Abstract

Streptomyces are efficient producers of various bioactive compounds, which are mostly synthesized by their secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (smBGCs). The smBGCs are tightly controlled by complex regulatory systems at transcriptional and translational levels to effectively utilize precursors that are supplied by primary metabolism. Thus, dynamic changes in gene expression in response to cellular status at both the transcriptional and translational levels should be elucidated to directly reflect protein levels, rapid downstream responses, and cellular energy costs. In this study, RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling were performed for five industrially important Streptomyces species at different growth phases, for the deep sequencing of total mRNA, and only those mRNA fragments that are protected by translating ribosomes, respectively. Herein, 12.0 to 763.8 million raw reads were sufficiently obtained with high quality of more than 80% for the Phred score Q30 and high reproducibility. These data provide a comprehensive understanding of the transcriptional and translational landscape across the Streptomyces species and contribute to facilitating the rational engineering of secondary metabolite production.

Subject terms: Prokaryote, Next-generation sequencing, RNA sequencing

| Measurement(s) | transcriptome • translation • translatome |

| Technology Type(s) | RNA sequencing • Ribo-Seq |

| Factor Type(s) | Growth phases |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Streptomyces avermitilis • Streptomyces clavuligerus • Streptomyces lividans • Streptomyces venezuelae • Streptomyces tsukubensis |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12045603

Background & Summary

Streptomyces, which comprise the largest genus of Actinobacteria, are huge natural reservoir of secondary metabolites, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and other medicinal compounds1–6. Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing have led to the development of the genome mining approach, which implicates that the genome of each Streptomyces species has more than 30 secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (smBGCs) with potential to produce various unexplored secondary metabolites2. These secondary metabolites are synthesized by a series of enzymatic reactions, which depend on the supply of precursor molecules from primary metabolism, such as acetyl-coenzyme A and amino acids7. After active growth terminates, an overall metabolic transition occurs, which leads to the activation of secondary metabolite production8,9; this metabolic transition from primary to secondary metabolism is governed by multi-layered regulatory mechanisms at transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels10,11. Thus, understanding the complex regulatory systems of the metabolic transition is important to enhance secondary metabolite production. The overall metabolic transition encompasses diverse genome-wide gene expression changes, which are regulated by signaling cascades from the pleiotropic regulators to pathway-specific regulators8,10,12,13. To understand the underlying molecular mechanisms of metabolic transitions, transcriptional changes that occur between growth phases have been studied13–15. For example, the time-series transcriptome analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor demonstrated that coherent genes that are involved in specific metabolism and their regulatory genes exhibit similar expression patterns during metabolic transitions; this suggests that primary metabolism-related genes are functionally connected to the smBGC genes through regulatory gene expression. Based on this suggestion, putative regulatory genes and their interconnected networks could be identified by screening genes that have similar expression patterns13.

Bacteria can fine-tune gene expression both at the transcriptional and translational levels16,17. For example, Escherichia coli proteome analysis revealed that only approximately half of protein abundance is determined by transcriptional regulation, which indicates the existence of various post-transcriptional regulation18. In this regard, deciphering translational dynamics is important to understanding post-transcriptional regulations that are closely related to cellular protein levels19. Recently, ribosome profiling has been used to measure translational levels by deep sequencing of the ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (RPFs) at the position of the translating ribosome20. Several ribosome profiling studies in Streptomyces have been reported by our research group for S. coelicolor, S. clavuligerus, and S. lividans, which revealed translational buffering of secondary metabolism-related genes at a later growth phase and that translational abundance is more consistently maintained than transcript abundance11,21,22. Translational regulations are advantageous for the tight control of secondary metabolite biosynthesis, as translation requires the highest energy costs among all cellular reactions19. Moreover, the expression of smBGC-associated genes can be more rapidly regulated at the translational level than at the transcriptional level in response to dynamic environmental changes23. Given the dynamic relationship between transcription and translation, as exhibited by translational buffering11, integrative analysis at both levels should unravel complex regulations in Streptomyces. However, transcriptomic and translatomic data have covered only a small portion of approximately 350 reported Streptomyces genomes, which have not been systematically validated at the multi-species level.

