Abstract

Background:

“Breast implant illness” (BII) is a poorly defined cluster of nonspecific symptoms, attributed by patients as being caused by their breast implants. These symptoms can include joint pain, skin and hair changes, concentration, and fatigue. Many patients complaining of BII symptoms are dismissed as psychosomatic. There are currently over 10,000 peer-reviewed articles on breast implants, but at the time of commencing this study, only 2 articles discussed this entity. At the same time, mainstream media and social media are exploding with nonscientific discussion about BII.

Methods:

We have prospectively followed 50 consecutive patients, self-referring for explantation due to BII. We analyzed their preoperative symptoms and followed up each patient with a Patient-Reported Outcome Questionnaire. All implants and capsules were, if possible, removed en bloc. Explanted implants were photographed. Implant shell and capsule sent for histology and microbiological culture.

Results:

BII symptoms were not shown to correlate with any particular implant type, surface, or fill. There was no significant finding as to duration of implant or location of original surgery. Chronic infection was found in 36% of cases with Propionibacterium acnes the most common finding. Histologically, synoviocyte metaplasia was found in a significantly greater incidence than a matched cohort that had no BII symptoms (P = 0.0164). Eighty-four percent of patients reported partial or complete resolution of BII symptoms on Patient-Reported Outcome Questionnaire. None of the 50 patients would consider having breast implants again.

Conclusion:

The authors believe BII to be a genuine entity worthy of further study. We have identified microbiological and histological abnormalities in a significant number of patients identifying as having BII. A large proportion of these patients have reported resolution or improvement of their symptoms in patient-reported outcomes. Improved microbiology culture techniques may identify a larger proportion of chronic infection, and further investigation of immune phenotypes and toxicology may also be warranted in this group.

INTRODUCTION

Breast implant illness (BII) is a poorly defined cluster of nonspecific symptoms, attributed by patients as being caused by their breast implants. There is a circulating list of over 56 different symptoms, and there is very little scientific consensus that the entity even exists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Online Circulating Table of Breast Implant Illness Symptoms

| Fatigue or chronic fatigue | Slow muscle recovery after activity |

| Cognitive dysfunction (brain fog, difficulty concentrating, memory loss) | Heart palpitations, changes in normal heart rate, or heart pain |

| Muscle pain and weakness, joint pain | Sore and aching joints of shoulders, hips, backbone, hands, and feet |

| Hair loss, dry skin, and hair | |

| Swollen and tender lymph nodes in breast area, underarm, throat, neck, groin | |

| Premature aging | Bouts of dehydration for no reason |

| Frequent urination | |

| Poor sleep and insomnia | Numbness/tingling sensation around implant and/or underarm |

| Dry eyes, decline in vision, vision disturbances | |

| Hypo/hyperthyroid symptoms | Liver and kidney dysfunction |

| Hypo/hyperadrenal symptoms | Cramping |

| Estrogen/progesterone imbalance or diminishing hormones | Toxic shock symptoms |

| Anxiety, depression, and panic attacks | |

| Symptoms of or diagnosis of fibromyalgia | |

| Slow healing of cuts and scrapes, easy bruising | Symptoms of or diagnosis of Lyme disease |

| Throat clearing, cough, difficulty swallowing, choking, reflux Vertigo | Symptoms of or diagnosis of autoimmune diseases such as Raynaud’s syndrome, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, nonspecific connection tissue disease, multiple sclerosis |

| Gastrointestinal and digestive issues | |

| Fevers, night sweats, intolerant to heat | |

| New and persistent bacterial and viral infections | |

| Symptoms of or diagnosis of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma | |

| Slow clearing of common colds and flu | |

| Fungal infections, yeast infections, Candida, sinus infections | |

| Skin rashes | |

| Ear ringing | |

| Sudden food intolerance and allergies | |

| Headaches |

There are currently over 10,000 peer-reviewed articles on breast implants, but at the time of commencing this study, only 2 papers discussed this entity. At the same time, mainstream media and social media are exploding with nonscientific discussion about BII.1,2

Many women are presenting to surgeons with a self-diagnosis of BII, based on their contacts in social media, and requesting removal of implant.

The aims of this study are to attempt to:

Define the most common signs and symptoms of this illness.

Identify the microbiological and histopathological profile of this illness.

Explore the efficacy of explant with capsulectomy as a treatment modality.

METHODS

We performed a prospective cohort study of 50 breast implant explantations on women presenting with a self-diagnosis of BII. These were statistically matched to an equal control cohort having removal with replacement of implants and, therefore, by definition did not have BII concerns. Consent for the procedure and study was obtained from the patients in line with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

