Abstract

Endosymbiotic organelles of eukaryotic cells, the plastids, including chloroplasts and mitochondria, are highly integrated into cellular signalling networks. In both heterotrophic and autotrophic organisms, plastids and/or mitochondria require extensive organelle-to-nucleus communication in order to establish a coordinated expression of their own genomes with the nuclear genome, which encodes the majority of the components of these organelles. This goal is achieved by the use of a variety of signals that inform the cell nucleus about the number and developmental status of the organelles and their reaction to changing external environments. Such signals have been identified in both photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic eukaryotes (known as retrograde signalling and retrograde response, respectively) and, therefore, appear to be universal mechanisms acting in eukaryotes of all kingdoms. In particular, chloroplasts and mitochondria both harbour crucial redox reactions that are the basis of eukaryotic life and are, therefore, especially susceptible to stress from the environment, which they signal to the rest of the cell. These signals are crucial for cell survival, lifespan and environmental adjustment, and regulate quality control and targeted degradation of dysfunctional organelles, metabolic adjustments, and developmental signalling, as well as induction of apoptosis. The functional similarities between retrograde signalling pathways in autotrophic and non-autotrophic organisms are striking, suggesting the existence of common principles in signalling mechanisms or similarities in their evolution. Here, we provide a survey for the newcomers to this field of research and discuss the importance of retrograde signalling in the context of eukaryotic evolution. Furthermore, we discuss commonalities and differences in retrograde signalling mechanisms and propose retrograde signalling as a general signalling mechanism in eukaryotic cells that will be also of interest for the specialist.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Retrograde signalling from endosymbiotic organelles’.

Keywords: plastids, mitochondria, intracellular communication, signalling, metabolites, chloroplasts

1. Introduction

Life on Earth can be subdivided into three different major domains, the Bacteria, the Archaea and the Eukarya [1]. Typically, only the latter (maybe with the exception of some actinomycetes) form complex, multicellular organisms since they possess a number of specific structural and functional properties that are not found in the other two domains. One of the most important features of the Eukarya is their high degree of intracellular compartmentalization, giving rise to a number of membrane-bound structures and organelles with specific biochemical activities. The most prominent is the cell nucleus, which is not present in Bacteria and Archaea. Therefore, these two are often summarized as prokaryotes while the Eukarya are distinguished from them as eukaryotes by having a ‘true nucleus’, the literal meaning of the term [1].

In prokaryotes, the genomic DNA is localized within the cytoplasm together with all other soluble cell components, and these are all enclosed by a plasma membrane. In eukaryotes, the DNA is surrounded by a double-membrane forming the nucleus and separating the genetic material from the rest of the cell. Pores in the nuclear envelope membrane allow an exchange of molecules and a controlled transcription of genes within the nucleus followed by an export of RNAs into the cytoplasm, where translation takes place. By this means, transcription and translation can be spatially and temporally separated, providing additional levels of regulation in gene expression that are not present in prokaryotes [2].

The internal compartmentalization in eukaryotic cells not only separates transcription and translation, but also provides opportunities to separate specific biochemical pathways within the same cell, therefore providing a number of advantages in eukaryotic metabolism when compared with prokaryotes. This includes the avoidance of futile cycles, the localized concentration of certain metabolites and the separation of subcellular environments with different pH or ion concentrations. The latter has an important impact on energy metabolism, allowing for ATP production through membrane-based proton-gradients in both mitochondria and chloroplasts [3]. All of these advantages were highly beneficial for further evolution of eukaryotic organisms, leading finally to multicellular organisms.

2. Biochemical compartments of eukaryotic cells

Besides the nucleus, all eukaryotic cells possess a set of subcellular membrane-bound compartments that allow for metabolic specialization in eukaryotic cells. These include the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with the associated Golgi apparatus and vesicles, the peroxisomes, the mitochondria and, in some evolutionary lines, the plastids [3]. The ER is a complex, single-membrane-delimited structure that is directly connected to the nuclear envelope membrane and can either be associated with ribosomes (rough ER) or not (smooth ER). The ER provides a specific compartment for protein formation and maturation, and gives rise to an evolutionarily novel intracellular trafficking pathway, vesicular transport. The latter allows the passage of vesicle-enclosed components between the Golgi apparatus, endosomes and the plasma membrane. Both the ER and Golgi represent very dynamic compartments supporting the secretion and absorption properties of cells. Peroxisomes, in contrast, are small, relatively stable organelles with particular redox-related activities often used or involved in detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or other metabolic compounds [4].

Mitochondria and chloroplasts are the energy-converting organelles of eukaryotic cells, with chloroplasts being restricted to photosynthetically active eukaryotes [5]. In this context, it is important to note that eukaryotic organisms, like prokaryotes, can be metabolically subdivided into autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms. Autotrophic eukaryotes can directly assimilate CO2 through photosynthesis in chloroplasts while heterotrophic eukaryotes need to feed on organic carbon sources by respiration in mitochondria. All autotrophic eukaryotes, therefore, carry chloroplasts. These are, however, only one form of plastid [6]. Plastids are morphologically heterogeneous and also appear in a number of non-photosynthetic forms. The inverse conclusion, that all heterotrophic eukaryotes do not carry plastids, thus cannot be drawn and, in fact, is not true (for more details see below).

Mitochondria and plastids are special among all eukaryotic cell structures in that they were not generated by the evolution of the cell itself, but instead, they were acquired by endosymbiosis. Endosymbiosis is the engulfment and functional as well as structural integration of an independent unicellular organism into another cell. This evolutionary concept was denied for many years by many scientists using classical observational methodologies, but modern molecular biology provided unequivocal evidence for its occurrence [7]. Typical features of this endosymbiotic ancestry for both mitochondria and plastids are the double-membrane envelope with a eukaryotic-like lipid composition of the outer membrane and a prokaryotic-like composition of the inner, the presence of an organellar genome, and the existence of a corresponding gene expression machinery including bacterial-type 70S ribosomes. Furthermore, both organelles multiply by fission and their inheritance is by random distribution during the division of the host cell, often in a uni-parental manner [8,7].

