Abstract

Background

In the rapidly changing landscape of undergraduate medical education (UME), the roles and responsibilities of clerkship directors (CDs) are not clear.

Objective

To describe the current roles and responsibilities of Internal Medicine CDs.

Design

National annual Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine (CDIM) cross-sectional survey.

Participants

One hundred twenty-nine clerkship directors at all Liaison Committee on Medical Education accredited US medical schools with CDIM membership as of September 1, 2017.

Main Measures

Responsibilities of core CDs, including oversight of other faculty, and resources available to CDs including financial support and dedicated time.

Key Result

The survey response rate was 83% (107/129). Ninety-four percent of the respondents oversaw the core clerkship inpatient experience, while 47.7% (n = 51) and 5.6% (n = 6) oversaw the outpatient and longitudinal integrated clerkships respectively. In addition to oversight, CDs were responsible for curriculum development, evaluation and grades, remediation, scheduling, student mentoring, and faculty development. Less than one-third of CDs (n = 33) received the recommended 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE) support for their roles, and 15% (n = 16) had less than 20% FTE support. An average 0.41 FTE (SD .2) was spent in clinical work and 0.20 FTE (SD .21) in administrative duties. Eighty-three percent worked with other faculty who assisted in the oversight of departmental UME experiences, with FTE support varying by role and institution. Thirty-five percent of CDs (n = 38) had a dedicated budget for managing their clerkship.

Conclusions

The responsibilities of CDs have increased in both number and complexity since the dissemination of previous guidelines for expectations of and for CDs in 2003. However, resources available to them have not substantially changed.

KEY WORDS: undergraduate medical education, clerkship, internal medicine clerkship

INTRODUCTION

Clerkship Directors (CDs) face new challenges as medical education evolves. Changes in the number of learners, clinical learning environments, regulatory requirements, clinical and administrative workload, and curricular content have all contributed to increasing the complexity of the CD role.1, 2 In 2003, a collaborative through the Alliance for Clinical Education (ACE) published a description of expectations for CDs.3 However, expectations of both Schools of Medicine and CDs from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) have evolved since the Carnegie call for Medical Education Reform.4–6 CDs have now assumed an integral role in maintaining the quality and comparability of clerkship experiences for students.

Concurrently, the needs of our evolving health care system have created opportunities to develop new curricular focus areas to better prepare future physicians for practice. There are increasing expectations to embed emerging content, such as health systems sciences (e.g., value-based care and population health), the opioid epidemic, interprofessional collaboration, professional role formation, and diversity issues into internal medicine clerkship curricula.7–10 Additionally, educators at both the undergraduate and graduate medical education levels continue to grapple with the challenges of optimizing the learning and working environment for all learners.11, 12

Adding to this complexity, the structure of clerkships is evolving as the conceptual model of clinical education moves away from a more traditional “blocked time-in-clerkship” model towards individualized learning adapted to the needs and professional goals of each learner.13–15 Integrated models of learning, such as longitudinal integrated clerkships (LICs), specialty track-based curricula (e.g., leadership, education), and basic science integration, are becoming more prevalent in the clinical years.16–19 To adapt to these programmatic changes, many clerkships have expanded to additional clinical sites, which require oversight. CDs also face the challenge of evolving their assessment strategies of learner performance as medical education moves towards a competency-based framework. Newer outcome measures such as Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency have created new opportunities and challenges for the development of assessment tools.20–22

These factors contribute to a clerkship experience that has become increasingly complex and nuanced over time. However, the specific roles and responsibilities, skill set, and resources for current CDs in this changing landscape of clerkship structures and regulations are not well-characterized. The authors hypothesized that these roles and responsibilities of CDs have become more complex and diverse over time, and that CDs have accrued key responsibilities that require both more time and different skill sets, leading to a need for different resources and support.

