Abstract

Introduction

Foot and ankle injuries in elite athletes can result in decreased performance, absence from sport and prolonged morbidity. There is paucity of data on foot and ankle injuries in Olympics athletes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the PubMed and EMBASE databases. Studies in English language that reported the incidence and/or prevalence of foot and ankle injuries in during Olympics games (summer, winter and youth Olympics) were included. Studies in languages other than English, those that looked at injuries other than foot and ankle injuries, studies looking at injuries in non-Olympics events and those looking at Olympics trials were excluded. We determined the injury rates and burden of foot and ankle injuries. We also looked at the patterns and trends of foot and ankle injuries.

Results

A total of 399 foot and ankle injuries from 25 publications were included in the review. Foot and ankle injury rates ranged from 0.09 to 0.42 injuries per athlete-years for summer Olympics and 0.02–0.35 injuries per athlete-years for winter Olympics. Quantitative analysis revealed that foot and ankle injuries contributed to 16.9% of all injuries (95% CI 8.1–31.9%) for summer Olympics and 5.1% of all injuries (95% CI 1.9–12.6%) for winter Olympics; however, a high statistical heterogeneity was noted. The three most common injuries were tendon injuries, ligament injuries and stress fractures. The rates and burden of foot and ankle injuries showed a declining trend.

Conclusions

Foot and ankle injuries are an important cause of morbidity amongst Olympics athletes. The declining trend amongst these injuries notwithstanding, there is a need for a global electronic database for reporting of injuries in Olympics athletes.

Keywords: Olympics, Foot and ankle, Injuries, Meta-analysis, Sport, Injury prevention

Introduction

The modern Olympics games are considered as the pinnacle of all sporting events and participation has steadily increased ever since their inception in 1896. As is the case with any mass sporting event, sport-related injuries are a major concern, both for the athletes as well as the organizers [1–3]. It has been shown that foot and ankle injuries can affect athletic performance adversely, result in absence from sport and can also have long-term impact on the athletes’ well-being [4–6]. However, data on foot and ankle injuries in Olympics athletes is scarce. Hence, this study was done to determine the patterns and trends of foot and ankle injuries in Olympic athletes.

Methods

This was a systematic review and meta-analysis, and was done in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [7].

Search Strategy

The primary search was conducted on the PubMed and EMBASE databases, using a well-defined search strategy that was formulated a-priori (Table 1). For secondary search, references of included studies and relevant review articles identified from the primary search were explored.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| S. no. | Search string | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | PubMed—search period: from inception—05/12/2019 | |

| (olympics[All Fields] OR olympic[All Fields]) AND ("wounds and injuries"[MeSH Terms] OR ("wounds"[All Fields] AND "injuries"[All Fields]) OR "wounds and injuries"[All Fields] OR "injury"[All Fields]) | 792 | |

| 2 | EMBASE—search period: from inception—05/12/2019 | |

| ‘olympics'/exp OR ‘olympics' AND ‘injury’ | 210 | |

| Total | 1002 | |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies in English language that reported the incidence and/or prevalence of foot and ankle injuries in during Olympics games (summer, winter and youth Olympics) were included. Studies in languages other than English, those that looked at injuries other than foot and ankle injuries, studies looking at injuries in non-Olympics events and those looking at Olympics trials were excluded.

Study Selection

Selection of studies for inclusion into the review was done independently by two authors (SS and RR). The titles and abstracts were screened initially and full-texts were subsequently obtained to assess eligibility for inclusion into the review. All discrepancies were resolved by mutual agreement.

Data Extraction

Data was extracted from the included studies by three authors (SS, PK and RR); the following parameters were recorded: (a) country and year of publication (b) total number of athletes included (c) total number of injuries reported (d) total foot and ankle injuries reported (e) age and sex distribution (f) sport-wise distribution (g) specific types of foot and ankle injuries.

Estimation of Injury Rates and Burden of Foot and Ankle Injuries

The incidence rate (IR) for injuries was determined as injuries per athlete-years and was calculated by the following formula:

To ensure uniformity in calculation of IR, the total number of athletes in each Olympic study period was determined from official data provided by the International Olympic Federation. The study period used in the denominator was the period of Olympics games reported by the study authors, if the period was not reported, it was determined from official data provided by the International Olympics Federation.

Incidence rates were calculated for (i) all injuries and (ii) foot and ankle injuries separately. The burden of foot and ankle injuries was calculated from the percentage of foot and ankle injuries (as a function of all injuries) during the study period.

Analysis

Both qualitative and quantitative analyses were performed. For quantitative analysis, appropriate tables and diagrams were constructed. For quantitative analysis, a random-effects model was used and pooled rates of injuries in summer and winter Olympics were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 test.

