Abstract

Although prion diseases are generally thought to present as rapidly progressive dementias with survival of only a few months, the phenotypic spectrum for genetic prion diseases (gPrDs) is much broader. The majority have rapid decline with short survival but many present as slower progressive ataxic or parkinsonian disorders with progression over a few to several years. A few very rare mutations even present as neuropsychiatric disorders, sometimes with systemic symptoms such as gastrointestinal disorders and neuropathy, progressing over years to decades. Genetic prion diseases are caused by mutations in the prion protein gene (PRNP), and have been historically classified based on their clinicopathological features as genetic Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease (gJCD), Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS), or Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI). Mutations in PRNP can be missense, nonsense and octapeptide repeat insertions or a deletion. and present with diverse clinical features, sensitivities of ancillary testing and neuropathological findings. We present the UCSF gPrD cohort, including 129 symptomatic patients referred to and/or seen at UCSF between 2001 and 2016, and compare the features of the 22 mutations identified with the literature, as well as perform a literature review on most other mutations. E200K is the most common mutation worldwide, is associated with gJCD, and was the most common in the UCSF cohort. Among the GSS-associated mutations, P102L is the most commonly reported and was also the most common at UCSF. We also had several octapeptide repeat insertions (OPRI), a rare nonsense mutation (Q160X) and three novel mutations (K194E, E200G, and A224V) in our UCSF cohort.

Keywords: CJD, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, prion protein gene, rapidly progressive dementia, octapeptide repeat insertion

Introduction

Prion diseases (PrDs) are neurodegenerative disorders caused by transmissible proteins called prions, which stand for proteinaceous infectious particles[Prusiner 1982]. PrD have been reported not only in humans, but also in some mammals, such as sheep and goats (scrapie) and cattle (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), among others. Prion diseases occur when the prion protein (the normal conformation of the protein) or PrPC, in which C stands for the normal cellular form of the protein, is converted into a misshapen form called the prion, or PrPSc in which Sc stands for scrapie [Prusiner 1998].

Human PrDs are typically classified in three forms based on etiology: sporadic, genetic and acquired. Sporadic PrDs (sPrDs) are the most common form (about 85–90%) comprised primarily of sporadic Jakob-Creutzfeldt-disease (sJCD) which has several subtypes or molecular classifications [Brown and Mastrianni 2010; Parchi et al., 1999; Puoti et al., 2012] as well as a very rare, atypical form, variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSP) [Ladogana et al., 2005; Masters et al., 1979; Zou et al., 2010]. The first cases of JCD were reported by Alfons Jakob in 1921, whereas the patient reported by Hans Creutzfeldt one year prior we now know did not have prion disease [Masters 1989]. As Jakob believed at the time that his patients had similar features to the patient reported by Creutzfeldt, the eponym Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease was created. For many decades the disease was called Jakob’s disease or Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease (JCD), but a prominent researcher in the field C.J. Gibbs began using the term Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), so that the acronym would be closer to his own initials [Gibbs 1992]. Thus the proper term should probably be Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease (JCD) or even Jakob’s disease (JD) [Katscher 1998]. Thus, we will use the term Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease (JCD) in this article. It is important that the term JCD, however, not be confused with the JC virus, which is the cause of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and has nothing to do with prion disease.

Genetic PrDs (gPrDs) are caused by mutations in the gene, PRNP, that encodes the prion protein. Genetic PrDs account for about 10–15% of human PrDs [Kovacs et al., 2005; Ladogana et al., 2005; Masters et al., 1979]. Acquired PrDs are the rarest form (<1% of human PrD) and include Kuru, iatrogenic PrD and variant JCD (vJCD) [Brown et al., 2006; Ladogana et al., 2005; Masters et al., 1979; UK National CJD Surveillance Unit 2015]. This paper focuses on gPrDs.

Genetic prion disease background

Historically, gPrDs have been classified into three forms based on clinical and neuropathological features: familial JCD (fJCD, OMIM 123400), Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease (GSS, OMIM 137440) and Familial Fatal Insomnia (FFI, OMIM 600072). Familial JCD typically presents similar to sporadic JCD, as a rapidly progressive dementia with motor features resulting in death in about a few months (usually less than a year) from onset. Pathology also is often similar to sJCD with various patterns of PrPSc deposition (synaptic, granular or plaque-like pattern), vacuolation (spongiform changes), neuronal loss and gliosis; the severity of neuronal loss and gliosis might be related to disease duration [Gambetti et al., 2003a]. Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker usually presents as an ataxic disorder often with parkinsonian symptoms and dementia a bit later in the course. Survival is typically about three to 10 years, but some patients have a much shorter course. Pathology usually reveals prominent PrPSc amyloid plaques in the cerebellum and cortex [Gambetti et al., 2003a]. Persons with FFI usually develop prominent insomnia and dysautonomia, with cognitive impairment and motor features occurring later in the disease course. Median survival is about 18 months. The most severe pathology is neuronal loss and gliosis in the thalamus (thalamic atrophy), but also inferior olivary nucleus atrophy and gliosis in the midbrain and hypothalamic gray matter. Vacuolation and PrPSc deposition are sparse or often absent. The cortex is involved with longer duration cases [Gambetti et al., 2003a; Parchi et al., 1995]. This classification scheme of fJCD, GSS and FFI, however, was prior to the discovery of PRNP, and thus is somewhat outdated, as several PRNP mutations do not fit well into one of these three groups, as we discuss later.

Familial aggregation of PrD had been reported since the early 1900s, but it was only in 1989 that mutations in PRNP were shown to be causative of genetic PrD [Goldgaber et al., 1989; Hsiao et al., 1989; Owen et al., 1989]. Familial JCD (fJCD) was first reported by Meggendorfer in 1930, in a German kindred (the Backer family) that presented with rapidly progressive dementia and spongiform changes in the brain, and later was shown to carry a PRNP mutation (D178N-codon 129V; see below) [Kretzschmar et al., 1995]. In 1936, J. Gerstmann, E. Sträussler and I. Scheinker reported an Austrian kindred (the “H” family) that presented with slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and late dementia, with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, which is now considered the first known GSS family (PRNP P102L mutation identified later ) [Hainfellner et al., 1995]. The term FFI was first used by Lugaresi and colleagues in 1986, in the description of an Italian family with progressive insomnia, dysautonomia, motor signs and thalamic degeneration [Lugaresi et al., 1986]. The neuropathological findings suggested FFI was a PrD, but confirmation of it being genetic did not occur until 1992, when a PRNP D178N-codon 129M mutation was identified in the kindred [Medori et al., 1992]. The fact that the same mutation (D178N) could lead to two different phenotypes (fJCD or FFI) was puzzling at first, but soon later, Goldfarb et al. discovered that the PRNP codon 129 polymorphism found on the mutated (cis) allele could have a strong effect on the clinicopathological phenotype. FFI was typically associated with D178N and methionine at codon 129 and fJCD, with valine at codon 129 [Goldfarb et al., 1992].

The first pathogenic mutations identified in PRNP were missense [Goldgaber et al., 1989; Hsiao et al., 1989] but other types of mutations later were identified. Insertions, mostly octapeptide repeat insertions (OPRI) in the copper binding domain of PRNP, can lead to gJCD or GSS phenotypes and an two octapeptide deletion leads to a gJCD phenotype [Brown and Mastrianni 2010; Hinnell et al., 2011; Owen et al., 1990]. Nonsense or stop-codon mutations in PRNP were more recently identified, and have only been reported in a few kindreds. The clinical presentation of nonsense mutations is highly variable, but overall they are characterized by clinical features that are atypical for most PrDs and the presence of amyloid plaques and/or prion amyloid angiopathy [Fong et al., 2016a; Guerreiro et al., 2014; Mead et al., 2013].

Prion protein (PrP) and the prion protein gene (PRNP)

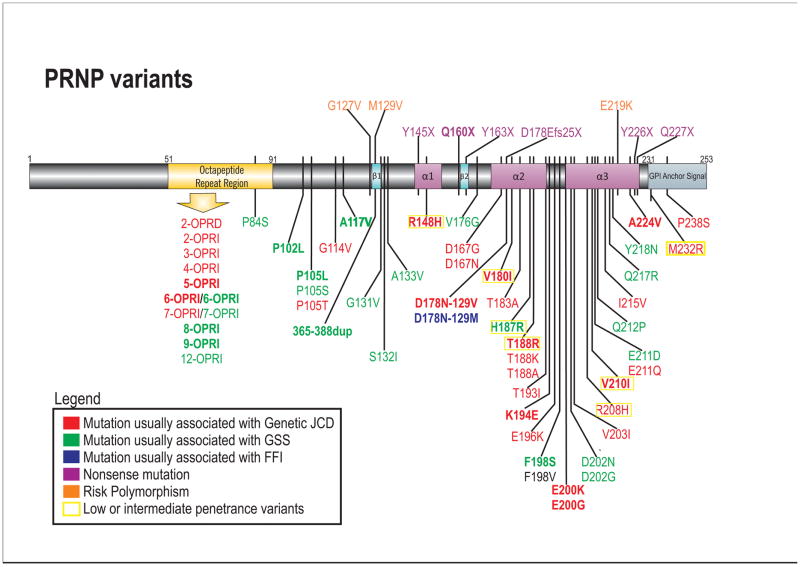

The PRNP (prion protein) gene is located in chromosome 20p13 and is composed of two exons. The entire open reading frame is in exon 2. The prion protein (PrP) has several isoforms, but the canonical sequence has 253 amino acids and contains an unstable region with repeats in the N-terminal domain, composed of a nonapeptide (Pro-Gln-Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly-Trp-Gly-Gln) followed by four repeats of an octapeptide (Pro-His-Gly-Gly-Gly-Trp-Gly-Gln) (Figure 1). Post-translational modifications include removal of 22 residues from the N-terminal and 23 residues from the C-terminal, attachment of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor in the C-terminal, and possible glycosylation. PrP can be un-, mono-, or di-glycosylated at asparagine residues 181 and/or 197 [Capellari et al., 2011; Yusa et al., 2012]. Regarding the structure of PrP, a globular domain extends from residues 125 to 228 and the normal protein contains three α-helices (residues 144–154, 173–194 and 200–228) and an anti-parallel β-sheet (residues 128–131 and 161–164) (Figure 1) [Zahn et al., 2000]. The tertiary structure of PrPC is influenced by hydrophobic and aromatic interactions between residues of the globular domain, as well as by the existence of salt bridges and disulfide bridges [Capellari et al., 2011; Giachin et al., 2013; van der Kamp and Daggett 2009].

