Abstract

Background:

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) persist despite the widespread implementation of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART). As people with HIV (PWH) age on ART regimens, the risk of age-related comorbidities such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may increase. However, questions remain as to whether HIV or ART will alter such risks. Beta amyloid (Aβ) and phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) proteins are associated with AD and their levels are altered in the CSF of AD cases.

Methods:

To better understand how these AD-related markers are affected by HIV-infection and ART, postmortem CSF collected from 70 well-characterized HIV+ decedents was analyzed for Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40, and p-tau levels.

Results:

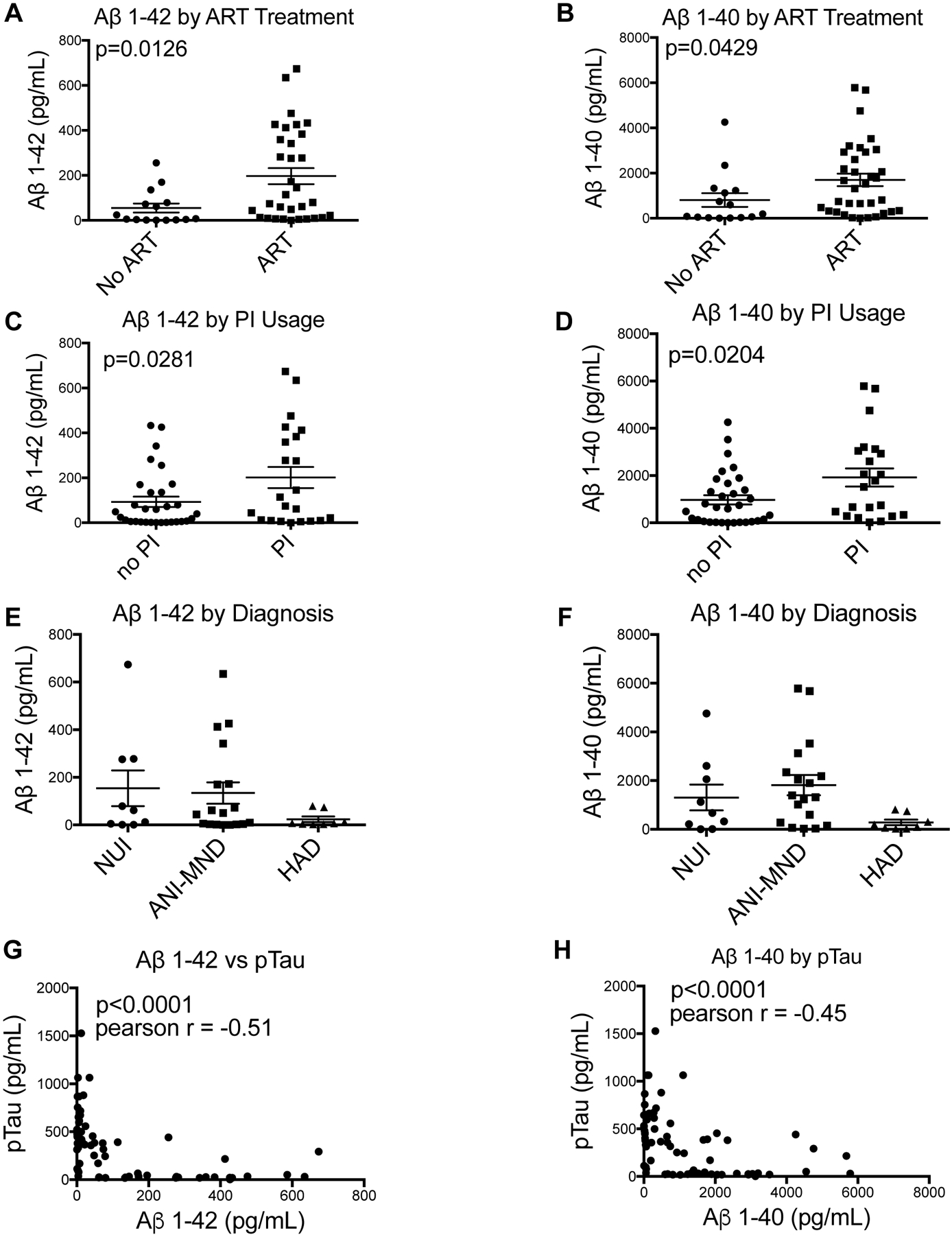

Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 CSF levels were higher in cases that were exposed to ART. Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 CSF levels were also higher in cases on protease inhibitors (PI) compared to those with no exposure to PIs. Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels in CSF were lowest in HIV+ cases with HIV-associated dementia (HAD) and levels were highest in those diagnosed with asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI) and minor neurocognitive disorder (MND). Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were inversely related with p-tau levels in all cases, as previously reported.

Conclusions:

These data suggest that ART exposure is associated with increased levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the CSF. Also, HAD, but not ANI/MND diagnosis is associated with decreased levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in CSF, potentially suggesting impaired clearance. These data suggest that HIV infection and ART may impact pathogenic mechanisms involving Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, but not p-tau.

Introduction

HAND affects approximately 50% of people with HIV (PWH) despite the ability to control HIV replication with antiretroviral therapy (ART)[1, 2]. Approximately 40% of PWH in the United States (U.S.) are over the age of 55[3], and some reports suggest that PWH experience premature aging[4–6]. In addition to the risk of developing HAND, older PWH may also be at risk for age-associated neurodegenerative disorders including AD and its precursor, amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI)[7]. In fact, evidence of AD-related neuropathogenesis has been observed in some older PWH[8–11], and one study showed higher risk for aMCI among PWH compared to the general population[12] possibly due to potential compounding effects of HIV and aging on mechanisms of neural insult such as inflammation[6, 13].

