin fibroblasts showed markedly increased nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 within 30 min of CDDO exposure, whereas levels of Nrf2 mRNA were not altered (Fig. 1A and data not shown). While blocking de novo protein synthesis in untreated fibroblasts resulted in rapid decline of Nrf2, in the presence of CDDO, cellular Nrf2 levels remained stable for > 180 min (Fig. 1B). Incubation of the cultures with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 similarly stabilized cellular Nrf2, indicating that accumulation of Nrf2 in CDDO-treated fibroblasts is likely to be due to disrupting of its proteasome-mediated degradation. Additional functional studies showed that CDDO elicited a dose-dependent up-regulation of multiple Nrf2 target genes, and induced significant (p<0.05) stimulation of Nrf2-dependent transcriptional activity (Figs. 1 C, D; data not shown).

Figure 1. Synthetic oleanolic acid derivative CDDO blocks fibrotic responses and enhances Nrf2 expression and activity in normal fibroblasts.

Confluent foreskin fibroblasts were incubated in media with CDDO (2.5 µM) or proteasome inhibitor MG132 for up to 24 h or as indicated. A. Upper panel, structure of CDDO. Lower panel, Western analysis of nuclear protein. Representative images from an experiment representative of three. Band intensities for Nrf2 normalized to nuclear H4 are shown below. B. Fibroblasts were preincubated with cycloheximide for 30 min. Western analysis of whole cell lysates. C. Real-time qPCR. Results, normalized to GAPDH, are means ± SD of triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. *p <0.05. D. Fibroblasts were transiently transfected with ARE-luc, and following 24 h incubation cell lysates were assayed for their luciferase activity. Results, normalized with renilla luciferase, are shown as means ± SD of triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. * P <0.05. HO1, heme oxygenase 1. Nqo1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1. Gclc, glutamate-cysteine ligase, catalytic subunit. ARE-luc, antioxidant response element reporter.

Nrf2 expression and activity are down-regulated in SSc skin biopsies

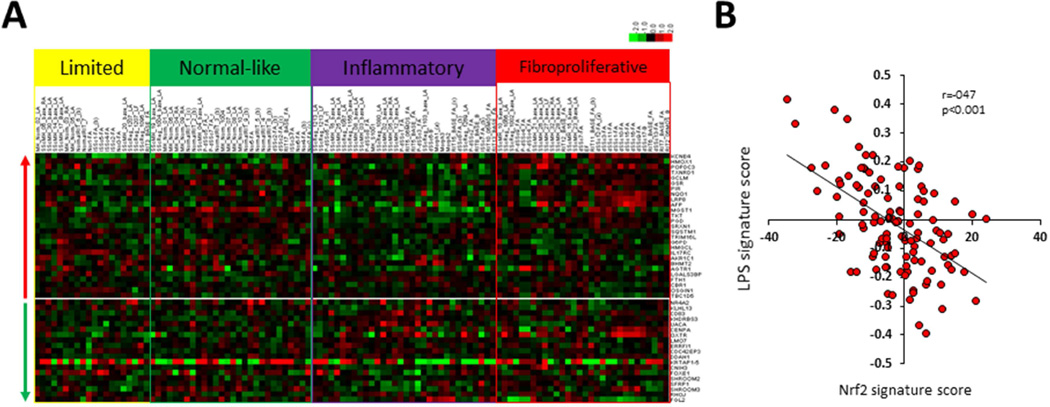

Having shown that the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO in fibroblasts were accompanied by Nrf2 up-regulation, suggesting an important role for this transcription factor in fibrosis, it was of interest to evaluate Nrf2 activity and expression in SSc. For this purpose, we took advantage of a well-characterized publicly available skin biopsy transcriptome microarray dataset [2]. Initially, a list comprising the 30 genes that were most up- or and most down-regulated by Nrf2 in human lung fibroblasts transiently transfected with siRNA targeting Nrf2 or Keap1 was assembled [22]. Next, to generate a Nrf2 pathway score, the expression of these Nrf2-regulated genes, designated the “fibroblast Nrf2 signature”, was measured for each biopsy grouped into intrinsic gene subsets (Fig. 2A). While we did not find correlation of the Nrf2 signature score with either the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS), or with disease duration, we demonstrated a strong negative correlation of the Nrf2 signature with the “LPS score”, which reflects the strength of local Toll-like receptor (TLR4) signaling activity (2), within the same skin biopsies (Spearman r=−0.47, p<5E-7) (Fig. 2B). Consistent with these finding, we found that the Nrf2 signature scores were significantly, albeit modestly, reduced in SSc skin biopsies mapping to the inflammatory intrinsic gene subset (p<0.005 compared to healthy controls) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. Reduced Nrf2-regulated gene signature in SSc skin biopsies.

The 30 genes most up- and down-regulated in lung fibroblasts with siNrf2 and siKeap1 knockdown were designated as the “Nrf2 signature” [22]. Expression of these genes was interrogated in SSc transcriptomes (NCBI GEO GSE9285 and GSE32413) [2]. A. Supervised hierarchical clustering of skin biopsy transcriptomes [2] without application of filtering criteria. 26 genes up-regulated (upper panel) and 19 genes down-regulated (lower panel) by Nrf2 present in this dataset. Biopsies from patients in the normal-like subset show gene expression most similar to healthy control skin biopsies. B. The Nrf2 signature score shows inverse correlation with the LPS signature score. P<0.001.

