Abstract

Common cuckoos Cuculus canorus are obligate nest parasites yet young birds reach their distant, species-specific wintering grounds without being able to rely on guidance from experienced conspecifics – in fact they never meet their parents. Naïve marine animals use an inherited navigational map during migration but in inexperienced terrestrial animal migrants unequivocal evidence of navigation is lacking. We present satellite tracking data on common cuckoos experimentally displaced 1,800 km eastward from Rybachy to Kazan. After displacement, both young and adult travelled similarly towards the route of non-displaced control birds. The tracking data demonstrate the potential for young common cuckoos to return to the species-specific migration route after displacement, a response so far reported exclusively in experienced birds. Our results indicate that an inherited map allows first-time migrating cuckoos to locate suitable wintering grounds. This is in contrast to previous studies of solitary terrestrial bird migrants but similar to that reported from the marine environment.

Subject terms: Animal migration, Behavioural ecology

Introduction

For a lone young common cuckoo Cuculus canorus, raised by foster-parents of other species, finding the proper wintering grounds thousands of kilometres away without conspecific guidance appears almost impossible. Nevertheless, as more than a billion other inexperienced migrants from the Palearctic do, it reaches its African wintering grounds every year1,2. How it manages to do this remains one of the most fascinating mysteries of migration biology3. Such challenges are faced across land and sea by a diverse range of organisms, including insects4 and cetaceans5. In the marine environment, inexperienced young of several species that travel independent of adults, including turtles6, salmon7 and eels8, are shown to rely on an inherited navigational map based on geomagnetic information9. This has the obvious advantage of being able to correct for unwanted displacement. Nevertheless, evidence for true navigation in first-time avian migrants remains equivocal3.

Routes and non-breeding staging sites of many long-distance migrating land birds are population-specific and conserved across individuals10,11 (but see12), with routes involving challenging barrier crossings such as the Mediterranean and the Sahara for Afro-Palearctic migrants. In general, young migrants possess an innate migratory orientation programme enabling them to overcome these challenges; a programme which over generations has provided the highest chances of returning to breed next spring and thus the highest fitness13. Many aspects of the adaptive programme have been revealed, such as innate timing and direction14,15. However, the evidence about whether it involves some form of navigation remains contradictory3.

Studying responses to displacement allows us to distinguish between different types of underlying navigation strategies16. Displacement experiments, such as the paradigmatic experiment by Perdeck17 involving more than 11,000 European starlings Sturnus vulgaris and later repeated with Zonothricia sparrows18,19, have documented an endogenous directional programme steering inexperienced migrants in a certain direction. Cage studies have shown that the direction is followed over an innately controlled period of time, providing first-time migrants with direction and distance15. With experience, this programme develops into a goal-area navigation programme normally allowing the birds to pinpoint at least their breeding and winter grounds even from unfamiliar areas15.

Such an ability has been well documented in adult birds as shown by lesser black-backed gulls Larus fuscus20 and adult common cuckoos21 returning to the normal migration route after long-distance displacements of 1,080 and 2,500 km, respectively, though with marked inter-individual flexibility in route and timing. Similar navigation responses have been shown for directional preferences of displaced adults22 but not always23. However, while the displacements of starlings and Zonothricia sparrows did not indicate such an ability in juveniles, contradicting evidence has been reported in other studies, and whether some ability to correct for orientation errors or wind displacement is also present in juvenile birds remains unclear3. A re-analysis of 109 published displacement experiments indicated that even juvenile birds were able to detect and react to displacements, including those in which displacement was simulated in a planetarium24. Additionally, experiments by Åkesson et al.25 indicate that juvenile white-crowned sparrows Zonothricia leucophrys may be able to correct for displacements and both wind-displaced and experimentally displaced birds on the Faroe Islands showed compensatory responses26.

Given the contradicting evidence about the ability to compensate displacement, we challenged this experimentally by building on recent advances in tracking technologies that allow globally unbiased spatiotemporal mapping of movements of smaller, long-distance migrants. Thus, we tracked the responses to an experimental 1,800 km eastward displacement of adult and young common cuckoos. Common cuckoos migrate from their breeding grounds in the Palearctic to their wintering grounds in sub-Saharan Africa. The long distances are travelled at night, presumably solitarily without guidance from conspecifics1,2. As the cuckoo is a nest parasite, juveniles rely on their inherent migration programme to locate suitable winter grounds1,2,27. We investigated the nature of the innate migration programme by comparing the tracks of displaced birds with those from non-displaced migrants caught en route on the Courish Spit at the Baltic Coast (Fig. 1a). We tested for evidence of navigation in young birds, potentially shown by displaced first-time migrants differing from non-displaced controls and responding similarly to adults compensating the displacement.

