Abstract

Introduction

Second generation electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS; also known as e-cigarettes, vaporizers or vape pens) are designed for a customized nicotine delivery experience and have less resemblance to regular cigarettes than first generation “cigalikes.” The present study examined whether they generalize as a conditioned cue and evoke smoking urges or behavior in persons exposed to their use.

Methods

Data were analyzed inN = 108 young adult smokers (≥5 cigarettes per week) randomized to either a traditional combustible cigarette smoking cue or a second generation ENDS vaping cue in a controlled laboratory setting. Cigarette and e-cigarette urge and desire were assessed pre- and post-cue exposure. Smoking behavior was also explored in a subsample undergoing a smoking latency phase after cue exposure (N = 26).

Results

The ENDS vape pen cue evoked both urge and desire for a regular cigarette to a similar extent as that produced by the combustible cigarette cue. Both cues produced similar time to initiate smoking during the smoking latency phase. The ENDS vape pen cue elicited smoking urge and desire regardless of ENDS use history, that is, across ENDS naїve, lifetime or current users. Inclusion of past ENDS or cigarette use as covariates did not significantly alter the results.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate that observation of vape pen ENDS use generalizes as a conditioned cue to produce smoking urge, desire, and behavior in young adult smokers. As the popularity of these devices may eventually overtake those of first generation ENDS cigalikes, exposure effects will be of increasing importance.

Implications

This study shows that passive exposure to a second generation ENDS vape pen cue evoked smoking urge, desire, and behavior across a range of daily and non-daily young adult smokers. Smoking urge and desire increases after vape pen exposure were similar to those produced by exposure to a first generation ENDS cigalike and a combustible cigarette, a known potent cue. Given the increasing popularity of ENDS tank system products, passive exposures to these devices will no doubt increase, and may contribute to tobacco use in young adult smokers.

Introduction

Controversy and confusion continue to surround electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), also known as electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes.1,2 Of particular concern is whether these devices represent a safe harm reduction method to regular cigarette smoking or if they evoke additional health harms and/or perpetuate nicotine dependence. Use of these products has increased substantially in recent years,3,4 with nearly 70% of current smokers reporting having ever used e-cigarettes and 50% reporting regular use.5 Across the age span, the highest prevalence of ENDS use is observed in young adults,3,5 who perceive ENDS as accessible, convenient, and modern.6 Accordingly, ENDS marketing on social media is common7 and young adults are specifically targeted in certain e-cigarette advertising campaigns8–11 and specialty vape shops and lounges.12

First generation “cigalike” electronic cigarettes were designed to closely resemble traditional cigarettes and have predominated the United States and European markets since the advent of e-cigarettes in 2007.10,13 In contrast, newer, second generation, mid-size ENDS devices, referred to as vape pens or personal vaporizers, were designed to accommodate larger atomizers and batteries to deliver a more customized nicotine experience, and as such, resemble a large pen more than a cigarette.14 These advanced devices are increasing in popularity15 and are forecasted to overtake the sales of first generation ENDS products in the next decade.16 Population trends show that many ENDS users who initially utilize cigalike products will transition to second or higher generation devices in order to achieve a more powerful delivery of nicotine concentrations and to use a greater range of e-liquid options.17,18

While some experts contend that ENDS use could decrease combustible cigarette smoking in young adults,19,20 others have raised concerns that their increasing use could perpetuate and/or re-normalize smoking behaviors.1,21–24 As stimuli associated with regular cigarettes elicit smoking urges,25–27 it is possible that given the similarity of e-cigarettes to regular cigarettes, they may also generalize as a (Pavlovian) conditioned cue and elicit smoking urges. Indeed, prior controlled laboratory work by our group has demonstrated that passive exposure to ENDS cigalikes, either in person28 or by video advertisements29 significantly increased young adult smokers’ desire for both an e-cigarette and a combustible cigarette. Other groups have also found that exposure to ENDS advertisements in the natural environment was associated with favorable electronic cigarette product beliefs and urges to smoke.30,31 As these aforementioned studies have concentrated on cigalike devices, the question remains whether exposure to second generation ENDS vape pens, which have less physical resemblance to regular cigarettes, would also generalize as a smoking cue and affect smoking urge and behavior.

