Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common in the primary care setting. Early interventions may prevent progression of renal disease and reduce risk for cardiovascular complications, yet quality gaps have been documented. Successful approaches to improve identification and management of CKD in primary care are needed.

Objective

To assess whether implementation of a primary care improvement model results in improved identification and management of CKD

Design

18-month group-randomized study

Participants

21 primary care practices in 13 US states caring for 107,094 patients

Interventions

To promote implementation of CKD improvement strategies, intervention practices received clinical quality measure (CQM) reports at least quarterly, hosted an on-site visit and 2 webinars, and sent clinician/staff representatives to a “best practice” meeting. Control practices received CQM reports at least quarterly.

Main Measures

Changes in practice adherence to a set of 11 CKD CQMs

Key Results

We observed significantly greater improvements among intervention practices for annual screening for albuminuria in patients with diabetes or hypertension (absolute change 22% in the intervention group vs. − 2.6% in the control group, p < 0.0001) and annual monitoring for albuminuria in patients with CKD (absolute change 21% in the intervention group vs. − 2.0% in the control group, p < 0.0001). Avoidance of NSAIDs in patients with CKD declined in both intervention and control groups, with a significantly greater decline in the control practices (absolute change − 5.0% in the intervention group vs. − 10% in the control group, p < 0.0001). There were no other significant changes found for the other CQMs. Variable implementation of CKD improvement strategies was noted across the intervention practices.

Conclusions

Implementation of a primary care improvement model designed to improve CKD identification and management resulted in significantly improved care on 3 out of 11 CQMs. Incomplete adoption of improvement strategies may have limited further improvement. Improving CKD identification and management likely requires a longer and more intensive intervention.

KEY WORDS: chronic kidney disease, primary care, quality improvement

An estimated 15% of adults in the USA have chronic kidney disease (CKD).1 Although 95% of these individuals have early disease2 and most will not progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), CKD is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality.3, 4 Early identification of CKD and aggressive risk reduction can reduce both development of ESRD and CVD, producing a major public health impact.

Given its high prevalence, the burden of care for most patients with CKD often falls on primary care providers (PCPs)5, 6 who play a critical role in identifying at-risk patients, managing early-stage CKD, monitoring for progression, controlling cardiovascular disease risk factors, and ensuring timely referral to nephrologists for patients with advanced stages of CKD.2, 4, 7 CKD, defined as reduced renal function and/or albuminuria, is a cardiovascular risk factor independent of other risk factors such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension.3, 8 Screening for CKD in at-risk patients can therefore lead to identification of patients at increased risk for both cardiovascular disease and worsening kidney disease.9, 10 PCPs can address cardiovascular risk factors in patients with CKD by prescribing statins11 and using renal protective agents such as angiotensin-converting inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to reduce albuminuria and lower blood pressure.12, 13 The use of ACEIs or ARBs,14 blood pressure control15 and glycemic control,16, 17 and avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)18–21 can also slow progression of CKD. Despite this potential for PCPs to address cardiovascular risk factors and implement approaches to slow the progression of renal disease in patients with CKD, large quality gaps have been documented, such as infrequent laboratory monitoring, inadequate use of ACEIs or ARBs, poor blood pressure control, suboptimal lipid and glycemic control, and inappropriate use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).21–23

Several barriers interfere with primary care management of CKD patients. Providers are often not aware of CKD clinical practice guidelines or risk factors for CKD.5, 24, 25 CKD also remains under-recognized and underdiagnosed.26 Similarly, patients with CKD are often unaware of their diagnosis.26, 27 Other barriers include poor patient-physician communication,28, 29 concern about overdiagnosis of CKD, and lack of communication and coordination between PCPs and nephrologists about their roles in CKD management.30, 31 In addition, there are conflicting guidelines about screening for CKD in asymptomatic patients due to concerns including the psychological effects of being labeled as having a disease, costs, and adverse effects of diagnosis and treatment.32, 33 However, many professional organizations support selective screening in at-risk groups such as those with diabetes or hypertension.20, 34–37

Practical, acceptable, sustainable, and cost-efficient approaches to translate research for prevention and management of CKD into primary care practice are needed. The Translating CKD Research into Primary Care Practice study was a group-randomized study assessing the impact of a primary care practice–based improvement model on CKD identification and management as measured by performance on a set of primary care CKD clinical quality measures (CQMs). The purpose of this paper is to report the primary results from the 18-month study.

