Abstract

Mitochondrial membrane biogenesis requires the import of phospholipids; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying this process remain elusive. Recent work has implicated membrane contact sites between the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and vacuole in phospholipid transport. Utilizing a genetic approach focused on these membrane contact site proteins, we have discovered a ‘moonlighting’ role of the membrane contact site and vesicular fusion protein, Vps39, in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) transport to the mitochondria. We show that the deletion of Vps39 prevents ethanolamine-stimulated elevation of mitochondrial PE levels without affecting PE biosynthesis in the ER or its transport to other sub-cellular organelles. The loss of Vps39 did not alter the levels of other mitochondrial phospholipids that are biosynthesized ex situ, implying a PE-specific role of Vps39. The abundance of Vps39 and its recruitment to the mitochondria and the ER is dependent on PE levels in each of these organelles, directly implicating Vps39 in the PE transport process. Deletion of essential subunits of Vps39-containing complexes, vCLAMP and HOPS, did not abrogate ethanolamine-stimulated PE elevation in the mitochondria, suggesting an independent role of Vps39 in intracellular PE trafficking. Our work thus identifies Vps39 as a novel player in ethanolamine-stimulated PE transport to the mitochondria.

Keywords: Phospholipid transport, Mitochondria, Phosphatidylethanolamine, vCLAMP, HOPS, Vps39

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial membrane biogenesis requires coordinated import and synthesis of proteins as well as phospholipids, the major lipid constituents of mitochondrial membranes [1]. The molecular machineries required for mitochondrial protein import have been studied in great detail [2]; however, the molecular mechanism(s) by which phospholipids are transported to the mitochondria have remained elusive [3–5]. While phospholipid movement between the organelles of the endomembrane system can occur via vesicles, mitochondria are not part of the vesicular transport system. This raises an intriguing question – how do mitochondria acquire phospholipids? A number of non-vesicular lipid trafficking mechanisms such as inter-organelle phospholipid transfer proteins have been proposed [5–7], but the contribution of these mechanisms to phospholipid transport to the mitochondria is not fully understood [8].

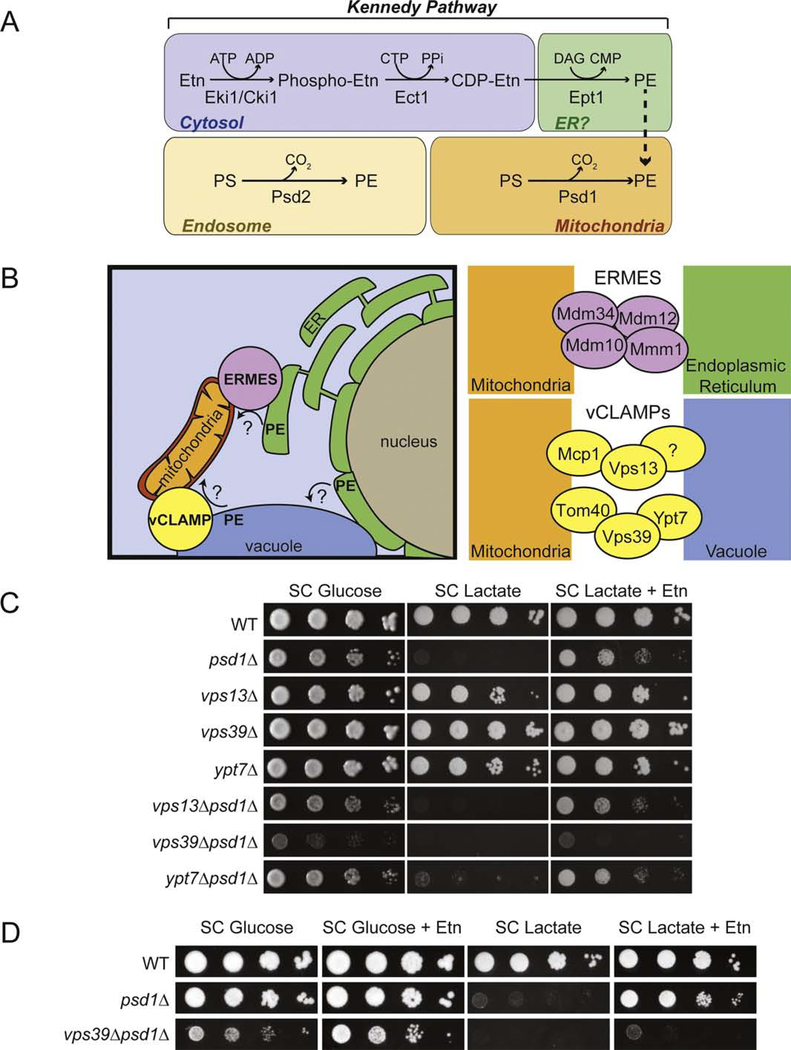

Mitochondria contain all the major classes of phospholipids, a majority of which are synthesized in the ER [9]. One of the key phospholipids required for mitochondrial respiratory function is phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) [10–12], which in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is synthesized via three main pathways that are localized to different sub-cellular compartments (Fig. 1A). Decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine (PS) either by Psd1 in the mitochondria or by Psd2 in the endosomal compartment generates PE [13–16]. PE can also be synthesized de novo from ethanolamine (Etn) through the cytidine diphosphate (CDP)-Etn Kennedy pathway via the sequential action of the enzymes Eki1, Ect1, and Ept1 (Fig. 1A) [17]. In wild type (WT) yeast cells, Psd1-derived PE is the major source of mitochondrial and cellular PE [18]; however, PE synthesized via the Kennedy pathway can also be imported into the mitochondria, where it can functionally compensate for the loss of mitochondrial PE biosynthesis [10,19]. This finding implies that mitochondrial PE transport machinery must exist; however, its identity has remained unknown.

Fig. 1. Utilizing Etn-supplementing strategy to identify proteins required for PE transport to the mitochondria.

(A) Major phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthetic pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (B) Schematic representation of two membrane contact sites, ERMES and vCLAMP, connecting mitochondria with ER and vacuole, respectively. ERMES consists of Mdm34, Mdm12, Mdm10, and Mmm1. vCLAMPs consist of two independent complexes, one consisting of Vps39, Ypt7, Tom40 and the second consisting of Vps13, Mcp1, and an unknown vacuole anchor protein. (C) Ten-fold serial dilution of the indicated yeast mutants were seeded onto synthetic complete (SC) Glucose and SC Lactate ± Etn plates. Images were captured after 2d (SC Glucose media) and 5d (SC Lactate media) of growth at 30 °C. (D) WT, psd1Δ, and vps39Δpsd1Δ were seeded onto SC Glucose ± Etn and SC Lactate ± Etn plates and imaged after 2d and 5d of growth at 30 °C, respectively. The figures are representative images of three independent biological replicates. PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; Etn, ethanolamine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate, ADP, adenosine diphosphate; CTP, cytidine triphosphate; CDP, cytidine diphosphate; CMP, cytidine monophosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; PPi, pyrophosphate; ERMES, endoplasmic reticulum mitochondria encounter structure; vCLAMP, vacuole and mitochondria patch.

New evidence [20–24] suggests that membrane contact sites (MCSs), regions of close apposition of organelle membranes, play an important role in the transport of phospholipids between organelles [25,26]. Two mitochondrial MCSs directly implicated in phospholipid transport are Endoplasmic Reticulum Mitochondria Encounter Structure (ERMES), a protein complex that tethers the ER and mitochondria, and Vacuole and Mitochondria Patch (vCLAMP), which connects the vacuole to mitochondria (Fig. 1B) [27–29]. Recent structural studies documenting the presence of phospholipid-binding hydrophobic pockets in the subunits of ERMES and vCLAMP further supports a direct role of these MCS’s in inter-organelle phospholipid transport [20–24]. Previously, we had explored the role of ERMES in the transport of the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway PE to the mitochondria and found that although ERMES facilitated the efficient Etn-mediated rescue of respiratory growth of mitochondrial PE-deficient psd1Δ cells, ERMES was not essential for PE transport [10]. Consistently, the phospholipid transport tunnel formed by the ERMES components, Mdm12-Mmm1 does not bind PE in vitro [24]. Recently, it has been shown that vCLAMP can serve as an alternate route for phospholipid transport from the ER to the mitochondria via the vacuole [28]. Therefore, in this report, we explored the role of vCLAMP in the transport of PE to the mitochondria and demonstrate that Vps39, a vCLAMP subunit, has a critical role in Etn-stimulated trafficking of PE from the ER to the mitochondria.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Yeast strains, growth medium composition, and culture conditions

Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in the study are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were routinely maintained and pre-cultured in YPGE medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 3% glycerol, and 1% ethanol) to prevent the loss of mitochondrial DNA from psd1Δ cells. In the cases where cells cannot grow in YPGE medium or wherever indicated, the pre-cultures were prepared in the YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose). To allow for efficient incorporation of Etn in PE, yeasts were grown in synthetic complete (SC) medium, which contained 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 0.2% dropout mix containing amino acids, and either 2% glucose or 2% lactate (pH 5.5) [30]. Final cultures were started at an optical density (OD600) of 0.1 and were grown to late logarithmic phase at 30 °C. Solid media were prepared by the addition of 2% agar. For measuring growth on solid media, 3 μL of 10-fold serial dilutions of pre-cultures were seeded onto SC Glucose or SC Lactate plates and incubated at 30 °C for the indicated times. For Etn supplementation experiments, 2 mM Etn was added to SC growth medium. Petite formation was determined by spreading 100 μL of SC Glucosegrown cells (~200 cells) onto YPD and YPGE plates. The percent of petite colonies was determined by counting the number of colonies in each of these growth media. Single and double knockout yeast strains were constructed by one-step gene disruption using geneticin, hygromycin, and nourseothricin cassettes [31].

