Abstract

Women and men exhibit differences in innate and adaptive immunity, and women are more susceptible to numerous autoimmune disorders. Two or more X chromosomes increases the risk for some autoimmune diseases, and increased expression of some X-linked immune genes is frequently observed in female lymphocytes from autoimmune patients. Evidence from mouse models of autoimmunity also supports the idea that increased expression of X-linked genes is a feature of female-biased autoimmunity. Recent studies have begun to elucidate the correlation between abnormal X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), an essential mechanism female somatic cells use to equalize X-linked gene dosage between the sexes, and autoimmunity in lymphocytes. In this review, we highlight research describing overexpression of X-linked immunity-related genes and female-biased autoimmunity in both humans and mouse models, and make connections with our recent work elucidating lymphocyte-specific mechanisms of XCI maintenance that become altered in lupus patients.

Keywords: lupus, mouse models of lupus disease, sexual dimorphism with immune disease, X-chromosome inactivation, XCI gene escape, Xist RNA

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Although biologic females and males have sexually dimorphic pairs of sex chromosomes, they must both respond to identical immunologic challenges. As a result of intrinsic genetic and hormonal differences present between the sexes, women and men diverge in their innate and adaptive immune responses. Because of these important immunologic sex differences, survival rates following infectious disease and susceptibility to developing inflammation and autoimmunity differ between females and males. In addition to the opposing effects of male and female hormones on the immune system,1–5 the second X chromosome in women also contributes to the sexual dimorphism observed in the female and male immune response. As an important contributor to autoimmunity, the presence of the second X chromosome will be the focus of this review.

The immune system combines complex and sophisticated mechanisms to distinguish foreign from self-antigens, and both innate and adaptive cells interact to coordinate antigen recognition and to maintain tolerance to self. Under particular genetic and environmental conditions, self-reactive cells can escape central and peripheral mechanisms of tolerance and mediate damage and inflammation in various tissues and orgrans.6–8 Aberrant TCRs and BCRs, which can be promoted or maintained by innate immune cells, lead to the generation of autoantibodies and immune complexes that mediate inflammation and organ damage. This pathologic response to self-antigens is linked to over 80 autoimmune disorders.8 Autoimmune diseases are clinically heterogeneous and can either be systemic or targeted against specific organs or tissues. Both environmental and genetic factors are important for the development of autoimmunity, and disease results from additive effects of several risk variants, which alone would be insufficient to cause disease. Yet, hundreds of loci have been associated with autoimmune diseases, and some of these immune gene variants are present in different diseases, suggesting that common immunoregulatory mechanisms may promote autoimmune disease.8 Many genes and pathways contribute to the breakdown of tolerance, including those that control lymphocyte activation, antigen recognition and presentation, central and peripheral tolerance, regulatory T cell (Treg) function, pattern recognition receptor sensing in innate cells, cytokine production, clearance of apoptotic debris, and many others.6,8,9 Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is one of the most prevalent autoimmune disorders with a striking 9:1 female to male bias.10 SLE is a systemic and chronic autoimmune disease affecting most of the major organs, including the kidneys, skin, brain, and joints. Some of the hallmarks of SLE include the production of antinuclear autoantibodies such as anti-dsDNA, leukopenia and other blood cell abnormalities, and the production of heightened inflammatory cytokines such as type I IFN.11–13 SLE is also characterized by periods of flares and remission, making the diagnosis and treatment of disease very difficult. Currently, the underlying genetic mechanisms and sex-linked variables contributing to heightened autoimmunity in females are poorly understood. In this review, we present evidence supporting the hypothesis that the second X chromosome in women is a critical factor that predisposes individuals to develop autoimmunity because X-linked gene dosage must be tightly regulated, and that XCI maintenance plays an important role in this process.

2 |. SEX DIFFERENCES WITH IMMUNE RESPONSES

Immune responses exhibit sexual dimorphism. On the one hand, females have an overall increase in longevity; they are capable of responding better to pathogenic challenges due to distinct sex differences in cellular and humoral immunity. Yet, the overwhelming majority of patients with some autoimmune diseases such as SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) are women. The genetic and hormonal contributions to the underlying mechanisms for these sex differences in immune responses and disease susceptibility are not well understood.

2.1 |. The female advantage with infections

Clinical and epidemiologic data suggests that there is a sexual dimorphism for human survival, as males have increased mortality rates compared to females at all stages of life.14–17 Fetal and early neonatal mortality is significantly higher in males, and some diseases including sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) are highest in the male birth fraction.15,16 There are also sex differences in survival and disease outcomes following trauma. Females have less postinjury pathology following traumatic hemorrhages, and have increased survival rates.18 Women also have a decreased incidence of postinjury pneumonia following trauma.19 In one longitudinal study, males had a 58% higher risk than females for developing major postinjury infections, including pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, and pronounced wound infection requiring surgical intervention.20

One hypothesis for the sex difference in survival rates stems from the observation that males and females respond differently to challenges from bacterial and viral pathogens. For example, there is increasing evidence that SIDS, which is increased in the male birth fraction, can be caused by bacterial infection,14 and females have a lower probability of acquiring staphylococcal infection during the first 3 wk of life.21 Furthermore, tuberculosis infection rates are twice as high in males in most countries, yet the underlying biologic mechanism for this sex difference is unknown.22 In a long-term case study of children under the age of 4, rates of viral (hepatitis, viral meningitis, measles, poliomyelitis) and bacterial infections (shigellosis, salmonella infection, diphtheria) were significantly higher in males compared to females.23 Interestingly, for children less than 1 yr of age, males were more susceptible to Campylobacter infections.24 Moreover, male and female mice orally infected with Campylobacter have different rates of colonization. One study found that postinoculation male mice had higher rates of colonization and shed more bacteria in fecal samples than female mice.24 Similarly, male mice infected with H. pylori had higher bacterial burdens than age-matched females.25

There are also sex differences with responses to viral vaccines, including influenza, yellow fever, measles mumps and rubella (MMR), hepatitis, and herpes.26–30 Following influenza vaccination, women produced higher titers of hemagglutination and generated a more robust protective antibody response compared to men. Interestingly, women also reported having more local inflammation and adverse events postvaccination, suggestive of stronger innate immune responses to vaccines.26,27 Similarly, following herpes, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B immunizations, women consistently mounted greater antibody responses than men, and reported more adverse events.26 Yellow fever vaccinations also produced more local inflammation in women, and postvaccination gene expression profiling revealed an enriched female-specific IFN signature.28

Sex differences with immune responses to pathogen infections and vaccinations may be mediated by sexual dimorphisms with numbers of immune cells. In both adults and children, women have significantly higher levels of serum IgM compared to males.17,31 A possible explanation is that healthy women have higher numbers of B cells compared to males.32 Multiple independent studies found that males have more cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and NK cells, whereas females tend to have higher percentages of CD4+ T helper cells,32–35 yet less Tregs compared to males.36 Repeated stimulation of T cells induced a strong female-specific proinflammatory gene expression profile.37 Innate immune cells also exhibit sexual dimorphism, specifically with neutrophil numbers and responses.38,39 One study reported higher levels of IFN-α expression for plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in women compared to men.40–42

2.2 |. The female bias with autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is one of the leading causes of death among middle-aged women in the United States.43 Autoimmune diseases affect 5–8% of the general population, and the majority of the around 80 known autoimmune diseases occur in women.10,44 Some autoimmune diseases such as Grave’s disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and SS occur almost exclusively in women, as estimated percentages of females with disease are as high as 88%, 95%, and 94%, respectively.43,45 The estimated female to male ratio for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is a staggering 50:1, and SS has been reported to be as high as 20:1.10,43,45 Other autoimmune diseases with a strong female prevalence include SLE, scleroderma, primary biliary cirrhosis, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, with female to male ratios of up to 9:1. Autoimmune diseases with a slight but present female bias (65–75% female) include rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and myasthenia gravis.10,43–45 It is important to note that sex ratio estimates for some autoimmune diseases, such as Addison’s disease, vary based on the population surveyed.46

