Abstract

Background:

We previously proposed a technique for quantitative measurement of rest and stress absolute myocardial blood flow (MBF) using a two-injection single-scan imaging session. Recently, we validated the method in a pig model for the long-lived radiotracer 18F-Flurpiridaz with adenosine as a pharmacological stressor. The aim of the present work is to validate our technique for 13NH3.

Methods:

9 studies were performed in 6 pigs; 5 studies were done in the native state and 4 after infarction of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). Each study consisted of 3 dynamic scans: a two-injection rest-rest single-scan acquisition (scan A), a two-injection rest/stress single-scan acquisition (scan B), and a conventional one-injection stress acquisition (scan C). Variable doses of adenosine combined with dobutamine were administered to induce a wide range of MBF. The two-injection single-scan measurements were fitted with our non-stationary kinetic model (MGH2). In 4 studies, 13NH3 injections were paired with microsphere injections. MBF estimates obtained with our method were compared to those obtained with the standard method and with microspheres. We used a model-based method to generate separate rest and stress perfusion images.

Results:

In the absence of stress (scan A), the MBF values estimated by MGH2 were nearly the same for the two radiotracer injections (mean difference: 0.067±0.070 ml/min/cc, limits of agreement: [−0.070,0.204] ml/min/cc), showing good repeatability. Bland-Altman analyses demonstrated very good agreement with the conventional method for both rest (mean difference: −0.034±0.035 ml/min/cc, limits of agreement: [−0.103,0.035] ml/min/cc) and stress (mean difference: 0.057±0.361 ml/min/cc, limits of agreement: [−0.651,0.765] ml/min/cc) MBF measurements. PET and microsphere MBF measurements correlated closely. Very good quality perfusion images were obtained.

Conclusions:

This study provides in-vivo validation of our single-scan rest-stress method for 13NH3 measurements. The 13NH3 rest/stress MPI procedure can be compressed into a single PET scan session lasting less than 15 minutes.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, 13NH3, myocardial blood flow, kinetic modeling, myocardial perfusion imaging

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, with an estimated 8.14 million deaths in 20131. Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) plays a central role in the diagnosis and management of patients with known or suspected CAD2. Over the past decade, positron emission tomography (PET) has emerged as a modality of choice to perform MPI. Because PET imaging incorporates accurate corrections for photon absorption and scatter, it offers the capability to measure absolute myocardial blood flow (MBF) which adds valuable clinical information compared to standard SPECT MPI. Indeed, several studies have shown that absolute MBF can improve the detection and characterization of CAD burden and provides additional prognostic information in patients with subclinical or known CAD3–6.

Typically, PET MPI studies consist of a rest scan followed by another scan acquired during vasomotor stress to evaluate changes in MBF from rest to peak stress. The stress can be induced by intravenous injection of a pharmacological substance2. Presently, the most widely used PET radiotracers for assessing myocardial perfusion are 82Rb and 13NH3. The short physical half-life of 82Rb (1.3 minutes) allows for consecutive rest and stress scans, but its physical and physiological properties are not ideal: relatively high amounts of tracer must be injected that can lead to dead-time issues, possibly limiting the accuracy of the MBF estimates. Moreover, the image quality obtained with 82Rb is ultimately limited by its large positron range (2.6 mm). Rubidium also exhibits a relatively low first pass extraction fraction (~0.6 at 1 ml/min/cc) compared to 13NH3 or the novel flow tracer 18F-Flurpiridaz, complicating its use in absolute flow measurements. On the other hand, 13NH3 exhibits better physical and biological characteristics for MPI. However, because of its half-life (~10 minutes), the rest and stress acquisitions need to be separated by approximately 50 minutes. Consequently, two separate 13N syntheses produced on an onsite cyclotron are required for a rest and stress acquisitions, which economically and logistically limit the current clinical application of 13NH3 MPI.

In order to shorten rest-stress measurements, our group developed a new method that considers the entire rest-stress scan to be a single continuous measurement, thereby eliminating the need for separate rest and stress acquisitions7. The method does not require any extrapolation or subtraction of PET curves which can be inaccurate and therefore introduce some bias. The technique was first characterized with computer simulations for different pharmacological stressors7 and then evaluated in experimental measurements made with 18F-Flurpiridaz in a pig model8.

The aim of the present work is to validate of our single-scan rest/stress imaging method for a short-lived perfusion tracer, 13NH3. To achieve this objective, we compare the single-scan rest/stress imaging method with the standard clinical method which uses separate rest and stress PET acquisitions and stationary tracer kinetic modeling for MBF quantification. We also compared our MBF measurements to microsphere flows as a reference method in a subset of animals.

2. Methods

The data that support the findings of this study as well as analytic methods, and study materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

