Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) of the limbs caused by Aeromonas species is an extremely rare and life-threatening skin and soft tissue infection. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the specific characteristics and the independent predictors of mortality in patients with Aeromonas NF. Sixty-eight patients were retrospectively reviewed over an 18-year period. Differences in mortality, demographics data, comorbidities, symptoms and signs, laboratory findings, microbiological analysis, empiric antibiotics treatment and clinical outcomes were compared between the non-survival and the survival groups. Twenty patients died with the mortality rate of 29.4%. The non-survival group revealed significant differences in bacteremia, monomicrobial infection, cephalosporins resistance, initial ineffective empiric antibiotics usage, chronic kidney disease, chronic hepatic dysfunction, tachypnea, shock, hemorrhagic bullae, skin necrosis, leukopenia, band polymorphonuclear neutrophils >10%, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The multivariate analysis identified four variables predicting mortality: bloodstream infection, shock, skin necrosis, and initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage against Aeromonas. NF caused by Aeromonas spp. revealed high mortality rates, even through aggressive surgical debridement and antibacterial therapies. Identifying those independent predictors, such as bacteremia, shock, progressive skin necrosis, monomicrobial infection, and application of the effective antimicrobial agents against Aeromonas under the supervision of infectious doctors, may improve clinical outcomes.

Subject terms: Diseases, Risk factors

Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rare and life-threatening necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSSTI) characterized by a rapid bacterial spread with soft tissue necrosis in the subcutaneous layers, particularly within superficial and deep fascia, with overall mortality rates of 12.1–76%1–8. Early fasciotomy, an appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy supported by physicians specialized in infectious disease, and aggressive intensive unit care should be initially administered in critically ill patients suffering from fulminant NF to prevent limb loss and possible death9–11.

Our hospital is situated on the western coast of southern Taiwan, and most residents are exposed to occupations related to seawater, raw seafood, fresh or brackish water, and soil. As a result, Vibrio spp. and Aeromonas spp. infections have been reported at a relatively high incidence since 2004 in our hospital9,12–19. Thus, we set up the team “Vibrio NSSTIs Treatment and Research (VTR) Group”, which consists of professional staff working in various departments, including emergency medicine, orthopedic surgery, infectious diseases, intensive care unit (ICU), and hyperbaric oxygen treatment center. Our team has successfully decreased the mortality rate of Vibrio NF from 35% to 13%8,12.

Although we have established a treatment strategy including emergency fasciotomy or amputation, antibiotic therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin plus tetracycline, and admission to the ICU for patients suspected to have fulminant necrotizing fasciitis, such as Vibrio, MRSA, and Aeromonas infections8,9,14,17,19. Aeromonas species NSSTIs were still reported with a high mortality rate ranging from 26.7% to 100%7–10,13,14,20–23.

Aeromonas species are members of the Vibrionaceae and are gram-negative, non-sporulating, facultative, anaerobic small bacilli with a ubiquitous distribution24,25. Human infections including acute gastroenteritis, blood-borne infections, trauma-related skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), and intra-abdominal infections may develop in previously healthy subjects following aqueous environmental exposure24–28. Currently, there are more than 20 Aeromonas species identified, but only seven have been recognized as human pathogens, namely, A. hydrophila, A. caviae, A. veronii biovar sobria, A. veronii biovar veronii, A. jandaei, A. trota, and A. schubertii, with the first three being the most common causes of NF24,29 The aim of this study was to evaluate the specific characteristics and the independent predictors of mortality in patients with Aeromonas NF, and to gain insight and improve future outcomes.