3 |. THE X CHROMOSOME IN AUTOIMMUNITY

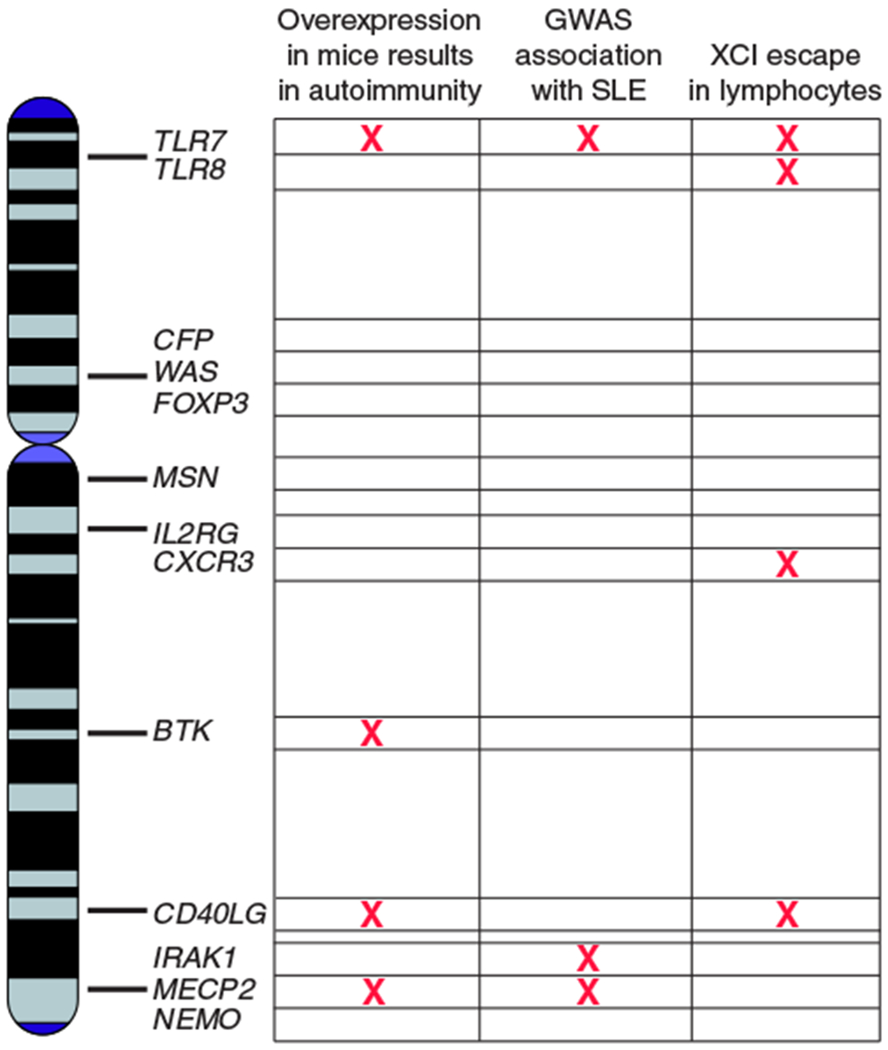

The X chromosome is home to a high density of genes with important immunoregulatory functions.47,48 Females with two X chromosomes have an increased risk for developing many autoimmune diseases (Fig. 1). Interestingly, elevated expression of certain X-linked immune-related genes is also implicated in autoimmune pathogenesis (Fig. 2), suggesting that the presence of a second X chromosome in women could be the origin of the increased expression of X-linked genes observed in autoimmunity. Thus, the regulation of X-linked genes may be an important factor for understanding the female bias with susceptibility for autoimmune disorders.

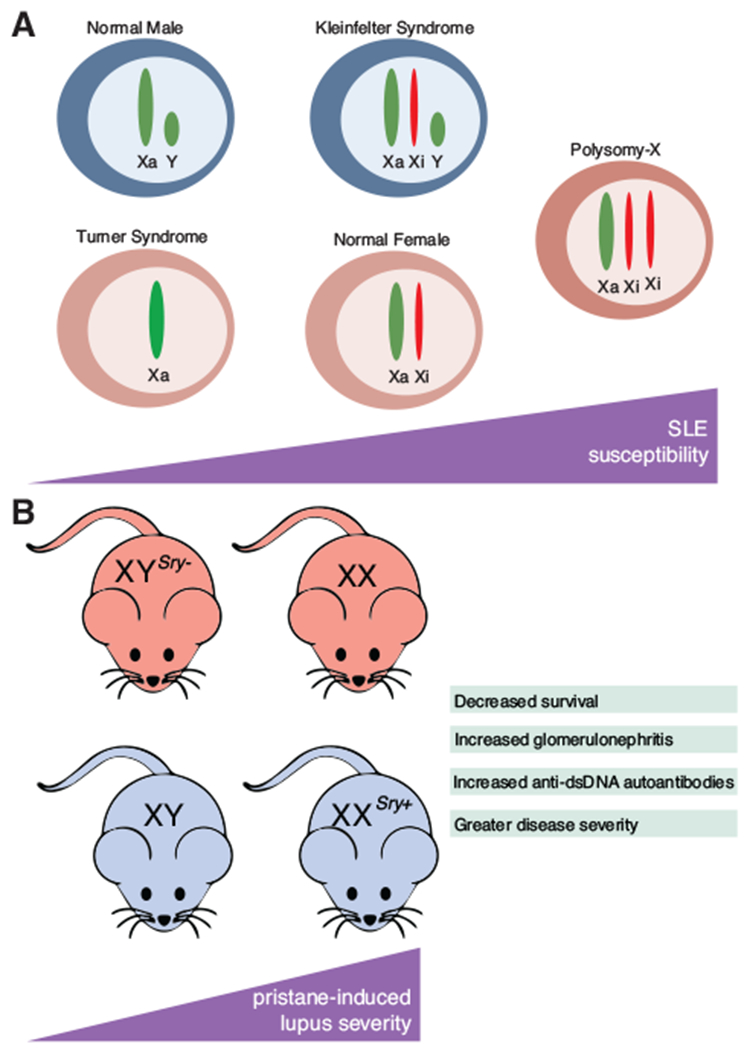

FIGURE 1. The sex chromosome complement in lupus disease.

(A) The number of X chromosomes affects susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in humans. (B) In mice, the sex chromosome complement, independent of hormones, affects severity to pristane-induced lupus

FIGURE 2.

The role of the X chromosome in humans and mice

3.1 |. Multiple X chromosomes and risk for autoimmunity

The X chromosome is an important risk factor for autoimmune susceptibility, as 46,XX females have an overall greater risk for developing autoimmunity compared to 46,XY males (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, women with Turner syndrome (45,X) who have a single X chromosome are underrepresented in cases of female SLE,49–51 supporting the hypothesis that multiple X chromosomes increases autoimmune susceptibility. Men with supernumerary X chromosomes, such as individuals with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), are predisposed toward autoimmunity similar to 46,XX females (Fig. 1A). The risk of SLE in 47,XXY males is 14-fold higher than 46,XY males with a single X chromosome.52 Men with Klinefelter syndrome also have increased risk for SS, which is also strongly female biased.53 Further, female trisomy (47,XXX) is also overrepresented in SLE as the prevalence in 47,XXX compared to karyotypically normal 46,XX women is 2.5:1. SS has a similar increased prevalence in trisomy females compared to normal females (2.9:1).54,55 SLE has also been reported in polysomy-X patients (48,XXXX).56 These studies support the hypothesis that multiple X chromosomes increases the risk for SLE or SS disease.

Important insight into the influence of multiple X chromosomes on autoimmunity has also come from murine models, and some of these models exhibit a female bias.57,58 To examine the contribution of the sex chromosomes in the absence of gonadal differences in mice, the testes-determining Sry gene was deleted, producing female XYSry− animals with ovaries within the context of male sex chromosomes. Conversely, autosomal insertion of an Sry transgene in XX animals results in testes-bearing male animals with the female sex chromosome background (XXSry+). This elegant genetic system allows for the comparison between XX and XYSry− in a female hormonal background, and XXSry+ and XY in a male hormonal background (Fig. 1B).59 One study introduced these genetic mutations into the SJL mouse strain, which exhibits female bias for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). In this model, female mice exhibited more rapid disease onset and more severe pathology compared to male animals.58 Interestingly, XX females and XXSry+ male animals had increased susceptibility for EAE.60 In this study, these mice were also injected with pristane, which results in female biased and spontaneous lupus-like disease, and these animals exhibited higher levels of inflammation,60 indicating that the two X chromosomes promoted autoimmune disease independent of hormones.

Lupus-like disease can also be induced using the hydrocarbon molecule pristane, and pristane-induced disease also exhibits a female bias. Mouse strain influences efficacy of pristane injection for autoantibody production, and treated BALB/c mice produced the highest levels of anti-ribonucleoprotein antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, and antihistone antibodies, which became deposited in the kidney.61,62 Pristane-treated mice are also characterized by elevated IFN-I and overexpression of IFN signature genes (ISG). Deletion of the IFN-I receptor in pristane-induced mouse models abolished ISG expression and eliminated anti-RNP and anti-dsDNA antibodies.63 Mice with two X chromosomes (XX and XXSry+) injected with pristane developed more severe disease compared to XY mice.60 These animals had more evidence of glomerulonephritis and had higher anti-dsDNA autoantibodies, indicating that an additional X chromosome, independent of sex-specific hormones, has an important contribution for female-biased autoimmunity (Fig. 1B).

Another classic mouse model of lupus-like disease is the NZB × NZW F1 (NZB/W F1) strain, which is generated by mating the NZB and NZW strains. Importantly these animals spontaneously develop disease resembling human SLE, where 100% of females and <40% of males develop renal disease by 1 yr.64 This mouse model is characterized by elevated anti-dsDNA and immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis, ultimately resulting in death around 10–12 mo of age. Hormones influence lupus disease, and in the NZB/W F1 model increased estrogen accelerated lupus-like disease and testosterone had protective anti-inflammatory effects in female mice; however, these results are controversial.65,66 The significance of two X chromosomes for lupus-like disease independent of endogenous hormones in NZB/W F1 mice was elegantly demonstrated using bone marrow chimera experiments. Female NZB/W F1 hematopoietic cells or female fetal liver (lacking hormone exposure) were transferred into hormonally intact lethally irradiated age-matched NZB/W F1 males, and 100% of male NZB/W F1 recipients developed lupus disease.67 Notably, chimeric mice that received female hematopoietic cells or fetal livers acquired increased numbers of germinal center B cells, memory B cells, and plasma cells. Together, these experiments suggest that X-linked gene expression in female hematopoietic cells contribute to lupus-like disease in male mice, independent of hormones.