METHODS

Study Practices

The Translating CKD Research into Primary Care Practice study was conducted from November 1, 2016, to April 30, 2018, within PPRNet, a network of primary care practices across the USA whose members use electronic health records (EHRs) and pool data for CQM reporting for quality improvement, regulatory, and research purposes. All internal medicine and family medicine practices active in PPRNet as of July 1, 2016, were invited to participate through a listserv recruitment email. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

CKD Clinical Quality Measures

We previously developed a set of CKD clinical quality measures (CQMs) that are face valid and useful for primary care providers using a consensus process.38 For this study, this set of CQMs was updated to reflect current clinical practice guidelines19, 20 (see Table 3). All data were obtained from batch extracts of summary of care documents in consolidated-Clinical Document Architecture (c-CDA) format from the EHRs of participating practices. Active patients were defined as patients 18 and older with a visit within the past year. Because CKD is under-recognized and diagnostic codes for CKD are not always reliable,22 patients were considered to have CKD if the most recent eGFR was < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and an eGFR > 90 days before the most recent eGFR was also < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, or if the patient had an albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g. Diagnoses of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HTN) were defined by relevant ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes listed as either a problem or a diagnosis in the EHR. Prescriptions (e.g., ACEI/ARB and NSAIDs) were defined by relevant RxNorm codes without discontinuation dates.

Table 3.

Summary of Primary Analyses

| CKD CQM | Control group | Intervention group | Difference in 18-month change Mean (CI) |

p value‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group at baseline Mean ± SD (N¶) |

Control group at 18 months Mean ± SD (N¶) |

Absolute change Mean ± SD |

p value† | Intervention group at baseline Mean ± SD (N¶) |

Intervention group at 18 months Mean ± SD (N¶) |

Absolute change Mean ± SD |

p value† | |||

| Screening for albuminuria in pts at risk for CKD (DM and/or HTN) in the past year (excluding patients with CKD) | 58.6% ± 18.1% (17,434) | 56.0% ± 18.5% (16,454) | - 2.6% ± 5.2% | 0.24 | 44.4% ± 21.4% (17,229) | 66.5% ± 15.1% (15,388) | 22.1% ± 13.6% | < 0.0001 | 25.8% (19.3 to 32.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| Monitoring for albuminuria in pts with CKD in the past year (excluding A3 albuminuria and pts with ESRD) | 70.3% ± 13.4% (4446) | 68.3% ± 14.2% (5440) | - 2.0% ± 11.7% | 0.036 | 55.0% ± 20.3% (3572) | 75.8% ± 13.3% (4127) | 20.8% ± 12.3% | 0.26 | 22.3% (15.1 to 30.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR monitoring in patients with stage 3A–4 CKD in the past 6 months | 68.1% ± 16.2% (3287) | 69.3% ± 14.8% (3827) | 1.2% ± 10.2% | 0.29 | 71.7% ± 11.4% (2997) | 73.0% ± 12.2% (3079) | 1.2% ± 4.2% | 0.67 | − 2.0% (− 10.2 to 6.3%) | 0.64 |

| Hemoglobin monitoring in pts with stage 3B–5 CKD in the past year | 84.5% ± 13.8% (1275) | 78.4% ± 14.0% (1409) | - 6.1% ± 15.0% | 0.31 | 77.9% ± 19.1% (1012) | 80.2% ± 13.7% (998) | 2.4% ± 7.6% | 0.96 | 3.9% (− 7.0 to 14.8%) | 0.49 |

| Most recent blood pressure < 140/90 in pts with CKD (excluding A3 albuminuria) | 66.5% ± 15.5% (4540) | 66.3% ± 12.4% (5520) | - 0.2% ± 6.2% | 0.84 | 78.2% ± 8.6% (3613) | 80.3% ± 7.8% (4161) | 2.2% ± 8.1% | 0.14 | 2.8% (− 3.4 to 9.0%) | 0.38 |

