The severity of COVID-19 infection varies greatly (1). The principal route of transmission of the causative pathogen, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is thought to be person-to-person spread via droplet infection (2).

Münster University Hospital (UKM) is a tertiary care center with 1500 beds and around 11 000 employees (including roughly 1250 physicians). The first patient with COVID-19 was diagnosed at UKM on 29 February 2020 (3); he was admitted to the hospital. Up to 17 April 2020, 242 persons tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at UKM and 37 of these patients had to be admitted for treatment of COVID-19. In common with many other hospitals, UKM has faced challenges in protecting staff members and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. To improve protection beyond that provided by basic hygiene measures, on 23 March 2020 it became compulsory for all employees and visitors to keep their mouth and nose covered while on the hospital premises.

In the following, we analyze and discuss the results of SARS-CoV-2 testing among our hospital staff.

Methods

Clinical and epidemiological data on UKM employees were collected from 11 March 2020 to 17 April 2020. Employees with suspected exposure to SARS-CoV-2 according to the valid case definition of the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) either reported to the Occupational Health Department at UKM themselves or their exposure to a SARS-CoV-2–positive patient was revealed during contact tracing by UKM’s infection control specialists.

In accordance with the current RKI case definition, the employees were asked whether they had (4):

Spent time in a risk zone

Come into contact with confirmed cases of COVID-19 or known COVID-19 clusters.

The participants were asked whether they had experienced one or more of ten symptoms (table). If laboratory tests were indicated, naso-oropharyngeal swabs were obtained within 24 hours and subjected to quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for detection of SARS-CoV-2 (5). Employees who tested positive were followed up with periodical laboratory tests. Exposed patients were accommodated in single rooms and their clinical symptoms were monitored by infection control specialists. Any of these patients who showed symptoms typical of COVID-19 were tested for SARS-CoV-2, thus identifying possible clusters of infection.

Table. SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis in UKM employees (11 March – 17 April 2020).

| Characteristic | Number of employees(% [95% CI]) |

|

Total tested Positive qRT-PCR |

957 52 (5.4 [4.2; 7.1]) |

|

Symptoms at time of swab Cough Sore throat Cold Dyspnea Fever Fatigue Headache Muscle/joint pain Disturbance of smell/taste Diarrhea Contact with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case – private – at work (patient/employee) Return from high-risk area Cluster* Positive qRT-PCR – 14 days’ quarantine completed – positive qRT-PCR >14 days after initial positive test |

523 (54.6 [51.5; 57.8]) 345 (66.0 [61.8; 69.9]) 309 (59.1 [54.8; 63.2]) 276 (52.8 [48.5; 57.0]) 69 (13.2 [10.6; 16.4]) 78 (14.9 [12.1; 18.2]) 11 (2.1 [1.2; 3.7]) 191 (36.5 [32.5; 40.7]) 72 (13.8 [11.1; 17.0]) 23 (4.4 [2.9; 6.5]) 35 (6.7 [4.9; 9.2]) 227 (43.4 [39.3; 47.7]) 76 (33.5 [27.7; 39.9]) 151 (66.5 [60.2; 72.3]) 59 (11.3 [8.8; 14.3]) 9 (1.7 [0.9; 3.2]) 22 (4.2 [2.8; 6.3]) 20 (90.9 [72.2; 97.5]) 10 (45.5 [26.9; 65.3]) |

|

No symptoms at time of swab Contact with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case – private – at work (patient/employee) Return from high-risk area Cluster* Positive qRT-PCR – 14 days’ quarantine completed – positive qRT-PCR >14 days after initial positive test |

434 (45.4 [42.2; 48.5]) 304 (70.0 [65.6; 74.2]) 59 (19.4 [15.4; 24.2]) 245 (80.6 [75.8; 84.6]) 83 (19.1 [15.7; 23.1]) 26 (6.0 [4.1; 8.6]) 30 (6.9 [4.9; 9.7]) 23 (76.7 [59.1; 88.2]) 17 (56.7 [39.2; 72.6]) |

