Abstract

Exposure to urban ambient particulate matter (PM) is associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease and accelerated cognitive decline in normal aging. Assessment of the neurotoxic effects caused by urban PM is complicated by variations of composition from source, location, and season. We compared several in vitro cell-based assays in relation to their in vivo neurotoxicity for NF-κB transcriptional activation, nitric oxide induction, and lipid peroxidation. These studies compared batches of nPM, a nanosized subfraction of PM2.5, extracted as an aqueous suspension, used in prior studies. In vitro activities were compared with in vivo responses of mice chronically exposed to the same batch of nPM.

The potency of nPM varied widely between batches for NF-κB activation, analyzed with an NF-κB reporter in human monocytes. Three independently collected batches of nPM had corresponding differences to responses of mouse cerebral cortex to chronic nPM inhalation, for levels of induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, microglial activation (Iba1), and soluble Aβ40 & −42 peptides. The in vitro responses of BV2 microglia for NO-production and lipid peroxidation also differed by nPM batch, but did not correlate with in vivo responses. These data confirm that batches of nPM can differ widely in toxicity. The in vitro NF-κB reporter assay offers a simple, high throughput screening method to predict the in vivo neurotoxic effects of nPM exposure.

Keywords: Air pollution, Particulate matter, Ultrafine particles, NF-κB, Inflammation, Neurotoxicity, In vitro screening

1. Introduction

Epidemiological studies consistently associate exposure to urban ambient air pollution particulate matter (PM) with accelerated cognitive aging and increased risk of Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders [1–5]. Correspondingly, rodent air pollution exposure models show cognitive impairments, brain inflammation, loss of CA1 synapses, decreased glutamate receptor subunit GluR1 receptor, and increased Aβ oligomers [3,6–8].

Ambient air pollution is globally monitored by the WHO as PM2.5 (aerodynamic diameter of particles below 2.5 μm) [9]. The epidemiological associations of PM2.5 with aging and diseases are based mainly on mass concentration μg/m3, with little consideration of chemical composition. However, ambient urban PM is a heterogeneous mixture of particles with different sizes that vary widely in chemical composition. Moreover, PM2.5 bioactivities depend on how active chemicals are distributed on particle surfaces. The composition varies greatly among batches due to the variety of local sources, as well as daily variations in temperature, sunlight, humidity, among other environmental factors, [10–14].

Several studies tried to predict PM toxicity in populations by composition and oxidative activities in cell-free systems [15,16]. The weak correlations of biochemical assays with epidemiological and rodent responses [17] has stimulated the development of in vitro assays that may predict in vivo responses; these assays include for mutagenicity [18], oxidative potential [16], cytotoxicity [19] and cytokine production [19–23].

Inflammation is induced in rodent brains by chronic exposure to air pollution PM [3,6–8], and oxidative stress is postulated to underlie the neurotoxicity of ambient PM2.5 [24]. Therefore, we assessed the activation of NF-κB,a master transcription factor in pro-inflammatory responses [25], for comparison with lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide (NO) production in cell-based assays. We tested two forms of PM collected at different times near an urban highway in Los Angeles: PM2.5 collected directly as an aqueous slurry (sPM), and nPM, a nano-scaled subfraction of PM2.5 (i.e., ultrafine PM), collected on filters, and eluted by sonication. We also examined diesel exhaust particle (DEP) that is widely used to model PM for air pollution [26]. We showed wide differences on nPM batches for NF-κB activation, lipid peroxidation, NO production. The in vitro potency of NF-κB activation by nPM strongly predicted in vivo neurotoxic responses.

2. Results

2.1. Urban ambient PM induced NF-κB activation

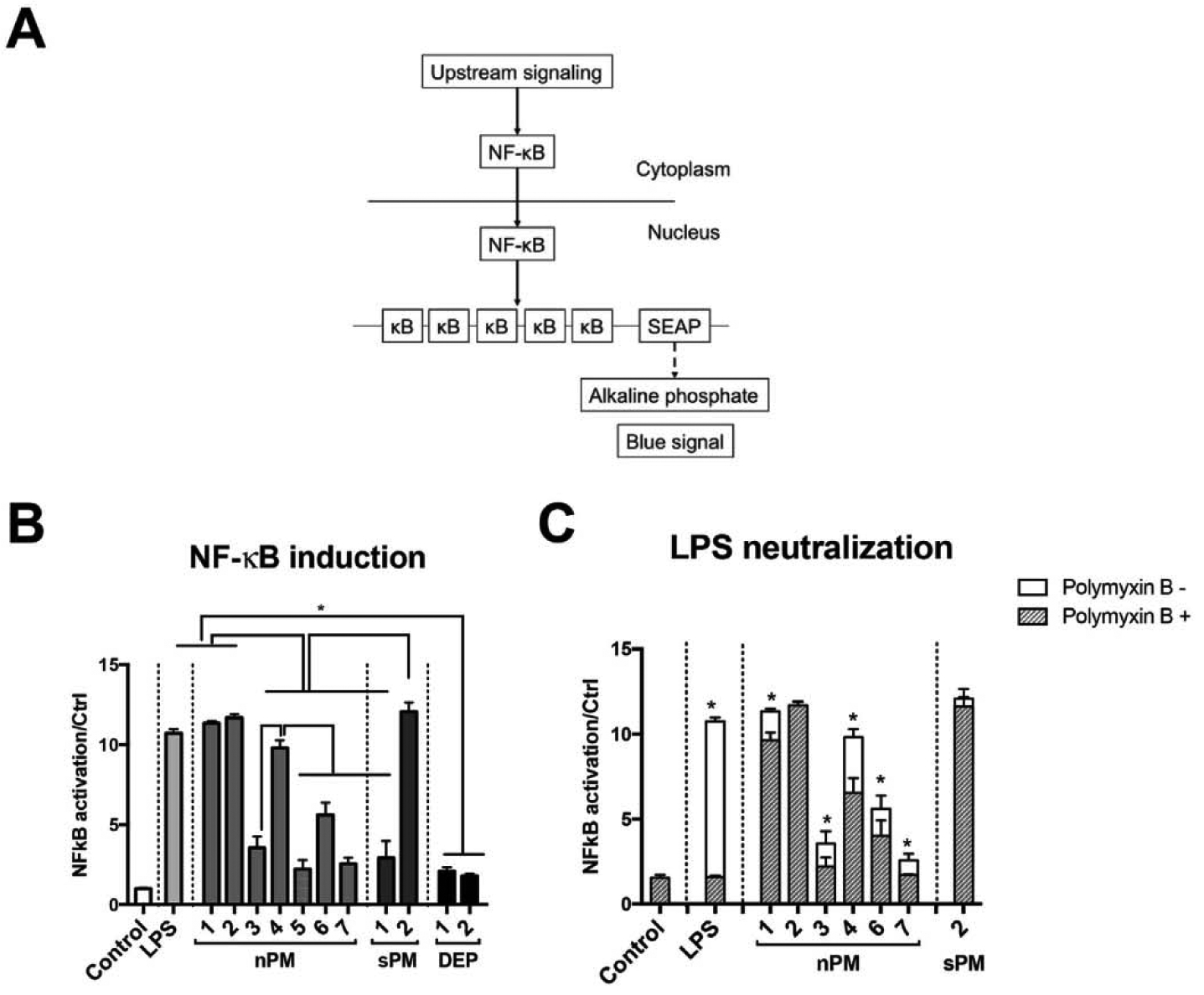

The potency of nPM (PM with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 0.25 μm) and sPM (slurry PM with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) for activating NF-κB signaling was assayed with human THP1 monocytes transfected with a NF-κB reporter (THP1-Blue monocytes). The reporter is driven by IκB cis elements (NF-κB binding sites) that increase secretion of embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) into cell media (Fig. 1A). At 5 μg/ml, the maximal NF-κB induction for several batches was 10-fold or more above control (Fig. 1B). The batches of nPM and sPM differed 4-fold in NF-κB activation. DEP had weaker activity by mass, inducing NF-κB by 2-fold at 100 μg/ml (Fig. 1B), but not at 5 μg/ml (not shown).

Fig. 1.