Injury Trends

Line graphs were used to study the trends of overall injury rates, foot and ankle injury rates and percentage of foot and ankle injuries.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias in the included studies was assessed independently by two observers (SS and RR) using the NIH case series tool [8]. The tool consists of 14 items, which was adapted for this review. Discrepancies were resolved by mutual agreement.

Results

Search Results

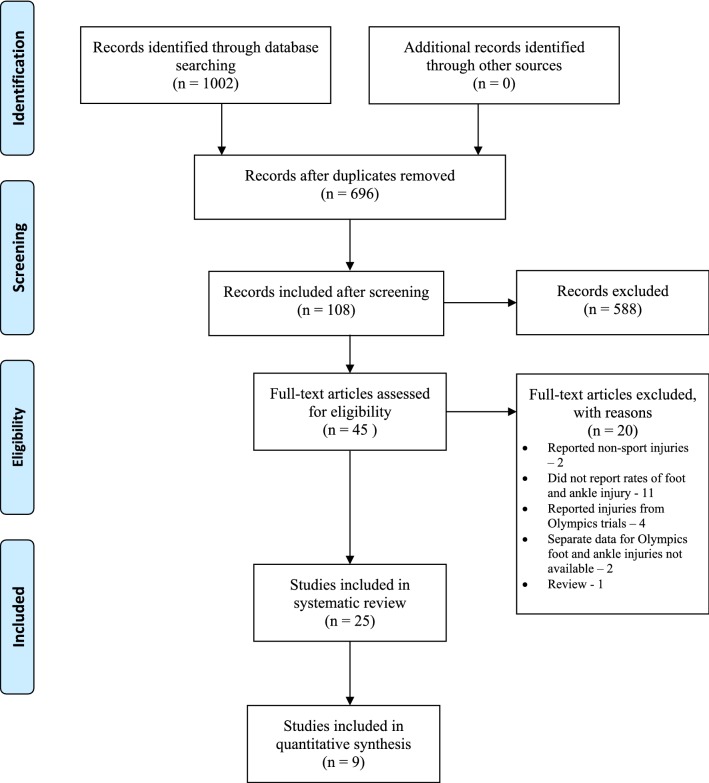

The results of search have been summarized as per the PRISMA flow diagram (Table 2). A total of 1002 records were identified from the searches; 46 full-text articles were obtained and 25 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review.

Table 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for the study

Characteristics of Studies Included

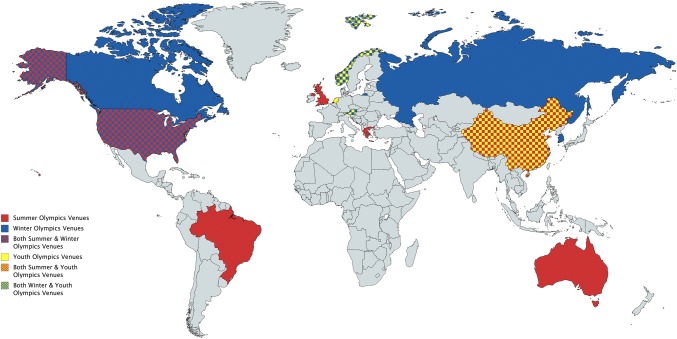

Of the 25 studies included, 13 looked at reported on injuries during summer Olympics, 7 during winter Olympics and 4 during youth Olympics (Fig. 1). Whereas the vast majority (n = 22) of the studies reported on injuries in a single Olympics games period, one study each reported on injuries during two, three and four Olympic games periods. 18 studies reported injuries in all types of sports, whereas 7 studies reported injuries in individual sports only (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Venues of Olympics games included in the study

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in the review

| S. no. | Characteristic | No. of studies (%age) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Olympic venues (and years) | |

