Abstract

Background

Nivolumab combined with ipilimumab have shown activity in melanoma brain metastasis (MBM). However, in most of the clinical trials investigating immunotherapy in this subgroup, patients with symptomatic MBM and/or prior local brain radiotherapy were excluded. We studied the efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab alone or in combination with local therapies regardless of treatment line in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic MBM.

Methods

Patients with MBM treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in 23 German Skin Cancer Centers between April 2015 and October 2018 were investigated. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier estimator and univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed to determine prognostic factors associated with OS.

Results

Three hundred and eighty patients were included in this study and 31% had symptomatic MBM (60/193 with data available) at the time of start nivolumab plus ipilimumab. The median follow-up was 18 months and the 2 years and 3 years OS rates were 41% and 30%, respectively. We identified the following independently significant prognostic factors for OS: elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase and protein S100B levels, number of MBM and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status. In these patients treated with checkpoint inhibition first-line or later, in the subgroup of patients with BRAFV600-mutated melanoma we found no differences in terms of OS when receiving first-line either BRAF and MEK inhibitors or nivolumab plus ipilimumab (p=0.085). In BRAF wild-type patients treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in first-line or later there was also no difference in OS (p=0.996). Local therapy with stereotactic radiosurgery or surgery led to an improvement in OS compared with not receiving local therapy (p=0.009), regardless of the timepoint of the local therapy. Receiving combined immunotherapy for MBM in first-line or at a later time point made no difference in terms of OS in this study population (p=0.119).

Conclusion

Immunotherapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, particularly in combination with stereotactic radiosurgery or surgery improves OS in asymptomatic and symptomatic MBM.

Keywords: immunology, oncology, radiotherapy, surgery

Introduction

Melanoma brain metastasis (MBM) is a known characteristic for poor prognosis. The median overall survival (mOS) in the era of chemotherapy was 4 months and decreased to 2 months in patients with elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).1 2 The response of MBM to chemotherapy was approximately 5%. This applies to both, drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier, such as temozolomide and fotemustine, and to drugs that do not cross the blood-brain barrier, such as dacarbazine.3 4 The American Joint Committee on Cancer has acknowledged the negative impact of brain metastasis on the prognosis of patients with melanoma in its latest eighth edition staging system by defining this subgroup as M1d.5

With the introduction of targeted treatment (BRAF/MEK inhibitors) and immune checkpoint inhibitors, the prognosis of metastatic melanoma has drastically improved.6–8 In contrast to ample data on the efficacy of novel therapies in stage IV melanoma without MBM, there are only a few small studies on the efficacy of these drugs in patients with cerebral disease. This lack of information is mainly due to the fact that large phase II/III multicenter studies systematically excluded patients with MBM, particularly if symptomatic or previously treated with local therapy, such as stereotactic radiosurgery and surgery (STR/surgery). The first studies investigating targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with MBM showed that these therapies were also very effective intracranially.9–12 Currently available data suggest that PD-1-based immunotherapy and particularly combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab (NIVO+IPI) might be more effective than BRAF/MEK inhibitors.8 13 In two retrospective studies with patients with MBM, the authors reported that patients receiving immunotherapy had a mOS between 13 and 14.8 months (95% CI: 8.1 to 17.8 and 9.9 to 19.7, respectively), while in those receiving targeted therapy the mOS was only 7 and 10 months (95% CI: 3.8 to 10.2 and 7.8 to 11.7, respectively).14 15 This difference was also present when these systemic therapies were given in combination with stereotactic radiosurgery, favoring the combination with immunotherapy, which resulted in a mOS between 21–25 months (95% CI: 12.9 to 29.1 and 14.6 to 35.4, respectively) and 12.9–14 months with targeted therapy (95% CI: 12.9 to 29.1 and 9.1 to 16.7, respectively).

Our study provides real-world outcome data from 23 German skin cancer centers, retrospectively assessing the activity of NIVO+IPI alone or in combination with local therapies regardless of treatment line in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic MBM.

We addressed the following questions: (a) Which prognostic factors for OS can be identified in patients with MBM treated with combined immunotherapy? (b) Does local therapy (STR/surgery) improves survival in patients with MBM treated with NIVO+IPI? (c) Are STR/surgery more effective when given before or after combined immunotherapy? (d) Is there a difference in terms of survival when combined immunotherapy is given as a first-line treatment for MBM or later in the course of the disease? (e) In patients with BRAF V600-mutated melanoma, which first-line systemic therapy for MBM translates into better OS: first-line immunotherapy or first-line targeted therapy? (f) Is there a difference in terms of OS when patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic MBM receive NIVO+IPI? Since a total of 380 patients were included, we were able to perform subgroup analyses with reasonable statistical power.

Methods

Patients’ characteristics and treatments

We used pseudo-anonymized forms to document retrospective data from patients with MBM treated with NIVO+IPI between April 2015 and October 2018. All participating centers received the mentioned pseudo-anonymized forms including the prespecified information to be collected. Data were extracted from patients’ medical records in 23 German skin cancer centers either by medical doctors or by clinical research documentation professionals, depending on the site. Patients were included regardless of previous local or systemic therapies, provided that they received combined immunotherapy for treating MBM.

Multiple MBM were irradiated by whole brain irradiation with opposite lateral field in mask technique. Stereotactic radiosurgery was used to irradiate small brain metastasis. Neuroimaging consisted of a stereotactic three-dimensional T1-weighted postcontrast Magnetic Ressonance Imaging (MRI) acquisition und an planning CT scan. Selection of dosimetry parameters (maximum dose, marginal isodose and number of isocenters) was made according to size, shape, localization and relationship for brain metastasis to critical structures. Target localization was referenced to a coordination system and target position was tracked during treatment. The data cut-off date was October 31, 2018.

Statistical Analysis

We performed univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis to evaluate the impact of baseline patient and disease characteristics on OS. Cox multivariate analysis included the following factors: sex, BRAF mutation status, number of MBM, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) as categorical variables and age, LDH level and protein S100B level as both categorical and numerical variables. The use of corticosteroids at the start of combined immunotherapy was also documented. As these data are rather complex regarding dosage and duration of each individual treatment, they will be analyzed in a separate investigation.