Results

Patients outcomes

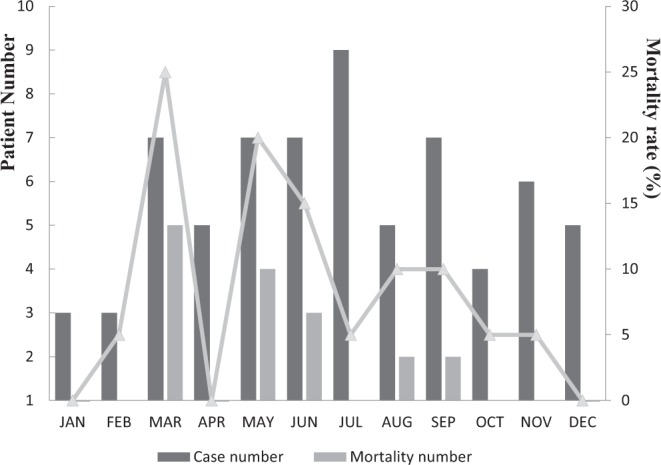

From December 2001 to November 2019, a total 68 of patients admitted to the ED were surgically confirmed to have Aeromonas NF of limbs. Forty-eight patients survived, and 20 expired with a mortality rate of 29.4%. The numbers of diagnoses, cases of death, and mortality rates are listed per month (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Monthly distribution of 68 cases of Aeromonas spp. necrotizing fasciitis of limbs in southern Taiwan.

Demographic data

No significant differences were observed within the parameters of age, gender, infective regions, or the number of amputations per patient between these two groups. The non-survival group was characterized by a significantly higher incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic liver dysfunction, and ICU admission (Table 1). Meanwhile, the non-survival group had significantly associated with higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHEa II) scores, fewer operations, and shorter hospitalization stays (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and characteristics from Aeromonas NF between survival and non-survival groups.

| Variable | Survival (n = 48) | Non-survival (n = 20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.52 ± 15.44 | 64.85 ± 12.89 | 0.274 |

| Gender, male | 40 (83.3) | 14 (70) | 0.215 |

| Involved region | |||

| Upper extremities | 12 (25) | 1 (5) | 0.056 |

| Lower extremities | 36 (75) | 19 (95) | 0.056 |

| APACHEa II score | 12.48 ± 6.65 | 23.9 ± 7.33 | <0.001* |

| Underlying chronic diseases | |||

| Alcoholism | 10 (20.8) | 7 (35) | 0.219 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12 (25) | 15 (75) | <0.001* |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (18.8) | 5 (25) | 0.561 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 5 (10.4) | 2 (10) | 0.959 |

| Viral hepatitis | 17 (35.4) | 12 (60) | 0.062 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 13 (27.1) | 9 (45) | 0.150 |

| Chronic liver dysfunction | 23 (47.9) | 16 (80) | 0.015* |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 24 (50) | 14 (70) | 0.130 |

| Malignancy | 14 (29.2) | 5 (25) | 0.727 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7 (14.6) | 4 (20) | 0.580 |

| Patients number of amputations | 12 (25) | 8 (40) | 0.216 |

| ICUb admission | 23 (47.9) | 19 (95) | <0.001* |

| TiSOc > 24 h | 15 (31.3) | 6 (30) | 0.919 |

| Number of debridement | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | <0.001* |

| ICU stay (day) | 6.4 ± 14.7 | 13.5 ± 21.1 | 0.117 |

| Hospital stay (day) | 37.9 ± 20.2 | 17.1 ± 36.8 | 0.004* |

Data were presented as mean (standard deviation) or frequency (%). *p-value <0.05. aAPACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, bICU: intensive care unit, cTiSO: time of the first surgical intervention from symptom onset to the operating room.

