Abstract

Background

Pandemics and epidemics are public health emergencies that can result in substantial deaths and socio-economic disruption. Nurses play a key role in the public health response to such crises, delivering direct patient care and reducing the risk of exposure to the infectious disease. The experience of providing nursing care in this context has the potential to have significant short and long term consequences for individual nurses, society and the nursing profession.

Objectives

To synthesize and present the best available evidence on the experiences of nurses working in acute hospital settings during a pandemic.

Design

This review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for systematic reviews.

Data sources

A structured search using CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, MedNar, ProQuest and Index to Theses was conducted.

Review methods

All studies describing nurses’ experiences were included regardless of methodology. Themes and narrative statements were extracted from included papers using the SUMARI data extraction tool from Joanna Briggs Institute.

Results

Thirteen qualitative studies were included in the review. The experiences of 348 nurses generated a total of 116 findings, which formed seven categories based on similarity of meaning. Three synthesized findings were generated from the categories: (i) Supportive nursing teams providing quality care; (ii) Acknowledging the physical and emotional impact; and (iii) Responsiveness of systematised organizational reaction.

Conclusions

Nurses are pivotal to the health care response to infectious disease pandemics and epidemics. This systematic review emphasises that nurses’ require Governments, policy makers and nursing groups to actively engage in supporting nurses, both during and following a pandemic or epidemic. Without this, nurses are likely to experience substantial psychological issues that can lead to burnout and loss from the nursing workforce.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Nurses experiences, Qualitative systematic review, Emerging infectious diseases, Epidemics

What is already known about the topic?

-

•

Respiratory infectious pandemics and epidemics are particularly virulent given their spread via droplets and interpersonal contact.

-

•

During pandemics and epidemics nurses may be caring for critically ill and infectious patients, yet there appears to be no systematic review that explores the nurses’ experience of working during these challenging times.

-

•

Nurses’ have been reported to experience stress and anxiety during a pandemic.

What this paper adds

-

•

Nurses’ sense of duty, dedication to patient care, personal sacrifice and professional collegiality is heightened during a pandemic or an epidemic.

-

•

Concerns for personal and family safety, and fear and vulnerability issues remain paramount.

-

•

Nurses are willing to accept the risks of their occupation in the pandemic situation.

-

•

The significant impact of nurses’ experiences highlights a need for strategies around self-care and ongoing support to ensure the health of nurses is maintained.

1. Introduction

Pandemics are simultaneous global transmission of emerging and re-emerging infectious disease epidemics affecting large amounts of people, often resulting in substantial deaths and social and economic disruption (Madhav et al., 2017). In recent years growing outbreaks of infectious disease, such Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 (Maunder, 2004), novel influenza A / H1N1 (swine flu) in 2009 (Fitzgerald, 2009) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012 (Kim, 2018), have suggested a potential global pandemic (Seale et al., 2009). The discovery of novel coronavirus Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China in December 2019 brought this potential to realization (Huang and rong Liu, 2020).

Pandemics have enormous implications on health care systems, particularly on the workforce (Ives et al., 2009, Seale et al., 2009). Respiratory infectious pandemics and epidemics are particularly virulent given their spread via droplets and interpersonal contact (Koh et al., 2012). Nurses, as the largest group of health professionals (World Health Organization, 2020) are at the frontline of the health care system response to both epidemics and pandemics. Nurses deliver care directly to patients in close physical proximity and as such, are often directly exposed to these viruses and are at high risk of developing disease (Hope et al., 2011, Seale et al., 2009). In the SARS outbreak in Taiwan, some 4 of the 70 deaths were nurses (Chiang et al., 2007). Early reports related to COVID-19 indicate that the rate of infection among health care professionals with this virus may be even more extensive (Huang and rong Liu, 2020).

Despite having a professional obligation to care for the community during a pandemic or epidemic, many nurses have concerns about their work and its impact on them personally. In particular, the risk of being infected, transmission to family members, stigma about the vulnerabilities of their job and restrictions on personal freedom have been reported as key concerns (Chiang et al., 2007, Hope et al., 2011, Koh et al., 2012, Seale et al., 2009). Complicating the situation for nurses during pandemics are the logistical issues related to supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), and shortages of other necessary resources to support service delivery (Xie et al., 2020). The notion of perceived risk to health professionals during pandemics has been explored in the literature (Koh et al., 2011), although there are fewer studies reporting data about nurses, as distinct from other health professionals, and their experiences of involvement in a pandemic.

