Abstract

The signalling pathways that regulate intercellular trafficking via plasmodesmata (PD) remain largely unknown. Analyses of mutants with defects in intercellular trafficking led to the hypothesis that chloroplasts are important for controlling PD, probably by retrograde signalling to the nucleus to regulate expression of genes that influence PD formation and function, an idea encapsulated in the organelle-nucleus-PD signalling (ONPS) hypothesis. ONPS is supported by findings that point to chloroplast redox state as also modulating PD. Here, we have attempted to further elucidate details of ONPS. Through reverse genetics, expression of select nucleus-encoded genes with known or predicted roles in chloroplast gene expression was knocked down, and the effects on intercellular trafficking were then assessed. Silencing most genes resulted in chlorosis, and the expression of several photosynthesis and tetrapyrrole biosynthesis associated nuclear genes was repressed in all silenced plants. PD-mediated intercellular trafficking was changed in the silenced plants, consistent with predictions of the ONPS hypothesis. One striking observation, best exemplified by silencing the PNPase homologues, was that the degree of chlorosis of silenced leaves was not correlated with the capacity for intercellular trafficking. Finally, we measured the distribution of PD in silenced leaves and found that intercellular trafficking was positively correlated with the numbers of PD. Together, these results not only provide further support for ONPS but also point to a genetic mechanism for PD formation, clarifying a longstanding question about PD and intercellular trafficking.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Retrograde signalling from endosymbiotic organelles'.

Keywords: chloroplast, gun, intercellular trafficking, plasmodesmata, retrograde signalling, tetrapyrrole

1. Introduction

Cell-to-cell communication in plants occurs via microscopic but complex pores known as plasmodesmata (PD). PD are membrane-lined cytoplasmic passages that allow movement of metabolites and signalling molecules between neighbouring plant cells. They are, therefore, essential for plant growth, development and defence [1]. They are also conduits for the trafficking of carbon fixed by photosynthesis (in the form of sugars) to the vasculature in source tissues and from the vasculature into sink tissues, thereby facilitating energy distribution throughout the plant [2,3]. The relatively small number of reported PD mutants underscores the importance of PD to plant growth and development. Plants have evolved a number of mechanisms to control PD function including the regulated deposition and removal of callose in the cell wall surrounding PD [4–7]. PD function also changes in response to plant hormones upon abiotic and biotic signals from the environment and to developmental programmes [8,9]. Besides callose metabolism and hormones, there is increasing evidence supporting the postulate that chloroplasts exert control over the development and function of PD.

Nuclear genes encode approximately 95% of chloroplast proteins, with the remainder encoded by the chloroplast genome. Disrupting chloroplast function leads to changes in expression of specific nuclear genes. This chloroplast-to-nucleus signalling is referred to as chloroplast retrograde signalling (CRS), [10]. Several CRS pathways and the molecules that initiate them have been identified, and the mechanistic details are under intensive investigation [11–15]. Gene expression analyses have identified a core suite of 39 genes that respond to all chloroplast-generated signals [16]. This suite includes genes that affect cell wall synthesis and/or modification, sugar transport, stress responses, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) responses. This indicates that chloroplast functional status can regulate the expression of nuclear genes including, but not limited to, photosynthesis-associated nuclear genes [17]. Several CRS pathways have been identified, and among the best characterized are those involving the genomes uncoupled (gun) mutants [15,18]. The gun2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 mutations affect proteins that participate in the tetrapyrrole biosynthetic pathway that eventually produces chlorophyll and haem [18]. GUN4 and GUN5 are part of the Mg chelatase that couples Mg to tetrapyrroles on the chlorophyll branch of the pathway [19–22]. GUN2, GUN3 and GUN6 belong to the pathway that couples protoporphyrin IX to iron, eventually producing haem and phytochromobilin [18].

Studies with the chloroplast-resident RNA helicase ISE2 have served as an entry point to further probing the chloroplast-PD relationship. ISE2 is a chloroplast DEAH-type RNA helicase critical for chloroplast RNA processing and translation, and it is conserved among green photosynthetic organisms [23,24]. Plants with reduced ISE2 expression have decreased photosynthetic capacity and defects in chloroplast development [25]. In addition, Arabidopsis ise2 mutant embryos and Nicotiana benthamiana leaves in which ISE2 was silenced by virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) had defects in intercellular trafficking and PD formation [26,27]. Deficiency in ISE2 expression also led to changes in the expression of target genes of CRS pathways as well as changes in the expression of several genes implicated in PD function, e.g. callose metabolism genes like ATBG-PPAP, and numerous genes with roles in cell wall biosynthesis or modification [25]. Based on these gene expression analyses, a relationship between chloroplasts and PD was proposed and articulated in the organelle-nucleus-PD signalling (ONPS) hypothesis [25,28]. One predicted consequence of ONPS is that it would be a mechanism by which chloroplasts could regulate carbon partitioning.

The signals that connect chloroplasts with PD function and biogenesis remain to be elucidated and this is the question investigated in this study. One challenge with examining this question is the embryonic or seedling lethality of mutants with defects in chloroplast and/or PD function [29,30]. Therefore, we adopted N. benthamiana and VIGS as a model system for assessing the acute effects of chloroplast dysfunction on PD-mediated intercellular trafficking. Expression of several genes with known roles in regulating chloroplast gene expression was knocked down and intercellular trafficking was then measured in the silenced leaves. CRS was then assessed in plants with altered intercellular trafficking. Finally, we measured the effects of CRS resulting from the silencing of the target genes on PD formation. Here, we present data suggesting that intercellular trafficking is correlated with numbers of plasmodesmal pores. We interpret these results to mean that CRS exerts influence on intercellular trafficking by controlling the formation of PD.

2. Material and methods

(a). Plant material and growth conditions

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in light carts with 16 h light (approx. 120 µmol m−2 s−1) and 8 h dark. Silencing was done on 3-week-old plants (around the time 2–4 true leaves were present). After infiltration with silencing constructs, plants were grown on the light cart for an additional two weeks until silencing of PHYTOENE DESATURASE (PDS), the positive control, could be observed and other analyses were performed. Photographs of plants were taken with a Nikon D60 camera (Nikon, Inc.).

