Abstract

Background

As more health care organizations integrate social needs screening and navigation programs into clinical care delivery, the patient perspective is necessary to guide implementation and achieve patient-centered care.

Objectives

To examine patients’ perceptions of whether social needs affect health and attitudes toward healthcare system efforts to screen for and address social needs.

Research Design

Multi-site, self-administered survey to assess (1) patient perceptions of the health impact of commonly identified social needs; (2) experience of social needs; (3) degree of support for a health system addressing social needs, including which social needs should be screened for and intervened upon; and (4) attitudes toward a health system utilizing resources to address social needs. Analyses were conducted using multivariable logistic regression models with clinic site cluster adjustment.

Subjects

Adult patients at seven primary care clinics within a large, integrated health system in Southern California.

Main Measures

Survey measures of experience with, acceptability of, and attitudes toward clinical social determinants of health screening and navigation.

Key Results

A total of 1161 patients participated, representing a 79% response rate. Most respondents (69%) agreed that social needs impact health and agreed their health system should ask about social needs (85%) and help address social needs (88%). Patients with social needs in the last year were more likely to (1) agree social needs impact health (OR 10.2, p < 0.001), (2) support their health system asking patients about social needs (OR 3.7, p < 0.001), and (3) support addressing patient social needs (OR 3.5, p < 0.001). Differences by social need history, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education were found.

Conclusions

Most patients at a large integrated health system supported clinical social needs screening and intervention. Differences in attitudes by social need history, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education may indicate opportunities to develop more equitable, patient-centered approaches to addressing social needs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05588-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: social needs, social determinants of health, patient attitudes, patient Experience

INTRODUCTION

The strongest determinants of morbidity and mortality are social and behavioral factors; consequently, addressing these social determinants of health has been identified as a national priority.1–3 The term social needs has been used to encompass discrete and actionable basic needs stemming from the social determinants, including lack of food, housing, and transportation that healthcare systems are increasingly focusing on as a means to move care “upstream.”4, 5 The recognition that social determinants and their associated needs are strong drivers of population health has resulted in increased integration of social needs interventions into healthcare delivery.6, 7 As a result, health systems nationwide are exploring social needs screening and navigation to connect patients with community-based resources to resolve their social needs.8–12 Despite this interest in social needs programs for patients, very little published evidence exists on patients’ own attitudes toward such programs to guide implementation in a patient-centered manner.

To inform upstream care delivery, the patient perspective is necessary to guide program implementation, especially concerning patients’ acceptance of and attitudes toward such social needs programs. Some patients may welcome these new efforts while others may view them as intrusive, causing unforeseen challenges. Despite one published study examining parents’ and caregivers’ attitudes toward social needs screening in a pediatric inpatient setting,13 little is known regarding acceptability of social needs programs to patients themselves in ambulatory settings where social needs screening and referral often occurs.6 Also, there is little evidence on patients’ perceptions and attitudes about whether social needs affect health, whether healthcare systems should engage in efforts to address social needs, or whether patients of different demographic backgrounds and experiences with social needs may be more or less supportive of such efforts.

We conducted a multi-site, clinic-based survey study to understand adult patients’ perceptions of, experiences with, and attitudes toward social needs, screening, and navigation in a sample of insured patients in a large integrated health system. We explored acceptability of social needs programs by experience of a social need in the last year, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education level.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We surveyed patients 18 years of age or older in seven ambulatory and primary care family medicine or internal medicine clinics within Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), a large, vertically integrated healthcare system. Medical clinic sites invited to participate reflected the ethnic, geographic, and socioeconomic diversity of KPSC, and the sample makeup was demographically similar to the entire KPSC health system and the Southern California population.14, 15 Patients who did not speak or read English or Spanish were excluded.

Survey Administration

The self-administered surveys were distributed to patients at clinic reception areas after appointment check-in. Clerks were trained to use standardized scripts to convey study aims, emphasize confidentiality, and obtain consent. Upon request, they also provided patients with a frequently asked questions document for further details. Paper and electronic (tablet) collection options were offered with most patients utilizing paper. Surveys were completed during patients’ wait times. The survey typically took 7 to 10 min to complete.

Survey Development and Structure

In the absence of previously validated question items from peer-reviewed surveys of adult patients on their experiences and attitudes toward social needs screening and intervention, our study developed survey items through an iterative process incorporating input from patients, clinicians, and experts (in the field) in the testing and refinement of our survey constructs and questions. The survey domains and question language were based on content from facilitator guides developed for and themes that emerged from qualitative focus groups and key informant interviews with 46 patients and 40 clinician leaders in KPSC.16

Themes from the focus groups and key informant interviews fell into domains of patient experiences with social needs, patient attitudes toward social needs screening and intervention, and patient support for health system investment in social needs programs. These became the main constructs for our survey, and language from the focus group prompts were adapted to examine these domains of inquiry in the survey. Question items were refined to consensus by the authors and shared for feedback on validity with a network of experts in social needs interventions external to the study team. Reading level for the survey questions was below 6th grade level, and the survey was translated into Spanish. Initial responses to the paper versions of the survey were reviewed by authors to identify any patient misunderstanding of the questions, consistent skip patterns, common omissions, or patterns of open-ended responses, but no issues relevant to the survey construction or question item validity were found.