Figure 1. Schematic of PRNP disease-associated variants.

Mutations are color coded based on clinicopathological classifcation as gJCD, GSS, FFI or nonsense mutations. PRNP mutations present in the UCSF cohort are in bold. Most mutations are shown below the gene schematic; nonsense mutations and polymorphisms associated with prion disease risk are above the gene schematic. Low or intermediate penetrance variants are based on Minikel et al., 2016 (not all low/intermediate penetrance variants are shown)[Minikel et al., 2016]. For the F198V mutation, the clinical presentation was not classifiable as gCJD, GSS or FFI (see Table 3), and neuropathology was not reported [Zheng et al., 2008]. Variants that are probably benign (largely based on Minikel et al., 2016) are not included (e.g., G54S, P39L, E196A, R208C) [Beck et al., 2010; Minikel et al., 2016].

JCD= Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease; GSS= Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker; FFI= Fatal Familial Insomnia. OPRI= Octapeptide repeat insertion; OPRD= Octapeptide repeat deletion.

Cellular PrP (PrPC) is typically attached to the plasma membrane by the GPI anchor, but eventually during its lifecycle, PrPC is internalized in endosomes [Harris 2003]. The repeat region in the N-terminal contains copper binding sites, which suggests PrPC might have a role in the copper homeostasis (Harris 2003). PrP genes are highly conserved across mammals, indicating PrP was important during evolution [Colby and Prusiner 2011]. Nonetheless, the biological function of PrPC is not entirely understood, although there are many putative roles [Bribian et al., 2012; Flechsig and Weissmann 2004; Watts and Westaway 2007].

The prion protein exists in multiple isoforms, two of which are relevant to PrD: the normal cellular isoform (PrPC) and the pathogenic infectious “scrapie” isoform (PrPSc). Both isoforms generally share the same amino acid sequence, but whereas PrPC structure is composed mainly of alpha-helix, PrPSc has a high beta-sheet content [Pan et al., 1993]. This conformational change affects PrP biochemical properties, so that PrPSc becomes insoluble in detergents and relatively resistant to degradation by proteases [Colby and Prusiner 2011; Mastrianni 2010]. According to Stanley Prusiner’s protein-only hypothesis, PrPSc has infectious properties and self-propagates by acting as a template in the misfolding of PrPC into PrPSc (Prusiner 1998). This hypothesis has now been essentially proven and might also apply to other neurodegenerative proteinopathies [Prusiner 2012; Soto 2011; Woerman et al., 2015]. It is not entirely clear where in the cell the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc occurs, but there is evidence suggesting this happens inside cholesterol-rich nonacidic intracellular compartments called caveolae-like domains [Colby and Prusiner 2011]. Many scientists believe the subsequent accumulation of PrPSc is the principal event that leads to neurodegeneration in PrD [Prusiner 2013], whereas others feel that it might be the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc that leads to neuronal injury and loss [Mallucci et al., 2007; Moreno et al., 2013]. PrPSc propagates as oligomers, which might polymerize to form amyloid fibrils [Prusiner 2013]. As we will discuss later, PrP amyloid plaques are sometimes found in brains of patients with PrD, particularly in GSS and stop codon mutations.

There are two major types of PrPSc found in brains of individuals with PrD (particularly in sJCD), termed types 1 and 2 [Puoti et al., 2012]. After brain homogenates are treated with proteinase K (which digests most of PrPC, leaving behind PrPSc, which is generally resistant to proteinase K digestion) and run on a Western blot and stained for PrP, this shows three bands which are the diglycosylated, monoglycosylated and the unglycosylated forms of PrPSc. The unglycosylated bands run at the lowest molecular weight; when the unglycosylated band runs at 21kD, this denotes type 1 PrPSc and at 19kD this denotes type 2 PrPSc [Parchi et al., 1996]. In about two-thirds of cases only one type is found in the brain at pathology, but co-occurrence of types 1 and 2 occurs in about one third of cases [Parchi et al., 2009]. The combination of PrPSc type and PRNP codon 129 polymorphism has been used in the molecular classification of sJCD clinicopathological phenotypes (for excellent reviews, see Puoti et al. 2012 and Brown et al. 2010) [Brown and Mastrianni 2010; Parchi et al., 1999; Puoti et al., 2012].

A few gene risk variants in PRNP have been characterized, and among those, the codon 129 polymorphism (rs1799990) is the most relevant to human PrD, as it influences both disease susceptibility and the phenotypical presentation of the genetic, sporadic and acquired forms of PrD. Codon 129 encodes either methionine or valine, and in the general population, about 55% of persons are homozygous for methionine (MM), 36% are heterozygous (MV) and 9% are homozygous for valine (VV) [1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012]. Homozygosity at codon 129 is a well-established risk factor for sporadic and acquired PrD [Mead et al., 2012; Palmer et al., 1991]. Among European sJCD cases, for example, 70% are 129MM, 13% are 129MV and 16% are 129VV, which shows there is a clear underrepresentation of codon 129 heterozygosity among sJCD cases in comparison to the normal population [Alperovitch et al., 1999].

In gPrD, the polymorphism located in the same allele as the mutation (cis) has a more significant effect on disease presentation, whereas the trans polymorphism usually has less or even no effect [Capellari et al., 2011]. As previously mentioned, in the PRNP D178N mutation, the codon 129 polymorphism in cis determines whether the phenotype is gJCD (D178N-129V) or FFI (D178N-129M) [Goldfarb et al., 1992]. The phenotype associated with other mutations are also clearly influenced by the codon 129 genotype, which is why some authors suggest the mutations should be reported in combination with the codon 129 genotype [Capellari et al., 2011; Goldfarb et al., 1992].

Common PRNP mutations in various national cohorts

Cohorts of gPrD have been described from most parts of the world, mostly in multi-center studies or from national PrD surveillance centers. More than 60 reportedly pathogenic variants have been published in the literature to date (even though most of them were only reported in single or few patients/families, and several might even be benign variants or mutations with low penetrance) [Kovacs et al., 2005; Minikel et al., 2016]. Among those variants, five are responsible for about 85% of gPrD cases in nine major surveillance centers around the world (in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom and US National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC), namely: E200K, V210I, V180I, P102L, and D178N [Minikel et al., 2016]. The E200K, V210I, V180I and D178N-129V mutations are associated with familial JCD and P102L with GSS. As many cases of familial JCD (fJCD) do not actually have a known history of prion disease (either because of misdiagnosis or low penetrance), we prefer the term genetic JCD (gJCD), which will be used hereon in this paper. A few of the mutations have large regional clusters due to a founder effect, such as the E200K mutation clusters among Slovakians and also Libyan (Sephardic) Jews, many of whom now are in Israel, [Hsiao et al., 1991a; Mitrova and Belay 2002] the V180I mutation most commonly found in Japan, and V210I, which is the most common mutation in Italy [Ladogana et al., 2005; Minikel et al., 2016].

The objectives of this paper are to describe the diversity of prion diseases through literature review of genetic PrD, as well as describing our well-characterized cohort of gPrD subjects referred to a single rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) and PrD research center in the USA.

Methods

Patients in UCSF Cohort

Between August 1, 2001 and May 1, 2016, 1922 subjects with (RPD), including suspected PrD, or unaffected persons from families with gPrD have been referred to the University of California, San Francisco Memory and Aging Center (UCSF MAC) RPD clinical research program. After the initial contact made by a health care provider or patient, caregiver, and/or family member, we requested the patients’ medical records for our review, as well as possible signing of informed consents for the data to be included in our ongoing RPD research. Some research subjects were also evaluated through an ongoing study of persons at risk for gPrD (from an affected family but PRNP status unknown), with a PRNP mutation, or non-carriers (from gPrD families). This study includes symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. We also have an internal review board (IRB)-approved protocol allowing use of existing referred patient data for research, except when inclusion of data is explicitly declined by the patient or family. Patients with suspected, known or at risk for PrD were offered a research visit at our center. Visits typically included an extensive evaluation including clinical history, neurological examination, neuropsychological and functional assessment, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), genetic counseling including detailed family histories/trees, social work assessment, PRNP gene testing (blood), and blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection or research. Subjects found to have a PRNP mutation were included in the descriptive analyses in this paper. Subjects were included in the analyses in this paper if referral or initial contact was made before May 1st, 2016.

Demographic and general clinical data (e.g. age at onset of symptoms and first symptoms) were collected from outside medical records. First symptoms were characterized as previously described [Rabinovici et al., 2006]. Patients or asymptomatic individuals who came to UCSF MAC for a research visit were further characterized in detail, including if appropriate, symptoms present during the course of disease, signs on neurological examination, and cognitive and behavioral assessments. Results of ancillary testing (genetic, CSF and neuroimaging) were included if available in medical records or performed at UCSF. Total disease duration was calculated only if the patient was deceased and date of death was informed to our team. For determining the likelihood of a positive family history (FMH), FMH was rated as 0 when there was no positive FMH suspicious for or known PrD; 1 when there was at least one first-degree relative with dementia, encephalopathy or movement disorder; or 2 in patients who were part of families with known PRNP mutations, or had positive history for clinical or path-proven PrDs.