Microbiological analysis

Aeromonas hydrophila was the most common infectious bacteria, accounting for 46 (67.6%) of the total 68 Aeromonas NF cases, followed by 10 Aeromonas sobria cases (14.7%), 9 Aeromonas cases (13.2%), and 3 of Aeromonas caviae (4.4%). A total of 42 (61.8%) of these patients were diagnosed with polymicrobial Aeromonas NFs of limbs. The most common isolates obtained from patients with polymicrobial infections included Clostridium species (21, 50.0%), followed by Enterobacter species (14, 33.3%) and Klebsiella species (11, 26.2%) (Table 2). The non-survival group had a higher incidence of bacteremia (70% vs. 25%; p = 0.001) than the survival group, and were significantly associated with monomicrobial infection (p = 0.018). Meanwhile, the survival group had a higher incidence of polymicrobial infection and coinfection with anaerobic pathogens (p = 0.017 and p = 0.016, respectively) than the non-survival group. Concerning antibiotic resistance to Aeromonas species, only resistant to cephalosporins exhibited a statistically significant increase (40% vs. 14.6%; p = 0.021) within the non-survival group. In terms of initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage, the non-survival group had a higher incidence (45% vs. 18.8%; p = 0.025) than the survival group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of identified infectious microorganisms in 42 cases of Aeromonas polymicrobial NF of limbs.

| Identified infectious microorganisms | Total No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gram-negative aerobic pathogens | |

| Enterobacter spp. | 14 (33.3) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 13 (31.0) |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 (2.4) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 11 (26.2) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 7 (16.7) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 4 (9.5) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 (23.8) |

| Escherichia coli | 9 (21.4) |

| Proteus vulgaris | 4 (9.5) |

| Citrobacter freundii | 3 (7.1) |

| Serratia marcescens | 2 (4.8) |

| Vibrio vulnificus | 1 (2.4) |

| Morganella morganii | 1 (2.4) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 (2.4) |

| Gram-positive aerobic pathogens | |

| Enterococcus spp. | 9 (21.4) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 8 (19.0) |

| Enterococcus casseliflavus | 1 (2.4) |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 4 (9.5) |

| MRSAa | 2 (4.8) |

| MSSAb | 2 (4.8) |

| Group D Streptococcus | 1 (2.4) |

| Anaerobic pathogens | |

| Clostridium spp. | 21 (50.0) |

| Clostridium bifermentans | 9 (21.4) |

| Clostridium sp | 6 (14.3) |

| Clostridium perfringens | 3 (7.1) |

| Clostridium bifermentans | 1 (2.4) |

| Clostridium butyricum | 1 (2.4) |

| Clostridium novyi A | 1 (2.4) |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 7 (16.7) |

| Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | 4 (9.5) |

| Peptostreptococcus sp | 2 (4.8) |

| Peptostreptococcus magnus | 1 (2.4) |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 3 (7.1) |

| Prevotella sp | 3 (7.1) |

| Total | 42 (100) |

Abbreviations: aMRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

bMSSA: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 3.

Microbiological results for Aeromonas species NF between survival and non-survival groups.

| Variable | Survival (n = 48) | Non-survival (n = 20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloodstream infection | 12 (25) | 14 (70) | 0.001* |

| Bacteria isolated | 0.018* | ||

| Polymicrobial infection | 34 (70.8) | 8 (40) | |

| Monomicrobial infection | 14 (29.2) | 12 (60) | |

| Coinfection with anaerobic pathogens | 22 (45.8) | 3 (15) | 0.016* |

| Coinfection with Clostridial spp. | 17 (35.4) | 2 (10) | 0.033* |

| Antibiotics that Aeromonas spp. resistant | |||

| Penicillins | 19 (39.6) | 5 (25) | 0.252 |

| Carbapenems | 16 (33.3) | 7 (35) | 0.895 |

| Cephalosporins | 7 (14.6) | 8 (40) | 0.021* |

| Aminoglycosides | 6 (12.5) | 5 (25) | 0.202 |

| Sulfa drugs | 4 (8.3) | 5 (25) | 0.065 |

| Tetracycline | 3 (6.3) | 4 (20) | 0.089 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 1 (2.1) | 1 (5) | 0.517 |

| Other class antibiotics | 36 (75) | 17 (85) | 0.365 |

| Initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage | 9 (18.8) | 9 (45) | 0.025* |