Amyloid beta (Aβ) and p-tau accumulation are hallmarks of AD that are used to confirm AD diagnosis in postmortem brains. Several studies have found Aβ and p-tau accumulation in HIV+ brains[14, 15]. Several groups have investigated Aβ and p-tau levels in the CSF of HIV+ cases with different levels of cognitive impairment[10, 16–19]. However, the levels Aβ and p-tau in brains and CSF of PWH on ART compared to those naïve to ART have not been explored. While few of the HIV cases have lived to the age of late onset AD, it may be important to determine the levels of Aβ and p-tau in the CSF of people on ART because these people are expected to live normal lifespans.

In our study, the CSF from a cohort of well-characterized PWH was analyzed for Aβ and p-tau levels. The data were stratified by cognitive status, CD4 count, viral load (vl), age and exposure to ART. The findings illustrate a yet unreported relationship between ART and Aβ levels; they reveal that lowest levels of CSF Aβ were found in cases with the most severe forms of HAND (i.e. HAD), and demonstrate a strong inverse relationship between CSF Aβ and p-tau.

Methods:

Study population

For the present study, we evaluated brain tissues from a total of 71 HIV+ donors (Table 1), from the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium (NNTC) (Institutional Review Board [IRB] #080323). All studies adhered to the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Diego. These cases had neuromedical and neuropsychological examinations within a median of 12 months before death. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of CNS opportunistic infections or non-HIV-related developmental, neurologic, psychiatric, or metabolic conditions that might affect CNS functioning (e.g., loss of consciousness exceeding 30 minutes, psychosis, etc). HAND diagnoses (neurocognitively unimpaired [NIU], asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment [ANI], minor neurocognitive dysfunction [MND], and HIV-associated dementia [HAD]) were determined from a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery administered according to standardized protocols [20].