2.1. Experimental protocol

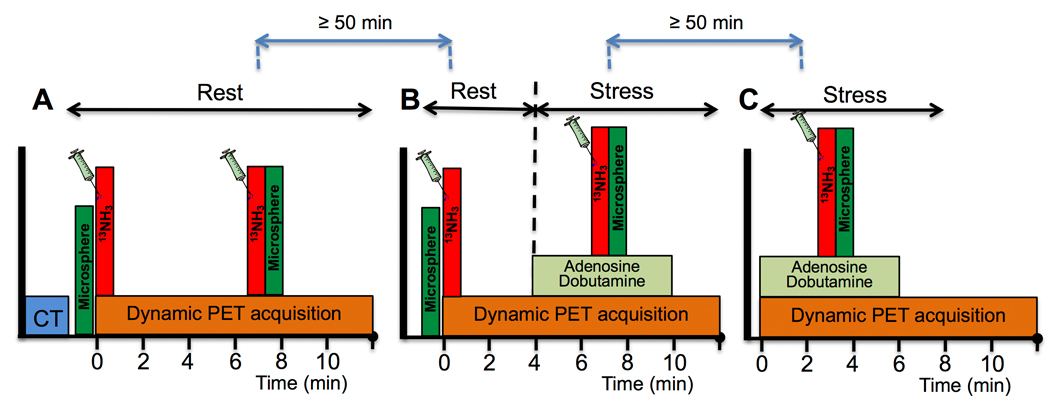

A total of 9 studies were performed in 6 pigs (5 male and 1 female American Yorkshire, vendor: Tufts, Boston, USA) with a total of 27 dynamic PET scans. Average pig weight was 49.8 kg (range 22–97 kg) on the day of study and animal age ranged from 8 to 20 weeks. Five studies were performed in control state (no injury) and 4 after infarction of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. Each study consisted of 3 dynamic PET acquisitions (Figure 1): a two-injection rest/rest single-scan acquisition (scan A, Figure 1.A), a two-injection rest/stress single-scan acquisition (scan B, Figure 1.B), and a conventional one-injection stress acquisition (scan C, Figure 1.C). For clarity, the following naming system was used in this paper to refer to each scan and radiotracer injection: Scan A has Rest A.1 and Rest A.2; Scan B has Rest B.1 and Stress B.2; Scan C has Stress C.1. A waiting period of at least 50 minutes was imposed between consecutive scans to allow time for radioactive decay. The two-injection single scans (scans A and B) consisted of an initial 13NH3 injection (activities were 315±78 MBq at time of injection) given immediately after the start of the PET scanner, followed 7 minutes later by a second 13NH3 injection (activities were 378±61 MBq at time of injection). For the two-injection rest/stress single-scan acquisitions (scan B), a 6-minute adenosine/dobutamine infusion was started 4 minutes after the first 13NH3 injection. Adenosine (140–300 μg/min/kg of body weight) was combined with dobutamine (0–15 μg/min/kg of body weight) in order to maintain blood pressure. Different doses of stressors were used to cover a large range of MBF values. Finally, the conventional one-injection stress scans (scan C) consisted of a single 13NH3 injection (injected activities were 481±78 MBq) given midway through a 6-minute adenosine/dobutamine infusion that was started concomitantly with the PET acquisition. Within each study, the same adenosine/dobutamine dose combinations were used for scan B and scan C. All 13NH3 tracer injections were given intravenously as a bolus over ~25s and were followed by a saline flush. In 4 studies, 13NH3 injections were paired with up to 5 microsphere injections (15 μm diameter, STERIspheres, BioPAL) using different stable labeled microspheres as described in Reinhardt et al.9. Arterial reference blood samples were collected from the femoral artery for 160s using a calibrated pump10. Heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) were recorded at baseline and throughout the infusions of the pharmacological stressors. The rate-pressure product (RPP) was calculated, at baseline as well as during hyperemic stress, as the HR multiplied by the systolic BP (SBP).

Figure 1.

Acquisition diagram summarizing all acquisitions and injections performed during a study. A. Scan A: two-injection rest/rest single-scan acquisition (no stressor infusion). B. Scan B: two-injection rest/stress single-scan acquisition with a 6-minute adenosine/dobutamine infusion. C. Scan C: Conventional one-injection stress scan with a 6-minute adenosine/dobutamine infusion using the same stressor doses as for scan 2. Green boxes indicate microsphere injections, when applicable. Each dynamic PET acquisition lasted a total of 20 minutes. Only the first 12 minutes are represented here for clarity.

2.2. Animal Preparation

Prior to induction of anesthesia, animals were fasted overnight. Following sedation with 4.4 mg/kg of Telazol, the pigs received 5% isoflurane and were intubated. Anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane while on mechanical ventilation. Femoral and ear venous accesses were obtained for tracer injection and infusion of pharmacological stressors. For direct injection of microspheres into the left atrium, access was obtained retrogradely under fluoroscopy by introducing a pigtail catheter through the femoral artery and advancing it into the ascending aorta. An arterio-venous shunt was installed between the femoral artery and femoral vein for withdrawal of reference arterial blood samples. To induce injury in the LAD territory, an angioplasty balloon catheter was fed through a guiding catheter and was inflated to 6–12 atmospheres in the mid LAD artery to block distal blood flow for 80 min. One pig had ventricular fibrillation at 30 minutes, the balloon was then deflated and the angioplasty procedure immediately terminated for the animal’s safety. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

2.3. Image acquisition and reconstruction

All studies were performed on a Siemens Biograph TruePoint 64 PET/CT 3 ring scanner. In each study, a low dose CT was performed prior to the first PET acquisition for attenuation correction purposes. All emission PET data were acquired in 3D list mode for 20 min and dynamic images were reconstructed using a filtered back projection algorithm while applying corrections for attenuation, scatter, random coincidences, normalization and deadtime. The time bins used to frame the emission data were 16×5, 7×10, 9×30, 16×5, 7×10, 9×30, 3×60, 1×180s for the two-injection single-scan acquisitions and 1×180, 16×5, 7×10, 9×30, 2×60, 1×120, 2×180s for the one-injection stress scan acquisitions. For the stress only scans, the first frame of 180s duration, corresponding to data acquired before tracer injection, was discarded before data analysis. Final reconstructed images had voxel sizes of 2.14×2.14×3.0 mm3.

2.4. Data processing

All dynamic PET images were smoothed using a 5 mm FWHM Gaussian filter. Following reorientation of images to the short axis view, the left ventricle (LV) wall was divided based on the standard 17-segment model11 and time activity curves (TAC) were extracted for each segment. Blood pool TACs were derived from ellipsoidal ROIs positioned in the basal portion of the LV chamber (length of each minor axis=1.5cm, length of major axis=3 cm) as well as in the RV chamber (length of each minor axis=1cm, length of major axis=2cm). LV and RV TACs were used in the tracer kinetic modeling for estimation of spill-over fractions. LV TAC was also used as the image derived input function. Tracer kinetic analysis for PET measurements of MBF was performed as described in the section 2.5.