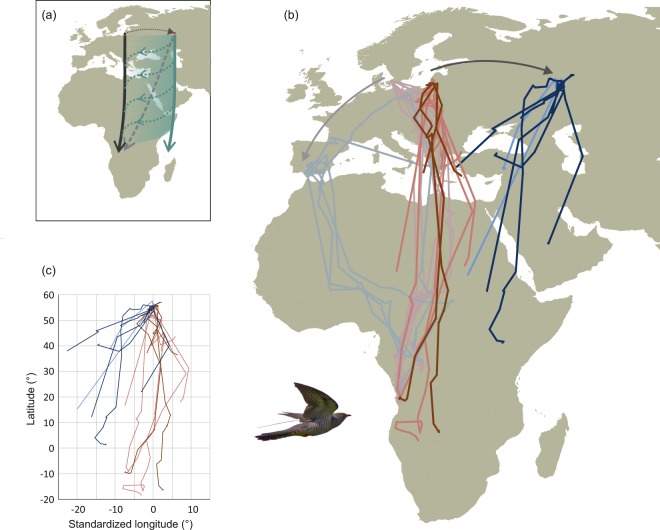

Figure 1.

Tracks of control common cuckoos migrating through Rybachy, Kaliningrad, Russia, during autumn (red) and experimental birds displaced to Kazan, Russia (blue). (a) Standard uncompensated migration from Rybachy to the winter grounds (black), theoretical compensated route with navigation from the release site in Kazan to the normal winter grounds (grey dotted) and expected displacement responses (green) showing an uncompensated route (solid line) and adult-type response (dotted and transparent). (b) Tracks of adult (pale) and first time (dark) migrating cuckoos released in Rybachy (controls, red) and displaced (blue) to Kazan. Tracks of adults released in Denmark (pink) and displaced to Spain (grey) (Adapted from Willemoes et al.21 with permission) are shown for comparison. (c) Comparison of control and displaced tracks with standardised starting longitude. Maps are created using R software (version 3.4.4; https://cran.r-project.org/) using the packages “maps” version 3.3.0 and “rgdal” version 1.3-6.

