Abstract

Obtaining kinetic and thermodynamic information for protein amyloid formation can yield new insight into the mechanistic details of this biomedically-important process. The kinetics of the structural change that initiates the amyloid pathway, however, has been challenging to access for any amyloid protein system. Here, using the protein β−2-microglobulin (β2m) as a model, we measure the kinetics and energy barrier associated with an initial amyloidogenic structural change. Using covalent labeling and mass spectrometry, we measure the decrease in solvent accessibility of one of β2m’s Trp residues, which is buried during the initial structural change, as a way to probe the kinetics of this structural change at different temperatures and under different amyloid forming conditions. Our results provide the first-ever measure of the activation barrier for a structural change that initiates the amyloid formation pathway. The results also yield new mechanistic insight into β2m’s amyloidogenic structural change, especially the role of Pro32 isomerization in this reaction.

Graphical Abstract

The formation of protein amyloid fibrils is associated with numerous devastating human diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and type II diabetes.1,2 Amyloid fibril formation typically begins with partial protein unfolding (or partial folding by an unstructured protein) and formation of soluble oligomeric species before progressing to primary nucleation and elongation events that involve aggregate formation via the addition of monomers.1–6 For several amyloid protein systems, a combination of new experimental and theoretical tools have recently led to a greater understanding of the kinetics and thermodynamics the amyloid pathway,3–6 but almost no kinetic or thermodynamic information is available for the initial structural change for any amyloid system. Even so, it is generally recognized that measurements of kinetics and thermodynamics for amyloid systems more fully reveal the complex mechanisms involved in the process and can help better predict amyloid behavior under in vivo conditions that are more difficult to study directly.

We have sought to obtain the first-ever kinetic and energetic information about the initial structural change in amyloid formation using the protein β−2-microglobulin (β2m) as a model system. In patients with renal failure undergoing long term hemodialysis, β2m is not effectively removed, causing its concentration to increase up to 60-fold. Eventually, β2m forms amyloid fibrils in the joints of these patients.7 The cause of β2m amyloidosis is not well understood, but increased protein concentrations alone are insufficient. Several in vitro methods of inducing β2m amyloidogenesis have been established, including the addition of Cu(II), low pH, exposure to trifluoroethanol (TFE), and incubation with β2m truncation mutants, among others.8–11

Cis-trans isomerization (CTI) of Pro32 in β2m has been identified as an important structural change preceding β2m amyloid formation.12–16 In natively folded β2m, the His31-Pro32 peptide bond adopts a cis conformation stabilized by the N-terminal strand. Displacement of this strand through truncation or interactions with metals or other molecules promotes CTI of Pro32 and subsequent conversion into the amyloidogenic precursor.17 This structural change causes a repacking of the protein’s hydrophobic core, particularly exposure of Phe30 and burial of Trp60, and other structural changes that facilitate aggregation.12–16,18–22 Subsequent oligomerization to higher-order oligomers occurs before eventual amyloid fibril formation.12–16

The large change in solvent accessibility of Trp60 provides an excellent way to monitor the initial structural change that causes the conversion of the protein into the amyloidogenic precursor. Here, we use a covalent labeling (CL) mass spectrometry (MS) method22,23 to monitor the burial of Trp60 as a function of time as a means of determining the rate of β2m’s amyloidogenic switch. These rate measurements are used to determine the energy barriers associated with this structural switch under different amyloid forming conditions. Cohen et al. have recently reported energy barriers to the nucleation and elongation phases of amyloid formation by amyloid-β peptide,4 but to the best of our knowledge, our measurements represent the first energy barriers ever measured for the structural change that initiates amyloid formation. Such measurements will be useful for more deeply understanding the mechanistic details of this process.