(b). RNA extraction and complementary DNA synthesis

Wild-type or silenced N. benthamiana tissue was collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA from three independent samples was isolated using the Trizol method (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to manufacturer's instructions. RNA was DNAse treated using the DNA-free DNA removal kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using oligo-dT primers with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was used for gene cloning or quantitative-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

(c). Gene cloning and generation of recombinant virus induced gene silencing vectors

Nicotiana benthamiana gene sequences were obtained from the Sol Genomics Network Database (https://solgenomics.net) or the University of Sydney's N. benthamiana genome page (http://benthgenome.qut.edu.au/). Gene fragments were cloned by PCR and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pYL156 (pTRV-RNA2) vector [31] by restriction digestion–ligation to generate silencing constructs. The primers for cloning VIGS fragments are listed in the electronic supplementary material, table S1. The resulting plasmids were transformed into chemically competent Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Infiltrations for VIGS were done according to published protocols [32].

(d). Carotenoid and chlorophyll determination

Total carotenoids x + c (xanthophylls and carotenes), chlorophyll a and b were extracted with 100% acetone. The extracts were centrifuged at room temperature for 5 min at 500g and supernatants were used to measure the absorption at 661.6 nm, 644.8 nm and 470 nm. The level of total carotenoids x + c, chlorophyll a and b were determined following the equation in [33].

(e). Measuring intercellular trafficking by movement assay

Movement assays to measure intercellular trafficking were performed as described previously [34]. Briefly, silenced leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying a binary construct for expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (p35S:GFP) at optical density (OD)600 = 0.0001, and then imaged approximately 48 h later. z-stacks of foci of GFP were collected on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope with a White Light Laser (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Groove, IL) with a 10× lens and z-stacks were reconstructed and analysed in ImageJ [35,36]. For analysis of movement, the number of layers of cells in the epidermis surrounding the original cell expressing GFP was scored and the highest number was recorded. Movement assays were performed for at least three biological replicates and each replicate included at least 10 foci. Statistical significance was measured with the Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05) compared to non-silenced wild-type + tobacco rattle virus (WT+TRV) samples.

(f). Optimization of primers and measuring transcript abundance by quantitative-polymerase chain reaction

All qPCR primers were designed using the Primer BLAST tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Mfold ([37], web server http://www.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/) was used to avoid secondary structures in the amplicons. To optimize the qPCR primers, the full-length target genes were amplified from cDNA of wild-type N. benthamiana (electronic supplementary material, table S2) and then cloned into the linearized pMiniT 2.0 vector using a NEB PCR Cloning kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA) followed by transformation of competent Escherichia coli. Plasmids were isolated using miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD) followed by sequencing for confirmation of successful cloning. CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad, v. 1.6) was used to generate a standard curve to calculate amplification efficiency from five dilution points of isolated plasmid for three technical replicates. Primer pairs with efficiency between 90 and 110% were selected for further use (electronic supplementary material, table S3).

To measure the expression of photosynthesis associated nuclear genes and other genes in silenced plants, cDNA from silenced leaves was diluted 1 : 5 with nuclease-free water. qPCR was performed using the LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix and a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with the following thermal cycling programme: 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 59°C for 10 s and 72°C for 20 s. The raw data generated were analysed by calculating cycle threshold values and normalized to the expression of GAPDH and EF1α as reference genes and also with wild-type.

(g). Measuring plasmodesmata density

(i). PDLP1 expression for measuring pitfield distribution

Arabidopsis PDLP1 fused to GFP (p35S:PDLP1-GFP) was transiently expressed in leaves of silenced and non-silenced control N. benthamiana plants via Agrobacterium infiltration at OD600 = 0.001. Images were collected 72 h post infiltration with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope with a White Light Laser (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Groove, IL, USA) using a 25× water emersion objective with 4.00× optical zoom. All images were collected with the same laser power and gain settings, and 15 µm z-stacks were collected of epidermal cells expressing PDLP1-GFP at a step-size of 1 µm. A total of 60 stacks were collected across three biological replicates for the control and each of the silenced plants.

(ii). Image analysis for measuring pitfield distribution

All image analysis was performed using ImageJ. Maximum intensity projections were generated for each the z-stacks collected. Cell wall lengths were measured by tracing the cell wall in the field of view. For quantification of the total number of GFP punctae in the image, images were converted to 8-bit images and inverted. The brightness and contrast were adjusted in order to ensure that all pitfields were clearly defined. Binary images were generated by adjusting the threshold of intensity. The Particle Analyzer function in ImageJ was used to count the total number of punctae in the image. For measuring pitfield area and fluorescence intensity, a copy of the inverted 8-bit maximum projection was generated to use as a reference image for measurements. A binary image was generated from the original maximum projection by setting the threshold using the auto-threshold function. The particle analyser was used to measure the area and the integrated density (IntDen, i.e. the average intensity of all the pixels x the area) of each GFP punctum in the unedited reference image for the regions defined in the binary image.

(iii). Quantifying the plasmodesmata density score

To assess the total number of PD within each field of view, the following calculation was performed:

This measure generates a single value that accounts for differences in number of PDLP1-GFP punctae, their size, and their fluorescence intensity. Statistical significance was measured using the Mann–Whitney U-test (p < 0.0001) compared to non-silenced WT+TRV controls.

3. Results

(a). Silencing genes for chloroplast gene expression produces varying degrees of chlorosis

Reduced expression of the genes encoding the RNA helicase ISE2 or the plastid ribosomal protein uL15c led to increased intercellular trafficking via PD [27,38]. ISE2 also interacted with numerous proteins involved in chloroplast gene expression [38]. In order to test whether chloroplast gene expression was broadly involved in ONPS and regulating PD, we silenced six genes encoding proteins found to interact with ISE2 or be important for expression of the plastid genome and then monitored intercellular trafficking via PD in silenced tissues. For this, we used VIGS with vectors derived from the TRV in N. benthamiana [31,39]. The silenced genes were those encoding RNA helicases RH22 [40], RH39 [41] or RH3 [42], a gene encoding a pentratricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein reported to be important for translation in maize plastids and found to interact with ISE2 (here called IPI1) [38,43], the RNA surveillance factor RNase J [44], and the RNA maturation and degradation factor PNPase [45]. In all experiments, wild-type plants infected with TRV but with no silencing were used as the negative control, and VIGS of PDS was used as a positive control for silencing. The inclusion of ISE2 in the silencing experiments also served as an internal control because the behaviour of ISE2-silenced plants has been well characterized.

