Abstract

Upregulation of Nell-1 has been associated with craniosynostosis (CS) in humans, and validated in a mouse transgenic Nell-1 overexpression model. Global Nell-1 inactivation in mice by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis results in neonatal lethality with skeletal abnormalities including cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD)-like calvarial bone defects. This study further defines the role of Nell-1 in craniofacial skeletogenesis by investigating specific inactivation of Nell-1 in Wnt1 expressing cell lineages due to the importance of cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) in craniofacial tissue development. Nell-1flox/flox; Wnt1-Cre (Nell-1Wnt1 KO) mice were generated for comprehensive analysis, while the relevant reporter mice were created for CNCC lineage tracing. Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice were born alive, but revealed significant frontonasal and mandibular bone defects with complete penetrance. Immunostaining demonstrated that the affected craniofacial bones exhibited decreased osteogenic and Wnt/β-catenin markers (Osteocalcin and active-β-catenin). Nell-1-deficient CNCCs demonstrated a significant reduction in cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. Active-β-catenin levels were significantly low in Nell-1-deficient CNCCs, but were rescued along with osteogenic capacity to a level close to that of wild-type (WT) cells via exogenous Nell-1 protein. Surprisingly, 5.4% of young adult Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice developed hydrocephalus with premature ossification of the intrasphenoidal synchondrosis and widened frontal, sagittal, and coronal sutures. Furthermore, the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus and ependymal cells exhibited degenerative changes with misplaced expression of their respective markers, transthyretin and vimentin, as well as dysregulated Pit-2 expression in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice. Nell-1Wnt1 KO embryos at E9.5, 14.5, 17.5, and newborn mice did not exhibit hydrocephalic phenotypes grossly and/or histologically. Collectively, Nell-1 is a pivotal modulator of CNCCs that is essential for normal development and growth of the cranial vault and base, and mandibles partially via activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Nell-1 may also be critically involved in regulating cerebrospinal fluid homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of postnatal hydrocephalus.

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Proteomics

Introduction

The Nell-1 gene was originally cloned from a chick embryonic cDNA library as a binding complex to a nuclear protein and was found to be highly conserved among mice and humans [1, 2]. Clinically, human NELL-1 has been linked to non-syndromic unilateral coronal craniosynostosis (CS) due to its overexpression at premature fusing and fused coronal sutures [3]. Global gain and loss of Nell-1 mouse models have demonstrated Nell-1′s major function in the development of skeletal tissues, particularly for the craniofacial skeleton [4, 5] and for the growth and maintenance of the appendicular bones [6, 7]. Currently, the data suggested that Nell-1 promotes osteogenesis primarily by augmenting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway through interactions with its binding partner, β1, and/or its newly identified receptor, contactin-associated protein-like 4 (Cntnap4), in osteoblasts [6, 8]. The manifestations of CS in Nell-1 overexpression transgenic (CMV-Nell-1) neonatal mice and cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) like calvarial defects in N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced Nell-1 deficient (END) neonatal mice have clearly revealed the prominent role of Nell-1 in craniofacial skeletal development [4, 9]. Unfortunately, the drawbacks of super-physiological overexpression of Nell-1 driven by CMV and the neonatal lethality of END mouse models have precluded the study of Nell-1′s effects in more defined conditions and at postnatal stages [4, 5]. Advances in mouse genetic manipulation for highly-specific cell/tissue inactivation of target genes and reliable in vivo reporter systems enabled further delineation of Nell-1′s role in craniofacial conditions [10, 11]. Due to the great importance of cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs) in craniofacial tissue development [12, 13], this study further defines the functionalities of Nell-1 in the craniofacial skeleton originating from CNCCs.

Notably, a variety of craniofacial tissues including the nerves, ganglia, connective tissues, cartilage, and bones are CNCC derivatives [14, 15]. It has been reported that CNCC precursors arise at the lateral margin of the neural fold at the boundary between the surface and neural ectoderm, and migrate ventrolaterally as the cranial ganglia and skeletogenic neural crest cells and populate the branchial arches [14, 16]. Multiple experimental approaches have validated that CNCCs are derived and emigrated from Wnt1-expressing precursor cells in the dorsal central nervous system (CNS) during the early stage of embryogenesis (E8.5–11.5) [16–19]. Consequently, upon confirmation of Wnt1 as a faithful cell lineage marker of CNCCs, it becomes possible to investigate the dynamic involvement of CNCCs in the development and growth of the craniofacial tissues [18, 20]. In particular, studies on the tissue origins of the mouse skull vault and mandibular skeleton using Wnt1-Cre and ROSA26R reporter mouse lines have provided evidence that CNCCs contribute significantly to the development of the craniofacial tissues [14, 21]. It is worth noting that Wnt1-Cre has been widely used for specific gene knockouts in CNCC lineages and has produced tremendous amounts of valuable data in neuroscience and other relevant fields [16, 22], although other CNCC lineage mouse lines are also available [23, 24].

To further define the role and molecular mechanisms of Nell-1 in CNCCs during craniofacial skeletal development and postnatal growth, we have conditionally inactivated the Nell-1 gene using the Cre/loxP recombination system [11]. Here we show that specific inactivation of the Nell-1 gene in Wnt1 expressing cell lineages results in frontonasal and mandibular bone (MB) hypoplasia and postnatal hydrocephalus with premature ossification of the synchondroses.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animals were cared for according to the institutional guidelines set at the University of California, Los Angeles. Nell-1flox/flox mice were generated by flanking Exon 1 containing ATG site with loxP (Strain: B6.129Sv/Pas-Nell1tm from EMMA-European Mouse Mutant Archive) and then excising the FRT-flanked Neo cassette with FLPo-10 delete mice (Stock# 011065 from Jackson Laboratory) in C57BL/6J background (Fig. 1a). Nell-1flox/flox mice were mated with either CMV-Cre (Stock# 006054) or Wnt1-Cre (Stock# 022501) mice to obtain Nell-1flox/flox;CMV-Cre (Nell-1CMVKO) or Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as well as Cre negative littermates (WT), respectively. Moreover, R26R (Stock# 003474) and R26R-tdTomato (Stock# 007909) mice were used to yield Nell-1flox/flox; Wnt1-Cre; R26R (Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO) or Nell-1flox/flox; Wnt1-Cre; R26R-tdTomato (Nell-1Wnt1-tdTomato KO) mice for cell lineage validation purpose. Mating was carried out overnight and females were examined for the presence of vaginal plugs and defined as 0.5 dpc (days post coitum). Animal groups were of mixed gender unless otherwise stated. The mutant and R26R mouse genotypes were identified by PCR using primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Wnt1 expressing cell lineage validation was done either by X-gal staining (see details in Supplementaryl Material and Methods) or by fluorescent microscopy. Newborn mice (P0) were sacrificed for CNCCs culture, histology, and micro-CT analysis. In addition, mice (P21–48) with hydrocephalus were collected for histology and micro-CT analysis along with age- and gender-matched control littermates.