Laboratory testing

Genetic testing for PRNP mutations and polymorphisms were performed by blood test or frozen brain tissue through the U.S. National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC, Case Western Reserve), following previously described methods [Zou et al., 2010].

CSF 14-3-3 analysis by Western Blot was also performed at the NPDPSC. CSF total tau (t-tau; either through Athena Diagnostics, Inc. or the NPDPSC) and neuron specific enolase (NSE; Mayo Medical Laboratories, Rochester, MN) results were included when available. Cut-off levels for t-tau were 1150 pg/mL (performed at NPDPSC) or 1200 pg/mL (performed at Athena Diagnostics) and cut-offs for NSE were 30 or 35 ng/mL (Mayo Medical Laboratories cut-off prior to November 20, 2007 was >35 ng/mL and after was changed to >30 ng/mL) [Forner et al., 2015].

Neuroimaging

Brain MRI scans included for analyses in this study were performed at UCSF or outside centers. Images were available from 1.5 and 3T scanners and usually included T1, T2, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion weighted imaging (DWI ) and attenuation diffusion coefficient (ADC) map sequences. MRI scans were considered positive for PrD if they met the criteria published by Vitali et al [Vitali et al., 2011]. MRIs often were further classified according to cortical or subcortical predominance of DWI abnormalities.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Release 12 (College Station, TX). Chi-square and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used, according to data type. Significance was set at p≤0.05.

Literature review

We performed a literature review in Pubmed for “genetic prion disease” or “PRNP mutation” as search terms, and also performed searches for each mutation individually (e.g. E200K, P102L, etc.). We also used data on gPrDs from a detailed, but now somewhat dated, book chapter on this subject [Kong et al., 2004]. We also searched for publications from PrD surveillance centers, using “surveillance” and “prion” as search terms.

Results

Patients

Among 1922 subjects referred to our center, 1266 were suspected PrD or were unaffected gPrD family members. In this UCSF cohort, we identified 89 gPrD families, representing 22 different PRNP mutations, with gPrD whose family members have had UCSF visits or with whom we have been in contact (Table 1). In this cohort, we had 129 symptomatic, 64 presymptomatic, 73 non-mutation carriers (controls for our research, and 47 whose PRNP status was unknown. Among the 129 symptomatic gPrD patients, we had clinical data (most of which was extensive) on 79 cases. The mutations in whom we have the largest number of families in our cohort are: E200K (n=31 families), P102L mutations (n=11), D178N-129M (FFI; n=9), D178N-129V (n=6), and three each for 5-OPRI (typically GSS per the literature), A117V (GSS), and F198S (GSS). Among symptomatic cases, the most common individual mutations in our cohort with five or more cases were E200K (n=43), P102L (n=20), D178N-129V (n=10), D178N-129M (FFI, n=9), A117V (n=7), H187R (n=6), F198S (n=6), V210I (n=5), and 6-OPRI (n=5). Three mutations in our cohort (K194E, E200G, A224V) are novel [Kim et al., 2013; Watts et al., 2015] (Table 1). The mutations best represented in our cohort are also the most common in the US and most other countries [Kovacs et al., 2011; Minikel et al., 2016; Webb et al., 2008]. Of the symptomatic cohort of 129 gPrD patients, 67 were classified as gJCD, 40 GSS, and 9 FFI, 12 OPRI (many were GSS-like) and one had a nonsense mutation (Q160X). The demographic and clinical characteristics of each group (except the nonsense mutation) are shown in (Table 2).

Table 1.

| UCSF Genetic Prion Disease Cohort# | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Family Mutation | All families | All subjects | Mutation positive subjects* | Symptomatic patients | |||||||

| Referred | Seen | Visits | Referred | Seen | Visits | Referred | Seen | Visits | Referred | Seen at UCSF | ||

| fJCD | E200K | 31 | 22 | 22 | 127 | 63 | 52 | 76 | 40 | 35 | 43 | 12 |

| T188R | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| D178N/129V | 6 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 9^ | 3 | 3 | 10^ | 3 | |

| V180I | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| E200G | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| A224V | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| V210I | 6 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| K194E | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| R148H | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| G54S | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| SUBTOTAL | 52 | 33 | 33 | 182 | 86 | 75 | 109 | 57 | 52 | 67 | 20 | |

| GSS | A117V | 3 | 3 | 3 | 30 | 25 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 6 |

| P102L | 11 | 6 | 5 | 34 | 16 | 15 | 24 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 8 | |

| F198S | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | |

| H187R | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | |

| P105L | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| SUBTOTAL | 19 | 12 | 11 | 83 | 49 | 46 | 51 | 28 | 28 | 40 | 20 | |

| FFI | D178N/129M | 9 | 4 | 4 | 28 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| Octapeptide repeat insertions | 5-OPRI | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 6-OPRI | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |

| 8-OPRI | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 9-OPRI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 365–388dup | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| SUBTOTAL | 8 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 4 | |

| Nonsense Mutation | Q160X | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 22 mutations | 89 | 55 | 54 | 316 | 155 | 138 | 190 | 100 | 93 | 129 | 46 |

For each syndrome, mutations are listed in order of subjects seen and then by mutation codon number. All families include those having any family members who were referred to, seen at or visited UCSF. All subjects include mutation positive subjects (symptomatic and presymptomatic), no-mutation carriers, and subjects at-risk for mutations but not tested for mutations or not knowing the status of mutations.

Mutation positive subjects include symptomatic and presymptomatic cases only. Referred: all subjects; Seen: subjects seen at UCSF through clinic, inpatient, research or any combination of these; Visits: subject had full UCSF research visit

one subject was symptomatic and had a history of fJCD, but did not complete genetic testing or autopsy to confirm diagnosis.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical features of the symptomatic UCSF gPrD cohort, by gPrD classification.

| Classification | n | gJCD$ | n | GSS$ | n | FFI$ | n | OPRI$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic cases referred | 67 | 40 | 9 | 12 | ||||

| Number of families with symptomatic cases | 46 | 19 | 5 | 8 | ||||

| Symptomatic cases evaluated at UCSF | 20 | 20 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Age at onset (years) | 38 | 58±13 (36–84) | 26 | 41±14 (10–66) | 4 | 47±19 (20–64) | 9 | 44±14 (18–70) |

| Onset to UCSF evaluation (months) | 18 | 9.4±7.0 (0.5–25.5) | 16 | 47.0±45.2 (3–168) | 1 | 8 | 5 | 41.6±47.0 (7–120) |

| Sex | 27M:25F | 20M:10F | 4M:4F | 6M:7F | ||||

| Duration of disease (months)^ | 32 | 12.4±15.6 (1–78) | 16 | 56.3±29.7 (27–141) | 4 | 7.7±1.8 (5–9) | 5 | 27.2±25.8 (5–69) |

| First symptom category | ||||||||

| Cognitive | 38 | 53% | 28 | 32% | 3 | 33% | 6 | 83% |

| Cerebellar | 18% | 39% | 0 | 17% | ||||

| Sensory | 16% | 0 | 0 | 17% | ||||

| Behavioral | 10% | 7% | 33% | 17% | ||||

| Constitutional | 10% | 4% | 67% | 0 | ||||

| Visual | 5% | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Motor | 3% | 18% | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Epileptic | 0 | 4% | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Positive family history§ | 39 | 80% [scores 1=13; 2=18] | 18 | 79% [scores 1=4; 2=10] | 4 | 75% [score 2=3] | 5 | 60% [score 1=2; 2=1] |

| CSF 14-3-3* positive | 15 | 40% | 10 | 10% | 2 | 0 | 5 | 40% (2/5) |

| CSF total tau** | 6 | 50% | 4 | 25% | 0 | - | 2 | 0 |

| CSF NSE*** | 7 | 14% | 8 | 38% | 0 | - | 3 | 33% |

| EEG – PSWC positivity | 23 | 22% | 13 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 25% |

| MRI DWI positivity# | 28 | 89% | 14 | 7% | 3 | 33% | 6 | 17% |

Data is displayed as mean ± standard deviation (range). Ranges in parentheses. n = Number of patients from whom data was available.

gJCD includes E200K, D178N-129V, V210, V180I, A224V, E200G, E148H, T188R, K194E. GSS includes P102L, A117V, D198S, H187R, P105L and 365–388dup. FFI includes D178N-129M. OPRI include 5-OPRI, 6-OPRI, 8-OPRI and 9-OPRI. “n” refers to the number of cases for a gPrD classification for whom relevant data is available.

Duration of disease in deceased patients only

Family history was scored as (0) Negative; (1) questionable PrD (dementia NOS, encephalopathy, movement disorder, etc…); (2) positive for PrD (confirmed by molecular testing, neuropathological assessment, and/or clinical diagnosis). Positive family history means score 1 or 2.

Inconclusive CSF 14-3-3 was considered negative, based on a previous study [Forner et al., 2015].

Positive CSF total tau >1200pg/ml.

Positive CSF NSE >35ng/ml before November 2007; > 30 ng/ml after November 2007.

According to published UCSF criteria [Vitali et al., 2011].

Abbreviations: CSF= cerebrospinal fluid; DWI=diffusion weighted imaging EEG= electroencephalogram; FFI= familial fatal insomnia; gJCD= genetic Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease; GSS= Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker; MRI= magnetic resonance imaging; NSE= neuron specific enolase; OPRI= octapeptide repeat insertions; PSWC= periodic sharp wave complexes.