While the literature identifies that many health care professionals are willing to accept the risks of their occupation in a pandemic situation, others perceive the risks of their work are too high (Koh et al., 2012). In particular, nurses, females and younger health care workers have been identified as being less likely than doctors, male health care workers and older individuals to accept the occupational risks (Imai et al., 2005, Koh et al., 2005, Koh et al., 2012). As nurses perceive personal risks as being too high, some decide to leave their jobs (Chiang et al., 2007, Martin et al., 2013, Shiao et al., 2007). This has significant implications for the workforce and ability of health systems to deliver care at a time of heightened need. Understanding the factors that impact nurses’ decisions to stay or leave the workforce are essential to inform future workforce policy and institutional responses and requires further investigation.

For those nurses who remain in clinical practice, an obvious impact relates to the psychosocial ramifications. Nurses’ have been reported to experience stress associated with separation from family, sleep deprivation and heavy workloads created by health system demand and staff shortages (Huang and rong Liu, 2020). Additionally, the ethical and resource issues that emerge during a pandemic or epidemic can have negative psychological impacts (Johnstone and Turale, 2014, Seale et al., 2009). Being involved in setting up specialised pandemic clinics, staging facility operations or being seconded to areas outside their usual scope of practice can also be stressful (Seale et al., 2009). Psychological impacts are likely to have both short and long term consequences for individual nurses. Understanding the experiences of nurses can assist in identifying particular stressors and helpful coping strategies to inform support services.

To date, there is limited research about nurses’ experiences of a pandemic or epidemic, particularly as distinct from other health professionals (Corley et al., 2010, Koh et al., 2012, Lam and Hung, 2013). However, understanding the experiences and impacts of pandemics and epidemics on nurses is vital to ensure that these essential workers are well supported to remain in the workforce and facilitated to provide high quality health care during this time of elevated health need in the community.

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports was conducted to identify qualitative reviews on nurses’ experiences during a pandemic. The search did not reveal any systematic review addressing the current review question or inclusion criteria. Therefore this review has been conducted to synthesize and present current evidence around nurses’ managing and caring for patients during pandemics. This review will inform the current response to COVID-19 and future pandemic response.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A systematic review was undertaken to synthesize evidence of the experiences of nurses’ during a pandemic or an epidemic. The review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines (Aromataris and Munn, 2017). The PRISMA systematic review reporting checklist (Moher, 2009) was used as a basis for reporting the review.

2.2. Search methods

Using a structured search strategy, the electronic databases CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, MedNar, ProQuest and Index to Theses were searched in March 2020. Keywords used in the search were: (Nurs* OR Nursing staff OR Health professional* OR health care worker* OR Health Personnel AND attitude* OR perception* OR experience* OR perspective* OR feeling* OR thought* OR opinion* OR belief* OR knowledge OR view* AND pandemic* OR pandemic outbreak OR disease outbreaks OR Influenza A OR H1N1 OR Coronavirus Infections OR Pandemic influenza OR SARS OR SARS virus OR Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome OR Pandemic response OR COVID-19 OR Coronavirus OR MERS OR Middle East Respiratory Syndrome OR Avian Influenza OR H5N1 OR Epidemic*). The final search strategy for MEDLINE can be found in the supplementary material.

The search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished qualitative studies, with no time limitations, in the English language only. Studies were included if they reported the experiences of nurses working in an acute care hospital during a pandemic or epidemic. A pandemic or epidemic was classified using the WHO definition and declaration and included SARS, MERS, Avian influenza (H5N1) and swine flu (H1N1). Studies that investigated nurses working in community settings during a pandemic were excluded. Studies exploring nurses’ experiences working during Ebola outbreaks were also excluded as Ebola is not a viral respiratory pandemic or epidemic and has a different mode of transmission. Hand-searching of the reference lists of studies assessed for eligibility was also undertaken.