Thus, in the present study, we examined whether direct observation of ENDS vape pen use produces changes in smoking urge, desire, and behavior in young adult smokers. The rationale for examining this age range was that they comprise the subgroup with the highest prevalence of ENDS use,5 smoking levels are relatively stable across these ages,32 and for consistency across studies.28,29,33 Our goal was to extend our prior work28,29 by: (1)Examining effects of a second generation vape pen cue versus a traditional smoking cue and a nonsmoking control cue, (2)Including a wider range of young adult smokers from light non-daily to regular daily users, (3)Exploring cue effects on smoking behavior to augment subjective findings that rely on one’s awareness of internal states,34–36 and (4)Comparing findings from the current study on vape pen cue exposure to those obtained in our prior study with a cigalike cue.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited via online advertisements seeking research volunteers for a study “assessing mood response following exposure to common tasks and social interactions.” This general description was chosen in order to reduce regular cigarette or ENDS expectancy on study measures. After the study concluded, participants were compensated for their time and fully debriefed. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 35 years, in good general health, current cigarette smoker (≥5 cigarettes per week), and not currently attempting to quit smoking. After meeting general eligibility criteria from a telephone interview, candidates were invited into the laboratory for an in-person screening session. Prior to their arrival for the screening session, candidates were instructed to abstain from recreational drugs and alcohol for 24 hours and cigarette smoking for 1 hour. Upon arrival, following informed consent, abstinence adherence was confirmed via self-report. Breath alcohol readings were required to be ≤0.003 mg% (Alco-Sensor III, Intoximeter, St. Louis, MO), and expired air carbon monoxide (CO) breath tests ≤15 ppm (Smokerlyzer, Bedfont Scientific, Medford, NJ). The mean reported time since last cigarette was 9.1 ± 1.6 SEM hours and the mean CO reading was 8.7 ± 0.8 ppm. The 1-hour in-person screening consisted of surveys and interviews assessing demographics, background characteristics, and substance use behaviors. Measures included the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),37 the Timeline Follow-Back Calendar38 for past month smoking, mood scales (ie, Beck Depression Inventory39; Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory40), and a modified non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview forDSM-IV.41 Candidates were excluded if they did not meet the basic inclusion criteria or had survey scores that were outside standard cut-off thresholds for severe depression or anxiety or had a major untreated psychiatric disorder. Eligible candidates from the in-person screening (N = 111/116; 96%) then immediately participated in the 1-hour experimental session.

Study Design

The study employed a randomized between-subjects design. Randomization was computer generated and stratified by sex and race. Each participant was informed that the experimental session would include participating in two 5-minute task completion periods with another participant and separated by a 15-minute rest period. Participants were informed that all tasks were approved for use in the laboratory rooms. To increase ecological validity and compare to our prior cigalike exposure study,28 the study cues were included during a social interaction period with a study confederate portraying the role of another study participant.25,42

At the beginning of the session (Time 0), the participant completed computerized baseline surveys for 5 minutes and then rested for 5 minutes before the onset of the first 5-minute task period. The participant and confederate were introduced and each opened an envelope with his/her selected task. The randomly selected tasks were described as engaging in conversation, viewing pictures, eating food, drinking a beverage, or smoking. The participant’s task was predetermined as engaging in conversation with the confederate from a provided discussion topic list, including: movies and television, local landmarks, vacations, weather, pets, or places to eat. The confederate’s task was predetermined as drinking bottled water (ie, the nonsmoking control cue). Both were instructed to focus on their selected task and to do their best to engage in the conversation as it would be videotaped and scored later for social interaction.

After the first task, the participant and confederate each completed study measures in separate rooms (+15 minutes; water cue) followed by a 10-minute rest period. They were then reconvened for the second task period and again each opened an envelope with his/her selected task. As was predetermined, the participant engaged in conversation with the confederate who used either a combustible cigarette or an ENDS vape pen. After this second 5-minute task, measures were again completed in separate rooms (+35 minutes; active cue[s]) followed by a 10-minute rest period. A final set of survey ratings were then completed at the end of the session (+50 minutes, post cue).