| Most recent blood pressure < 130/80 in pts with CKD and A3 albuminuria | 31.0% ± 16.7% (431) | 26.8% ± 17.0% (588) | - 4.2% ± 5.6% | 0.86 | 27.8% ± 23.1% (184) | 28.5% ± 14.2% (300) | 0.7% ± 26.7% | 0.57 | 2.4% (− 15.6 to 20.4%) | 0.79 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB in pts with HTN and A3 albuminuria | 71.5% ± 28.1% (366) | 72.7% ± 13.8% (508) | 1.3% ± 24.8% | 0.91 | 77.5% ± 20.7% (167) | 84.0% ± 15.1% (235) | 6.5% ± 14.7% | 0.33 | 5.7% (− 8.9 to 20.3%) | 0.44 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB in pts with HTN and A2 albuminuria | 79.5% ± 9.4% (1263) | 76.9% ± 10.8% (1874) | - 2.6% ± 6.1% | 0.38 | 74.7% ± 5.7% (795) | 75.0% ± 7.9% (1242) | 0.3% ± 8.3% | 0.88 | 3.0% (− 5.0 to 10.9%) | 0.47 |

| Hemoglobin A1c measured in past year and ≤ 7% in pts with CKD and DM | 43.0% ± 9.4% (1672) | 42.2% ± 7.4% (2061) | - 0.8% ± 5.5% | 0.89 | 44.1% ± 7.2% (1062) | 48.2% ± 8.1% (1119) | 4.2% ± 6.5% | 0.52 | 1.4% (− 6.6 to 9.5%) | 0.73 |

| Rx for statin for pts 50 and over meeting criteria for CKD or pts 18–49 with CKD and CAD, DM, and CVD or 10-year ASCVD > 10% (excluding pts with ESRD) | 58.7% ± 11.7% (4579) | 63.1% ± 11.9% (5632) | 4.4% ± 7.3% | 0.08 | 60.1% ± 10.6% (3681) | 66.4% ± 10.7% (4284) | 6.3% ± 6.8% | 0.020* | 1.5% (− 5.9 to 8.9%) | 0.09 |

| Avoidance of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors in pts with CKD | 95.6% ± 2.8% (4971) | 85.5% ± 5.6% (6108) | - 10.1% ± 4.5% | < 0.0001 | 96.9% ± 2.2% (3797) | 91.9% ± 4.3% (4461) | − 5.1% ± 3.5% | < 0.0001* | 5.0% (2.6 to 7.5%) | < 0.0001 |

¶Ns represent the total number of patients eligible for the measure at that time point

†Used to assess within-group change from baseline to month 18

‡Used to assess whether the 18-month change within the intervention group differed from the 18-month change within the control group

*p < 0.5

Randomization

Ten practices were randomized to a control group and 11 to an intervention group using a constrained randomization process that ensured balance on 2 factors: the number of patients eligible for any CKD CQM and a baseline performance metric based on the set of CKD CQMs.39 This baseline performance metric was constructed by ranking each practice relative to one another on each CQM and then summing the ranks across CQMs for each practice.

Intervention

Practices in both the intervention and control groups were asked to submit EHR data at least quarterly and as frequently as monthly. The research team subsequently used this data to generate CKD CQM performance reports which the practice could then view and download via a secure web-based portal. These reports included practice-level longitudinal reports, using statistical process control methodology, on the set of CKD CQMs. For each measure, the reports also included the median PPRNet practice performance and the achievable benchmark of care, an empirically derived measure of attainable, excellent performance, approximating the 90th percentile performance accounting for unequal eligible patients among practices.40 Provider-level performance on each CQM was provided within an interactive Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, including all patients not meeting criteria for each CKD CQM. In addition, the reports contained a patient registry that included all patients with CKD, DM, or HTN in the practice along with relevant patient data (e.g., most recent blood pressure, eGFR, date of last ACEI/ARB prescription). Patients with CKD were stratified by “risk” for CKD progression (e.g., moderately increased risk, high risk, very high risk) using the KDIGO nomenclature for prognosis of CKD based on eGFR stage (from G1/normal when eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 to G5/kidney failure when eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) and albuminuria stage (from A1/normal when albumin-to-creatinine ratio < 30 mg/g to A3/severely increased when albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 300 mg/g).19

