Abstract

BACKGROUND

Both end-stage renal disease and being wait-listed for a kidney transplant are anxiety-causing situations. Wait-listed patients usually require arteriovenous fistula surgery for dialysis access. This procedure is performed under local anesthesia. We investigated the effects of music on the anxiety, perceived pain and satisfaction levels of patients who underwent fistula surgery.

AIM

To investigate the effect of music therapy on anxiety levels and perceived pain of patients undergoing fistula surgery.

METHODS

Patients who were on a waiting list for kidney transplants and scheduled for fistula surgery were randomized to control and music groups. The music group patients listened to music throughout the fistula surgery. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was performed to assess anxiety, additionally visual analog scale was used to evaluate perceived pain, willingness to repeat the procedure and patient satisfaction. Demographic features, comorbidities, surgical history, basic surgical data (location of fistula creation, duration of surgery, incision length) and intra-operative hemodynamic parameters were recorded by an investigator blinded to the study group. An additional trait anxiety assessment was performed following the surgery.

RESULTS

There was a total of 55 patients included in the study. However, 14 patients did not fulfill the criteria due to requirement of sedation during surgery or uncompleted questionnaires. The remaining 41 patients were included in the analysis. There were 26 males and 15 females. The control and music groups consisted of 20 and 21 patients, respectively. With regard to basic surgical and demographic data, there was no difference between the groups. Overall patient satisfaction was significantly higher and intra-operative heart rate and blood pressure were significantly lower in the music group (P < 0.05). Postoperative state anxiety levels were significantly lower in the music group.

CONCLUSION

Music therapy can be a complimentary treatment for patients undergoing fistula surgery. It can reduce anxiety and perceived pain, improve intraoperative hemodynamic parameters and enhance treatment satisfaction, thus may contribute to better compliance of the patients.

Keywords: Music, Music therapy, Anxiety, Arteriovenous fistula, Kidney transplant, Waitlist, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Dialysis access, End-stage kidney disease

Core tip: Being successful in managing patients undergoing kidney transplantation goes beyond passing on best medical advice and performing operations with cutting edge technology. It requires building rapport and informing them about the procedures awaiting, like transplantation and arteriovenous fistula creation. However, having to go through these procedures may cause anxiety and feeling powerless. One of our important duty as a physician should be to keep our patients on task and help them manage their anxiety. This article conceptualizes music therapy as an effective tool to relieve patient anxiety during fistula creation surgery by providing randomized, single-blind clinical trial data.

INTRODUCTION

The number of patients suffering from end-stage kidney disease (ESRD) is increasing. While the best treatment for ESRD is transplantation, the shortage of organs remains a huge barrier[1]. Patients must remain on dialysis while waiting for an available kidney for transplantation. Of the two main types of dialysis, hemodialysis is the most prevalent method[2,3]. There are several types of vascular accesses for hemodialysis: Temporary dialysis catheters, permanent tunneled catheters, arteriovenous fistulas and shunts. The selection of a specific type depends on clinical urgency, the state of the patient’s veins and arteries, the main diagnosis, comorbidities as well as the patient’s anxiety level.

Being diagnosed with ESRD and wait-listed for a kidney transplant are both anxiety-causing situations[4-8]. Additionally, a diagnosis of ESRD indicates the need for a vascular access in the short run. The preferred vascular access for patients requiring dialysis is arteriovenous fistula creation, as they are associated with high long-term patency and low complication rates[9]. Native vessels are used in arteriovenous fistula creation. Specifically, an anastomosis is performed between the native artery and the vein to obtain increased blood flow and pressure required for hemodialysis.

However, due to anxiety, some patients may delay or fail to comply with required therapeutic interventions, such as arteriovenous fistula creation surgery. Although the majority of these surgeries can be performed under local anesthesia, primary failure rates are relatively high and are reported to be up to 37% in some series[9]. In the event of failure, a second surgery should be planned in coordination with the patient’s nephrologist. Undoubtedly, this second attempt will lead to more anxiety in the patient, especially if the first experience was stressful.