*Accumulation of two or more infections in immediate environment

qRT-PCR, Quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Results

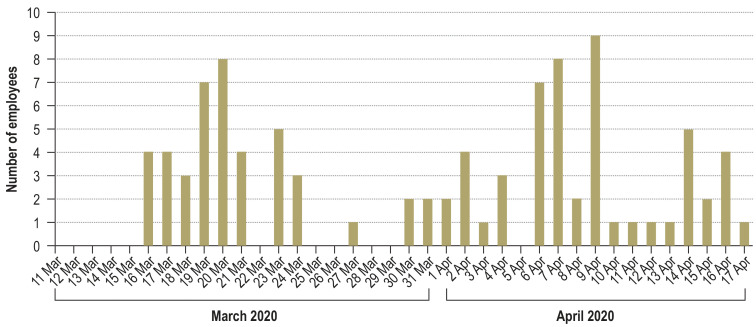

A total of 1054 swabs from 957 UKM employees (38.7% male; median age 35 years, interquartile range 20 years) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 during the study period. Fifty-two employees (5.4%) tested positive (figure), 33 of whom had had direct contact with patients. The valid RKI definition for a suspected case of SARS-CoV-2 changed during the study period, and with it the indication for SARS-CoV-2 swab testing. Initially, at the time of the first swab, only slightly more than half of the employees (54.6%) reported typical symptoms. Details of the symptoms reported by the employees can be found in the Table. Altogether, 531 employees reported contact with a person tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (74.6% at work, 25.4% elsewhere). Among the employees who tested positive, 39 had been in contact with a positively tested person, and 21 of these 39 cases involved contact at work (patients n = 1, other employees n = 20). The most frequently occurring symptoms in employees who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were cough (n = 17), sore throat (n = 11), and headache (n = 9). Of 51 employees who were also tested for other respiratory viruses, 19 had positive results (rhinoviruses n = 9, other coronaviruses n = 4, influenza A n = 3, human metapneumovirus [HMPV] n = 2, adenoviruses n = 1). Epidemiological follow-up identified no nosocomial person-to-person (employee/patient) transmission after mask wearing became compulsory.

Figure.

SARS-CoV-2-positive employees:

The numbers of employees with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 during the study period. The graph includes two or more positive tests for some employees.

Discussion

The results of this SARS-CoV-2 study on 934 UKM employees show that hospital personnel can form part of COVID-19 infection clusters both at work and elsewhere.

The strategy at UKM was to establish the infection status of employees soon after exposure. This policy meant that 885 employees who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 could continue their normal work, ensuring adequate coverage especially in critical areas of medical care.

However, about 52% (n = 27) of the UKM employees who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 still had fragments of SARS-CoV-2 detected on PCR 14 days later. These follow-up examinations clearly show that health system employees may still be a source of SARS-CoV-2 transmission after the end of the quarantine period, although it has not yet been ascertained just how infectious such employees are or when they can be permitted to return to work. This should be addressed in future research.

Among the first 51 employees tested for SARS-CoV-2, extended diagnostic procedures detected 19 cases of infection with other respiratory pathogens. With regard to prevention of infection, the demonstration of influenza A in three employees is striking. Although no vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 is yet available, the experience with vaccination against influenza suggests that universal vaccination of all hospital staff may present challenges.

In conclusion, we believe that epidemiological follow-up, a low threshold for virological testing, and enforcement of stricter than normal standards of hygiene helped to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by and to employees in our hospital. Nevertheless, prospective randomized controlled trials are necessary to confirm the efficacy of these measures.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correa-Martinez CL, Kampmeier S, Kumpers P, et al. A pandemic in times of global tourism: superspreading and exportation of COVID-19 cases from a ski area in Austria. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00588-20. JCM00588-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Koch-Institut. Neuartiges Coronavirus Falldefinition. www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Falldefinition.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last accessed on 16 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. 2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]