Abstract

Fear conditioning and extinction (FCE) are vital processes in adaptive emotion regulation and disrupted in anxiety disorders. Despite substantial comorbidity between alcohol dependence (ALC) and anxiety disorders and reports of altered negative emotion processing in ALC, neural correlates of FCE in this clinical population remain unknown. Here, we used a two-day fear learning paradigm in 43 healthy participants and 43 individuals with ALC at the National Institutes of Health. Main outcomes of this multimodal study included structural and functional brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinical measures, as well as skin conductance responses (SCRs) to confirm differential conditioning. Successful FCE was demonstrated across participants by differential SCRs in the conditioning phase and no difference in SCRs to the conditioned stimuli in the extinction phase. The ALC group showed significantly reduced blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) responses in the right amygdala during conditioning (Cohen’s d= .89, P(FWE)=.037), and in the left amygdala during fear renewal (Cohen’s d= .68, P(FWE)=.039). Right amygdala activation during conditioning was significantly correlated with ALC severity (r= .39, P(Bonferroni)= .009), depressive symptoms (r= .37, P(Bonferroni)= .015), trait anxiety (r= .41, P(Bonferroni)= .006), and perceived stress (r= .45, P(Bonferroni)= .002). Our data suggest that individuals with ALC have dysregulated fear learning, in particular, dysregulated neural activation patterns in the amygdala. Furthermore, amygdala activation during fear conditioning was associated with ALC-related clinical measures. The FCE paradigm may be a promising tool to investigate structures involved in negative affect regulation, which might inform the development of novel treatment approaches for ALC.

Keywords: addiction, alcohol use disorder, amygdala, anxiety, depressive symptoms, fear conditioning

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a chronic relapsing disorder with significant morbidity and mortality.1 The underlying pathophysiology is still poorly understood but robust evidence suggests that the ability to regulate negative emotions is often impaired in individuals with AUD and predictive of alcohol use.2,3 Furthermore, there is substantial comorbidity between AUD and anxiety disorders, possibly indicating shared neurobiological pathways.4–6 Fear conditioning and extinction (FCE) are crucial for adaptive emotion regulation and functional neural activation has been shown to differ in individuals with anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to controls.7–11 While preclinical studies indicate impairments in fear conditioning (i.e., continued increased behavioral responses to conditioned cues) and disrupted extinction learning (i.e., continued fear responses) in rodent alcohol models,12,13 there have been no studies investigating neural correlates of FCE in individuals with AUD to date.

Classical/Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigms include a conditioning phase where a previously neutral conditioned stimulus (CS+) (e.g., blue light) is repeatedly paired with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US) (e.g., electrical stimulation), while another stimulus (CS-) (e.g., yellow light) is never paired with the US (see Fig. 1). After repeated pairings, the CS+ elicits a conditioned fear response (CR), that can be measured (i.e., larger skin conductance response (SCR) to the CS+ compared to the CS-). Next, the CS+ is presented without the US until the CR ceases to occur (i.e., there is no longer a difference in SCR to the CS+ compared to the CS-; extinction phase). This results in two distinct emotional memories of the CS+: the conditioning memory and the extinction memory.14 While the appropriate expression of these emotional memories (CRs) allows for the dynamic adjustment of behavioral responses to a changing environment (i.e., the correct recall of an extinction memory; extinction recall), inappropriate expression of an extinguished CR (i.e., renewal of a conditioning memory) can lead to nonadaptive behaviors. In short, fear conditioning and extinction represent learning processes, while extinction recall and fear renewal represent memory processes. In substance use disorders, cue-induced drug-/alcohol-seeking after a period of abstinence is one example of the renewal of a conditioned behavior. While studies in anxiety disorders and PTSD have largely found no group differences in SCR during conditioning and extinction,10,15,16 some studies report increased SCRs in individuals with PTSD during extinction recall,15,16 indicating a deficit in the use of contextual cues for appropriate memory expression.

Figure 1.

Digital photographs of two different rooms were used as the conditioning context (CX+; office) and extinction context (CX-; conference room), respectively. Both rooms contained a lamp with a black lamp shade that turned blue or yellow, constituting the conditioned stimuli (CS). During fear conditioning, one of the colors (blue) was followed by a 0.5-second electrical stimulation (CS+) in 75% of the trials, while the other (yellow, not shown) was never followed by a shock (CS-). During extinction, the CS+ was presented in the CX- and never followed by a shock. On day 2, participants were presented with the CS+ and CS- in the CX+ (fear renewal phase) and in the CX- (extinction recall phase). No shocks were delivered.

Neuroimaging studies in healthy individuals and anxiety disorders have identified a network of brain structures involved in FCE, that includes (1) the amygdala (conditioning, extinction, fear renewal),10,15,17–19 (2) medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; conditioning, extinction, extinction recall, fear renewal),10,15,17,19,20 (3) hippocampus (conditioning, extinction, extinction recall),10,17,19,20 (4) insula (conditioning, extinction, extinction recall),10,19,20 and (5) anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; conditioning, extinction, extinction recall).10,18–21 The same structures are functionally altered during cognitive, reward, and emotion processing in AUD and other substance use populations,22–26 suggesting a potential overlap and common entry point for some shared neurobiology. The amygdala, in particular, plays a key role in both the withdrawal/negative affect and preoccupation/anticipation stage of the addiction cycle.27 Furthermore, cue-induced mPFC activation predicts relapse in patients with alcohol dependence.28 Despite the direct relevance of conditioned responses for the development and maintenance of AUD (i.e., cue-induced alcohol-seeking), as well as relapse (i.e., cue-induced craving), there have been no FCE neuroimaging studies in this population. However, one prior psychophysiological study found that fear conditioning was impaired in college-aged binge drinkers compared to non-binge drinkers, such that bingers did not display a greater SCR to the CS+ compared to the CS- that was observed in non-bingers.29 Similarly, Finn et al.30 found significantly smaller SCRs to the CS+ during fear conditioning in healthy men with a family history of alcohol dependence compared to controls. Furthermore, healthy carriers of a risk variant for alcohol dependence showed blunted amygdala activation during fear conditioning,31 which was consistent with previous reports of diminished amygdala activation during negative emotional face processing in individuals with a family history of alcohol dependence or long-term abstinent alcohol-dependent patients.26,32 Using the FCE paradigm to investigate the neurobiological underpinnings of negative emotion regulation in patients with AUD could crucially extend our understanding of negative affect during early abstinence. Identifying clinically relevant intermediate phenotypes has been proposed as a tool contributing to a promising translational biomarker strategy for the development of novel treatments for AUD.33

The present study is the first to investigate neural correlates of FCE in inpatients with alcohol dependence (ALC) and healthy controls (HC) using an established 2-day differential FCE protocol. We hypothesized that, relative to HC, ALC would have different neural activation patterns in key FCE-related brain structures, including reduced amygdala activation during fear learning. Furthermore, we hypothesized that neural dysregulation would be associated with a more severe alcohol- and negative emotion-related phenotype. We hypothesized that differential SCRs to the conditioned cues, specifically, larger SCRs to the CS+ compared to the CS-, would confirm that conditioned fear responses have been acquired, and similar SCRs to the CS+ and CS- would demonstrate successful extinction. Finally, we hypothesized that, relative to HC, ALC would show reduced SCRs to the CS+ during conditioning.