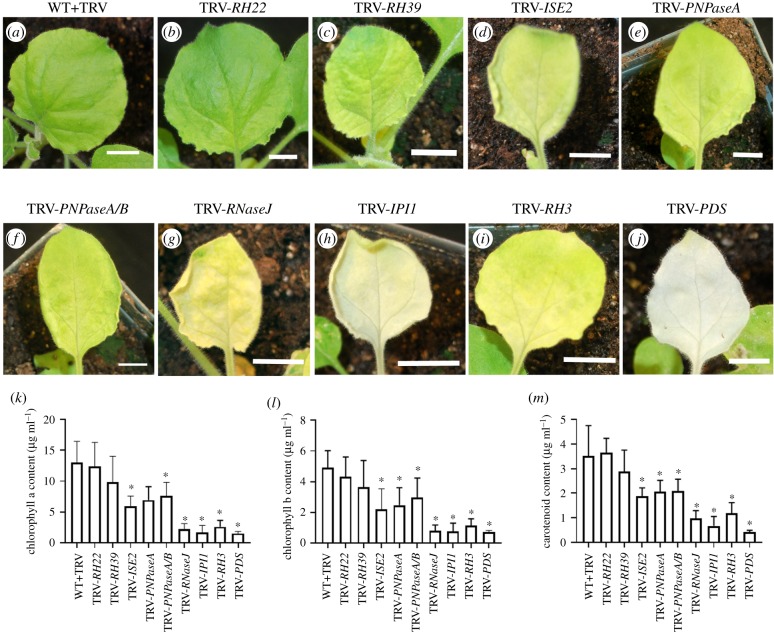

Silencing of the target genes was confirmed by quantitative real time-PCR and gene expression in all cases was reduced by at least 87% (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Knockdown of RH22 expression produced plants that were almost indistinguishable from the non-silenced WT+TRV control plants in both appearance and photosynthetic pigment content (figure 1a–b,k–m). Silencing RH39 caused mild chlorosis in newly emerged leaves (figure 1c,k–m) while silencing a single or both PNPase homologues led to more severe yellowing, similar to that observed with silencing ISE2 (figure 1d–f,k–m). Plants with reduced expression of RNaseJ, IPI1 or RH3 yielded severe chlorotic phenotypes and reduction in photosynthetic pigment contents that were similar to those observed in plants where PDS was silenced (figure 1g–m). Despite chlorosis, the silenced plants continued to grow and they eventually matured and set seed (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of silenced plants and their photosynthetic pigment content. (a–j) Representative leaves from silenced plants. Silenced gene is shown above figure. WT N. benthamiana infected with TRV virus only (a). (b–k) Plants with silenced RH22 (b), RH39 (c), ISE2 (d), PNPaseA (e), PNPaseA/B (f), RNaseJ (g), IPI1 (h), RH3 (i), and PDS (j). Silencing of PDS results in severely chlorotic tissue. Chlorophyll a and b content of silenced plants (k,l), and total carotenoid content of silenced plants (m). Asterisk denotes statistical significance, Student's t-test p < 0.05.

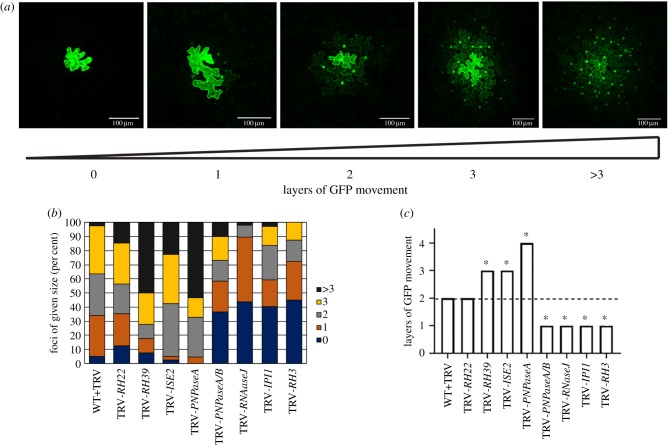

(b). Intercellular trafficking changes in plants with defective chloroplast RNA processing

Intercellular trafficking via PD was measured in silenced leaves. For this, we used movement of a GFP probe from a single cell into adjacent, contiguous layers of epidermal cells to report on PD function [27,34,46]. In this assay, GFP travels variable distances, generating foci of GFP of different sizes (figure 2a). Because of the inherent variation in the sizes of foci in any sample, movement data are presented in two ways. Figure 2b presents the complete distribution of foci sizes observed for a sample, while figure 2c presents a quantification of the average (median) size of foci for a given sample. In RH22-silenced leaves, there was no difference in the average size of foci compared to those observed in the non-silenced WT+TRV control leaves (figure 2c). In leaves where RH39, ISE2 or PNPaseA were silenced and chlorosis was more severe, there was an increase in the size of GFP foci and hence, intercellular trafficking (figure 2b,c). Strikingly, when RNAseJ, IPI1 or RH3 was silenced and leaves exhibited severe chlorosis (figure 1), there were large decreases in the size of GFP foci reflected in the increase in the proportion of foci that were restricted to one cell layer, indicating reduced intercellular trafficking (figure 2). Leaves in which both PNPase genes were silenced (TRV-PNPaseA/B) also showed a large decrease in GFP foci sizes, in striking contrast to the results from silencing only PNPaseA. It should be noted that there were no differences in the chlorosis or the photosynthetic pigment content between the PNPaseA or PNPaseA/B-silenced plants (figure 1). These data support previous observations that chloroplast function modulates intercellular trafficking. However, they also reveal a more complex relationship in which the degree of chloroplast (dys)function does not exclusively determine changes to intercellular trafficking.

Figure 2.

Measurement of PD-mediated intercellular trafficking in silenced plants. PD-mediated trafficking was measured by counting the layers of epidermal cells to which GFP spread. At least 10 foci were scored for each of three biological replicates. (a) Representative images depicting GFP trafficking between contiguous layers of epidermal cells. The presence of GFP in cell nuclei was used to determine the presence of GFP in a cell. The cell labelled ‘0' showed expression of GFP in the primary transformed cell but no GFP was seen in surrounding epidermal layers. In the image labelled ‘1', GFP expression was observed in the primary transformed cell and in the nuclei of cells immediately adjacent to the transformed cell only. For subsequent images, the number below the image corresponds to the number of layers away from the primary transformed cell that showed GFP accumulation in the nucleus. Scale bar = 100 µm. (b) Qualitative representation of GFP trafficking data showing the distribution of foci sizes observed for each silenced plant. (c) Layers were assigned values (0 layers = 0, 1 layer = 1, 2 layers = 2, 3 layers = 3, greater than 3 layers = 4) and the median value is shown. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann–Whitney U-test. *p < 0.05.