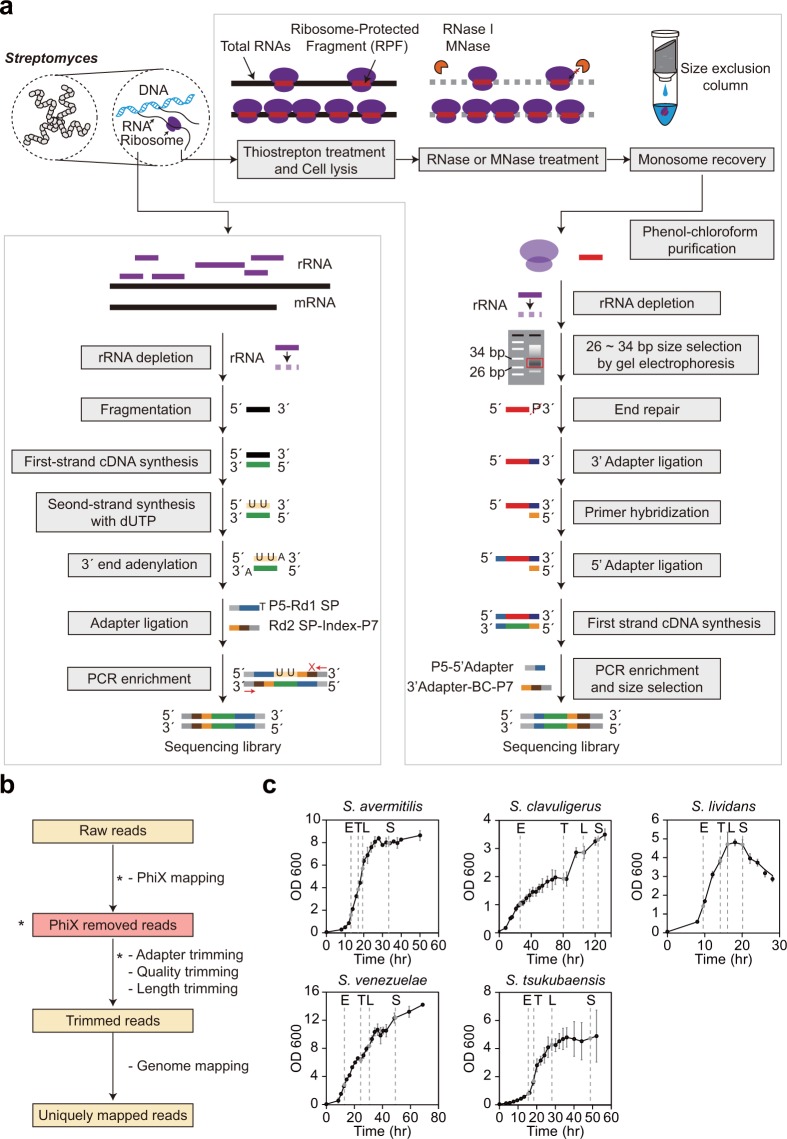

In this study, we provide RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data of five Streptomyces species at four different growth phases, followed by validation of the read quality. The species were S. avermitilis MA-4680, S. clavuligerus ATCC27064, S. lividans TK24, S. venezuelae ATCC15439, and S. tsukubaensis NRRL 18488, which are industrial strains that produce antifungal avermectin, β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid, and immunosuppressant FK506, respectively24–26. S. lividans and S. venezuelae were characterized by their fast growth and ease of genetic manipulation, and have been employed as heterologous expression hosts27–30. An overview of the preparation of transcriptomic and translatomic data is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 12 to 83.5 million raw reads for RNA-Seq and 113 to 763.8 million raw reads for ribosome profiling were obtained. Although the RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data of two species (S. clavuligerus21 and S. lividans22) among the five species were already reported in previous studies by our research group, this study provided a uniformly processed and mapped dataset of all five species. This facilitates the efficiency of the comparative transcriptome and translatome analysis at multi-time points between multi-species. Further, understanding the transcriptional and translational regulatory mechanisms and developing regulatory synthetic parts, such as promoters, ribosome-binding sequences, 5′ untranslated regions, and terminators4 from the dataset allows rational genome engineering for efficient secondary metabolite production by Streptomyces11.

Fig. 1.

Overall flow of RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data construction of five Streptomyces species. (a) The sequencing library construction protocol for RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling. P5 and P7 were the PCR primers, Rd1 SP and Rd2 SP were the sequencing primers, and BC was the barcode sequence. (b) An overview of processing and mapping of the sequencing reads. The criteria or parameters are shown. The steps indicated with asterisk (*) are performed only for the ribosome profiling data. (c) The growth profile of five Streptomyces species in R5− medium. Sampling time points are represented by a grey dot, which are the early-exponential (E), transition (T), late-exponential (L), and stationary (S) points.

Methods

Strains and cell growth

Streptomyces strains were inoculated from their 20% glycerol stock of spores into 50 mL of R5− liquid medium with 8 g of glass beads (3 ± 0.3 mm diameter) in a 250 mL baffled flask, grown at 30 °C, and pre-cultured at 250 rpm. The R5− liquid medium consists of 103 g L−1 sucrose, 0.25 g L−1 K2SO4, 10.12 g L−1 MgCl2∙6H2O, 10 g L−1 glucose, 0.1 g L−1 casamino acids, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, 5.73 g L−1 TES (pH 7.2), 0.08 mg L−1 ZnCl2, 0.4 mg L−1 FeCl3∙6H2O, 0.02 mg L−1 CuCl2∙2H2O, 0.02 mg L−1 MnCl2∙4H2O, 0.02 mg L−1 Na2B4O7∙10H2O, 0.02 mg L−1 (NH4)6Mo7O24∙4H2O, and 0.28 g L−1 NaOH. The grown mycelium was inoculated to fresh R5− medium with an initial optical density of 0.05 at 600 nm for the main culture as biological duplicates and grown under the previously mentioned conditions. The cells were sampled at four different time points based on the growth profile of each strain, as follows: early-exponential (E), transition (T), late-exponential (L), and stationary (S) phases. The E, T, L, and S time points were 13, 17, 19.5, and 33.5 h for S. avermitilis, 26, 80, 105.5, and 125 h for S. clavuligerus, 9.5, 14, 16, and 20 h for S. lividans, 12.5, 24.5, 30.5, and 48.5 h for S. venezuelae, and 15, 18.5, 28, and 48 h for S. tsukubaensis after inoculation, respectively (Fig. 1c). At the sampling time points for the ribosome profiling samples, thiostrepton (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 20 μM to compartment the translating ribosomes on the mRNA, which is a highly sensitive drug for Streptomyces compared to chloramphenicol or other drugs31,32. The cultures were then incubated for 5 min at 30 °C, and subsequently harvested for the construction of ribosome profiling libraries.

RNA-Seq library preparation and high-throughput sequencing

The overview of the library construction of RNA-Seq is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The harvested cells were washed with polysome buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 140 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2), and then resuspended with 500 μL lysis buffer (0.3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.2; 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 1% Triton X-100). The resuspended cells were frozen with liquid nitrogen and grounded using a mortar and pestle. The ground mycelium was thawed and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C. Following the preparation of lysates from four growth phases as biological duplicates, the lysates were mixed with a solution of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v), and the mixtures were separated by centrifugation. DNA in the extracted RNA samples were removed by treatment with 2 μL DNase I (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), 5 μL 10 × DNase I buffer, and 1 μL SUPERase-In RNase Inhibitor (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lastly, the DNase I-treated RNA samples were purified using phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) and ethanol precipitation. To eliminate rRNAs in the recovered RNA samples, the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit for Bacteria (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of rRNA-depleted RNA samples was checked using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The suitable RNA samples were then used to construct RNA sequencing libraries using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The size distributions of the final libraries were checked using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The constructed libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq. 2500 platform using either a 100-bp (S. lividans, S. avermitilis, S. clavuligerus, and S. venezuelae) or 50-bp (S. tsukubaensis) single-end read recipe (Fig. 1a).

Data processing of RNA-Seq reads

Raw FASTQ files were processed using the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Raw reads were trimmed by their overall quality (score: 0.05; maximum ambiguous nucleotides: (2) and length (minimum length: 15 nucleotides). The filtered reads were mapped to each reference genome sequence with the default parameters (mismatch cost: 2; insertion cost: 2; deletion cost: 3; length fraction: 0.9; similarity fraction: 0.9; and ignore non-specific matches). The accession number of each reference genome is as follows: S. avermitilis MA-4680 (NC_010572), S. clavuligerus ATCC27064 (chromosome NZ_CP027858, plasmid NZ_CP027859), S. lividans TK24 (NZ_CP009124), S. venezuelae ATCC15439 (CP013129), and S. tsukubaensis NRRL18488 (chromosome CP020700, plasmid CP020701, and CP020702). The statistics pertaining to quality trimming and reference mapping are summarized in Table 1. The number of uniquely mapped reads to each gene were counted using the RNA-Seq analysis tool in the CLC Genomics Workbench and the read counts were normalized using the DESeq. 2 package in R33.

Table 1.