METHODS

The Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine (CDIM) is a charter organization of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM), a nonprofit professional association that consists of undergraduate and graduate internal medicine educators and administrators. In September 2017, Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine (CDIM) launched its annual, voluntary, and confidential survey of CDs at all LCME-accredited US medical schools with CDIM membership as of September 1, 2017. CDIM members designated as “clerkship director” received a personal email invitation to complete the web-based survey. Only one individual per member school received the invitation. Approximately 90% of LCME-accredited schools were represented in CDIM as of the survey period.

The survey was administered via Qualtrics survey software using Secure Socket Layer encryption, and included five email reminders to non-respondents. Select CDIM Survey and Scholarship Committee members also sent personal email reminders to non-respondents. The survey protocol was granted full institutional review board exempt status from the University of North Carolina Office of Human Research Ethics (Study #: 17-1954).

The survey questions were reviewed and modified for construct validity through several iterations by members of the CDIM Survey and Scholarship Committee. The committee further revised the survey instrument after the CDIM Council reviewed it for content in July 2017. The final survey consisted of 79 questions, including multiple-choice, numeric-only, and open-text response options, with logical skip patterns and display logic as needed.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis was performed in Stata 14.2 (StataCorp 2015), and included descriptive statistics and statistical significance tests for group-based differences, using the Pearson chi-square statistic or Fisher’s exact test. Differences were considered statistically significant at the p ≤ .05 level. Following data collection, a variable to denote respondents’ and non-respondents’ medical school as “public” or “private” was merged into the dataset, using publicly available data23 and visits to medical school websites. Using membership files, data on respondents’ and non-respondents’ gender and US Census Bureau geographic region of their school were also merged into the dataset.24 Respondent contact information was then removed from the dataset, to de-identify CDIM members and ensure data privacy. Due to item nonresponse or survey conditional logic, some denominators varied and did not sum to 107 in the presentation of results.

RESULTS

The survey closed on December 17, 2017, with a response rate of 83% (n = 107). There were no statistically significant differences between respondents and non-respondents based on medical school type (public/private), US Census Bureau region, and gender.

ROLES, RESPONSIBILITIES, REPORTING, AND RESOURCES OF INTERNAL MEDICINE CLERKSHIP DIRECTORS

Oversight Roles

Many CDs oversaw multiple educational programs within their departments. Among respondents, 94.4% (n = 101) reported overseeing the core clerkship inpatient experience whereas 47.7% (n = 51) oversaw the clerkship outpatient experience, and 5.6% (n = 6) oversaw a longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC). Respondents indicated other responsibilities as well, with 32.7% (n = 35) indicating that they also oversee one or more electives, and 42% (n = 46) indicating that they oversee one or more subinternships. Respondents oversaw a mean of 2.4 (SD 1.2) clinical experiences, with 70% (n = 75) bearing responsibility for more than one experience.

Oversight Responsibilities

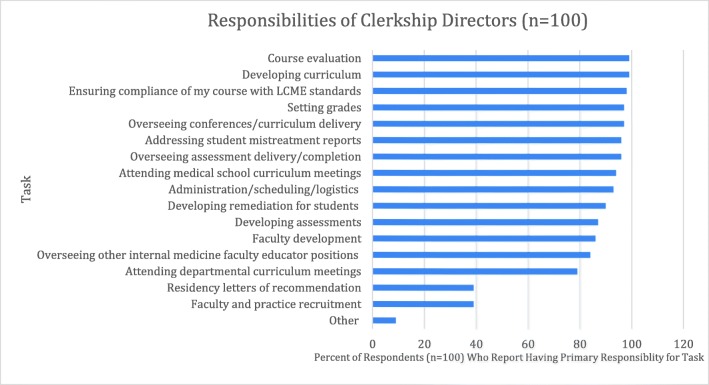

The majority of respondents who reported having oversight of core inpatient or outpatient experiences bore primary responsibility for most of the tasks listed in Figure 1. Nine percent of respondents (n = 9) reported additional tasks, including career advising for students, oversight of departmental letters for residency applications, and oversight of administrative staff. Distribution of responsibilities for tasks was similar for those CDs with primary oversight over other educational experiences (core outpatient experiences, one or more subinternships or electives, and LICs), with most respondents having primary responsibility for the same tasks related to each individual educational experience.