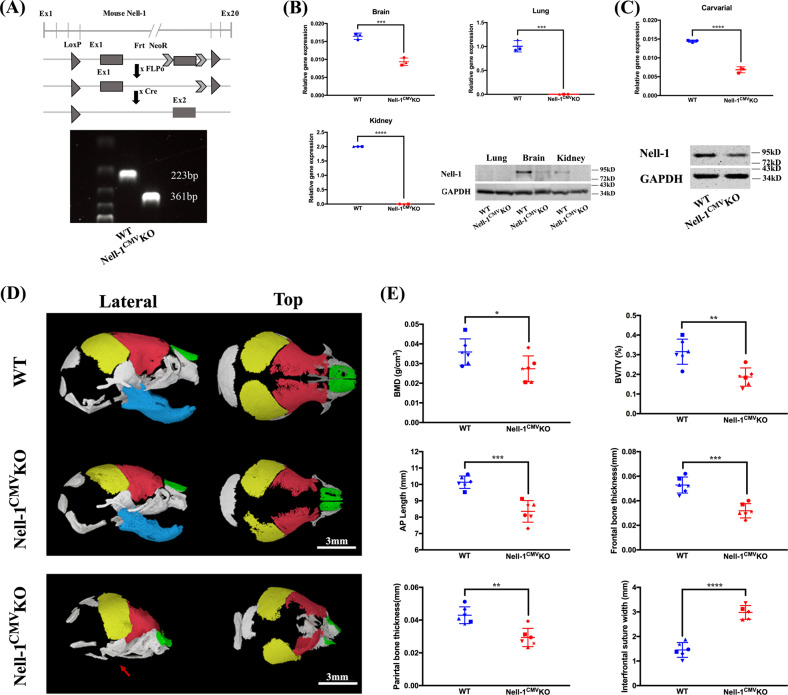

Fig. 1.

Generation of Nell-1 conditional mutant mice. a Schematic diagrams of the genetic construct for floxed Nell-1 generation, the breeding strategy for Nell-1CMVKO mice, and genotyping (lower row); b Nell-1 mRNA and protein levels vary among different organs in Nell-1CMVKO newborn mice (P0); c Nell-1CMVKO newborn mice exhibit significantly decreased Nell-1 in the calvarial bones; d 3D reconstructions of the craniofacial skeleton of Nell-1CMVKO newborn mice demonstrate visible hypoplasia and cranial suture widening. Extreme deficits were also observed in the mandibular bones of Nell-1CMVKO newborn mice, but less frequently (arrow in lower row); e) Quantification of the craniofacial bones as measured by BV/TV, BMD, bone thickness, and suture width confirm their hypoplastic changes. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001; n = 3 for b and c; n = 6 for e

Cell culture

Primary calvarial cells were isolated from neonatal mouse calvarial bones following the established protocol reported in previous studies [4, 25]. CNCCs were isolated from the frontal and nasal bones of cranial vault only and expanded in growth medium containing DMEM + 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) + 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Passage 2 cells were used for all in vitro experiments of this study. Cells were treated with Dickkopf-related protein 1 (DKK-1) or PNU 74654 at the final concentration of 500 ng/ml and 10 μM, respectively, 1 h prior to adding Nell-1 protein at 1000 ng/ml [6, 7, 26]. The osteogenic induction was performed in osteogenic differentiation (OD) medium containing 100 nmol/L dexamethasone, 10 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, and 0.05 mmol/L L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate in growth medium.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

To determine the effect of Nell-1 inactivation on the proliferation of CNCCs, cells from Nell-1Wnt1KO and WT mice were examined either by the Chick-iT EdU Alexa FluorTM 488 Image Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and fluorescence microscopy (OLYMPUS BX51, Japan) for direct visualization or by cell cycle analysis for quantifying the percentage of S (DNA synthesis replication) phase cells using flow cytometry [27]. For apoptosis analyses, the Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) was used for cell staining, followed by flow cytometric analysis for quantifying the percentage of cells at early and late apoptosis by the same protocol as described previously [28].

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and mineralization assays

Assays for CNCCs osteogenic differentiation were adapted from our previous publications using the Leukocytes ALP Staining Kit (86R-1KT, Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). Alizarin Red S (ARS) staining was carried out with 2% Alizarin Red stains (CM-0058, Lifeline, Frederick, MD, USA). The staining intensity of ALP and ARS was measured and quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Western blot and Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described [6, 29]. Nell-1 antibody (1:500) (GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA), active-β-catenin (1:1000) (Cell Signaling, USA), and GAPDH (1:1000) (Cell Signaling, USA) primary antibodies were used at different dilutions. Real-time PCR was performed using the QuantStudioTM 3 real-time PCR System instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as described previously [6]. The primer sequences are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. All data are representative of three experimental sets of cells or the three mice tissue specimens with PCR duplicates and are presented as the fold change.

High-resolution micro-CT analysis

High-resolution micro-CT scanning was performed on mice crania (Skyscan 1176, Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) of neonatal stage for the most samples, and postnatal stage when hydrocephaly became apparent for some samples, respectively. The images were scanned with the setting of 10 μm pixel size, 50 kV Voltage, 500 μA current, 0.5 mm Al filter, 1000 ms exposure time, 0.500 rotation step, and 3 frame averaging. All resulting images were reconstructed by NRecon (Version 1.7.1.0, Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) as described previously [6]. The detailed settings are described in Supplementary Material and Methods. Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using the two-tailed Student’s t test with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

All craniofacial samples of embryonic, neonatal, and postnatal stages were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24–48 h, then processed for paraffin embedding. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining (H&E stain kit, abcam, Cambridge, England) was used per standard protocols, while immunohistochemistry and its semi-quantification were performed as described previously [4, 9]. The working concentration of primary antibodies was set at 2–5 µg/ml in general and the primary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Photomicrographs were acquired using Olympus BX 51 and IX 71 microscopes equipped with Cell Sense digital imaging system (Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All quantifiable data were presented as mean ± SD. The gross assessment was performed with 15 mice of each mutant and wild type group, while the detailed micro-CT and histological analyses were performed with 3 to 6 mice of each genotype for the various parameters. All in vitro experiments were run in triplicate. An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to analyze the data. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The statistical analyses were performed in consultation with the UCLA Statistical Biomathematical Consulting Clinic.

Results

Nell-1 is validated to be a key factor for craniofacial anomalies in new conditional Nell-1 knockout mutants

Upon successful rederivation of the Nell-1flox/flox mouse line, the complete deletion of the Neo cassette was achieved with FLPo-10 deleter mice to eliminate the possible genetic influences to the resultant floxed mutant mice [30]. CMV-Cre [31] and Wnt1-Cre [32] transgenic mice were then used to obtain Nell-1CMVKO mice for the initial screening or Nell-1Wnt1KO mice for comprehensive analyses. Genotyping and Nell-1 gene and protein expression were performed to confirm the knockout in the respective tissues (Fig. 1a–c). Due to the neonatal lethality seen in ENU-induced Nell-1 deficient (END) mice [5, 9], we first selected CMV-Cre as a global knockout strategy to evaluate the newly generated floxed Nell-1 mice. Surprisingly, the majority of Nell-1CMVKO mice were born alive but demonstrated various degrees of hypoplastic craniofacial skeletal defects as characterized by micro-CT scanning (Fig. 1d, e). Notably, in the most severe form, newborn Nell-1 Nell-1CMVKO mice were found still-born and exhibited extreme craniofacial malformations with grossly deficient or absent mandibles, severe frontal and parietal bone defects, and widened anterior fontanels as characterized by Micro-CT analysis (Fig. 1d, bottom row). Thus, the phenotypical changes in Nell-1CMVKO newborns once again indicate the pivotal role of Nell-1 in craniofacial skeletal development, and validates the floxed Nell-1 mouse model.