| Summer | 13 | |

| 1996 (Atlanta) | 1 | |

| 2000 (Sydney) | 1 | |

| 2004 (Athens) | 3* | |

| 2008 (Beijing) | 3* | |

| 2012 (London) | 3* | |

| 2016 (Rio) | 7* | |

| Winter | 7 | |

| 1976 (Innsbruck) | 1 | |

| 1994 (Lillehammer) | 1 | |

| 2002 (Salt Lake City) | 1 | |

| 2010 (Vancouver) | 1 | |

| 2014 (Sochi) | 1 | |

| 2018 (Pyeongchang) | 2* | |

| Youth | 4 | |

| 2013 EYOF (Utrecht) | 1 | |

| 2014 (Nanjing) | 1 | |

| 2015 EYOF (Vorarlberg, Lichtenstein) | 1 | |

| 2016 (Lillehammer) | 1 | |

| 2. | Types of sports studied | |

| All summer Olympics sports | 8 | |

| All winter Olympics sports | 6 | |

| All youth Olympics sports | 4 | |

| Individual Sports | 7 | |

| Alpine Skiing (Slalom) | 1 | |

| Football | 1 | |

| Gymnastics | 1 | |

| Rugby | 1 | |

| Water Polo | 1 | |

| Wrestling | 1 | |

| Taekwondo | 1 |

Injury Rates and Burden of Foot and Ankle Injuries in Summer Olympics

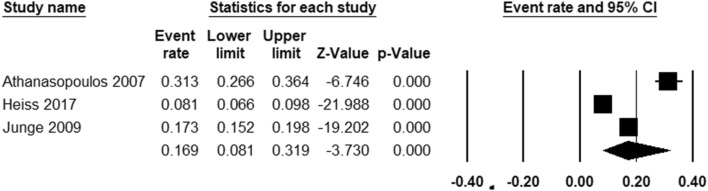

Eight studies [6, 9–15] reported on injuries in all summer Olympics sports (Table 4). Of these, 5 studies were deemed unsuitable for calculation of injury rates. Crema et al. [10] studied only muscle injuries, Elias et al. [11] studied only plantar fascia and Achilles tendon injuries, Hayashi et al. [15] studied only bone stress injuries, Jaraya et al. [12] studied only tendon abnormalities and Keim et al. [14] reported injury data from a single center. Hence, 3 studies [6, 9, 13] were used to calculate the overall injury rates and foot and ankle injury rates in summer Olympics. The overall injury rate in summer Olympics ranged from 0.4 to 2.4 injuries per athlete-years. The foot and ankle injury rate in summer Olympics ranged from 0.09 to 0.42 injuries per athlete-years. Pooled analysis of injury rates was not done, as the total number of athletes included in study was not thought to be an accurate reflection of all athletes participating in the Olympics, and was, therefore, deemed likely to affect the results. Meta-analysis revealed that foot and ankle injuries contributed to 16.9% of all injuries (95% Confidence Intervals, 8.1–31.9%) (Fig. 2). However, the I2 test revealed very high heterogeneity (98.1%).

Table 4.

Studies that included all Summer Olympics sports

| S. no. | Authors | Olympics year | Venue | Total Athletes in the Olympics period | Total injuries | Total foot and ankle Injuries | % age of foot and ankle injuries | Injury rate—overalla | Injury rate—foot and anklea | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Athanasopoulos et al. [9] | 2004 | Athens | 10,625 | 342 | 107 | 31.28 | 0.40 | 0.13 | Data gathered prospectively from athletes attending physiotherapy services at Olympics Polyclinic |

| 2 | Crema et al. [10] | 2016 | Rio | 11,274 | 81 | 2 | 2.50 | Not calculated | Not calculated | Data gathered from Radiology Information System and PACS at Olympics Village. Only muscle injuries included |

| 3 | Elias et al. [11] | 2012 | London | 10,568 | 21 | 21 | Not Applicable | Not calculated | Not calculated | Retrospective analysis of plantar fascia and achilles tendon injuries only |

| 4 | Hayashi et al. [15] | 2016 | Rio | 11,274 | 1101 | 6 | 0.54 | Not calculated | Not calculated | Data gathered retrospectively from Radiology Information System and PACS at Olympics Village. Only bone stress injuries included |

| 5 | Heiss et al. [6] | 2016 | Rio | 11,274 | 1101 | 89 | 8.1 | 1.09 | 0.09 | Data gathered retrospectively from MRI services at Olympics Village |

| 6 | Jarraya et al. [12] | 2016 | Rio | 11,274 | 1101 | 20 | 1.8 | Not calculated | Not calculated | Data gathered retrospectively from imaging services at Olympics Village. only tendon injuries included |

| 7 | Junge et al. [13] | 2008 | Beijing | 10,997 | 1055 | 183 | 17.35 | 2.41 | 0.42 | Prospective injury surveillance study by the IOC |

| 8 | Keim and Williams [14] | 1996 | Atlanta | 10,318 | 31 | 5 | 16.13 | Not calculated | Not calculated | Retrospective review on Olympics athletes presenting to a single medical facility |

aInjury rates as expressed as the number of injuries per athlete-years

Fig. 2.