Fig. 1.

Responsibilities of Clerkship Directors.

Full-time Equivalent Support

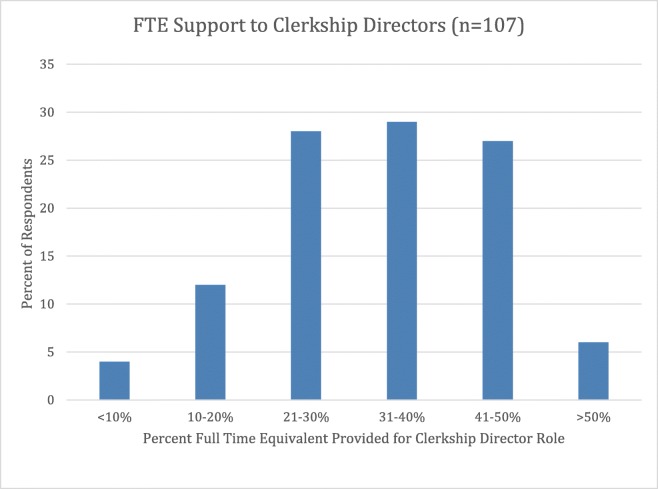

Less than one-third of CDs (n = 33) had 41% or more full-time equivalent (FTE) support comparable with the 50% FTE support recommended in the 2003 ACE guidelines (Fig. 2). Fifteen percent (n = 16) of CDs had 20% FTE support or less. There is wide variation in the allocation of the remainder of CDs’ time. Most spent a substantial portion of their time doing clinical work (mean 0.41 FTE, SD 0.20) and administrative duties (mean 0.2 FTE, SD. 0.21). Few CDs reported dedicated time allocation to research (mean 2.2%, SD 6.7).

Fig. 2.

FTE Support to Clerkship Directors.

Reporting Structure

In their primary (greatest funded) academic role, 33.3% (n = 56) of CDs reported to their department chair, and 31.0% (n = 52) to their division or section chief. Twenty percent (n = 34) reported to the dean of curriculum (or equivalent) at the medical school, and 11% (n = 18) to another department leader (e.g., vice chair). In their role as CDs, 40.2% (n = 70) reported to the dean of curriculum (or equivalent) at the medical school, 31% (n = 54) to their department chair, and 24.7% (n = 43) to another department leader (e.g., vice chair). Of the 83% (n = 86) of respondents who reported sharing oversight of internal medicine clinical experiences with other faculty, 76% (n = 65) reported that the other faculty reported directly to the CD.

CLERKSHIP BUDGET

Thirty-five percent (n = 38) of CDs had a dedicated budget for managing their clerkship. The three most common budget items were National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) exams (25.3%, n = 24), conference fees for faculty development (24.2%, n = 23), and social activities for students (19.0%, n = 18). Other items included faculty recruitment (6.3%, n = 6), funds for student development such as conference fees (4.2%, n = 4), pagers (4.2% n = 4), and social activities for faculty (5.3%, n = 5). Free text responses for other items covered by the budget included office supplies, administrative support, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), food for orientation sessions and CD meetings, license fees for online curriculum resources (e.g., Aquifer),25 and compensation for small group faculty facilitators.

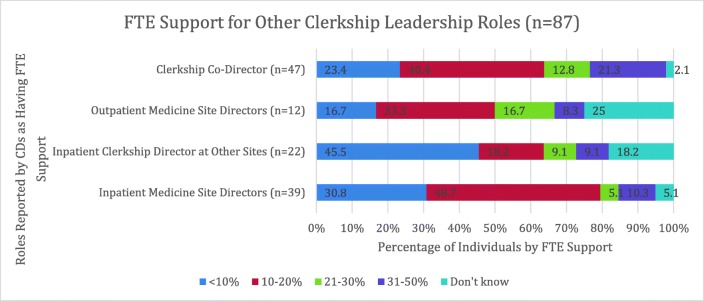

Roles, Responsibilities, Reporting, and Resources of Other Departmental Faculty Who Assist in Clinical Rotations