OS and follow-up (FU) time were calculated considering the date of MBM diagnosis and last patient contact or death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used for the calculation of OS. Differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. Patients were grouped considering the timing of combined immunotherapy (first-line or not first-line) for treatment of MBM and according to BRAF mutation status (BRAFV600 mutant or BRAF wild type). Pretreatment protein S100B and LDH values were assigned categorical variables (normal, elevated and 2-fold or 10-fold elevated), according to the institutional upper limit of normal. Patients with missing values were excluded from the respective analysis. Further subgroups considering the number of MBM, presence of neurological symptoms and ECOG-PS were defined. To investigate the effect of local therapies on OS, data from patients receiving STR/surgery were compared with data from patients not receiving local therapies. Timing of local therapy and its effect on OS were analyzed by defining two groups: STR/surgery before start of NIVO+IPI treatment or STR/surgery at a later time point. Patients treated with whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) were evaluated separately. Results are reported as two-sided p values with 95% CIs. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Patients characteristics

A total of 380 patients with MBM and NIVO+IPI treatment were included in the analysis (table 1, online supplementary figure S1). Thirty-seven per cent of the patients were females and median age at the time of MBM diagnosis was 58 years (IQR 49–68). The majority of melanomas (63.7%) carried a BRAFV600 mutation.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics of the whole collective (n=380) considering combined immunotherapy at first line or not at first line

| Baseline characteristics | Total | CombiIT first line | CombiIT not first line | P value* |

| N (%) | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 240 (63.2) | 165 (66) | 75 (57.7) | 0.111 |

| Female | 140 (36.8) | 85 (44) | 55 (42.3) | |

| Age (years) at the time of CombiIT | ||||

| <54 | 153 (40.3) | 90 (36) | 63 (48.5) | 0.024 |

| 54–64 | 105 (27.6) | 69 (27.6) | 36 (27.7) | |

| >64 | 122 (32.1) | 91 (36.4) | 31 (23.8) | |

| BRAF status | ||||

| BRAF wild type | 138 (36.3) | 112 (44.8) | 26 (20) | < 0.0001 |

| BRAF mutant | 242 (63.7) | 138 (55.2) | 104 (80) | |

| LDH level† | ||||

| Normal | 189 (51.4) | 131 (54.1) | 58 (46.0) | 0.223 |

| Elevated | 133 (36.1) | 85 (35.1) | 48 (38.1) | |

| 2×>ULN | 46 (12.5) | 26 (10.8) | 20 (15.9) | |

| S100B level† | ||||

| Normal | 109 (32.8) | 69 (31.2) | 40 (36.4) | 0.597 |

| Elevated | 156 (47) | 106 (47.7) | 50 (45.4) | |

| 10×>ULN | 67 (20.2) | 47 (21.1) | 20 (18.2) | |

| Number of MBM at the time of CombiIT† | ||||

| 1–3 | 167 (46.8) | 127 (53.6) | 40 (33.3) | < 0.0001 |

| >3 | 190 (53.2) | 110 (46.4) | 80 (66.7) | |

| ECOG-PS† | ||||

| 0 | 249 (66.4) | 168 (67.7) | 81 (63.8) | 0.741 |

| 1 | 87 (23.2) | 55 (22.2) | 32 (25.2) | |

| >1 | 39 (10.4) | 25 (10.1) | 14 (11) | |

| Presence of symptoms† | ||||

| Yes | 60 (31) | 44 (32.1) | 16 (28.6) | 0.629 |

| No | 133 (69) | 93 (67.9) | 40 (71.4) | |

| Local therapy | ||||

| STR/surgery‡ | 220 (57.9) | 135 (54) | 85 (65.4) | 0.011 |

| No local therapy | 90 (23.7) | 71 (28.4) | 19 (14.6) | |

| WBRT | 70 (18.4) | 44 (17.6) | 26 (20) | |

Bold values indicate statistically significant results.

*Pearson’s χ2 test.

†Denotes variables for which the missing/unknown values were excluded from the analysis.

‡Ten patients (4.5%) received only surgery. Four patients receiving STR/surgery before combined immunotherapy and two patients receiving STR/surgery after combined immunotherapy were treated with the two techniques within an interval of 2 weeks.

CombiIT, nivolumab plus ipilimumab; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MBM, melanoma brain metastases; n, number of patients in each subgroup; STR, stereotactic radiosurgery; ULN, upper level normal; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy.

jitc-2019-000333supp001.pdf (362KB, pdf)

In the univariate Cox regression analysis (table 2), we found the following significant prognostic factors for OS: LDH level, favoring patients with normal LDH (p<0.0001), number of MBM (p=0.001) favoring patients with 1–3 MBM and ECOG-PS (p=0.001) favoring patients with ECOG-PS=0. No significant OS difference was observed for baseline S100B level (p=0.099), BRAFV600 mutation status (p=0.962), age groups (p=0.616), sex (p=0.682) and presence of symptomatic MBM (p=0.078). Multivariate Cox regression analysis using categorical variables (table 2) showed that the number of MBM (p=0.008) and ECOG-PS (p=0.006) were independent prognostic factors for OS. In the multivariate Cox regression analysis using numerical variables for age, serum LDH and protein S100B (online supplementary table S4), the following prognostic factors were found to be an independently associated with OS: LDH (p=0.001), protein S100B (p=0.001), number of MBM (p=0.017) and ECOG-PS (p=0.041).

Table 2.