Table 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study.

| Yeast strains | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 WT | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0 | Miriam L. Greenberg |

| BY4741 psd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, psd1::hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 vps39Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps39::KanMX4 | Open biosystems |

| BY4741 vps13Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps13::KanMX4 | Open biosystems |

| BY4741 ypt7Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, ypt7::KanMX4 | Open biosystems |

| BY4741 vps41Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps41::KanMX4 | Open biosystems |

| BY4741 vps11Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps11::KanMX4 | This study |

| BY4741 vps33Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps33::KanMX4 | This study |

| BY4741 vps39Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps39::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 vps13Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps13::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 ypt7Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, ypt7::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 vps41Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps41::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 vps11Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps11::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| BY4741 vps33Δpsd1Δ | MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, vps33::KanMX4, psd1:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CUY8994 GFP-Vps39 | MATalpha, leu2-3, leu2-112, ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ101, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, GAL, VPS39 ClonNAT-TEFpr-GFP, SHM1 3xmCherry-HIS3 | Christian Ungermann |

| CUY8992 GFP-Vps41 | MATalpha, leu2-3, leu2-112, ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ101, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, GAL, VPS41 ClonNAT-TEFpr-GFP, SHM1 3xmCherry-HIS3 | Christian Ungermann |

| CUY8994 GFP-Vps39 psd1Δ | MATalpha, leu2-3, leu2-112, ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ101, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, GAL, VPS39 ClonNAT-TEFpr-GFP, SHM1 3xmCherry-HIS3, psd1::hphMX4 | This study |

| CUY8992 GFP-Vps41 psd1Δ | MATalpha, leu2-3, leu2-112, ura3-52, his3-Δ200, trp1-Δ101, lys2-801, suc2-Δ9, GAL, VPS41 ClonNAT-TEFpr-GFP, SHM1 3xmCherry-HIS3, psd1::hphMX4 | This study |

2.2. Plasmids and molecular biology

All plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. VPS39 constructs were engineered as follows: the full-length VPS39 insert was generated by PCR amplification of yeast genomic DNA with primer pair 5/6. Vps39 431–1049, 531–1049, 1–860, 1–980 truncations were generated with primer pairs 9/6, 10/6, 11/5, and 12/5 respectively. The VPS39 promoter region and 6xHis2xHA tag were amplified by PCR using primer pairs 1/2 and 3/4, respectively. Full length VPS39 and each of the VPS39 truncation PCR products were digested with the restriction enzymes MluI/BamHI. The DNA fragments encoding 6xHis2xHA and VPS39 promoter were digested with XbaI/MluI and SacI/XbaI, respectively. Each plasmid containing a full-length or a truncated version of VPS39 was constructed by ligation of SacI/BamHI digested pRS416 and the abovementioned digested DNA fragments. The Ept1 insert was generated by PCR amplification of genomic DNA with primer pair 7/8. The Ept1 insert and pRS426 containing V5-epitope encoding sequence were digested with SacI/XhoI and ligated. All constructs were sequence verified.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Source |

|---|---|

| pRS416 | Craig D. Kaplan |

| pRS426 | Craig D. Kaplan |

| pRS426 Ept1-V5 (contains endogenous Ept1 promoter) | This study |

| pRS416 6xHis2xHA-Vps39 (contains endogenous Vps39 promoter) | This study |

| pRS416 6xHis2xHA-Vps39 431–1049 aa (contains endogenous Vps39 promoter) | This study |

| pRS416 6xHis2xHA-Vps39 531–1049 aa (contains endogenous Vps39 promoter) | This study |

| pRS416 6xHis2xHA-Vps39 1–860 aa (contains endogenous Vps39 promoter) | This study |

| pRS416 6xHis2xHA-Vps39 1–980 aa (contains endogenous Vps39 promoter) | This study |

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Oligonucleotide number | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| 1 | CCCTCCGAGCTCAACCTTAGTTGGCGCCATGTGTGTA |

| 2 | CCCCATTCTAGACATTTAATTTTTGGTATAAATTGATATT |

| 3 | CCGCGGTGGCGGCCGCTCTAGAACT |

| 4 | CCCATGACGCGTAGCGTAGTCTGGGAC |

| 5 | CCCTAAACGCGTTTAAGAGCTCAAAAGCTACACT |

| 6 | CCCATCGGATCCTTACTTATTATTTAGCTCATTTATA |

| 7 | CCCGTTGAGCTCAGTGACTTGTAAGTAAACGG |

| 8 | CCCTTACTCGAGTGTCAGCTTGGAGCGCTTGAT |

| 9 | CCCTAAACGCGTGAAGAATCCTTGGATATATGTGCTATG |

| 10 | CCCTAAACGCGTGAAACTTATGACATCCCGCCACACTTA |

| 11 | CCCATCGGATCCATCTATCTCATCAAGTAATATATGCACAGC |

| 12 | CCCATCGGATCCTGATAAGACTCCATACGATGACATGCGTTC |

2.3. Organelle isolation

2.3.1. Mitochondria

Isolation of crude and pure mitochondria was performed as previously described [32]. Yeast cells grown to late logarithmic phase were pelleted (1–5 g wet weight depending upon the intended use) and resuspended in DTT buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.4, 10 mM DTT) for 20 min at 30 °C. The cells in DTT buffer were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 ×g for 5 min and were resuspended in spheroplasting buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4) and treated with 3 mg zymolyase (US Biological Life Sciences) per gram of cell pellet for 45 min at 30 °C. Spheroplasts were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 5 min and were homogenized in homogenization buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF [Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride], 0.2% [w/v] BSA [essentially fatty acid-free, Sigma-Aldrich]) with 15 strokes using a glass teflon homogenizer. After two subsequent centrifugation steps for 5 min at 1500 ×g and 4000 ×g, the final supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min to pellet mitochondria. Crude mitochondrial fractions were resuspended in SEM buffer (250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2) and diluted to a protein concentration of 5 mg/mL. The diluted mitochondria are loaded on top of a step sucrose gradient, which consists of 15%, 23%, 32%, and 60% (w/v) sucrose in EM buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2) from top to bottom. The gradient is centrifuged for 1 h at 134,000 ×g at 4 °C. Pure mitochondria were collected at the 32% to 60% sucrose interface, diluted with SEM buffer, and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min. Pellets were resuspended in small volume of (~50 to 200 μL) SEM buffer and protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay, Catalog number: 23225).

2.3.2. ER

Isolation of pure ER was performed as described previously [33]. As described in the above section, 1–5 g of yeast cells was spheroplasted with zymolyase and lysed with a homogenizer. After two subsequent centrifugation steps for 5 min at 1500 ×g and 4000 ×g, the final supernatant was centrifuged at 27,000 ×g for 15 min to pellet the crude ER fraction. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μL HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES/KOH pH 6.8, 50 mM potassium acetate, 100 mM sorbitol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF). The crude ER fraction is loaded on top of a step-sucrose gradient consisting of two steps: 1.2 M sucrose above 1.5 M sucrose in HEPES buffer. The gradient was centrifuged at 100,000 ×g for 1 h at 4 °C. Pure ER fraction was collected in the interface of 1.2 M/1.5 M sucrose gradient, diluted 10-fold in HEPES buffer and centrifuged at 27,000 ×g for 10 min. The purified ER fraction was resuspended in HEPES buffer and protein concentration was determined by BCA assay.