It is necessary to reduce patient anxiety in order to promote compliance, decrease complication rates and improve outcomes. One of the methods used to reduce anxiety is music therapy[10]. Music therapy is a cheap and easy method that has been shown to increase the stress threshold and eliminate negative emotions by adjusting internal processes and promoting relaxation. Music therapy has also been found to reduce postoperative pain and analgesia use and increase patient satisfaction[11]. This study aims to investigate the effects of music on anxiety levels and physiological responses, including blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation, in patients undergoing arteriovenous fistula surgeries. Additionally, the effects of music on postsurgical pain, analgesic requirements and the patient’s willingness to repeat the procedure are assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This prospective randomized, single-blind study was conducted in the preoperative area, operating theater and postoperative recovery area of the Department of Urology and Transplantation in Diskapi Research and Training Hospital over a six-month period (from September 1, 2018 to February 28, 2019). Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained.

Patients older than 18 years of age who were on a waiting list for kidney transplant, scheduled for fistula surgery and agreed to sign the informed consent form were included. Exclusion criteria were previously diagnosed cognitive or psychiatric disorders, impaired hearing and chronic treatment with analgesics. Patients with a past history of fistula creation surgery were also excluded from the study. All patients who underwent fistula surgery received local anesthesia, only two patients who required sedation during the surgery were also excluded from the study.

Computer-based randomization software was used to assign the patients into two study groups: The study group and the control group. Members of the study group listened to their music of choice via a headset during the arteriovenous fistula creation surgery. Patients in the control group put on a headset with no music and were therefore naturally exposed to the sounds in the operating theater without any isolation.

As soon as the patients arrived in the preoperative area, one physician introduced the study and obtained signed consent forms from the patients (SC). Use of antihypertensive treatments, anticoagulants and beta blockers was recorded. Same researcher noted the group patient was involved in and the patients’ music preferences. After completion of preoperative data sheets, including social and demographic parameters as well as the anxiety assessment, patients were sent to the operating room for arteriovenous fistula creation surgery under local anesthesia.

In the operating room, all patients were monitored via electrocardiogram, blood pressure and pulse oximetry measurements. Patients in the study group were given a headphone attached to an MP3 player with three different types of music samples: Folk, pop and Sufi music. Patient choice of music was respected in all cases. The music was started immediately after the patient was monitored and positioned for the surgery and was maintained until the end of surgery. The control group received no music and was exposed to operating room noise.

During the operation, the duration of the procedure, location of fistula creation, incision length, estimated blood loss and amount of local anesthetic used for infiltration were recorded.

Hemodynamic parameters

Data related to surgery (type of arteriovenous fistula, duration of surgery, amount of local anesthetic used as well as estimated blood loss) and hemodynamic parameters at the initiation of the procedure (heart rate, systolic, diastolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate) were recorded. After surgery, all patients were transferred to the postoperative recovery area. For both groups, hemodynamic parameters were collected again while the patient was in a supine position. This step was followed by an anxiety assessment in addition to a measurement of pain and willingness to repeat the procedure using a visual analog scale (VAS).

Anxiety assessment

Patient anxiety assessment was performed using the validated Turkish version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). This inventory is an individual documentation of anxiety status scored by the patient[12]. It includes two sets of questions to determine the situational (state) and baseline (trait) anxiety. The state component determines the anxiety level at the intervention time, while the trait component determines the anxiety level in general. The STAI scores were calculated based on individual patient responses. In this inventory, the scores align between 20 to 80. The higher scores indicated higher anxiety levels. Patients who could not fill out the assessments were assisted by a researcher blinded to the study groups.