Processing of tissue samples for microspheres flow measurements was performed following a similar procedure as described in Guehl et al.8. In brief, after completion of the imaging study the animals were euthanized with 200 mg/kg of Euthasol while under general anesthesia. The heart was extracted, the right ventricle and atria were removed, and the left ventricle was sliced in 1.5 cm thick short-axis slices. Each slice was then sectioned into 1–2g tissue samples, which were labeled according to the American Heart Association model11. These tissue samples were shipped to BIOPAL for MBF quantification9. Tissue samples were averaged by coronary artery territories to match with PET flow measurements.

2.5. Kinetic modeling and MBF estimation

The two-injection single-scan measurements (scans A and B) were fitted with our non-stationary kinetic model, MGH2, as described in Guehl et al.8. Briefly, this model, with time-varying kinetic parameters, describes the blood flow transition occurring between the rest and stress phases of the scan as an abrupt change starting at time TS after the first tracer injection. In this work, the model parameter TS was set to 4.5 min, relative to the time of the first 13NH3 injection.

For comparison with the standard method, the first 4.5 minutes of the PET data were fitted with a standard one-compartment stationary kinetic model, based on the model initially described in Hutchins et al.12.

Similar to our work with 18F-Flurpiridaz8, for both method we used two spill-over fraction terms per condition (rest and stress) to account for the contribution of the finite spatial resolution (spill-over from left and right ventricular blood pools to the myocardium) and blood volume in the myocardium.

Estimated K1 values were converted to regional MBF by using a modified Renkin-Crone model and validation studies performed in pigs with microspheres as described in Gewirtz et al.13.” The functional form of the model is given by equation 2 where PS (the permeability surface area product) and j (an empiric constant) equal 1.01 and 0.49 respectively. MBF values were then normalized by the RPP using the mean (106 mmHg/s) of the resting RPP values (RPPrest) measured across studies during the first acquisition (equation 1).

| (1) |

| (2) |

The myocardial flow reserve (MFR) was calculated by dividing the MBF at stress by the MBF at rest. All MBF and MFR values presented in this work are normalized by the RPP unless otherwise specified.

2.6. Evaluation of MGH2 MBF measurements

Effect of neglecting the model parameter k3 on the MBF estimates

In our validation work with the tracer 18F-Flurpiridaz, we showed that when using less than 15 min of PET data, the model parameter k3 could be neglected with no significant effect on the estimation of MBF values8. Since part of the injected 13NH3 is converted to glutamine in the myocardial tissue and is subsequently “trapped” within the cells14,12, we also investigated the effect of this model assumption in the present work. To do so, we compared the MBF values estimated while neglecting k3 and using 12 min of data against those estimated while including k3 as a model parameter and using the full 20-minute duration of PET data.

Basic validation and repeatability of MBF estimations

In scan A, because there is no perturbation of blood flow, the MBF values from the two injections must be similar if our method is valid. Therefore, this part of the experiment tests the basic repeatability of the single-scan method by comparing the flow estimates obtained from the back-to-back tracer injections in the absence of stressor infusion (scan A).

Validation of rest and stress MBF estimates

MGH2 flow estimates were compared to MBF measured with the standard method. Resting MBF values obtained with MGH2 from the two-injection single-scan acquisitions (scan A and B) were compared with the resting MBF estimates obtained with conventional kinetic modeling, using the same acquisitions. The stress MBF estimates obtained with MGH2 (scan B) were compared with the stress MBF estimated from scan C using the conventional kinetic modeling method. Corresponding MFR values were also compared. For the MGH2 method, MFR was calculated from MBF values simultaneously estimated from scan B (Rest B.1 and Stress B.2) whereas, for the standard method MFR was obtained from the rest and stress MBF values estimated separately from scan B (Rest B.1) and C (Stress C.1) with the conventional modeling technique. In addition, segmental PET flow estimates were averaged by coronary artery territory and compared to microsphere measurements, as an independent source of validation.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Bland-Altman (BA) plots15 were constructed to assess the agreement between MBF estimates obtained from different methods or modalities. In addition, scatter plots were also presented along with the line of identity to provide visual evidence of the close correlation of the methods compared. All data are expressed as mean value +/− one standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. In addition, agreement between methods was also assessed by computing the average measured intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) among methods or models by use of a two-way mixed-effects model with absolute agreement definition. Lastly, we also used a two one-sided tests of equivalence (TOST) for paired-samples16 in order to test equivalence of rest and stress MBF between our single-scan technique and the conventional method. Based on previous reproducibility studies of MBF measurements with PET17–21, we defined an equivalence margin of 12% that we calculated, for each condition, from the mean rest and stress MBF values measured in this work.

3. Results

3.1. Hemodynamics

Table 1 summarizes the systemic hemodynamics of the pigs studied in this work. Hemodynamics at rest during scan A and scan B were comparable, as were hemodynamics at stress during scan B and scan C. During pharmacological stress, mean heart rate and RPP increased significantly (p<0.0001, paired t-test) compared to resting condition while blood pressure remained relatively constant (p=0.6100, paired t-test). Table 2 shows Systolic BP and HR measured at stress during scan B and scan C for each individual study. In one study, an infarcted animal responded differently between the two consecutive dobutamine-adenosine stresses with a significant increase in HR and important drop in systolic BP (Study 5 in Table 2).

Table 1.