2.3.3. Vacuole

Isolation of pure vacuole was performed as previously described [34]. Yeast spheroplasts were pelleted at 3000 ×g at 4 °C for 5 min. Dextran-mediated spheroplast lysis of 2.5–5 g of yeast cells was performed by gently resuspending the pellet in 2.5 mL of 15% (w/v) Ficoll400 in Ficoll Buffer (10 mM PIPES/KOH pH 6.8, 200 mM sorbitol, protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1 mM PMSF) on ice. 200 μL of 0.4 mg/ mL dextran in Ficoll buffer was added to the spheroplasts and was incubated for 2 min on ice. Spheroplasts were lysed by heating at 30 °C for 75 s and returned to ice. A step-ficoll gradient was constructed on top of the lysate with 3 mL each of 8%, 4%, and 0% (w/v) Ficoll400 in Ficoll Buffer. The step-gradient was centrifuged at 110,000 ×g for 90 min at 4 °C. Vacuoles were removed from the 0%/4% Ficoll interface and protein concentration was determined by the BCA assay.

2.4. Phospholipid extraction

Phospholipids were extracted by a modified Folch method [35]. For cellular phospholipid extraction, 1 g (wet weight) of yeast cells were digested with zymolyase and the spheroplasts, thus obtained, were diluted with 20× the volume of Folch solution (2:1 chloroform:methanol) in a glass tube and shaken vigorously for an hour. Water equivalent to 1/5 the volume of Folch solution was added and shaken vigorously for 1 min followed by centrifugation at 1000 ×g for 2 min to yield a top aqueous phase and a bottom organic phase containing lipids. The bottom phase was transferred to a fresh glass tube to which 1:1 methanol:water equivalent of 1/5 the volume of lipid solution was added and shaken vigorously for 1 min. The tube was centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 2 min. The bottom phase was again transferred to a fresh tube and dried with N2. The lipids dried in the glass tube were resuspended in chloroform (~100 μL). Bartlett quantification was used to measure total phospholipid phosphorus. Mitochondrial phospholipid extraction was performed using the same procedure.

2.5. Phospholipid separation and quantification

2.5.1. 1-D thin layer chromatography

The thin layer chromatography (TLC) plate (HPTLC Silica gel 60 F254 AMD extra thin, Merck, HX381899) was prepared by soaking in 1.8% boric acid in ethanol and dried at 110 °C. Extracted phospholipids corresponding to 50 nmol phosphate (as determined by Bartlett method) was loaded to the plate in evenly spaced lanes using a 50 μL Hamilton syringe. The tank was equilibrated with a 51.5 mL of solvent consisting of 25:25:1.5 chloroform:methanol:ammonium hydroxide. To equilibrate the TLC tank with the solvent system, a filter paper was placed vertically into the tank, followed by the phospholipid-loaded TLC plate. The TLC plate was removed from the tank when the solvent front reached the top of the plate (~45 min) and was air-dried for 30 min. To visualize the lipids, the plate was soaked in copper staining solution (7.5% CuSO4 and 8.5% ortho-phosphoric acid) and charred at 180 °C. The plate was scanned and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software. Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test.

2.5.2. 2-D thin layer chromatography

This method was performed as previously described [10]. The extracted phospholipids (15–50 μL) were spotted in a drop-by-drop fashion on the bottom left corner, 1-inch from each side, on a TLC plate (Merck TLC Silica gel 60 HX69032853). To separate phospholipids in the first dimension, a solvent system consisting of 32.5:17.5:2.5 chloroform:methanol:ammonium hydroxide was used. After ~45 min of TLC run time, the plate was taken out from the tank and air dried for 30 min. To separate the phospholipids in the second dimension (perpendicular to the first dimension), the plate was placed in a separate TLC tank containing 37.5:12.5:2.5:1.1 chloroform:acetic acid:methanol:water. The solvent front was run to the top and air dried for another 30 min. Phospholipids were visualized by placing the dried plate in a TLC tank containing iodine. The phospholipids spots were marked with pencil and scraped using a razor blade, and silica from each spot is collected into glass tube for phosphorus quantification by the Bartlett method.

2.5.3. Bartlett assay

To quantify phospholipid phosphorus, the phospholipid samples were digested in 400 μL of 72% perchloric acid on a 160 °C heat block. After overnight digestion, 4 mL of water was added to each tube followed by the addition of 200 μL of 5% (w/v) ammonium molybdate. The tubes were vortexed and 200 μL of 1% (w/v) amidol in 20% (w/v) sodium bisulfite was added and mixed by vortexing. The glass tubes were then placed in a boiling water bath for 10 min. The light blue color indicating phosphorus is quantified by taking optical density measurement at 830 nm. In order to quantify the absolute amount of phosphorus in each of the samples, a standard curve was obtained by using KH2PO4 standard solution in the 0.5–10 μg of phosphorus range.

2.6. Sub-mitochondrial localization

2.6.1. Proteinase K protection assay

The assay was performed as previously described [36]. 20 μL of 5 μg/μL mitochondria was added to 180 μL of SEM. The diluted mitochondria were split into two tubes. One tube was treated with 5.26 μL of 1 mg/mL proteinase K in SEM and the other with an equivalent volume of SEM. The tubes were incubated on ice for 15 min and the reaction was stopped by adding 1.063 μL 200 mM PMSF. Proteins were precipitated by adding 1/5 the sample volume of 72% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The samples were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 18,000 ×g for 30 min at 4 °C. The TCA was gently aspirated, and the pellet was washed with 500 μL of acetone. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μL acetone and air-dried. The dried pellet was resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by western blotting.

2.6.2. High salt extraction

The assay was performed as previously described [37]. 125 μL of 30 μg/μL mitochondria was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and an equivalent volume of SM1 buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM HEPES KOH pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 1 M NaCl) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics 11836170001) was added to the mitochondria. The mitochondria were incubated on ice for 15 min and pelleted by centrifugation at 12000 ×g. The supernatant was collected in a fresh tube and the pellet was resuspended with SEM. The protein concentration was determined in both the pellet and supernatant fractions and no > 150 μg of each fraction was aliquoted into fresh tubes. Both fractions were brought to an equal volume (~300 μL) by adding SEM, followed by TCA precipitation and acetone wash as described in the previous section. The pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/western blot.

2.7. Image acquisition and analysis

For quantitative fluorescent microscopy, imaging was performed on an inverted Nikon Eclipse-Ti microscope with a 100 × 1.49 NA TIRF objective, and the images were collected using a Hamamatsu ImagEM X2™ EMCCD camera C9100–23B (effective pixel size, 160 nm). GFP-Vps39 psd1Δ cells cultured with and without Etn supplementation were imaged using a 488-nm laser (0.2 kW/cm2) and a 561-nm laser (0.2 kW/cm2) to visualize GFP-Vps39 and mCherry-labelled mitochondria, respectively. To determine the overlap in signal from the GFP and the mCherry, we calculated fractional overlap using a custom algorithm written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), which is available upon request. In the fluorescence images, we used 80% of maximum fluorescence intensity in each channel as the threshold to identify regions containing GFP-Vps39 or mCherry-labelled mitochondria. Based on the method described previously [38], we calculated the fractional overlap of GFP-Vps39 with the mitochondria by the ratio of the GFP-Vps39 co-localized with the mitochondria to the total GFP-Vps39 fluorescence signal. For higher resolution confocal microscopic images, samples were mounted on agarose pads and imaged using Olympus® FV1000 confocal microscope equipped with an UPLSAPO 100×/1.4 oil immersion objective with confocal pinhole size corresponding to 1 Airy unit. All images were taken using wavelengths as follows: GFP (Ex. 488 nm, Em. 500–530 nm), mCherry (Ex. 543 nm, Em. 565–615 nm) and processed to display a z-projection, pseudo-color, and the scale bar in ImageJ.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Graphpad prism software was used to determine the mean ± S.D. values from at least three biological replicates (which is defined as independent experiments performed on three different days each starting from a different clone). Statistical analyses were performed by unpaired Student’s t-test. The statistical significance is indicated by the p value in each figure.