VAS assessments for pain and willingness to repeat the procedure

A VAS consisting of a 10-centimeter horizontal line, anchored evenly by numbers from 0 to 10, was used to assess the patient’s pain and willingness to repeat the procedure. The number 0 was identical to having no pain while the number 10 corresponded to maximal pain that can be experienced by the patient. Willingness to repeat the procedure was assessed in a similar way, where 0 corresponded to never willing to repeat the surgery and 10 to willingness to repeat the surgery if the attempt failed to create a functional arteriovenous fistula. Additionally, the need for analgesia was also reported.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). Whether the distributions of the continuous variables were normal or not was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Levene test was used to evaluate the homogeneity of the variances. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (min–max), where applicable. The number of cases and percentages were used as categorical data. The mean differences between groups were compared using the Student’s t-test, while the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for non-normally distributed data. The statistical significance of the differences between pre- and postop hemodynamic measurements within each group were evaluated with a Paired t-test. The Wilcoxon Sign Rank test was applied for comparisons between pre- and postop STAI-T levels. Categorical data were analyzed using the Continuity Corrected Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Statistical significance was confirmed with a P value less than 0.05. However, in all multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni Correction was used to control Type I errors.

RESULTS

There was a total of 55 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. However, patients who could not fill out the forms correctly and those who required sedation or laryngeal mask anesthesia to tolerate the surgery were excluded from the study (n = 14). The remaining 41 patients included 26 males and 15 females. The mean patient age was 57.1 (± 16.9) in the control group compared to 56.6 (± 14.1) in the study group (P = 0.930) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographical and clinical characteristics

| Control group | Study group | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 57.1 ± 16.9 | 56.6 ± 14.1 | 0.930 |

| Gender | > 0.999 | ||

| Male | 13 (65.0%) | 13 (61.9%) | |

| Female | 7 (35.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | |

| Education level | 0.670 | ||

| Illiterate | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (19.1%) | |

| Literate | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (19.1%) | |

| Primary | 4 (20.0%) | 7 (33.3%) | |

| Secondary | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| High | 4 (20.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| University | 3 (15.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| Marital status | 0.651 | ||

| Married | 10 (50.0%) | 13 (61.9%) | |

| Others | 10 (50.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | |

| Weight (kg) | 76.4 ± 12.4 | 79.8 ± 14.4 | 0.423 |

| Height (cm) | 163.6 ± 7.7 | 164.7 ± 9.1 | 0.689 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 4.6 | 29.6 ± 5.7 | 0.554 |

| Presence of a dialysis catheter | 14 (70.0%) | 14 (66.7%) | > 0.999 |

| Received hemodialysis prior | 15 (75.0%) | 14 (66.7%) | 0.808 |

| Any family members with ESRD | 4 (20.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0.697 |

| Duration of diagnosis | 19.5 (2.0-70.0) | 17.0 (1.5-60.0) | 0.403 |

ESRD: End-stage kidney disease.

Demographical data are shown in Table 1, including age, gender, education level, marital status, weight, height, body mass index, presence of a dialysis catheter, prior hemodialysis treatment, family history with c and time since diagnosis. Analysis of these variables revealed no differences between the two groups.

The causes of ESRD were variable in both groups. The most frequent diagnoses were type II diabetes and hypertension, which is a finding in line with the literature. Glomerulonephritis constituted the second most common cause of ESRD, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency distributions for the reasons of end-stage kidney disease diagnosis

| Control group | Study group | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Diabetes and HTN | 7 | 35.0 | 5 | 23.8 |

| Type II DM | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 9.5 |

| Acute kidney failure | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| HTN | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Type 1 DM | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Alport’s diesese | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Alport’s disease | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Amyloidosis | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Drug toxicity | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Dysplastic kidney, HTN | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| FSGS | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Kidney stones | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| MPGN | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Prostate Tm, HTN, DM | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Renal cell Ca+ dysplastic kidney | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Urethral stricture | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 20 | 100.0 | 21 | 100.0 |

HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; FSGS: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; MPGN: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

The patient’s previous surgical histories were also recorded, as they could have an effect on anxiety. The two patient groups were comparable in terms of their previous surgical histories. Thirteen patients in the control group and 14 patients in the study group had undergone a previous surgery. The frequency distributions of previous surgeries are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency distributions for any other surgical intervention history

| Control group | Study group | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| None | 7 | 35.0 | 7 | 33.3 |

| TAH-BSO | 1 | 5.0 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| TUR-P | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Appendectomy | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Cholecystectomy | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Cystoscopy | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Glaucoma surgery | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Hip replacement | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Kidney biopsy | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Appendectomy | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Kidney biopsy | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Kidney transplantation | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Knee arthroplasty, chronic infection | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Motor vehicle accident | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Motor vehicle accident, prostate op. | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Nephrectomy | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Prostate cancer removal | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Stone removal | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Total prosthetic knee replacement | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| TUR-P, pleural excision | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Varicocele | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Vitrectomy under local anaesthesia | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Total | 20 | 100.0 | 21 | 100.0 |

TAH-BSO: Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TUR-P: Transurethral resection of prostate.