NF-κB activation by air pollution PMs. (A) Schema of NF-κB activation in the THP1-Blue monocyte assay; (B) NF-κB activation by 24 h (nPM and sPM, 5 μg/ml; DEP, 100 μg/ml; LPS, 10 ng/ml). (C) LPS neutralization by pretreatment with polymyxin B (10 ng/ml, 20 min) before NF-κB activation by nPM or sPM (5 μg/ml/24 h). * Adjusted p-value < 0.05, N = 4.

Since lipopolysaccharide can activate NF-κB (Fig. 1B), we examined its possible contribution to NF-κB activation by nPM. Neutralization of LPS activity by pretreatment with polymyxin B attenuated nPM-induced NF-κB activation by 10–30%, depending on the batch (Fig. 1C); batches nPM-2 and sPM-2 retained activity after polymyxin treatment. Polymyxin B (PMB) is a cationic polypeptide that binds the negatively charged lipid A, the toxic component of LPS, thereby neutralizing its activity by reducing its binding to the LPS receptor TLR4 [27]. Thus, these data suggest that LPS carried by nPM only partly contributes to its NF-κB activation.

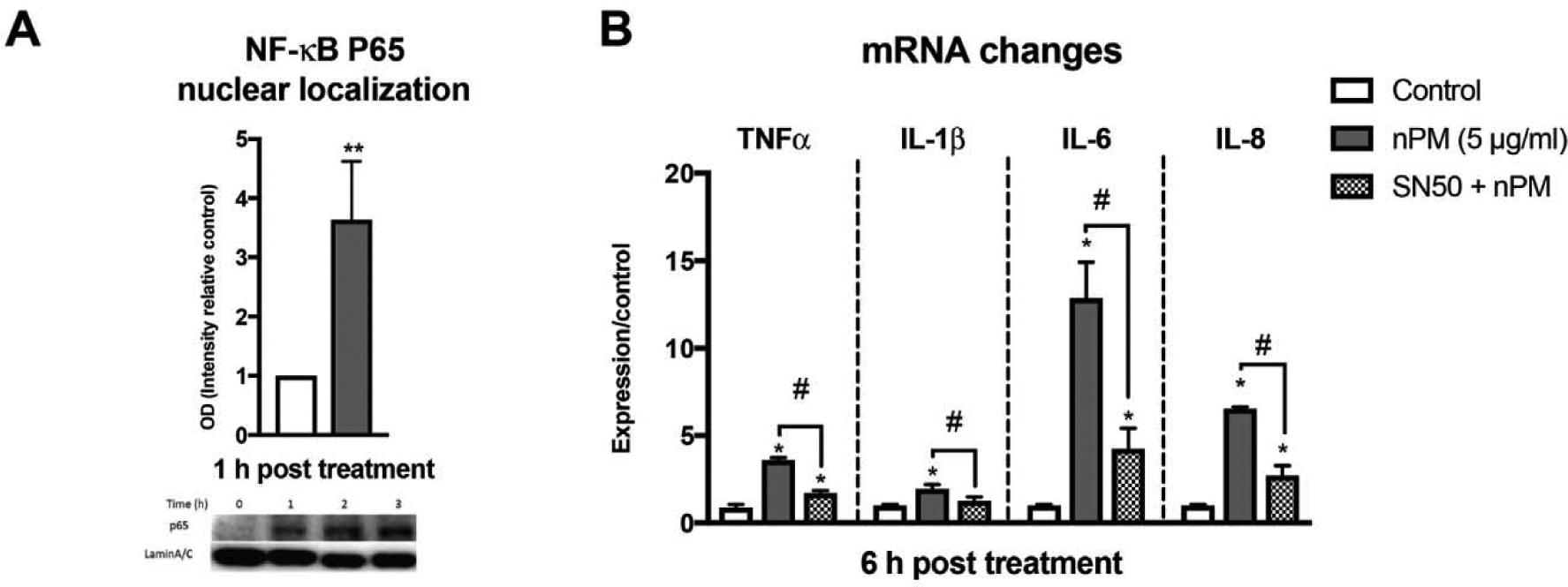

To further analyze NF-κB activation, we showed increased nuclear levels of the NF-κBp65 subunit (Fig. 2A). Corresponding to NF-κB activation, nPM induced cytokines TNF-α, IL-lβ, IL-6 and IL-8 (Fig. 2B). The link of cytokine responses to NF-κB induction was shown by SN50, a specific NF-κB inhibitor, which suppressed cytokine induction by 65% (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

nPM induced cytokines through NF-κB activation in THP1 monocytes. (A) nPM increased nuclear NF-κB p65 (Western blot) by 5 μg/ml nPM (B) Cytokine induction by nPM (RT-PCR) was suppressed by pretreatment with 40 μg/ml of SN50, a NF-κB inhibitor. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control, #, P < 0.05, nPM alone, N = 4.

2.2. Urban ambient PM induced nitric oxide (NO) production by microglia

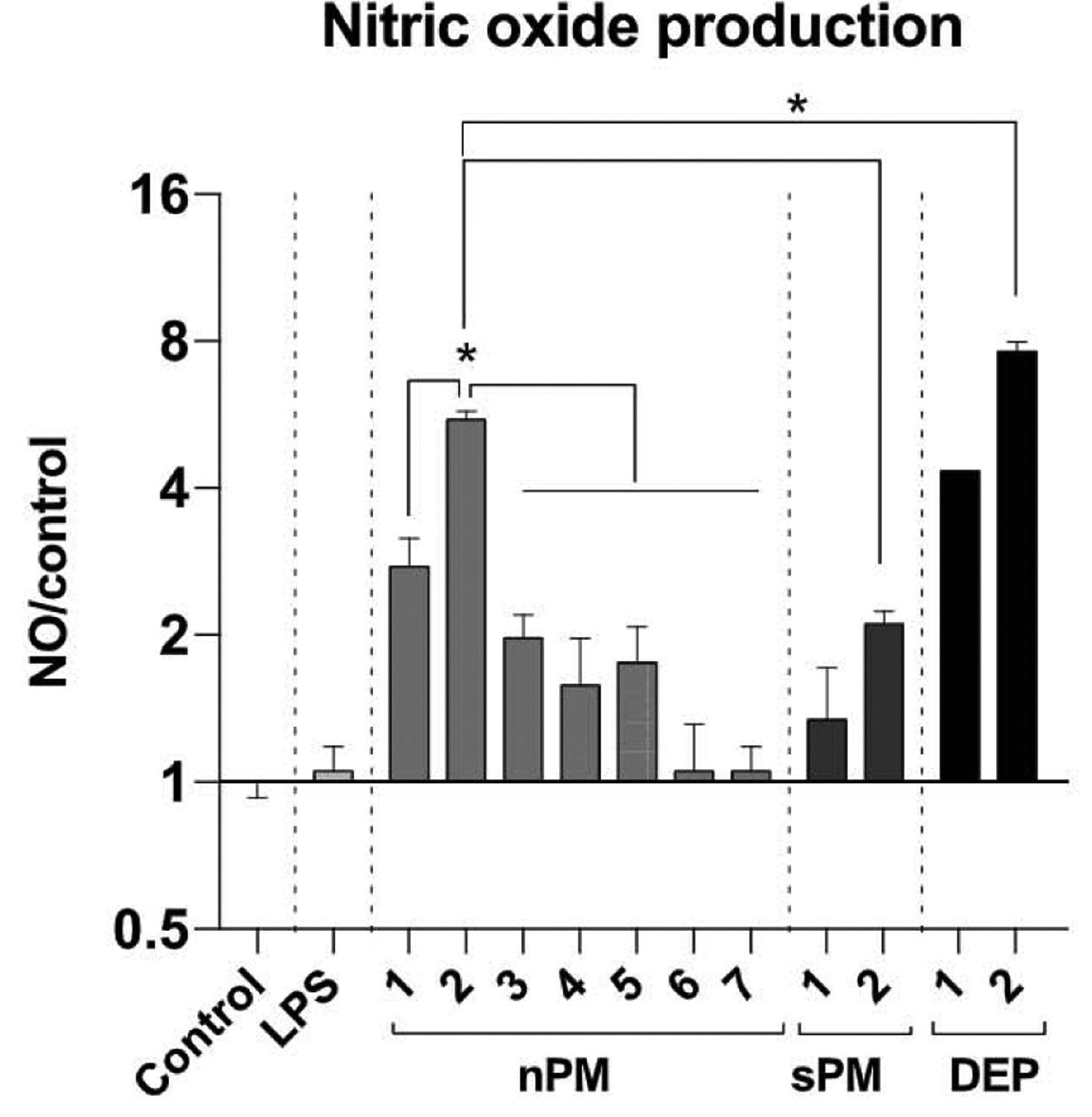

NO production was assayed in BV2 microglia (10 μg/ml for 6 h of nPM, sPM or DEP), because THP1 cells did not respond with NO induction (data not shown), consistent with prior finding [28]. The nPM and sPM batches differed widely in NO induction (Fig. 3), ranging from no induction (nPM-7) to 8-fold induction (DEP-2), over controls. The DEP induced slightly more NO than nPM at the same dose after 6 h (Figs. 3) and 24 h (not shown).