Table:

Demographic data for human CSF samples. Quantities shown are mean +/−standard deviation. Bottom rows depict the p-values and effect sizes between the illustrated groups.

| Variables | NUI (n=110) | HAND (n=26) | NUI vs HAND | NUI vs ANI vs MND vs HAD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANI (n=6) | MND (n=12) | HAD (n=8) | ANI-O (n=15) | ND (n=20) | p-value (Cog. Normal vs HAND; t-test) | Effect Size - Cohen’s d (Cog. Norm vs HAND) | p-value (NUI vs ANI, NUI vs MND, NUI vs HAD, ANI vs MND, ANI vs HAD, MND vs HAD; ANOVA) | Effect Size: overall (NUI vs ANI, NUI vs MND, NUI vs HAD, ANI vs MND, ANI vs HAD, MND vs HAD) | |||

| Years of Age | 42.8 ± 7.21 | 46.83 ± 13.35 | 42.50 ± 4.56 | 43.88 ± 9.45 | 44.27 ± 11.97 | 45.0 ± 9.51 | 0.72 | 0.14 | 0.44, 0.91, 0.79, 0.32, 0.63, 0.67, 0.75 | 0.38, 0.05, 0.13, 0.43, 0.26, 0.19 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 10.00 | 16.67 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 53.33 | 12.50 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Sex (f/m) | 1/9 | 1/5 | 1/11 | 1/7 | 3/12 | 4/16 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Years of Education | 12.0 ± 1.76 | 15.0 ± 2.76 | 13.0 ± 3.07 | 12.83 ± 2.56 | 11.27 ± 3.73 | 12.0 ± 1.73 | 0.15 | 0.61 | 0.02, 0.37, 0.45, 0.20, 0.19, 0.91, 0.19 | 1.30, 0.40, 0.38, 0.69, 0.82, 0.06 | |

| HIV Disease Characteristics | |||||||||||

| Plasma VL | 160,625.22 ± 292965.6 | 169540.40 ± 332082.60 | 315359.55 ± 522262.50 | 364349.09 ± 631006.34 | 104554 ± 200222.65 | 320949 ± 275890.09 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.96, 0.44, 0.41, 0.58, 0.55, 0.87, 0.79 | 0.03, 0.37, 0.41, 0.33, 0.38, 0.08 | |

| CD4 count | 141.9 ± 143.47 | 69.83 ± 93.43 | 109.08 ± 249.26 | 53.86 ± 99.75 | 161.53 ± 246.83 | 78.33 ± 72.54 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.29, 0.72, 0.18, 0.72, 0.77, 0.59, 0.74 | 0.60, 0.16, 0.71, 0.21, 0.17, 0.29 | |

| CSF VL (CVL) | 36656.25 ± 74983.47 | 579.00 ± 1252.08 | 12320.25 ± 33307.13 | 376572.33 ± 578056.84 | 5273.14 ± 8356.89 | 119396.75 ± 227553.46 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.31, 0.33, 0.12, 0.45, 0.18, 0.039, 0.036 | 0.68, 0.42, 0.82, 0.50, 0.92, 0.89 | |

| pmi | 24.56 ± 36.67 | 20 ± 16.78 | 20.75 ± 26.24 | 14.13 ± 8.76 | 19.07 ± 21.52 | 13.47 ± 6.47 | 0.54 | 0.2 | 0.78, 0.78, 0.47, 0.95, 0.41, 0.50, 0.87 | 0.16, 0.12, 0.39, 0.03, 0.44, 0.34 | |

HIV disease characteristics for human CSF samples. Quantities shown are mean +/−standard deviation. Bottom rows depict the p-values and effect sizes between the illustrated groups.

Neuromedical and neuropsychological evaluation

Participants underwent a comprehensive neuromedical evaluation that included assessment of medical history, structured medical and neurological examinations, and the collection of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and urine samples, as previously described [1, 20]. Clinical data (plasma viral load [VL], postmortem interval, CD4 count, global, learning and motor deficit scores [GDS, LDS, and MDS]) were collected for the HAND donor cohorts.

Neuropsychological evaluation was performed, and HAND diagnoses were determined via a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery, which was constructed to maximize sensitivity to neurocognitive deficits associated with HIV infection [see [20] for a list of tests]. Raw tests scores were transformed into demographically adjusted T-scores, including adjustments for age, education, gender and race. These demographically adjusted T-scores were converted to clinical ratings to determine presence and degree of neurocognitive impairment on seven neurocognitive domains, as previously described (Woods et al., 2004). As part of the neuropsychological battery, participants also completed self-report questionnaires of everyday functioning (i.e., Lawton and Brody Activities of Daily Living questionnaire;[21], and/or Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning; PAOFI [22, 23]. Participant’s performance on the neuropsychological test battery and their responses to the everyday functioning questionnaires were utilized to assign HAND diagnoses following established criteria [24], i.e., HIV-associated asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder (MND), and HIV-associated dementia (HAD).