Likewise, there were no differences between the groups in terms of duration of procedure, location, incision length, estimated blood loss and amount of local anesthetic used for infiltration. Prescription drugs used by patients were recorded, and comparison of the groups revealed no significant differences (Table 4).

Table 4.

Other clinical findings

| Control group | Study group | P value | |

| Duration of procedure | 44.0 ± 11.0 | 44.9 ± 9.8 | 0.783 |

| Location of fistula creation | - | ||

| Dominant | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Non-dominant | 19 (95.0%) | 21 (100.0%) | |

| Fistula location | |||

| Brachiocephalic | 12 (60.0%) | 13 (61.9%) | > 0.999 |

| Snuff-box | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | > 0.999 |

| Radiocephalic | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | > 0.999 |

| Brachiobasilic | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| Incision length | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | 0.979 |

| Estimated blood loss | 42.5 (20.0-120.0) | 50.0 (10.0-120.0) | 0.530 |

| VAS | 4.5 (2.0-10.0) | 2.0 (1.0-8.0) | < 0.001 |

| Willingness to repeat the procedure | 3.0 (1.0-9.0) | 8.0 (5.0-10.0) | < 0.001 |

| Demand of analgesic | 9 (45.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0.069 |

| Amount of local analgesic | 22.5 (15.0-38.0) | 20.0 (15.0-40.0) | 0.607 |

| Anticoagulant | 14 (70.0%) | 12 (57.1%) | 0.596 |

| Beta blocker | 2 (10.0%) | 4 (19.0%) | 0.663 |

| Antihypertensive | 10 (50.0%) | 12 (57.1%) | 0.885 |

VAS: Visual analog scale.

Preoperative hemodynamic parameters, such as systolic/diastolic blood pressures, heart beats per minute, peripheral oxygen saturation and respiratory rate, are displayed in Table 5. Comparison of these parameters between the control and study groups revealed no differences. However, postoperatively all these parameters showed significant differences between the groups. Postoperative mean systolic blood pressure was 159 (± 22.65) mmHg in the control group while it was 144.53 (± 15.87) mmHg in the study group (P = 0.016). Similarly, postoperative mean diastolic blood pressure was 89 (± 8.08) mmHg in the control group while it was 81.86 (± 7.20) mmHg in the study group (P = 0.004). Postoperative heart and respiratory rates were found be significantly lower in the study group as well (P = 0.004 and P = 0.001, respectively). Additionally, due to improvement of all these hemodynamic parameters, oxygen saturation measured postoperatively was higher in the study group (P = 0.007) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hemodynamic measurements regarding for follow-up times