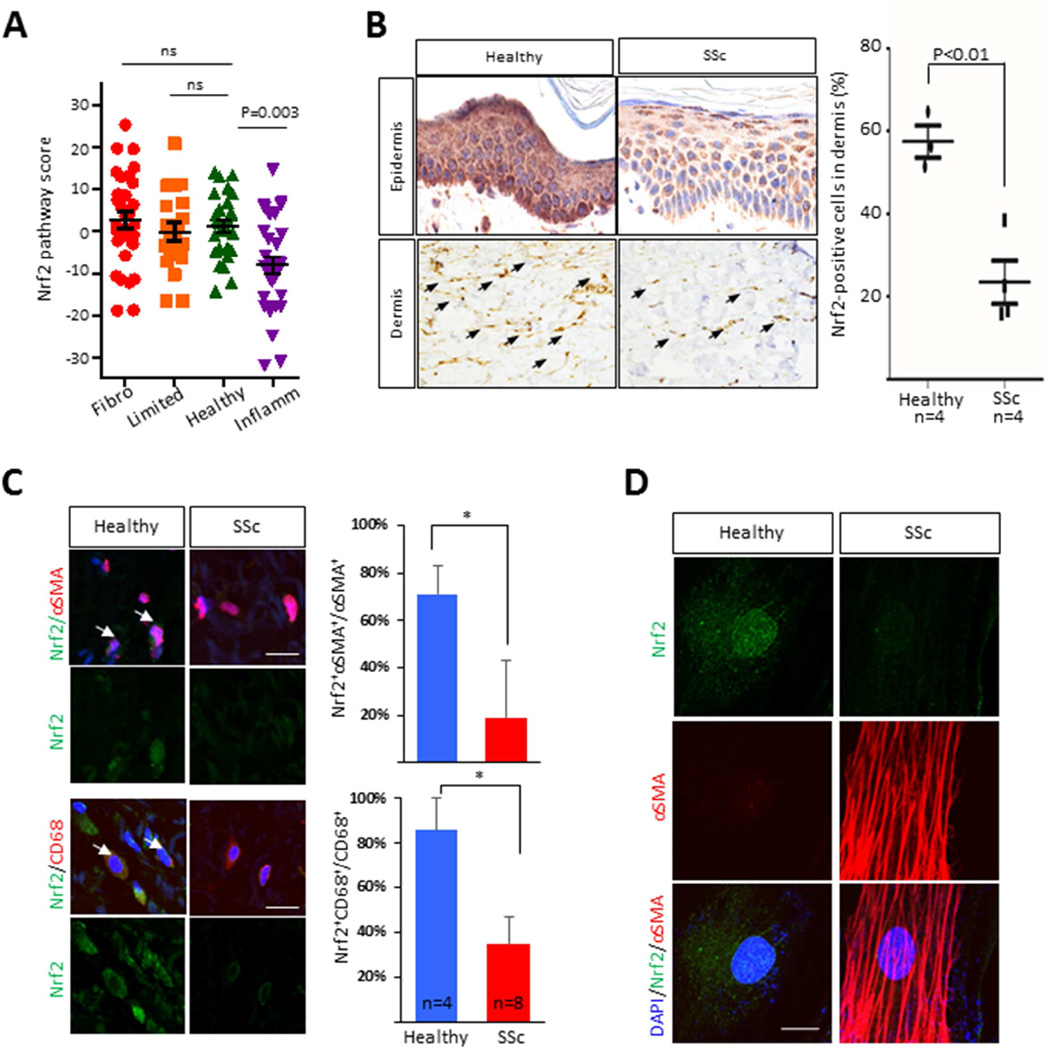

Figure 3. Nrf2 expression and activity is reduced in SSc.

A. Nrf2 pathway scores (defined as described under Material and Methods) queried from a skin biopsy-derived microarray transcriptome dataset [2]. Each symbol represents an individual biopsy. Fibro, fibroproliferative gene subset; Inflamm., inflammatory; Limited, limited. B. Immunohistochemistry of skin biopsies from SSc patients (n=4) and healthy controls (n=3) immunostained with antibodies to Nrf2. Left panels, representative images (magnification 400 ×). Arrows indicate intradermal Nrf2-immunopositive cells. Right panel, quantitation. Results are the mean ± SD in 3 hpf randomly selected from each biopsy. C. Immunofluorescence. Healthy control (n=4) and SSc (n=8) skin biopsies were immunostained with antibodies to αSMA (red), Nrf2 (green) or CD68 (red); nuclei were identified using DAPI (blue). Left panel, representative images; arrowheads indicate double-immunopositive cells. Bar=20 µm. Right panels show the proportion of double-positive cells. Results are mean ± SEM; *p<0.05. D. Double-label immunofluorescence with antibodies to Nrf2 and α-SMA in control (n=3) and SSc (n=3) skin fibroblasts (magnification ×600). Representative images. Green color, Nrf2; Red color, αSMA; blue color, DAPI. Bar=10 µm. α-SMA, alpha smooth muscle actin.

Next, we sought to evaluate levels of Nrf2 protein in SSc skin biopsies. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Robust immunostaining for Nrf2 was seen in the normal epidermis, which appeared to be markedly attenuated in some SSc biopsies (Fig. 3B). Importantly, we also found that the numbers of Nrf2-immunopositive interstitial fibroblastic cells within the dermis were significantly lower in SSc compared to healthy skin biopsies (p<0.05). Dual-color immunofluorescence indicated that while αSMA-positive interstitial fibroblasts within the dermis were only infrequently observed in healthy control biopsies, ~70% of these cells were positive for Nrf2; in contrast, while the numbers of of αSMA+ fibroblasts was increased in the fibrotic dermis in SSc skin biopsies from an independent cohort of eight SSc patients, only approximately 20% of them were also Nrf2+ (p<0.05) (Fig. 3C). Expression of Nrf2 was also significantly reduced in CD68+ cells in the fibrotic dermis. Reduced Nrf2 protein levels in SSc, in thr absence of comparable reduction of Nrf2 mRNA levels, most likely reflects post-translational modification of Nrf2 such as Keap1-mediated proteasomal degradation [5]. Skin fibroblasts explanted from patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc (n=3) showed significantly reduced nuclear Nrf2 compared to age- and sex-matched healthy control fibroblasts (n=3), with lowest levels detected in fibroblasts with elevated αSMA expression (Fig. 3D). Together, these results demonstrated a consistent and significant down-regulation of Nrf2 protein expression in interstitial dermal cells from SSc skin biopsies.

Table 2.