Clinical presentations

No significant differences in the presentation of fever (>38 °C); tachycardia (heartbeat >100/min); or erythematous, swollen, and painful lesion were observed between the two groups (Table 4). However, the proportion of patients in the non-survival versus survival group presenting with tachypnea (respiratory rate >20/min, 70.0% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.014), shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, 80.0% vs. 29.2%; p < 0.001), hemorrhagic bullae (60.0% vs. 29.2%, p = 0.017), and skin necrosis (55.0% vs. 16.7%, p = 0.001) were higher (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical presentations between survival and non-survival groups.

| Variable | Survival (n = 48) | Non-survival (n = 20) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic symptoms/signs | ||||

| Fever (>38 °C) | 15 (31.3) | 5 (25) | 0.606 | |

| Tachycardiaa | 27 (56.3) | 15 (75) | 0.147 | |

| Tachypneab | 18 (37.5) | 14 (70) | 0.014* | |

| Shockc | 14 (29.2) | 16 (80) | <0.001* | |

| Limbs symptoms/signs | ||||

| Pain and tenderness | 47 (97.9) | 20 (100) | 0.516 | |

| Swelling and erythema | 45 (93.8) | 20 (100) | 0.253 | |

| Hemorrhagic bullae | 14 (29.2) | 12 (60) | 0.017* | |

| Skin necrosis | 8 (16.7) | 11 (55) | 0.001* | |

Data were presented as mean (standard deviation) or frequency (%). aTachycardia: heart beat >100/min, bTachypnea: respiratory rate >20/min, cShock: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg.

Laboratory findings

Within the non-survival group the following characteristics were observed more frequently than within the survival group: total white blood cell count <4000/uL, band leukocyte cells >10%, lymphocyte count of leukocytes <1000/uL, anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <15 × 104/uL), and estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 c.c./min (Table 5). In addition, the proportion of patients presenting with a lower albumin level was frequently observed and significantly higher in the non-survival group (p = 0.002). The prothrombin time (PT) and total bilirubin values for the non-survival group were significantly higher than those for the survival group (Table 5).

Table 5.

Laboratory findings of patients with Aeromonas NF between survival and non-survival groups.

| Variable | Survival (n = 48) | Non-survival (n = 20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total WBCa count | |||

| Leukocytosis (≧12000/uL) | 28 (58.3) | 6 (30) | 0.033* |

| Leukopenia (≦4000/uL) | 2 (4.2) | 6 (30) | 0.003* |

| Leukocytosis or Leukopenia | 30 (62.5) | 12 (60) | 0.847 |

| Differential count | |||

| Neutrophilia (>7500/uL) | 38 (79.2) | 9 (45) | 0.005* |

| Band forms (>10%) | 7 (14.6) | 8 (40) | 0.021* |

| Lymphocytopenia (<1000/uL) | 21 (43.8) | 15 (75) | 0.019* |

| Anemia (Hbb <10 g/dL) | 11 (22.9) | 12 (60) | 0.003* |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelet counts <15 × 104/uL) | 20 (41.7) | 16 (80) | 0.004* |

| eGFRc < 30 c.c./min | 9 (18.8) | 14 (70) | <0.001* |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 191.0 ± 116.6 | 190.3 ± 116.2 | 0.983 |

| Sodium (meq/L) | 137.4 ± 4.4 | 135.1 ± 5.9 | 0.077 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 111.9 ± 103.8 | 146.0 ± 163.6 | 0.336 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.002* |

| PTd (s) | 13.1 ± 3.3 | 19.5 ± 7.5 | <0.001* |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 6.2 ± 5.4 | <0.001* |

Data were presented as mean (standard deviation) or frequency (%). Abbreviations: aWBC: white blood cell; bHb: hemoglobin; ceGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; dPT: prothrombin time.