3. Results

3.1. Vps39 is required for ethanolamine-mediated respiratory growth rescue of psd1Δ cells

Mitochondrial MCSs formed by the vCLAMP protein complexes has been implicated in inter-organellar phospholipid exchange [28]. Therefore, we decided to test the requirement of vCLAMP subunits in PE transport to the mitochondria. To this end, we utilized Etn auxotrophy of psd1Δ yeast cells. The assay is based on the observation that respiratory growth of psd1Δ cells, which lack mitochondrial PE biosynthesis, relies on the import of PE biosynthesized from exogenously supplemented Etn through the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway. We utilized this growth-based readout of mitochondrial PE import by constructing yeast deletion strains lacking vCLAMP subunits in a psd1Δ background. The inability of Etn to rescue respiratory growth of yeast cells lacking Psd1 and vCLAMP subunit(s) would suggest a role of these subunits in PE transport to the mitochondria. Using this experimental design, we tested the requirement of two recently identified vCLAMP complexes in PE transport to the mitochondria [39] (Fig. 1B, right panel). Deletion of Vps13, a key component of one vCLAMP complex, or deletion of Ypt7, an essential component of the second vCLAMP complex, did not abrogate Etn-mediated rescue, suggesting that intact vCLAMP complexes are not required for PE transport to the mitochondria (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, we found that the deletion of Vps39, a subunit of one of the vCLAMP complexes, led to a disruption in Etn-mediated rescue of psd1Δ cells (Fig. 1C). We also observed a growth defect of the vps39Δpsd1Δ mutant in fermentative (SC Glucose) conditions (Fig. 1C), indicative of a negative genetic interaction between these two genes in cellular processes that are independent of mitochondrial function (Fig. 1C). However, unlike the growth defect in respiratory medium (SC Lactate), the growth in glucose could be rescued by Etn supplementation, ruling out a role of Vps39 in Etn-mediated PE biosynthesis (Fig. 1D). Episomal expression of Vps39 in the vps39Δpsd1Δ double mutant could restore the Etn-mediated respiratory growth, demonstrating a Vps39-specific effect (Fig. S1). Collectively, these data show that Vps39 is specifically required for the Etn-mediated rescue of respiratory growth of psd1Δ cells.

3.2. Vps39 is required for ethanolamine-stimulated increase in mitochondrial PE levels

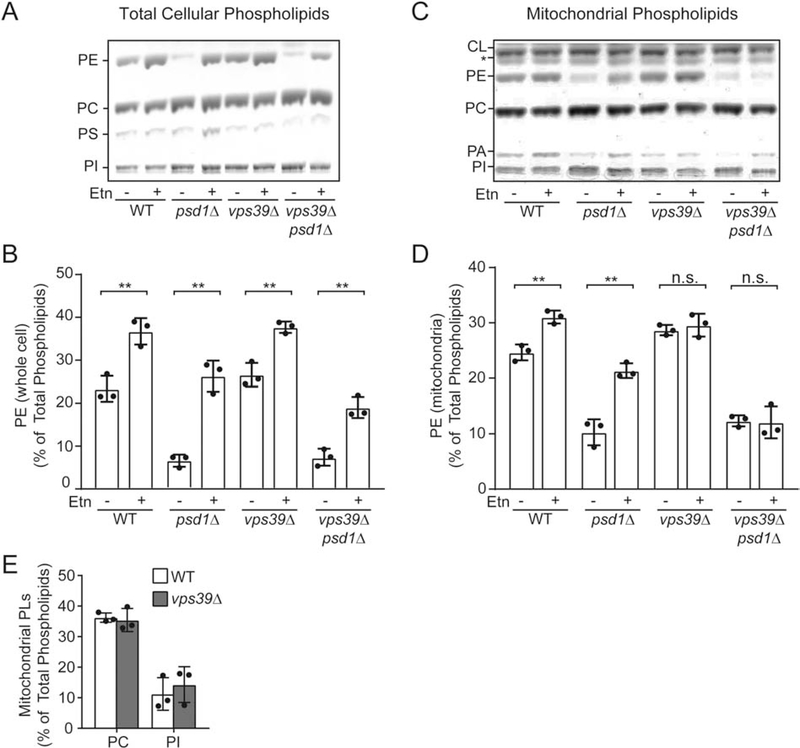

In order to test whether growth-based phenotypes correlate to PE levels, we measured the steady state levels of PE in yeast mutants grown in the presence or absence of Etn. Whole cell PE levels were increased upon Etn supplementation in vps39Δ cells, indicating that the CDP-Etn Kennedy Pathway is functional in a vps39Δ background (Fig. 2A and B). Next, we analyzed the mitochondrial phospholipid composition and observed no increase in mitochondrial PE levels upon Etn supplementation in cells lacking Vps39, suggesting that Vps39 is required for PE transport to the mitochondria (Fig. 2C and D). Notably, Etn supplementation did not fully restore mitochondrial PE levels of psd1Δ cells to that of Etn-supplemented WT cells (Fig. 2C and D). This could be due to the limiting amounts of Vps39 in cells. Therefore, we overexpressed Vps39 in psd1Δ cells supplied with Etn and found that mitochondrial PE levels were not increased upon Vps39 overexpression (Fig. S2), suggesting Vps39 abundance is not limiting in PE transport to the mitochondria. WT and vps39Δ mitochondria contained comparable steady state levels of other mitochondrial phospholipids that are imported from the ER, including phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) (Fig. 2E), suggesting a PE-specific role of Vps39 in phospholipid transport.

Fig. 2. Vps39 is required for Etn-stimulated PE elevation in the mitochondria.

(A) One dimensional-thin layer chromatography (1D-TLC)-based separation of phospholipids extracted from whole cells of the indicated yeast mutants cultured in SC Lactate ± Etn and (B) the quantification of relative PE levels from A by densitometry. (C) 1D-TLC of phospholipids extracted from density-gradient purified mitochondria from the indicated yeast mutants cultured in SC Lactate ± Etn and (D) the quantification of relative PE levels from C by densitometry. (E) Mitochondrial PC and PI levels of WT and vps39Δ cells grown in SC Lactate ± Etn from C. Phospholipid levels are expressed as the percent of total phospholipids. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n.s. not significant, (n = 3). Each data point represents a biological replicate. PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PA, phosphatidic acid; CL, cardiolipin, PL, phospholipids.

3.3. Vps39 is not required for ethanolamine-stimulated PE elevation in the ER and vacuole

Next, we asked whether the role of Vps39 in PE transport is specific to the mitochondria or is it required for PE transport to the other subcellular organelles. To test this idea, we purified ER and vacuole from WT and vps39Δ cells grown in the presence and absence of Etn and found that unlike in the mitochondria, Etn-supplementation led to an equivalent and significant increase in PE levels in the ER and vacuole in WT and vps39Δ cells (Fig. 3A and B). This result indicates that loss of Vps39 does not impair Etn-mediated elevation in the PE levels of the ER and vacuole.

Fig. 3. Vps39 is not required for Etn-stimulated PE elevation in the ER and vacuole.

PE levels of WT and vps39Δ cells grown in SC Lactate ± Etn in density-gradient purified (A) endoplasmic reticulum and (B) vacuole. PE levels are expressed as the percent of total phospholipid phosphorous. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, (n = 3). Each data point represents a biological replicate.

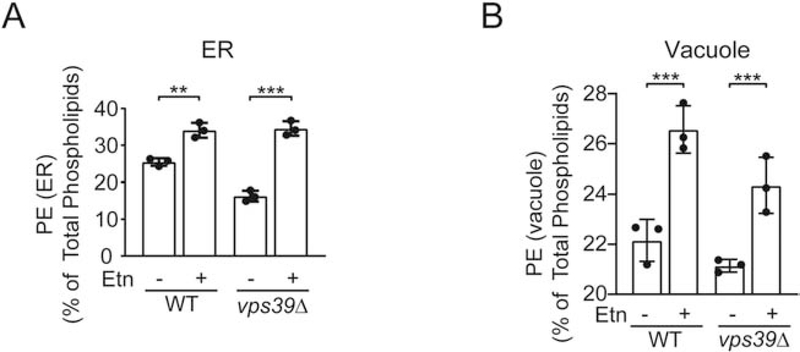

3.4. Vps39 is required for the rescue of PE-dependent mitochondrial functions

Mitochondrial PE is required for the maintenance of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is evident by the loss of mtDNA-encoded proteins and increased formation of petite colonies in psd1Δ cells that are cultured in fermentable medium [10,13,19]. Consistent with a previous study [10], Etn supplementation rescued both of these phenotypes in psd1Δ cells (Fig. 4A and B); however, deletion of Vps39 in psd1Δ cells abrogated Etn-mediated rescue of mtDNA-encoded Cox2 and Cox3 protein levels and petite formation (Fig. 4A and B). This data provides a functional read-out of PE levels in the inner mitochondrial membrane and further confirms the Vps39 requirement of CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway PE transport to the mitochondria.

Fig. 4. Vps39 is required for the expression and maintenance of mtDNA in Etn-supplemented psd1Δ cells.

(A) SDS-PAGE/western blot analysis of mtDNA-encoded proteins, Cox2 and Cox3, from mitochondria isolated from the indicated yeast mutants that were cultured in SC Glucose ± Etn media. Por1 is used as a loading control. (B) The percentage of respiratory deficient petite colonies of the indicated mutants cultured in SC Glucose ± Etn media. Percent petite colonies are calculated by counting the number of colonies grown in non-fermentable and fermentable media. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; ***p < 0.001, n.s. not significant, (n = 3). Each image is a representative of three independent experiments and each data point on bar charts represent a biological replicate.