Methods

Participants

Eighty-six participants (43 ALC, 43 HC) were recruited to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, USA. All participants met the following inclusion criteria: 21–65 years of age, ability to provide written informed consent, and cleared venous access assessment. In the ALC group, participants met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID),34 specified alcohol as their preferred drug, and reported alcohol consumption within the last 30 days as assessed by the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB).35 Non-treatment-seekers had to agree to abstain from alcohol one day prior to study participation. The present study is part of a larger protocol (NIAAA 15-AA-0127) which includes a more comprehensive focus on early life stress (ELS) in AUD. As such, ALC and HC were recruited with no early life stress (ELS-) or moderate to severe early life stress (ELS+), as determined by a minimum score of moderate level of exposure for at least two categories of ELS or one severe level of exposure for at least one category of ELS as measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ).36 While ALC and HC did not significantly differ on this criterion, a lack of power prevents a closer investigation of ELS in this initial analysis. However, all analyses of the present investigation controlled for ELS status.

Participants were excluded from study participation if they presented with neurological symptoms of the wrist or arm as determined by history or physical exam, reported chronic use of psychotropic medications within 4 weeks or fluoxetine within 6 weeks of the study, reported incidental use of psychotropic medication prior to study participation within a time period of less than 5 half-lives of the medication in question. Furthermore, exclusion criteria included the presence of ferromagnetic implants, pregnancy, breastfeeding, left-handedness, claustrophobia, MRI-incompatible intrauterine device (IUD), as well as the presence of any DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or current substance dependence other than alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine. Non-treatment-seekers were excluded if they reported a history of epilepsy or alcohol-related seizures, or presented with significant alcohol withdrawal symptoms, defined as a score above 8 on the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar)37 on any study day. For the HC group, exclusion criteria included the presence of any current or past DSM-IV diagnosis of ALC or alcohol abuse, positive alcohol breathalyzer or urine drug tests, self-identifying as an alcohol abstainer or reporting the desire to seek treatment for alcohol problems.

Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the NIAAA Institutional Review Board and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were administered the SCID to determine eligibility. Furthermore, participants completed the TLFB, CTQ, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory -Y2 (STAI),38 Fagerstrӧm Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),39 Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS),40 Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),41 as well as the Brief Anxiety (BSA) and Montgomery-Asberg Depression (MADRS) scales.42 ALC further completed the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS)43 and the CIWA-Ar at admission.

FCE Paradigm

The MRI FCE paradigm took place once individuals were free of any withdrawal symptoms on two consecutive days with habituation, conditioning, and two extinction blocks on Day 1 and extinction recall and renewal blocks on Day 2 (Fig. 1). At the beginning of each day, two Ag/AgCl electrodes (41mm diameter) were placed on the palm of the participants’ left hand to obtain galvanic skin responses throughout the fMRI session. Two additional electrodes were attached to the wrist of the same hand to deliver the electrical stimulation (US; .5 s duration). On the first day, participants underwent a personalized work-up procedure to titrate the intensity level of the electrical stimulation to a level they rated as uncomfortable but not significantly painful. Digital photographs of two different rooms (a conference room with two chairs and an office with a desk) were used as the conditioning/extinction context (CX+/−) (Fig. 1). Both rooms contained a lamp with a black lamp shade that turned blue or yellow, constituting the conditioned stimuli (CSs). During conditioning, one of the colors was followed by a 0.5-second electrical stimulation (CS+) in 75% of the trials, while the other was never followed by a shock (CS-) in the CX+. During extinction, the CS+ was presented in the CX- and never followed by a shock. On day 2, participants were presented with the CS+ and CS- in the CX+ (fear renewal) and in the CX- (extinction recall); no shocks were delivered (see Fig. 1). Detailed procedures of this well-established paradigm are provided in the Supplement.

MRI Data Acquisition

Imaging data were acquired using a 3T SIEMENS Skyra magnetic resonance scanner with a 20-channel head coil. The whole-brain functional scan was collected using an echoplanar-imaging pulse sequence (36 axial slices, 3.8 mm slice thickness, 24 × 24 field of view, TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 msec, 90° flip angle). For structural images, high-resolution T1-weighted images were acquired with a MPRAGE sequence (TR = 1900 ms, TE = 3.09 ms, flip angle = 10°, FOV = 240 mm×240 mm, 1 mm slice thickness, and 144 slices) each day prior to the acquisition of the functional imaging data.

Data Processing

Neuroimaging Data.

Functional and structural data were processed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12b, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) based on MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). After removal of the first three individual functional scans per experimental phase to avoid artefacts caused by magnetic saturation effects, and prior to preprocessing, all images were visually controlled for gross movement artefacts and anatomical abnormalities. Data sets of two subjects for fear renewal blocks and one subject’s data set for extinction recall were excluded due to low quality (i.e., corrupt imaging scans or missing logfile). The remaining scans were further corrected for signal‐to‐noise decrease in single slices, using the denoising function of the ArtRepair software.44 Afterwards, each set of scans per experimental phase (fear conditioning, extinction, extinction recall, fear renewal) was spatially realigned to correct for head motion and normalized using the warping parameters estimates of the individual co-registered and segmented MPRAGE image. Images were normalized to an isovoxel size of 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm. Subsequent smoothing was done using an isotropic Gaussian kernel (8 mm FWHM).

Structural images were preprocessed using the standard procedure of CAT12 Toolbox implemented in SPM12b (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). Images were spatially normalized applying high-dimensional DARTEL registration and segmented using the SPM12 tissue probability maps. Individual modulated normalized images were written for the segmented grey matter tissue (GM), white matter tissue and the cerebrospinal fluid, and individual total intracranial volume (TIV) was estimated. Data quality was checked via proof of the saved estimated quality parameters, proof of sample homogeneity, and additional visual inspection, which led to the inclusion of all 86 subjects’ GM images. Finally, GM images were smoothed with an 8mm-FWHM isotropic Gaussian smoothing kernel.

For detailed descriptions of SCR data processing, see Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Skin Conductance Data Analysis.