Pooled analysis of percentage of foot and ankle injuries in Summer Olympics

Injury Rates in Winter Olympics

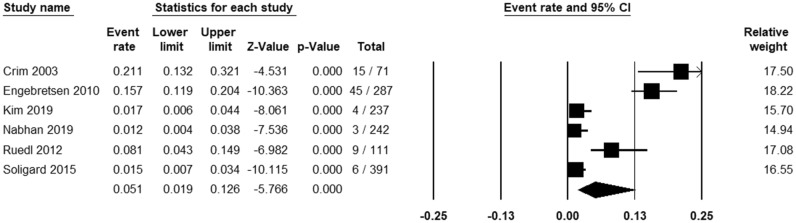

Six studies [16–21] reported on injury rates in all Winter Olympics sports (Table 5). The overall injury rates in winter Olympics ranged from 0.74 to 2.81 injuries per athlete-years. The foot and ankle injury rate in winter Olympics ranged from 0.02 to 0.35 injuries per athlete-years. As was the case with studies looking at summer Olympics, pooled analysis of injury rates was not done, as the total number of athletes included in study was not thought to be an accurate reflection of all athletes participating in the Olympics. Meta-analysis revealed that foot and ankle injuries contributed to 5.1% of all injuries (95% Confidence Intervals 1.9–12.6%) (Fig. 3). However, the I2 test revealed very high heterogeneity (92.9%).

Table 5.

Studies that included all Winter Olympics sports

| Authors | Olympics year | Venue | Total athletes in the Olympics Period | Total injuries | Total foot and ankle injuries | % age of foot and ankle Injuries | Injury rate—overall* | Injury rate—foot and ankle* | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crim [16] | 2002 | Salt Lake City | 2399 | 71 | 15 | 21.1% | 0.74 | 0.16 | Retrospective review of records |

| Engebretsen et al. [17] | 2010 | Vancouver | 2417 | 287 | 45 | 15.7% | 2.24 | 0.35 | Prospective surveillance study |

| Kim et al. [18] | 2018 | PyeongChang | 1639 | 237 | 4 | 16.9% | 2.09 | 0.04 | Retrospective review of athletes EMRs presenting to Olympics Polyclinic |

| Nabhan et al. [19] | 2018 | PyeongChang | 242 | 32 | 3 | 9.4% | 0.16 | 0.02 | Prospective observational study, covered US Olympics team only |

| Ruedl et al. [20] | 2012 | Innsbruck | 1021 | 111 | 9 | 8.1% | 3.39 | 0.27 | Prospective injury surveillance study by the IOC |

| Soligard [21] | 2014 | Sochi | 2780 | 391 | 6 | 1.5% | 3.52 | 0.05 | Prospective injury surveillance study |

aInjury rates as expressed as the number of injuries per athlete-years

Fig. 3.

Pooled analysis of percentage of foot and ankle injuries in Winter Olympics

Studies that Included Individual Olympics Sports

Seven studies looked at injuries in individual Olympics sports [22–28]. Of all these, Taekwondo was found to have the highest percentage of foot and ankle injuries (52.1%) [22], followed by Gymnastics (42%) [23] and Alpine skiing (33.3%) [24]. Wrestling had the lowest percentage of foot ankle injuries (3.1%) [28].

