Abstract

Background

Sleep impacts reward-motivated behaviors partly by retuning the brain reward circuits. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is a reward processing hub sensitive to acute sleep deprivation. Glutamatergic transmission carrying reward-associated signals converges in the NAc and regulates various aspects of reward-motivated behaviors. The basal lateral amygdala projection (BLAp) innervates broad regions of the NAc, and critically regulates reward seeking.

Methods

Using slice electrophysiology, we measured how acute sleep deprivation alters transmission at BLAp-NAc synapses in male C57BL/6 mice. Moreover, using stabilized step function opsin (SSFO) and DREADDs (Gi) to amplify and reduce transmission, respectively, we tested behavioral consequences following bi-directional manipulations of BLAp-NAc transmission.

Results

Acute sleep deprivation increased sucrose self-administration in mice, and altered the BLAp-NAc transmission in a topographically specific manner. It selectively reduced glutamate release at rostral BLAp (rBLAp) onto ventral and lateral NAc (vlNAc) synapses, but spared caudal BLAp (cBLAp) onto medial NAc (mNAc) synapses. Furthermore, experimentally facilitating glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses suppressed sucrose reward seeking. Conversely, mimicking sleep deprivation-induced reduction of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission increased sucrose reward seeking. Finally, facilitating rBLAp-vlNAc transmission per se did not promote either approach-motivation or aversion.

Conclusions

Sleep acts on rBLAp-vINAc transmission gain control to regulate established reward seeking, but does not convey approach-motivation or aversion on its own.

Keywords: sleep deprivation, amygdala, accumbens, reward seeking, SSFO, approach-motivation

Introduction

To our benefit or disadvantage, sleep powerfully shapes our emotional and motivational state of mind. Acute sleep disturbance in both humans and animals often leads to enhanced motivation for reward, including natural reward such as palatable food, monetary reward, and drug reward such as cocaine, nicotine, or alcohol (1–14). Functional imaging studies have revealed correlative changes in multiple brain regions following sleep deprivation (1, 4–6). However, few studies have identified causative mechanisms through which sleep regulates reward-motivated behaviors.

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is a reward processing hub that is sensitive to sleep and sleep loss (4, 5, 15–18). Functional imaging studies reveal that sleep deprivation alters the reactivity of NAc to various forms of reward (4, 5, 17, 19, 20). The extracellular levels of multiple neurotransmitters and neuromodulators in the NAc fluctuate with the sleep-wake cycles, and the functional or surface expression levels of neurotransmitter receptors are also altered by sleep deprivation (15, 16, 21). Focusing on the dorsal subregion of the NAc, our previous work identified sleep deprivation-induced changes at glutamatergic excitatory synapses that regulate food reward seeking (12). However, the expansive ventral and lateral regions of the NAc, which are increasingly recognized as a unique anatomical and functional entity in reward processing (22–25), has not been explored in this context.

The basal lateral amygdala projections (BLAp) to the NAc critically regulate reward-seeking behaviors (26–33). The BLAp innervates the NAc region in a roughly topographic manner (34–36). Using region-specific optogenetics in male mice, we differentiated the rostral BLAp (rBLAp), which preferentially innervates the ventral and lateral NAc (vlNAc), from the caudal BLAp (cBLAp), which preferentially innervates the medial NAc (mNAc). We observed that acute sleep deprivation selectively reduced glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses without affecting cBLAp-mNAc synapses. Thus, we used opto- and chemogenetic manipulations to examine the behavioral consequences of sleep-induced suppression of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Male C57BL/6 mice (Envigo), 6–8 weeks old at the beginning of the experiments, were used. Details see the Supplemental Information. Mice usage was in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh.

Viral vectors and stereotaxic surgery

All AAV vectors were obtained from University of North Carolina Vector Core. See the Supplemental Information for AAV types and titers, and stereotaxic injection sites and procedures.

EEG surgery, recordings and analysis

Surgical and recording procedures for electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG) were similar as described previously (12, 37–39), with details in the Supplemental Information. Sleep data were coded (baseline/sleep deprivation/recovery) for sleep scoring, and then decoded for data compiling.

Sleep deprivation

Gentle-handing sleep deprivation method was similar as described previously (12, 40, 41), with details in Supplemental Information.

Sucrose self-administration

Sucrose self-administration training was conducted similarly as before (12), with details described in Supplemental Information.

Imaging of viral-mediated gene expression

Expression of EYFP and mCherry at the injection and projection sites were examined as described in the Supplemental Information.

Slice electrophysiology

NAc acute slice preparation, electrophysiological recordings, and data analyses were similar as described previously (12, 42, 43). See Supplemental Information for details.

In vivo optogenetics and chemogenetics

Information about fiberoptic implantation, laser light sources/paths/intensity, clozapine N-oxide working solution preparation and in vivo application are described in detail in the Supplemental Information. For within-subject controls, mice received handling and patchcord/infusion-tubing attachment without getting laser stimulation or infusion. The mice underwent randomized, counter-balanced testing conditions. For activation or deactivation of SSFO, 473 nm and 590 nm laser light stimulations were delivered as a single train of 50-ms pulses at 10 Hz × 10 pulses (Figures 3,4,6).

Locomotor test, conditioned-place preference (CPP) test, and real-time CPP test

Locomotor test, CPP test, and real-time CPP test were performed using the typical setups for mice. Details see Supplemental Information.

Intra-cranial optical self-stimulation test

Standard operant-conditioning chambers (Med Associates, VT) equipped with active and inactive nose-poke holes were used, with details in the Supplemental Information.

Data analysis and statistics

Group sizes were determined based on power analyses using preliminary estimates of variance with the goal of achieving 80% power to observe differences at α=0.05. All data were analyzed without prior awareness of the treatment. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism GraphPad (version 7). Normal distribution was assumed for all statistics based on visual inspection and previous experience, and was not formally tested (12, 44). Homoscedasticity (equality of variance) was tested using Fisher’s F test (between 2 groups) or Levene’s test (3 or more groups) prior to t test or ANOVA test respectively (F and Levene’s testing results not shown). Statistical significance was assessed using t tests (for two-group comparisons; two-tailed tests), one-way ANOVA (single factor multiple groups), or two-way ANOVAs with or without repeated measures (RM), followed by posttests based on individual recommendations by Prism 7. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For electrophysiological recordings using behaviorally treated mice (Figure 2L,O), both cell-based and animal-based analyses were reported. For recordings using slice-based treatment (Figures 3B–G; 5B,C), slice-based analyses were reported. All others used animal-based analyses. Each experiment was replicated in 4–15 mice unless otherwise specified, or ~6–8 slices for slice-based manipulations. All data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Results

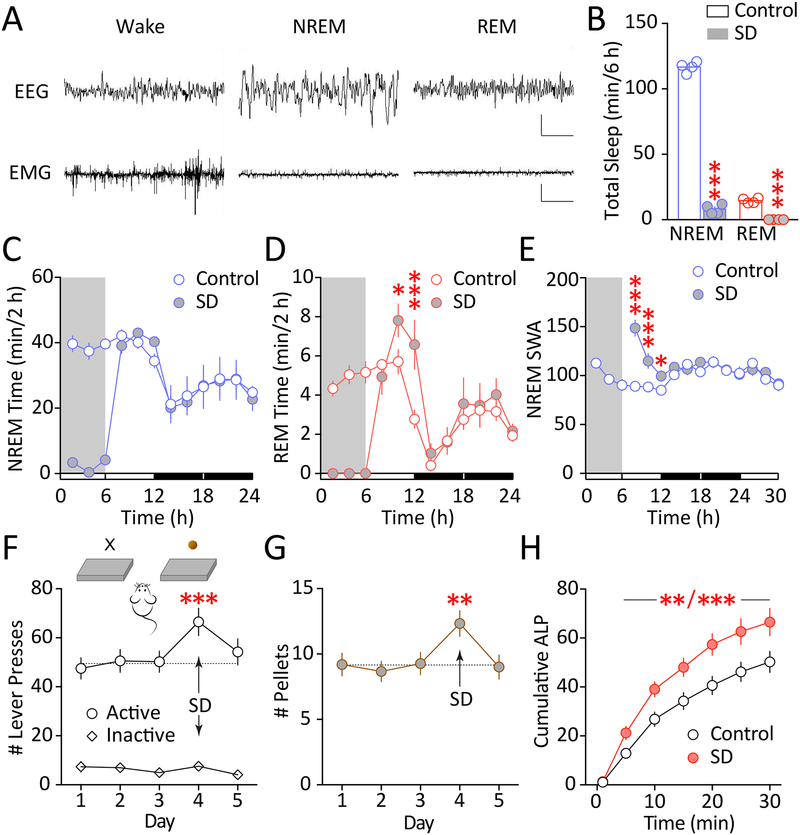

Acute sleep deprivation increases sucrose self-administration

We used the established gentle handling method for acute sleep deprivation, which introduces minimal stress without elevating stress hormone levels in mice (12, 45, 46). During the 6-hr gentle-handling, mice had a substantial loss of NREM sleep and a complete loss of REM sleep (Figure 1A,B). This resulted in a significant rebound of REM sleep time during recovery sleep (Figure 1C,D), as well as a significant rebound of slow wave activity (0.5 – 5.0 Hz; SWA) in NREM sleep during the initial phase of recovery sleep (Figure 1E), suggesting enhanced NREM sleep intensity. These results are consistent with previous observations (12, 47, 48), and verify the effectiveness of our sleep deprivation method.