Division into Fast vs. Slow presentations

Although it is often very helpful to classify each of the PRNP mutations (missense, nonsense, or octapeptide repeat insertions/deletions) based on clinical and neuropathological characteristics into the historical classificaitons of genetic JCD, GSS or FFI, this division does have some limitations, as nonsense mutations and many octapeptide repeat insertions/deletions do not fit neatly into one of these three clinicopathologial categories. Clinically, we have found it helpful also to dichotomize gPrDs according to the rate of clinical course (decline rate and total disease duration) as Fast vs. Slow types. As we typically define RPD as dementia with rapid decline and less than 3 years of disease duration [Geschwind 2016], we applied this concept to classifying gPrDs and divided gPrDs into Fast and Slow types; Fast type with rapid decline and total disease duration usually less than three years and Slow type with more gradual decline and total disease duration usually greater than three years. This classfication captures OPRD, FFI and almost all gJCD and a few OPRIs (particularly those with <4 repeats) as Fast, and all nonsense mutations, almost all GSS and most OPRIs (some with 5–7 repeats and particularly ≥ 8 repeats) as Slow. Some of the OPRIs and GSS, however, even within the same repeat size can present as Fast or Slow, even within the same family. For OPRIs, this in part might be because there can be variations in the pattern of repeats between the same size of OPRI [Schmitz et al., 2016]. In this review, we present the features of each mutation, including their historical classifcation. We start with Fast types and then present the Slow types and then discuss OPRIs/OPRD seperately as they can present as Fast or Slow. Lastly we discuss the very unusual and rare nonsense mutations, which are Slow types.

Genetic Prion Diseases usually with faster disease progression

Genetic Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease (gJCD)

Specific PRNP mutations have historically been associated with gJCD when the clinical presentation resembled that of sJCD, and spongiform encephalopathy (including spongiform changes, astrocytic gliosis and neuronal loss) and/or PrPSc immunostaining was found in the brains of mutation-carrying patients [Budka et al., 1995]. At least 21 missense variants in PRNP have been reported as causing gJCD in the literature (including P105T, G114V, R148H, D178N (with codon 129 cis V), V180I, T183A, T188A, T188K, T188R, T193I, E196A, E196K, E200K, E200G, V203I, R208H, V210I, E211Q, I215V, M232R, and P238S), but the pathogenicity of some of these variants, especially are questioned by some (see below) [Minikel et al., 2016]. Nine missense mutations were found in the UCSF cohort, namely E200K (n=43 symptomatic cases), D178N-129V (n=10), V210I (n=5), V180I (n=2), A224V (n=1), E200G (n=1), R148H (n=1), T188R (n=2), and K194E (n=1).

The penetrance of PRNP mutations is variable, and will be discussed with each mutation. Importantly, a positive family history of PrD is found in only 50-75% of patients with gJCD, but this percentage varies greatly depending on the mutation [Kovacs et al., 2005]. In many gPrD cases with a reportedly negative family history of PrD, further inspection will usually uncover a family history of dementia or neuropsychiatric illness, however, that was likely PrD, but had likely been misdiagnosed [Goldman et al., 2004].

The mean age of symptom onset in gJCD is about 55 years, and although onset most frequently occur between the fifth and seventh decades of life, there is a great variability in age at onset ranging from the second to ninth decades of life [Kovacs et al., 2002]. The mean duration of disease is about 15 months, and even though 90% of patients die in less than 24 months after disease onset, total duration of disease of more than 8 years has been reported [Kovacs et al., 2002]. Compared to sJCD, the age at onset of gJCD is often lower, and disease duration, longer [Kovacs et al., 2002].

Dementia is very common among patients with gJCD, and has been reported in 95–98% of patients [Kovacs et al., 2002; Meiner et al., 1997]. Cerebellar symptoms are found in approximately 70%, myoclonus in 60–70% [Kovacs et al., 2002; Meiner et al., 1997], extrapyramidal signs in about 50%, and psychiatric symptoms in slightly more than 25% of cases [Kovacs et al., 2002].

Regarding ancillary testing, the accuracies of CSF markers, EEG and brain MRI are overall lower than in sJCD [Kovacs et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2002]. In CSF, 14-3-3 positivity has been reported in 85–100% of cases depending greatly on the mutation and the study [Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016], and elevated total tau levels (> 1200 pg/ml), in 75–100% of cases [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Higuma et al., 2013; Krasnianski et al., 2016]. PSWCs in EEG are observed in 11–93% (average ~60–70%) of cases, also depending greatly on the mutation and the study [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997]. The sensitivity of brain MRI varies greatly depending on MRI sequences used, with much lower sensitivity for T2-weighted sequences and very high for diffusion sequences (DWI and ADC). On brain MRIs, basal ganglia and/or cortical hyperintensities in FLAIR or DWI have been found in 25–80% of cases, but there is significant variation across mutations and study [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016]. In the UCSF gJCD cohort, we found much lower sensitivity for CSF 14-3-3, total tau and NSE and EEG than the literature, but high DWI sensitivity (89%) (Table 2).

There is sufficient evidence proving that variants such as the E200K and D178N mutation are pathogenic. Some variants, however, are frequently reported as mutations despite there being no cases with any positive or even suggestive family history of PrD and/or beingfound in population data sets, such as the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), at a frequency higher than expected if they were highly penetrant, Mendelian disease-causing variants. Therefore, some these variants might be considered low-penetrance mutations or risk factors for PrD, and some others might even be benign variants with no influence on PrD risk [Minikel et al., 2016]. For example, the V210I mutation, the most frequent mutation reported in Italy, has penetrance estimated to be about 10%. Two frequently reported mutations in Japan, M232R and V180I, have even lower estimates of penetrance, of 0.1% and 1%, respectively. Other variants were reported only in a few patients (Table 3) and based on the clinical evidence available to date, some of them might be low-penetrance or benign variants, such as R148H, T188R, V203I, R208H [Minikel et al., 2016]. Other variants are too rare in both patients and in control population data sets for a conclusion to be drawn on their pathogenicity.

Table 3.

Missense mutations in PRNP in literature & UCSF cohort*

| PRNP Mutation |

Codon 129 polymorphism |

# of cases in literature or UCSF cohort # |

Clinical phenotypes |

Age at onset (range)^ Y |

Disease Duration (M or Y) |

Pos FHx## |

CSF marker Sensitivity |

EEG PSWC |

MRI c/w JCD§ |

Neuropath | Neuropathl Pheno- type |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3 | Total tau^^ | ||||||||||||

| P84S | MV | 1 |

|

(60) | (14) M | 0% (0/1) | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | Multic PrP-Plqs w/o NFT No V |

GSS | [Jones et al., 2014] | |

| S97N | Cis M | 1 |

|

(72) | N/A | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | [Zheng et al., 2008] | |

| P102L | MM/MV (most cis M) | ~221 |

|

(27–66) | (7–132) M | 84–100% | (15–20% ) | 20% | 0–35% | 25–30% | Multic PrP-Plqs | GSS | [Webb et al., 2008; Higuma et al., 2013; Krasnianski et al., 2015] |

| P102L UCSF | Cis M | 13 | 44±12 (24–57) | 44±13 M (28–60) | FHx Score 0 (n=1) 1 (n=2) 2 (n=6) |

0 % (0/3) | 0% | 0% (0/3) | 33.3% (1/3) | ||||

| P105L | MV | 13 |

|

Mean 44±10 (2nd to 7th decades) | Mean 111±82 M | 37% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | PrP-Pl, diff PrP (deep CLs) | GSS | [Higuma et al., 2013] |

| P105L UCSF | N/A | 1 | (10) | N/A | FHx Score 0 (n=1) |

N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | ||||

| P105T | Cis M | 13 |

|

(13–41) | (2–5) Y | 100% (2/2) | 0% | N/A | 0% (0/3) | 25% (1/4) | V, PrP-S (all CLs) Unicentric PrP-Plqs (deep CLs) | JCD | [Rogaeva et al., 2006; Polymenidou et al., 2011] |

| P105S | MV (Cis V) | 1 |

|

(30) | (10)Y | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | Multic PrP-Plqs (HP), punctate aggregates (Cb), V (Pu) | Atypic GSS | [Tunnell et al., 2008] |

| G114V | (MM/MV) | 1 |

|

(18–75) | (1–4)Y | 75% (3 in 4 probands)§§ | 0% | 0% (0/8) | 42.9% (3/7) predom BG | Mod V, G, NL. PrP-S, Type 1 PrPSc (predom monoglycos) | JCD | [Rodriguez et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Beck et al., 2010] | |

| A117V | Cis V | 33 |

|

(20–64) | (1–11 Y) | 100% (4/4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/2) | Ab PrP-Plqs, F V, NL, G | GSS | [Hsiao et al., 1991; Mastrianni et al., 1995; Kong et al., 2004] |

| A117V UCSF | Cis V | 6 | 34±14 (14–49) | 46±21 M (27–78) | FHx Score 0 (n=1) 2 (n=2) |

0 % | 0 % | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/5) | ||||

| G131V | MM/MV (cis M) | 3 |

|

(36–42) | (9–16) Y | 50% (1/2) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | PrP-Plqs, NFT (AH, ERC), No V | GSS | [Panegyres et al., 2001; Jansen et al., 2012] |

| S132I | MM | 2 |

|

(62) | (18) M | 100% (1/1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | diff unicentric & multic PrP-PLs (neocortex, BG, Cb) Min V |

