Abstract

Badminton is a popular sport in India and with multiple medal prospects will be closely followed at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Considered the fastest of the racquet sports, players require aerobic stamina, agility, strength, speed, and precision, besides requiring good motor coordination and complex racquet movements. Injuries in badminton are common despite it not being a contact sport, and include overuse injuries, and acute traumatic events. The game is physically challenging and demands complex repetitive upper and lower extremity movements with constant postural variations and poses a high risk of overuse injuries to both the appendicular and axial musculoskeletal systems. Badminton also necessitates short bursts of movement with sudden sharp changes in direction, which places players at risk of non-contact traumatic injuries to joints and muscle–tendon units. Preventing injuries and decreasing time away from training and competition are critical in an elite badminton player’s sporting career. This analytical review identifies the incidence, severity, and profile of badminton injuries in elite players, and discusses the biomechanical basis of these injuries.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s43465-020-00054-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Badminton, Injuries, Epidemiology, Biomechanics

Introduction

Badminton is a popular competitive and recreational sport in India and can trace its origins to British colonisation in the nineteenth century. Participation in the sport and spectator interest has progressively improved over the last several decades in India, Asia and Europe. Indian players have occupied the Badminton World Federation (BWF) top ranking in both men’s and women’s singles, and at present India occupies more players in men’s singles top thirty ranking than any other country [1]. The recent success of the Premier Badminton League (PBL) has added to the popularity and commercial appeal of the game within the country. Having won a medal at each of the past two Olympics [2], Badminton will be a sporting discipline that captures the attention and hopes of the nation in the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

Badminton is a high-paced game and is considered the fastest of the racquet sports. Played with predominantly overhead shots, competitive badminton demands excellent fitness. Singles warrants extraordinary physical capabilities and is a game of patient positional manoeuvring, whereas doubles, on the other hand, requires all-out aggression throughout the game and is often extremely fast-paced. Players require aerobic stamina, agility, strength, speed and precision. It is also a technical sport, requiring good motor coordination and the development of sophisticated racquet movements. Although badminton biomechanics have not been the subject of extensive scientific research, studies have determined the mechanisms of power generation especially in jump smashes, and analysed the efficiency of different lunge techniques that are a key to success in repetitive shuttlecock retrieval.

Injuries in badminton are common despite it not being a contact sport. These include not only overuse injuries, but also acute traumatic events. The game is physically challenging and demands complex movements with constant postural variations in the form of lunges, reaches, retrievals and jumps. Moreover, repetitive overhead forehand and backhand strokes executed with a very short hitting action, and incorporating deception, apply excessive stress on the upper extremity. Competitive players are therefore prone to overuse injuries of the upper limb, axial skeleton and lower limb. Badminton also necessitates short bursts of movement with sudden sharp changes in direction, including diving for shuttlecock retrieval. This places players at risk of non-contact traumatic injuries to joints and muscle–tendon units. Rarely, collision between doubles partners, or their racquets, can cause contact injuries including concussion and ocular trauma.

Preventing injuries and decreasing time away from training and competition are critical in an elite badminton player’s sporting career. Injury prevention in any sport is a sequence of four steps: injury surveillance to establish the extent of the problem, identifying the aetiology and mechanisms of injury, introducing preventive measures and last, evaluating their effectiveness [3]. This analytical review attempts to accomplish the first step of this process by identifying the incidence, severity, and profile of badminton injuries in elite players, and understanding the biomechanical basis of these injuries.

Epidemiology of Badminton Injuries

Badminton is widely played in our country and the success of Indian players at the international level is steadily increasing. There is, however, a lack of injury surveillance in competitive badminton in India and this limits our ability to accurately determine the injury burden that can be attributed to the sport. There are a few studies conducted amongst badminton players from Denmark, Japan, Hong Kong and Malaysia; however, the data from these studies show a wide spectrum of variability due to differences in study design, definition of injury, and classification of type and severity of injury. Based on the available literature and the experience of our sports medicine centre that caters to the national badminton team and training academy, we present the most comprehensive badminton sport-specific injury data available, including the common injuries that can be expected in the sport.

Jorgensen and Winge [4] conducted a prospective study involving injury registration over a single badminton season in 375 randomly chosen elite and recreational badminton players, of whom 81% could be followed. The data collection was done via self-registration and was defined as any injury that bothered the athlete. There was no formal method of injury diagnosis or injury severity assessment. They reported 257 injuries, at an incidence of 2.9 injuries/player/1000 badminton hours. Men were more frequently injured than women. The prevalence was 0.3 injuries per player. There was no difference between elite and recreational badminton players. 92% of the injured were playing with their injury. The pathophysiology was overuse in 74%, strains in 12%, sprains in 11% and fractures in 1.5%. They noted that the majority of injuries occurred in the lower extremity, most notably in the knee and ankle. They noted that injuries commonly occurred for elite players during training and those in recreational players occurred more commonly in a competitive setting. They attributed this finding to the lack of physical conditioning towards a competitive game for recreational players.