Overall statistics of RNA-Seq data.

| Species | Growth phase | Number of raw reads | Average length (bp) | Number of trimmed_read | Percentage trimmed | Trimmed reads length (bp) | Number of randomly mapped reads | Number of uniquely mapped reads | Percentage of uniquely mapped reads (%) | Raw read FASTQ accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. avermitilis MA-4680 | E1 | 15,222,700 | 101 | 15,222,324 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 14,743,001 | 14,475,094 | 95.09 | SRP158023 |

| E2 | 15,540,304 | 101 | 15,539,540 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 14,842,965 | 14,232,752 | 91.59 | ||

| T1 | 18,962,695 | 101 | 18,961,958 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 17,584,931 | 16,820,053 | 88.70 | ||

| T2 | 18,054,983 | 101 | 18,054,302 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 16,337,750 | 14,948,455 | 82.80 | ||

| L1 | 13,904,005 | 101 | 13,903,462 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 12,858,182 | 12,238,050 | 88.02 | ||

| L2 | 16,814,305 | 101 | 16,813,651 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 15,778,544 | 15,212,127 | 90.47 | ||

| S1 | 16,662,552 | 101 | 16,661,924 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 15,627,234 | 14,761,494 | 88.59 | ||

| S2 | 16,278,766 | 101 | 16,278,123 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 14,643,706 | 12,519,514 | 76.91 | ||

| S. clavuligerus ATCC 27064 | E1 | 14,798,628 | 101 | 14,798,315 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 11,098,664 | 9,036,995 | 61.07 | SRP188290 |

| E2 | 14,979,238 | 101 | 14,978,853 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 10,822,676 | 8,622,479 | 57.56 | ||

| T1 | 15,701,669 | 101 | 15,701,289 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 10,501,955 | 9,056,077 | 57.68 | ||

| T2 | 12,420,952 | 101 | 12,420,654 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 10,776,124 | 10,096,097 | 81.28 | ||

| L1 | 13,207,846 | 101 | 13,207,520 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 7,770,986 | 7,283,393 | 55.15 | ||

| L2 | 13,782,302 | 101 | 13,782,042 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 7,706,785 | 7,193,337 | 52.19 | ||

| S1 | 13,526,270 | 101 | 13,525,948 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 12,683,457 | 12,292,000 | 90.88 | ||

| S2 | 13,272,332 | 101 | 13,272,058 | 100.00 | 100.6 | 12,663,763 | 11,921,210 | 89.82 | ||

| S. lividans TK24 | E1 | 15,062,705 | 101 | 15,062,394 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 13,098,717 | 12,182,999 | 80.88 | PRJEB31507 |

| E2 | 15,941,901 | 101 | 15,941,640 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 14,010,897 | 12,726,791 | 79.83 | ||

| T1 | 14,403,255 | 101 | 14,402,994 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 12,594,960 | 11,858,708 | 82.34 | ||

| T2 | 15,701,759 | 101 | 15,701,526 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 14,333,364 | 13,320,933 | 84.84 | ||

| L1 | 16,081,294 | 101 | 16,080,979 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 14,679,573 | 14,003,911 | 87.08 | ||

| L2 | 15,402,577 | 101 | 15,402,313 | 100.00 | 100.8 | 13,896,464 | 12,784,443 | 83.00 | ||

| S1 | 15,650,348 | 101 | 15,650,033 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 14,016,141 | 12,866,712 | 82.22 | ||

| S2 | 17,244,360 | 101 | 17,243,710 | 100.00 | 100.9 | 13,310,075 | 10,371,378 | 60.15 | ||

| S. venezuelae ATCC15439 | E1 | 13,343,482 | 101 | 13,339,752 | 99.97 | 100.9 | 11,002,160 | 9,468,993 | 70.98 | PRJEB34219 |

| E2 | 13,150,521 | 101 | 13,147,020 | 99.97 | 100.9 | 10,562,003 | 9,986,725 | 75.96 | ||

| T1 | 14,479,417 | 101 | 14,474,269 | 99.96 | 100.9 | 13,219,134 | 12,480,953 | 86.23 | ||

| T2 | 12,310,427 | 101 | 12,307,770 | 99.98 | 100.9 | 10,406,022 | 9,456,882 | 76.84 | ||

| L1 | 12,192,708 | 101 | 12,173,069 | 99.84 | 100.9 | 10,371,418 | 9,415,019 | 77.34 | ||

| L2 | 12,728,235 | 101 | 12,723,109 | 99.96 | 100.9 | 10,435,448 | 8,569,124 | 67.35 | ||

| S1 | 13,022,122 | 101 | 13,019,964 | 99.98 | 100.9 | 10,770,484 | 9,268,463 | 71.19 | ||

| S2 | 11,969,031 | 101 | 11,957,872 | 99.91 | 100.9 | 9,138,846 | 8,090,654 | 67.66 | ||

| S. tsukubaensis NRRL18488 | E1 | 41,652,947 | 51 | 41,627,595 | 99.94 | 50.9 | 41,292,669 | 31,773,092 | 76.33 | SRP103795 |

| E2 | 35,401,018 | 51 | 35,382,993 | 99.95 | 50.8 | 34,839,050 | 34,058,311 | 96.26 | ||

| T1 | 53,758,514 | 51 | 53,721,965 | 99.93 | 50.8 | 52,441,945 | 51,123,244 | 95.16 | ||

| T2 | 25,432,836 | 51 | 25,421,462 | 99.96 | 50.8 | 24,909,553 | 24,095,211 | 94.78 | ||

| L1 | 83,469,019 | 51 | 83,456,281 | 99.98 | 50.6 | 82,904,135 | 76,980,981 | 92.24 | ||

| L2 | 39,371,004 | 51 | 39,339,183 | 99.92 | 50.8 | 38,739,771 | 36,079,744 | 91.71 | ||

| S1 | 78,596,694 | 51 | 78,587,491 | 99.99 | 50.6 | 77,714,238 | 61,851,605 | 78.70 | ||

| S2 | 51,475,167 | 51 | 51,441,666 | 99.93 | 50.9 | 50,553,226 | 44,055,753 | 85.64 |

Ribosome profiling library preparation and high-throughput sequencing

An overview on the library construction of ribosome profiling is illustrated in Fig. 1a 21. The mycelium that was treated by thiostrepton was collected by centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min at 3,000 × g, and the cell pellet was washed with 2 mL of polysome buffer that was composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 with 20 μM thiostrepton. The washed pellet was re-suspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer composed of 950 μL of polysome buffer and 50 μL of 20% Triton X-100 with 20 μM thiostrepton. The resuspended cells were dripped into a mortar filled with liquid nitrogen and then grounded with a pestle. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 5 min at 3,000 × g. The supernatant was further clarified and collected by centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 × g. To digest RNA in the lysate (containing 50 μg RNA), the S. avermitilis and S. tsukubaensis samples were treated with 750 U of RNase I (Invitrogen, Waltharn, MA, USA) at 37 °C for 45 min, and the remaining strains were treated with 400 U of Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) (NEB), 20 μl of 10× MNase buffer, and 2 μl of 100× Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) (NEB) at 37 °C for 2 h. The samples were then loaded onto Illustra MicroSpin S-400 HR Columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA, USA) that were previously washed three times with 500 μL of washing buffer, which was composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 25 mM EGTA, and 1% Triton X-100. The column was centrifuged at 4 °C for 2 min at 400 × g, and the flow-through was further purified by a phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation. rRNA was depleted with the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Epicentre) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ribosome-protected RNA fragments (RPF) of between 26 and 34 bp were separated by electrophoresis for 65 min at 200 V using 15% polyacrylamide TBE-urea gel (Invitrogen), and eluted in 400 μL of RNA gel extraction buffer, which was composed of 300 mM sodium acetate pH 5.5, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.25% (w/v) SDS. The samples were frozen for 30 min at −80 °C and then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The eluted RNAs were isolated by ethanol precipitation and purified once again with the RNeasy MinElute Column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using the manufacturer’s protocol. The enriched RPFs were then denatured for 90 s at 80 °C and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 5 mL of 10× T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) buffer (NEB), 20 U of SUPERase-In RNase Inhibitor, and 10 U of T4 PNK (NEB) to dephosphorylate the 3′ end. The dephosphorylated RNAs were purified using the RNeasy MinElute Column (Qiagen). The sequencing library was constructed from the end-repaired RPFs using the NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (NEB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final library of approximately 150–160 bp was size-selected by gel electrophoresis for 90 min at 100 V using a 2% agarose gel that was dyed with SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The concentration of the final library was measured using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and the Qubit dsDNA HS Kit. The size distribution was assessed using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation System (Agilent). The constructed library was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq. 2500 platform using the 50-bp single-end read recipe (Fig. 1b).