GSS | [Hilton et al., 2009] |

| A133V | MM | 2 |

|

(62) | (4) M | 0% (0/1) | 0% | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | diff V, G, NL multic PrP-Plqs in the (Mol), PrP-S (Th) | Atypic GSS | [Rowe et al., 2007] | |

| R148H | (MV/MM) | 3 |

|

(62–82) | (6–18) M | 0% (0 in 2)§§ | 50% (1/2) | 100% (1/1) | 50% (1/2) | 100% (1/1) predom BG | 129MM – Similar to sJCDMM1. V, G, NL (deeper lCLs). PrP-S PrPSc Type 1 129MV - Similar to sJCDMV2 V predom in CLs V & VI, Kuru plaques in Cb & WM, PrP-S PrPSc type 2 (predom monoglycos) | JCD | [Krebs et al., 2005; Pastore et al., 2005] |

| R148H UCSF | MM | 1 | (53) | (2) M | FHx Score 0 (n=1) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | 100% (1/1) | ||||

| D167G | MM | 1 |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | sJCD PrP type 1 | JCD | [Bishop et al., 2009] |

| D167N | MM | 1 |

|

(33) | (2) Y | 0% (0/1)§§ | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | [Beck et al., 2010] |

| V176G | VV | 1 |

|

(61) | (7) M | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | Multic PrP-Plqs w/prominent tau | GSS | [Simpson et al., 2013] |

| D178N-129V | MV/V V (Cis V) | 209** |

|

Mean 46 (26–56) | Mean 23 M (7–60) | 100% (12/12) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Similar to sJCD VV1 | JCD | [Brown et al., 1992; Goldfarb et al., 1992; Kong et al., 2004] |

| D178N-129V UCSF | Cis V | 8 | 45±6 (37–52) | (18–21) M | FHx Score 2 (n=4) |

50% (1/2) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/2) | 100% (2/2) | ||||

| V180I | Cis M | 225 |

|

Mean 77 | Mean 25 M | 0.7–6% | 70%; | 78.5% | 11% | 99% | V PrP-S | JCD | [Kong et al., 2004;Higuma et al., 2013] |

| V180I UCSF | Cis M | 2 | (84) | (21) M | FHx Score 1 (n=1) 2 (n=1) |

0% (0/1 | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | |||||

| T183A | Cis M | 3 |

|

45±4 (42–49) | 4±2 Y (2–9) | 100% (2/2) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/7) | 0% (0/2) | V & NL (CLs IV, V, VI), PrP (Cb, Pu) Small Plq-like PrP, Predom monoglycos PrPSC | JCD | [Nitrini et al., 1997; Grasbon-Frodl et al., 2004] |

| H187R | MM/MV/VV | 7 |

|

(20–53) | (3–19) Y | 100% (4/4) | 0% (0/2) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/4) | G multic-PrP-Plqs in some cases. Curly PrP-G | GSS | [Cervenakova et al., 1999; Butefisch et al., 2000;Hall et al., 2005; Colucci et al., 2006] | |

| H187R UCSF | Cis M | 4 | (30–41) | (12–13) Y | FHx Score 2 (n=1) |

0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | ||||

| T188R | MV/VVV (Cis V) | 12 |

|

(55–66) | (14–16) M | 0% (0/1)§§ | 50% (1/2 | 100% (1/1) | 50% (1/2) | 50% (1/2) | V, NL, A PrP-S & plaque-like PrP, Type 1 PrPSc | JCD | [Tartaglia et al., 2010; Roeber et al., 2008] |

| T188K | MM/MV (Cis M) | 3 |

|

Median 58 (39–76) | (2–13) M | 8–37%§§ | 69% | 12% | 69% | SE PrP-S | JCD | [Roeber et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2015] | |

| T188A | MM | 1 |

|

(82) | (4) M | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | Sev G, V, Mod NL (predom in OLs) PrP-Neg | JCD | [Collins et al., 2000] |

| T193I | MM |

|

(70) | (10) M | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | [Kotta et al., 2006] | |

| E196K | N/A | 13 |

|

(64–69) | (10–13) M | 100% (1/1) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | [Peoc’h et al., 2000] |

| F198S | MV/VV | 5 |

|

(40–71) Y | Mean 5 Y (2–12) | 100% (3/3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | Uni- & multic PrP-Plqs | GSS | [Farlow et al., 1989; Dlouhy et al., 1992; Ghetti et al., 1995; Kong et al., 2004] |

| F198S UCSF | Cis V | 5 | 55±8 (46–66) | 67±23 M (34–84) | FHx Score 1 (n=2) 2 (n=1) |

33.3% | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/4) | 0% (0/3) | ||||

| F198V | MM | 1 |

|

(56) | (4) Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | [Zheng et al., 2008] |

| E200K | MM/MV/VV | 571 |

|

Mean 60 (33–84) | (1–18) M | 50% | 85–100% | (80–100%) | 42–85% | 50–88% | Usually sJCD MM1 PrPSc types 1 & 2 | JCD | [Spudich et al., 1995; Meiner et al., 1997; Kovacs et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2011; Krasnianski et al., 2015] |

| E200K UCSF | Cis M (n=16) & Cis V (n=1) | 34 | 60±13 (36–84) | 11 ±17 (1–78) | FHx Score 0 (n=2) 1 (n=10) 2 (n=12) |

57.1 % (4/7) | 37.5% (3/8) | 88.9% (16/18) | |||||

| E200G | MV (Cis V) | 1 |

|

(57) | (30) M | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | 100% (1/1) | SE w/type 2 PrPSc | JCD | [Kim et al., 2013] |

| D202G | MV (cis V) | 1 |

|

(55) | (16) Y | 100% (1/1) | 100% (1/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | [Heinemann et al., 2008] |

| D202N | VV | 1 |

|

(73) | (6) Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | PrP-Plqs, NFT | GSS | [Piccardo et al., 1998] |

| V203I | N/A | 17 |

|

(69) | (1) M | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | 100% (1/1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | [Peoc’h, 2000 #12035] |

| R208H | MM/VV | 15 |

|

(58–63) | (3–16) M | 20% (1/5) | 50% (4/8) | 57.1% (4/7) | 25% (2/8) | SE, PrP-S (perineuronal perivacuolar) Type 1 PrP | JCD | [Roeber et al., 2005; Capellari et al., 2005; Matej et al., 2012 Vita et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2015] | |

| V210I | Cis M | 247 |

|

Mean 59 (39–82) | Median 5 (2–20) M | 12–31% | 90–100% | 100% | 44–80% | 15–33% | Similar to sJCD MM1 | JCD | [Kovacs et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2004; Breithaupt et al., 2013 Krasnianski et al., 2015] |

| V210I UCSF | Cis M | 3 | 57±15 (47–74) | (1) M | FHx Score 0 (n=2) 2 (n=1) |

100% (1/1) | 33.3% (1/3) | 100% (2/2) | |||||

| E211Q | MM | 11 |

|

(42–81) | (6–32) M | 100% (2/2) | N/A | N/A | 100% (4/4) | N/A | V, G Mi PrP-S types 1 & 2 PrPSc | JCD | [Peoc’h et al., 2000; Ladogana et al., 2001; Peoc’h K et al. 2012] |

| E211D | VV | 1 |

|

(53–68) | (3–13) Y | 50% (1/2) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/2) | 0% (0/2) | Multic PrP-Plqs, Dystrophic neurites & NFT | GSS | [Peoc’h et al., 2000; Peoc’h et al., 2012] |

| Q212P | MM | 2 |

|

(60) | (8) Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Mod PrP Mi, PrP-Plqs | GSS | [Piccardo et al., 1998] |

| I215V | MM | 1 |

|

(55–76) | (12–15) M | 0% (0/2) | (1/3) | 100% (2/2) | 50% (1/2) | NL, G, V, PrP-Neg | JCD | ||

| Q217R | VV/MV (Cis V) | 3 |

|

(45–66) | (5–13) Y | 100% (3/3) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/1) | 0% (0/1) | Uni- & multic PrP-Plqs, NFT (neocortex) | GSS | [Hsiao et al., 1992; Woulfe et al., 2005; Piccardo et al., 1998; Munoz-Nieto et al., 2013] |

| Y218N | VV | 1 |

|

(54–61) | (6) Y | 100% (1/1) | N/A | N/A | 0% (0/2) | 0% (0/2) | Uni & multic PrP-Plqs, NFT w/hyperP tau. | GSS | [Alzualde et al., 2010] |

| A224V | VV (Cis V) | 1 |

|

(48) | (32) M | 0% (0/1)§§ | 100% (1/1) | N/A | 100% (1/1) | Diff V w/PrPSc type 1 | JCD | [Watts et al., 2015] | |

| M232 R | MM | 63 |

|

Mean 64 (15–81) | Mean 8 (0–32) M | ~0% | 55–75% | 55–93% | 20–100% | 85% | sJCD MM1 | JCD | [Shiga et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2008; Nozaki et al., 2010; Higuma et al., 2013] |

| M232 T | MV |

|

N/A | (6) Y | 0% (0/1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Multic PrP-Plqs | GSS | [Bratosiewicz et al., 2000] | |

| P238S | N/A |

|

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [Windl et al., 1999] | |

If UCSF cohort differs from the literature, this information is provided in the table.

Including D178N-129V & D178N-129M.

By nine PrD surveillance centers, according to Minikel et al., 2016.

Positive family history of dementia w/similar clinical features (as of the proband) or PrD. For UCSF family history FHx (family history) Score scale: 0 when there was no positive FMH suspicious for or known PrD; 1 when there was at least one first-degree relative w/dementia, encephalopathy or movement disorder; or 2 in patients who were part of families w/known PRNP mutations, or had positive history for clinical or path-proven PrDs.

According to most commonly used European 2009 and UCSF 2011 criteria [Zerr et al., 2009; Vitali et al., 2011].

there is evidence of incomplete penetrance, as asymptomatic older carriers also were identified.