Impact of baseline patient and disease characteristics on overall survival: univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis

| Total N (%) |

Univariate analysis | P value | Multivariate analysis | P value | |

| HR (death) (95% CI) |

HR (death) (95% CI |

||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 240 (63.2) | 1 | 1 | 0.855 | |

| Female | 140 (36.8) | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.27) | 0.682 | 1.35 (0.70 to 1.50) | |

| Age (years) at the time of CombiIT | |||||

| <54 | 153 (40.3) | 1 | 0.616 | 1 | 0.689 |

| 54–64 | 105 (27.6) | 1.13 (0.78 to 1.62) | 1.17 (0.75 to 1.81) | 0.491 | |

| >64 | 122 (32.1) | 1.19 (0.83 to 1.70) | 1.20 (0.76 to 1.90) | 0.428 | |

| BRAF status | |||||

| BRAF wild type | 138 (36.3) | 1 | 0.962 | 1 | |

| BRAF mutant | 242 (63.7) | 0.99 (0.72 to 1.37) | 1.13 (0.76 to 1.67) | 0.548 | |

| LDH level* | |||||

| Normal | 189 (51.4) | 1 | < 0.0001 | 1 | 0.069 |

| Elevated | 133 (36.1) | 1.24 (0.88 to 1.74) | 1.05 (0.69 to 1.59) | 0.831 | |

| 2×>ULN | 46 (12.5) | 2.53 (1.67 to 3.83) | 1.80 (1.05 to 3.09) | 0.031 | |

| S100B level* | |||||

| Normal | 109 (32.8) | 1 | 0.099 | 1 | 0.325 |

| Elevated | 156 (47) | 1.35 (0.92 to 2.00) | 1.39 (0.90 to 2.11) | 0.135 | |

| 10×>ULN | 67 (20.2) | 1.61 (1.02 to 2.54) | 1.30 (0.76 to 2.24) | 0.341 | |

| Number of MBM at the time of CombiIT* | |||||

| 1–3 | 167 (46.8) | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.008 |

| >3 | 190 (53.2) | 1.74 (1.26 to 2.40) | 1.67 (1.14 to 2.44) | ||

| ECOG-PS* | |||||

| 0 | 249 (66.4) | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.006 |

| 1 | 87 (23.2) | 1.3 (0.91 to 1.87) | 1.31 (0.87 to 1.99) | 0.188 | |

| >1 | 39 (10.4) | 2.58 (1.66 to 4.00) | 2.42 (1.39 to 4.20) | 0.002 | |

| Presence of symptomatic MBM* | |||||

| No | 133 (69) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 60 (31) | 1.46 (0.96 to 2.23) | 0.078 | N/A |

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p<0.05).

*Denotes variables for which the missing/unknown values were excluded from the analysis.

CombiIT, nivolumab plus ipilimumab; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MBM, melanoma brain metastases; N, number of patients in each subgroup; N/A, not performed for this factor, since information was available to only 50% of the patients; ULN, upper level normal.

Overall survival analysis considering systemic and local therapy

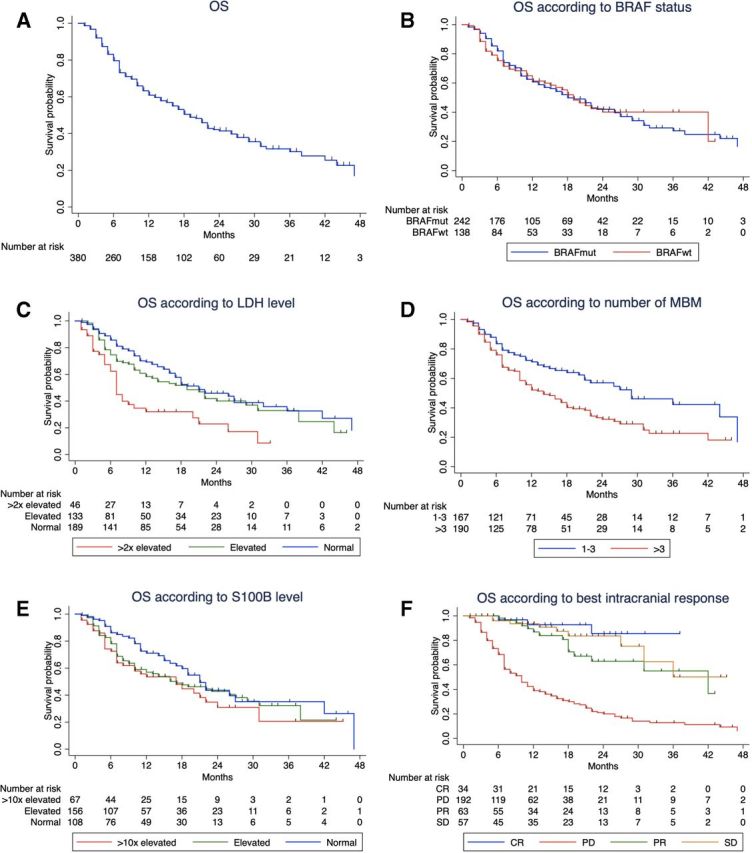

The mOS for the whole cohort was 19 months (95% CI: 15.9 to 22.0) and the median FU time was 18 months (IQR 9–28 months). The 1-year, 2-year and 3-year OS rates were 69%, 41.1% and 30.1%, respectively (table 3; figure 1A; 95% CI: 63.5 to 74.5; 34.9 to 47.9 and 22.2 to 37.9, respectively).

Table 3.

Median OS and 1-year, 2-year and 3-year OS rates

| mOS (months) (95% CI) | 1-year OS (%; 95% CI) |

2-year OS (%; 95% CI) |

3-year OS (%; 95% CI) |

|

| All patients | 19 (15.9 to 22.0) | 69 (63.5 to 74.5) | 41.1 (34.9 to 47.9) | 30.1 (22.2 to 37.9) |

| Number of MBM | ||||

| 1–3 | 29 (16.9 to 41.4) | 71.2 (63.6 to 78.8) | 57.0 (46.8 to 67.2) | 42.3 (28.6 to 56.0) |

| >3 | 14 (10.2 to 17.9) | 52.1 (44.3 to 59.9) | 32.2 (23.9 to 40.4) | 22.7 (13.5 to 31.9) |

| BRAF status | ||||

| BRAF wild type | 19 (14.9 to 23.0) | 61.3 (51.9 to 70.7) | 40.1 (28.3 to 51.9) | N/A |

| BRAF mutant | 18 (14.1 to 21.9) | 60.7 (53.8 to 67.6) | 42.0 (34.2 to 49.8) | 27.3 (18.1 to 36.5) |

| LDH level | ||||

| Normal | 21 (15.1 to 26.9) | 69.3 (61.6 to 76.7) | 45.9 (36.3 to 55.5) | 32.6 (20.4 to 44.6) |