Data processing of ribosome profiling reads

The libraries of seven samples of S. avermitilis—except for the E1 sample—and six samples of S. venezuelae—except for the T2 and S2 samples—were prepared and sequenced twice to increase the output and merged for further data processing (Table 2). The sequencing results were de-multiplexed and processed by CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC Bio). A total of 113,065,267 to 763,831,282 raw reads were generated for each replicate and were exported in the FASTQ format for the data upload. The reads were then mapped to the PhiX control sequences (NCBI Genbank accession number: NC_001422) to eliminate the PhiX control reads with the following parameters: mismatch cost: 2; insertion cost: 3; deletion cost: 3; length fraction: 0.9; similarity fraction: 0.9; and non-specific matches were randomly mapped. A total of 112,376,633 to 661,109,040 reads were unmapped. As these reads were sequenced from the 5′ end of the enriched RPF to 50 bp downstream, which is longer than the size-selected RPF (26 to 34 bp), the 5′ end sequences of the 3′ adapter sequence of the NEBNext Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (NEB) were also included. To remove the adapter sequences from the reads prior to mapping, the sequences were trimmed by the following parameters: action: remove adapter; strand: minus; mismatch cost: 2; gap cost: 3; internal match minimum score: 3; and end match minimum score: 3. Ultimately, the removed adapter sequence was 5′−ATACGAGATNNNNNNCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTT−3′, in which the NNNNNN sequences were CACTGT, ATTGGC, TACAAG, and TTTCA for index 5, 6, 12, and 19, respectively. The reads were additionally trimmed based on their overall quality (score: 0.05, maximum ambiguous nucleotides: 2) and length (>15 bp). The trimming steps yielded 90.68 to 98.47% of the PhiX control unmapped reads. To confirm the data quality and reproducibility of the reads to analyze the translational abundance of the genes, the reads were mapped to their genome sequence. A total of 84,947,464 to 590,644,871 reads with an average read length of 25.8 to 33.7 bp were mapped with random mapping of non-specific matches, while 1,833,155 to 103,819,037 reads with an average read length of 25.8 to 33.1 bp were mapped with ignored mapping of non-specific matches (mismatch cost: 2; insertion cost: 3; deletion cost: 3; length fraction: 0.9; similarity cost: 0.9). The overall statistics of the data processing are summarized in Table 2. The mapped information was exported in a BAM file format, and the number of mapped reads at each genomic position was counted as the read count. Normalized read value and principal component analysis (PCA) plots were generated using the DESeq. 2 package in R34.

Table 2.

Overall statistics of ribosome profiling data.

| Species | Growth phase | Number of raw reads | Number of PhiX_unmapped read | Number of trimmed_read | Trimmed reads length (bp) | Number of randomly mapped reads | Number of uniquely mapped reads | Uniquely mapped read length (bp) | Number of mapped reads within CDS | Raw read FASTQ accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. avermitilis MA-4680 | E1 | 269,943,816 | 213,953,123 | 209,920,058 | 29.3 | 203,095,358 | 12,355,916 | 29.9 | 7,361,468 | SRP158023 |

| E2 | 219,153,779 | 155,106,616 | 150,989,307 | 32.2 | 115,492,305 | 2,022,429 | 32.7 | 1,638,497 | ||

| T1 | 230,159,662 | 148,885,319 | 144,318,010 | 32.7 | 119,536,793 | 3,541,737 | 32.8 | 2,455,564 | ||

| T2 | 266,436,355 | 175,849,102 | 170,463,269 | 31.5 | 139,053,054 | 2,304,886 | 32 | 1,665,882 | ||

| L1 | 315,653,269 | 223,796,896 | 217,299,279 | 32.5 | 171,944,766 | 7,386,273 | 31.7 | 4,018,623 | ||

| L2 | 308,070,582 | 228,756,230 | 221,698,272 | 31.5 | 169,555,584 | 2,929,594 | 31.8 | 2,099,075 | ||

| S1 | 353,167,764 | 253,272,121 | 245,481,924 | 32.7 | 184,855,688 | 13,061,116 | 29.6 | 3,594,618 | ||

| S2 | 314,771,387 | 223,201,435 | 216,515,335 | 32.3 | 169,100,733 | 7,789,273 | 29.6 | 2,170,481 | ||

| S. clavuligerus ATCC27064 | E1 | 295,724,334 | 202,630,787 | 196,272,522 | 30.1 | 186,099,317 | 80,030,583 | 29.6 | 8,017,879 | SRP188290 |

| E2 | 307,178,979 | 220,741,829 | 200,168,124 | 25.9 | 187,152,134 | 61,281,649 | 25.8 | 10,793,485 | ||

| T1 | 253,508,213 | 169,638,278 | 162,668,883 | 29.5 | 153,361,820 | 89,299,628 | 29.2 | 6,590,232 | ||

| T2 | 278,275,008 | 192,923,207 | 186,424,116 | 29.5 | 175,804,007 | 87,504,701 | 29.1 | 6,622,288 | ||

| L1 | 270,412,414 | 177,901,515 | 172,769,472 | 29.5 | 157,803,554 | 87,274,405 | 29.3 | 5,179,486 | ||

| L2 | 247,353,047 | 173,740,843 | 167,591,084 | 29.3 | 153,762,950 | 80,385,683 | 29.1 | 4,290,733 | ||

| S1 | 238,332,934 | 174,931,608 | 168,131,662 | 29.2 | 151,884,988 | 85,485,768 | 29 | 6,272,720 | ||

| S2 | 265,467,800 | 177,945,831 | 170,844,372 | 29.3 | 158,910,658 | 87,634,498 | 29.1 | 8,614,984 | ||

| S. lividans TK24 | E1 | 309,069,871 | 221,703,188 | 211,211,182 | 29.6 | 199,318,423 | 97,211,458 | 29.6 | 19,459,202 | PRJEB31507 |

