This double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluates the utility of olanzapine for treating chronic nausea/vomiting in patients with advanced cancer.

Key Points

Question

Does olanzapine decrease nausea/vomiting, independent of chemotherapy, in patients with advanced cancer?

Findings

In this small, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, olanzapine treatment demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in nausea and vomiting and was well tolerated.

Meaning

While olanzapine looks as promising as any other drug for decreasing nausea and/or vomiting in patients with advanced cancer, the small sample size begs for additional testing.

Abstract

Importance

Nausea and vomiting, unrelated to chemotherapy, can be substantial symptoms in patients with advanced cancer.

Objective

To evaluate the utility of olanzapine for treating chronic nausea/vomiting, unrelated to chemotherapy, in patients with advanced cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study is a double-line, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial conducted from July 2017 through April 2019, with analysis conducted in 2019. Eligible participants were outpatients with advanced cancer who had persistent nausea/vomiting without having had chemotherapy or radiotherapy in the prior 14 days. Chronic nausea was present for at least 1 week (worst daily nausea numeric rating scores needed to be greater than 3 on a 0-10 scale).

Interventions

Patients received olanzapine (5 mg) or a placebo, orally, daily for 7 days.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient-reported outcomes were used for study end points. Data were collected at baseline and daily for 7 more days. The primary study end point (the change in nausea numeric rating scores from baseline to the last treatment day) and the study hypothesis were both identified prior to data collection.

Results

A total of 30 patients (15 per arm) were enrolled; these included 16 women and 14 men who had a mean (range) age of 63 (39-79) years. Baseline median nausea scores, in all patients, were 9 out of 10 (range, 8-10). After 1 day and 1 week, the median nausea scores in the placebo arm were 9 out of 10 (range, 8-10) on both days, compared with the olanzapine arm scores of 2 out of 10 (range, 2-3) after day 1 and 1 out of 10 (range, 0-3) after 1 week. After 1 week of treatment, the reduction in nausea scores in the olanzapine arm was 8 points (95% CI, 7-8) higher than that of the placebo arm. The primary 2-sided end point P value was <.001. Correspondingly, patients in the olanzapine arm reported less emesis, less use of other antiemetic drugs, better appetite, less sedation, less fatigue, and better well-being. One patient, on the placebo, stopped treatment early owing to lack of perceived benefit. No patients receiving olanzapine reported excess sedation or any other adverse event.

Conclusions and Relevance

Olanzapine, at 5 mg/d, appeared to be effective in controlling nausea and emesis and in improving other symptoms and quality-of-life parameters in the study population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03137121

Introduction

Chronic nausea is a particularly distressing, multifactorial symptom reported to be present in many patients with advanced cancer. There is very limited information from randomized clinical trials evaluating effective palliative options for this problem.1,2,3,4

Case reports, small retrospectively evaluated series, and a prospective pilot exploration support that olanzapine may be effective for the relief of nausea/vomiting, unrelated to chemotherapy, in patients with advanced cancer.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 On that basis, it was hypothesized that olanzapine would be an effective treatment of chronic nausea/vomiting in patients with advanced cancer, leading to the conduct of the currently reported trial.

Methods

Adult patients with malignant disease in an advanced, incurable stage were considered for this trial. They could not have had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy during the preceding 14 days or antipsychotic medications within the previous 30 days, nor had either of these planned for the duration of the study. Each eligible patient had chronic nausea that had been present for at least 1 week (worst daily score of >3 on a 0-10 numeric rating score). All patients provided written informed consent approved by internal review boards from each participating institution, per US federal guidelines. The trial was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions (Mayo Clinic, University of Indiana, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Washington University). The trial protocol is provided in Supplement 1.

Protocol patients were randomized to receive olanzapine (5 mg/d, orally, days 1-7) or a placebo. All clinicians interacting with patients and all patients were blinded (eAppendix in Supplement 2). Patients were permitted to use alternative antiemetics (any rescue therapy as determined by the patient’s clinician) if persistent nausea and/or emesis or retching had not remitted with the assigned study treatment.