(c). Chloroplast retrograde signalling is triggered in plants with defective chloroplast gene expression

ONPS predicts that CRS is a likely mechanism for regulating PD function [25]. To explicitly test this hypothesis, the expression of marker genes known to respond to CRS was measured in silenced plants with altered PD-mediated intercellular trafficking. GOLDEN2-LIKE1 (GLK1) is a transcription factor that is important for chloroplast development [47] and GLK1 expression is suppressed when CRS is activated [48]. We, therefore, first measured GLK1 transcript levels in silenced plants. In six of the eight silenced lines with defective intercellular trafficking, GLK1 transcript levels were reduced (figure 3). Next, Lhcb genes encoding the antennae proteins of the photosystem-associated light-harvesting complexes and RBCS1A encoding one of the isoforms of the rubisco small subunit were selected as likely conserved targets of retrograde signalling in N. benthamiana. In most of the silenced lines, expression of Lhcb1.1 and Lhcb2.1 was suppressed, consistent with those tissues undergoing CRS. However, RBCS1A suppression of its expression was less common, with only RH22- or PNPaseA/B-silenced lines showing statistically significant reductions in expression (figure 3). This suggests that RBCS1A may not be responsive to CRS in N. benthamiana. Nonetheless, together these data demonstrate CRS occurring in silenced plants with altered PD-mediated intercellular trafficking.

Figure 3.

Silencing of genes involved in chloroplast gene expression results in altered expression of CRS target genes. Relative normalized expression of GLK1, LHCB1.2, LHCB2.1, RBCS1A and XTH5 of N. benthamiana in non-silenced TRV-infected controls (WT+TRV) versus (a) TRV-RH22, (b) TRV-RH39, (c) TRV-ISE2, (d) TRV-PNPaseA, (e) TRV-PNPaseA/B, (f) TRV-RNaseJ, (g) TRV-IPI1, and (h) TRV-RH3 silenced plants. Expression was normalized against non-silenced TRV-infected controls and relative expression was calculated using GAPDH and EF1α as reference genes. Data represent mean (± s.e.) from three technical replicates of a representative biological replicate. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test. *p < 0.05. (i) Heatmap showing expression levels of CRS marker genes (GLK1, LHCB1.2, LHCB2.1, RBCS1A and XTH5) in silenced plants. The rows represent CRS marker genes and the columns represent silenced genes. Scale is shown on right.

To further examine possible pathways for CRS that could be involved in ONPS, we also measured transcript levels of XYLOGLUCAN ENDOTRANSGLUCOSYLASE-HYDROLASE5 (XTH5), a gene whose expression is regulated by the HY5 transcription factor [49]. The XTH family is a large group of enzymes involved in cell wall remodelling [50]. HY5 is an important regulator of chloroplast development and it is emerging as an important hub for integrating chloroplast retrograde signals to control plant development [51]. In most silenced plants transcript levels of XTH5 were significantly different from those in the corresponding TRV-infected non-silenced controls (figure 3). This suggests that CRS modulated by HY5 may be involved in ONPS. However, no clear correlation between XTH5 expression and changes in PD-trafficking capacity were observed. While NbXTH5 expression was statistically significantly decreased in RH22- and RH39-silenced plants that had increased intercellular trafficking, its expression was statistically significantly increased in ISE2- or PNPaseA–silenced plants which also had enhanced intercellular trafficking (figure 3).

(d). Tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes have altered expression in silenced plants with changes in intercellular trafficking

Tetrapyrrole biosynthesis and use is universal among photosynthesizing organisms, and tetrapyrrole metabolism is important for CRS [52]. We, therefore, examined the involvement of genes involved in tetrapyrrole biosynthesis with a focus on the GENOMES UNCOUPLED (GUN) genes, known components of retrograde signalling, and HEMA1, required for the first, rate-limiting step in tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in ONPS. While HEMA1 expression was altered in all of the silenced lines, no clear correlation with altered intercellular trafficking was observed. Similarly, expression of GUN2–5 was altered in all silenced plants compared to non-silenced controls (figure 4). GUN2 transcript levels were mostly unchanged in silenced plants except for a reduction in RH22-silenced plants and a small increase in RH39-silenced plants. In comparison, GUN3 transcript levels were significantly increased in all silenced lines except TRV-RH22. GUN2 (HO1) and GUN3 (HY2) both act in the haem branch of the tetrapyrrole pathway, suggesting that production of haemoproteins could be upregulated in those silenced lines with increased GUN3 expression. GUN4 encodes the regulatory subunit of the Mg-chelatase complex and GUN5 (CHLH) encodes the catalytic subunit of the complex [20]. Silencing of genes related to chloroplast gene expression led to repressed expression of GUN4. By contrast, GUN5 transcripts accumulated in all silenced lines except for TRV-IPI1. These results indicate that haem and tetrapyrrole metabolism is disrupted in silenced plants, consistent with the chlorosis of silenced leaves. Moreover, they demonstrate that tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes respond strongly to defects in chloroplast gene expression and to chloroplast-derived signals.

Figure 4.

Silencing of genes involved in chloroplast gene expression results in changes in expression of genes of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway. qPCR analysis of expression of HEMA1, GUN2, 3, 4 and 5 in non-silenced TRV-infected controls (WT+TRV) and (a) TRV-RH22, (b) TRV-RH39, (c) TRV-ISE2, (d) TRV-PNPaseA, (e) TRV-PNPaseA/B, (f) TRV-RNaseJ, (g) TRV-IPI1, and (h) TRV-RH3 silenced plants. GAPDH and EF1α were used as reference genes for calculating the relative expression and normalized with TRV infected wild-type (WT+TRV). The data are presented as the mean (±s.e.) from three technical replicates of a representative biological replicate. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test. *p < 0.05. (i) Heatmap showing expression levels of HEMA1 and the GUN genes in silenced plants. Scale is on right.

