Abstract

As the proportion of older adults in the United States is projected to increase dramatically in the coming decades, it is imperative that public health address and maintain the cognitive health of this growing population. More than 5 million Americans live with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) today, and this number is projected to more than double by 2050. The public health community must be proactive in outlining the response to this growing crisis. Promoting cognitive decline risk reduction, early detection and diagnosis, and increasing the use and availability of timely data are critical components of this response. To prepare state, local, and tribal organizations, CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association have developed a series of Road Maps that chart the public health response to dementia. Since the initial Healthy Brain Initiative (HBI) Road Map release in 2007, the Road Map has undergone two new iterations, with the most recent version, The HBI’s State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map, released in late 2018. Over the past several years, significant advances were made in the science of risk reduction and early detection of ADRD. As a result, the public health response requires a life-course approach that focuses on reducing risk and identifying memory issues earlier to improve health outcomes. The most recent Road Map was revised to accommodate these strides in the science and to effect change at the policy, systems, and environment levels. The 2018–2023 Road Map identifies 25 actions that state and local public health agencies and their partners can implement to promote cognitive health and address cognitive impairment and the needs of caregivers. The actions are categorized into four traditional domains of public health, and the Road Map can help public health and its partners chart a course for a dementia-prepared future.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Aging, Brain health, Caregiving, Chronic conditions, Cognitive decline, Comorbidities, Health policy

Translational Significance:

This article describes the importance of addressing Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) as a public health issue and the steps that states, local, tribal, and other partners can take to stimulate systems level changes to prepare the nation for an aging population and reduce the burden of ADRD.

Description of Topic and Significance to Aging and Life Course

Dementia as a Public Health Problem

As the proportion of older adults in the United States is projected to increase dramatically in the coming decades, it is imperative that public health address and maintain the cognitive health of this growing population (1,2). It is estimated that by 2030, one in five Americans will be 65 years and older (3). These shifting demographics will necessitate that public health communities address aging-related topics, such as dementia, that have traditionally been viewed as gerontological rather than public health issues. The public health community, including state and local health agencies, non-profits, and other partners, can incorporate cognitive health strategies into many existing public health efforts in order to prepare for and reduce the impact of dementia. Dementia is a general term for the symptomology relating to the loss of cognitive function, often resulting in memory issues, that interferes with daily life. Although the risk for developing dementia increases with age, these significant cognitive deficits experienced as a result of dementia should not be equated with the normal aging process. Although dementia has multiple causes, it is estimated that between 60% and 80% of all cases of dementia are caused by Alzheimer’s disease (4). Alzheimer’s disease is just one of multiple conditions that can lead to dementia. The term Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) typically refers to a group of closely linked health conditions that can lead to dementia. These include Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia, and mixed etiology dementias, that is, those dementias with multiple causes (5).

In the United States, more than 5 million people currently live with ADRD (4). Alzheimer’s disease alone is the sixth leading cause of death among all Americans and the fifth leading cause of death among older adults (6). When grouped together with other dementias, Alzheimer’s and related dementias are the third leading cause of death among all ages (7). ADRD remains the only top 10 leading cause of death in the United States with no treatment or cure (4). Although the mortality rates associated with many other infectious and chronic diseases have been decreasing in recent years, death rates for ADRD have increased 54.4% from 1999 to 2014 (8). By 2030, the number of older Americans with ADRD is expected to reach approximately 8.4 million then 14 million by 2060 (9,10).

The cost to health and long-term care systems for ADRD is estimated to reach $290 billion in 2019, making this collection of dementias the most costly disease in America (4). Beyond the costs to health care systems, caring for those with ADRD often falls on informal caregivers, who are unpaid family members or friends who assist persons with ADRD with their activities of daily living and management of comorbidities. These include necessities such as dressing, eating, and addressing mobility issues. Informal caregivers also help with instrumental activities of daily living, for instance, assisting with shopping, cleaning, and managing finances. Often caregivers spend significant portions of their time providing care; the average caregiver provides about 62 hours of care per week (11). In addition to caring for the person needing assistance, about a quarter of all caregivers provide care to their own children (11,12).