The majority (82.9%, n = 87) of primary internal medicine CDs worked with other faculty who assisted in overseeing undergraduate clinical experiences for the department, with FTE support varying significantly by role and institution. These faculty roles included clerkship co-directors, inpatient CDs and site directors, ambulatory CDs, and site directors (Fig. 3). Of these 87 CDs, 72 were aware of the total faculty FTE designated for clerkship support. The mean FTE was 1.4 (SD: 1.1) and the median FTE was 1, with wide range as depicted in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

FTE Support for Other Clerkship Leadership Roles.

DISCUSSION

In 2003, the Alliance for Clinical Education (ACE) released a collaborative statement listing eleven essential products for which CDs should be held responsible.3 CDs were required to provide the following: a full-time clinical experience that meets medical school and departmental objectives for the clerkship, a written set of core educational goals and objectives, all schedules, materials that support the clerkship curriculum, expectations and standards for student participation in patient care at clinical sites, strategy for assessment of individual students and for programmatic evaluation, examinations, grades, student remediation plans, reports on sufficiency and comparability of clerkship sites, and advising for residency applicants. Although the results of the 2017 survey demonstrate that the majority of respondents continue to have primary responsibility for these tasks, the roles and responsibilities of internal medicine CDs have evolved considerably since that time given the increasingly complex state of undergraduate medical education. Additional responsibilities of CDs include the recruitment of new faculty and sites, faculty development, addressing student mistreatment reports, attending departmental and medical school curriculum meetings, ensuring compliance with LCME standards, training and managing additional faculty leaders such as site clerkship faculty and co-directors, and navigating the increasingly complex and centralized administrative structure of the institution. Clerkship structures have also become more complex, with a rising number of institutions creating LICs, combined clerkships, and other models that do not follow the traditional clerkship block structure.16 CDs report to multiple individuals, including department chairs, vice chairs and curriculum deans, further underscoring the complexity of the UME structure. CDs are now spending additional time training, mentoring, and supervising faculty educators associated with these curricular models. It is not clear whether CDs have obtained the training, mentorship, time allocation, and resources necessary to be successful in these roles.

The time dedicated for clerkship leadership should reflect the increasing diversity of clerkship experiences available to students at various clerkship sites (i.e., inpatient, outpatient, regional campuses, rural sites), as well as the increasingly different approaches to the clerkship directorship model. The 2003 ACE guidelines recommended that at least 50% FTE support be allocated for a CD position. In 2007, the average salary support for a CD role in multiple disciplines nationally was 22%.26 At that time, 65% of IM CDs reported having 15 h or less of protected time per week for CD duties.27 In the current survey, the majority of CDs reported a range of 21–50% protected time for directing the clerkship, while a substantial portion (15%) reported having less than 20% protected time.

Internal medicine clerkships are now much more likely to be directed by teams of individuals rather than by one CD. In 2007, 32% of IM CDs reported that they acted as the sole internal medicine CD for their institution,26 whereas in the current survey, 82.9% of CDs reported having additional faculty assistance in directing the clerkship. Roles for supporting faculty varied in responsibilities (co-directors, inpatient and outpatient site directors at both the main site and affiliate sites, as well as in protected time, ranging from 0 to 0.40 FTE). Although having more faculty educator support for clerkships is beneficial, it adds to the growing complexity of clerkship administration; training and supervision of other clerkship faculty leaders has become an additional responsibility for CDs that requires more time, resources, and skills. The ideal distribution of FTE allotted for the various clerkship responsibilities and oversight roles in comparison with the FTE that should be dedicated specifically to the CD is unclear.

