Abstract

With the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing barriers to the collection and transport of donor cells, it is often necessary to collect and cryopreserve grafts before initiation of transplantation conditioning. The effect on transplantation outcomes in nonmalignant disease is unknown. This analysis examined the effect of cryopreservation of related and unrelated donor grafts for transplantation for severe aplastic anemia in the United States during 2013 to 2019. Included are 52 recipients of cryopreserved grafts who were matched for age, donor type, and graft type to 194 recipients who received noncryopreserved grafts. Marginal Cox regression models were built to study the effect of cryopreservation and other risk factors associated with outcomes. We recorded higher 1-year rates of graft failure (hazard ratio [HR], 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.17 to 4.35; P = .01) and of 1-year overall mortality (HR, 3.13; 95% CI, 1.60 to 6.11; P = .0008) after transplantation of cryopreserved compared with noncryopreserved grafts, with adjustment for sex, performance score, comorbidity, cytomegalovirus serostatus, and ABO blood group match. The incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease did not differ between the 2 groups. Adjusted probabilities of 1-year survival were 73% (95% CI, 60% to 84%) in the cryopreserved graft group and 91% (95% CI, 86% to 94%) in the noncryopreserved graft group. These data support the use of noncryopreserved grafts whenever possible in patients with severe aplastic anemia.

Keywords: Cryopreserved graft, Severe aplastic anemia

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic has triggered an unprecedented worldwide healthcare crisis. It also has impacted the world economy and disrupted travel across international borders and within countries. These travel restrictions, combined with potentially reduced HCT donor availability (due to infection, quarantine, and constraints on travel to collection centers) and complex allograft processing logistics (eg, donor assessment, collection, on-schedule delivery for fresh infusion), directly impact the ability to infuse fresh donor cells into intended recipients on the scheduled day of transplantation. Consequently, the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) [1] and the National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match (NMDP) [2] have issued strong recommendations that unrelated donor products should be delivered and cryopreserved at transplantation centers before the initiation of patient conditioning. The NMDP now requires that grafts be delivered and cryopreserved at the transplantation center before the initiation of a transplantation conditioning regimen for any patient scheduled for unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in the absence of unique considerations [2]. Many transplantation centers also have instituted a similar practice for related donor HCT, given that related donors face many of the same issues as unrelated donors.

The use of cryopreserved grafts provides increased flexibility and has been sporadic over the last several decades, although to our knowledge the practice has been ad hoc [3]. Several reports have examined the effect of transplantation of cryopreserved grafts for hematologic malignancies, including a study published very recently by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), in response to the need for information during the COVID-19 pandemic; none showed a difference in survival 4, 5, 6, 7. To our knowledge, there are no reports of outcomes after transplantation of cryopreserved related or unrelated donor grafts for nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Thus, the current analysis was undertaken to inform clinical practice for transplantation for severe aplastic anemia, a common nonmalignant indication for HCT.

METHODS

Patients

Patients with severe aplastic anemia who underwent HCT between 2013 and 2019 in the United States were identified from the CIBMTR database. Donors included HLA-matched siblings, haploidentical relatives, and HLA-matched and HLA-mismatched unrelated adults who donated bone marrow or peripheral blood. Recipients of cord blood transplants were excluded, because all cord blood units are cryopreserved. The patients were followed longitudinally until death or loss to follow-up. Patients or their legal guardians provided written informed consent for the study. The NMDP's Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Endpoints

The primary outcome was 1-year survival. Death from any cause was considered an event, and surviving patients were censored at 1 year or earlier for follow-up of <1 year. Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥.5 × 109 /L, and platelet recovery was defined as a platelet count ≥20 × 109/L without transfusion for 7 days. Graft failure was defined as failure to achieve ANC ≥.5 × 109/L or a decline in ANC to <.5 × 109/L without recovery after having achieved an ANC ≥.5 × 109/L, or myeloid donor chimerism (<5%), or second HCT [8]. Other outcomes studied were grade II-IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and chronic GVHD, graded using standard criteria [9,10].