Multivariate analysis

As determined by multivariate analysis, patients presented with bloodstream infection (OR: 8.741; 95% CI: 1.936–39.476; p = 0.005), shock(OR: 5.926; 95% CI: 1.254–28.006; p = 0.025), skin necrosis (OR: 4.575; 95% CI: 1.190–17.597; p = 0.027), and a higher incidence of initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage (OR: 5.798; 95% CI: 1.247–26.951; p = 0.025) were the indicators of mortality (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate regression for the non-survival group from 68 cases of Aeromonas NF patients about microbiological results and clinical presentations.

| ORa (95% CIb) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiological results | ||

| Bloodstream infection | 8.741 (1.936–39.476) | 0.005* |

| Aeromonas spp. polymicrobial infection | 0.610 (0.136–2.726) | 0.517 |

| Coinfection with anaerobic pathogens | 0.518 (0.039–6.958) | 0.620 |

| Coinfection with Clostridial spp. | 1.151 (0.061–21.699) | 0.925 |

| Aeromonas spp. resistant to cephalosporins | 2.679 (0.635–11.296) | 0.180 |

| Initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage | 5.798 (1.247–26.951) | 0.025* |

| Systemic symptoms/signs | ||

| Tachypnea | 1.635 (0.374–7.155) | 0.514 |

| Shock | 5.926 (1.254–28.006) | 0.025* |

| Limbs symptoms/signs | ||

| Hemorrhagic bullae | 1.578 (0.414–6.011) | 0.504 |

| Skin necrosis | 4.575 (1.190–17.597) | 0.027* |

Abbreviations: aOR, odds ratio; bCI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Most Aeromonas SSTIs are associated with environmental exposure and are particularly related to traumatic occupational injuries or unexpected contact via recreational sporting activities27,28. This mode of acquisition results in soft tissue Aeromonas infections occurring more commonly during the summer season25. Our study was consistent with this finding.

Aeromonas SSTIs are often polymicrobial and frequently involve coinfections with other gram-negative rods or Clostridium species25,27,30. In studies of Aeromonas SSTIs or bacteremia, A. hydrophila was the most common pathogen isolated, and encompassed 47~69% Aeromonas infections26,27,29. In our results, A. hydrophila was also the most common infectious organism detected (67.6%), and Clostridium species were the most common coinfection pathogens.

According to past reports, Aeromonas and Clostridial necrotizing soft tissue infections were consistently associated with poor outcomes7,19,31. However, our patients exhibiting monomicrobial Aeromonas NF had a significantly higher mortality rate than those with polymicrobial Aeromonas NF. Another interesting phenomenon is that Aeromonas NF patients coinfected with Clostridial species also had better outcomes. On the other hand, we found Aeromonas NF combined with bloodstream infection (BSI) had significantly increased the mortality rate. Monomicrobial Aeromonas NF with bacteremia has commonly been reported to be associated with liver cirrhosis and malignancy that can rapidly impair the phagocytic activity of the reticuloendothelial system and result in septic shock and multiple organ failure14,27,32. Thus, we should pay more attention and aggressive treat those NF patients with Aeromonas bacteremia and monomicrobial infection.

Most Aeromonas strains are resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, and amoxicillin–clavulanate, whereas most are susceptible to sulfa drugs, fluoroquinolones, second- to fourth-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, and tetracyclines26,28,33,34. Therefore, Aeromonas SSTIs may best be treated empirically with fluoroquinolones and/or a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin or a carbapenem; however, a higher cephalosporins-resistance rate was found in the non-survival group (Table 3). Culture-directed antimicrobial therapy should be aggressively administered in such Aeromonas NF patients to avoid delayed use of appropriate antimicrobial therapy11,13.

A significantly higher mortality rate was observed in NF patients that also exhibited CKD, hepatic dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, and cancer3,6,7,10,19,20,26. Our Aeromonas NF patients with CKD or chronic hepatic dysfunction were present in statistically significantly higher numbers in the non-survival compared with the survival group. The non-survival group exhibited high severity of disease and 95% of patients required admission to the ICU. A delay in the first surgical intervention from symptom onset to the operating room of >24 h, as well as having advanced age, adversely affected survival outcome3,20,26. A delay in surgery of more than 24 h accounted for 30% of the patients within the non-survival group, and the mean age was >60 years old within these two groups.