Clinical features of SSc subjects included in analysis of Nrf2 expression (Fig 3B, C)

| Age (yrs) |

gender | MRSS (0–51) |

Skin score* at biopsy site |

Disease duration at time of biopsy (months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSc 1 | 49 | F | 3 | 0 | 44 |

| SSc 2 | 51 | M | 48 | 3 | 9 |

| SSc 3 | 50 | F | 24 | 2 | 101 |

| SSc 4 | 34 | F | 32 | 2 | 40 |

| SSc 5 | 57 | F | 11 | 1 | 64 |

| SSc 6 | 50 | F | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| SSc 7 | 58 | F | 3 | 0 | 45 |

| SSc 8 | 55 | F | 7 | 0 | 116 |

| SSc 9 | 70 | F | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| SSc10 | 57 | F | 9 | 0 | 47 |

| SSc 11 | 43 | F | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| SSc 12 | 53 | F | 19 | 1 | 12 |

All biopsies were from forearm. MRSS, modified Rodnan Skin score.

Skin score at biopsy site: 0, normal thickness; 1, mild thickening; 2, moderate thickening; 3, severe thickening.

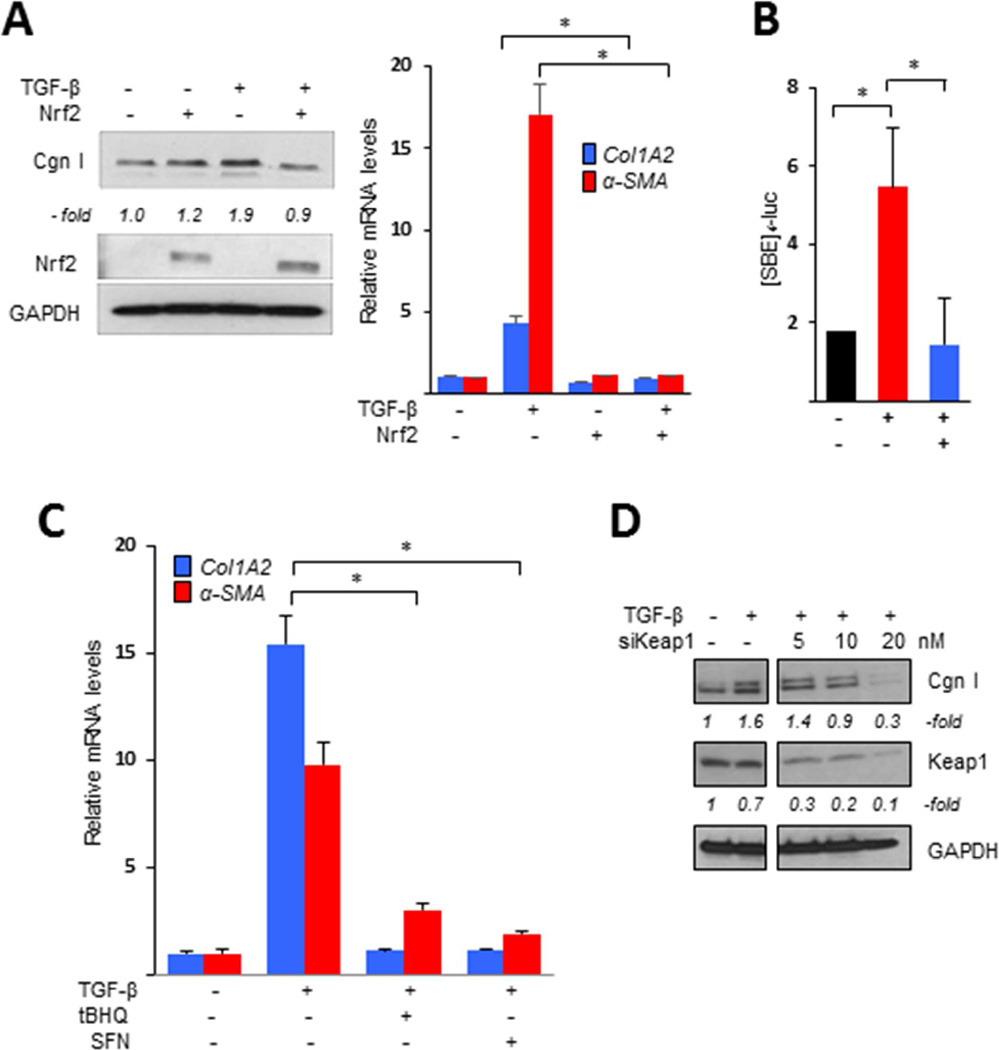

Nrf2 attenuates TGF-β-induced fibrotic responses and mediates the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO

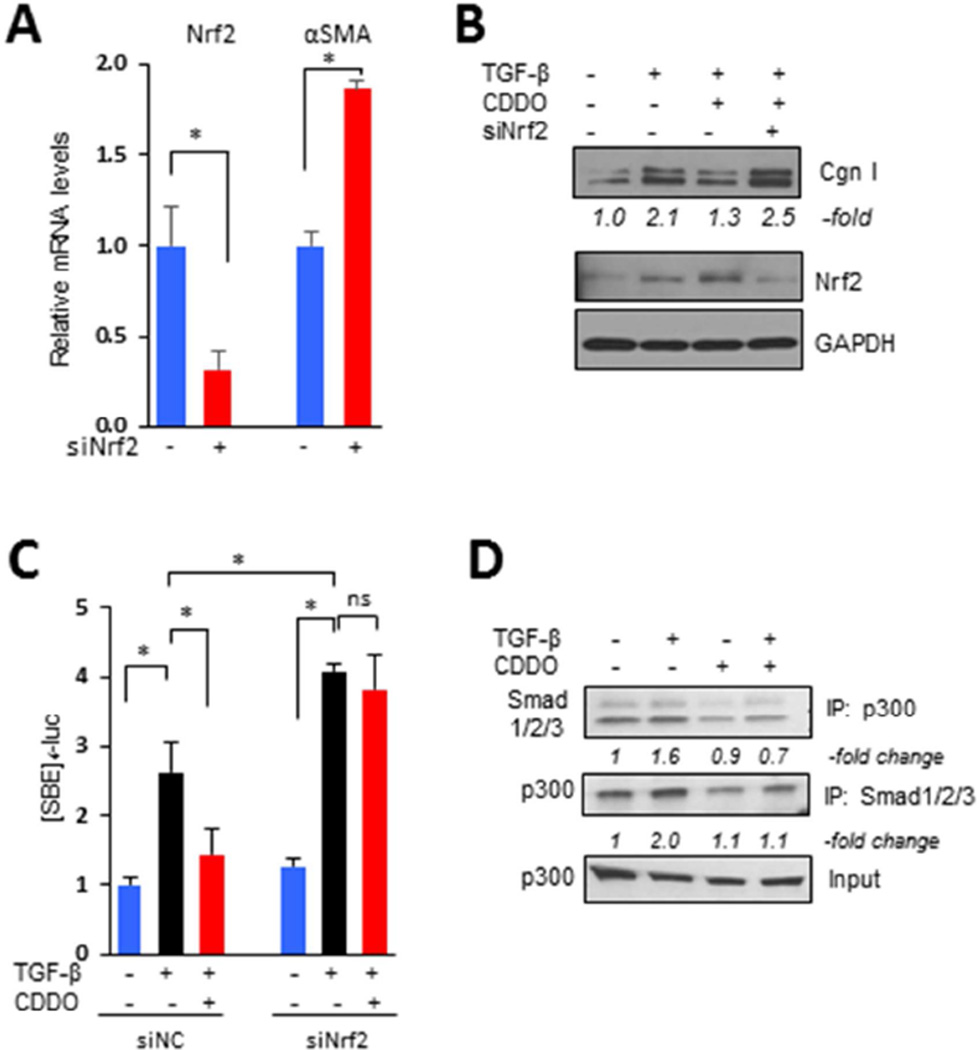

To explore the potential of Nrf2 for modulating fibrotic responses, we first examined the modulation of TGF-β effects in fibroblasts transfected with Nrf2. As shown in Fig 4A, the stimulatory effects of TGF-β were significantly attenuated by Nrf2 overexpression. Additional transient transfection assays showed that stimulation of [SBE]4-luc activity was completely abrogated by Nrf2 (Fig. 4B). Incubation with selective chemical Nrf2 activators mimicked the anti-fibrotic effects of forced Nrf2 expression (Fig. 4C). Moreover, knockdown of cellular Keap1, which is normally responsible for Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation [25], resulted in dose-dependent reduction of profibrotic TGF-β responses, reproducing the effects of forced Nrf2 expression (Fig. 4D). In these experiments, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Keap1 was associated with elevated levels, and enhanced nuclear accumulation, of endogenous Nrf2, accompanied by increased expression of Nrf2 target genes (Suppl. Fig. 1). On the other hand, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Nrf2 resulted in spontaneously elevated αSMA expression even in the absence of TGF-β (Fig. 5A). Significantly, in fibroblasts with Nrf2 knockdown, CDDO failed to prevent stimulation of collagen synthesis or [SBE]4-luc activity (Figs. 5B and C), further supporting an essential role of Nrf2 in mediating the effects of CDDO. We have shown previously that CDDO had no effects on either inducible Smad2/3 phosphorylation or nuclear accumulation in normal fibroblasts [4]. The acetyltransferase p300 plays a fundamental role in Smad-dependent fibrotic responses and its up-regulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of SSc [26]. Co-immunoprecipitation assays showed that whereas TGF-β treatment strongly enhanced p300 interaction with Smad2/3 in normal fibroblasts, as expected, preincubation with CDDO almost completely blocked this response (Fig. 5D). We conclude therefore that Nrf2 mediates the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO, and plays a critical cell-autonomous homeostatic role by negatively regulating p300-Smad interactions and Smad-dependent transcription.

Figure 4. Nrf2 abrogates TGF-β-mediated fibrotic responses.

A, B. Confluent foreskin fibroblasts were transiently transfected with Nrf2, followed by incubation with TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. A. Left panels, Western analysis. Representative images. Band intensities for type I collagen normalized to GAPDH are shown below. Right panel, real-time qPCR. Results, normalized with GAPDH, are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. * p <0.05. B. Fibroblasts were co-transfected with [SBE]4-luc along with Nrf2. Results of transient transfection assays, normalized with renilla luciferase activities, are mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. * P <0.05. C. Fibroblasts were preincubated with tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ, 100 mM) or sulforaphane (SFN, 10 µM) for 30 min followed by TGF-β for 24 h. Results of real-time qPCR, normalized with GAPDH, are mean ± SD of triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. * P <0.05. D. Fibroblasts were transfected with Keap1 siRNA or control siRNA, followed by incubation with TGF-β for 24 h. Whole cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis. Representative images. Band intensities for type I collagen and Keap1 normalized to GAPDH are shown below. Cgn I, type I collagen.

Figure 5. Nrf2 mediates inhibition of canonical TGF-β signaling by TGF-β.

A–C. Confluent foreskin fibroblasts transiently transfected with Nrf2 siRNA or scrambled control were pre-incubated with CDDO (2.5 µM) followed by TGF-β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h (A, B) or 60 min (C). A. Real-time qPCR. Results, normalized with GAPDH and relative to control siRNA, are the mean ± SD from triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. B. Whole cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis. Representative images. Band intensities for type I collagen normalized to GAPDH are shown below. C. Fibroblasts were co-transfected with [SBE]4-luciferase. Results, normalized with renilla luciferase activities, are the means ± SD of triplicate experiment. *P <0.05. D. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Smad1/2/3 or p300, followed by immunoblotting. Representative images. Cgn I, type I collagen.