| E2 | 296,200,898 | 195,130,032 | 185,499,278 | 30.7 | 173,681,372 | 81,149,257 | 30.4 | 13,680,737 | ||

| T1 | 275,143,588 | 188,420,163 | 183,178,560 | 29.6 | 173,135,378 | 24,771,546 | 29.1 | 7,284,890 | ||

| T2 | 212,032,571 | 140,458,753 | 136,973,078 | 31.8 | 125,039,755 | 21,109,391 | 30.4 | 7,941,585 | ||

| L1 | 263,274,610 | 144,638,209 | 142,426,169 | 31.8 | 113,452,166 | 9,735,525 | 31.2 | 6,343,211 | ||

| L2 | 224,511,134 | 154,437,906 | 150,790,276 | 31.9 | 137,882,471 | 19,449,401 | 31 | 13,544,509 | ||

| S1 | 181,850,628 | 120,826,462 | 116,547,304 | 32.2 | 96,190,179 | 10,046,165 | 30.9 | 7,412,208 | ||

| S2 | 297,413,784 | 249,272,969 | 244,109,074 | 32.7 | 233,266,663 | 13,457,825 | 33.1 | 8,447,573 | ||

| S. venezuelae ATCC15439 | E1 | 631,858,582 | 536,439,531 | 522,569,147 | 33.2 | 489,456,639 | 69,000,627 | 31.5 | 5,079,524 | SRX6932518 ~ SRX6932525 |

| E2 | 535,926,210 | 429,105,453 | 415,708,343 | 33.8 | 390,659,798 | 40,255,232 | 31.8 | 3,642,920 | ||

| T1 | 394,870,178 | 340,483,910 | 329,759,627 | 32.4 | 300,485,612 | 40,691,934 | 30.9 | 2,723,458 | ||

| T2 | 166,241,490 | 161,092,945 | 157,601,248 | 31.8 | 138,943,001 | 35,483,940 | 30.6 | 2,162,631 | ||

| L1 | 763,831,282 | 661,109,040 | 641,879,092 | 32.2 | 590,644,871 | 71,846,636 | 30.7 | 5,611,836 | ||

| L2 | 646,261,568 | 533,891,315 | 520,671,902 | 32 | 482,564,893 | 67,853,120 | 30.9 | 4,261,890 | ||

| S1 | 451,939,879 | 378,474,029 | 369,204,078 | 31.6 | 297,503,315 | 52,715,125 | 30.6 | 3,509,283 | ||

| S2 | 168,577,692 | 164,169,059 | 158,023,893 | 31.1 | 147,637,916 | 34,179,596 | 30.4 | 1,764,845 | ||

| S. tsukubaensis NRRL 18488 | E1 | 125,024,824 | 123,919,014 | 121,549,761 | 30.1 | 102,297,821 | 2,307,786 | 30.7 | 1,572,115 | SRP103795 |

| E2 | 124,528,713 | 123,522,173 | 120,322,929 | 30 | 97,672,956 | 1,833,155 | 31.4 | 1,313,616 | ||

| T1 | 132,160,059 | 131,056,038 | 126,769,305 | 31.1 | 99,903,619 | 8,779,981 | 29.7 | 2,895,583 | ||

| T2 | 113,065,267 | 112,376,633 | 109,608,582 | 30.6 | 84,947,464 | 2,814,409 | 29.5 | 1,142,882 | ||

| L1 | 162,942,510 | 161,871,882 | 157,083,409 | 30.7 | 137,909,625 | 52,297,448 | 29.3 | 9,275,687 | ||

| L2 | 166,664,595 | 165,825,698 | 161,666,872 | 30.9 | 140,291,702 | 56,575,985 | 29.1 | 7,533,975 | ||

| S1 | 146,036,258 | 144,790,983 | 138,367,948 | 29.7 | 115,443,226 | 6,902,386 | 29.4 | 1,325,229 | ||

| S2 | 199,958,654 | 199,442,987 | 192,788,031 | 30 | 171,209,443 | 103,819,037 | 28.9 | 4,429,568 |

Data Records

Raw read FASTQ files, trimmed read FASTQ files, mapped read BAM files, and the gene expression text files of all samples were uploaded to the public databases (Tables 1 and 2). Raw read FASTQ files of RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling of three species (S. avermitilis, S. clavuligerus, S. tsukubaensis) were deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA)35–37. Raw read FASTQ files of RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling of S. lividans were deposited at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)38. Raw read FASTQ files of RNA-Seq of S. venezuelae were deposited at the ENA39. Raw read FASTQ files of ribosome profiling of S. venezuelae were deposited at the NCBI SRA40–47. Trimmed read FASTQ files and mapped read BAM files of the raw read FASTQ files in the NCBI SRA (RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data of S. avermitilis, S. clavuligerus, S. tsukubaensis, and ribosome profiling data of S. venezuelae) were deposited at the ENA with a new accession48. Trimmed read FASTQ files and mapped read BAM files of the raw read FASTQ files in the ENA (RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data of S. lividans, and RNA-Seq data of S. venezuelae) were also deposited at the ENA with the same accession as each corresponding raw read FASTQ file38,39. The gene expression profile as raw read counts of RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling data of S. avermitilis49, S. clavuligerus50, S. tsukubaensis51, and ribosome profiling data of S. venezuelae52 are available in a text file format in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Also, the gene expression profiles of all datasets (RNA-Seq and ribosome profiling of the five species), including raw read counts, DESeq. 2 normalized values, fold change values between growth phases, and p-values for the fold changes, are available in a text file format in the Figshare53. The raw read FASTQ data of S. clavuligerus in NCBI SRA36 was published in the previous study21. Also, the raw read FASTQ data of S. lividans in ENA38 was published in the previous study22. Note that the ribosome profiling data of Streptomyces griseus was uploaded under the same accession with those of S. venezuelae, but they are not described in this study.