Careful attention to the resources provided to CDs for their own and their clerkship faculty professional development is critical. To be a successful CD, faculty who serve in this role may require additional skill development in leadership, continuous quality improvement, scholarship, in-depth knowledge of accreditation standards, understanding of institutional relationships with other local health organizations, and knowledge of the structure and oversight of the entire medical school curriculum in order to effectively navigate through their new responsibilities. To achieve these goals, CDs would require increased financial support for training and professional development. National organizations dedicated to the professional development of medical educators may need to widen the scope of their offerings to respond to the changing needs of their CD membership.

In addition, CDs require the support and resources necessary to promote wellness and mitigate burnout, which is a widely recognized challenge in the medical education community.28, 29 Twenty-five percent of respondents to the 2018 CDIM survey reported symptoms of burnout, and 35% reported that they were likely to resign in the next year.30 Leaders in academic medicine must be aware of the risk of burnout in CDs as they adapt to their increasingly complex and demanding roles, and mindful of the fact that unmanaged burnout in a faculty member who leads an educational program can have far-reaching effects on the next generation of learners.

A dedicated clerkship budget is also an important area for improvement. In 2003, ACE recommended “a defined budget for personnel, materials, and travel sufficient to meet the educational requirements of the clerkship and the professional development of the CD.”3 In the CDIM 2005 survey, 63% of CDs reported that they had a defined budget that was sufficient to meet the needs of the clerkship.31 In the current survey, only 35% of CDs reported having a dedicated budget, with many budget items being non-discretionary items such as pagers and NBME exams. Current budget structures appear misaligned with the increasing needs of CDs, both for their own professional development and the faculty they lead.

This study has several limitations. Within the survey, the item response rate varied for certain questions, which may be due to survey fatigue or the non-applicability of the items to respondents. However, the overall response rate of 83% suggests that these results are a close representation of CDIM member schools and their CDIM-designated CD members in the US Surveys were sent to one representative of each medical school, who had previously been identified by the home institution as the primary CD. Language contained within the survey requested that the recipient should alert CDIM if they no longer served in the CD role. It is possible that respondents who were no longer in this role may have completed the survey using outdated information. Additionally, if an individual was part of a faculty team managing a clerkship and had divided responsibilities (for example, inpatient and outpatient clerkship co-directors), their responses may not be reflective of the overall CD responsibilities and resources in an individual institution. The development of the current survey items was independent of the language used to describe essential products in the 2003 ACE recommendations, and therefore a parallel comparison between the two surveys was not possible. However, the items in the current survey were designed with the purpose to better understand the present roles and responsibilities of CDs in an evolving UME landscape, and to identify CDs needs not currently addressed or met.

Our data suggest that expectations of CDs are evolving and becoming more demanding, with an increased number and complexity of roles. CDs perform these roles in an increasingly diverse set of UME curricular structures that include LICs, blocked clerkships, and other unique curricular tracks. Many CDs are now responsible for additional tasks, including the oversight of clerkship faculty with co-leadership roles recruitment of affiliate clinical sites and community faculty, and conducting faculty development for clerkship faculty. Resources available to IM CDs, however, have not substantially changed, and budgetary support has decreased.

As medical education continues to evolve, so will the diversity of roles and responsibilities of CDs. We propose that a single set of recommendations for resources and expectations of a CD according to the 2003 ACE guidelines may no longer be sufficient to adequately respond to the complex needs of students, CDs, and institutions, and various structures of clerkships in medical schools. More research is needed to fully understand these needs and provide appropriate support and resources to the IM CDs. We encourage other national leadership to gather similar information specific to their specialties, and for accrediting bodies to take the changing landscape of UME into account as they further refine requirements for successful accreditation. Current ACGME guidelines, which take into account the number and geographic distribution of learners when determining program needs, may serve as a springboard for the development of new guidelines. The authors propose revisiting and updating guidelines for expectations of CDs that will take into account the current needs of students, faculty, institutions, and accrediting bodies, as well as the projected needs as UME continues to evolve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CDIM Survey and Scholarship Committee, CDIM Council members, and all CDIM members.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ng VK, McKay A. Challenges of multisite surgical teaching programs: a review of surgery clerkship. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christner JG, Dallaghan GB, Briscoe G, et al. The community preceptor crisis: recruiting and retaining community-based faculty to teach medical students—a shared perspective from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):329–336. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1152899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pangaro L, Bacicha J, Brodkey A, et al. Expectations of and for clerkship directors: a collaborative statement from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(3):217–222. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1503_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of the American Medical Colleges . Academic Quality and Public Accountability in Medical Education: The 75-Year History of the LCME. Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School 2019. http://lcme.org/publications/#Standards. Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