3. Endosymbiotic ancestry and the requirement for organelle-to-nucleus communication

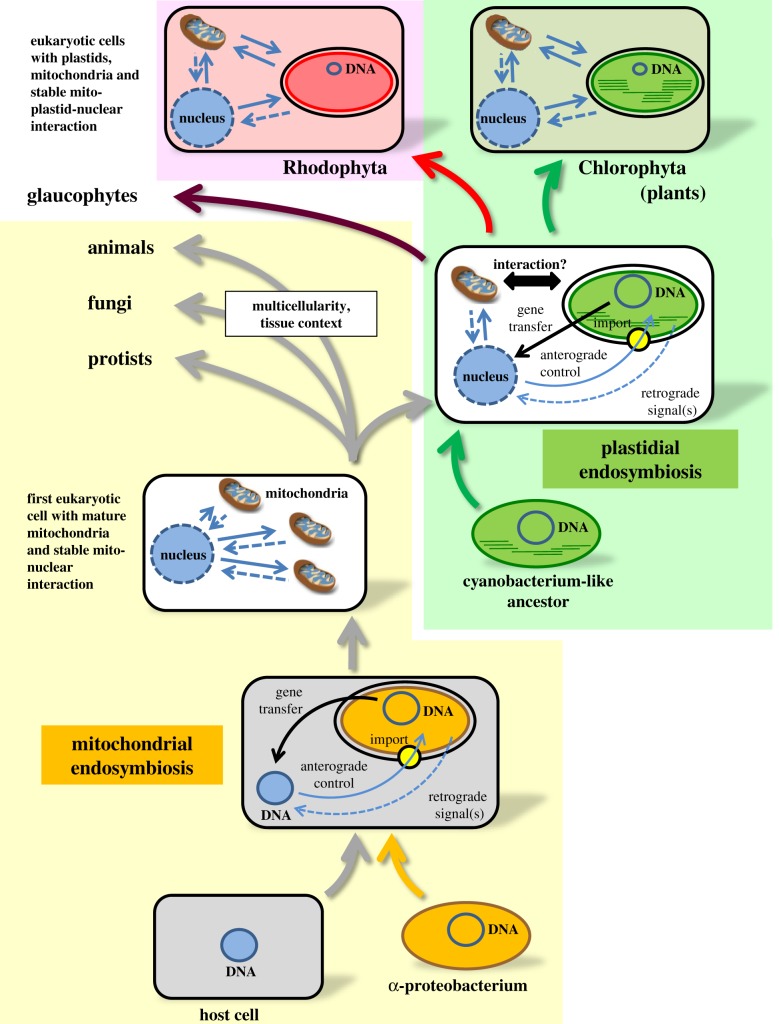

According to generally accepted hypotheses, the endosymbiotic event leading to mitochondria took place first. An α-proteobacteria-like organism was integrated into a more complex host cell. However, it is still debated when this took place, which species of bacteria was integrated and the nature of the host [7,9–11]. The acquisition of chloroplasts, in contrast, is better understood as it took place after the establishment of mitochondriated cells. It is estimated that a cyanobacterium-like ancestor was integrated into a eukaryotic host cell around 1.5–1.2 billion years ago [12] and this led to the first photosynthesizing eukaryotes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Establishment of retrograde control during the evolution of eukaryotes. The diagram depicts the major steps in the evolutionary acquisition of mitochondria and plastids by eukaryotes. Rectangles represent endosymbiotic host cell or eukaryotic host cell, respectively. Ovals represent bacterial ancestors and resulting endosymbionts as well as final plastids. Final mitochondria are represented by small icons with brown outer and blue inner membrane. DNA of endosymbionts is represented by blue circles and gene transfer to the nucleus by black arrows. The reduction of coding capacity is indicated by the reduced size of DNA-representing circles. Continuous light-blue arrows: anterograde signalling. Broken light blue arrows: retrograde signalling. Large connecting arrows in grey, green and red represent the evolutionary lines. Yellow circles represent the respective import machineries. Note that retrograde signalling from mitochondria was likely to be established when plastids evolved. Basic principles should have been conserved in the different evolutionary lines. Further evolution of mitochondrial retrograde signals in autotrophs, however, was probably influenced by the presence of plastids (double-headed arrow, ‘interaction?’). In heterotrophs, other influences such as multicellularity and tissue context may have generated different evolutionary constraints. In Rhodophyta (pink box) and Chlorophyta (green box), mitochondria, plastids and the nucleus developed triangular signalling networks.

Both endosymbiotic events were not immediate but gradual and took place over a very long time scale accompanied by successive rounds of horizontal gene transfer from the endosymbiont to the host cell (figure 1). This process largely contributed to the evolutionary integration of the endosymbiont into the cellular structure of the eukaryotes leading to the contemporary phylae [13]. Genome sequencing and modern bioinformatic analyses have contributed a great deal to our understanding of these complex evolutionary processes as they can track the relationships between genomes of species as well as of endosymbiotic organelles [14].

While quite precise models exist that describe the horizontal gene transfer during evolution, much less is known about the regulatory consequences of this transfer for the establishment of functional organelles. As already mentioned, organelles carry their own genetic material and are able to express it. It has long been debated why organelles retained their genomes and did not lose all of their genes, and different explanations have been proposed [15]. The two hypotheses that provide the best explanations to date to explain the existence of organellar genomes are (i) the need for rapid control by redox signals from the respective electron transport chains (ETCs) [16] and (ii) that the high hydrophobicity of membrane-located ETC components would generate problems for effective organelle targeting when encoded in the nucleus [17]. In fact, it has been proposed that hydrophobic membrane proteins would be targeted to the ER instead of mitochondria [15].

Typical mitochondrial genomes of heterotrophs such as mammals are quite small (approx. 16 kb), while those of plants are less reduced (table 1). Chloroplast genomes of vascular plants are around 150 kb in size and are highly conserved in gene arrangement and number (approx. 120 genes) (table 1). By contrast, proteomic analyses have revealed that mitochondria and plastids contain thousands of different proteins and that the corresponding composition is highly variable, depending not only on environmental conditions or tissue context, but also on the species [18–24]. In conclusion, contemporary organelles have lost the majority of their ancient coding capacity (most likely thousands of genes) and need to import the vast majority of their proteins from the cytosol via specialized import machineries [25,26]. As a consequence, it was believed that the nucleus dominates the protein content of the organelles in that cell. This regulation principle is called ‘anterograde signalling’ [27]. However, the imported nuclear-encoded proteins typically represent structural organellar components that do not exert direct signalling functions. A better term might, therefore, be ‘anterograde control’.

Table 1.

Main genomic and proteomic characteristics of mitochondria and plastids in different organisms. Genome size and coding capacity data were extracted from Ensembl (www.ensembl.org). For Plasmodium, all data were extracted from PlasmoDB (www.plasmodb.org). cod., coding genes; n.c., non-coding genes. Overview of genome and proteome sizes of eukaryotic organelles.

| species | Arabidopsis thaliana | Plasmodium | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Drosophila melanogaster | Homo sapiens | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| organelle | chloroplast | mitochondrion | apicoplast | mitochondrion | mitochondrion | mitochondrion | mitochondrion |

| genome size, structure | 154.5 kb, circular, up to 100 copies | 367 kb linear and circular | ∼35 kb | ∼6 kb, circular | 86 kb, circular | 19.5 kb, circular | 16.5 kb, circular |

| coding capacity | 157 genes (88 cod.; 69 n.c.) | 164 genes (122 cod. 42 n.c.) | ∼68 genes | ∼37 genes | 55 genes (28 cod.; 27 n.c.) | 37 genes (13 cod.; 24 n.c.) | 37 genes (13 cod.; 24 n.c.) |

| proteome | 2500–3000 proteins | >2000 proteins | ∼551 proteins | ∼246 proteins | 1000–3500 proteins | >1000 proteins | >1000 proteins |

Once imported, most cytosolic proteins need to be assembled into protein complexes together with organelle-encoded proteins. One recurrent pattern in organelles of all species is the observation that all major protein complexes of the ETCs contain subunits encoded in both nuclear and organellar genomes. Since the organellar genomes in their general structure are polyclonal and dozens to hundreds of organelles exist per cell, a 10 000-fold excess in coding capacity for organellar genes can easily exist in the same cell. For the coordinated expression of nuclear- and organellar-encoded subunits, therefore, there must be some type of communication or signalling from the organelles to the nucleus that informs the nucleus about the structural and functional state of the organelles and their internal protein complexes. Pioneering work confirming the existence of such signals from mitochondria was performed in yeast, while signals from plastids were discovered in barley [28,29]. This type of regulation from organelles was later termed ‘retrograde signalling’, ‘retrograde regulation’ or ‘retrograde response’ [27]. Recent research has uncovered numerous retrograde signalling pathways that report the current status of organelles to the nucleus under a variety of conditions and developmental situations. These signals inform the nucleus about the functional requirements of the organelles and also adjust nuclear gene expression for the highly divergent gene copy numbers between the nuclear and organellar genomes. For the establishment of true organelles during endosymbiosis, the generation of a network of retrograde signals thus became indispensable for the evolution of the endosymbiont (figure 1). For integration into the host cell, the establishment of retrograde signals must be regarded as equally important as horizontal gene transfer from the endosymbiont to the cell nucleus.

4. Classes of retrograde signals from organelles

For plastids, the original idea of a single plastid signal (or plastid factor) has been modified substantially over the last two decades and it is now widely accepted that a whole array of signals exist [30]. Currently, five major signal classes can be distinguished: (i) signals that originate from plastid gene expression [31,32], (ii) signals mediated by the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway [33], (iii) signals that depend on redox changes of components in the photosynthetic electron transport as well as coupled redox buffer systems and ROS [34,35], (iv) metabolic signals from disturbed or unbalanced plastid metabolism mediated by changes in the accumulation of 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (PAP) [36], 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclopyrophosphate (MEcPP) [37], β-cyclocitral (a ROS-dependent oxidation product; [38]) or apocarotenoids [39], and (v) signals mediated by dual-localized proteins acting in both the plastids and the nucleus [40]. Most of these signals become active under defined conditions depending on the developmental stage of the plastid, the tissue context it is in or the environmental conditions the organism is exposed to. Some act simultaneously or together and a functional classification of these signals is not easy as quite diverse molecular mechanisms for their respective signalling functions have been described or suggested. For plastidial signals, a categorization into biogenic, operational and degradational signals [41,42] has been now widely accepted as these align well with the respective developmental and/or functional state of the plastid. The group of biogenic signals typically comprises signals sent from plastids that are undergoing biogenesis and has only been studied in the context of chloroplast development. These signals adjust nuclear gene expression to meet the requirements for the establishment of novel organelles within growing or multiplying cells and organisms. By contrast, the group of operational signals represents signals that are sent from fully developed, functional plastids in response to changes in their immediate environment. Here, plastids display a sensor function that informs the cell nucleus about environmental influences that impact on the metabolism of the organelle. Retrograde operational signals then trigger appropriate cellular responses that re-balance organellar and wider cellular metabolism. Finally, degradational signals are retrograde signals sent from plastids that have become degraded or destroyed in response to external or internal stresses. These signals manage the controlled destruction of plastids (e.g. by autophagy) and the corresponding resource allocation of free compounds such as amino acids, lipids and so on. By this means retrograde signals provide an appropriate management of organelle function in the cell.