Where Public Health Can Help

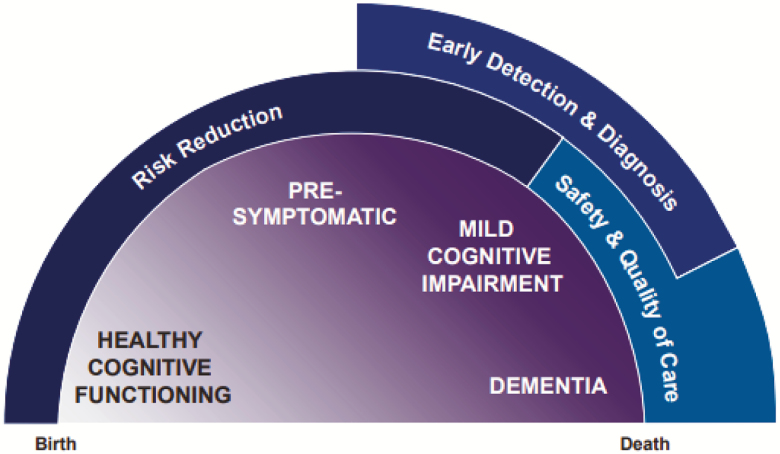

Although there is currently no cure for ADRD, there are many opportunities for public health action to improve outcomes for persons with ADRD, their families, and caregivers. The ADRD continuum spans decades (Figure 1). This continuum includes healthy cognitive functioning through the beginning and into the middle stages of life. During middle life, people may experience a decline in cognitive functioning. This cognitive decline may be, but is not always, a precursor to more severe cognitive impairment and eventually ADRD (13,14).

Figure 1.

Life-course perspective on Alzheimer’s and related dementias and the role of public health. CDC and Alzheimer’s Association. State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

During the period of healthy cognitive functioning—in the beginning and middle stages of life—the public health community can promote healthy behaviors that reduce the risk for ADRD before symptoms of declining cognitive function first appear. This includes promoting management of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension that appear critical to preserving cognitive function (15–17). Individuals should also be encouraged to avoid or quit smoking and to manage mid-life obesity as these factors may lead to increased risk for ADRD (15,16). It is estimated that about one third of all new ADRD cases could be averted as a result of eliminating modifiable risks (18). At the onset of symptoms of cognitive decline, the public health community can encourage persons experiencing worsening memory to speak with a health care provider, and providers can initiate conversations about cognitive health, especially as patients reach mid-life and older. Early detection of cognitive impairment can help improve the quality of care for patients and identify whether the symptoms are caused by other treatable conditions such as delirium, pressure or bleeding in the brain, vitamin deficiencies, or depression. Often, dementia manifests with a multitude of biological markers and symptoms that are characteristic of multiple types of dementia and result from a mixed etiology; this can make mapping a diagnosis to one type of dementia difficult. However, for those who receive a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or a related dementia, early diagnosis can ensure the safety of patients, including avoiding preventable hospitalizations, help to identify caregivers, and plan financially (19–21). Public health communities that employ strategies focusing on these essential public health activities can help to reduce the burden, improve health outcomes, and promote health and well-being among people living with dementia, their families, and their caregivers. Public health strategies at the systems, policies, and environment levels, including conducting public education campaigns, improving core competencies for health professionals, and utilizing population-based data to set priorities are a few ways in which public health communities can promote these improvements.

Public Health Road Maps for Addressing Dementia

In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Alzheimer’s Association partnered to promote dementia as a public health issue. These promotion efforts included the creation of the first Healthy Brain Initiative (HBI) Road Map in 2007, with input from critical partners such as the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, the National Institute on Aging, AARP, and numerous other experts and stakeholders in the areas of aging and dementia (1). The first HBI Road Map was designed to provide state and local public health professionals with practical and expert-guided actions to address memory problems. The science on ADRD continues to rapidly evolve. Every five years, new Road Maps to address dementia are developed and released in order to update the recommended actions to reflect recent advances in knowledge and accomplishments in the field. It is also vital that the Road Map remains adaptive to changes to health care systems, policies, and environments and can accommodate variable capacity and contexts of states and local partners.