After receiving regulatory approval in the later stages of the study, the protocol was extended (Time +55 to +105 minutes) to examine participants’ ability to resist smoking a regular cigarette. This portion entailed a modified smoking latency phase from the reliable and valid Smoking Lapse Task established for cue reactivity research in smokers.43,44 A regular cigarette provided by the study was visible on a tray along with an ashtray and lighter. No other stimuli (ie, television, magazines, and clocks, etc.) were present during this period. The participant could choose to smoke the cigarette at any time during the 50-minute period or receive $0.20 for each 5-minute interval in which they did not smoke. As with previous work examining younger and low-income smokers,45–47 the total possible amount earned was $2.00 if smoking was not chosen during the entire period. The dependent variable was the length of time in minutes that the participant chose not to smoke. Only daily smokers (n = 26) were examined as they have been found to be more sensitive to this task than non-daily smokers.48,49

Cues

During the study task periods, one of the two study confederates (Caucasian male, age 19 years; Middle Eastern female, age 23 years) engaged in the nonsmoking control cue, that is, drinking a standard 12 oz. water bottle (Nestle Pure Life), as well as the two active cues, that is, smoking a combustible cigarette (Camel or Marlboro) or vaping an ENDS vape pen (eGo device, 10 mg nicotine JJuice e-liquid, tobacco flavor). The vape pen was black in color with silver band edging, a dark gray clearomizer, 13 centimeters in length, and 1.5 centimeters in diameter. The device had a blue LED switch on top with a five click on/off switch and contained a 3.7 volt 650 mAh rechargeable battery. For participants who preferred mentholated cigarettes, the confederate either smoked a menthol cigarette (Newport) or used a menthol flavored e-liquid (JJuice 10 mg nicotine menthol e-liquid).

Measures

The main dependent measures were the total score from the 10-item Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (BQSU) and two visual analogue scale (VAS) items, “desire for a regular cigarette (your preferred brand)” and “desire for an electronic cigarette.” The BQSU items were rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with the total score ranging from 10 to 70.50 The VAS items were each anchored from “not at all” (0) to “most ever” (100).51 To mask the focus of the study, additional VAS items were embedded in the surveys, such as desire for conversation, water, salty foods, etc., and a wash-out task, the 90-second digit symbol substitution task,52 was included after each set of surveys.

A random selection of approximately one-third the videotaped exchanges between the participant and the confederate were later reviewed by two independent raters to ascertain the number of hand-to-mouth movements and to rate the quality of the social interaction using the active engagement subscale from the Two-Dimensional Social Interaction Scale.53 These ratings revealed an average of 12.2 hand-to-mouth movements that were similar between active cues (regular cigarette, mean = 11.4 ± 0.4 SEM; e-cigarette, mean 12.4 ± 0.5 SEM [t = 1.56,p = .12]). The social interactions were rated as largely positive and favorable, with no differences between cue types (p = ns). On a study exit interview, 20% of participants correctly identified the study purpose to assess desire to smoke, with 69% and 11% identifying general mood (eg, “to examine moods when you interact with others,”) or other non-specific responses (eg, “to see how I reacted in different situations”), respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Data were summarized as change scores for each dependent variable by subtracting scores at each rating period (water cue, active cue [s], and post cue) from their respective baseline measure. For urge and desire ratings, data were analyzed by Generalized Estimated Equations (GEE) with cue group (regular cigarette and vape pen) as the between-subjects factor and time as the within-subjects factor. All analyses were conducted with the baseline rating as a covariate as high baseline ratings can produce a ceiling effect on responses. Analyses were then repeated with smoking level as a covariate, expressed as the number of cigarettes smoked per week (log transformed due to the large range and left-skewness of the distribution), as well as ENDS past history (naïve users who never used an e-cigarette, lifetime users who used e-cigarettes in past but not in the past month, and current users who used e-cigarettes in the past month) to ascertain if these variables affected the results. For smoking behavior assessment, a survival analysis was conducted by the Cox Hazard model. These analyses also included smoking level (past month total cigarettes smoked) and ENDS past history (naïve, lifetime, and current users) as covariates. Finally, GEE analyses compared smoking urge and desire responses to the ENDS vape pen cue in the current study to the responses to an ENDS cigalike cue from our prior 2015 study.28 Only regular daily smokers (n = 42) in current sample were included in this analysis to facilitate comparison with daily smokers from the prior study (n = 30).28

Results

Data were collected between May and September 2015. Of the 111 enrolled participants, data were excluded on three outliers, (ie, those with data less than or greater than 3SD on smoking desire or urge ratings), thus yieldingN = 108 as the final sample for analyses. The sample had an average of 6.6 smoking days per week (range: 1.3–7.0) and 8.7 cigarettes smoked on smoking days (range 1.1–22.0). No differences were found in demographic characteristics, smoking behaviors, or ENDs use in the two cue exposure groups (seeTable 1). Of note, while prior ENDS use was not an eligibility criterion, it was relatively common with 83% (90/108) of the sample reporting having ever used an e-cigarette and 27% (29/108) reporting current use in the past month (mean 1.6 ± 0.4 SEM days).