- 6.Irby, D., Cooke, M., & O’Brien, B. C. (2010). Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med, 85:2, 220–227. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20107346. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lin SY, Schillinger E, Irby DM. Value-added medical education: engaging future doctors to transform health care delivery today. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):150–151. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korenstein D. Charting the route to high-value care: the role of medical education. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2359–2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeser JD, Schatman ME. Chronic pain management in medical education: a disastrous omission. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(3):332–335. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1297668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandraki I, Hernandez CA, Torre DM, Chretien KC. Interprofessional education in the internal medicine clerkship post-LCME standard issuance: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):871–876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruppen L, Irby DM, Durning SJ, & Maggio, LA. Interventions designed to improve the learning environment in the health professions: a scoping review. MedEdPublish. 7(3):73, 10.15694/mep.2018.0000211.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Nordquist J, Hall J, Caverzagie K, et al. The clinical learning environment. Med Teach 2019:1–7. 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1566601 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cangiarella J, Fancher T, Jones B, et al. Three-year MD programs: perspectives from the consortium of accelerated medical pathway programs (CAMPP) Acad Med. 2017;92(4):483–490. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazio SB, Ledford CH, Aronowitz PB, et al. Competency-based medical education in the internal medicine clerkship: a report from the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine undergraduate medical education task force. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):421–427. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):S42–S48. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worley P, Couper I, Strasser R, et al. A typology of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):922–932. doi: 10.1111/medu.13084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duque G, Demontiero O, Whereat S, et al. Evaluation of a blended learning model in geriatric medicine: a successful learning experience for medical students. Australas J Ageing. 2013;32(2):103–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson BL, VanDerKolk K, Bauler T, Cole S. Integration of biomedical sciences in the family medicine clerkship using case-based learning. Med Sci Educ. 2017;27(4):815–820. doi: 10.1007/s40670-017-0484-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalo JD, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, et al. Health systems science curricula in undergraduate medical education: identifying and defining a potential curricular framework. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):123–131. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell DE, Carraccio C. Toward competency-based medical education. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):3–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1712900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ten Cate O, Hart D, Ankel F, et al. Entrustment decision making in clinical training. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):191–198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sklar D. Competencies, milestones, and entrustable professional activities: what they are, what they could be. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):395–397. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Accredited MD Programs in the United States. http://lcme.org/directory/accredited-u-s-programs/. Accessed Dec 2017.

- 24.United States Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed Dec 2017.

- 25.Courses: Teaching and learning solutions. Aquifer (online). https://www.aquifer.org/courses/. Accessed 12 Oct 2019.

- 26.Ephgrave K, Margo KL, White C. Core clerkship directors: their current resources and the rewards of the role. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):710–715. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cdf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) CDIM Annual Survey of Core Internal Medicine Clerkship Directors Study Database. Alexandria: AAIM; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Thomas MR, Durning SJ. Brief observation: a national study of burnout among internal medicine clerkship directors. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):310–312. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West CP, Halvorsen AJ, Swenson SL, McDonald FS. Burnout and distress among internal medicine program directors: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1056–1063. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2349-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) 2018 CDIM Annual Survey of Core Internal Medicine Clerkship Directors Study Database. Alexandria: AAIM; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durning SJ, Papp KK, Pangaro LN, Hemmer P. Expectations of and for internal medicine clerkship directors: how are we doing? Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(1):65–69. doi: 10.1080/10401330709336626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]