For conditioning, a stimulus (CS+ vs. CS-) × time (early vs. late conditioning) × group (ALC vs. HC) mixed model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted on the SCR data. For extinction, a stimulus × time (conditioning vs. extinction) × group ANCOVA was performed. For extinction recall and renewal, stimulus × group ANCOVAs were performed on the SCR in the first trial. Furthermore, each subject’s SCR to the first three CS+ trials of the extinction recall phase was divided by their largest SCR to a CS+ trial during the conditioning phase and then multiplied by 100, yielding a percentage of maximal conditioned responding. This in turn was subtracted from 100% to yield an “extinction retention index”,11 on which a Mann-Whitney U test was conducted. All SCRs were square-root transformed before analyses were conducted and Greenhouse Geisser-corrected values are reported. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, two-tailed, and all SCR analyses controlled for age, gender, and binary ELS status.

MRI Data Analysis.

The pre‐processed fMRI data were analyzed as a block design for each experimental phase in the context of the general linear model approach using a two‐level procedure. On the individual single subject level, the different conditions (CS+ and CS-) were modeled (boxcar functions convolved with the hemodynamic response function) as explanatory variables together with the six movement parameters to account for residual variance due to head motion, and a single constant representing the mean over scans. Following Phelps et al.,18 both CS+ and CS- conditions in the fear conditioning phase were modeled as separate regressors for trials 2–20 since learning of CS+ (potential shock) versus CS- (no shock) has not occurred yet during the first trial. Similarly, for extinction, regressors for CS+ and CS- trials 2–15 (again excluding the first trial since extinction learning has not occurred yet during the first trial) were modeled. For extinction recall and fear renewal, regressors were modelled for the complete length of block trials (1–15) for CS+ and CS- presentation. Subsequently, for each subject, linear contrast images were computed for fear conditioning: ‘CS+ minus CS-’ (trials 2–20); extinction: ‘CS+ minus CS-’ (trials 2–15); recall: ‘CS+ minus CS-’ (all trials 1–15); renewal: ‘CS+ minus CS-’ (all trials 1–15). Additional exploratory linear contrast images were modeled for ‘CS+ only’ and ‘CS- only’ for each of the above specified trials in each phase. For these individual contrast images, within group blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) responses and group comparisons were assessed with one-sample and two‐sample t‐tests, respectively15; all analyses controlled for age, gender, and binary ELS status.

ROI Analyses.

We specifically tested pivotally involved brain areas of the fear circuitry.9–11 In detail, anatomical atlas-based a priori Regions of Interest (ROIs) for small volume family-wise alpha error (FWE) adjustment were created for the left/right amygdala, left/right hippocampus, left/right mPFC (i.e., aal-mask for Front_Med_Orb), left/right insula, left/right rostral ACC (rACC, ROI as defined by Charlet, Schlagenhauf, Richter, Naundorf, Dornhof, Weinfurtner, König, Walaszek, Schubert, Müller23) using the WFU PickAtlas toolbox (http://fmri.wfubmc.edu/software/PickAtlas).45

Statistical Thresholds.

We tested our hypotheses based on these ROIs at a small volume cluster-level corrected statistical threshold of P(FWE)< 0.05 (identifying significant clusters with an initial voxel-level threshold of P(uncorrected) < 0.005) and outside of ROIs for whole-brain activations at a cluster-level corrected statistical threshold of P(FWE)< 0.05 (identifying clusters with an initial voxel-level threshold of P(uncorrected) < 0.005 and a minimal cluster extent of ~257 mm3 which equals six contiguous voxels); resembling the cluster detection approach of previous studies.10,15 If ROI clusters survived the FWE-correction, effect sizes for the detected ROI BOLD group differences were calculated using the Effect of Size Calculator (https://ncalculators.com/statistics/effect-of-size-calculator.htm; accessed 07/24/2019). Additionally, parameter estimates of the ROI BOLD response were extracted from the cluster peak as SPM eigenvariates for exploratory correlational analyses and are reported at a Bonferroni-corrected statistical threshold of P=.025 (P=0.05/2; testing two ROI BOLD parameter estimates on clinical measures) to account for multiple testing.

Exploratory Association Analyses.

For additional exploratory association analyses with both significant amygdala BOLD group differences, unilateral amygdala GM volumes were extracted as SPM eigenvariates from a one-sample t-test (ALC group only), controlling for individual TIV in order to correct for differences in brain sizes, masking GM volumes for the left and right amygdala-ROI, separately. Prior to association analyses, measures were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov-test and according bivariate Spearman or Pearson correlations were performed. Corresponding MNI brain region coordinates were labeled with the WFU PickAtlas toolbox.45

Results

Demographics

Forty-three HC (55.81% female) and 43 ALC (32.56% female) participated in this study (for detailed demographics, see Table 1). The average shock level participants selected for the unconditioned stimulus (US) did not differ between ALC (M= 2.73 mA, SD= 1.27) and HC (M= 2.73 mA, SD= 1.83), t(60)= 0.01, P= .996, and ranged from 0.49 mA to 9.00 mA.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and characteristics

| Healthy Controls (N = 43) | Individuals with Alcohol Dependence (N = 43) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 24 (55.81) | 14 (32.56) | |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 38.85 (11.78) | 45.95 (11.07) | .005 |

| FTND, mean (SD) | 0 (0.0) | 1.93 (2.49) | <.0001 |

| History of Early Life Stress, N (%) | 17 (39.53) | 26 (60.47) | .052 |

| Number of Heavy Drinking Days in Past 90 Days, mean (SD) | 0.47 (1.82) | 67.63 (27.81) | <.0001 |

| Average Number of Drinks per Drinking Day, mean (SD) | 1.35 (0.89) | 14.34 (8.97) | <.0001 |

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Score, mean (SD) | 1.26 (2.84) | 13.98 (9.53) | <.0001 |

| BSA Anxiety, mean (SD) | 0.81 (1.58) | 10.53 (7.84) | <.0001 |

| STAI Score, mean (SD) | 28.23 (7.74) | 47.98 (11.32) | <.0001 |

| PSS Stress Scale, mean (SD) | 9.62 (6.47) | 21.44 (7.04) | <.0001 |

| ADS, mean (SD) | 0.71 (1.50) | 21.33 (8.52) | <.0001 |

| CIWA, mean (SD) | 0.12 (0.39) | 4.56 (3.77) | <.0001 |

| DSM-IV/DSM-5 Diagnosis, Lifetime | |||

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 1 (2.33) | 5 (11.63) | .090 |

| Other Specified Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.33) | .314 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.30) | .041 |

| Social Anxiety | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.65) | .152 |

| Agoraphobia without Panic Disorder | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.33) | .314 |

| Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified/Other Specified Anxiety Disorder | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.63) | .021 |

| Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder/Major Depressive Disorder | 1 (2.33) | 11 (25.58) | .002 |

| Dysthymic Disorder/Persistent Depressive Disorder | 1 (2.33) | 4 (9.30) | .167 |

| Other Specified Depressive Disorder | 1 (2.33) | 1 (2.33) | 1.0 |

Note. SD = standard deviation, FTND = Fagerstrӧm Test of Nicotine Dependence, BSA = Brief Scale for Anxiety, STAI = Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y2, PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, ADS = Alcohol Dependence Scale, CIWA = Clinical Withdrawal Assessment-Alcohol Revised. DSM-IV comorbidities include current and past diagnoses; DSM-5 comorbidities include lifetime diagnoses. Boldface indicates significant between-group differences.