2.3. Search outcomes

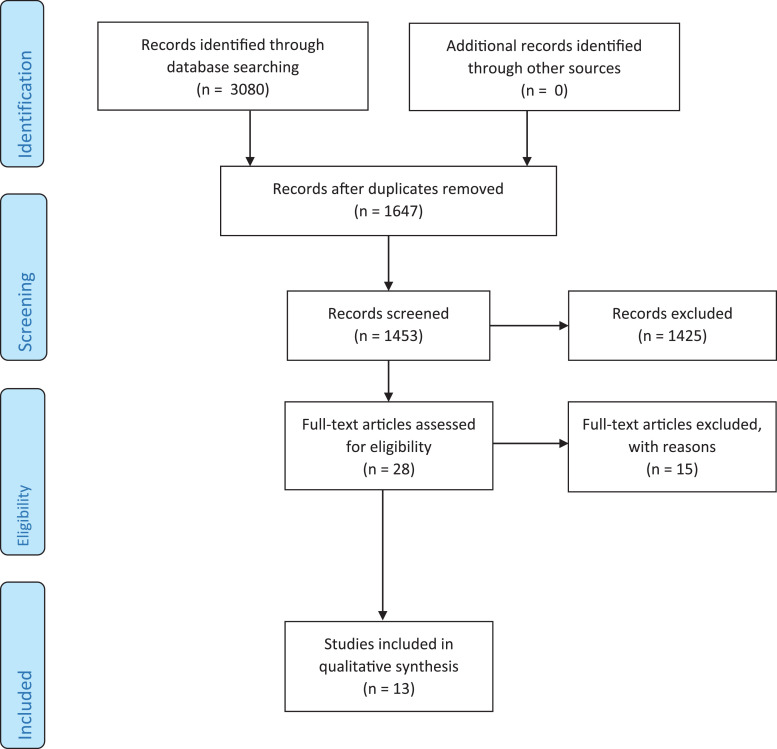

The searches yielded a total of 3080 citations, of which, 1647 were duplicates (Fig. 1 ). The remaining 1453 citations were screened for relevance using the title and abstract and 28 were retrieved for potential inclusion. The references of these papers were scrutinized, however no new papers were identified. Fifteen of the 28 papers did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included: 1) Conducted on all health care workers with no separate data for nurses 2) Paper was not in English language 3) No qualitative data was available 4) Was only conducted on nursing leaders/management rather than frontline nurses (A full list of reasons is included in the supplementary material). A total of 13 papers were appraised and included in the final review. Despite searching for papers on avian influenza, no suitable papers were found for this infectious disease.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

2.4. Quality appraisal

Using the JBI critical appraisal tool, each study was appraised for methodological quality by two independent reviewers (RM and IA) and checked by a third reviewer (HL or RF). Each criterion was allocated a score (Yes = 2, No = 0, Unclear = 1), giving a total score of 20 for each paper. These scores were then converted to a percentage. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or via a third reviewer. As all studies scored at least 70%, none were excluded based on methodological quality. No studies described the influence of the researcher on the research, and only three studies provided a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Liu and Liehr, 2009, Kim, 2018). Additionally, Shih et al. (2007) did not demonstrate congruence between the methodology and interpretation of results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Critical Appraisal.

| Citation | Criterion |

Results (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Chiang et al. (2007) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| Chung et al. (2005) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| Corley et al. (2010) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | Y | Y | 15/20 (75%) |

| Holroyd and McNaught (2008) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 18/20 (90%) |

| Ives et al. (2009) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| Koh et al. (2012) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| Lam and Hung (2013) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| Liu and Liehr (2009) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 18/20 (90%) |

| Shih et al. (2007) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 14/20 (70%) |

| Wong et al. (2012) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 16/20 (80%) |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 90.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 90.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

Y = yes; N = no; U = unclear

1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? 2 .Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? 3 .Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

2.5. Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from included papers using the standardized data extraction tool from JBI SUMARI. The data extracted included geographical location, setting, number of participants, participant demographics (e.g. age, sex, and years of experience), method of data collection and study findings. Some studies included data for other health professionals, however only data for nurses was extracted.

The relevant qualitative findings from the included studies were extracted verbatim with the inclusion of a participant quote to support and illustrate the meaning of the finding. The qualitative findings were rated according to JBI Levels of Credibility (Munn et al., 2014), as unequivocal, credible or unsupported. Findings were pooled using the meta-aggregation method. This process involved assembling the findings at the subtheme level from individual studies, followed by categorizing the findings on the basis of similarity in meaning. Based on these a single comprehensive set of synthesized findings were developed that could be used as a basis for clinical practice.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

Narratives from 13 qualitative studies involving 348 nurses were included in the review (Table 2 ). Studies were published between 2005 (Chung et al., 2005) and 2020 (Lam et al., 2020) and the study design was mainly phenomenological. Most of the nurses were female, and aged between 20 and 50 years. Years of experience ranged from three months (Kang et al., 2018) to 43 years (Koh et al., 2012). Studies were conducted in Hong Kong (Chung et al., 2005, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Lam et al., 2020, Lam and Hung, 2013, Wong et al., 2012), Taiwan (Chiang et al., 2007, Shih et al., 2007), South Korea (Kang et al., 2018, Kim, 2018), China (Liu and Liehr, 2009); Australia (Corley et al., 2010); UK (Ives et al., 2009), and Singapore (Koh et al., 2012). The studies were conducted in various hospital settings, and critical care departments (including emergency departments).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Citation | Country | No. of Participants | Age (years) | Clinical experience (years) | Females | Study design | Data collection and analysis | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiang et al. (2007) | Taiwan | 21 | 21 -43 | 0.5-18 | 21 (100%) | Phenomenology | Focus groups Thematic analysis | The themes identified were: self-preservation; self-mirroring; and self-transcendence. |