Fig. 3.

NO induction by urban PMs. BV2 cells, a mouse microglia cell line, were exposed to various PMs (nPM, sPM, DEP: 10 μg/ml) or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 6 h; nitrite/nitrate in media was assayed by Greiss reagent. * Adjusted p-value < 0.05, N = 4.

2.3. Urban ambient PM caused lipid peroxidation

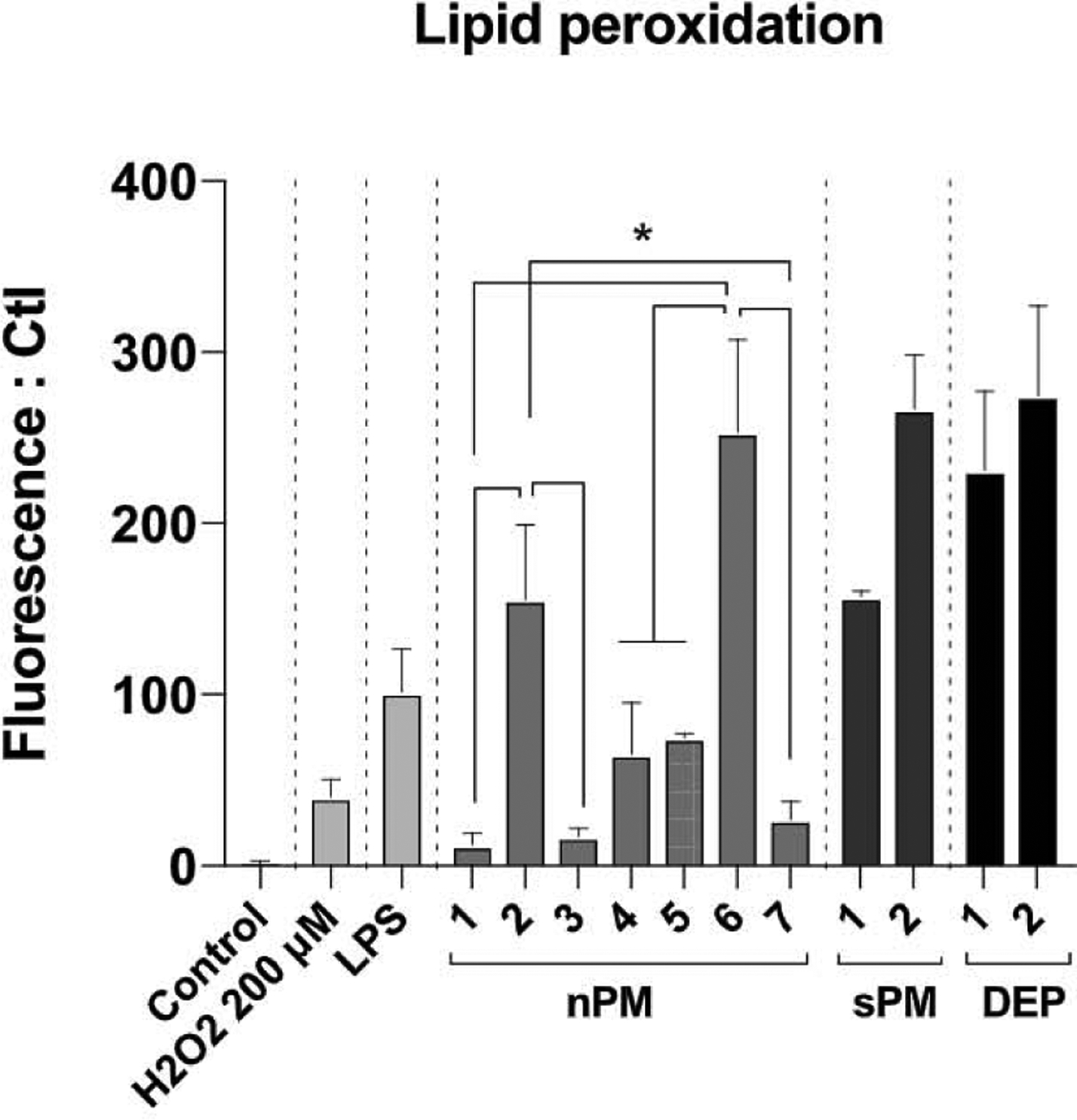

Peroxidation of lipids (fatty acid moieties) in the plasma membrane results from direct action of PM components, or secondarily from oxidants generated by cells interacting with PM. We assayed fluorescence of DPPP (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) for lipid peroxidation in human THP1 monocytes. Pre-incubation with DPPP embeds DPPP into plasma membranes [29], where it can be oxidized to the fluorescent product, DPPP oxide [30]. Again, we observed major batch differences at 5 μg/ml (Fig. 4), with lipid peroxidation ranging from 2-fold (nPM-1) to 12-fold (sPM-2) above vehicle control. Both batches of DEP had activity equivalent to the most active nPM/sPM batches.

Fig. 4.

Lipid peroxidation potency measured by DPPP assay. After incubation with DPPP (4.5 μM/15min), THP1-Blue cells were exposed to air pollution PM (nPM, sPM, DEP: 10 μg/ml), LPS (10 μg/ml), or H2O2 (200 μM) for 20 min, and fluorescence was measured (excitation, 351 nm; emission, 380 nm). * p-value < 0.05, N = 4.

2.4. Comparisons of in vitro potency to induce NF-κB, NO, and lipid peroxidation

The levels of induction for NF-κB, NO, and lipid peroxidation did not correlate significantly by batch at p < 0.05 (Fig. S1), while there was a marginal correlation between NF-κB activation and NO production (p = 0.08). These data suggest that batch differences of in vitro cellular responses arise from independent processes from undefined compositional differences between air pollution batches.

In vivo neurotoxic effects are associated with in vitro NF-κB activity of PM.