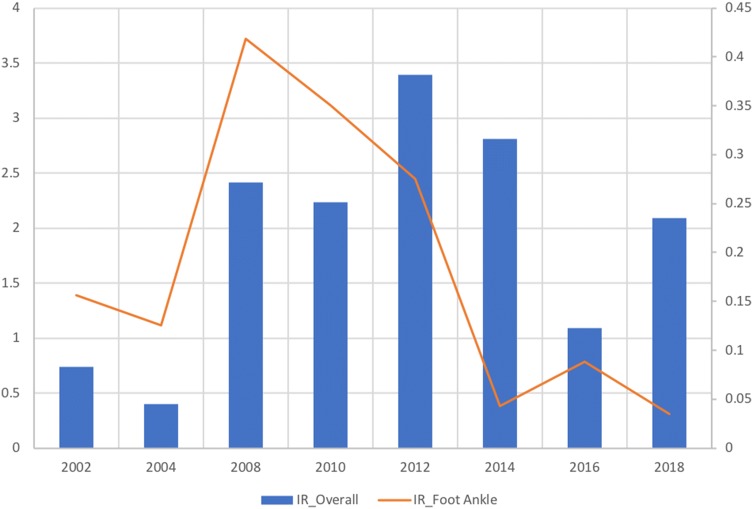

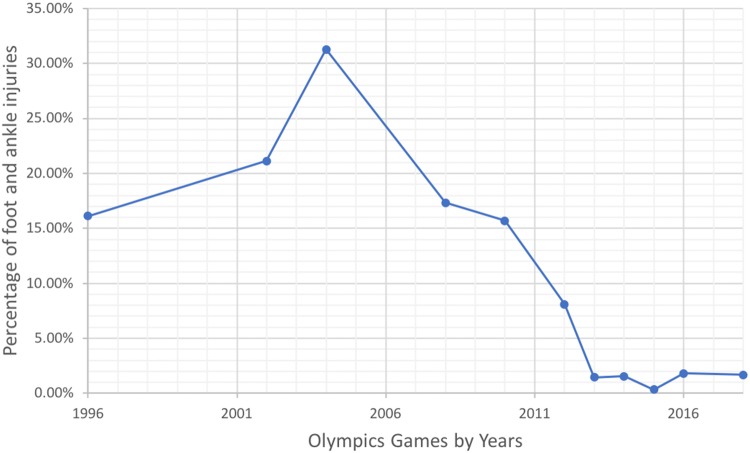

Injury Trends

Trends for injury rates could be determined from 2002 to 2018. No definite trend was observed in the overall injury rates. However, it was observed that the foot and ankle injury rates peaked in 2008 and steadily declined thereafter (Fig. 4). Trends for burden of foot and ankle injuries could be determined from 1996 to 2018. It was observed that the percentage of foot and ankle injuries peaked in 2004 and steadily declined thereafter (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Trends of overall and foot and ankle injury rates in Olympics from 2002 to 2018

Fig. 5.

Trends of percentage of foot and ankle injuries in Olympics from 1996 to 2018

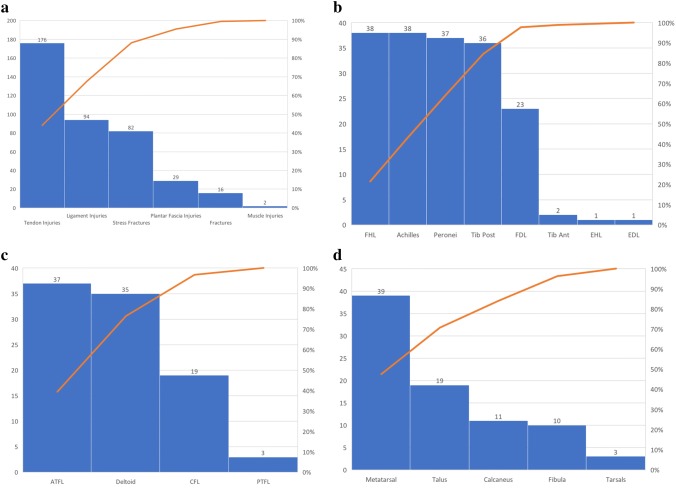

Patterns of Foot and Ankle Injuries

A total of 399 foot and ankle injuries were identified in this study. Of all the foot and ankle injuries tendon injuries (n = 176, 44%), ligament injuries (n = 94, 24%) and stress fractures (n = 82, 21%) were the three most common foot and ankle injuries (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Pareto chart of foot and ankle injuries in the study. a Patterns of all foot and ankle injuries. b Patterns of tendon injuries. c Patterns of ligament injuries. d Patterns of stress fractures

Of all the tendon injuries, injuries to the Achilles tendon and flexor hallucis longus tendon were most common (n = 38, 21.6%), followed by peroneal (longus and brevis) tendon (n = 37, 21%) and tibialis posterior tendon (n = 36, 20.5%) injuries. Acute fractures accounted for approximately 4% of all injuries (Fig. 6b).

Of all the ligament injuries, injuries to the anterior talofibular ligament (n = 37, 39.4%) were most common, followed by deltoid (n = 35, 37.2%) and calcaneofibular (n = 19, 20.2%) ligament injuries (Fig. 6c).

Of all the stress fractures, those involving the metatarsal bones (n = 39, 47.6%) were most common, followed by those involving the talus (n = 19, 23.2%) and calcaneus (n = 11, 13.4%) bones (Fig. 6d).

Risk of Bias Assessment (Table 6)

Table 6.

Studies that included individual Olympics sports

| Authors | Olympics year | Venue | Sport | Total Injuries | Total foot and ankle injuries | % age of foot and ankle injuries | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altarriba-Bartes et al. [22] | 2000, 2004 | Sydney, Athens | Taekwondo | 48 | 25 | 52.08 | Cross-sectional retrospective study covering two Olympics periods |

| Edouard et al. [23] | 2008, 2012, 2016 | Beijing, London, Rio | Gymnastics | 81 | 34 | 41.98 | Prospective study covering three Olympics periods |

| Ekeland et al. [24] | 1994 | Lillehammer | Alpine Skiing/Slalom | 3 | 1 | 33.33 | Cross-sectional study |

| Fuller et al. [25] | 2016 | Rio | Rugby | 23 | 4 | 17.39 | Prospective cohort study |

| Junge et al. [26] | 1998–2001 | Sydney | Football | 148 | 21 | 14.19 | Prospective injury surveillance study covering FIFA tournaments and Sydney Olympics |

| Mountjoy et al. [27] | 2004–2016 | Athens, Beijing, London, Rio | Water Polo | 126 | 5 | 3.97 | Prospective injury surveillance study covering 4 Olympics games and 4 FINA world championships |

| Shadgan et al. [28] | 2008 | Beijing | Wrestling | 32 | 1 | 3.13 | Prospective injury surveillance study |