Hemodynamic parameters. HR is heart rate, BP blood pressure and RPP rate pressure product (mean±SD).

| Parameter | Scan A | Scan B | Scan C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest A.1 | Rest A.2 | Rest B.1 | Stress B.2 | Stress C.1 | |

| HR (bpm) | 84±9 | 84±9 | 85±10 | 115±17 | 118±18 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 76±16 | 76±17 | 77±20 | 83±13 | 75±14 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 40±17 | 40±17 | 42±18 | 43±12 | 39±14 |

| RPP (mmHg/s) | 106±25 | 106±27 | 110±34 | 158±31 | 145±27 |

Table 2.

Systolic BP and HR measured at stress during scan B and scan C for each individual study.

| Study | Stress B.2 | Stress C.1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP (mmHg) | HR (BPM) | BP (mmHg) | HR (BPM) | |

| 1 | 85 | 88 | 88 | 85 |

| 2 | 61 | 120 | 56 | 124 |

| 3 | 84 | 143 | 65 | 145 |

| 4 | 67 | 128 | 67 | 124 |

| 5 | 99 | 108 | 57 | 127 |

| 6 | 99 | 109 | 96 | 110 |

| 7 | 88 | 120 | 89 | 123 |

| 8 | 77 | 95 | 75 | 95 |

| 9 | 92 | 121 | 79 | 130 |

3.2. Model fits and segmental MBF estimates

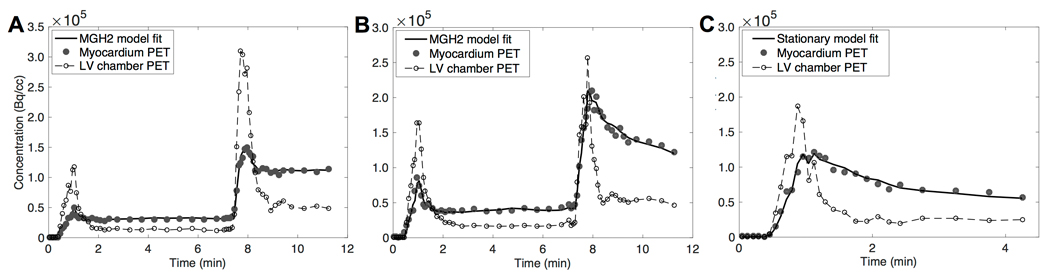

Visual assessment of the model fits revealed that the MGH2 kinetic model fitted the measured 13NH3 TACS acquired with our two-injection single-scan protocol in detail, meaning that the model closely predicted the total concentration measured by the PET camera during the entire study. MBF values estimated with MGH2 while neglecting k3 and using only 12 min of PET measurements were in very good agreement with those obtained while including k3 and using the full 20 minutes duration of data for model fitting. After grouping the data for scans A and B and combining flow data from all injections, the mean difference in MBF was −0.022±0.046 ml/min/cc (Supplemental Figure 1. A and B). The average measure ICC, reflecting the agreement in MBF measurements, was 0.999 with a 95% confidence interval (CI95%) of [0.998,0.999]. Breaking the results down, we found a small underestimation at rest (mean difference: −0.032±0.033 ml/min/cc) and to a lesser extent, at stress (mean difference: −0.012±0.054 ml/min/cc). Because such differences are not clinically significant, the model parameter k3 was neglected and only 12 min of PET data were used in this work for the estimation of MBF.

For comparison, a similar level of agreement in MBF estimates was observed after performing the same test for the standard method (mean difference: −0.042±0.046 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.998 with CI95% of [0.996,0.999]; Supplemental Figure 1.C and D). Figure 2 shows typical model fits obtained for a representative study while using 12 min of data and neglecting k3 as a model parameter. Corresponding model fits while using 20 min of data and including k3 as a model parameter are shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Typical model fits obtained following the acquisition protocol presented in Figure 1. A: Rest-rest scan (scan A); B: Rest-stress scan (scan B); C: Stress alone scan (scan C).

Table 3 shows the rest and peak stress mean MBF values, as well as mean MFR values, calculated across all studies for each of the 3 scans. During hyperemia, mean MBF increased significantly compared to baseline (p<0.0001, paired t-test on global MBF). Mean rest and stress MBF measured by our two-injection single scan method and our MGH2 model were similar to those obtained using the standard method.

Table 3.

MBF and MFR estimates (mean ± SD) obtained from each tracer injection

| Parameter | Scan A | Scan B | Scan C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest A.1 | Rest A.2 | Rest B.1 | Stress B.2 | Stress C.1 | |