Technical Validation

RNA-Seq read quality validation

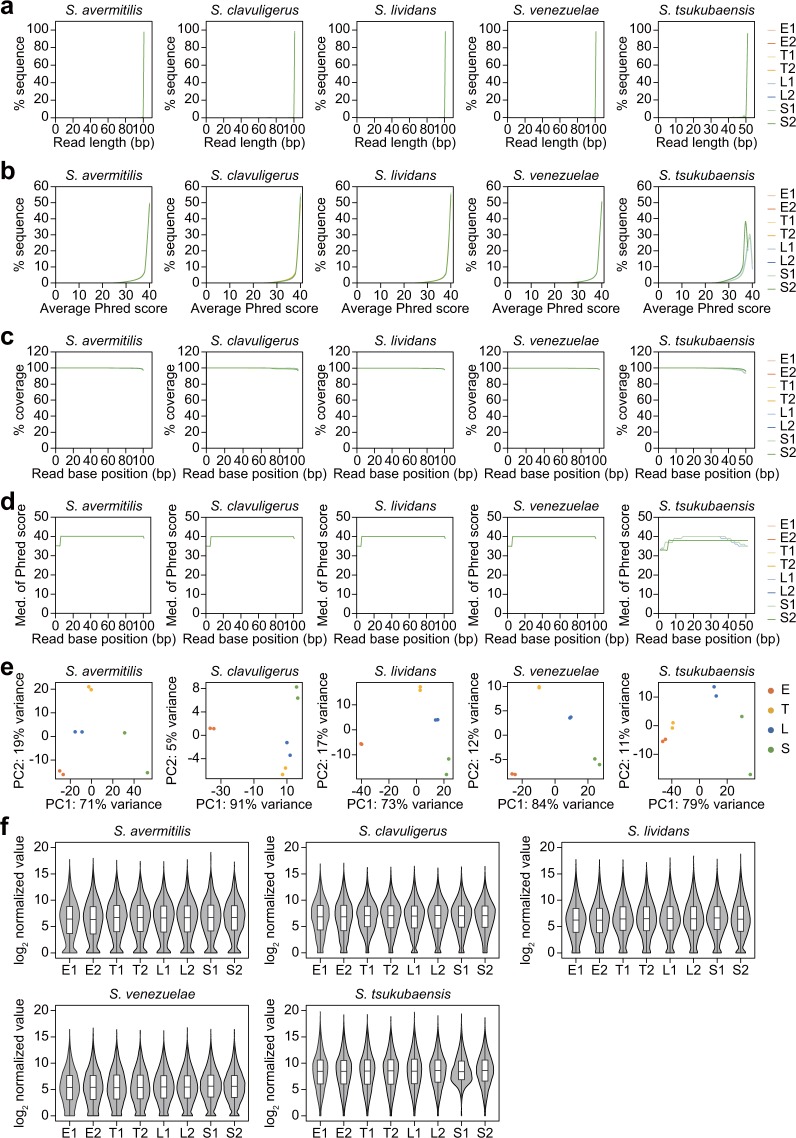

A total of 40 RNA-Seq runs that were applied to five species at four time points as duplicates yielded on average 16,430,039 reads (S. avermitilis), 13,961,155 reads (S. clavuligerus), 15,686,025 reads (S. lividans), 12,899,493 reads (S. venezuelae), and 51,144,650 reads (S. tsukubaensis). After trimming the sequencing reads by quality score and nucleotide length, more than 99.8% of the sequencing reads remained, which indicated high-sequencing quality. The remaining reads were used as input to generate sequencing QC reports in the CLC Genomics Workbench to validate the quality of the reads. At first, the overall read lengths were extremely long, corresponding to the sequencing read recipe (Fig. 2a, Table 1). For the four species that were sequenced with the 100-bp read recipe, the percentage of read lengths that were over 100 bp was more than 97.9%, and for S. tsukubaensis, which was sequenced with the 50-bp read recipe, the percentage of read lengths that were over 50 bp was more than 93.8%. Further, more than 98.6% (S. avermitilis), 98.9% (S. clavuligerus), 98.9% (S. lividans), 98.9% (S. venezuelae), and 96.4% (S. tsukubaensis) of the total reads exhibited an average Phred score of greater than 30, which indicates 99.9% base call accuracy (Fig. 2b). In addition, the quality of each base of the obtained reads was examined. The overall base positions of the sequencing reads were highly covered, and even the lowest average values of the coverage were 97.5% (S. avermitilis), 97.6% (S. clavuligerus), 97.8% (S. lividans), 98.3% (S. venezuelae), and 95.4% (S. tsukubaensis) at the last position, respectively (Fig. 2c). Moreover, the median values of the Phred scores per base position of the reads were consistently high across reads, with 40 scores in four species and 38 scores in S. tsukubaensis (Fig. 2d). From these quality validation results, we validated the quality of all obtained RNA sequencing reads for subsequent analysis.

Fig. 2.

Read quality analysis of RNA-Seq samples of five Streptomyces species at four growth phases. The replicate of each growth phase is represented as “1” or “2” after the growth phase. (a) Read length distribution of trimmed reads. (b) Distribution of average Phred scores of the trimmed reads. (c) The number of sequences that cover individual base positions normalized to the total number of sequences at each base position. (d) The distribution of the median Phred quality scores that were observed at each base position. (e) PCA plot of RNA-Seq mapped reads of each gene. (f) Violin and box plot of the log2 normalized expression values.

Assessment of transcriptome data

The qualified reads were mapped to each reference genome with a uniquely mapped percentage that ranges from 76.91% to 95.09% (S. avermitilis), 52.19% to 90.88% (S. clavuligerus), 60.15% to 87.08% (S. lividans), 67.35% to 86.23% (S. venezuelae), and 76.33% to 96.26% (S. tsukubaensis) (Table 1). The number of uniquely mapped reads at each gene was counted and normalized using the DESeq. 2 package in R33 to reduce variation between samples. Using the normalized values, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, which validated the high reproducibility of the sequencing data (Fig. 2e). The distribution of log2 (DESeq normalized value + 1) broadly ranged from 0 to 20 in the different growth phase samples (Fig. 2f).