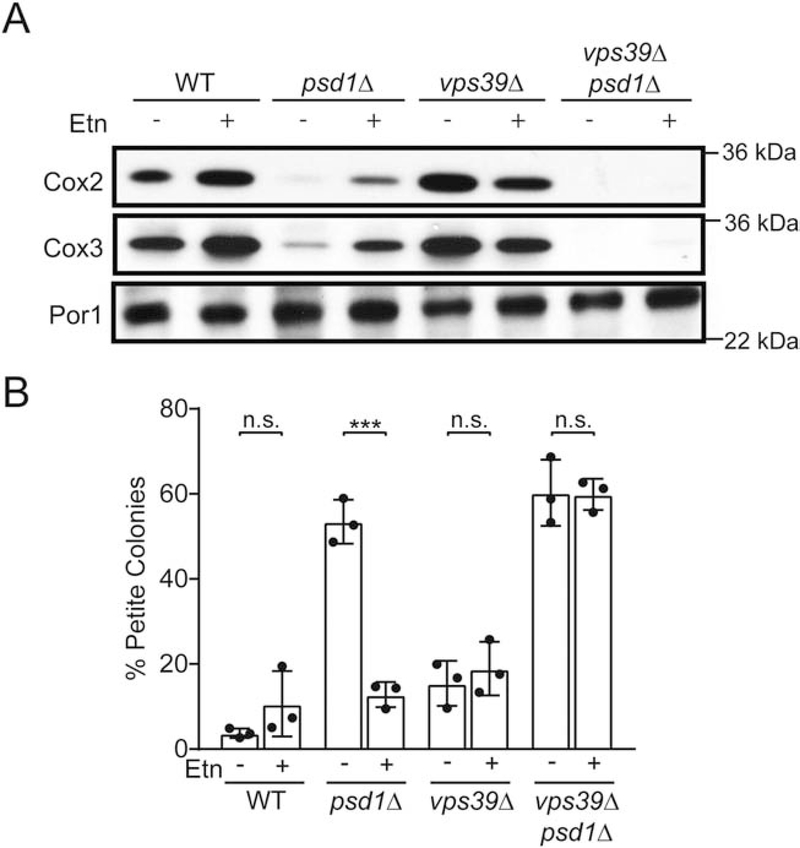

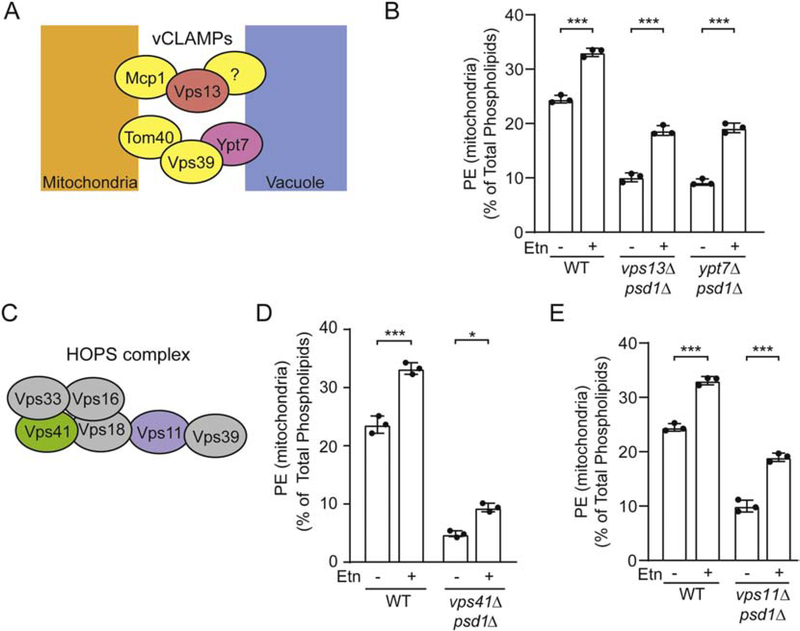

3.5. Vps39-dependent PE transport is independent of intact vCLAMP and HOPS complexes

Vps39 is part of two different protein complexes of separable function within the cell, vCLAMP and the homotypic fusion and protein sorting (HOPS) complex [39]. Therefore, Vps39 may facilitate PE transport to the mitochondria via its membrane tethering function as a component of vCLAMP or via a vesicular route as a component of the HOPS complex. To dissect the role of vCLAMP and HOPS in PE transport to the mitochondria, we investigated the requirement of other essential subunits of these complexes in the rescue of mitochondrial PE levels in Etn supplemented psd1Δ cells. We measured the mitochondrial PE levels in ypt7Δpsd1Δ and vps13Δpsd1Δ yeast strains that lack essential vCLAMP subunits (Fig. 5A), and found that Etn supplementation significantly increased mitochondrial PE levels in both of these mutants (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that intact vCLAMP complex is not required for PE transport to the mitochondria.

Fig. 5. PE transport to the mitochondria is independent of essential subunits of vCLAMP and HOPS complexes.

(A) A schematic of two vCLAMPs which consist of Vps39, Ypt7, Tom40 and Vps13, Mcp1, and an unknown vacuole anchor protein. (B) Density-gradient purified mitochondrial PE levels of WT, vps13Δpsd1Δ, and ypt7Δpsd1Δ cells grown in SC Glucose ± Etn. (C) A schematic of the HOPS complex which consists of six proteins, with Vps39 and Vps41 being the unique members. Density-gradient purified mitochondrial PE levels from (D) WT and vps41Δpsd1Δ cultured in SC Lactate ± Etn and (E) WT and vps11Δpsd1Δ cultured in SC Glucose ± Etn. PE levels are expressed as the percent of total phospholipids. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, (n = 3). Each data point represents a biological replicate.

Vps39 is also a member of the HOPS complex, which is a tethering complex that facilitates fusion of vesicles from the Golgi/late endosome to the vacuole [40]. The HOPS complex is a heterohexamer of six different subunits (Fig. 5C). To determine whether Vps39 mediates PE transport through the HOPS complex, we constructed the yeast strain lacking Vps41, a unique and essential component of the HOPS complex. Unlike vps39Δ mutants, Etn supplementation led to a modest but significant increase in mitochondrial PE levels (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, in contrast to Vps39, we found that Vps41 is not localized to the mitochondria in either PE-enriched WT or PE-depleted psd1Δ cells (Fig. S3), suggesting that Vps39 functions independent of the HOPS complex in mitochondrial PE trafficking. In order to further interrogate the role of the HOPS complex in the transport of CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway PE to the mitochondria, we examined Vps11, another essential and a core component of the HOPS complex [40]. We found that Etn-supplementation leads to increased mitochondrial PE in cells lacking Vps11 (Fig. 5E), further precluding a HOPS complex requirement in PE trafficking to the mitochondria. Taken together, these data suggest that Vps39-mediated transport of PE to the mitochondria is independent of intact vCLAMP and HOPS complexes.