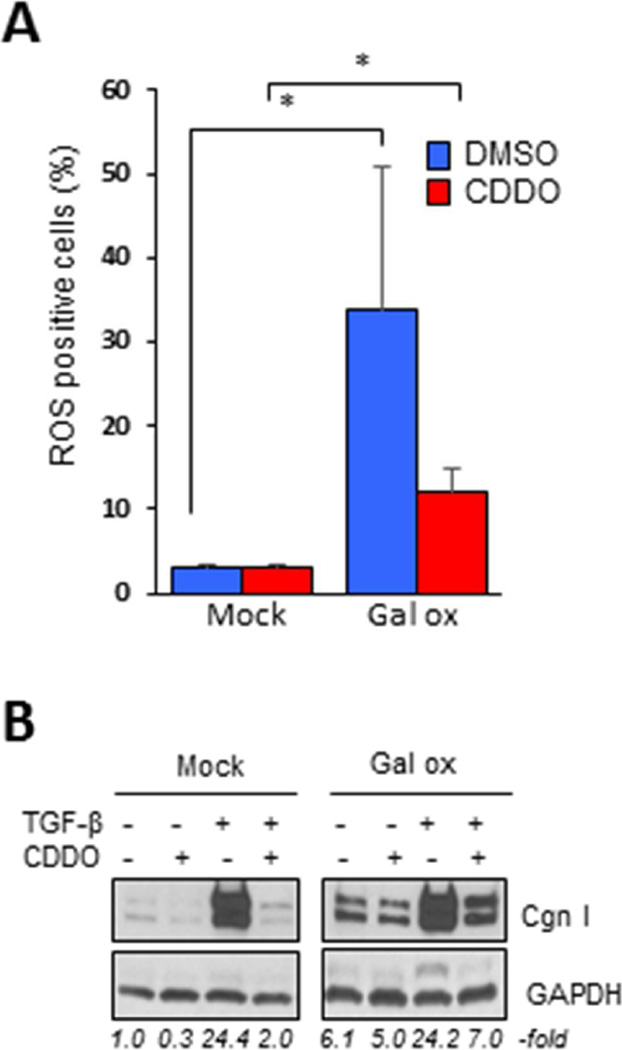

Oxidative stress, which reflects the imbalance between ROS generation and its removal via innate antioxidant defenses, is a pathogenic hallmark of SSc, and is a potent stimulus promoting fibrogenesis [27, 28]. We asked whether it is the anti-oxidant effects of CDDO that are responsible for its anti-fibrotic activity. To address this question, fibroblasts were incubated with D(+)-galactose plus galactose oxidase, which results in generation of hydrogen peroxide and its diffusion into the cells [29]. A substantial increase in intracellular ROS levels induced by galactose oxidase was observed, which was only partially abrogated when CDDO was added to the media (Fig. 6). Significantly, CDDO was found to abrogate collagen stimulation even in the face of ROS concentrations sufficient to stimulate fibrotic responses, indicating that the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO are not dependent on its ability to attenuate cellular oxidative stress.

Figure 6. CDDO treatment prevents profibrotic responses independent of its effects on ROS.

Confluent foreskin fibroblasts exposed to oxidative stress were incubated with CDDO (2.5 µM) alone or with TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. A. ROS-positive cells were quantitated by flow cytometry. Results are the means ± SD from three experiments. * P <0.05. B. Western analysis. Representative images. Relative band intensities shown below. Gal ox, galactose oxidase.

Nrf2KO mice show increased susceptibility to bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking Nrf2 showed constitutively elevated type I collagen gene expression, and Smad-dependent transcriptional activities, even in the absence of TGF-β (Figs. 7A and B). To assess the role of Nrf2 in modulating fibrogenesis in vivo, bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis was examined in Nrf2−/− mice. The Nrf2KO mice are viable, fertile and show no obvious phenotype [30]. We found that bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis, including increased thickness of the dermis, attrition of dermal white adipose tissue [31], increase in collagen deposition, and enhanced myofibroblast accumulation, were all significantly accentuated in Nrf2KO mice (Figs. 7C–E).

Figure 7. Bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis is exaggerated in Nrf2-null mice.

A, B. MEFs were transiently transfected with [SBE]4-luc and incubated with TGF-β for 24 h. Results of real-time qPCR, normalized with GAPDH, are the means ± SD from triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. B. Luciferase assays. Results, normalized with renilla luciferase activities, are the means ± SD of triplicate experiments. C–E. Nrf2−/− mice and wildtype littermates in parallel were administrated bleomycin (BLM) or PBS via daily s.c. injections for 14 days, sacrificed on day 21, and lesional skin was harvested. C. Left panels, H&E images. Double arrows indicate dermis. Right panel, dermal thickness. Each symbol represents the mean of 5 determinations/hpf from a single mouse (4–6 mice/group). Bar=50 µm. *P < 0.05. D. Immunofluorescence with antibodies to type III collagen (red color). Left panel, representative images. Right panel, relative fluorescence intensity. Results are mean ± SD of determinations from 3 hpf from 4–6 mice/group. Bar=50 µm. *P <0.05. E. Immunohistochemistry with antibodies to α-SMA. Left panels, representative images. Right panel, immunopositive interstitial cells within the lesional dermis were quantitated. The results are means ± SD of 5 determinations/hpf from 4–6 mice/group. Bar=25 µm. *P <0.05. Cgn III, type III collagen.

A novel pharmacological Nrf2 activator abrogates TGF-β induced fibrosis

The heterocyclic chlalcone TMC, a novel orally active synthetic compound, has been shown to have potent stimulatory effect on Nrf2 activity [32]. Treatment with TMC stimulated the expression of Nrf2 target genes in both neonatal and adult skin fibroblasts that was accompanied by attenuated fibrotic responses, indicating an antagonistic effect on TGF-β signaling (Fig. 8). Comparable suppression of fibrotic gene expression was seen in all explanted SSc skin fibroblast llines (n=4) treated with TMC (Table 3). We therefore next sought to evaluate the effects of TMC treatment in vivo in a TGF-β-dependent mouse skin fibrosis model. To this end, C57BL/6J mice were given a single subcutaneous injection of Ad-TGFβ1 or Ad-LacZ contemporaneously with starting oral gavage feeding of TMC or vehicle. Alternate-day gavage feedings were continued thereafter for six weeks. Oral TMC was generally well-tolerated with no signs of toxicity. Local delivery of constitutively active TGF-β1 resulted in significant skin fibrosis, while concurrent TMC treatment of the mice almost completely abrogated the cutaneous fibrotic changes (Figs. 8 C–E).