Of the 25 studies included in the review, 13 were rated as Good and 8 as Fair as per the NIH case series tool. 4 studies were deemed as Poor as the study authors felt that they were not representative of an ideal Olympics cohort. Of these, Crema et al. [10] studied only imaging detected muscle injuries, Elias et al. [11] studied only plantar fascia and Achilles tendon injuries, Jarraya et al. [12] studied only tendon injuries and Hayashi et al. [15] studied only bone-stress injuries.

Discussion

Foot and ankle injuries in elite athletes can be devastating, and can often result in prolonged absence from sport. It has been estimated that foot and ankle injuries account for 27% of all injuries in elite collegiate athletes and 21% of these injuries result in missed time [5]. Furthermore, many foot and ankle injuries tend to be recurrent, and can adversely affect the overall athletic performance and quality of life (Table 7).

Table 7.

Authors assessment of risk of bias (NIH case series tool)

| S. no. | Study | Research question clearly stated? | Study population clearly specified? | Participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | All the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations? | Sample size justification provided? | Exposure (s) of interest measured prior to the outcome (s) being measured? | Timeframe sufficient? | Did the study examine different levels of the exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Altarriba-Bartes et al. [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2 | Athanasopoulos et al. [9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | van Beijsterveldt et al. [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 4 | Crema et al. [10] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 5 | Crim [16] | No | Yes | CD | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | Edouard et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | CD | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Ekeland et al. [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | CD | Yes | No |

| 8 | Elias et al. [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | CD | No |

| 9 | Engebretsen et al. [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | CD | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Fuller et al. [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Hayashi et al. [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | Heiss et al. [6] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Jarraya et al. [12] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | Junge et al. [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Junge et al. [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 16 | Keim and Williams [14] | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 17 | Kim et al. [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Mountjoy et al. [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | Nabhan et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | Nabhan et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | Ruedl et al. [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | Ruedl et al. [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | Shadgan et al. [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 24 | Soligard et al. [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Steffen [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| S. no. | Study | Were the exposure measures clearly defined, valid, reliable etc. | Was the exposure (s) assessed more than once over time? | Were the outcome measures clearly defined, valid, reliable etc. | Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted? | Overall assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Altarriba-Bartes et al. [22] | No | No | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 2 | Athanasopoulos et al. [9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Fair |

| 3 | van Beijsterveldt et al. [31] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 4 | Crema et al. [10] | Yes | CD | Yes | No | CD | CD | Poora |

| 5 | Crim [16] | Yes | No | Yes | No | CD | No | Fair |

| 6 | Edouard et al. [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 7 | Ekeland et al. [24] | Yes | CD | Yes | No | CD | No | Fair |

| 8 | Elias et al. [11] | CD | No | Yes | No | CD | No | Poora |

| 9 | Engebretsen et al. [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Good |

| 10 | Fuller et al. [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Good |

| 11 | Hayashi et al. [15] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Poora |

| 12 | Heiss et al. [6] | Yes | No | No | CD | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 13 | Jarraya et al. [12] | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Yes | CD | Poora |

| 14 | Junge et al. [26] | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Yes | CD | Fair |

| 15 | Junge et al. [13] | No | No | Yes | CD | Yes | CD | Fair |

| 16 | Keim and Williams [14] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Fair |

| 17 | Kim et al. [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Fair |

| 18 | Mountjoy et al. [27] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 19 | Nabhan et al. [29] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 20 | Nabhan et al. [29] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| 21 | Ruedl et al. [20] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 22 | Ruedl et al. [32] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Good |

| 23 | Shadgan et al. [28] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 24 | Soligard et al. [21] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 25 | Steffen et al. (2017) [33] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

CD can’t determine, NR not reported

aReasons for overall assessment as ‘Poor’ reported in the Risk of Bias section

In a systematic review, Fong et al. [4] studied injury patterns and rates of ankle injuries and ankle sprains in sports. They reported that the prevalence of ankle injuries was highest in aeroball and wall climbing. However, the incidence of ankle injuries was highest in hurling and camogie, followed by rugby. Ankle sprains were the most common injuries, followed by fractures. Rugby had the overall highest incidence of ankle sprains.