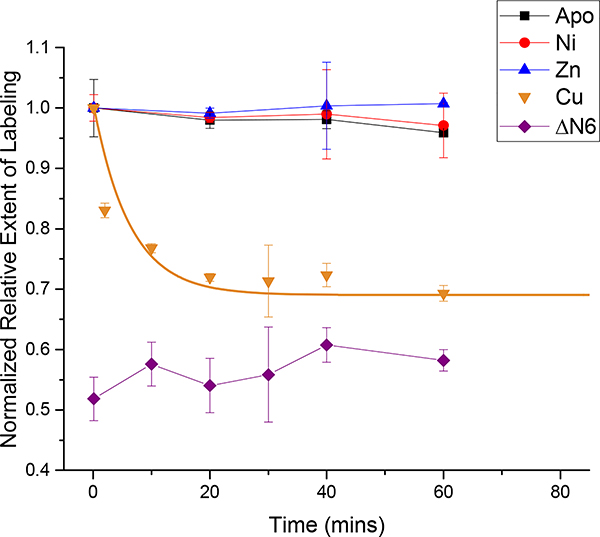

Covalent labeling MS (CL-MS) along with fluorescence spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering (DLS) were used to monitor the structural and oligomeric changes of β2m under different amyloid forming conditions. CL-MS uses reagents to covalently modify solvent accessible amino acid residues,23 with liquid chromatography MS (LC-MS) providing a readout of the extent of the modification (Figure 1 and Figure S1). The Trp- specific covalent labeling reagent dimethyl(2-hydroxy-5-nitro-benzyl) sulfonium bromide (HNSB) was used to monitor Trp60 burial over time by reacting it with β2m for 45 or 90 s at different time points after initiating amyloid formation with Cu(II), acid (at pH 3.5), or 20% TFE. The inherent reactivity of Trp with HNSB is lower at pH 3.5, and so a longer reaction time (i.e. 90 s) was used for those experiments. In all cases, the reaction is quenched by the addition of L-Trp and quickly desalted prior to MS analysis (see SI for experiment details). Intrinsic fluorescence is an unreliable indicator of Trp60 burial because β2m has more than one Trp residue and because of the quenching effects caused by acid and Cu(II). Upon adding Cu(II),19,21 the extent of β2m labeling by HNSB decreases over time before leveling off at around 30 min (Figure 2). The labeling decrease and leveling off is consistent with Trp60 being partially, but not fully, buried as Cu(II) causes the CTI of Pro32.13 β2m has two Trp residues, Trp60 and Trp95, but because Trp95 is more buried, >90% of the HNSB labeling occurs at Trp60, as determined by proteolysis and LC-MS/MS (Figure S2). Due to the low amount of labeling and lack of labeling change on Trp95, changes in total Trp labeling in the protein can be used to measure the burial of Trp60. Without Cu(II), β2m demonstrates no change in Trp60 exposure over more than 6 h. As a control, the truncated β2m species, ΔN6, which is missing the first six N-terminal residues and has a trans Pro32 and thus a more buried Trp60,17,18 was also reacted with HNSB. As expected, its reactivity is lower than wild-type β2m and does not change significantly over time (Figure 2). To ensure that metal binding itself does not affect the HNSB labeling reaction, β2m was incubated with Ni(II) and Zn(II), which do not promote amyloidogenesis.24 Trp labeling extents are similar to the metal-free protein, consistent with no Trp burial over time. Together, these data show that HNSB can be used to monitor Trp60 burial that coincides with Pro32 CTI.

Figure 1.

Experimental scheme for CL-MS of β2m using the reagent HNSB.

Figure 2.

The rate of Trp burial under different conditions as determined by HNSB Trp labeling. Cu(II) induces the structural change leading to Trp60 burial while Ni and Zn do not. ΔN6 reacts with HNSB to a lesser extent than wild-type β2m because Trp60 is more buried in that construct. Experiments were performed at 22 °C with 75 μM β2m in 25 mM MOPS and 150 mM potassium acetate at pH 7.