Patients had a baseline evaluation that included assessment of symptom intensity for appetite, nausea, fatigue, sedation, and pain, all measured on a numeric rating score. For each of these symptoms, patients were asked to circle the one number (0-10, from none to a substantial amount of each item) that best described the way they felt over the preceding 24 hours. The number of vomiting episodes in the preceding 24 hours was also recorded. Well-being was recorded on a 0 to 10 numeric rating score (0 indicated the worst possible; 10, best possible).

For 7 days, at approximately the same time each day, patients were asked to report the intensity of appetite, nausea, fatigue, sedation, and pain, as well as overall well-being, using numeric rating scores; additionally, they reported the number of vomiting episodes in the previous 24 hours and also reported the use of the daily dose of the study drug in a medication log and the use of any rescue medications for nausea/vomiting. To facilitate patient completion of the patient-reported outcome tools, a nurse/research coordinator contacted each patient every day to remind participants to complete study materials and to query about toxic effects.

The primary objective of this trial was to estimate the effect of olanzapine vs placebo on chronic nausea and vomiting. The selected primary end point was the change in nausea scores from baseline to the last treatment day using a numeric rating score. Nausea, appetite, fatigue, sedation, pain, and well-being numeric rating scores were summarized by median and range separately by treatment arm. The number of emesis episodes at each time point and change scores from baseline to 24 hours and to 7 days after treatment initiation were also summarized by median and range separately by treatment arm. The score changes from baseline to 7 days after treatment were compared between arms using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All provided P values are from exact 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum tests, with values less than .05 considered significant. The difference in nausea score changes and the change in the number of emesis episodes, from baseline to the last treatment day, between the 2 arms were estimated with 95% CIs using the Hodges-Lehmann method. The repeated measurements of all numeric rating score domains, doses of alternative antiemetic drugs, and vomiting over time were plotted by treatment arms. Statistical analyses were performed with R, version 3.6.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Results

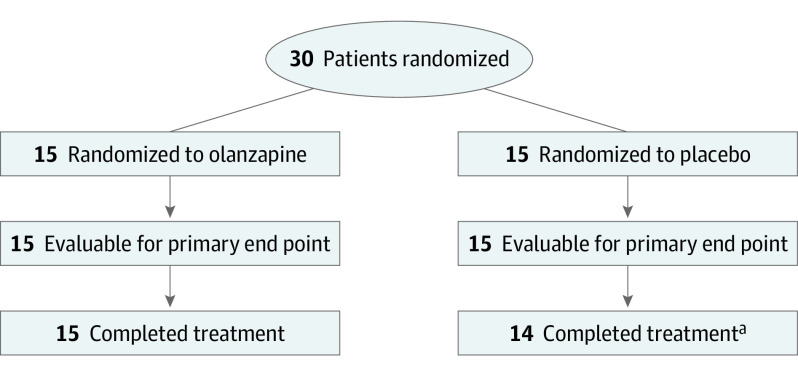

A total of 30 outpatients, 16 women and 14 men with a mean (range) age of 63 (39-79) years, were enrolled in the study from 3 institutions (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Washington University, and Indiana University) from July 2017 through April 2019. A CONSORT diagram is depicted in Figure 1. The eTable in Supplement 2 summarizes the on-study patient demographic information.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Data regarding eligibility assessment were not collected. All entered patients received the appropriate randomly assigned intervention, and no patients were lost to follow-up. All patients were included in the analyses.

aOne patient stopped the study medication on day 5 owing to nausea, which was allowed by the protocol.

One patient, who was on the placebo arm, withdrew from the study on day 5 owing to persistent nausea/vomiting. As the patient’s symptoms persisted without improvement at the time of study withdrawal, the patient’s symptom scores from the last visit were carried forward for the last 2 study days.

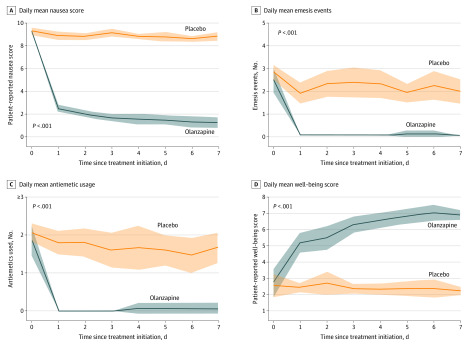

The Table provides the baseline and outcome data for this trial. Race/ethnicity information was obtained by study coordinators as part of standard procedure. Figure 2 illustrates daily data at baseline and during the study period for nausea numeric rating scores (A), the number of emesis episodes per day (B), the number of rescue antiemetic doses per day (C), and well-being numeric rating scores (D). After 1 week of treatment, the reduction in nausea scores in the olanzapine arm was 8 points (95% CI, 7-8) higher than that of the placebo arm (P < .001).