| Elevated | 19 (12.8 to 25.1) | 58.4 (48.8 to 68.0) | 40.1 (29.1 to 51.1) | 32.9 (19.9 to 45.8) |

| 2×>ULN | 7 (6.1 to 7.9) | 32.1 (17.6 to 46.6) | 22.9 (8.0 to 37.8) | 8.6 (5.5 to 22.7) |

| S100B level | ||||

| Normal | 22 (18.2 to 25.8) | 78.4 (68.6 to 88.2) | 44.7 (30.8 to 58.6) | 36.1 (20.6 to 51.6) |

| Elevated | 17 (9.6 to 24.4) | 57.0 (48.2 to 65.8) | 42.8 (32.8 to 52.8) | 32.3 (20.5 to 44.6) |

| 10×>ULN | 17 (8.2 to 25.8) | 53.5 (40.4 to 66.6) | 30.9 (15.8 to 45.9) | 20.6 (1.2 to 40.0) |

| Best intracerebral response | ||||

| CR | Not reached | 92.7 (82.9 to 100) | 85.6 (69.3 to 100) | N/A |

| PR | 42 (22.6 to 61.4) | 86.9 (76.9 to 96.9) | 62.9 (46.0 to 79.8) | 55.1 (34.5 to 75.7) |

| SD | Not reached | 93.6 (86.5 to 100) | 83.6 (71.1 to 96.1) | 50.2 (19.0 to 81.4) |

| PD | 10 (16.7 to 23.3) | 39.0 (31.4 to 46.6) | 20.0 (13.1 to 26.9) | 12.8 (6.0 to 19.3) |

| CombiIT | ||||

| First line | 17 (10.7 to 23.9) | 56.4 (48.9 to 63.8) | 44.7 (35.9 to 53.5) | 27.9 (11.2 to 44.6) |

| Not first line | 21 (17.8 to 24.2) | 67.9 (59.9 to 75.9) | 41.9 (32.7 to 51.1) | 31.6 (21.8 to 41.4) |

| BRAF mutant patients | ||||

| First-line targeted therapy | 22 (17.2 to 26.77) | 65.6 (55.2 to 76) | 44.3 (34.5 to 57.7) | 32.0 (20 to 44) |

| First-line CombiIT | 16 (7 to 25) | 53.6 (43.2 to 64) | 42.9 (30.7 to 55.1) | N/A |

| BRAF wild-type patients | ||||

| First-line CombiIT | 21 (10.2 to 31.8) | 59.6 (52.6 to 73.4) | 47 (33.8 to 60.1) | 47 (33.8 to 60.1) |

| First-line not CombiIT | 19 (16.3 to 21.7) | 68.3 (50.1 to 74.2) | 31.9 (11.5 to 52.3) | 31.9 (11.5 to 52.3) |

| STR/surgery (at any time point) | ||||

| Yes | 24 (19.6 to 28.4) | 70.6 (63.7 to 77.5) | 49.5 (40.9 to 58.1) | 36.5 (26.3 to 46.7) |

| No | 16 (7.6 to 24.4) | 53.2 (41.0 to 65.4) | 40.9 (26.6 to 55.2) | N/A |

| WBRT | 8 (4.9 to 11.0) | 40.7 (28.4 to 53.0) | 20.8 (9.4 to 32.2) | 10.4 (1.4 to 22.2) |

| STR/surgery | ||||

| Upfront | 26 (21.1 to 30.9) | 72.5 (65.1 to 79.9) | 50.9 (41.3 to 60.5) | 39.5 (28.3 to 50.7) |

| Later | 16 (10.8 to 21.2) | 63.7 (47.6 to 79.8) | 44.3 (24.9 to 63.7) | 22.2 (1.5 to 45.9) |

| ECOG-PS | ||||

| 0 | 22 (16.4 to 27.6) | 65.7 (59.0 to 72.4) | 47.1 (39.1 to 55.1) | 36.4 (26.4 to 46.4) |

| 1 | 18 (7.3 to 28.7) | 52.3 (40.1 to 64.5) | 38.0 (34.1 to 519) | 22.2 (6.1 to 38.3) |

| >1 | 8 (7.3 to 17.1) | 49.3 (31.8 to 66.7) | 23.5 (5.5 to 41.5) | 5.9 (5.1 to 16.9) |

| Presence of symptomatic MBM | ||||

| No | 19 (10.7 to 27.2) | 62.5 (53.4 to 71.8) | 45.4 (34.6 to 56.2) | 35.1 (21.8 to 48.4) |

| Yes | 12 (7.0 to 17.0) | 46 (32.1 to 59.9) | 28.1 (13.8 to 42.4) | 15.0 (0 to 30.7) |

CombiIT, nivolumab plus ipilimumab; CR, complete response; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MBM, melanoma brain metastases; mOS, median overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; STR, stereotactic radiosurgery; ULN, upper level normal; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (A) and considering the different factors: (B) BRAF status; (C) LDH level; (D) number of melanoma brain metastases (MBM) at the time of therapy with nivolumab+ipilimumab; (E) protein S100B level; (F) best intracranial response. CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Figure 1B–E show the Kaplan-Meier OS curves considering BRAF mutation status, serum LDH level, number of MBM, protein S100B level, and online supplementary figure S2A–D show the Kaplan-Meier OS curves according to age groups, sex, ECOG-PS and presence of symptomatic MBM. The results shown are in line with what has been previously described in the univariate Cox regression analysis (table 2), that is, there is a statistically significant difference between the groups analyzed regarding serum LDH level (p<0.0001), number of MBM (p=0.001) and ECOG-PS (p<0.0001).

Stratifying for the best intracranial response (figure 1F), best OS was observed in patients with complete response (CR) and the difference between the subgroups with CR, partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) was statistically significant (p<0.0001). The mOS for patients with an intracranial CR or SD was not reached and for patients with PR and PD was 42 and 10 months, respectively (table 3; 95% CI: 22.6 to 61.4; 16.7 to 23.3, respectively). Patients achieving an intracranial CR had an improved 1-year OS rate of 92.7% compared with those with PD with a 1-year OS rate of only 39% (95% CI: 82.9 to 100; 31.4 to 46.6, respectively). Patients with SD showed favorable OS that was better than those with PR at 2 years and similar to PR at 3 years. The subgroups of patients with PR and SD did not differ significantly regarding serum LDH level, protein S100B, number of MBM, ECOG-PS or presence of extracerebral metastases.