From a fit of the Cu(II) data in Figure 2, a Trp60 burial rate of 0.16 ± 0.06 min−1 is determined (see the SI for the equation used for fitting). This burial rate is about the same when 500 mM urea is added with Cu(II) (Figure S3). This is important as 500 mM urea is often added during β2m amyloid formation reactions to mimic uremia in dialysis patients and is known to accelerate β2m amyloid formation in vitro,8–11,21,25,26 so its small effect on the Trp60 burial rate likely indicates an effect later in the amyloidogenesis pathway. Because Trp60 burial is an essential part of the structural change, we propose that the rate of Trp60 burial is a good proxy of the rate of this amyloidogenic switch.12–16 Consistent with the idea that Trp60 burial is an indicator of the amyloidogenic structural change is the fact that thioflavin T (ThT) data indicate amyloid oligomer formation is on a time scale that is slightly longer than the decrease in Trp60 labeling upon Cu(II) addition (Figure S4). A change in ThT fluorescence is a well-known indicator of protein amyloid formation in solution,27 yet several studies have shown that ThT’s fluorescence changes as β2m oligomers form.20,28,29 β2m oligomers should form after the amyloidogenic structural change has occurred,10,12–16 and the rate of oligomer formation as revealed by ThT fluorescence (Figure S4) is 0.03 min−1 at 22°C, which, as expected, is slower than the rate of the amyloidogenic structural change in the presence of Cu(II) at 22°C.

HNSB labeling was also utilized to monitor the structural change initiated by 20% TFE (Figure S5) and acid at pH 3.5 (Figure 3).8–11,30 There are stark differences in Trp labeling profiles as compared to amyloid initiation with Cu(II). With TFE, there is a 40-min lag period before Trp labeling decreases, resulting in a Trp60 burial rate of 0.013 ± 0.003 min−1. The reason(s) for the lag period is unclear, but it is likely due to some conformational change that needs to occur before the CTI of Pro32 can proceed, as the time scale of the lag is too long to be due to TFE-related solvent effects.31–33 DLS measurements and ThT fluorescence show no oligomerization for up to 24 h after TFE addition, indicating that the structural change occurs long before aggregation. These data are the first evidence of TFE causing the β2m amyloidogenic structural change that is known to occur with Cu(II) and acid.

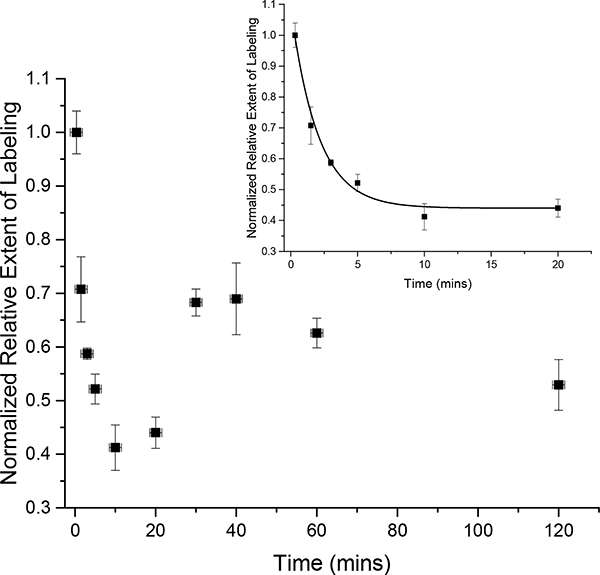

Figure 3.

HNSB labeling of β2m at pH 3.5 (citrate buffer) at 22 °C. The initial decrease is due to Trp60 burial, but the sudden increase at 30 min is due to a structural change that causes the exposure and labeling of Trp95 (see Figure S6). Data were fit from 0–20 min (inset), giving a rate of 0.49 ± 0.05 min−1.