In our study, the non-survival group contained a greater proportion of patients with hemorrhagic bullous lesions (60% vs. 29.2%) and skin necrosis (55% vs. 16.7%) than the surviving group, but multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that non-survival patients presented associated with skin necrosis (p = 0.027). As the ischemic necrosis of the skin evolves, gangrene of the subcutaneous fat, dermis, and epidermis, manifesting progressively as bullae formation, ulceration and skin necrosis14,35. Hemorrhagic bullae and skin necrosis were also the late stage signals of necrotizing fasciitis3,35,36. Then, hemorrhagic bullae with skin necrosis appearance may increase the incidence of mortality (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, the emergence of hemorrhagic bullae would be considered a feature and an early independent predictor of mortality of Aeromonas NF.

Figure 2.

A 82 year-old male with a history of hepatitis B and old stroke had right low leg and foot pain on second day after a contused injury of toes. The right lower leg revealed patchy purpura, vesicles and skin necrosi with serous fluid soaking on the bed in the emergency room. After fasciotomy, the culture of blood and wound specimens confirmed Aeromonas hydrophila, however, this patient died on the 3rd day after admission owing to progressive septic shock and multiple organ failure.

In this study, the non-survival group exhibits a statistical tendency to have tachypnea and initially present with septic shock more than those within the survival group in univariate logistic analysis; however, multivariate logistic regression analysis bacteremia and shock revealed significant differences. Some literatures reported that initial presentations of tachypnea and hypotensive shock were also predictors for a poor outcome in NF patients7,8,10,19. This may explain to the fact that the death group presented more septicemia-related systemic inflammatory response symptoms to induce respiratory failure and shock.

Leucopenia, increased counts of banded leukocytes, thrombocytopenia, and severe hypoalbuminemia can be considered the clinical and laboratory risk indicators to initialize surgical intervention and to predict mortality for NF3–8,15,20,21. The non-survival group was associated with a higher rate of patients exhibiting leucopenia, leukocyte band cells >10%, lymphocytopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia compared with the survival group (Table 5). Lower serum albumin levels, prolonged PT, and higher total bilirubin levels were also noted within the non-survival group. These laboratory findings within Aeromonas NF infections are compatible with the aforementioned previous studies.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed the initial ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage are related to poor outcomes for Aeromonas NF patients. Early prompt fasciotomy combined with appropriate antimicrobial therapy has been aggressively performed for patients highly suspected of having NF in our institution8,13,14,17,19. In our experience within the ICU, antimicrobial stewardship program and on-the-spot education by physicians specialized in infectious disease can potentially decrease sepsis-related and overall infection-related mortality rates by 54% and 41%, respectively11. The initial clinical presentation of Aeromonas NF is very similar to Vibrio NF, and especially within southern Taiwan, there may be a history of contact with dirty water or fish exposure. To treat these fulminate diseases, third- to fourth-generation cephalosporins combined with tetracycline or fluoroquinolones were commonly the empiric prescription before the infectious pathogens were identified5,37. In the non-survival group, we found 40% of Aeromonas species resistant to cephalosporins and 20% to tetracycline but only to 5% fluoroquinolones. So, we consider prescribing third- to fourth-generation cephalosporins combined with tetracycline and fluoroquinolones for highly suspected fulminate Vibrio or Aeromonas NF of limbs within the setting of our hospital. After the pathogens were identified, the antibiotic regimens were adjusted as necessary according to the patient’s clinical condition and results of the antibiotics drug sensitivity tests.

The present study was limited by having only 68 patients in a period of 18 years. However, to our knowledge, these are the largest patient numbers within such a study that can be currently found within PubMed. Another limitation contained within is that due to the long study period, some cases, medical records, and laboratory data had been lost and were not able to be recovered.

