Abstract

Background

Low ridership of public transit buses among wheeled mobility device users suggests the need to identify vehicle design conditions that are either particularly accommodating or challenging. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of low -floor bus interior seating configuration and passenger load on wheeled mobility device user-reported difficulty, overall acceptability, and design preference.

Methods

Forty-eight wheeled mobility users evaluated three interior design layouts at two levels of passenger load (high vs. low) after simulating boarding and disembarking tasks on a static full-scale low-floor bus mock-up.

Results

User self-reports of task difficulty, acceptability and design preference were analysed across the different test conditions. Ramp ascent was the most difficult task for manual wheelchair users relative to other tasks. The most difficult tasks for users of power wheelchairs and scooters were related to interior circulation, including moving to the securement area, entry and positioning in the securement area, and exiting the securement area. Boarding and disembarking at the rear doorway was significantly more acceptable and preferred compared to the layouts with front doorways.

Conclusion

Understanding transit usability barriers, perceptions and preferences among wheeled mobility users is an important consideration for clinicians who recommend mobility-related device interventions to those who use public transportation.

Keywords: wheelchairs, accessibility, usability, low-floor bus, public transportation

Introduction

Public transit serves as an important means to social participation and access to health, employment and recreational activities for many individuals. It is imperative that transit systems are usable and accessible to the broad diversity of potential users. Substantial advances have been made in accessible transportation due to implementation of various laws and regulations but major barriers and impediments still remain.

General problems facing wheeled mobility device users on low-floor buses

Low-floor buses are the most popular type of urban transit bus used in the US [1]. The relatively low vehicle floor combined with a kneeling feature at stops and electromechanical folding ramps at the doorways reduces the vertical and horizontal gap between vehicle floor and sidewalk. This greatly improves the ease of boarding and disembarking [2, 3]. However, current low-floor bus designs still present safety hazards and usability problems for passengers with mobility impairments [4]. Inadequate seating, crowding and congestion are among the most frequently cited complaints by passengers on low-floor buses [3]. Large wheel-well covers that protrude into the passenger cabin combined with inefficient interior circulation from irregular seating configurations also contribute to these problems [3, 5] and to a lower seating capacity compared to high-floor buses.

Wheeled mobility device users in particular experience more difficulties than their ambulatory counterparts when using low-floor buses due to steep access ramps and limited space for on-board manoeuvring [2, 4, 5]. These problems also increase the risk of injury under non-impact conditions such as when boarding and disembarking [6, 7]. As much as 43% of wheeled mobility device related incidents on public transit occur when the bus is stopped presumably when boarding and disembarking [8].

Understanding how dimensions and configurations of vehicle interiors affect wheeled mobility device user access, comfort and safety is critical due to their unique space requirements, diverse equipment, and high variability of abilities [2, 4]. Bus manufacturers and transit agencies across the US are obligated to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines and Standards [9, 10] but have some flexibility in their approaches to operationalizing provisions of the legislation. As a result, low-floor buses vastly differ in interior seating configurations, door locations and the fare payment system. Design decisions are all interrelated and influence the size and location of wheeled mobility securement areas and the usability of path to and from the accessible doorway(s) during bus boarding and disembarking tasks.

The size, weight and manoeuvring characteristics of wheeled mobility devices vary considerably between device type (e.g., manual wheelchairs, powered wheelchairs and scooters), make, and model [11, 12]. Both manual and powered wheelchairs offer some customizability to fit user needs in postural support, comfort, and ease of use (e.g., leg rests and footrests, tilt and recline) which also impacts space requirements [12, 13]. The choice of drive configuration (i.e., front, mid, and rear wheel-drive) and powered seating options influence manoeuvrability of powered wheelchairs [14]. Scooters typically have a larger turning circle and are less manoeuvrable than wheelchairs because their configuration and chassis length need to accommodate the drive controls (e.g., tiller) and foot placement [14, 15, 16]. These devices tend to be designed and prescribed for outdoor use. They are intended to assist individuals with limited ambulation and good trunk control and sufficient upper extremity function to control the steering tiller, but who also lack the upper extremity stamina or range of motion necessary to use a manual wheelchair. Some users prefer scooters as it may suggest a less debilitating medical condition compared to requiring a wheelchair. Increasing use of scooters among the growing older adult population has put greater emphasis on scooter access in public transit systems.

Previous Usability Research on Transit Vehicle Features by Wheeled Mobility Device Users

A range of methods have been used previously to evaluate designs of transit vehicle interiors by wheeled mobility device users. Methods used in field studies include first-person observations [e.g., 17, 18], on-board surveys to query transit riders on perceptions and problems experienced in the vehicle environment [19], retrospective analysis of incident reports [8], and systematic audits of a predetermined part of a transit system by an observer [20] or researcher and participant [21]. More recent studies have relied on reviewing on-board video surveillance recordings obtained from buses in operation to extract information about the number and duration of boarding and disembarking by passengers using wheeled mobility devices [e.g., 22], and to identify safety-critical incidents involving wheeled mobility device users [e.g., 7]. Field studies are advantageous because they utilize real-world environmental conditions, such as moving vehicles and passenger interaction, providing reliable information on both system performance and passenger experience. However, uncontrolled factors such as passenger flow and crowding can complicate data interpretation. In addition, field studies are constrained by the vehicles that are in operation, which poses challenges to studying new designs that are not yet in service.

Some field studies have focused on evaluating a specific and limited sub-set of bus designs using special buses outfitted for collecting study data either in a static (i.e., parked in a stationary location) or dynamic (i.e., participants undergo simulated bus journeys over a test track or pre-determined route) conditions followed by survey questionnaires administered to participants at the end of the trip [e.g., 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. This method helps overcome the limitation of naturalistic field studies by including specific design conditions and targeted user populations such as seniors and people with disabilities [24, 26, 28]. For example, studies by Petzall [26] and Booz-Allen Applied Research [23] employed the use of bus journeys to study problems regarding usability experienced by users of ambulation aids and of wheeled mobility devices. Following the test trials, researchers interviewed participants to record their opinions of different features on the bus, and their overall preference for the vehicle design.

Laboratory-based human factors research on transit bus usability have largely comprised evaluations of specific components used in the bus environment such as access ramps [29] and wheeled mobility securement systems [30, 31, 32] for comfort, safety, ease-of-use, and efficiency. There are few usability evaluations of the vehicle environment in its entirety during the boarding and disembarking process [24, 33, 34, 35, 36].

Full-scale simulations of buses in the laboratory create the opportunity to test multiple concept designs that may not be available on buses in service or conditions that are difficult to replicate in the real world. Passenger flow and behaviour can also be understood using simulated environments in the laboratory [24, 33, 34, 35, 37]. Static environmental simulations are more amenable for studying the dwell portions of the bus (i.e., boarding, disembarking, and interior circulation) as compared to behavioural measures affected by vehicle dynamics such as ride comfort and safety during abrupt acceleration and deceleration.