Results

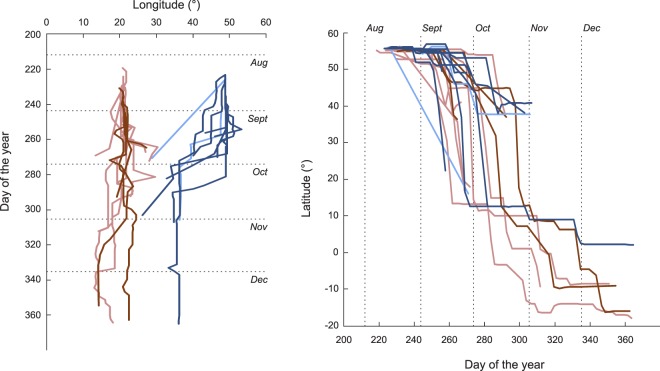

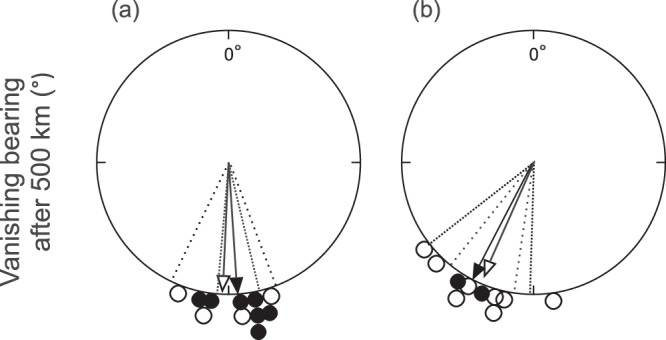

The routes of first-time migrating cuckoos displaced eastwards from Rybachy to Kazan (Fig. 1b) led them overall closer to the normal migration routes, with the endpoints of the displaced first-time migrants being significantly displaced westward compared to the controls (−10.7 ± 7.1° and 0.0 ± 5.9° [mean ± s.d.] for displaced (n = 8) and control (n = 4) young, respectively; t-test of difference: p = 0.027; Fig. 1c. Bearings to endpoints of control young: 178.5°, r = 0.992, Rayleigh test: p = 0.008; displaced young: 202.7°, r = 0.976, Rayleigh test: p < 0.001; Watson-Williams test of difference, F1,10 = 10.708, p = 0.008). The displaced young cuckoos travelled south-southwest from Kazan in a slightly more westward direction than the control first-time migrants but their ability to correct only became apparent after they had travelled over a long distance, indicated by the initial bearings (after crossing 500 km), which were not significantly different (Fig. 2a,b). No differences in the timing of control and displaced birds were apparent (Fig. 3. Difference in timing of crossing 500 km distance: p = 0.128, 1000 km distance: p = 0.865; t-tests). Movements of young birds were on average slightly earlier – 10 days when crossing 500 km distance – but not significantly so and not after crossing 1,000 km (Difference in timing of crossing 500 km distance: p = 0.063, 1,000 km distance: p = 0.834; t-tests. Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Directional response to displacement in first-time and adult cuckoos. Bearing after crossing 500 km in first-time (white) and adult (black) cuckoos from (a) Rybachy, Russia, (182.5 ± 14.9° and 175.7 ± 9.7° [mean ± s.d.] for juveniles (n = 4) and adults (n = 7), respectively) and (b) after the 1,800 km displacement eastward to Kazan, Russia, (203.5 ± 17.7° and 207.0 ± 5.7° for juveniles (n = 8) and adults (n = 2), respectively). Arrows indicate mean direction and vector length, dotted lines 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Timing of flights in displaced (blue) and control (red) adult (light) and young (dark) cuckoos. Displaced and control young were tracked for equally long (day of the year of last position: 289.3 ± 35.9 and 319.0 ± 47.7 [mean ± SD] for displaced (n = 8) and control young (n = 4), respectively; t10 = 1.22, p = 0.25; Day of the year of last position adults: 288.5 ± 24.7 and 307.3 ± 37.3 for displaced and control adults, respectively). The tracks were terminated for four out of the eight displaced juvenile cuckoos already in September and for the displaced adults in the end of September and early October.