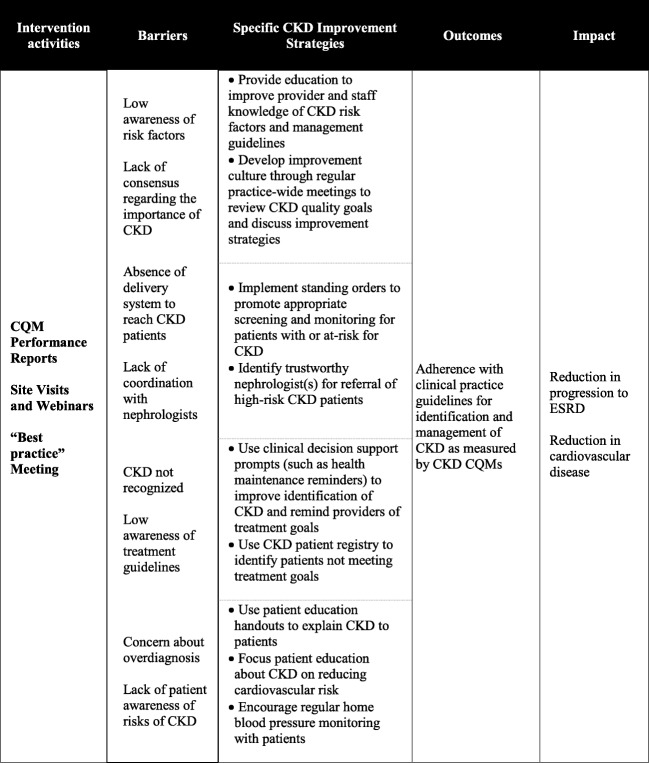

The logic model for our intervention is presented in Figure 1. As shown in the first column, in addition to receiving CKD CQM reports, intervention practices hosted an initial on-site visit and two follow-up webinars, and sent at least two representatives to an in-person meeting to share “best practices.” These activities were intended to promote implementation of specific CKD improvement strategies (3rd column, Fig. 1) derived from prior PPRNet research,41–45 adapted to overcome known barriers (2nd column, Fig. 1)5, 24–31, 46 and reflect key factors shown to enable optimal CKD care.47

Figure 1.

Translating CKD research into practice logic model.

Introductory on-site visits of 2-h duration to all intervention practices occurred during the first 3 months of the intervention. Site visits were led by two members of the research team (CBL, SMO) and attended by all clinicians and clinical staff at each practice. The research team introduced the study and provided academic detailing about the KDIGO guidelines for CKD identification and staging, monitoring, and management. The research team then presented baseline practice performance on the set of CKD CQMs and recommended specific improvement strategies (3rd column, Fig. 1) to improve performance. The research team highlighted the use of CKD CQM reports and registries to frame discussions on current approaches to care and specific opportunities for improvement. Practices were asked to commit to improvement strategies that were directly linked to their performance and considered feasible to implement in the context of their individual practices.

The site visit was followed by two follow-up webinars with the clinicians and clinical staff at each intervention practice; the first was held in spring 2017 and the second in the winter of 2018. During these webinars, the research team reviewed the practice’s performance on the set of CQMs and discussed potential improvement strategies. Webinars were tailored to the needs of each practice and included, for example, discussion about how practices could prioritize patients for outreach based on review of the practice’s CKD registry or role-play activities to educate providers and staff how to better explain the importance of statins to patients. The research team also followed up with each practice’s representatives quarterly via email to follow up on the specific improvement plans and help overcome any barriers.

A 1-day meeting to share “best practices” was held in Charleston, SC, in August 2017. Practice representatives (a clinician and a clinical staff member) were invited to this meeting. The research team facilitated discussions on the overall successes and challenges in getting practices to CKD CQM benchmarks and provided specific recommendations for achieving better blood pressure control, implementing home blood pressure monitoring, engaging patients to start taking statins, and providing alternatives to NSAIDs in patients with CKD. Each practice’s representatives discussed their practice’s successes related to the project, described barriers they had overcome, and discussed ongoing struggles. After hearing presentations from all practices, each practice then made additional plans for improving performance on CKD CQMs.

Statistical Analyses

The primary analyses assessed changes over time in performance on each CKD CQM over the 18-month study. Each CQM was reported on the practice level as a percentage on a monthly basis. All CQMs at the patient level were dichotomous in nature, with patients either meeting criteria or not. To evaluate the impact of the project over time, repeated measures analyses, based on generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) for longitudinal data, were used to assess whether or not there were significant improvements over time in each of the individual practice-level CKD CQMs. The GLMMs included random practice effects to account for clustering and an autoregressive error structure to account for repeated measurements on patients over time.

The study was designed to have sufficient (> 80%) statistical power for the primary outcome measures. This sample size calculation was based upon a number of assumptions, including 2-sided hypothesis testing, with an alpha level of 0.05. We also assumed that performance on CKD CQMs among eligible patients would improve to the achievable benchmark of care40 by the end of the study in intervention practices, with control group practices anticipated to remain relatively constant during the study.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analyses

We recorded detailed field notes during practice site visits, webinars, and the “best practice” meeting to describe practices’ plans for adopting CKD improvement strategies and their progress on fulfilling these plans, along with reported barriers and facilitators. These notes were reviewed by three research team members (CL, AW, LN) to catalog the extent to which each practice adopted the CKD improvement strategies. We confirmed our findings with each practice as a member check to ensure validity.