Statistical Analysis

Fifty-two patients (cases) who underwent transplantation with a cryopreserved graft were matched on age (≤17, 18 to 39, and ≥40 years) [11,12], donor type (HLA-matched sibling, haploidentical relative, and HLA-matched or HLA-mismatched unrelated donor) [12,13], and graft type (bone marrow or peripheral blood) [14,15] to 195 controls identified from a pool of 979 patients who underwent HCT during the same period with a noncryopreserved graft. Forty-five cases were matched to 4 controls, 2 cases were matched to 3 controls, 4 cases were matched to 2 controls, and 1 case was matched to 1 control.

To study the effect of cryopreserved grafts compared with noncryopreserved grafts, (matched-pair) marginal Cox regression models were built and adjusted for sex, cytomegalovirus serostatus, performance score, comorbidity score, and donor-recipient ABO blood group match [16]. All variables met the assumptions for proportional hazards. Results are expressed as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Adjusted probabilities for outcomes of interest were generated from the marginal Cox model [17,18]. The level of significance was set at P ≤ .01 (2-sided), in consideration of the multiple comparisons. Analyses were done using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients and Transplantation Characteristics

The characteristics of the treatment groups matched for age, donor type, and graft type are shown in Table 1 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Females were more likely to receive cryopreserved grafts, but other characteristics, such as recipient cytomegalovirus serostatus, performance score, comorbidity index, donor-recipient ABO blood group match, transplantation conditioning regimen, and GVHD prophylaxis were similar in the 2 treatment groups. Although the total nucleated cell (TNC) doses of harvested bone marrow were similar in the 2 groups, the TNC dose infused differed, with recipients of cryopreserved bone marrow grafts receiving significantly lower cell doses (Table 1). The difference between cell dose at harvest and infusion was statistically significant (P = .0008; paired t test). CD34 doses for peripheral blood grafts were not significantly different between cryopreserved and noncryopreserved grafts (Table 1). The median duration of follow-up of surviving cases and controls was 35 months (range 6 to 74 months) and 26 months (range, 5 to 76 months), respectively.

Table 1.

Patient and Transplantation Characteristics

| Characteristic | Controls (Noncryopreserved Graft) | Cases (Cryopreserved Graft) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 195 | 52 | |

| Age, yr, median (range) | 22 (4-67) | 21 (5-64) | .96 |

| Age 1-17 yr, n (%) | 77 (40) | 21 (40) | .95 |

| Age 18-39 yr, n (%) | 72 (37) | 18 (35) | |

| Age ≥40 yr, n (%) | 46 (23) | 13 (25) | |

| Sex, male/female, n (%) | 115 (59)/80 (41) | 22 (42)/30 (58) | .03 |

| Performance score, n (%) | .72 | ||

| 90-100 | 128 (66) | 31 (60) | |

| ≤80 | 61 (31) | 19 (37) | |

| Not reported | 6 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Comorbidity score, n (%) | .55 | ||

| ≤2 | 136 (70) | 34 (65) | |

| ≥3 | 59 (30) | 18 (35) | |

| Cytomegalovirus serostatus, n (%) | .13 | ||

| Negative | 58 (30) | 10 (19) | |

| Positive | 137 (70) | 42 (81) | |

| Donor type, n (%)* | .97 | ||

| HLA-matched sibling | 79 (41) | 21 (41) | |

| HLA-haploidentical | 25 (13) | 8 (15) | |

| HLA-matched unrelated | 64 (33) | 16 (31) | |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated | 27 (14) | 7 (14) | |

| Donor-recipient ABO match, n (%) | .86 | ||

| Matched | 63 (32) | 19 (37) | |

| Minor mismatch | 22 (11) | 6 (11) | |

| Major mismatch | 31 (16) | 6 (11) | |

| Not reported | 79 (41) | 21 (41) | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%)† | .15 | ||

| Cy + ATG | 59 (30) | 11 (21) | |

| Flu + Cy + ATG | 18 (9) | 6 (12) | |

| Bu/Cy ± ATG | 4 (2) | 3 (6) | |

| Flu + TBI (200 cGy) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Cy + ATG + TBI (200 cGy) | 38 (19) | 8 (15) | |