Hoy et al. [5] conducted a hospital-based cross-sectional study which included 100 badminton players over a 1-year period. Data were collected at the point of contact and injuries were followed up at predefined intervals. Injury classification was based on the abbreviated injury severity scale (AIS). Based on timing of injury, they found that 72% of injuries took place during competition as compared to during training. This was notably in contrast to other studies and might be attributed to the hospital-based nature of the study along with the injury definition. They noted an injury incidence of 5%; based on the total sports-related injuries reporting to the hospital.

Another hospital-based retrospective study conducted by Kroner et al. [6] showed an injury incidence of 4.1%, with 82.9% being lower extremity injuries. 128 injuries occurred in the ankle joint which constituted 62% of all documented injuries. In addition to this, there were 11 patients with Achilles tendon injuries that required hospital-based treatment.

In an investigation conducted by Shariff et al. [7] into the pattern of musculoskeletal injuries sustained by Malaysian badminton players, they concluded that the majority of the injuries occurred during training (86.6%). Injuries were sustained most commonly around the knee and were related to overuse injuries, without a single attributable traumatic episode. They noted a higher incidence amongst younger players but no difference amongst gender. In their retrospective study, they noted that 63% of injuries involved the lower limb with the nature of injury being overuse (36%), strain (30.9%) and sprain (26%). They noted a total of 10 severe injuries in the two-and-a-half-year study period. These included Achilles tendon ruptures, anterior cruciate ligament tear, meniscal tears and metatarsal fractures. No severe injuries were reported for the upper limb or any other anatomic locations.

A longitudinal study on badminton injuries amongst Japanese national level players conducted by Miyake et al. [8] revealed an injury rate per player per 1000 h ranging from 0.9 to 5.1. The injury rate during practice was higher in women than in men and increased with age. There was a significant increase in injury rate with age and female gender. Based on the severity of injury, the proportion of injuries were slight injury 83.8%, minimal injury 4.1%, moderate injury 6.8% and severe injury 1.9%. Similar to studies by Jorgensen and Ogiuchi [9], this study showed that the majority of the injuries documented resulted from overuse patterns rather than a single acute injury episode (77.1% in matches and 75.4% in practice). They concluded that overuse injury is approximately 3 times more common than trauma in badminton. Higher injury rates were noted for the lumbar spine, dominant knee joint and dominant shoulder joint. The authors noted a higher injury rate with increase in age. They also noted a significant gender variation with a higher rate amongst female players. Also compared to other studies, the point of contact for injury assessment and data collection was the team medical staff. This allowed for a more complete injury assessment of the player along with close follow-up. This may also account for the high incidence of slight and overuse injuries, which possibly would be missed amongst hospital-based studies.

Goh et al. [10] conducted a prospective study amongst adolescent badminton players over a 1-year time period. They identified an injury rate of 0.9 injuries per player per 1000 training hours. They noted that 64% of all injuries were strains and sprains and one-third of all injuries involved the lower limb, especially the knee joint.

Fahlstrom et al. [11] noted in their study that the majority of injuries occurred in the lower limb with maximal involvement of the Achilles tendon and ankle. On comparison between Achilles tendon ruptures and other injuries, data showed that patients suffering Achilles tendon rupture were significantly older than players with other injuries. Other compared parameters—height, weight and BMI—showed no significant differences. Based on time of injury occurrence during matches, they noted that 66.7% of Achilles tendon ruptures occurred towards the end of matches. Similar results are reported by Kaalund et al. [12] and Inglis and Sculco [13].

A retrospective study of elite Hong Kong badminton players conducted by Yung et al. [14] revealed an overall injury incidence rate of 5.04 per player per 1000 h. They noted that elite senior athletes had a high incidence rate of recurrent injuries, whilst elite junior and potential athletes had a higher incidence rate of new injuries. Most new injuries were strains (64%) and the most frequently injured body sites were the back, shoulder, thigh and knee. More injuries were recorded in training for all groups of players. The incidence of lumbar facet joint sprains was also high and ranked second amongst all types of injuries.