Study Objectives

Prior reports [3, 4, 38] suggest that low-floor bus seating layouts with inadequate clear floor spaces and high passenger loading negatively influence the subjective experience of passengers using wheeled mobility devices during boarding and disembarking. However, a systematic assessment of the relative severity of the difficulty experienced, the acceptability of these conditions, and preferences of wheeled mobility device users across multiple vehicle interior configurations through the entire boarding and disembarking process has not received research attention.

The objective of this study was to determine the effects of low-floor bus interior seating configuration and passenger load on wheeled mobility device user-reported difficulty, overall acceptability, and design preference during boarding, interior circulation, and disembarking. The goals were to: (1) identify tasks that were most difficult for wheeled mobility device users during boarding and disembarking, (2) examine differences in user-reported task difficulty across wheeled mobility device users and environmental design conditions, and (3) identify wheeled mobility device user preferences for vehicle interior layout conditions based on acceptability ratings and a ranking of design preference.

Methodology

Study sample

Forty-eight wheeled mobility device users were recruited for this study. Inclusion criteria required the ability to navigate a 5 degree (1:12) access ramp slope without assistance. To ensure diversity in participant demographics and transportation modes used, participants were recruited through multiple sources, including a local independent living centre, geriatric centre, a Veterans Affairs Medical Center, the university community, and recruitment flyers posted at the local public transit terminal. The study intentionally sought participants using different transport modes to also capture the preferences and needs of those individuals who currently did not use public transit. The university’s institutional review board approved the study procedures and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participants received $50 USD monetary compensation for their time.

Experiment apparatus

The low-floor bus seating configurations were selected through a multi-stage process to ensure that each of the designs was feasible and relevant. An initial understanding of the diversity of current low-floor bus interior seating configurations was first obtained by reviewing interior configurations of 12-m (40-ft.) length low-floor buses used by different transit agencies in the US (e.g., LA Metro – Los Angeles, WMATA - Washington, D.C., Trimet – Portland, Port Authority – Pittsburgh, MTA – New York City, MBTA – Boston, MARTA – Atlanta). Representatives from industry and technical staff at a local transit agency identified five of the most promising designs to evaluate based on technical consistency, feasibility, and compliance with existing accessibility standards for transportation vehicles [9, 10]. Following feedback from industry representatives three bus interior layouts were selected for inclusion in the study.

A full-scale mock-up of the front two-thirds (i.e., the entire low floor section) of a 12 m (40 ft.) long low-floor bus was constructed in a laboratory to systematically assess user experiences across the three bus design configurations [36]. The mock-up featured reconfigurable seating arrangements and securement areas locations, adjustable front-wheel well widths, different fare-payment technologies and assist features e.g., hand-holds, vertical stanchions. Key features of the three layouts are summarized in figure 1. Commercial electromechanical access ramps 790 mm (31 in.) wide located at the forward and rear doorway produced a slope of 9.5 degrees (1:6) when lowered to boarding platforms that were positioned outside the bus mock-up. This represents the maximum allowable gradient for transit vehicle access ramps in the US. The inclined portion of the ramp at the forward doorway was 1880 mm (74 in.) in length with 686 mm (27 in.) extending into the bus cabin. The ramp at the rear doorway was 1194 mm (47in.) in length with the entire inclined surface located outside the bus. The aisle width between the front wheel-well covers was 915 mm (36 in.). Two on-board fare payment device designs were used in this study, a compact card-reader mounted on the side panel at the rear doorway (i.e., Layouts 2 and 3) and a conventional floor-mounted fare machine at the forward doorway in Layout 1. In all cases a proximity card was used which did not require physical contact with the card-reader.

Figure 1.

Plan views and key features of the three bus layout configurations selected for study. Mannequin placement for simulated conditions of low (light grey) and high (both light and dark grey) Passenger Load are also depicted. Table modified from [36].

The number of occupied seats and unoccupied wheeled mobility securement areas was manipulated to simulate crowding conditions found in the physical environment. Passenger load, a measure of the utilization of the total seating capacity and calculated as the ratio of occupied and total seats, was kept approximately constant across layouts. Clothed adult-sized inflatable mannequins were strategically placed on-board to create high and low passenger load conditions (figure 1). Mannequins coloured light-grey in figure 1 were present for the conditions representing low passenger load, while both light- and dark-grey coloured mannequins were present for conditions of high passenger load. Wheeled mobility securement areas were equipped with fold-up seats for use by other ambulatory passengers when the securement area was not occupied by a wheeled mobility device. Participants were required to lift up the folding seats prior to entering the device securement area. Both securement areas were available to the wheeled mobility device user in conditions simulating low passenger load. In conditions of high passenger load, only one of the securement areas was available for use, with the second area consistently occupied by a mannequin seated in a manual wheelchair (760 mm width x 1220 mm length) secured with a four-point tie-down system.

Experimental procedure

Participants were first administered a questionnaire to obtain information about their age, gender, health condition and mobility impairment, type of wheeled mobility device used, length of time using a wheeled mobility device, and experience using public transportation. The experiment procedure required participants to perform six independent timed boarding and disembarking trials using the bus mock-up (i.e., 3 layouts at two levels of passenger load each). The general sequence of boarding and disembarking tasks performed by the participant included: (1) ramp ascent using an entry door specific to the vehicle layout, (2) fare payment with a proximity card, (3) moving to the securement area, (4) entering and positioning in securement area, (5) exiting the securement area, (6) moving to the exit door specific to the vehicle layout, and (7) ramp descent.

The presentation order of the three bus layouts was counterbalanced across participants with passenger load nested within each layout. Participants were instructed to complete the different tasks as they normally would when using public transit, and completed one practice trial for each bus layout. One researcher was the interviewer and provided instructions and descriptions for the experimental trials, and administered the post-trial questionnaire. A second researcher assumed the role of the bus driver and made announcements about when to begin boarding and disembarking, and assisted with ramp ascent, fare payment, or lifting up the seats if requested by the participant during the trial. Two additional team members served as spotters near the access ramp ready to intervene in case the participant showed signs of wheelchair instability, or potential loss of balance or fall. To reduce effects of fatigue, participants received rest breaks of at least 10 minutes between changes in layout conditions and of at least 5 minutes between changes in passenger load conditions. Additional rest time was provided if requested. The experiment was conducted with one participant at a time, and required between 2.5 – 3.0 hours to complete.

Post-trial Questionnaire Instruments

Following each trial the participant completed a questionnaire that had items on: (1) task difficulty for each of the above seven tasks using the Difficulty Rating Scale, (2) acceptability of the overall boarding and disembarking experience combined using the Acceptability Rating Scale, and (3) rank ordering their preference for the most recently evaluated condition in relation to previous test conditions with the help of visual aids depicting a plan view of the layout and passenger load. Participants were asked to provide comments supporting their ratings.