(e). Plasmodesmata density is altered in plants with defective chloroplast gene expression

The silencing of genes important for chloroplast gene expression resulted in defects in intercellular trafficking (figure 2). In ISE2-silenced plants, defects in intercellular trafficking were associated with changes in PD [27]. We, therefore, tested whether changes in PD were also involved in the changes to intercellular trafficking observed in the silenced plants. For this, Arabidopsis PLASMODESMATA-LOCATED PROTEIN1 (PDLP1-GFP), a general marker for PD [53], was expressed in leaves equivalent to those used in the trafficking assays. Using confocal fluorescence microscopy, we monitored the appearance of GFP punctae in cell walls. PD are nanopores with an average diameter of 30 nm, so for our analysis we assumed that the fluorescent foci we observed were owing to clusters of PD in the cell wall, called pitfields [54]. Direct observation by microscopy revealed striking changes in the patterns of pitfields compared to those in non-silenced TRV-infected controls. In some silenced plants there were more, larger punctae that had greater fluorescence intensity (measured under the same imaging settings) than in control plants, exemplified by TRV-PNPaseA (figure 4a,b). In other plants, as shown for TRV-IPI1, the GFP punctae were much less abundant and had weaker fluorescence intensity compared to the control plants (figure 4c). Images of cells were collected as z-stacks and then the maximum intensity projections were used to measure the number, size and fluorescence intensity of GFP punctae in a field of view (figure 4d). Based on these parameters, a ‘PD density score' was developed to quantitatively describe these observations (see Material and methods). In RH22-, RH39-, ISE2- and PNPaseA-silenced plants, the average PD density was higher than that of non-silenced control plants and in all cases, this difference was statistically significant (figure 4e). Note that, except for RH22, silencing these genes led to increased intercellular trafficking of GFP (figure 2). By contrast, in epidermal cells in leaves where RNaseJ, IPI1 or RH3 were silenced, there were drastic, statistically significant decreases in PD density (figure 4e). Silencing of those genes had led to decreased intercellular trafficking (figure 2). Relative to the non-silenced control, silencing both PNPase homologues with the TRV-PNPaseA/B construct did not affect the PD density (figure 4e), although it led to decreased intercellular trafficking (figure 2). Comparing intercellular trafficking to PD density revealed a positive correlation between PD density and intercellular trafficking (figure 4f). However, the data for TRV-RH22 and TRV-PNPaseA/B do not fit the curve suggesting that other factors beyond PD density may contribute to the changes observed in intercellular trafficking.

4. Discussion

In this study, we took a reverse genetics approach to investigating the relationship between chloroplasts and PD in coordinating intercellular trafficking, called ONPS. Expression of genes encoding factors needed for chloroplast gene expression was knocked down by VIGS, resulting in varying degrees of chlorosis in the silenced plants. Movement assays in epidermal cells of silenced leaves revealed that in seven of the eight samples examined, perturbing chloroplast gene expression disrupted intercellular trafficking (figure 2). The use of reverse genetics allowed us to sidestep one of the main challenges that encumbers investigations of PD. Mutants with defects in PD are scarce, probably owing to their embryonic and seedling lethality [30,55]. Similarly, Arabidopsis rh22, rh3, rh39, pnpase, ipi1 and rnase j mutants all display embryonic or seedling lethality [40–42,56–58]. It would, therefore, be difficult to examine the roles of these genes in other aspects of plant development. The use of VIGS in N. benthamiana plants provides a relatively straightforward system to reduce gene expression and measure effects on PD function. Another advantage of N. benthamiana and VIGS is that it allows the acute effects of perturbation of gene expression to be assessed. Plants are wild-type until initiation of VIGS, and have presumably induced relatively few responses to cope with the loss of gene function as they would in a true genetic mutant. Thus, N. benthamiana and VIGS represent a powerful new system for probing CRS and ONPS.

Using quantitative measurement of transcript levels of known markers for CRS (Lhcb and RBCS1A genes), we showed that CRS was altered in the silenced plants compared to non-silenced controls (figure 3). Changes in chloroplast gene expression are well known to modify CRS and alter expression of nuclear genes [14,59]. ISE2 is involved in multiple aspects of chloroplast RNA processing including group II intron splicing, rRNA processing and C-to-U editing [23]. RH3, RH22 and RH39, are required for rRNA processing in chloroplasts with RH3 having additional roles in splicing group II introns [40–42]. The maize homologue of IPI1 is PPR103, and it is required for processing rpl16 mRNAs and ribosome accumulation in maize [43]. RNaseJ is necessary to prevent the overaccumulation of chloroplast antisense RNAs, thereby ensuring correct expression of the chloroplast genome [44,60]. Chloroplast PNPase is needed for multiple steps of RNA processing including correct 3′end maturation of rRNA and mRNA, RNA degradation, intron processing and non-coding RNAs [45,60]. In plants where any of these genes is silenced, it is expected that chloroplast gene expression would be altered, leading to the production of chloroplast molecules that would act as a retrograde signal to influence expression of the nuclear genome. We hypothesize that in our system, silencing each gene would produce a distinct perturbation of chloroplast gene expression and function, leading to unique signals or signal signatures that in turn has a specific effect on expression of genes important for PD formation or function. This hypothesis is borne out by the unique patterns of nuclear gene expression observed in the silenced plants (figures 3 and 4).

In the silenced plants, changes in expression of genes in the tetrapyrrole synthesis pathway were observed, although only the reduced expression of GUN4 was common to all silenced plants (figure 4). These changes in tetrapyrrole-related gene expression are consistent with the chlorosis of the silenced plants. Further, they are also similar to changes in gene expression analysis revealed by tiling microarray in ise2 embryos. The microarray studies showed that numerous genes associated with tetrapyrrole metabolism had altered expression in the mutant embryos including GUN2, GUN5 and GUN6 [25]. Disruption of the GUN tetrapyrrole-associated genes led to the accumulation of intermediates that are known mediators of CRS [61]. While tetrapyrroles are candidate signals for ONPS, other retrograde signals cannot be ruled out. Chloroplast-generated ROS and redox state have been shown to regulate PD-mediated intercellular trafficking [62,63], and they are also known to act as retrograde signals [12]. Investigating other CRS pathways involved in ONPS in this system will be a goal of future investigations.

Exogenous application of oxidizing or reducing agents to plant samples was shown to influence PD-mediated intercellular trafficking [64]. Interestingly, low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide increased PD-mediated trafficking in Arabidopsis roots, while at higher concentrations trafficking was inhibited. Thus, it seems that mild stress induces one PD response while more, or a different stress, can induce a distinct PD response. The results from the silencing of the PNPase homologues support the notion that there is complex regulation of PD responses to signals. The PNPase genes are highly similar, encoding proteins with 97% identity (electronic supplemental material, figure S3). When only PNPaseA was silenced, the plants displayed chlorosis and there was greatly increased PD-mediated intercellular trafficking (figure 2). When both genes were silenced, the plants displayed the same degree of chlorosis—as when only PNPaseA was silenced—but there was a striking change in PD function. Silencing both homologues of PNPase drastically decreased intercellular trafficking (figure 2). While the results from the other silenced plants suggest that degree of chlorosis is predictive for PD, the results from PNPase clearly argue against this. Indeed, when ISE1, a gene encoding a mitochondrial DEAD-box RNA helicase, was silenced in parallel to ISE2, the ISE1-silenced plants had milder chlorosis than ISE2-silenced plants but had a larger increase in intercellular trafficking between epidermal cells than did ISE2-silenced plants [27].