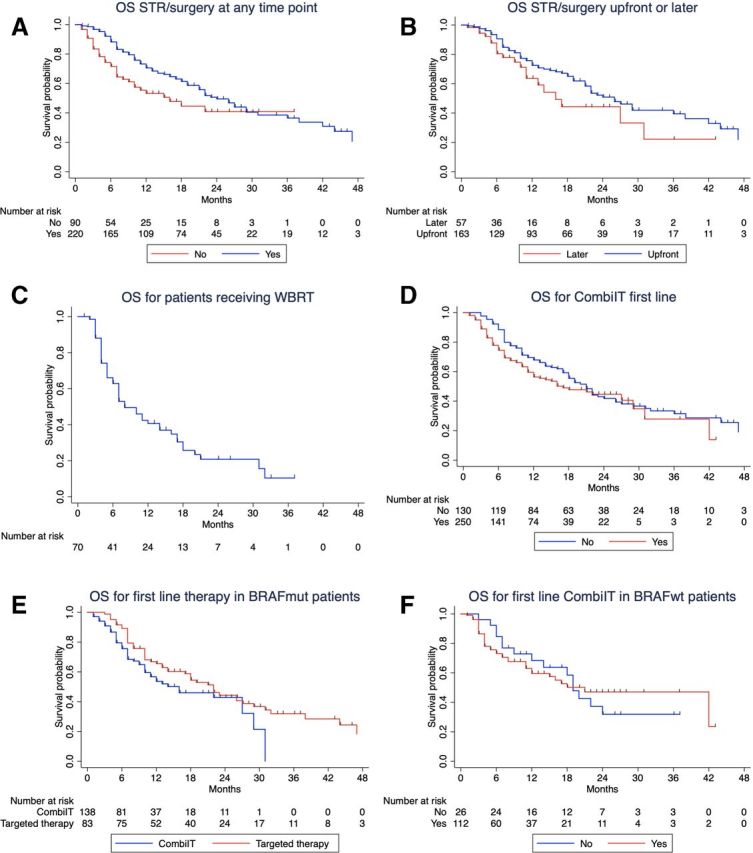

Local therapy (STR/surgery) also improved OS (table 3, figure 2A): patients who received local therapy (at any time point of the course of the disease) reached a mOS of 24 months compared with patients without local therapy with only 16 months (p=0.009; 95% CI: 19.6 to 28.4 and 7.6 to 24.4, respectively). There was no significant difference in terms of patients’ characteristics in these two groups, except for S100B level and presence of symptomatic MBM (online supplementary table S1). However, we need to acknowledge that information regarding the presence of symptomatic MBM was missing in approximately 50% of the patients.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (OS) according to the following factors: (A) local therapy (STR/surgery, stereotactic radiosurgery or surgery); (B) time of local therapy (before or after combined immunotherapy with nivolumab+ipilimumab); (C) for patients receiving whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT); (D) combined immunotherapy for melanoma brain metastasis (MBM) in first line or later; (E) first-line therapy in patients harboring a BRAF mutation and (F) combined immunotherapy first line or later in BRAF wild-type patients. Patients treated with WBRT were excluded from the analysis in figure 2A. Ten patients (4.5%) from the STR/surgery group (n=220) received only surgery. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis in figure 2B, four patients receiving STR/surgery before combined immunotherapy and two patients receiving STR/surgery after combined immunotherapy were treated with the two techniques in an interval of 2 weeks.

When analyzing the time point of local therapy (ie, before or after NIVO+IPI), we found no significant difference in terms of patients’ characteristics (online supplementary table S2) and the mOS was similar in the two subgroups (figure 2B; p=0.110). However, there seems to be a trend for a benefit of STR/surgery upfront (mOS=26 months vs 16 months; 95% CI: 21.1 to 30.9; 10.8 to 21.2, respectively). Patients who received WBRT had a mOS of 8 months (table 3, figure 2C; 95% CI: 4.9 to 11.0) and were analyzed separately.

No OS difference was observed for patients receiving first-line NIVO+IPI compared with those that received combined immunotherapy later (figure 2D; p=0.119). When looking at the patients’ characteristics from these two groups, there was a significant difference between them regarding age, BRAFV600 mutation status, number of MBM and treatment with local therapy (STR/surgery) at the time of starting NIVO+IPI (table 1). These differences might contribute for similar OS outcomes regardless of therapy line.

In the subgroup of patients with BRAFV600 mutation (242 patients), 83 received first-line treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors, 138 received first-line NIVO+IPI and all received combined immunotherapy for MBM in the course of the disease. There was no OS difference when comparing first-line targeted therapy with first-line combined immunotherapy (figure 2E; p=0.085). The line of treatment for combined immunotherapy (first-line or not first-line) had no effect on survival outcome in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma (figure 2F; p=0.996).

Regarding presence of symptomatic MBM, information was available for only 193 patients (online supplementary figure S2D), but there is a trend benefiting patients with asymptomatic MBM (p=0.065). However, if we consider only the patients that received first-line NIVO+IPI for MBM (n=137), the difference in OS between symptomatic and asymptomatic MBM is not significant (p=0.084; data not shown).

Safety

In the present cohort, a total of 236 (62%) patients were reported to have at least one immune-related adverse events (irAEs). In 142 (37%) patients, no irAEs were documented and there was no available information in 2 (1%) patients.

We found no difference (Pearson’s χ2 test) in terms of onset of irAEs in patients with 1–3 MBM compared with patients with >3 MBM (p=0.069). Regarding the onset of irAEs in patients who received STR/surgery versus those who did not receive STR/surgery, there was also no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.657). Finally, when analyzing the relation between receiving STR/surgery or not, and the interruption of therapy due to irAEs, we again found no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.913).