Biomechanics and Injury Patterns

Badminton is a biomechanically demanding sport. The physical work is intermittent, involving high-intensity activity interspersed with very short rest pauses. The game revolves around speed and deception, and involves abrupt jerking movements with rapid footwork. This combination of repetitive manoeuvres places major stresses on the upper and lower extremities and increases the risk for acute and chronic injuries of varying severity. The sudden and frequent acceleration and deceleration manoeuvres involved in badminton place a substantial eccentric load on the lower extremities, risking strains, sprains and ligament injuries. Meanwhile, the recurring motion of overhead strokes and short hitting action places repetitive rotational stress on the upper extremity, especially the shoulder [15].

Badminton strokes are made with forearm rotation and the importance of radio-ulnar pronation, elbow extension and wrist ulnar deviation has been shown by Sakurai et al. [16] in their three-dimensional analysis of badminton strokes. Radio-ulnar pronation and shoulder rotation are shown to contribute 53% of the shuttle velocity in a badminton smash. A study conducted on the biomechanics of the forehand and backhand strokes showed that skilled players reached significantly higher angular velocities of glenohumeral external rotation, forearm supination and wrist extension in the backhand stroke, compared to less-skilled players, but there was no such difference in the forehand stroke.

Tsai et al. [17] measured the surface EMG activity of several upper limb muscles during badminton smash and jump smash. They reported that the jump smash exerted higher EMG activity than smash in the phase before contact point, suggesting that pre-impact EMG activation is the most important part of shuttle velocity.

The need of muscular endurance combined with appropriate maximal and explosive muscle strength in elite badminton players is gaining importance. Andersen et al. also showed that musculature of the lower extremities is especially important since rapid and forceful movements with the weight of the body are performed repeatedly throughout a match. The cyclical bursts of action during games are demanding on the aerobic (60–70%) and anaerobic systems (30%) with a greater demand on the alactic metabolism [18]. Compared to female badminton athletes, male athletes exhibited greater match duration, work density, rest time and aerobic/anaerobic fitness [19–22]. Compared to less-skilled badminton athletes, more skilled athletes generated quicker responses, faster shuttle smash velocities and better fitness levels [23].

Jump Smash

The badminton jump smash (Fig. 1) is an essential component of a player’s attacking shot selection and a significant stroke in gaining a point, accounting for 53.9% of winning shots. The speed of the shuttlecock exceeds that of any other racquet sport projectile with a maximum shuttle speed of 493 km/h reported in 2013 by Tan Boon Heong [24]. Several studies have aimed to quantify the contributions of specific joint movements and rotations to a badminton smash. The majority of the findings indicate that shoulder internal rotation makes the largest contribution (up to 66%) to shuttlecock velocity or racquet head speed in a badminton smash [24].

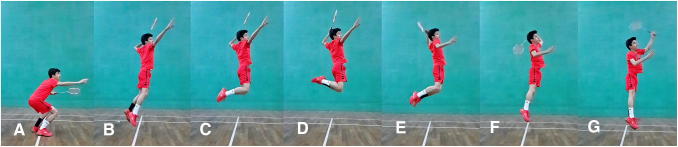

Fig. 1.

The jump smash is an elegant attacking shot in badminton and requires agility, flexibility, strength and precision. This stroke requires the effective transmission of explosive energy from the legs and trunk to the upper limb and into the racquet to ensure maximum shuttlecock velocity. Poor coordination in any component of the kinetic chain can not only negatively affect performance, but also predispose to stress injuries. Although multiple contributions are necessary to ensure optimal biomechanics, shoulder internal rotation makes the largest contribution to shuttlecock velocity or racquet head speed

A motion analysis study on 18 badminton players [24], aimed at identifying the technique factors that contribute to players producing high shuttlecock velocities, reported the following significant findings. The best individual predictor of shuttlecock velocity after impact was the elbow extension angle at end of retraction phase (ER), explaining 51.5% of the variations in velocity. The badminton players with the fastest shuttlecock velocity had a smaller elbow angle. Having a smaller elbow angle at the time of ER gives a larger range of motion at the elbow prior to shuttle impact over which to generate speed and also potentially puts the arm in a better position to use shoulder internal rotation to generate wrist and racket speed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Motion analysis of jump smash has suggested that the best individual predictor of high shuttlecock velocity after impact is elbow extension angle at the end of retraction phase (ER). The badminton players with the fastest shuttlecock velocity have a smaller elbow angle. Having a smaller elbow angle at the time of ER gives a larger range of motion at the elbow prior to shuttle impact over which to generate speed, and also potentially puts the arm in a better position to use shoulder internal rotation to generate wrist and racket speed

Although jumping whilst performing a smash is a popular and effective technique in badminton games, jumping and landing sequence is commonly associated with injury. The majority of injuries occur in the lower extremity with the ankle and knee joint being particularly vulnerable. Rambley et al. [25] on analysis of the jump smash noted that majority of jumps were performed using only one foot. With landing occurring on the left foot in 61.9%, right foot in 27.4% and both feet in 10.7%. It was found that the majority of players performed the jump smash with their ipsilateral foot (side with racquet) and landing with their contralateral foot. They concluded that the single leg technique could contribute to injury occurrence in the ankle and knee joint.