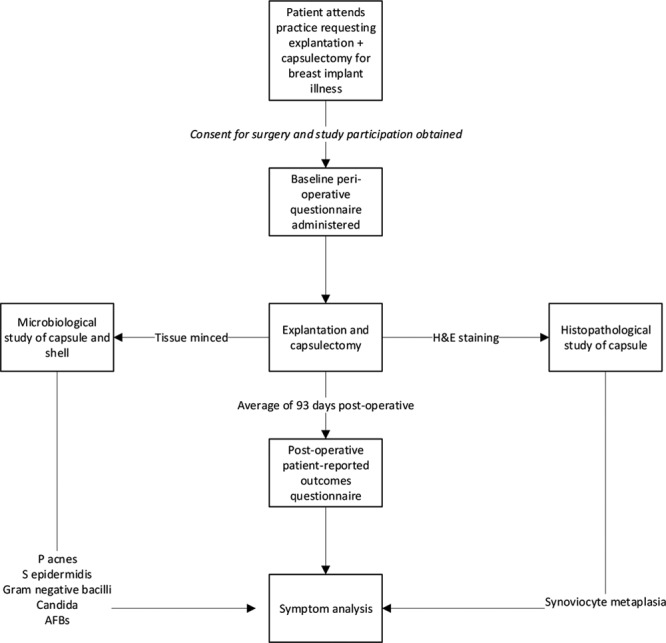

An extensive preoperative questionnaire was administered (Table 2), recording demographic information of the patient and implant surgery, as well as detailing the self-reported symptoms. The statistically matched cohort of 50 female patients in the control group had no BII symptoms reported on administration of the same preoperative questionnaire (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Breast Implant Illness Perioperative Questionnaire

| Questionnaire Category | Questionnaire |

|---|---|

| Implant history | Implant insertion date Purpose of implant (cosmetic/reconstruction) Geographic location |

| Shape, texture, and fill | |

| Brand | |

| History of illness | Onset of symptoms |

| Preimplant disease: type 2 diabetes, thyroid disease, breast cancer, postimplant chemo/immune/radiotherapy | |

| Prior diagnosis of acne | |

| Record of symptoms | Record of individual symptoms as per symptom list and other self-reported symptom |

| Record of postimplant symptom resolution, improvement, or persistence |

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of BII cohort. AFB indicates Acid-Fast Bacilli; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Surgical Methods

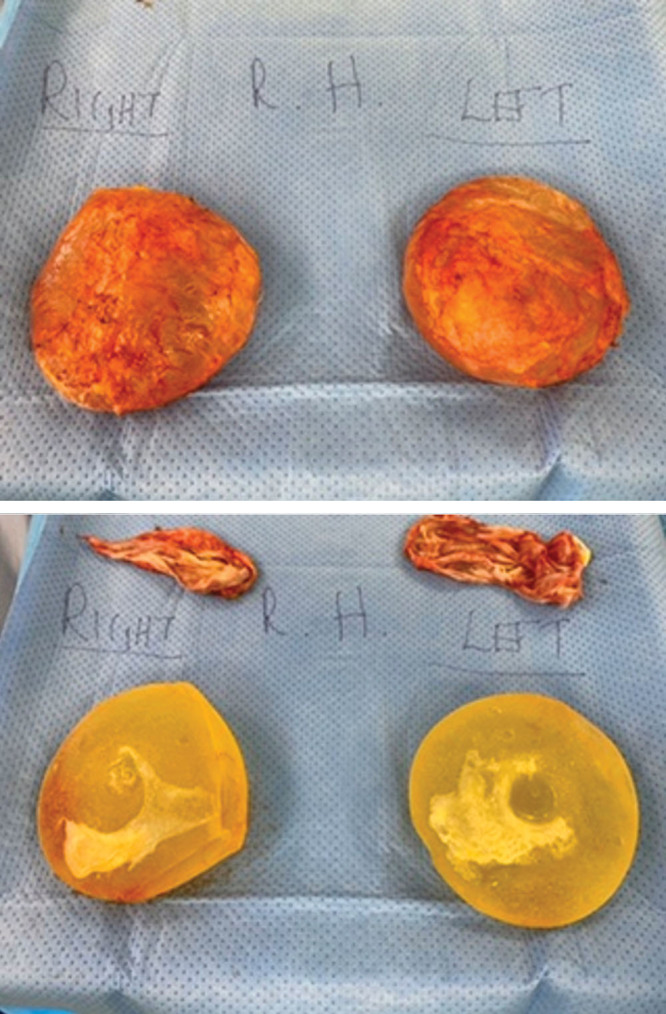

Skin was prepared with chlorhexidine alcohol in all patients, employing sterile technique. Patients had explantation performed via an existing inframammary incision or through a concurrent reduction/mastopexy in the same procedure. Patients in both groups had bilateral capsulectomies performed, with concurrent en bloc removal of the breast implant and overlying capsule where possible (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

En bloc explant capsulectomy.

The explanted implants and capsules were removed and transferred directly to a sterile Mayo table while minimizing skin contact and photographed to add to each patient’s data set. The implants and capsule were subjected to microbiological and histopathological studies. The capsule was divided using fresh instruments by the same operator, with one part sent for microbiological analysis and the remainder sent for histopathological analysis. Part of the implant shell itself was sent for microbiological analysis. Antibiotics were delayed until after capsulectomy.

Histopathological assessment of the capsule involved hematoxylin and eosin staining of one equal-sized 25 cm2 sample from each side, and subsequent conventional light microscopy performed by an FRCPA-qualified pathologist specializing in breast tissue. The presence of synoviocyte metaplasia, lymphoid follicle aggregates, macrophages, and foreign body granulomata was noted in these reports.