Trp labeling has a distinct profile when amyloid formation is initiated at pH 3.5 with a sharp decrease over about 20 min before undergoing a slight increase until around 40 min when it levels off and then decreases again (Figure 3). This labeling profile is due to both structural and oligomeric changes in β2m. Proteolytic digestion followed by LC-MS/MS analyses indicate that this is a special case in which Trp60 labeling decreases steadily after the addition of acid, due to the amyloidogenic conformational change, while Trp95 labeling increases (Figure S6). Trp95 is relatively unreactive with HNSB, but over time at pH 3.5, the protein evidently unfolds to expose Trp95, leading to increased reactivity. The decrease in Trp60 labeling is on a comparable time scale with β2m oligomerization, as indicated by DLS and ThT measurements (Figure S7), again showing that Trp60 labeling probes the formation of the amyloid competent state that precedes oligomer formation. To determine the rate of the structural change, the labeling results were fit for the first 20 min, giving a rate of 0.49 ± 0.05 min−1 at 22 °C. For comparison, the oligomerization rates as indicated by ThT fluorescence and DLS changes (Figure S7) are 0.085 ± 0.001 min−1 and 0.08 ± 0.01 min−1, respectively. These measurements are consistent with oligomerization occurring after the pre-amyloid structural change.

Activation barriers for the amyloidogenic structural change were determined by measuring the Trp60 burial rates at different temperatures. As an example, Figure S8 shows a comparison of Trp labeling in the presence of Cu(II) at 22°C and 37°C. At 37°C, the structural change occurs somewhat faster (0.21 ± 0.06 min−1 vs. 0.16 ± 0.06 min−1). The Arrhenius Equation was used to determine the activation energy barrier and the preexponential factor and the Eyring Equation were used to relate the activation energy to the activation entropy of this reaction (Table 1, see SI for equations). Of the conditions tested, the structural change in the presence of Cu(II) has the lowest activation energy and preexponential factor. The addition of urea with Cu(II) has little effect on the activation energy. In the presence of 20% TFE, the activation energy is higher and the frequency factor is several orders of magnitude higher. Despite acid causing the highest rate of Trp60 burial at 37 °C, the determined energy barrier is the highest of the three conditions. The high frequency factor associated with the structural change at pH 3.5 explains the apparent disconnect. Clearly, the acid-induced amyloidogenic structural change is very sensitive to temperature. Indeed, at 37 °C in acid, visual evidence for the formation of amyloid fibrils occurs within a week, but at 4 °C in acid, no fibrils are observed for over a year.

Table 1.

Rates of Trp60 burial, activation energy barriers (Ea), pre-exponential factors (A), and activation entropies (ΔS) for each amyloid formation condition.

| Condition | Temp (°C) | Rate (min−1) | Ea (kJ/mol) | Log(A) (min−1) | ΔS (J/K·mol)ǂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) | 37 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 15 ± 2 | 1.78 ± 0.02 | −185.0 ± 0.4 |

| 22 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | ||||

| 12 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | ||||

| Cu(II) w/Urea | 37 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 0.846 ± 0.006 | −202.9 ± 0.3 |

| 22 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | ||||

| 12 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | ||||

| TFE | 37 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 57 ± 3 | 8.18 ± 0.02 | −62.8 ± 0.4 |

| 30* | 0.03 ± 0.01 | ||||

| 22** | 0.013 ± 0.003 | ||||

| Acid | 37 | 5 ± 2 | 120 ± 10 | 21.3 ± 0.1 | 188 ± 2 |

| 30 | 2 ± 1 | ||||

| 22 | 0.49 ± 0.05 |

A lag of ∼10 mins is seen prior to Trp60 burial.

A lag of ∼40 mins is seen prior to Trp60 burial.

The Eyring equation was used to relate Ea and ΔS (see SI for details).