Lower Extremity

Repetitive lunging is an essential part of badminton. The lunge movement allows the player to rapidly reach the shuttlecock and form a secure base from which to play the necessary shot and move back into the court to prepare for the next shot (Fig. 3). The task essentially consists of a breaking phase and accelerating phase, and forms an integral part of the start–stop–recovery cycle [26].

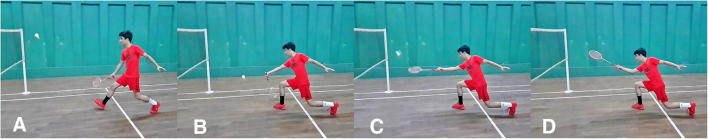

Fig. 3.

Repetitive and rapid lunging is an essential part of badminton. Efficient execution of a lunge movement with faster approaching speed and longer maximum lunge distance is a key to success. Peak vertical and horizontal forces at early contact phase are three times and two times an individual’s body weight, respectively, and this generates a high joint torque. Lunging produces strenuous impact loading on the ligaments of the lower limbs and contributes towards overuse knee injuries especially patellar tendinosis

Kuntze et al. [27] reported a lunge frequency of 15% of movements performed during competitive singles rallies. With a higher frequency of lunges at the international than national level (17.86 ± 4.83% and 14.29 ± 4.51% respectively), they noted three varieties of lunges: the hop lunge, step-in, and kick lunge. Evidence gathered by them showed that an adoption of the step-in lunge technique might be beneficial for reducing muscle fatigue and soreness. It was also made evident that the hop lunge increased the force output of the dominant limb by optimising force generating processes, which may prove advantageous for quick recovery and movement beyond the start position. Adoption of this movement may be recommended to enhance the contribution of the knee and ankle joint to the mechanism of lunge recovery.

Rapid and repetitive badminton lunges and jumps have been implicated to produce strenuous impact loading on the lower extremities of players, resulting in overuse knee injuries [7]. High vertical and horizontal impact forces at early contact phase generate a high joint torque on the ligaments of the lower limbs in badminton jump and lunge [19, 23]. These forces are thought to be contributing factors of patellar tendinosis and ACL injuries [11, 15, 27–29]

Analysis of badminton lunge characteristics amongst athletes [23] showed that male athletes had faster approaching speed and longer maximum lunge distance compared with female athletes. Efficient execution of a lunge movement is a key to success in badminton. Peak vertical and horizontal forces experienced from it may be up to three times and two times of an individual’s body weight, respectively. Analysis of results showed that unskilled athletes exhibited greater peak horizontal ground reaction forces and greater peak knee flexion moments. Higher knee flexion/extension moments were associated with greater quadriceps forces and tibial shear forces, implying that unskilled athletes may be exposed to higher risk of overuse injuries. In addition, unskilled female athletes were noted to experience higher impacts during landing and thus more vulnerable to lower extremity injuries.

Badminton is a non-contact sport characterised by pronounced laterality. Habitual loading activities provoke changes in structural and mechanical properties of athlete’s tendons and muscles. The loading characteristics of the sport on the lower limbs could be one of the reasons for overuse injuries being approximately three times more frequent than traumatic injuries. Lunges are common in badminton and are related to a high risk of overuse injuries, such as patellar and Achilles tendinopathies [30].

Couppe et al. [30] in their study on tendon properties noted that the distal patella tendon cross-sectional area (CSA) was significantly more in the dominant limb and in athletes without patella tendinopathy. They also noted that distal patella stress was greater in athletes with patella tendinopathy. Furthermore, smaller CSA in dominant and non-dominant side of athletes with patella tendinopathy may point towards a predisposing factor for development of patella tendinopathy.