| Cy + ATG + TBI (1000 cGy) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Flu + Cy + ATG + TBI (200 cGy) | 55 (28) | 13 (25) | |

| Flu + Bu ± ATG | 8 (4) | 5 (9) | |

| Flu + melphalan + thiotepa + ATG | 2 (1) | 2 (4) | |

| Flu + melphalan | 10 (5) | 2 (4) | |

| Graft type, n (%) | .56 | ||

| Bone marrow | 132 (68) | 33 (64) | |

| Peripheral blood | 63 (32) | 19 (36) | |

| Bone marrow TNC dose (× 108/kg), median (IQR) | |||

| Pre-cryopreservation | Not applicable | 3.83 (2.70-5.07) (n = 19 of 33) | |

| Infusion | 3.40 (2.45-4.57) (n = 109 of 132) | 2.63 (1.49-3.05) (n = 23 of 33) | .004 |

| Peripheral blood CD34+ cell dose (× 106/kg), median (IQR) | |||

| Pre-cryopreservation | Not applicable | 7.90 (7.14-8.74) (n = 15 of 19) | |

| Infusion | 6.63 (4.78-10.97) (n = 62 of 63) | 5.38 (3.78-10.97) (n = 15 of 19) | .45 |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | .07 | ||

| Ex vivo T cell depletion or CD34+ | 18 (9) | 4 (7) | |

| Post-transplantation Cy + other | 22 (11) | 6 (12) | |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + MMF | 21 (11) | 14 (27) | |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + MTX | 110 (56) | 25 (48) | |

| Calcineurin inhibitor + other | 21 (11) | 2 (4) | |

| Other agents | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Interval from diagnosis to HCT, n (%) | .28 | ||

| ≤3 mo‡ | 44 (22) | 8 (15) | |

| 3-6 mo§ | 41 (21) | 15 (29) | |

| 7-12 mo║ | 42 (22) | 15 (29) | |

| >12 mo¶ | 68 (35) | 14 (27) | |

| Transplantation period, n (%) | .16 | ||

| 2013-2015 | 103 (53) | 20 (39) | |

| 2016-2019 | 92 (47) | 32 (61) |

Cy indicates cyclophosphamide; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; Flu, fludarabine; TBI, total body irradiation ; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate.

*Donor age, yr, median (range):

haploidentical: controls, 32 (10-65); cases, 36 (14-65); unrelated: controls, 27 (18-59); cases, 30 (19-43).

†Cyclophosphamide dosing:

Cy + ATG:

cases, 200 mg/kg (n = 11); controls, 200 mg/kg (n = 56), 120 mg/kg (n = 3);

Flu + Cy + ATG:

cases, 120 mg/kg (n = 5), 60 mg/kg (n = 1); controls, 120 mg/kg (n = 15), 60 mg/kg (n = 3);

Bu + Cy:

cases, 200 mg/kg (n = 1), 120 mg/kg (n = 2); controls, 200 mg/kg (n = 2), 120 mg/kg (n = 2);

Cy + ATG + TBI (200 cGy):

cases, 200 mg/kg (n = 6), 29 mg/kg (n = 2); controls, 200 mg/kg (n = 22), 120 mg/kg (n = 1), 100 mg/kg (n = 4), 50 mg/kg (n = 2), 29 mg/kg (n = 8), unknown (n = 1);

Cy + ATG + TBI (1000 cGy):

cases, 120 mg/kg (n = 1); Flu + Cy + ATG + TBI (200 cGy): cases, 100 mg/kg (n = 4), 50 mg/kg (n = 4), 29 mg/kg (n = 5); controls, 100 mg/kg (n = 19), 50 mg/kg (n = 15), 29 mg/kg (n = 19). Interval between diagnosis and HCT:

‡77% HLA-matched sibling transplant; 23% HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donor transplant.

§55% HLA-matched sibling transplant; 30% HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donor transplant; 14% HLA-haploidentical transplant.