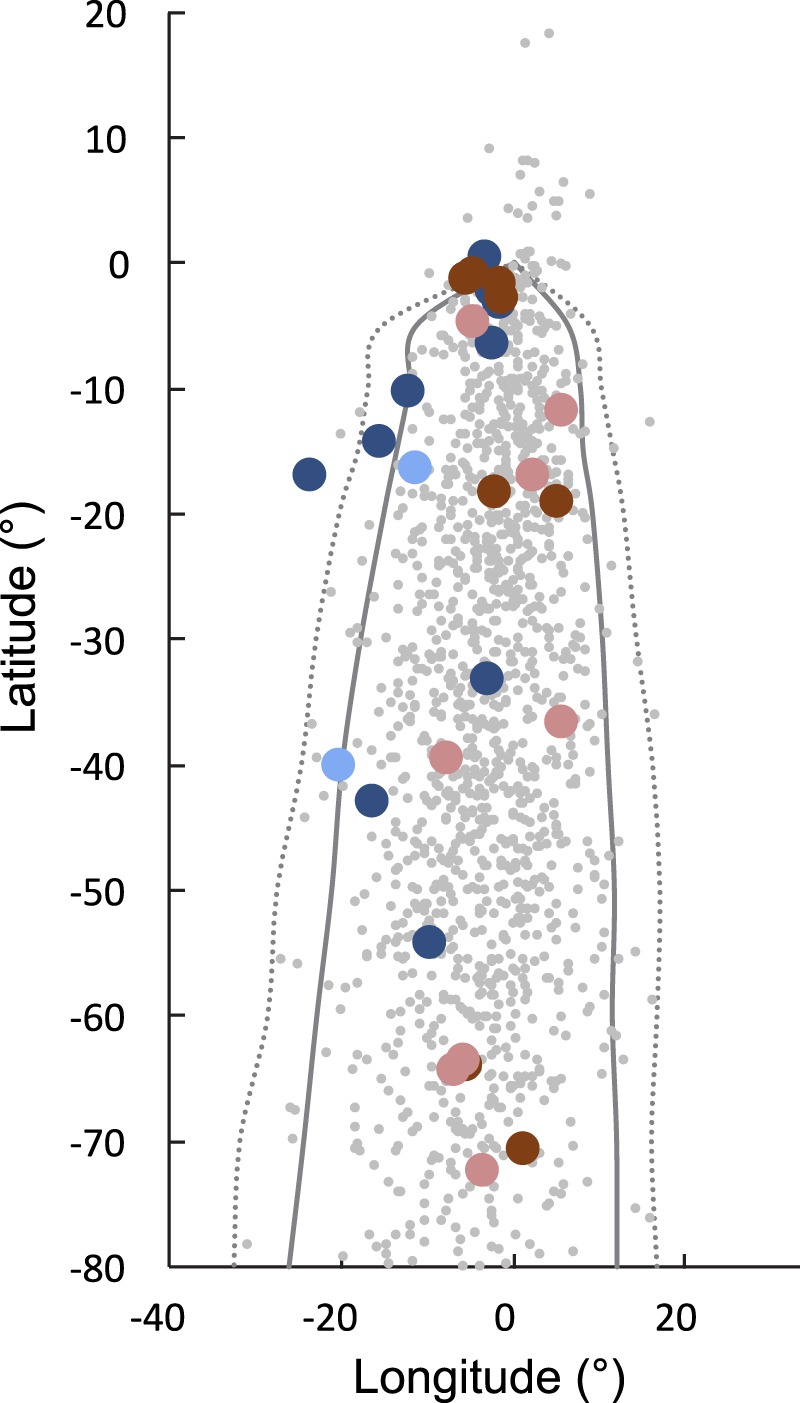

Though we find significant compensation in the displaced young on average, the individual responses varied and the resulting tracks showed a large scatter in directions and a large longitudinal spread along the migration route. Two birds demonstrated significant compensation (Outliers in simulation tests, p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively; Fig. 4) both being more westerly than those of control birds with one individual reaching the longitudes of control birds and thus evidently compensating fully for the displacement. The tracks of displaced adults overlapped those of the displaced young with similar distances and degree of compensation (Fig. 1b,c) as did the directions to positions after crossing 500 km (Fig. 2b), and so the compensatory reactions among displaced young were similar to the compensation in displaced adults. Among the first-time migrants that compensated only partly (Figs. 1b,c and 2b), a bird wintering 2,500 km northeast of the nearest control bird demonstrates the potential for surviving in new wintering grounds without fully compensating for the displacement. This bird in fact moved toward south-southwest in January and February after having reached sub-Saharan Africa in October.

Figure 4.

Comparison of simulated (grey) and observed endpoints of displaced (blue) and control (red) adult (light) and young (dark) cuckoos displaced to starting in (0°, 0°). Confidence intervals of simulated endpoints (dots; n = 1,500) are indicated (solid line: p < 0.05; stippled line: p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our results provide new insights into the migratory programme that brings naïve parasitic cuckoos to their wintering grounds for the first time. Our tracks of displaced young demonstrate that it is possible for first time migrants to compensate for such a displacement and thus the existence of inherited navigational responses similar to those demonstrated in marine animals6–8. At the same time, other individuals followed routes with little or no compensation, although this may have changed if the birds were tracked all the way to the wintering grounds. The responses observed are similar to those observed in adults, which are also able to compensate for displacements but many nevertheless follow uncompensated routes long after the displacement. Overall, the tracks provide evidence of an adult-type response to long-distance displacement in juvenile common cuckoos.

Despite the evidence from animals navigating in the marine environment6–8, the capability of compensation after displacement in migratory naïve birds has not been unequivocally demonstrated before. Such an “open and flexible” system – similar to that found in adults – likely provides evolutionary advantages as birds have the “option” to stay if they find suitable routes and wintering areas but also the possibility of returning to the normal route. Compensatory responses might be needed less often for migrants in the terrestrial than in the marine environment as terrestrial migrants spend most of the time resting on the ground whereas marine animals are constantly in a flowing media28. Thus, compensation is typically only necessary for terrestrial migrants during travel when they are more exposed to for example winds. In fact, compensating partly would not need to be based on an inherited map: juveniles could combine orientation in the normal migration direction with experienced-based navigation toward a site already visited on migration, as birds already on the way on their first migration could be acquiring information necessary for later navigation26.

While individual birds’ responses to displacements are key for distinguishing navigation strategies16, most studies only track these in the lab23,29 or for a shorter distance (up to a few hundred kilometres)26,30,31. For long-distance migrants, satellite tracking allows spatially unbiased study of the behavioural responses to displacement but few experiments have been performed in first-time migrants, and all of these have focussed on social migrants where group orientation might be guided by experienced individuals. Displacement experiments with young white storks Ciconia ciconia32 and relocations of lesser spotted eagles Clanga pomarina for re-introduction33 indicated a less precise migration programme with birds being dependent on social interactions to complete normal migrations as also indicated by a study on hybrids between lesser and greater spotted eagles Clanga clanga34. The initial uncompensated movements could indicate navigation based on inherited “signposts”35,36 and they align well with observations from the marine environment, where navigation in inexperienced animals appears to be based on navigational markers (a simple look-up table37). Thus, the information might only be available when the animal is within a certain range, requiring long-distance tracking to observe.