Table 1.

Group Characteristics

| Cigarette cue Group (n = 50) | Vape pen cue group (n = 58) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and background | |||

| Age (y) | 26.9 (0.6) | 26.8 (0.7) | p = .99 |

| Education (y) | 14.1 (0.3) | 14.2 (0.3) | p = .75 |

| Sex (% male) | |||

| Race | p = .97 | ||

| %Caucasian | 20 (40%) | 22 (38%) | — |

| %African American | 22 (44%) | 27 (47%) | — |

| %Other | 8 (16%) | 9 (16%) | — |

| Beck depression inventory | 8.9 (1.0) | 7.3 (1.0) | p = .22 |

| Spielberger anxiety (t-score) | 60.4 (0.7) | 61.2 (0.7) | p = .46 |

| Alcohol drinks/wk | 9.0 (1.6) | 8.4 (1.6) | p = .80 |

| Smoking patterns and use | |||

| Cigarettes/smoking day | 8.2 (0.7) | 9.1 (0.7) | p = .43 |

| Smoke d/wk | 6.4 (0.2) | 6.8 (0.1) | p = .14 |

| Menthol prefererence | 30 (60%) | 35 (60%) | p = .97 |

| FTNDa | 3.9 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.3) | p = .84 |

| Naïve ENDS user (never used ENDS) | 9 (26%) | 9 (16%) | p = .56 |

| Lifetime ENDS user (no past month ENDS use) | 29 (58%) | 32 (55%) | p = .76 |

| Current ENDS user (past month ENDS use) | 12 (24%) | 17 (29%) | p = .53 |

| ENDS use d/monb | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.7) | p = .67 |

| Other tobacco use in the past year | |||

| Hookah | 28 (56%) | 27 (47%) | p = .33 |

| Cigars | 15 (30%) | 24 (41%) | p = .22 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 7 (14%) | 4 (7%) | p = .22 |

| Other (Pipe, Cloves, etc.) | 8 (16%) | 15 (26%) | p = .21 |

| Baseline ratings | |||

| BQSU total (range 10–70) | 43.0 (1.8) | 41.8 (1.7) | p = .63 |

| Cigarette desire (range 0–100) | 70.0 (2.9) | 68.2 (3.3) | p = .69 |

| E-cigarette desire (range 0–100) | 21.3 (3.6) | 18.6 (3.2) | p = .57 |

BQSU = Brief questionnaire of smoking urges; ENDS = Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Values are Mean (SEM) orN (%), as indicated. All variables were compared between groups witht test or Chi-Square as warranted. No differences were found between cue groups.

aFTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

bAmong participants who reported past month ENDS use (n = 29).

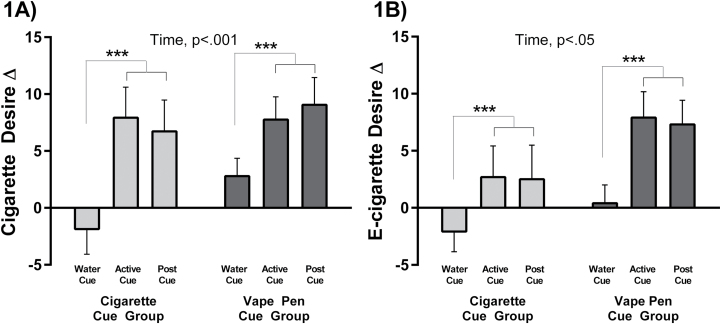

The main study GEE analyses showed that both the vape pen and regular cigarette cues significantly increased BQSU smoking urge (time: beta [SE] = 0.89 [0.23],p < .001). Both cues also increased desire for a cigarette (time: beta [SE] = 2.15 [0.49],p < .001), and an e-cigarette (time: beta [SE] = 1.15 [0.55],p = .036;Figure 1A andB). These urge and desire increases were not evident after the water cue (ps≥ .408), but emerged immediately following the cigarette and vape pen active cues and were sustained 20 minutes later (ps < .001;Table 2). These results did not differ between active cues (cue group:ps ≥ .368; cue group × time:ps ≥ .381). Results remained after including cigarette and past ENDS use as covariates in the model. An additional analysis showed that the vape pen cue increased cigarette desire and urge to a similar extent in participants with and without past ENDS use. The vape pen cue increased e-cigarette desire to a somewhat greater extent among those with past ENDS use compared to those who were ENDS-naive, but this interaction was not significant (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Data are Mean ± SEM change scores from pre-exposure baseline to water cue, and post active cue for desire for a cigarette (1A) and desire for an e-cigarette (1B). The active cues are for the regular cigarette cue exposed group (n = 50) and the electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) vape pen cue exposed group (n = 58). Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) result indicates main effect of time, with post-estimation test results indicated by the brackets ([active cue = post active cue] > Water Cue), ***ps < .001.