║23% HLA-matched sibling transplant; 59% were HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donor transplant; 19% HLA-haploidentical transplant.

¶20% HLA-matched sibling transplant; 63% HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donor transplant; 17% HLA-haploidentical transplant.

Hematopoietic Recovery

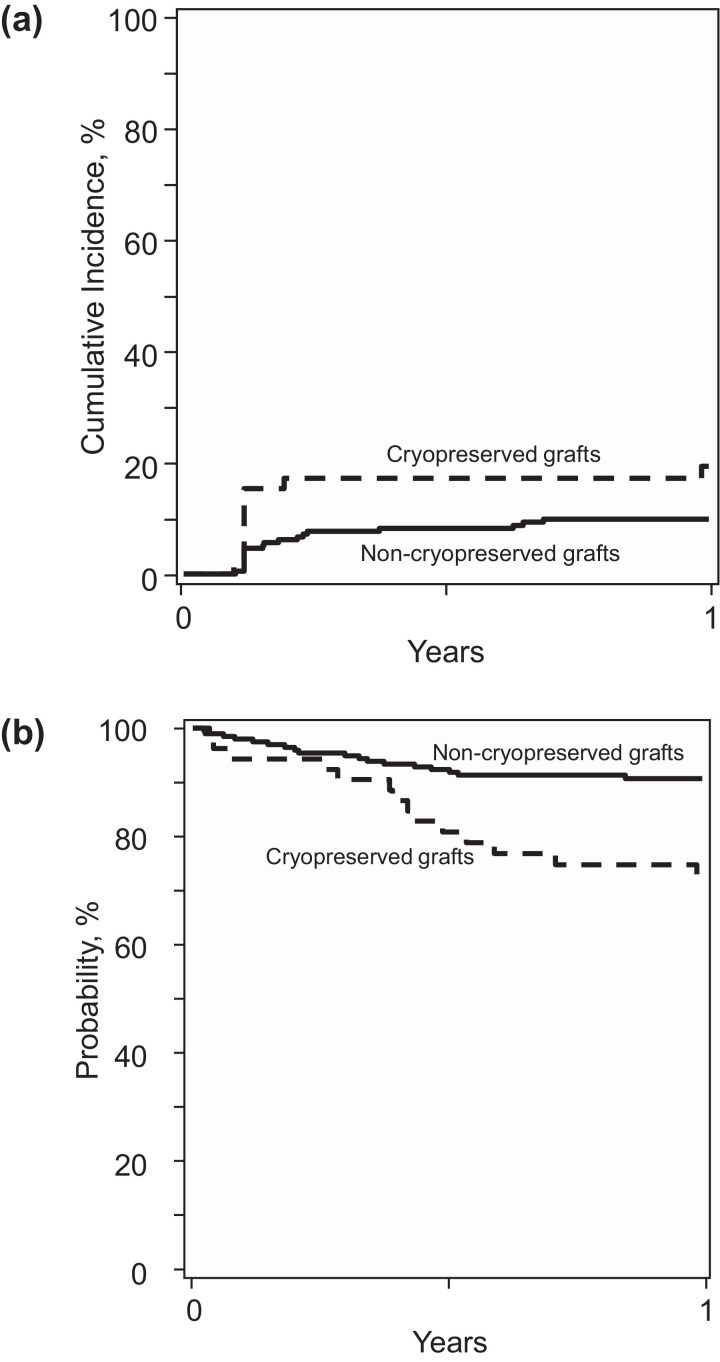

We did not record a statistically significant difference in day +28 neutrophil recovery between the cryopreserved and noncryopreserved groups (83% [95% CI, 71% to 92%] versus 91% [95% CI, 86% to 94%]; P = .17). The corresponding incidences of day +100 platelet recovery were 91% (95% CI, 79% to 98%) and 90% (95% CI, 86% to 94%) (P = .89). In multivariate analysis, the rates of neutrophil recovery (HR, .76; 95% CI, .54 to 1.08; P = .13) and platelet recovery (HR, .77; 95% CI, .57 to 1.04; P = .08) were lower in the cryopreserved group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. However, the risk of 1-year graft failure was significantly higher in the cryopreserved group (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.17 to 4.35; P = .01) (Figure 1 A). Graft failure was primary for 7 patients in the cryopreserved group and for 8 patients in the noncryopreserved group. Three patients in the cryopreserved group and 11 patients in the noncryopreserved group developed secondary graft failure. The likelihood of hematopoietic recovery and risk for graft failure were adjusted for sex, recipient cytomegalovirus serostatus, performance score, comorbidity index, and blood group ABO match.

