Abstract

Precise control of Wnt signaling is necessary for immune system development. Here we detected severely impaired development of all lymphoid lineages in mice resulting from a N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mutation in limb region 1 like (Lmbr1l), encoding a membrane-spanning protein with no previously described function in immunity. Interaction of LMBR1L with glycoprotein 78 (GP78) and ubiquitin-associated domain containing 2 (UBAC2) attenuated Wnt signaling in lymphocytes by preventing the maturation of FZD6 and LRP6 through ubiquitination within the endoplasmic reticulum and by stabilizing destruction complex proteins. LMBR1L-deficient T cells exhibited hallmarks of Wnt/β-catenin activation and underwent apoptotic cell death in response to proliferative stimuli. LMBR1L has an essential function during lymphopoiesis and lymphoid activation, acting as a negative regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

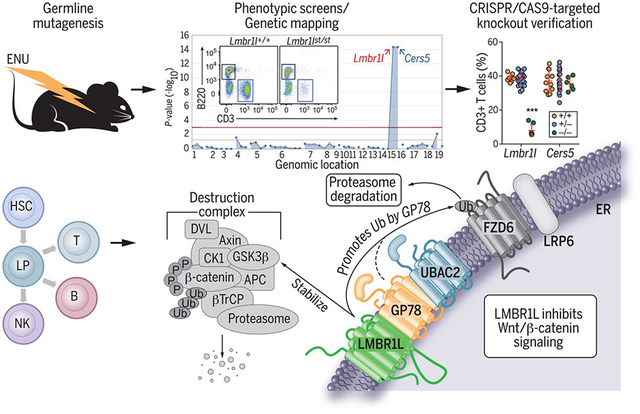

Graphical Abstract

LMBR1L plays an essential role in lymphocyte development by limiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. A mutation in Lmbr1l caused the impaired development and function of lymphocytes in a forward genetic screen of mice with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)–induced mutations. Development to the LMPP stage and all subsequent lymphoid-directed stages was impaired in LMBR1L-deficient mice. A LMBR1L-GP78-UBAC2 complex in the ER stabilizes the β-catenin destruction complex and promotes the ubiquitin (Ub)–mediated degradation of β-catenin and Wnt receptors. LP, lymphoid progenitor; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli protein; P, phosphoryl.

One Sentence Summary:

LMBR1L regulates lymphocyte development.

Structured Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a key regulator of mammalian development. In the hematopoietic system, Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes the survival and renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and the commitment to and differentiation into hematopoietic progenitor and lymphocyte lineages. However, the phenotypic effects of Wnt/β-catenin are not straightforward, in that either excessive or insufficient β-catenin activity has deleterious consequences. For example, combinations of hypomorphic or null adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) alleles resulting in a gradient of Wnt/β-catenin signaling levels cause either HSC expansion at low levels of activation or depletion of the HSC pool at high levels of activation. Other reports indicate that the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway can promote apoptosis in lymphocytes and decrease quiescence in HSCs.

RATIONALE

In a mouse forward genetic screen for mutations affecting lymphopoiesis and immunity, we identified a recessive hypomorphic mutation in the limb region 1–like gene (Lmbr1l) that resulted in reduced T cell frequencies in the blood. Further phenotypic analysis of Lmbr1l mutant mice demonstrated severely impaired development of all lymphoid lineages, compromised antibody responses to immunization, and reduced cytotoxic T lymphocyte killing activity, natural killer (NK) cell function, and resistance to mouse cytomegalovirus infection. LMBR1L-deficient T cells are predisposed to apoptosis and die in response to antigen-specific or homeostatic expansion signals. We also found impairments in the differentiation of HSCs into the lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor (LMPP) and common lymphoid progenitor populations that give rise to T cells, B cells, and NK cells. We investigated the molecular function of Lmbr1l in lymphocyte development.

RESULTS

LMBR1L contains nine transmembrane-spanning domains and, in cell fractionation experiments, was most abundant in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) fraction. LMBR1L coimmunoprecipitated with numerous components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling apparatus, including ZNRF3, LRP6, β-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase–3α (GSK-3α), and GSK-3β, and with proteins involved in ER-associated degradation (ERAD) of misfolded proteins [UBAC2, transitional ER adenosine triphosphatase (TERA), UBXD8, and glycoprotein 78 (GP78)]. Primary CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− mice displayed increased levels of β-catenin and the mature forms of Wnt receptor FZD6 and co-receptor LRP6. These effects resulted from the failure of a LMBR1L-GP78-UBAC2 complex to signal the degradation of β-catenin, FZD6, and LRP6 in the ER. Similarly increased expression of β-catenin and mature FZD6 and LRP6 was detected in Gp78−/− primary CD8+ T cells. In addition, reduced protein expression of multiple “destruction complex” components [Axin1, DVL2, β-TrCP, GSK-3α and −3β, and casein kinase 1 (CK1)] was observed in Lmbr1l−/− primary CD8+ T cells. Notably, the knockout of β-catenin in Lmbr1l−/− EL4 cells, a T lymphoma cell line, restored the proliferative potential to a substantial extent and decreased apoptosis caused by LMBR1L deficiency.

CONCLUSION

Absent LMBR1L, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is aberrantly activated, leading to impaired development and functional defects of all lymphoid lineages in mice. Perhaps because of the need for its precise regulation, a prominent element of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is the canonical destruction complex that ensures the cytoplasmic destruction of β-catenin in the absence of Wnt ligand. Our findings reveal another component of this braking system: an ER-localized LMBR1L-GP78-UBAC2 complex responsible for the degradation of FZD and LRP6 in lymphocytes. Although the upstream signal(s) directing the activation of the LMBR1L-GP78-UBAC2 complex are unknown, we hypothesize that the interface of this complex with the canonical destruction complex synchronizes the activities of these complexes and circumvents leaky inhibition by a single braking mechanism.

The hematopoietic system consists of many cell types with specialized functions. Blood cells, derived from either the lymphoid or the myeloid lineage, are generated from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). HSCs continuously replenish all blood cell classes through a series of lineage-restricted steps and balance these mechanisms to maintain steady-state hematopoiesis throughout the lifetime of the organism. In the last two decades, canonical Wnt signaling (also known as Wnt/β-catenin signaling) and non-canonical Wnt signaling (e.g. the planar cell polarity pathway and Wnt-Ca2+ signaling) have emerged as important regulators of the immune system by regulating HSC self-renewal, T and B cell development, and T cell activation (1–4). In lymphocytes, Wnt proteins function as growth-promoting factors but also affect cell-fate decisions including apoptosis and quiescence (5). Aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in T cell lineages by deletion of adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) causes T cell lymphopenia as a result of spontaneous activation and apoptosis of mature T cells in the periphery (6).

Given its widespread importance, several feedback regulatory mechanisms help to control proper Wnt signaling. These include the negative feedback regulator zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3) and its homologue ring finger 43 (RNF43) (7). These transmembrane E3 ligases specifically promote the ubiquitination of lysine residues in the cytoplasmic loops of frizzled proteins (FZD), subjecting FZD to lysosomal degradation and thereby attenuating Wnt signaling (8, 9). Recently, dishevelled (DVL) has been suggested as a critical intermediary for ZNRF3/RNF43-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of FZD (10). Loss of ZNRF3 and RNF43 expression is predicted to result in hyper-responsiveness to Wnt stimulation, and mutations in ZNRF3 and RNF43 have been observed in a variety of cancers in humans (7, 9). Despite the importance of Wnt signaling in immunity, negative feedback regulators that specifically control lymphopoiesis remain unknown. Here we describe the function and mechanism of action of LMBR1L in the negative regulation of Wnt signaling in lymphocytes.

Immunodeficiency caused by a Lmbr1l mutation

To discover non-redundant regulators of lymphopoiesis and immunity, we carried out a forward genetic screen in mice carrying N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced mutations. We identified several mice descended from a common ENU-treated founder with low percentages of CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood (inset in Fig. 1A). The phenotype, which we called strawberry (st), was transmitted as a recessive trait. By single-pedigree mapping, a method that analyzes genotype versus phenotype associations from a pedigree (11), the strawberry phenotype correlated with mutations in Lmbr1l and Cers5 (Fig. 1A). Lmbr1l encodes limb region 1 like (LMBR1L), a transmembrane protein of unknown function in immunity, and Cers5 encodes ceramide synthase 5 (CERS5), an enzyme in ceramide synthesis. The initial ambiguity concerning the causative effect of a mutation in Lmbr1l versus Cers5 was genetically resolved in favor of Lmbr1l (Fig. S1). The Lmbr1l mutation in strawberry mice results in the substitution of cysteine 212 with a premature stop (C212*) in the fifth transmembrane helix of LMBR1L (Fig. 1B). This mutation was considered a putative null allele. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted knockout mutations of both Cers5 and Lmbr1l were generated, confirming that the mutation in Lmbr1l was solely responsible for the observed phenotype (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. A heritable lymphopenia caused by LMBR1L deficiency in mice.