An alternative explanation for the observed changes in routes by first-time migrating cuckoos would be that they travelled with experienced individuals. However, we believe this is unlikely to be the case because young cuckoos are mainly solitary migrants managing to reach their wintering grounds without guidance as shown by differences in timing between young and adults from other populations with other routes2. Nevertheless, the routes for populations naturally occurring at the site of displacement may well be similar to the displaced birds but flocking and social interactions such as calling are not regularly observed during migration. The overall navigation strategies employed by displaced birds appear similar between experienced and first-time migrants. The fact that many tracks ended without full compensation might be caused by transmission ending before having reached the wintering grounds. The less than full compensation in those ending far to the south could also be caused by a compensatory response rooted in a plane rather than a sphere. On a sphere, a certain difference in longitudes corresponds to a longer distance closer to the Equator and the distance between the capture and displacement sites is shorter than the distance between the normal wintering grounds and those that would be reached after uncompensated migration in displaced individuals. Thus, if the birds compensated the displacement distance (rather than a difference in longitudes) after having moved south they would not reach the longitudes of the control birds.

The actual mechanisms used for the navigational tasks remain unclear. Geomagnetic cues are widely available across taxa for orientation even in insects38. Given the omnipresence of geomagnetic cues and the demonstration of their use for true navigation in adult bird migrants39,40 as well as in inexperienced marine animals6–9 these appear to be the most likely candidates. Furthermore, experiments have indicated that geomagnetic cues, characteristic of certain latitudes or regions, affect the orientation35 or the deposition of fuel36 of first-time migrants. However, their use over inter-continental scales are not straightforward as neither field intensity, inclination nor declination show simple gradient patterns over the scales considered. Alternatively, navigation could be based on olfactory cues as in experienced migrating gulls20 and catbirds Dumetella carolinensis31.

Our results challenge the common understanding of the orientation programme in inexperienced migratory birds. The strategy appears to include some form of navigation, at least in common cuckoos. A navigational programme as demonstrated here might be crucial during even more extreme land bird migrations as for example the 13,000 km long migration spanning across many degrees of latitudes and longitudes of willow warblers Phylloscopus trochilus migrating from Chukotka to Southeast Africa41, but navigational responses at the scale considered has not been studied so far. Our study lays out the foundation for studying capabilities and underlying cue use necessary for a deeper understanding of bird migration. Broadening out our study with respect to populations and species awaits even further technical advancements such as those promised by ICARUS42.

Methods

Ethical statement

The Ethical Committee of the Zoological Institute (RAS #2015-01-14) and Kaliningrad Regional Agency for Protection, Reproduction and Use of Animal World and Forests approved sampling procedures and experimental manipulations, and permitted the catching and tagging of cuckoos. This study was carried out in accordance with Guidelines to the use of wild birds in research of the Ornithological Council43.The common cuckoo is not a protected species and it is not considered threatened or endangered.

Experimental animals, tagging and displacement

Adult and juvenile cuckoos used for the study were caught in the Kaliningrad Region shortly after initiation of autumn migration during late July – August 2015-2018. Individual migration routes were tracked using satellite telemetry and individuals were either controls (tagged and released close to trapping site) or displaced (tagged and displaced in groups 1,800 km eastward to Kazan, Tatarstan).

Cuckoos were trapped at two sites: the Biological Station Rybachy (55° 9’ 13” N, 20° 51’ 29” E) and the Fringilla Field Station (55° 5’ 18” N, 20° 44’ 3” E). Two large Heligoland traps at the Fringilla station as well as mist-nests at the two stations were used for trapping. Playback of cuckoo song and calls was widely used to attract birds.

To treat both control and experimental birds equally, all birds were kept in aviaries after trapping for 1 to 22 days. They were provisioned with mealworms and water ad libitum until tagging and release. During this time, the birds’ behaviour and weight changes were monitored. Birds with high body mass (minimum >100 g) and good condition were tagged and released, or kept for planned displacement events if they had not been kept in captivity for too long (> 1 week). Control birds were released during the period both before and after displacements.

We fitted satellite transmitters on 27 juvenile and 18 adult common cuckoos (see Supplementary Table S1-2 for deployment details). Tags were fitted with a backpack harness of 2 mm ø braided nylon cord. The juvenile harness size was the same as the one used in adults to account for further body growth44. Cuckoos were tagged just before release (control birds), or one or two days before (displaced birds).