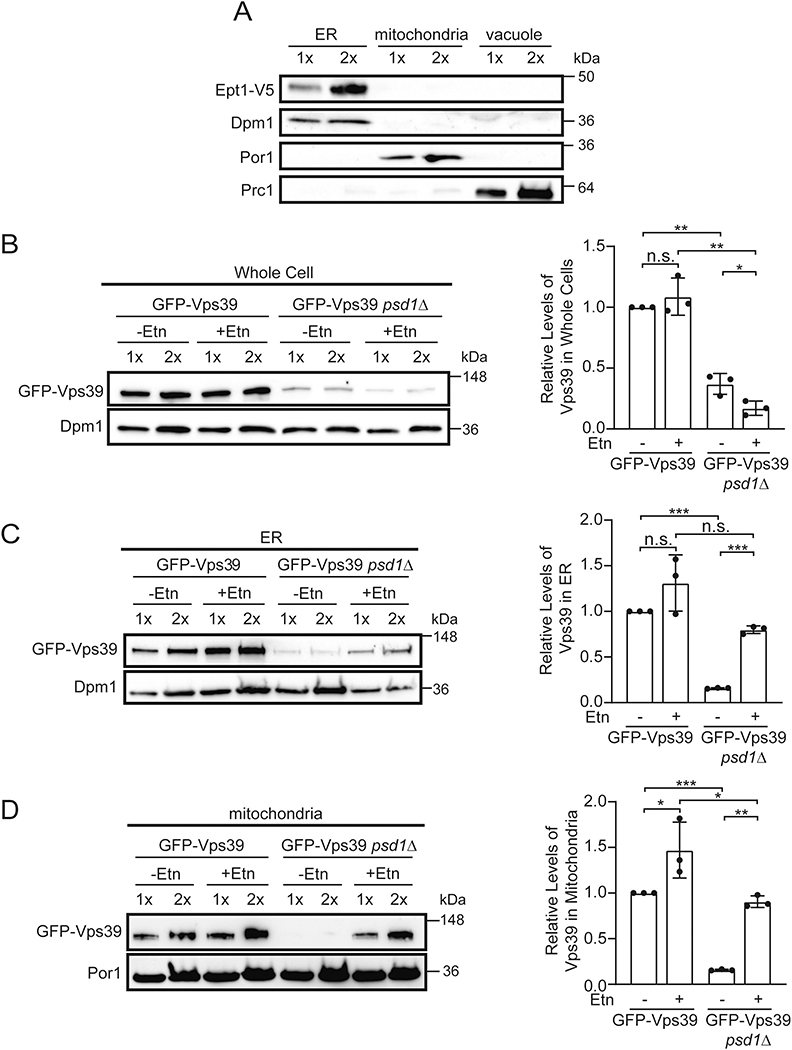

3.6. Vps39 is recruited to the ER and mitochondria in a PE-dependent manner

For Vps39 to directly transport the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway PE from its site of synthesis to the mitochondria, it should localize to both the donor and recipient organelles. Although the localization of Ept1, the terminal enzyme of the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway that catalyzes PE synthesis, has been suggested to be the ER, it has not yet been conclusively determined in yeast [17]. Therefore, we decided to first determine the sub-cellular localization of Ept1. Sub-cellular fractionation followed by western-blot analysis of density-gradient purified ER, mitochondria, and vacuole showed that Ept1 co-localizes with ER marker protein (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that it indeed resides in the ER. Thus, Ept1 localization is consistent with our model that the final step in PE biosynthesis via the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway occurs in the ER.

Fig. 6. Subcellular localization of Ept1 and Vps39.

(A) Western blot detection of V5-tagged Ept1 from density gradient purified ER, mitochondria, and vacuole. Dpm1, Por1, and Prc1 antibodies were used to probe for the purity of the ER, mitochondria, and vacuole, respectively. Ept1-V5 expressing cells were cultured in SC Glucose-Ura medium to mid-logarithmic phase before performing subcellular fractionation. 1× and 2× refer to the amount of protein loaded into each lane. (B-D) Western blot detection (left) and quantification (right) of GFP-tagged Vps39 in WT and psd1Δ cells from whole cell (B), ER (C) and mitochondria (D). GFP-Vps39 expressing cells were cultured in SC Lactate medium to late-logarithmic phase before performing subcellular fractionation as shown in (A). Por1 and Dpm1 are used as loading controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SD; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n.s. not significant, (n = 3). Each image is a representative of three independent experiments and each data point on bar charts represent a biological replicate.

Vps39 has been previously shown to localize to different subcellular sites in accordance with its multiple roles in cellular functions [28]. Based on our newly discovered role of Vps39 in PE trafficking, we hypothesized that Vps39 is recruited to the ER and mitochondria in conditions requiring PE transport. We chose four conditions of varying PE concentrations – WT and psd1Δ cells with and without Etn supplementation – to determine the subcellular localization of Vps39. Similarly to the reduced levels of Vps41 (Fig. S3A), we found that the total cellular levels of Vps39 are significantly reduced in psd1Δ cells (Fig. 6B). These unexpected observations suggest interdependence between Vps39/HOPS abundance and PE metabolism. Consistent with our hypothesis, sub-cellular fractionation showed co-localization of Vps39 with both ER and mitochondrial fractions (Fig. 6C and D), which were purified by density gradient centrifugation as shown for Ept1 in Fig. 6A. Furthermore, quantification of Western blots of the ER fraction showed that Etn supplementation significantly increases Vps39 localization to the ER in psd1Δ cells and there is also a trend towards increased ER localization in the Etn-supplemented WT cells (Fig. 6C). Similar to the ER data, we found that Vps39 localization to the mitochondria also significantly increased upon Etn supplementation (Fig. 6D). The pattern of Vps39 localization to the mitochondria correlated with mitochondrial PE levels, such that Vps39 abundance was highest in Etn supplemented WT mitochondria and lowest in psd1Δ mitochondria (Fig. 6D). Quantitative fluorescent microscopy also showed increased co-localization of Vps39 signal with the mitochondria of Etn supplemented psd1Δ cells (Fig. S4A). We also captured confocal microscopic images of GFP-tagged Vps39 in WT and Etn supplemented psd1Δ cells, which shows redistribution of Vps39 in these two conditions (Fig. S4B). Taken together, our data indicate that Etn supplementation promotes redistribution of Vps39 to the ER and mitochondria, suggesting a direct role of Vps39 in PE transport from the ER to the mitochondria.

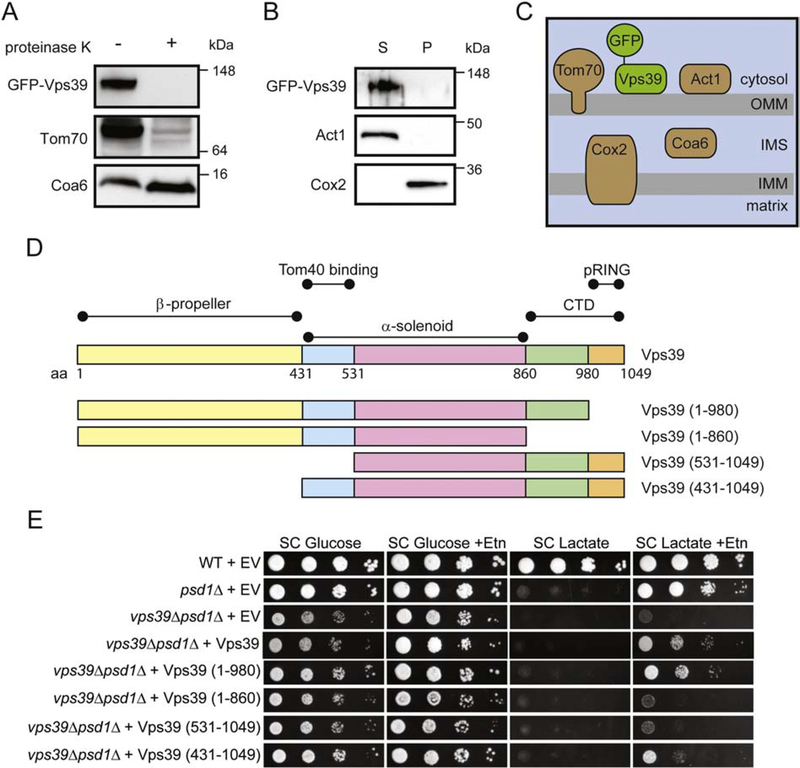

3.7. Vps39 domain analysis for Etn-mediated rescue of psd1Δ respiratory growth

To understand the mechanism by which Vps39 might act in the PE transport pathway to the mitochondria, it is necessary to determine its sub-mitochondrial localization. Recent work by González Montoro et al., has shown that Vps39, as a member of vCLAMP, localizes to the mitochondria via its interaction with Tom40, a well-characterized essential outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) protein required for mitochondrial protein import. This finding led us to hypothesize that Vps39 is peripherally attached to the OMM. Consistent with our hypothesis, proteinase K treatment of the isolated mitochondria led to the degradation of Vps39 and the OMM protein Tom70, but not the mitochondrial intermembrane space protein Coa6 (Fig. 7A). To determine if Vps39 is a peripheral or an integral OMM protein, isolated mitochondria were subjected to high salt extraction, which releases peripheral proteins into the supernatant. Through this treatment, we observed that, similar to Act1, which has been shown to localize peripherally on the OMM [37], but unlike integral membrane protein Cox2, Vps39 was released in the supernatant (Fig. 7B). These observations suggested that Vps39 is peripherally associated to the OMM (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. Vps39 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane and does not require the β-propeller or pRING domain for Etn-mediated rescue of psd1Δ cells.

Western blot detection of GFP-Vps39 in isolated mitochondria before and after proteinase K treatment (A) and in the supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions after high salt extraction (B). To identify sub-mitochondrial localization of GFP-Vps39, the following marker proteins were used: Tom70, OMM; Coa6, IMS; Act1, peripheral OMM; and Cox2, integral IMM. OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMS, intermembrane space; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane. (C) A schematic representation of sub-mitochondrial localization of GFP-Vps39. (D) A schematic representation of predicted structural elements of Vps39 and the truncation mutants used in this study. (E) Ten-fold serial dilution of the WT and indicated yeast mutants were seeded onto SC Glucose ± Etn and SC Lactate ± Etn plates. Images were captured after 2d (SC Glucose media) and 5d (SC Lactate media) of growth at 30 °C. The cells were pre-cultured in YPD media for 10 h prior to seeding. The figure is a representative image of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). EV, empty vector.