Data on foot and ankle injuries in Olympics athletes is sparse and limited to a few observational studies [6, 11, 15]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the patterns and trends of foot and ankle injuries in Olympics athletes. We noted that summer Olympics had higher injury foot and ankle rates and accounted for higher percentage of all injuries as compared to winter Olympics. We believe that this may be due to a number of reasons. Foremost is the fact that winter Olympics athletes tend to use specialized boots and sport-gear, that may result in lower injury to the foot and ankle. On the other summer Olympics athletes tend to use shoes rather than boots, which may not be as protective for the foot and ankle. Additionally, many summer Olympics sports such as Taekwondo and Rugby are contact sports, which involve direct injury to the unprotected foot and ankle, thereby accounting for higher injury rates [22, 25]. Finally, summer Olympics include a number of track and field sports, which are associated with higher rates of foot and ankle injuries.

We also noted that the rates and burden of foot and ankle injuries in Olympics showed a steady decline. Although it is hard to pin point, the reasons for this trend, we believe that this may be attributable to advances in protective gear, advancements in our understanding in injury patho-mechanics implementation of injury prevention protocols.

The most common foot and ankle injuries noted in our study were those involving tendons, ligaments and stress fractures. This is line with the findings of Fong et al. [4]. Elite athletes tend to push themselves to the limit, which may result in chronic injuries to the tendons and ligaments. Acute injuries can also ensue in background of such chronic injuries.

During the conduct of this study, we noted a few issues with the available literature on injuries in Olympics. Foremost is the lack of a universal database to ensure that all injuries sustained in Olympics athletes are recorded and reported. We noted that publications on injuries in Olympics tend to come from researchers and clinicians involved in the Olympics polyclinics set up by host countries [6, 9, 10, 12, 15, 18], or from researchers associated with national Olympics teams [19, 29]. Furthermore, the available data are often incomplete, as players from the developed nations often do not utilize the services of Olympics polyclinics, and tend to report to their individual medical teams. On the other hand, athletes from developing nations tend to utilize the services of Olympics polyclinics more often, and many of them tend to present with chronic rather than acute ailments [9, 30]. In view of these, the estimation of true injury incidence rates remains problematic. To overcome these problems, we would like to put forth the suggestion of a uniform injury reporting electronic database under the aegis of the International Olympics Committee. We feel that this step would go a long way in improving our understanding and prevention of injuries in Olympics.

There are a few limitations of this study. Owing to the nature of published data available, we did not perform meta-analysis of injury rates, nor were we able to determine sport-specific foot and ankle injury rates. In addition, we acknowledge that we may have underestimated the injury rates and burden, owing to the fact that all injuries may not have been reported in the first place. In addition, the overall quality of studies included in the study was moderate. Finally, the high statistical heterogeneity in estimation of pooled burden of foot and ankle injuries indicates that these results should be interpreted with caution.

These limitations notwithstanding, there are several strengths of this study. We strictly adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, used a well-defined search strategy that was formulated a-priori and strictly adhered to our study protocol.

Conclusion

Foot and ankle injuries account for approximately 5% of all injuries in winter Olympics and 16% of all injuries in summer Olympics. The most common foot and ankle injuries are ligament and tendon injuries. Rates of foot and ankle injuries have shown a steady decline. The declining trend notwithstanding, there is a need for a universal database for reporting of foot and ankle injuries in Olympics.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Collier R. Providing medical services at Olympics a huge task. CMAJ. 2012;184(13):E703–704. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCaffery M. Preparing for the worst: Medical services at the Calgary Olympics. CMAJ. 1988;138(2):151–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunby P. Postmortem on Winter Olympics medical care. JAMA. 1980;244(3):224–225. doi: 10.1001/jama.1980.03310030006002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong DT-P, Hong Y, Chan L-K, Yung PS-H, Chan K-M. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Medicine. 2007;37(1):73–94. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt KJ, Hurwit D, Robell K, Gatewood C, Botser IB, Matheson G. Incidence and epidemiology of foot and ankle injuries in elite collegiate athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(2):426–433. doi: 10.1177/0363546516666815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiss R, Guermazi A, Jarraya M, Engebretsen L, Hotfiel T, Parva P, et al. Prevalence of MRI-detected ankle injuries in athletes in the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Olympics. Academic Radiology. 2019;26(12):1605–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies - NHLBI, NIH [Internet]. Retrieved 13 March, 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/case_series.