The Difficulty Rating Scale and Acceptability Rating Scale were originally developed as measures of environmental usability [39, 40]. The Difficulty Rating Scale measures perceived ease or difficulty of task completion using a 7- point ordinal scale ranging from −3 (very difficult) to +3 (very easy). Respondents rate perceived task difficulty in two steps: (i) indicate if a completed task was “difficult”, “moderate”, or “easy”; and (ii) choose a final rating from three possible options based on the general rating provide in the first step. Likewise, the Acceptability Rating Scale measures acceptability of a task in a two-step rating process using a 7-point ordinal scale ranging from −3 (very unacceptable) to +3 (very acceptable). These measures have demonstrated convergent validity with other functional measures of task performance when using in-door environments [40] and access ramps on buses [29].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package R v.3.1. [41]. Summary statistics were computed on the sample demographics and the nine user-reported dependent variables, namely:

Difficulty ratings obtained for the seven tasks, viz., ramp ascent, fare payment, moving to the securement area, entry and positioning in the securement area, exiting the securement area, moving to the exit door, and ramp descent, using an ordinal scale ranging from −3 (very difficult) to +3 (very easy).

Acceptability ratings for each of the six experimental trials obtained using an ordinal scale ranging from −3 (very unacceptable) to +3 (very acceptable).

Preference rankings for the six environmental design conditions from 1 (most preferred) to 6 (least preferred).

Three-way mixed design nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests [42, 43] using the R-software package ‘nparLD’ [44] were performed on each of the above nine dependent variables. User Group (i.e., manual wheelchair, power wheelchair, and scooter users) was the between-subjects variable and Layout (1, 2 and 3) and Passenger Load (high vs. low) were within-subjects variables. All two- and three-way interactions were included in the three-way ANOVA models.

All significant main and interaction effects (p < 0.05) were further evaluated using the R-software package ‘nparcomp’, a nonparametric rank-based multiple contrast test procedure (similar to ‘nparLD’) that computes simultaneous confidence intervals and p-values for linear paired comparisons while controlling the family-wise Type I error rate [45]. Custom Tukey-type contrasts for significant interaction effects were constructed to analyse paired comparisons between levels of one factor at each level of the second factor. The study team opted to use the ‘nparLD’ and ‘nparcomp’ packages as these do not require any assumption on the underlying distribution function and are particularly useful when analysing mixed effects in unbalanced datasets with either ordinal or continuous dependent variables.

Observations of the users’ performance during each trial and responses to open ended questions regarding design challenges and affordances provided insights about the self-reported ratings of sub-task difficulty, overall acceptability and design preference.

Results

Sample Demographics

The study sample consisted of 18 manual wheelchair (MWC) users, 21 powered wheelchair (PWC) users and 9 scooter users, with roughly equal number of men (54%) and women (46%). The mean age was 50.2 (SD = 10.5, range = 25 – 68) years, the mean duration using a wheeled mobility device was 7.4 (SD = 7.9, range = 0.08 – 38) years. MWC users on average were younger (mean = 46.7, SD = 7.9, range = 27 – 58 years) compared to PWC users (mean = 50.4, SD = 10.8, range = 25 – 62 years) and scooter users (mean = 56.8, SD = 12.1, range = 31 – 68 years) however these differences in age were not significant (F (2, 45) = 3.032, p = 0.058). User groups differed in their experience of using a wheeled mobility device (F (2, 45) = 4.868, p = 0.012). MWC users reported use of a mobility device for significantly greater period of time (mean = 11.4, SD = 10.1, range = 1 – 38 years) compared to PWC users (mean = 5.1, SD = 4.8, range = 0.08 – 20 years; t (0.05, 45) = 2.73, p = 0.018) and scooter users (mean = 4.6, SD = 5.3, range = 0.17 – 16 years; t (0.05, 45) = 2.53, p = 0.030). Ten participants (21%) were left-hand dominant.

Participants reported a broad range of medical conditions, with cerebral palsy (29%), multiple sclerosis (10%) and paraplegia (10%) being the most frequently reported. Three participants categorized as ‘Other’ included individuals with COPD, a foot ulcer, and a liver transplant. Ambulation capabilities among the participants was low with 21 participants (44%) indicated being unable to walk or use stairs, and an additional 17 (35%) reported having a lot of difficulty walking or using stairs. Forty-four participants (92%) indicated having little to no difficulty with upper extremity function such as using handrails or grab-bars.

Approximately half the sample had some prior experience using fixed route bus services (Table 1). Participants reported using a range of different transport modes including fixed route bus (48%) and metro rail (56%) services with varying frequency suggesting some familiarity with the local public transit system. Half the sample (50%) occasionally used demand response services like paratransit, while others never use public transit or rarely travel outdoors more than once a month.

Table 1.

Self-reported frequency of use of different transportation modes stratified by user group (n = 48). MWC: Manual Wheelchair Users; PWC: Power Wheelchair Users.

| Transport modes used | User Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWC (n = 18) | PWC (n = 21) | Scooter (n = 9) | Total (n = 48) | |

| Fixed Route Bus | ||||

| >= once per week or more | 17% (3) | 24% (5) | 22% (2) | 21% (10) |

| >= once per month | 28% (5) | 33% (7) | 11% (1) | 27% (13) |

| Never | 56% (10) | 43% (9) | 67% (6) | 52% (25) |

| Light rail, metro | ||||

| >= once per week or more | 22% (4) | 19% (4) | 33% (3) | 23% (11) |

| >= once per month | 33% (6) | 38% (6) | 22% (2) | 33% (16) |

| Never | 44% (8) | 43% (9) | 44% (4) | 44% (21) |

| ADA Paratransit | ||||

| >= once per week or more | 22% (4) | 19% (4) | 22% (2) | 21% (10) |

| >= once per month | 17% (3) | 48% (10) | 11% (1) | 29% (14) |

| Never | 61% (11) | 33% (7) | 67% (6) | 50% (24) |

| Private automobile | ||||

| >= once per week or more | 72% (13) | 38% (8) | 56% (5) | 54% (26) |

| >= once per month | 22% (4) | 29% (6) | 33% (3) | 27% (13) |

| Never | 6% (1) | 33% (7) | 11% (1) | 19% (9) |

Ratings and Preferences

Figures 2, 3 and 4 provide the median values for the seven sub-task difficulty ratings by Layout and Passenger Load for users of MWCs, PWCs, and scooters, respectively. The data indicates a greater difficulty in ramp ascent for MWC users, and generally an increased difficulty for all user groups in tasks related to interior circulation (i.e., moving to the securement area, entering and positioning in securement area, exiting the securement area, and moving to the exit door), particularly in conditions of high Passenger Load.

Figure 2.

Median task difficulty ratings (−3 = very difficult, 3 = very easy) Layout and Passenger Load conditions for manual wheelchair users (n = 18).

Figure 3.

Median task difficulty ratings (−3 = very difficult, 3 = very easy) by Layout and Passenger Load conditions for power wheelchair users (n = 21).

Figure 4.

Median task difficulty ratings (−3 = very difficult, 3 = very easy) by Layout and Passenger Load conditions for scooter users (n = 9).