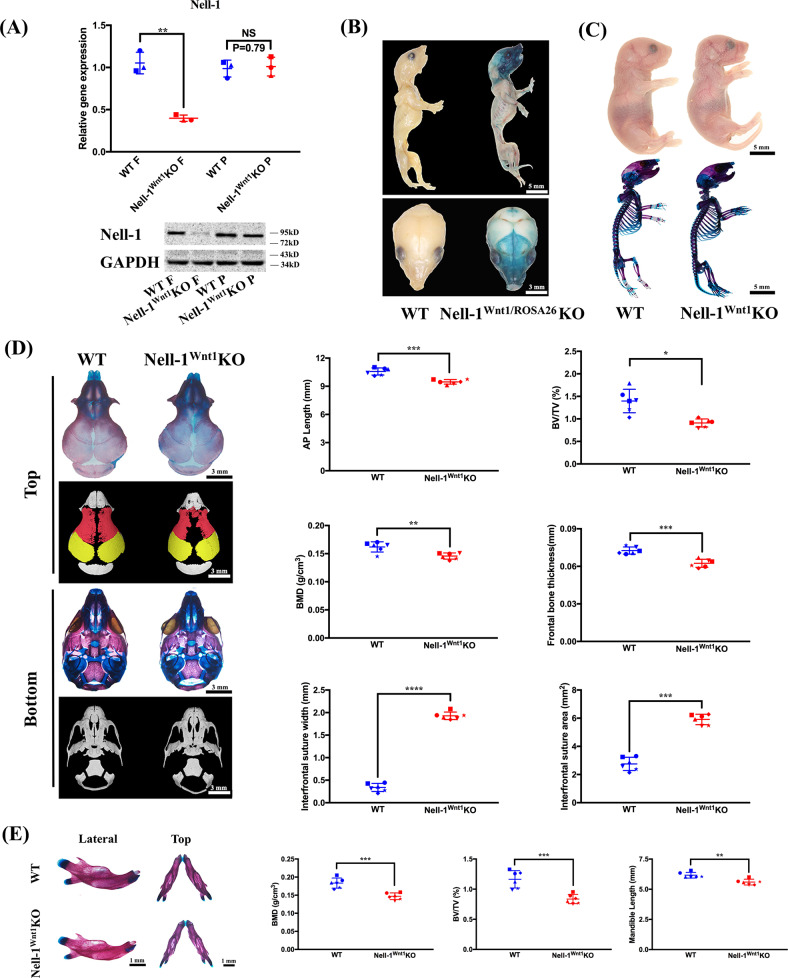

Nell-1 inactivation in CNCCs induces specific craniofacial bone defects with high and consistent penetrance

Given the importance of CNCCs to the development and growth of the craniofacial tissues, Nell-1Wnt1KO mice were used for comprehensive analyses. To confirm and trace the Nell-1 knockout in Wnt1 lineages, the R26R mouse [33] was utilized to make Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO mice for validation in certain experiments. All Nell-1Wnt1KO and Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO mice were born alive without obvious visible abnormalities. Genotyping, Nell-1 gene and protein expression analyses, and X-gal staining were performed to confirm the CNCCs-derived tissue specific knockouts (Fig. 2a, b). Grossly, there were no visible abnormalities of the appendicular and axial bones in Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO newborns as compared with WT littermates (Fig. 2b, c). Detailed analyses of the craniofacial bones (P0) were performed with skeletal staining and micro-CT analyses (Fig. 2d). Nell-1Wnt1KO mice had significantly reduced mineralization and volume of the frontonasal bones (FB), while the parietal bones and cranial base remained unaffected compared to WT littermates. Notably, the size, bone volume over tissue volume (BV/TV), and bone mineral density (BMD) of the mandible of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (P0) were also significantly reduced (Fig. 2e). However, there is no significant different in the comparative micro CT examination of the affected cranial vault vs. MB in Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice in terms of severity of skeletal hypoplasia (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Nell-1 inactivation in CNCCs results in frontonasal bone hypoplasia and micrognathia in Nell-1Wnt1KO newborn mice. a As a result of Nell-1 inactivation in CNCCs, Nell-1 mRNA, and protein expression decreased only in the frontonasal bones (Nell-1Wnt1KO (f) and not in the parietal bones (Nell-1Wnt1KO P); b The craniofacial tissues stained positive for X-gal, with the frontonasal and mandibular bones being particularly targeted in Nell-1Wnt1-R26RKO mice; c gross appearance and skeletal staining showed no visible defects of the appendicular and axial bones in neonatal Nell-1Wnt1KO mice; d detailed analyses of the cranial vault of newborn mice exhibited significant hypoplasia of the frontonasal bones, while the synchondroses of the cranial base were unaffected as demonstrated by skeletal staining, high resolution micro-CT imaging, and quantification as measured by bone volume (BV/TV), bone mineral density (BMD), frontal bone thickness and defect area, the suture width as well as the anteroposterior length of calvarial vault; e Nell-1Wnt1KO mice exhibited significantly smaller and shorter mandibles (micrognathia) with decreased BV/TV and BMD. NS no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001; n = 3 for a; n = 6 for d and (e)

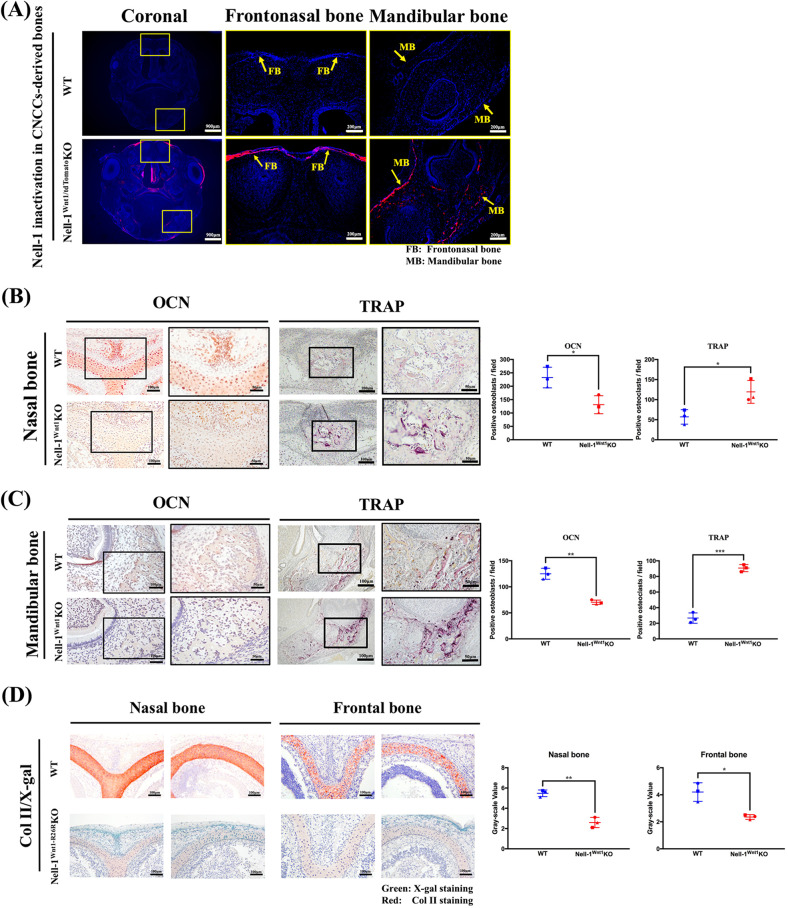

Expectedly, the frontonasal bones (FB) and MB were specifically targeted for Nell-1 inactivation in Nell-1Wnt1-tdTomato KO mice (P0) (Fig. 3a). Osteocalcin (OCN) immunostaining clearly revealed decreased osteogenic properties in both the frontonasal and MB of Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice (P0) (Fig. 3b, c). Interestingly, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining exhibited more positive cells in both the frontonasal and MB of Nell-1Wnt1 KO mice (Fig. 3b, c). Histomorphometric analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of osteoblasts and an increase in the number of osteoclasts in affected bones (Fig. 3b, c). In sharp contrast to WT littermates, Nell-1Wnt1-R26RKO mice had significantly less Collagen type II (Col2) in the X-gal positive-stained cartilaginous wall and septum of the nasal cavity under the FB (P0) (Fig. 3d). Overall, specific Nell-1 inactivation in CNCCs consistently resulted in frontonasal skeletal hypoplasia and micrognathia in newborn mice with complete penetrance.