(A) Manhattan plot. −Log10 P-values plotted vs. the chromosomal positions of mutations identified in the affected pedigree. (insets) Representative flow cytometric plot of B220+ and CD3+ peripheral blood lymphocytes in wild-type (WT) and strawberry mice. (B) LMBR1L topology. The schematic shows the location of the Lmbr1l point mutation, which results in substitution of cysteine 212 for a premature stop codon (C212*) in the LMBR1L protein. (C-J, M, N) Frequency and surface marker expression of T (C-F), B (H-J), NK (M), and NK1.1+ T (N) cells in the peripheral blood from 12-week-old Lmbr1l−/− or Cers5−/− mice generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. (K) T cell-dependent β-gal-specific antibodies 14 days after immunization of 12-week-old Lmbr1l−/− or Cers5−/− mice with a recombinant SFV vector encoding the model antigen, β-gal (rSFV-βGal). Data presented as absorbance at 450 nm. (L) T cell-independent NP-specific antibodies 6 days after immunization of 13-week-old Lmbr1l−/− or Cers5−/− mice with NP-Ficoll. Data presented as absorbance at 450 nm. (O) Quantitative analysis of the β-gal-specific cytotoxic T cell killing response in Lmbr1l−/− mice that were immunized with rSFV-βGal. An equal mixture of ICPMYARV peptide (β-gal-specific MHC I epitope for mice with H-2d haplotype) pulsed CFSEhi and unpulsed CFSElo splenocytes were adoptively transferred to immunized mice by retro-orbital injection. Mice were bled 48 h following adoptive transfer and killing of CFSE-labeled target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (P) Lmbr1l−/− mice generate reduced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses to aluminum hydroxide precipitated ovalbumin (OVA/alum). Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type littermates were immunized with OVA/alum at day 0. Total and memory Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells were analyzed at day 14 by flow cytometry using CD44 and CD62L surface markers. (Q) NK cell cytotoxicity against MHC class I-deficient (B2m−/−) target cells in Lmbr1l−/− mice. An equal mixture of CellTrace Violet-labeled C57BL/6J (Violetlo) and B2m−/− (Violethi) cells were transferred into recipient mice and NK cell cytotoxicity toward target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry 48 h after injection. (R) Viral DNA copies in livers from Lmbr1l−/− mice 5 days after infection with 1.5 × 105 pfu MCMV Smith strain. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (C-R). P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (C-O, Q, R) or Student’s t-test (P). Data are representative of two independent experiments (C-J, M, N) or one experiment (K, L, O-R) with 5–24 mice per genotype. Error bars indicate S.D. * P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001.

To further characterize the immunological defect caused by the Lmbr1l mutation, we immunophenotyped mice by complete blood count (CBC) testing, flow cytometric analysis of blood cells, immunization and analysis of antibody responses and memory formation, in vivo NK- and CTL-mediated cytotoxicity testing, and mouse cytomegalovirus infection (Figs. 1C–R, S2–S5). The Lmbr1l−/− mice were cytopenic with reduced numbers of leukocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes (Fig. S2). Consistent with the peripheral blood cell counts, Lmbr1l−/− and strawberry mice had decreased frequencies of CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood relative to those of wild-type littermates (Figs. 1C, S3A). The CD4+-to-CD8+ T cell ratio was increased in Lmbr1l−/− and strawberry mice (Figs. 1D, S3B). The expression of surface glycoproteins CD44 and CD62L, which are abundant on expanding T cell populations, was increased (Figs. 1E, 1F, S3C, S3D). The B cell-to-T cell ratio was also increased (Figs. 1G, S3E). There was a reduction in surface B220 (Figs. 1H, S3F) and IgD (Figs. 1I, S3G) expression with a concomitant increase in IgM expression (Figs. 1J, S3H) in the peripheral blood of Lmbr1l−/− or strawberry homozygotes compared to wild-type mice. This suggests that the Lmbr1l mutation affected B cell development. The Lmbr1l−/− mice had slightly smaller thymi compared to wild-type mice (Fig. S4A). The number of double-negative (DN) thymocytes were comparable between Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type mice (Fig. S4B). However, we observed a decrease in double-positive (DP) and single-positive (SP) thymocytes in the Lmbr1l−/− mice (Fig. S4C–E). Despite comparable numbers of total splenocytes, a marked reduction in the number of all lymphocytes was observed in Lmbr1l−/− spleens compared to wild-type spleens (Fig. S4F–K). T cell-dependent and -independent humoral immune responses to recombinant Semliki Forest virus-encoded β-galactosidase (rSFV-βgal) and 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl-Ficoll (NP-Ficoll), respectively, were diminished (Figs. 1K, 1L, S3I, S3J). The antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) killing activity in immunized Lmbr1l−/− or strawberry mice was also decreased compared to wild-type littermates (Figs. 1O, S3M). The antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response to immunization with aluminum hydroxide precipitated ovalbumin (OVA) was weaker in Lmbr1l−/− mice compared to wild-type mice, as indicated by reduced total numbers (Fig. 1P) and frequencies of Kb/SIINFEKL-tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. S5) in the spleens of immunized Lmbr1l−/− mice. The frequencies and numbers of natural killer (NK; Figs. 1M, S3K, S4I) and NK1.1+ T cells (Figs. 1N, S3L, S4J) were reduced in Lmbr1l−/− or strawberry mice with a concomitant decrease in NK cell target killing (Figs. 1Q, S3N). Furthermore, the Lmbr1l−/− mice displayed susceptibility to mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) as determined by elevated viral titers in the liver (Fig. 1R) after challenge with a sublethal dose of MCMV. Lmbr1l mRNA was detected in a variety of mouse tissues and immune cells, with higher expression in the bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and lymphocytes (Fig. S6A and B). However, LMBR1L deficiency had no effect on myeloid cell development (Fig. S4N and O) or their function as determined by IFN-α, IL-1β, and TNF-α secretion in response to various stimuli (Fig. S6C–J). Thus, LMBR1L is essential for lymphopoiesis in mice.

Cell-intrinsic failure of lymphopoiesis

To determine the cellular origin of the Lmbr1l-associated defects, we reconstituted irradiated wild-type (CD45.1) or Rag2−/− (CD45.2) recipients with unmixed wild-type (Lmbr1l+/+; CD45.2) bone marrow, Lmbr1l mutant (CD45.2) bone marrow, or an equal mixture of mutant (CD45.2) and wild-type (CD45.1) bone marrow cells. In the absence or presence of competition, bone marrow cells from strawberry donors were unable to repopulate cells of lymphoid lineage such as B220+ (Fig. 2A, E), CD3+ T (Fig. 2A, F) and NK cells (Fig. 2B, G) in the spleens of irradiated recipients as efficiently as cells derived from wild-type donors. The frequency of DN cells was increased and the frequency of DP cells was decreased in the thymus of mice that received strawberry bone marrow compared to those that received bone marrow from wild-type mice (Fig. 2C, H, I), suggesting that the Lmbr1l mutation mildly affects T cell differentiation in the thymus.