Signals from mitochondria are known as ‘retrograde response’ or ‘retrograde regulation’ and have been well characterized in animals and fungi. Despite a great variability in the signalling pathways between animal classes (e.g. mammals, worms, insects) it is possible to clearly distinguish three classes of signals: (i) signals emitted under energetic stress, (ii) signals involving Ca2+-dependent responses, and (iii) signals mediated by ROS under a number of stresses [43]. Mitochondria show less variability in morphology than plastids but they display a remarkable flexibility in their metabolic activity. Retrograde signals from mitochondria, therefore, are involved in a high number of reactions that affect cellular homeostasis and trigger appropriate adjustments to various stresses, e.g. metabolic imbalances, energetic limitations, oxidative stress or disturbance of mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control. In heterotrophs, these stresses have a strong impact on mitochondrial to nucleus (mito-nuclear) feedback, the integrated stress response (ISR) and lifespan regulation, as well as on extracellular communication [43]. In plants, we are only just beginning to understand the retrograde response, but considerable progress has been made in recent years (see below) and many new reports suggest a similarly important role to that observed in heterotrophs.

5. Retrograde signalling from plastids

In multicellular organisms such as plants, chloroplasts can be found in all green tissues, where they perform photosynthesis. This is the most common form of plastid, but there are a great variety of other non-photosynthetic plastid types that are associated with other functions. Roots and other non-photosynthetic tissues contain colourless amyloplasts which store starch, in fruits or flowers yellow or orange/red chromoplasts synthesize carotenoids to provide tissues with attractive colours, and in seeds elaioplasts perform lipid storage. However, none of these forms is fixed and plastids can even switch between different forms depending on external conditions [6]. All of these plastid types develop from a non-differentiated precursor, the proplastid, which is found in meristems and in seeds. In most plant species it is inherited by the egg cell. Thus, mutants with plastid defects often show a maternal inheritance. Nevertheless, despite their different appearance, the plastid genome qualitatively is the same in all cases and their respective function depends only on the protein composition determined by the anterograde control pathways that are activated by the respective tissue context [44]. It should be noted, however, that not much is known about the gene copy number in different plastid types, and quantitative effects cannot be excluded [45].

(a). Retrograde signalling from plastids during chloroplast biogenesis (biogenic signalling)

One of the major plastid transitions takes place when plant seedlings move from darkness to light. During this critical time, photoreceptor-mediated signalling drives the change from a skotomorphogenic to a photomorphogenic growth strategy including the rapid development of chloroplasts from etioplasts (another plastid type) or proplastids. Chloroplast development is mediated by internal changes following the light-dependent conversion of the chlorophyll precursor protochlorophyllide to chlorophyllide and by the induction of thousands of nuclear genes required for the assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus and to enable other chloroplast functions [26,46]. As discussed earlier, nuclear control of chloroplast development is mediated via anterograde signalling. However, as with any assembly process, information needs to be fed back about the status of what is being built. In this case, information about the state of chloroplast development is signalled to the nucleus to modulate this transcriptional response. While we currently know rather little about how this signal is produced and transmitted, its existence can be demonstrated by looking at the expression of nuclear-encoded transcripts in mutants that affect chloroplast development or when development is blocked by inhibitors. For example, the commonly used inhibitors norflurazon (NF), which blocks carotenoid biosynthesis, resulting in chloroplast photobleaching, and lincomycin (Lin), a plastid translation inhibitor, both result in inhibition of about 1000 nuclear genes [47–49]. To date, this work has focused predominantly on the model plant Arabidopsis, but the article by Duan et al. [50] in this issue has started to investigate this system in the model monocot rice. Differences observed between species may help us identify the key conserved features of this response. The genes downregulated after chloroplast damage not only encode proteins destined for the developing chloroplast, but also for many others functions consistent with the integration of the chloroplast into cellular metabolism and more broadly in different cell types and tissues [51]. In this issue, one example of such regulation is addressed by Richter et al. [52], who describe the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis by retrograde signalling. In addition to significant transcriptional regulation, there is also evidence that retrograde signals affect gene expression post-transcriptionally [53], including though mRNA splicing [54] and regulation of protein abundance [55].

The physiological interpretation of the effects of inhibitor treatments is still a subject of debate. While it might be expected that developing chloroplasts are always in communication with the nucleus and the loss of nuclear gene expression represents the reduction in a positive retrograde signal [33], some researchers interpret the treatment as triggering an inhibitory signal. To some extent, this has been resolved genetically by the identification of mutants in which the nuclear transcriptional response is uncoupled from chloroplast status. These genomes uncoupled (gun) mutants were identified based on an increase in expression of LHCB1.2 following treatment with NF [56]. In total six gun mutants have been identified, and these provide significant insight into what might be happening. Five of the mutants, gun2–gun6, have mutations in genes encoding proteins associated with tetrapyrrole synthesis [57–59]. This includes the phytochrome chromophore synthesis (haem-degradation) proteins, haem oxygenase (GUN2) and phytochromobilin synthase (GUN3), as well as GUN4 and GUN5 (H subunit of Mg-chelatase), required for efficient synthesis of Mg-protoporophyrin IX, a chlorophyll precursor. The gun6 mutant results in the increased expression of ferrochelatase 1 (FC1), an enzyme that mediates the synthesis of haem. Crucially, the gun6 mutant is dominant, leading to the hypothesis that the synthesis of haem by FC1 is required for the production of a positive retrograde signal that promotes the expression of photosynthesis-associated nuclear genes (PhANGS) [58], with the other gun mutations serving to promote haem accumulation less directly. This is still the dominant hypothesis for the role of tetrapyrroles in retrograde signalling and no data have yet been published that disprove it. Nevertheless, supporting evidence has been limited to date. Now in this issue Page et al. [60] demonstrate that overexpression of FC1 in the chloroplast alone can result in a gun mutant phenotype, supporting the role for FC1-synthesized haem in chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signalling. How haem might regulate gene expression in plants is largely unknown but two contributions in this issue also address this question. Shimizu et al. [61] describe a proteomics study to identify haem-binding proteins in Arabidopsis and the alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae that could contribute to haem transport or signalling. One suggestion for proteins that could be involved comes from Sylvestre-Gonon et al. [62], who hypothesize a role for τ glutathione transferases in tetrapyrrole metabolism and retrograde signalling in plants.

While a role for tetrapyrroles is well established (see also [63]), perhaps the key to understanding retrograde signalling from the chloroplast is understanding the function of the rather enigmatic protein GUN1. The gun1 mutant shows the strongest phenotype of any of the gun mutants (based on less reduction of nuclear gene expression after NF treatment when compared with wild-type (WT) under identical conditions) and while the protein affected, a chloroplast-localized, pentatricopeptide-repeat protein, has been known for sometime [47], there are still numerous hypotheses for the function of the GUN1 protein. Recent evidence has centred on a role for GUN1 in chloroplast protein homeostasis [64–66], which may explain why only gun1 of the gun mutants has elevated nuclear gene expression after Lin treatment as well as NF treatment. How it does this is an open question, with recent studies suggesting a range of specific functions. One interesting proposal is that GUN1 functions in chloroplast protein import through its interaction with the chloroplast chaperone cpHSC70-1 [67]. In this model, the resulting accumulation of chloroplast pre-proteins in the cytosol in the gun1 mutant enhances nuclear gene expression, resulting in the gun phenotype [67]. While the promotion of gene expression in this system is perhaps surprising, there are clear similarities with the mitochondrial proteostatic responses discussed later. Another proposed role for GUN1 in protein homeostasis is in chloroplast gene editing [68], which has been shown to be altered under many conditions affecting retrograde signalling [69]. Two contributions to this issue further explore the role of GUN1 within the context of plastid protein synthesis and homeostasis. Tadini et al. [70] review the literature on the link between chloroplast transcription and retrograde signalling, focusing in particular on regulation of the nuclear-encoded (NEP) and plastid-encoded (PEP) plastid RNA polymerases. They also discuss the role of GUN1 in this process and in chloroplast protein homeostasis more broadly. The study by Loudya et al. [71] directly addresses many of the issues raised. They investigate the cue8 mutant, which has defects in chloroplast transcription and retrograde signalling that are partially dependent on GUN1 and demonstrate a ‘retro-anterograde’ correction that leads to elevated expression of NEP-dependent genes [71]. While GUN1, therefore, is strongly linked to various aspects of plastid protein synthesis, perhaps the most intriguing of the recent results on GUN1 is the observation that it can also alter tetrapyrrole metabolism [72]. The mechanism is not well understood but may involve interaction with tetrapyrrole enzymes [73] as well as direct tetrapyrrole-binding [72]. One possibility is that GUN1 provides a link between key chloroplast processes required for chloroplast protein synthesis and regulation of the tetrapyrrole pathway, where it may function to directly read out the FC1-dependent haem signal [72].