Figure 8. A novel Nrf2 activator abrogates TGF-β-induced fibrotic responses in vitro and in vivo.

A, B. Confluent foreskin fibroblasts were incubated with TMC (5 µM or indicated concentrations) with or without TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Results of real-time qPCR, normalized with GAPDH, are means ± SD from triplicate determinations from an experiment representative of three. * P < 0.05. A. Upper panel, structure of TMC. C–E. Mice received s.c. injection of Ad-TGFβ1 or Ad-lacZ, and treated with oral TMC (400 mg/kg) or vehicle every other day for six weeks. Lesional skin was harvested for analysis. C. H&E stain (original magnification ×200). Arrows delineate dermis; representative images. D. Dermal thickness. Each symbol represents the means of 5 determinations/hpf from 4–6 mice/group. *P <0.05. E. Real-time qPCR. The results, normalized with 36b4 or gapdh, represent the means ± SD of triplicate determinations from 4–6 mice/group. *p<0.05. HO1, heme oxygenase 1.

Table 3.

A novel Nrf2 activator attenuates fibrotic gene expression in SSc fibroblasts

| Cell line | COL1A1* | aSMA* | FnEDA* |

| S1 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| S2 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| S3 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.28 |

| S4 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

Confluent cultures of low-passage SSc skin fibroblasts (n=4) were incubated with TMC (5 µM) for 24 h. Results of real-time qPCR, normalized with GAPDH, are means from triplicate determinations.

fold change in mRNA levels compared to untreated cultures.

DISCUSSION

In light of their anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective activities, the synthetic triterpenoid CDDO and its derivatives are gaining increasing translational relevance, and are currently undergoing clinical evaluation [33]. However, the mechanism underlying their disease-specific pleiotropic beneficial effects are largely unknown. The present results identify Nrf2 as an indispensable cellular effector for the anti-fibrotic effects of CDDO. Moreover, the results show, for first time, that Nrf2 expression and activity is decreased in SSc skin biopsies. Forced expression of Nrf2 in normal fibroblasts abrogated canonical TGF-β signaling and Smad-dependent fibrotic responses, and loss of Nrf2 exacerbated skin fibrosis in a bleomycin-induced mouse scleroderma, while a novel pharmacological Nrf2 agonist compound attenuated skin fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. These observations together implicate Nrf2 impairment in the pathogenesis of SSc, and suggest that Nrf2 reactivation might represent a novel therapeutic strategy.

In light of its pleiotropic activities, Nrf2 has a central role in cellular adaptation to stress [5]. Normally maintained at low levels due to its continuous proteasomal degradation [34, 35], Nrf2 protects cells from toxic insults [36, 37]. Altered expression of Nrf2 is implicated in asthma, COPD and lung cancer in humans, as well as in mouse disease models [8, 38–40]. Aged mice show loss of cellular redox capacity similar to that observed in Nrf2 knockout mice [41]. Lungs from aged mice, as well as from IPF patients, showed an imbalance between ROS-generating Nox4 and Nrf2, resulting in disrupted cellular redox homeostasis that contributes to impaired fibrosis resolution [42]. Similar to the findings seen in aging lungs, in the present studies we found that Nrf2 expression and activity is also impaired in skin from patients with SSc. Although the mechanisms for the diminished Nrf2 activity are currently unclear, elevated autophagy and impaired SIRT1 signaling might play a role. There is increasing evidence that autophagy is critical in the pathogenesis of SSc [43]. High autophagic activity detected in fibrogenic cells is associated with reduced Nrf2 activation [44, 45]. We and others have shown previously the type III deacetylase sirtuin SIRT1, a positive regulator of Nrf2 activity [46], is significantly reduced in skin biopsies from SSc patients [21, 47]. A more in-depth understanding of the potential role of altered autophagy and SIRT1 activity in altered Nrf2 activation in SSc is required.

Tissue-specific Nrf2 deficiency has been linked with exaggerated and prolonged inflammatory and fibrotic responses [48–50]. Nrf2-null mice develop age-dependent autoimmunity and inflammatory lesions in multiple tissues [51, 52]. Immunohistochemical evaluation of SSc skin biopsies demonstrated a reduction in epidermal Nrf2 protein levels, and consistent reduction in Nrf2+ dermal interstitial cells, predominantly myofibroblasts. The marked reduction in Nrf2 protein levels in the face of relatively modest reduction in Nrf2 mRNA might indicate that Nrf2 protein levels are regulated primarily through post-translational modification including degradation, rather than at the transcription level [34,35]. The causes, and pathogenic roles, of altered Nrf2 degradation in SSc merit further investigation. Nrf2 has potent negative regulatory effects on both MyD88-dependent and -independent TLR signaling, and Nrf2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts show unrestrained NF-κB and IRF3 activation when challenged with LPS [12]. Our transcriptome analysis revealed significantly reduced Nrf2 pathway activity in SSc skin biopsies mapping to the inflammatory intrinsic gene subset characterized by up-regulated inflammatory genes linked to NF-κB activation [2]. Since the biological impact of Nrf2 is determined primarily by its transcriptional activities and intracellular localization, the reduction in Nrf2 signature score in SSc skin biopsies is likely to have a greater pathogenic impact than the modest reduction in Nrf2 protein levels. Importantly, we demonstrated that Nrf2 pathway score showed significant negative correlation with LPS signaling, indicative of active TLR4 signaling, within the lesional skin. These results suggest that Nrf2 normally counter-regulates TLR4-dependent inflammatory activity in the skin, and impaired Nrf2 expression might causally contribute to persistent local inflammation, along with fibrogenesis, in SSc.