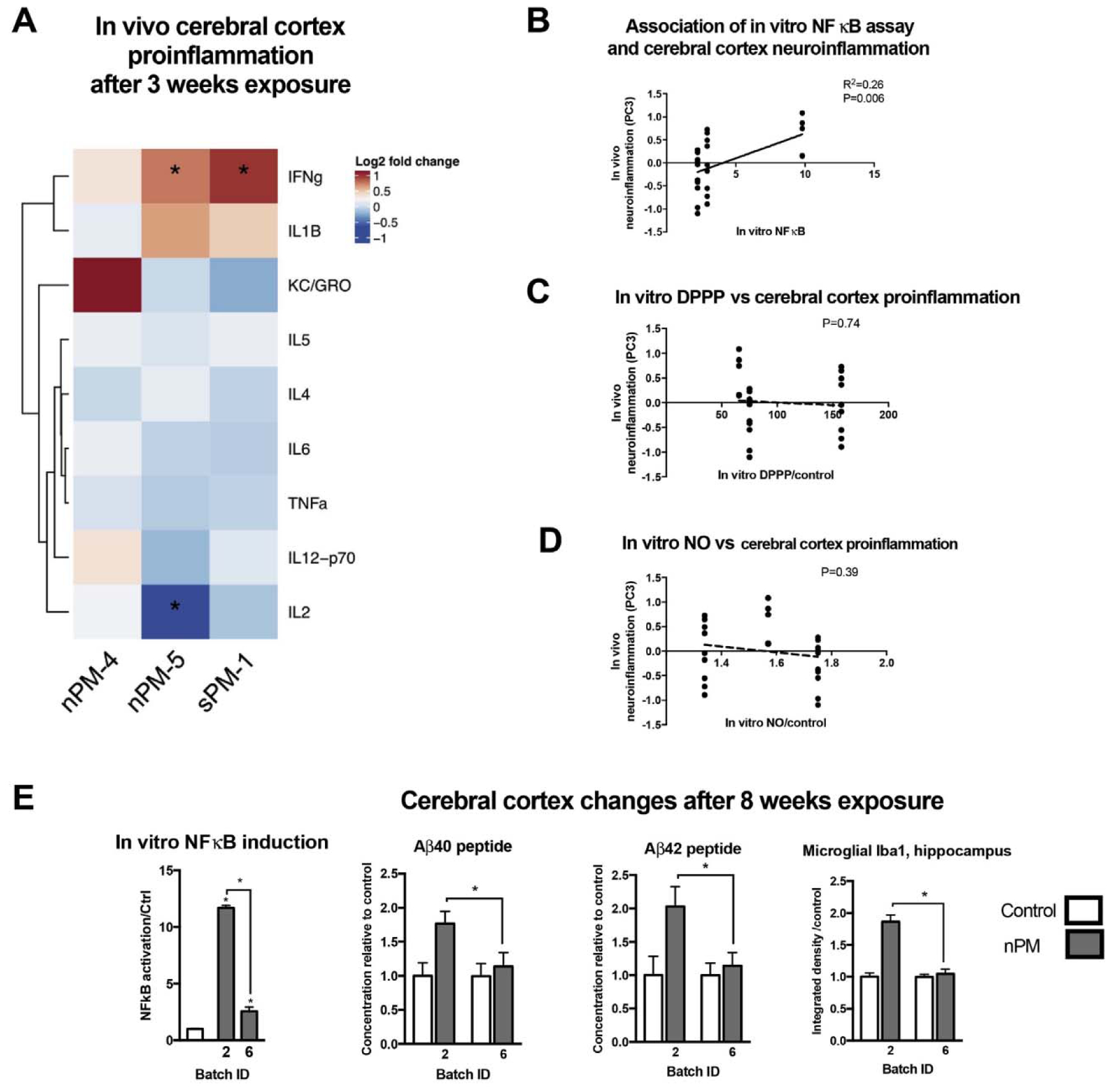

To examine if in vitro activity can predict in vivo responses, we exposed the mice to batches of urban nPM and sPM used for the in vitro assays: nPM-2, 4, 5, and 6, and sPM-1, which differed in NF-κB activation (Fig. 1A). After 3 weeks exposure, nPM-4, nPM-5, and sPM-1 induced cerebral cortex responses, including increased IFNγ and decreased IL2 (protein level measured by ELISA), with the magnitude differing by batch (Fig. 5A). These batches were collected at the same site, but at different times (see Methods, Table 1).

Fig. 5.

In vivo neurotoxic responses of nPM paralleled in vitro NF-κB induction activity. Young male mice were exposed for 3 or 8 weeks to nPM batches with different in vitro NF-κB activity for neurotoxic responses. A) Inflammatory cytokines after 3 weeks of exposure to 300 μg/m3 of PM0.2. Heatmap shows the fold changes of inflammatory cytokines in mice exposed to particles vs controls exposed to filtered air. B) In vitro NF-κB activation potency of PM was associated with the variance of cerebral cortex inflammatory responses. Principal component analysis of the 9 inflammatory cytokines was calculated for each mouse. In vitro NF-κB response was associated with PC3 that explained 17% of the variance brain inflammatory response. Cerebral cortex inflammatory profile of mice exposed to different batches of nPM or sPM did not correlate with in vitro (C) lipid peroxidation or (D) NO production. E) nPM with stronger NF-κB activation in vitro caused more increase in cerebral cortex amyloid-β40 &-42 peptides and hippocampal Iba1. Mean ± SEM. * adjusted P-values < 0.05. N = 5–10/group.

Table 1.

PM samples in this study.

| Extraction method | Sample ID | Collection Date(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Water-extracted (nPM) | 1 | Apr–Jun2016 |

| 2 | June–Aug 2016 | |

| 3 | May–Sep2016 | |

| 4 | Nov2016–Jan2017 | |

| 5 | May–Jun2017 | |

| 6 | Jan–Mar 2018 | |

| 7 | May–July2018 | |

| Direct suspension (sPM) | 1 | May–Jun2017 |

| 2 | Mar 2019 | |

| Diesel exhaust particles (DEP) | 1 | |

| 2 |

Principal components (PC) of responses were calculated for each mouse based on the changes of 9 inflammatory cytokines in the cerebral cortex. PC is considered as a latent variable of inflammation and represents a linear combination of the changes of the 9 cytokines. The NF-κB responses in vitro were significantly associated with PC3, explaining 17% of in vivo differences by batch (Fig. 5B). In contrast, lipid peroxidation and NO production were poorly correlated with in vivo responses (Fig. 5C and D). This suggests that PM potency of NF-κB activation could predict the long-term neurotoxic trajectories of the exposure.

The role of NF-κB was further tested by examining in vivo neurotoxic responses of mice exposed to nPMs with different in vitro NF-κB activation potency for 8 weeks. Exposure to nPM-2 that induced NF-κB in vitro by 12-fold also increased cerebral cortex soluble Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides, and hippocampal Iba1. In contrast, exposure to nPM-6, which induced NF-κB activity by 5-fold at the same dose, did not alter soluble Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides, and hippocampal Iba1 (Fig. 5E).

Since oxidative stress is postulated in mechanisms of air pollution-caused neurotoxicity [24], we assayed protein adducts of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), an established marker of oxidative stress produced by lipid peroxidation [31]. HNE-protein adducts did not change in cerebral cortex and hippocampus of mice exposed to either nPM batch for 3 or 8 weeks (data not shown).