| Chung et al. (2005) | Hong Kong | 8 | 21-40 | 0.5-14 | 4 (50%) | Phenomenology | Face-to-face interviews Thematic analysis | The three major themes explicated were: the various emotions experienced in caring for SARS patients, the concept of uncertainty and revisiting the ‘taken for granted’ features of nursing. |

| Corley et al. (2010) | Australia | 8 | NC | NC | NR | Phenomenology | Open ended questionnaire and focus groups. | Eight common themes emerged: the wearing of personal protective equipment; infection control procedures; the fear of contracting and transmitting the disease; adequate staffing levels within the intensive care unit; new roles for staff; morale levels; education regarding extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and the challenges of patient care |

| Holroyd and McNaught (2008) | Hong Kong | 7 | NR | 4-12 | 7 (100%) | Qualitative | Personal reflective essays – content analysis | Six themes emerged: The suddenness of SARS; |

| Impacts on professional nursing practice; Personal impacts; Community and families; Community and cultural responses; and Being prepared. | ||||||||

| Ives et al. (2009) | United Kingdom | 12 | NC | NC | NC | Qualitative | Focus groups and interviews | The major themes interact in one of four ways: (1) Impacting upon (a change in one may cause a change in the other); (2) Motivation (3) Association; (4) Solution. Eight main themes emerged under the ‘duty to work' and 'barriers to working' issues. |

| Koh et al. (2012) | Singapore | 10 | NR | 7-43 | NR | Qualitative | Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews | Three themes emerged: living with risk; the experience of SARS; and acceptance of risk. |

| Thematic analysis | ||||||||

| Lam and Hung (2013) | Hong Kong | 10 | 20 - > 40 | 1->15 | 10 (100%) | Qualitative | Interviews Content analysis | The three following categories emerged from the interview data: concerns about health, comments on the administration, and attitudes of professionalism. |

| Liu and Lehr (2009) | China | 6 | 24–41 | 1–21 | NR | Qualitative | Content analysis | Chinese nurses faced personal challenge, focused on the essence of care and experienced self-growth while caring for SARS patients. |

| Shih et al. (2007) | Taiwan | 200 | 20-50 | Mean 3.5 (SD 2.3) | 191 (96%) | Qualitative | Focus groups Thematic analysis | Six major types of stage-specific difficulties with and threats to the quality of care of SARS patients were identified. |

| Wong et al. (2012) | Hong Kong | 3 | 31-37 | 7-16 | 2 (66.6%) | Qualitative | Interviews Thematic analysis | Themes included: willingness to retain in the post; and Duty concerns during novel H1N1 flu pandemic. |

NR = Not reported; NC = Not calculated

The review comprised of 116 study findings –101unequivocal and 15 credible (supplementary material), which formed seven categories based on similarity in meaning. Based on these categories three synthesized findings were generated: supportive nursing teams providing quality care; acknowledging the physical and emotional impact; and responsiveness of systematised organizational reaction.

3.2. Supportive nursing teams providing quality care

Supportive nursing teams providing quality care were derived from two categories, specifically; sense of duty, dedication to patient care and personal sacrifice; and professional collegiality.

3.2.1. Sense of duty, dedication to patient care and personal sacrifice

Overall, this review found that nurses, regardless of the circumstances, felt a great sense of professional duty to work during a pandemic (Wong et al., 2012, Lam et al., 2020, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008). Working during difficult times and in dangerous situations was viewed by nurses as part of the role and their professional obligation (Lam and Hung, 2013, Kim, 2018, Chiang et al., 2007). Nurses’ eagerness to fulfil their roles during a pandemic, despite the risk of potential infection, evidences their great commitment to patient care (Kang et al., 2018, Koh et al., 2012). Nurses also immersed themselves in patient care as a way of managing their anxiety and pressures in an ever changing and dynamic environment (Liu and Liehr, 2009, Chung et al., 2005). This professional commitment, however, created an ethical and moral dilemma for nurses, with them feeling as though they had to decide between patients and their family responsibilities (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Chung et al., 2005). This personal sacrifice resulted in social isolation through separation from family and friends (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Chung et al., 2005).