Fig. 3.

Nell-1Wnt1KO newborn mice demonstrate defective osteochondrogenesis in CNCC-derived bones. a Cell lineage tracking in Nell-1Wnt1-tdTomatoKO mice clearly showed red fluorescence (yellow arrows) in the frontonasal bones (FB) and mandibular bones (MB) which are derived from Wnt1 expressing CNCC lineages; b, c More OCN positive cells were observed in the osteogenic front of the calvarial bone plate and mandibular bones in WT samples than in Nell-1Wnt1KO samples. In contrast to OCN staining, TRAP positive staining showed a drastic increase in both the frontonasal and mandibular bones of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice. The distinct correlation of OCN and TRAP staining in these bones was further revealed by quantitative analyses between WT and Nell-1Wnt1KO mice; d The maturation of CNCC-derived cartilaginous tissues was severely inhibited in Nell-1Wnt1-R26RKO mice with evidence of extremely low levels of Collagen type II matrix. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; n = 3 for b–d

Nell-1Wnt1KO mice develop postnatal hydrocephalus at significantly higher rates

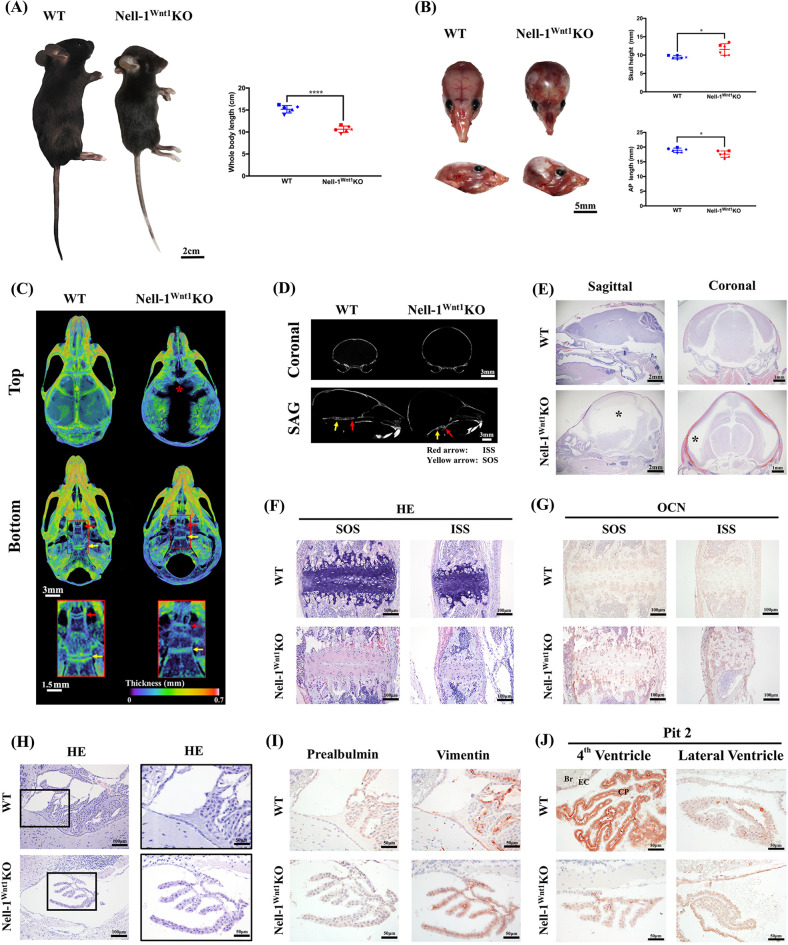

In contrast to the neonatal lethality of END mice [5], the majority of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice are born full-term, fertile, and live to maturity without visible clinical manifestations different from WT littermates. However, among Nell-1Wnt1KO mice, 5.4% of young adult mice ranging from 21 to 48 days old developed classical domed head phenotypes of hydrocephalus (Fig. 4a, b), a rate significantly higher than the <0.01% prevalence of spontaneous hydrocephalus in C57BL/6J mice (JAX Notes@ https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/1991/april/spontaneous-hydrocephalus-in-inbred-strains-of-mice) (**P < 0.01). Notably, hydrocephalic mice were characterized by smaller and less mineralized FB with widened frontal, sagittal, and coronal sutures on the calvarial vault along with various degrees of premature ossification of intrasphenoidal synchondrosis (ISS) and/or sphenoid-occipital synchondrosis (SOS) (Fig. 4c, d). At the tissue level, profound dilation of the brain ventricles along with compressed and thinner brain cortex layers were observed, likely secondary to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulation (Fig. 4e). Histology and OCN immunohistochemistry of the cranial base supported premature fusion/ossification of the synchondroses (Fig. 4f, g and Supplementary Fig. 2A). The epithelial cells of the choroid plexus (CP) were enlarged with rich cytoplasm, and the ependymal cells were flattened with focal loss of apical structures (Fig. 4h). Vimentin, a marker of ependymal cells [34], was undetectable in the flattened ependymal cells and/or mis-expressed in some of the enlarged CP epithelial cells, while the expression of prealbumin/transthyretin (TTR), a specific marker of CP epithelial cells [35], was significantly lower or even undetectable in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 2B). Next, a type III Na+-dependent inorganic phosphate transporter, Pit-2, was explored due to the fact that it was one of the phosphate transporters that Nell-1 used to increase pre-osteoblast mineralization [36] and its causative role in hydrocephalus in Pit-2 deficient mice [37]. The intracellular protein level of Pit-2 was significantly reduced in CP epithelial cells of the fourth ventricle, but slightly elevated in both swollen CP epithelial cells and flattened ependymal cells of the lateral ventricle in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as compared with those cells in WT mice (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 2C). These results may reflect the functional properties and distinct pathological changes of CP epithelial and ependymal cells at different locations of brain ventricular system under hydrocephalic condition in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice.

Fig. 4.

Nell-1Wnt1KO young adult mice develop postnatal hydrocephalus. a The gross appearance of the whole body and b skulls of young adult WT and affected Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (P32) showed classic dome-shaped heads in KO specimens. The skull length (Anteroposterior length, AP), skull height, and body length were measured, showing significant features of hydrocephalus; c Micro-CT imaging with color-coded bone density heat-maps showed distinct decreases in the size and mineral density of the frontonasal bones, defects of the frontal bones (*), widened cranial sutures, premature ossification of the intraphenoidal synchondrosis (ISS, red arrow) and sphenoid-occipital synchondrosis (SOS, yellow arrow) in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice compared with WT controls; d 2D coronal and sagittal X-ray images demonstrated an enlarged hydrocephalic skull profile and premature ossification/fusion of the synchondrosis in the cranial base (arrows) in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice; (e) Histologically, the typical morphological changes of the dilated brain ventricles (*) and the compressed brain cortex in hydrocephalus were revealed from the sagittal and coronal views. f At the cellular level, the composition of the cartilaginous matrix corroborates the ossified synchondrosis observed in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as compared to WT controls; (g) stronger OCN immunostaining was observed in the hydrocephalic samples over WT controls; h The swollen epithelial cells of the choroid plexus were readily observed in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO specimens; i Immunohistochemistry of the markers of epithelial cell of the choroid plexus, prealbumin, and the ependymal cells, vimentin, were performed respectively. The misplaced expression pattern of vimentin was observed in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO specimens; (j) Immunohistochemistry of Pit-2 exhibited dysregulation among CP epithelial and ependymal cells of the dilated brain ventricle and the fourth ventricle in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO specimens. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.001; n = 6 for a and b; n = 3 for i and j

To determine if hydrocephalus occurred as a congenital condition, the embryos at E9.5, 14.5, and 17.5 were subsequently collected and analyzed although we did not observe noticeable hydrocephalic manifestations in any newborn mice. Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO embryos were stained positive by X-gal to display areas of Nell-1 inactivation and to assist lineage tracing (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Grossly, there were no visible malformations of the craniofacial tissues in either Wnt1 expressing cell lineage and other origins in Nell-1Wnt1-R26R KO embryos. At the tissue level, the embryonic and neonatal Nell-1Wnt1KO mice did not demonstrate any pathological changes of the brain ventricles, although Nell-1 inactivation did occur in CSF producing cells from Nell-1Wnt1-tdTomato KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). Micro-CT imaging exhibited obvious delayed development of the MB and cranial vault in E17.5 Nell-1Wnt1KO embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Immunostaining of OCN and TRAP staining clearly demonstrated that inactivation of Nell-1 in CNCCs has a significant impact on both osteoblastic and osteoclastic activities, resulting in delayed formation and mineralization of the MB even at E17.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3E).