Quantification of Aβ1–42 and p-tau levels in the CSF:

CSF samples were analyzed for p-tau using a solid phase enzyme immunoassay, Innotest Phospho-Tau (181P) (Fujirebio, cat. no. 81581) and phospho-tau CAL-RVC (Fujirebio, cat. no 81582) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Beta amyloid peptides (1–38), (1–40) and (1–42) were measured in the CSF using V-Plex plus Aβ Peptide 1 (4G8) kit (Meso Scale Diagnostics, cat. no. K15199G) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA for comparisons between more than two groups and using a T-test when there were only two groups. All results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The differences were significant if p values were <0.05 and the actual p value was reported if near, but over the 0.05 cutoff. All sample sizes are included in figure legends.

Data Availability:

All data will be made available on-line through the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium.

Results:

Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 concentrations are higher in the CSF of HIV+ individuals on ART compared to ART naïve, higher in those taking PIs compared to no PIs, lower in those with worse neurocognitive impairment and negatively correlated with pTau concentration.

Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 and pTau concentrations in the CSF were determined by electochemiluminescent assay using Mesoscale discovery (MSD). Levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in PWH being treated with ART or not on ART were plotted. In CSF from people on ART, levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 (Figure 1A and B) were increased compared to those taking no ART, p = 0.0126 and 0.0429, respectively. To determine if levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 differ with by PI usage, quantities were stratified by cases with history of PI and no PI in the ART regimens or ART naïve. In those last known taking PIs, levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were significantly increased compared to cases not exposed to PIs, with p values of 0.0281 and 0.0204, respectively (Figure 1C and D). CSF Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels were also stratified by severity of neurocognitive impairment: NUI, ANI/MND, and HAD. In CSF, there is a trend for decrease in CSF levels of Aβ1–42 and a decrease in Aβ1–40 in HAD cases compared to ANI-MND or NUI (Figure 1E and F). To determine the association of p-tau and Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the CSF, we plotted Aβ1–42 vs p-tau (Figure 1G) and Aβ1–40 v. p-tau (Figure 1H). CSF Aβ1–42 v. CSF p-tau showed a negative correlation with a pearson r value of −.51 and a significance value of p<0.0001 (Figure 1G). CSF Aβ1–40 vs p-tau showed a negative correlation with a Pearson r value of −.45 and a significance value of p<0.0001 (Figure 1H). These data support previous findings which have shown a negative correlation between CSF p-tau and Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40. To determine if the variance in Aβ1–42 levels between the groups was related to clinical variables (plasma viral load (VL), CSF VL, and CD4 count) the entire cohort and also the MND group alone were sub-divided into two and three groups based on Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels and analyzed by t-test or one-way ANOVA, respectively. The ratio of Aβ1–41:Aβ1–40 and p-tau values was compared between the groups (by HAND, ART, and PI). Finally, the differences in p-tau levels between the groups were analyzed similarly. However, no significant differences were detected between the groups.

Figure 1:

CSF Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were quantified and plotted based on antiretroviral therapy regimen, HAND diagnosis and by ptau concentration. Last known ART regimen was determined, and CSF concentrations were plotted based on if donors were last known taking ART or last known taking no ART and if they were last known taking PIs or not taking PIs. Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 concentrations were plotted based on ART therapy (A and B). Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were plotted based on PI usage or no PI usage (C and D). Significance values were determined using student’s t-test (no ART, n = 15; ART, n = 33; no PI, n = 32; PI, n = 22). CSF Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were quantified and plotted based on neurocognitive diagnoses. Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were plotted based on diagnoses of NUI, ANI-MND, or HAD (E and F). Significance values were determined using a one-way ANOVA (NUI, n = 9; ANI-MND, n = 18; HAD, n = 8). CSF Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were plotted versus pTau. (G) Aβ1–42 plotted versus pTau. (H) Aβ1–40 plotted versus p-tau. Significance and Pearson r values were determined using correlation statistics (n= 68).