3.2.2. Professional collegiality

Professional camaraderie amongst nursing colleagues working during a pandemic was high (Ives et al., 2009, Kim, 2018, Liu and Liehr, 2009). Nurses acknowledged the importance of caring for their co-workers and in sharing the load. Some nurses associated the experience with working on a battlefield, whereby they worked together as a team protecting one another (Chung et al., 2005, Kang et al., 2018, Liu and Liehr, 2009). Appreciation of their nursing colleagues was demonstrated through sharing their experiences, willingness to work together and encouraging a team spirit (Shih et al., 2007, Chung et al., 2005, Chiang et al., 2007).

3.3. Acknowledging the physical and emotional impact

Acknowledging the physical and emotional impact were derived from two categories, specifically; concerns for personal and family safety; and fear, vulnerability and psychological issues in the face of crisis.

3.3.1. Concerns for personal and family safety

Not unexpectedly, nurses experienced heightened anxiety for their own health while caring for infected patients during a pandemic (Lam and Hung, 2013, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Kang et al., 2018, Koh et al., 2012). Concerns over their own susceptibility to infection was largely associated with fear of the new phenomenon, and with the possibility of death (Chung et al., 2005, Kim, 2018, Lam and Hung, 2013). Nurses feared not only being exposed to infected patients, but were scared that infection could be spread through nursing colleagues sharing resources (Koh et al., 2012). Beside their own personal health, nurses feared that with the uncertainty of the working environment and new disease threat that they were placing their family and friends at greater risk of infection (Shih et al., 2007, Lam and Hung, 2013). Nurses were particularly concerned with spreading the infection to vulnerable family members, such as the elderly, immunocompromised and young children (Ives et al., 2009, Lam and Hung, 2013, Koh et al., 2012). Providing protection for family members was perceived as a priority, with some nurses choosing to self-isolate as a protection strategy (Lam and Hung, 2013).

3.3.2. Fear, vulnerability and psychological issues in the face of crisis

The perception of personal, social and economic consequences from the uncertainty of a pandemic led to psychological distress and fear among nurses working during a pandemic (Shih et al., 2007, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Chung et al., 2005). Nurses felt vulnerable and worried about future litigation related to the need to prioritise resources and patient needs in a time where they had to ration and deny services to some patients (Ives et al., 2009). The sense of powerlessness was overwhelming for nurses as they were under extreme pressure and often feared that their practice was being affected by work demands and community fear generated by the pandemic (Lam and Hung, 2013, Chung et al., 2005). Despite the professional camaraderie, the unfamiliarity of the pandemic environment created a sense of loneliness (Kim, 2018) and frustration among nurses. Additionally, relatives of patients were seen to be projecting their emotions towards the nurses (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Kim, 2018). Not having control over patient flow also generated both physical and psychological exhaustion (Kang et al., 2018). Deaths amongst some of their nursing colleagues as a result of the pandemic created uncertainty and heightened anxiety and stress (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Koh et al., 2012).

3.4. Responsiveness of systematized organizational reaction

Responsiveness of systematized, organizational reaction were derived from three categories, specifically; protection and safety; knowledge and communication; and organisational preparedness - provision of adequate leadership, staffing and policy.

3.4.1. Protection and Safety

The perceived lack of defensive resources, (PPE), were contributing factors to nurses concerns and fears working during pandemics (Ives et al., 2009, Kang et al., 2018, Shih et al., 2007, Corley et al., 2010). The uncertainty that the level of protection provided to nursing staff was effective and efficient to minimise infection risk affected many nurses’ ability to cope (Ives et al., 2009, Corley et al., 2010). Other nurses felt that there was conflicting advice and a lack of consensus on the appropriate infection control measures (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008). Despite low PPE supplies in some hospitals, nurses demonstrated their resilience by collaborating with colleagues to develop alternative protection, with some using disposable raincoats as PPE (Shih et al., 2007).

3.4.2. Knowledge and communication

Rapidly changing advice and knowledge about the contagion increased the stress levels among nursing staff (Ives et al., 2009, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Chung et al., 2005, Liu and Liehr, 2009). Many nurses wanted to ensure that they were equipped with the appropriate information to provide quality patient care. Yet nurses expressed inadequate training in caring for patients affected by an emerging infectious disease (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Lam et al., 2020, Liu and Liehr, 2009). Given that the infectious disease was so new, modifications of policies and guidelines were updated swiftly, which created confusion as to the most up-to-date versions (Lam and Hung, 2013, Holroyd and McNaught, 2008). This confusion also exacerbated nurses’ anxiety and perception of risk. The communication of information was often felt to be difficult and not succinct thus creating additional confusion and distress for the already busy nurses (Corley et al., 2010, Chung et al., 2005).