Drawing upon the work of the first HBI Road Map, two subsequent iterations have been released. In the fall of 2018, CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association released the third edition of the Road Map: The HBI’s State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map (22). In contrast to previous iterations of the HBI Road Map, the newest version of the Road Map focuses on stimulating change at the policy, systems, and environment levels among states and local partners. Enhanced to promote public health and health care systems level changes and to be more useful to partners, the number of actions in the 2018–2023 Road Map was pared down from 35 actions in the second version (2013–2018) to the 25 actions deemed most critical for states and local partners to implement (22). These actions are focused in four areas: educating and empowering the nation, developing policies and mobilizing partnerships, assuring a competent workforce, and monitoring and evaluating. The 2018–2023 Road Map materials include dissemination and planning guides, an online resource library to support implementation at alz.org/publichealth, and five topic-specific issue maps (risk reduction, early diagnosis, caregiving, data use, and workforce competency) to highlight issue priorities in a quick-read format (22).

State of the Science

The HBI’s State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map

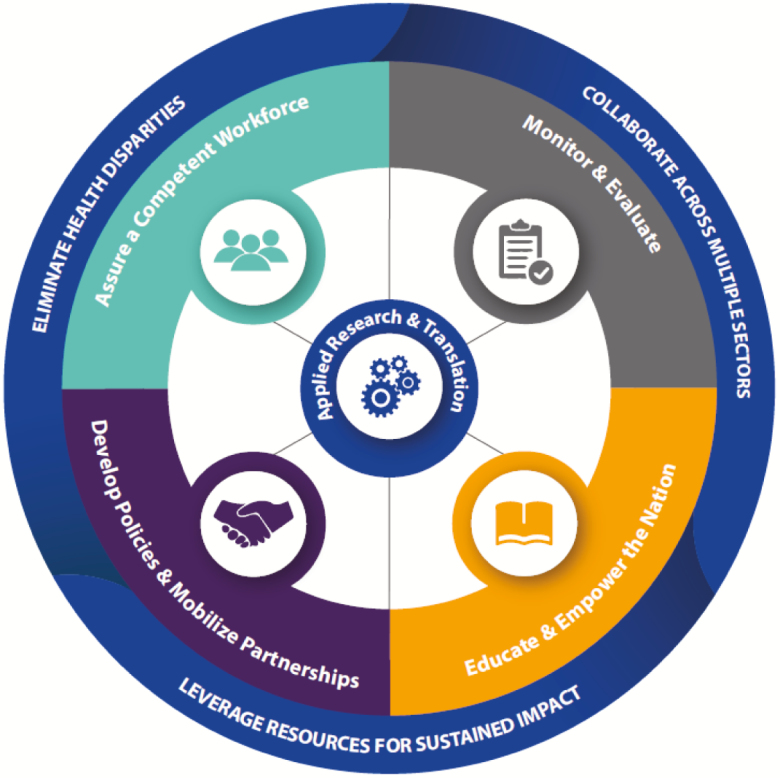

In developing the 2018–2023 HBI Road Map, a population health approach, grounded by the concept of a public health system, was applied to addressing the issue of dementia (23,24). The Road Map approach draws upon the 10 Essential Public Health Services framework described in the Institute of Medicine reports on public health and informed by the CDC’s National Public Health Performance Standards (23–27). The Institute of Medicine identified assessment, policy development, and assurance as the three core functions of public health agencies at all levels: federal, state, and local (23,25). Within this framework, there are 10 identified essential services of public health that align with these three core functions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ten Public Health Essential Services conceptual framework. Creative Services, CDC. 10 essential public health services graphic. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

Similarly, in developing the Road Map, three core principles were identified as central to the success of public health agencies and partners in addressing the public health dilemma of dementia. These core principles are to eliminate health disparities, collaborate across multiple sectors, and leverage resources for sustained impact (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

2018–2023 Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map conceptual framework. CDC and Alzheimer’s Association. State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2018.

The Road Map framework encourages public health leaders to concentrate resources toward reducing health disparities among those most likely to be affected by dementia. These populations include older adults, women, African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and individuals with developmental disabilities; all of whom have increased risk for ADRD compared with other populations (4,10). To reduce disparities among these populations, access to and improvement in the quality of care, including the use of culturally, linguistically, and age-appropriate prevention strategies, are necessary (28). Partnering with organizations with strong ties to these populations can improve intervention effectiveness and increase impact on disparities. Throughout planning and implementation of programs and initiatives aiming to eliminate disparities, accurate and timely data and community involvement should be used to inform these prevention strategies.