Interestingly, PNPaseA-silenced leaves contained increased PD density while PNPaseA/B-silenced leaves showed no difference in PD density relative to the non-silenced controls (figure 5). The increased PD density and intercellular trafficking observed in PNPaseA-silenced plants agree with the general trend observed for the other silenced lines (figure 5e) and support a simple model in which the increased cell-to-cell diffusion of free GFP is facilitated by having more PD pores. The results from PNPaseA/B confound this simple model, and suggest that it is not only the availability of PD pores that accounts for intercellular trafficking. Similarly, RH22-silenced leaves had no change in intercellular trafficking relative to the controls but showed a marked increase in PD density (figure 5e). Previous analysis of ISE2-silenced plants and ise2 mutant embryos revealed increased occurrence of twinned and branched PD along with increased intercellular trafficking, suggesting that the formation of secondary (complex) PD facilitates increased cell-to-cell trafficking [27].

Figure 5.

Quantification of PD density in silenced plants. PD in pitfields were labelled with the general PD marker PDLP1-GFP. Representative maximum projections of fields of view showing PDLP1-GFP-labelled pitfields in (a) WT+TRV, (b) TRV-PNPaseA (increased number of pitfields), and (c) TRV-IPI1 (decreased numbers of pitfields) plants. (d) Individual images (confocal planes 3–14 of a confocal stack) from z-stacks used to generate maximum projections (MP) showing the distribution of pitfields in the z-axis. Images correspond to the region outlined in white in (a). Scale bar = 10 µm. (e) PD density scores were calculated for each image from three biological replicates (rep. 1 (blue squares), rep. 2 (yellow circles) and rep. 3 (red diamonds). See Material and methods for more details. Statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney U-test. *p < 0.0001. (f) Linear regression curve showing the positive correlation of PD density score with layers of GFP movement. The average PD density score and the median layers of movement across the three biological replicates were used to generate the graph.

Often overlooked in discussions of PD is their variety and apparent subfunctionalization. Primary PD form during cytokinesis when strands of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are trapped in the nascent cell wall while secondary PD form de novo across existing cell walls in the absence of cytokinesis [9]. In mature tissues, PD are more elaborate with branching channels that may contain large central cavities compared to the simpler linear pores that are often observed in developing tissues. This change in structure may be associated with changes in their trafficking capacities. Simple PD in sink leaves were reported to allow trafficking of larger molecules than do the branched PD of source leaves [3]. The PD marker used in this study, PDLP1-GFP, localizes to all PD and does not distinguish between simplex and more complex PD in the manner of other markers, e.g. MP17-GFP derived from the potato leafroll virus [53,65]. Thus, the possibility that silencing different chloroplast-related genes resulted in the formation of different classes of PD (primary versus secondary, and simple versus branched) with distinct trafficking properties cannot be ruled out. Taken together, our results can be integrated into a model where during leaf development CRS regulates expression of PD associated nuclear genes (PDANGs) to control the formation of secondary PD that would complement the existing primary PD generated during cell division, allowing the flux of carbon into or out of cells to match the developmental state of chloroplasts (figure 6a). When chloroplast development and CRS are disrupted, the regulation of PDANGs expression is disturbed and, depending on the strength and identity of the signalling molecules regulating gene expression, the number of secondary PD formed exceeds or falls short of normal levels, resulting in altered intercellular trafficking (figure 6b). Further examination of PD ultrastructure in our system to delineate the contributions of simple or complex and PD of primary or secondary origins to intercellular trafficking is therefore warranted. Such studies would address longstanding questions regarding the function of different classes of PD. However, studies on ONPS are constrained by our limited understanding of the genetic underpinnings of PD formation and function. Further elucidation of ONPS will depend on the identification of PDANGs whose expression in response to CRS can be validated and used as reliable markers for chloroplast-nuclear communication for PD regulation.

Figure 6.

Model for the control of formation of secondary PD by CRS. Primary PD (1° PD) are formed during cell division while secondary PD (2° PD) arise in the absence of cell division. Under normal control conditions or in WT plants with normal RNA processing (a), CRS (black arrow) regulates the expression of PDANGs that are involved in the formation of secondary PD. Disruption of chloroplast RNA processing and gene expression, as in the silenced plants used in this study, leads to defects in chloroplast development and function, causing altered CRS (red arrow) which results in changes in the expression of PDANGs (b). These changes result in increased (I) or decreased (II) secondary PD formation.

5. Conclusion

Our findings support the role of chloroplasts in regulating intercellular trafficking via PD. The tetrapyrrole biosynthetic pathway has been identified in this study as one potential source of CRS that mediate changes in PD-mediated intercellular trafficking. However, other CRS may also be involved in communicating the physiological state of the chloroplasts to the nucleus to then modulate expression of genes important for PD function. A positive correlation between PD density and intercellular trafficking was measured, suggesting that the presence of more pores can allow increased diffusion of molecules from one cell to another. However, the results also suggest that other factors in addition to simple numbers of PD are important for determining intercellular flux and these will be the subjects of future investigation. The system used in these studies, consisting of VIGS in N. benthamiana, is amenable to the study of chloroplast- and/or PD-related genes whose loss results in lethality, and this system should prove useful for further studies of ONPS and PD formation and function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Vitaly Ganusov for useful discussions and suggestions.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

E.E.G. and T.M.B.-S. conceived and designed the experiments; E.E.G. B.C.R, J.C.F., M.F.A. and K.M.F. performed the experiments; T.N.M., K.P. and C.K. contributed novel reagents; B.C.R, J.C.F., M.F.A and A.F.S. analysed the data; E.E.G. and T.M.B.-S. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation through grant nos IOS 1456761 and MCB 1846245 to T.M.B.-S