Skin Conductance Responses

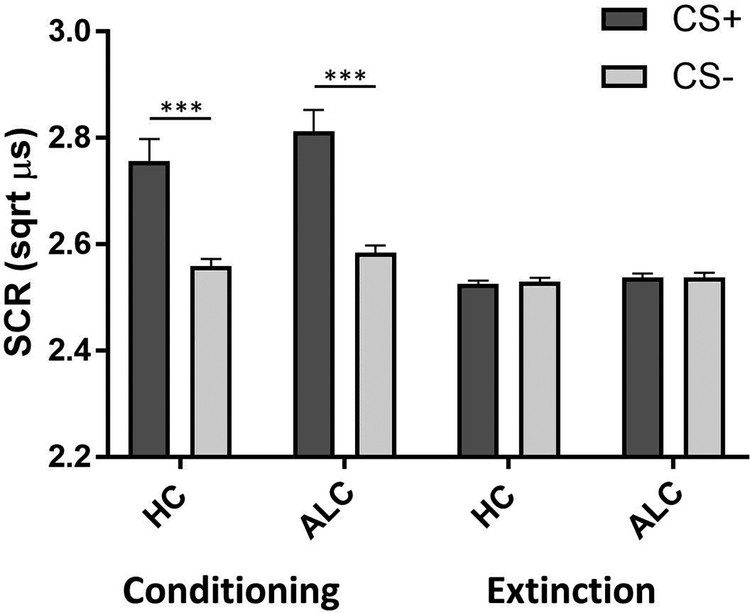

Psychophysiological data were available for 62 participants (72.1% of the total sample). All of these participants demonstrated contingency awareness46 and did not differ significantly from those without SCR data (non-responders) on any of the demographic and clinical variables in Table 1. For conditioning, analyses revealed significant main effects for stimulus (F(1,56)= 20.61, P <.001, ηp2=.27) and time (F(1,56)= 15.74, P<.001, ηp2= .22) and no significant interactions, except a trend-level stimulus × time interaction effect (F(1,56)=3.49, P=.067, ηp2=.06). There was no significant group effect (F(1,56)=1.48, P=.228). SCRs were significantly larger in CS+ compared to CS- trials (Fig. 2), indicating that fear conditioning was achieved in both ALC and HC. An ANCOVA comparing SCRs during extinction to SCRs during conditioning produced significant main effects for stimulus (F(1,55)= 21.86, P<.001, ηp2=.28) and time (F(1,55)=20.92, P<.001, ηp2=.27), as well as a stimulus × time interaction effect (F(1,55)=18.46, P<.001, ηp2=.25). There was no group effect (F(1,55)= 1.16, P=.285). These results show that CS+ SCRs were significantly lower during extinction than during conditioning, with similar SCRs to the CS+ and CS- during extinction indicating that both groups underwent successful extinction learning (Fig. 2). There were no significant effects of stimulus (F(1,55)=0.57, P=.452) or group (F(1,55)= 0.37, P=.547) for the extinction recall phase, indicating that both groups correctly recalled the extinction learning (Fig. S1). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the extinction retention index between HC (M= 93.56, SD= 21.70) and ALC (M= 94.10, SD= 14.89), U= 425, P=.592. While SCRs to the CS+ were marginally larger than to the CS- in the fear renewal phase, this difference was not statistically significant (F(1,55)=1.53, P= .221; Fig. S1), suggesting no renewal of conditioned fear responses in the conditioning context. There was no significant group effect for fear renewal (F(1,55)= 0.14, P=.715).

Figure 2.

Skin conductance responses during fear conditioning and extinction. SCR= skin conductance response; HC= healthy controls; ALC= alcohol-dependent individuals; CS+ = conditioned stimulus predicting shock; CS- = conditioned stimulus predicting no shock; ***P < .001