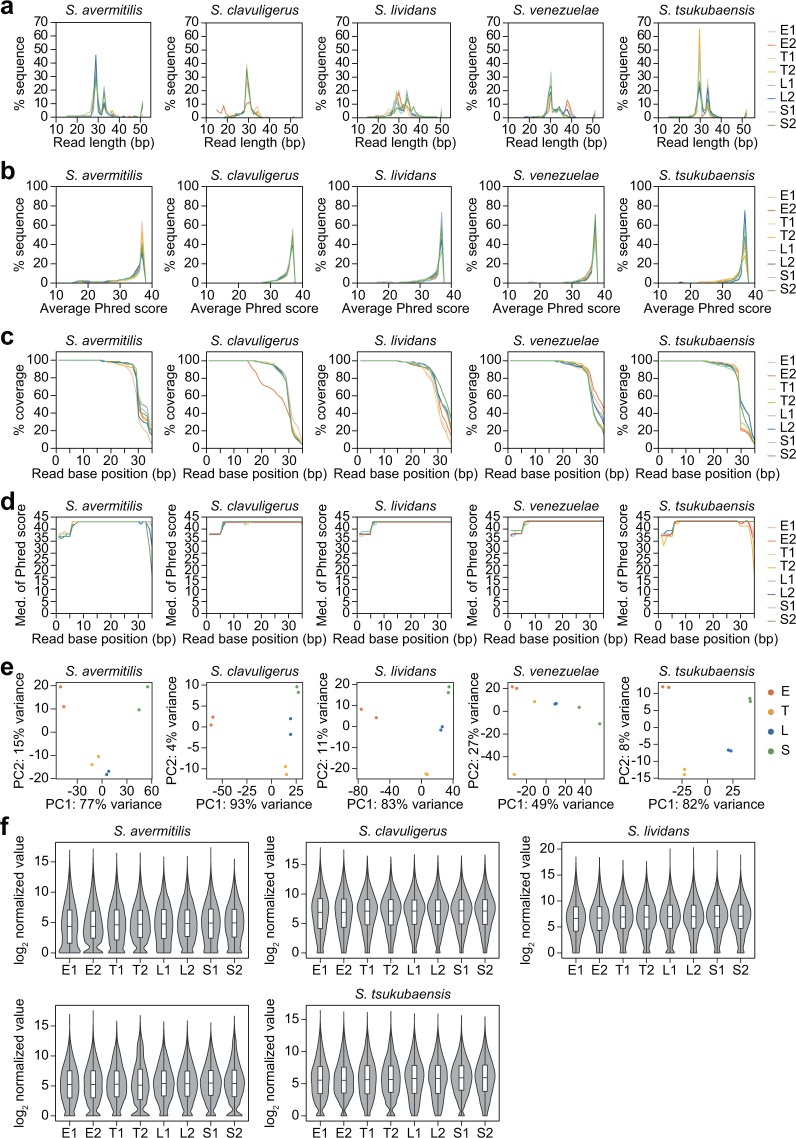

Ribosome profiling read quality validation

A total of 40 ribosome profiling reads were obtained from five Streptomyces species at four time points as duplicates. Unlike the RNA-Seq data, the trimmed reads were considered as raw sequences of the enriched RPF sequences, as additional PhiX control and adapter sequences that were involved in the ribosome profiling steps must be removed (Fig. 1a,b). Since the RPF fragments were selected by size, ranging from 26 to 34 bp, the 3′ end of the total 50 bp sequencing read contained non-RPF sequences, such as the 3′ adapter sequences, which do not represent the quality of the RPF reads. Thus, the QC reports on the trimmed reads were exported from CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen) to assess the quality of the RPF reads. The read length distribution exhibited a broad range from 20 to 40 bp, with one or two enriched peaks (Fig. 3a). The enriched peak sizes were comparable to the monosome-protected sizes, and they varied for different species, while they were more conserved for different growth phase samples of the same species. The differences in RNA degradation efficiency of RNase I or MNase across species may be the primary reason for the observed size differences54. Further, the read quality that was measured by the average Phred scores was generally high in all samples of the five species; the quality of more than 94% of the reads was higher than Q20, and more than 80% were higher than Q30 (Fig. 3b). Both per-sequence and per-base analyses of the read quality were observed. As the read size ranged mostly between 25 and 35 bp after adapter trimming, the base number coverage at each position of the 50 bp read dramatically decreased at the 3′ end (Fig. 3c). In terms of species, most of them exhibited the highest decline at 28 to 30 bp, which was consistent with the read length distribution (Fig. 3a). Given the base coverage, the median Phred score per base was demonstrated to be from 1 to 35 bp (Fig. 3d). The overall median of the quality score was approximately Q38, while the median score at the 5′ end was slightly lower than that of the middle section, and the score at the 3′ end of select species showed dramatic reductions. The low quality at the 3′ end may be due to some portions of identical long reads, which were somehow enriched during the size selection step of library construction, which stimulates wrong base calling. For the S. clavuligerus E2 sample, enriched peaks of less than 20 bp in length for approximately 10% of the total reads were unexpectedly found, along with decreased coverage at 15 bp, but these peaks did not seem to affect the overall read quality (Figs. 3a,c,d). Overall, most of the reads were shorter than 35 bp, and the read quality of all samples was high and suitable for downstream analyses.

Fig. 3.

Read quality analysis of ribosome profiling samples of five Streptomyces species at the four growth phases. The replicate of each growth phase is represented as “1” or “2” after the growth phase. (a) Read length distribution of trimmed reads. (b) Distribution of average Phred scores of the trimmed reads. (c) The number of sequences that cover individual base positions normalized to the total number of sequences at each base position. (d) The distribution of median Phred quality scores that were observed at each base position. (e) PCA plot of ribosome profiling mapped reads of each gene. (f) Violin and box plot of the log2 normalized expression values.

Assessment of translatome data

To examine the additional quality of the reads for the translational abundance of each gene, the trimmed reads were mapped to their corresponding genome. Based on the mapping parameter, some reads would be non-specifically aligned to more than one genomic position due to highly repetitive genomic regions, including rRNA genes. Approximately, 43.1 to 590.6 million reads (75.3 to 96.8% of the trimmed reads) were mapped when the non-specifically matched reads were randomly assigned to one of the mapped positions, while 1.8 to 103.9 million reads (1.3 to 54.9% of the reads) were uniquely mapped when the non-specifically matched reads were excluded (Table 2). These results suggest that the non-specifically matched reads were generally more than half of the total mapped reads. Further, the proportion of these reads varied in different samples even within the same species, which is because the rRNA was enriched during the monosome recovery step, and the efficiency of rRNA removal differed across samples55. S. clavuligerus showed the highest uniquely mapped read number and ratio among five species, with an average of 82.4 million reads (47% of the trimmed reads). The S. clavuligerus E2 sample showed a relatively lower mapped number (61.3 million reads, 30.6% of the trimmed reads) compared to other S. clavuligerus samples. S. venezuelae showed 34.2 to 69 million mapped reads (average 13.9% of the trimmed reads), respectively. The two early samples of S. lividans showed 97.2 and 81.1 million mapped reads (46 and 43.8% of the trimmed reads), respectively, while other samples showed low numbers (9.7 to 24.8 million mapped reads, 5.5 to 15.4% of the trimmed reads). S. tsukubaensis showed various ranges for the mapping read number; L2 and S2 samples showed 56 and 103 million mapped reads (35 and 53.9% of the trimmed reads), respectively, while other samples showed a lower number of mapped reads (1.9 to 8.8 million mapped reads, 1.5 to 6.9% of the trimmed reads). S. avermitilis showed the lowest number of mapped reads and ratio among the five species, with 2 to 13.1 million mapped reads (1.3 to 5.9% of the trimmed reads). Although the minimum mapped read number among the samples was 1.8 million, the numbers obtained are, based on several bacterial transcriptome studies, considered sufficient for analysis of the whole translational profile and differential expression levels of genes, as 1 to 5 million reads are suggested for high statistical significance56–59. Among the uniquely mapped reads, some reads were mapped within RNA genes, rather than protein-coding genes, which mostly corresponded to tRNA genes. These reads may be the fragments of tRNA and rRNA that were bound to the ribosome and then enriched during monosome recovery60. Therefore, further validation was performed using only the mapped reads of the protein-coding genes. A total of 1.1 to 19.5 million reads were mapped to protein-coding genes that were 4.3 to 81.0% of the uniquely mapped genes, which indicates a high ratio of tRNA gene-mapped reads (Table 2). To validate the mapped read quality, the reproducibility of the mapped read number among biological replicates was investigated by PCA. All replicates were found to exhibit high reproducibility (Fig. 3e). The mapped read quality for quantitative analysis, such as the differential translational abundance of genes during growth, was examined by the distribution of the normalized values at four different growth phases, as described in the “Methods” section. The overall log2 value (DESeq normalized value + 1) broadly ranged from 0 to 20, which was considered significant to analyze the translational abundance in different growth phases (Fig. 3f). In conclusion, the mapped reads were confirmed to exhibit high quality in terms of sequencing depth, reproducibility, and translational abundance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF10CC1016517) and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (2018M3A9F3079664 to B.-K.C.) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT).

Author contributions

B.-K.C. conceived and supervised the study. W.K., S.H., N.L. and B.-K.C. designed the experiments. W.K., S.H., N.L., and Y.L. performed the experiments. W.K., S.H., N.L., Y.L., S.C., B.P. and B.-K.C. analyzed the data. W.K., S.H., N.L., B.P. and B.-K.C. wrote the manuscript.

Code availability

Versions and parameters of all the bioinformatic tools that were used in this work are described in the “Methods” section.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Woori Kim, Soonkyu Hwang, Namil Lee.