References

- 1.Lucas WJ, Lee JY. 2004. Plasmodesmata as a supracellular control network in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 712–726. ( 10.1038/nrm1470) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patrick JW. 2013. Does Don Fisher's high-pressure manifold model account for phloem transport and resource partitioning? Front. Plant Sci. 4, 184 ( 10.3389/fpls.2013.00184) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oparka KJ, et al. 1999. Simple, but not branched, plasmodesmata allow the nonspecific trafficking of proteins in developing tobacco leaves. Cell 97, 743–754. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80786-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu SW, Kumar R, Iswanto ABB, Kim JY. 2018. Callose balancing at plasmodesmata. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 5325–5339. ( 10.1093/jxb/ery317) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amsbury S, Kirk P, Benitez-Alfonso Y. 2017. Emerging models on the regulation of intercellular transport by plasmodesmata-associated callose. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 105–115. ( 10.1093/jxb/erx337) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Storme N, Geelen D. 2014. Callose homeostasis at plasmodesmata: molecular regulators and developmental relevance. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 138 ( 10.3389/fpls.2014.00138) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zavaliev R, Ueki S, Citovsky V, Epel BL. 2011. Biology of callose (beta-1,3-glucan) turnover at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 248, 117–130. ( 10.1007/s00709-010-0247-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sager RE, Lee JY. 2018. Plasmodesmata at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs209346 ( 10.1242/jcs.209346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burch-Smith TM, Stonebloom S, Xu M, Zambryski PC. 2011. Plasmodesmata during development: re-examination of the importance of primary, secondary, and branched plasmodesmata structure versus function. Protoplasma 248, 61–74. ( 10.1007/s00709-010-0252-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pogson BJ, Woo NS, Forster B, Small ID. 2008. Plastid signalling to the nucleus and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 602–609. ( 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan KX, Phua SY, Crisp P, McQuinn R, Pogson BJ. 2016. Learning the languages of the chloroplast: retrograde signaling and beyond. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67, 25–53. ( 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111854) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobik K, Burch-Smith TM. 2015. Chloroplast signaling within, between and beyond cells. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 781 ( 10.3389/fpls.2015.00781) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gollan PJ, Tikkanen M, Aro EM. 2015. Photosynthetic light reactions: integral to chloroplast retrograde signalling. Curr. Opin Plant Biol. 27, 180–191. ( 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.07.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleine T, Leister D. 2016. Retrograde signaling: organelles go networking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1313–1325. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunkard JO, Burch-Smith TM. 2018. Ties that bind: the integration of plastid signalling pathways in plant cell metabolism. Essays Biochem. 62, 95–107. ( 10.1042/EBC20170011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasser C, et al. 2014. Meta-analysis of retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a core module of genes embedded in complex cellular signaling networks. Mol. Plant 7, 1167–1190. ( 10.1093/mp/ssu042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surpin M, Larkin RM, Chory J. 2002. Signal transduction between the chloroplast and the nucleus. Plant Cell 14, S327–S338. ( 10.1105/tpc.010446) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larkin RM. 2016. Tetrapyrrole signaling in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1586 ( 10.3389/fpls.2016.01586) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin RM, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Chory J. 2003. GUN4, a regulator of chlorophyll synthesis and intracellular signaling. Science 299, 902–906. ( 10.1126/science.1079978) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adhikari ND, Froehlich JE, Strand DD, Buck SM, Kramer DM, Larkin RM. 2011. GUN4-porphyrin complexes bind the ChlH/GUN5 subunit of Mg-Chelatase and promote chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 1449–1467. ( 10.1105/tpc.110.082503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voigt C, Oster U, Bornke F, Jahns P, Dietz KJ, Leister D, Kleine T. 2010. In-depth analysis of the distinctive effects of norflurazon implies that tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, organellar gene expression and ABA cooperate in the GUN-type of plastid signalling. Physiol. Plant. 138, 503–519. ( 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01343.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi K, Masuda T. 2016. Transcriptional regulation of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1811 ( 10.3389/fpls.2016.01811) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bobik K, McCray TN, Ernest B, Fernandez JC, Howell KA, Lane T, Staton M, Burch-Smith TM. 2017. The chloroplast RNA helicase ISE2 is required for multiple chloroplast RNA processing steps in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 91, 114–131. ( 10.1111/tpj.13550) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlotto N, Wirth S, Furman N, Ferreyra Solari N, Ariel F, Crespi M, Kobayashi K. 2016. The chloroplastic DEVH-box RNA helicase INCREASED SIZE EXCLUSION LIMIT 2 involved in plasmodesmata regulation is required for group II intron splicing. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 165–173. ( 10.1111/pce.12603) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burch-Smith TM, Brunkard JO, Choi YG, Zambryski PC. 2011. Organelle-nucleus cross-talk regulates plant intercellular communication via plasmodesmata. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1451–E1460. ( 10.1073/pnas.1117226108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi K, Otegui MS, Krishnakumar S, Mindrinos M, Zambryski P. 2007. INCREASED SIZE EXCLUSION LIMIT 2 encodes a putative DEVH box RNA helicase involved in plasmodesmata function during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Plant Cell 19, 1885–1897. ( 10.1105/tpc.106.045666) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burch-Smith TM, Zambryski PC. 2010. Loss of INCREASED SIZE EXCLUSION LIMIT (ISE)1 or ISE2 increases the formation of secondary plasmodesmata. Curr. Biol. 20, 989–993. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.064) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burch-Smith TM, Zambryski PC. 2012. Plasmodesmata paradigm shift: regulation from without versus within. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 239–260. ( 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105453) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryant N, Lloyd J, Sweeney C, Myouga F, Meinke D. 2011. Identification of nuclear genes encoding chloroplast-localized proteins required for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 155, 1678–1689. ( 10.1104/pp.110.168120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim I, Hempel FD, Sha K, Pfluger J, Zambryski PC. 2002. Identification of a developmental transition in plasmodesmatal function during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 129, 1261–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Schiff M, Marathe R, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2002. Tobacco Rar1, EDS1 and NPR1/NIM1 like genes are required for N-mediated resistance to tobacco mosaic virus. Plant J. 30, 415–429. ( 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01297.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Burch-Smith T, Schiff M, Feng S, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2004. Molecular chaperone Hsp90 associates with resistance protein N and its signaling proteins SGT1 and Rar1 to modulate an innate immune response in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2101–2108. ( 10.1074/jbc.M310029200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtenthaler HK. 1987. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic membranes. Methods Enzymol. 