Table 2.

Smoking Urge and Desire Change Scores

| Primary study outcomes (N = 108) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | (Mean, SEM) | Pairwise comparisons | ||

| Water cue | Active cue | Post cue | ||

| BQSUa | ||||

| Vape pen cue | +0.9 (0.8) | +3.3 (1.0) | +3.7 (1.2) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Cigarette cue | +0.1 (1.0) | +5.1 (1.4) | +3.7 (1.4) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Desire for a cigarette | ||||

| Vape pen cue | +2.8 (1.6) | +7.8 (2.0) | +9.0 (2.4) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Cigarette cue | −1.9 (2.2) | +7.9 (2.7) | +6.7 (2.8) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Desire for an e-cigarette | ||||

| Vape pen cue | +0.1 (1.6) | +7.9 (2.3) | +7.3 (2.1) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Cigarette cue | −2.1 (1.8) | +2.7 (2.7) | +2.5 (3.0) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Primary study outcomes in subset of daily smokers exposed to vape pen cue (n = 42) vs. prior study cigalike cue (n = 30)b | ||||

| BQSU | ||||

| Vape pen cue | +0.7 (1.0) | +3.9 (1.2) | +3.8 (1.5) | (A = P) > W** |

| Cigalike cue | −1.3 (1.5) | +2.5 (1.4) | +2.9 (1.6) | (A = P) > W** |

| Desire for a cigarette | ||||

| Vape pen cue | +4.1 (1.7) | +8.9 (2.2) | +9.5 (2.5) | (A = P) > W** |

| Cigalike cue | +0.6 (2.9) | +8.7 (2.6) | +10.3 (2.6) | (A = P) > W*** |

| Desire for an e-cigarette | ||||

| Vape pen cue | −1.4 (1.9) | +7.6 (2.4) | +7.0 (2.0) | (A = P) > W** |

| Cigalike cue | +5.4 (2.9) | +18.5 (5.6) | +20.3 (5.8) | (A = P) > W** |

Data are Mean (SEM). Statistical analyses from generalized estimating equations withp values for main effects of cue type, time and their interaction.

aBQSU = Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges.

bCigalike cue group from our prior study (n = 30)28 .

**p < .01, ***p < .001 post hoc pairwise comparisons of main effects of time, for all (active cue = post active cue) > water cue.

Results for smoking latency after the cue phase indicated no difference in time to smoke between cue groups (Cox Hazard Model:z = −0.57,p = .566). The median latencies to smoke were 14.2 (interquartile range: 5.6–50) and 8.9 (interquartile range: 0.6–48.0) minutes for vape pen and regular cigarette cue groups, with mean latencies 22.1 ± 5.1 and 19.7 ± 6.5 SEM, respectively. Smoking level and past ENDS use were not significant covariates (ps ≥ .17).

In terms of the cue salience of the ENDS vape pen to the ENDS cigalike from our prior study,28 results revealed no differences between these cue types (cue group:ps > .162; cue group × time:ps > .166) as both elicited, to a similar degree, increases in smoking urge (time: beta [SE] = 1.04 [0.31],p = .001), regular cigarette desire (time: beta [SE] = 2.43 [0.59],p < .001), and e-cigarette desire (time: beta [SE] = 3.71 [1.04],p < .001; seeTable 2). These increases were evident immediately after the cue and persisted 20 minutes later (ps < .001). Results remained after including smoking level and past ENDS history as covariates.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that passive exposure to a second generation ENDS vape pen increases smoking urge and desire, as well as e-cigarette desire, across a range of young adult smokers. These effects were similar to that produced by a cigarette smoking cue. These smoking urge and desire increases from vape pen exposure also were similar to that produced by an ENDS first generation cigalike,28 and although desire for an e-cigarette was directionally lower with the vape pen than cigalike, there was no statistical difference between the two cue types. This is important as, relative to first generation cigalikes, newer generation ENDS show less resemblance to combustible cigarettes. However, vape pens may share enough salience in their design and function to render them generalizable as a smoking cue. Advanced generation ENDS products may possess similar stimulus control as regular cigarettes leading to smoking desire and behavior associated with anticipation of the positive outcome (ie, nicotine effects). Finally, the aforementioned smoking urge and desire and e-cigarette desire effects were observed regardless of ENDS past use history which may render passive ENDS exposures as active cues in ENDS current users, past users, and nonusers.