3.4.3. Organisational preparedness - provision of adequate leadership, staffing and policy

Occupational and organisational preparedness to deal with the pandemic impacted considerably on frontline nursing staff (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Wong et al., 2012, Shih et al., 2007, Corley et al., 2010). One of the major factors that influenced nurses’ ability to cope with the demanding workload during the pandemic were staffing shortages (Lam and Hung, 2013, Kang et al, 2018, Corley et al., 2010). A lack of staff made ensuring adequate staff skill mix for managing high acuity patients challenging, not only creating pressure on more junior staff but also the senior staff who had to support them (Corley et al., 2010). Such pressure on the nursing workforce meant nurses had to adapt to changes quickly, often in suboptimal conditions, with high patient turnover and limited isolation rooms (Holroyd and McNaught, 2008, Wong et al., 2012, Liu and Liehr, 2009). Nurses believe that one of their greatest challenges working during the pandemic was a lack of preparedness planning at both a management and health department level (Koh et al., 2012, Lam et al, 2020).

4. Discussion

This review resulted in seven categories that produced three synthesized findings: 1) Supportive nursing teams providing quality care, 2) Acknowledging the physical and emotional impact, and 3) Responsiveness of systematised organizational reaction. These findings synthesise what is known in the literature around the experiences of nurses working during a pandemic or epidemic. As such, they are important to inform support strategies to optimise the international nursing workforce both during and following the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Nurses have a high degree of inter-disciplinary collaboration (Padgett, 2013) and work in multidisciplinary teams focussed on collaborative care, which is considered an important strategy to improve patient outcomes (Oandasan, 2006). Teams of healthcare professionals have existed in hospitals for many years, with some experiencing effective collaboration and some not. Within an effective interdisciplinary approach to patient care, Petri (2010) described how collaboration can simply be defined as the act of working together, but that in order for it to be effective, it needs to occur in an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect. These are critical elements for nurses’ to feel in pandemic situations where uncertainty is high.

In this review, and within the context of a health pandemic, mutual trust and respect were identified by many nurses when they described how supportive the team were and that they felt crises engendered professional collegiality. The primary aim of collegiality according to Hansen (1995) is the advancement of some superordinate goal in order to achieve clinically integrated care. During times of crisis, like natural disasters and health epidemics, nurses work within highly interdependent but stressful healthcare environments, which appear to bring collegial relationships to the fore, perhaps to ensure that the care that is delivered is always the highest quality.

At the very core of the nursing profession, and the reason for its very existence, is the patient. This review found that nurses have a strong sense of duty toward patients. Despite nurses’ sense of fear and vulnerability, nurses’ duty to care for patients outweigh their competing obligations to their families and the risk of their own exposure (Pfrimmer, 2009). The duty referred to here isn't the legal obligation that is embedded within nurses Codes of Practice (Young, 2009), but rather, it is the deep sense of wanting to provide quality care because that is what a nurse does; it is considered the right thing to do (Smith and Godfrey, 2002). It is what Hewlett and Hewlett (2005) describe as exceptional commitment to the nursing profession in a context where the lives of health care workers are in jeopardy. The concept of doing the right thing doesn't only exist in times of crisis. Research regarding nurses doing the right thing has also occurred in studies on nursing education (Anderson et al., 2018), academic leadership (Horton-Deutsch et al., 2014), and palliative care (Smith et al., 2009).

Although nurses had a deep sense of wanting to continue to provide care as a result of their strong sense of duty and wanting to do the right thing, these virtues did not preclude them from harbouring fears and concerns about the safety of themselves and their families. Nursing practice during crisis, particularly those that place the nurse in mortal danger, meant it was important to acknowledge both the physical and emotional impacts. Fear of transmission and contagion was also a factor in this systematic review and has been reported in studies on H1N1, SARS and Ebola virus (Bukhari et al., 2016, Koh et al., 2012, Speroni et al., 2015). Importantly, even though nurses are fearful, they remain in the workplace and continue to provide care (Jones et al., 2017).

The organizational reaction was a key consideration for nurses across studies in this review. Participants looked to their respective organizations to provide them with knowledge about the pandemic that was easy to understand and delivered in a consistent way. They did not want ‘mixed messages’. Understanding the best practice in PPE use and being supplied with adequate PPE appear to be the largest issues of concern and can be seen in many studies related to pandemics and epidemics (Cohen and Casken, 2011, Huang et al., 2020, Jones et al., 2017, Michaelis et al., 2009, Speroni et al., 2015)

4.1. Study strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the review included the use of the standardised JBI critical appraisal instrument for qualitative studies to assess the methodological quality of included studies. In addition, potential bias was reduced through the involvement of more than one reviewer in the quality assessment, data extraction and data analysis. The validity of the review is augmented by the recurrence of findings between studies. The use of the meta-aggregation approach enabled the categorisation of each finding reported in the studies without seeking to re-interpret the primary author's findings. In addition this approach allows for the development of generalizable statements in the form of recommendations to guide practitioners and policy makers (Hannes & Lockwood 2011).