The displaced group consisted of 15 juveniles and 7 adults translocated to Kazan in 2015, 2016 and 2018. They were transported by commercial airline in pet carriers and released into a natural, wooded habitat in daylight conditions as soon as possible after arrival (release site 55° 51’ 18” N, 48° 48’ 18” E and 55° 39’ 22” N, 49° 2’ 13” E, respectively). The control group consisted of 12 juveniles and 11 adults. Apart from the early movement of two juveniles displaced to Kazan that moved more than 100 km within four days, we found no general difference between control and displaced birds in departure timing after release (Difference in days after first position when crossing 500 km distance: p = 0.154, 1,000 km distance: p = 0.920; t-tests).

Tracking

The tags used for this study transmitted location information via satellites. Two models of transmitting tags were used to obtain spatial data in this study: Platform Terminal Transmitters (PTTs) 5 g solar PTT-100s (Microwave Telemetry Inc., Maryland, USA) and 3.4 g or 3.7 g PinPoint GPS ARGOS Tags 75 (LOTEK, Newmarket, Canada; tag mass depended on antenna specifications).

Location estimates were obtained from PTTs by interpreting the Doppler effect of transmissions from the tags to the Argos Satellite system. Position quality and accuracy is determined (where possible) by the number and duration of transmissions (estimated error classes 0: >1,500 m; 1: 500–1,500 m; 2: 250–500 m; 3: <250 m (45). The tags had a solar cell and the temporal schedule was 10 hours transmission followed by 48 hours off, for as long there was sufficient power.

The PinPoint tags provide GPS positions acquired at scheduled intervals, compressed and transmitted via the Argos system. The tags are scheduled in advance and limited by internal battery capacity (determined by the GPS acquisition time and transmission of data to the Argos system). In 2015, tags were programmed to obtain positions regularly on a short schedule and transmit data on a predefined date (estimable to a date prior to the Sahara crossing), or for a long schedule where positions were attempted until transmission which was determined by a critical battery voltage. In 2017, tags were equipped with Argos satellite pass prediction software by which the tag only transmitted data when a satellite was within range, thus substantially improving power efficiency and enabling regular transmission of data throughout the migration period. All transmission data include time stamps and satellite ID.

From the PinPoint tags, GPS position data were transmitted via the ARGOS satellite system and processed with LOTEK software; failed positions were excluded. Doppler positions can also be obtained from transmitting PinPoint tags but only a few of these were received.

In cases where an Argos transmission occurred but no Doppler position could be estimated, an estimate and error radii was calculated from satellite pass data by CLS. Where a PinPoint tag had acquired a concurrent GPS position this was used in preference to the ARGOS estimate.

After rejecting class Z estimates, we used the highest quality position from each transmission cycle closest to noon.

Data analyses

Of the 27 tagged juveniles, we considered the 12 individuals that were tracked for more than 500 km/crossed south of 50°N to have started migration (Table 1). Initial movements appeared to be slightly further westward in the first year but the bearings after crossing 100 km were not significantly different from the other years, and thus in the analyses we considered results from all years together. In adults, 9 of 18 started migration.

Table 1.

Summary of common cuckoo data. Numbers indicate individuals included in analyses, i.e. tracked for more than 500 km/crossing south of 50°N.

| Year | Juveniles | Adults | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rybachy | Kazan | Rybachy | Kazan | ||

| 2015 | 1 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 8 (21) |

| 2016 | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) | ||

| 2017 | 2 (5) | 4 (5) | 6 (10) | ||

| 2018 | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 5 (7) | ||

| All years | 4 (12) | 8 (15) | 7 (11) | 2 (7) | 21 (45) |

Numbers in brackets indicate numbers of individuals tagged.

We used the highest quality position for every duty cycle obtained from ARGOS/CLS44. Several birds moved back and forth for some time after release with no consistent direction of movement, and we considered that they started migration when consistent directions were observed.

We investigated the spatiotemporal pattern of responses by grouping individuals’ locations according to when they had passed certain distances. However, the sampling schedule did not allow detailed analyses of timing of responses. We compared bearings and timings after crossing 500 km (n = 13) and 1,000 km (n = 19) from the release areas because for shorter intervals there were not enough locations for meaningful comparisons (only up to a maximum of 7 in 100 km intervals). The directedness of sample orientations for the individuals of a group was tested with the Rayleigh test. Differences in sample orientations were tested with Watson-Williams tests. We used t-tests on day of the year of crossing 500 km and 1,000 km as well as reaching endpoints to compare the timing of migration between controls and displaced and between adult and juveniles.