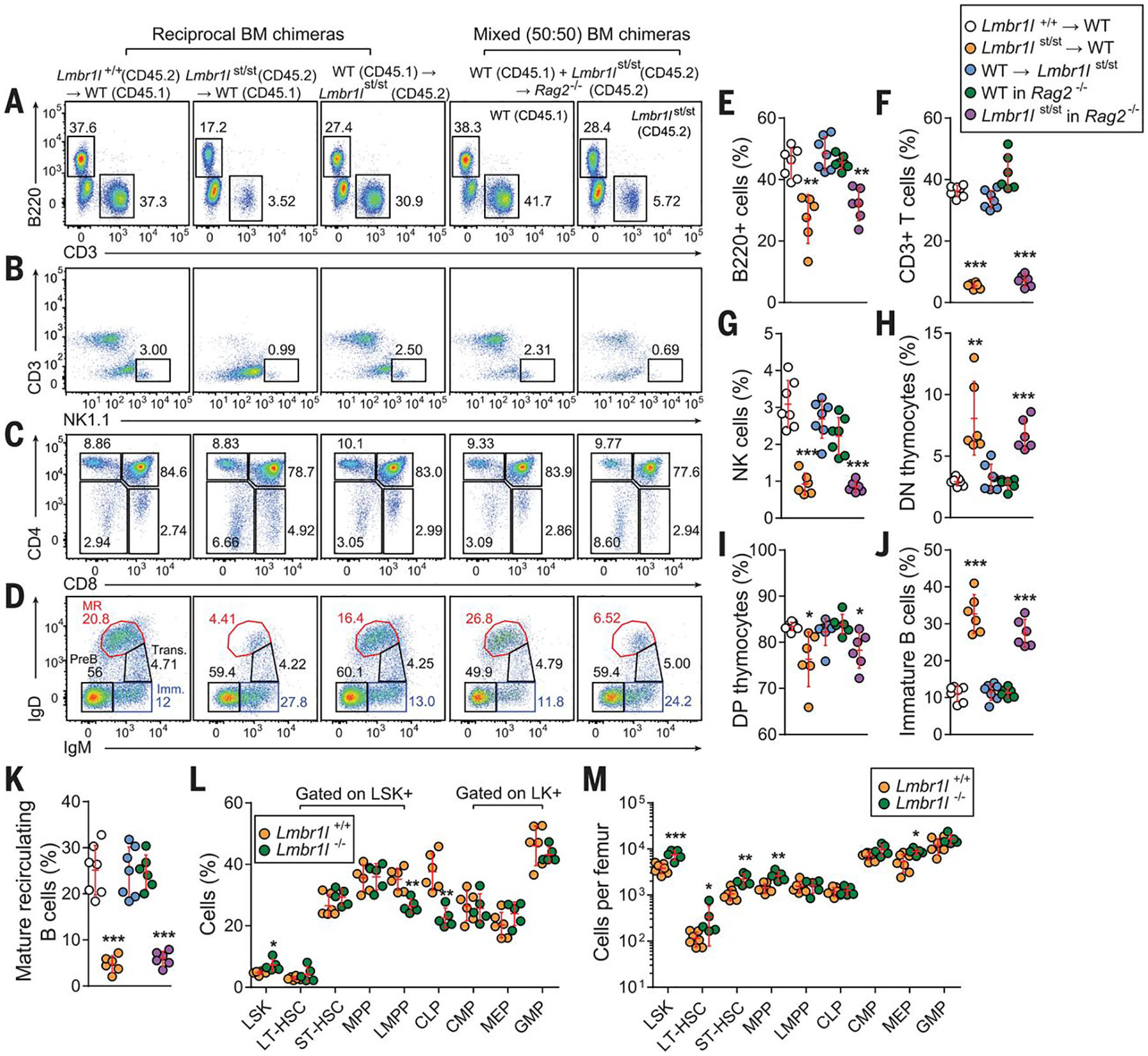

Fig. 2. A cell-intrinsic failure of lymphocyte development.

(A-D) Repopulation of lymphocytes in spleen (A, B), thymus (C), and bone marrow (D) 12 weeks after reconstitution of irradiated wild-type (C57BL/6J; CD45.1) and strawberry (CD45.2) recipients with strawberry (CD45.2) or wild-type (C57BL/6J; CD45.1) bone marrow, or Rag2−/− recipients with a 1:1 mixture of Lmbr1lst/st (CD45.2) and wild-type (C57BL/6J; CD45.1) bone marrow. Representative flow cytometric scatter plots of B and T cells (A), NK cells (B), thymocytes (C), and bone marrow B cells. MR: mature recirculating B cells, Trans.: transitional B cells, Imm.: immature B cells. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas or in quadrants (A-D) indicate percent cells in each. (A, B, E-G) Reconstitution of B (A, E), T (A, F), and NK (B, G) cells in the spleen of recipients with donor-derived cells 12 weeks after engraftment. (C, D, H-K) Repopulation of donor-derived T cell subsets in thymus (C, H, I) and B cell subsets in bone marrow (D, J, K) in recipients rescued from lethal irradiation. (L, M) The frequencies (L) and total numbers (M) of stem and progenitor cell subsets per femur in the LSK+ and LK+ compartments in the bone marrow of Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type littermates as determined by flow cytometry. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (E-M). P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (E-K) or Student’s t-test (L, M). Data are representative of two independent experiments with 6–7 mice per genotype. Error bars indicate S.D. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

In the bone marrow, immature B cells were increased among repopulated B cells derived from strawberry donors compared to those from wild-type donors (B220+IgM+IgD−; Fig. 2D, J), and very few of the B cells from strawberry donors progressed to the mature recirculating B cell stage (B220+IgM+IgD+; Fig. 2D, K). This developmental arrest occurred in both irradiated wild-type and Rag2−/− recipients regardless of competition. We also detected decreased expression of B220 and IgD, and increased expression of IgM on peripheral blood B cells from strawberry homozygotes and Lmbr1l−/− mice (Figs. 1H–J, S3F–H). Thus, Lmbr1l mutations also impair B cell development.

Lymphocytes, including B, T, and NK cells originate from lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), which are thought to develop from LMPPs. Therefore, we examined the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations in the bone marrow. LMBR1L deficiency caused an increase in the proportion and numbers of LSK+ cells compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 2L, M). The composition of the LSK compartment was mildly altered in Lmbr1l−/− bone marrow, resulting in a reduction in the proportion of LMPPs and CLPs (Fig. 2L). In contrast, the numbers of long-term-hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs), short-term (ST)-HSCs, and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) were increased in Lmbr1l−/− bone marrow compared to those from wild-type mice (Fig. 2M). LMBR1L deficiency did not appreciably affect the composition and numbers of LK+ cells, including common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), megakaryocyte–erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs), or granulocyte–macrophage progenitors (GMPs; Fig. 2L, M). Additionally, competitive bone marrow chimeras were made using a 1:1 mixture of Lmbr1l−/− (CD45.2) and wild-type (CD45.1) bone marrow to assess the relative fitness of these progenitor populations. At 8 weeks post-transplant, Lmbr1l−/−-derived hematopoietic cells were at an advantage in repopulating LSKs, ST-HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, and MEPs, while showing a disadvantage in repopulating LMPPs, CLPs, and GMPs (Fig. S7). The observed HSC phenotype in Lmbr1l−/− mice corresponds to the HSC phenotype when Wnt signaling is modestly increased in mice carrying hypomorphic Apc mutations (12). This suggests a specific effect of LMBR1L deficiency on lymphoid lineage commitment that is cell-autonomous.

Although the Lmbr1l mutation resulted in abnormal cellularity in the thymus as indicated by the increased proportion of DN cells together with decreased DP cells (Figs. 2H, I), the remaining DP cells survived thymic selection and could develop into mature SP cells (Fig. 2C). Similar to peripheral blood T cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleens of Lmbr1l−/− mice showed increased expression of the surface glycoprotein CD44, which encompasses recently activated, expanding, and memory phenotype cells (Fig. 3A). Increased CD44 expression was not evident in developing thymocytes (Fig. 3A). Immunoblot analysis of CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− mice revealed T cell factor-1 (TCF-1) and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1) downregulation, a phenotype previously observed in activated effector T cells (Fig. 3B) (13). Moreover, Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase (p44/42 MAPK), p70S6K (a mTORC1 substrate), and ribosomal protein S6 (a p70S6K substrate), which are activated through phosphorylation, were constitutively phosphorylated under basal conditions in the CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− mice (Fig. 3B). A higher percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from strawberry homozygotes were positive for annexin V under steady-state conditions compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 3C). Lower IL-7Rα expression was seen in peripheral T cells of Lmbr1l−/− mice compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 3D). Thus, peripheral T cells from Lmbr1l mutant mice appear to exist in an activated state that may be predisposed to apoptosis, which led us to investigate their proliferative response to expansion signals.

Fig. 3. LMBR1L-deficient T cells die in response to expansion signals.