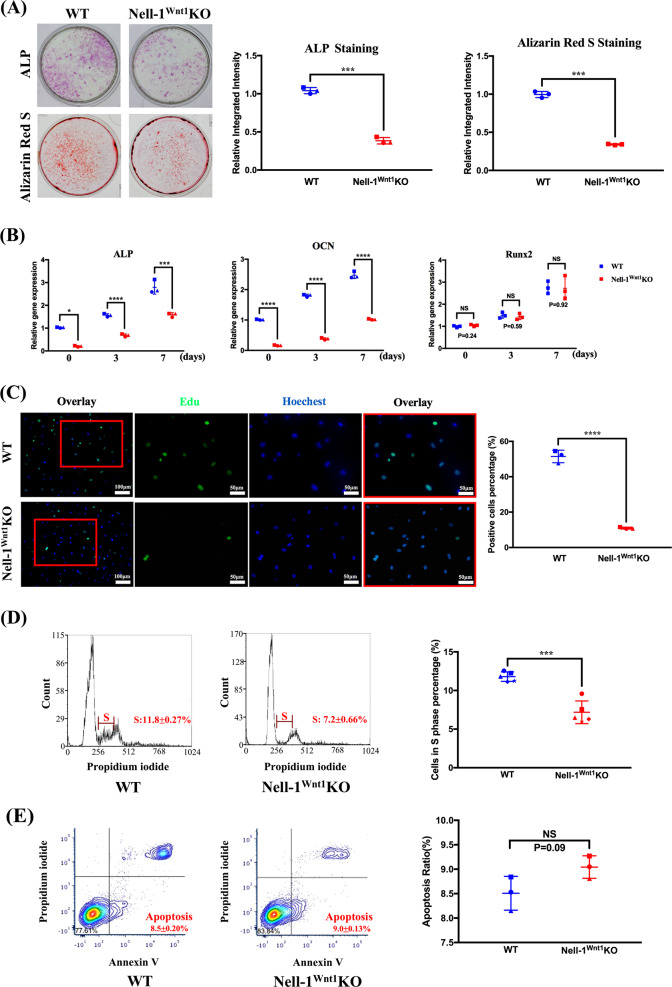

Nell-1 is required for the full osteogenic differentiation potential of CNCCs

Clearly, the osteogenic potential of primary calvarial cells was significantly diminished in Nell-1 KO cells as evidenced by decreased expression of the osteogenic marker genes, OCN, Osteopontin (OPN), and Runx2 (Supplementary Fig. 4A), lower ALP at day 5, and reduced intensity of mineralization at day 21 using Alizarin red staining (Supplementary Fig. 4B). The later stage inactivation of Nell-1 by adenoviral CMV-Cre delivery to Nell-1flox/flox calvarial cells did not affect mineralization as compared with the earlier stage (Day 9) inactivation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similarly, the CNCCs isolated from the FB of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice also exhibited significant reduction of ALP activity at day 7, and reduction of mineralization at day 21 compared with CNCCs from WT mice (Fig. 5a). The quality control of isolated CNCCs from non-cranial neural crest calvarial cells was monitored at two steps: (1) during physical separation, and (2) during Nell-1 gene expression profiling (Fig. 2a). The gene expression of the major osteogenic markers, ALP and OCN, but not Runx2, was significantly downregulated in CNCCs of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (Fig. 5b), but not in the parietal bone-derived calvarial cells from same batch of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as compared with cells from WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 6). The EdU cell proliferation assay revealed that Nell-1Wnt1KO CNCCs had significantly less proliferative potential (Fig. 5c), which was supported with cell cycle analysis showing much lower DNA synthesis replication phase (S phase) CNCCs in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (7.2 ± 0.66%) than in WT mice (11.8 ± 0.27%) (Fig. 5d). In contrast, the apoptotic cells were slightly greater in Nell-1Wnt1KO CNCCs (9.0 ± 0.13%) over those of the WT (8.5 ± 0.20%) (Fig. 5e), while the gating strategies for flow cytometry analyses were strictly enforced (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, Nell-1 significantly modulates the proliferation and osteogenic potential of CNCCs, which correlate with the abnormal craniofacial skeletal phenotypes observed in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice.

Fig. 5.

Nell-1 inactivation reduces CNCCs osteogenic capacity and cell proliferation. The CNCCs isolated from Nell-1Wnt1KO newborn mice demonstrated significantly impaired osteogenic capacity as demonstrated by a ALP staining and mineralization, and b gene expression of the osteogenic markers ALP, OCN, and Runx2; c in vitro EdU labeling exhibited significantly reduced positive cells from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice, and d flow cytometry cell cycle analyses further confirmed the lower proliferative cell populations in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice. Specifically, CNCCs in the DNA synthesis phase (S phase) of WT mice (11.8 ± 0.27%) were significantly more than that of Nell-1Wnt1KO (7.2 ± 0.66%). e While the rates of early apoptosis of CNCCs measured by flow cytometry from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (9.0 ± 0.13%) was slightly higher than that of WT mice (8.5 ± 0.20%), no statistically significant difference was found. NS no significance; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is downregulated in Nell-1 deficient CNCCs and its craniofacial bone derivatives

Previously, Nell-1 has been reported as a novel agonist of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway due to its pro-osteogenic properties [29]. The critical impact of the Wnt signaling pathway has also been identified in the development and growth of the craniofacial skeletal tissues [38]. Therefore, it is meaningful to investigate the changes of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the context of CNCC specific Nell-1 KO mice for craniofacial malformations. Apparently, the inactivation of Nell-1 is responsible for the lower basal level of active β-catenin and the gene expressions of Wnt/β-catenin downstream targets, C-myc and Cyclin D, in CNCCs from Nell-1Wnt1KO newborns (Fig. 6a). CNCCs from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice exhibited significantly lower expression patterns of Wnt signaling molecules and reduced osteogenic markers, ALP and OCN, compared with those from WT mice (Fig. 6b). Immunostaining of active β-catenin from CNCCs-derived bone tissue sections further demonstrated the significantly defective Wnt canonical signaling pathway in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice (P0) (Fig. 6c). Significantly, recombinant Nell-1 protein can partially rescue not only the defective Wnt signaling molecules, but also osteogenic differentiation to a level close to that in WT CNCCs at 1000 ng/ml that was empirically determined with primary CNCCs (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 8). Nevertheless, Nell-1 protein can also partially rescue osteogenic deficits and elevate Wnt downstream targets of gene expression in WT CNCCs that were treated with Wnt signaling inhibitor [39, 40], DKK-1 that interferes interaction of Wnt ligands and receptors by binding to lrp5/6 and Kremen proteins, but not in WT CNCCs being treated with PNU 74654, which prevents Tcf from binding to β-catenin (Fig. 6d–f). As a result, Nell-1 is a pivotal component of the canonical Wnt pathway in regulating CNCC osteogenesis. However, it remains unclear whether Nell-1 uses distinct mechanisms from Wnt ligands in achieving its regulatory role.