Neural Correlates of FCE

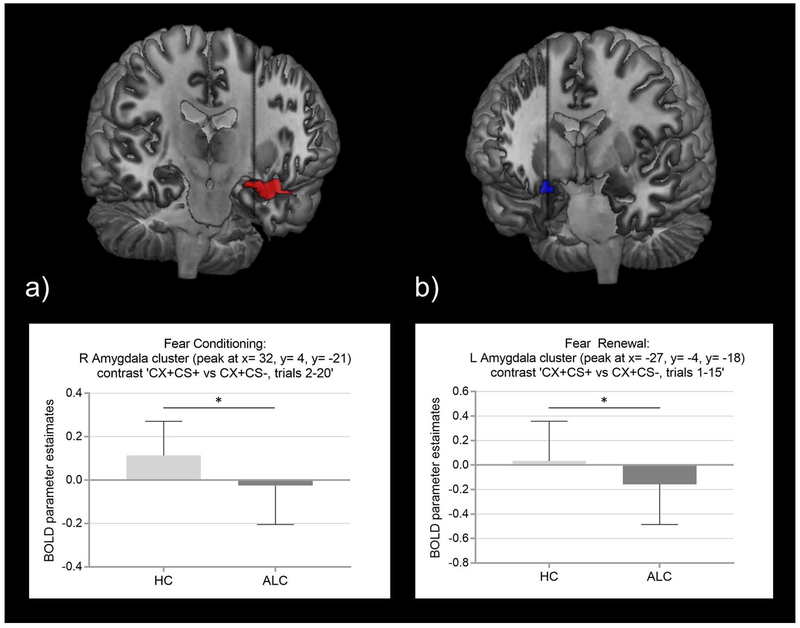

During fear conditioning, ALC and HC separately showed increased BOLD responses to ‘CS+ minus CS-’ in bilateral amygdala-ROIs and insula-ROIs (and in bilateral hippocampus-ROIs in HC; Table 2; Fig. S2), and decreased differential activations in the bilateral mPFC-ROIs (and bilateral rACC-ROIs in ALC; Table 2; Fig. S2). Additionally, both groups significantly activated across the brain the inferior frontal cingulate (BA24, 32), superior temporal gyrus (BA38), and inferior parietal lobule (BA40), as well as the lentiform nucleus as part of the globus pallidus (Table S1). HC showed decreased whole-brain BOLD responses in the medial frontal, precentral, posterior cingulate (BA31), and middle temporal gyrus (Table S1); in ALC, attenuated whole-brain activations were found in the parahippocampal and inferior parietal gyrus (BA39; Table S1). Testing for group differences during fear conditioning (‘CS+ minus CS-’), we found significantly reduced BOLD responses in the right amygdala‐ROI (MNI: 32, 4, −21; k=8, t(80)= 3.96, P(FWE)= .037, Cohen’s d= .89; Fig. 3a; Table 2) in ALC compared to HC. Testing these group differences for the ‘CS+ only’ BOLD responses showed stronger and broader group differences during fear conditioning in bilateral amygdala-ROIs (left amygdala: MNI: −30, −4, −21; k= 2, t(81)= 2.70, P(FWE)= .047, Cohen’s d= .60; right amygdala: MNI: 32, 4, −21; k= 19, t(81)= 4.01, P(FWE)= .024, Cohen’s d= .89; Table S2), and right hippocampus (MNI: 26, −7, −21; k= 35, t(81)= 3.60, P(FWE)= .042, Cohen’s d= .80; Table S2); for details, see Table S2 and S3.

Table 2.

Functional activation within the a priori Regions of Interest during fear conditioning, extinction and fear renewal (contrast ‘CS+ minus CS-’) in ALC and HC

| ROI | MNI Coordinates (x, y, z) | Cluster size (k voxels) | T | Z | Cluster P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear Conditioning (‘CS+ minus CS-’, trials 2–20) | |||||

| One-sample t-test: Increased BOLD responses in HC | |||||

| L Amygdala | −24, 0, −14 | 24 | 4.82 | 4.24 | 0.016 |

| R Amygdala | 26, 0, −14 | 39 | 6.75 | 5.46 | 0.010 |

| L Hippocampus | −24, −10, −14 | 12 | 4.54 | 4.04 | 0.087 |

| R Hippocampus | 18, −4, −14 | 21 | 5.09 | 4.43 | 0.059 |

| L Insula | −34, 24, 4 | 267 | 8.15 | 6.19 | <.001 |

| R Insula | 36, 21, 4 | 263 | 7.49 | 5.86 | <.001 |

| One-sample t-test: Decreased BOLD response in HC | |||||

| L vmPFC | −2, 52, −14 | 58 | 3.84 | 3.51 | 0.010 |

| R vmPFC | 1, 52, −14 | 28 | 3.59 | 3.32 | 0.032 |

| One-sample t-test: Increased BOLD response in ALC | |||||

| L Amygdala | −16, 0, −14 | 8 | 4.33 | 3.89 | 0.034 |

| L Insula | −48, 4, 4 | 118 | 4.98 | 4.35 | 0.005 |

| R Insula | 50, 10, −7 | 98 | 4.30 | 3.86 | 0.008 |

| One-sample t-test: Decreased BOLD response in ALC | |||||

| L rACC | −2, 28, 0 | 82 | 4.15 | 3.75 | 0.007 |

| R rACC | 4, 38, −14 | 23 | 4.20 | 3.79 | 0.045 |

| L vmPFC | −6, 56, −7 | 78 | 4.55 | 4.05 | 0.006 |

| R vmPFC | 4, 38, −14 | 107 | 4.25 | 3.83 | 0.003 |

| Two-sample t-test: HC > ALC | |||||

| R Amygdala | 32, 4, −21 | 8 | 3.96 | 3.77 | 0.037 |

| Extinction (‘CS+ minus CS-’, trials 2–15) | |||||

| One-sample t-test: Increased BOLD responses in HC | |||||

| L Insula | −30, 18, −10 | 53 | 3.86 | 3.53 | 0.025 |

| R Insula | 29, 18, −4 | 28 | 3.74 | 3.43 | 0.064 |

| Fear Renewal (‘CS+ minus CS-’, all trials 1–15) | |||||

| One-sample t-test: Increased BOLD responses in HC | |||||

| L Insula | −30, 24, 7 | 22 | 4.02 | 3.64 | 0.089 |

| One-sample t-test: Decreased BOLD response in ALC | |||||

| L Amygdala | −27, −7, −18 | 11 | 3.60 | 3.32 | 0.028 |

| R Amygdala | 26, 0, −21 | 2 | 3.10 | 2.91 | 0.060 |

| R Hippocampus | 26, −28, −7 | 10 | 3.46 | 3.20 | 0.099 |

| L vmPFC | −6, 52, −10 | 7 | 3.40 | 3.16 | 0.078 |

| Two-sample t-test: HC > ALC | |||||

| L Amygdala | −27, −4, −18 | 6 | 3.01 | 2.92 | 0.039 |

SPM‐results are reported at cluster-P < .05 FWE‐corrected for a priori ROIs. One-sample t-tests and two-sample t-tests were controlled for age, gender, and binary ELS status.

BA= Brodmann Area; CS+ = conditioned stimulus predicting shock; CS- = conditioned stimulus predicting no shock; FWE = family‐wise error; L = left; MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute; R = right; rACC = rostral anterior cingulate cortex; ROI = Region of Interest.

Figure 3.

Region of interest findings of significant functional activation group differences. Results are derived from 2-sample t-tests SVC with cluster-P < .05 FWE‐corrected for a priori ROIs comparing alcohol-dependent and healthy individuals, controlling for age, gender, and early life stress: a) Fear Conditioning (contrast CS+ versus CS-, trials 2–20): parameter estimates of reduced right amygdala-ROI BOLD responses in ALC compared to HC, Cohen’s d = .89, P(FWE) = .037; b) Fear Renewal (contrast CS+ versus CS-, all trials 1–15): reduced left amygdala-ROI BOLD responses in ALC compared to HC, Cohen’s d = .68, P(FWE) =.039. Neuroimaging findings are rendered onto the CH2better template in MRIcron (a) displayed at MNI y= 0.335322 and b) displayed at MNI y= 0.365229).