(A) LMBR1L-deficient peripheral T cells are activated. Flow cytometric analysis of CD44 expression on T cells in the thymi and spleens of 12-week-old Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type littermates. (B) Immunoblot analysis of TCF1/7, LEF1, Akt, phospho-Akt, S6, phospho-S6, phospho-p70S6K, phospho-p44/p42 MAPK, and GAPDH in total cell lysates (TCLs) of pooled CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− or wild-type littermates. (C) Annexin V staining of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood obtained from 14-week-old wild-type or strawberry mice. (D) IL-7Rα expression on CD3+ T cells in peripheral blood obtained from 12-week-old Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type littermates. (E-G) Impaired antigen-specific expansion of LMBR1L-deficient T cells. A 1:1 mixture of CellTrace Violet-labeled Lmbr1l−/− (CD45.2) and Far Red-stained wild-type OT-I T cells (CD45.2) was adoptively transferred into wild-type hosts (C57BL/6J; CD45.1). Representative flow cytometric scatter plots (E) and histograms (F), and quantification of total numbers (G) of CellTrace Violet- or Far Red-positive wild-type or Lmbr1l−/− OT-I T cells harvested from the spleens of wild-type (C57BL/6J; CD45.1) hosts, 48 or 72 h after immunization with soluble OVA or sterile PBS (vehicle) as a control. (H-M) Impaired homeostatic expansion of LMBRlL-deficient T cells. An equal mixture of CellTrace Violet-labeled or CellTrace Far Red-stained pan T cells isolated from the spleen (H-J) or mature single-positive thymocytes (K-M) from Lmbr1l−/− or wild-type littermates were adoptively transferred into sublethally irradiated (8.5 Gy) wild-type hosts (C57BL/6J; CD45.1). Representative flow cytometric scatter plots (H, K) and histograms (I, L), and quantification of total numbers (J, M) of CellTrace Violet- or CellTrace Far Red-positive cells harvested from the spleens of sublethally irradiated or unirradiated wild-type hosts, 4 or 7 days after transfer. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent cells in each ± SD. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (A, C, D, G, J, M). P-values were determined by Student’s t-test (A, C, D) or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons (G, J, M). Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4–29 mice per genotype or group. Error bars indicate S.D. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

To examine antigen-specific T cell proliferation, an equal mixture of OVA-specific wild-type (CD45.2) and Lmbr1l−/− OT-I T cells (CD45.2) were transferred into wild-type recipients (CD45.1) that were subsequently immunized with soluble OVA. Wild-type OT-I T cells underwent proliferation as expected, but significantly fewer Lmbr1l−/− OT-I T cells were detected in the spleen 2 or 3 days after immunization (Fig. 3E–G). We found that an excess of the Lmbr1l−/− OT-I T cells were apoptotic, as indicated by annexin V staining (Fig. S8A). To further test the effect of the Lmbr1l mutation on T cell proliferation, we examined the response to homeostatic proliferation signals. An equal mixture of wild-type and homozygous strawberry splenic T cells was adoptively transferred into sublethally irradiated wild-type mice. Whereas wild-type T cells underwent extensive proliferation, homozygous strawberry T cells failed to proliferate in irradiated recipients (Fig. 3H–J) and showed a higher frequency of annexin V staining compared to wild-type T cells (Fig. S8B).

To address whether T cell homing to secondary lymphoid organs is impaired a mixture of wild-type and Lmbr1l−/− dye-labeled pan T cells were transferred into irradiated recipients. A significant number of wild-type and Lmbr1l−/− T cells were detected in the spleen of irradiated recipients after adoptive transfer, excluding the possibility of homing defects and further supporting that the Lmbr1l−/− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have proliferation defects (Fig. S9). These results demonstrate that Lmbr1l mutant or Lmbr1l−/− T cells undergo apoptosis in response to antigen-specific or homeostatic expansion signals. To investigate whether the activated state (CD44hi) of Lmbr1l−/− T cells predisposes them to apoptosis, we isolated mature SP thymocytes (CD44lo; Fig. 3A) and stimulated them to proliferate in response to homeostatic expansion signals. Similar to splenic T cells, mature SP thymocytes from Lmbr1l−/− mice also failed to proliferate and showed an increased percentage of apoptotic cells (Fig 3K–M, and S8C). Thus, LMBR1L-deficient T cells, regardless of activation state, die in response to expansion signals.

In the periphery, the balance between the expansion of activated (effector) T cells and their subsequent elimination during the termination of an immune response is controlled by extrinsic death receptors and caspase-dependent apoptosis, intrinsic mitochondria- and caspase-dependent apoptosis, or caspase-independent cell death. Treatment of either wild-type or Lmbr1l mutant CD8+ T cells with ligands for extrinsic death receptors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α or Fas ligand (FasL) enhanced proteolytic processing of caspases of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway (e.g., caspase-8, −3, −7 and PARP). Levels of cleaved caspases were increased in Lmbr1l mutant T cells relative to wild-type T cells (Fig. S10A, B). Moreover, excessive cleavage of caspase-9, a key player in the intrinsic pathway, was detected in Lmbr1l−/− cells after treatment with extrinsic apoptosis inducers (Fig. S10A, B). Thus, both extrinsic and intrinsic caspase cascades appear to play roles in LMBR1L-deficient T cell apoptosis. Notably, deficiency of TNF-α (Fig. S10C), Fas (Fig. S10D), or caspase-3 (Fig. S10E) failed to rescue the T cell deficiency in Lmbr1l−/− mice. Neither Fas-, TNFR-, nor caspase-3-mediated apoptosis pathways were solely responsible for the death of Lmbr1l−/− T cells.

Identification of LMBR1L as a negative regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling

LMBR1L was first identified as a receptor for human lipocalin-1 (LCN1), an extracellular scavenger/carrier of lipophilic compounds that mediates ligand internalization and degradation (14–18). Later findings suggested that LMBR1L mediates internalization of bovine lipocalin β-lactoglobulin (BLG) (19), a major food-borne allergen in humans, and that LMBR1L interacts with uteroglobin (UG), which has anti-chemotactic properties (20). We generated mice carrying a targeted null allele of Lcn3, the mouse orthologue of human LCN1, and observed that LCN3-deficient mice were overtly normal and did not exhibit lymphocyte development defects. Thus, the function of LMBR1L in lymphopoiesis is independent of its interaction with LCN3 (Fig. S11).

We sought to understand the immune function of LMBRL1 by identifying LMBR1L-interacting proteins using co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) combined with mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Among the 1,623 candidate proteins identified as putative LMBR1L interactors (Dataset S1), 25 proteins were >50-fold more abundant in the LMBR1L co-IP product relative to empty vector control (Table 1). Four of the proteins were essential components of the ERAD pathway, including ubiquitin associated domain containing 2 (UBAC2; elevated 297-fold), transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase (TERA known as VCP; elevated 120-fold), UBX domain-containing protein 8 (UBXD8, known as FAF2; elevated 71-fold) (21), and glycoprotein 78 (GP78; known as AMFR; elevated 51-fold). We also identified numerous components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that were among 764 proteins found exclusively in the LMBR1L co-IP, including zinc and ring finger 3 (ZNRF3), low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), β-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase-3α (GSK3α), and GSK3β. We also performed protein microarray analysis as a second unbiased approach to identify LMBR1L–interacting proteins. GSK-3β ranked eighth out of 9,483 human proteins for binding affinity to LMBR1L (Fig. 4A, Dataset S2). LMBR1L showed binding affinity for casein kinase 1 (CK1) isoforms including CK1α, γ, δ, and ε, as well as for β-catenin. To confirm the interactions between LMBR1L and components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling or ERAD pathways, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HA-tagged LMBR1L and FLAG-tagged GSK-3β, β-catenin, ZNRF3, ring finger 43 (RNF43, a homologue of ZNRF3 with redundant function in Wnt receptor processing), FZD6, LRP6, or DVL2. LMBR1L co-immunoprecipitated with each of the FLAG-tagged proteins (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, co-IP and immunoblot analysis confirmed that LMBR1L interacts with each of the ERAD components including UBAC2, UBXD8, VCP, and GP78 (Fig. S12). Thus, LMBR1L may be a critical component of the Wnt/β-catenin and ERAD signaling pathways.

Table. 1.

LMBR1L-interacting proteins identified by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) combined with mass spectrometry (MS) analysis that were increased more than 50-fold, or Wnt components exclusively present in the LMBR1L co-IP relative to empty vector control.

| Protein | Description | PSMs | Peptide Seqs. | % Coverage | Ratio h-LMBR1L/h-vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8NBM4 | UBAC2 | 43 | 10 | 30.8 | 297.46 |