At the population level, increasing collaboration across sectors is central to making and maintaining progress toward improving health and quality of life for those affected by dementia (22,29). As ADRD progressively affects people, they and their caregivers, will tend to need support from multiple systems—health care, human services, aging network, employers, faith-based groups, and more. It is also important that these partnerships build upon one another so as to maximize impact toward achieving this common goal. Public/private partnerships at all levels of society provide a way for available resources to be leveraged in an efficient manner that minimizes duplication, builds capacity, and creates synergistic benefits (29).

Grounded in these three core principles, the Road Map is categorized into four overarching public health service actions: educate and empower, develop policies and mobilize partnerships, assure a competent workforce, and monitor and evaluate. Applied research and translation—at the center of this framework—are essential to move bench science and surveillance to real-world action and to attain widespread adoption of effective interventions.

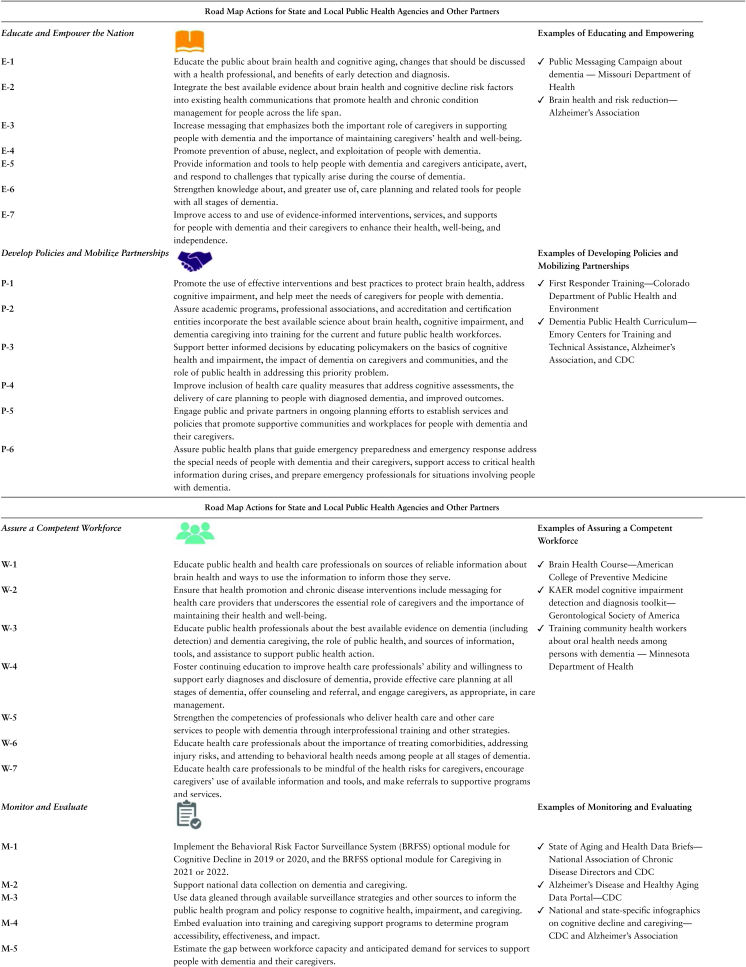

Educate and empower the nation

Education is a critical element to the success of public health in addressing dementia. Educating the public is a strategy that can shift attitudes to normalize discussions about cognitive health, including conversations about risk reduction and early detection of memory problems. Currently, initiating conversations about worsening memory issues may be difficult to talk about with family members and health care providers. Education can also help reduce stigma and false beliefs about dementia. Often people experiencing cognitive difficulties attribute these issues to normal aging processes and/or believe there are no steps to take to tackle ADRD-related challenges.

Informing the public about the importance of these conversations and normalizing them is critical to helping optimize cognitive functioning across the life span. These education strategies should include population-appropriate approaches and techniques that are culturally sensitive and effective (26). Within the 2018–2023 HBI Road Map, four specific actions focus on achieving an informed public about cognitive decline (Table 1). For example, one action is to integrate cognitive health messages into existing public health messages, such as those related to cardiovascular health, injury prevention, tobacco prevention and control, and nutrition and physical activity. An additional three specific actions focus on empowering persons with ADRD and caregivers. These actions include providing information and tools to anticipate and respond to challenges that arise during dementia, ensuring access to evidence-based interventions, and maintaining caregiver health.

Table 1.