And what about the other three classes of retrograde signals—do they also have a role in chloroplast biogenesis? ROS production is mostly associated with the photosynthetic apparatus which is not yet mature in a developing seedling. However, singlet oxygen (1O2) derived from chlorophyll biosynthesis intermediates has been shown to inhibit the expression of tetrapyrrole pathway (in particular) and other photosynthetic genes following mis-regulation of chlorophyll synthesis [49]. Certainly, the developing chloroplast will have started to synthesize a range of metabolites that may be important. One recent example is the identification of a cis-carotene-derived apocarotenoid that is required for etioplast and chloroplast development [39].

Finally, proteins dually localized to the chloroplast and nucleus seem to be critical for normal chloroplast biogenesis. Pioneering work characterized Whirly1 as a nuclear-encoded protein that localizes in the plastid nucleoid but is also able to translocate from its plastid location to the nucleus [40,74,75]. Such a dual localization was then reported or predicted for more proteins [76], suggesting the mechanistic possibility for retrograde control through proteins released from the plastid. An independent screen for novel regulators in phytochrome regulation identified HEMERA [77], a protein also known as the PEP subunit pTAC12/PAP5 [78,79]. The HEMERA protein can also localize to the nucleus, where it directly interacts with phytochrome-interacting factor (PIF) proteins to regulate transcription of PhANGs [80]. During light-induced chloroplast biogenesis, the PEP complex is reorganized by the association of 12 additional nuclear-encoded proteins, the PEP-associated proteins (PAPs) [79,81]. Genetic inactivation of any PAP leads to albinism, indicating the importance of these proteins for chloroplast biogenesis [82]. Recent studies identified two further proteins, RCB and NCP, as important regulators of PEP restructuring. Both appear to be dual-localized and to interact with the phytochrome signalling system [83,84]. As the sequences of half of the 12 PAPs contain predicted nuclear localization signals [85], even more of the PAP proteins may function in this way. The potential role of these dual-localized proteins in retrograde signalling is reviewed in detail in this issue by Krupinska et al. [86] and Tadini et al. [70].

(b). Operational signalling from plastids

Operational signals from plastids are typically connected to the functionality of chloroplasts [42]. The dominant process in this plastid type is photosynthesis, the process that generates carbohydrates from ambient CO2, H2O and sunlight. In photosynthesis, the light-driven electron transport from water to NADP+ (the light reaction) in the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts is functionally coupled to the chemical reactions in the stroma (the dark or carbon reaction), in which carbohydrates are generated by the consumption of ambient CO2, ATP and NADPH2. Because of the functional coupling of both reactions, photosynthesis becomes very sensitive to changes in illumination, temperature or availability of water and CO2 (via the opening of stomata). Variations in one or several of these environmental factors translate into imbalances of photosynthetic electron transport, leading to changes in the reduction/oxidation (redox) state of the involved components. A prominent example for this type of regulation is the redox control initiated at the plastoquinone pool, the electron carrier that connects photosystem (PS) II with the cytochrome b6f (Cytb6f) complex. Its redox state acts as a major regulator of PS genes in both the plastid and nucleus, triggering a fine-tuning of PS stoichiometry and antenna protein synthesis in response not only to light-quality gradients found in dense plant populations [87], but also to fluctuating light intensity conditions or sudden high light stress. Aspects of this complex topic have been discussed in a contribution to this issue [88].

Photosynthetic organisms often perceive strong gradients in light intensity that show high spatial and high temporal dynamics. Very strong illumination can exceed the photosynthetic capacity of organisms and, therefore, lead to a situation in which excess excitation energy must be dissipated. This is achieved by the removal of the absorbed energy as heat via non-photochemical quenching or by transferring excess electrons to oxygen, generating ROS, which are detoxified by redox buffer systems such as the glutathione/ascorbate systems, peroxidases or glutaredoxins [89]. The protein components in these systems are encoded in the nucleus and are additionally upregulated in response to increasing stress. The accumulation of ROS can also occur under low light when the ambient temperature is low, or when the Calvin cycle is inefficient because of substrate limitations. In all these cases the accumulation of ROS serves as an important stress signal which triggers several acclimation responses in the nucleus. There has been much debate about the specificity of such a signalling system as well as the spatio-temporal distribution of ROS signals, and a lot of current research in this field is still focused on these questions. However, since the first proposal of plastid redox signals acting as retrograde signals [90], the field has progressed a lot and far more detailed working hypotheses have now been developed [91], including one in a contribution to this issue [92].

Uncharged ROS like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are able to pass through membranes and, therefore, may leave the chloroplast in order to activate cytosolic signalling pathways under conditions of excessive accumulation. It was shown that chloroplast-generated H2O2 is linked to cytosolic MAP kinase cascades that activate corresponding compensatory responses in the nucleus [93]. However, most ROS exhibit very short half-lives, preventing a direct signalling function by long-range diffusion [94]. Instead, ROS like 1O2 or superoxide initiate signalling pathways that are mediated by oxidized compounds such as β-cyclocitral [38]. In addition, specific metabolites have been identified that accumulate under stress, such as the dinucleotide 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (PAP) [36] and the isoprenoid precursor MEcPP [37]. Furthermore, an apocarotenoid-dependent signal was recently identified that is required for proper plastid development [39]. All these metabolites are much more stable than ROS and could be actively transported across the chloroplast envelope, diffuse through the cytosol and induce appropriate responses in the nucleus. Since they are small molecules they may even diffuse through plasmodesmata into neighbouring cells. One contribution to this issue deals with the interesting aspect of retrograde control in cell-to-cell signalling [95].

In addition, a number of specific signalling proteins such as EXECUTER 1 and 2 [96] were identified that relay 1O2 signals towards the outside of the plastid (via a still unknown mechanism), inducing stress responses or even cell death [97]. Novel data strongly suggest that the β-cyclocitral- and EXECUTER-dependent pathways act independently, leading to two separate signalling pathways, although starting from the same ROS [98]. However, it appears that the two pathways originate at different sites of 1O2 formation (PSII reaction centre versus grana margins), indicating that the intracellular location of ROS formation is an important determinant for the signalling pathway used. Interestingly, the biogenic 1O2 signal described earlier is also partially dependent on EXECUTER proteins although presumably originating at a different plastid location entirely [49]. Intracellular location is also important for another novel potential pathway for ROS signalling that was recently proposed which involves the close proximity of the nuclear envelope with extensions of plastids called stromules [35]. This close proximity provides the opportunity for direct transfer of ROS into the nucleus without passage through the cytosol. Details of this novel pathway are discussed in this issue [99].

ROS are also involved in retrograde signalling from mitochondria (see below). Since both organelles operate simultaneously within the same cell, one needs to ask how specificity in this signalling is achieved [100]. In energy metabolism, a tight functional interaction between plastids and mitochondria developed during the course of evolution. It can, therefore, be assumed that such interaction developed also in the context of retrograde signalling. Recent results have provided the first evidence that retrograde signals from chloroplasts and mitochondria indeed act in a coordinated or mutual manner for reciprocal regulation of status or gene expression [101–103]. In the light of these new results, it should be remembered that mitochondrial and plastid gene expression systems are both under initial control of nuclear-encoded phage-type RNA polymerases that trigger all primary gene expression events in both organelles [104]. A mutual control of organellar gene expression by retrograde signals from the respective other organelle, therefore, can be easily established. Nevertheless, both the functional and the evolutionary contexts are far from being understood and many aspects of the mutual regulation of mitochondria and chloroplasts remain to be explored.