Figure 1.

Graft failure and overall survival. (A) The 1-year graft failure was 19% (95% CI, 10% to 31%) in the cryopreserved group and 10% (95% CI, 6% to 14%) in the noncryopreserved group. (B) The 1-year overall survival was 73% (95% CI, 60% to 84%) in the cryopreserved group and 91% (95% CI, 86% to 94%) in the noncryopreserved group.

Acute and Chronic GVHD

We did not observe any significant between-group differences in grade II-IV acute GVHD (HR, .93; 95% CI, .41 to 2.13; P = .87) or chronic GVHD (HR, .79; 95% CI, .41 to 1.50; P = .46). The day +100 incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD after transplantation was 12% (95% CI, 5% to 22%) in the cryopreserved group and 13% (95% CI, 8% to 18%) in the noncryopreserved group (P = .94). The corresponding incidences of 1-year chronic GVHD were 23% (95% CI, 12% to 37%) and 28% (95% CI, 21% to 35%), respectively (P = .49).

Overall Survival

One-year mortality was higher in the cryopreserved group compared with the noncryopreserved group (HR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.60 to 6.11; P = .0008), after adjusting for sex, recipient cytomegalovirus serostatus, performance score, comorbidity index, and blood group ABO match. The adjusted 1-year probability of overall survival was 73% (95% CI, 60% to 84%) in the cryopreserved group and 91% (95% CI, 86% to 94%) in the noncryopreserved group (Figure 1B). We also evaluated mortality risks without censoring at 1-year post-transplantation and observed similar HRs of mortality after transplantation of cryopreserved products. A subset analysis limited to 19 cryopreserved peripheral blood transplant recipients and 63 controls also showed a higher rate of graft failure (HR, 2.98, 95% CI, .92 to 9.64; P = .06) and higher mortality (HR, 3.84; 95% CI, 1.44 to 10.21; P = .007) with cryopreservation. Seventeen patients (17 of 52; 33%) died after transplantation of cryopreserved grafts. Primary disease was reported as the predominant cause of death (13 of 17; 76%); other causes of death included GVHD (n = 2), infection (n = 1), and hemorrhage (n = 1). Thirty-three patients (33 of 194; 17%) died after transplantation of noncryopreserved grafts. Primary disease was also reported as the predominant cause of death in this group (24 of 33; 73%); other causes of death included infection (n = 3), interstitial pneumonitis (n = 2), organ failure (n = 2), and hemorrhage (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

The present analysis was undertaken to examine whether there are differences in survival or other transplantation outcomes after transplantation of cryopreserved bone marrow or peripheral blood for severe aplastic anemia. Recipients of cryopreserved grafts were matched to recipients of noncryopreserved grafts for age at transplantation, donor type/donor-recipient HLA match, and graft type, factors that are consistently associated with outcomes of HCT for this disease 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. The analyses also considered the effect of other potential risk factors on transplantation outcomes. After carefully controlled analyses, we observed higher graft failure and mortality rates after transplantation of cryopreserved grafts compared with noncryopreserved grafts. Thus, our findings favor the transplantation of noncryopreserved grafts for severe aplastic anemia.