Discussion

The present study shows that combined immunotherapy with NIVO+IPI can result in improved survival of patients with MBM, comparable to results in other stage IV patients. This is particularly true if intracranial CR, PR or SD has been achieved. The type of intracranial response is a strong predictor for OS. In our cohort, the 2-year OS rates of patients with SD, PR and CR ranged from 63% to 86%, whereas patients with PD had a 2-year OS rate of only 20% (table 3). Similar favorable results have been reported in the ABC trial, a randomized phase II study of nivolumab or NIVO+IPI in patients with MBM.16 The 3-year intracranial PFS was above 90% for patients with asymptomatic, treatment-naïve MBM achieving an intracranial CR, and above 50% for patients with PR. We have no explanation why in our cohort patients with SD did better than patients with PR.

In our study, the 1-year and 2-year OS rate were 69% and 41%, respectively, in line with previous reports.9 10 In the already mentioned ABC trial, patients who received combined immunotherapy had a 1-year and 2-year OS rate of 63%16 and in the Checkmate-204 trial the reported 1-year OS rate was even higher (81.5%).10 The survival rates in these trials are higher than those reported in our cohort. Compared with the ABC trial and the Checkmate-204 trial, which included patients with asymptomatic MBM and treatment-naïve BRAF wild-type patients, 31% (60/193) of the patients in our trial had symptomatic MBM and 20% of the BRAF wild-type patients were pretreated. In the Checkmate-204 trial, 17% of the patients had received previous systemic therapy for MBM and 52% had only one MBM compared with 34% pretreated patients and 53% patients with more than three MBM in our cohort.

Two studies evaluating pembrolizumab in patients with MBM also reported similar outcomes.17 18 The first study evaluated treatment with pembrolizumab monotherapy in 23 patients with one or more asymptomatic and untreated MBM. With a longer follow-up of 38 months, the mOS time was 17 months (95% CI: 10 months to not reached) and the 2-year OS was 48%. These are in line with our results for patients who did not receive STR/surgery for whom the mOS was 16 months (95% CI: 7.6 to 24.4) and the 2-year OS rate was 41%. However, in this trial, only asymptomatic patients were included and 87% had <3 MBM, a population with potentially better outcome that the one included in our report. In the second study, Anderson et al reported the results of the combination from pembrolizumab and radiation therapy in 21 patients with MBM. Despite the low number of patients included, the percentage of lesions that had a CR (>30%), was higher than previously reported with systemic therapy or STR alone.

The combination of immunotherapy and local therapy with stereotactic irradiation or surgery improved patients’ survival compared with patients who only received NIVO+IPI. This benefit might be related to a synergic effect between radiotherapy and immunotherapy that has been demonstrated both in preclinical and clinical studies.19–23 The combination of radiation and immune checkpoint inhibitors seems to be effective both in the irradiated and non-irradiated lesions, and this effect might be associated with the activation of cytotoxic T-cells and reduction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells.18 24 25

The benefit of combining local and systemic therapy in MBM has been previously shown by our group and others, with mOS that range from 14 to 25 months and 1-year OS rates between 58% and 78% in the groups that received local and systemic therapy, clearly superior to the outcomes of patients receiving only systemic therapy (mOS between 6 and 13 months and 1-year OS rates ranging from 34% to 53%).14 15 26–33

In our study, the time point at which the patients received local therapy did not seem to play a significant role in OS: local therapy performed upfront or after initiation of NIVO+IPI resulted in similar OS rates, with a trend benefiting local therapy upfront (mOS 26 months vs 16 months). Different retrospective studies have also addressed this question, and, similar to our cohort, upfront local therapy seems to have better outcomes (mOS of 11–23 months in the group receiving local therapy upfront and 3–9 months in patients receiving local therapy after systemic therapy).34 35

There is still an ongoing debate whether some patients might be better served with systemic therapy alone, as we see very positive outcomes.9–11 36 Not applying local therapy reduces local complications, potential cognitive impairment and might be particularly adequate for patients with a low number of asymptomatic MBM. This question along with the best sequence regarding local therapy is being addressed in ongoing clinical trials, and in the future, we might be better equipped to decide which patients to treat with the different modalities.37 38

In this study, there was a high proportion of patients with BRAFV600-mutated melanoma (63%), but similar to other publications where this subgroup represents between 52% and 65% of the patients.14 15 26 28 Previously, it has been postulated that even in patients with BRAFV600-mutated MBM, first-line systemic treatment should consist of combined immunotherapy. Our analysis showed that there was no difference in OS of patients receiving first-line NIVO+IPI or first-line targeted therapy followed by combined immunotherapy (p=0.085). The two subgroups did not differ significantly (online supplementary table S4), except for the number of MBM, where a higher proportion of patients with >3 MBM received first-line targeted therapy (p=0.002). Our results in this subgroup need to be interpreted with caution since we have not included patients with BRAFV600 mutation who only received targeted therapy.

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, we identified LDH, S-100B, ECOG-PS and number of MBM as independent prognostic factors. These prognostic factors have already been described in previous analyses,8 14 39–41 but to the best of our knowledge, S100B has only been described as independent prognostic factor for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy in one monocentric study.42 It is interesting, however, that both tumor markers, LDH and S100B, remained independent prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis, suggesting that these non-invasive and easy to determine blood parameters can and should be used early in the course of the disease to inform about patients’ prognosis.

Regarding the presence of symptomatic MBM, there was no OS differences between patients with and without symptoms (p=0.065), but a trend can be seem showing that patients with symptomatic MBM have worse prognosis that those who are asymptomatic (1-year OS rate 46% and 63%, respectively). In other prospective studies investigating similar cohorts, the OS rate ranged from 66% at 6 months43 to 31% at 12 months.16 Unfortunately, information regarding the presence of symptomatic MBM is missing in approximately 50% of the patients in our study, and therefore, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from our data.

Strengths of this investigation are that data from 23 German-certified skin cancer centers with high standards for data quality were included. Three-hundred and eighty patients were analyzed which is thus far the largest published cohort of patients with MBM managed in a routine clinical setting. This high number of patients allowed us to perform subgroup analyses, with results of reasonable sensitivity. Furthermore, this study provides long-term follow-up data of patients with MBM covering a period of up to 18 months.