2.5. Chemical composition of nPM and sPM batches

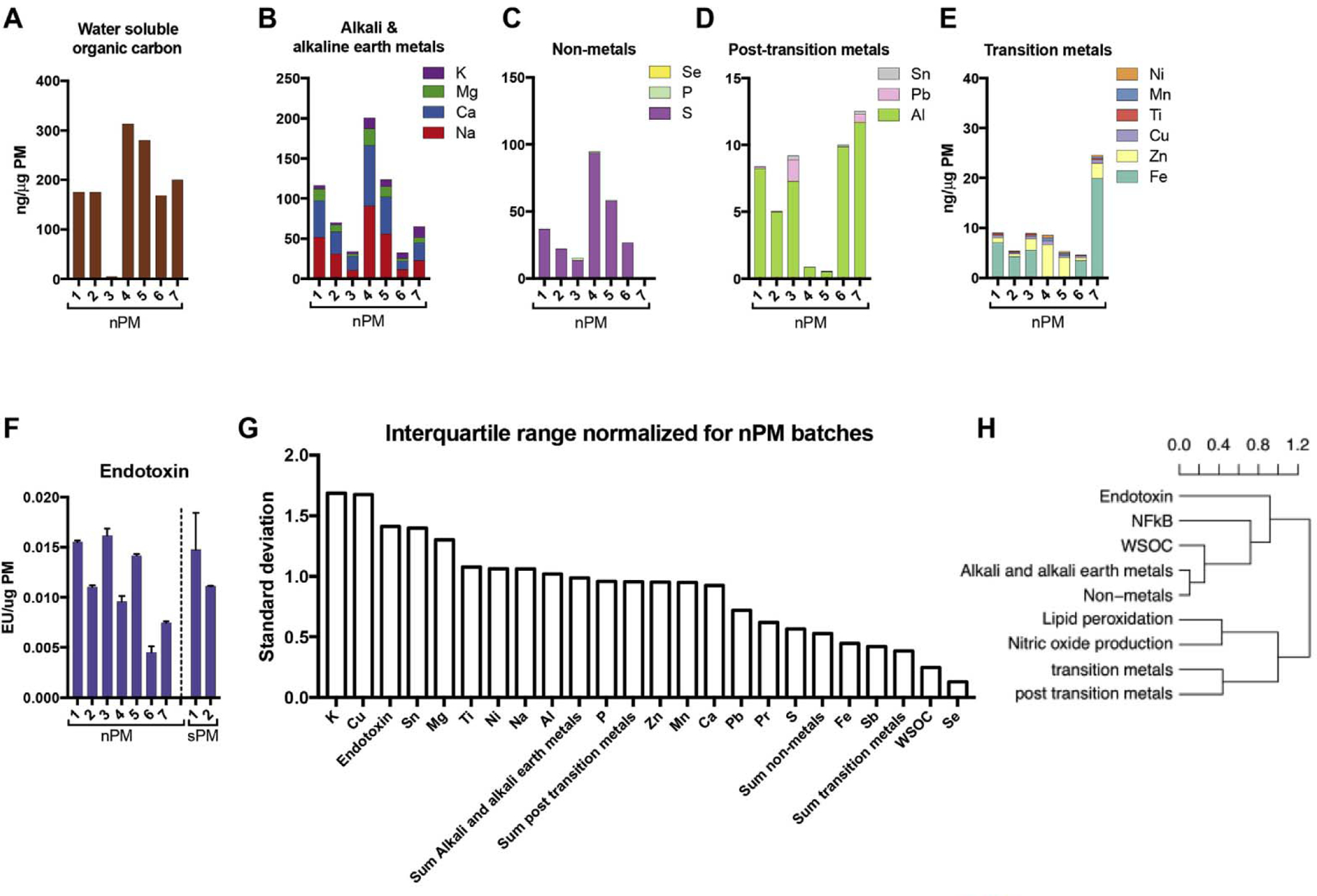

We examined the chemical composition of different batches for clues to explain the many-fold differences in activity. Metals, inorganic elements, water-soluble organic carbons (WSOC), and LPS were assayed in 7 batches of nPM and 2 batches of sPM, each collected at different times from the same site. The chemical composition varied greatly among the batches (Fig. 6), e.g. for nPM, iron varied 80-fold, and WSOC up to 300-fold. The components with highest variance were LPS, and alkali and alkaline-earth metals.

Fig. 6.

Chemical composition varied among nPM batches collected from the same site at different times (Methods, Table 1). A) Water soluble organic carbons (WSOC); B) Alkali and alkaline-earth metals; C) Non-metals; and D) Post transition metals; E) Transition metals; F) endotoxin [32]; G) Normalized interquartile range of components and metal categories in nPM batches, showing magnitude of variation in different components. H) Hierarchical clustering of biological responses and chemical components of nPM batches, showing the degree of correlation. The dissimilarity matrix was calculated from Pearson correlation; clustering used average linkage method, which calculates the mean distance between elements of each cluster for further merging and degree of correlation.

The nPM components associating with in vitro biological responses were identified by hierarchical clustering, using a dissimilarity matrix (generated from pairwise Pearson correlation) of biological responses and chemical subgroups of different nPM batches. This statistical method clusters objects by their degree of association (Fig. 6H). Among the analyzed particle components, LPS and WSOC had higher correlation with NF-κB activation than other components. The contribution of LPS to NF-κB activation varied from 0 to 30%, depending on the nPM batch. Weak associations were found between nPM components and lipid peroxidation or NO production (Fig. 6H). These data suggest that bulk chemical composition assay may not reliably predict the bioactivities of urban ambient PM.

3. Discussion

Batches of urban ambient PM had wide differences of NF-κB activation in a cell-based assay that correlated best with in vivo neurotoxicity. To our knowledge this is the first attempt to explore in vitro cell-based assays to predict particle-caused in vivo neurotoxic effects. Our recent review [17] discussed how epidemiologic and animal studies using ambient PM exposures fail to show correlations between bulk composition and in vitro oxidative potential and neurotoxicity.

For cell-based assays, we selected a human monocyte cell line (THP1 cells) to assess the pro-inflammatory potency and oxidative potential of PMs. Monocytes and macrophages are major cells that scavenge particles and produce inflammatory mediators in the body. The THP1 monocytes are widely used to study inflammatory responses. Compared to human bronchial epithelial cells and THP1-derived macrophages, the THP1 monocytes had stronger pro-inflammatory responses to nPM for NF-κB activation and induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (data not shown). For NO production, we assayed microglia, the resident immune cell type in brain. NO production is increased in BV2 microglia by PM2.5 [33]. Most comparisons of cell-based and animal responses have focused on acute pulmonary toxicity of particle exposure, using macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells, which are directly contacted by inhaled PM [19–23]. There is considerable cell-type specificity for mechanisms of phagocytosis and response to PM [34,35].

The inflammatory potency was assayed by NF-κB, a master transcription factor that regulates the induction of inflammatory mediators by air pollution PM (Fig. 1). Compared to assessing mRNA or protein of inflammatory mediators, this NF-κB reporter assay is more accurate, faster, and cost saving. NF-κB activation occurs in inflammatory responses common to all cells, whereas some pro-inflammatory mediators vary by cell type and animal species.

Membrane oxidation was assessed as lipid peroxidation in THP1 monocytes by the DPPP assay, which measures combined effects of the interaction of PM with extracellular molecules, the cell membrane, and the surface chemistry of PMs. The DPPP assay minimizes confounds of other methods based on the oxidation of dithiothreitol, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein and other fluorescent dyes by particles in a test tube [17]. NO production was measured in BV2 microglia using Greiss assay [55], a simple, fast and widely used assay in NO studies. BV2 microglia were chosen for this assay because PM-mediated NO production was not detected in THP1 monocytes and because microglia are a major source of NO in the brain [36] and NO production was induced by urban ambient PM in BV2 microglia [33]. For both lipid peroxidation and NO, DEP had activity equivalent to the most active nPM/sPM batches, consistent with its in vivo neuroinflammatory activity following gestational exposure [26].

In vivo neurotoxic effects were assessed by cytokines (Fig. 5A) [7,37,38], microglial activation (Iba1) [37–39], and a neurodegenerative peptide (Aβ40/42), which are increased in mouse brain by chronic exposure to nPM [3,40–42].

As expected, the current data confirm that urban PM samples can vary widely in bioactivities relevant to neurotoxicity for NF-κB activation, lipid peroxidation, and NO-production (Figs. 1, 3 and 4), and for in vivo neurotoxic responses (Fig. 5). This unequal bioactivity/toxicity of particles collected from different sources, sites, and/or time has been observed by many groups [43–52]. It is generally thought that varying toxicity is due to composition differences [10–14] that alter particle-cell interaction, phagocytosis, and subsequent responses [34,35,53]. However, there is little definition of how each component may contribute to biological endpoints. The best correlations were for NF-κB activation with LPS and WSOC in the particles for in vitro cell-based responses (Fig. 6H). Specific components of nPM contributing to different cellular responses will be sought in future studies. Because ambient particles vary widely in composition, we may consider developing synthetic ultrafine PM with defined chemical components. Because the surface components of particles cause initial cell responses in vitro and in vivo, surface composition rather than bulk analysis needs to be evaluated for its biological activity. For example, NF-κB induction in THP1 monocytes was dependent on iron on the surface of natural silica particles, a small fraction of the total iron [54].

Cell-based inflammatory responses to predict in vivo lung responses to ultrafine PM have been examined by several groups [19–23]. These studies with different cell models were focused on acute responses of lung toxicity. The nPM batches with a higher potency of NF-κB activation caused stronger neurotoxic responses (Fig. 5), suggesting that the cell-based NF-κB activation assay is a better predictor than in vivo responses to chronic nPM exposure. Because THP1 monocytes are human derived, we suggest that the NF-κB assay could be useful for estimating neurotoxicity of human urban PM exposure.

The potency of urban PM for membrane lipid peroxidation or NO production was poorly correlated with in vivo neurotoxic responses (Fig. 5), suggesting that neither DPPP oxidation nor NO production is predictive for the in vivo neurotoxicity. Although we don’t know how the inhalation of nanoparticle causes neurotoxicity, some evidence suggests indirect mechanisms via neurotoxicity carried by blood or lymph, lung-to-brain [36]. Unlike cytokines, oxidants and NO produced by airway cells are usually short-lived and detoxified quickly at production loci, and thus are unlikely to reach the brain at sufficient concentrations for direct responses [15]. DPPP oxidation in THP1 cells results from direct interaction of the particles with these H2O2-producing cells. These products are very low in quantity and unlikely to travel far from the membrane site of production. Although the lipid peroxidation measured by HNE-protein adducts was increased in some regions of mouse brain upon acute exposure to urban particles [38,55], we did not see 4-HNE elevations in mouse brain after chronically exposed to nPM (data not shown).