2018–2023 Healthy Brain Initiative Road Map Actions and Example Public Health Implementations

Some states have had success implementing actions concerning increasing and improving education of the public about cognitive decline. In Missouri, surveillance data suggested that the southeastern region of the state faced a higher risk of ADRD. As a result, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services conducted a multifaceted social marketing campaign directed at that region. The education campaign targeted families affected by ADRD, including both caregivers and persons experiencing worsening memory. The campaign included radio, Twitter, Pandora, and Facebook messages raising awareness of the early signs of dementia; encouraged calls to the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24/7 helpline for information, referrals to health care professionals, and assistance; and educated the public at-large about linkages between maintaining self-care and brain health (30). These messages reached about two thirds of local residents and of those who were exposed to the message, approximately 15% called the Alzheimer’s Association helpline or visited the Alzheimer’s Association website (30). Additionally, program planners in Missouri advocated for a related brain health and dementia education goal to be added to the state health improvement plan and were successful.

Develop policies and mobilize partnerships

Public health planning and policy initiatives related to cognitive decline may be developed at the systems or policy level to have a greater, enduring impact than individual interventions. The Road Map has six policy- or systems-focused actions (Table 1) that are prefaced with a call to use levers that result in systematic change. These actions relate to promoting effective cognitive decline interventions, assuring public health professionals are prepared to address dementia, educating policymakers about the basics of cognitive health, and improving the use of health care quality measures to account for the needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers. Because the current workforce has limited formal training, one such policy change would be to update public health competencies to include training for population-based approaches to achieving a dementia-prepared future (31,32).

To help prepare future public health professionals, a free public health curriculum for undergraduate public health courses was collaboratively developed and recently revised by the Alzheimer’s Association, CDC, and Emory Centers for Technical Training and Assistance. The curriculum, A Public Health Approach to Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias, is mapped to the core competencies for public health professionals, and faculty can use any or up to all four modules in teaching. A pilot evaluation found the modules increase awareness and knowledge about ADRD as a major public health issue (33).

Other opportunities for policy changes to improve care for persons with a dementia and their caregivers involve including quality measures that are specific to dementia in reimbursement and reporting. Dementia quality measures have been previously developed by the American Academy of Neurology Institute, the American Psychiatric Association Work Group, the Physician Consortium for Performance, and the National Quality Forum. Through the use of established quality improvement metrics, public health can in turn report on performance and inform policy (34). Additionally, leveraging policies already in place such as Medicare reimbursement codes for the use of prevention and screening services related to cognitive health during Welcome to Medicare visits and Annual Wellness Visits should be emphasized (12,35–38).

Creating supportive communities and workplaces for persons with dementia and their caregivers are also actions identified within the Road Map where policy and partnerships would accelerate change. Approximately one in four persons with ADRD are living alone, and 70% of those with ADRD live in community settings (4). When communities become more adept at supporting people living with cognitive impairment and their caregivers, gains are possible in health outcomes and quality of life; there is also the potential to reduce costs by limiting unnecessary hospitalizations and institutionalizations. In this vein, state and local partners can undertake emergency preparedness efforts that lessen the impact of emergencies on older adults while also maintaining their independence. Using a one-year grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment with the Alzheimer’s Association’s Colorado Chapter provided in-person trainings to help first responders act appropriately in situations where persons with dementia might be wandering, subject to abuse or neglect, or experiencing problems shopping. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment partnered with the state’s 11 regional Emergency and Trauma Advisory Councils, the Emergency Medical and Trauma Services Branch, and the State Emergency Medical and Trauma Services Advisory Council to promote the training. After completing the training, participants received a poster displaying tips for first responders in how to work with people with dementia (22,30).

Assure a competent workforce

Ensuring that public health professionals and the health care workforce are adequately trained and informed to address the growing dementia crisis is critical. Assuring that patients with diagnoses of cognitive impairment are comprehensively assessed and that health care and other professionals follow person-centered care principles is critical to improving health outcomes for those affected (39,40). Two actions in the Road Map focus on educating public health and health care professionals about evidence-based strategies for reducing the risk of cognitive decline and related management of chronic conditions (Table 1). To support these Road Map actions, the American College of Preventive Medicine and CDC partnered to develop an online course that provides physicians and health care professionals with an overview of strategies that can be used to promote brain health. The course includes a review of brain health terminology, lifestyle management strategies, and some of the risk factors for cognitive decline and includes an online brain health resource and technical assistance center. The course is free and is approved to be used toward continuing medical education credit (41).