Transplantation conditioning regimens for patients with severe aplastic anemia vary by the type of donor [19]. Other reports have shown an effect of conditioning regimen for survival after HLA-matched sibling transplants [19]. None of the patients in the present analysis received cyclophosphamide alone or with fludarabine—conditioning regimens associated with higher graft failure and mortality rates [19]. The cell dose of the graft also has been associated with graft failure; it is recommended that bone marrow grafts contain a minimum of 3 × 108/kg TNCs to avoid graft failure [20]. These data are derived from an analysis of noncryopreserved bone marrow grafts. Data on infused bone marrow TNC dose were available for only 70% (23 of 33) of cryopreserved grafts and 83% (109 of 132) of noncryopreserved grafts. Despite this limitation, we found significantly lower TNC doses infused in the cryopreservation group. Although 68% of patients receiving cryopreserved bone marrow grafts had ≥3 × 108/kg TNCs harvested, only 26% had that amount infused. This loss of cells might have led to the observed differences in outcomes between the 2 treatment groups.

The difference between TNC dose at harvest and at infusion implies that the cryopreservation/thawing process is associated with cell loss. However, other unmeasured or unknown factors also might have influenced the observed differences in outcome. We do not have data on cell function at any time point. An earlier report on the functional assay of cryopreserved bone marrow suggests preservation of cell function, although that report included only 7 grafts [21]. An analysis of noncryopreserved bone marrow cellular subsets for unrelated donor transplantations failed to show an effect of graft composition on hematopoietic recovery or survival; however, that study included only 7 patients with aplastic anemia [22].

All cryopreserved peripheral blood grafts in the current analysis contained a CD34+ dose >2 × 106/kg, the recommended minimum dose for severe aplastic anemia [23]. A subset analysis limited to recipients of peripheral blood grafts was consistent with the findings of the main analysis. Cryopreserved CD34+ cells from peripheral blood have been shown to have a significant loss of membrane integrity, viability, and CFU potential [23], which collectively could have contributes to the adverse effects of transplantation of cryopreserved peripheral blood seen in our study.

We hypothesize that several factors led to the poor outcomes seen after transplantation of cryopreserved grafts. Optimizing the cell dose is desirable, but a controlled study that examines for changes in graft composition with cryopreservation/thaw that is specific for aplastic anemia is needed. A detailed analysis of the composition and function of cryopreserved grafts is beyond the scope of this study. We did not observe any statistically significant differences in neutrophil and platelet recovery despite lower rates of recovery after transplantation of cryopreserved grafts. We hypothesize that the absence of significant differences is attributed to the modest number of patients in our study cohort. We do not know the indications for the use of cryopreserved grafts in the patients included in this analysis. The interval between diagnosis and HCT was not different between the 2 treatment groups. Furthermore, the timing of transplantation by donor type is also consistent with accepted clinical practice guidelines. HLA-matched sibling transplants were mostly offered within 6 months of diagnosis, and alternative donor transplants were offered later after failure of at least 1 course of immunosuppressive therapy [24]. Recipients of cryopreserved and noncryopreserved grafts were matched for graft type (bone marrow or peripheral blood). Subset analyses limited to peripheral blood transplants confirmed higher graft failure and mortality, consistent with the main analysis, and suggest a greater effect than seen with bone marrow grafts.

These findings differ from findings in previous studies of patients receiving cryopreserved grafts for hematologic malignancies. Compared with patients with aplastic anemia, patients with malignancy often come to HCT after multiple chemotherapy and immune-suppressive therapies and also usually receive more intensive pretransplantation conditioning. For these reasons, and perhaps because of differences in the nature of the underlying diseases, the risk of graft failure is generally lower after HCT for malignant disease compared with after HCT for aplastic anemia and may be less affected by any alterations in cell dose or function induced by cryopreservation.

In summary, the data presented herein support the use of noncryopreserved bone marrow or peripheral blood for HCT in patients with severe aplastic anemia. If this is not possible, it may be prudent to delay transplantation until it is. These transplantations are often not deemed urgent, and every effort must be made to provide the best available supportive care for the patient until the transplantation center can ensure the availability of a noncryopreserved graft. If a delay is not possible, careful assessment of the risk of using a cryopreserved graft versus the risk of not undergoing indicated HCT is necessary. The NMDP/Be The Match considers the diagnosis of aplastic anemia a valid reason to try to deliver fresh grafts for unrelated donor transplantation in patients with severe aplastic anemia.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Contract HHSH250201200016C with the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and Grants N00014-15-1-0848 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, HRSA, or any other agency of the US Government.