Microbiological assessment of the capsule consisted of sterile transport within 2 hours, grinding of tissue, microscopy and culture for aerobes, atypical organisms including acid-fast bacilli, and fungi (Table 3). For anaerobic culture, extended incubation in anaerobe agar culture was employed for 5–8 days before reading (Table 3).

Table 3.

Culture Methods Employed in This Study

| Clinical Details/Conditions | Standard Media | Incubation | Culture Read | Target Organism(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature °C | Atmosphere | Time | ||||

| All samples | Blood agar | 35–37 | 5–10% CO2 | 5 d | Daily | Any organism |

| C.N.A. agar | 35–37 | 5–10% CO2 | 5 d | Daily | Any organism | |

| CLED agar | 35–37 | Air | 5 d | Daily | Any organism | |

| Anaerobe agar | 35–37 | Anaerobic | 48 h | 48 h | Any organism | |

| Chocolate agar | 35–37 | 5–10% CO2 | 5 d | Daily | Any organism | |

| Sabouraud agar | 35–37 + RT | Air | 5 d | Daily weekly | Fungi | |

| 4 wk | ||||||

| TSB broth | 35–37 | Air | 5 d | Daily | Any organism | |

CLED indicates cystine-lactose-electrolyte deficient; C.N.A., Columbia Naladixic acid; RT, room temperature; TSB, Tryptic soy.

The BII cohort patients were reinterviewed an average of 93 days postsurgery with a Patient-Reported Outcome Questionnaire (PRO-Q) to ascertain symptom improvement, resolution, or persistence.

The resulting survey, microbiology, and histopathological results were analyzed, and the findings presented.

SPSS was used to analyze categorical and continuous data (IBM Corp, Released 2016, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0, Armonk, N.Y.). Student’s t test was employed to determine statistical matching of continuous data of the BII group to controls, with Fisher’s exact test and χ2 tests used for determining statistical matching of categorical data. Subsequent analysis using χ2 2 × 2 contingency tables determined statistical significance of difference in symptoms and treatment efficacy following explantation.

RESULTS

The BII and Control groups were matched for age, duration of implant, and implant type, with no significant difference statistically; these are outlined in Table 4. In the BII cohort, 6 out of the original 50 patients were lost to follow-up, with a mean follow-up period of 93 days. There was no difference in the proportion of saline and silicone implants between the BII and control groups. None of the patients in the BII group were considering reimplant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cohort Comparison BII Group versus Control Group

| BII Group | Control Group | Test Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age | 42 | 46 | 0.796 (−2.75 to 2.75)* | 0.572* |

| Average duration of implant | 3–5 y | 3–5 y | — | 0.876† |

| Average number of days from follow-up | 93 d | 90 d | 1.9327 | 0.0599* |

| Number that would consider reimplantation | 0 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| No. discrete symptoms reported | 54 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Patients with silicone implants | 47 | 45 | — | 0.715‡ |

| Patients with saline implants | 3 | 5 | — | 0.715‡ |

| Patients with textured implants | 44 | 38 | — | 0.845‡ |

| Patients with smooth implants | 6 | 12 | — | 0.845‡ |

P value significant <0.05.

*Student’s t test.

†χ2 calculation.

‡Fisher’s exact test.

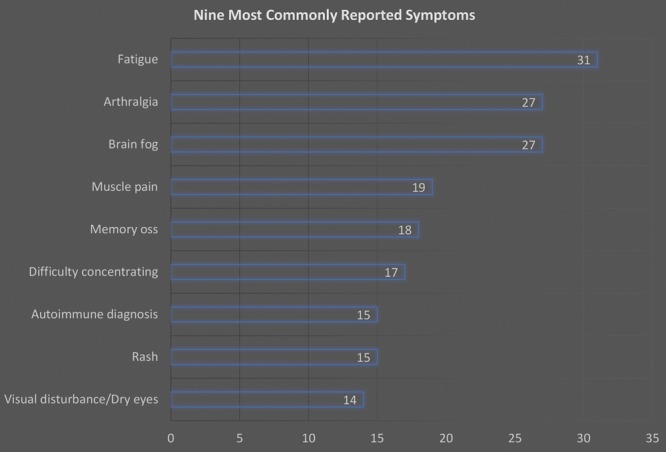

Symptom Survey

The BII group presented with 56 different symptoms. Out of the cohort of 50, 6 were lost to follow-up. The 9 most common symptoms reported by the remaining 44 patients were fatigue (n = 31), arthralgia (n = 27), brain fog (n = 27), myalgia (n = 19), memory loss (n = 18), difficulty concentrating (n = 17), autoimmune diagnosis (n = 15), rash (n = 15), and visual disturbance/dry eyes (n = 14) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Nine most commonly reported symptoms.