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time that Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels in CSF are significantly elevated in PWH that were exposed to ART compared to ART naïve cases. Similarly, Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels are significantly elevated in CSF of PWH that were exposed to PIs compared to those that were ART naïve or on ART regimens with no PIs. These analyses also revealed a trend for increased Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in CSF from NUI, ANI and MND cases compared to those with HAD. As previously reported, a strong inverse relationship between Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 and p-tau levels in CSF was confirmed in this cohort. Interestingly, no significant differences were found in levels of p-tau when analyzed by HAND status or other clinical variables, suggesting that HIV and/or ART may more directly affect Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels and not p-tau.

The findings that Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels in the CSF are significantly higher in cases exposed to ART compared to ART-naïve cases suggest that ART may affect the clearance of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 from the brain parenchyma. This remarkable finding may be consistent with and explain data showing that ART regimens can reduce severity of cognitive impairment [25, 26]. However, Giunta et al found that some ART drugs reduce microglial phagocytosis of Aβ and increase production of Aβ by neurons in murine cellular models [27]. It is possible that increased Aβ levels in CSF observed in cases exposed to ART are a reflection of overall production of Aβ. It is also possible that ART-mediated effects on mice is distinct from ART effects in humans. The findings presented here are inconsistent with a recent report that suggest that nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors can block somatic recombination of the APP gene and subsequent generation of Aβ1–42 [28]. Furthermore, the fact that cases with exposure to PIs also have increased Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the CSF may be consistent with a study suggesting that PIs result in less degradation of Aβ [29]. Levels of Aβ were stratified by CD4 count, viral load, and APOE4 alleles, but no significant differences were observed.

Aβ levels in CSF have been used as a biomarker for AD severity, with increased Aβ plaques being associated with reduced Aβ in CSF [30]. Although conflicting reports exist regarding Aβ levels in CSF of HIV+ people, Brew et al. found that CSF Aβ1–42 levels were lower in cases with AIDS dementia complex (ADC) and therefore concluded that ADC pathogenesis may be similar to Alzheimer’s disease [16]. Similarly, Clifford et al found that Aβ1–42 levels in CSF were lower in HAND cases compared to HIV- controls and HIV+ cases that were NUI[10]. However, the HAND cases were analyzed in aggregate and not stratified by severity as reported here [10]. Gisslen et al reported that Aβ1–42 levels in CSF from cases with AIDS dementia complex did not differ from HIV+ NUI cases, which is contrary to the findings in this report [18]. A more recent study of CSF from 25 HIV+ people with HAND showed the highest levels of Aβ1–42 and p-tau were found in HAD cases and lowest were found in CSF of ANI cases, which is contrary to our findings when stratified by cognitive status [19]. While the differences were not significant, our findings show a trend that is consistent with the earlier studies that showed decreased Aβ1–42 in CSF occurring in people with worse neurocognitive impairment. Given that ART is readily available to PWH, the current findings showing robust differences based on ART exposure may be most relevant moving forward.

HAND is a multifactorial disease that is likely driven partly by age, drugs of abuse, duration of infection, ART initiation, duration of ART adherence, or comorbidities. The current findings provide insight into Aβ biology in the PWH. However, the findings are limited by lack of knowledge of concomitant comorbidities. The variance in Aβ1–42 levels between and within HAND groups in this cohort, particularly within the ANI/MND group, illustrate that Aβ1–42 levels alone are not associated neurocognitive impairment in all cases. Recent studies have shown that alterations in the ratio of Aβ1–42:Aβ1–40 may be related to the neurodegenerative process[31]. However, we found no association between Aβ1–42:Aβ1–40 ratio and HAND status or other clinical variables. Future studies that can compare multiple clinical variables with Aβ levels may reveal parameters key to predicting neurocognitive impairment in PWH. Further characterization of alternative biomarkers in CSF or blood may, in conjunction with Aβ levels, provide useful insight into possible mechanisms of neuropathogenesis in individual cases. Biomarkers such as triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, C-reactive protein, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or YLK-40, which are directly or indirectly linked to Aβ levels, have been associated with HAND[32–38] and may be useful markers to pair with Aβ levels. A better understanding how genetics or environmental factors may interact with HIV infection to affect Aβ1–42 levels, other biomarkers, and influence neurocognitive impairment may lead to improved prognostic and diagnostic care for PWH.