Figure 1.

Acute sleep deprivation increases sucrose self-administration in mice. A Example EEG and EMG traces showing signature waveforms of wakefulness, NREM, and REM states. Scale bars = 1000 μV, 2 s. B Six hours of gentle-handling sleep deprivation procedure largely reduced NREM sleep and eliminated REM sleep (NREM, t3 = 55.4, p < 0.001; REM, t3 = 15.25, p < 0.001; paired t test). n = 4. C-D NREM (C) and REM sleep time (D) calculated in 2-hr bins during sleep deprivation and recovery sleep, showing rebound in REM sleep time (NREM × recovery time interaction: F8, 24 = 0.741, p = 0.655; main effect of recovery time: F1, 3 = 0.001, p = 0.975; REM × recovery time interaction: F8, 24 = 3.754, p < 0.01; main effect of recovery time: F1, 3 = 14.23, p < 0.05; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test). Shaded areas indicate the sleep deprivation period, light and dark time bars indicate light and dark phases. n = 4. E NREM delta power (0.5–5 Hz, normalized to the 24-hr average NREM delta power in baseline recording) during baseline sleep and recovery sleep, showing rebound of slow wave activity (SWA) during recovery NREM sleep (SWA × recovery time interaction: F11, 33 = 18.47, p < 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test). n = 4. F Mice trained to self-administer sucrose pellets by lever-pressing (inset) maintained a stable level of active lever- pressing over multiple days under an FR5 schedule. Number of active-lever presses was increased following sleep deprivation, and recovered 1 day after sleep deprivation (F4, 56 = 7.487, p < 0.001; p < 0.001 control vs. sleep deprivation, p = 0.63 control vs. recovery; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). Number of inactive-lever presses remained low throughout the days (F4, 56 = 2.307, p = 0.069, one-way RM ANOVA). n = 15. G The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a similar increase following sleep deprivation, which recovered after 1 day (F4, 56 = 7.102, p < 0.001; p < 0.01 control vs. sleep deprivation, p = 0.999 control vs. recovery; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). n = 15. H Cumulative plot of active-lever presses (ALP) for the 30-min test in 5-min bins. (Sleep deprivation × time interaction: F6, 84 = 6.663, p < 0.001; main effect of sleep deprivation: F1, 14 = 18.76, p < 0.001; main effect of time: F6, 84 = 117.3, p < 0.001; p < 0.01 or less at 5–30 min, control vs. sleep deprivation; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test). n = 15. Data shown as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

We then tested the effects of acute sleep deprivation on reward seeking by measuring sucrose self-administration in mice (Figure 1F inset; also see Supplemental Information). Despite having free access to food and water throughout the sleep deprivation period, mice showed significantly higher levels of active-lever pressing for sucrose following sleep deprivation compared to following normal sleep, which recovered 1 day after sleep deprivation; the inactive-lever pressing remained low as the baseline level (Figure 1F), suggesting a selective increase in sucrose reward seeking rather than general exploration. The mice also consumed more sucrose pellets following sleep deprivation (Figure 1G). Detailed analysis in 5-min bins revealed that the sleep deprivation-induced increase in sucrose self-administration was distributed throughout the 30-min test (Figure 1H). Of note, we showed previously that mice after the same sleep deprivation procedure do not show increased food intake (12). Thus, acute sleep deprivation enhances sucrose reward seeking and intake, which diminish after recovery sleep.

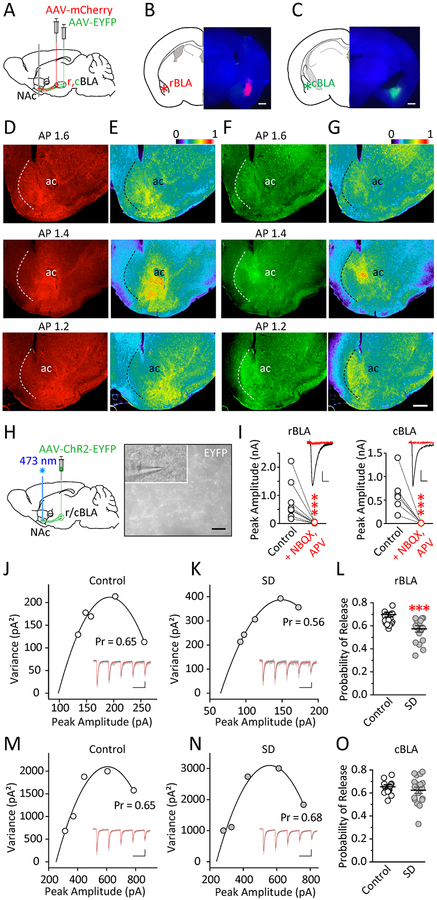

Rostral and caudal BLA inputs innervate different NAc subregions, and are subject to differential regulation by sleep deprivation.

The BLAp-NAc projection critically regulates reward seeking (26–31, 49), with widespread innervations of the NAc subregions (34–36). To differentiate the BLAp inputs, we stereotaxically injected AAV-mCherry into the rBLA and AAV-EYFP into cBLA of the same mice (Figure 2A–C), and examined BLAp-NAc fiber distributions on coronal sections of the NAc along the rostral-caudal axis. The cBLAp was largely confined within the mNAc, whereas the rBLAp projected to both the ventral medial (rostral) and ventral lateral (caudal) subregions of the NAc; on each section, the rBLAp innervated more lateral portions of the NAc compared to cBLAp (Figure 2D–G). This pattern was consistent with previous reports on the topographic organizations of BLAp-NAc projections (34–36, 50).

Figure 2.

Rostral and caudal BLA inputs innervate different NAc subregions, and are subject to differential regulation by sleep deprivation. A Virus injection and slice preparation scheme. Mice received dual injections of intra-rBLA AAV-mCherry and intra-cBLA AAV-EYFP. Coronal slices of the BLA and NAc were prepared ~6 weeks post-injection. Brain slice diagrams adapted from (104). B Three-channel overlay example image showing expression of mCherry in rBLA, with no contamination from intra-cBLA (EYFP) injection. C Three-channel overlay example image showing expression of EYFP in cBLA, with no contamination from intra-rBLA (mCherry) injection. D mCherry-expressing, rBLAp-NAc projections observed in coronal NAc slices at different anterior-posterior (AP) levels. These projections target the ventral and lateral NAc subregions along the AP axis. E Pseudocolor images of the same rBLAp projections showing relative abundance. F EYFP-expressing, cBLAp-NAc projections observed in coronal NAc slices at different AP levels. These projections target the medial NAc subregions along the AP axis. G Pseudocolor images of the same cBLAp projections showing relative abundance. B-G: Scale bars = 500 μm. n = 3 mice. H Scheme and pictures showing in vitro characterization of BLAp-NAc synaptic transmission using optogenetics in slices. AAV-ChR2-EYFP was injected into rBLA or cBLA. Six to eight weeks later, 473 nm laser light was used to stimulate ChR2-expressing terminal regions in a NAc slice while an MSN was recorded from the region. Scale bar = 25 μm. I Examples and summaries showing 473 nm laser-induced postsynaptic currents were blocked by bath application of NBQX (5 μM) and D-APV (50 μM), suggesting that both rBLA and cBLA inputs are almost exclusively glutamatergic (rBLA, t8 = 13.89, p < 0.001; cBLA, t5 = 3.76, p < 0.001; Ratio paired t test). n = 9,6 slices. Scale bars = 60 pA, 10 ms; 150 pA, 10 ms. J-K Examples of rBLAp-vlNAc AMPAR EPSCs evoked by a repeated train of 473 nm laser pulses (0.5–1 ms × 5 pulses at 20 Hz, repeated at 0.1 Hz) applied locally within the NAc, recorded from NAc MSNs at −70 mV in the presence of picrotoxin (100 μM), from mice after control sleep (J) or sleep deprivation (K). Averaged traces shown in red. The corresponding V-M plots from the EPSC trains were used to generate the parabolic fittings (solid lines) and to estimate the Pr. Scale bars = 50 pA, 50 ms; 40 pA, 50 ms. L Summarized results showing decreased Pr within rBLAp-vlNAc pathway following sleep deprivation (cell-based: t40 = 3.581, p < 0.001; animal-based: t12 = 3.59, p < 0.01; t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 18–24 cells per group from 6–8 mice each. M-N Same V-M analysis of cBLAp-mNAc transmission following control sleep (M) or sleep deprivation (N). O Summary showing non-significant change in Pr within cBLAp-mNAc pathway following sleep deprivation (cell-based: t33 = 0.924, p = 0.362; animal-based: t8 = 0.702, p = 0.503; t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 4–6 mice each. Scale bars = 200 pA, 50 ms; 200 pA, 50 ms. Data shown as mean ± SEM. *** p < 0.001

Fast synaptic transmission through both rBLA and cBLA projections to the NAc was exclusively glutamatergic, as optogenetic stimulation of the ChR2-expressing rBLAp or cBLAp inputs induced postsynaptic currents that were abolished by the AMPA and NMDA receptor antagonists NBQX (5 μM) and D-APV (50 μM) (Figure 2H,I).