Fig. 6.

Nell-1 inactivation significantly alters Wnt/β-catenin signaling in CNCCs and cranial bone derivatives of newborn mice. a Gene expression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling molecules showed a significant decrease in the β-catenin downstream targets, C-myc and Cyclin D, but β-catenin itself remained unchanged in CNCCs from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as evidenced by qPCR analysis (upper row). However, active β-catenin protein was significantly reduced in CNCCs from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as evidenced by Western blot analysis (lower row). b A similar trend of reduced gene expression of osteogenic markers along with downstream targets of β-catenin was observed during osteogenic induction of CNCCs from both WT and Nell-1Wnt1KO mice. Notably, administration of exogenous Nell-1 can partially compensate for the defective osteogenic capacity of CNCCs from Nell-1Wnt1KO mice. c The reduced amounts of active β-catenin protein was also confirmed in the frontal and mandibular bones of Nell-1Wnt1KO mice, indicating the essential role of Nell-1 in Wnt/β-catenin signaling for osteogenesis. d DKK-1, an inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that interferes with Wnt ligand binding to its receptors, also resulted in reduced gene expression of osteogenic markers (ALP and OCN), and β-catenin downstream targets (C-myc and Cyclin D). However, exogenous Nell-1 can partially rescue the loss of osteogenic differentiation by increasing Wnt/β-catenin signaling. e Gene expressions of osteogenic markers (ALP and OCN), and the β-catenin downstream targets (C-myc and Cyclin D) were severely blocked with PNU74654, an inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that prevents Tcf binding to β-catenin. Administration of exogenous Nell-1 had no compensatory effects to this inhibition in Wnt/β-catenin signaling and osteogenic differentiation in CNCCs. f Moreover, recombinant Nell-1 protein is capable of rescuing the terminal osteogenic differentiation of CNCCs treated with DKK-1 to a certain extent. However, recombinant Nell-1 protein cannot rescue the terminal osteogenic differentiation of CNCCs treated with PNU74654. NS no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001

Discussion

With defined conditional knockout of Nell-1 in Wnt1 expressing cells, the CNCC-derived craniofacial skeletons of the frontonasal and MB exhibited lower BMD and reduced bone volume in embryonic and neonatal Nell-1Wnt1KO mice at complete penetrance. The similar craniofacial skeletal hypoplasia phenotype was also identified in the majority of Nell-1CMVKO mice except for some severe cases. This further implicated the prominent role of Nell-1 in craniofacial skeletal tissues. Surprisingly, a relatively high prevalence of hydrocephalus was identified in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice at postnatal 30–40 days. This is the first report demonstrating the association of Nell-1 with hydrocephalus, which has shown to be frequently associated with abnormalities of the choroid plexus and ependymal cells as well as corticogenesis in murine models [22, 41–43]. This new finding may indicate possible functional impact by Nell-1 on choroid plexus epithelial cells and ependymal cells of the central nervous system in addition to its prominent pro-osteochondral properties, thereby warranting further investigation. The global deletion of Nell-1 in END mice resulted in neonatal lethality with severe cartilage and bone deformities including CCD-like phenotypes in craniofacial tissues [5, 9]. In contrast, the majority of Nell-1CMVKO mice survived at birth with various degrees of craniofacial skeletal hypoplasia. The phenotypic discrepancies between END and Nell-1CMVKO mice, as well as among Nell-1CMVKO mice themselves, may be attributable to different degrees of inactivation/diminishment of the Nell-1 molecule because Cre activation and Cre-loxP recombination are highly influenced by promotor activity of the CMV driver mouse [5, 11, 44, 45]. Consequently, in comparison to the CMV-Cre mouse line, the Wnt1-Cre line has been shown to be a more reliable tool to study CNCC specific knockouts [16, 22, 32].

The hypoplastic skeletal phenotype in CNCC derivatives- frontonasal and MB, was readily noticeable at late embryonic stages and became more significant in neonatal Nell-1Wnt1KO mice as measured by micro-CT and histological analyses. Similar to previous findings with primary calvarial cells from END mice [9, 46], the osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of CNCCs were impaired by the cell specific knockout of Nell-1. Significantly, the application of recombinant Nell-1 can compensate for the loss of osteogenic differentiation of Nell-1Wnt1KO CNCCs. Thus, Nell-1 is an essential player for the full osteogenic potential of CNCCs and for normal bone formation during craniofacial skeletal development. Mechanistically, Nell-1, as a direct downstream target of Runx2 [47], has been identified to involve multiple major signaling pathways including MAPK (ERK/JNK) [46, 48, 49], Wnt/β-catenin [6, 29], Integrin β1/FAK [50, 51], and IHH [52, 53] due to its osteogenic role in various experimental settings [54, 55]. Since the inactivation of β-catenin in Wnt1 expressing cell linages resulted in severe craniofacial skeletal defects [16], the influence of Nell-1 inactivation on Wnt/β-catenin signaling during osteogenic differentiation of CNCCs was chosen as a primary focus of the mechanistic study. Nell-1Wnt1KO CNCCs exhibited significantly reduced gene expression of the downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin. The application of recombinant Nell-1 can compensate the reduction of these genes’ expression not only in Nell-1Wnt1KO CNCCs, but also in WT CNCCs treated with Wnt inhibitors that act at two different points of the Wnt signaling pathway [39, 40]. Clearly, our data indicate that the major point/site of Nell-1 in activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling would be downstream of Wnt receptor/co-receptors in CNCCs. This is in agreement with the latest finding of Cntnap4, a cell surface receptor of Nell-1, to be required for Nell-1′s osteogenic effects in primary calvarial cells and MC3T3-E1 cells. Specifically, Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation and osteoblastic differentiation by Nell-1 stimulation were attenuated in MC3T3-E1 cells with Cntnap4 knockdown [8]. Collectively, these data indicate that Nell-1 is not only a pivotal component of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, but also a novel agonist of Wnt signaling [6, 29] through interacting with its specific receptor and/or other potential binding partners including integrin β1 in modulating the osteogenic potential of post-migratory CNCCs during craniofacial skeletal development. Apparently, a more complex mechanism is expected as a result from possible crosstalk among the aforementioned signaling pathways [55, 56]. Alternatively, Nell-1 may also employ mechanisms involving β-catenin irrelevant to Wnt signaling as suggested in the β-cateninWnt1 KO mice model [16, 57].