Table. Protocol-Derived Data at Baseline and for the 24 Hours After the First and Last Study Doses of Olanzapine.

| Median (range) | Difference between arms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine arm (n = 15) | Placebo arm (n = 15) | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Nausea scores (NRS): Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 9 (9 to 10) | 9 (8 to 10) | .87 | |

| Day 1 | 2 (2 to 3) | 9 (8 to 10) | ||

| Day 7 | 1 (0 to 3) | 9 (8 to 10) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | –8 (–10 to –6) | –1 (–2 to 1) | –8 (–8 to –7) | <.001 |

| Vomiting episodes/d: Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 2 (1 to 5) | 3 (2 to 4) | .19 | |

| Day1 | 0 (0 to 0) | 2 (1 to 3) | ||

| Day 7 | 0 (0 to 0) | 2 (1 to 3) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | –2 (–5 to –1) | –1 (–3 to 1) | –2 (–2 to –1) | .001 |

| Alternative antiemetic doses/d: Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 2.0 (0 to 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0 to >2.0) | NAb | |

| Day 1 | 0 (0 to 0) | 2.0 (1.0 to 2.0) | ||

| Day 7 | 0 (0 to 1.0) | 1.5 (1.0 to >2.0) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | –2.0 (–2.0 to 0) | 1.0a | NAb | NAb |

| Appetite scores (NRS): Lower daily values indicate worse quality of life in the study population. | ||||

| Baseline | 1 (1 to 2) | 1 (1 to 2) | .21 | |

| Day 1 | 5 (3 to 7) | 2 (1 to 2) | ||

| Day 7 | 7 (6 to 8) | 2 (1 to 3) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | 5 (4 to 7) | 0 (–1 to 2) | 5 (5 to 6) | <.001 |

| Fatigue scores (NRS): Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 6 (2 to 8) | 7 (3 to 8) | .18 | |

| Day 1 | 5 (3 to 6) | 7 (5 to 8) | ||

| Day 7 | 3 (2 to 6) | 7 (5 to 8) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | –3 (–4 to 4) | 0 (–1 to 2) | –3 (–4 to –1) | .004 |

| Sedation scores (NRS): Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 1 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 2) | .67 | |

| Day 1 | 1 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 3) | ||

| Day 7 | 0 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 5) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | 0 (–1 to 0) | 0 (–1 to 4) | –1 (–2 to 0) | .08 |

| Pain scores (NRS): Higher daily values indicate worse quality of life. | ||||

| Baseline | 6 (3 to 7) | 6 (5 to 7) | .63 | |

| Day 1 | 5 (3 to 7) | 6 (5 to 7) | ||

| Day 7 | 5 (3 to 7) | 6 (4 to 7) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | –1 (–2 to 1) | 0 (–3 to 1) | –1 (–2 to 0) | .01 |

| Well-being scores (NRS): Higher daily values indicate improved quality of life | ||||

| Baseline | 2 (2 to 8) | 2 (2 to 7) | .84 | |

| Day 1 | 5 (4 to 8) | 2 (2 to 3) | ||

| Day 7 | 7 (6 to 8) | 2 (2 to 3) | ||

| Change from baseline to day 7 | 4 (0 to 6) | 0 (–5 to 1) | 5 (4 to 5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not available; NRS, numeric rating score.

Range cannot be calculated because 1 patient reported >2.0 doses at baseline and also at day 7.

The CIs and P values are not available because patients were given the option of choosing >2 antiemetic doses per day, and some chose that.

Figure 2. Plots of Daily Data Over Time.

Plots with 95% CIs, regarding daily data during the study period for numeric rating score (NRS) for nausea (A), the number of emetogenic episodes per day (B), the number of rescue antiemetic doses per day (C), and NRS for well-being (D). In some plots, lower scores are better, while higher scores are better in others; in all situations, the olanzapine arm had more favorable results. The provided P values are from the Wilcoxon test in which change from baseline to day 7 was tested between arms.