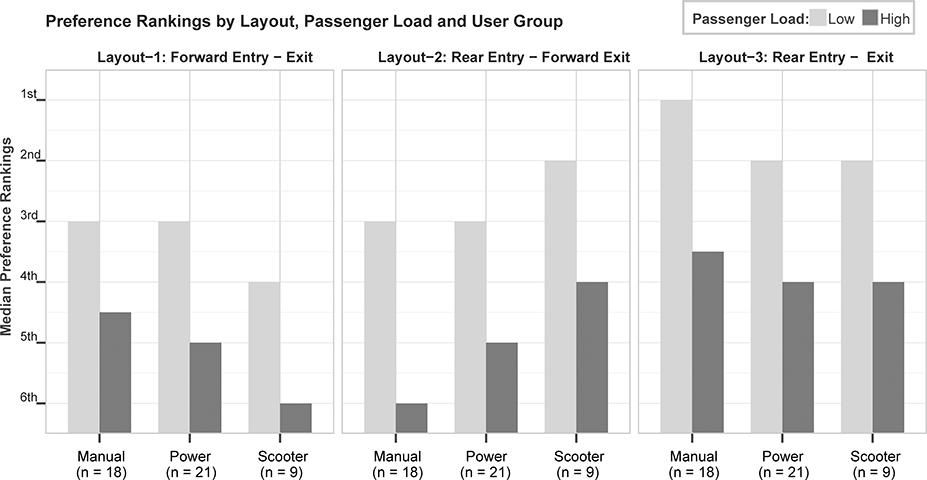

Median overall acceptability ratings and median preference rankings stratified by User Group, Layout and Passenger Load are shown in figures 5 and 6, respectively. Layout 1: Forward Entry – Exit was and Layout 3: Rear Entry – Exit was generally acceptable to users of MWCs and PWCs in conditions of low and high Passenger Load, but moderately unacceptable and neutral for scooter users in conditions of high Passenger Load. The median acceptability rating in Layout 2: Rear Entry – Forward Exit for MWC users was negative. Median preference rankings were generally higher in Layout 3 across User Group (figure 6). Median rankings were also more diverse in conditions of High vs. Low Passenger Load.

Figure 5.

Median values for overall acceptability rating (−3 = very unacceptable, 3 = very acceptable) stratified by layout, passenger load, and user group (manual, power and scooter device users).

Figure 6.

Median values for preference rank (1st = most preferred, 6th = least preferred) stratified by layout, passenger load, and user group (manual, power and scooter device users).

Table 2 presents summary results from the three-way nonparametric ANOVA tests performed on the seven sub-task difficulty ratings, overall acceptability rating and preference ranking to examine differences across User Group, Layout and Passenger Load. None of the three-way interaction effects were statistically significant. Following is a description of the ANOVA results for each dependent measure along with key themes identified in the participants’ comments provided during the rating procedure.

Table 2.

Summary results for the significant main and interaction effects (p < 0.05) and pair-wise Tukey comparisons of interest (p < 0.05) from the non-parametric three-way mixed effects analysis of variance for user-reported task difficulty, overall acceptability rating, and preference rank. None of the three-way interactions were significant and hence not shown. MWC: Manual Wheelchair Users; PWC: Power Wheelchair Users; L1: Layout 1: Forward Entry – Exit; L2: Layout 2: Rear Entry – Forward Exit; L3: Layout 3: Rear Entry – Exit.

| Dependent Variable | User Group | Layout | Passenger Load | User Group × Layout | Layout × Passenger Load | User Group × Passenger Load |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

User-reported Difficulty (−3 = very difficult; +3 = very easy) |

||||||

| 1. Ramp Ascent |

F = 19.227, p < 0.001 (PWC, Scooter) > MWC |

F = 6.639, p = 0.004 L3 > L1 |

- | - | - | - |

| 2. Fare Payment | - |

F = 6.119, p = 0.005 (L2, L3) > L1 |

- | - | - | - |

| 3. Moving to Securement Area | - |

F = 4.705, p = 0.012 L3 > L1 |

F = 35.573, p < 0.001 Low > High |

- |

F = 14.729, p < 0.001 L2: Low > High Low: L2 > L1 High: L3 > L2 |

|

| 4. Entry & Positioning in the Securement Area | - | - |

F = 15.707, p < 0.001 Low > High |

- | - | - |

| 5. Exiting the Securement Area | - | F = 3.814, p = 0.025 |

F = 11.19, p < 0.001 Low > High |

- |

F = 14.162, p < 0.001 L3 : Low > High High: L1 > L3 High: L2 > L3 |

- |

| 6. Moving to Exit Door | - | - |

F = 10.004, p = 0.002 Low > High |

- | F = 5.127, p = 0.007 | - |

| 7. Ramp Descent |

F = 5.281, p = 0.01 PWC > MWC Scooter > MWC |

- | - | - | - | |

|

Overall Acceptability (−3 = very unacceptable; +3 = very acceptable) |

- | - |

F = 46.16, p < 0.001 Low > High |

- | - |

F = 3.043, p = 0.048 MWC: Low > High PWC: Low > High |

|

Preference Ranking (1 = most preferred; 6 = least preferred) |

- |

F = 5.348, p = 0.007 L3 < L1 L3 < L2 |

F = 96.741, p < 0.001 Low < High |

F = 2.739, p = 0.04 MWC: L3 < L2 |

- | - |

Ramp Ascent

Difficulty ratings for ramp ascent were significantly different across User Group (p < 0.001), with MWC users reporting greater difficulty (i.e., lower rating) than users of PWCs and scooters. Difficulty ratings also differed statistically by Layout (p = 0.004). Boarding at the forward doorway (Layout 1) was rated more difficult compared to layouts with rear boarding, i.e., Layouts 2 and 3. Not surprisingly, Passenger Load had no impact on difficulty in ramp ascent.

MWC users were observed relying on the handrails for ramp ascent, requesting driver assistance with wheelchair propulsion (n = 3, 16.7%) or boarding the ramp facing rearwards (n = 3, 16.7%) as compensatory strategies. A few PWC users expressed concerns about inadequate ramp width (n = 3; 14.3%), however the majority of PWC users and scooter users had no difficulty with ramp ascent.

Fare Payment

Difficulty ratings for the fare payment task differed significantly by Layout (p = 0.005), with fare payment using the side-mounted card reader at the rear doorway (i.e., Layouts 2 and 3) rated significantly easier compared to the floor-mounted fare machine used at the forward doorway, i.e., Layout 1. No significant differences across User Group and Passenger Load were found.

Problems with the floor-mounted fare machine at the front doorway in Layout 1 included inconvenient and inadequate manoeuvring space for all user groups. Users of PWCs and scooters had difficulty approaching and reaching to the fare-card reader, while some were unable to obtain a direct line of sight to the display screen. The absence of a levelled floor near the fare-box at the front doorway (Layout 1) also caused problems for MWC users requiring them to either “lock the wheelchair” or “hold on to wheel with one hand to prevent it from rolling back”. A levelled and unobstructed floor space combined with a side approach were stated as primary reasons for preferring the fare-payment condition at the rear doorway in Layouts 2 and 3.