3.2 |. X-linked gene duplication can result in autoimmunity

The duplication of certain genes on the X chromosome can result in the development of autoimmunity in mice (Fig. 2). One example is the BXSB strain, where 100% of male animals develop lupus-like disease (Table 1).68,69 The reason for the male bias was first thought to be a Y-chromosome-linked element, which was named “autoimmune accelerator” (or Yaa). Indeed, Yaa is a necessary genetic feature that results in lupus disease in male mice. In 2006, it was discovered that the Yaa element was a duplicated portion of the telomeric end of X chromosome containing 4 genes, notably the TLR gene Tlr7.70,71 Thus, male BXSB mice contain 2 copies of the X-linked Tlr7 gene, which is a pathogen recognition receptor found in antigen presenting cells and B cells that binds to single stranded RNA.72 The duplication of Tlr7gene in Yaa mice is the sole accelerator of autoimmunity, as restoring Tlr7 gene dosage back to a single copy in males using genetic deletion (Tlr7−/Yaa) rescued cumulative survival, and eliminated antinuclear autoantibody production and immune complex deposition in the kidney.73

TABLE 1.

Mouse models of X-linked gene overexpression

| Mouse name | Gene | Autoimmune phenotypes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD19-hBtk | Btk | Increase in spontaneous GC and plasma B cells, enhanced B cell activation, anti-dsDNA and antinucleosome autoantibodies, glomerulonephritis and proteinuria, peripheral perivascular inflammation | Kil et al., 2012, Corneth et al., 2016 |

| Lckgp39 | Cd40lg | Disrupted thymocyte development, lymphoid tissue hypertrophy, mononuclear cell infiltration in peripheral tissues, myeloid hyperplasia, splenomegaly, glomerulonephritis, chronic inflammatory bowel disease and lethal wasting | Clegg et al., 1997 |

| VH/IgH/IgK:CD40L | Cd40lg | antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-DNA, antihistone IgG autoantibodies, proteinuria, glomerulonephritis, in some animals | Pérez-Melgosa et al., 1999 |

| CD40Ltg+ | Cd40lg | Higher titers of high-affinity IgG and IgG1 Ab in response to T cell-dependent Ags | Higuchi et al., 2001 |

| MECP2-Tg | Mecp2 | Elevated ANAs in sera | Koelsch et al., 2013 |

| BXSB | Tr7 | Splenomegaly, lymph node enlargement, hemolytic anemia, glomerulonephritis, ANA autoantibodies, increased mortality | Andrews et al., 1978, Murphy and Roths 1979, Pisitkun et al., 2006, Subramanian et al., 2006, |

| TLR7.Tg | Tlr7 | RNA-specific antibodies, ANA autoantibodies, glomerulonephritis, splenomegaly, dendritic cell (DC) expansion, spontaneous lymphocyte activation, increased mortality | Hwang et al., 2012, Deane et al., 2007 |

The duplication of another X-linked gene, CD40LG, can also result in autoimmunity. The CD40LG gene encodes a T cell coactivation receptor (CD40LG; CD154) that is expressed on the surface of activated T cells and is important for B cell activation and proliferation. Recent work identified 2 human patients diagnosed with various autoimmune diseases that contained duplication of the CD40LG gene.74 The patients, a mother and her son, had a 240 kilobase microduplication of Xq26.3, which includes CD40LG and its regulatory elements. The mother’s autoimmune symptoms resolved about 8 yr after diagnosis, and she had evidence of skewed XCI where CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells had silenced the abnormal X chromosome containing the CD40LG duplication. However, the male patient had 2 functional copies of CD40LG, and his symptoms included high titers of antinuclear, antiribonucleoprotein, and antithyroid antibodies, T and B cell lymphopenias, splenomegaly, and autoimmune cytopenias.74 These findings indicate that human lymphocytes are sensitive to X-linked gene dosage imbalances, and that X-linked gene duplication in humans can result in autoimmunity.

3.3 |. Dosage sensitivity of X-linked genes that results in autoimmunity

3.3.1 |. Tlr7

One notable feature of SLE is elevated type I IFN and increased expression of ISG. One of the key players in the IFN-α signature is Tlr7, which is present in pDCs, B cells, and others. Tlr7 encodes for an innate pattern recognition receptor that recognizes single stranded RNA sequences in an endocytosis-dependent manner, resulting in the production of type I IFN.72,75 In the autoimmune MRL/lpr mouse model, Tlr7-deficient animals generate fewer serum autoantibodies to RNA complexes, have decreased lymphocyte activation, and ameliorated renal disease.76 The gene dosage of Tlr7 is critical in the pathogenesis of lupus, as duplication of Tlr7 in BXSB mice results in Tlr7 overexpression and lupus-like disease.70,71,73 More than 2-fold overexpression of Tlr7 alone is sufficient for the development of autoimmune phenotypes, including glomerulonephritis, antinuclear autoantibodies, and splenomegaly. DC populations also expand, and the increase in Tlr7 gene dosage stimulates autoantibody secreting B cells that result in a highly inflammatory cellular environment (Table 1).73 Another autoimmune-prone mouse model, the B6.Sle1Yaa mouse, contains the B6.Sle1 model of congenic autoimmunity with a duplication of Tlr7. In this model, increased Tlr7 expression resulted in glomerulonephritis, splenomegaly, and lymphocyte and myeloid cell abnormalities.77 Further, low copy number overexpression of Tlr7 within the B cell compartment perturbs B cell subsets and exacerbates lupus-like disease in mice containing the Sle1 lupus susceptibility locus.78 Tlr7 copy number also influences the accumulation of autoantibody secreting age-associated B cells (ABCs) in a dose-dependent fashion, as females with the highest Tlr7expression had more ABCs.79

There is also evidence of abnormal overexpression of TLR7 in human SLE patients. One study examined TLR7 levels in SLE patients under 16 yr of age,80 and more than 2 copies of TLR7 was observed in ~22% of female patients. The increase in TLR7 copy number also directly correlated to elevations with TLR7 and IFN-α mRNA.80 Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in TLR7 that influence its expression have been identified81 (Fig. 2). SLE carriers for one SNP in the 3′UTR of TLR7 had increased expression of TLR7 mRNA levels in PBMCs. Carriers also had an increased expression of type I IFN related genes, suggesting that the overexpression of TLR7 may contribute to the IFN-α signature typical in SLE disease.81

3.3.2 |. Cd40lg

The pathogenic production of autoantibodies by B cells in SLE requires help from T cells. The X-linked CD40LG/Cd40lg gene encodes for the CD40LG receptor on the surface of CD4+ T helper cells and interacts with CD40 on target cells. When CD40+ B cells engage with CD40LG, a costimulatory signal is produced that promotes survival, proliferation, class switch recombination, and germinal center formation.82 Constitutive overexpression of Cd40lg in transgenic mice leads to apoptosis-mediated thymic atrophy and subsequent chronic inflammation. Mice with high Cd40lg transgene copy numbers and gene expression developed lethal inflammation and glomerulopathy mediated by IgG deposition (Table 1).83 In another transgenic model of Cd40lg overexpression, where Cd40lg was 1.1- to 2-fold greater than litter-mate controls, Cd40lg transgenic animals developed higher titers of IgG antibodies in response to T cell-dependent antigens (Table 1).84 Interestingly, in BXSB mice, Cd40lg is ectopically expressed on B cells and can promote intrinsic B cell hyperactivity.85 A subsequent study observed that mice ectopically expressing Cd40lg on B cells spontaneously produced autoantibodies and developed immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis with age (Table 1).86

The ectopic expression of CD40LG on the surface of B cells has also been observed in human SLE patients. Surprisingly, B cells from SLE patients with active disease had a 20.5-fold increase in CD40LG expression, whereas patients in remission had similar levels of CD40LG mRNA as healthy controls. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from SLE patients also had over 20-fold increase of CD40LG expression.87 Indeed, baseline expression of CD40LG was increased in SLE patient PBMCs compared to healthy controls.88 In patients with a duplication of the CD40LG gene, expression of CD40LG was 2-fold higher than in unaffected relatives.74 Importantly, this study found that normalizing CD40LG expression using pharmacologic intervention decreased both splenomegaly and autoimmune pathologies in the patient, obviating the need for blood transfusions.74

Intriguingly, CD40LG expression exhibits sexual dimorphism in female and male SLE patients.89,90 Increased CD40LG mRNA levels were found in CD4+ T cells from female but not male SLE patients. This elevation in CD40LG expression correlated with an increase in promoter demethylation of CD40LG in women with SLE, suggesting that the demethylation of the CD40LG promoter region, most likely on the inactive X, may contribute to the female-specific overexpression of CD40LG protein.89 Together, mouse and human data support the hypothesis that the level of CD40LG/Cd40lg expression is critical in the development of chronic inflammation and autoimmunity, and overexpression of this immunoregulatory gene may contribute to the female predisposition for autoimmunity.