In sum, these three cell-based assays for biological responses to air pollution particles had limited correlation with in vivo responses with each other and with in vivo neurotoxic responses. The in vitro NF-κB activation was the most robust correlation with in vivo neurotoxic responses to urban ambient PM. A caveat is the small number of nPM batches available for comparison for in vivo neurotoxic effects, which cannot rule out false correlation between the cell-based assays and in vivo responses. Another limitation is the time-dependent changes of in vivo endpoint makers, which were limited to 8 weeks for Aβ40/42 peptides and Iba1. The NF-κB cell-based assay hold promise for predicting neurotoxicity in vivo.

3.1. Methods and materials

Most reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Diphenyl-1-pyrenylphosphine (DPPP), Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); RPMI 1640 and DMEM cell culture media (Thermal Fisher, Rockford, IL, USA); QUANTI-Blue, InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA); diesel exhaust particles (DEP), Environment Protection Agency (EPA, USA), and Dr. Staci Bilbo, Harvard University. Antibodies for NF-kBp65, Lamin A/C were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

In conducting research using animals, the investigator(s) adhered to the laws of the United States and regulations of the Department of Agriculture. In the conduct of research utilizing recombinant DNA, the investigator adhered to NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules. In the conduct of research involving hazardous organisms or toxins, the investigator adhered to the CDC-NIH Guide for Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories.

3.2. Collection of nPM and sPM

Ambient nanoscale particulate matter (nPM; particles with aerodynamic diameters less than 0.25 μm) were collected on Zeflour PTFE filters (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI) by a High-Volume Ultrafine Particle (HVUP) Sampler [56] at 400 L/min flow rate within 150 m downwind of the urban freeway (I-110). These aerosols represent a mix of fresh and aged ambient PM, mostly from vehicular traffic. The filter-deposited dried nPM were eluted by sonication into deionized water, referred to as nPM [7,57].

The slurry PM (sPM) was collected using the aerosol-into-liquid collector, which utilizes the saturation-condensation, particle-to-droplet growth system developed for the versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES) [58,59]. This sampler operates with a major flow rate of 300 l/min and collects ambient PM2.5 directly as concentrated a slurry [60]. The PM samples used in this study are listed in Table 1.

3.3. Chemical profiles of nPM and sPM

Total elemental composition of the nPM samples was quantified by digestion of a section of the filter-collected nPM using a microwave aided, sealed bomb, mixed acid digestion (nitric acid, hydrofluoric acid, hydrochloric acid). Digests were analyzed by mass spectrometry (SF-ICPMS) [61]. WSOC analyses used Sievers 900 Total Organic Carbon Analyzer [62].

Endotoxin [32] was assayed by Limulus based Pierce LAL chromogenic endotoxin kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). LPS neutralization was done by pre-incubating PM samples with 10 ng/ml polymyxin B for 20 min at RT with vertexing.

3.4. Cell culture

THP1-Blue NF-κB monocytes from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA) were maintained in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep, 100 μg/ml Normocin, and 10 μg/ml Blasticidin at 4×105−1×106 cells/ml with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

BV-2 cells (mouse microglia line) were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep and 1% glutamine with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

3.5. NF-κB activity

THP1-Blue monocytes were seeded in 96-well plates at 8 × 105 cells/ml for PM treatment. After PM exposure, cells were centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 min and supernatants were assayed for SEAP activity with QUANTI-Blue (InvivoGen). In brief, supernatant was added to QUANTI-Blue solution in 96-well assay plates, incubated at 37 °C/1 h, followed by spectrophotometry at 652 nm.

3.6. Lipid peroxidation assay with DPPP assay

THP1-Blue monocytes/8 × 105 cells/ml were incubated with 4.5 μM DPPP for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice, re-suspended in media, and seeded in 96-well plates. Fluorescence was followed kinetically for 20 min (excitation, 351 nm; emission, 380 nm). Lipid peroxidation was assessed 20 min posttreatment.

3.7. Nitrogen oxide (NO)

NO and NO2−/NO3− in cell media were measured by Griess reagent [63], with NaNO2 as standards.

3.8. Isolation of nuclear protein and Western blotting

Nuclear protein was extracted by using NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents by following protocol from the manufacturer (Thermal Fisher, Rockford, IL, USA).

3.9. Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol and cDNA was synthesized using reverse transcription kit from Thermal Fisher Scientific. Then mRNA was determined using quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay in ABI7500 Real Time PCR machine (Thermal Fisher Scientific). The primers and analysis method were as reported before [64].

3.10. Animals

Animal procedures were approved by the University of Southern California (USC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Young adult C57BL/6NJ male mice (6–8 wks, 27 g mean weight; n = 10/group) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. After acclimation, mice were exposed to re-aerosolized nPM at 300 μg/m3 (nPM group) or filtered air (controls) for 5 h/d, 3 d/wk, for 3 or 8 weeks [7,57]. Mice were euthanized under anesthesia; brains were stored at −80 °C.

3.11. Inhalation exposure

To provide a stable source of concentrated PM for in vivo exposure studies, sonicated PM suspensions were re-aerosolized using commercially available HOPE nebulizers (B&B Medical Technologies, USA). As shown in Fig. S2A, a pump (Model VP0625-V1014-P2–0511, Medo Inc., USA) generated HEPA-filtered compressed air that was introduced into the nebulizer’s suspension to re-aerosolize the PM liquid suspension. Using a vacuum pump (Model VP0625-V1014-P2–0511, Medo Inc., USA) at 5lpm dilution flow rates, the re-aerosolized PM was drawn through a diffusion dryer (Model 3620, TSI Inc., USA) with silica gel to remove excess water, and through Po-210 neutralizes (Model 2U500, NRD Inc., USA) to remove electrical charges. This re-aerosolized PM was passed through sealed exposure chambers housing mice. The particles were collected in parallel on 37 mm PTFE (Teflon) and Quartz (Pall Life Sciences, 2-μm pore, Ann Arbor, MI) filters for chemical analysis [57].

A scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS 3936, TSI Inc., USA) connected to a condensation particle counter (CPC 3022A, TSI Inc., USA) evaluated the physical properties (i.e., number and mass size distribution) of the re-aerosolized PM, at 100 inch H2O pressure and 5 lpm dilution flow. A representative distribution of nPM particle number concentration is shown in Fig. S2.

3.12. Inflammatory cytokines

Cerebral cortex lysates were assayed for select cytokines by V-PLEX proinflammatory panel 2 immunoassay (Mesoscale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA).

3.13. Iba1 and Aβ peptides

Brain sections were stained for Iba1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), a marker of microglia activation. Hippocampal Iba1 fluorescence was calculated by imageJ software.

Aβ40/42 peptides were measured in supernatants of cortex using Peptide Panel 1 (4G8) Kit V-plex (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD, USA) [65].

3.14. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism v.7. Depending on the number of classes in the categorical variable, mean differences were analyzed by t-test or ANOVA, with Tukey post hoc with Bonferroni multiple test correction. Values were expressed as mean ± SE for p < 0.05 as significant. Hierarchical clustering analysis used Rstudio. Interquartile ranges were calculated from scaled data with mean of 0 and SD of 1, which compares the variability in each outcome regardless of baseline average.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by NIH grants T32-AG052374 (A.H.), R01-ES023864 (HJF), R01-AG051521 (CEF), P01-AG055367 (CEF). This work was also supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Parkinson’s Research Program under Award No. W81XWH-17-1-0535 (CEF). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.09.016.