148, 350–382. ( 10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunkard JO, Burch-Smith TM, Runkel AM, Zambryski P. 2015. Investigating plasmodesmata genetics with virus-induced gene silencing and an agrobacterium-mediated GFP movement assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 1217, 185–198. ( 10.1007/978-1-4939-1523-1_13) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindelin J, et al. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. ( 10.1038/nmeth.2089) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415. ( 10.1093/nar/gkg595) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bobik K, Fernandez JC, Hardin SR, Ernest B, Ganusova EE, Staton ME, Burch-Smith TM. 2019. The essential chloroplast ribosomal protein uL15c interacts with the chloroplast RNA helicase ISE2 and affects intercellular trafficking through plasmodesmata. New Phytol. 221, 850–865. ( 10.1111/nph.15427) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burch-Smith TM, Anderson JC, Martin GB, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2004. Applications and advantages of virus-induced gene silencing for gene function studies in plants. Plant J. 39, 734–746. ( 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02158.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chi W, He B, Mao J, Li Q, Ma J, Ji D, Zou M, Zhang L. 2012. The function of RH22, a DEAD RNA helicase, in the biogenesis of the 50S ribosomal subunits of Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 158, 693–707. ( 10.1104/pp.111.186775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura K, Ashida H, Ogawa T, Yokota A. 2010. A DEAD box protein is required for formation of a hidden break in Arabidopsis chloroplast 23S rRNA. Plant J. 63, 766–777. ( 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04276.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asakura Y, Galarneau E, Watkins KP, Barkan A, van Wijk KJ. 2012. Chloroplast RH3 DEAD box RNA helicases in maize and Arabidopsis function in splicing of specific group II introns and affect chloroplast ribosome biogenesis. Plant Physiol. 159, 961–974. ( 10.1104/pp.112.197525) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammani K, Takenaka M, Miranda R, Barkan A. 2016. A PPR protein in the PLS subfamily stabilizes the 5'-end of processed rpl16 mRNAs in maize chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 4278–4288. ( 10.1093/nar/gkw270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharwood RE, Halpert M, Luro S, Schuster G, Stern DB. 2011. Chloroplast RNase J compensates for inefficient transcription termination by removal of antisense RNA. RNA 17, 2165–2176. ( 10.1261/rna.028043.111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Germain A, Herlich S, Larom S, Kim SH, Schuster G, Stern DB. 2011. Mutational analysis of Arabidopsis chloroplast polynucleotide phosphorylase reveals roles for both RNase PH core domains in polyadenylation, RNA 3'-end maturation and intron degradation. Plant J. 67, 381–394. ( 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04601.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ganusova EE, Rice JH, Carlew TS, Patel A, Perrodin-Njoku E, Hewezi T, Burch-Smith TM. 2017. Altered expression of a chloroplast protein affects the outcome of virus and nematode infection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 30, 478–488. ( 10.1094/MPMI-02-17-0031-R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fitter DW, Martin DJ, Copley MJ, Scotland RW, Langdale JA. 2002. GLK gene pairs regulate chloroplast development in diverse plant species. Plant J. 31, 713–727. ( 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01390.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakizaki T, Matsumura H, Nakayama K, Che FS, Terauchi R, Inaba T. 2009. Coordination of plastid protein import and nuclear gene expression by plastid-to-nucleus retrograde signaling. Plant Physiol. 151, 1339–1353. ( 10.1104/pp.109.145987) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu X, et al. 2016. Convergence of light and chloroplast signals for de-etiolation through ABI4-HY5 and COP1. Nat. Plants 2, 16066 ( 10.1038/nplants.2016.66) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cosgrove DJ. 2016. Catalysts of plant cell wall loosening. F1000Res 5 ( 10.12688/f1000research.7180.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ortiz-Alcaide M, Llamas E, Gomez-Cadenas A, Nagatani A, Martinez-Garcia JF, Rodriguez-Concepcion M. 2019. Chloroplasts modulate elongation responses to canopy shade by retrograde pathways involving HY5 and abscisic acid. Plant Cell 31, 384–398. ( 10.1105/tpc.18.00617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brzezowski P, Richter AS, Grimm B. 2015. Regulation and function of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in plants and algae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 968–985. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fitzgibbon J, Beck M, Zhou J, Faulkner C, Robatzek S, Oparka K. 2013. A developmental framework for complex plasmodesmata formation revealed by large-scale imaging of the Arabidopsis leaf epidermis. Plant Cell 25, 57–70. ( 10.1105/tpc.112.105890) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faulkner C, Akman OE, Bell K, Jeffree C, Oparka K. 2008. Peeking into pit fields: a multiple twinning model of secondary plasmodesmata formation in tobacco. Plant Cell 20, 1504–1518. ( 10.1105/tpc.107.056903) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benitez-Alfonso Y, Cilia M, San Roman A, Thomas C, Maule A, Hearn S, Jackson D. 2009. Control of Arabidopsis meristem development by thioredoxin-dependent regulation of intercellular transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3615–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walter M, Kilian J, Kudla J. 2002. PNPase activity determines the efficiency of mRNA 3'-end processing, the degradation of tRNA and the extent of polyadenylation in chloroplasts. EMBO J. 21, 6905–6914. ( 10.1093/emboj/cdf686) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cushing DA, Forsthoefel NR, Gestaut DR, Vernon DM. 2005. Arabidopsis emb175 and other ppr knockout mutants reveal essential roles for pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins in plant embryogenesis. Planta 221, 424–436. ( 10.1007/s00425-004-1452-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, Zou W, Zhao J. 2015. Ribonuclease J is required for chloroplast and embryo development in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2079–2091. ( 10.1093/jxb/erv010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray JC, Sullivan JA, Wang JH, Jerome CA, MacLean D. 2003. Coordination of plastid and nuclear gene expression. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 358, 135–144; discussion 144–135 ( 10.1098/rstb.2002.1180). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hotto AM, Schmitz RJ, Fei Z, Ecker JR, Stern DB. 2011. Unexpected diversity of chloroplast noncoding RNAs as revealed by deep sequencing of the Arabidopsis transcriptome. G3 (Bethesda) 1, 559–570. ( 10.1534/g3.111.000752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mochizuki N, Brusslan JA, Larkin R, Nagatani A, Chory J. 2001. Arabidopsis genomes uncoupled 5 (GUN5) mutant reveals the involvement of Mg-chelatase H subunit in plastid-to-nucleus signal transduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 2053–2058. ( 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benitez-Alfonso Y, Jackson D. 2009. Redox homeostasis regulates plasmodesmal communication in Arabidopsis meristems. Plant Signal Behav. 4, 655–659. ( 10.1073/pnas.0808717106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stonebloom S, Brunkard JO, Cheung AC, Jiang K, Feldman L, Zambryski P. 2012. Redox states of plastids and mitochondria differentially regulate intercellular transport via plasmodesmata. Plant Physiol. 158, 190–199. ( 10.1104/pp.111.186130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rutschow HL, Baskin TI, Kramer EM. 2011. Regulation of solute flux through plasmodesmata in the root meristem. Plant Physiol. 155, 1817–1826. ( 10.1104/pp.110.168187) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hofius D, Herbers K, Melzer M, Omid A, Tacke E, Wolf S, Sonnewald U. 2001. Evidence for expression level-dependent modulation of carbohydrate status and viral resistance by the potato leafroll virus movement protein in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant J. 28, 529–543. ( 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01179.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.