Upper Extremity

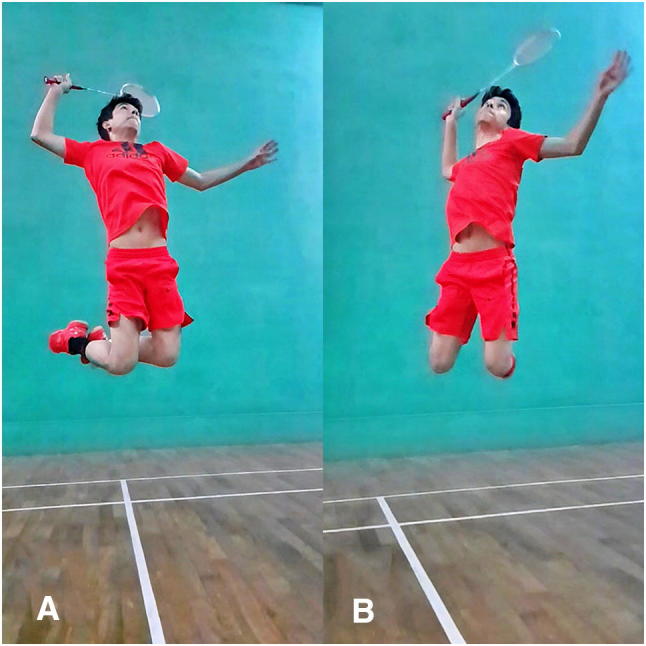

Badminton places a high degree of load on the shoulder joint, and a characteristic feature of this sport is that it requires increased range of shoulder mobility. Internal rotation of the arm is an essential component of an effective smash. Forearm supination and pronation also form a key component of the stroke kinetic chain (Fig. 4). Badminton strokes require the transmission of energy from the legs and the trunk to the upper limb and into the racquet. Poor coordination in any component of the kinetic chain can negatively affect the performance. In a study of 44 badminton players, 25% of injuries were noted to occur in the upper limb. Similar findings were noted in the assessment of 469 elite level badminton players, with 18.1% incidence of upper limb injuries. In the epidemiological assessment conducted by Jorgensen et al. [4], they showed that majority of the injuries involving the upper limb were related to overuse type injuries (69/70). 25% of these were lateral epicondylitis and 59% were tendinitis, periostitis and unspecified pain in the upper arm (32%) and shoulder (27%).

Fig. 4.

Computerised motion analysis in badminton can determine subtle biomechanical faults during specific strokes and suggest appropriate corrections to improve efficiency and prevent overuse injuries

A quantitative research survey of risk factors for shoulder pain amongst Japanese badminton players [31] showed that the factor with the highest correlation to the onset of injuries was a history of pain in the past (> 1 year). They also noted that competitors who received care had 1.68 times higher odds of developing pain than those who did not receive care. Also, as competitive history increased each year, the likelihood of developing shoulder joint pain increased by 1.06.

Shoulder injuries and shoulder pain are common in badminton due to repetitive overhead strokeplay. Postural asymmetry is typically considered to be associated with injuries. However, asymmetry in the overhead athlete’s scapula is a normal finding due to the dominant use of the limb. Three-dimensional assessment of scapular kinematics showed that, in all healthy overhead athletes, the scapular was more internally rotated and anteriorly tilted than the non-dominant side. Therefore, injured athletes may display more asymmetry and there may be a threshold limit for scapular posture. A baseline pre-injury assessment will help to understand and assess this change along the spectrum [32].

Lateral epicondylitis is common and is secondary to a repetitive short hitting action unique to badminton [7]. A short hitting action is not only useful for deception; but it also allows the player to hit powerful strokes when there is no time for a big arm swing. A big arm swing is also usually not advised in badminton because bigger swings make it more difficult to recover for the next shot in fast exchanges. The use of grip tightening is crucial to these techniques, and is often described as finger power. Elite players develop finger power to the extent that they can hit some power strokes, such as net kills, with less than a 10 cm racquet swing.

Spine Injuries

In a study of 44 elite Hong Kong badminton players, there was an injury incidence of 14% for spine injuries and the incidence of facet problems was ranked second amongst all types of injuries in the study. The repetitive extension of the lumbar spine during overhead or jumping smash was thought to be associated with the high incidence rate of facet problems.

Several studies have reported that dysfunction in the trunk or lower extremities has a significant association with elbow and shoulder injuries in adult overhead athletes. Sekiguchi et al. [33] noted that the prevalence of low back, hip, knee or foot pain was significantly higher amongst young overhead athletes with elbow and/or shoulder pain. Furthermore, the pain in the elbow and/or shoulder more frequently coexisted with the pain in the back and hip, compared with the knee and foot. Some studies have demonstrated that poor core stability should be considered as a potential risk factor for elbow and shoulder injuries. Associations between pain in the trunk (including back and hip) and that in the elbow and shoulder have a much stronger connection than that in the lower extremity (including the knee and foot). The trunk is assumed to have an important role in generating power during overhead motion, and tilting the spine regardless of ground contact [33].