RESULTS

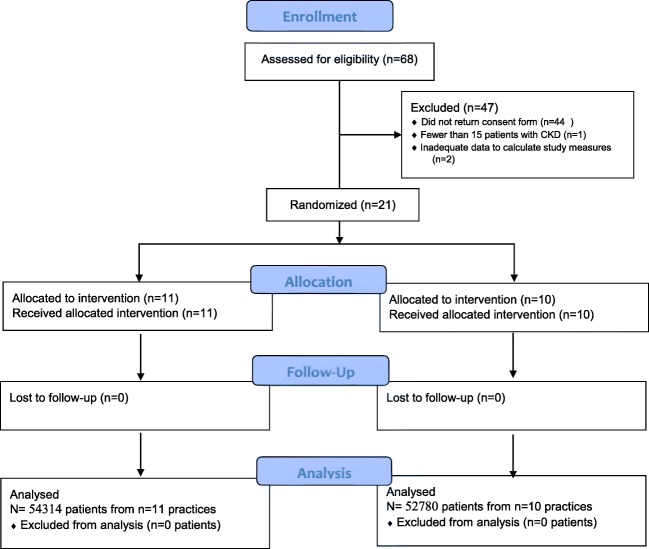

Figure 2 displays the CONSORT flow diagram for our study. Twenty-four practices returned participation agreements; 2 practices were subsequently excluded due to incomplete EHR data and one practice was excluded due to fewer than 15 patients with CKD. The remaining twenty-one practices were located in 13 US states and represented 71 physicians and 41 midlevel providers. Nearly all practices were independently owned; most practices were located in urban counties. Characteristics of the study practices are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics of the 107,094 patients considered active during the study, and who did not die or otherwise become inactive during the study period, are summarized in Table 2. The mean age, gender, and prevalence of study conditions (DM, HTN, CKD) were similar in the intervention and control groups. There were differences in the proportion of patients with varying races in the intervention compared with the control group, with more Black and Hispanic patients represented in the control group.

Figure 2.

Consort study diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Practices

| Intervention (n = 11) | Control (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic region | ||

| North | 4 (36.4%) | 0 |

| South | 5 (45.4%) | 7 (70.0%) |

| Midwest | 0 | 2 (20.0%) |

| West | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| Number of providers | ||

| 1 or 2 | 7 (63.6%) | 6 (60.0%) |

| 3 or 4 | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| ≥ 5 | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (30.0%) |

| Specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Family medicine | 9 (81.8%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Practice model | ||

| Independent | 11 (100%) | 9 (90.0%) |

| Community health care center | 0 | 1 (10.0%) |

| Urban vs. rural county | ||

| Urban | 10 (90.9%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Rural | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (20.0%) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Within Study Practices

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n = 54,314) | Control (n = 52,780) | p value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) years | 47.4 (21.2) | 46.7 (21.5) | 0.79 |

| Sex: % male | 44% | 41% | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity | < 0.0001 | ||

| White | 82.1% | 60.6% | |

| Black | 2.2% | 15.9% | |

| Asian | 1.6% | 2.5% | |

| Hispanic | 8.0% | 13.8% | |

| Other | 1.4% | 3.0% | |

| Unknown | 4.6% | 4.2% | |

| Study conditions | |||

| CKD | 7.0% | 9.5% | 0.64 |

| DM | 12.4% | 15.6% | 0.22 |

| HTN | 36.1% | 38.4% | 0.31 |

†p values were derived from mixed-effects models, including random practice effects to account for clustering

All 11 intervention practices hosted an initial on-site visit and two follow-up webinars. Representatives from 10 out of 11 practices attended the 1-day “best practice” meeting; nine of these practices sent both a provider and a clinical staff member, one practice sent an office manager and a clinical staff member, and one practice sent only an office manager. Intervention practices submitted EHR data for generation of CKD CQM reports from 8 to 17 times during the intervention period, and control practices submitted EHR data for generation of CKD CQM reports from 7 to 16 times during the intervention period.