When the study was completed, a question arose as to how long the perceived benefit from olanzapine might last. While the protocol was only designed as a 7-day study, at the end of the 7 days, the protocol code was broken and patients on olanzapine were allowed to receive olanzapine as a prescription medication from their attending clinician. Months after the protocol was completed, the protocol patients’ clinicians were contacted to inquire about how the patients did following study participation. The results of this inquiry revealed that all the patients on olanzapine continued on it at 5 mg/d, with continued efficacy and no toxic effects attributed to the olanzapine. Of the 14 patients who were initially receiving a placebo, all were offered olanzapine at 5 mg/d; 13 began olanzapine treatment, while 1 patient declined owing to disease progression and inability to take oral medications. All these patients reported marked efficacy and few or no toxic effects. All patients continued olanzapine for 3 to 12 weeks, with reasons for discontinuing olanzapine, in both groups, being disease progression, an inability to take oral medications, or death.

Discussion

This trial supports the prestudy hypothesis that olanzapine is effective for the treatment of chronic nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer. The magnitude of benefit observed in this trial, regarding nausea/vomiting, is in line with what has been reported in 3 other pilot reports.8,12,13

The patient-reported data support that the 5 mg daily olanzapine dose was well tolerated. The improvement in appetite is not surprising, as the appetite-enhancing properties of this drug are well known.14 With olanzapine being associated with undesired sedation in some situations,15 it is interesting to note that there was decreased sedation and improved fatigue in the olanzapine arm. Potential explanations for this are that a relatively low dose of olanzapine was given and also that patients receiving olanzapine had a decrease in the use of other antiemetic medications, which may have caused a sedating effect in the placebo arm.

Limitations

The small sample size in the current trial is clearly a study limitation. Further data regarding the utility of olanzapine for controlling nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer are welcomed.

Conclusions

The data from this trial support that olanzapine substantially decreases nausea/vomiting associated with advanced cancer and is relatively well tolerated. No other drug studied in this situation has been reported to decrease nausea/vomiting more than was observed in this study.

Clinical protocol and statistical analysis

eTable. On-study patient characteristics.

eAppendix. Online data regarding randomization.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Li Z, Palmer LJ, Bruera E. Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer. 2009;115(2):437-445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Digges M, Hussein A, Wilcock A, et al. Pharmacovigilance in hospice/palliative care: net effect of haloperidol for nausea or vomiting. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(1):37-43. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta M, Davis M, LeGrand S, Walsh D, Lagman R. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer: the Cleveland Clinic protocol. J Support Oncol. 2013;11(1):8-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruera E, Moyano JR, Sala R, et al. Dexamethasone in addition to metoclopramide for chronic nausea in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(4):381-388. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson WC, Tavernier L. Olanzapine for intractable nausea in palliative care patients. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(2):251-255. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licup N. Olanzapine for nausea and vomiting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(6):432-434. doi: 10.1177/1049909110369532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Theobald DE, et al. A retrospective chart review of the use of olanzapine for the prevention of delayed emesis in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(5):485-488. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00078-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Passik SD, Lundberg J, Kirsh KL, et al. A pilot exploration of the antiemetic activity of olanzapine for the relief of nausea in patients with advanced cancer and pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(6):526-532. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00391-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirl WF, Roth AJ. Remission of chemotherapy-induced emesis with concurrent olanzapine treatment: a case report. Psychooncology. 2000;9(1):84-87. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastava M, Brito-Dellan N, Davis MP, Leach M, Lagman R. Olanzapine as an antiemetic in refractory nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):578-582. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00143-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneishi K, Kawabata M, Morita T. Olanzapine for the relief of nausea in patients with advanced cancer and incomplete bowel obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(4):604-607. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harder S, Groenvold M, Isaksen J, et al. Antiemetic use of olanzapine in patients with advanced cancer: results from an open-label multicenter study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(8):2849-2856. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4593-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKintosh D. Olanzapine in the management of difficult to control nausea and vomiting in a palliative care population: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):87-90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navari RM, Brenner MC. Treatment of cancer-related anorexia with olanzapine and megestrol acetate: a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(8):951-956. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0739-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):134-142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical protocol and statistical analysis

eTable. On-study patient characteristics.

eAppendix. Online data regarding randomization.

Data Sharing Statement