- 9.Athanasopoulos S, Kapreli E, Tsakoniti A, Karatsolis K, Diamantopoulos K, Kalampakas K, et al. The 2004 Olympic Games: Physiotherapy services in the Olympic Village polyclinic. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;41(9):603–609. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.035204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crema MD, Jarraya M, Engebretsen L, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Domingues R, et al. Imaging-detected acute muscle injuries in athletes participating in the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Olympic Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(7):460–464. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elias DA, Carne A, Bethapudi S, Engebretsen L, Budgett R, O’Connor P. Imaging of plantar fascia and Achilles injuries undertaken at the London 2012 Olympics. Skeletal Radiology. 2013;42(12):1645–1655. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarraya M, Crema MD, Engebretsen L, Teytelboym OM, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, et al. Epidemiology of imaging-detected tendon abnormalities in athletes participating in the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Olympics. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(7):465–469. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junge A, Engebretsen L, Mountjoy ML, Alonso JM, Renstrom PAFH, Aubry MJ, et al. Sports injuries during the Summer Olympic Games 2008. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;37(11):2165–2172. doi: 10.1177/0363546509339357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keim ME, Williams D. Hospital use by Olympic athletes during the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;167(11–12):603–605. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi D, Jarraya M, Engebretsen L, Crema M, Roemer F, Skaf A, et al. Epidemiology of imaging-detected bone stress injuries in athletes participating in the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Olympics. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(7):470–474. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crim JR. Winter sports injuries. The 2002 Winter Olympics experience and a review of the literature. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America. 2003;11(2):311–321. doi: 10.1016/S1064-9689(03)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engebretsen L, Steffen K, Alonso JM, Aubry M, Dvorak J, Junge A, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the Winter Olympic Games 2010. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;44(11):772–780. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.076992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D-S, Lee Y-H, Bae KS, Baek GH, Lee SY, Shim H, et al. PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games and athletes’ usage of “polyclinic” medical services. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2019;5(1):e000548. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabhan D, Windt J, Taylor D, Moreau W. Close encounters of the US kind: illness and injury among US athletes at the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruedl G, Schobersberger W, Pocecco E, Blank C, Engebretsen L, Soligard T, et al. Sport injuries and illnesses during the first Winter Youth Olympic Games 2012 in Innsbruck, Austria. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;46(15):1030–1037. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soligard T, Palmer D, Steffen K, Lopes AD, Grant M-E, Kim D, et al. Sports injury and illness incidence in the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games: A prospective study of 2914 athletes from 92 countries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(17):1085–1092. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altarriba-Bartes A, Drobnic F, Til L, Malliaropoulos N, Montoro JB, Irurtia A. Epidemiology of injuries in elite taekwondo athletes: Two Olympic periods cross-sectional retrospective study. British Medical Journal Open. 2014;4(2):e004605. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edouard P, Navarro L, Branco P, Gremeaux V, Timpka T, Junge A. Injury frequency and characteristics (location, type, cause and severity) differed significantly among athletics ('track and field’) disciplines during 14 international championships (2007–2018): Implications for medical service planning. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;54:159–167. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekeland A, Dimmen S, Lystad H, Aune AK. Completion rates and injuries in alpine races during the 1994 Olympic Winter Games. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 1996;6(5):287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuller CW, Taylor A, Raftery M. 2016 Rio Olympics: An epidemiological study of the men’s and women’s Rugby-7s tournaments. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;51(17):1272–1278. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Junge A, Dvorak J, Graf-Baumann T, Peterson L. Football injuries during FIFA tournaments and the Olympic Games, 1998–2001: Development and implementation of an injury-reporting system. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004;32(1 Suppl):80S–S89. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mountjoy M, Miller J, Junge A. Analysis of water polo injuries during 8904 player matches at FINA World Championships and Olympic games to make the sport safer. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(1):25–31. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shadgan B, Feldman BJ, Jafari S. Wrestling injuries during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38(9):1870–1876. doi: 10.1177/0363546510369291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabhan D, Walden T, Street J, Linden H, Moreau B. Sports injury and illness epidemiology during the 2014 Youth Olympic Games: United States Olympic Team Surveillance. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(11):688–693. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, Alonso JM, Aubry M, Budgett R, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013;47(7):407–414. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beijsterveldt AM, Thijs KM, Backx FJ, Steffen K, Brozičević V, Stubbe JH. Sports injuries and illnesses during the European Youth Olympic Festival 2013. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;49(7):448–452. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruedl G, Schnitzer M, Kirschner W, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the 2015 Winter European Youth Olympic Festival. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(10):631–636. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steffen K, Moseid CH, Engebretsen L, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses in the Lillehammer 2016 Youth Olympic Winter Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;51(1):29–35. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]