Two additional Road Map actions relate to improving early detection and diagnosis of dementia. Improving detection and diagnosis should involve strategies to address low utilization of cognitive assessments and improve availability of credible information on the usefulness of early diagnosis in care planning and management. Although surveys have shown that both providers and patients recognize the importance of cognitive well-being as a concept, the percentage of older adults receiving regular assessments about difficulties with cognition significantly lags behind assessments for other health-related problems (4). Less than half of those experiencing worsening memory in the past year report talking with a health care provider about their cognitive difficulties (13).

Improving awareness of dementia diagnoses among patients and their caregivers and promoting conversations between patients and providers about worsening memory are part of the proposed set of Healthy People 2030 national objectives (42). To help primary care providers assess for cognitive impairment, the Gerontological Society of America developed the KAER toolkit for use. The KAER toolkit is designed to prepare primary care providers to initiate conversations about cognitive impairment, use validated tools, and become familiar with the recommended steps for evaluation and referral (43).

The Road Map also outlines three actions that can be taken to improve professional care for persons with dementia. These actions emphasize strengthening the competencies of care workers who provide services and educating them about the stages of dementia and to be mindful of the health and well-being of caregivers. Thinking innovatively, the Minnesota Department of Health considered how community health workers could be utilized to help family caregivers and others manage oral health among persons with dementia (30). The department then developed an educational module and partnered with training institutes for community health workers to train them in basic oral health care for older adults with attention to people living with dementia and its special challenges. Community health workers were provided with new flipcharts for use in educating caregivers about the oral health needs of family members in their care. The module has reached dozens of community health workers and students and informal caregivers. It has improved knowledge, attitudes, and practices among community health workers for engaging with ADRD populations (30).

Monitor and evaluate

Within the 2018–2023 Road Map, five actions concentrate on expanding and improving timely data surveillance and collection in order to inform national, state, and local decision making (Table 1). These data can be used to shape priorities, allocate resources efficiently, and identify gaps and disparities. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the world’s largest ongoing health survey, provides relevant data on demographics and health behaviors. The annual survey is administered in every state, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories (44). The BRFSS contains two optional modules—states can choose whether to administer the modules and during which years—that are especially useful in addressing issues relevant to dementia. The Cognitive Decline Module contains questions asking about self-reported memory difficulties experienced within the past year, how those difficulties may interfere with daily activities, and whether those memory difficulties have been discussed with a health care provider. The Caregiver Module asks about the characteristics of caregivers, health status of caregivers, and whether or not individuals who are not currently caregivers anticipate becoming caregivers in the near future (44).

Using data from the BRFSS Cognitive Decline and Caregiver modules, CDC’s Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Program and the Alzheimer’s Association have developed many user-friendly resources that states and other partners can use to inform strategies. Both organizations have produced national, state-specific, and racial/ethnic-specific infographics and fact sheets to facilitate widespread and easy access to some of the top-line results from this surveillance data. These BRFSS data on cognitive decline have been instrumental in persuading public health practitioners and policymakers to place a higher priority on addressing dementia. CDC and the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors have also produced data briefs focusing on public health issues specific to middle-aged and older adults (45). The first three, in a series of five planned, data briefs released covered cognitive decline, cardiovascular disease, and caregiving issues using BRFSS data. The briefs provide states and public health professionals with the most recent data available on brain health, the management of chronic conditions, and the burden of caregiving (45). Furthermore, CDC has made BRFSS data publicly available on its online Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Data Portal so that it can be easily accessed and used by researchers and others who are interested in examining associations between demographics, chronic conditions, and other health behaviors among older adults (46). The Alzheimer’s Association maintains a virtual online library with its own BRFSS publications, and its chapters partner with state governments to integrate the data into state plans and policy briefs.

Gaps in Understanding

The Road Map framework (Figure 3) identifies addressing health disparities related to dementia as critical to the success of the public health response. However, public health interventions, scientific knowledge, and data in this area continue to be insufficient. Prevalence data suggest that women have disproportionately higher rates of ADRD compared with men. The estimated lifetime risk for women of getting ADRD is nearly twice that of men (4). However, the scientific basis for this disparity is lacking. Further epidemiological research is needed to determine whether factors such as increased longevity among women and mid-life cardiovascular mortality rates among men alone are responsible for these differences or whether potential genetic and biological factors may be contributing to the disparity among sexes (4).