| MBF MGH2 (mL/min/cc) | 0.67±0.17 | 0.74±0.20 | 0.76±0.20 | 2.17±1.05 | N/A |

| MBF standard (mL/min/cc) | 0.70±0.18 | N/A | 0.80±0.21 | N/A | 2.11±0.98 |

| MFR MGH2 | N/A | 2.90±1.34 | N/A | ||

| MFR standard | N/A | N/A | 2.68±1.12 | ||

3.3. Evaluation of the single-scan rest and stress MBF estimates

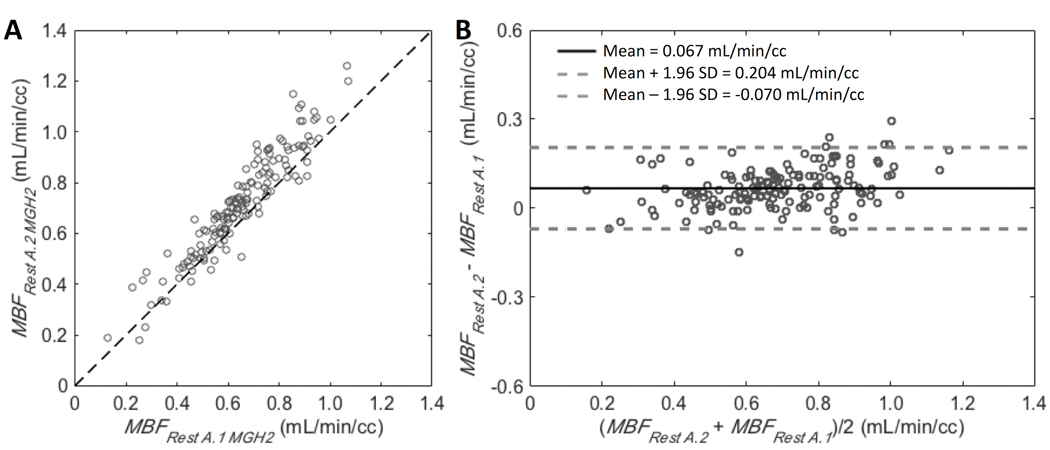

Repeatability of MBF estimations

In the absence of stressor administration (scan A), the MBF values estimated by our MGH2 model were in good agreement for the two-radiotracer injections despite a small, although statistically significant (p=0.0003, paired t test on global MBF), overestimation of flows measured from the second injection compared to those obtained from the first injection (mean difference was 0.067±0.070 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.936 with CI95% of [0.636,0.976]; Figure 3). These results demonstrate the basic repeatability of the method for MBF measurements.

Figure 3.

A: Scatter plot for the 17 segments of all studies (9 scans) comparing the two resting blood flow values simultaneously estimated from Rest A.1 and Rest A.2 by our MGH2 model. Line of identity is shown. B: Corresponding Bland-Altman plot. Bold line is the mean difference between the two resting flow estimates and dashed lines are mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations.