3.3.3 |. Cxcr3

The clinical manifestations of SLE are very heterogeneous, and one feature is renal damage. Immune complexes become deposited in the kidneys along with massive recruitment of inflammatory cells. Notably, infiltrating T cells result in renal tissue damage and loss of function. The X-linked Cxcr3 protein is a receptor involved in the chemotaxis of immune cells to areas of inflammation, and is found mainly on activated T cells.91 During inflammatory disease, Cxcr3 is highly expressed in infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which facilitates the attraction of these cells to local sites of inflammation by Cxcr3-activating chemokines.92 Lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice deficient for Cxcr3 have a reduction in glomerular tissue damage and effector T cell infiltration, demonstrating a beneficial effect of Cxcr3 deficiency for lupus-like disease.93,94

Increased CXCR3 expression is also a feature of human SLE. In SLE patient renal biopsies, ~60% of infiltrating T cells expressed CXCR3, and CXCR3+ cells were detected in the urine of SLE patients with lupus nephritis.95 Additionally, in SLE patients with renal involvement, there was elevated presence of CXCR3 at the cell surface in patients compared to healthy controls.96 Importantly, in one study examining CD4+ T cells from men and women with SLE, CXCR3 mRNA and protein levels were both increased in female but not male samples. In females with increasing disease activity, the authors noted elevated CXCR3 mRNA and demethylation of the CXCR3 promoter region compared to healthy female controls,90 suggesting that increased expression may arise from the inactive X chromosome. Together, these findings suggest that the overexpression of the X-linked Cxcr3 gene may be an important mediator of SLE in women.

3.3.4 |. Ogt

Ogt is an X-linked gene that functions as a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the addition of the posttranslational O-GlcNAc modification for regulating important cellular processes. OGT is required for T and B cell activation, as lower OGT levels reduces expression of the cell surface marker CD69, a hallmark of lymphocyte activation. In contrast, Ogt overexpression in B cells from mice increases CD69 surface externalization and led to enhanced activation through increased O-GlcNAcylation of BCR-dependent downstream transcription factors.97 It is unknown how sustained overexpression of Ogt affects lymphocyte activity in vivo, but Ogt deletion in the murine B cell lineage impaired B cell homeostasis, activation, and antibody production.98 Interestingly, CD4+ T cells from women with SLE expressed higher levels of OGT mRNA and protein than CD4+ T cells from male SLE patients, and the OGT promoter was hypomethylated in a female-specific fashion.90 Although little emphasis has been placed on the role of OGT in autoimmunity, it is tempting to speculate that overexpression of OGT might contribute to the sustained lymphocyte activation typical of SLE.

3.3.5 |. Foxp3

Tregs are a subset of CD4+ T cells that help maintain tolerance to self by suppressing the activity of autoreactive lymphocytes and reducing inflammation. Constitutive expression of the X-linked transcription factor FOXP3 is critical for establishing and maintaining Treg identity and function. As FOXP3 expression is required for the suppressive functions in Tregs, deletion or reduction of FOXP3 leads to severe and often fatal immunopathologies in both mice and humans.99–101 Reports on the numbers and functions of FOXP3-expressing cells in SLE are still contradictory. In mice, transgenic overexpression of Foxp3 is protective against renal dysfunction.102 However, in SLE patients, increased disease severity is associated with higher numbers of CD4+ FOXP3+ T cells, which may be a response to increased T cell activation in SLE.103 The efficiency of these cells may be compromised in SLE because another study reported that Tregs from patients with active SLE had reduced levels of FOXP3 mRNA and protein.104 FOXP3 is also expressed in CD8+ T cells, NKT cells, macrophages, and B cells, and higher expression has been reported in several autoimmune diseases.99 In multiple sclerosis, B cells expressing FOXP3 were increased in patients with active inflammatory disease.105 In a cohort of SLE patients, an expansion of FOXP3+ regulatory B cells was positivity correlated with disease severity.106 Future studies will be critical to determine how expression levels of FOXP3 contribute to SLE susceptibility and disease severity, the functional significance of FOXP3 expression in regulatory B cells, and whether FOXP3 plays a role in the sexual dimorphism of autoimmunity.

3.3.6 |. Btk

The X-linked Btk gene is an essential signaling component of the BCR. BTK activation in B cells initiates a signaling cascade promoting proliferation, activation, and survival. SLE is a disease often characterized by excessive B cell activity, which results in increased production of cytokines and autoantibodies that elevate inflammation and cause organ damage.107 Specific Btk inhibitor treatment of NZB/W F1 mice ameliorated lupus-like disease by reversing the accumulation of germinal center and plasma B cells and lowering anti-dsDNA autoantibodies levels.108,109 Improved glomerular pathology and function were also observed after Btk inhibition.108,109 In an inducible model of lupus nephritis, Btk inhibition decreased complement deposition in the kidneys and reduced inflammatory cytokine production.110 Similar to the other X-linked genes described above, transgenic mice overexpressing Btk in the B cell lineage developed lupus-like disease which resembled human SLE (Table 1). Btk overexpression resulted in increased numbers of plasma B cells, germinal center B cells, and the production of antinuclear autoantibodies and immune complex deposition in the kidneys.111,112 Btk overexpression has also been observed in PBMCs from human SLE patients with active lupus nephritis.113 Thus, abnormal Btk expression is another example where altered dosage of an X-linked gene is associated with lupus-like disease in mouse and human models.

3.3.7 |. Mecp2/Irak1

SNPs in the MECP2/IRAK1 locus on Xq28 have been associated with risk for developing SLE (Fig. 2).114–119 Because IRAK1 and MECP2 are located less than 2 kilobases apart, it has been challenging to parse out which of the 2 genes are affected by the SNPs. Both genes are likely candidates for increasing SLE susceptibility because IRAK1 is a mediator of NF-kB activation in immune cells, and MECP2 is a DNA binding protein and epigenetic regulator of methylation-sensitive target genes. Genetic deletion of Irak1 in lupus-prone mouse strains ameliorated lupus-like disease, with reductions in autoantibody production, lymphocyte activation, and renal disease.119 Furthermore, overexpression of a human MECP2 transgene in mice resulted in antinuclear autoantibody production (Table 1).120 Additional evidence for the contribution of MECP2 overexpression to autoimmune susceptibility comes from human patients with an MECP2 duplication. These patients have immunologic abnormalities including decreased memory B and T cells, and increased innate immune cells in blood, which is suggestive of potential inflammatory disease mediated by an increase in X-linked gene dosage.121

SLE patients have coding and noncoding SNPs in MECP2/IRAK1 locus, which affects their expression and those of neighboring genes. One IRAK1 variant resulted in increased NF-kB transcriptional activity, which may increase SLE development or disease severity.115 An additional 5 SNPs were detected across the IRAK1 locus, which may affect IRAK1 levels in SLE patients. To determine the contribution of IRAK1 and MECP2 for SLE disease, T cells from SLE patients with IRAK1/MECP2 risk alleles were profiled for expression of these two X-linked genes.120 Although IRAK1 expression was unchanged, expression of the MECP2B isoform was significantly higher in activated T cells from SLE patients containing the risk allele, compared to individuals with the nonrisk haplotype.120 Thus, SNP variants in the IRAK1/MECP2 locus can affect the expression levels of these genes in SLE patients.

4 |. X-CHROMOSOME INACTIVATION (XCI)

Although females have two X chromosomes, gene expression from the second X chromosome is transcriptionally silenced by XCI to equalize the expression levels of X-linked genes between the sexes. XCI occurs during early female embryonic development, and establishes an epigenetically distinct inactive X chromosome (Xi). X-linked gene silencing on this chromosome is maintained with each cell division throughout the lifetime of female mammals. Disruption of XCI initiation, through deletion of critical regulators of this process (see below), is lethal for the female embryo because of the dosage imbalances resulting from 2 active X chromosomes.

4.1 |. XCI ensures dosage compensation of X-linked genes

Mammalian female somatic cells with two X chromosomes must silence expression from one X to equalize expression of X-linked genes between the sexes.122,123 During early preimplantation development, females randomly select one X chromosome for transcriptional silencing. XCI is initiated by expression of the long noncoding RNA Xist from the future X that will become inactivated, and Xist RNA recruits heterochromatic complexes such as polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2).124–127 Histones across the future Xi become deacetylated and H2AK119 ubiquitination marks accumulate on this chromosome128 Xist RNA and heterochromatin marks spread across the Xi in cis, and the enrichment of these modifications on the Xi can be visualized cytologically using fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence detection.129 The combination of repressive histone marks and DNA methylation establish and maintain transcriptional silencing on the Xi,130–134 which is inherited with each cell division and maintained into adulthood.