Data on age at onset & duration of disease are shown as mean±SD (range), unless otherwise indicated.

positive if > total tau 1200 pg/mL

Abbreviations: Ab = abundant; AD = Alzheimer-type dementia; AH = Ammon horn; atypic = atypical; Atx = ataxia; BG = basal ganglia; bvFTD = behavioral variant Frontotemporal Dementia; c/w = consistent with; Cb = cerebellum; CBS = corticobasal syndrome; CLs = cortical layers; Cog = cognitive; D = dementia; diff = diffuse; dx = diagnosis; ERC = entorhinal cortex; EP = extrapyramidal; FHx = family history; F = focal; freq = frequent; G = gliosis ; GTC = generalized tonic clonic seizures; HP = hippocampus; HyperP = hyperphosphorylated; LE = lower extremities; LMN = lower motor neuron; M = months; Mi = mild; Min = minimal; Mod = moderate; Mol = molecular layer of the cerebellum; monoglycos = monoglycosylated; multic = multicentric; N/A = not available; Neuropath = Neuropathology; NFT = neurofibrillary tangles; NL = neuronal loss; OLs = occipital lobes; Park = parkinsonism; Pos = positive, prog = progression; predom = predominant; PrP-G = granular PrP deposits; PrP-Neg = negative PrP staining; PrP-Plqs = PrP-amyloid plaques; PrP-S = synaptic PrP deposits; PSP=progressive supranuclear palsy; PSWC = periodic sharp wave complexes; Pu = putamen; Pyram = pyramidal; SE = spongiform (vacuolated) encephalopathy; Sev = severe; SYN = syndrome; Th = thalamus; WM = white matter.; Psych = psychiatric; Sxs = symptoms; V = vacuolation; w/ = with; w/o = without; Y = years

We had 67 symptomatic patients with gJCD (from 52 families) who were referred to the UCSF MAC, and 20 of them were evaluated at our center. The most frequent mutations were E200K (n=43), D178N-129V (n=10), V210I (n=5), and V180I (n=2), as shown in Table 1. We have published our single cases of A224V [Watts et al., 2015], E200G [Kim et al., 2013] and T188R [Tartaglia et al., 2010] mutations. The K194E mutation is a novel mutation that will be reported in a separate manuscript, but is briefly described below. Now, we will present the clinical features of the most common gJCD-related mutations (E200K, D178N-129V, V210I, V180I, and M232R), along with the mutations only reported in the UCSF cohort (E194E, E200G, A224V). The features of the other mutations associated with this phenotype are summarized in Table 3.

E200K

The E200K mutation is the most common mutation worldwide and has been reported in all five continents [Kovacs et al., 2005; Lee et al., 1999; Minikel et al., 2016]. It also was the most common among patients with gJCD (and gPrD) in the UCSF cohort. There are at least four ancestral origins of clusters of patients with this mutation, including the two large ones among Sephardic Jews (and their ancestors) and a Slovakian cohort. There also are two independent cohorts from Germany, Sicily, Austria as well as from Japan [Lee et al., 1999; Meiner et al., 1997; Mitrova and Belay 2002]. The vast majority of reported cases with the E200K mutation have cis codon 129 methionine ( in the same allele as the mutation; E200K-129M), which was also seen in the UCSF cohort (16/17 cases; one case was cis codon 129V).

The penetrance of the mutation is high, but appears to vary by geographic origin. Among Sephardic E200K carriers, penetrance is 70% at age 70 years and close to 100% at age 85 years [Spudich et al., 1995], but even so, approximately 50% of patients have negative family history for PrD [Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Spudich et al., 1995]. In many cases, the family history is kept hidden or there have been misdiagnoses. In Slovakia, penetrance has been reported to be much lower, however, approximately 60% [Mitrova and Belay 2002]. A few reports suggested that anticipation occurred in this mutation [Pocchiari et al., 2013; Rosenmann et al., 1999], even though there was a lack of biological explanation for such phenomenon, but more recently, a large study concluded that the anticipation seen in earlier studies was most likely a false signal due to ascertainment bias [Minikel et al., 2014].

The clinical presentation of gJCD due to E200K mutation is overall similar to that of sJCD [Kovacs et al., 2005; Meiner et al., 1997]. The mean age at onset of symptoms is approximately 60 years of age, but there is a wide range reported in the literature (33–84 years) [Begue et al., 2011; Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2011; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997; Mitrova and Belay 2002]. The median duration of disease is about 5–10 months (range 1–18)[Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2011; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Mitrova and Belay 2002; Shi et al., 2015]. The range of age of onset in the UCSF cohort (36–84 years) was within the range published in the literature, but the duration of disease was longer in some of the patients, as four patients lived longer than 18 months and one outlier had a total disease duration of 78 months (Table 3).

In the literature on E200K of Sephardic origin, onset of symptoms is reported to usually occur gradually over a few weeks to months, but in about 10% of patients, onset is more acute. Cognitive decline is the most common presentation, and is the first symptom in about 50% of patients from Sephardic and European cohorts [Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997]. Cerebellar ataxia is the presenting manifestation in 30%, sensory symptoms in 15%, and constitutional/vegetative symptoms (such as hyperthermia, loss of weight, hyperhidrosis), in 5% of patients [Krasnianski et al., 2016]. In the UCSF cohort, 44% of patients presented with cognitive decline, 20% with cerebellar or sensory symptoms, and 16% with constitutional symptoms (such as weight loss or complaints of tiredness).

During the disease course, 95–100% develop dementia, 80–100% develop cerebellar ataxia, and 70–85% develop myoclonus [Kovacs et al., 2011; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997]. Extrapyramidal signs are found in 40–65% of patients, and pyramidal signs, in 60–70%. Parkinsonism occurs in about 15% of patients, and chorea/dystonia in 35% [Kovacs et al., 2011]. Psychiatric symptoms such as hallucinations, depression, delusions, and aggressiveness are also common during the disease course [Krasnianski et al., 2016].

Despite the similarities between gJCD due to E200K and sJCD, there are also differences. Seizures are more common than in sJCD, occurring in as many as 20–35% of patients with E200K [Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997]. Peripheral neuropathy and supranuclear gaze palsy – features that are uncommon in sJCD - have been reported in some E200K cases [Bertoni et al., 1992; Kovacs et al., 2011; Meiner et al., 1997; Neufeld et al., 1992]. Headaches are endorsed by 20–30% of patients with this mutation [Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997], which is probably higher than for sJCD. Insomnia is reported in about 15% of cases, and insomnia with thalamic degeneration was reported in one case [Kovacs et al., 2011; Meiner et al., 1997].

Whether or not the PRNP codon 129 polymorphism influences the presentation of gJCD due to E200K mutation is somewhat controversial. Our recent paper examining E200K from four large international cohorts found that the codon 129 polymorphism affected disease duration (shorter in 129 MM (cis M) than in 129 MV (cis M) and shorter in 129M haplotype than in 129V haplotype), but not age of onset or death [Minikel et al., 2014]. Most patients reported in the literature have E200K cis 129M, which typically presents similarly to sJCD MM1 [Capellari et al., 2011]. In our UCSF cohort, only one patient had the rare E200K-129V(V) mutation. She developed symptoms at an early age, 36, but had a typically rapid course, dying six months later. Her brain MRI had DWI hyperintensities in the basal ganglia (predominantly) and cortex, and was considered consistent with JCD. The EEG did not show PSWCs, but CSF protein 14-3-3 was positive. In the literature, the mean age at onset of cases with E200K-129V mutation is 55±11 years (range 37–67), and mean disease duration is of 9±4 months (range 2–17) [Kim et al., 2013]. Patients with the E200K-129V mutation tend to have a slight longer disease duration than those with E200K-129M [Kim et al., 2013].

CSF protein 14-3-3 is positive in 85–100% of cases (only 57% within the UCSF cohort, however), whereas CSF tau is positive (>1200 or 1300, depending on the study) in 80–100% [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2015]. CSF real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QUIC) assay positivity was reported as 73–84% [Higuma et al., 2013; Sano et al., 2013]. PSWCs in EEG have been reported in 42–85% of cases with the E200K mutation (37% within the UCSF cohort) [Begue et al., 2011; Breithaupt et al., 2013; Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Kovacs et al., 2011; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Meiner et al., 1997; Shi et al., 2015].

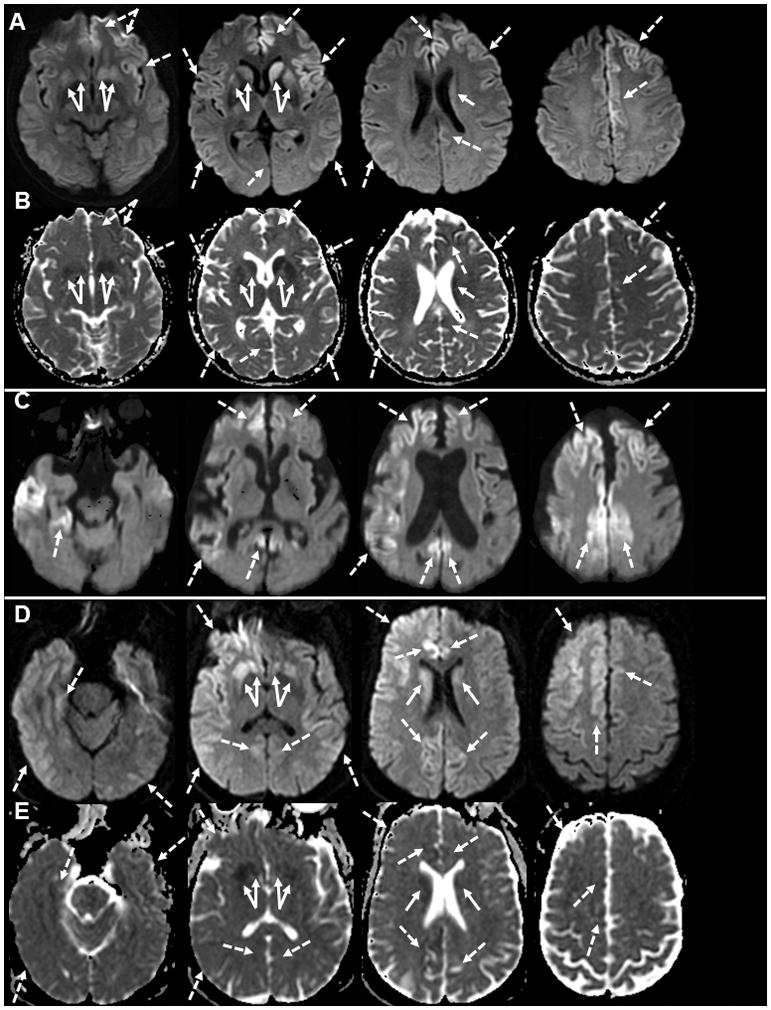

Deep nuclei hyperintensities on DWI or FLAIR MRI are reported in 50–77% of patients with this mutation [Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2015]. If cortical hyperintensities are also considered, the MRI positivity increases to 84–88% [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Higuma et al., 2013] (and was 88% in the UCSF cohort). Most cases (13/18) we had both cortical ribboning and deep nuclei restricted diffusion (bright on DWI, dark on ADC map) (Figure 2A and 2B), whereas the remaining usually had predominantly deep nuclei abnormalities.