(c). Degradational signalling from plastids

Natural senescence in plants is known to cause slow chlorosis accompanied by a targeted degradation of chloroplasts. This helps the plant to recover nitrogen, lipids and amino acids mostly from chlorophyll, the highly abundant enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (known as RuBisCO) and the thylakoid membranes [105]. Similar processes occur in response to drought stress, while in a hypersensitive response to pathogen attack resource allocation is not possible because of the rapidity of the response that sacrifices tissue resources for the sake of isolation and separation of the pathogen [106]. In the light of global environmental change and the expected (and already experienced) extended drought phases in many countries, control of chloroplast degradation becomes an interesting target for improving plant drought and stress tolerance [107]. It has been demonstrated that stabilizing the lifespan of chloroplasts under drought stress improves the ability of plants to recover upon re-hydration, thus expanding the vegetative growth phase and biomass production [108]. Delaying or downregulating degradational signals that induce resource allocation in response to drought may help to achieve these goals. In this context, it is interesting to note that stressed chloroplasts are able to send a 1O2-generated signal that activates ubiquitin-mediated chloroplast degradation, representing a potential mechanism for avoidance of oxidative stress through ROS-overproducing chloroplasts [109]. Targeted degradation of damaged chloroplasts, however, provides a means to reallocate valuable resources during acute stress. Future research will provide more insights into this complex response.

(d). Species with alternative plastid types

The evolution of plastids did not follow a strict vertical route but is complicated by a number of horizontal endosymbiotic events. After the unique primary endosymbiosis event, the plastid-bearing evolutionary line split into glaucophytes, red algae and green algae (figure 1). From the latter, the land plants emerged around 450–500 Ma [110]. Within the red and the green lineage, organisms exist that contain plastids with three, four or even five envelope membranes. Morphological and molecular analyses have identified such organisms as representatives of secondary and tertiary endosymbiotic events having integrated eukaryotes that already possessed plastids [111]. We only can speculate on the establishment of retrograde signals in secondary and tertiary plastids, but since such organisms exist we must assume that specific molecular signalling pathways evolved that coordinate the multiplicity of their intracellular genomes. This is of special interest as a number of pathogenic parasites within the phylum Apicomplexa possess secondary, non-photosynthetic but essential plastids, among them Plasmodium sp. and Toxoplasma gondii, which cause severe diseases such as malaria and toxoplasmosis [112]. In addition, many species in this phylum carry only a single mitochondrion with a single nucleoid. Its division is strictly coupled to the cell cycle of the parasite [113] and proper timely expression of mitochondria-located, nuclear-encoded proteins is absolutely essential for the survival of these cells. Understanding retrograde expression control of the imported proteomes of both the apicoplast and the mitochondrion may pave new avenues to identify potential drug targets for fighting such parasites [114].

6. Retrograde signalling from mitochondria in heterotrophs

In heterotrophic organisms, retrograde signals from mitochondria are one of the ways in which mitochondria and the nucleus communicate [28,43,115]. These signals are mainly activated upon stress and their diversity increases in parallel to the organismal complexity owing to the tissue specialization that occurs in multicellular organisms. In unicellular organisms, such as yeast, retrograde signals are mainly associated with the rewiring and adaptation of metabolism to the source of nutrients present in the environment; however, in multicellular organisms, there is a great variety of retrograde signals that operate adapting cellular functions to each tissue and environment. Therefore, retrograde signals observed in neurons of mammals can be different from those observed in muscle or liver cells, and even different from those observed in the neurons of other organisms. Despite the great variety of responses that have been identified in heterotrophic organisms, the canonical retrograde signals can be classified in three main categories depending on the stressor that triggers the activation: energetic stress response, calcium-dependent response and ROS-dependent response [28,43,115]. The aim of all retrograde signals is to activate a set of nuclear genes that alleviate the cellular stress originating in the mitochondria. These genes can modify cellular metabolism from oxidative to glycolytic, activate alternative pathways to generate ATP in the cell, promote mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control mechanisms, regulate calcium metabolism by stimulating its transport and storage, or activate antioxidant responses [43,116]. The activation of retrograde responses depends on a series of mediators that are either released from mitochondria or originated in the cytosol as a consequence of the dysfunctional mitochondria. These include mainly ions, such as calcium, ROS, and metabolites, such as AMP, NAD+ or tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates [117]. Of note is that many of the metabolites of the TCA cycle are also required for regulating epigenetic marks in the nucleus, participating, therefore, in the regulation of mitochondrial protein synthesis and cellular adaptations in homeostasis and stress [118].

In addition to the classical retrograde signals, there are other forms of mito-nuclear communication activated upon stress that also have a retrograde signalling component [43]. These signalling pathways are mainly triggered by proteotoxic stress, and their output can be a specific proteostatic response or a general response that not only repairs the protein defects but also regulates metabolism to adapt to the cellular requirements. There are multiple responses associated with proteostatic stress, most of them described in yeast and worms. The translation of these responses to more complex organisms, such as flies or mammals, is sometimes difficult owing to the higher complexity and tissue specialization, and they may differ from those of lower organisms. In yeast, several responses have been identified upon proteotoxic stress. For instance, when mitochondrial protein import is decreased or blocked, it results in an accumulation of misfolded or unimported mitochondrial-targeted proteins, a phenomenon called mitochondrial precursor overaccumulation stress (mPOS). This stress condition activates a particular response, the unfolded protein response (UPR), by the mistargeting of proteins (UPRam) that alleviate the stress by decreasing the rate of cytosolic protein synthesis and by activating proteasomal degradation in the cytosol [119,120]. In addition, the accumulation of precursor proteins at the mitochondrial surface due to impaired mitochondrial protein import activates a similar response in yeast, known as mitoCPR (mitochondrial compromised protein import response). This response is mediated by the expression of Cis1, which binds to the import protein Tom70 and recruits the ATPase Msp1, promoting the clearance of stalled proteins from the import channels and targeting them for degradation by the proteasome [121]. Both UPRam and mitoCPR require the coordination of mitochondria and nucleus to activate a cross-compartmental response involving proteasomal degradation. The importance of interconnection and communication between compartments in yeast has also been highlighted with the discovery of the mechanism called MAGIC (mitochondria as guardian in cytosol) [122]. This stress response, which may also exist in human cells, leads to the degradation of cytosolic protein aggregates in the mitochondria. Thus, after heat-shock stress, cytosolic and mitochondrial protein aggregates interact with the mitochondrial import complex and can enter the mitochondria to be degraded by proteases [122].

In multicellular organisms, the main mitochondrial stress responses are the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) and the mitochondrial ISR, both being conserved between nematodes, flies and mammals, but with some specific properties in each organismic group. The UPRmt is most well studied in worms and was first described as a proteostatic response; however, nowadays, it is known that its function goes beyond that and should be considered as a general stress response [123]. The UPRmt is regulated in worms by the mitochondrion-targeted transcription factor ATFS-1, which upon mitochondrial stress is partly retained in the cytosol and translocated to the nucleus where it activates the expression of several nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes that participate in quality control, such as protease and chaperone genes, mitochondrial dynamics, mitochondrial transport, glycolysis and antioxidant detoxification [124]. In mammals, it has been proposed that the activation of the UPRmt is mediated by ATF5, which acts as an orthologue of ATFS-1 [125]. However, it has been demonstrated that the main stress response in mammals and flies is the ISR [126–130]. Mitochondrial stress can activate the ISR through any of four kinases, PERK, GCN2, PKR or HRI [131–135], which in turn phosphorylate the translation initiation factor eIF2α. Phosphorylation of eIF2α decreases general cytosolic translation but, at the same time, favours the translation of a certain set of genes though upstream open reading frames, including ATF4, ATF5 or CHOP [136]. ATF4 acts as the main mediator of mitochondrial stress in mammals and flies, promoting the transcription of a specific set of genes that mainly reprogramme cellular metabolism to adapt to the stress conditions. Depending on the stressor, the cellular context and the timing, different outputs may be promoted, including remodelling of one-carbon metabolism, activation of metabolic cytokines such as FGF21 and GDF15, stimulation of an antioxidant response, or even enhanced mitochondrial respiration through promoting supercomplex assembly [126–130]. Regulation of these processes occurs in temporal stages, as observed in a model of mitochondrial myopathy, in which it is regulated by the autocrine and endocrine effects of FGF21 [137].