Vps39 is a 123 kDa protein with many predicted structural elements including the N-terminal β-propeller, α-solenoid, and pRING domains [41] (Fig. 7D). The β-propeller and the C-terminal domains of Vps39 are required for its HOPS-related function [41,42]; however, the roles of the α-solenoid and pRING domains of Vps39 have not been characterized. To determine which of these domains of Vps39 are essential for PE transport, we generated Vps39 truncation constructs for these domains, which were then transformed into vps39Δpsd1Δ cells and assayed for Etn-dependent growth rescue. The respiratory growth of vps39Δpsd1Δ cells expressing truncation constructs lacking the β-propeller or the pRING domain were partially rescued upon Etn supplementation suggesting that these domains of Vps39 are not essential for PE trafficking from the ER to the mitochondria (Fig. 7E). However, Vps39 lacking the Tom40-binding domain, the α-solenoid, and the C-terminal domain failed to rescue the respiratory growth of vps39Δpsd1Δ cells (Fig. 7E). Together, these data identify critical domains of Vps39 required for Etn-mediated rescue of psd1Δ respiratory growth.

4. Discussion

Mitochondria can biosynthesize some phospholipids; however, a majority of phospholipids are imported from the ER [9]. The phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes and their localizations are conserved in eukaryotes, which necessitates the presence of conserved phospholipid trafficking mechanism(s) that transport phospholipids from the ER to the mitochondria. Recent work has implicated MCS complexes, ERMES and vCLAMP, in phospholipid transport from the ER to the mitochondria [20–26,43]. In this study, we show that Etn-stimulated increase in mitochondrial PE is dependent on Vps39, an evolutionarily conserved subunit of vCLAMP. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Vps39 and Ept1, an enzyme that catalyzes the final step in PE biosynthesis from Etn, localizes to the ER. Vps39 abundance and recruitment to the ER and mitochondria is driven by an increase in the PE levels in these organelles. Remarkably, deletion of other subunits of Vps39-containing complexes, vCLAMP or HOPS, do not impair Etn-mediated increase in mitochondrial PE. These findings solely implicate Vps39 in PE trafficking from its site of synthesis in the ER to the mitochondria.

PE is required for the optimal activities of the mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes and is thus essential for mitochondrial energy generation in both yeast and mammalian cells [10–12]. Not surprisingly, the majority of mitochondrial PE is biosynthesized in situ by Psd1 [18]. However, mitochondrial dysfunction caused by Psd1 deletion can be ameliorated by Etn-mediated stimulation of the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway of PE biosynthesis, implying that PE can be transported from the ER to the mitochondria [10]. Consistent with these findings in yeast cells, PE biosynthesized via the CDP-Etn Kennedy pathway has been shown to rapidly equilibrate with mitochondrial membranes in mammalian cells, suggesting that PE transport from the ER to the mitochondria is evolutionarily conserved [44]. Indeed, a recent study has shown that phenotypes associated with mutations in the human homolog of Psd1 can be rescued with Etn supplementation [45]. Despite the importance of PE transport from the ER to mitochondria, the molecular basis for this process remained unknown. Therefore, our identification of the role of Vps39 in PE transport provides new insights into phospholipid trafficking to the mitochondria. Although here we find that Vps39 is essential for the Etn-mediated elevation in the mitochondrial PE levels, cells lacking Psd1 and Vps39 still contained measurable levels of PE (Fig. 2C and D), which could be attributed to the residual ER contamination in the mitochondrial preparation. Alternatively, this observation implies that there are other mechanisms of non-mitochondrial PE transport to the mitochondria. Indeed, Elbaz-Alon et al. [28] have suggested redundant roles of Vps39-containing vCLAMP and ERMES in phospholipid trafficking [23].

Intracellular phospholipid trafficking between different organelles involves both vesicular and non-vesicular routes [5,8]. Our identification of Vps39, a member of the HOPS vesicular transport pathway, raised an intriguing possibility of Etn-stimulated vesicular transport of PE to the mitochondria, an organelle that has not been previously linked to the vesicular pathway [46]. Deletion of other essential members of the HOPS complex failed to abrogate Etn-stimulated elevation in mitochondrial PE levels (Fig. 5D and E), arguing against HOPS-mediated vesicular transport of PE to the mitochondria. Consistent with these results, we found that the β-propeller region of Vps39, which is required for HOPS function [42], is not essential for PE transport to the mitochondria (Fig. 7E), further precluding HOPS-mediated vesicular transport as a probable mechanism.

In addition to being a critical component of the HOPS complex, Vps39 has been shown to be a member of a MCS complex, vCLAMP, which connects vacuoles to the mitochondria [28,29]. We examined the possibility that PE formed in the ER is transported via the vacuole through vCLAMP in a non-vesicular route to the mitochondria by deleting the essential members of vCLAMPs, Vps13, which has been shown to bind phospholipids [21] and Ypt7 [39]. The deletion of Vps13 or Ypt7 failed to inhibit Etn-stimulated elevation of mitochondrial PE (Fig. 5B), suggesting that intact vCLAMP complexes are not required for Etn-stimulated PE transport to the mitochondria.

Since Vps39-mediated PE transport to the mitochondria is independent of its previously defined functions within the cell, the question arises as to how is Vps39 involved in PE transport? Vps39 may act indirectly in this process by regulating localization or function of transport proteins or could play a more direct role in the transport process itself. A significant fraction of intracellular lipid transport is mediated by a large group of soluble ‘lipid cargo proteins’ called Lipid Transport Proteins (LTPs) that traffic lipid molecules between intracellular organelles in their hydrophobic cavities [7]. Vps39 exhibits many of the criteria of an LTP - first, Vps39 localizes to both the donor (ER) and the recipient membranes (mitochondria) (Fig. 6C and D). Second, it is specifically required for PE transport (Fig. 2). Third, it contains an α-solenoid domain, which has been shown to bind phospholipids in other proteins. Further in vitro experiments demonstrating PE-binding and PE transfer activities are needed to determine if Vps39 is indeed a bona fide LTP. It is notable that recent studies have uncovered new sub-cellular localizations and unanticipated roles of other vCLAMP subunits, including Vps13 and Mcp1, in intracellular lipid transport and homeostasis [21,43,47–50].

Our study also raises many important questions in ER-mitochondrial PE exchange. For example, is Vps39 essential for PE trafficking from the ER to the mitochondria under basal conditions or only upon Etn supplementation? Does Vps39 also play a role in the export of mitochondrially synthesized PE? Are there dedicated adaptor proteins required for Vps39 localization to the ER for the PE transport processes? Critical analyses of our data provide answers to some of these questions. For example, we observed an increased steady state level of PE in the vps39Δ mitochondria (Fig. 2C and D) and a decrease in PE levels in the ER of vps39Δ mutants (Fig. 3A). This finding is consistent with a PE export defect because under basal conditions mitochondria are the major source of cellular PE; therefore, inhibiting PE export from the mitochondria is expected to result in elevation of mitochondrial PE levels and a decrease in the ER PE levels. Although the factors required for Vps39 localization to the ER are not yet identified, our Vps39 protein truncation data suggest that Tom40 binding could be crucial for PE trafficking to the mitochondria (Fig. 7D and E). This idea is consistent with the recent report showing that Vps39 localizes to the mitochondria via its interaction with Tom40, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein [39]. In summary, our study uncovered a critical role of Vps39 in ER-mitochondria PE transport contributing to our understanding of inter-organellar phospholipid trafficking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank John Neff, Sagnika Ghosh, Alison Vicary, and Dr. William Prinz for their valuable comments in the preparation of this manuscript. We thank Drs. Paul Lindahl, Jan Brix, and Christian Ungermann for generously providing us with antibodies and yeast strains.

Funding

This work was supported by The Welch Foundation Grant (A-1810) and the National Institutes of Health awards R01GM111672 to V.M.G. and R01GM129000 to B.N. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- Etn

ethanolamine

- vCLAMP

vacuole and mitochondrial patch

- ERMES

ER and mitochondria encounter structure

- HOPS

homotypic fusion and protein sorting

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158655.