One of the essential biologic features of XCI is that once the Xi is formed during early development, the memory of allele-specific chromosome-wide silencing is maintained throughout the lifetime of the cell (Fig. 3). Continuous expression of Xist RNA, along with DNA methylation and heterochromatin marks, maintains X-linked dosage compensation.132 Inappropriate silencing of XIST in human embryonic stem cells and human induced pluripotent stem cells resulted in the loss of heterochromatin marks at the Xi and aberrant reactivation of some X-linked genes.135–137 Moreover, genetic deletion of Xist in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in mice led to a female specific and fully penetrant aggressive cancer detectable in the blood compartment, resulting in lethality.138 Female Xist CKO/+ and Xist CKO/CKO mice developed splenomegaly and exhibited hyperproliferation of all hematopoietic lineages, leading to bone marrow dysfunction and development of hematologic cancer. Importantly, reactivation of about 200 X-linked genes was observed in these animals, suggesting that Xist RNA is required to maintain XCI for dosage compensation.138

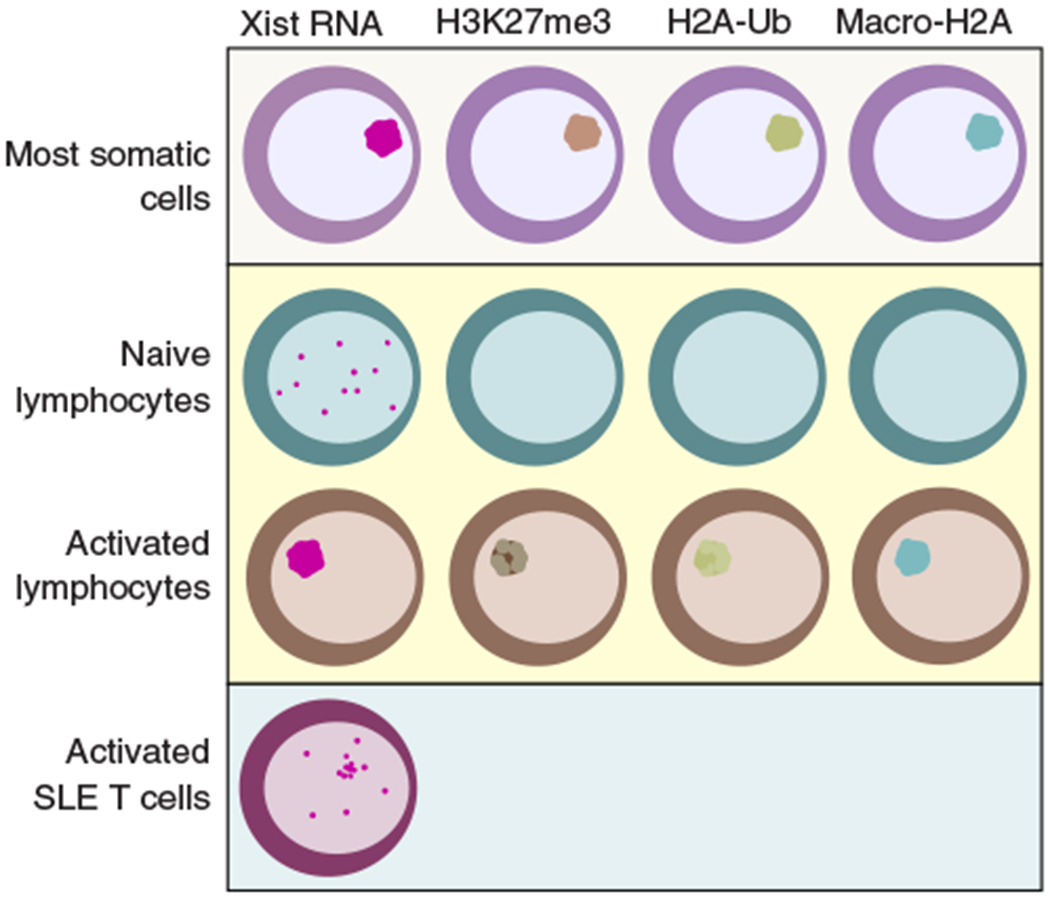

FIGURE 3. Types of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) maintenance in human and murine female cells.

Examples of nonimmune somatic cells include commonly used fibroblasts (293FT, female mouse embryonic fibroblasts, IMR-90) from mice and humans. Xist RNA is shown in red, and markers of Xi-heterochromatin are in green, brown, and blue

4.2 |. Unique XCI maintenance mechanisms in female lymphocytes

Until recently, the paradigm of XCI maintenance was that all female somatic cells preserve X-linked dosage compensation with continuous enrichment of Xist RNA and heterochromatin marks at the Xi (Fig. 3). Remarkably, female lymphocytes display a unique and dynamic form of XCI maintenance not yet described in other mature somatic cells.139,140 Mature naïve B and T cells from humans and mice lack the typical enrichment of XIST/Xist RNA transcripts and heterochromatic marks H3K27me3, H2A-ubiquitin, H4K20me, and the histone variant macroH2A at the Xi. Some of these canonic epigenetic features of XCI return back to the Xi when lymphocytes are activated (H3K27me3 and H2A-ubiquitin) and XIST/Xist RNA relocalizes to the Xi (Fig. 3). This dynamic and seemingly incomplete process of XCI maintenance in female lymphocytes raises the intriguing possibility that some genes on the Xi may be susceptible to reactivation in these cells.

Interestingly, although naïve lymphocytes lack detectible Xist RNA transcripts on the Xi, Xist RNA is continuously transcribed in female mouse and human lymphocytes, indicating that Xist transcription and localization of Xist RNA are independent processes.139,140 The Xist RNA interactome was recently defined using proteomic and forward genetic screens.141–143 Work from our lab found that 2 Xist-interacting proteins return Xist RNA and heterochromatin marks to the Xi in activated lymphocytes. Deletion or reduction of the RNA binding protein hnRNP-U and the transcription factor YY1 during lymphocyte activation prevented accumulation of Xist RNA at the Xi.139,140 We also observed that ex vivo deletion of Yy1 in murine B cells disrupted Xist RNA localization and heterochromatin enrichment at the Xi, resulting in increased expression of some X-linked immune genes.140

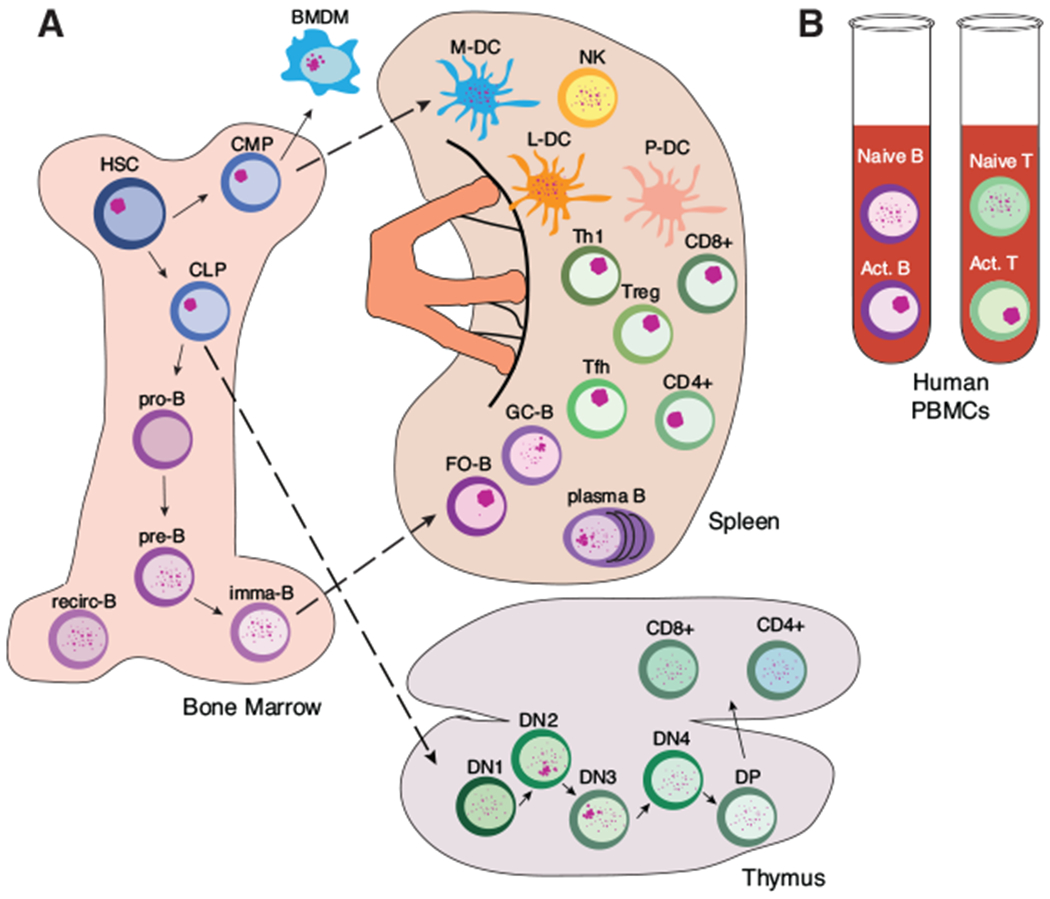

4.3 |. XCI in the female immune system

The surprising discovery that female lymphocytes have dynamic maintenance of XCI led to the provocative idea that other immune cells might also have different mechanisms for XCI maintenance. Indeed, we recently found evidence for diverse XCI maintenance in immune cells derived from both the lymphoid and myeloid lineages (Fig. 4).140,144 HSCs, common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), and common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) have Xist RNA transcripts localized to the Xi, similar to fibroblasts.140,145 However, lymphocyte progenitors, which are derived from CLPs, lacked Xist RNA localization at the Xi (Fig. 4).140,146 During B cell differentiation, Xist was continuously transcribed yet Xist RNA transcripts were never enriched at the Xi. For developing thymocytes, Xist RNA transcripts returned to the Xi in DN2-DN3cells, and then became dispersed in DP cells. The functional significance of these different patterns of Xist RNA localization during lymphocyte maturation is unknown.