All forms of retrograde signalling are needed for a proper maintenance of the homeostasis of heterotrophic organisms. However, long-term activation or an exacerbation of the response can also be deleterious; consequently, in some contexts, an inhibition of the activation can help cells, tissues and organisms to recover from the stress and even promote longevity, in a so-called mitohormetic fashion [138]. Mitohormesis defines a biological response in which the induction of low levels of mitochondrial stress, mainly associated with increased ROS levels, promotes health and organismal viability. As an example, this issue features studies describing retrograde signals in heterotrophic organisms in two important contexts: the nervous system and their connections with different neurological diseases [139] and their function regulating proteostasis and longevity [140].

7. Retrograde signalling from mitochondria in autotrophs

Although mito-nuclear signalling had been described for many decades in heterotrophic organisms [141], mechanistic insight into plant retrograde signalling, here referred to as mitochondrial retrograde regulation (MRR) [142], has only been obtained in the last 10 years. Plant MRR was originally described in the context of the induction of alternative oxidase transcripts in response to mitochondrial inhibition [143]. With the advent of microarray technology, it was realized that a much wider set of genes responded to mitochondrial dysfunction, for instance, triggered by chemical inhibition of mitochondrial enzymes [144] or by mutation of important mitochondrial proteins [145]. Using a range of screening methods, various transcription factors were discovered that could influence the expression of MRR marker genes, mainly using Arabidopsis thaliana as a model system. Firstly, abscisic acid insensitive 4 (ABI4) was shown to keep ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE 1a (AOX1a) expression in a repressed state [146]. Several WRKY transcription factors (mainly WRKY15, WKRY40 and WKRY63) were then implicated in co-regulating nuclear stress-responsive transcripts that encode mitochondrial and chloroplast proteins [147–149]. Also, MYB29 was shown to have a repressive role on MRR responses [150], influencing the interplay of phytohormones (ethylene, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid) and ROS.

Probably the most significant breakthrough was made with the discovery of a class of transmembrane-domain-containing NAC transcription factors (ANAC013, ANAC016, ANAC017, ANAC053, ANAC078) by forward genetic and DNA-binding screens [151,152]. Further studies have established that ANAC017 has the largest contribution in responses to both chemical [148,152] and genetic [153–155] mitochondrial inhibition, and is thus currently considered as a master regulator of plant MRR. Interestingly, this group of ANAC transcription factors have been shown to be attached to the ER and can be remobilized, most likely by proteolysis, to the nucleus [151,152].

This central location in the cell may allow the ANAC transcription factors such as ANAC017 to regulate responses to a variety of cellular stresses, including chloroplast stress [148]. An overlap between PAP-regulated and ANAC017-regulated genes was observed, providing more evidence for a convergence of mitochondrial and chloroplast retrograde signalling [156]. The enzyme producing PAP (called SAL1) is also dual-targeted to chloroplasts and mitochondria [36]. In fact, many regulators of plant MRR have been implicated in chloroplast retrograde signalling, including ABI4, WRKY40 and CDKE1 [47,157–159], although recent evidence has ruled out a role for ABI4 in chloroplast biogenic signalling [160]. This interaction between plant mitochondrial and chloroplast retrograde signalling has been explored in detail in a review in this issue [100]. The ANAC017-induced genes are thought to help plants cope with oxidative stresses originating from the chloroplast, for instance during inhibition with methyl viologen [148,151]. Recently, the Arabidopsis radical-induced cell death 1 (RCD1) protein was shown to bind ANAC017 and ANAC013 transcription factors and is thought to keep them in an inactive state, thereby repressing MRR responses [154]. In this issue, Shapiguzov et al. [103] further explore how plants respond to methyl viologen, and show that hypoxia can reduce electron transfer from PSI to oxygen (the Mehler reaction) specifically in rcd1 mutants, but not in WT plants. As rcd1 plants show a constitutively high level of ANAC017 target genes, the authors could confirm that the effect of hypoxia on the Mehler reaction could be mimicked by the preincubation of WT plants with antimycin A (AA) or by overexpression of ANAC013, which both switch on the MRR pathway. The effect could not be directly attributed to alternative oxidases, indicating that other MRR target genes are responsible for this effect. A very large overlap in target genes triggered by mitochondrial dysfunction and low oxygen treatment have been observed [161]. This suggests that response to low oxygen, for instance during flooding or germination, may depend at least in part on mitochondrial plasticity controlled by ANAC017 [161,162]. Very recently, the protective role of ANAC017 in flooding tolerance was experimentally confirmed [163]. Conversely, ANAC017 may have a growth-limiting effect when expressed or active at high levels [164]. ANAC017 has also been implicated in other processes such as cell wall synthesis [165] and senescence [164,166]. Although so far the retrograde signalling-related roles of ANACs have been studied mostly in Arabidopsis, it is likely that this plant-specific MRR signalling pathway (NACs are a plant-specific protein family) has evolved with plant colonization of land [167]. It will thus be of significant interest to study whether similar MRR pathways are conserved throughout the plant kingdom. The computational models suggesting that MRR appeared in conjunction with the colonization of land are in line with the observation that plant MRR is of importance for resistance to e.g. flooding, a condition that is uniquely associated with terrestrial growth. Similarly, the evolution of PAP-related chloroplast retrograde signalling appears to be associated with land colonization and dehydration tolerance [168].

Besides AOX1a, ANAC017 is thought to co-regulate up to 200 genes (or even more during e.g. AA treatment), many of which are involved in non-mitochondrial cellular processes [153], for example, genes affecting hormone balances that could control how a plant prioritizes between growth and defence. Indeed, it appears that auxin signalling and MRR are antagonistic pathways [169,170]. Interestingly, a role for ethylene in plant MRR is emerging, with ethylene being produced during mitochondrial dysfunction [171] and boosting MRR responses. In this issue, Merendino et al. [155] found that when Arabidopsis mutants with mitochondrial defects were germinated in the dark, morphological changes were observed that are reminiscent of etiolated seedlings exposed to high ethylene concentrations (the triple response), including extreme apical hook formation. This is in line with previous findings that atphb3 mitochondrial mutants show increased sensitivity to ethylene [171]. Merendino and colleagues further showed that this extreme ethylene response is dependent on the activity of AOX1a. Furthermore, increased AOX1a transcript levels and activity was found to be largely regulated by ANAC017, so it appears that ANAC017 plays an important part in this exaggerated ethylene sensitivity by regulating AOX1a levels [155]. As mitochondria are of key importance during germination, when seedlings would often have to penetrate through soil deprived of light and perhaps sufficient oxygen, it makes sense that there are response mechanisms in place that adjust plant growth to mitochondrial activity during seed germination. The apical hook is thought to protect meristems from physical damage inflicted during soil emergence. Exactly why AOX1a activity would be so crucial for this process, and how AOX1a controls a downstream response affecting the apical hook angle is currently unclear.

The role of ethylene was examined more directly in another study in this issue [172]. It was shown that ethylene boosts MRR to AA in Arabidopsis, while blocking of ethylene signalling partially represses MRR. However, ethylene signalling components like EIN2 or the kinase MPK6 do not seem to be required for MRR, indicating that ethylene is not necessary for ANAC017-dependent MRR, but can promote it. At this stage, it remains difficult to draw clear conclusions on the interaction of MRR and ethylene signalling, but it appears that mitochondrial defects could cause the plants to produce more ethylene. When grown in the dark, this increased ethylene production likely contributes to the triple-response-like effects observed by Merendino et al. [155], mediated by AOX1a, and requiring ANAC017 for its full induction. The ethylene appears to further boost ANAC017-dependent MRR, suggesting there is a weak positive feedback loop occurring. More research will be needed to clarify the link between MRR and ethylene.