Is the BLAp-NAc transmission affected by sleep deprivation? We examined the basal synaptic transmission efficacy of rBLAp and cBLAp using the optogenetically based nonstationary variance-mean (V-M) analysis (12, 43, 51) (also see Supplemental Information). Mice received intra r/cBLA injections of AAV vectors expressing ChR2-EYFP, and V-M analysis was performed 6–8 weeks later. Quantal parameters of neurotransmitter release were estimated based on the size and variability of light-evoked postsynaptic responses (52–54), and the probability of release (Pr) is typically reliably extracted from such analysis in NAc slice preparations (12, 43, 51). Following sleep deprivation, there was a selective reduction of Pr at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses (Figure 2J–L), but not at cBLAp-mNAc synapses (Figure 2M–O). These results suggest that sleep deprivation selectively reduces rBLAp-vlNAc, but not cBLAp-mNAc, transmission by decreasing presynaptic release probability.

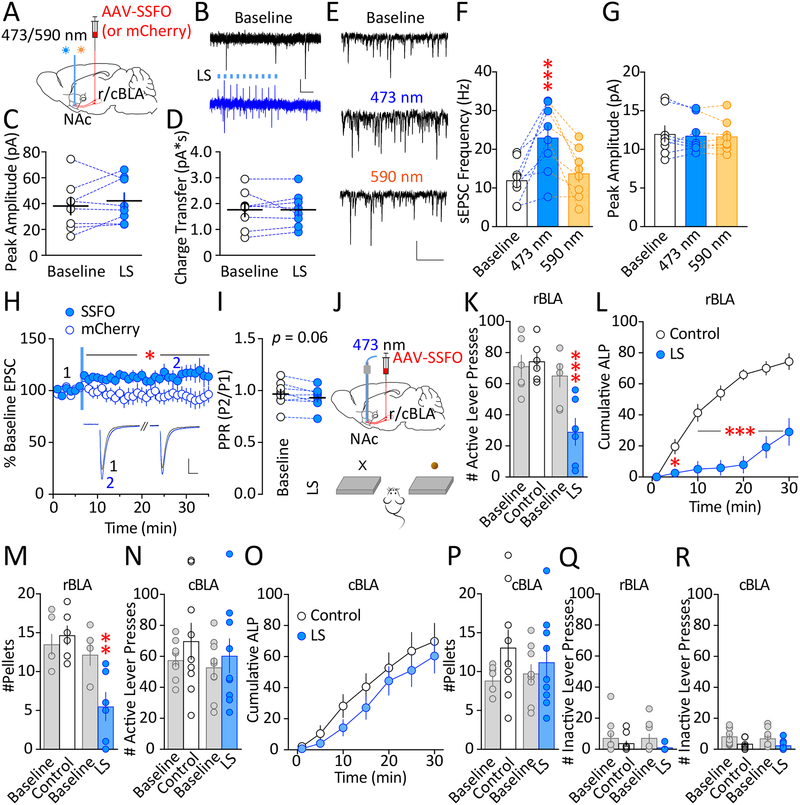

Enhancing transmission efficacy at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses reduces sucrose seeking and counteracts sleep deprivation effects

May sleep deprivation-induced changes in rBLAp-vlNAc transmission contribute to altered reward seeking in sleep-deprived mice (Figure 1F–H)? We then used optogenetic and chemogenetic approaches to achieve bidirectional manipulations of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission. SSFO is a modified ChR2 with modest but persistent cation channel activity (deactivation τ ~29 min) upon light activation (55). We previously showed that SSFO activation in the axon terminals facilitates endogenous action potential-dependent transmitter release (12). To validate this approach at BLAp-NAc synapses, we expressed AAV-SSFO-mCherry (or mCherry alone) in the rBLA or cBLA, and applied laser stimulation in the NAc (Figure 3A). Data for rBLAp and cBLAp were similar and thus combined for validation purposes. In NAc slices, a brief 473 nm laser stimulation (50 ms at 10 Hz × 10 pulses) of SSFO-expressing BLAp did not directly elicit postsynaptic currents (Figure 3B–D). However, immediately following laser stimulation there was a persistent increase in the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs, with no changes in the amplitude (Figure 3E–G), suggesting an increase in presynaptic release probability. Furthermore, the increase in spontaneous EPSC frequency was terminated by 590 nm laser stimulations (Figure 3E–G), as predicted by 590-nm light-mediated closure mechanism of SSFO (55). Finally, to test whether SSFO activation persistently enhances action potential-dependent transmitter release at BLAp-NAc synapses, we recorded electrically evoked EPSCs in NAc MSNs at mCherry-expressing axon-dense regions (i.e., presumed BLAp-NAc inputs). Following the same brief 473 nm laser stimulation in NAc slices, there was a persistent increase in the electrically evoked EPSC peak amplitude in SSFO-expressing group compared to mCherry-only control group (Figure 3H), accompanied by a trend decrease in paired-pulse ratio (PPR; Figure 3I), suggesting enhanced probability of release. Together, these results verify that a brief light activation of SSFO at r/cBLAp-NAc terminals induces prolonged facilitation of action potential-dependent glutamatergic transmission.

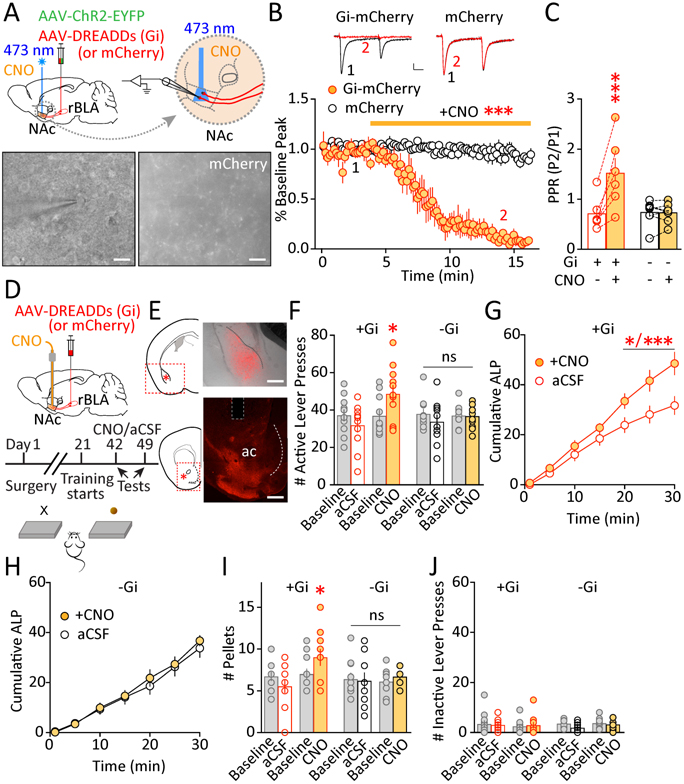

Figure 3.

Enhancing endogenous glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc, but not cBLAp-mNAc, synapses reduces sucrose self-administration. A Scheme showing intra-r/cBLA injection of AAV-SSFO-mCherry and laser stimulation (LS) in the NAc. B-D Examples (B) and summaries showing non-significant changes in either peak amplitude (C) or charge transfer (D) during the LS train (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz; peak amplitude, t7 = 0.959, p = 0.369; charge transfer, t7 = 0.016, p = 0.988; paired t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 8 slices. A 10 s baseline prior to LS was measured for peak amplitude (average of the maximum peak amplitude from each second) and charge transfer (average per second). For LS, the peak amplitude and charge transfer were measured for the 1 s starting at LS onset. Scale bars = 10 pA, 200 ms. E Example spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) at baseline, following 473 nm, then 590 nm laser stimulations (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz) recorded from an MSN in the NAc. Scale bars = 20 pA, 500 ms. F Summary showing an increase in sEPSC frequency following 473 nm laser stimulation (F2,14 = 15.8, p < 0.001), and recovery following subsequent 590 nm laser stimulation (p = 0.680 compared to baseline, one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). G Summary showing non-significant changes in sEPSC amplitude following 473 nm, and subsequent 590 nm laser stimulation (F2,14 = 0.343, p = 0.715; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). A 3-min period starting at each laser-light offset was measured. n = 8 slices. H-I Example and summary of AMPAR EPSCs evoked by paired-pulse electrical stimulations (100 ms inter-pulse interval) in NAc MSNs before and after 473 nm laser stimulation (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz), showing laser-induced increase in EPSC peak amplitude (normalized to the baseline before LS; compared to mCherry control, SSFO × time post-stimulation: F25, 350 = 0.878, p = 0.637; main effect of SSFO: F1, 14 = 4.879, p < 0.05; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test; H), with a trend decrease in PPR (peak2/peak1; t7 = 2.238, p = 0.06; paired t test; I). Numbers 1 and 2 indicate when the averaged traces were recorded; blue line indicates when laser stimulation occurred. Slices with mCherry-only expression and receiving 473 nm laser stimulation were used as the control group. n = 8 slices each. J Scheme of intra-r/cBLA injection of AAV-SSFO-mCherry and 473 nm laser stimulation in the NAc in vivo. Mice were trained to perform sucrose self-administration. K Baselines and testing levels of active-lever pressing under control conditions (no LS) and 473 nm laser stimulation (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz) of rBLAp-vlNAc projections, showing a decrease of active-lever pressing following laser stimulation (F3,15 = 10.69, p < 0.001; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). n = 6. L Cumulative plot of active-lever pressing (ALP) for the 30-min test in 5-min bins. (LS × time interaction: F6, 30 = 14.1, p < 0.001; main effect of LS: F1, 5 = 46.33, p = 0.001; main effect of time: F6, 30 = 60.75, p < 0.001; p < 0.05 or p < 0.001 at 5 – 30 min, control ± LS; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test). n = 6. M The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a similar decrease following stimulation of rBLAp-vlNAc projections (F3,15 = 11.92, p < 0.001, p < 0.01 control ± LS; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). n = 6 (some individual data points overlap). N Baselines and testing levels of active-lever pressing under control conditions (no LS) and 473 nm laser stimulation (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz) of cBLAp-mNAc projections, showing a non-significant change of active-lever pressing following laser stimulation (F3,24 = 1.634, p = 0.208; one-way RM ANOVA). n = 9. O Cumulative plot of active-lever pressing (ALP) for the 30-min test in 5-min bins. (Sleep deprivation × time interaction: F6, 48 = 0.507, p = 0.802; main effect of LS: F1, 8 = 0.879, p = 0.363; main effect of time: F6, 48 = 61.52, p < 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA). n = 9. P The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a non-significant change following stimulation of cBLAp-mNAc projections (F3,24 = 2.904, p = 0.092; one-way RM ANOVA). n = 9. Q-R The number of inactive-lever pressing was not significantly different following either rBLAp (Q) or cBLAp (R) input stimulations compared to the respective no-stimulation controls (rBLAp-vlNAc: F3,15 = 2.274, p = 0.122; cBLAp-mNAc: F3,24 = 7.134, p < 0.01, p = 0.898 LS compared to control; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). Data shown as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