Out of 44 responding patients, 43 reported having at least 1 of the 9 most common symptoms, with 18 patients reporting having at least 5 symptoms. Of note, 15 patients reported autoimmune diagnoses that were alleged to have been diagnosed after the breast augmentation, including Grave’s thyroiditis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, coeliac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Histopathological and Microbiological Survey

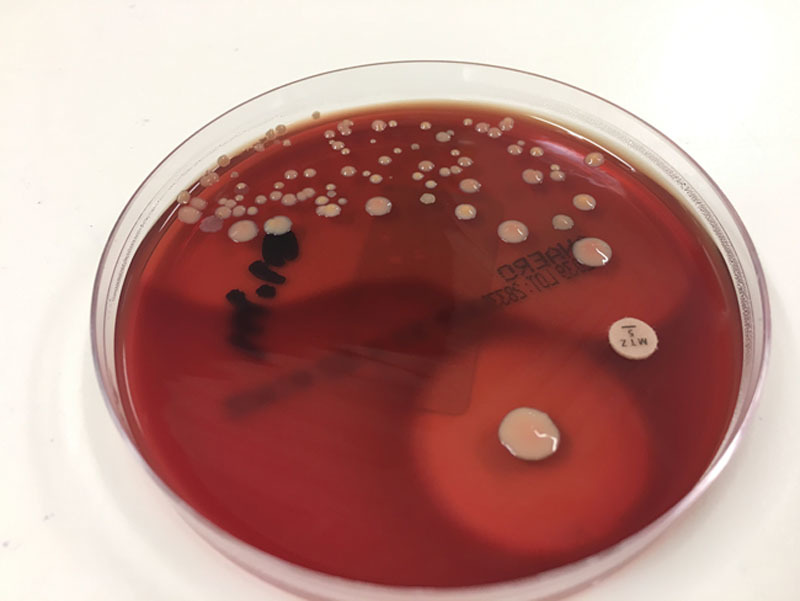

Comparison of BII and control groups revealed key histopathological and microbiological differences. The BII group had a 50% higher rate of synoviocyte metaplasia than that of controls (P = 0.0164) (Table 5). Additionally, the BII group had a 6-fold greater rate of positive cultures (P = 0.0002), with the most prominent organism being Propionibacterium acnes. Small and equal quantities of Staphylococcus epidermidis was cultured in both the BII and Control groups. There was no other growth in the control group. Although there was a slightly higher rate of foreign body granuloma in the BII group, the difference with the control group was not statistically significant (P = 0.2213). Other patients in the BII group had polymicrobial growth (n = 1), Gram-negative bacillus (n = 1), and Candida (n = 1) (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Microbiological and Histopathological Profile

| BII (n = 50) | Control (n = 50) | P (χ2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synoviocyte metaplasia | 31 (62%) | 19 (38%) | 0.0164 |

| Foreign body granuloma | 21 (42%) | 15 (30%) | 0.2113 |

| Positive culture | 18 (36%) | 3 (6%) | 0.0002 |

| S. epidermidis | 3 | 3 | |

| P. acnes | 12 | 0 | |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 1 | 0 | |

| Candida spp. | 1 | 0 | |

| Polymicrobial | 1 | 0 | |

| Acid-fast bacilli | 0 | 0 |

P value significant <0.05.

Fig. 4.

Propionibacterium cultured from symptomatic patient.

Although culture for acid-fast bacilli and atypical organisms was undertaken in both groups, these were not cultured in either group.

Efficacy of Explantation and Capsulectomy in Resolving Symptoms

Postexplant symptom improvement, resolution, or persistence was surveyed among the BII group (n = 50, Table 6). Six were lost to follow-up. Overall, including examination of less common symptoms, explantation, and capsulectomy improved or resolved symptoms in 42 out of 44 patients surveyed (P = 0.0005).

Table 6.

The Nine Most Common Symptoms, with Rate of Postoperative Recovery

| Symptom Category | BII (n = 50) | Postoperative Improvement or Resolution | P (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up | 6 | — | |

| No. patients with the 9 most common symptoms | |||

| None | 1 | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| At least 1 | 43 | — | — |

| At least 2 | 38 | — | — |

| At least 3 | 31 | — | — |

| At least 4 | 25 | — | — |

| 5 or more | 19 | — | — |

| Soft tissue | |||

| Arthralgia | 27 | 23 | 0.001402 |

| Myalgia | 19 | 14 | 0.02742 |

| Dry eyes/visual disturbance | 14 | 11 | 0.01734 |

| Rash | 15 | 14 | 0.001602 |

| Autoimmune diagnosis | 15 | 14 | 0.09029 |

| Cognitive | |||

| Difficulty concentrating | 17 | 12 | 0.02896 |

| Brain fog | 27 | 20 | 0.01116 |

| Memory loss | 18 | 13 | 0.02192 |

| Fatigue | 31 | 27 | 0.000891 |

| Overall efficacy of resolving or improving at least 1 common symptom | 43 | 39 | 0.00160 |

| Overall efficacy of resolving or improving any self-reported symptom | 44 | 42 | 0.0005 |

P value significant <0.05.