| Q9Y5M8 | SRPRB | 28 | 15 | 57.6 | 231.28 |

| Q9UHB9 | SRP68 | 9 | 7 | 16.8 | 197.80 |

| Q14697 | GANAB | 29 | 15 | 18.4 | 197.57 |

| F5GZJ1 | NCAPD2 | 21 | 15 | 14.7 | 168.60 |

| P55072 | VCP (TERA) | 78 | 34 | 44.7 | 120.13 |

| P04843 | RPN1 | 31 | 19 | 29.0 | 118.15 |

| Q14C86 | GAPVD1 | 16 | 8 | 8.1 | 110.42 |

| P53621 | COPA | 22 | 20 | 16.8 | 110.02 |

| O43678 | NDUFA2 | 4 | 3 | 41.4 | 107.10 |

| J3KR24 | IARS | 15 | 10 | 10.4 | 106.07 |

| B9A067 | IMMT | 23 | 20 | 30.3 | 99.95 |

| Q96SK2 | TMEM209 | 13 | 10 | 31.4 | 97.83 |

| Q14318–2 | FKBP8 | 14 | 10 | 26.9 | 87.63 |

| H3BS72 | PTPLAD1 | 19 | 10 | 15.7 | 87.63 |

| P57088 | TMEM33 | 11 | 6 | 21.9 | 87.04 |

| F8VZ44 | AAAS | 9 | 5 | 19.8 | 81.90 |

| Q07065 | CKAP4 | 30 | 17 | 35.9 | 79.54 |

| Q96CS3 | FAF2 (UBXDB8) | 26 | 11 | 27.2 | 71.19 |

| Q8WUM4 | PDCD6IP | 12 | 8 | 10.4 | 67.34 |

| P46977 | STT3A | 9 | 9 | 13.9 | 65.56 |

| E7EUU4 | EIF4G1 | 21 | 17 | 15.7 | 58.11 |

| Q9Y5V3 | MAGED1 | 16 | 11 | 19.3 | 58.07 |

| Q9UKV5 | AMFR (GP78) | 25 | 12 | 25.2 | 51.68 |

| Q93008 | USP9X | 19 | 13 | 8.3 | 51.59 |

| Q9ULT6 | ZNRF3 | 9 | 6 | 11.2 | h-LMBR1L only |

| F5H7J9 | LRP6 | 4 | 3 | 3.2 | h-LMBR1L only |

| B4DGU4 | CTNNB1 | 4 | 3 | 4.7 | h-LMBR1L only |

| P49840 | GSK3A | 3 | 4 | 13.9 | h-LMBR1L only |

| P49841 |

GSK3B | 1 | 3 | 7.1 | h-LMBR1L only |

Red: ERAD pathway components; blue: Wnt/β-catenin signaling proteins.

Fig. 4. LMBR1L negatively regulates Wnt signaling.

(A, B) LMBR1L physically interacts with components of the Wnt signaling pathway. (A) Human protein microarray revealed binding between LMBRlL and GSK-3β proteins. A construct expressing both N-terminus FLAG-tagged and C-terminus V5-tagged human LMBR1L was transfected into HEK293T cells and the recombinant protein was purified using anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads. Binding between recombinant human LMBR1L and purified human proteins printed in duplicate on the microarray slide was probed with anti-V5-Alexa 647 antibody. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with either FLAG-tagged GSK-3β, β-catenin, ZNRF3, RNF43, FZD6, LRP6, DVL2, or empty vector (EV) and HA-tagged LMBR1L. Lysates were subsequently immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose and immunoblotted with antibodies against HA or FLAG. (C) Immunoblot analysis of β-catenin, phospho-β-catenin, AXIN1, DVL2, GSK-3α/β, phospho-GSK-3β, CK1, β-TrCP, c-Myc, p53, p21, caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-9, cleaved caspase-9, and GAPDH in TCLs of pooled CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− or wild-type littermates. Data are representative of three-to-five independent experiments.

To determine the relationship between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and LMBR1L, we examined Wnt/β-catenin signaling in CD8+ T cells from Lmbr1l−/− and wild-type mice. A key regulatory step in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway involves the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of the Wnt downstream effector protein, β-catenin (22). LMBR1L deficiency resulted in β-catenin accumulation with concomitant decreased levels of phosphorylated-β-catenin relative to those in wild-type cells (Fig. 4C). The β-catenin accumulation was observed in developing thymocytes (DN1–4, DP, SP4, SP8; Fig. S13A, B) as well as naïve and mature T cells in the periphery (Fig. S13B). To determine whether there were changes in the localization of β-catenin, nuclear and cytosolic extracts were isolated from Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells. Immunoblotting revealed increased β-catenin levels in the nuclear fraction of Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. S13C). Tonic β-catenin inactivation requires phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK-3α/β and CK1 within an intact destruction complex composed of scaffolding proteins Axin1 and DVL2, followed by ubiquitination mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP (5, 22). Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells showed decreased total GSK-3α/β and CK1 levels with concomitant increased levels of the inactive form of GSK-3β (phosphorylated-GSK-3β; Fig. 4C). Additionally, Axin1, DVL2, and β-TrCP levels were reduced in Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 4C). Nuclear accumulation of β-catenin upon Wnt activation facilitates upregulation of its target genes, including CD44 and c-Myc. Consistent with the increased β-catenin levels in the nuclear fraction of Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells, we found increased c-Myc expression in total cell lysates (Fig. 4C). c-Myc-induced apoptosis is p53-dependent. The anti-apoptotic cell cycle arrest protein p21 is a target of p53, and is transcriptionally repressed by c-Myc (23). LMBR1L deficiency increased p53 expression, suppressed p21, and increased caspase-3 and −9 cleavage (Fig. 4C). LMBR1L deficiency produced similar effects in CD4+ T and B cells (Fig. S14).

Aberrant Wnt activation in the intestinal epithelium results in adenoma formation and colon cancer (9). However, Lmbr1l−/− intestinal epithelium did not show β-catenin accumulation (Fig. S15A, C), marked expansion of crypts determined by Ki-67 staining (Fig. S15B, D), or intestinal homeostatic abnormalities after oral administration of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS; Fig. S15E). Consistent with the absence of Lmbr1l mRNA expression in LGR5+ intestinal stem cells (24), our findings suggest that other system(s) for regulating β-catenin activity are redundant with LMBR1L in the gut cell environment. These results establish LMBR1L as a lymphocyte-specific negative regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

The LMBR1L–GP78–UBAC2 complex regulates the maturation of Wnt receptors within the ER and stabilizes GSK-3β

Wnt proteins bind to a receptor complex of two molecules, FZD and LRP6 (5). Our findings suggest that LMBR1L acts as a negative regulator of the Wnt pathway. Therefore, we examined whether LMBR1L could regulate Wnt co-receptor expression and/or stability of the destruction complex. An increased level of the mature (glycosylated) form of FZD6 was detected in the membrane fraction of Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells relative to wild-type cells (Fig. 5A). Both mature and immature forms of FZD6 and LRP6 were increased in total cell lysates (TCLs) of Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. LMBR1L–GP78–UBAC2 complex regulates maturation of Wnt receptors within the ER.

(A) Immunoblots of the indicated proteins in membrane and TCLs of pooled CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleens of 12-week-old Lmbr1l−/− or wild-type littermates. The upper band of FZD6 or LRP6 (red arrowhead) is the mature form; the lower band (blue arrowhead) is the ER form of FZD6 or LRP6 (also applies to B, C, E, F). Expression of GRP94 or BiP was determined with a KDEL antibody. GAPDH was used as loading control. *, an unknown KDEL-positive protein whose expression is unchanged. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged FZD6 and either HA-tagged LMBR1L, UBAC2, GP78, or empty vector. TCLs were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads and immunoblotted with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and Ubiquitin (UB). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged LRP6 and HA-tagged LMBR1L, UBAC2, or empty vector. TCLs were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (D) ER or plasma membrane proteins were isolated from LMBR1L-FLAG knock-in (KI) or parental HEK293T cells (WT). Endogenous LMBR1L expression was then analyzed by immunoblotting using a FLAG antibody. Expression of calnexin, E-cadherin, or α-tubulin were used as loading controls for ER, plasma membrane, or cytosol, respectively. (E) Immunoblots of indicated proteins in TCLs of pooled CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleens of 6-week-old Gp78−/− or wild-type mice. (F) Constructs encoding FLAG-tagged LRP6 and HA-tagged LMBR1L were transfected into Gp78−/− or parental HEK293T cells. TCLs were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged β-catenin and either HA-tagged LMBR1L, UBAC2, GP78, or empty vector. TCLs were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads and immunoblotted with antibodies against FLAG, HA, and Ubiquitin (UB). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data are representative of two-to-five independent experiments.

ZNRF3 and RNF43 are negative regulators of the Wnt pathway. ZNRF3 and RNF43 selectively ubiquitinate lysines in the cytoplasmic loops of FZD, which targets FZD for degradation at the plasma membrane (8). In addition, DVL proteins act as an intermediary for ZNRF3/RNF43-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of FZD (10). We found that ZNRF3/RNF43 levels were altered in the membrane fraction of Lmbr1−/− CD8+ T cells compared to levels in wild-type cells. In the TCLs, ZNRF3 levels were unchanged, whereas RNF43 levels were slightly increased (Fig. 5A).