Figure 2. Brain MRIs in Fast forms of gPrD.

A. DWI MRI of a gJCD 47 year-old E200K patient 3 months after onset shows diffuse cortical hyperintensity (cortical ribboning; dashed arrows) of the bilateral frontal and insula (left > right) and temporo-parietal cortices. There was also DWI hyperintensity in the bilateral striata (left > right, solid arrows). B. The ADC map of the same gJCD E200K case showed hypointensity in most of the regions that were hyperintense on DWI, confirming reduced diffusion, consistent with prion disease. C. DWI MRI of an 85 year old V180I case 11 months after onset shows diffuse cortical atrophy and cortical hyperintensity (cortical ribboning; dashed arrows) of the bilateral frontal and cingulate (right > left) and the right temporal and parietal lobes. There was no clear abnormality in the deep nuclei. D. DWI in a 49 year old gJCD A224V case 11 months after the onset shows diffuse cortical ribboning (dashed arrows) greater on the right than the left and hyperinensity in the bilateral deep nuclei (solid arrows) also greater in the right. E. The ADC map of the same gJCD A224V case showed hypointensity in most of the regions that were bright on DWI, confirming restricted diffusion, consisent with JCD/prion disease. Orientation is radiological (left brain is right side of figure).

The neuropathological findings in E200K include those typical of spongiform encephalopathies, namely vacuolation (spongiform changes), astrocytic gliosis and neuronal loss, which are more severe in the neocortex, basal ganglia and thalami, and are overall similar to those found in sJCD MM1 [Higuma et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2011]. The majority of cases with E200K-129M have PrPSc type 1, but co-occurrence of PrPSc types 1 and 2 has been reported. In the few cases with E200K-129V reported in the literature, PrPSc type 2 was found [Kim et al., 2013; Puoti et al., 2000]. The pattern of PrPSc deposition is predominantly synaptic, which is seen in all cases with the E200K mutation, but other types of deposits, such as perineuronal and intraneuronal, can be seen in some cases [Kovacs et al., 2011]. Plaque-like structures are more frequent among those heterozygous at codon 129 (MV) than those homozygous (MM) [Kovacs et al., 2011; Mitrova and Belay 2002]. Regarding PrPSc glycosylation, there seems to be an increase in the diglycosylated forms and decrease of unglycosylated PrP, in comparison to sJCD [Kovacs et al., 2011].

D178N-129V

The D178N mutation with valine at the cis codon 129 is typically associated with the JCD phenotype, whereas (as previously mentioned) methionine at cis codon 129 is associated with the FFI phenotype [Goldfarb et al., 1992]. The But as mentioned in the Introduciton, there are exceptions to this pattern, as D178N-129MM might present clinically and neuropathologically as JCD and even within families, both phenotypes (FFI and JCD) might appear [Zarranz et al., 2005; Zerr et al., 1998].

The mean age at onset is 46 years, and onset ranges from the second to the eight decades [Brown et al., 1992; Goldfarb et al., 1992]. The duration of disease is on average longer than sJCD, with a mean of 23 months (range 7–60 months) [Brown et al., 1992; Goldfarb et al., 1992]. The age at onset and disease duration observed among UCSF cases are similar to those previoulsy reported (Table 3). The codon 129VV genotype appears to be associated with earlier onset and shorter disease duration, in comparison to the 129MV genotype [Goldfarb et al., 1992].

Cognitive decline (particularly memory) is the initial symptom in the majority (95%) of patients, and dementia occurs in virtually all patients, a pattern that was also observed in the UCSF cohort [Brown et al., 1992]. Behavioral changes are present in 30% of patients at disease onset, and cerebellar symptoms, in 21% [Brown et al., 1992]. During the disease course, 86% of patients develop cerebellar symptoms, 67% develop extrapyramidal symptoms and about half develop pyramidal symptoms and signs [Brown et al., 1992]. Myoclonus has been reported in 74% of patients, and seizures in 12% [Brown et al., 1992].

Periodic activity on EEG is infrequent in patients with this mutation [Brown et al., 1992; Nozaki et al., 2010]. We are not aware of cohort data on MRI and CSF findings in these cases. Among the UCSF cases, none of the EEGs showed PSWCs, CSF 14-3-3 was positive in 50% of samples, and total tau was not elevated in the available sample. MRI showed neocortical and subcortical hyperintensities consistent with JCD in 100% of cases (2/2).

The neuropathological findings associated with the D178N-129V mutation are similar to those reported in sJCD VV1 [Gambetti et al., 2003b]. Spongiosis and neuronal loss are more severe in the neocortex, whereas the talamus is only mildly affected and cerebellum is spared of those changes [Gambetti et al., 2003b]. Immunostaining for PrPSc reveal synaptic-type deposits that are weakly stained [Gambetti et al., 2003b]. PrPSc type 1 with an underrepresentation of the unglycosilated form is typically observed in this mutation [Gambetti et al., 2003b].

Low penetrance mutations

For the next three mutations, V180I, V210I and M232R, their role in pathogenicity has been controversial as they often lack a positive family history and they have a higher than expected rate in the general population. As noted above, these three mutations are likely low penetrance mutations [Minikel et al., 2016].

V180I

The V180I mutation, the most commonly identified mutation in Japan [Minikel et al., 2016; Nozaki et al., 2010]. That most cases have no positive family history and the rate in the general population is about 6% suggests this mutation is of very low penetrance, probably approximately 1% [Minikel et al., 2016]. For V180I in Japan, many cases began in late age and progressed relatively slowly; mean age at onset was 76.5 years, rather late onset, and mean duration of disease was 25 months. [Higuma et al., 2013; Qina et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2010]. In the Japanese literature, main clinical features were dementia (99%), extrapyramidal (59%), psychiatric disorder (54%), pyramidal (50%), akinetic mutism (49%), myoclonus (45%) and cerebellar signs (36%). Positive family history was low at 0.7–6%. MRI was positive in 99%; cortical ribboning in 75% and basal ganglia hyperintensity in 22%, and PSWCs on EEG was noted in 11%. CSF 14-3-3 was positive in 70%, total tau in 78.5% (cuf-off > 1260 pg/mL), and PrPSc by RT-QuIC in 39% [Higuma et al., 2013]. Neuropathology revealed vacuolation in cortex but low PrPSc immunopositivity of synaptic type [Higuma et al., 2013].

We evaluated one symptomatic (a rare Caucasian) patient with V180I-129MV (cis M) mutation at UCSF. This patient showed similar clinical features to those from the Asian literature; our case manifested with unsteady gait and memory problems at age 84 years and progressed slowly (relative to classic sJCD), dying 21 months after onset. This patient did not have any family history for prion disease or similar disorder, consistent with the literature suggesting very low penetrance [Minikel et al., 2016]. DWI MRI showed diffuse cortical atrophy and cortical ribboning without deep nuclei hyperintensity at 11 months after the onset (Figure 2C), a pattern consistent with the literature on this disorder. Other biomarkers were unremarkable; background slowing on EEG, inconclusive CSF 14-3-3 and total tau and NSE level mildly elevated at 28.5 ng/mL (intermediate; >30 ng/mL consistent with sJCD). Autopsy demonstrated delicate vacuolization of gray matter of the neocortex, caudate nucleus, putamen, thalamus, and cerebellum but sparing of the brain stem and hippocampus with PrPSc deposits in a finely granular pattern, diagnostic for JCD.

V210I

Similarly to V180I and the M232R mutations, theV210I mutation likely is not fully Mendelian. The frequency of this mutation in the general population is about 2%, too high for a fully penetrant, dominant prion disease–causing variant, but far lower than the corresponding allele frequency in prion disease cases, suggesting that this mutation is either a risk factor or of low penetrance. This mutation is estimated to have about 10% penetrance [Minikel et al., 2016]. It is the most common mutation in Italy [Ladogana et al., 2005; Minikel et al., 2016]. Clinical presentations are similar to sJCD MM1 [Capellari et al., 2011; Kovacs et al., 2005]; The mean age at onset is 59–62 years (range 39 to 82 years) [Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016]. The median duration of disease is 5 months (range 2 to 20 months) [Krasnianski et al., 2016]. Approximately 88% of patients with the V210I mutation have negative family history for PrD or other neurological disorders in one report [Kovacs et al., 2005] and positive family history was reported as about 31% in another [Krasnianski et al., 2016].

First symptoms include dementia (38%), ataxia (15%), vertigo (15%), visual (15%), sleep (8%), sensory (8%) [Krasnianski et al., 2016] ). Clinical symptoms and signs during disease course are as follows; ataxia (100%), dementia (92%), extrapyramidal (92%), myoclonus (92%), visual/oculomotor (85%), pyramidal (71%), sensory (77%), vertigo (61.5%), headache (42%), hemianopsia (38.5%), and seizures (38.5%) [Krasnianski et al., 2016]. MRI positivity was reported in 15–33% of cases, although many of these did not include the more sensitive diffusion sequences (e.g. DWI and ADC map) [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016] and PSWCs on EEG were observed in 44–80% [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016]. Notably, CSF biomarkers were frequently positive; 14-3-3 positivity in about 90–100% [Breithaupt et al., 2013; Kovacs et al., 2005; Krasnianski et al., 2016] and total tau in 100% [Krasnianski et al., 2016]. We did not evaluate any cases with the V210I mutation in our UCSF cohort, although five cases were referred (Table 1).