CTIs of Pro residues have energy barriers typically ranging between 60 and 100 kJ/mol in peptides and refolding proteins, depending on sequence and other effects.34–37 His residues on the N-terminal side of Pro residues, as is the case in β2m, usually reduce Pro CTI barriers,38 which likely means the barrier of wild-type β2m is lower than average. Our measurements indicate that Cu(II) binding leads to an energy barrier for the β2m pre-amyloid structural change that is much lower than typical CTI values for Pro, suggesting that Cu(II) binding reduces the Pro32 CTI barrier substantially. Metal cations are known to catalyze Pro CTI.39,40 Cu(II) binding at His31 in β2m19,41,42 presumably accelerates CTI at His31-Pro32 because the measured barrier for the conformational change is quite low. Given the low measured barrier, His31-Pro32 CTI is likely the rate-determining step for the pre-amyloid structural change in the presence of Cu(II). The measured energy barrier with TFE is slightly below typical Pro CTI barriers, suggesting that TFE may be influencing the Pro32 CTI barrier to a small extent. Hydrogen bonds donated by solvents are known to stabilize both the cis and trans isomers of Pro, increasing the barrier to isomerization.43 The disrupted hydrogen bonding caused by TFE may have the opposite effect, destabilizing both isomers and lowering the barrier to Pro32 CTI.

Interestingly, the measured barrier at pH 3.5 is much higher than the typical Pro CTI activation barriers, even though acid is known to decrease Pro CTI barriers, particularly in cases where His precedes the prolyl bond.38 This high barrier for the amyloidogenic structural change suggests that His31-Pro32 CTI is not the rate-determining step for the pre-amyloid structural change in the presence of acid. Very likely another conformational change must occur in addition to His31-Pro32 CTI for β2m to proceed to form amyloids at pH 3.5. Acidic conditions also give a significantly higher preexponential factor than the other conditions, which is likely due to the protein rapidly fluctuating between several partially structured and unfolded states,44 leading to increased conformational heterogeneity and an increased statistical probability of adopting the higher energy transition state. In contrast, the preexponential factor with Cu(II) is much lower, which can be rationalized by the tight transition state that is almost certainly imposed by Cu(II) coordination to the N-terminal amine, the Ile1-Gln2 backbone amide, His31, and Asp59,19,40 which span a significant portion of the protein sequence. It is remarkable that β2m is capable of forming amyloid fibrils under conditions that have such distinct effects on the structure of the monomer.

To our knowledge, the results described here represent the first-ever measurements of energetic barriers for the structural change that initiates protein amyloid formation. These measurements yield new biochemical insight, specifically for β2m. Such measurements have great potential for further elucidating the mechanistic details of β2m amyloid formation. In future work, we will measure the activation barriers for various mutants of β2m as a means of revealing the specific structural features that control the pre-amyloid structural change. One could also envision using the Trp labeling reaction to screen for molecules that prevent the pre-amyloid structural change. More generally speaking, because protein amyloidosis is typically triggered by large structural changes, CL-MS should be useful for measuring unfolding barriers for other amyloid systems where the burial or exposure of specific residues can be monitored over time to yield kinetic and energetic information.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lizz Bartlett of the University of Massachusetts Biophysical Characterization Facility and Dr. Steve Eyles of the University of Massachusetts Mass Spectrometry Center for their assistance with instrumentation. We would also like to thank Dr. Robert Vass for helping with the protein expression. This work was supported by the NIH grant R01 GM 075092.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures, proteolytic digestion with LC-MS/MS data, additional Trp labeling profiles, ThT fluorescence, and DLS data are included in the supporting information. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