In conclusion, Aeromonas spp. NF of limbs is very rare and exhibits resistance to multiple antibiotics. NF caused by Aeromonas spp. revealed high mortality rates, even through aggressive surgical debridement and antibacterial therapies. Identifying those independent predictors, such as bacteremia, shock, progressive skin necrosis, monomicrobial infection, and application of the effective antimicrobial agents against Aeromonas under the supervision of infectious doctors, may improve clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This is a retrospective study performed by the VTR Group at CGMH-Chiayi from December 2001 to November 2019. We analyzed those patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) that were diagnosed with NF of limbs with undergoing surgical intervention, and a total 68 of patients were surgically and pathologically confirmed to have Aeromonas NF of limbs were included.

Definitions

Patients with Aeromonas NF of limbs were enrolled in the study using the following criteria: (1) NF was defined either through histopathologic or surgical findings, such as the presence necrosis of the skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial fascia, or underlying muscles; (2) Aeromonas spp. was detected via isolation from soft tissue lesions and/or blood collected immediately after a patient’s arrival at the ED or during surgery; and (3) these bacteria infected any limb3,6,17,22.

Monomicrobial infection was documented by isolating single pathogenic bacteria as described above in criteria (2)6,17. Polymicrobial infections were documented in patients from whom Aeromonas isolates in addition to other bacterial pathogens were isolated from soft tissue lesions and/or blood samples. Ineffective empirical antimicrobial usage was defined as the administration of antimicrobial regimens that may be ineffective against Aeromonas isolates according to antimicrobial susceptibility testing when patients arrived ED11,23.

Microbiology laboratory procedures

Gram-negative isolates that tested positive for cytochrome oxidase, glucose fermentation, citrate usage, indole production, and ornithine decarboxylase were classified as Aeromonas species. All strains were identified to the species level by conventional methods and were further verified by the API-20E and ID 32 GN Systems (bioMérieux Inc., Hazelwood, MO, USA), or the Vitek 2 ID-GNB identification card (bioMérieux Inc., Durham, NC, USA). These antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), and the results were interpreted according to the CLSI criteria for these microorganisms.

Demographic data, clinical presentations, and laboratory findings

Patients with Aeromonas NF of limbs were categorized within survival and non-survival groups. Data such as demographics, comorbidities, presenting signs and symptoms, laboratory findings, microbiologic results, initial antibiotics usage, and treatment outcomes were recorded and compared.

Accordance

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All participants provided their written informed consent following the protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation. In accordance to the ethical approval, consents were not required from deceased patients’ relatives.

Statistical analysis

The predictors for mortality were determined using a multivariate logistic regression model. Categorical variables were tested by Fisher’s exact test, continuous variables were tested by Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, and a two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the strength of any association, as well as the precision of the estimated effect. All statistical calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, version 18.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation (Number: 201801530B1B0).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Miss Hsing-Jung Li for assistance in English modification. This work was supported by the Chang Gung Medical Research Program Foundation [grant numbers CMRPG6H0641].