Overuse Injuries

Overuse injuries of the lower limb have been found to be the most commonly encountered injury in hospital-based, questionnaire-based, and physiotherapy assessment-based epidemiological studies in badminton. Of the lower limb, the most common sites of involvement are the patella tendon and the Achilles tendon. This can be attributed to the repetitive and eccentric loading that occurs at the knee and ankle joint. Overuse tendinopathy induces in the affected tendon pain and swelling, and associated decreased load tolerance and function during exercise of the limb. The essence of tendinopathy is a “failed healing response”. This model suggests that, after an acute insult to the tendon, an early inflammatory response that would normally result in successful injury resolution veers towards an ineffective healing response, with degeneration and proliferation of tenocytes, disruption of collagen fibres, and subsequent increase in non-collagenous matrix [34–37]. Due to the demanding nature of the sport with evidence of overuse injury pattern at all levels of the game and gender, there is an argument for a rotation of sports as part of the training regimen, especially in adolescent players.

Poor training technique and a variety of risk factors may predispose players to lower limb overuse injuries affecting the bone, including stress reactions and stress fractures. The underlying principle of the bone response to stress is Wolff’s law, whereby changes in the stresses imposed on the bone lead to changes in its internal architecture. Stress fractures, defined as microfractures of the cortical bone tissue, affect thousands of athletes per year. If left untreated, a stress fracture can progress to a complete fracture of a bone [38, 39].

Extrinsic Injuries

Ocular trauma in sports in relatively rare but is associated with high level of morbidity and disability. Badminton has been classified as a high-risk sport for ocular injury due to the small, dense shuttlecock that travels at such high speed in close proximity to players. In a study [40] of 85 patients with ocular injuries in badminton, 73 injuries occurred in doubles matches with 60 injuries resulting from shuttlecock impact. 80/85 injuries were non-penetrating in nature and 52 of the injuries occurred in doubles games and were partner involved. Amongst the 52 players who were hit by their partner, 51 were in the front court, and most turned to their partner as they were hitting a shot. There were only five patients with open globe injuries in the study, with all suffering from irreversible impairment of visual acuity. The Ontario Badminton Association has mandated protective eyewear for all junior players and recommended eye protection for all badminton players in 2005 [41, 42].

Discussion

In order for injury prevention measures to improve the safety of the sport, epidemiological research to identify the incidence, severity and injury profile of the sport is critical. Without an accurate assessment of the extent of the problem, further steps would be flawed. Although badminton is a popular sport and widely played recreationally and competitively, there are limited epidemiological studies and the data which are available have a lack of comparability due to inconsistent injury definitions, study design, and data collection. Despite this, we have drawn the following conclusions based on an analysis of the available literature on the epidemiology of injuries in elite badminton players.

Incidence In competitive badminton players, injury incidence varies between 0.9 and 7.38 per 1000 h, where 1 h is equal to 1 h participation of sport by one player [43–46]. The incidence of badminton-related injuries is different in diverse populations and even in the same population when comparing male and female players, competitive and recreational players, and players of different age groups [4–10].

Severity Badminton-related injuries are rarely severe and are reported between 1.9 and 26%. More often elite players sustain moderate (incidence 1.5–52%) and minor (incidence 22–91.5%) injuries.

Anatomical distribution The lower limb is the most affected region (Table 1) with 58–92.3% of injuries. The most affected part of lower limb is the knee followed by the ankle. In the knee, ligament sprains were reported as the most common injury in Swedish players, whilst patellar tendinopathy was reported as the most common injury in Malaysian players. Achilles tendon pain and tears, followed by ankle sprains, are the most common ankle injury whilst plantar fasciitis is the commonly reported injury in the heel. In the upper limb, shoulder pain was reported as the most common site of pain for international badminton players, with rotator cuff tendinopathy being the most common diagnosis. Elbow injury was mainly due to medial epicondylitis, wrist injury due to ligament sprain, and back injury due to muscle strain.

Table 1.