REFERENCES

- (1).Rochet J; Lansbury PTJ Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2000, 10, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chiti F; Dobson CM Protein Misfolding, Functional Amyloid, and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2006, 75, 333–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cohen SIA; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Knowles TPJ From macroscopic measurements to microscopic mechanisms of protein aggregation. J. Mol. Biol 2012, 421, 160–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Cohen SIA; Cukalevski R; Michaels TCT; Šarić A; Törnquist M; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Buell AK; Knowles TPJ; Linse S Distinct thermodynamic signatures of oligomer generation in the aggregation of the amyloid-β peptide. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 523–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hellstrand E; Boland B; Walsh DM; Linse S Amyloid β-protein aggregation produces highly reproducible kinetic data and occurs by a two-phase process. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2010, 1, 13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cohen SIA; Vendruscolo M; Welland ME; Dobson CM; Terentjev EM; Knowles TPJ Nucleated polymerization with secondary pathways. I. Time evolution of the principal moments. J. Chem. Phys 2011, 135, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gejyo F; Odani S; Yamada T; Honma N; Saito H; Suzuki Y; Nakagawa Y; Kobayashi H; Maruyama Y; Hirasawa Y et al. β2-microglobulin: a new form of amyloid protein associated with chronic hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1986, 30, 385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Morgan CJ; Gelfand M; Atreya C; Miranker AD Kidney dialysis-associated amyloidosis: a molecular role for copper in fiber formation. J. Mol. Biol 2001, 309, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).McParland VJ; Kad NM; Kalverda AP; Brown A; Kirwin-Jones P; Hunter MG; Sunde M; Radford SE Partially Unfolded States of β2-Microglobulin and Amyloid Formation in Vitro. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8735–8746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Eichner T; Kalverda AP; Thompson GS; Homans SW; Radford SE Conformational Conversion during Amyloid Formation at Atomic Resolution. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Stoppini M; Bellotti V Systemic amyloidosis: Lessons from β2-microglobulin. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 9951–9958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jahn TR; Parker MJ; Homans SW; Radford SE Amyloid formation under physiological conditions proceeds via a native-like folding intermediate. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2006, 13, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Eakin CM; Berman AJ; Miranker AD A native to amyloidogenic transition regulated by a backbone trigger. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2006, 13, 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Eichner T; Radford SE A Generic Mechanism of β2-Microglobulin Amyloid Assembly at Neutral pH Involving a Specific Proline Switch. J. Mol. Biol 2009, 386, 1312–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Torbeev VY; Hilvert D Both the cis-trans equilibrium and isomerization dynamics of a single proline amide modulate β2-microglobulin amyloid assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, 20051–20056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Esposito G; Ricagno S; Corazza A; Rennella E; Gümral D; Mimmi MC; Betto E; Pucillo CEM; Fogolari F; Viglino P; Raimondi S; Giorgetti S; Bolognesi B; Merlini G; Stoppini M; Bolognesi M; Bellotti V The Controlling Roles of Trp60 and Trp95 in β2-Microglobulin Function, Folding and Amyloid Aggregation Properties. J. Mol. Biol 2008, 378, 887–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Esposito G; Michelutti R; Verdone G; Viglino P; Hernández H; Robinson CV; Amoresano A; Dal Piaz F; Monti M; Pucci P; Mangione P; Stoppini M; Merlini G; Ferri G; Bellotti V Removal of the N-terminal hexapeptide from human β2-microglobulin facilitates protein aggregation and fibril formation. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 831–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cornwell O; Radford SE; Ashcroft AE; Ault JR Comparing Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange and Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins: a Structural Characterisation of Wild-Type and ΔN6 β2-Microglobulin. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2018, 29, 2413–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Srikanth R; Mendoza VL; Bridgewater JD; Zhang G; Vachet RW Copper Binding to β−2-Microglobulin and its Pre-Amyloid Oligomers. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 9871–9881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Calabrese MF; Miranker AD “Metal binding sheds light on mechanisms of amyloid assembly” Prion 2009, 3, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Antwi K; Mahar M; Srikanth R; Olbris MR; Tyson JF; Vachet RW Cu (II) organizes β−2-microglobulin oligomers but is released upon amyloid formation. Protein Sci. 2008, 17, 748–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Mendoza VL; Vachet RW “Probing Protein Structure by Amino Acid-Specific Covalent Labeling and Mass Spectrometry,” Mass Spectrom. Rev 2009, 28, 785–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Limpikirati P; Liu T; Vachet RW Covalent labeling-mass spectrometry with non-specific reagents for studying protein structure and interactions. Methods 2018, 144, 79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dong J; Joseph CA; Borotto NB; Gill VL; Maroney MJ; Vachet RW Unique Effect of Cu(II) in the Metal-Induced Amyloid Formation of p-2-Microglobulin. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1263–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Mendoza VL; Antwi K; Barón-rodríguez MA; Blanco C; Vachet RW Structure of the Pre-amyloid Dimer of β−2-microglobulin from Covalent Labeling and Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1522–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Eakin CM; Knight JD; Morgan CJ; Gelfand MA; Miranker AD Formation of a copper specific binding site in non-native states of β−2-microglobulin. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 10646–10656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Naiki H; Higuchi K; Hosokawa M; Takeda T Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavine T. Anal. Biochem 1989, 177, 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wolfe LS; Calabrese MF; Nath A; Blaho DV; Miranker AD; Xiong Y Protein-induced photophysical changes to the amyloid indicator dye thioflavin T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107, 16863–16868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Eakin CM; Attenello FJ; Morgan CJ; Miranker AD Oligomeric assembly of native-like precursors precedes amyloid formation by β−2 microglobulin. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 7808–7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Heegaard NHH; Sen JW; Kaarsholm NC; Nissen MH Conformational Intermediate of the Amyloidogenic Protein β2- Microglobulin at Neutral pH. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 32657–32662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Takamuku T; Kumai T; Yoshida K; Otomo T; Yamaguchi T Structure and dynamics of halogenoethanol-water mixtures studied by large-angle X-ray scattering, small-angle neutron scattering, and NMR relaxation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 7667–7676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Othon CM; Kwon O-H; Lin MM; Zewail AH Solvation in protein (un)folding of melittin tetramer-monomer transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2009, 106, 12593–12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hong DP; Hoshino M; Kuboi R; Goto Y Clustering of fluorine-substituted alcohols as a factor responsible for their marked effects on proteins and peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 8427–8433. [Google Scholar]