In analyzing patients with the 9 most common symptoms (Table 6), 4 patients reported persistence of all preoperative symptoms. One patient did not possess any of the 9 most common symptoms. However, the remainder (n = 39; 90.7% of the responding group or 78% of the greater BII cohort) reported improvement or resolution of at least some of their symptoms, with high statistical significance (P = 0.016). With the exception of autoimmune diagnoses (P = 0.09), explantation with capsulectomy improved or resolved common symptoms with high statistical significance (P < 0.05). Many patients with autoimmune diagnoses were unable to quantify or declare resolution as the flare cycle for their conditions may have laid outside the postoperative survey window (Table 6).

The sole patient who did not report any of the common symptoms reported intermittent sharp breast and chest pain, which had resolved postexplant. Of the 4 patients whose common symptoms persisted, 2 did not report any improvement in any of the less common symptoms, whereas a further 2 patients reported improvement or resolution in irritable bowel symptoms, lymphadenopathy, palpitation, and indigestion.

With respect to the presence of synoviocyte metaplasia, there was no statistically significant difference demonstrated in explant efficacy for individual symptoms (Table 7). Although patients with P. acnes on culture were more likely to see resolution or improvement of common symptoms compared with patients with negative cultures, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 8). This may be due to small sample size, or potentially arising from false-negative cultures. Additionally, there was no statistically significant difference in symptom distribution nor efficacy when comparing saline and silicone implants (Table 9).

Table 7.

Common Symptoms and Synoviocyte Metaplasia with Postoperative Recovery

| Synoviocyte Metaplasia Present (n = 31) | Symptom Improved Postoperatively | Synoviocyte Metaplasia Absent (n = 29) | Symptom Improved Postoperatively | Postoperative P (χ2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up | 2 | — | 4 | — | — |

| Soft tissue | |||||

| Myalgia | 10 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 0.1926 |

| Arthralgia | 17 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 0.6194 |

| Rash | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | — |

| Autoimmune diagnosis | 11 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.7022 |

| Dry eyes/visual disturbance | 10 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 0.2102 |

| Cognitive | |||||

| Difficulty concentrating | 11 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 0.7759 |

| Brain fog | 18 | 15 | 9 | 5 | 0.2480 |

| Memory loss | 11 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 0.1035 |

| Fatigue | 22 | 19 | 9 | 8 | 0.8666 |

P value significant <0.05.

Table 8.

Common Symptoms Compared with P. acnes and No Bacteria, with Postoperative Recovery

| P acnes (n = 12) | Symptom Improved Postoperatively, (n =) | No Bacteria Cultured (n = 32) | Symptom Improved Postoperatively (n =) | Baseline Symptoms P (χ2) | Postoperative P (χ2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up | 2 | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| Soft tissue | ||||||

| Myalgia | 2 | 2 | 15 | 10 | 0.6582 | 0.3333 |

| Arthralgia | 7 | 7 | 18 | 14 | 0.9011 | 0.2396 |

| Rash | 4 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 0.0535 | 0.2344 |

| Autoimmune diagnosis | 4 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 0.9482 | 0.2844 |

| Dry eyes/visual disturbance | 3 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 0.5521 | 0.1786 |

| Cognitive | ||||||

| Difficulty concentrating | 6 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 0.3431 | 0.1892 |

| Brain fog | 7 | 5 | 18 | 13 | 0.9011 | 0.9501 |

| Memory loss | 2 | 2 | 14 | 9 | 0.0962 | 0.4343 |

| Fatigue | 8 | 7 | 19 | 8 | 0.6580 | 0.03776 |

P value significant <0.05.

Table 9.

Common Symptoms Compared with Implant Fill

| Symptom | NaCl Fill (n = 6) | Symptom Improved Postoperatively (n =) | Si Fill n = 44 | Symptom Improved Postoperatively (n =) | Baseline Symptoms P (χ2) | Postoperative P (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up | 1 | — | 5 | — | — | — |

| Soft tissue | 4 | |||||

| Muscle pain | 4 | 2 | 35 | 12 | 0.4749 | 0.5348 |

| Arthralgia | 5 | 2 | 36 | 21 | 0.3840 | 0.7491 |

| Autoimmune diagnosis | 5 | 0 | 29 | 5 | 0.3907 | — |

| Rash | 4 | 1 | 39 | 13 | 0.1457 | 0.5452 |

| Visual disturbance/dry eyes | 4 | 0 | 37 | 11 | 0.2973 | — |

| Cognitive | ||||||

| Fatigue | 5 | 2 | 35 | 25 | 0.8274 | 0.2937 |

| Brain fog | 3 | 2 | 34 | 18 | 0.2239 | 0.6474 |

| Memory loss | 3 | 0 | 36 | 13 | 0.0577 | — |

| Difficulty concentrating | 3 | 2 | 36 | 10 | 0.0577 | 0.1608 |

Significant if P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The Case for BII

Although BII has yet to reach mainstream acceptance in medical/scientific fields, concern regarding the appearance of systemic illness following the insertion of breast implants has been present for decades.3–16 The nebulous and varied nature of symptoms, along with the difficulty of identifying causative agents, has rendered the phenomenon difficult to examine, although the efficacy of explantation as a treatment has been well demonstrated.5,9,10

This study detailed 56 discrete symptoms attributed to BII by patients. We noted the 9 most common symptoms present in 90% of this cohort. Most patients experienced improvement or resolution of these symptoms following explantation with capsulectomy, including clinical remission of a number of autoimmune presentations.