M232R

The M232R mutation is one of the four most common mutations identified in the Japanese PrD cohort, and has been reported almost exclusively in patients with JCD from northeastern Asia (Japan, China and Korea) [Choi et al., 2009; Minikel et al., 2016; Nozaki et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2008]. Its pathogenicity, however, has been questioned by many as there is no functional evidence of pathogenicity, as it was only reported in JCD cases with no family history, and because the M232R variant has been identified in patients with dementia and no neuropathological findings of PrD and also in healthy individuals, with an estimated allelic frequency of more than 3% in the Japanese population [Beck et al., 2012; Higuma et al., 2013; Shiga et al., 2007]. In the ExAC cohort, the allele count of the variant was 10, and its penetrance was estimated to be approximately 0.1%, making it most likely a risk variant with a small effect size [Minikel et al., 2016]. The M232R mutation is almost always found along with MM at codon 129, but it should be noted that 92% of the Japanese population carries that polymorphism (and only 8% are MV) [Shiga et al., 2007].

The clinical presentation is very similar to that of sJCD with a mean age at onset of 64 years (range 15–81) and mean duration of disease of 8 months (range 0–32) [Nozaki et al., 2010], but two different clinical presentations have been reported by Japanese researchers, a rapid type (that represents about 75% of cases) and a slow type (25% of cases) [Shiga et al., 2007]. Both groups have relatively close ages at onset (mean 66.2±7.7 years in the rapid group and 57.6±15.4 years in the slow), but the duration until onset of akinetic-mutism (3.1±1.5 monthsin the rapid group and 20.6±4.4 months in the slow type group) [Shiga et al., 2007] and until death (12.5±10.9 months for rapid and 49.9±53.8 for slow) were quite different [Higuma et al., 2013].

Approximately 85% of patients have MRI scans consistent with JCD (and similar in both rapid and slow groups) [Nozaki et al., 2010; Shiga et al., 2007]. The frequency of PSWCs on EEG is higher in the rapid group (100% vs. 20%), and the positivity of 14-3-3 and tau in CSF are also higher among those with rapid progression (75% and 93% for 14-3-3 and tau respectively in the rapid type group and around 55% for both markers in the slow type group) [Higuma et al., 2013]. RT-Quic positivity was 78% in the rapid type group and 60% in the slow type group [Higuma et al., 2013].

The neuropathological findings in cases with rapid type JCD are similar to those of sJCD MM1, with type 1 PrPSc and synaptic-type deposits, whereas in the slow type group, the findings are similar to sJCD cortical-type MM2, with spongiform changes, perivacuolar PrP deposits and type 2 PrPSc [Higuma et al., 2013; Shiga et al., 2007].

T188R

Only two patients with T188R mutation have been reported, including one from our cohort [Roeber et al., 2008; Tartaglia et al., 2010]. The first was a 66-year-old who presented with visual impairment and developed dementia and mild ataxia several months later [Roeber et al., 2008]. There was no family history for dementia. Brain MRI at 12 months after onset did not show abnormalities consistent with gJCD, although the EEG showed PSWCs, and CSF NSE (38 ng/mL; > 30 consistent with JCD) and CSF 14-3-3 were positive. PRNP testing revealed T188R mutation with codon 129 VV. The patient died at 16 months after the onset without autopy. Our case was somewhat different, possibly because he was codon 129 MV (cis V) and thus had a trans methionine. He developed personality changes at age 55, followed by behavioral changes (poor judgement and delusion), and then rapid cognitive decline. Family history was unclear. Neurological examination showed moderate to severe impairment in memory, frontal-executive function, and language, mild left leg dysmetria and bilateral hand apraxia. MRI at 4 months after the onset showed mild diffuse cortical atrophy with restricted diffusion in the cortex and striatum. EEG showed slowing. CSF 14-3-3 was inconclusive, NSE was intermediate (26 ng/mL), and total tau was elevated at 2236.6 pg/mL (>1150 consistent with JCD). He developed myoclonus and mutism and died 14 months after the onset. The same mutation was found in his asymptomatic 80 year old father (codon 129MV) and 56 year old brother (codon 129 VV). The autopsy of the proband revealed diffuse neuronal loss, gliosis, spongiosis, and synaptic and plaque-like deposits of PrPSc in the cortex and cerebellar molecular layer, compatible with JCD [Tartaglia et al., 2010]. The pathogenic role of T188R mutation is not yet clear [Minikel et al., 2016]. The substitution of threonine to a highly basic amino acid, arginine, might result in structural destabilization, support a pathogenic role of T188R mutation. The cell culture studies demonstrated T188R mutation had increased resistance to proteinase K [Lorenz et al., 2002].

Three novel gJCD mutations in UCSF cohort

K194E

We found a novel K194E PRNP mutation in a 71 year old Caucasian gentlman who initially developed confusion and memory loss, progressing to dementia, profound psychiatric symptoms, parkinsonism, and gait instability over the following 10 months and death at 11 months after the onset. Overall his clinical features and MRI and EEG findings were consistent with JCD. Based on the pdc.org database, the side chain is pointing out into solvent so the change in charge for K194E may not be too significant, but it’s location at the end of helix 2 might suggest that the mutation has an impact on the correct folding of PrPC and thus it might be pathogenic. This is clearly a rare genetic variation as it was not idenfied in the 60,000 exomes in the ExAC database (Eric Minikel, personal communication) [Minikel et al., 2016] or in the 1000 Genomes Project database (http://www.internationalgenome.org/)[1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012]. To our knowledge, a cell cutlure or mouse model of this mutation has not yet been made, but the K194E variant is predicted to be “possibly damaging” by Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), “disease causing” by MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), and “damaging” by the SIFT algorithm (http://sift.jcvi.org/).

E200G

We indentified the novel E200G (codon 129VV) mutation in a symptomatic 57 year old Causasian woman who developed gait problems, followed six months later with language problems, and by 25 months, she was wheelchair bound and had difficulty following conversations. Neurological examination 25 months after onset revealed parkinsonism, symmetric decreased sensation in the lower limbs, and cerebellar gait ataxia. Her brain MRI was consistent with JCD, showing restricted diffusion in the cortex (mild cortical ribboning) and striatum. CSF total tau was elevated (1351pg/ml; >1150 consistent with JCD), 14-3-3 was inconclusive and NSE was intermediate (27 pg/ml (>30 consistent with JCD. She died 30 months after symptom onset, and although most of the neuropathological findings on autopsy were consistent with JCD with PrPSc type 2, some neuropathological findings, including the PrPSc Western blot glycosylation pattern, were not typical of sJCD, supporting that the E200G is pathogenic. Although she had known family history of PrD, her father died at age 50 from a rapidly progressive dementia diagnosed, likley incorrectly, as alcohol-related dementia [Kim et al., 2013].

A224V

A novel A224V mutation (cis codon 129V) was identified in a single symptomatic 48 year old woman diagnosed with JCD with rapid onset of short term memory problems, followed by gait and other motor problems. She died 32 months after disease onset. Despite this long disease course, she was in a very advanced disease state, non-ambulatory and non-verbal for at least the last 1.5 plus years, and probably had a prolonged survival due to an extraordinarily high level of aggressive around the clock care. Brain MRI showed classic cortical and subcortical restricted diffusion (Figure 2D), but with very prominent early hippocampal involvement (not shown). Both CSF NSE (39 ng/ml; >30 consistent with JCD) and total tau (6,300 pg/ml; >1200 consistent with JCD) were elevated. PRNP testing found homozygousity for valine at codon 129, and the neuropathological evaluation was consistent with JCD with type 1 PrPSc. The FMH was negative for known prion disease; her father carried the same mutation, but was heterozygous at codon 129 (MV) and at 86 years old has had a slowly progressive neurodegenerative dementia, most consistent with Alzheimer’s disease for at least the last 7 years. Running this mutation through Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) program (http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/score) to determine the likelihood of pathogenesis, suggested this variation to be possibly damaging. Furthermore, transmission experiments of prion strains obtained from frozen brain tissue of patients with sJCD (MM1, MV2, VV2) and from the proband into transgenic mice with human PrP containing the A224V cis codon 129V mutation and trans codon 129 either valine or methionine showed very different effects on incubation periods. The A224V mutation clearly had an impact on the incubaton period, and the codon 129 trans also had an effect. That having a trans codon 129M with A224V 129V extended incubation time to that closer to wildtype PRNP mice could explain why the proband’s father with the A224V 129V mutation but trans codon 129M has not developed obvious prion disease [Watts et al., 2015].

Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI)

D178N-129V

FFI is an unusual form of genetic JCD showing a distinctive phenotype caused by the mutation located at PRNP codon 178 coupled with methionine at cis codon 129 (D178N-129M). FFI is the third most common gPrD worldwide and the most common gPrD in Germany [Gambetti et al., 2003b; Krasnianski et al., 2016]. The term FFI was first used in 1986 to describe the phenotype of an Italian family presenting with progressive insomnia, disturbances in autonomic function and progressive clinical motor deterioration leading to death [Lugaresi et al., 1986]. Subsequently, several years later, sequencing of the PRNP gene in three symptomatic members confirmed the mutation with a cis codon 129M, defining a novel subtype of gPrD [Goldfarb et al., 1992]. As noted above, in D178N, the 129 codon polymorphism has a strong effect on the clinicopathological phenotype, with cis codon V associated more with the JCD phenotype and cis codon 129M associated with an FFI phenotype [Krasnianski et al., 2008].