Interestingly, Nell-1 inactivation in Wnt1 expressing cell lineages was associated with postnatal hydrocephalus for the first time. As defined by the International Hydrocephalus Working Group, hydrocephalus is “an active distension of the ventricular system resulting from inadequate passage of CSF from its point of production within the cerebral ventricles to its point of absorption into the systemic circulation” [58]. Thus, the inadequate production and absorption of CSF or the abnormal passage of CSF circulation may result in hydrocephalus. In agreement with CNCCs being a multipotent mesenchymal stem cell population for neural and craniofacial tissues [59], the choroid plexus where CSF was produced and the ependymal cells which are the ciliated lining cells of the brain ventricles in charge of directing CSF flow were reported to be derived from Wnt1-expressing cell populations of the dorsal midline [42, 60, 61] and experimentally verified using Nell-1Wnt1-tdTomato KO mouse in this study. This led us to examine whether these structures were affected in Nell-1Wnt1KO mice that may account for the development of hydrocephalus. Likely, the structural abnormalities and misplaced expression of vimentin and pre-albumin/transthyretin in the degenerative choroid plexus epithelial cells and ependymal cells are part of the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus in postnatal Nell-1Wnt1KO mice. The high prevalence of premature ISS fusion in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice may implicate the considerable impacts of skeletal deformities or abnormal mechanical forces on the developing brain to hydrocephalus development as suggested in other relevant studies [62, 63]. The seemingly paradoxical results of premature ossification of the ISS with overall cranial skeletal hypoplasia in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice need to be further investigated in future studies. Furthermore, our data on the significant alterations of Pit expression in hydrocephalic Nell-1Wnt1KO mice may implicate that the dysregulation of phosphate import from the CSF is a part of critical mechanisms in the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus [37, 64]. Coincidentally, there were several conditional gene inactivation models using Wnt1-Cre resulting in hydrocephalus including Huntingtin protein [22], Pax3 transcription factor [65], and RFX3 [41]. Likely, this is due to the cumulative insults by inactivation of these functional molecules to the subcommissural organ, ependymal cells, and epithelial cells of the CP that originate from early Wnt1 expressing neuroepithelial cells [20, 24]. Nevertheless, L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1cam) was recognized as a highly affected gene for X-linked congenital hydrocephalus in humans [66], and its underlying mechanism was proposed as the loss of L1cam function affecting radial migration in corticogenesis in a murine model [43]. Therefore, the exact mechanism of the development of hydrocephalus may be more complex than what has been reported. It is significant that Nell-1 becomes a newly identified factor in contributing to the pathogenesis of postnatal hydrocephalus. The dual role of Nell-1 in osteochondral and neural tissue development and growth as evidenced in this study may provide a new research avenue to the growing field of neuroskeletal biology [3, 54, 67–70].

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs Dan Pan and Zhong Zheng at the University of California, Los Angeles for their excellent technical assistance and scientific input. This study was supported by the NIH-NIAMS (grants R01AR066782, R01AR068835, R01AR061399), NIH-NIDCR (grant K08DE026805), UCLA/NIH CTSI (grant UL1TR000124), the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (“NASA”, GA- 2014–154), the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81670972, 81400538], and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [LY19H140002].

Author contributions

XZ, KT, CS, and HW conceived and designed the study, interpreted data, and approved the manuscript; XC, HW, MY, and XZ executed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; CK, HQ, PH, WJ, XL, and EC collected and analyzed the data and edited the manuscript; RBN, CY, LB, JS, and JHK provided research materials and collected data.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

XZ, KT, and CS are inventors of Nell-1 related patents. XZ, KT, and CS are founders and/or previous board members of Bone Biologics Inc./Bone Biologics Corp., which sublicenses Nell-1 patents from the UC Regents, which also hold equity in the company. XZ, KT, and CS = Xinli Zhang, Kang Ting, Chia Soo

Footnotes

Edited by M. Blagosklonny

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaoyan Chen, Huiming Wang, Mengliu Yu

These authors contributed equally: Kang Ting, Xinli Zhang, Chia Soo

Change history

3/23/2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41418-020-0529-9

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-019-0427-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Matsuhashi S, Noji S, Koyama E, Myokai F, Ohuchi H, Taniguchi S, et al. New gene, nel, encoding a M(r) 93 K protein with EGF-like repeats is strongly expressed in neural tissues of early stage chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:212–22. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe TK, Katagiri T, Suzuki M, Shimizu F, Fujiwara T, Kanemoto N, et al. Cloning and characterization of two novel human cDNAs (NELL1 and NELL2) encoding proteins with six EGF-like repeats. Genomics. 1996;38:273–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting K, Vastardis H, Mulliken JB, Soo C, Tieu A, Do H, et al. Human NELL-1 expressed in unilateral coronal synostosis. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:80–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Kuroda S, Carpenter D, Nishimura I, Soo C, Moats R, et al. Craniosynostosis in transgenic mice overexpressing Nell-1. J Clin Investig. 2002;110:861–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI15375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai J, Shannon ME, Johnson MD, Ruff DW, Hughes LA, Kerley MK, et al. Nell1-deficient mice have reduced expression of extracellular matrix proteins causing cranial and vertebral defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1329–41. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James AW, Shen J, Zhang X, Asatrian G, Goyal R, Kwak JH, et al. NELL-1 in the treatment of osteoporotic bone loss. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7362. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qi H, Kim JK, Ha P, Chen X, Chen E, Chen Y, et al. Inactivation of Nell-1 in chondrocytes significantly impedes appendicular skeletogenesis. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2018;34:533–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Li C, Zheng Z, Ha P, Chen X, Jiang W, Sun S, et al. Neurexin superfamily cell membrane receptor contactin-associated protein like-4 (Cntnap4) is involved in neural EGFL-Like 1 (Nell-1)-responsive osteogenesis. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:1813–25. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Ting K, Pathmanathan D, Ko T, Chen W, Chen F, et al. Calvarial cleidocraniodysplasia-like defects with ENU-induced Nell-1 deficiency. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:61–6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240c8c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bronner-Fraser M. Origins and developmental potential of the neural crest. Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:405–17. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo-Rogers HL, Smithers LE, Yakob W, Liu KJ. New directions in craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2010;341:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr., Han J, Rowitch DH, et al. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douarin NL, Kalcheim C. The Neural Crest. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom; 1999.