References

- [1].Gatto NM, Henderson VW, Hodis HN, St John JA, Lurmann F, Chen JC, Mack WJ, Components of air pollution and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults in Los Angeles, Neurotoxicology (Little Rock) 40 (2014) 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen H, Kwong JC, Copes R, Tu K, Villeneuve PJ, van Donkelaar A, Hystad P, Martin RV, Murray BJ, Jessiman B, Wilton AS, Kopp A, Burnett RT, Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study, Lancet 389 (2017) 718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cacciottolo M, Wang X, Driscoll I, Woodward N, A Saffari, Reyes J, Serre ML, Vizuete W, Sioutas C, Morgan TE, Gatz M, Chui HC, Shumaker SA, Resnick SM, Espeland MA, Finch CE, Chen JC, Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models, Transl. Psychiatry 7 (2017) e1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Calderon-Garciduenas L, R Reynoso-Robles A Gonzalez-Maciel, Combustion and friction-derived nanoparticles and industrial-sourced nanoparticles: the culprit of Alzheimer and Parkinson’s diseases, Environ. Res 176 (2019) 108574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, Booth A, Mudway I, Anstey KJ, Air pollution and dementia: a systematic review, J. Alzheimer’s Dis 70 (2019) S145–S163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fonken LK, Xu X, Weil ZM, Chen G, Sun Q, Rajagopalan S, Nelson RJ, Air pollution impairs cognition, provokes depressive-like behaviors and alters hippocampal cytokine expression and morphology, Mol. Psychiatry 16 (2011) 987–995 973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Morgan TE, Davis DA, Iwata N, Tanner JA, Snyder D, Ning Z, Kam W, Hsu YT, Winkler JW, Chen JC, Petasis NA, Baudry M, Sioutas C, Finch CE, Glutamatergic neurons in rodent models respond to nanoscale particulate urban air pollutants in vivo and in vitro, Environ. Health Perspect 119 (2011) 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bhatt DP, Puig KL, Gorr MW, Wold LE, Combs CK, A pilot study to assess effects of long-term inhalation of airborne particulate matter on early Alzheimer-like changes in the mouse brain, PLoS One 10 (2015) e0127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Landrigan PJ, Air pollution and health, Lancet Public Health 2 (2017) e4–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Daher N, Hasheminassaba S, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C, Seasonal and spatial variability in chemical composition and mass closure of ambient ultrafine particlcs in the mcgacity of Los Angeles, Environ Sci Process Impacts 15 (2013) 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Heo J, de Foy B, Olson MR, Pakbin P, Sioutas C, Schauer JJ, Impact of regional transport on the anthropogenic and biogenic secondary organic aerosols in the Los Angeles Basin, Atmos. Environ 103 (2015) 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heo JB, Dulger M, Olson MR, McGinnis JE, R Shelton B, Matsunaga A, Sioutas C, Schauer JJ, Source apportionments of PM2.5 organic carbon using molecular marker Positive Matrix Factorization and comparison of results from different receptor models, Atmos. Environ 73 (2013) 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Canagaratna MR, Jayne JT, Ghertner DA, Herndon S, Shi Q, Jimenez JL, Silva PJ, Williams P, Lanni T, Drewnick F, Demerjian KL, Kolb CE, Worsnop R, Chase studies of particulate emissions from in-use New York City vehicles, Aerosol Sci. Technol 38 (2004) 555–573. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Charron A, Harrison RM, Primary particle formation from vehicle emissions during exhaust dilution in the roadside atmosphere, Atmos. Environ 37 (2003) 4109–4119. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kunzli N, Mudway LS, Gotschi T, Shi T, Kelly FJ, Cook S, Burney P, Forsberg B, Gauderman JW, Hazenkamp ME, Heinrich J, Jarvis D, Norback D, Payo-Losa F, Poli A, Sunyer J, Borm PJ, Comparison of oxidative properties, light absorbance, total and elemental mass concentration of ambient PM2.5 collected at 20 European sites, Environ. Health Perspect 114 (2006) 684–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rushton EK, Jiang J, Leonard SS, Eberiy S, Castranova V, Biswas P, Elder A, Han X, Gdein R, Finkelstcin J, Oberdorster G, Concept of assessing nanoparticle hazards considering nanoparticle dosemetric and chemical/biological response metrics, J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 73 (2010) 445–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Forman HJ, Finch CE, A critical review of assays for hazardous components of air pollution, Free Radic. Biol. Med 117 (2018) 202–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Seagrave J, McDonald JD, Gigliotti AP, Nikula KJ, K Seilkop S, Gurevich M, Mauderiy JL, Mutagenicity and in vivo toxicity of combined particulate and semivolatile organic fractions of gasoline and diesel engine emissions, Toxicol. ScL 70 (2002) 212–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sayes CM, Reed KL, Warheit DB, Assessing toxicity of fine and nanoparticles: comparing in vitro measurements to in vivo pulmonary toxicity profiles, Toxicol. Sci 97 (2007) 163–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim YH, Boykin E, Stevens T, Lavrich K, Gilmour MI, Comparative lung toxicity of engineered nanomaterials utilizing in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo approaches, J. Nanobiotechnol 12 (2014) 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Teeguarden JG, Mikheev VB, R Minard K, Forsythe WC, Wang W, Sharma G, Karin N, Tilton SC, Waters KM, Asgharian B, R Price O, Pounds JG, Thrall BD, Comparative iron oxide nanoparticle cellular dosimetry and response in mice by the inhalation and liquid cell culture exposure routes, Part. Fibre Toxicol 11 (2014) 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Donaldson K, Schinwald A, Murphy F, Cho WS, R Duffin L Tran, C. Poland, The biologically effective dose in inhalation nanotoxicology, Acc. Chem. Res 46 (2013) 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Loret T, Rogerieux F, Trouiller B, Braun A, Egles C, Lacroix G, Predicting the in vivo pulmonary toxicity induced by acute exposure to poorly soluble nanomaterials by using advanced in vitro methods, Part. Fibre Toxicol 15 (2018) 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Block ML, Calderon-Garciduenas L, Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease, Trends Neurosci. 32 (2009) 506–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lawrence T, The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1 (2009) a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bolton JL, Marinero S, Hassanzadeh T, Natesan D, Le D, BeUiveau C, Mason SN, Auten RL, Bilbo SD, Gestational exposure to air pollution alters cortical volume, microglial morphology, and microglia-neuron interactions in a sex-specific manner, Front. Synaptic Neurosci 9 (2017) 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Duff GW, Atkins E, The inhibitory effect of polymyxin B on endotoxin-induced endogenous pyrogen production, J. Immunol. Methods 52 (1982) 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Weinberg JB, Misukonis MA, Shami PJ, Mason SN, Sauls DL, Dittman WA,Wood ER, K Smith G, McDonald B, Bachus KE, et al. , Human mononuclear phagocyte inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS): analysis of iNOS mRNA iNOS protein, biopterin, and nitric oxide production by blood monocytes and peritoneal macrophages, Blood 86 (1995) 1184–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Di Pietro A, Visalli G, Munao F, Baluce B, Maestra S. La, Primerano P,Corigliano F, De Flora S, Oxidative damage in human epithelial alveolar cells exposed in vitro to oil fly ash transition metals, Int J. Hyg Environ. Health 212 (2009)196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Okimotoa Y, Watanabea A, Nikia E, Yamashitab T, Noguchia N, A novel fluorescent probe diphenyl-1-pyrenylphosphine to follow lipid peroxidation in cell membranes, FEBS Lett. 474 (2000) 137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang H, Forman HJ, Signaling by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: exposure protocols, target selectivity and degradation, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 617 (2017) 145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Puente BN, Kimura W, A Muralidhar S, Moon J, Amatruda JF, Phelps KL, Grinsfelder D, Rothermel BA, Chen R, Garcia JA, Santos CX, Thet S, Mori E, Kinter MT, Rindler PM, Zacchigna S, Mukheijee S, Chen DJ, Mahmoud AI, Giacca M, Rabinovitch PS, Aroumougame A, Shah AM, Szweda LI, Sadek HA, The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response, Cell 157 (2014) 565–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lovett C, Cacciottolo M, Shirmohammadi F, Haghani A, Morgan TE, Sioutas C, Finch CE, Diurnal Variation in the Proinflammatory Activity of Urban Fine Particulate Matter (PM 2.5) by in Vitro Assays, (2018) FlOOORes 7:596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nakayama M, Macrophage recognition of crystals and nanoparticles, Front. Immunol 