ALC= alcohol-dependent individuals; BOLD= Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent; CS+ = conditioned stimulus predicting shock; CS- = conditioned stimulus predicting no shock; HC= healthy controls; MNI= Montreal Neurologic Institute; ROI= region of interest; SVC= small volume correction; * P(FWE) < .05

For extinction and extinction recall, no significant group differences were observed. Within group analyses of fear renewal (‘CS+ minus CS-’) revealed significantly decreased BOLD responses in the left amygdala-ROI and similarly trend-wise for the right amygdala-ROI, right hippocampus-ROI and left mPFC-ROI in ALC (Table 2), while HC only displayed a trend for increased left insula-ROI activation (Table 2). However, group comparisons (‘CS+ minus CS-’) revealed blunted BOLD responses in the left amygdala-ROI (MNI: −27, −4, −18; k=6; t(78)=3.01; P(FWE)=.039, Cohen’s d= .68; Fig. 3b; Table 2) in ALC compared to HC. Similarly, HC showed stronger BOLD responses to ‘CS+ only’ compared to ALC in the left amygdala-ROI (MNI: −24, 0, −21; k= 10; t(79)= 2.99; P(FWE)=.031, Cohen’s d= .67; Table S2).

Associations with Clinical Measures

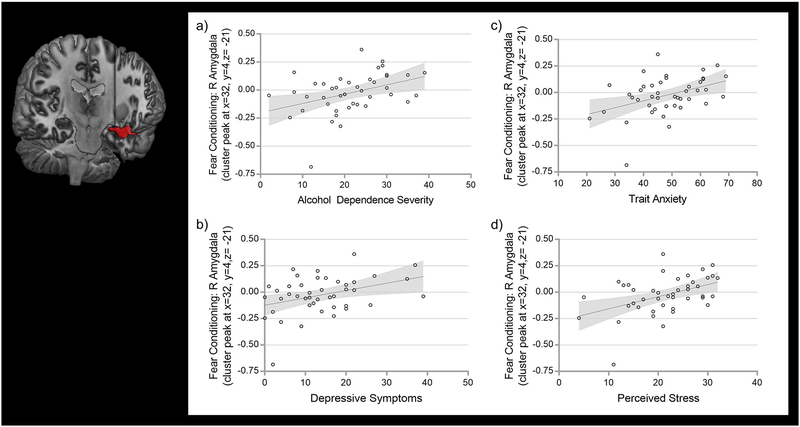

For the functional BOLD responses extracted from the group difference seen in fear conditioning (cf. Table 2), we found significant phenotype associations in the ALC group. In detail, right amygdala-ROI BOLD estimates correlated positively with alcohol dependence severity (ADS; r(43)= .39, P(Bonferroni)= .009, R2= .155; Fig. 4a), depressive symptoms (MADRS; r(43)= .37, P(Bonferroni)= .015, R2= .137; Fig. 4b), trait anxiety (STAI; r(43)= .41, P(Bonferroni)= .006, R2= .167; Fig. 4c), and perceived stress (PSS; r(43)= .45, P(Bonferroni)= .002, R2= .204; Fig. 4d). Similarly, amygdala activation was positively associated with state anxiety at admission (BSA; r(43)= .32, P= .037, R2= .102) in ALC; however, this association did not survive Bonferroni correction. Right amygdala activation was not significantly correlated with CS+ SCRs during conditioning. Individual amygdala grey matter volumes did not correlate significantly with either extracted amygdala-ROI BOLD estimates.

Figure 4.

Clinical associations found in ALC between extracted parameter estimates of right amygdala-ROI BOLD responses (identified as a significant group activation difference in fear conditioning, contrast CS+ versus CS-, trials 2–20) and a) Alcohol Dependence Severity (assessed by ADS), b) Depressive Symptoms (assessed by MADRS), c) Trait Anxiety (assessed by STAI), and d) Perceived Stress (assessed by PSS).

Neuroimaging finding of reduced functional right amygdala-ROI activations is rendered onto the CH2better template in MRIcron.

ALC= alcohol-dependent individuals; ADS= Alcohol Dependence Scale; BOLD= Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent; CS+ = conditioned stimulus predicting shock; CS- = conditioned stimulus predicting no shock; MADRS= Montgomery-Asberg Depression; PSS= Perceived Stress Scale; ROI= region of interest; STAI= Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory -Y2; SVC= small volume correction

Discussion

The present study is the first multimodal investigation of FCE in a population of ALC combining structural and functional neuroimaging, skin conductance responses, and clinical measures. The main findings include decreased limbic responses throughout fear conditioning and fear renewal in the amygdala in ALC compared to HC, indicating altered neural functioning in ALC in primary emotion-related brain areas. Furthermore, the degree of threat-related amygdala activation was strongly correlated with various clinically relevant, negative emotion-related outcomes in ALC, including trait anxiety, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress. While SCRs indexed successful fear conditioning and extinction learning in both groups, there was no blunted SCR in ALC relative to HC, indicating no deficit in skin conductance responding of individuals with ALC in fear conditioning and extinction.

Our results show, as expected, activations of limbic brain areas during fear conditioning that have major involvement in the fear neurocircuitry; namely, the amygdala and insula (among other subcortical areas outside our ROIs) in both HC and ALC, and deactivated prefrontal areas, such as the mPFC, and additionally the rACC in ALC. The critical involvement of both the amygdala and the PFC (including the rACC) is well-described in the field of fear conditioning, as well as in alcohol addiction research.8,27,47–49 These key regions interact in the cortical top-down regulation of limbic reward and emotion processing. Specifically, increased amygdala responses elicited by perceived threat cues are down-regulated by the PFC’s evaluation of the actual risk of the situational danger.50–52 Interestingly, in our study, amygdala responses during fear conditioning and fear renewal were significantly decreased in ALC compared to HC, indicating blunted, presumably impaired, amygdala functioning when ALC were confronted with personal threat. Here, additional analyses of separate ‘CS+ only’ and ‘CS- only’ brain responses identified and thus support the notion that the perception of personal danger (i.e., CS+ shock cues) elicits the pronounced amygdala group differences found in ALC compared to HC. This finding is in line with previous research, including a prior study that investigated aversive learning using an FCE paradigm in healthy carriers of a risk variant for ALC (rs20722450) and found reduced right amygdala activation during fear conditioning in risk variant carriers compared to controls.31 Another study examined emotional changes associated with ALC and found reduced amygdala activation during an emotional face processing task in long-term abstinent alcoholics compared to matched controls.26 Finally, our findings are consistent with studies that found blunted amygdala responses in individuals at high risk for alcohol dependence during different emotion processing tasks.32,53,54

However, our data contrast findings from FCE paradigms in anxiety disorders, which generally show amygdala hyperactivation to threat.15,16 Our finding indicates that functional alterations in individuals with ALC may differ from those in individuals with anxiety disorders. Furthermore, it should be noted that at first the positive correlation between right amygdala activation during conditioning and our clinical measures appears paradoxical as it indicates that alcohol-dependent individuals with higher amygdala activation, which is closer to the activation pattern shown by the HC, have greater levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, stress, and alcohol dependence severity. However, there are several possible explanations for this finding.