The most common symptoms can be generalized into (1) musculoskeletal, (2) cognitive, and (3) systemic. Musculoskeletal symptoms include myalgia and arthralgia. Cognitive symptoms are brain fog, memory loss, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. Systemic/rheumatological symptoms include visual disturbance/dry eyes, rash, and autoimmune diagnoses. This compares with similar reports in literature.3,5,6,13,16

The catalogue of common symptoms, along with clinical resolution of symptoms following explant and capsulectomy, suggests that BII may be a distinct clinical entity that warrants further medical and scientific inquiry. We feel that these data can help further define this entity.

The Biofilm Hypothesis

This study identified positive bacterial cultures in 36% of the BII cohort compared with 6% of controls. The most common organism was P. acnes (Fig. 5), constituting two thirds of the culture-positive findings, followed by S. epidermidis constituting one-sixth of culture-positive findings. The possibility that chronic indolent P. acnes infection of the breast implant shell and capsule could cause systemic illness needs to be explored.

Fig. 5.

P. acnes under microscopy, grown in thioglycollate medium. Source: Bob Strong, Centre for Disease Control. https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=3083. This image is in the public domain and thus free of any copyright restrictions.

Research into P. acnes and polymicrobial biofilm as a disease model for breast implant capsular contracture has been established recently17–20 and identified key issues associated with the difficulty of diagnosing an infection via conventional culture methods. Microorganisms within the biofilm structure are shielded from normal immunologic processes and are sessile; they are not as active in reproducing as bacteria in the planktonic form.18,21 Their sessile state renders difficult culture of these organisms, with other studies recommending mincing and sonication of specimen tissue to extract microorganisms from the biofilm milieu, with subsequent prolonged culture protocols.17

A slimy biofilm structure was clinically apparent during surgery in nearly all BII patients and a smaller number of controls. Positive culture rates were low in both groups, though it was 6 times higher in the BII group compared with control (18 versus 3; P < 0.05). At the time of the study, sonication facilities were not available in Western Australia, and differing prolonged culture methods were employed to achieve the yield. Better culture techniques may yield a higher infection rate.

P. acnes is being explored as a pathogen with various rheumatological disorders, including thyroid disease, sarcoidosis, endophthalmitis, and prostate disease.19,20,22 P. acnes has been found in the lymph nodes of patients suffering atherosclerosis, sarcoidosis, and discitis associated with sciatica. It is implicated in both SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome and CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) disease.20 Per-oral clarithromycin treatment of P. acnes in the lymph nodes of a sarcoidosis patient yielded disease resolution.23 This study raises the exciting prospect of possibly antibiotic treatment of BII or prevention with altered antibiotic prophylaxis regimes.

Earlier studies for infective etiology explored the possibility of the so-called commensal contaminants being a cause for disease.3,9,16 Agents including anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and atypical organisms such as acid-fast bacilli were explored. These studies have demonstrated colonization of implants and capsular tissue with S. epidermidis, although its significance as a causative agent was subject to further study. Other organisms, such as Escherichia coli and P. acnes were also noted, albeit in reduced numbers.3,16

The development of bacterial infection in the setting of the implant capsule may be supported by the finding that natural killer cell function is suppressed in the presence of a breast implant but is then reversed upon explantation.24

The finding of P. acnes constitutes 24% of symptomatic patients in this series, with the majority of patients having negative cultures. This might reflect the difficulty in culturing P. acnes that is found in metabolically sessile biofilm. Indeed, the larger proportion of symptomatic patients had textured implants, which may harbor greater amounts of biofilm.

Sample contamination during handling processes and the possibility of natural commensal Propionibacterium spp. contaminating the sample are confounders that will need further definition in future studies. In the opinion of the author, contaminated samples should demonstrate a polymicrobial positive culture result, especially when considering that other organisms such as Staphylococcus spp. are more easily cultured.

Histopathological Differences between Normal Breast Implant Capsules and Capsules with Synoviocyte Metaplasia