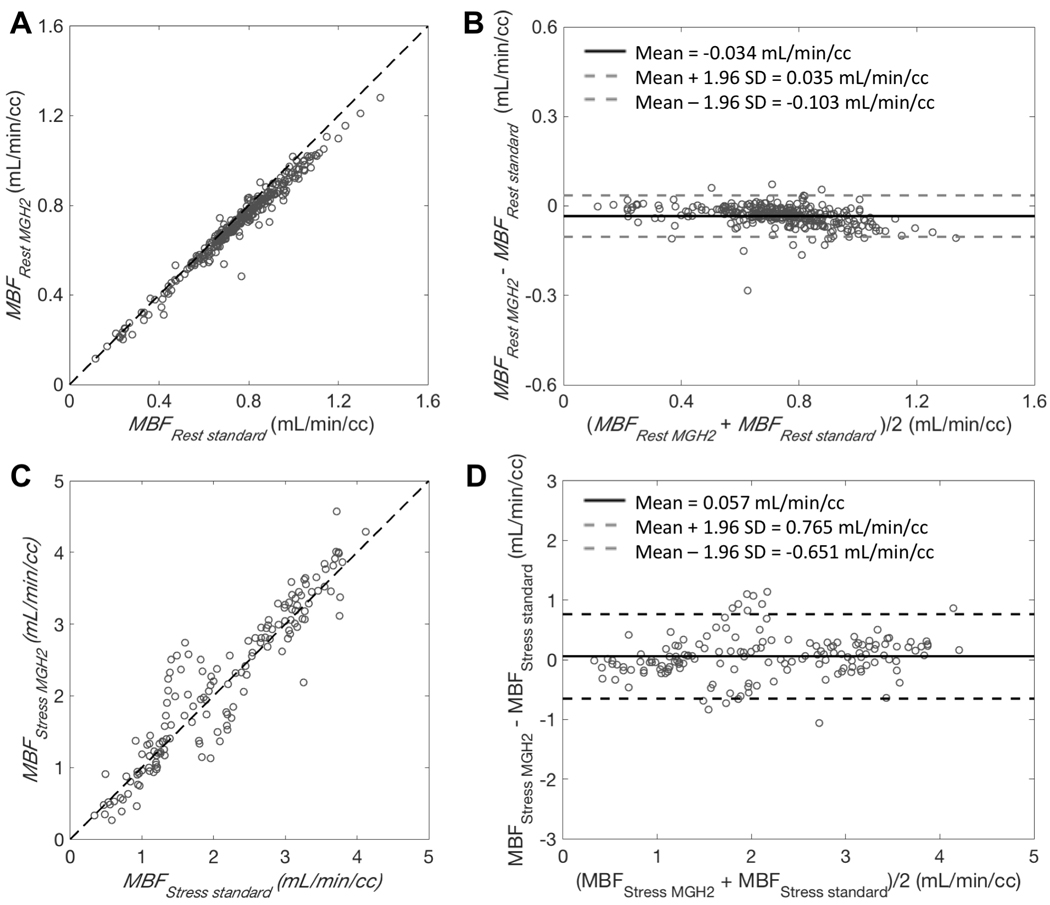

Validation against standard rest and stress PET measurements

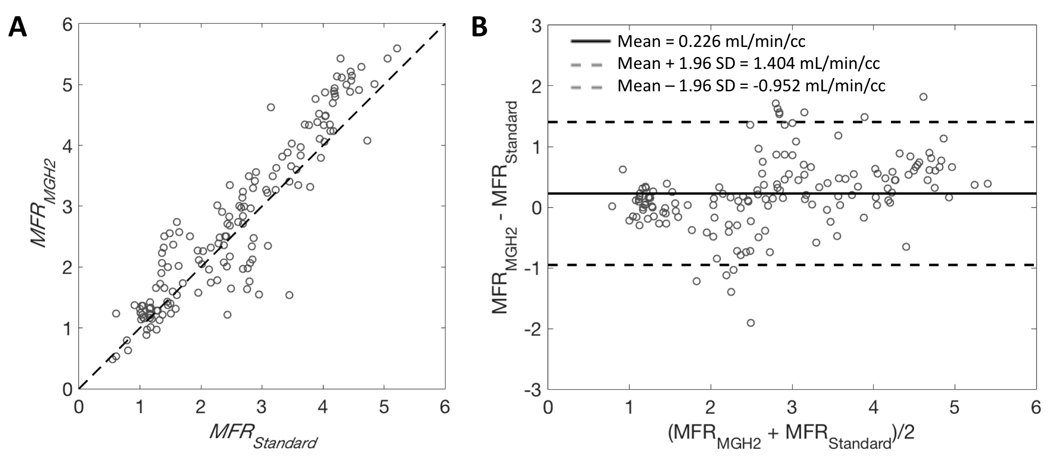

The agreement obtained between resting MBF values (Rest A.1 and Rest B.1) estimated by MGH2 from the two-injection single-scan acquisitions and those estimated by the standard method using only the first 4.5 min of data was very good despite a slight underestimation of MGH2 (mean difference: −0.034±0.035 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.984 with CI95% of [0.890,0.994]; Figure 4.A and B). Likewise, the agreement in stress MBF values was very good between those estimated by MGH2 from Stress B.2 and those estimated by the standard method from Stress C.1 (mean difference: 0.057±0.361 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.967 with CI95% of [0.954,0.976]; Figure 4.C and D).The TOST procedure showed that the MBF values obtained with the two methods were equivalent for both rest (CI95% of [−0.037, −0.031], p<0.0001) and stress (CI95% of [0.009, 0.106], p<0.0001). Consequently, the agreement in MFR values was very good as well (mean difference: 0.226±0.601, average measure ICC=0.929 with CI95% of [0.888,0.953]; Figure 5.B).

Figure 4.

A and C: Scatter plots for MBF estimates (MBFMGH2) obtained with our single-scan method and MBF estimates (MBFstandard) obtained with the conventional method. Dashed lines are lines of identity. B and D: Bland-Altman plots showing the agreement between the two methods. Bold line is the mean difference and dashed lines are mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations. A and B correspond to the comparison of resting flow estimates between the two techniques. Data points are for the 17 segments and estimated from Rest A.1 and Rest B.1 (total of 18 scans). C and D correspond to the comparison of flow estimates measured during pharmacological stress. Data points are for the 17 segments and estimated from Stress B.2 with MGH2 and from Stress C.1 with the standard method (9 pairs of stress studies).

Figure 5.

A: Scatter plot for MFR estimates (MFRMGH2) obtained with our single-scan method and MFR estimates (MFRstandard) obtained with the conventional method. Dashed lines are lines of identity. B: Bland-Altman plots showing the agreement between the two methods. Bold line is the mean difference and dashed lines are mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations. Data points are for the 17 segments with MFR estimates obtained with MGH2 (from Rest B.1 and Stress B.2) paired with the MFR estimated (from Rest B.1 and Stress C.1) using the standard method (9 paired of studies).

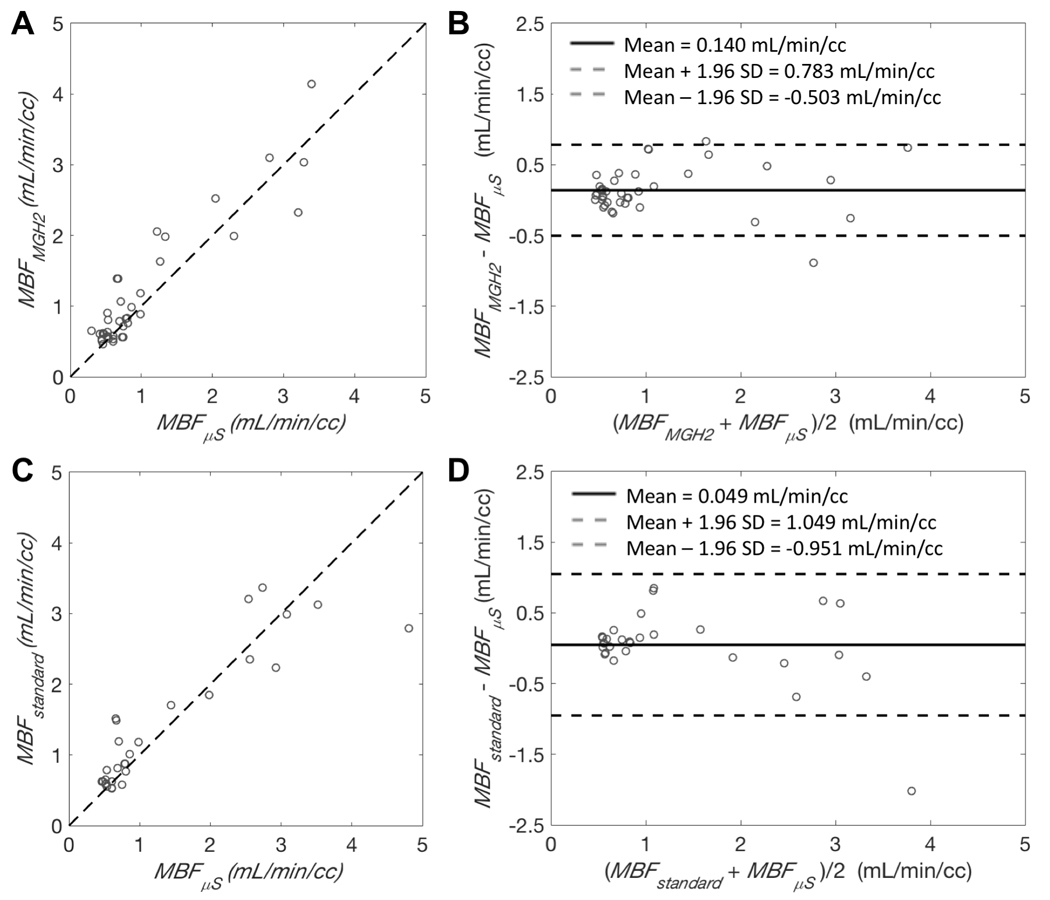

Validation of simultaneous rest-stress against microsphere flow measurements

A total of 16 microsphere injections were performed in 4 different pigs. Out of these 16 injections: 13 of them could be compared with our single-scan method (Figure 6 A and B), 10 of them could be compared with the standard method (Figure 6 C and D). MBF measurements obtained with our single-scan method were in good agreement and correlated closely with microsphere flow (mean difference: 0.140±0.328 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.956 with CI95% of [0.907,0.978]; Figure 6 A and B) and to comparable extent as for the standard method with microsphere flow (mean difference: 0.049±0.510 ml/min/cc, average measure ICC=0.938 with CI95% of [0.871,0.971]; Figure 6.C and D).