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.Y.H. and K.T.P.; Investigation and Methodology, T.Y.H. and W.H.H.; Formal analysis, T.Y.H. and C.H.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, T.Y.H. and F.Y.C.; Writing—review and editing, T.Y.H. and Y.H.T. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All datasets are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilsonm B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am. Surg. 1952;18:416–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Raffin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110:219–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong CH, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2003;85:1454–60. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward RG, Walsh MS. Necrotizing fasciitis: 10 years’ experience in a district general hospital. Br. J. Surg. 1991;78:488–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu JW, et al. Prognostic factors and antibiotics in Vibrio vulnificus septicemia. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:2117–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CY, et al. Prognostic factors and monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis: gram-positive versus gram-negative pathogens. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang KF, et al. Independent predictors of mortality for necrotizing fasciitis: A retrospective analysis in a single institution. J. Trauma. 2011;71:467–73. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318220d7fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai YH, et al. Microbiology and surgical indicators of necrotizing fasciitis in a tertiary hospital of southwest Taiwan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;16:e159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai YH, et al. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections and sepsis caused by Vibrio vulnificus compared with those caused by Aeromonas species. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2007;89:631–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200703000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CC, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: Predominance of monomicrobial Gram-negative bacillary infections. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;62:219–25. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang TY, et al. Implementation and outcomes of hospital-wide computerized antimicrobial approval system and on-the-spot education in a traumatic intensive care unit in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018;51:672–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai YH, et al. Systemic Vibrio infection presenting as necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis. A series of thirteen cases. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2004;86:2497–502. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200411000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai YH, Hsu RWW, Huang KC, Huang TJ. Comparison of necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis caused by Vibrio vulnificus and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2011;93:274–84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai YH, et al. Monomicrobial Necrotizing Fasciitis Caused by Aeromonas hydrophila and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015;24:416–23. doi: 10.1159/000431094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai YH, et al. Laboratory indicators for early detection and surgical treatment of Vibrio necrotizing fasciitis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010;468:2230–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1311-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang KC, Hsu RW. Vibrio fluvialis hemorrhagic cellulitis and cerebritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40:75–7. doi: 10.1086/429328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang KC, et al. Vibrio necrotizing soft-tissue infection of the upper extremity: factors predictive of amputation and death. J. Infect. 2008;57:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen WD, et al. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 - the first reported case of keratitis in a healthy patient. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19:916. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen IC, et al. The microbiological profile and presence of bloodstream infection influence mortality rates in necrotizing fasciitis. Crit. Care. 2011;15:R152. doi: 10.1186/cc10278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu YM, et al. Microbiology and factors affecting mortality in necrotizing fasciitis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2005;38:430–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JM, Lim HK. Necrotizing fasciitis: eight-year experience and literature review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;18:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai YH, et al. A multiplex PCR assay for detection of Vibrio vulnificus, Aeromonas hydrophila, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus agalactiae from the isolates of patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;81:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunin CM, Tupasi T, Craig WA. Use of antibiotics. A brief exposition of the problem and some tentative solutions. Ann. Intern. Med. 1973;79:555–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-4-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold WL, Salit IE. Aeromonas hydrophila infections of skin and soft tissue: report of 11 cases and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993;16:69–74. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko WC, Chuang YC. Aeromonas bacteremia: Review of 59 episodes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;20:1298–304. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chao CM, et al. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by Aeromonas species. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;32:543–7. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1771-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamy B, Kodjo A, Laurent F. Prospective nationwide study of Aeromonas infections in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:1234–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00155-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janda JM, et al. Aeromonas species in septicemia: Laboratory characteristics and clinical observations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994;19:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon TP, Rajakulendran S, Yeung HT. Acute hepatic failure precipitated in a patient with subclinical liver disease by vibrionic and clostridial septicemia. Pathology. 1998;20:188–90. doi: 10.3109/00313028809066632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anaya, D.A. et al. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Arch Surg140, 151–7; discussion 8 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ko WC, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic implications of 104 episodes of monomicrobial Aeromonas bacteraemia. J. Infect. 2000;40:267–73. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vila J, et al. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of Aeromonas caviae, Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas veronii biotype sobria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002;49:701–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aravena-Roman M, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Aeromonas strains isolated from clinical and environmental sources to 26 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1110–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05387-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong CH, Wang YS. The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2005;18:101–6. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000160896.74492.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McHenry CR, et al. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Ann. Surg. 1995;221:558–63. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199505000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuang YC, et al. Vibrio vulnificus infection in Taiwan: report of 28 cases and review of clinical manifestations and treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996;15:271–276. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets are available from the first author on reasonable request.