Another area that is just at the beginning of being explored in plants is the UPRmt. Two recent studies showed that treatments used in heterotrophic systems to induce UPRmt (e.g. doxycycline) also trigger transcriptomic and physiological responses in plants [173,174], demonstrating an interaction with a wide range of phytohormone signalling pathways such as jasmonic acid, auxin and ethylene. A wide range of transcription factor classes were suggested to play a potential role. In this issue, Kacprzak et al. [172] showed that there is a significant overlap between the transcriptomic responses that trigger UPRmt and AA-induced MRR. The genes in common appeared to belong to the ANAC017 regulon, so it was found that indeed ANAC017 plays a key role in mediating transcriptional responses and physiological resistance to a wide range of inhibitors that are used to induce UPRmt in non-plant systems, including doxycycline, MitoBlock-6, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and chloramphenicol. These treatments did not induce chloroplast UPR marker genes, demonstrating that mostly mitochondria were affected. ANAC017 loss-of-function mutants showed increased susceptibility when grown on UPRmt-inducing media, while ANAC017 overexpression lines were more resistant. Another study in this issue performed whole-genome transcriptome studies on knock-down lines of another Arabidopsis mitochondrial ribosomal protein, RPS10 [175], which is also interesting as a model for UPRmt in plants. Here, the ANAC017 regulon was strongly induced, and the analysis showed that the only common differentially regulated genes between doxycycline treatment, mrpl1 and rps10 mutants were well-known AA-induced ANAC017 target genes (e.g. NDB4 and At12Cys-2). It thus appears that the classical MRR pathway and the newly discovered UPRmt response in plants are likely identical, and are to a large extent under the control of ANAC017.

Despite many decades of work in chloroplast retrograde signalling, many of the key signalling intermediates are still unknown. This appears to be the case also for plant MRR, as we still have very little insight into how mitochondrial dysfunction results in the proteolytic activation of e.g. ANAC017 on the ER membrane, except that it may be cleaved by rhomboid-type proteases [152]. A significant overlap between hydrogen peroxide and AA-induced signalling suggests that ROS could play an important role as signalling intermediates. However, compounds such as the mitochondrial and cytosolic aconitase inhibitor monofluoroacetate are not thought to induce a significant level of ROS responses, but are still capable of inducing MRR-targets in plants. Thus, what exactly is being sensed in a dysfunctional mitochondrion and how this signal is transduced out of the mitochondria are important outstanding questions in the field.

Despite, the dominance of ANAC017 in the current literature of plant MRR, it is very likely that other mito-nuclear signalling pathways also exist. For instance, most mitochondrial function mutants in Arabidopsis have specific transcriptomic responses outside of the ANAC017 target genes [145,153,176,177]. ANAC017 also affected approximately 35% of the transcriptomic response to AA [152], suggesting that other signalling pathways were activated. Interestingly, a study in this issue provides evidence using chemical and genetic approaches that simultaneous inhibition of Complex IV and alternative oxidase results in a downregulation of chloroplast transcription [175]. This inhibition was achieved by silencing of rps10 (mitoribosomal subunit 10) and simultaneous mutation of dual-targeted organellar RNA polymerase rpotmp and aox1a, or by specific chemical inhibition using KCN and salicylhydroxamic acid. Although the ANAC017 pathway is also activated under these conditions, the downregulation of chloroplast transcription appears to be independent of ANAC017 and may operate at least in part via downregulation of nuclear-encoded components of the chloroplast transcriptional machinery. This implies the existence of an unknown signalling pathway that connects mito-nuclear signalling with chloroplast function. Again, this effect could be observed during low oxygen stress, which would indeed simultaneously inhibit Complex IV and alternative oxidase, providing more evidence that plant MRR is particularly relevant during hypoxia.

8. Common principles in retrograde control from organelles

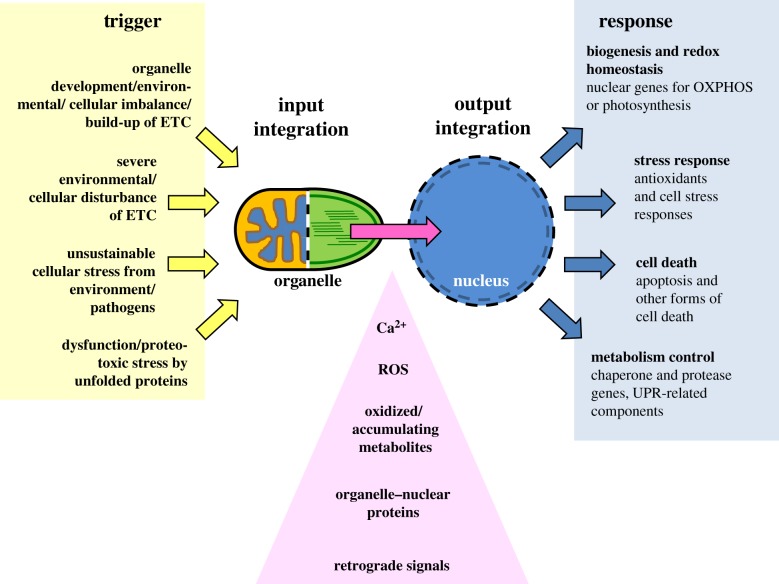

The previous sections have demonstrated the multiplicity of mechanisms that are used by retrograde signalling pathways from both organelles. At the molecular level, these pathways may exhibit numerous species-specific as well as condition-specific differences. Nevertheless, because of their evolutionary and functional relatedness some conserved regulatory paradigms can be identified for both organelles that appear within the same biological context and follow similar or even identical rules (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Common principles in retrograde signalling of eukaryotic organelles. The diagram depicts four major biological triggers (indicated in the left panel) in which mitochondria and chloroplasts (represented by head-to-head orange and green ovals as a combined symbol) initiate retrograde signal classes with high similarity in signal identity (pink triangle), gene target and cellular response (depicted in the right panel). Organelles detect and integrate external or cellular triggers (yellow arrows, input integration), and produce the corresponding retrograde signal(s) (pink arrow) that is/are detected by the nucleus, where the information is finally integrated to initiate a corresponding response (blue arrows, output integration). ETC, electron transport chain; ROS, reactive oxygen species; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; UPR, unfolded protein response.

(a). Retrograde signals in biogenesis, redox homeostasis and stress conditions

Mitochondria and chloroplasts are the energy-converting organelles of eukaryotic cells and work closely together either directly, as in autotrophs, or indirectly via the food chain in heterotrophs. The photosynthesis-driven carbon reduction of chloroplasts and the corresponding carbon oxidation in mitochondria thus provide the essential energetic cycle that drives eukaryotic life on Earth. Imbalances and disturbances in the ETCs of both organelles are typically reflected by changes in the redox state of electron transport components and/or increasing amounts of ROS, and in both cases these trigger a number of stress responses that aim to counter-balance adverse influences from the environment or metabolism in order to re-establish redox homeostasis. For both organelles, therefore, a strong coordination in the expression of components of their ETCs is of vital importance.

Interestingly, for both organelles, the vast majority of ETC components are encoded in the nucleus and their expression is under the control of only a few key regulators. In mitochondria (of heterotrophs) expression of nuclear genes for mitochondrial complexes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial gene expression and protein import is predominantly under the control of nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) and the purine-rich repeat GA-binding protein α (GABPα) [178–181]. A similar situation is found for plastids where PhANGs are under the control of Golden2-like 1 and 2 (GLK1 and GLK2), two key transcription factors required for building the photosynthesis apparatus [182,183]. These key regulators are targets for retrograde signals from mitochondria or plastids, respectively, allowing the coordinated expression of ETC components according to the needs of the respective organelles. These pathways are activated in particular when biogenesis of new plastids and mitochondria is required. This is typical in developing tissues (meristems in plants) of young organisms that are growing.

Furthermore, retrograde signalling pathways are activated under particular environmental conditions that generate an imbalance in the ETCs. By this means the redox state of the components involved in the electron transport may serve as a signal that activates and initiates corresponding molecular responses. Thus, the functioning of the ETC in both organelles acts as an environmental sensor that triggers compensatory cellular responses. Conditions that induce an ETC dysfunction or excessive electron flow through ETCs result in the formation of ROS or oxidized metabolites or compounds. Both organelles induce a whole array of responses which mainly focus on stress compensation and maintenance of redox homeostasis. However, when the stress reaches a level that cannot be compensated for, cells may induce cell death in order to ensure the survival of the organism. For mitochondria in heterotrophs, a number of different scenarios are known in which the organelle initiates a subsequent cell death (apoptosis), usually through the release of cytochrome c [184]. In autotrophs, the scenario is more complex since besides mitochondria plastids also play an important role in cell death initiation (see above) [185].