Moving to the Securement Area

Difficulty ratings for moving to the device securement area were statistically similar across User Group but differed significantly across Layout (p = 0.012). Participants reported significantly greater difficulty in Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) compared to Rear Entry – Exit (Layout 3) condition. Significantly greater difficulty was observed in conditions of high vs. low Passenger Load (p < 0.001).

Post-hoc analysis of the significant interaction effect between Layout and Passenger Load showed significantly greater task difficulty ratings in high vs. low Passenger Load in the Rear Entry – Forward Exit condition (i.e., Layout 2; with longitudinal seating throughout) but not for Layouts 1 and 3. Further, significantly greater difficulty was noted in Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) over Layout 2 in conditions of low Passenger Load, and in the Rear Entry – Forward Exit condition (i.e., Layout 2) over Rear Entry – Exit (Layout 3) conditions of high Passenger Load.

Entry and Positioning in the Securement Area

The task of entering and positioning in the securement area was rated significantly more difficult (i.e., lower) in conditions of high compared to low Passenger Load (p < 0.001), independent of User Group or Layout. Scooter users reported marginally greater difficulty in completing this task compared to users of MWCs and PWCs but this difference was not statistically significant.

Unlike the Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) condition, entry and positioning in the securement area in conditions with Rear Entry (i.e., Layouts 2 and 3) did not require users to perform a 180-degree turn. However, this advantage was less prominent in conditions of high Passenger Load. Participants found the space to be quite inadequate resulting in accidental collisions or requests for operator assistance to create more space by repositioning the other wheelchair. In conditions of low Passenger Load in the Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) condition, a few users also “lifted (folded up) seats on both sides (of the bus) to make space” anticipating problems in a 180-degree turn.

Twelve of the 48 (25%) of manual and power wheelchair users reported difficulties with lifting the fold-up seats in the securement area due to insufficient upper extremity strength and the inability to get close enough to the seat lever. In these cases, help from the bus operator was sought for lifting the seats after an initial attempt or immediately upon fare payment. Difficulty locating the lever for unlocking and folding the seats was also a problem. In the Rear Entry – Forward Exit condition (i.e., Layout 2) two participants moved past the lever and hence had to rotate and reach posteriorly to operate the lever.

Exiting the Securement Area

Analysis of the difficulty ratings for exiting the securement area showed significant differences across Layout (p = 0.025) and Passenger Load (p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis of the interaction between Layout and Passenger Load showed greater difficulty in high vs. low Passenger Load for Layout 3 (i.e., rear disembarking). Significant differences were also observed in high Passenger Load conditions, with greater task difficulty in Layout 3 (i.e., rear door egress requiring a 180-degree to exit the securement space) compared to Layouts 1 and 2 (i.e., exiting at the front doorway).

Moving to the Exit Door

The reported difficulty for moving to the exit door was significantly greater (i.e., lower rating) in conditions of high vs. low Passenger Load (p = 0.002). Analysis of the interaction effect between Layout and Passenger Load did not show statistically significant differences in pairwise comparisons.

Ramp Descent

Difficulty in ramp descent differed significantly across User Group (p = 0.010), with MWC users reported greater difficulty (i.e., lower rating) compared to users of PWCs and scooters. Ramp descent in Layout 1 was rated slightly more difficult but not significantly different compared to Layouts 2 and 3 (i.e., conditions with the fare payment device at the rear-doorway), the presence of the floor mounted fare payment device being one key difference in design. Nine participants commented that approaching and aligning onto the ramp for descent was more problematic at the front doorway with a “sharp turn right by the driver seat”. These users opted to “grab the handrails to control the descent” or requested verbal cues from the operator “to help keep straight on the ramp.”

Overall Acceptability Rating

There was a significant interaction between User Group and Passenger Load (p = 0.048). Users of MWCs and PWCs rated test conditions with low Passenger Load significantly more acceptable compared to high Passenger Load. Acceptability ratings by scooter users were general lower compared to users of MWCs and PWCs but did not show significantly differences across Passenger Load.

Ranking of Design Preference

Preference rankings for the six test conditions differed significantly by Layout (p = 0.007) and not by User Group. Rear Entry – Exit (Layout 3) was ranked significantly higher compared to Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) and Rear Entry – Forward Exit (Layout 2) independent of User Group and Passenger Load. Overall, conditions with low Passenger Load were rated significantly better than high Passenger Load independent of User Group or Layout (p < 0.001). The exception was among scooter users where Rear Entry – Exit (Layout 3) in high Passenger Load was preferred over Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) in low Passenger Load. A post-hoc analysis of the significant interaction between User Group and Layout indicated a significantly higher preference for Rear Entry – Exit (Layout 3) compared to Rear Entry – Forward Exit (Layout 2) among MWC users.

Discussion

Boarding and Disembarking Task Difficulty

Although they were all compliant with federal design standards for accessibility [9, 10], the three vehicle configurations evaluated in our study posed different usability challenges to wheeled mobility device users.

Ramp Usage during Boarding and Disembarking

Analysis of user-reported difficulty ratings revealed the most difficult tasks for MWC users include ramp ascent followed by ramp descent to a lesser extent. The access ramps at the front and rear-doorway in this study were at a slope of 9.5 degrees (1:6). This slope was less than the maximum gradient of 14.0 degrees (1:4) currently permissible for access ramps by federal standards for transit vehicle accessibility [10] yet posed problems for manual wheelchair users. Recent laboratory studies on ramp usability [29] and naturalistic field studies on boarding and disembarking [8] support our findings on problems faced by wheeled mobility device users when using access ramps. Lower ramp slopes may reduce difficulty in using the ramp, fare payment and traveling to the securement area, especially when boarding at the forward doorway (Layout 1). Lenker, Damle [29] recommend a slope of 1:8 for access ramps as best practice though achieving this would require improving the design of ramps and/or conditions at bus stop pads (e.g., raised concrete platforms).

Interestingly, three manual wheelchair users and one scooter user in our study opted to ascend the access ramp facing rearwards since they had some lower extremity function but insufficient upper extremity strength or impairment (e.g., shoulder pain) to propel up the ramp. This strategy of ascending the access ramp facing rear-wards led to subsequent problems and unsafe conditions in the bus interior when positioning for fare payment, and manoeuvring to the securement area while avoiding accidental contact with passengers. A retrospective analysis of ramp ascent from bus surveillance footage by Frost, Bertocci [6] noted significantly greater number of adverse incidents (such as impacting the ramp edge barrier or vehicle door, requiring multiple forward/reverse manoeuvres) for wheeled mobility device users that ascended the ramp in a rear-facing vs. a forward-facing orientation. In their study, wheeled mobility device users in 27.2% (68 of 250) of the boarding observations ascended the ramp rear-facing and were mostly PWC users (48.5%) followed by MWC users (39.7%) and scooter users (11.8%).