Because of the distance to the wintering grounds, even large distances at the latitude of the wintering grounds result in potentially relatively small differences in bearings. Thus, in addition to comparing bearings to endpoints (last position, see Supplementary Table S2 for details) using a Watson-Williams test, we tested for evidence of navigation in young birds by comparing the westward longitudinal displacement of endpoints in displaced versus controls. We treated longitude data as linear and compared groups with a t-test. This was justified as less than 10% of the full circle of longitudes were traversed and the Watson-Williams test based on longitudes reported the same result (F1,10 = 6.701, p = 0.027 for a difference between controls and displaced). In an ANOVA including both age and displacement effects together, displacement was significant but age was not (p = 0.07) potentially because of small sample size.

To test for displaced individuals compensating for the displacements, we compared with tracks simulated under the assumption that control birds follow a clock-and-compass strategy (vector orientation). Outliers (i.e. significantly deviating longitudinally), were considered compensating if the deviation was in the direction of compensation (Fig. 4). In the young cuckoos, we identified 37 movements longer than 100 km that were used for simulations. Considering the longitudes and latitudes traversed in each of these as the result of a clock-and-compass step, we simulated tracks by adding from 1 to 15 randomly chosen longitudes/latidues from this set. For each total number of steps (1 to 15), we simulated 1,000 tracks, resulting in a total of 15,000 simulated endpoints for the test data.

We used R 3.3.246 for linear statistics and Oriana 3.047 for circular statistics and diagrams. MS Excel was used for simulations.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Danish Council for Independent Research supporting the MATCH project (1323–00048B), the Danish National Research Foundation supporting the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate (DNRF96), the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant 16-04-00761 to LS) and the participation of the Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences (project AAAA-A19-119021190073-8). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 751692. We thank Emily Baird and Miriam Liedvogel for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

K.T. and V.B. conceived and designed the study. K.T., M.L.V., K.R.S.S., R.L. M.W., S.S., L.V.S., and V.B. carried out field work and gathered the tracking data. K.T. and S.S. analysed the data with assistance from M.L.V., K.R.S.S. and M.W. K.T. drafted the manuscript with assistance from M.L.V. and K.R.S.S. K.T., M.L.V., K.R.S.S., R.L. M.W., S.S., L.V.S. and V.B. commented on and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All tracking data are available in www.movebank.org (10.5441/001/1.vk36vq82)

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-64230-x.

References

- 1.Sutherland WJ. The heritability of migration. Nature. 1988;334:471–472. doi: 10.1038/334471a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vega ML, et al. First-Time Migration in Juvenile Common Cuckoos Documented by Satellite Tracking. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0168940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alerstam T. Conflicting Evidence About Long-Distance Animal Navigation. Science. 2006;11:791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1129048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman JW, Reynolds DR, Wilson K. Long-range seasonal migration in insects: mechanisms, evolutionary drivers and ecological consequences. Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:287–302. doi: 10.1111/ele.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mate BR, et al. Critically endangered western gray whales migrate to the eastern North Pacific. Biol. Lett. 2015;11:20150071. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putman NF, Endres CS, Lohmann CMF, Lohmann KJ. Longitude perception and bicoordinate magnetic maps in sea turtles. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:463–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putman NF, et al. An inherited magnetic map guides ocean navigation in juvenile Pacific salmon. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naisbett-Jones LC, Putman NF, Stephenson JF, Ladak S, Young KA. A magnetic map leads juvenile European eels to the Gulf Stream. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:1236–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putman NF. Inherited magnetic maps in salmon and the role of geomagnetic change. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2015;55:396–405. doi: 10.1093/icb/icv020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton I. Obligate and facultative migration in birds: Ecological aspects. J. Ornith. 2012;153:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s10336-011-0765-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorup K, et al. Resource tracking within and across continents in long-distance bird migrants. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1601360. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finch T, Butler SJ, Franco AMA, Cresswell W. Low migratory connectivity is common in long‐distance migrant birds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2017;86:662–673. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lack D. Bird Migration and Natural Selection. Oikos. 1968;19:1–9. doi: 10.2307/3564725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berthold P, Querner U. Genetic Basis of Migratory Behavior in European Warblers. Science. 1981;212:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.212.4490.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berthold, P. Control of bird migration (Chapman and Hall, London, 1996).

- 16.Åkesson, S. Avian long-distance navigation: Experiments with migratory birds. In (ed. Berthold P, Gwinner E, Sonnenschein E) Avian Migration, 471-492 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2003).

- 17.Perdeck, A.C. Two Types of Orientation in Migrating Starlings, Sturnus vulgaris L., and Chaffinches, Fringilla coelebs L., as Revealed by Displacement Experiments. Ardea55, 1-37 (1958).