The incidence of badminton injuries based on anatomical region

| Article | Lower extremity | Upper extremity | Back | Head and neck |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jorgensen and Winge [4] | 58% | 31% | 11% | >1% |

| Kroner et al. [6] | 82.90% | 11.10% | 0.80% | 2.30% |

| Shariff et al. [7] | 63.10% | 18.10% | 16.60% | |

| Goh et al. [10] | 71.40% | 1.60% | 27% | |

| Fahlstrom et al. [11] | 92.30% | |||

| Nhan et al. [15] | 44.40% | 24.30% | 9.90% | 21.40% |

| Yung et al. [14] | 49.60% | 25% | 14% | 5% |

| Hensley and Paup [47] | 69% | 21% | 1% | 5% |

| Hoy et al. [5] | Majority |

Types of injuries When elite badminton players from all age groups are considered together, the majority of badminton-related injuries were overuse injuries (Table 2); however, in junior elite players acute traumatic injuries are three times more common than overuse injuries. When considering all upper limb injuries, 98.5% were reported due to overuse, whilst 26% of knee injuries, 17% of ankle injuries, and 79% of back injuries were reported due to overuse. In most studies, injuries sustained during non-competitive training outnumbered competitive match injuries (Table 3).

Table 2.

Overuse injuries in badminton are noted to occur more frequently than acute traumatic injuries

| Article | Jorgensen and Winge [4] | Miyake et al. [8] | Ogiuchi et al. [9] | Goh et al. [10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overuse injury | 169 | 200 | 79 | 16 |

| Acute injury | 66 | 32 | 46* |

*In this study, muscle strains have been categorised as acute injuries

Table 3.

Injury occurrence during competitive versus non-competitive play in badminton

Hence, we can conclude that although badminton is a non-contact sport, there is a significant risk of injuries. This prevalence of injuries is much higher than commonly assumed, and is almost similar to the incidence of injuries in other racquet sports such as tennis and squash. The majority of badminton injuries are secondary to overuse and are a result of excessive cumulative loads. Badminton coaches and trainers should note these observations and consider an alteration in the training workload of badminton players to allow the body to recover, and break the repetitive cycle leading to overuse injuries. Moreover, since data shows that younger aged badminton players are more prone to acute traumatic injuries, coaches should ensure game management techniques that inculcate a habit of “safe” and low-risk play in young exuberant players.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Badminton World Federation rankings; https://bwfbadminton.com/rankings/.

- 2.Badminton Association of India; https://www.badmintonindia.org/.

- 3.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Medicine. 1992;14(2):82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorgensen U, Winge S. Epidemiology of badminton injuries. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 1987;8(6):379–382. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Høy K, Lindblad BE, Terkelsen CJ, Helleland HE, Terkelsen CJ. Badminton injuries—a prospective epidemiological and socioeconomic study. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1994;28(4):276–279. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.28.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krøner K, Schmidt SA, Nielsen AB, Yde J, Jakobsen BW, Møller-Madsen B, Jensen J. Badminton injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1990;24(3):169–172. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.24.3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shariff AH, George J, Ramlan AA. Musculoskeletal injuries among Malaysian badminton players. Singapore Medical Journal. 2009;50(11):1095–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyake E, Yatsunami M, Kurabayashi J, Teruya K, Sekine Y, Endo T, Nishida R, Takano N, Sato S, Kyung HJ. A prospective epidemiological study of injuries in Japanese national tournament-level badminton players from junior high school to university. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;7(1):e29637. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.29637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogiuchi T, Muneta T, Yagishita K, Yamamoto H. Sports injuries in elite badminton players. Japanese Orthopedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;18:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goh SL, Mokhtar AH, Mohamad Ali MR. Badminton injuries in youth competitive players. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2013;53(1):65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahlström M, Björnstig U, Lorentzon R. acute badminton injuries. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 1998;8(3):145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaalund S, Lass P, Hogsaa B, Nohr M. Achilles tendon rupture in badminton. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1989;23:1024. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.23.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis A, Sculco T. Surgical repair of ruptures of the tendo Achilles. Clinical Orthopaedics. 1981;156:160–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yung PS-H, Chan RH-K, Wong FC-Y, Cheuk PW-L, Fong DT-P. Epidemiology of injuries in Hong Kong elite badminton Athletes. Research in Sports Medicine. 2007;15(2):133–146. doi: 10.1080/15438620701405263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nhan DT, Walter K, Jay Lee R. Epidemiological patterns of alternative racquet-sport injuries in the United States, 1997–2016. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;6(7):2325967118786237. doi: 10.1177/2325967118786237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurai S, Ikegami Y, Yabe K. A three-dimensional cinematographic analysis of badminton strokes. Biomechanics in Sports. 1989;5:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai, C.L., Yang, C.C., Lin, M.S., Huang, K.S. (2008). The surface emg activity analysis between badminton smash and jump smash. ISBS Conference Proceedings Archive.