The ENDS vape pen also produced a similar latency to smoke as the cigarette cue. To our knowledge, this was the first investigation to examine ENDS cue reactivity beyond subjective report to include an objective measure of smoking behavior. This behavioral measure, taken from the Smoking Lapse Paradigm, examined time to initiate smoking behavior versus receiving a monetary reward, and results demonstrated similar latencies to smoke during the 50 minute task interval after exposure to vape pen use relative to the regular cigarette, that is, a known potent smoking cue. Of note for the combustible cigarette cue, it not only increased desire for a cigarette, but also desire for an e-cigarette, which was not observed in our previous study conducted several years ago.28 It is possible that cross-cue reactivity, that is, combustible and e-cigarettes each increasing desire for the other product, may be increasing over time as population trends show rising levels of ENDS experimentation in youth,9 associations of ENDS to future use of other tobacco products,23,24 and greater dual use of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes than sole use of e-cigarettes.5,54 In addition to greater everyday e-cigarette exposures due to the growth in ENDS popularity,3,4 advertisements for e-cigarettes, which also affect cigarette urges,29,30,31 often employ imagery used in cigarette advertising to attract smokers and appeal to youth for ENDS products.8−11 These visual exposures may contribute to blurring the lines of distinction between products.

There are several strengths of the current study, including measuring responses in a controlled environment without other smoking cues or behavior present, examining a wider range of smoking levels than in previous studies while maintaining ethnic/racial diversity in the young adult sample, and employing a behavioral measure of smoking to extend the data beyond subjective reports. However, there were also some limitations worth noting. First, cue reactivity was assessed in the laboratory within a social encounter to mimic real-life passive ENDS exposure situations, so the extent to which these findings relate to other social and non-social real-world contexts is yet unknown. Second, while this was the first ENDS laboratory analogue study to include lighter smokers as well as regular daily smokers, the sample was nonetheless small and limited to young adults aged 18–35 years. Thus ENDS cue reactivity effects in former and middle-aged/older smokers are unknown, and the role of ENDS past use versus non-use on responses will remain unknown until larger studies are conducted. Third, smoking behavior following the active cues was explored in only a subset of the sample. Therefore, replication in a larger study will be necessary before drawing firm conclusions. Finally, cues were presented in fixed order with the control cue always preceding the active cue(s). Future research with counterbalanced cue presentation and/or multiple sessions will ensure that time-dependent effects are controlled. However, given that the neutral control and active cues were presented only 20 minutes apart, it is unlikely that the passage of time produced the sharp increases in smoking urge after the active cue(s).

In sum, the current study demonstrated that passive exposure to ENDS vape pen use increased smoking urge and behavior in a range of young adult smokers. While the impact of the increasing popularity of ENDS remains inconclusive,2,55 we surmise that the current findings are reflective of the salience of ENDS features as a smoking cue. This is particularly relevant in regard to second generation vape pens which are designed to deliver a more customized nicotine hit and flavoring options rather than simply to resemble combustible cigarettes, that is, as with first generation cigalikes. If the current study findings are replicated in larger samples and extended to other advanced third generation ENDS products, further support will be evident that the use of ENDS products, across a broad range of device types, may serve as a novel smoking cue. The specific active components of ENDS as a smoking cue may relate to a range of factors such as the frequency hand-to-mouth movements, inhalation and exhalation behaviors, and the similarity of exhaled aerosol to combustible smoke. Thus, further research will be needed to examine the active components of ENDS cross-cue reactivity and whether passive exposures should be addressed as part of the equation in determining the overall harm versus benefit of ENDS in society.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available atNicotine & Tobacco Research online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience Research Fund (ACK) and #P30-CA014599.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended the following individuals for assistance with data collection and study parameters: Ifeoma Echeazu, Eric Giger, Patrick Smith, Jennan Qato, and Caroline Volgman.