First, repeated cycles of intoxication (i.e., relapse) and detoxification (i.e., withdrawal, characterized by the development of negative affective states) may lead to an overall downregulation of amygdala reactivity. As a result, individuals with ALC relative to controls may start out with a decreased level of amygdala activation where threat-induced activation is positively associated with measures of negative affect, such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, and stress. This interpretation is in line with previous translational research that found impairments of fear conditioning in human binge drinkers, as well as impaired fear conditioning and reduced long-term potentiation in the amygdala in rodent models of repeated alcohol exposure and withdrawal.29

Second, given the correlational nature of our study, it is unclear whether increased negative affect levels (i.e., anxiety, depressive symptoms, stress) were a precursor or a consequence of alcohol use. It is possible that ALC had pre-existing symptoms of negative affect that drove increases in amygdala reactivity, which they may have sought to counter by self-medicating with alcohol. As a consequence, they may have reduced their amygdala reactivity but also developed dependence. This interpretation is consistent with previous reports of blunted amygdala reactivity in individuals at risk for alcohol dependence,31,32 and further supported by the positive correlation between amygdala activation and alcohol dependence severity, which might indicate that the efficacy of the self-medication correlates with the severity of dependence, such that higher doses of alcohol were needed to achieve the desired effect.

Third, another possible explanation may be direct neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the fear neurocircuitry. Animal models have shown frontal cortex neuronal cell loss following alcohol exposure and subsequent abnormal fear learning.12 However, our exploratory analyses did not find a direct association between structural amygdala grey matter volumes and amygdala hypoactivation during fear conditioning and renewal. Thus, our findings favor the explanation of functional alterations in ALC compared to HC when active differentiation and adequate processing of threat versus non-threat cues is required in the context of personal danger. This adds to previous reports in ALC that have shown mixed amygdala findings during emotion and threat processing.23,24,26 Given the importance of amygdala activation to threat for normal aversive learning, individuals with ALC might have abnormal fear learning and subsequently diminished sensitivity to negative consequences of alcohol use, which may contribute to disease progression and relapse risk.32,54

Noteworthy, contrary to prior FCE studies in PTSD and anxiety disorders, there were no significant group differences during extinction recall, indicating that our ALC cohort seemed to have no difficulties with correctly recalling the extinction memory in a safe context. FCE studies in individuals suffering from anxiety disorders, PTSD, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have reported decreased activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), ACC, and insula, indicating deficits in extinction memory recall.9–11,16 Furthermore, decreased functional vmPFC responses were shown to be positively associated with anxiety and OCD symptom severity.10,11 However, the lack of an observed group difference in the present study is consistent with the clinical phenotype of our sample. One core characteristic of AUD is generally described as an indifference towards non-substance-related (neutral) cues and contexts (i.e., the safe environment in the extinction recall phase), which would explain why we did not see the extinction recall deficit typically observed in disorders, such as anxiety disorder, OCD, or PTSD, where a lack of correctly learning and retrieving contextual information is a main issue.

Confirming our hypothesis, larger SCRs to CS+ compared to CS- trials in the conditioning phase demonstrated that all individuals successfully learned to distinguish between the CS+ and CS-, thereby confirming that differential conditioning occurred; furthermore, similar SCRs to the CS+ and CS- during extinction indexed that extinction learning occurred. Contrary to our hypothesis, there were no significant group differences in SCRs during conditioning. While this finding contradicts two previous psychophysiological studies in individuals at risk for the development of ALC,29,30 it is largely consistent with prior findings of FCE neuroimaging studies in individuals with anxiety disorders and PTSD,9,10 as well as a previous SCR study in ALC.55 It has been proposed that BOLD responses and SCR might not represent the same aspects of FCE processes and that neural differences might be detected independently.22 However, since this is the first study combining neuroimaging and SCR in ALC, future studies are needed to replicate these findings.

Limitations

The following limitations should be carefully considered. First, the ALC group differed significantly from the healthy control group. While we controlled for age, gender, and ELS status, we did not control for smoking despite the detected group difference. Future studies investigating FCE in ALC might recruit a balanced sample of smoking/non-smoking HC and ALC or, alternatively, control for severity of nicotine dependence to account for potentially confounding substance-induced functional and structural brain changes. Since 1) all our HC were non-smokers and therefore lacking variability in the FTND score, and 2) no significant associations were found with the extracted amygdala BOLD responses, we did not include smoking as a covariate. Further, subtle differences in psychiatric comorbidities, such as mood and anxiety disorders, should be considered as potential confounds. However, since prior research shows amygdala hyperactivation in anxiety disorders and PTSD, this is unlikely. Nevertheless, given the complex and heterogenous phenotypic nature of AUD commonly seen in treatment environments, future studies balanced for comorbid disorders might use the FCE paradigm to disentangle the shared pathophysiology of AUD and anxiety/mood disorders. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that alcohol directly impacts structural brain integrity, including various grey matter atrophies and white matter anomalies, which could have affected functional activation during the FCE paradigm. However, individuals reporting previous brain injuries, or loss of consciousness were excluded from study participation and we did not observe any relationship between structural grey matter volumes and functional BOLD findings within our amygdala-ROIs; therefore, it is unlikely that structural anomalies were a confounding factor. Additional predisposing (epi-)genetic, environmental, and structural factors may also affect fear learning in ALC and should be considered in future research.7,31,56 Finally, although we detected significant medium-large effect sized BOLD group differences in the amygdala (Cohen’s d=.60-.89), the present study with n=43 per group and an FWE-corrected alpha of 0.05 might lack power to detect potential other BOLD differences between ALC and HC; future studies might therefore include larger samples and/or consider less conservative alpha-error adjustments for ROI analyses (e.g., false discovery rate correction). Future neuroimaging studies might consider other atlases for ROI definition, such as probability-based atlases or neurovault peaks (https://neurovault.org/).