Fare Payment

Fare payment was a comparatively easier task than ramp ascent and descent (for MWC users) and interior circulation. However, difficulties with fare payment were encountered with fare payment at the front doorway using the conventional floor-mounted fare payment device which requires users to perform an extended reach. Based on measurements made on buses in operation, the top of the standard floor-mounted fare machine in the mock-up was 1195 mm (47 in.) high and with the card reader at 1140 mm (45 in.) from the floor. Although compliant with accessibility guidelines, these dimensions coupled with the lack of knee and toe clearance space which limits a forward approach and considerable trunk involvement in a forward lean places the card reader outside the comfortable reach zone. Design improvements are needed that involve lowering or relocating the fare-box to improve reach and line of sight. Users expressed general satisfaction with the proximity card as it did not require handling coins, producing exact change or performing a precise reaching motion such as when inserting coins or swiping a magnetic strip card.

Interior Circulation

Interior circulation was found to be problematic particularly in conditions of high Passenger Load and for users of scooters and PWCs when a 180 deg. turn was required. Moving to the securement area in the Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) condition required wheeled mobility device users to move past the wheel-wells over the front axle to reach the securement space. For all three layouts, the presence of the other wheelchair on-board in conditions of high Passenger Load greatly impeded circulation, with users across all three groups reporting accidental collisions with the wheelchair, wheelchair tie-downs, and needing driver assistance to create more space by displacing fellow passengers. Instances and concerns of accidental collisions were more severe in conditions of high Passenger Load in Layout 2 (i.e., longitudinal seating), wherein the user had to manoeuvre around the wheelchair and run the risk of “running over people’s feet” on the road-side or “bumping into the other wheelchair and tie-down” on the curbside, in stark contrast to low Passenger Load when the aisle is completely unobstructed. When exiting the securement area, users of power chairs and scooters reported experiencing “a tight space” and “getting stuck coming out of the aisle” across all three layouts, particularly in conditions of high Passenger Load when impeded by the second wheelchair and the wheelchair tie-down system. When moving to the exit door, comments by users reflected in adequate manoeuvring space near the wheel-wells in Layouts 1 and 2 that required disembarking at the front doorway, collisions with the wheelchair tie-downs and with the base of the floor-mounted fare-box in the Forward Entry – Exit (Layout 1) condition. Collisions with the wheelchair tie-down and the second wheelchair were also reported under high Passenger Load in the Rear-Exit condition (Layout 3).

Our findings indicate that scooter users report greater difficulty with interior circulation compared to MWC and PWC users regardless of the vehicle layout. Prevailing conditions on low-floor buses could deter scooter users from using public transit altogether. This could explain the smaller samples of scooter users observed in naturalistic field observation studies on public transit [8, 46] and consequently an under-reporting of related transportation issues in research literature.

Self-reported Difficulty, User Preference and other Measures of User Performance

Analysis of preference rankings and acceptability ratings suggest that users favoured an interior layout configuration with boarding and disembarking at the rear doorway, i.e., Layout 3 in this study. This condition allowed for a more straightforward entry into the securement area but a difficult 180-degree turn during disembarking. One explanation from participants preferring this layout was that it afforded time on-board to anticipate and plan the 180-degree turn prior to disembarking. Interior configurations requiring complex manoeuvres during the boarding phase, which are not necessarily anticipated prior to boarding (e.g., Layout 1) or posed undue risk to fellow passengers causing anxiety (e.g., Layout 2), were rated less favourably. Boarding and disembarking times and frequency of critical incidents, while only moderately correlated with difficulty ratings were on average lower in Layout 3 supporting the findings of this study [36, 47].

Stress and Anxiety

Participants in this study reported being stressed as they would when using public transit due to space constraints, time pressure (reinforced by instructions from the experimenter to be mindful of time as they normally would in real life), and being alert of the personal space of co-passengers represented by mannequins. Participants also made unprompted comments that the presence of real people (as opposed to mannequins) would have further influenced their ability to perform the necessary manoeuvres. Some felt they would become self-conscious while others expressed concerns over potential for injury to other passengers. Yet others were concerned that passengers might not be willing to move and allow them space to turn. Such stress or anxiety associated when traveling in crowds may cause users to avoid public transit entirely.

A natural tendency to avoid delays and minimize inconvenience to others can also induce unsafe behaviour such as opting not to secure the wheelchair, avoiding assistance with using the access ramps, or hurrying through with ramp ascent and descent and thereby comprising individual safety. Previous studies suggest high prevalence of misuse or non-use of the wheelchair tie-down system in the field [7, 48, 49, 50, 51] placing wheeled mobility device users at an increased risk of injury during travel [52]. While the usability of these systems has been studied extensively, other inefficiencies in the boarding process such as ramp ascent and interior circulation could result in avoiding tasks related to wheelchair and occupant securement, which may be perceived as unnecessary or optional in an attempt to minimize further delay.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Understanding transit usability barriers, perceptions and preferences of wheeled mobility users is an important consideration for clinicians prescribing mobility-related device interventions. We highlight two specific considerations, namely, wheeled mobility device selection and skills training.

Wheeled mobility device selection

PWCs in our study were pre-dominantly mid-wheel-drive (n = 16, 73%) which are more manoeuvrable in confined spaces [14]. Research on the shapes and sizes of wheeled mobility devices currently in use indicate that there is great diversity in device types (including within categories of manual wheelchairs, powered wheelchairs, and electric scooters) [11, 12] and a trend towards larger occupied device dimensions than decades previous [2, 4, 13, 53]. This complicates wheelchair accommodation on low-floor buses. The Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines for transportation vehicles currently requires a minimum of two wheeled mobility securement areas each with a minimum size of 760 mm x 1220 mm (30 in. x 48 in.) to be provided in vehicles greater than 12 m (22 ft) in length [9]. Very few securement areas in reality exceed these dimensions. However, static measurements of occupied width and length on 369 wheeled mobility devices in the U.S. found that approximately 30% of occupied manual wheelchairs and 50% of occupied power wheelchairs and scooters exceed these minimum dimensions [13]. The consensus view among transit operators is that the full range of scooters are unlikely to be compatible with the full range of buses and that any policy of full access would be difficult to operate in practice [38]. These problems are not unique to the US. Research studies from the UK suggest similar concerns regarding increased wheeled mobility sizes and challenges to accommodation on public transit vehicles [54]. Given prevailing standards provisions, rehabilitation engineers and therapists need to consider the transportation needs of clients and the occupied device size relative to the space available for wheelchair circulation and securement areas on contemporary low-floor buses.

Wheeled mobility skills and transit training

Findings from this study support the notion that the design and manoeuvring characteristics of wheeled mobility devices combined with the operating skill of the user influences efficient interior circulation on transit vehicles [53]. Furthermore, our findings provide insights into manoeuvring skills necessary for successful boarding and disembarking, and translate into training goals and interventions to improve the functional capacity of wheeled mobility device users to meet the demands of using public transit vehicles in a safe and efficient manner. For instance, clinicians need to make sure MWC users can push their chair up and down a narrow ramp. Users of PWCs and scooters need to demonstrate the ability to manoeuvre tight spaces, and with other people in close proximity. Wheeled mobility device users also need to have the seated reach necessary for fare payment on transit buses in their region. Future studies should aim to quantify the effects of such training interventions on outcomes such as transit use, consumer satisfaction, quality of life and social participation. Lastly, clinicians can recommend clients to services that provide travel training on how to use local public transit in a safe and efficient manner.