We then deployed the SSFO approach in vivo to test whether strengthening r/cBLAp-NAc transmission alters sucrose seeking. Mice received intra-rBLA or cBLA injections of AAV-SSFO-mCherry, and bilateral guide cannula implantation above the corresponding NAc subregions (Figure 3J). 6–8 weeks later, a brief 473 nm laser stimulation at rBLAp-vlNAc inputs resulted in a significant reduction in subsequent active-lever pressing for sucrose (Figure 3K). The reduction persisted throughout the 30-min testing session, with a particularly low rate of self-administration during the first 20 min (Figure 3L). As a result, the sucrose pellet consumption was also reduced following laser stimulation (Figure 3M). By contrast, laser stimulation of cBLAp-mNAc projection did not affect sucrose self-administration assessed either as 30-min total (Figure 3N), or in 5-min bins (Figure 3O), nor did it change sucrose pellet consumption (Figure 3P). Finally, inactive-lever pressing was not altered (Figure 3Q,R), suggesting that SSFO-induced reduction of sucrose self-administration was not likely due to general behavioral suppression. Thus, an enhanced efficacy of rBLAp-vlNAc synaptic transmission, but not cBLAp-mNAc transmission, reduces sucrose reward seeking.

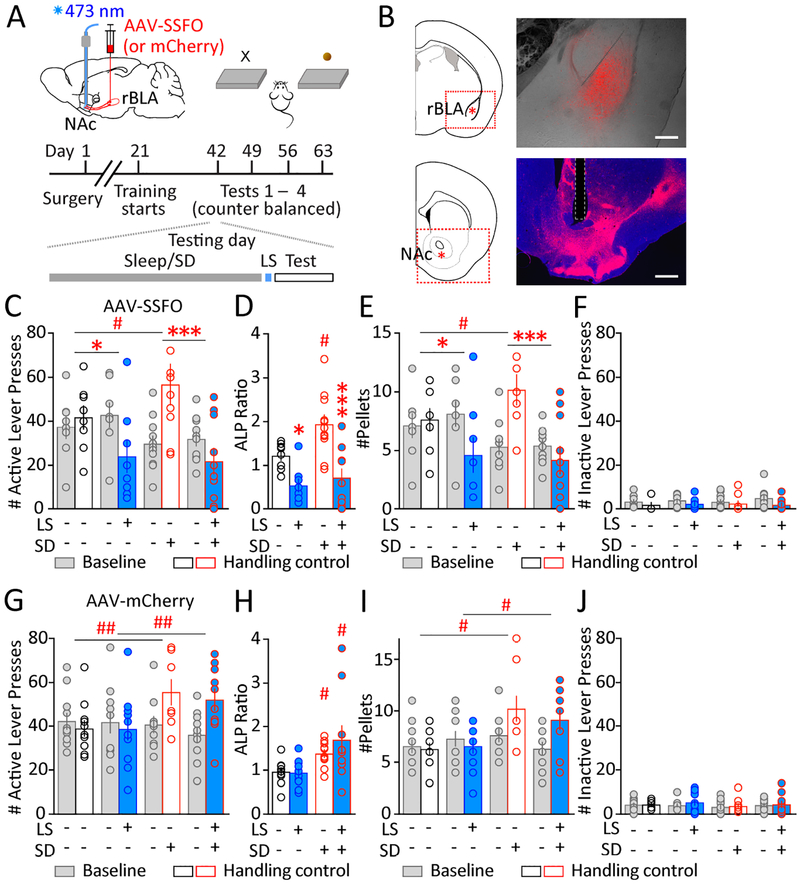

How may this affect sleep deprivation-induced increase in sucrose self-administration? Mice underwent the same surgeries and sucrose self-administration training (Figure 4A,B). 6–8 weeks post-surgery, the mice were tested under four different conditions over a period of 4–6 weeks (Figure 4A). Because of minor fluctuations in the baseline performance during the 4-week testing period, we present both the baseline and the testing active-lever pressing results, and used their ratios (test/baseline) for statistical analyses. As shown in Figure 4C,D, acute sleep deprivation increased sucrose self-administration, and laser stimulation reduced sucrose self-administration. Laser stimulation did not eliminate sucrose self-administration entirely, but reduced it to a greater extent in sleep-deprived mice, such that following stimulation, there was no significant difference between control-sleep and sleep-deprived groups (p = 0.772; Sidak post-test). These results suggest that SSFO activation interferes with sleep mechanisms rather than imposes an independent, overall suppression of sucrose self-administration. The number of sucrose pellets consumed followed similar patterns (Figure 4E). Additionally, the number of inactive-lever pressing was similar in all baseline and testing conditions (Figure 4F), suggesting that the laser stimulation-induced decrease in sucrose seeking after sleep deprivation was not due to a non-specific suppression of lever pressing. Thus, selectively strengthening the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy reduces sucrose self-administration, counteracting the effect of sleep deprivation.

Figure 4.

Enhancing endogenous glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses counteracts sleep deprivation-induced increase in sucrose self-administration. A Scheme of intra-rBLA injection of AAV-SSFO-mCherry and 473 nm laser stimulation in the NAc in vivo. Mice were trained to perform sucrose self-administration. (Bottom) Timeline of surgery, training and testing, including the order of events on the testing day. B Expression of AAV-SSFO-mCherry at the rBLA injection site (top) and mCherry-expressing axons in the NAc (bottom) on coronal brain sections. Scale bars = 500 μm. C-F Sucrose self-administration tests in mice with SSFO expression in rBLAp-vlNAc. LS = 473 nm laser light, 50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz. n = 8–11 (some individual data points overlap). C Baselines and testing levels of active-lever pressing under four conditions: normal sleep/sleep deprivation × no LS (handling control)/LS, showing LS-induced decrease of active-lever pressing both following normal sleep and following sleep deprivation. D Active-lever pressing (ALP) ratios (test/baseline) under the four conditions, showing LS-induced decrease of ALP both following normal sleep and following sleep deprivation (sleep deprivation × LS interaction: F1, 33 = 2.026, p = 0.164; main effect of sleep deprivation, F1, 33 = 5.505, p < 0.05; main effect of LS, F1, 33 = 25.16, p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). E The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a similar pattern. Pellet ratios (test/baseline) were used for statistics. (Sleep deprivation × LS interaction: F1, 33 = 3.296, p = 0.079; main effect of sleep deprivation: F1, 33 = 9.384, p < 0.01; main effect of LS: F1, 33 = 26.63, p < 0.001; control ± LS, p < 0.05; sleep deprivation ± LS, p < 0.001; LS vs. sleep deprivation + LS, p = 0.626; two-way ANOVA with Sidak post-test). F The number of inactive-lever pressing was not significantly different across all baselines and testing conditions (F7, 66 = 1.05, p = 0.406; one-way ANOVA). G-J Sucrose self-administration tests in control mice that had mCherry expression in rBLAp-vlNAc. LS = 473 nm laser stimulation, 50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz. n = 10–11 (some individual data points overlap). G Baselines and testing levels of active-lever pressing under four conditions: normal sleep/sleep deprivation × no LS (handling control)/LS, showing a main effect of sleep deprivation but not LS. H Active-lever pressing (ALP) ratios (test/baseline) under the same four conditions, showing a main effect of sleep deprivation but not LS (sleep deprivation × LS interaction: F1, 38 = 0.954, p = 0.335; main effect of sleep deprivation: F1, 38 = 11.71, p < 0.01; main effect of LS: F1, 38 = 0.747, p = 0.393; two-way ANOVA). I The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a similar pattern. Pellet ratios (test/baseline) was used for statistics. (Sleep deprivation × LS interaction: F1, 38 = 1.437, p = 0.238; main effect of sleep deprivation: F1, 38 = 8.605, p < 0.01; main effect of LS: F1, 38 = 0.467, p = 0.499; two-way ANOVA). J The number of inactive-lever pressing was not significantly different across all baselines and testing conditions (F7, 76 = 0.371, p = 0.917; one-way ANOVA). Data shown as mean ± SEM. # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 (compared to control sleep); * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 (compared to without LS).