| Pre-op | Post-op | P value | Difference | |

| SBP | ||||

| Control group | 154.00 ± 22.34 | 159.80 ± 22.65 | < 0.001 | 5.80 ± 6.20 |

| Study group | 154.10 ± 17.74 | 144.52 ± 15.87 | < 0.001 | -9.58 ± 6.04 |

| P value | 0.988 | 0.016 | < 0.001 | |

| DBP | ||||

| Control group | 84.95 ± 10.08 | 89.15 ± 8.08 | < 0.001 | 4.20 ± 4.63 |

| Study group | 87.90 ± 10.89 | 81.86 ± 7.20 | < 0.001 | -6.04 ± 7.41 |

| P value | 0.373 | 0.004 | < 0.001 | |

| HR | ||||

| Control group | 77.45 ± 7.07 | 84.45 ± 10.25 | < 0.001 | 7.00 ± 6.08 |

| Study group | 81.71 ± 8.78 | 75.52 ± 8.12 | < 0.001 | -6.19 ± 6.79 |

| P value | 0.096 | 0.004 | < 0.001 | |

| SAT | ||||

| Control group | 98.75 ± 1.25 | 98.30 ± 1.66 | 0.095 | -0.45 ± 1.15 |

| Study group | 99.19 ± 1.08 | 99.52 ± 0.87 | 0.049 | 0.33 ± 0.73 |

| P value | 0.234 | 0.007 | 0.012 | |

| RR | ||||

| Control group | 19.00 ± 1.38 | 20.35 ± 1.46 | < 0.001 | 1.35 ± 1.42 |

| Study group | 19.67 ± 1.46 | 18.95 ± 1.07 | 0.025 | -0.72 ± 1.35 |

| P value | 0.141 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

Data were shown as mean ± SD. The comparisons between pre- and post-op measurements within each group, Paired t-test, according to the Bonferroni Correction P < 0.025 was considered as statistically significant. The comparisons between control and study groups, Student’s t test, according to the Bonferroni Correction P < 0.025 was considered as statistically significant except for the comparisons at the last column. SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; HR: Heart rate; SAT: Peripheral oxygen saturation; RR: Respiratory rate.

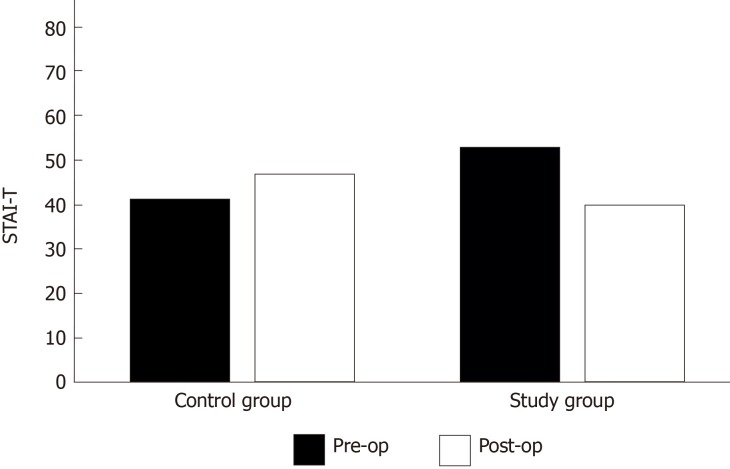

Based on the anxiety assessment results, no significant differences were found in the situational (state) and baseline (trait) anxiety scores between the two groups before surgery (P = 196 and P = 0.845, respectively). However, the mean postoperative state anxiety scores in the study and control groups were 40.0 (16-56) and 47.00 (25-77), respectively (P = 0.025) (Figure 1). Additionally, the study group’s postoperative mean state anxiety level was significantly lower than the study group’s preoperative state anxiety level (P ≤ 0.001), as shown in Table 6.

Figure 1.

Mean postoperative state anxiety scores in the study and control groups. STAI-T: State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Transient.

Table 6.

Anxiety measurements regarding for follow-up times

| Pre-op | Post-op | P value | Difference | |

| STAI-T | ||||

| Control group | 41.5 (24.0-61.0) | 47.0 (25.0-77.0) | 0.070 | 5.0 (-16.0–19.0) |

| Study group | 53.0 (24.0-72.0) | 40.0 (16.0-56.0) | < 0.001 | -12.0 (-32.0– -2.0) |

| P value | 0.196 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | |

| STAI-S | ||||

| Control group | 49.0 (31.0-78.0) | - | - | - |

| Study group | 48.0 (31.0-78.0) | - | - | - |

| P value | 0.845 | - | - | |

Data were shown as median (min-max). The comparisons between pre- and post-op measurements within each group, Wilcoxon sign rank test, according to the Bonferroni Correction P < 0.025 was considered as statistically significant. The comparisons between control and study groups, Mann Whitney U test, according to the Bonferroni Correction P < 0.025 was considered as statistically significant except for the comparisons at the last column. STAI-T: State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Transient; STAI-S: State Trait Anxiety Inventory-State.