Self-reported measures of performance along with objective measures such as the duration and level of assistance required for boarding and disembarking using full-scale mock-ups may provide an alternate model for determining readiness for using fixed-route buses or eligibility for paratransit. In an effort to reduce strain on the paratransit service, many transit agencies have constructed indoor bus mock-ups which are used both for travel training and assessing paratransit eligibility. Training increases confidence in the rider’s ability to navigate the fixed-route system and improves coping skills. Some agencies use actual vehicles to do training and eligibility evaluations at housing locations, social and recreation centres.

Study Limitations

Data collection occurred in an idealized laboratory environment using a static mock-up of a low-floor bus. Thus the results do not reflect the potential influence of outdoor environmental factors such as temperature, rain, snow, and noise, vehicle dynamics (e.g., anxiety about the bus starting to move before the passenger is seated) and psychosocial considerations (e.g., presence of co-passengers). Nonetheless, this research provides a baseline of best-case performance that can be a useful basis for comparisons with future field studies in real-world environments. Controlled laboratory studies such as this provide the opportunity to make detailed functional assessments and performance measurements, but they do limit inferences on the relationship between environmental conditions, user characteristics and task performance to the conditions studied. For example, the advent of automated vehicles will present new problems and opportunities due to the lack of drivers. On the one hand, the design of automated vehicles will necessitate a higher standard of usability to insure independent use without driver assistance. On the other hand, such vehicles will have more space due to the removal of driver stations and fare machines.

Seating configurations and securement areas on low-floor buses can differ by vehicle manufacturer and requirements specified by transit agencies during vehicle procurement. Only three layouts were compared in this study. Over time, the simulation environment can be used to test and develop accessibility benchmarks for a broader range of bus layouts, wheelchair securement technologies, wheeled mobility device types, with updates as new technologies and models evolve. For example, studies in Europe have shown that rear-facing securement areas are safe and time-efficient in urban buses, but some users dislike being the only ones traveling on the bus facing rearwards [19].

The study presently focused only on barriers and facilitators to usability relating to the physical bus environment. Quantitative measurements of the relative importance of barriers in the physical and psychosocial environment spanning the entire travel chain are needed [55]. Wheeled mobility device users were evaluated in this study to address a demonstrated need for improved usability [4, 5, 7] in light of proposed and subsequently finalized changes to U.S. accessibility guidelines that could impact wheeled mobility device users on transit buses [56]. As part of an inclusive design process addressing the design needs of other user groups, including older adults, users of ambulation aids, and persons with sensory and cognitive impairments are also necessary [57, 58].

Conclusions

This study identified tasks that were most difficult for wheeled mobility device users during transit vehicle boarding and disembarking along with acceptability ratings and a ranking of design preferences for six vehicle interior layout conditions. Ramp ascent was deemed the most difficult task for manual wheelchair users, whereas tasks related to interior circulation were rated most difficult by users of power wheelchairs and scooters. Overall, the ability to independently ascend and descend on access ramps, manoeuvre in tight spaces, and perform seated reaches for fare payment were critical to successful boarding and disembarking and represent tasks that can be targets of intervention by clinicians.