- 16.Brault V, Moore R, Kutsch S, Ishibashi M, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, et al. Inactivation of the beta-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 2001;128:1253–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon AP, Bradley A. The Wnt-1 (int-1) proto-oncogene is required for development of a large region of the mouse brain. Cell. 1990;62:1073–85. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90385-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Cis-acting regulatory sequences governing Wnt-1 expression in the developing mouse CNS. Development. 1994;120:2213–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roelink H, Nusse R. Expression of two members of the Wnt family during mouse development-restricted temporal and spatial patterns in the developing neural tube. Genes Dev. 1991;5:381–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu W, Mirando AJ, Yu HM. Manipulating gene activity in Wnt1-expressing precursors of neural epithelial and neural crest cells. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:338–45. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106–16. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich P, Shanmugasundaram R, Shuyu E, Dragatsis I. Congenital hydrocephalus associated with abnormal subcommissural organ in mice lacking huntingtin in Wnt1 cell lineages. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:142–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamauchi Y, Abe K, Mantani A, Hitoshi Y, Suzuki M, Osuzu F, et al. A novel transgenic technique that allows specific marking of the neural crest cell lineage in mice. Dev Biol. 1999;212:191–203. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murdoch B, DelConte C, Garcia-Castro MI. Pax7 lineage contributions to the mammalian neural crest. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong GL, Cohn DV. Target cells in bone for parathormone and calcitonin are different: enrichment for each cell type by sequential digestion of mouse calvaria and selective adhesion to polymeric surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3167–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leal LF, Bueno AC, Gomes DC, Abduch R, de Castro M, Antonini SR. Inhibition of the Tcf/beta-catenin complex increases apoptosis and impairs adrenocortical tumor cell proliferation and adrenal steroidogenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43016–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobberger JW, Sramkoski RM, Stefan T, Woost PG. Multiparameter cell cycle analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1678:203–47. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7346-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C, Tanjaya J, Shen J, Lee S, Bisht B, Pan HC, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma knockdown impairs bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced critical-size bone defect repair. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:648–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen J, James AW, Zhang X, Pang S, Zara JN, Asatrian G, et al. Novel Wnt regulator NEL-like molecule-1 antagonizes adipogenesis and augments osteogenesis induced by bone morphogenetic protein 2. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:419–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Wang C, Sun H, LeRoith D, Yakar S. High-efficient FLPo deleter mice in C57BL/6J background. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–1. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis AE, Vasudevan HN, O’Neill AK, Soriano P, Bush JO. The widely used Wnt1-Cre transgene causes developmental phenotypes by ectopic activation of Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2013;379:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoller JZ, Degenhardt KR, Huang L, Zhou DD, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Cre reporter mouse expressing a nuclear localized fusion of GFP and beta-galactosidase reveals new derivatives of Pax3-expressing precursors. Genesis. 2008;46:200–4. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamazaki Y, Hirai Y, Miyake K, Shimada T. Targeted gene transfer into ependymal cells through intraventricular injection of AAV1 vector and long-term enzyme replacement via the CSF. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5506. doi: 10.1038/srep05506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baehr C, Reichel V, Fricker G. Choroid plexus epithelial monolayers-a cell culture model from porcine brain. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2006;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowan CM, Zhang X, James AW, Kim TM, Sun N, Wu B, et al. NELL-1 increases pre-osteoblast mineralization using both phosphate transporter Pit1 and Pit2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:351–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallingford MC, Chia JJ, Leaf EM, Borgeia S, Chavkin NW, Sawangmake C, et al. SLC20A2 deficiency in mice leads to elevated phosphate levels in cerbrospinal fluid and glymphatic pathway-associated arteriolar calcification, and recapitulates human idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:64–76. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikeya M, Lee SM, Johnson JE, McMahon AP, Takada S. Wnt signalling required for expansion of neural crest and CNS progenitors. Nature. 1997;389:966–70. doi: 10.1038/40146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Sarosi I, Cattley RC, Pretorius J, Asuncion F, Grisanti M, et al. Dkk1-mediated inhibition of Wnt signaling in bone results in osteopenia. Bone. 2006;39:754–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan M, Li G, An J. Discovery of small molecule inhibitors of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway by targeting beta-catenin/Tcf4 interactions. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242:1185–97. doi: 10.1177/1535370217708198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baas D, Meiniel A, Benadiba C, Bonnafe E, Meiniel O, Reith W, et al. A deficiency in RFX3 causes hydrocephalus associated with abnormal differentiation of ependymal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1020–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Louvi A, Wassef M. Ectopic engrailed 1 expression in the dorsal midline causes cell death, abnormal differentiation of circumventricular organs and errors in axonal pathfinding. Development. 2000;127:4061–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itoh K, Fushiki S. The role of L1cam in murine corticogenesis, and the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus. Pathol Int. 2015;65:58–66. doi: 10.1111/pin.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loser P, Jennings GS, Strauss M, Sandig V. Reactivation of the previously silenced cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter in the mouse liver: involvement of NFkappaB. J Virol. 1998;72:180–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.180-190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K. Vagaries of conditional gene targeting. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:665–8. doi: 10.1038/ni0707-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Ting K, Bessette CM, Culiat CT, Sung SJ, Lee H, et al. Nell-1, a key functional mediator of Runx2, partially rescues calvarial defects in Runx2(+/-) mice. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:777–91. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Truong T, Zhang X, Pathmanathan D, Soo C, Ting K. Craniosynostosis-associated gene nell-1 is regulated byrunx2. J Bone Miner Res: Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:7–18. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen F, Walder B, James AW, Soofer DE, Soo C, Ting K, et al. NELL-1-dependent mineralisation of Saos-2 human osteosarcoma cells is mediated via c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway activation. Int Orthop. 2012;36:2181–7. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1590-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bokui N, Otani T, Igarashi K, Kaku J, Oda M, Nagaoka T, et al. Involvement of MAPK signaling molecules and Runx2 in the NELL1-induced osteoblastic differentiation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasebe A, Nakamura Y, Tashima H, Takahashi K, Iijima M, Yoshimoto N, et al. The C-terminal region of NELL1 mediates osteoblastic cell adhesion through integrin alpha3beta1. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen J, James AW, Chung J, Lee K, Zhang JB, Ho S, et al. NELL-1 promotes cell adhesion and differentiation via Integrinbeta1. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:3620–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.James AW, Pan A, Chiang M, Zara JN, Zhang X, Ting K, et al. A new function of Nell-1 protein in repressing adipogenic differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li CS, Zhang X, Peault B, Jiang J, Ting K, Soo C, et al. Accelerated chondrogenic differentiation of human perivascular stem cells with NELL-1. Tissue Eng Part A. 2016;22:272–85. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Zara J, Siu RK, Ting K, Soo C. The role of NELL-1, a growth factor associated with craniosynostosis, in promoting bone regeneration. J Dent Res. 2010;89:865–78. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pakvasa M, Alverdy A, Mostafa S, Wang E, Fu L, Li A, et al. Neural EGF-like protein 1 (NELL-1): Signaling crosstalk in mesenchymal stem cells and applications in regenerative medicine. Genes Dis. 2017;4:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Li YP, Paulson C, Shao JZ, Zhang X, Wu M, et al. Wnt and the Wnt signaling pathway in bone development and disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2014;19:379–407. doi: 10.2741/4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:514–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4%3C514::AID-JCB4%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tully HM, Dobyns WB. Infantile hydrocephalus: a review of epidemiology, classification and causes. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:359–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takashima Y, Era T, Nakao K, Kondo S, Kasuga M, Smith AG, et al. Neuroepithelial cells supply an initial transient wave of MSC differentiation. Cell. 2007;129:1377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Awatramani R, Soriano P, Rodriguez C, Mai JJ, Dymecki SM. Cryptic boundaries in roof plate and choroid plexus identified by intersectional gene activation. Nat Genet. 2003;35:70–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernandez-Llebrez P, Grondona JM, Perez J, Lopez-Aranda MF, Estivill-Torrus G, Llebrez-Zayas PF, et al. Msx1-deficient mice fail to form prosomere 1 derivatives, subcommissural organ, and posterior commissure and develop hydrocephalus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:574–86. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.6.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cinalli G, Sainte-Rose C, Kollar EM, Zerah M, Brunelle F, Chumas P, et al. Hydrocephalus and craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:209–14. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.2.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanavaki A, Jenny B, Hanquinet S. Chiari I malformation associated with premature unilateral closure of the posterior intraoccipital synchondrosis in a preterm infant. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;11:658–60. doi: 10.3171/2013.3.PEDS12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen N, Autzen JK, Pedersen L. Slc20a2 is critical for maintaining a physiologic inorganic phosphate level in cerebrospinal fluid. Neurogenetics. 2016;17:125–30. doi: 10.1007/s10048-015-0469-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou HM, Conway SJ. Restricted Pax3 deletion within the neural tube results in congenital hydrocephalus. J Dev Biol. 2016;4:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Adle-Biassette H, Saugier-Veber P, Fallet-Bianco C, Delezoide AL, Razavi F, Drouot N, et al. Neuropathological review of 138 cases genetically tested for X-linked hydrocephalus: evidence for closely related clinical entities of unknown molecular bases. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:427–42. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang X, Cowan CM, Jiang X, Soo C, Miao S, Carpenter D, et al. Nell-1 induces acrania-like cranioskeletal deformities during mouse embryonic development. Lab Invest. 2006;86(Jul):633–44. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patel MS, Elefteriou F. The new field of neuroskeletal biology. Calcif tissue Int. 2007;80:337–47. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spencer GJ, Hitchcock IS, Genever PG. Emerging neuroskeletal signalling pathways: a review. FEBS Lett. 2004;559:6–12. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura R, Nakamoto C, Obama H, Durward E, Nakamoto M. Structure-function analysis of Nel, a thrombospondin-1-like glycoprotein involved in neural development and functions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3282–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.