As secondary outcomes of the study, perceived postoperative pain, need for analgesic treatment and willingness to repeat the procedure were assessed (Table 4). This assessment revealed a significant difference in perceived pain scores in favor of patients in the study group (P ≤ 0.001). However, there was no difference in the need for postoperative analgesic treatment between the two groups (P = 0.069). In conjunction with the reduced perceived pain score, a significant difference was found in the willingness to repeat the surgery. Patients in the study group indicated more willingness to repeat the surgery compared to patients in the control group (P ≤ 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Everyday hundreds of new patients are being added to transplantation waitlists due to the massive increase of end-stage kidney and liver disease diagnoses worldwide. The best treatment is to prevent the occurrence of these diseases however, despite many measures taken by the World Health Organization and other international health care organizations, their rise seems to be inevitable[7]. Consequently, the transplant community faces a huge gap between the demand and supply of transplantable organs. The organ shortage keeps patients on long waitlists and dependent on hemodialysis until a suitable donor is matched.

On the other hand, the waitlisted patient goes through different psychological stages including denial of the disease, anxiety and feeling powerless. On some occasions, necessary interventions are delayed by the patients themselves due to this high anxiety and denial of the disease progress. This problem can be deterred by building rapport with the patient and family, informing them beforehand about the procedures awaiting and trying to help manage their anxiety properly. This approach can eliminate the need for urgent dialysis initiations, canceled operations and allow for better outcomes[13,14].

Methods to manage anxiety effectively has received significant recognition lately[15]. One frequent way to achieve this is by music therapy. Listening to music is considered to be a safe and easy to implement therapy which is shown to reduce patients` anxiety and pain in several clinical studies in the literature. It has been found to benefit patients receiving spinal anesthesia, shock wave lithotripsy, craniotomy, burn dressing changes and various other surgeries requiring general anesthesia[16-19]. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical research that included patients with ESRD waiting for a kidney transplant and undergoing arteriovenous fistula creation for the first time with local anesthesia.

The most emphasized mechanism by which music therapy is thought to decrease pain perception and anxiety is by changing the electrical activity of the brain during the stress-causing event[20]. Music intervention also acts as a distractor and distance the patients from their surroundings. It can isolate them from the stress-causing sounds like instrument beeps, operating room conversations, and surgeon`s orders, which are estranging to many people[21,22]. The combination of relaxation, distraction, and isolation from surrounding sounds achieved with music therapy can improve perceived pain and help patients cope with anxiety[22].

Pain killers are commonly prescribed for people to manage and suppress pain. However, these drugs tend to work rather quickly and can sometimes be habit-forming. Furthermore, their use is not recommended due to high costs, side effects and possible drug interactions. In this study, no difference was found in terms of the need for analgesia between the two groups. In a study performed to evaluate the effect of music therapy on pain and satisfaction in patients who underwent endoscopy/colonoscopy, members of the control group reported significantly higher pain than those in the music group[19] Similar to our results, Gokçek et al[23] showed less analgesic requirement in patients undergoing septorhinoplasty under general anesthesia with music therapy.

Anxiety also increases the heart rate, respiratory rate, cardiac output and need for oxygen in the body. Elevated anxiety levels may even cause uncontrolled hypertension in a preemptive ESRD patient, tipping the delicate balance in favor of urgent dialysis. Moreover, in elderly ESRD patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, cardiac complication rates increase significantly during and after the surgery due to anxiety. In this study, physiological indices, such as heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation, were found to be significantly better in patients in the study group compared to those in the control group. Cakmak et al[17] reported that hemodynamic parameters were significantly more favorable in patients who listened to music during a shock wave lithotripsy procedure. Similarly, listening to music during spinal anesthesia also alleviates physiological indices, such as heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure[16]. In addition, patients who listened to music during awake craniotomies had reduced heart rates and lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels compared to patients who did not[18].