UBAC2 is a core component of the GP78 ubiquitin ligase complex expressed on the ER membrane. UBAC2 physically interacts with and adds poly-UB chains to UBXD8, a protein involved in substrate extraction during ERAD (21, 25). We hypothesized that the interaction of LMBR1L with UBAC2, GP78, and UBXD8 might regulate the activity of the GP78 ubiquitin ligase complex towards FZD and/or LRP6. Transient co-transfection of HEK293T cells with FLAG-tagged FZD6 and HA-tagged LMBR1L or UBAC2 resulted in decreased total levels of the mature FZD6 (Fig. 5B). Co-expression of FLAG-tagged FZD6 and HA-tagged GP78 strongly decreased both the mature and immature form of FZD6. In contrast to LMBR1L, UBAC2 and GP78 strongly promoted ubiquitination of FZD6 (Fig. 5B). In addition, whereas GFP-tagged FZD6 localized to both plasma membrane and ER in HEK293T cells, co-expression of LMBR1L with FZD6-GFP altered the localization of FZD6-GFP, causing it to accumulate in the ER and inhibiting its expression on the plasma membrane (Fig. S16). ER stress was observed in Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells as indicated by increased expression of binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94) compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 5A). We also found that LMBR1L expression preferentially decreased mature LRP6 whereas UBAC2 decreased both mature and immature LRP6 (Fig. 5C). LMBR1L, for which no functional domain has previously been reported, is known to localize at the plasma membrane (17, 18). However, our data suggest that LMBR1L may function as a core component of the GP78–UBAC2 ubiquitin ligase complex, and that LMBR1L-mediated maturation of Wnt co-receptors may be regulated within the ER.

To test this hypothesis, we generated a CRISPR-based knock-in of a FLAG-tag appended to the C-terminus of endogenous LMBR1L protein in HEK293T cells. Most LMBR1L-FLAG was expressed in the ER of these cells, and only a small fraction was localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5D). We also knocked out Ubac2 or Gp78 in HEK293T cells (Fig. S17A) and the mouse T cell line EL4 (Fig. S17B) using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Increased FZD6 and LRP6 were detected in both the Ubac2−/− and Gp78−/− cells relative to the parental HEK293T or EL4 cells (Fig. S17). Similar to LMBR1L deficiency in primary CD8+ T cells, GP78 deficiency in HEK293T or EL4 cells also resulted in β-catenin accumulation (Fig. S17). Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-targeted Gp78 knockout mice were generated and used to confirm that GP78 deficiency in primary CD8+ T cells results in increased FZD6 and LRP6 expression as well as β-catenin accumulation (Fig. 5E). We also examined the effect of UBAC2 on FZD6 maturation mediated by LMBR1L after transient transfection of FLAG-tagged FZD6, HA-tagged LMBR1L, and EGFP in Ubac2−/− or parental HEK293T cells. Increasing amounts of LMBR1L significantly reduced the amount of mature FZD6 and increased the amount of immature FZD6 without affecting EGFP expression in wild-type HEK293T cells (Fig. S18). However, increasing amounts of LMBR1L in Ubac2−/− cells failed to inhibit FZD6 maturation as efficiently as in wild-type cells (Fig. S18). In addition, the preferential inhibition of mature LRP6 by LMBR1L observed in wild-type cells was partially rescued in Gp78−/− cells, and total expression of LRP6 was notably higher (Fig. 5F). Similarly, transient co-transfection of HEK293T cells with FLAG-tagged β-catenin and HA-tagged LMBR1L, UBAC2, or GP78 resulted in decreased total levels of β-catenin compared to the empty vector control (Fig. 5G). Using co-IP, we confirmed a physical interaction between GP78 and β-catenin (Fig. S19A). Co-expression of FLAG-tagged β-catenin and HA-tagged GP78 strongly promoted the ubiquitination of β-catenin (Fig. 5G). Conversely, increased β-catenin expression was observed in Gp78−/− cells compared to parental HEK293T cells after transient transfection of FLAG-tagged β-catenin (Fig. S19B). Thus, the LMBR1L–GP78–UBAC2 complex appears to prevent maturation of FZD6 and the Wnt co-receptor LRP6 within the ER of lymphocytes. Furthermore, the LMBR1L–GP78–UBAC2 complex may regulate the ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin.

Another striking difference observed in Lmbr1l−/− T cells was that several components of the destruction complex were expressed at lower levels than in wild-type cells, including scaffolding protein Axin1, DVL2, kinases GSK-3α/β and CK1, and the E3 ligase β-TrCP (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, Lmbr1l−/− T cells showed the decreased expression of phosphorylated-β-catenin and phosphorylated-LRP6 (Fig. 4C and Fig. 5A, respectively), increased phosphorylated-GSK-3β (Fig. 4C), and the activation of kinases such as Akt and p70S6K (Fig. 3B) which inactivates GSK-3β by phosphorylation. Thus, we hypothesized that the LMBR1L–GP78–UBAC2 complex may regulate the stability of destruction complex components such as GSK-3β, which has both inhibitory and stimulatory roles in Wnt/β-catenin signaling by phosphorylating β-catenin and LRP6, respectively (26). Transient co-transfection of HEK293T cells with FLAG-tagged Axin1, DVL2, or GSK-3β and HA-tagged LMBR1L or empty vector resulted in decreased total levels of FLAG-tagged Axin1 protein in the presence of HA-LMBR1L compared to empty vector control. However, LMBR1L had no effect on DVL2 or GSK-3β expression (Fig. S20), nor on the level of phosphorylated GSK-3β (Fig. 6A). To measure the effect of LMBR1L on the half-life of GSK-3β, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged GSK-3β and HA-tagged LMBR1L or empty vector. Fourteen hours after transfection, cells were treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) and harvested at various times post-treatment. In the presence of LMBR1L, no detectable decrease of GSK-3β was observed up to 4 h after CHX treatment, suggesting that LMBR1L stabilizes GSK-3β (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. LMBR1L stabilizes GSK-3β.

(A) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged GSK-3β and either HA-tagged LMBR1L or empty vector. TCLs were immuno-precipitated using anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads and immunoblotted with antibodies against p-GSK-3β, FLAG, and HA. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged GSK-3β and either HA-tagged LMBR1L or empty vector. The cells were treated with cyclohexamide (CHX) 14 h after transfection and harvested at various times post-treatment. TCLs were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Two primary antibodies (anti-HA and GAPDH) were co-incubated to visualize LMBR1L (red arrowhead) and GAPDH (blue arrowhead, a loading control) on one membrane. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