References

- 1. Benowitz NL, Goniewicz ML.The regulatory challenge of electronic cigarettes.JAMA.2013;310(7):685–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.109501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKee MC, Capewell S.Evidence about electronic cigarettes: a foundation build on rock or sand?BMJ.2015;351:h4863. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults: United States, 2014.Hyattsville, MD:Centers for Disease Control;2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Gerovasili V, Vardavas CI.Two-year trends and predictors of e-cigarette use in 27 European union member states.Tob Control.2016;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015–052771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United States Department of Health and Human Services.National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Drug Abuse, and United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Tobacco Products. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files. ICPSR36498-v1.Ann Arbor, MI:Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor];2016. doi:10.3886/ICPSR36498.v1 Accessed October 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J.Young adults’ favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: findings from a focus group study.Am J Public Health.2012;102(11):2088–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chu KH, Sidhu AK, Valente TW.Electronic cigarette marketing online: a multi-site, multi-product comparison.JMIR Public Health Surveill.2015;1(2):e11. doi:10.2196/publichealth.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, et al. Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults.Pediatrics.2014;134(1):e29–e36. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).Notes from the field.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2013;62(35):729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN.Electronic cigarettes: a new tobacco industry?Tob Control.2011;20(1):81.doi:10.1136/tc.2010.038562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K, Dixon D, Purves R.The marketing of electronic cigarettes in the UK2013www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/ files/cruk_marketing_of_electronic_cigs_nov_2013.pdf Accessed August 15, 2016.

- 12. Lee YO, Kim AE.Vape shops and e-cigarette lounges open across the USA to promote ENDS.Tob Control.2015;24(4):410–412. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013–051437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells Fargo Securities.Equity Research: Tobacco-Nielsen C-Store Data E-cig Sales Decline Moderates2014www.c-storecanada.com/attachments/article/153/ Nielsen%20C-Stores%20-%20Tobacco.pdf. Published 2014 Accessed March 23, 2016.

- 14. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA.E-cigarettes: a scientific review.Circulation.2014;129(19):1972–1986. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen C, Zhuang YL, Zhu SH.E-cigarette design preference and smoking cessation: a U.S. population study.Am J Prev Med.2016;51(3):356–363. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herzog B.U.S. tobacco trends: disruptive innovation should drive outsized growth2014www.ecigarette-politics.com/files/WF-DallasMarch2014.ppt Accessed March 23, 2016.

- 17. Yingst JM, Veldheer S, Hrabovsky S, Nichols TT, Wilson SJ, Foulds J.Factors associated with electronic cigarette users’ device preferences and transition from first generation to advanced generation devices.Nicotine Tob Res.2015;17(10):1242–1246. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooper M, Harrell MB, Perry CL.Comparing young adults to older adults in e-cigarette perceptions and motivations for use: implications for health communication.Health Educ Res.2016;31(4):429–438. doi:10.1093/her/cyw030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farsalinos KE, Le Houezec J.Regulation in the face of uncertainty: the evidence on electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes).Risk Manag Healthc Policy.2015;8:157–167. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S62116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nitzkin JL.The case in favor of E-cigarettes for tobacco harm reduction.Int J Environ Res Public Health.2014;11(6):6459–6471. doi:10.3390/ijerph110606459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zeller M.Reflections on the endgame for tobacco control.Tob Control.2013;22(suppl 1):40–41. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012–050789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iacobucci G.WHO calls for ban on e-cigarette use indoors.BMJ.2014;349:g5335. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider S, Diehl K.Vaping as a catalyst for smoking? An initial model on the initiation of electronic cigarette use and the transition to tobacco smoking among adolescents.Nicotine Tob Res.2016;18(5):647–653. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence.JAMA.2015;314(7):700–707. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abrams DB, Monti PM, Carey KB, Pinto RP, Jacobus SI.Reactivity to smoking cues and relapse: two studies of discriminant validity.Behav Res Ther.1988;26(3):225–233. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(88)90003–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drobes DJ, Tiffany ST.Induction of smoking urge through imaginal and in vivo procedures: physiological and self-report manifestations.J Abnorm Psychol.1997;106(1):15–25. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shiffman S, Dunbar MS, Kirchner TR, et al. Cue reactivity in non-daily smokers: effects on craving and on smoking behavior.Psychopharmacology (Berl).2013;226(2):321–333. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2909-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. King AC, Smith LJ, McNamara PJ, Matthews AK, Fridberg DJ.Passive exposure to electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use increases desire for combustible and e-cigarettes in young adult smokers.Tob Control.2015;24(5):501–504. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014–051563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King AC, Smith LJ, Fridberg DJ, Matthews AK, McNamara PJ, Cao D.Exposure to electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) visual imagery increases smoking urge and desire.Psychol Addict Behav.2016;30(1):106–112. doi:10.1037/adb0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, Nonnemaker J, Makarenko O.Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems.Tob Control.2013;24(2):132–135. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013–051130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maloney EK, Cappella JN.Does vaping in e-cigarette advertisements affect tobacco smoking urge, intentions, and perceptions in daily, intermittent, and former smokers?Health Commun.2015;31(1):129–138. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.993496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Green MP, McCausland KL, Xiao H, Duke JC, Vallone DM, Healton CG.A closer look at smoking among young adults: where tobacco control should focus its attention.Am J Public Health.2007;97(8):1427–1433. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.103945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanders-Jackson A, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP.Effect of warning statements in e-cigarette advertisements: an experiment with young adults in the United States.Addiction.2015;110(12):2015–2024. doi:10.1111/add.12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG.The measurement of drug craving.Addiction.2000;95(suppl 2):S189–S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perkins KA.Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence?Addiction.2009;104(10):1610–1616. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carter BL, Tiffany ST.Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research.Addiction.1999;94(3):327–340. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9433273.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO.The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire.Br J Addict.1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Follow-Back Users’ Manual.Toronto, Canada:Addiction Research Foundation;1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J.An inventory for measuring depression.Arch Gen Psychiat.1961;4(6):561–671. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spielberger CD, Gornich KL, Lushene RE. Stai Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.Palo Alto, CA:California Consulting Psychologists Press;1969. [Google Scholar]