The mechanism of action of music on the hemodynamic parameters could be due to a modulation of the neurohormonal response[24]. This neurohormonal impact could be related to intraoperative stress and the release of norepinephrine, epinephrine, cortisol and adreno-corticosteroid Hormones. Although a simultaneous blood cortisol analysis would have given us a better understanding of the underlying physiological mechanisms, no such analysis was performed in the context of our study and is recommended for future studies measuring anxiety levels in patients.

Correspondingly, we found that the mean postoperative state anxiety score in the study group was significantly lower than that in the control group. This result is in line with the literature[16-18,20]. In previous studies, patient satisfaction and willingness to repeat the procedure have been shown to improve with music therapy. Our results are consistent with the findings of Cakmak et al[17] in this regard. In this context, there are similarities with the results of our study with the study performed by Bashiri et al[20]; patients who received music therapy during the endoscopy/colonoscopy procedure did not differ from the control group in terms of patient satisfaction, but patients in the intervention group indicated that they would prefer the same method for their next procedure.

In order to reduce anxiety and improve the outcomes of waitlisted kidney transplant recipient candidates, we suggested listening to music for reducing the anxiety levels of pre-dialysis patients undergoing arteriovenous fistula surgeries. We demonstrated that listening to music during surgery could decrease anxiety, increase the patient’s willingness to repeat the procedure and reduce overall pain related to surgery.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Music therapy is an easy to apply, cheap and effective method to reduce perceived anxiety and pain during stress causing situations like surgery. Its application has been shown to improve patient satisfaction and willingness to repeat the procedure, consequently, promoting patient compliance.

Research motivation

Arteriovenous fistula creation is an important procedure which many patients have to go through after they receive the diagnosis of end stage kidney disease. If suitable, they also are being worked-up or put on the list to wait for a kidney transplantation. All these developments cause anxiety and confusion to the patient and relatives. As a physician it is our duty to reduce their anxiety and help them cope with these stressful events.

Research objectives

We sought to investigate the effects of music therapy on patients undergoing arteriovenous fistula creation surgery. The arteriovenous fistula creation surgery is usually performed under local anesthesia as a day procedure.

Research methods

This study is designed as a randomized, single blind clinical trial where suitable patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were approached and asked for consent. Among the 55 who were consented, 14 were excluded due to requirement of sedation or uncompleted questionnaire forms. Remaining 41 were analyzed using STAI anxiety questionnaires, visual analog scales and vital signs closely related to anxiety and pain perception.

Research results

The STAI anxiety scoring results showed that music therapy was effective to reduce procedure related anxiety in patients undergoing fistula creation surgery. The overall patient satisfaction was found to be significantly higher in the music group as well. Perceived pain related to surgery was effectively reduced via listening to music, although there was no difference between analgesic use among the groups. Additionally, intra-operative heart rate and blood pressure measurements were significantly lower in the music group (P < 0.05).

Research conclusions

This study shows that music therapy can be a useful tool to relieve patients` anxiety and pain undergoing fistula creation surgery.

Research perspectives

Future studies should focus on more ways to implement music into patient treatments and enlighten the mechanisms in which music therapy provides relief. Additionally, it would be beneficial to investigate which types of music provide better outcomes while undergoing surgery.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Diskapi Research and Training Hospital Ethics Committee.

Clinical trial registration statement: This study is registered at Diskapi Research and Training Hospital Clinical Trials Registry. The registration identification number is 41303261/iTK.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors of this manuscript having no conflicts of interest to disclose.

CONSORT 2010 statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 Statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 Statement.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 2, 2019

First decision: February 20, 2020

Article in press: March 26, 2020

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hilmi I, Markic D, Wang GY S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li X

Contributor Information

Sanem Guler Cimen, Department of General Surgery, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey. s.cimen@dal.ca.

Ebru Oğuz, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey.

Ayse Gokcen Gundogmus, Department of Psychiatry, Diskapi Research and Traning Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey.

Sertac Cimen, Department of Urology, Diskapi Research and Traning Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey.

Fatih Sandikci, Department of Urology, Diskapi Research and Traning Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey.

Mehmet Deniz Ayli, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Diskapi Research and Training Hospital, Health Sciences University, Ankara 06110, Turkey.