- 18.Phomsoupha M, Laffaye G. The science of badminton: Game characteristics, anthropometry, physiology, visual fitness and biomechanics. Sports Medicine. 2015;45(4):473–495. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abian-Vicen J, Castanedo A, Abian P, Sampedro J. Temporal and notational comparison of badminton matches between men’s singles and women’s singles. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport. 2013;13:310–320. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller J. Physiological profiles of elite badminton players aspects of age and gender. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44:S1–S13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faude O, Meyer T, Rosenberger F, Fries M, Huber G, Kindermann W. Physiological characteristics of badminton match play. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2007;100:479–485. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0441-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieshout KAV, Lombard AJJ. Fitness profile of elite junior badminton players in South Africa. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance. 2003;9:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam W-K, Lee K-K, Park S-K, Ryue J, Yoon S-H, Ryu J. Understanding the impact loading characteristics of a badminton lunge among badminton players. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, R., Felton P.J., McErlain-Naylor S.A., Towler H., & King M.A. (2020). Optimum performance in the badminton jump smash.

- 25.Rambely, A.S., Osman, N.A.A., Usman, J., Abas, W.A.B.W. (2005). The contribution of upper limb joints in the development of racket velocity in the badminton smash. Proceedings of the XXIII International Symposium on Biomechanics in 139 Sport, 422–426.

- 26.Badminton Association of England . Level 1: Assistant coach training manual. Milton Keynes: BAE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuntze G, Mansfield N, Sellers W. A biomechanical analysis of common lunge tasks in badminton. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2010;28(2):183–191. doi: 10.1080/02640410903428533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boesen AP, Boesen MI, Koenig MJ, Bliddal H, Torp-Pedersen S, Langberg H. Evidence of accumulated stress in Achilles and anterior knee tendons in elite badminton players. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2011;19:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura Y, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Yamamoto Y, Tsukada H, Toh S. Mechanisms for anterior cruciate ligament injuries in badminton. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44:1124–1127. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.074153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couppé C, Kongsgaard M, Aagaard P, Vinther A, Boesen M, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Differences in tendon properties in elite badminton players with or without patellar tendinopathy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2013;23(2):e89–e95. doi: 10.1111/sms.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warashina Y, Ogaki R, Sawai A, Shiraki H, Miyakawa S. Risk factors for shoulder pain in Japanese badminton players: a quantitative-research survey. Journal of Sports Science. 2018;6:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyama S, Myers JB, Wassinger CA, Daniel Ricci R, Lephart SM. Asymmetric resting scapular posture in healthy overhead athletes. Journal of Athletic Training. 2008;43(6):565–570. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.6.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekiguchi T, Hagiwara Y, Momma H, Tsuchiya M, Kuroki K, Kanazawa K, Yabe Y, et al. Coexistence of trunk or lower extremity pain with elbow and/or shoulder pain among young overhead athletes: A cross-sectional study. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2017;243(3):173–178. doi: 10.1620/tjem.243.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate M, Silbernagel KG, Siljeholm C, Di Iorio A, De Amicis D, Salini V, et al. Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:235. doi: 10.1186/ar2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma P, Maffulli N. Basic biology of tendon injury and healing. Surgeon. 2005;3:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(05)80109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009;17:112–126. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181a3d625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maffulli N, Kenward MG, Testa V, Capasso G, Regine R, King JB. Clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy with tendinosis. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2003;13:11–15. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennell KL, Malcolm SA, Thomas SA, Wark JD, Brukner PD. The incidence and distribution of stress fractures in competitive track and field athletes: a twelve-month prospective study. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;24(211–7):23. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Difiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, Gregory A, Jayanthi N, Landry GL, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;48:287–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez JO, Lavina AM, Agarwal A. Prevention and treatment of common eye injuries in sports. American Family Physician. 2003;67:1481–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu, J., Yan, C., Jingpeng, M., Meng, Z., Caixia, K., Xiaojie, W., Jianjun, G., & Yi, L. (2019). Doubles trouble-85 cases of ocular trauma in badminton: Clinical features and prevention. British Journal of Sports Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Jao KK, Atik A, Jamieson MP, et al. Knocked by the shuttlecock: twelve sight threatening blunt-eye injuries in Australian badminton players. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2017;100:365–368. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawkins RD, Fuller CW. A prospective epidemiological study of injuries in four English professional football clubs. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1999;33(3):196–203. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.33.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks JHM. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: Part 1 match injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(10):757–766. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, Reddin DB. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 2 training Injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(10):767–775. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Best JP, McIntosh AS, Savage TN. Rugby World Cup 2003 injury surveillance project. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(11):812–817. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hensley LD, Paup DC. A Survey of Badminton Injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1979;13(4):156–160. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.13.4.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.