The exponential growth in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) across the UK has been successfully reversed by social distancing and lockdown.1 RNA testing for prevalent infection is a key part of the exit strategy, but the role of testing for asymptomatic infection remains unclear.2 Understanding the determinants of asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic infection will provide new opportunities for personalised risk stratification and reveal much-needed correlates of protective immunity, whether induced by vaccination or natural exposure. To address this, we set up COVIDsortium (NCT04318314), a bioresource focusing on asymptomatic health-care workers (HCWs—doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, administrators, and others) at Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK, to collect data through 16 weekly assessments (unless ill, self-isolating, on holiday, or redeployed) with a health questionnaire, nasal swab, and blood samples and two concluding assessments at 6 month and 12 months. HCWs were self-declared as healthy and fit to work for study visits. Participants were not given swab results, and those with symptoms or in self-isolation resumed study visits on return to work.

Across London, case-doubling time in March, 2020, was approximately 3–4 days. The number of nasal swabs testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 peaked on March 30, 2020, suggesting infections peaked on March 23, 2020, the day of UK lockdown. COVIDsortium was established with all national and local permissions in 7 days. Recruitment started on March 23, 2020, and was completed 8 days later.

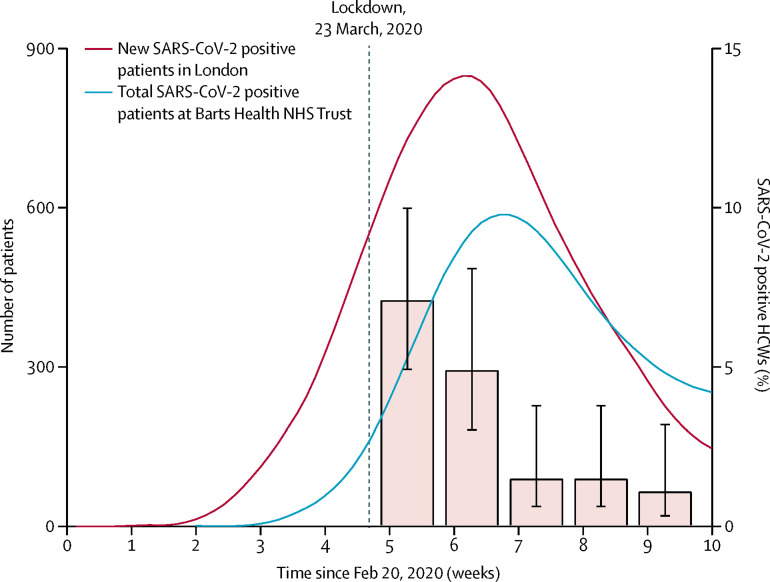

Here we present the SARS-CoV-2 PCR results from nasal swabs collected at the first five time-points from the first 400 participants (figure ). We show the number and percentage of asymptomatic HCWs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on consecutive weeks from March 23, 2020: 28 (7·1%; 95% CI 4·9–10·0) of 396 HCWs in week 1, 14 (4·9%; 3·0–8·1) of 284 HCWs in week 2, four (1·5%; 0·6–3·8) of 263 HCWs in week 3, four (1·5%; 0·6–3·8) of 267 HCWs in week 4, and three (1·1%, 0·4–3·2) of 269 HCWs in week 5 (figure). Seven HCWs tested positive on two consecutive timepoints, and one HCW tested positive on three consecutive timepoints. During this time, 50 HCWs (not necessarily those who were SARS-CoV-2 positive) self-isolated for symptoms. Of the 44 HCWs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 12 (27%) had no symptoms in the week before or after positivity.

Figure.

Number of patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 in Greater London and Barts Health NHS Trust and proportion of the HCW study cohort with SARS-CoV-2-positive nasal swab

The left y-axis shows number of daily new SARS-CoV-2 positive patients in the Greater London area, derived from Public Health England data (red curve) and the total number of SARS-CoV-2 positive inpatients at Barts Health NHS Trust (blue curve). Both curves show 7-day averages. The right y-axis shows the percentage (95% CI) of asymptomatic HCWs in this study with SARS-CoV-2 positive swabs in the first 5 weeks of testing. COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. HCWs=health-care workers.

HCWs have been particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, with high reported rates of infection from Italian data,3 raising concerns about the effectiveness of personal protective equipment and of nosocomial transmission.4 Public fear of hospitals is also currently high, and many serious and treatable diseases are presenting late with adverse outcomes.5 Testing of HCWs has so far been restricted to symptomatic individuals, and no studies have reported serial testing in high-exposure asymptomatic volunteers. If our results are generalisable to the wider HCW population, then asymptomatic infection rates among HCWs tracked the London general population infection curve, peaking at 7·1% and falling six-fold over 4 weeks, despite the persistence of a high burden of COVID-19 patients through this time (representing most inpatients). Taken together, these data suggest that the rate of asymptomatic infection among HCWs more likely reflects general community transmission than in-hospital exposure. Prospective patients should be reassured that as the overall epidemic wave recedes, asymptomatic infection among HCWs is low and unlikely to be a major source of transmission.

These data reinforce the importance of epidemic multi-timepoint surveillance of HCWs. The data also suggest that a testing strategy should link population-representative epidemiological surveillance to predict prevalence, with adaptive testing for symptomatic individuals at times of low prevalence, and rapidly expanding to include the asymptomatic HCWs during possible new infection waves.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the work presented in this Correspondence was donated by individuals, charitable Trusts, and corporations including Goldman Sachs, Citadel and Citadel Securities, The Guy Foundation, GW Pharmaceuticals, Kusuma Trust, and Jagclif Charitable Trust. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, or the decision to publish this Correspondence. The corresponding author had full access to all data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. JCM and CM are directly and indirectly supported by the University College London Hospitals (UCLH) and Barts NIHR Biomedical Research Centres and through British Heart Foundation (BHF) Accelerator Award. TAT is funded by a BHF Intermediate Research Fellowship, MB by the Barts NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, and AM by the Rosetrees Trust. JBA received funding from Sanofi. MN is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator in Science Award and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (UCLH). All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies SPI-M-O: consensus view on behavioural and social interventions. March 9, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/874290/05-potential-impact-of-behavioural-social-interventions-on-an-epidemic-of-covid-19-in-uk-1.pdf

- 2.Black JRM, Bailey C, Swanton C. COVID-19: the case for health-care worker screening to prevent hospital transmission. Lancet. 2020;395:1418–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30917-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Task force COVID-19 del Dipartimento Malattie Infettive e Servizio di Informatica. Istituto Superiore di Sanità Epidemia COVID-19, Aggiornamento nazionale: 23 aprile 2020. April 24, 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Bollettino-sorveglianza-integrata-COVID-19_23-aprile-2020.pdf

- 4.Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]