Finally, we verified that the laser stimulation per se did not alter sucrose self-administration, using mice that had mCherry alone expressed at rBLAp-vlNAc terminals (Figure 4G,H). Moreover, laser stimulation did not alter the expected levels of sucrose self-administration in mice with either control-sleep (p = 0.996) or sleep deprivation (p = 0.378; Sidak post-test). The number of sucrose pellets consumed followed similar patterns (Figure 4I). Inactive-lever pressing was similar in all conditions (Figure 4J).

Mimicking sleep deprivation-induced suppression of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission increases sucrose seeking

Is it sufficient for sleep deprivation-induced suppression of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission to increase sucrose seeking? To test this, we expressed the Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) hM4D (Gi-coupled) or mCherry alone in the rBLA. A second vector, AAV-ChR2, was co-injected in rBLA to allow optogenetic activation of rBLAp-vlNAc projection for electrophysiological characterizations (Figure 5A). 6–8 weeks post-surgery, laser-evoked EPSCs at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses were effectively inhibited by bath application of clozapine N-oxide (CNO, 10 μM; Figure 5B), which was accompanied by an increase in the paired-pulse ratio (Figure 5C). These results suggest that DREADDs (Gi) expression at rBLAp-vlNAc terminals effectively reduces glutamate release probability in response to CNO.

Figure 5.

Mimicking sleep deprivation-induced reduction of glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses increases sucrose self-administration. A Scheme of intra-rBLA injection of mixed AAV-ChR2-EYFP and AAV-DREADDs (Gi)-mCherry (or AAV-mCherry instead). 473 nm laser light was directed to the NAc in slices, and CNO was bath applied, while laser-evoked EPSCs were recorded from the MSNs. (Bottom) A patch electrode onto an MSN in an mCherry-expressing axon-rich region in the NAc (scale bars = 25 μm). B-C Examples and summaries of AMPAR EPSCs evoked by paired-pulse laser stimulations (~1 ms, 473 nm laser pulses at 100 ms inter-pulse interval) in NAc MSNs before and after CNO application (10 μM), showing CNO-induced decrease in EPSC peak amplitude (normalized to the baseline; % inhibition at 10 min after CNO application, 98.6 ± 0.03%, t12 = 20.42, p < 0.001 compared to mCherry; t test; B), with an increase in PPR (peak2/peak1, 10 min after CNO application, Gi × CNO interaction: F1, 12 = 23.67, p < 0.001; Gi ± CNO: p < 0.001; mCherry ± CNO: p = 0.998; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test; C). Numbers 1 and 2 indicate when the averaged traces were recorded. Slices with mCherry-only expression and receiving CNO application were used as the control group. n = 6–8 slices each. Scale bars = 50 pA, 25 ms. D Schematic view of intra-rBLA injection of AAV-DREADDs (Gi)-mCherry (or AAV-mCherry) and intra-NAc infusion of CNO. Mice were trained to perform sucrose self-administration. Timeline of surgery, training and testing. E Expression of AAV-DREADDs (Gi)-mCherry at the rBLA injection site (top) and mCherry-expressing axons in the NAc (bottom) on coronal brain sections. Scale bars = 500 μm. F Baselines and testing levels of active-lever pressing following intra-NAc infusions of CNO or vehicle (aCSF), showing an increase of active-lever pressing following CNO infusion in DREADDs (Gi)-expressing mice (F3,30 = 4.315, p < 0.05; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). Mice with intra-rBLA mCherry expression were used as additional controls (F3, 27 = 0.758, p = 0.528; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). n = 10–11 each group (some individual data points overlap). G-H Cumulative plot of active-lever pressing (ALP) for the 30-min test in 5-min bins following intra-NAc infusions of CNO or vehicle in DREADDs (Gi)-expressing mice (time × drug interaction: F6, 60 = 3.574, p < 0.01; main effect of CNO F1, 10 = 6.606, p < 0.05; p < 0.05 or 0.001 at 20–30 min; two-way RM ANOVA with Sidak post-test; n = 11; G) or mCherry-expressing mice (F6, 54 = 0.502, p = 0.804; two-way RM ANOVA; n = 10; H). I The number of sucrose pellets consumed showed a similar increase following CNO-inhibition of rBLAp-vlNAc projections (Gi: F3,30 = 4.686, p < 0.01; mCherry: F3,27 = 0.310, p = 0.818; one-way RM ANOVA with Tukey post-test). n = 10–11 each group (some individual data points overlap). J The number of inactive-lever pressing was not significantly different across all baselines and testing conditions (Gi: F3,30 = 0.181, p = 0.908; mCherry: F3,27 = 1.954, p = 0.145; one-way RM ANOVA). Data shown as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, ns = not significant

We then tested the behavioral consequences of reducing transmission at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses on sucrose seeking. Mice received bilateral intra-rBLA injections of AAV-DREADDs(Gi)-mCherry, or AAV-mCherry as a control, and bilateral intra-vlNAc implantation of guide cannula (Figure 5D,E; Supplemental Information). 6–8 weeks later, mice received intravlNAc infusions of either CNO (2 mM, 0.5 μl/side × 2 sides) or vehicle (aCSF) prior to the operant test. In DREADDs(Gi)-expressing mice, intra-vlNAc infusion of CNO increased active-lever pressing for sucrose compared to aCSF infusion, and the effect was absent in mCherry-expressing mice (Figure 5F), suggesting that the effect of CNO was mediated by DREADDs(Gi). The time course in 5-min bins revealed that the CNO-induced increase in sucrose self-administration was predominantly during the 2nd half of the 30-min test (Figure 5G). This was not observed in mCherry-expressing mice (Figure 5H). Consumption of sucrose pellets followed similar patterns (Figure 5I). Inactive-lever pressing was similar among all conditions (Figure 5J). Together, these results suggest that reducing glutamate release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses facilitates sucrose seeking, mimicking the behavioral effects of sleep deprivation.

Facilitating rBLAp-vlNAc transmission does not convey motivational salience

The above results suggest that enhancing rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy negatively modulates reward seeking. Thus, could it induce a form of behavioral aversion? We noticed that mice receiving SSFO-stimulation of rBLAp-vlNAc projection did not show altered spontaneous locomotor activity when tested in a novel environment (Figure 6A), but showed decreased the locomotor activity when tested in chambers they were familiar with (Figure 6B). These results suggest that enhancing transmission efficacy at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses may reduce the motivation to explore in a familiar environment, although it does not lead to gross impairment of locomotor activity.

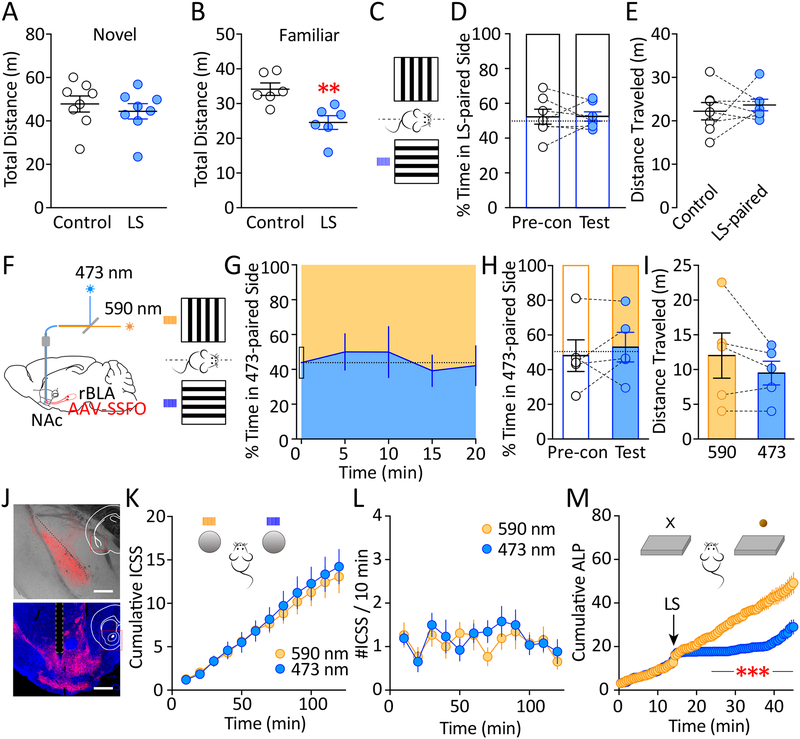

Figure 6.