Recent data have suggested that African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians/Alaska Natives also experience higher risk of ADRD (10,47). Studies examining ADRD incidence in Indian Country have estimated that incidence rates are higher in American Indians/Alaska Natives than in Whites and that one in three American Indians/Alaska Natives aged 65 and older will receive a dementia diagnosis during the next 25 years (47). To address dementia in Indian Country within the context of the federal trust relationship with tribal nations, the Alzheimer’s Association and CDC partnered to release the first Indian Country specific Road Map. The HBI’s Road Map for Indian Country is designed to support discussion about dementia and caregiving within tribal communities and can be used as a tool for tribal leaders, such as tribal officials, tribal health and aging services professionals, and regional tribal health organizations. Based upon input from tribal health directors, practitioners, experts, and leaders, the Indian Country Road Map outlines eight strategies for addressing dementia (48).

Future Directions

The national public health response to dementia not only addresses the current needs in the United States but also prepares the nation for future developments with respect to ADRD. By laying the groundwork now, states and local partners can be prepared to move scientific developments and evidence-based innovations into practice for dementia risk reduction and care. For example, when better treatments for Alzheimer’s disease become available, including interventions that are effective if started before symptoms appear, this could necessitate that health care providers are able to identify those individuals who are most at risk or have biomarkers for the disease (49,50). Implementing Road Map actions can help states, local partners, and tribes build capacity now that can be leveraged in the future to improve outcomes for patients and their families.

Policymakers are beginning to recognize the importance of building a public health response to address the growing dementia crisis. In December 2018, the U.S. Congress passed the Building Our Largest Dementia Infrastructure Act (P.L. 115–406) that authorizes the CDC to establish ADRD Public Health Centers of Excellence and to support infrastructure in state, local, and tribal public health departments to address dementia (51). This new law aims to help public health promote cognitive health and to improve data analysis and timely reporting of data on cognitive decline to better inform public health actions.

Finally, as transformations within the U.S. health care system have led to an increased emphasis on patient-centered models of care, it is important to consider how these changes might affect and potentially improve quality of life for people experiencing cognitive decline, their families, and caregivers. Caring for persons with dementia is often complicated by other comorbid chronic conditions, with more than 85% of ADRD patients experiencing an additional chronic condition (49). Utilizing a patient-centered model of care such as a primary care medical home can be beneficial for coordinating and tailoring care for persons with ADRD and other comorbidities. Improved access and coordination of services may lead to reduced dependence on nursing home care, avoid unnecessary hospital visits, and improve independence and quality of life for patients and caregivers (52,53,54). Employing a public health systems level approach to addressing dementia that uses a life-course perspective emphasizing cognitive decline risk reduction and care planning can help prepare the nation for an aging population.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Alzheimer’s Association.

Conflicts of Interest

None reported.

References

- 1. Anderson LA, Egge R. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer's disease: the Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(suppl 5):S453–S456. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson LA, McConnell SR. Cognitive health: an emerging public health issue. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(S2):3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H; US Department of Commerce, Census Bureau An aging nation: the older population in the United States, population estimates and projections https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. 2014. Accessed February 4, 2019.

- 4. Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s and related dementias NIA Web site; https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers/related-dementias. Accessed August 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6):1–77. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_06.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramarow EA, Tejada-Vera B. Dementia mortality in the United States, 2000–2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(2):1–29. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_02-508.pdf. Accessed April 30, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor CA, Greenlund SF, McGuire LC, Lu H, Croft JB. Deaths from Alzheimer’s disease—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:521–526. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6620a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olivari BS, Baumgart M, Lock SL, et al. CDC Grand Rounds: promoting well-being and independence in older adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1036–1039. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6737a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Alliance for Caregiving; AARP Public Policy Institute. Caregiving in the U.S.https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving2015. 2015. Accessed March 15, 2019.