Data sharing statement

There is no additional data available.

References

- 1.Black CK, Termanini KM, Aguirre O, Hawksworth JS, Sosin M. Solid organ transplantation in the 21st century. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:409. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.09.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson BM, Akizawa T, Jager KJ, Kerr PG, Saran R, Pisoni RL. Factors affecting outcomes in patients reaching end-stage kidney disease worldwide: differences in access to renal replacement therapy, modality use, and haemodialysis practices. Lancet. 2016;388:294–306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30448-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domenick Sridharan N, Fish L, Yu L, Weisbord S, Jhamb M, Makaroun MS, Yuo TH. The associations of hemodialysis access type and access satisfaction with health-related quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.05.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SD, Cukor D, Kimmel PL. Anxiety in Patients Treated with Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:2250–2255. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02590316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olagunju AT, Campbell EA, Adeyemi JD. Interplay of anxiety and depression with quality of life in endstage renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoong RK, Mooppil N, Khoo EY, Newman SP, Lee VY, Kang AW, Griva K. Prevalence and determinants of anxiety and depression in end stage renal disease (ESRD). A comparison between ESRD patients with and without coexisting diabetes mellitus. J Psychosom Res. 2017;94:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns T, Fernandez R, Stephens M. The experiences of adults who are on dialysis and waiting for a renal transplant from a deceased donor: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:169–211. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corruble E, Durrbach A, Charpentier B, Lang P, Amidi S, Dezamis A, Barry C, Falissard B. Progressive increase of anxiety and depression in patients waiting for a kidney transplantation. Behav Med. 2010;36:32–36. doi: 10.1080/08964280903521339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbin ML, Greene T, Cheung AK, Allon M, Berceli SA, Kaufman JS, Allen M, Imrey PB, Radeva MK, Shiu YT, Umphrey HR, Young CJ Hemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study Group. Arteriovenous Fistula Development in the First 6 Weeks after Creation. Radiology. 2016;279:620–629. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradt J, Dileo C, Shim M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD006908. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006908.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386:1659–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Öner N, Le Compte A. Hand book of state-trait anxiety inventory. No. 333. Turkey: Bogaziçi University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meguid El Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365:331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketteler ER. Beyond the Technical: Determining Real Indications for Vascular Access and Hemodialysis Initiation in End-Stage Renal Disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viecelli AK, Lok CE. Hemodialysis vascular access in the elderly-getting it right. Kidney Int. 2019;95:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koelsch S, Jäncke L. Music and the heart. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3043–3049. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cakmak O, Cimen S, Tarhan H, Ekin RG, Akarken I, Ulker V, Celik O, Yucel C, Kisa E, Ergani B, Cetin T, Kozacioglu Z. Listening to music during shock wave lithotripsy decreases anxiety, pain, and dissatisfaction: A randomized controlled study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2017;129:687–691. doi: 10.1007/s00508-017-1212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu PY, Huang ML, Lee WP, Wang C, Shih WM. Effects of music listening on anxiety and physiological responses in patients undergoing awake craniotomy. Complement Ther Med. 2017;32:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Zhou L, Wang Y. The effects of music intervention on burn patients during treatment procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:158. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1669-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bashiri M, Akçalı D, Coşkun D, Cindoruk M, Dikmen A, Çifdalöz BU. Evaluation of pain and patient satisfaction by music therapy in patients with endoscopy/colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:574–579. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.18200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauck M, Metzner S, Rohlffs F, Lorenz J, Engel AK. The influence of music and music therapy on pain-induced neuronal oscillations measured by magnetencephalography. Pain. 2013;154:539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson U. The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: a systematic review. AORN J. 2008;87:780–807. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gokçek E, Kaydu A. The effects of music therapy in patients undergoing septorhinoplasty surgery under general anesthesia. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vetter D, Barth J, Uyulmaz S, Uyulmaz S, Vonlanthen R, Belli G, Montorsi M, Bismuth H, Witt CM, Clavien PA. Effects of Art on Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:704–713. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no additional data available.