Facilitating rBLAp-vlNAc transmission was neither rewarding nor aversive. A Spontaneous locomotor activity test in a novel environment, showing non-significant difference in total distance traveled during the 30 min test under control conditions (no LS) or following intra-NAc LS (473 nm, 50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz; compared to without LS: t7 = 1.361, p = 0.216; paired t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 8. B Spontaneous locomotor activity test in a familiar environment, showing a decrease in total distance traveled during the 30 min test following intra-NAc LS compared to control (no LS; t5 = 4.226, p < 0.01; paired t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 6. C Mice were tested for conditioned-place preference, where a randomly chosen side of the chamber was paired with LS (473 nm blue light, 50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz), and the other side was paired with no stimulation. D %Time spent in laser-paired side of the CPP chamber for each individual mouse during pre-conditioning and after the 10-day pairing. There was no significant difference between pre-conditioning and after pairing (t6 = 0.037, p = 0.972; paired t test). n = 7. E There was no significant difference in the distance traveled in the LS-paired or no-LS-paired (control) side of the chamber during CPP test after the 10-day pairing (t6 = 0.569, p = 0.590; paired t test). Thick lines represent group means and SEM. n = 7. F Schematic view of intra-rBLA injection of AAV-SSFO-mCherry, and converging light paths for 473 nm and 590 nm laser lights to be directed to the NAc in vivo (see Supplemental Information). LS = 50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz. G %Time spent in 473 nm (blue)-paired side of the CPP chamber during the 20 min test in 5-min bins, starting at the pre-conditioning level. No preference of either side was developed during the test (F4,20 = 0.653, p = 0.632; one-way RM ANOVA). n = 5. H %Time spent in 473 nm-paired side of the CPP chamber for each individual mouse during pre-conditioning and real-time CPP testing. There was no significant difference between pre-conditioning and during real-time pairing (t4 = 0.694, p = 0.526, paired t test). n = 5. I There was no significant difference in the distance traveled in the 473 nm (blue) laser-paired or 590 nm (yellow) laser-paired side of the chamber during real-time CPP test (t4 = 1.418, p = 0.229, paired t test). n = 5. J Expression of AAV-SSFO-mCherry at the rBLA injection site (top) and mCherry-expressing axons in the NAc (bottom) on coronal brain sections. Scale bars = 500 μm. K Cumulative ICSS reinforcement for either 473 nm or 590 nm LS (50 ms × 10 pulses at 10 Hz) during the 2 hr testing period. There was no significant difference between choosing blue or yellow LS throughout the testing period (time × LS interaction: F11, 132 = 1.422, p = 0.170; main effect of LS: F1, 12 = 0.298, p = 0.595; two-way RM ANOVA;). n = 13. L There was no change in the rate of ICSS of either LS over the course of the test (#ICSS/10 min, time × LS interaction: F11, 132 = 0.746, p = 0.692; main effect of time: F11, 132 = 1.688, p = 0.083; main effect of LS: F1, 12 = 1.182, p = 0.298; two-way RM ANOVA). n = 13. M The same mice receiving the same LS (except one that lost the fiber implants) during on-going sucrose self-administration showed immediate suppression of active-lever pressing (ALP) following 473 nm, but not 590 nm, LS (time × LS interaction: F41, 451 = 20.54, p < 0.001; main effect of time: F41, 451 = 26.58, p < 0.001; main effect of LS: F1, 11 = 19.48, p = 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA). n = 12. Data shown as mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

We next used a conditioned-place preference (CPP) setup to test whether facilitation of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission produces aversive or rewarding responses. Mice received bilateral rBLA injections of AAV-SSFO, and intra-vlNAc bilateral implantations of optic fibers. Intra-vlNAc laser stimulation of SSFO-expressing nerve terminals was paired with one randomly selected side of the CPP chamber, and no laser stimulation was paired with the other side (Figure 6C). This conditioning did not induce CPP (or aversion) after 10 days of pairing (Figure 6D), and mice showed similar locomotor activity during the test in either side of the chamber (Figure 6E). These results suggest that enhancing transmission efficacy at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses does not produce a memorable rewarding or aversive experience.

To further test the acute rewarding or aversive effects, we did real-time CPP test in a separate cohort of mice following the same surgical procedures. 473-nm or 590-nm laser light was directed into vlNAc via a combined light path (Figure 6F; Supplemental Information). While mice moved freely between the two sides of the chamber, intra-vlNAc 473 nm laser stimulation (SSFO activation) was paired with one randomly selected side, and 590 nm laser stimulation (SSFO deactivation) was paired with the other side (Figure 6F). Neither laser stimulation elicited freezing responses (data not shown). Compared to pre-conditioning, mice did not show preference to either side of the chamber over a 20-min testing period (Figure 6G). Overall, mice spent a comparable amount of time in either laser-paired side compared to preconditioning (Figure 6H), and traveled similar amount of distance in either laser-paired side during the test (Figure 6I). These results suggest that enhancing the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy is neither aversive nor rewarding under both chronic and acute (real-time) CPP testing conditions.

Previous studies showed that stimulating the BLAp-NAc transmission is positively reinforcing and establishes intra-cranial self-stimulation (ICSS) (26, 27), a defining readout of incentive salience. Therefore, we tested whether enhancing the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy produces rewarding experience and establishes ICSS. In a separate cohort of mice following the same surgical procedures (Figure 6J), 473-nm or 590-nm laser lights were directed into the vlNAc via a shared light path (Figure 6F). Mice were randomly assigned to one of two parallel groups which received laser stimulation upon nose-poke in one of the two holes (right/left) in the operant chamber (473/590; or 590/473), and were tested twice (one week apart) in a counter-balanced manner. Over a 2-hr testing period, mice did not develop preference to 473- or 590-nm laser stimulation when both choices were available (Figure 6K), and did not establish ICSS for either laser stimulation (Figure 6L). These results suggest that enhancing the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy does not directly produce positive or negative reinforcement. Importantly, the same mice exhibited strong inhibition of sucrose self-administration upon 473 (but not 590) nm laser stimulation during the on-going sucrose seeking test (Figure 6M). Together, these results suggest that rather than directly producing motivational salience, regulation of the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy may shape the behavioral outcome of established saliences.

Discussion

Sleep disturbance alters the motivational state (56–63), but the specific circuit mechanisms are not well understood. Here we show that acute sleep deprivation selectively reduces the rBLAp-vlNAc transmission efficacy, resulting in increased sucrose reward seeking. In addition, enhancing the gain of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission does not produce reward or aversion per se, yet it negatively regulates established sucrose reward seeking. These results reveal a novel gain-control mechanism at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses, through which sleep regulates reward-seeking behaviors.

Sleep-mediated regulation of NAc excitatory transmission

The NAc is devoid of local glutamatergic neurons, but it receives dense glutamatergic innervations from throughout the limbic forebrain. In addition to rBLAp-vlNAc inputs, previous studies also identified medial prefrontal cortical projection (mPFCp)-NAc transmission being presynaptically suppressed by acute sleep deprivation (12). By contrast, such suppression of glutamate release was not observed at cBLA, thalamic, or hippocampal inputs to the NAc following acute sleep deprivation (12). Thus, acute sleep deprivation may shift the balance among glutamatergic pathways that drive the NAc circuit toward a state favoring reward seeking.

Additionally, glutamatergic inputs to the NAc exhibit biased innervation onto different neuronal subtypes. For example, a number of glutamatergic projections differentially innervate MSNs that express dopamine D1 receptors vs. those expressing dopamine D2 receptors (64, 65), and glutamatergic inputs onto the NAc fast spiking interneurons (FSIs) often outweigh the same projections onto MSNs (66). It remains to be determined whether the rBLAp-vlNAc projection exhibits preferential innervation of D1, D2 MSNs, or FSIs, and whether sleep deprivation offsets such balance. This may be directly relevant to sleep-regulation of reward, as D1 and D2 MSNs are often differentially involved in reward-elicited behaviors (67–72), and that NAc FSIs also regulate behavioral preference or aversion presumably through regulating MSN activity (66, 73–77). Finally, D1 MSNs in the ventral medial versus lateral NAc differentially regulate reward-associated behaviors based on their target neuronal types within the ventral tegmental area (23). Thus, defined by different source inputs, NAc subregions, cell types, and downstream targets, the NAc glutamatergic transmission may be selectively affected by sleep deprivation, resulting in shifted local circuit dynamics and altered reward processing.

It remains to be determined the molecular substrates that mediate the suppression of glutamatergic transmission following sleep deprivation. Both adenosine- and dopamine-signaling pathways are potential candidates. Their signaling pathways directly impact NAc transmission and regulate reward (78–89), and both adenosine levels and dopamine receptor signaling are altered by sleep deprivation (21, 90, 91). However, it is less clear how these and other neural modulator systems may differentially affect different NAc afferents.

rBLAp-vlNAc gain control and approach-motivation valence vs. intensity

Thus far, we have identified two main glutamatergic inputs that are sensitive to acute sleep deprivation: mPFCp and rBLAp. Compared to mPFCp-NAc, which is thought to convey top-down inhibitory control (12, 92–96), rBLAp-vlNAc inputs are less well characterized as to the information they encode. Our results show that decreasing rBLAp-vlNAc transmission mimics the sleep deprivation effect and increases sucrose self-administration, and vice versa. These results do not support a state of “memory deficiency” following sleep deprivation, nor do they support a role of rBLAp-vlNAc transmission in facilitating reward seeking. Rather, these results suggest a functional similarity between rBLAp-vlNAc and mPFCp-NAc transmission, which provides inhibitory control of sucrose reward seeking following normal sleep (12).

Conventionally, the overall BLAp-NAc transmission is thought to convey reward-associated cues, which is often positively reinforcing upon activation – ChR2-stimulation of these projections promotes CPP, ICSS, as well as facilitates natural and drug reward-seeking (26–31). However, our results show that selectively increasing the likelihood of presynaptic release at rBLAp-vlNAc synapses reduces sucrose seeking, without imposing positive or negative motivational valence (Figure 6). These different outcomes may be assessed on two main considerations. On the one hand, the SSFO approach differs from the previous ChR2 approach in that it alters the transmission efficacy without imposing direct, artificial stimulation of the pathway. On the other hand, NAc subregions may play differential, sometimes opposing, roles in regulating reward seeking behaviors. For example, dorsal versus ventral NAc D1 MSNs drive reward versus aversive behaviors respectively (22), and the medial versus lateral NAc shell also differentially regulates reward seeking behaviors (23). Interestingly, it is recently shown that activation of the ventral medial (adjacent to ventral lateral) NAc D1 MSN projections within the target ventral tegmental area induces behavioral suppression without eliciting reward or aversion (23). It remains to be determined whether rBLAp-vlNAc inputs feed into this pathway. Together, a parsimonious conclusion from current study is that rBLAp-vlNAc gain-control modulates the approach-motivation intensity without assigning an approach-motivation valence (see below).