- 18.Mewaldt LR. California sparrows return from displacement to Maryland. Science. 1964;146:941–942. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3646.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorup K, et al. Evidence for a navigational map stretching across the continental U.S. in a migratory songbird. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:18115–18119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704734104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wikelski M, et al. True navigation in migrating gulls requires intact olfactory nerves. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17061. doi: 10.1038/srep17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willemoes M, Blas J, Wikelski M, Thorup K. Flexible navigation response in common cuckoos Cuculus canorus displaced experimentally during migration. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16402. doi: 10.1038/srep16402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chernetsov N, Kishkinev D, Mouritsen H. A Long-Distance Avian Migrant Compensates for Longitudinal Displacement during Spring Migration. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:188–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishkinev D, et al. Experienced migratory songbirds do not display goal-ward orientation after release following a cross-continental displacement: an automated telemetry study. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37326. doi: 10.1038/srep37326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorup K, Rabøl J. Compensatory behaviour following displacement in migratory birds. A meta-analysis of cage-experiments. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007;61:825–841. doi: 10.1007/s00265-006-0306-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Åkesson S, Morin J, Muheim R, Ottosson U. Dramatic orientation shift of white-crowned sparrows displaced across longitudes in the high Arctic. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1591–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorup K, et al. Juvenile Songbirds Compensate for Displacement to Oceanic Islands during Autumn Migration. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seel DC. Migration of the northwestern European population of the cuckoo (Cuculus canorus), as shown by ringing. Ibis. 1977;119:309–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1977.tb08250.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putman N. Marine migrations. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:R972–R976. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishkinev D, Anashina A, Ishchenko I, Holland R. Anosmic migrating songbirds demonstrate a compensatory response following long-distance translocation: a radio-tracking study. J. Ornithol. 2020;161:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10336-019-01698-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wikelski M, et al. Going wild: what a global small-animal tracking system could do for experimental biologists. J. Exp. Biol. 2007;210:181–186. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holland RA, et al. Testing the role of sensory systems in the migratory heading of a songbird. J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212:4065–4071. doi: 10.1242/jeb.034504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chernetsov N, Berthold P, Querner U. Migratory orientation of first-year white storks (Ciconia ciconia): inherited information and social interactions. J. Exp. Biol. 2004;207:937–943. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyburg BU, et al. Orientation of native versus translocated juvenile lesser spotted eagles (Clanga pomarina) on the first autumn migration. J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220:2765–2776. doi: 10.1242/jeb.148932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Väli Ü, Mirski P, Sellis U, Dagys M, Maciorowski G. Genetic determination of migration strategies in large soaring birds: evidence from hybrid eagles. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2018;285:20180855. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck, W. & Wiltschko, W. Magnetic factors control the migratory direction of Pied Flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca Pallas). In: Ouellet H, editor. Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici (University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, Canada) 1955–1962 (1988).

- 36.Fransson T, et al. Magnetic cues trigger extensive refuelling. Nature. 2001;414:35–36. doi: 10.1038/35102115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould JL. Animal Navigation: A Map for All Seasons. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:R153–R155. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dreyer D, et al. The Earth’s magnetic field and visual landmarks steer migratory flight behaviour in the nocturnal Australian bogong moth. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:2160–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deutschlander ME, Phillips JB, Munro U. Age-dependent orientation to magnetically-simulated geographic displacements in migratory Australian silvereyes (Zosterops l. lateralis) Wilson J. Ornithol. 2012;124:467–477. doi: 10.1676/11-043.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kishkinev D, Chernetsov N, Pakhomov A, Heyers D, Mouritsen H. Eurasian reed warblers compensate for virtual magnetic displacement. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:R822–R824. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokolovskis K, et al. Ten grams and 13,000 km on the wing – route choice in willow warblers Phylloscopus trochilus yakutensis migrating from Far East Russia to East Africa. Move. Ecol. 2018;6:20. doi: 10.1186/s40462-018-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curry A. The internet of things. Science. 2018;562:322–326. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fair, J., Paul, E. & Jones, J. (eds) Guidelines to the use of wild birds in research. Ornithological Council (Washington, DC, 2010).

- 44.Willemoes M, et al. Narrow-Front Loop Migration in a Population of the Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus, as Revealed by Satellite Telemetry. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e83515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyd JD, Brightsmith DJ. Error Properties of Argos Satellite Telemetry Locations Using Least Squares and Kalman Filtering. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) http://www.R-project.org (2018).

- 47.Kovach, W. Oriana – Circular Statistics for Windows, ver. 3. (Kovach Computing Services). http://www.kovcomp.co.uk. (2009).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All tracking data are available in www.movebank.org (10.5441/001/1.vk36vq82)