(b). Proteostasis and maintenance of metabolism

Besides their role in energy metabolism, mitochondria and plastids have critical functions in the catabolic and anabolic reactions of most biosynthetic pathways of eukaryotic cells. Both organelles, therefore, represent metabolic hubs in primary and secondary metabolism. Since the organellar genomes encode almost exclusively components of ETCs and the gene expression machineries, virtually all enzymes for biosynthetic pathways must be imported from the cytosol and assembled in the matrix and stroma, respectively [26,186]. In the context of a balanced metabolism in organelles, a striking similarity in retrograde control appears to be the various types of UPR that resolve proteotoxic stresses by removing unassembled, unfolded, unimported or damaged proteins. The UPRmt of heterotrophs is already well understood and is known to maintain various important cellular parameters, including matrix homeostasis/proteostasis to balance the metabolism. It is only recently that a corresponding plastid UPR (UPRcp) could be identified [65,187,188]. As in mitochondria, unbalanced or repressed protein production induces a proteotoxic stress that sends retrograde signals to the nucleus to enhance the expression of a number of chaperones and proteases. Indeed, recent evidence has suggested that UPRcp may be important for biogenic signalling mediated by GUN1 [53,67]. Here GUN1 is implicated in a role in chloroplast protein import, but how this links in with the other known functions of GUN1 is still unknown (see earlier discussion). Interestingly, severe chloroplast stress resulting in 1O2 production has also identified a possible additional route for removal of damaged organelles, in this case through a ubiquitin-mediated system that acts independently of autophagy [109].

9. The nature of retrograde signals

Retrograde signalling from mitochondria and plastids displays many commonalities not only in the physiological and developmental context in which it is acting, but also in the physical nature of signalling molecules that actually pass through the envelopes of the two types of organelles. Despite manifold species-specific differences, one can identify four classes of signals used by all organelles.

(a). Calcium ions

In mitochondria of heterotrophic organisms, Ca2+-driven retrograde signalling is well established and studied. Release of Ca2+ ions from mitochondria in response to various stressors is known to affect the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and to constitute a trigger for the expression of enzymes involved in the re-establishment of Ca2+ balance, carbohydrate metabolism and cell proliferation [43]. In mitochondria of autotrophs, this is still under investigation, but an involvement in retrograde signalling is very likely [189]. In plastids, recent studies have uncovered that plastidial Ca2+ metabolism is tightly linked to the cytosolic Ca2+ balance via the plastid localized calcium sensing protein. Apparently, plastid Ca2+ release is required for a number of cellular responses that control photosynthetic efficiency and stress acclimation [190,191].

(b). ROS and oxidized metabolites

As discussed above, energy conversion is one central function of plastids and mitochondria. Imbalances or dysfunctions in their ETCs result in both organelles in the formation of ROS and other oxidized compounds that provide either the trigger or the signal itself for retrograde control. The redox chemistry that is involved displays many commonalities between both organelles and ROS represent a dominant class of retrograde signals in both cases as they aim to achieve redox homeostasis.

(c). Organelle-specific metabolites

Plastids and mitochondria are essential metabolic hubs of eukaryotic cells and contribute to many anabolic and catabolic reactions of the cell. The well-known exchange of substrates and products across the envelope generates genuine and natural retrograde signals that couple organellar and cytosolic functions via envelope-localized transporters as discussed by a contribution to this issue [92]. Metabolite fluxes have been known for a long time to be important for metabolic homeostasis and stress responses in eukaryotic cells. How far changes in specific metabolites and changes in metabolite signatures (representing combinations of fluxes of several metabolites) serve as signals is still under investigation. Another interesting example is the tetrapyrrole haem, which is synthesized in plastids or, for yeast and mammals, in mitochondria (although intermediate steps occur in the cytoplasm). As discussed earlier, haem is a major candidate as the signalling molecule for biogenic retrograde signalling and is well established as a regulator of gene expression, including for mitochondrial proteins, in yeast and mammals [33].

(d). Dual-localized proteins

Nuclear-encoded proteins that target organelles and re-locate to the nucleus under specific conditions are a fascinating new field of research in retrograde signalling. This type of protein occurs in both mitochondria and plastids and is discussed in two contributions to this issue. While in mitochondria the mode of retrograde re-location is well investigated, it is still under extensive debate in plastids and further research is required to resolve apparent contradictions [70,86]. Nevertheless, redirection of plastid proteins to the nucleus that potentially act as transcription factors provides a very direct mechanism for retrograde control that does not require further mediators.

10. Conclusion

Present plastids and mitochondria are essential compartments of eukaryotic cells and make a major contribution to their structural and functional properties. Despite many species-specific differences in specific properties that have appeared during evolution, a number of common paradigms can be clearly identified, which contributed to the establishment of multicellular organisms. Retrograde signals from the two types of organelles play an important role in cellular responses to developmental and environmental influences. Across all eukaryotic evolutionary lines, a number of common principles can be identified which most likely represent the common evolutionary constraints imposed regardless of specific effects on the evolution of single species. The establishment of retrograde signalling pathways, therefore, appears to be located at the root of eukaryotic cell evolution.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

T.P. designed the topical structure of the article, wrote the general parts and the section about operational signals, and designed the figures. M.J.T. wrote the section about biogenic signals. O.V.A. wrote the section about mitochondrial signals in autotrophs. P.M.Q. wrote the section about mitochondrial signals in heterotrophs and provided data for table 1. All authors discussed the content of the complete article, contributed to proofreading and revision and agree with the content. M.J.T. revised the language style.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We received no funding for this study.

References

- 1.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. 1990. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4576–4579. ( 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier I, Richards EJ, Evans DE. 2017. Cell biology of the plant nucleus. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, 139–172. ( 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-041115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diekmann Y, Pereira-Leal JB. 2013. Evolution of intracellular compartmentalization. Biochem. J. 449, 319–331. ( 10.1042/BJ20120957) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen S, Valm AM, Lippincott-Schwartz J. 2018. Interacting organelles. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 53, 84–91. ( 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.06.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen JF. 2015. Why chloroplasts and mitochondria retain their own genomes and genetic systems: colocation for redox regulation of gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10 231–10 238. ( 10.1073/pnas.1500012112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyke K. 2007. Plastid biogenesis and differentiation. In Cell and molecular biology of plastids, vol. 19 (ed. Bock R.), pp. 1–28. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archibald JM. 2015. Endosymbiosis and eukaryotic cell evolution. Curr. Biol. 25, R911–R921. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyke KA. 2010. Plastid division. AoB Plants 2010, plq016 ( 10.1093/aobpla/plq016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin WF, Garg S, Zimorski V. 2015. Endosymbiotic theories for eukaryote origin. Phil. Trans. R Soc. B 370, 20140330 ( 10.1098/rstb.2014.0330) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imachi H, et al. 2020. Isolation of an archeon at the prokaryote–eukaryote interface. Nature 577, 519–525. ( 10.1038/s41586-019-1916-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martijn J, Vosseberg J, Guy L, Offre P, Ettema TJG. 2018. Deep mitochndrial origin outside the sampled alphaproteobacteria. Nature 557, 101–105. ( 10.1038/s41586-018-0059-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parfrey LW, Lahr DJ, Knoll AH, Katz LA. 2011. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13 624–13 629. ( 10.1073/pnas.1110633108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W. 2004. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 123–135. ( 10.1038/nrg1271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin W, et al. 2002. Evolutionary analysis of Arabidopsis, cyanobacterial, and chloroplast genomes reveals plastid phylogeny and thousands of cyanobacterial genes in the nucleus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12 246–12 251. ( 10.1073/pnas.182432999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Björkholm P, Harish A, Hagström E, Ernst AM, Andersson SGE. 2015. Mitochondrial genomes are retained by selective constraints on protein targeting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10 154–10 161. ( 10.1073/pnas.1421372112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen JF. 2017. The CoRR hypothesis for genes in organelles. J. Theor. Biol. 434, 50–57. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.04.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Heijne G. 1986. Why mitochondria need a genome. FEBS Lett. 198, 1–4. ( 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81172-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CP, Eubel H, Solheim C, Millar AH. 2012. Mitochondrial proteome heterogeneity between tissues from the vegetative and reproductive stages of Arabidopsis thaliana development. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3326–3343. ( 10.1021/pr3001157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prokisch H, et al. 2004. Integrative analysis of the mitochondrial proteome in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2, e160 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020160) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]