Despite the rigour in which this review was conducted some limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, although a comprehensive search of the databases using the best key word combinations was undertaken, publications not indexed in these data bases could have been omitted. In addition, this review only included studies published in English. Therefore, studies published in other native languages, where the SARS pandemic was widespread, could have been excluded. Furthermore, despite being the largest percentage of the nursing workforce, female nurses were largely represented in the included studies. Hence the experiences reported in the review may not be representative of male nurses.

5. Conclusion

The findings from this review suggest that there is a need for Governments, policy makers, nursing groups and health care organisations to actively engage in supporting nurses both during and following a pandemic or epidemic. This engagement needs to be multifaceted and recognise the importance of nurses and the nursing role to pandemic and epidemic control. It is vital that nurses receive clear, concise and current information about best practice nursing care and infection control, as well as sufficient access to appropriate PPE to optimise their safety. Adequate staffing is essential to ensure that nurses are able to take breaks during shifts, take leave when they are ill and provide appropriate skill mix. Support for nurses to manage competing family responsibilities and maintain safe contact and communication with family members can reduce personal stress and anxiety. Finally, the physical and psychological impact of working during a pandemic or epidemic on nurses needs to be recognised and made visible. To promote physical and mental health among nurses and ensure that they stay in the workforce, Governments, policy makers, nursing groups and health care organisations must closely monitor nurses’ support needs both during the pandemic or epidemic and in the following period and be agile and responsive to these with meaningful support systems. Without this support nurses are likely to experience significant stress, anxiety, and physical side-effects all of which can lead to burnout and loss of nurses from the workforce.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Anderson C., Moxham L., Broadbent M. Teaching and supporting nursing students on clinical placements: Doing the right thing. Collegian. 2018;25(2):231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., 2017. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual Accessed 4 April 2020 https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/.

- Bukhari E.E., Temsah M.H., Aleyadhy A.A., Alrabiaa A.A., Alhboob A.A., Jamal A.A., Binsaeed A.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak perceptions of risk and stress evaluation in nurses. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2016;10(08):845–850. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang H.-H., Chen M.-B., Sue I.-L. Self-state of nurses in caring for SARS survivors. Nursing Ethics. 2007;14(1):18–26. doi: 10.1177/0969733007071353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung B.P.M., Wong T.K.S., Suen E.S.B., Chung J.W.Y. SARS: caring for patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(4):510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D.L., Casken J. Protecting healthcare workers in an acute care environment during epidemics: lessons learned from the SARS outbreak. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2011;4(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: a phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47(5):577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald D.A. Human swine influenza A [H1N1]: practical advice for clinicians early in the pandemic. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2009;10(3):154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannes K., Lockwood C. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta‐aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(7):1632–1642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H.E. A model for collegiality among staff nurses in acute care. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 1995;25(12):11–20. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett B.L., Hewlett B.S. Providing care and facing death: nursing during Ebola outbreaks in central Africa. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2005;16(4):289–297. doi: 10.1177/1043659605278935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd E., McNaught C. The SARS crisis: reflections of Hong Kong nurses. International Nursing Review. 2008;55(1):27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope K., Massey P.D., Osbourn M., Durrheim D.N., Kewley C.D., Turner C. Senior clinical nurses effectively contribute to the pandemic influenza public health response. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing (Online) 2011;28(3):47. [Google Scholar]