The perception of reward, or positive affects, varies in the approach motivational intensity. Some, such as “contentment” and “serenity”, are low in approach-motivation, whereas others, such as “desire” and “interest”, are high (97, 98). Such differences in the approach-motivation “intensity” may involve different neural circuits (97–102), and can be influenced by motivationally neutral sensory stimuli, as demonstrated in nicotine reward seeking (103). A “neutral” signal (e.g., positive affect low in approach-motivation) may provide a unique leverage to reduce the drive for “undesired” rewards as compared to strategies involving “aversive” (e.g., punishment) signal. One such example could be to amplify a “contentment” signal that is potentially “motivationally neutral” (Figure 6), while having negative effects on exploring a familiar environment (Figure 6B) or seeking reward (Figures 3,4,6). It remains to be determined whether the rBLAp-vlNAc gain control may be generalizable to regulating other types of reward-seeking behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We thank Dr. Yavin Shaham for reading an earlier version of the manuscript. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers DA035805 (YH), MH101147 (YH), DA047108 (YH), DA043826 (YH), DA046491 (YH), DA023206 (YD), DA040620 (YD), DA047861 (YD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Gujar N, Yoo SS, Hu P, Walker MP (2011): Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 31:4466–4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna BS, Dickinson DL, Orff HJ, Drummond SP (2007): The effects of one night of sleep deprivation on known-risk and ambiguous-risk decisions. J Sleep Res. 16:245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Galvan A (2013): The effects of poor quality sleep on brain function and risk taking in adolescence. NeuroImage. 71:275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatraman V, Chuah YM, Huettel SA, Chee MW (2007): Sleep deprivation elevates expectation of gains and attenuates response to losses following risky decisions. Sleep. 30:603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatraman V, Huettel SA, Chuah LY, Payne JW, Chee MW (2011): Sleep deprivation biases the neural mechanisms underlying economic preferences. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 31:3712–3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Walker MP (2013): The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nature communications. 4:2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Hall JM (1998): Polysomnographic and subjective sleep predictors of alcoholic relapse. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 22:1864–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killgore WD, Balkin TJ, Wesensten NJ (2006): Impaired decision making following 49 h of sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 15:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhl MD, Boisvert M, Guan Z, Fang J, Grigson PS (2013): A novel model of chronic sleep restriction reveals an increase in the perceived incentive reward value of cocaine in high drug-taking rats. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 109:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puhl MD, Fang J, Grigson PS (2009): Acute sleep deprivation increases the rate and efficiency of cocaine self-administration, but not the perceived value of cocaine reward in rats. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 94:262–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner SS, Ellman SJ (1972): Relation between REM sleep and intracranial self-stimulation. Science. 177:1122–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Wang Y, Cai L, Li Y, Chen B, Dong Y, et al. (2016): Prefrontal Cortex to Accumbens Projections in Sleep Regulation of Reward. J Neurosci. 36:7897–7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamidovic A, de Wit H (2009): Sleep deprivation increases cigarette smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 93:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Short NA, Mathes BM, Gibby B, Oglesby ME, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB (2017): Insomnia symptoms as a risk factor for cessation failure following smoking treatment. Addict Res Theory. 25:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sardi NF, Tobaldini G, Morais RN, Fischer L (2018): Nucleus accumbens mediates the pronociceptive effect of sleep deprivation: the role of adenosine A2A and dopamine D2 receptors. Pain. 159:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lena I, Parrot S, Deschaux O, Muffat-Joly S, Sauvinet V, Renaud B, et al. (2005): Variations in extracellular levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate, and aspartate across the sleep--wake cycle in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. J Neurosci Res. 81:891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullin BC, Phillips ML, Siegle GJ, Buysse DJ, Forbes EE, Franzen PL (2013): Sleep deprivation amplifies striatal activation to monetary reward. Psychol Med. 43:2215–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley AE, Berridge KC (2002): The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs. J Neurosci. 22:3306–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demos KE, Sweet LH, Hart CN, McCaffery JM, Williams SE, Mailloux KA, et al. (2017): The Effects of Experimental Manipulation of Sleep Duration on Neural Response to Food Cues. Sleep. 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St-Onge MP, McReynolds A, Trivedi ZB, Roberts AL, Sy M, Hirsch J (2012): Sleep restriction leads to increased activation of brain regions sensitive to food stimuli. Am J Clin Nutr. 95:818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, et al. (2012): Evidence that sleep deprivation downregulates dopamine D2R in ventral striatum in the human brain. J Neurosci. 32:6711–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Hasani R, McCall JG, Shin G, Gomez AM, Schmitz GP, Bernardi JM, et al. (2015): Distinct Subpopulations of Nucleus Accumbens Dynorphin Neurons Drive Aversion and Reward. Neuron. 87:1063–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang H, de Jong JW, Tak Y, Peck J, Bateup HS, Lammel S (2018): Nucleus Accumbens Subnuclei Regulate Motivated Behavior via Direct Inhibition and Disinhibition of VTA Dopamine Subpopulations. Neuron. 97:434–449 e434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossert JM, Poles GC, Wihbey KA, Koya E, Shaham Y (2007): Differential effects of blockade of dopamine D1-family receptors in nucleus accumbens core or shell on reinstatement of heroin seeking induced by contextual and discrete cues. J Neurosci. 27:12655–12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley AE (2004): Ventral striatal control of appetitive motivation: role in ingestive behavior and reward-related learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 27:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuber GD, Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, van Leeuwen WA, Hardjoprajitno JE, Cho S, et al. (2011): Excitatory transmission from the amygdala to nucleus accumbens facilitates reward seeking. Nature. 475:377–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Britt JP, Benaliouad F, McDevitt RA, Stuber GD, Wise RA, Bonci A (2012): Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron. 76:790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lintas A, Chi N, Lauzon NM, Bishop SF, Sun N, Tan H, et al. (2012): Inputs from the basolateral amygdala to the nucleus accumbens shell control opiate reward magnitude via differential dopamine D1 or D2 receptor transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 35:279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambroggi F, Ishikawa A, Fields HL, Nicola SM (2008): Basolateral amygdala neurons facilitate reward-seeking behavior by exciting nucleus accumbens neurons. Neuron. 59:648–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beyeler A, Chang CJ, Silvestre M, Leveque C, Namburi P, Wildes CP, et al. (2018): Organization of Valence-Encoding and Projection-Defined Neurons in the Basolateral Amygdala. Cell Rep. 22:905–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beyeler A, Namburi P, Glober GF, Simonnet C, Calhoon GG, Conyers GF, et al. (2016): Divergent Routing of Positive and Negative Information from the Amygdala during Memory Retrieval. Neuron. 90:348–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goto Y, Grace AA (2008): Limbic and cortical information processing in the nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 31:552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sesack SR, Grace AA (2010): Cortico-Basal Ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35:27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J (2003): The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 83:803–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinonaga Y, Takada M, Mizuno N (1994): Topographic organization of collateral projections from the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus to both the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in the rat. Neuroscience. 58:389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright CI, Beijer AV, Groenewegen HJ (1996): Basal amygdaloid complex afferents to the rat nucleus accumbens are compartmentally organized. J Neurosci. 16:1877–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krueger JM, Obal F (1993): A neuronal group theory of sleep function. Journal of sleep research. 2:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winters BD, Huang YH, Dong Y, Krueger JM (2011): Sleep loss alters synaptic and intrinsic neuronal properties in mouse prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 1420:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen B, Wang Y, Liu X, Liu Z, Dong Y, Huang YH (2015): Sleep Regulates Incubation of Cocaine Craving. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 35:13300–13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cirelli C, Tononi G (2004): Sleep Deprivation: Basic Science, Physiology and Behavior. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colavito V, Fabene PF, Grassi-Zucconi G, Pifferi F, Lamberty Y, Bentivoglio M, et al. (2013): Experimental sleep deprivation as a tool to test memory deficits in rodents. Frontiers in systems neuroscience. 7:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang YH, Lin Y, Mu P, Lee BR, Brown TE, Wayman G, et al. (2009): In vivo cocaine experience generates silent synapses. Neuron. 63:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang YH, Ishikawa M, Lee BR, Nakanishi N, Schluter OM, Dong Y (2011): Searching for presynaptic NMDA receptors in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 31:18453–18463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S (2012): Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 10:486–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kopp C, Longordo F, Nicholson JR, Luthi A (2006): Insufficient sleep reversibly alters bidirectional synaptic plasticity and NMDA receptor function. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 26:12456–12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palchykova S, Winsky-Sommerer R, Meerlo P, Durr R, Tobler I (2006): Sleep deprivation impairs object recognition in mice. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 85:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fenzl T, Romanowski CP, Flachskamm C, Honsberg K, Boll E, Hoehne A, et al. (2007): Fully automated sleep deprivation in mice as a tool in sleep research. Journal of neuroscience methods. 166:229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morairty SR, Dittrich L, Pasumarthi RK, Valladao D, Heiss JE, Gerashchenko D, et al. (2013): A role for cortical nNOS/NK1 neurons in coupling homeostatic sleep drive to EEG slow wave activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:20272–20277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ (2004): Direct interactions between the basolateral amygdala and nucleus accumbens core underlie cocaine-seeking behavior by rats. J Neurosci. 