Conflict of interest statement: M.H. has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, and Astellas Pharma; has served as a consultant for Incyte, ADC Therapeutics, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Magenta Therapeutics, Omeros, AbGenomics, Verastem, and TeneoBio; and has served on the speakers bureau for Sanofi Genzyme and AstraZeneca. A.D. has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Sanofi Genzyme, AstraZeneca, TeneoBio, Prothena, EDO, and Mundipharma and has received consulting fees from Prothena, Pfizer, Akcea, Imbrium, and Janssen. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: See Acknowledgments on page e165.

References

- 1.American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. ASTCT resources for COVID-19. Available at: https://www.astct.org/communities/public-home?CommunityKey=d3949d84-3440-45f4-8142-90ea05adb0e5. Accessed April, 2020.

- 2.National Marrow Donor Program (Be The Match). Response to COVID-19. Available at: https://network.bethematchclinical.org/news/nmdp/be-the-match-response-to-covid-19/. Accessed April, 2020.

- 3.Frey NV, Lazarus HM, Goldstein SC. Has allogeneic stem cell cryopreservation been given the 'cold shoulder'? An analysis of the pros and cons of using frozen versus fresh stem cell products in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:399–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockschläder M, Hassan HT, Krog C, et al. Long-term follow-up of leukaemia patients after related cryopreserved allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:382–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Jamal N, Saragosa R, et al. Similar outcomes of cryopreserved allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplants (PBSCT) compared to fresh allografts. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medd P, Nagra S, Hollyman D, Craddock C, Malladi R. Cryopreservation of allogeneic PBSC from related and unrelated donors is associated with delayed platelet engraftment but has no impact on survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:243–248. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamadani M, Zhang MJ, Tang XY, et al. Graft cryopreservation does not impact overall survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using post-transplant cyclophosphamide for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsson R, Remberger M, Schaffer M, et al. Graft failure in the modern era of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:537–543. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson K, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Lee MB, Rimm AA, Bortin MM. Consensus among bone marrow transplanters for diagnosis, grading and treatment of chronic graft versus host disease. Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1989;4:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta V, Eapen M, Brazauskas R, et al. Impact of age on outcomes after bone marrow transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia using HLA-matched sibling donors. Haematologica. 2010;95:2119–2125. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.026682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacigalupo A. How I treat acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2017;129:1428–1436. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-693481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horan J, Wang T, Haagenson M, et al. Evaluation of HLA matching in unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for nonmalignant disorders. Blood. 2012;120:2918–2924. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-417758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrezenmeier H, Passweg JR, Marsh JC,, et al. Worse outcome and more chronic GVHD with peripheral blood progenitor cells than bone marrow in HLA-matched sibling donor transplants for young patients with severe acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2007;110:1397–1400. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eapen M, Le Rademacher J, Antin JH,, et al. Effect of stem cell source on outcomes after unrelated donor transplantation in severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118:2618–2621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Loberiza FR, Klein JP, Zhang MJ. A SAS macro for estimation of direct adjusted survival curves based on a stratified Cox regression model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;88:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Zhang MJ. SAS macros for estimation of direct adjusted cumulative incidence curves under proportional subdistribution hazards models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2011;101:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bejanyan N, Kim S, Hebert KM, et al. Choice of conditioning regimens for bone marrow transplantation in severe aplastic anemia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3123-3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Marsh JC, Ball SE, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:43–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam MS, Anoop P, Datta-Nemdharry P,, et al. Implications of CD34+ cell dose on clinical and hematological outcome of allo-SCT for acquired aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:886–894. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins NH, Gee AP, Durett AG, et al. Effect of the composition of unrelated donor bone marrow and peripheral blood progenitor cell grafts on transplantation outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lioznov M, Dellbrügger C, Sputtek A. Transportation and cryopreservation may impact hematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment of allogeneic PBSCs, but not BM. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:121–128. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young NS. Aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1643–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1413485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]