Conclusions

For the first time investigating fear conditioning and extinction in AUD by combining both functional and structural neuroimaging, as well as psychophysiological data and clinical measures, our main results show significantly blunted functional amygdala BOLD responses as a core region within the emotional brain circuit in ALC compared to HC. Furthermore, we detected significant endophenotypic correlations, indicating that reduced functional amygdaloid reactivity in fear conditioning is associated with a clinical ALC phenotype of increased negative emotions. These findings encourage future use of the FCE paradigm in ALC populations to further investigate dysregulations in fear neurocircuitry. Improving our understanding of the structures mediating negative affect regulation during early abstinence might inform the development of novel treatment approaches for alcohol dependence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) intramural funding [ZIA-AA000242; Section on Clinical Genomics and Experimental Therapeutics; to FWL; Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)]. Dr. Charlet acknowledges funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG CH1936/1–1). We thank Monte Phillips, Jisoo Lee, Jeesun Jung, Audrey Luo, Daniel B. Rosoff, Martha Longley, Jill Sorcher, Allison Rosen, Kelsey Mauro, Mike Kerich, Vijay Ramchandani, Lorenzo Leggio and staff of the Office of the Clinical Director at NIAAA for support during the study.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gonzales K, Roeber J, Kanny D, et al. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost−-11 States, 2006–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(10):213–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradizza CM, Brown WC, Ruszczyk MU, Dermen KH, Lucke JF, Stasiewicz PR. Difficulties in emotion regulation in treatment-seeking alcoholics with and without co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders. Addict Behav. 2018;80:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berking M, Margraf M, Ebert D, Wupperman P, Hofmann SG, Junghanns K. Deficits in emotion-regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive–behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(3):307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai HM, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, Hunt GE. Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilpin NW, Herman MA, Roberto M. The central amygdala as an integrative hub for anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(10):859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephens MA, Wand G. Stress and the HPA axis: role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. 2012;34(4):468–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo LM, Asratian A, Linde J, et al. Protective effects of elevated anandamide on stress and fear-related behaviors: translational evidence from humans and mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bremner JD, Vermetten E, Schmahl C, et al. Positron emission tomographic imaging of neural correlates of a fear acquisition and extinction paradigm in women with childhood sexual-abuse-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):791–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rougemont-Bucking A, Linnman C, Zeffiro TA, et al. Altered processing of contextual information during fear extinction in PTSD: an fMRI study. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(4):227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin M-F, Zsido RG, Song H, et al. Skin Conductance Responses and Neural Activations During Fear Conditioning and Extinction Recall Across Anxiety Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milad MR, Furtak SC, Greenberg JL, et al. Deficits in conditioned fear extinction in obsessive-compulsive disorder and neurobiological changes in the fear circuit. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(6):608–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes A, Fitzgerald PJ, MacPherson KP, et al. Chronic alcohol remodels prefrontal neurons and disrupts NMDAR-mediated fear extinction encoding. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(10):1359–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephens DN, Brown G, Duka T, Ripley TL. Impaired fear conditioning but enhanced seizure sensitivity in rats given repeated experience of withdrawal from alcohol. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(12):2023–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: ten years of progress. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:129–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garfinkel SN, Abelson JL, King AP, et al. Impaired contextual modulation of memories in PTSD: an fMRI and psychophysiological study of extinction retention and fear renewal. J Neurosci. 2014;34(40):13435–13443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milad MR, Pitman RK, Ellis CB, et al. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1075–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milad MR, Wright CI, Orr SP, Pitman RK, Quirk GJ, Rauch SL. Recall of fear extinction in humans activates the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in concert. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, LeDoux JE. Extinction learning in humans: role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron. 2004;43(6):897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sehlmeyer C, Schoning S, Zwitserlood P, et al. Human fear conditioning and extinction in neuroimaging: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fullana M, Harrison B, Soriano-Mas C, et al. Neural signatures of human fear conditioning: an updated and extended meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(4):500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milad MR, Quirk GJ, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Fischl B, Rauch SL. A role for the human dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in fear expression. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1191–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konova AB, Parvaz MA, Bernstein V, et al. Neural mechanisms of extinguishing drug and pleasant cue associations in human addiction: role of the VMPFC. Addict Biol. 2019;24(1):88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlet K, Schlagenhauf F, Richter A, et al. Neural activation during processing of aversive faces predicts treatment outcome in alcoholism. Addict Biol. 2014;19(3):439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salloum JB, Ramchandani VA, Bodurka J, et al. Blunted rostral anterior cingulate response during a simplified decoding task of negative emotional facial expressions in alcoholic patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(9):1490–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlet K, Beck A, Jorde A, et al. Increased neural activity during high working memory load predicts low relapse risk in alcohol dependence. Addict Biol. 2014;19(3):402–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marinkovic K, Oscar-Berman M, Urban T, et al. Alcoholism and dampened temporal limbic activation to emotional faces. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(11):1880–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grusser SM, Wrase J, Klein S, et al. Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;175(3):296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens DN, Ripley TL, Borlikova G, et al. Repeated ethanol exposure and withdrawal impairs human fear conditioning and depresses long-term potentiation in rat amygdala and hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(5):392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finn PR, Kessler DN, Hussong AM. Risk for alcoholism and classical conditioning to signals for punishment: Evidence for a weak behavioral inhibition system. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(2):293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cacciaglia R, Nees F, Pohlack ST, et al. A risk variant for alcoholism in the NMDA receptor affects amygdala activity during fear conditioning in humans. Biol Psychol. 2013;94(1):74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PTJBp. Reduced amygdala activation in young adults at high risk of alcoholism: studies from the Oklahoma family health patterns project. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(11):1306–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heilig M, Sommer WH, Spanagel R. The Need for Treatment Responsive Translational Biomarkers in Alcoholism Research. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;28:151–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobell LC, Sobell MB Timeline Followback User’s Guide: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA‐Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, & Lushene RE The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skinner H, Horn J. Alcohol Dependence Scale: User’s Guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(8):1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazaika PK, Whitfield S, Cooper JCJN. Detection and repair of transient artifacts in fMRI data. Neuroimage. 2005;26(Suppl 1):S36. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JHJN. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19(3):1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grillon C Associative learning deficits increase symptoms of anxiety in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(11):851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phelps EA, O’Connor KJ, Gatenby JC, Gore JC, Grillon C, Davis M. Activation of the left amygdala to a cognitive representation of fear. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(4):437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alvarez RP, Biggs A, Chen G, Pine DS, Grillon C. Contextual fear conditioning in humans: cortical-hippocampal and amygdala contributions. J Neurosci. 2008;28(24):6211–6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peters J, Kalivas PW, Quirk GJ. Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 2009;16(5):279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the’dark side’of drug addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1442–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kienast T, Schlagenhauf F, Rapp MA, et al. Dopamine-modulated aversive emotion processing fails in alcohol-dependent patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46(4):130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT, Yau WY, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA. Affective circuitry and risk for alcoholism in late adolescence: differences in frontostriatal responses between vulnerable and resilient children of alcoholic parents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(3):414–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nikolova YS, Hariri AR. Neural responses to threat and reward interact to predict stress-related problem drinking: A novel protective role of the amygdala. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finn PR, Justus AN, Mazas C, Rorick L, Steinmetz JE. Constraint, alcoholism, and electrodermal response in aversive classical conditioning and mismatch novelty paradigms. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2001;36(2):154–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whelan R, Watts R, Orr CA, et al. Neuropsychosocial profiles of current and future adolescent alcohol misusers. Nature. 2014;512(7513):185–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.