References

- [1].Zinser E, Sperka-Gottlieb CD, Fasch EV, Kohlwein SD, Paltauf F, Daum G, Phospholipid synthesis and lipid composition of subcellular membranes in the unicellular eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J. Bacteriol 173 (1991) 2026–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schmidt O, Pfanner N, Meisinger C, Mitochondrial protein import: from proteomics to functional mechanism, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 11 (2010) 655–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tamura Y, Sesaki H, Endo T, Phospholipid transport via mitochondria, Traffic. 15 (2014) 933–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tatsuta T, Scharwey M, Langer T, Mitochondrial lipid trafficking, Trends Cell Biol. 24 (2014) 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Voelker DR, Genetic and biochemical analysis of non-vesicular lipid traffic, Annu. Rev. Biochem 78 (2009) 827–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prinz WA, Bridging the gap: membrane contact sites in signaling, metabolism, and organelle dynamics, J. Cell Biol 205 (2014) 759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wong LH, Gatta AT, Levine TP, Lipid transfer proteins: the lipid commute via shuttles, bridges and tubes, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20 (2018) 85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vance JE, Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells, Traffic. 16 (2015) 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Flis VV, Daum G, Lipid transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5 (2013) pii:a013235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Baker CD, Basu Ball W, Pryce EN, Gohil VM, Specific requirements of nonbilayer phospholipids in mitochondrial respiratory chain function and formation, Mol. Biol. Cell 27 (2016) 2161–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Böttinger L, Horvath SE, Kleinschroth T, Hunte C, Daum G, Pfanner N, Becker T, Phosphatidylethanolamine and cardiolipin differentially affect the stability of mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes, J. Mol. Biol 423 (2012) 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tasseva G, Bai HD, Davidescu M, Haromy A, Michelakis E, Vance JE, Phosphatidylethanolamine deficiency in mammalian mitochondria impairs oxidative phosphorylation and alters mitochondrial morphology, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 4158–4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Trotter PJ, Pedretti J, Voelker DR, Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Isolation of mutants, cloning of the gene, and creation of a null allele, J. Biol. Chem 268 (1993) 21416–21424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Clancey CJ, Chang SC, Dowhan W, Cloning of a gene (PSD1) encoding phosphatidylserine decarboxylase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by complementation of an Escherichia coli mutant, J. Biol. Chem 268 (1993) 24580–24590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trotter PJ, Voelker DR, Identification of a non-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine decarboxylase activity (PSD2) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J. Biol. Chem 270 (1995) 6062–6070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gulshan K, Shahi P, Moye-Rowley WS, Compartment-specific synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine is required for normal heavy metal resistance, Mol. Biol. Cell 21 (2010) 443–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Henry SA, Kohlwein SD, Carman GM, Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics. 190 (2012) 317–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bürgermeister M, Birner-Grünberger R, Nebauer R, Daum G, Contribution of different pathways to the supply of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine to mitochondrial membranes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1686 (2004) 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Birner R, Bürgermeister M, Schneiter R, Daum G, Roles of phosphatidylethanolamine and of its several biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mol. Biol. Cell 12 (2001) 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kawano S, Tamura Y, Kojima R, Bala S, Asai W, Michel AH, Kornmann B, Riezman I, Riezman H, Sakae Y, Okamoto Y, Endo T, Structure-function insights into direct lipid transfer between membranes by Mmm1-Mdm12 of ERMES, J. Cell Biol 217 (2018) 959–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kumar N, Leonzino M, Hancock-Cerutti W, Horenkamp FA, Li P, Lees JA, Wheeler H, Reinisch KM, De Camilli P, VPS13A and VPS13C are lipid transport proteins differentially localized at ER contact sites, J. Cell Biol 217 (2018) 3625–3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].AhYoung AP, Jiang J, Zhang J, Khoi Dang X, Loo JA, Zhou ZH, Egea PF, Conserved SMP domains of the ERMES complex bind phospholipids and mediate tether assembly, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 25 (2015) E3179–E3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jeong H, Park J, Lee C, Crystal structure of Mdm12 reveals the architecture and dynamic organization of the ERMES complex, EMBO Rep. 12 (2016) 1857–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jeong H, Park J, Jun Y, Lee C, Crystal structures of Mmm1 and Mdm12-Mmm1 reveal mechanistic insight into phospholipid trafficking at ER-mitochondria contact sites, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 45 (2017) E9502–E9511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gatta AT, Levine TP, Piecing together the patchwork or contact sites, Trends Cell Biol. 27 (2017) 214–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lahiri S, Toulmay A, Prinz WA, Membrane contact sites, gateways for lipid homeostasis, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 33 (2015) 82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P, An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen, Science. 325 (2009) 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Elbaz-Alon Y, Rosenfeld-Gur E, Shinder V, Futerman AH, Geiger T, Schuldiner M, A dynamic interface between vacuoles and mitochondria in yeast, Dev. Cell 30 (2014) 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hönscher C, Mari M, Auffarth K, Bohnert M, Griffith J, Geerts W, van der Laan M, Cabrera M, Reggiori F, Ungermann C, Cellular metabolism regulates contact sites between vacuoles and mitochondria, Dev. Cell 30 (2014) 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Amberg DC, Burke DJ, Strathern JN, Methods in Yeast Genetics. A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, Knop M, A versatile toolbox for PCRbased tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes, Yeast. 21 (2004) 947–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Meisinger C, Pfanner N, Truscott KN, Isolation of yeast mitochondria, Methods Mol. Biol 313 (2006) 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wuestehube LJ, Schekman RW, Reconstitution of transport from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi complex using endoplasmic reticulum-enriched membrane fraction from yeast, Methods Enzymol 219 (1992) 124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Haas A, Scheglmann D, Lazar T, Gallwitz D, Wickner W, The GTPase Ypt7p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required on both partner vacuoles for the homotypic fusion step of vacuole inheritance, EMBO J 14 (1995) 5258–5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH, A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues, J. Biol. Chem 1 (1957) 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gabriel K, Milenkovic D, Chacinska A, Müller J, Guiard B, Pfanner N, Meisinger C, Novel mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins as substrates of the MIA import pathway, J. Mol. Biol 365 (2007) 612–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Boldogh I, Vojtov N, Karmon S, Pon LA, Interaction between mitochondria and the actin cytoskeleton in budding yeast requires two integral mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, Mmm1p and Mdm10p, J. Cell Biol 141 (1998) 1371–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH, A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy, Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 300 (2011) C723–C742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].González Montoro A, Auffarth K, Hönscher C, Bohnert M, Becker T, Warscheid B, Reggiori F, van der Laan M, Fröhlich F, Ungermann C, Vps39 interacts with Tom40 to establish one of two functionally distinct vacuole-mitochondria contact sites, Dev, Cell 45 (2018) 621–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Balderhaar HJ, Ungermann C, CORVET and HOPS tethering complexes – coordinators of endosome and lysosome fusion, J. Cell Sci 126 (2013) 1307–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Plemel RL, Lobingier BT, Brett CL, Angers CG, Nickerson DP, Paulsel A, Sprague D, Merz AJ, Subunit organization and Rab ineractions of Vps-C protein complexes that control endolysosomal membrane traffic, Mol. Biol. Cell 22 (2011) 1353–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lürick A, Gao J, Kuhlee A, Yavavli E, Langemeyer L, Perz A, Raunser S, Ungermann C, Multivalent Rab interactions determine tether-mediated membrane fusion, Mol. Biol. Cell 28 (2017) 322–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lang A, John Peter AT, Kornmann B, ER-mitochondria contact sites in yeast: beyond the myths of ERMES, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 35 (2015) 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bleijerveld OB, Brouwers JF, Vaandrager AB, Helms JB, Houweling M, The CDP-ethanolamine pathway and phosphatidylserine decarboxylation generate different phosphatidylethanolamine molecular species, J. Biol. Chem 282 (2007) 28362–28372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Girisha KM, von Elsner L, Neethukrishna K, Muranjan M, Shukla A, Bhavani GS, Nishimura G, Kutsche K, Mortier G, The homozygous variant c.797G > A/p.(Cys266Tyr) in PISD is associated with a Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia with large epiphyses and disturbed mitochondrial function, Hum. Mutat 40 (2019) 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Prinz WA, Lipid trafficking sans vesicles: where, why, how? Cell. 143 (2010) 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Park JS, Thorsness MK, Policastro R, McGoldrick LL, Hollingsworth NM, Thorsness PE, Neiman AM, Yeast Vps13 promotes mitochondrial function and is localized at membrane contact sites, Mol. Biol. Cell 15 (2016) 2435–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bean BDM, Dziurdzik SK, Kolehmainen KL, Fowler CMS, Kwong WK, Grad LI, Davey M, Schluter C, Conibear E, Competitive organelle-specific adaptors recruit Vps13 to membrane contact sites, J. Cell Biol 10 (2018) 3593–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tan T, Ozbalci C, Brügger B, Rapaport D, Dimmer KS, Mcp1 and Mcp2, two novel proteins involved in mitochondrial lipid homeostasis, J. Cell Sci 126 (2013) 3563–3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].John Peter AT, Herrmann B, Antunes D, Rapaport D, Dimmer KS, Kornmann B, Vps13-Mcp1 interact at vacuole-mitochondria interfaces and bypass ER-mitochondria contact sites, J. Cell Biol 10 (2017) 3219–3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.