Table 3 presents both baseline and final (18 months) performance for each CKD CQM in the intervention and control practices. There were statistically significant greater improvements in intervention practices compared with control practices for annual screening for albuminuria in patients with DM or HTN (absolute change 22.1% in the intervention group vs. − 2.6% in the control group, p < 0.0001) and annual monitoring for albuminuria in patients with CKD (absolute change 20.8% in the intervention group vs. − 2.0% in the control group, p < 0.0001). While performance on avoidance of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors in patients with CKD worsened in both control and intervention practices, the decline was statistically less in intervention practices compared with control practices (absolute change − 5.1% in the intervention group vs. − 10.1% in the control group, p < 0.0001). There was a trend toward improvement in the use of statins in patients with CKD in the control group and a significant improvement in the use of statins in patients with CKD in the intervention group, yet there was no significant difference when comparing control and intervention practices. There were no other significant changes between intervention and control practices.

There was considerable variation in the extent to which practices in the intervention group adopted the set of CKD improvement strategies. Five practices held at least quarterly practice-wide meetings to discuss CKD quality goals. All practices implemented EHR-based reminders for urine albumin screening in patients at risk for or with CKD, and 10 practices implemented standing orders for clinical staff members to collect urine for albumin testing. Only 4 practices implemented EHR-based reminders for eGFR and hemoglobin testing. Seven practices reported having a trustworthy relationship with a nephrologist(s). Ten practices reported at least occasionally reviewing the CKD patient registry and performing outreach to patients not meeting treatment goals, although only six of these practices reported reviewing the registry on a monthly basis. Nine practices reported using at least some patient education handouts. Some providers in ten practices reported focusing their discussion about CKD with patients on cardiovascular risk. Ten practices encouraged patients to do home blood pressure monitoring. Commonly reported barriers to full adoption of improvement strategies included competing obligations and additional pressures on the practice preventing regular use of the registries and practice-wide meetings, technical difficulties with implementing EHR alerts and extracting EHR data for CQM reports, differing provider views on how to discuss treatment options (e.g., statin therapy) with patients, and co-managing patients with specialists who did not provide adequate communication and/or disagreed with treatment goals.

DISCUSSION

In this study, implementation of a primary care practice improvement model designed to improve CKD identification and management resulted in improved performance on 3 CKD CQMs compared with control practices receiving only CQM reports during an 18-month intervention. The intervention resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of patients either at risk for or with CKD who received testing for urine albuminuria compared with control practices. This may have resulted from adoption of EHR-based reminders for this test along with standing orders for clinical staff to collect in-office urine specimens. Because albuminuria is a major prognostic risk factor for cardiovascular disease, progression of renal disease, and death, this intervention resulted in the identification of hundreds of patients with CKD who could benefit from additional risk factor modification such as blood pressure control, glycemic control, ACEI/ARB use, and statin use.

In addition, while both control and intervention practices used more NSAIDs in patients with CKD during the study time period, a trend which can likely be attributed to increased public health efforts to combat opioid misuse, providers in the intervention group avoided prescribing NSAIDs in CKD more so than those in the control group over the18-month intervention. This fact demonstrates that intervention strategies such as provider/staff education, use of patient registries to identify patients on NSAIDS, and patient education can reduce NSAID use in patients with CKD, thereby potentially reducing progression of CKD in these patients.18

The intervention did not result in significant improvements on the eight other CQMs. The qualitative evaluation suggests potential reasons for the intervention’s failure to result in significant improvement on other measures. While urine albumin testing could be quickly operationalized in the office by implementation of EHR-based reminders and standing orders for clinical staff, achieving improved performance on other process measures, such as prescriptions for ACEI/ARB or statins, required additional actions by providers. No improvements in outcome measures blood pressure and glycemic control outcomes were seen. Several of the barriers reported by practices, such as competing obligations and lack of coordination with other specialists who might co-manage patients with CKD, may have limited improvement. More frequent “best practice” meetings and/or additional on-site visits may have provided opportunities for practices, especially larger groups or those with new providers and staff, to better engage with the intervention and overcome barriers to implementing improvement strategies.47 In addition, the relatively short 18-month time frame of the intervention may not have been provided sufficient time to demonstrate improvements on these measures, particularly as more patients were identified as having CKD through increased urine albumin testing and subsequently became eligible for additional CKD CQMs.