Overall, these data suggest a relationship between Aβ levels in CSF and exposure to ART in PWH. Furthermore, the relationship between Aβ levels in CSF and cognitive status deserves further study in additional cohorts. Collection of CSF from more PWH that are over the age of 55 will be helpful to better understand if Aβ levels are affected with age. Similarly, it will be important to determine if p-tau is affected in PWH and older ages and how it relates to cognitive status.

Funding:

This study was funded by NIH awards MH105319 (CLA) and MH115819 (JAF).

Appendix 1:

| Name | Location | Role | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jerel Adam Fields, PhD | University of California, San Diego | Corresponding author | Design and conceptualization of study; drafted manuscript |

| Mary K. Swinton, BS | University of California, San Diego | Author | Data acquisition and manuscript revision |

| Benchawanna Soontornniyomkij, PhD | University of California, San Diego | Author | Data acquisition and organization |

| Aliyah Carson, BS | University of California, San Diego | Author | Data acquisition and manuscript revision |

| Cristian L. Achim | University of California, San Diego | Senior author | Data interpretation; revision of the manuscript |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval for human studies: All experiments described were approved by the human subjects committee and Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), and were performed according to NIH recommendations for use of human biospecimens.

References:

- 1.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 2010; 75(23):2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol 2011; 17(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith G Statement of Senator Gordon H Smith. Aging hearing: HIV over fifty, exploring the new threat In: Senate Committee on Aging. Washington, DC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott JC, Woods SP, Carey CL, Weber E, Bondi MW, Grant I. Neurocognitive Consequences of HIV Infection in Older Adults: An Evaluation of the “Cortical” Hypothesis. AIDS Behav 2011; 15(6):1187–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarda LA, Luna MA, Smith JL, Mansell PWA, Gyorkey F, Roca AN. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: Postmortem findings. AmJClinPathol 1984; 81:549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine AJ, Quach A, Moore DJ, Achim CL, Soontornniyomkij V, Masliah E, et al. Accelerated epigenetic aging in brain is associated with pre-mortem HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurovirol 2016; 22(3):366–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan IL, Smith BR, Hammond E, Vornbrock-Roosa H, Creighton J, Selnes O, et al. Older individuals with HIV infection have greater memory deficits than younger individuals. J Neurovirol 2013; 19(6):531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achim CL, Adame A, Dumaop W, Everall IP, Masliah E. Increased accumulation of intraneuronal amyloid beta in HIV-infected patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2009; 4(2):190–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alisky JM. The coming problem of HIV-associated Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses 2007; 69(5):1140–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clifford DB, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Teshome M, Shah AR, et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer disease in HIV-associated neurologic disease. Neurology 2009; 73(23):1982–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esiri MM, Biddolph SC, Morris CS. Prevalence of Alzheimer plaques in AIDS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65(1):29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheppard DP, Iudicello JE, Morgan EE, Kamat R, Clark LR, Avci G, et al. Accelerated and accentuated neurocognitive aging in HIV infection. J Neurovirol 2017; 23(3):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia R, Ryscavage P, Taiwo B. Accelerated aging and human immunodeficiency virus infection: emerging challenges of growing older in the era of successful antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol 2012; 18(4):247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Accelerated Tau deposition in the brains of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1 before and after the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy. Acta Neuropathol 2006; 111(6):529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fields JA, Dumaop W, Crews L, Adame A, Spencer B, Metcalf J, et al. Mechanisms of HIV-1 Tat neurotoxicity via CDK5 translocation and hyper-activation: role in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Curr HIV Res 2015; 13(1):43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brew BJ, Pemberton L, Blennow K, Wallin A, Hagberg L. CSF amyloid beta42 and tau levels correlate with AIDS dementia complex. Neurology 2005; 65(9):1490–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson L, Blennow K, Fuchs D, Svennerholm B, Gisslen M. Increased cerebrospinal fluid protein tau concentration in neuro-AIDS. J Neurol Sci 1999; 171(2):92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gisslen M, Krut J, Andreasson U, Blennow K, Cinque P, Brew BJ, et al. Amyloid and tau cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in HIV infection. BMC Neurol 2009; 9:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JHY, Fok A, Gil M, Yamamoto A, Guillemi S, Harris M, et al. Alzheimer CSF Biomarkers in Patients with HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (P03.083). Neurology 2013; 80(7 Supplement):P03.083–P003.083. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Frol AB, Levy JK, Ryan E, Soukup VM, et al. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2004; 26(6):759–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chelune GJ, Baer RA. Developmental norms for the Wisconsin Card Sorting test. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1986; 8(3):219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chelune GJ, Heaton RK, & Lehman RA. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients’ complaints of disability. . 1986.