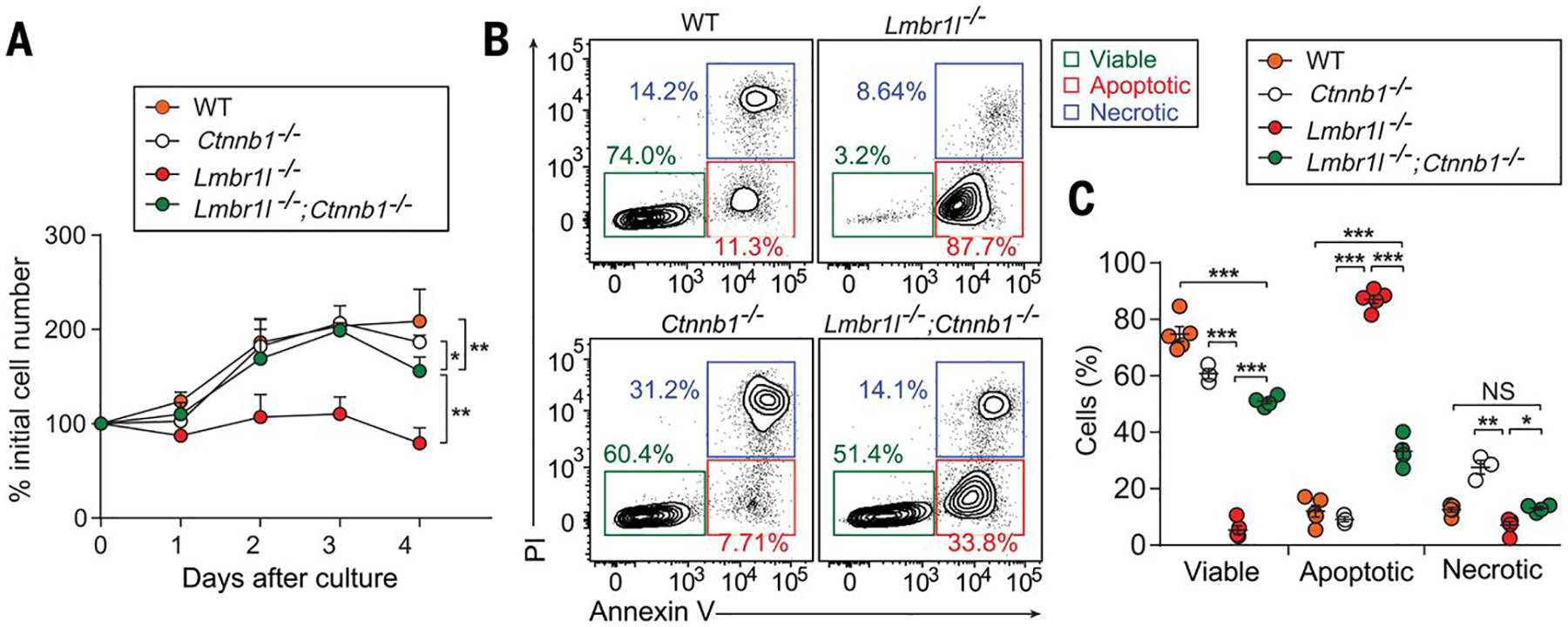

Cumulative evidence suggests that LMBR1L serves as a negative regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To test whether the observed phenotypes depend on the pathway, we knocked out Lmbr1l, β-catenin (Ctnnb1), or Lmbr1l and Ctnnb1 in EL4 cells using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Similar to the phenotype observed in primary Lmbr1l−/− CD8+ T cells, Lmbr1l−/− EL4 cells showed severe defects in proliferation even under normal culture conditions (Fig. 7A). Annexin V and PI staining showed that the majority of the Lmbr1l−/− EL4 cells were apoptotic (Fig. 7B: top right, C). An increased frequency of necrotic cells was detected among Ctnnb1−/− EL4 cells compared to parental wild-type EL4 cells (Fig. 7B: bottom left, C); however, their growth was normal (Fig. 7A). Deletion of Ctnnb1 in Lmbr1l−/− EL4 cells substantially restored proliferative potential and decreased apoptosis compared to Lmbr1l−/− EL4 cells (Fig. 7A, B: bottom right, C); however, proliferation and apoptosis did not reach levels observed in parental wild-type Ctnnb1−/− EL4 cells (Fig. 7A, B). These results provide genetic evidence that β-catenin is downstream of LMBR1L in a mouse T lymphocyte transformed cell line and suggest that the observed phenotypes in LMBR1L deficient T cells are largely dependent on Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Fig. 7. Deletion of β-catenin (Ctnnb1) attenuates apoptosis caused by LMBR1L-deficiency.

(A-C) Growth curve (A) and Annexin V/PI staining (B) of Lmbr1l−/−, Ctnnb1−/−, and Lmbr1l−/−;Ctnnb1−/− EL4 cells generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system (n = 3–5 clones/genotype), and parental wild-type (WT) EL4 cells. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas (B) indicate percent cells in each. (C) Quantification of the percentage of viable, apoptotic, and necrotic Lmbr1l−/−, Ctnnb1−/−, Lmbr1l−/−;Ctnnb1−/−, or parental WT EL4 cells. Each symbol represents an individual cell clone. P-values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars indicate S.D. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01.

Concluding remarks

Our findings demonstrate the existence of a pathway that regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in lymphocytes. The exaggerated apoptosis of T cells that results in lymphopenia in LMBR1L-deficient mice stems from the aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In the absence of LMBR1L, the expression of mature forms of Wnt co-receptors and phosphorylated GSK-3β were highly upregulated, whereas the expression of multiple destruction complex proteins was reduced. These alterations contributed to the accumulation of β-catenin, which enters the nucleus and promotes the transcription of target genes such as Myc, Trp53, and Cd44. This signal transduction cascade favors apoptosis in an intrinsic and extrinsic caspase cascade-dependent manner.

We report herein a second “destruction complex” in the ER, comprising LMBR1L, GP78, and UBAC2, which controls Wnt signaling activity in lymphocytes by regulating Wnt receptor availability independent of ligand binding (Fig. S21). Furthermore, LMBR1L supports the expression and/or stabilization of the canonical destruction complex including GSK-3β that is necessary for degradation of β-catenin and activation of LRP6. Because human and mouse LMBR1L orthologues share 96% identity (Fig. S22), we consider it likely that the same mechanism operates in human lymphoid cells and their progenitors. LMBR1L deficiency may be considered as a possible etiology in unexplained pan-lymphoid immunodeficiency disorders.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Eight-to-ten-week old pure C57BL/6J background males purchased from The Jackson Laboratory were mutagenized with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) as described previously (27). Mutagenized G0 males were bred to C57BL/6J females, and the resulting G1 males were crossed to C57BL/6J females to produce G2 mice. G2 females were backcrossed to their G1 sires to yield G3 mice, which were screened for phenotypes. Whole-exome sequencing and mapping were performed as described (11). C57BL/6.SJL (CD45.1), Rag2−/−, Tnf-α−/−, Casp3−/−, Faslpr, B2mtm1Unc (B2m−/−) and Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb (OT-I) transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CD45.1;Lmbr1lst/st, Lmbr1l−/−;Tnf-α−/−, Lmbr1l−/−;Casp3−/−, Lmbr1l−/−;Faslpr/lpr, Lmbr1l−/−;OT-I mice were generated by intercrossing mouse strains. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and all experimental procedures were performed in accordance with institutionally approved protocols.

Bone marrow chimeras

Recipient mice were lethally irradiated with 13 Gy via gamma radiation (X-RAD 320, Precision X-ray Inc.). The mice were given an intravenous injection of 5 × 106 bone marrow cells derived from the tibia and femurs of the respective donors. For 4 weeks post-engraftment, mice were maintained on antibiotics. Twelve weeks after bone marrow engraftment, the chimeras were euthanized to assess immune cell development in bone marrow, thymus, and spleen by flow cytometry. Chimerism was assessed using congenic CD45 markers.

Flow cytometry

Detailed information on antibodies used for flow cytometry is provided in Supplementary Materials.

Bone marrow cells, thymocytes, splenocytes, or peripheral blood cells were isolated, and red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer was added to remove RBCs. Cells were stained at a 1:200 dilution with 15 mouse fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for the following murine cell surface markers encompassing the major immune lineages: B220, CD3ε, CD4, CD5, CD8α, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, CD43, CD44, CD62L, F4/80, IgD, IgM, and NK1.1 in the presence of anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody for 1 h at 4 °C. After staining, cells were washed twice in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

To stain the hematopoietic progenitor compartment, bone marrow was isolated and stained with Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated lineage markers (B220, CD3, CD11b, Ly-6G/6C, and Ter-119), CD16/32, CD34, CD135, c-Kit, IL-7Rα, and Sca-1 for 1 h at 4 °C. After staining, cells were washed twice in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

PE-conjugated Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer, a reagent specific for the ovalbumin epitope peptide SIINFEKL presented by H-2Kb (MHC Tetramer Core at Baylor College of Medicine) was used to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses and memory CD8+ T cell formation in mice immunized with aluminum-hydroxide precipitated ovalbumin.

To detect intracellular β-catenin, thymi were homogenized to generate a single-cell suspension and surface stained for CD3, CD25, and CD44. Cells were then permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit followed by intracellular β-catenin staining. Data were acquired on an LSRFortessa cell analyzer (BD Bioscience) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar).

Immunization

Twelve-to-sixteen-week-old G3 mice or Lmbr1l−/−, Cers5−/−, and wild-type littermates were immunized (i.m.) with T cell-dependent antigen (TD) aluminum hydroxide-precipitated ovalbumin (OVA/alum; 200 μg; Invivogen) on day 0. Fourteen days after OVA/alum immunization, blood was collected in MiniCollect Tubes (Mercedes Medical) and centrifuged at 1,500 g to separate the serum for ELISA analysis. Three days after bleeding, mice were immunized with another TD antigen, rSFV-βGal (2 × 106 IU; (28)) on day 0 and the T cell-independent antigen (TI) NP50-AECM-Ficoll (50 μg; Biosearch Technologies) on day 8 (i.p.) as previously described (29). Six days after NP50-AECM-Ficoll immunization, blood was collected for ELISA analysis.

In vivo CTL and NK cytotoxicity

Cytolytic CD8+ T cell effector function was determined by a standard in vivo cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay. Briefly, splenocytes were isolated from naïve mice and divided in half. According to established methods (30), half were stained with 5 μM CFSE (CFSEhi), and half were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE (CFSElo). CFSEhi cells were pulsed with 5 μM ICPMYARV peptide, which carries E. coli β-galactosidase MHC I epitope for mice with the H-2b haplotype (New England Peptide; (31). CFSElo cells were not stimulated. CFSEhi and CFSElo cells were mixed (1:1) and 2 × 106 cells were administered to naïve mice and mice immunized with rSFV-βgal through retro-orbital injection. Blood was collected 24 h after adoptive transfer, and CFSE intensities from each population were assessed by flow cytometry. Lysis of target (CFSEhi) cells was calculated as: % lysis = [1 – (ratio control mice/ratio vaccinated mice)] × 100; ratio = percent CFSElo/percent CFSEhi.