References

- 1.Flardh K, Buttner MJ. Streptomyces morphogenetics: dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang KS, Kim HU, Charusanti P, Palsson BO, Lee SY. Systems biology and biotechnology of Streptomyces species for the production of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014;32:255–268. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Procopio RE, Silva IR, Martins MK, Azevedo JL, Araujo JM. Antibiotics produced by Streptomyces. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;16:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee N, et al. Synthetic biology tools for novel secondary metabolite discovery in Streptomyces. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;29:667–686. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1904.04015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worthen DB. Streptomyces in nature and medicine: The antibiotic makers. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 2008;63:273–274. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jrn016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demain AL. Importance of microbial natural products and the need to revitalize their discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41:185–201. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgson DA. Primary metabolism and its control in streptomycetes: A most unusual group of bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 2000;42:47–238. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(00)42003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam MT, et al. Metabolic modeling and analysis of the metabolic switch in Streptomyces coelicolor. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:202. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rokem JS, Lantz AE, Nielsen J. Systems biology of antibiotic production by microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:1262–1287. doi: 10.1039/b617765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibb M. The regulation of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbiology. 1996;142:1335–1344. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong Y, et al. The dynamic transcriptional and translational landscape of the model antibiotic producer Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Nat Commun. 2016;7:11605. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wentzel A, et al. Optimized submerged batch fermentation strategy for systems scale studies of metabolic switching in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) BMC Syst Biol. 2012;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieselt K, et al. The dynamic architecture of the metabolic switch in Streptomyces coelicolor. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang JQ, Lih CJ, Pan KH, Cohen SN. Global analysis of growth phase responsive gene expression and regulation of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways in Streptomyces coelicolor using DNA microarrays. Gene Dev. 2001;15:3183–3192. doi: 10.1101/gad.943401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, et al. Transcriptomics analyses reveal global roles of the regulator AveI in Streptomyces avermitilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;298:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berghoff BA, et al. Integrative “omics”-approach discovers dynamic and regulatory features of bacterial stress responses. Plos Genet. 2013;9:e1003576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters LS, Storz G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009;136:615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brar GA, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling reveals the what, when, where and how of protein synthesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:651–664. doi: 10.1038/nrm4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang S, et al. Primary transcriptome and translatome analysis determines transcriptional and translational regulatory elements encoded in the Streptomyces clavuligerus genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:6114–6129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, Y. et al. The transcription unit architecture of Streptomyces lividans TK24. Frontiers in Microbiology10, 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02074 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jones GH. RNA degradation and the regulation of antibiotic synthesis in Streptomyces. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:419–429. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paradkar A. Clavulanic acid production by Streptomyces clavuligerus: biogenesis, regulation and strain improvement. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013;66:411–420. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barreiro C, et al. Draft genome of Streptomyces tsukubaensis NRRL 18488, the producer of the clinically important immunosuppressant tacrolimus (FK506) J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3756–3757. doi: 10.1128/JB.00692-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotson IK. The avermectins: A new family of antiparasitic agents. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1982;53:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nepal KK, Wang G. Streptomycetes: Surrogate hosts for the genetic manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters and production of natural products. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myronovskyi M, Luzhetskyy A. Heterologous production of small molecules in the optimized Streptomyces hosts. Nat Prod Rep. 2019;36:1281–1294. doi: 10.1039/c9np00023b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung WS, et al. Heterologous expression of tylosin polyketide synthase and production of a hybrid bioactive macrolide in Streptomyces venezuelae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:763–769. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Yang I, Yoon YJ. Developing Streptomyces venezuelae as a cell factory for the production of small molecules used in drug discovery. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2015;38:1606–1616. doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0638-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vecchione JJ, Alexander B, Jr., Sello JK. Two distinct major facilitator superfamily drug efflux pumps mediate chloramphenicol resistance in Streptomyces coelicolor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4673–4677. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00853-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Dominguez M, Martin JF, Mahro B, Demain AL, Liras P. Efficient plasmid transformation of the β-lactam producer Streptomyces clavuligerus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1376–1381. doi: 10.1128/AEM.53.6.1376-1381.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome. Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP158023

- 36.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP188290

- 37.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP103795

- 38.Lee Y, 2019. The transcription unit of Streptomyces lividans. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB31507

- 39.Kim W, 2019. Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC15439. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB34219

- 40.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932518

- 41.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932519

- 42.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932520

- 43.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932521

- 44.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932522

- 45.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932523

- 46.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932524

- 47.2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932525

- 48.Kim W, 2020. Transcriptome and translatome profiles of Streptomyces species in different growth phases. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB36893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lee Y, 2020. Transcriptome and translatome of Streptomyces avermitilisMA-4680. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE118597

- 50.Hwang S, 2019. Primary transcriptome and translatome analysis determines transcriptional and translational regulatory elements encoded in the Streptomyces clavuligerus genome. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE128216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Hwang S, 2020. Ribosome profiling of Streptomyces griseus NBRC13350 and Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC15439. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE138278

- 52.Lee N, 2019. Ribosome pausing at the AT-rich codons regulates the protein expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters in the Streptomyces tsukubaensis NRRL 18488. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE97637

- 53.Kim W, et al. Transcriptome and translatome profiles of Streptomyces species in different growth phases. Figshare. 2020 doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4867830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calviello L, Ohler U. Beyond read-counts: Ribo-seq data analysis to understand the functions of the transcriptome. Trends Genet. 2017;33:728–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diament A, Tuller T. Estimation of ribosome profiling performance and reproducibility at various levels of resolution. Biol Direct. 2016;11:24. doi: 10.1186/s13062-016-0127-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haas BJ, Chin M, Nusbaum C, Birren BW, Livny J. How deep is deep enough for RNA-Seq profiling of bacterial transcriptomes? BMC Genomics. 2012;13:734. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rey FE, et al. Dissecting the in vivo metabolic potential of two human gut acetogens. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22082–22090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westermann AJ, Gorski SA, Vogel J. Dual RNA-seq of pathogen and host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:618–630. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McClure R, et al. Computational analysis of bacterial RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Latif H, et al. A streamlined ribosome profiling protocol for the characterization of microorganisms. Biotechniques. 2015;58:329–332. doi: 10.2144/000114302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP158023

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP188290

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP103795

- Lee Y, 2019. The transcription unit of Streptomyces lividans. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB31507

- Kim W, 2019. Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC15439. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB34219

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932518

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932519

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932520

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932521

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932522

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932523

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932524

- 2020. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX6932525

- Kim W, 2020. Transcriptome and translatome profiles of Streptomyces species in different growth phases. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJEB36893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, 2020. Transcriptome and translatome of Streptomyces avermitilisMA-4680. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE118597

- Hwang S, 2019. Primary transcriptome and translatome analysis determines transcriptional and translational regulatory elements encoded in the Streptomyces clavuligerus genome. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE128216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hwang S, 2020. Ribosome profiling of Streptomyces griseus NBRC13350 and Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC15439. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE138278

- Lee N, 2019. Ribosome pausing at the AT-rich codons regulates the protein expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters in the Streptomyces tsukubaensis NRRL 18488. Gene Expression Omnibus. GSE97637

Data Availability Statement

Versions and parameters of all the bioinformatic tools that were used in this work are described in the “Methods” section.