- 41. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P).New York, NY:Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute;1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Niaura R, Abrams DB, Pedraza M, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ.Smokers’ reactions to interpersonal interaction and presentation of smoking cues.Addict Behav.1992;17(6):557–566. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(92)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McKee SA.Developing human laboratory models of smoking lapse behavior for medication screening.Addict Biol.2009;14(1):99–107. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McKee SA, Weinberger AH, Shi J, Tetrault J, Coppola S.Developing and validating a human laboratory model to screen medications for smoking cessation.Nicotine Tob Res.2012;14(11):1362–1371. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pang RD, Leventhal AM.Sex differences in negative affect and lapse behavior during acute tobacco abstinence: a laboratory study.Exp Clin Psychopharmacol.2013;21(4):269–276. doi:10.1037/a0033429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leventhal AM, Trujillo M, Ameringer KJ, Tidey JW, Sussman S, Kahler CW.Anhedonia and the relative reward value of drug and nondrug reinforcers in cigarette smokers.J Abnorm Psychol.2014;123(2):375–386. doi:10.1037/a0036384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roche DJ, Bujarski S, Moallem NR, Guzman I, Shapiro JR, Ray LA.Predictors of smoking lapse in a human laboratory paradigm.Psychopharmacology (Berl).2014;231(14):2889–2897. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Strong DR, Leventhal AM, Evatt DP, et al. Positive reactions to tobacco predict relapse after cessation.J Abnorm Psychol.2011;120(4):999–1005. doi:10.1037/a0023666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bold KW, Yoon H, Chapman GB, McCarthy DE.Factors predicting smoking in a laboratory-based smoking-choice task.Exp Clin Psychopharmacol.2013;21(2):133–143. doi:10.1037/a0031559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG.Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings.Nicotine Tob Res.2001;3(1):7–16. doi:10.1080/14622200124218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Heishman SJ, Lee DC, Taylor RC, Singleton EG.Prolonged duration of craving, mood, and autonomic responses elicited by cues and imagery in smokers: effects of tobacco deprivation and sex.Exp Clin Psychopharmacol.2010;18(3):245–256. doi:10.1037/a0019401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.New York, NY:Psychological Cororporation;1955. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tse WS, Bond AJ.Development and validation of the two-dimensional social interaction scale (2DSIS).Psychiatry Res.2001;103(2–3):249–260. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dunlop S, Lyons C, Dessaix A, Currow D.How are tobacco smokers using e-cigarettes? Patterns of use, reasons for use and places of purchase in New South Wales.Med J Aust.2016;204(9):355. doi:10.5694/mja15.01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Abrams DB.Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete?JAMA.2014;311(2):135–136. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.285347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.