FIGURE 4. Dynamic localization of Xist RNA in the female immune system.

(A) Localization patterns of Xist RNA in the female murine immune system. (B) Localization of XIST RNA from lymphocytes isolated from human PBMCs

Xist RNA was also dispersed throughout the nucleus in germinal center and plasma B cells, and occasionally clustered at the Xi, and the impact of this pattern on gene regulation of the Xi is unclear.140 Mature T cells in the spleen, including helper T cells (Th), T follicular helper cells (Tfh), and Tregs, had Xist RNA transcripts clustered at the Xi in the activated state (Fig. 4). However, NK cells, myeloid and lymphoid DCs, and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) exhibited variable and often dispersed patterns of Xist RNA throughout their nuclei.144 Xist RNA was mostly enriched at the Xi in BMDMs, and these cells also displayed enrichment of H3K27me3, similar to female fibroblasts.144 Curiously, murine plasmacytoid DCs completely lacked detectable Xist RNA in nuclei, and had few cells with Xi-enriched heterochromatin.144 The diversity with epigenetic features on the Xi among immune cells suggests that there are distinct mechanisms that maintain dosage compensation of X-linked genes, and the moleculardetails of the mechanisms responsible for transcriptional silencing are unknown.

Intriguingly, stimulated T cells from both pediatric SLE patients and the female-biased NZB/W F1 mouse model of lupus have different patterns of Xist RNA localization compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3). NZB/W F1 in vitro activated splenic CD3+ T cells during the late stage of lupus disease had less Xist RNA clustered at the Xi than healthy age-matched control females, and had a larger proportion of cells with Xist RNA dispersed throughout the nucleus.146 Xist RNA localization in circulating NZB/W F1 T cells was also different than in healthy age-matched controls. Nuclear Xist RNA clusters were detectable in circulating T cells from NZB/W F1 mice at late-stage disease compared to wild-type age-matched samples.146 Interestingly, we also observed these dispersed patterns of XIST RNA in T cells from pediatric SLE patients in disease remission.146 Importantly, we found that SLE patient T cells had abnormal overexpression of X-linked genes and perturbed expression of XIST RNA interactome genes, suggesting that altered expression of these factors might be responsible for the dispersed XIST RNA localization patterns in SLE cells.146 In sum, abnormal maintenance of XCI appears to be a feature of SLE that explains the frequent observation of overexpressed X-linked genes.

5 |. ESCAPE FROM XCI

Most genes on the inactive X chromosome in females are silenced by XCI; however, it is well established that a subset of genes can escape silencing and are normally expressed from the Xi in somatic cells. Constitutive escape from XCI is observed from the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) genes on the X and Y chromosomes; thus males and females each have 2 active copies of these genes and therefore equivalent expression.147,148 Because the majority of genes on the X chromosome are not located in PARs, they are subjected to XCI-mediated silencing.149,150 Genes that escape XCI are usually depleted for Xist RNA transcripts.151,152 Interestingly, some non-PAR genes escape from XCI, and the genes and levels of escape can be heterogeneous between individuals and in different tissues. Approximately 15% of X-linked genes are estimated to constitutively escape from XCI in humans with an additional 10% exhibiting variable escape between individuals.150,153 In mice, the Xi appears to be more silent and fewer genes constitutively escape from XCI (3–7% X-linked escape genes).154–156

Elegant studies using F1 hybrid mice with 2 distinct X chromosomes have defined tissue-specific XCI escape signatures.155,157 Because XCI is random, allele-specific techniques where XCI is genetically skewed using Xist deletion on a single X chromosome are necessary to determine the XCI status of genes on the Xi from populations of murine cells. Two elegant studies have defined tissue-specific XCI escape using F1 hybrid mice and RNA sequencing to identify genes specifically expressed from the Xi.155,157 One study determined Xi-specific expression in brain, spleen, and ovary to compare how XCI escape varies between different tissues. The authors identified tissue-specific genes with variable expression from the Xi, and other X-linked genes that constitutively escape XCI across all tissues. Notably, there were five X-linked genes that specifically escaped in spleen, and three of these genes (Cfp, Vsig4, and Bgn) have immunoregulatory functions.155 The authors also found that the promoters of these escape genes had features of active transcription, with enrichment of RNA polymerase II and DNase I hypersensitivity sites. Yet the critical factor that prevents spreading of heterochromatic marks to these active genes could be increased occupancy of the insulator CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) at these regions.155

5.1 |. Escape from XCI in immune cells

XCI is a female-specific mechanism to equalize gene expression between the sexes, presumably resulting in equal levels of expression of X-linked immune genes between female and male cells. Abnormal tissue-specific XCI escape in immune cells is one possible mechanism that would account for the overexpression of X-linked immune genes in females with SLE, and may contribute to the female autoimmune predisposition. Interestingly, we found that human naïve T cells from healthy individuals lacked XIST RNA enrichment at the Xi and had a subset of cells with biallelic expression of CXCR3 or CD40LG,139 2 genes that are subject to XCI in all cells examined to date and therefore should only be expressed from a single allele (Fig. 2).153 Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) hinted that naïve human female B cells had regions on the X chromosome with higher expression than in male cells, although these analyses were not allele specific.139 Thus, the chromatin of the Xi in healthy female lymphocytes may be prone to selective gene activation.

In addition to CXCR3 and CD40LG in T cells, evidence suggests that other X-linked genes may escape XCI in the female immune system. In a lupus prone mouse model, the X-linked gene Tlr8 was biallelically expressed in a subset of BMDMs, supporting the hypothesis that inefficient silencing of Tlr8 in females contributes to SLE susceptibility (Fig. 2).158 In human SLE patients, single-cell expression analyses revealed that TLR7 escaped from XCI in subsets of B cells, monocytes, and pDCs (Fig. 2).159 Further analysis of these cells in 47,XXY males with Klinefelter syndrome demonstrated that TLR7 also escaped from XCI in males with two X chromosomes. Importantly, B cells with TLR7 escape had increased levels of TLR7 expression and protein compared to monoallelic cells, and these biallelic cells had heightened responsiveness to TLR7 ligands. Interestingly, cells with TLR7 escape were also more efficient at class switch recombination during naïve B cell differentiation.159 Another study also reported that Tlr7 was biallelically expressed in a subset of murine female pDCs.144 In sum, recent findings support the hypothesis that dynamic XCI maintenance and immune cell specific XCI escape contributes to immune cell sexual dimorphism, and these mechanisms may be responsible for the female disposition toward autoimmunity.

6 |. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The immune system balances innate and adaptive immune responses to fight a variety of pathogens while ensuring that these pathways remain unresponsive to self. Sexual dimorphism exists for both innate and adaptive immune responses. Whereas women can mount stronger responses to certain bacterial and viral pathogens and have increased survival rates overall, they also are strongly predisposed toward developing autoimmune diseases such as SLE. The X chromosome is home to many important immune genes and the number of X chromosomes an individual possesses affects the risk for developing autoimmunity (Fig. 1). The genetic influence of two X chromosomes on immune function and autoimmune susceptibility is an important factor that influences the sex bias, yet the mechanism responsible for the increased risk for disease is still unclear.

There are various examples where X-linked gene overexpression results in the development of autoimmunity phenotypes (Fig. 2), and restoration of appropriate dosage levels eliminates disease. Given the size of the X chromosome and the enrichment for immunity-related genes, it is likely that additional X-linked genes beyond those reviewed here may be sensitive to dosage imbalances in lymphocytes and contribute to development of autoimmunity. Because there are more genes that escape XCI in humans compared to mice, it is possible that humans may be more sensitive to gene expression changes compared to mice. The transcriptional levels from the Xi for a particular escape gene can vary from 20% to 75% of the amount expressed from the Xa, for both mice and humans.160 Dosage imbalance sensitivity may also exhibit variability among X-linked genes, where housekeeping genes may be more tolerated compared to genes critical for lymphocyte function.