- 13. Taylor CA, Bouldin ED, McGuire LC. Subjective cognitive decline among adults aged ≥45 years—United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:753–757. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6727a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute of Medicine. Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group. Effect of intensive vs standard blood pressure control on probable dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):553–561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306–314. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1051–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Werner P, Karnieli-Miller O, Eidelman C. Current knowledge and future directions about the disclosure of dementia: a systematic review of the first decade of the 21st Century. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):e74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alzheimer’s Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy Brain Initiative, State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018–2023 Road Map. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harrell JA, Baker EL. The essential services of public health. Leadership Public Health. 1994;3(3):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Public Health Performance Standards Program (NPHPSP): 10 essential public health services CDC Web site; https://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html. 2018.. Accessed May 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baker EL, Melton RJ, Stange PV, et al. Health reform and the health of the public: forging community health partnerships. JAMA. 1994;272(16):1276–1282. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520160060044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Prevention Council; Office of the Surgeon General. Elimination of health disparities https://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/Action%20Plan.pdf. 2012. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- 29. Lavizzo-Mourey R; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation In it together-building a culture of health.https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/annual-reports/presidents-message-2015.html. 2015. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 30. Alzheimer’s Association. Public health – state overview Alzheimer’s Association Web site; https://www.alz.org/professionals/public-health/state-overview. Accessed August 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore MJ, Moir P, Patrick MM; The Merck Institute of Aging and Health The state of aging and health in America: 2004 https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/State_of_Aging_and_Health_in_America_2004.pdf. 2004. Accessed March 2019.

- 33. Alzheimer’s Association. Public health curriculum Alzheimer’s Association Web site; https://www.alz.org/professionals/public-health/core-areas/educate-train-professionals/public-health-curriculum-on-alzheimer-s. Accessed December 6, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Odenheimer G, Borson S, Sanders AE, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: dementia management quality measures. Neurology. 2013;81(17):1545–1549. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a956bf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, et al. Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare annual wellness visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alzheimer’s Association Expert Task Force. Cognitive assessment and care planning services: Alzheimer’s Association Expert Task Force recommendations and tools for implementation.Alzheimer’s Association Web site; https://www.alz.org/careplanning/downloads/cms-consensus.pdf. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Physician practices use software-facilitated system to complete Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, improving preventive care and generating high satisfaction AHRQ Web site; https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/physician-practices-use-software-facilitated-system-complete-medicare-annual-wellness-visitExternal. 2014. Accessed May 6, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A. Trends in use of the US Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, 2011–2014. JAMA. 2017;317:2233–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fazio S, Pace D, Maslow K, Zimmerman S, Kallmyer B. Alzheimer's Association dementia care practice recommendations. Gerontologist. 2018;58(suppl 1):S1–S9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM). Brain health course ACPM Web site; https://www.acpm.org/page/brainhealthcourse. 2019. Accessed January 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2030 Healthy People Web site; https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/ObjectivesPublicComment508_1.17.19.pdf. 2018. Accessed May 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gerontological Society of America (GSA). Cognitive impairment detection and earlier diagnosis GSA Web site; https://www.geron.org/programs-services/alliances-and-multi-stakeholder-collaborations/cognitive-impairment-detection-and-earlier-diagnosisExternal. 2014.. Accessed April 13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 44. BRFSS Web site http://www.cdc.gov/brfss. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- 45. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD). The State of Aging in America: data briefs CDC Web site; https://www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/data-portal/state-aging-health.html. 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Data Portal CDC Web site; https://www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/index.html. 2019.. Accessed August 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mayeda E, Glymour M, Quesenberry C, Whitmer R. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Alzheimer’s Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy Brain Initiative, Road Map for Indian Country. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:367–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Karlawish J, Jack CR Jr, Rocca WA, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC. Alzheimer’s disease: the next frontier-Special Report 2017. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. United States Congress. The Building Our Largest Dementia Infrastructure (BOLD) Act https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2076. 2018. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 52. Meyer H. A new paradigm slashes hospital use and nursing home stays for the elderly and the physically and mentally disabled. Health Aff. 2011;30(3):412–415. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meyers D, Peikes D, Genevro J, et al. The roles of patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations in coordinating patient care Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) white paper 11-M005-EF; https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Roles%20of%20PCMHs%20And%20ACOs%20in%20Coordinating%20Patient%20Care.pdf. 2010. Accessed August 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, Parchman M. Coordinating care for adults with complex care needs in the patient-centered medical home: challenges and solutions Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) white paper 12-0010-EF; https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/coordinating-care-for-adults-with-complex-care-needs-white-paper.pdf. 2012. Accessed August 14, 2019 [Google Scholar]