Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in the widespread implementation of social distancing measures. Adhering to social distancing may be particularly challenging for adolescents, for whom interaction with peers is especially important. We argue that young people’s capacity to encourage each other to observe social distancing rules should be harnessed.

Keywords: COVID-19, peer influence, adolescence, public health

Introduction

On 12 March 2020, the World Health Organization announced that COVID-19 was a global pandemic. In response to this, governments worldwide have implemented a number of measures to curtail the spread of the disease. These include closing sites of public recreation and education, such as schools and universities, and limiting face-to-face interactions through enforced ‘social distancing’. This will, for the vast majority of the world’s population, be an unprecedented experience in which the protection of the most vulnerable depends on strict adherence to the new measures. While many people are adhering to guidelines, some are not. In particular, it is proving a challenge to convince some young people to refrain from physically meeting with friends and taking part in gatherings. For example, this was clearly demonstrated in reports of US students gathering in large groups during their spring break (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/mar/28/americans-who-dont-take-coronavirus-seriously).

Adolescence, the period of life between ages 10 and 24 years, is often associated with increased risk taking, an increased need for social connection and peer acceptance, and a heightened sensitivity to peer influence. These factors mean that adherence to social distancing rules may be especially challenging for young people. Breaking social distancing rules is a risk-taking behaviour: it is a risk to one’s own health and the health of others and may carry legal or financial consequences. Here, we discuss evidence demonstrating the effect of peer influence on adolescent risk behaviours and how this phenomenon could be harnessed in a positive way to encourage young people to follow social distancing measures.

Peer Influence on Adolescent Behaviour

The presence of peers increases the likelihood that adolescents will take certain risks. For example, evidence from laboratory studies and real-world data show that, when driving, adolescents are more likely to have an accident when there is a passenger in the car, while adults are not [1,2]. Policy changes have been made to mitigate the risk associated with young drivers carrying passengers. For example, in the Canadian state of British Columbia, drivers from the age of 17 years are restricted to driving with only one passenger, unless they are carrying immediate family members or a full licence holder over the age of 25 years, for a minimum of 2 years.

In the presence of peers, adolescents are also more likely to experiment with drugs, alcohol, or cigarettes than when alone, and having friends who smoke or drink is one of the biggest predictors of adolescent engagement in these behaviours [3]. This social influence is also seen online [4]. For example, adolescents (aged 14–17 years) are more likely to post sexual content online if their peers have done so. The speed and extent of peer influence is likely to be amplified online due to the wide reach and fast-acting nature of social media.

Adolescent social influence does not always have negative consequences. Young people are also less likely to engage in a risky behaviour if a friend discourages them from doing so [5]. Adolescents are more socially influenced than adults to engage in (hypothetical) prosocial behaviours [6] and more likely to volunteer in the community if they are told that their peers volunteer [7]. Young people aged 12–16 years give more generously in an experimental public goods game when they observe peers being generous [8].

Adolescents are particularly susceptible to peer influence for several reasons. First, adolescents look to their peers to understand social norms. They align their behaviour over time with the norms of their group or the group they want to belong to – a process known as peer socialisation [9]. Second, adolescents may find it particularly rewarding to gain social status, a potential outcome of aligning with peers [10]. Finally, adolescents tend to be hypersensitive to the negative effects of social exclusion. They may conform to a group norm (which sometimes means taking a risk) to avoid this unpleasant social outcome. The desire to avoid the social risk of being ostracised or left behind might outweigh the potential negative consequences associated with health risk or illegal behaviours [11].

This susceptibility to peer influence – both negative and positive – has important implications for the behaviour of adolescents in the current crisis. In the context of social distancing measures, if an adolescent’s friends break these rules and meet face-to-face, she may feel more inclined to do so herself. By breaking the rules, her friends have established a group norm, whereby meeting up is seen as acceptable. Fear of exclusion is also important: she may want to join because she misses her friends, but she may also feel a pressure to do so to reduce the social risk of being rejected. [11]. By the same token, in the current crisis, adolescents may also influence each other in a positive way. As discussed earlier, peers can influence adolescents to behave more prosocially, and social norms can be changed [12]. This can be harnessed when communicating social distancing rules between young people.

Shifting Social Norms among Adolescents

Interventions and campaigns aimed at influencing adolescent behaviour are often unsuccessful [13]. Many of these interventions are based on the theory that increasing adolescents’ knowledge and awareness of certain health risks will result in positive changes to behaviour. However, as Yaeger and colleagues argue, these traditional interventions, which are predominantly adult led, are often unsuccessful. A metanalysis of bullying interventions found that prevention efforts were often successful below the 7th grade (aged under 13 years), but not beyond 8th grade (over 13 years of age) [14]. Interventions aimed at adolescents are most likely to result in behaviour change when they afford adolescents respect and autonomy and account for what they value [13].