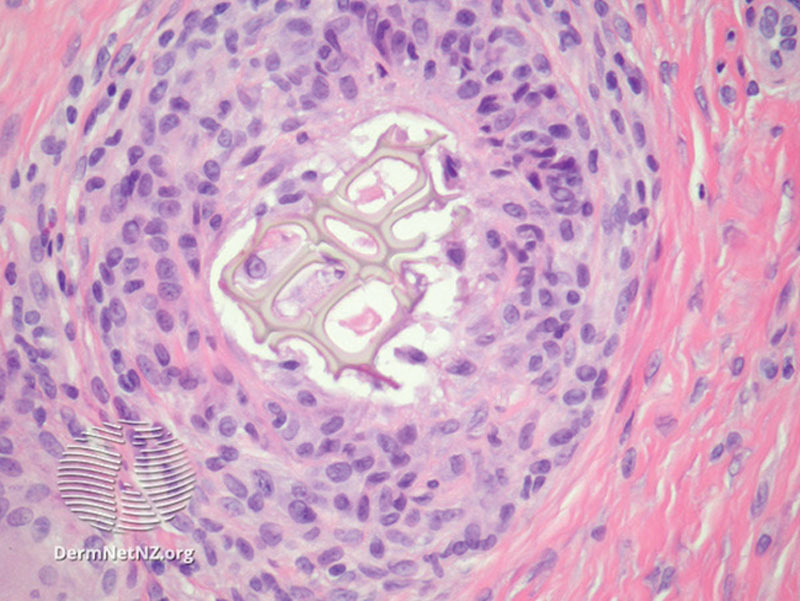

This study noted a 50% increased incidence of capsule synoviocyte metaplasia in the BII cohort, compared with the control cohort (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Synovial metaplasia surrounding foreign body granuloma. Source: Emauel, P. Synovial metaplasia pathology. Dermnet NZ. Available at: https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/synovial-metaplasia-pathology/. Creative Commons Licensing, no changes made. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/nz/legalcode.

Synoviocyte metaplasia etiology is thought secondary to the production of hyaline surfaces following contact with hydrophobic and mobile objects.4,25–27 Synoviocyte metaplasia has been demonstrated surrounding arthroplasty implants, implanted pacemakers, and breast implant prostheses.25 Synoviocyte metaplasia is also seen in cartilaginous tissue affected by rheumatoid arthritis.28 Studies describe 2 types of synoviocyte metaplasia; macrophage-based type A synoviocyte metaplasia is considered benign, whereas fibroblast-based type B synoviocyte metaplasia is known for producing proteolytic enzymes that degrade cartilage and proinflammatory cytokines and is thought to be a key effector cell in rheumatoid arthritis.28

We feel that the significant increased synoviocyte metaplasia incidence in the BII group over the control group warrants further investigation.

Noninfective Suspected Etiologies

Direct Chemical Toxicity

Patients raised concerns that BII symptoms may be secondary to chemical toxicity associated with implant materials and catalysts. Assertions have been raised about purported heavy metals, pathological organic compounds, and toxicity associated with industrial silicone in Polyimplant Prothese devices.20,29

Platinum is used as a catalyst in the cross-linking of silicone elastomers and may be present in silicone implant shells in microgram quantities. Neurotoxicity is demonstrated with platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents, but not with elemental platinum. Lykissa et al29 claimed that the compound hexachloroplatinate was found in implants; however, repeated studies have failed to replicate this. Brook30 found that the quantity of platinum in implants is in the parts-per-million range, in the unoxidized form, making biologically reactivity unlikely.

At the time of writing, there is no evidence associating neurotoxicity or autoimmune disease with silicone gel, though there is evidence of silicone promoting fibrosis locally as well as in distant sites.

Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Adjuvant

The hypothesis that silicone may act as an autoimmune adjuvant has been extensively studied, with mixed results.12,14 The evidence for silicone adjuvant activity remains elusive, though there have been hundreds of studies on the topic.31

Studies of patients with breast implants who self-reported neurological disease hypothesized that silicone could trigger an autoimmune neurological syndrome; evidence of raised antiganglioside M1 has been offered as an explanation; however, antiganglioside M1 is neither specific to nor diagnostic for any neurological disorder.32

The presence of systemic disease in patients who possessed saline implants, which lack silicone throughout its structure, suggests that the silicone adjuvant theory is inadequate to explain BII.

Human Leukocyte Antigen Subtype Incompatibility

One series identified a higher prevalence of the human leukocyte antigen DR23 (HLA-DR23) subtype in symptomatic patients with breast implants than in asymptomatic patients with breast implants.33 The same study also found a significant overlap with HLA-DR23 and patients with fibromyalgia and that a lower HLA-DR23 prevalence in asymptomatic patient without implants, and healthy patients without implants.

Two explanations are offered; that HLA-DR23 sensitizes to having an adverse reaction to the implant, or that HLA-DR23 predisposes to systemic disease mimicking fibromyalgia, and that the presence of implants is serendipitous.33

No other studies involving systemic illness and HLA subtype with other types of implants have been done, for example, pacemakers or arthroplasty devices.

The reversibility of symptoms following explantation demonstrated in our study as well as others suggests that the BII clinical entity is less likely to be a misdiagnosis of existing systemic inflammatory disease.

BII as a Somatization Disorder

The paucity of clinical evidence lead to the suggestion that BII may be a psychosomatic entity, following psychological fixation of common symptoms as an error of attribution to a foreign body, amplified by the influence of shared experience in social media.1 One study suggests that patients with BII may be experiencing anxiety and subsequent somatization, with elevated anxiety scores demonstrated on testing.2,34

It is thought that explantation causes cathartic psychological relief of the symptoms derived from psychological fixation to the foreign body implant.34

Although the psychosomatic etiology may explain some subjective symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, it is inadequate for explaining the onset of objective disorders such as rashes and the remission or resolution of autoimmune disease following the explantation. Additionally, there is no evidence to support the presence of any Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Axis I disorder in this cohort.

Limitations

This is an initial observational study comparing symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients requesting explant, with an exploration and cataloguing of their symptoms.