Nrf2 has attracted considerable interest as a therapeutic target for various chronic diseases. Bardoxolone methyl CDDO-Me was shown to improve glomerular filtration in diabetic kidney disease (CKD) [53]. While a phase III clinical trial in CKD was recently terminated, two phase II clinical trials of CDDO-Me in pulmonary hypertension are in progress. The potent Nrf2 activator dimethyl fumarate (BG-12, Tecfidera, Biogen) was recently approved for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis [54]. BG-12 attenuated renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction in mice [55]. In the present studies, a novel and clinically-relevant Nrf2 activator showed anti-fibrotic activity in vitro in normal and SSc fibroblasts. Moreover, in mice TMC treatment effectively abrogated the development of skin fibrosis. A limitation of these studies is that the anti-fibrotic efficacy of TMC was determined within the context of only a single, TGF-β-dependent fibrosis model. It is noteworthy, however, that in previous studies, we demonstrated that the Nrf2 activator CDDO had potent anti-fibrotic activity in two distinct mouse models of fibrosis (4). While pharmacological enhancement of Nrf2 activity has been actively pursued for a variety of clinical indications, excessive Nrf2 activation might have adverse consequences [36]. Because Nrf2 promotes cell survival under stress, increased Nrf2 activity could potentially promote cancer cell survival; and loss-of-function mutations in KEAP1 have been found in carcinomas with constitutive Nrf2 activity [56]. Several oncogenes, including KRAS, BRAF and MYC, increase Nrf2 transcription and activity, resulting in an increase in cytoprotective activity in the cell. These observations underline the need for careful evaluation of context- and disease state-dependent biologic and clinical responses to Nrf2 activation.

To explore the mechanism underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of Nrf2, a series of experiments were pursued. We found that in explanted fibroblasts CDDO suppressed ROS generation induced by TGF-β treatment. Excessive ROS accumulation activates latent TGF-β and modulates Smad-dependent and -independent signaling [57]. Remarkably, we found that in normal fibroblasts CDDO caused Nrf2-dependent abrogation of TGF-β-induced collagen synthesis even in the presence of elevated intracellular ROS levels, suggesting that Nrf2 has ROS-independent anti-fibrotic functions. Further evidence showed that Nrf2 abrogated Smad-dependent transcriptional activity by disrupting the requisite interaction of activated Smads with p300, which had been previously shown to be essential for Smad-dependent stimulation of collagen synthesis and related profibrotic TGF-β responses [26]. Competition between Nrf2 and Smad2/3 for limiting amounts of cellular p300 binding may represent a generalized mechanism for regulating TGF-β-dependent responses. The precise mechanism underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of Nrf2 require further study.

In summary, we provide here the first evidence of significantly reduced Nrf2 expression and activity in SSc skin biopsies. The linkage of reduced Nrf2 pathway activation in SSc skin biopsies to genomic evidence of active inflammation and fibrogenesis within the same biopsies suggests critical homeostatic regulatory roles for Nrf2 in SSc. Our findings suggest that Nrf2 represents a potentially druggable target for the treatment of fibrosis in SSc.

Supplementary Material

Brief Commentary.

Background

The transcription factor Nrf2 governs anti-oxidant, innate immune and cytoprotective responses, and its deregulation is prominent in chronic inflammatory conditions, but its expression and function in systemic sclerosis in unknown. We investigated its expression and mechanism of action in SSc samples and mouse models of fibrosis, and the effects of a novel pharmacological Nrf2 agonist.