- (34).cis-trans Isomerization in Biochemistry’; Dugave C, Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Yonezawa Y; Nakata K; Sakakura K; Takada T; Nakamura H Intra- And intermolecular interaction inducing pyramidalization on both sides of a proline dipeptide during isomerization: An ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics simulation study in explicit water. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4535–4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Craveur P; Joseph AP; Poulain P; De Brevern AG; Rebehmed J Cis-trans isomerization of omega dihedrals in proteins. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kang YK Ring Flip of Proline Residue via the Transition State with an Envelope Conformation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 5463–5465. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Reimer U; Mokdad N. El; Schutkowski M; Fischer G Intramolecular assistance of cis/trans isomerization of the histidine- proline moiety. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 13802–13808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Cox C; Ferraris D; Murthy NN; Lectka T Copper(II)-catalyzed amide isomerization: Evidence for N-coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 5332–5333. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gaggelli E; D’Amelio N; Gaggelli N; Valensin G Metal ion effects on the cis/trans isomerization equilibrium of proline in short-chain peptides: a solution NMR study. Chembiochem 2001, 2, 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Calabrese MF; Eakin CM; Wang JM; Miranker AD A regulatable switch mediates self-association in an immunoglobulin fold. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2008, 15, 965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lim J; Vachet RW Using mass spectrometry to study copper-protein binding under native and non-native conditions: β−2-microglobulin. Anal. Chem 2004, 76, 3498–3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Eberhardt ES; Loh SN; Hinck AP; Raines RT Solvent Effects on the Energetics of Prolyl Peptide Bond Isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 5437–5439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yanagi K; Sakurai K; Yoshimura Y; Konuma T; Lee YH; Sugase K; Ikegami T; Naiki H; Goto Y The monomer-seed interaction mechanism in the formation of the β2-microglobulin amyloid fibril clarified by solution NMR techniques. J. Mol. Biol 2012, 422, 390–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.