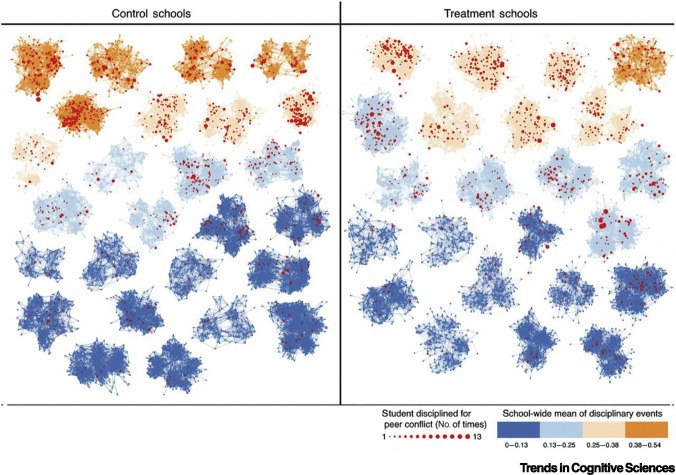

In the current pandemic, the campaigns to impose social distancing have been led by the government and are likely to be enforced by other adults (e.g., parents, teachers, police). One possible approach to enhance their effectiveness would be to provide adolescents with the autonomy to develop and deliver their own campaigns, with a focus on changing peer attitudes around the importance of social distancing. This process was successfully demonstrated by a study that utilised a peer-led approach to reduce rates of peer victimisation in schools. In this study, social network analysis was used to find highly connected, well-liked students (aged 11–15 years), who were then selected to develop their own antibullying campaigns among peers. Over the ensuing year there was a 25% reduction in victimisation rates in these schools compared with control schools. The effect was stronger when more well-liked students led the campaign ([12]; Figure 1 ). Similar successes have been observed for adolescent-led intervention programs aiming to reduce smoking, drugs, and alcohol, compared with controls [15].

Figure 1.

Reduced Bullying Rates Following a Peer-Led Intervention.

The distribution of disciplinary events in control schools and treatment schools (who received the peer-led intervention), taken from [12]. The average number of times each student was disciplined for peer conflict is shown from dark blue (little conflict) to dark orange (high conflict). There is a higher concentration of dark-orange events (high conflict) in the control schools. Red nodes are representative of students disciplined for conflict and are scaled to the number of times they were disciplined across the school year.

Given the current restrictions on face-to-face interactions, social media is likely to be the most effective way to promote social distancing behaviours among adolescents. Young people might post content online about how they are following the rules; for example, by sharing a photo or video of themselves at home. On platforms such as Instagram, they can add social distancing tags (phrases and images) to these posts. These will then be seen by their peers, who may add endorsements, such as comments and likes, which increase the visibility of the post. As more adolescents see this content, social distancing can be established as a group norm among friends. This behaviour will then be modelled by those looking on, who may go on to post similar content themselves. One advantage of this approach is that it is adolescent led and autonomous: the way in which young people manage social distancing, and their motivation for doing so, will stem naturally from the young people themselves.

Public health bodies should consider targeting, and even incentivising, influential individuals online (i.e., those who have the capacity to diffuse information among a large online social network). For example, it may be particularly useful to target social media ‘influencers’, individuals with a strong online presence and a large number of adolescent followers. If these individuals model positive social distancing behaviour and communicate the risk of COVID-19 through their platform, adolescents may listen. An advantage of targeting social media influencers is that they exist across a number of domains of interest (e.g., different hobbies) and so are likely to be able to target large disparate groups of young people.

Concluding Remarks

Although the coronavirus appears to pose a low risk to adolescents themselves, their willingness to follow social distancing guidelines is essential to reduce the risk for other people. Adolescent susceptibility to peer influence can be beneficial and should be harnessed by public-health campaigns to increase social distancing. We propose that adolescents themselves have a great capacity to influence each other to change norms and peer expectations towards public-health goals. Especially important in creating change is the need to provide young people with the capacity to lead and enact their own ideas within their social networks. Asking adolescents to stay away from their friends at a key developmental period is a considerable challenge, but can be achieved by taking advantage of adolescent social influence.

Acknowledgments

S-J.B. is funded by Wellcome, the Jacobs Foundation, Switzerland, UKRI-GCRF, and the University of Cambridge. J.L.A. is funded by the MRC.

References

- 1.Chen L.H. Carrying passengers as a risk factor for crashes fatal to 16- and 17-year-old drivers. JAMA. 2000;283:1578–1582. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner M., Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Dev. Psychol. 2005;41:625. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loke A.Y., Mak Y.W. Family process and peer influences on substance use by adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10:3868–3885. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10093868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesi J. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: part 2 – application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018;21:295–319. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell K.A. Friends: the role of peer influence across adolescent risk behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002;31:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foulkes L. Age differences in the prosocial influence effect. Dev. Sci. 2018;21 doi: 10.1111/desc.12666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choukas-Bradley S. Peer influence, peer status, and prosocial behavior: an experimental investigation of peer socialization of adolescents’ intentions to volunteer. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015;44:2197–2210. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Hoorn J. Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016;26:90–100. doi: 10.1111/jora.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henneberger A.K. Peer influence and adolescent substance use: a systematic review of dynamic social network research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40894-019-00130-0. Published online January 2, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brechwald W.A., Prinstein M.J. Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011;21:166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blakemore S.J. Avoiding social risk in adolescence. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018;27:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paluck E.L. Changing climates of conflict: a social network experiment in 56 schools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:566–571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514483113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeager D.S. Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018;13:101–122. doi: 10.1177/1745691617722620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeager D.S. Declines in efficacy of anti-bullying programs among older adolescents: theory and a three-level meta-analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015;37:36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacArthur G.J. Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11–21 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;111:391–407. doi: 10.1111/add.13224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]