This study’s results are consistent with a prior demonstration study conducted by this team48 to assess whether clinical decision support tools could improve identification and management of CKD. In that study, testing for albuminuria in patients at risk for and with CKD increased by 25 to 30% over 2 years in participating practices, with no other significant changes in other measures. Similarly, in a pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial comparing clinical decision support alone with clinical decision support with practice facilitation in improving outcomes for patients with CKD, there was significant improvement in hemoglobin A1c over 24 months between control and intervention patients. However, there was no significant difference in change in blood pressure, avoidance of NSAIDS, or use of ACEI/ARB.49

There are several important limitations of this study. The study lacked a pure control group because all practices received CKD CQM reports and registries. We did not assess adoption of improvement strategies in the control practices. Because all practices volunteered to participate in this study, the findings may not generalize to all primary care practices. Participating practices were asked to consider implementing the CKD improvement strategies but were not required to do so, and subsequently these strategies were variably adopted by practices. Therefore, our ability to assess the efficacy of the full set of improvement strategies was limited. However, four practices who fully adopted the set of strategies appeared to achieve the greatest improvements in performance on the set of CKD CQMs. Finally, we did not assess costs associated with implementing this intervention. However, screening for CKD in at-risk patients with diabetes and/or hypertension is suggested to be cost-effective given its ability to delay or prevent the cardiovascular and renal complications.50, 51 Moreover, we encouraged practices to adopt improvement strategies to more efficiently utilize and empower existing staff; we did not require the practice to commit additional personnel or resources to our intervention.

Despite these limitations, this study confirmed our prior findings that screening for and monitoring CKD by urine albumin testing can quickly be adopted in primary care practices by implementing EHR-based reminders along with standing orders operationalized by clinical staff. Furthermore, NSAID use in patients with CKD may be limited through a combination of provider education, registry review, and patient education. However, achievement of other measures of CKD management likely requires a more robust and longer intervention designed to improve care coordination and overcome competing obligations to ensure complete adoption of evidence-based improvement strategies.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R18DK110962.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Wessell reports that she is the Clinical Director of the DARTNet Institute Patient Safety Organization, which has adopted similar medication safety measures for patients with chronic kidney disease as reported in this paper. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Steven M. Ornstein and Ruth G. Jenkins retired from the Department of Family Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, USA after the conduct of the study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B. US Renal Data System 2014 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis.66(1 (suppl 2)):S1-S306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wouters OJ, O’Donoghue DJ, Ritchie J, Kanavos PG, Narva AS. Early chronic kidney disease: diagnosis, management and models of care. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(8):491–502. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster MC, Rawlings AM, Marrett E, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor burden, treatment, and control among adults with chronic kidney disease in the United States. Am Heart J. 2013;166(1):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox CH, Brooks A, Zayas LE, McClellan W, Murray B. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and practice patterns in the treatment of chronic kidney disease: an Upstate New York Practice-based Research Network (UNYNET) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):54–61. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philipneri MD, Rocca Rey LA, Schnitzler MA, et al. Delivery patterns of recommended chronic kidney disease care in clinical practice: administrative claims-based analysis and systematic literature review. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12(1):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahinian VB, Saran R. The role of primary care in the management of the chronic kidney disease population. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(3):246–253. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong PE, Curhan GC. Screening, monitoring, and treatment of albuminuria: Public health perspectives. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(8):2120–2126. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karalliedde J, Viberti G. Microalbuminuria and cardiovascular risk. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(10):986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Craig JC, et al. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD007784. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007784.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists C. Ninomiya T, Perkovic V, et al. Blood pressure lowering and major cardiovascular events in people with and without chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Bmj. 2013;347:f5680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holtkamp FA, de Zeeuw D, de Graeff PA, et al. Albuminuria and blood pressure, independent targets for cardioprotective therapy in patients with diabetes and nephropathy: a post hoc analysis of the combined RENAAL and IDNT trials. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(12):1493–1499. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(2):73–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarnak MJ, Greene T, Wang X, et al. The effect of a lower target blood pressure on the progression of kidney disease: long-term follow-up of the modification of diet in renal disease study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(5):342–351. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shurraw S, Hemmelgarn B, Lin M, et al. Association between glycemic control and adverse outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(21):1920–1927. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. [PubMed]

- 18.Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, et al. NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2007;120(3):280 e281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2013(3):19–62. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(5):337–414.