The study limitations are related to its retrospective design. Patients were included regardless of previous systemic and local therapies prior to the combined immunotherapy and thus some heterogeneity of the study population might have contributed to differences in survival outcomes observed in our cohort. The decision to offer local therapy or not was probably influenced by the number and size of MBM. Additionally, the maximum number of MBM considered to be treated individually by STR/surgery might vary between different centers. We have not evaluated intracranial toxicities. However, this aspect might have been considered when planning local therapy and targeted therapy in patients with BRAFV600-mutated melanoma, influencing the systemic therapy offered as well as the therapy sequence in this subgroup.

In conclusion, our study shows that treatment with NIVO+IPI, particularly in combination with STR/surgery improves survival of patients with MBM. Results presented herein also suggest that local therapy with STR/surgery either before or after starting combined immunotherapy might be advantageous to prolonging OS.

Footnotes

Twitter: @TeresaSAmaral

Contributors: Study concept: TA, TE, CG, LZ. Data collection: all authors. Data analysis: TA, TE, CG, LZ. Data interpretation: TA, RG, CB, ChP, TG, JH, FM, TE, CG, LZ. Writing: all authors. Final approval: all authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: TA: reports personal fees and travel grants from BMS, grants, personal fees and travel grants from Novartis, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, grants from Neracare, grants from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. FK: reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. CL: reports personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Biontech, personal fees from Sun Pharma, other from Kiowa Kirin, outside the submitted work. KK: reports grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Amgen, grants and personal fees from NeraCare, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Philogen, grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. PT: reports personal fees from BMS, Novartis, MSD, Pierre Fabre, CureVac and Roche, personal fees from BMS, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Merck Serono, Sanofi and Roche, non-financial support from BMS, Pierre Fabre and Roche, outside the submitted work. AG: reports personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. RG: reports honoraria: Almirall Hermal, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Incyte, Merck Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, SUN; research funding: Amgen, Johnson & Johnson, MerckSerono, Novartis, Pfizer; travel and accommodations: BMS, Merck Serono, Pierre Fabre, Roche, SUN, outside the submitted work. SH: reports grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work. JU: is on the advisory board or has received honoraria and travel support from Amgen, BMS, GSK, LeoPharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi outside the submitted work. CB: has been investigator of clinical trials sponsored by Amgen, Array Pharma, BMS, ImmunoCore, MSD, Novartis, Regeneron and Roche; has received speaker’s and/or consultant’s fees by Amgen, BMS, ImmunoCore, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and SunPharma, outside the submitted work. DR-S: reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, outside the submitted work. AK: reports advisory board honoraria from Novartis Pharma, Roche, travel grants from Amgen and BMS, personal fees from AbbVie and Medac Pharma, outside the submitted work. ChP: reports personal fees from BMS, MSD, Roche, Pierre Fabre, Novatris and SUNPharma for advisory roles during the conduct of the study. TG: reports receiving speakers and/or advisory board honoraria from BMS, Sanofi-Genzyme, MSD, Novartis Pharma, Roche, AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work. ClP: reports personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Merck Serono, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work. DD: reports consulting and speaking fees and/or payment of travel expenses/participation fees: Amgen, BMS, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, outside the submitted work. RH: served as consultant and/or has received speakers’ honoraria from Roche, BMS, MSD, Novartis and Pierre Fabre outside the submitted work. SE: reports advice and speakers’ honoraria from MSD, BMS, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Amgen, Novartis, LEO Pharm, ROCHE and Genzyme Corporation, outside the submitted work. JCH: reports personal fees and travel grants from BMS, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre and Sanofi, grants for scientific projects from BMS, personal fees for participation in advisory boards from MSD and Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work. FM: reports personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis, personal fees and non-financial support from Roche, personal fees from MSD, personal fees and non-financial support from BMS, personal fees and non-financial support from Pierre Fabre, outside the submitted work. TT: reports grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Roche, outside the submitted work. TE: reports personal fees from Amgen, grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pierre Fabre, grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. CG: reports grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Amgen, grants and personal fees from NeraCare, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Philogen, grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. LZ: served as consultant and/or has received honoraria from Roche, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, and travel support from MSD, BMS, Amgen, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi and Novartis, outside the submitted work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The current study was submitted and approved by the Ethics commission of the Eberhard′s Karls University Tuebingen (approval number: 766/2018BO2).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used according to the Ethics Commission vote and recommendations for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