Existing Breast PRO-Q instruments were inadequate for assessing these patients, as the question set assessed subjective impressions toward augmentation, rather than systemic symptoms. A modified Breast PRO-Q was formulated specifically to gauge symptoms and their course following explantation.

Culture yield on symptomatic patients was low. Although this may reflect a true sterile culture, it is worth noting that facultative anaerobes such as P. acnes can be difficult to incubate, especially when introduced in their sessile state from biofilm, necessitating specialized processes to culture. The lack of availability of biofilm fracturing modalities such as sonication and high sensitivity detection modalities such as electron microscopy and 16s RNA testing could enhance culture yields when employed in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

We feel that the results support BII as an entity worthy of future study. We have delineated the 9 most common presenting symptoms and demonstrated distinct histopathological and microbiological differences from the control group. P. acnes biofilm is the most commonly found possible cause. Implant removal and capsulectomy is an effective treatment modality for patients presenting with this cluster of symptoms.

A further Phase 2 trial is warranted, with a more refined PRO-Q, better microbiological assessment techniques, plus the addition of HLA typing and toxicology.

Footnotes

Published online 30 April 2020.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang SY, Israel JS, Afifi AM. Breast implant illness: symptoms, patient concerns, and the power of social media. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:765e–766e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahern M, Smith M, Chua H, et al. Breast implants and illness: a model of psychological illness. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobke MK, Svahn JK, Vastine VL, et al. Characterization of microbial presence at the surface of silicone mammary implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:563–569; disscusion 570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleiweiss IJ, Klein MJ, Copeland M. Breast prosthesis reaction. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:505–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthur EB. Amelioration of systemic disease after removal of silicone gel-filled breast implants. J Nutr Environ Med. 2000;10:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brawer AE. Chronology of systemic disease development in 300 symptomatic recipients of silicone gel-filled breast implants. J Clean Technol Environ Toxicol Occup Med. 1996;5:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer M, Colaris M, van der Hulst RRWJ, et al. Is explantation of silicone breast implants useful in patients with complaints? Immunol Res. 2017;65:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackburn WD, Jr, Grotting JC, Everson MP. Lack of evidence of systemic inflammatory rheumatic disorders in symptomatic women with breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1054–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn CY, Ko CY, Wagar EA, et al. Microbial evaluation: 139 implants removed from symptomatic patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1225–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrich RJ, Kenkel JM, Adams WP, et al. A prospective analysis of patients undergoing silicone breast implant explantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2529–2537; discussion 2538–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schleiter KE. Silicone breast implant litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida SH, Swan S, Teuber SS, et al. Silicone breast implants: immunotoxic and epidemiologic issues. Life Sci. 1995;56:1299–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fryzek JP, Signorello LB, Hakelius L, et al. Self-reported symptoms among women after cosmetic breast implant and breast reduction surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoenfeld Y, Agmon-Levin N. ‘ASIA’ – Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnusson MR, Cooter RD, Rakhorst H, et al. Breast implant illness: a way forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(3S A Review of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):74S–81S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowden RV. Periprosthetic bacteria and the breast implant patient with systemic symptoms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allan JM, Jacombs AS, Hu H, et al. Detection of bacterial biofilm in double capsule surrounding mammary implants: findings in human and porcine breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:578e–580e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deva AK, Adams WP, Jr, Vickery K. The role of bacterial biofilms in device-associated infection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1319–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portillo ME, Corvec S, Borens O, et al. Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in implant-associated infections. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:804391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aubin GG, Portillo ME, Trampuz A, et al. Propionibacterium acnes, an emerging pathogen: from acne to implant-infections, from phylotype to resistance. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mempin M, Hu H, Chowdhury D, et al. The A, B and C’s of silicone breast implants: anaplastic large cell lymphoma, biofilm and capsular contracture. Materials (Basel). 2018;11:E2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs AM, Van Hooff ML, Meis JF, et al. Treatment of prosthetic joint infections due to propionibacterium. Similar results in 60 patients treated with and without rifampicin. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemori N, Nakamura M, Kojima M, et al. Successful treatment in a case of Propionibacterium acnes-associated sarcoidosis with clarithromycin administration: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell A, Brautbar N, Vojdani A. Suppressed natural killer cell activity in patients with silicone breast implants: reversal upon explantation. Toxicol Ind Health. 1994;10:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler MR, Nathan CO, Abreo F. Synovial metaplasia, a specialized form of repair. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:727–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bui JM, Perry T, Ren CD, et al. Histological characterization of human breast implant capsules. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39:306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Bárcena C, Muñoz-Hernández P. Cytological features of breast peri-implant papillary synovial metaplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:769–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lykissa ED, Kala SV, Hurley JB, et al. Release of low molecular weight silicones and platinum from silicone breast implants. Anal Chem. 1997;69:4912–4916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brook MA. Platinum in silicone breast implants. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3274–3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohrich RJ. Safety of silicone breast implants: scientific validation/vindication at last. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1786–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg NL. The neuromythology of silicone breast implants. Neurology. 1996;46:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young VL, Nemecek JR, Schwartz BD, et al. HLA typing in women with breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1497–684; discussion 684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dush DM. Breast implants and illness: a model of psychological factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:653–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]