Figure 6.

A and C: Scatter plots of the relationship between MBF estimates obtained with PET (MBFMGH2 or MBFstandard) and MBF estimates (MBFμS) obtained from microspheres. Dashed lines are lines of identity. B and D: Bland-Altman plots showing the agreement between the two methods. Bold line is the mean difference and dashed lines are mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations. A and B show the comparison between MGH2 and microsphere measurements. C and D show the comparison between the standard method and microsphere measurements. Data points represent results averaged by coronary territories. Microspheres flows were obtained from a total of 16 different injections in 4 different pigs: A and B result from 13 injections, C and D result from 10 injections.

4. Discussion

Different procedures have been proposed for shortening rest/stress measurements with 13NH3. Rust et al. proposed two methods based on a dual-injection single-scan approach where radiotracer injections during rest and pharmacologically induced stress were separated by 10 minutes22. Although their methods allow rest and stress measurements in 20 minutes of data acquisition, these techniques rely on subtraction and extrapolation of data which can potentially be inaccurate and introduce some bias. In particular, Rust et al. recommend extrapolation of the resting input function to remove the residual activity appearing during the stress portion of the study. However, the residual concentration from the rest study should rightly be included in the stress input because that residual will experience the physiological effects of vasodilation and become part of the stress input; it won’t continue to act as if it is under rest conditions. Our group proposed a more elegant and theoretically more accurate approach, based on the same dual-injection single-scan data acquisition protocol7. In this method, the entire rest/stress scan is considered to be a single measurement in which the MBF is changing as a function of time, and the PET measurements are analyzed with a non-stationary kinetic model, thereby eliminating the need for any extrapolation or subtraction of PET curves. The technique was first characterized with computer simulations for different pharmacological stressors7 and subsequently evaluated in experimental measurements made with 18F-Flurpiridaz in a pig model8. In this work, we validated our two-injection single-scan method in a porcine model for simultaneous rest/stress 13NH3 studies. In anticipation of future validation studies in humans, we chose the standard clinical method, that is separate rest and stress acquisitions, as the reference for evaluation of our flow measurements as well as our model-based generated perfusion images (Supplemental Material). This choice was also motivated by the high reproducibility of regional MBF measurements as previously reported by several studies17–21.

We found very good agreement between MBF values estimated by MGH2 and those obtained by the standard method for both rest and stress, resulting in a very good agreement between MFR values. Rest MBF measurements obtained with MGH2 were validated against the rest MBF measurements obtained with the standard method for the same PET acquisitions using the first 4.5 min of data, whereas the stress MBF estimates were validated against those measured from a separate PET acquisition (scan C). Consequently, the differences in stress MBF estimates observed between the two methods were increased due to the additional experimental variation in repeated scan acquisitions as well as variation in adenosine/dobutamine response. Normalizing the MBF estimates to the RPP accounted for most of these differences. Nonetheless, the level of agreement between the stress MBF values estimated by MGH2 and those obtained from a separate scan with the standard method was well within the interstudy reproducibility (~11%) reported by others using the same tracer19. More importantly, as demonstrated by the equivalence test, for both rest and stress flows the observed differences would not be considered clinically significant in human studies. The comparison with the microsphere measurements further confirmed that rest and stress flow measurements obtained with MGH2 were equivalent to those obtained with the standard method as the level of agreement between PET measurements and microsphere flows were similar for both techniques. From these results, we can therefore conclude that accurate and precise MBF measurements were obtained for both rest and stress and no significant bias was introduced by our simultaneous rest/stress estimation method.

It is important to note that in this work, dobutamine was used at relatively low doses for the purpose of maintaining blood pressure during pharmacological stress. The kinetic model in its current form might not be suitable for dobutamine-alone stress-test because, the main MGH2 model assumption, that is flow changes abruptly at the start of the stressor infusion, might be violated. Adenosine and dobutamine have different pharmacodynamics, with a biological half-life of ~2 minutes for dobutamine23,24 and only few seconds for adenosine25,26. In this work, fixing TS to the start of the stressor infusion provided good model fits, suggesting that all the information present in the PET measurements was correctly modeled.

Finally, since neglecting the parameter k3 while using only 12 min of data did not introduce any significant bias in MBF estimation, we were able to use our rapid computation method to generate the rest and stress perfusion images as if these images were acquired from separate rest and stress measurements (Supplemental Material and Supplemental Figure 3). The model-based perfusion images were nearly identical to those acquired separately (Supplemental Figures 4 and 5).