- 24.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 2007; 69(18):1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutsch R, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Marcotte TD, Letendre S, Grant I. AIDS-associated mild neurocognitive impairment is delayed in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Aids 2001; 15(14):1898–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larussa D, Lorenzini P, Cingolani A, Bossolasco S, Grisetti S, Bongiovanni M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy reduces the age-associated risk of dementia in a cohort of older HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2006; 22(5):386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giunta B, Ehrhart J, Obregon DF, Lam L, Le L, Jin J, et al. Antiretroviral medications disrupt microglial phagocytosis of beta-amyloid and increase its production by neurons: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Mol Brain 2011; 4(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MH, Siddoway B, Kaeser GE, Segota I, Rivera R, Romanow WJ, et al. Somatic APP gene recombination in Alzheimer’s disease and normal neurons. Nature 2018; 563(7733):639–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan X, Kiyota T, Hanamsagar R, Huang Y, Andrews S, Peng H, et al. The effect of HIV protease inhibitors on amyloid-beta peptide degradation and synthesis in human cells and Alzheimer’s disease animal model. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2012; 7(2):412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tapiola T, Alafuzoff I, Herukka SK, Parkkinen L, Hartikainen P, Soininen H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid {beta}-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol 2009; 66(3):382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumurgier J, Schraen S, Gabelle A, Vercruysse O, Bombois S, Laplanche JL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta 42/40 ratio in clinical setting of memory centers: a multicentric study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015; 7(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fields JA, Spencer B, Swinton M, Qvale EM, Marquine MJ, Alexeeva A, et al. Alterations in brain TREM2 and Amyloid-beta levels are associated with neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected persons on antiretroviral therapy. J Neurochem 2018; 147(6):784–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gisslen M, Heslegrave A, Veleva E, Yilmaz A, Andersson LM, Hagberg L, et al. CSF concentrations of soluble TREM2 as a marker of microglial activation in HIV-1 infection. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2019; 6(1):e512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwamoto N, Nishiyama E, Ohwada J, Arai H. Demonstration of CRP immunoreactivity in brains of Alzheimer’s disease: immunohistochemical study using formic acid pretreatment of tissue sections. NeurosciLett 1994; 177:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poudel-Tandukar K, Bertone-Johnson ER, Palmer PH, Poudel KC. C-reactive protein and depression in persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection: the Positive Living with HIV (POLH) Study. Brain Behav Immun 2014; 42:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miranda M, Morici JF, Zanoni MB, Bekinschtein P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2019; 13:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fields J, Dumaop W, Langford TD, Rockenstein E, Masliah E. Role of neurotrophic factor alterations in the neurodegenerative process in HIV associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2014; 9(2):102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermansson L, Yilmaz A, Axelsson M, Blennow K, Fuchs D, Hagberg L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of glial marker YKL-40 strongly associated with axonal injury in HIV infection. J Neuroinflammation 2019; 16(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be made available on-line through the National NeuroAIDS Tissue Consortium.