- 21.Tuot DS, Powe NR. Chronic kidney disease in primary care: an opportunity for generalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):356–358. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1650-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litvin CB, Nietert PJ, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Ornstein SM. Recognition and management of CKD in primary care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(4):646–647. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen AS, Forman JP, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Denker BM, Sequist TD. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):386–392. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Israni RK, Shea JA, Joffe MM, Feldman HI. Physician characteristics and knowledge of CKD management. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(2):238–247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.01.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lea JP, McClellan WM, Melcher C, Gladstone E, Hostetter T. CKD risk factors reported by primary care physicians: do guidelines make a difference? Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(1):72–77. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plantinga LC, Tuot DS, Powe NR. Awareness of chronic kidney disease among patients and providers. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(3):225–236. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuot DS, Plantinga LC, Hsu CY, Powe NR. Is awareness of chronic kidney disease associated with evidence-based guideline-concordant outcomes? Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(2):191–197. doi: 10.1159/000335935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greer RC, Cooper LA, Crews DC, Powe NR, Boulware LE. Quality of patient-physician discussions about CKD in primary care: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(4):583–591. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rettig RA, Norris K, Nissenson AR. Chronic kidney disease in the United States: a public policy imperative. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1902–1910. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamantidis CJ, Powe NR, Jaar BG, Greer RC, Troll MU, Boulware LE. Primary care-specialist collaboration in the care of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(2):334–343. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06240710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haley WE, Beckrich AL, Sayre J, et al. Improving care coordination between nephrology and primary care: a quality improvement initiative using the renal physicians association toolkit. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(1):67–79. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):570–581. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berns JS, Ellison DH, Linas SL, Rosner MH. Training the next generation’s nephrology workforce. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Sep 5 2014;9(9):1639–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Brosius FC, 3rd, Hostetter TH, Kelepouris E, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease in patients with or at increased risk of cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease Council; the Councils on High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Epidemiology and Prevention; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group: Developed in Collaboration With the National Kidney Foundation. Hypertension. 2006;48(4):751–755. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Diabetes A 11. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S124–S138. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renal Physicians Association Urge Screening for those at Risk for Kidney Disease. 2013;Foundation NK https://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/nr/NKF-RPA-Urge-Screening-for-atRisk-KD. Accessed August 29, 2019.

- 38.Litvin CB, Ornstein SM. Quality indicators for primary care: an example for chronic kidney disease. J Ambulatory Care Manag. 2014;37(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, Nemeth LS, Ornstein SM. An application of a modified constrained randomization process to a practice-based cluster randomized trial to improve colorectal cancer screening. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(2):129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman NW, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, et al. Achievable benchmarks of care: the ABCs of benchmarking. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5(3):269–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemeth LS. Synthesizing Lessons Learned Within a Practice-Based Research Network (PPRNet). 26th Annual Conference of the Southern Nursing Research Society; Feb 25, 2012, 2012; New Orleans, LA.

- 42.Nemeth LS. Making Sense of Electronic Medical Record Adoption as Complex Interventions in Primary Health Care: Synthesizing Lessons Learned With Complex Interventions in a Research Network (PPRNet). Innovations for Health System Improvement: Balancing Costs, Quality and Equity; Annual CAHSPR Conference 2012; 2012; Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- 43.Nemeth LS, Nietert PJ, Ornstein SM. High performance in screening for colorectal cancer: a Practice Partner Research Network (PPRNet) case study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):141–146. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemeth LS, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Nietert PJ, Liszka HA, Ornstein SM. Strategies to accelerate translation of research into primary care within practices using electronic medical records. J Nurs Care Qual. 2007;22(4):343–349. doi: 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000290416.27393.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nemeth LS, Ornstein SM, Jenkins RG, Wessell AM, Nietert PJ. Implementing and evaluating electronic standing orders in primary care practice: a PPRNet study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):594–604. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greer RC, Powe NR, Jaar BG, Troll MU, Boulware LE. Effect of primary care physicians’ use of estimated glomerular filtration rate on the timing of their subspecialty referral decisions. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsang JY, Blakeman T, Hegarty J, Humphreys J, Harvey G. Understanding the implementation of interventions to improve the management of chronic kidney disease in primary care: a rapid realist review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:47. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Litvin CB, Hyer JM, Ornstein SM. Use of Clinical Decision Support to Improve Primary Care Identification and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(5):604–612. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.05.160020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carroll JK, Pulver G, Dickinson LM, et al. Effect of 2 Clinical Decision Support Strategies on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183377. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Komenda P, Ferguson TW, Macdonald K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):789–797. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoerger TJ, Wittenborn JS, Segel JE, et al. A health policy model of CKD: 1. Model construction, assumptions, and validation of health consequences. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):452–462. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]