9 (2018) 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ovrevik J, Refsnes M, Lag M, Brinchmann BC, Schwarze PE, A Holme J, Triggering mechanisms and inflammatory effects of combustion exhaust particles with implication for carcinogenesis, Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol 121 (Suppl 3) (2017) 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chao CC, Hu S, Molitor TW, Shaskan EG, Peterson PK, Activated microglia mediate neuronal cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism, J. Immunol 149 (1992) 2736–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Woodward NC, Haghani A, Johnson RG, Hsu TM, Saffari A, Sioutas C, Kanoski SE, Finch CE, Morgan TE, Prenatal and early life exposure to air pollution induced hippocampal vascular leakage and impaired neurogenesis in association with behavioral deficits, Transl. Psychiatry 8 (2018) 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cole TB, Cobum J, Dao K, Roque P, Chang YC, Kalia V, Guilarte TR, Dziedzic J, Costa LG, Sex and genetic differences in the effects of acute diesel exhaust exposure on inflammation and oxidative stress in mouse brain, Toxicology 374 (2016) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nway NC, Fujitani Y, Hirano S, Mar O, Win-Shwe TT, Role of TLR4 in olfactory-based spatial learning activity of neonatal mice after developmental exposure to diesel exhaust origin secondary organic aerosol, Neurotoxicology (Little Rock) 63 (2017) 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Durga M, Devasena T, Rajasekar A, Determination of LC50 and sub-chronic neurotoxicity of diesel exhaust nanoparticles, Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol 40 (2015) 615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Di Natale C, Scognamiglio PL, Cascella R, Cecchi C, A Russo M Leone, A. Penco, A Relini, L. Federid, A. Di Matteo, F. Chiti, L. Vitagliano, D. Marasco, Nucleophosmin contains amyloidogenic regions that are able to form toxic aggregates under physiological conditions, FASEB J. 29 (2015) 3689–3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mumaw CL, Levesque S, McGraw C, Robertson S, Lucas S, Stafflinger JE, Campen MJ, Hall P, Norenberg JP, Anderson T, Lund AK, McDonald JD, Ottens AK, Block ML, Microglial priming through the lung-brain axis: the role of air pollution-induced circulating factors, FASEB J. 30 (2016) 1880–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gavett SH, Madison SL, Dreher KL, Winsett DW, McGee JK, Costa DL, Metal and sulfate composition of residual oil fly ash determines airway hyperreactivity and lung injury in rats, Environ. Res 72 (1997) 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kodavanti UP, Hauser R, Christiani DC, Meng ZH, McGee J, Ledbetter A, Richards J, Costa DL, Pulmonary responses to oil fly ash particles in the rat differ by virtue of their specific soluble metals, Toxicol. Sci 43 (1998) 204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Prahalad AK, Soukup JM, Inmon J, Willis R, Ghio AJ, Becker S, Gallagher JE, Ambient air particles: effects on cellular oxidant radical generation in relation to particulate elemental chemistry, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 158 (1999) 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hetland RB, Refsnes M, Myran T, Johansen BV, Uthus N, Schwarze PE, Mineral and/or metal content as critical determinants of particle-induced release of IL-6 and IL-8 from A549 cells, J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 60 (2000) 47–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jiang N, Dreher KL, Dye JA, Li Y, Richards JH, Martin LD, Adler KB, Residual oil fly ash induces cytotoxicity and mucin secretion by Guinea pig tracheal epithelial cells via an oxidant-mediated mechanism, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 163 (2000) 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Xia T, Kovochich M, Brant J, Hotze M, Sempf J, Oberley T, Sioutas C, Yeh JI, Wiesner MR, Nel AE, Comparison of the abilities of ambient and manufactured nanoparticles to induce cellular toxidty according to an oxidative stress paradigm, Nano Lett. 6 (2006) 1794–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Vidrio E, Phuah CH, Dillner AM, Anastasio C, Generation of hydroxyl radicals from ambient fine partides in a surrogate lung fluid solution, Environ. Sd. Technol 43 (2009) 922–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].A Saffari N Daher, M.M. Shafer, J.J. Schauer, C. Sioutas, Global perspective on the oxidative potential of airborne particulate matter: a synthesis of research findings, Environ. Sci. Technol 48 (2014) 7576–7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Guastadisegni C, Kelly FJ, Cassee FR, Geriofs-Nijland ME, Janssen NA, Pozzi R, Brunekreef B, Sandstrom T, Mudway I, Determinants of the pro-inflammatory action of ambient particulate matter in immortalized murine macrophages, Environ. Health Perspect 118 (2010) 1728–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sun X, Wei H, Young DE, Bein KJ, Smiley-Jewell SM, Zhang Q, Fulgar CCB, AR Castaneda Pham AK, Li W, Pinkerton KE, Differentia] pulmonary effects of wintertime California and China particulate matter in healthy young mice, Toxicol. Lett 278 (2017) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Murugan K, Choonara YE, Kumar P, Bijukumar D, du Toit LC, Pillay V, Parameters and characteristics governing cellular internalization and trans-barrier trafficking of nanostructures, Int. J. Nanomed 10 (2015) 2191–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Premasekharan G, Nguyen K, Contreras J, Ramon V, Leppert VJ, Forman HJ, Iron-mediated lipid peroxidation and lipid raft disruption in low-dose silica-induced macrophage cytokine production, Free Radic. Biol. Med 51 (2011) 1184–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cheng H, Saffari A, Sioutas C, Forman HJ, Morgan TE, Finch CE, Nanoscale particulate matter from urban traffic rapidly induces oxidative stress and inflammation in olfactory epithelium with concomitant effects on brain, Environ. Health Perspect 124 (2016) 1537–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Misra C, Kim S, Shen S, Sioutas C, A high flow rate, very low pressure drop impactor for inertial separation of ultrafine from accumulation mode partides, J. Aerosol ScL 33 (2002) 735–752. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Taghvaee S, Mousavi A, Sowlat MH, Sioutas C, Development of a novel aerosol generation system for conducting inhalation exposures to ambient particulate matter (PM), Sd. Total Environ 665 (2019) 1035–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kim S, Jaques PA, Chang MC, Barone T, Xiong C, Friedlander SK, Sioutas C, Versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES) for simultaneous in vivo and in vitro evaluation of toxic effects of ultrafine, fine and coarse ambient particles - Part II: field evaluation, J. Aerosol Sci 32 (2001) 1299–1314. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kim S, Jaques PA, Chang MC, Froines JR, Sioutas C, Versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES) for simultaneous in vivo and in vitro evaluation of toxic effects of ultrafine, fine and coarse ambient particles - Part I: development and laboratory characterization, J. Aerosol Sci 32 (2001) 1281–1297. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang DB, Pakbin P, Saffari A, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C, Development and evaluation of a high-volumc Acrosol-into-Liquid collcctor for fine and ultrafine particulate matter, Aerosol Sci. Technol 47 (2013) 1226–1238. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hemer JD, Green PG, Kleeman MJ, Measuring the trace elemental composition of size-resolved airborne particles, Environ. Sci. Technol 40 (2006) 1925–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Stone EA, Hedman CJ, Sheesley RJ, Shafer MM, Schauer JJ, Investigating the chemical nature of humic-like substances (HULIS) in North American atmospheric aerosols by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ 43 (2009) 4205–4213. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ignarro LJ, Fukuto JM, Griscavage JM, Rogers NE, Byms RE, Oxidation of nitric oxide in aqueous solution to nitrite but not nitrate: comparison with enzymatically formed nitric oxide from L-arginine, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 90 (1993) 8103–8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhang H, Liu H, Zhou L, Yuen J, Forman HJ, Temporal changes in glutathione biosynthesis during the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response of THP1 macrophages, Free Radic. Biol. Med 113 (2017) 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Cacciottolo M, Christensen A, Moser A, Liu J, Pike CJ, Smith C, LaDu MJ, Sullivan PM, Morgan TE, Dolzhenko E, Charidimou A, Wahlund LO, Wiberg MK, Shams S, Chiang GC, Finch CE, The APOE4 allele shows opposite sex bias in microbleeds and Alzheimer’s disease of humans and mice, Neurobiol. Aging 37 (2016) 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.