24:7167–7173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kantak KM, Black Y, Valencia E, Green-Jordan K, Eichenbaum HB (2002): Dissociable effects of lidocaine inactivation of the rostral and caudal basolateral amygdala on the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci. 22:1126–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suska A, Lee BR, Huang YH, Dong Y, Schluter OM (2013): Selective presynaptic enhancement of the prefrontal cortex to nucleus accumbens pathway by cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:713–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clements JD, Silver RA (2000): Unveiling synaptic plasticity: a new graphical and analytical approach. Trends in neurosciences. 23:105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saviane C, Silver RA (2007): Estimation of quantal parameters with multiple-probability fluctuation analysis. Methods in molecular biology. 403:303–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silver RA (2003): Estimation of nonuniform quantal parameters with multiple-probability fluctuation analysis: theory, application and limitations. Journal of neuroscience methods. 130:127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O’Shea DJ, et al. (2011): Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. 477:171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME (2017): Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 9:151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finan PH, Quartana PJ, Smith MT (2015): The Effects of Sleep Continuity Disruption on Positive Mood and Sleep Architecture in Healthy Adults. Sleep. 38:1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Logan RW, Hasler BP, Forbes EE, Franzen PL, Torregrossa MM, Huang YH, et al. (2018): Impact of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms on Addiction Vulnerability in Adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 83:987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meerlo P, Havekes R, Steiger A (2015): Chronically restricted or disrupted sleep as a causal factor in the development of depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 25:459–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tempesta D, De Gennaro L, Natale V, Ferrara M (2015): Emotional memory processing is influenced by sleep quality. Sleep Med. 16:862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tkachenko O, Olson EA, Weber M, Preer LA, Gogel H, Killgore WD (2014): Sleep difficulties are associated with increased symptoms of psychopathology. Exp Brain Res. 232:1567–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson KN, Bradley AJ (2013): Sleep disturbance in mental health problems and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Sci Sleep. 5:61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krystal AD (2012): Psychiatric disorders and sleep. Neurol Clin. 30:1389–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Chen Z, Fan G, Li A, Yuan J, Xu T (2018): Cell-Type-Specific Afferent Innervation of the Nucleus Accumbens Core and Shell. Front Neuroanat. 12:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scudder SL, Baimel C, Macdonald EE, Carter AG (2018): Hippocampal-Evoked Feedforward Inhibition in the Nucleus Accumbens. J Neurosci. 38:9091–9104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu J, Yan Y, Li KL, Wang Y, Huang YH, Urban NN, et al. (2017): Nucleus accumbens feedforward inhibition circuit promotes cocaine self-administration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114:E8750–E8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lobo MK, Covington HE 3rd, Chaudhury D, Friedman AK, Sun H, Damez-Werno D, et al. (2010): Cell type-specific loss of BDNF signaling mimics optogenetic control of cocaine reward. Science. 330:385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lobo MK, Nestler EJ (2011): The striatal balancing act in drug addiction: distinct roles of direct and indirect pathway medium spiny neurons. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yawata S, Yamaguchi T, Danjo T, Hikida T, Nakanishi S (2012): Pathway-specific control of reward learning and its flexibility via selective dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109:12764–12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Natsubori A, Tsutsui-Kimura I, Nishida H, Bouchekioua Y, Sekiya H, Uchigashima M, et al. (2017): Ventrolateral Striatal Medium Spiny Neurons Positively Regulate Food-Incentive, Goal-Directed Behavior Independently of D1 and D2 Selectivity. J Neurosci. 37:2723–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koo JW, Lobo MK, Chaudhury D, Labonte B, Friedman A, Heller E, et al. (2014): Loss of BDNF signaling in D1R-expressing NAc neurons enhances morphine reward by reducing GABA inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 39:2646–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cole SL, Robinson MJF, Berridge KC (2018): Optogenetic self-stimulation in the nucleus accumbens: D1 reward versus D2 ambivalence. PLoS One. 13:e0207694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mallet N, Le Moine C, Charpier S, Gonon F (2005): Feedforward inhibition of projection neurons by fast-spiking GABA interneurons in the rat striatum in vivo. J Neurosci. 25:3857–3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wright WJ, Schluter OM, Dong Y (2017): A Feedforward Inhibitory Circuit Mediated by CB1-Expressing Fast-Spiking Interneurons in the Nucleus Accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 42:1146–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koos T, Tepper JM (1999): Inhibitory control of neostriatal projection neurons by GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2:467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen X, Liu Z, Ma C, Ma L, Liu X (2019): Parvalbumin Interneurons Determine Emotional Valence Through Modulating Accumbal Output Pathways. Front Behav Neurosci. 13:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qi J, Zhang S, Wang HL, Barker DJ, Miranda-Barrientos J, Morales M (2016): VTA glutamatergic inputs to nucleus accumbens drive aversion by acting on GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 19:725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brundege JM, Williams JT (2002): Differential modulation of nucleus accumbens synapses. Journal of neurophysiology. 88:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brundege JM, Williams JT (2002): Increase in adenosine sensitivity in the nucleus accumbens following chronic morphine treatment. Journal of neurophysiology. 87:1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hines DJ, Schmitt LI, Hines RM, Moss SJ, Haydon PG (2013): Antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation require astrocyte-dependent adenosine mediated signaling. Translational psychiatry. 3:e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beurrier C, Malenka RC (2002): Enhanced inhibition of synaptic transmission by dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during behavioral sensitization to cocaine. J Neurosci. 22:5817–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harvey J, Lacey MG (1996): Endogenous and exogenous dopamine depress EPSCs in rat nucleus accumbens in vitro via D1 receptors activation. The Journal of physiology. 492 (Pt 1):143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harvey J, Lacey MG (1997): A postsynaptic interaction between dopamine D1 and NMDA receptors promotes presynaptic inhibition in the rat nucleus accumbens via adenosine release. J Neurosci. 17:5271–5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA Jr. (2006): The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biological psychiatry. 59:1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nicola SM, Malenka RC (1998): Modulation of synaptic transmission by dopamine and norepinephrine in ventral but not dorsal striatum. Journal of neurophysiology. 79:1768–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pennartz CM, Dolleman-Van der Weel MJ, Kitai ST, Lopes da Silva FH (1992): Presynaptic dopamine D1 receptors attenuate excitatory and inhibitory limbic inputs to the shell region of the rat nucleus accumbens studied in vitro. Journal of neurophysiology. 67:1325–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spanagel R, Weiss F (1999): The dopamine hypothesis of reward: past and current status. Trends Neurosci. 22:521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tritsch NX, Sabatini BL (2012): Dopaminergic modulation of synaptic transmission in cortex and striatum. Neuron. 76:33–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang W, Dever D, Lowe J, Storey GP, Bhansali A, Eck EK, et al. (2012): Regulation of prefrontal excitatory neurotransmission by dopamine in the nucleus accumbens core. The Journal of physiology. 590:3743–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huston JP, Haas HL, Boix F, Pfister M, Decking U, Schrader J, et al. (1996): Extracellular adenosine levels in neostriatum and hippocampus during rest and activity periods of rats. Neuroscience. 73:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, McCarley RW (2000): Brain site-specificity of extracellular adenosine concentration changes during sleep deprivation and spontaneous sleep: an in vivo microdialysis study. Neuroscience. 99:507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jentsch JD, Taylor JR (1999): Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 146:373–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Feil J, Sheppard D, Fitzgerald PB, Yucel M, Lubman DI, Bradshaw JL (2010): Addiction, compulsive drug seeking, and the role of frontostriatal mechanisms in regulating inhibitory control. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 35:248–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ferenczi EA, Zalocusky KA, Liston C, Grosenick L, Warden MR, Amatya D, et al. (2016): Prefrontal cortical regulation of brainwide circuit dynamics and reward-related behavior. Science. 351:aac9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peters J, Kalivas PW, Quirk GJ (2009): Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 16:279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barker JM, Taylor JR, Chandler LJ (2014): A unifying model of the role of the infralimbic cortex in extinction and habits. Learn Mem. 21:441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gable PA, Harmon-Jones E (2010): The effect of low versus high approach-motivated positive affect on memory for peripherally versus centrally presented information. Emotion. 10:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gable PA, Harmon-Jones E (2008): Approach-motivated positive affect reduces breadth of attention. Psychol Sci. 19:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fredrickson BL, Branigan C (2005): Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn Emot. 19:313–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Harmon-Jones E, Gable PA (2009): Neural activity underlying the effect of approach-motivated positive affect on narrowed attention. Psychol Sci. 20:406–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knutson B, Peterson R (2005): Neurally reconstructing expected utility. Games and Economic Behavior. 52:11. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gable P, Harmon-Jones E (2008): Relative left frontal activation to appetitive stimuli: considering the role of individual differences. Psychophysiology. 45:275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sorge RE, Pierre VJ, Clarke PB (2009): Facilitation of intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats by a motivationally neutral sensory stimulus. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 207:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ (2003): Mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.