Recent work from our lab has shed new light on the diversity of XCI maintenance mechanisms in the immune system. Female mature naive lymphocytes lack Xist RNA and enrichment of heterochromatic marks on the Xi, unlike other somatic cells, and these modifications return to the chromosome upon stimulation. This unique dynamic mechanism where epigenetic modifications are missing from the Xi then return upon antigen stimulation suggests that the Xi in lymphocytes may be more prone to partial reactivation at certain regions or for certain genes. It is also possible that the process of localization of these epigenetic modifications, mediated by YY1, hnRNP-U, and likely other Xist interactome proteins, could become altered in SLE. At present, it is still unknown what cell extrinsic signals might influence the localization of these epigenetic modifications to the Xi, and how this would influence disease susceptibility or severity. Incomplete or delayed relocalization of Xist RNA and heterochromatin marks to the X in lymphocytes, which likely affects transcriptional silencing of the Xi provides a molecular mechanism that may explain why having multiple X chromosomes increases risk for autoimmunity. However, the biological reason for this relaxed form of XCI maintenance in the female mammalian immune system is unclear. It is interesting to speculate that immune cells benefit from increased dosage of certain X-linked genes, and that each type of immune cell would have a specific set of X-linked genes exhibiting sex-biased expression. We have begun to unravel the mechanisms of XCI maintenance in the immune system, which have revealed a plethora of exciting and important questions to investigate in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (F31-GM123604 to C.M.S; R21-AI124084 and R01-AI134834 to M.C.A.) and DOD grant (LR170055: W81XWH-18-1-0635). We thank the members of the Anguera lab for valuable discussions, brainstorming sessions about figures, and for feedback.

Abbreviations:

- ABC

Age-associated B cell

- ANA

Antinuclear antibody

- BMDM

Bone marrow-derived macrophage

- CLP

Common lymphoid progenitor

- DC

Dendritic cell

- DN

Double negative T cell

- DP

Double positive T cell

- dsDNA

Double-stranded DNA

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cell

- MMR

Measles mumps and rubella

- PAR

Pseudoautosomal region

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- SIDS

Sudden infant death syndrome

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SS

Sjögren’s syndrome

- Tfh

T follicular helper cell

- Th

Helper T cell

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- XCI

X-chromosome inactivation

- Yaa

Y-linked autoimmune accelerator

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lahita RG. The role of sex hormones in lupus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman LS. Sex hormones and the genesis of autoimmunity. Arch Dermatol. 2002;142:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards M, Dai R, Ahmed SA . Our environment shapes us: the impor tance of environment and sex differences in regulation of autoantibody production. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markle JG, Fish EN. SeXX matters in immunity. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrack P, Kappler J, Kotzin BL. Autoimmune disease: why and where it occurs. Nat Med. 2001;7:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlomchik MJ, Craft J, Mamula MJ. From T to B and back again: positive feedback in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theofilopoulos AN, Kono DH, Baccala R. The multiple pathways to autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:716–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Genetics of autoimmune diseases – disorders of immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:917–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleicher N, Barad DH. Gender as risk factor for autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2007;28:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moulton VR, Suarez-Fueyo A, Meidan E, et al. Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: a cellular perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:615–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsokos GC, Lo MS, Reis PC, et al. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:716–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohan C, Putterman C. Genetics and pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JA, Harrison LM. Hypothesis: increased male mortality caused by infection is due to a decrease in heterozygous loci as a result of a single X chromosome. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillen MM. Differential mortality by sex in fetal and neonatal deaths. Science (80-). 1979;204:89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mage DT, Donner M. A genetic basis for the sudden infant death syndrome sex ratio. Med Hypotheses. 1997;48:137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purtilo DT, Sullivan JL. Immunological bases for superior survival of females. Am J Dis Child. 1975;133:1251–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhry MA, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Gender and susceptibility to sepsis following trauma. Endocrine, Metab Immune Disord–Drug Targets. 2006;6:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gannon CJ, Pasquale M, Tracy JK, et al. Male gender is associated with increased risk for postinjury pneumonia. Shock. 2004;21:410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Offner PJ, Moore EE, Biffl WL. Male gender is a risk factor for major infections after surgery. Arch Surg. 1999;134:935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson DJ, Gezon HM, Rogers KD, et al. Excess risk of staphylococcal infection and disease in newborn males. Am J Epidemiol. 1966;84:314–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neyrolles O, Quintana-Murci L. Sexual inequality in tuberculosis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green MS. The male predominance in the incidence of infectious diseases in children: a. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strachan NJC, Watson RO, Novik V, et al. Sexual dimorphism in campylobacteriosis. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;136:1492–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebischer T, Laforsch S, Hurwitz R, et al. Immunity against Helicobacter pylori: significance of interleukin-4 receptor α chain status and gender of infected mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:556–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein SL, Jedlicka A, Pekosz A. The Xs and Y of immune responses to viral vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:338–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furman D, Hejblum BP, Simon N, et al. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaucher D, Therrien R, Kettaf N, et al. Yellow fever vaccine induces integrated multilineage and polyfunctional immune responses. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3119–3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domínguez A, Plans P, Costa J, et al. Seroprevalence of measles, rubella, and mumps antibodies in Catalonia, Spain: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook IF. Sexual dimorphism of humoral immunity with human vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26:3551–3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterworth M, McClellan B, Allansmith M. Influence of sex on immunoglobulin levels. Nature. 1967:44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdullah M, Chai PS, Chong MY, et al. Gender effect on in vitro lymphocyte subset levels of healthy individuals. Cell Immunol. 2012;272:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee BW, Yap HK, Chew FT, et al. Age- and sex-related changes in lymphocyte subpopulations of healthy Asian subjects: from birth to adulthood. Commun Clin Cytom. 1996;26:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisse IM, Aaby P, Whittle H, et al. T-lymphocyte subsets in West African children: impact of age, sex, and season. J Pediatr. 1997;130:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uppal SS, Verma S, Dhot PS. Normal values of CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte subsets in healthy indian adults and the effects of sex, age, ethnicity, and smoking. Cytometry. 2003;52B:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Afshan G, Afzal N, Qureshi S. CD4+CD25hiregulatory T cells in healthy males and females mediate gender difference in the prevalence of autoimmune diseases. Clin Lab. 2012;58:567–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewagama A, Patel D, Yarlagadda S, et al. Stronger inflammatory/cytotoxic T-cell response in women identified by microarray analysis. Genes Immun. 2009;10:509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bain BJ. Ethnic and sex differences in the total and differential white cell count and platelet count. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:664–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer JA. Gender differences in some host defense mechanisms. Lupus. 1999;8:380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berghofer B, Frommer T, Haley G, et al. TLR7 Ligands induce higher IFN-production in females. J Immunol. 2006;177:2088–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torcia MG, Nencioni L, Clemente AM, et al. Sex differences in the response to viral infections: tLR8andTLR9 ligand stimulation induce higher IL10 production in males. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griesbeck M, Ziegler S, Laffont S, et al. Sex differences in plasmacytoid dendritic cell levels of IRF5 drive higher IFN-production in women. J Immunol. 2015;195:5327–5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper GS, Stroehla BC. The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Libert C, Dejager L, Pinheiro I. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, et al. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Gender-specific incidence of autoimmune diseases from national registers. J Autoimmun. 2016;69:102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross MT, Grafham D V, Coffey AJ, et al. The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome. Nature. 2005;434:325–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bianchi I, Lleo A, Gershwin ME, et al. The X chromosome and immune associated genes. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:J187–J192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooney CM, Bruner GR,Aberle T, et al. 46,X,del(X)(q13) Turner’s syndrome women with systemic lupus erythematosus in a pedigree multiplex for SLE. Genes Immun. 2009;10:478–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sawalha AH, Harley JB, Scofield RH. Autoimmunity and Klinefelter’s syndrome: when men have two X chromosomes. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Oertelt-Prigione S, et al. X monosomy in female systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1110:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scofield RH, Bruner GR, Namjou B, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY) in male systemic lupus erythematosus patients: support for the notion of a gene-dose effect from the X chromosome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2511–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris VM, Sharma R, Cavett J, et al. Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY) is in excess among men with Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2016;168:25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu K, Kurien BT, Zimmerman SL, et al. X chromosome dose and sex bias in autoimmune diseases: increased prevalence of 47,XXX in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1290–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma R, Harris VM, Cavett J, et al. Rare X chromosome abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2187–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slae M, Heshin-Bekenstein M, Simckes A, et al. Female polysomy-X and systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:777–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voskuhl RR, Pitchekian-Halabi H, MacKenzie-Graham A, et al. Gender differences in autoimmune demyelination in the mouse: implications for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:724–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Vries GJ, Rissman EF, Simerly RB, et al. A model system for study of sex chromosome effects on sexually dimorphic neural and behavioral traits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9005–9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith-bouvier DL, Divekar AA, Sasidhar M, et al. A role for sex chromosome complement in the female bias in autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1099–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reeves WH, Lee PY,Weinstein JS, et al. Induction of autoimmunity by pristaneand other naturally occurring hydrocarbons. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freitas EC, De Oliveira MS, Monticielo OA. Pristane-induced lupus: considerations on this experimental model. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2403–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nacionales DC, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Lee PY, et al. Deficiency of the type I interferon receptor protects mice from experimental lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3770–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perry D, Sang A, Yin Y, et al. Murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roubinian JR, Talal N, Greenspan JS, et al. Effect of castration and sex hormone treatment on survival, anti-nucleic acid antibodies, and glomerulonephritis in NZB/NZW F1 mice. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1568–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verheul HAM, Verveld M, Hoefakker S, et al. Effects of ethinylestradiol on the course of spontaneous autoimmune disease in NZB/wand nod mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1995;17:163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.David A, Trigunaite A, MacLeod MK, et al. Intrinsic autoimmune capacities of hematopoietic cells from female New Zealand hybrid mice. Genes & Immun. 2014;42:115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andrews BYBS, Eisenberg RA, Argyrios N, et al. Spontaneous murine lupus-like syndromes. Clinical and immunopathological manifestations in several strains. J Exp Med. 1978;148:1198–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy ED, Roths JB. A y chromosome associated factor in strain BXSB producing accelerated autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:1188–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science (80-). 2006;312:1669–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Subramanian S, Tus K, Li Q-Z, et al. A Tlr7 translocation accelerates systemic autoimmunity in murine lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:9970–9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:5598–5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deane JA, Pisitkun P, Barrett RS, et al. Control of Toll-like receptor 7 expression is essential to restrict autoimmunity and dendritic cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;27:801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Le Coz C, Trofa M, Syrett CM, et al. CD40LG duplication-associated autoimmune disease is silenced by nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2308–2311.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vollmer J, Tluk S, Schmitz C, et al. Immune stimulation mediated by autoantigen binding sites within small nuclear RNAs involves Toll-like receptors 7 and 8. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fairhurst AM, Hwang SH, Wang A, et al. Yaa autoimmune phenotypes are conferred by overexpression of TLR7. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1971–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hwang S-H, Lee H, Yamamoto M, et al. B cell TLR7 expression drives anti-RNA autoantibody production and exacerbates disease in systemic lupus erythematosus-prone mice. J Immunol. 2012;189:5786–5796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubtsov AV, Rubtsova K, Kappler JW, et al. TLR7 drives accumulation of ABCs and autoantibody production in autoimmune-prone mice. Immunol Res. 2013;55:210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.García-Ortiz H, Velázquez-Cruz R, Espinosa-Rosales F, et al. Association of TLR7 copy number variation with susceptibility to childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Mexican population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1861–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shen N, Fu Q, Deng Y, et al. Sex-specific association of X-linked Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) with male systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:15838–15843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crow MK, Kirou KA. Regulation of CD40 ligand expression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clegg CH, Rulffes JT, Haugen HS, et al. Thymus dysfunction and chronic inflammatory disease in gp39 transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1111–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pérez-Melgosa M, Hollenbaugh D, Wilson CB. Cutting edge: cD40 ligand is a limiting factor in the humoral response to T cell-dependent antigens. J Immunol. 1999;163:1123–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blossom S, Chu EB, Weigle WO, et al. CD40 ligand expressed on B cells in the BXSB mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Imunol. 1997;159:4580–4586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Higuchi T, Aiba Y, Nomura T, et al. Cutting edge: ectopic expression of CD40 ligand on B cells induces lupus-like autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2002;168:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Desai-Mehta A, Lu L, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. Hyperexpression of CD40 ligand by Band T cells in human lupus and its role in pathogenic autoantibody production. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2063–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koshy M, Berger D, Crow MK. Increased expression of CD40 ligand on systemic lupus erythematosus lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:826–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, et al. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive XinT cellsfrom women with lupus. J Immunol. 2007;179:6352–6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hewagama A, Gorelik G, Patel D, et al. Overexpression of X-Linked genes in T cells from women with lupus. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lacotte S, Brun S, Muller S, et al. CXCR3, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Flier J, Boorsma DM, Van Beek PJ, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 targeting chemokines CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11 in different types of skin inflammation. J Pathol. 2001;194:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steinmetz OM, Turner J-E, Paust H-J, et al. CXCR3 mediates renal Th1 and Th17 immune response in murine lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2009;183:4693–4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Panzer U, Steinmetz OM, Paust H-J, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR3 mediates T cell recruitment and tissue injury in nephrotoxic nephritis in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2071–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Enghard P, Humrich JY, Rudolph B, et al. CXCR3+CD4+ T cells are enriched in inflamed kidneys and urine and provide a new biomarker for acute nephritis flares in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eriksson C, Eneslätt K, Ivanoff J, et al. Abnormal expression of chemokine receptors on T-cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12:766–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Golks A, Tran TTT, Goetschy JF, et al. Requirement for O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase in lymphocytes activation. EMBO J. 2007;26:4368–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu JL, Chiang MF, Hsu PH, et al. O-GlcNAcylation is required for B cell homeostasis and antibody responses. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1854 10.1038/s41467-017-01677-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lu L, Barbi J, Pan F. The regulation of immune tolerance by FOXP3. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:703–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Campbell DJ, Koch MA. Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lympho-proliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yang C, Huang XR, Fung E, et al. The regulatory T-cell transcription factor Foxp3 protects against crescentic glomerulonephritis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bonelli M, von Dalwigk K, Savitskaya A, et al. Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparative phenotypic analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:664–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Valencia X, Yarboro C, Illei G, et al. Deficient CD4+CD25high T regulatory cell function in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2007;178:2579–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.De Andrés C, Tejera-Alhambra M, Alonso B, et al. New regulatory CD19+CD25+B-cell subset in clinically isolated syndrome and multiple sclerosis relapse. Changes after glucocorticoids. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;270:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vadasz Z, Peri R, Eiza N, et al. The expansion of CD25highIL10highFoxP3high B regulatory cells is in association with SLE disease activity. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:254245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lipsky PE. Systemic lupus erythematosus: an autoimmune disease of B cell hyperactivity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:764–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rankin AL, Seth N, Keegan S, et al. Selective inhibition of BTK prevents murine lupus and antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. J Immunol. 2013;191:4540–4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Katewa A, Wang Y, Hackney JA, et al. Btk-specific inhibition blocks pathogenic plasma cell signatures and myeloid cell-associated damage in IFNα-driven lupus nephritis. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e90111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chalmers SA, Doerner J, Bosanac T, et al. Therapeutic blockade of immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis by highly selective inhibition of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kil LP, De Bruijn MJW, Van Nimwegen M, et al. Btk levels set the threshold for B-cell activation and negative selection of autoreactive B cells in mice. Blood. 2012;119:3744–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Corneth OBJ, de Bruijn MJW, Rip J, et al. Enhanced expression of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cells drives systemic autoimmunity by disrupting T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2016;197:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kong W, Deng W, Sun Y, et al. Increased expression of bruton’s tyrosine kinase in peripheral blood is associated with lupus nephritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kaufman KM, Zhao J, Kelly JA, et al. Fine mapping of Xq28: both MECP2 and IRAK1 contribute to risk for systemic lupus erythematosus in multiple ancestral groups. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu G, Tsuruta Y, Gao Z, et al. Variant IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 mediates increased NF-B activity. J Immunol. 2007;179:4125–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sawalha AH, Webb R, Han S, et al. Common variants within MECP2 confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One. 2008;3:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Webb R, Wren JD, Jeffries M, et al. Variants within MECP2, a key transcription regulator, are associated with increased susceptibility to lupus and differential gene expression in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1076–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yang J, et al. Meta-analysis of GWAS on two Chinese populations followed by replication identifies novel genetic variants on the X chromosome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jacob CO, Zhu J, Armstrong DL, et al. Identification of IRAK1 as a risk gene with critical role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:6256–6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Koelsch KA, Webb R, Jeffries M, et al. Functional characterization of the MECP2/IRAK1 lupus risk haplotype in human T-cells and a human MECP2 transgenic mouse. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yang T, Ramocki MB, Neul JL, et al. Overexpression of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 impairs Th1 responses. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Payer B, Lee JT.X chromosome dosage compensation: how mammals keep the balance. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:733–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lyon M Gene action in the X-chromosome of the Mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature. 1961;190:372–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brown CJ, Lafreniere RG, Powers VE, et al. Localization of the X inactivation centre on the human X chromosome in Xq13. Nature. 1991;349:82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brown C, Ballabio A, Rupert J. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;349:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Brown CJ, Hendrich BD, Rupert JL, et al. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:527–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Brockdorff N, Ashworth A, Kay GF, et al. The product of the mouse Xist gene is a 15 kb inactive X-specific transcript containing no conserved ORF and located in the nucleus. Cell. 1992;71:515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Żylicz JJ, Bousard A, Žumer K, et al. The implication of early chromatin changes in X chromosome inactivation. Cell. 2019;176:182–197.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF, et al. XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Boggs BA, Cheung P, Heard E, et al. Differentially methylated forms of histone H3 show unique association patterns with inactive human X chromosomes. Nat Genet. 2002;30:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Plath K, Fang J, Mlynarczyk-Evans S, et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in X-inactivation. Science (80-). 2003;300:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]