To measure NK cell-mediated killing, splenocytes from control C57BL/6J (0.5 μM Violet; Violetlo) and B2m−/− mice (5 μM Violet; Violethi) were stained with CellTrace Violet. Equal numbers of Violethi and Violetlo cells were transferred by retro-orbital injection. Twenty-four hours after transfer, blood was collected and Violet intensity from each population was assessed by flow cytometry. % lysis = [1 – (target cells/control cells) / (target cells/control cells in B2m−/−)] × 100.

MCMV challenge

Mice were infected with MCMV (Smith strain; 1.5 × 105 pfu/20 g of body weight) by intraperitoneal injection as described previously (32). Mice were euthanized 5 days after MCMV challenge to determine viral loads. Total DNA extracted from individual mouse spleen was used to measure copy numbers of MCMV immediate-early 1 (IE1) gene and control DNA sequence (β-actin). The viral titer is represented as the copy number ratio of MCMV IE1 to β-actin.

In vivo T cell activation

Splenic CD45.2+ OT-I and Lmbr1−/−;OT-I T cells were purified using the EasySep™ Mouse CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (StemCell Technologies). Purities were over 95% in all experiments as tested by flow cytometry. Cells were labeled with 5 μM CellTrace Far Red (CD45.2+ OT-I) or 5 μM CellTrace Violet (Lmbr1−/−;OT-I), and equal number of stained cells (2 × 106) cells were injected by retro-orbital route into wild-type CD45.1+ mice. The next day, recipients were injected with either 100 μg of soluble OVA in 200 μl of PBS or 200 μl of sterile PBS as a control. Antigen (OVA)-specific T cell activation was analyzed based on Far Red or Violet intensity of dividing OT-I cells after 48 h and 72 h.

To assess the proliferative capacity of T cells in response to homeostatic proliferation signals, splenic pan T cells or mature SP thymocytes (CD24−) were isolated by using the EasySep™ Mouse Pan T Cell Isolation Kit (StemCell Technologies) or Dynal negative selection using biotinylated anti-CD24 mAb M1/69 (eBioscience), respectively. Pan T or mature CD24− thymocytes isolated from Lmbr1l−/−, Lmbr1lst/st or wild-type littermates were stained with 5 μM CellTrace Violet or CellTrace Far Red, respectively. A 1:1 or 10:1 mix of labeled Lmbr1l−/− or wild-type cells was transferred into C45.1+ mice that had been sublethally irradiated (8 Gy) 6 h earlier or into unirradiated controls. Four or seven days after adoptive transfer, splenocytes were prepared, surface stained for CD45.1, CD45.2, together with CD3, CD4, and CD8 and then analyzed by flow cytometry for Far Red or Violet dye dilution.

Detection of apoptosis

Annexin V/PI labeling and detection was performed with the FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Bioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry were performed to identify Lmbr1l-interacting proteins as described below. Transfection was performed in HEK293T cells (ATCC) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life technologies) with plasmid encoding Flag tagged-human Lmbr1l or empty vector control. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested in NP-40 lysis buffer for 45 min at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) for 2 h at 4 °C and beads were washed six times in NP-40 lysis buffer. The proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and heated at 95 °C for 10 min. Lysates were loaded onto 12% (wt/vol) SDS–PAGE gel and run ~1 cm into the separation gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue (Thermo Fisher) and whole stained lanes were subjected to mass spectrometry analysis (LC–MS/MS) as described previously (33).

Protein array

The ProtoArray Human Protein Microarray V5.1 (Invitrogen) was used to identify human Lmbr1l–interacting proteins according to manufacturer`s instructions. Briefly, Flag (N-terminus)- and V5 (C-terminus)-tagged recombinant human Lmbr1l protein was expressed in HEK293T cells by transfection and purified with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma). The presence of the Flag and V5 tag on the protein was confirmed by standard immunoblot.

Purified recombinant Flag-human LMBR1L-V5 was used to probe a Human V5.1 ProtoArray (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Binding of the recombinant protein on the array was detected with streptavidin Alexa Fluor 647 at a 1:1,000 dilution in Protoarray blocking buffer (Invitrogen). The array was scanned using a GeneArray 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices) at 635 nm. Results were saved as a multi-TIFF file and analyzed using Genepix Prospector software, version 7.

Isolation of plasma membrane or endoplasmic reticulum

Proteins from the plasma membrane or endoplasmic reticulum were isolated using the Pierce Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher) or Endoplasmic Reticulum Enrichment Extraction Kit (Novus Biologicals), respectively, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between groups was analyzed using GraphPad Prism by performing the indicated statistical tests. Differences in the raw values among groups were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. P-values are denoted by * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, not significant with P > 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank D. LaVine for expert assistance with the design and illustration of the summary figure.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01-AI125581) and by the Lyda Hill foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Plasmids have been deposited in Addgene; please see ID numbers in supplementary materials. All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes:

- 1.Verbeek S et al. , An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature 374, 70–74 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reya T et al. , Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity 13, 15–24 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T et al. , A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423, 409–414 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staal FJ, Luis TC, Tiemessen MM, WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 581–593 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nusse R, Clevers H, Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong C, Chen C, Wu Q, Liu Y, Zheng P, A critical role for the regulated wnt-myc pathway in naive T cell survival. J Immunol 194, 158–167 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang X, Cong F, Novel Regulation of Wnt Signaling at the Proximal Membrane Level. Trends Biochem Sci 41, 773–783 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao HX et al. , ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 485, 195–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koo BK et al. , Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488, 665–669 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Charlat O, Zamponi R, Yang Y, Cong F, Dishevelled promotes Wnt receptor degradation through recruitment of ZNRF3/RNF43 E3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell 58, 522–533 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T et al. , Real-time resolution of point mutations that cause phenovariance in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E440–449 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luis TC et al. , Canonical wnt signaling regulates hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent fashion. Cell Stem Cell 9, 345–356 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao DM et al. , Constitutive activation of Wnt signaling favors generation of memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol 184, 1191–1199 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow BJ, Abduragimov AR, Farahbakhsh ZT, Faull KF, Hubbell WL, Tear lipocalins bind a broad array of lipid ligands. Curr Eye Res 14, 363–372 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesselink RW, Findlay JB, Expression, characterization and ligand specificity of lipocalin-1 interacting membrane receptor (LIMR). Mol Membr Biol 30, 327–337 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redl B, Holzfeind P, Lottspeich F, cDNA cloning and sequencing reveals human tear prealbumin to be a member of the lipophilic-ligand carrier protein superfamily. J Biol Chem 267, 20282–20287 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojnar P, Lechner M, Merschak P, Redl B, Molecular cloning of a novel lipocalin-1 interacting human cell membrane receptor using phage display. J Biol Chem 276, 20206–20212 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wojnar P, Lechner M, Redl B, Antisense down-regulation of lipocalin-interacting membrane receptor expression inhibits cellular internalization of lipocalin-1 in human NT2 cells. J Biol Chem 278, 16209–16215 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fluckinger M, Merschak P, Hermann M, Haertle T, Redl B, Lipocalin-interacting-membrane-receptor (LIMR) mediates cellular internalization of beta-lactoglobulin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778, 342–347 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z et al. , Interaction of uteroglobin with lipocalin-1 receptor suppresses cancer cell motility and invasion. Gene 369, 66–71 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christianson JC et al. , Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol 14, 93–105 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li VS et al. , Wnt signaling through inhibition of beta-catenin degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell 149, 1245–1256 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seoane J, Le HV, Massague J, Myc suppression of the p21(Cip1) Cdk inhibitor influences the outcome of the p53 response to DNA damage. Nature 419, 729–734 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haber AL et al. , A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature 551, 333–339 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd SJ, Raychaudhuri S, Espenshade PJ, Subunit architecture of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase required for sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 288, 21043–21054 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng X et al. , A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature 438, 873–877 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgel P, Du X, Hoebe K, Beutler B, ENU mutagenesis in mice. Methods Mol Biol 415, 1–16 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidmark AS et al. , Humoral responses against coimmunized protein antigen but not against alphavirus-encoded antigens require alpha/beta interferon signaling. J Virol 80, 7100–7110 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold CN et al. , A forward genetic screen reveals roles for Nfkbid, Zeb1, and Ruvbl2 in humoral immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 12286–12293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi JH et al. , A single sublingual dose of an adenovirus-based vaccine protects against lethal Ebola challenge in mice and guinea pigs. Mol Pharm 9, 156–167 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oukka M, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Tanaka Y, Babinet C, Kosmatopoulos K, Medullary thymic epithelial cells induce tolerance to intracellular proteins. J Immunol 156, 968–975 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crozat K et al. , Analysis of the MCMV resistome by ENU mutagenesis. Mamm Genome 17, 398–406 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z et al. , Insulin resistance and diabetes caused by genetic or diet-induced KBTBD2 deficiency in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E6418–E6426 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.