Translational Significance

Our findings are the first to identify Nrf2 as a cell-intrinsic antifibrotic mediator in maintaining extracellular matrix homeostasis, and a pathogenic role in SSc. Pharmacological re-activation of Nrf2 represents a novel therapeutic strategy toward effective treatment of fibrosis in SSc.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael B. Sporn and Karen T. Liby (Dartmouth Medical School) for inspiration and valuable discussions, and the staff of the Center for Advanced Microscopy and the Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory at Northwestern University for superb technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR-42309 for JV, AR-066418 for JV and AG, AR-065800 for JW, and OD-010945 and CA-060553 for WGT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors have read the journal's policy on conflicts of interest and have no potential conflict of interest to declare. All authors have read the journal's authorship agreement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Varga J. Understanding fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: shifting paradigms, emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(1):42–54. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson ME, et al. Experimentally-derived fibroblast gene signatures identify molecular pathways associated with distinct subsets of systemic sclerosis patients in three independent cohorts. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0114017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liby KT, Sporn MB. Synthetic oleanane triterpenoids: multifunctional drugs with a broad range of applications for prevention and treatment of chronic disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(4):972–1003. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei J, et al. A synthetic PPAR-gamma agonist triterpenoid ameliorates experimental fibrosis: PPAR-gamma-independent suppression of fibrotic responses. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):446–454. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:401–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swamy SM, Rajasekaran NS, Thannickal VJ. Nuclear Factor-Erythroid-2-Related Factor 2 in Aging and Lung Fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(7):1712–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hybertson BM, et al. Oxidative stress in health and disease: the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med. 2011;32(4–6):234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artaud-Macari E, et al. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 nuclear translocation induces myofibroblastic dedifferentiation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(1):66–79. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang JJ, et al. MicroRNA-200a controls Nrf2 activation by target Keap1 in hepatic stellate cell proliferation and fibrosis. Cell Signal. 2014;26(11):2381–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao YY, et al. Metabolomics analysis reveals the association between lipid abnormalities and oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, and Nrf2 dysfunction in aristolochic acid-induced nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12936. doi: 10.1038/srep12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aminzadeh MA, et al. Role of impaired Nrf2 activation in the pathogenesis of oxidative stress and inflammation in chronic tubulo-interstitial nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(8):2038–2045. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thimmulappa RK, et al. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(4):984–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI25790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakos G, et al. Targeted disruption of TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling modulates skin fibrosis in a mouse model of scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(1):203–217. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63289-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu M, et al. Rosiglitazone abrogates bleomycin-induced scleroderma and blocks profibrotic responses through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(2):519–533. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perlish JS, Lemlich G, Fleischmajer R. Identification of collagen fibrils in scleroderma skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;90(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12462561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Distler JH, et al. Imatinib mesylate reduces production of extracellular matrix and prevents development of experimental dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):311–322. doi: 10.1002/art.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushmore TH, et al. Regulation of glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit gene expression: identification of a unique xenobiotic-responsive element controlling inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(10):3826–3830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichikawa T, et al. Dihydro-CDDO-trifluoroethyl amide (dh404), a novel Nrf2 activator, suppresses oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zawel L, et al. Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription activators. Mol Cell. 1998;1(4):611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ecker RC, et al. An improved method for discrimination of cell populations in tissue sections using microscopy-based multicolor tissue cytometry. Cytometry A. 2006;69(3):119–123. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, et al. The Histone Deacetylase Sirtuin 1 Is Reduced in Systemic Sclerosis and Abrogates Fibrotic Responses by Targeting Transforming Growth Factor beta Signaling. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(5):1323–1334. doi: 10.1002/art.39061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fourtounis J, et al. Gene expression profiling following NRF2 and KEAP1 siRNA knockdown in human lung fibroblasts identifies CCL11/Eotaxin-1 as a novel NRF2 regulated gene. Respir Res. 2012;13:92. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng X, et al. Association of increased interferon-inducible gene expression with disease activity and lupus nephritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/art.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra D, et al. Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP-Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(17):5718–5734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMahon M, et al. Keap1-dependent proteasomal degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 contributes to the negative regulation of antioxidant response element-driven gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(24):21592–21600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh AK, et al. p300 is elevated in systemic sclerosis and its expression is positively regulated by TGF-beta: epigenetic feed-forward amplification of fibrosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1302–1310. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Role of Cellular Senescence and NOX4-Mediated Oxidative Stress in Systemic Sclerosis Pathogenesis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(1):473. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0473-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.A G, et al. New insights into the role of oxidative stress in scleroderma fibrosis. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:87–95. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, et al. Catalytic galactose oxidase models: biomimetic Cu(II)-phenoxyl-radical reactivity. Science. 1998;279(5350):537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan K, Kan YW. Nrf2 is essential for protection against acute pulmonary injury in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(22):12731–12736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marangoni RG, et al. Myofibroblasts in murine cutaneous fibrosis originate from adiponectin-positive intradermal progenitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):1062–1073. doi: 10.1002/art.38990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar V, et al. Novel chalcone derivatives as potent Nrf2 activators in mice and human lung epithelial cells. J Med Chem. 2011;54(12):4147–4159. doi: 10.1021/jm2002348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YY, et al. Bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me) as a therapeutic agent: an update on its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2075–2088. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S68872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cullinan SB, et al. The Keap1-BTB protein is an adaptor that bridges Nrf2 to a Cul3-based E3 ligase: oxidative stress sensing by a Cul3-Keap1 ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(19):8477–8486. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8477-8486.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi A, et al. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(16):7130–7139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7130-7139.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connell MA, Hayes JD. The Keap1/Nrf2 pathway in health and disease: from the bench to the clinic. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(4):687–689. doi: 10.1042/BST20150069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buendia I, et al. Nrf2-ARE pathway: An emerging target against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:84–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oruqaj G, et al. Compromised peroxisomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a vicious cycle inducing a higher fibrotic response via TGF-beta signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(16):E2048–E2057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415111112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JM, et al. Nrf2, a multi-organ protector? FASEB J. 2005;19(9):1061–1066. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2591hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oh CJ, et al. Sulforaphane attenuates hepatic fibrosis via NF-E2-related factor 2-mediated inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(3):671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suh JH, et al. Decline in transcriptional activity of Nrf2 causes age-related loss of glutathione synthesis, which is reversible with lipoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(10):3381–3386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400282101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hecker L, et al. Reversal of persistent fibrosis in aging by targeting Nox4-Nrf2 redox imbalance. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(231):231ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luckhardt TR, Thannickal VJ. Systemic sclerosis-associated fibrosis: an accelerated aging phenotype? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27(6):571–576. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilscher M, Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Autophagy and mesenchymal cell fibrogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1831(7):972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau A, et al. A noncanonical mechanism of Nrf2 activation by autophagy deficiency: direct interaction between Keap1 and p62. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(13):3275–3285. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00248-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang K, et al. Sirt1 resists advanced glycation end products-induced expressions of fibronectin and TGF-beta1 by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway in glomerular mesangial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:528–540. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zerr P, et al. Sirt1 regulates canonical TGF-beta signalling to control fibroblast activation and tissue fibrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):226–233. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pekovic-Vaughan V, et al. The circadian clock regulates rhythmic activation of the NRF2/glutathione-mediated antioxidant defense pathway to modulate pulmonary fibrosis. Genes Dev. 2014;28(6):548–560. doi: 10.1101/gad.237081.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho HY, et al. The transcription factor NRF2 protects against pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J. 2004;18(11):1258–1260. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1127fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu W, et al. The Nrf2 transcription factor protects from toxin-induced liver injury and fibrosis. Lab Invest. 2008;88(10):1068–1078. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoh K, et al. Nrf2-deficient female mice develop lupus-like autoimmune nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60(4):1343–1353. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma Q, Battelli L, Hubbs AF. Multiorgan autoimmune inflammation, enhanced lymphoproliferation, and impaired homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in mice lacking the antioxidant-activated transcription factor Nrf2. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(6):1960–1974. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pergola PE, et al. Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(4):327–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stangel M, Linker RA. Dimethyl fumarate (BG-12) for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6(4):355–362. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2013.811826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh CJ, et al. Dimethylfumarate attenuates renal fibrosis via NF-E2-related factor 2-mediated inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sporn MB, Liby KT. NRF2 and cancer: the good, the bad and the importance of context. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(8):564–571. doi: 10.1038/nrc3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu RM, Desai LP. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-beta and reactive oxygen species: A perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.