In conclusion, we validated our two-injection single-scan method for the radiotracer 13NH3 in experimental measurements obtained with pigs. We showed that accurate and precise estimates of rest and stress MBF can be obtained using a 12 min PET acquisition. For the broad range of flow values investigated in this work, our method was in very good agreement with the standard clinical method that uses separate rest and stress scans. We also showed that our method provides good quality standard rest and stress perfusion images as if those were acquired separately. Our method could significantly reduce the cost of 13NH3 MPI imaging through optimization of camera time and cyclotron usage, as only one 13N production is required. Finally, validation of the method in human subjects is warranted for future clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) plays an essential role in the diagnosis and risk stratification and management of patients with known or suspected CAD. Positron emission tomography (PET) has developed as a modality of choice for conducting MPI studies, in part because PET adds the capability of measuring myocardial blood flow (MBF) in absolute units of mL/min/g of tissue, which adds valuable clinical information compared to standard MPI. Typically, a scan is performed at rest followed by another scan during vasomotor stress where the stress response can be induced by intravenous injection of a pharmacological substance, in order to evaluate changes in MBF from rest to peak stress. One limitation of these studies is that radioactivity from the rest scan must not affect the stress scan, making it necessary to wait 3 to 5 half-lives between studies for sufficient radioactive decay to occur. To circumvent this issue, our group recently proposed an elegant approach, based on a dual-injection single-scan rest/stress data acquisition protocol and a non-stationary kinetic model. The present preclinical study, conducted in a pig model, supports the validity of this method for the FDA approved radiotracer 13NH3. The results obtained showed that rest/stress MPI procedure can be compressed into a single PET scan session, lasting less than 15 minutes and requiring only one cyclotron production of 13N, while still obtaining accurate rest and stress MBF measurements and very good quality perfusion images.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the 2017 Bradley-Alavi Fellowship and NIH grant R01HL137230. The authors thank Julia Scotton, Eric McDonald and Brittan Morris for animal preparation, handling and monitoring, Dave Lee and Dr. Hamid Sabet for the production of radiotracer as well as Dr. Daniel Albrecht and Dr. Eline Verwer for their help during experimental measurements.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the 2017 Bradley-Alavi Fellowship and NIH grant R01HL137230.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Meserve J, El Fakhri G, Sitek A, Moore SC. Clinical myocardial perfusion PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:783–93. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.032789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler TH, Nitzsche EU, Schelbert HR, Olschewski M, Sayre J, Mix M, Brink I, Zhang XL, Kreissl M, Magosaki N, et al. Positron emission tomography-measured abnormal responses of myocardial blood flow to sympathetic stimulation are associated with the risk of developing cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengel FM. Leaving relativity behind: quantitative clinical perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:749–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, Guo A, Chow BJ, Renaud JM, Ruddy TD, Sarveswaran N, Tee RE, Beanlands RS. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58: 740–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Gaber M, Di Carli G, Blankstein R, Dorbala S, Sitek A, Pencina MJ, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alpert N, Dean Fang YH, El Fakhri G. Single-scan rest/stress imaging (18)F-labeled flow tracers. Med Phys. 2012;39:6609–20. doi: 10.1118/1.4754585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guehl NJ, Normandin MD, Wooten DW, Rozen G, Sitek A, Ruskin J, Shoup TM, Ptaszek LM, El Fakhri G, Alpert NM. Single-scan rest/stress imaging: validation in a porcine model with 18F-Flurpiridaz. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017a;44:1538–46. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhardt CP, Dalhberg S, Tries MA, Marcel R, Leppo JA. Stable labeled microspheres to measure perfusion: validation of a neutron activation assay technique. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;280:H108:16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heymann MA, Payne BD, Hoffman JI, Rudolph AM. Blood flow measurements with radionuclide-labeled particles. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1977;20:55–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennel DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS; American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial Segmentation and Registration for Cardiac Imaging. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healtcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committe of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchins GD, Schwaiger M, Rosenspire KC, Krivokapich J, Schelbert H, Kuhl DE. Noninvasive quantification of regional blood flow in the human heart using N-13 ammonia and dynamic positron emission tomographic imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:1032–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gewirtz H, Fischman AJ, Abraham S, Gilson M, Strauss HW, Alpert NM. Positron emission tomographic measurements of absolute regional myocardial blood flow permits identification of nonviable myocardium in patients with chronic myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krivokapich J, Smith GT, Huang SG, Hoffman EJ, Ratib O, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. 13N ammonia myocardial imaging at rest and with exercise in normal volunteers. Quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion with dynamic positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1989;80:1328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuirmann DJ. A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987;15:657–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagathesan R, Kaufmann PA, Rosen SD, Rimoldi OE, Turkeimer F, Foale R, Camici PG. Assessment of the long-term reproducibility of baseline and dobutamine-induced myocardial blood flow in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:212–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Yap JT, Rimoldi O, Camici PG. Assessment of the reproducibility of baseline and hyperemic myocardial blood flow measurements with 15O-labeled water and PET. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1848–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagamachi S, Czernin J, Kim AS, Sun KT, Böttcher M, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Reproducibility of measurements of regional resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow assessed with PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1626–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, Dorbala S, Abi-Hatem N, Lahoud Y, Fischman A, Coughlan M, Yasuda T, Di Carli MF. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with (82)Rb PET: comparison with (13)N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1062–71. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.104.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chareonthaitawee P, Christenson SD, Anderson JL, Kemp BJ, Hodge DO, Ritman EL, Gibbons RJ. Reproducibility of measurements of regional myocardial blood flow in a model of coronary artery disease: comparison of H215O and 13NH3 PET techniques. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rust TC, DiBella EV, McGann CJ, Christian PE, Hoffman JM, Kadrmas DJ. Rapid dual-injection single-scan 13N-ammonia PET for quantification of rest and stress myocardial blood flows. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:5347–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kates RE, Leier CV. Dobutamine pharmacokinetics in severe heart failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24:537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daly AL, Linares OA, Smith MJ, Starling MR, Supiano MA. Dobutamine pharmacokinetics during dobutamine stress echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson RF, Wyche K, Christensen BV, Zimmer S, Laxson DD. Effects of adenosine on human coronary arterial circulation. Circulation. 1990;82:1595–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:761–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.