- Horton-Deutsch S., Pardue K., Young P.K., Morales M.L., Halstead J., Pearsall C. Becoming a nurse faculty leader: Taking risks by doing the right thing. Nursing Outlook. 2014;62(2):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Lin G., Tang L., Yu L., Zhou Z. Special attention to nurses’ protection during the COVID-19 epidemic. BioMed Central. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L., rong Liu, H., 2020. Emotional responses and coping strategies of nurses and nursing college students during COVID-19 outbreak. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Imai T., Takahashi K., Hoshuyama T., Hasegawa N., Lim M.-K., Koh D. SARS risk perceptions in healthcare workers, Japan. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(3):404. doi: 10.3201/eid1103.040631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives J., Greenfield S., Parry J.M., Draper H., Gratus C., Petts J.I., Sorell T., Wilson S. Healthcare workers' attitudes to working during pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M.J., Turale S. Nurses' experiences of ethical preparedness for public health emergencies and healthcare disasters: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Nursing Health Science. 2014;16(1):67–77. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Sam B., Bull F., Pieh S.B., Lambert J., Mgawadere F., Gopalakrishnan S., Ameh C.A., van den Broek N. ‘Even when you are afraid, you stay’: Provision of maternity care during the Ebola virus epidemic: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2017;52:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.S., Son Y.D., Chae S.M., Corte C. Working experiences of nurses during the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2018;24(5):e12664. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Nurses' experiences of care for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus in South Korea. American Journal of Infection Control. 2018;46(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh D., Lim M.K., Chia S.E., Ko S.M., Qian F., Ng V., Tan B.H., Wong K.S., Chew W.M., Tang H.K. Risk Perception and Impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on Work and Personal Lives of Healthcare Workers in Singapore What Can We Learn? Medical Care. 2005:676–682. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh Y., Hegney D., Drury V. Nurses' perceptions of risk from emerging respiratory infectious diseases: a Singapore study. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2012;18(2):195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh Y., Hegney D.G., Drury V. Comprehensive systematic review of healthcare workers' perceptions of risk and use of coping strategies towards emerging respiratory infectious diseases. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare. 2011;9(4):403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S.K.K., Kwong E.W.Y., Hung M.S.Y., Chien W.T. Emergency nurses’ perceptions regarding the risks appraisal of the threat of the emerging infectious disease situation in emergency departments. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1718468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K.K., Hung S.Y. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2013;21(4):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Liehr P. Instructive messages from Chinese nurses' stories of caring for SARS patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(20):2880–2887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhav N., Oppenheim B., Gallivan M., Mulembakani P., Rubin E., Wolfe N. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd edition. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. Pandemics: risks, impacts, and mitigation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.D., Brown L.M., Reid W.M. Predictors of nurses’ intentions to work during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2013;113(12):24–31. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000438865.22036.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: lessons learned. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2004;359(1447):1117–1125. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M., Doerr H.W., Cinatl J. An influenza A H1N1 virus revival–pandemic H1N1/09 virus. Infection. 2009;37(5):381. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Porritt K., Lockwood C., Aromataris E., Pearson A. Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: the ConQual approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1):108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oandasan R., Baker K., Barker C., Bosco D., D'Amour L., Jones S., Kimpton L., Lemieux-Charles L., Nasmith L., San Martin Rodriguez J., Tepper J., D. Way D. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; Ottawa: 2006. Teamwork in health care: promoting effective teamwork in health care in Canada: policy synthesis and recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett S.M. Professional collegiality and peer monitoring among nursing staff: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013;50(10):1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri L. Nursing Forum. Wiley Online Library; 2010. Concept analysis of interdisciplinary collaboration; pp. 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfrimmer D. Duty to care. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2009;40(2):53–54. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20090201-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale H., Leask J., Po K., MacIntyre C.R. "Will they just pack up and leave?" - attitudes and intended behaviour of hospital health care workers during an influenza pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiao J.S.-C., Koh D., Lo L.-H., Lim M.-K., Guo Y.L. Factors predicting nurses' consideration of leaving their job during the SARS outbreak. Nursing Ethics. 2007;14(1):5–17. doi: 10.1177/0969733007071350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih F.J., Gau M.L., Kao C.C., Yang C.Y., Lin Y.S., Liao Y.C., Sheu S.J. Dying and caring on the edge: Taiwan's surviving nurses' reflections on taking care of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Appl Nurs Res. 2007;20(4):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.K., Fisher J., Schonberg M.A., Pallin D.J., Block S.D., Forrow L., Phillips R.S., McCarthy E.P. Am I doing the right thing? Provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2009;54(1):86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.022. e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.V., Godfrey N.S. Being a good nurse and doing the right thing: a qualitative study. Nursing Ethics. 2002;9(3):301–312. doi: 10.1191/0969733002ne512oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroni K.G., Seibert D.J., Mallinson R.K. Nurses’ perceptions on Ebola care in the United States, Part 2: A qualitative analysis. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2015;45(11):544–550. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E.L., Wong S.Y., Lee N., Cheung A., Griffiths S. Healthcare workers' duty concerns of working in the isolation ward during the novel H1N1 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(9-10):1466–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020. State of the World's Nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadershipAccessed 14 April 2020 https://www.who.int/publications-detail/nursing-report-2020.

- Xie J., Tong Z., Guan X., Du B., Qiu H., Slutsky A.S. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05979-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. the legal duty of care for nurses and other health professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(22):3071–3078. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.