References

- 1. Eigentler TK, Figl A, Krex D, et al. . Number of metastases, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, and type of treatment are prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases of malignant melanoma. Cancer 2011;117:1697–703. 10.1002/cncr.25631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Staudt M, Lasithiotakis K, Leiter U, et al. . Determinants of survival in patients with brain metastases from cutaneous melanoma. Br J Cancer 2010;102:1213–8. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Avril MF, Aamdal S, Grob JJ, et al. . Fotemustine compared with dacarbazine in patients with disseminated malignant melanoma: a phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1118–25. 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schadendorf D, Hauschild A, Ugurel S, et al. . Dose-Intensified bi-weekly temozolomide in patients with asymptomatic brain metastases from malignant melanoma: a phase II DeCOG/ADO study. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1592–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdl148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. . Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:472–92. 10.3322/caac.21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. . Five-Year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1535–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robert C, Grob JJ, Stroyakovskiy D, et al. . Five-Year outcomes with dabrafenib plus trametinib in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:626–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1904059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Franken MG, Leeneman B, Gheorghe M, et al. . A systematic literature review and network meta-analysis of effectiveness and safety outcomes in advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2019;123:58–71. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Long GV, Atkinson V, Lo S, et al. . Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: a multicentre randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:672–81. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30139-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, et al. . Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med 2018;379:722–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. . Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): a multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:863–73. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30429-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Long GV, Trefzer U, Davies MA, et al. . Dabrafenib in patients with Val600Glu or Val600Lys BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain (BREAK-MB): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:1087–95. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70431-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rulli E, Legramandi L, Salvati L, et al. . The impact of targeted therapies and immunotherapy in melanoma brain metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 2019;125:3776–89. 10.1002/cncr.32375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amaral T, Tampouri I, Eigentler T, et al. . Immunotherapy plus surgery/radiosurgery is associated with favorable survival in patients with melanoma brain metastasis. Immunotherapy 2019;11:297–309. 10.2217/imt-2018-0149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rauschenberg R, Bruns J, Brütting J, et al. . Impact of radiation, systemic therapy and treatment sequencing on survival of patients with melanoma brain metastases. Eur J Cancer 2019;110:11–20. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Long VGA GV, Lo S, Sandhu SK, et al. . Long-term Outcomes from the Randomized Ph 2 Study of Nivolumab or Nivo+Ipilimumab in Patients with Melanoma Brain Metastases - The ABC trial. Ann Oncol 2019;30:v533–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kluger HM, Chiang V, Mahajan A, et al. . Long-Term survival of patients with melanoma with active brain metastases treated with pembrolizumab on a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:52–60. 10.1200/JCO.18.00204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson ES, Postow MA, Wolchok JD, et al. . Melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery and concurrent pembrolizumab display marked regression; efficacy and safety of combined treatment. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:76. 10.1186/s40425-017-0282-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dovedi SJ, Cheadle EJ, Popple AL, et al. . Fractionated radiation therapy stimulates antitumor immunity mediated by both resident and infiltrating polyclonal T-cell populations when combined with PD-1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5514–26. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharabi AB, Nirschl CJ, Kochel CM, et al. . Stereotactic radiation therapy augments antigen-specific PD-1-Mediated antitumor immune responses via cross-presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:345–55. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roger A, Finet A, Boru B, et al. . Efficacy of combined hypo-fractionated radiotherapy and anti-PD-1 monotherapy in difficult-to-treat advanced melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1442166 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1442166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chandra RA, Wilhite TJ, Balboni TA, et al. . A systematic evaluation of abscopal responses following radiotherapy in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1046028 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1046028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saiag P, Baghad B, Fort M, et al. . Efficacy of hypofractionated radiotherapy (RX) in melanoma patients who failed anti-PD-1 monotherapy: assessing the abscopal effect. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:9537 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, et al. . Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 2015;520:373–7. 10.1038/nature14292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ngiow SF, McArthur GA, Smyth MJ. Radiotherapy complements immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Cell 2015;27:437–8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tétu P, Allayous C, Oriano B, et al. . Impact of radiotherapy administered simultaneously with systemic treatment in patients with melanoma brain metastases within MelBase, a French multicentric prospective cohort. Eur J Cancer 2019;112:38–46. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stera S, Balermpas P, Blanck O, et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors or kinase inhibitors for patients with multiple brain metastases of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res 2019;29:187–95. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Minniti G, Anzellini D, Reverberi C, et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery combined with nivolumab or ipilimumab for patients with melanoma brain metastases: evaluation of brain control and toxicity. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:102. 10.1186/s40425-019-0588-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tio M, Wang X, Carlino MS, et al. . Survival and prognostic factors for patients with melanoma brain metastases in the era of modern systemic therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2018;31:509–15. 10.1111/pcmr.12682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ahmed KA, Stallworth DG, Kim Y, et al. . Clinical outcomes of melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiation and anti-PD-1 therapy. Annals of Oncology 2016;27:434–41. 10.1093/annonc/mdv622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nardin C, Mateus C, Texier M, et al. . Tolerance and outcomes of stereotactic radiosurgery combined with anti-programmed cell death-1 (pembrolizumab) for melanoma brain metastases. Melanoma Res 2018;28:111–9. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen L, Douglass J, Kleinberg L, et al. . Concurrent immune checkpoint inhibitors and stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases in non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma. International Journal of radiation oncology, biology. Physics 2018;100:916–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qian JM, Yu JB, Kluger HM, et al. . Timing and type of immune checkpoint therapy affect the early radiographic response of melanoma brain metastases to stereotactic radiosurgery. Cancer 2016;122:3051–8. 10.1002/cncr.30138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmidberger H, Rapp M, Ebersberger A, et al. . Long-Term survival of patients after ipilimumab and hypofractionated brain radiotherapy for brain metastases of malignant melanoma: sequence matters. Strahlenther Onkol 2018;194:1144–51. 10.1007/s00066-018-1356-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alvarez-Breckenridge C, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gill CM, et al. . Upfront surgical resection of melanoma brain metastases provides a bridge toward Immunotherapy-Mediated systemic control. Oncologist 2019;24:671–9. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tawbi HA, Boutros C, Kok D, et al. . New era in the management of melanoma brain metastases. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:741–50. 10.1200/EDBK_200819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gonzalez M, Hong AM, Carlino MS, et al. . A phase II, open label, randomized controlled trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab with stereotactic radiotherapy versus ipilimumab plus nivolumab alone in patients with melanoma brain metastases (ABC-X trial). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:TPS9600–TPS. 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.TPS9600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stereotactic radiosurgery added to binimetinib and Encorafenib in patients with BRAFV600 melanoma with brain metastasis (BECOME-MB), 2019. Available: https://clinicaltrialsgov/ct2/show/NCT04074096

- 39. Choong ES, Lo S, Drummond M, et al. . Survival of patients with melanoma brain metastasis treated with stereotactic radiosurgery and active systemic drug therapies. Eur J Cancer 2017;75:169–78. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. da Silva IP, Lo S, Carlino MS, et al. . Clinical factors and overall survival (OS) associated with patterns of metastases (Mets) in melanoma patients (PTS). Ann Oncol 2019;30:v540. 10.1093/annonc/mdz255.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Șuteu P, Todor N, Ignat R-M, et al. . Clinical prognostic factors associated with survival and a survival score for patients with brain metastases. Future Oncol 2019;15:2619–34. 10.2217/fon-2019-0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gambichler T, Brown V, Steuke A-K, et al. . Baseline laboratory parameters predicting clinical outcome in melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab: a single-centre analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32:972–7. 10.1111/jdv.14629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tawbi HA-H, Forsyth PAJ, Hodi FS, et al. . Efficacy and safety of the combination of nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) in patients with symptomatic melanoma brain metastases (CheckMate 204). J Clin Oncol 2019;37:9501 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2019-000333supp001.pdf (362KB, pdf)