Understanding the transit usability barriers, perceptions and preferences of wheeled mobility device users can help in developing, prioritizing, and implementing of evidence-based rehabilitation interventions. The study also demonstrates the utility of environmental simulations for engaging users with disabilities to identify transit usability problems in a safe and systematic manner. Such studies are extremely important to conduct prior to production of new vehicles, especially if the new vehicles take radical departures from existing models.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this manuscript were developed under grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) through the RERC on Accessible Public Transportation (RERC-APT; grant numbers #H133E130004 and #H133E080019) and a field-initiated project grant (grant number #90IF0094-01-00). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.NTD. Federal Transit Administration: National Transit Database Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation; 2017. [updated February 22; cited 2017 May 1]. Available from: https://www.transit.dot.gov/ntd/ntd-data [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross D, editor Wheelchair Access: Improvements, Standards, and Challenges. APTA Bus & Paratransit Conference; 2006; Anaheim, CA: American Public Transportation Association. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King RD. TCRP Report 41: New Designs and Operating Experiences with Low-Floor Buses: National Academy Press; 1998. Available from: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_41-a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson/Nygaard Consulting Associates. Status Report on the Use of Wheelchairs and Other Mobility Devices on Public and Private Transportation In: Nelson/Nygaard Consulting Associates, editor. Washington, DC: Easter Seals Project ACTION; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Council on Disability. The Current State of Transportation for People with Disabilities in the United States. Washington, DC: National Council on Disability; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frost KL, Bertocci GE, Sison S. Ingress/egress incidents involving wheelchair users in a fixed-route public transit environment. Journal of Public Transportation. 2010;13(4):41–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost KL, van Roosmalen L, Bertocci GE, et al. Wheeled mobility device transportation safety in fixed route and demand-responsive public transit vehicles within the United States. Assistive Technology. 2012;24(2):87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost KL, Bertocci G. Retrospective review of adverse incidents involving passengers seated in wheeled mobility devices while traveling in large accessible transit vehicles [doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.01.004]. Medical Engineering & Physics. 2010;32(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Access Board. Federal Register 36 CFR Part 1192 Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 1998. [cited 2010 February 17]. Available from: http://www.access-board.gov/transit/html/vguide.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Register 49 CFR Part 38 Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Transportation; 2007. [cited 2010 February 17]. Available from: http://www.fta.dot.gov/civilrights/ada/civil_rights_3905.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertocci G, Karg P, Hobson D. Wheeled mobility device database for transportation safety research and standards. Assistive Technology. 1997;9(2):102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinfeld E, Maisel J, Feathers D, et al. Anthropometry and Standards for Wheeled Mobility: An International Comparison. Assistive Technology. 2010. March 2010;22(1):51–67. doi: 10.1080/10400430903520280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Souza C, Steinfeld E, Paquet V, et al. Space Requirements for Wheeled Mobility Devices in Public Transportation: Analysis of Clear Floor Space Requirements [10.3141/2145–08]. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board,. 2010;No. 2145:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koontz A, Brindle E, Kankipati P, et al. Design features that impact the maneuverability of wheelchairs and scooters. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010;91:759–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King EC, Dutta T, Gorski SM, et al. Design of built environments to accommodate mobility scooter users: part II. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2011;6(5):432–439. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2010.549898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutta T, King EC, Holliday PJ, et al. Design of built environments to accommodate mobility scooter users: part I. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2011;6(1):67–76. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2010.509885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buning ME, Getchell CA, Bertocci GE, et al. Riding a bus while seated in a wheelchair: A pilot study of attitudes and behavior regarding safety practices. Assistive Technology. 2007;19(4):166–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vredenburgh AG, Zackowitz IB, editors. Research in Motion : A Case Study Evaluating the Accessibility of Public Transit in our Nation’s Capital. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 55th Annual Meeting 2011; 2011; Las Vegas, NV: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wretstrand A, Stahl A, Petzall J. Wheelchair Users and Public Transit: Eliciting Ascriptions of Comfort and Safety. Technology and Disability. 2008;20(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwarsson S, Jensen G, Stahl A. Travel Chain Enabler: Development of a pilot instrument for assessment of urban public bus transportation accessibility. Technology and Disability. 2000;12:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinfeld E, Grimble M, Paquet V, et al. Identifying Accessibility Problems in Existing Transit Systems. Paper presented at the International Conference on Mobility and Transport for Elderly and Disabled Persons (TRANSED 2012); September 17–20, 2012; New Delhi, India2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayaprakash G, D’Souza C, editors. Task Analysis Method to Modeling Wheeled Mobility User Ingress-Egress in Buses. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Mobility and Transport for Elderly and Disabled Persons (TRANSED); 2015. July; Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booz-Allen Applied Research. Human Factors Evaluation of Transbus by the Elderly. Washington, DC: Department of Transportation, Urban Mass Transportation Administration.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks BM. An Investigation Into Aspects of Bus Design and Passenger Requirements. Ergonomics. 1979;22(2):175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oxley PR, Benwell M. An Experimental Study of the Use of Buses by Elderly and Disabled People Research Report 33. Berkshire, UK: Transport and Road Research Laboratory, Department of Transport; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petzall J Ambulant disabled persons using buses: experiments with entrances and seats. Appl Ergon. 1993. October;24(5):313–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(93)90070-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.York I, Vance C, Walker R, et al. The Effects of Bus Gangway Steps on Accessibility (UPR T/106/04 - Final Report) In: Mobility and Inclusion Unit DfT, editor. London, UK: TRL Limited; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levis JA. The seated bus passenger — a review. Applied Ergonomics. 1978;9(3):143–150. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(78)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenker JA, Damle U, D’Souza C, et al. A usability evaluation of access ramps in public transit buses. Journal of Public Transportation. 2016;19(2):109–127. doi: 10.5038/2375-0901.19.2.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter-Zaworski K, Zaworski JR. Assessment of Rear Facing Wheelchair Accommodation on Bus Rapid Transit: Final report for Transit IDEA Project 38. Washington D.C.: Transportation Research Board; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaworski JR, Hunter-Zaworski KM, Baldwin M. Bus dynamics for mobility-aid securement design. Assistive Technology. 2007;19:200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Roosmalen L, Karg P, Hobson D, et al. User evaluation of three wheelchair securement systems in large accessible transit vehicles. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2011;48(7):823–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daamen W, De Boer E, De Kloe R, editors. The gap between vehicle and platform as a barrier for the disabled: An effort to empirically relate the gap size to the difficulty of bridging it. 11th International Conference on Mobility and Transport for Elderly and Disabled Persons (TRANSED); 2007; Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Transport Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daamen W, de Boer E, de Kloe R. Assessing the Gap Between Public Transport Vehicles and Platforms as a Barrier for the Disabled: Use of Laboratory Experiments. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2008;2072:pp 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daamen W, Lee Y-c, Wiggenraad P. Boarding and Alighting Experiments: Overview of Setup and Performance and Some Preliminary Results. 2008;2042:pp 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Souza C, Paquet V, Lenker JA, et al. Effects of transit bus interior configuration on performance of wheeled mobility users during simulated boarding and disembarking. Applied Ergonomics. 2017; 62(7): 94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez R, Zegers P, Weber G, et al. Influence of Platform Height, Door Width, and Fare Collection on Bus Dwell Time. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2010;No. 2143:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman JM, Murray G. TCRP Synthesis 88: Strollers, Carts, and Other Large Items on Buses and Trains. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danford GS, Steinfeld E. Measuring the Influences of Physical Environments on the Behaviors of People with Impairments In: Steinfeld E, Danford GS, editors. Enabling Environments: Measuring the Impact of Environment on Disability and Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers; 1999. p. 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinfeld E, Danford S. Measuring Handicapping Environments. Journal of Rehabilitation Outcomes Measurement. 2000;4(4):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner E, Domhof S, Langer F. Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments. New York: Wiley; 2002. (Walter AS, Wilks SS, editors. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; ). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konietschke F, Bathke AC, Hothorn LA, et al. Testing and estimation of purely nonparametric effects in repeated measures designs. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2010;54(2010):1895–1905. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noguchi K, Gel YR, Brunner E, et al. nparLD: An R software package for the nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;50(12):1–23. doi: 10.18637/jss.v050.i12.25317082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konietschke F, Hothorn LA, Brunner E. Rank-based multiple test procedures and simultaneous confidence intervals. Electronic Journal of Statistics. 2012;6(2012):738–759. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwangbo H, Kim J, Kim S, et al. Toward Universal Design in Public Transportation Systems: An Analysis of Low-Floor Bus Passenger Behavior with Video Observations. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries. 2012:1–15. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Souza C Usability and Person-Environment Interaction in Constrained Spaces: Wheeled Mobility Users and Interior Low-Floor Bus Design Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Buffalo, NY: Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering. State University of New York at Buffalo; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fitzgerald SG, Songer T, Rotko K, et al. Motor vehicle transportation use and related adverse events among persons who use wheelchairs. Assistive Technology. 2007;19:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frost KL, Bertocci G. Wheelchair securement and occupant restraint practices in large accessible transit vehicles. Proceedings of the Annual Rehabilitation Engineering Society of North America Conference; New Orleans, LA: RESNA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karg P, Buning ME, Bertocci G, et al. State of the science workshop on wheelchair transportation safety. Assistive Technology. 2009;21(3):115–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw G, Gillispie T. Appropriate protection for wheelchair riders on public transit buses. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003. Jul-Aug;40(4):309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.NHTSA. Wheelchair Users Injuries and Deaths Associated with Motor Vehicle Related Incidents In: National Center for Statistics & Analysis, editor. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), National Center for Statistics & Analysis; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pass A, Thompson K. Oversized/overweight mobility aids: Status of the issue. Washington, D.C.: Easter Seals Project ACTION; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell C, editor The size of the reference wheelchair for accessible public transport. 11th International Conference on Mobility and Transport for Elderly and Disabled Persons (TRANSED); 2007. June 18–22, 2007; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broome K, McKenna K, Fleming J, et al. Bus use and older people: A literature review applying the Person–Environment–Occupation model in macro practice. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2009;16(1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. Access Board. Draft Revisions to the ADA Accessibility Guidelines for Buses and Vans (November 19, 1998) Washington, DC: U.S. Access Board; 2008. [cited 2012 November 20]. Available from: http://www.access-board.gov/vguidedraft2.htm [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bareria P, D’Souza C, Lenker J, et al. Performance of Visually Impaired Users During Simulated Boarding and Alighting on Low-Floor Buses. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 56th Annual Meeting; Boston, MA: HFES; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.D’Souza C, Paquet V, Lenker J, et al. Low-floor bus design preferences of walking aid users during simulated boarding and alighting. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation. 2012;41(Supplement 1):4951–4956. doi: 10.3233/wor2012-0791-4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]