Measure Development

The scope of the survey was designed to address the study aims to assess patients’ (1) prior experience with social needs; (2) perceptions of how social needs affect health; (3) perceptions of their healthcare system’s (Kaiser Permanente’s) role in addressing social determinants of health, including which social needs should be screened and addressed; and (4) attitudes toward health system investment in addressing social needs.

Survey Measures

Our final survey included eight multiple choice items, including demographic questions, and one, three-part Likert scale item. The first questions asked patients whether they had experienced any of a series of social needs in the last year. Next, patients were prompted to indicate whether specific needs impacted health. Then, patients were asked which, if any, of the aforementioned social needs should be screened for and addressed within their healthcare setting. Participants were then asked a series of questions about their degree of support on a 5-point Likert scale for their health system addressing social needs to improve care, committing part of its budgetary resources to address social needs, and whether they supported such programs if it meant having higher healthcare costs. Self-reports of patients’ demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education level were collected. The race and ethnicity categories are consistent with the federal Office of Management and Budget standard race and ethnicity categories, combined into a single question found to improve response rates as tested by the Census Bureau.17 The full survey text is available in Appendix A.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the sample overall were calculated. We used chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests, t tests (for two group tests of means), and tests of proportions (for two group tests of proportions) to examine differences in patient responses by participant characteristics, including experience of a social need in the last year, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education level. We dichotomized responses (agree and strongly agree versus neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree) for analyses of questions answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Multivariable logistic regression models with clinic site clustering were used to determine the odds of patient perceptions that any social need(s) influenced health, that the health system should screen for social needs, and that the health system should intervene and invest in addressing social needs. Covariates included experience of a social need in the last year, gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education level. Alternative age category specifications by decade of life did not alter results. Unadjusted comparison results can be found in Appendix B. Partially completed surveys were utilized in the analysis for items completed. The KPSC institutional review board approved the study as exempt. All analyses were carried out using STATA 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

EXPERIENCE WITH SOCIAL NEEDS, GENDER, AGE, RACE/ETHNICITY, EDUCATION LEVEL

Results

Of the 1470 patients approached, 79.0% participated in the survey. Item completion ranged from 95 to 81% (Tables 1 and 2). Among respondents providing demographic information, 66% (674) were female, 79% (643) were 60 years or younger, 70% (681) identified as non-White race, 50% (495) identified as Hispanic, and 33% (320) had a high school degree or less, similar to the population of clinic-going patients in KPSC.18, 19 Seventeen percent (187) of respondents reported having at least one social need in the past year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey Participant Characteristics and Unadjusted Comparisons by Responses to Key Survey Questions

| Characteristics | % (N) | Experienced social need(s) in last year (N = 1097 responses) | P value | Agreed social needs impact health (N = 1002 responses) | P value | Agreed health system should ask about one or more social needs (N = 1062 responses) | P value | Agreed health system should help with one or more social needs (N = 1074 responses) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | 100.0% (1161) | 17.0% (187) | 69.0% (694) | 85.0% (900) | 88.0% (949) | ||||

| Social needs status (N = 1097 responses) | |||||||||

| No social needs in last year | 83.0% (910) | 63.0% (517) | < 0.001 | 68.5% (593) | < 0.001 | 65.0% (568) | < 0.001 | ||

| At least one social need in last year | 17.0% (187) | 91.0% (143) | 87.0% (140) | 84.0% (135) | |||||

| Gender (N = 1012 responses) | |||||||||

| Male | 33.0% (338) | 17.1% (56) | 0.971 | 69.9% (202) | 0.866 | 80.3% (252) | 0.032 | 84.2% (266) | 0.016 |

| Female | 66.0% (674) | 17.5% (111) | 68.5% (402) | 86.7% (534) | 90.5% (564) | ||||

| Age (N = 1010 responses) | |||||||||

| 18–30 | 16.0% (164) | 19.1% (31) | 0.242 | 63.5% (94) | 0.543 | 86.9% (139) | 0.307 | 92.6% (150) | 0.307 |

| 31–40 | 15.0% (156) | 13.3% (20) | 71.2% (99) | 84.5% (125) | 88.8% (135) | ||||

| 41–50 | 17.0% (177) | 15.8% (26) | 71.5% (108) | 87.0% (141) | 89.8% (149) | ||||

| 51–60 | 14.0% (146) | 17.1% (24) | 72.0% (85) | 82.7% (110) | 89.4% (118) | ||||

| 61–70 | 20.0% (202) | 22.0% (42) | 70.0% (126) | 86.1% (155) | 86.3% (157) | ||||

| 70 and above | 16.0% (165) | 13.6% (21) | 65.9% (91) | 78.6% (114) | 84.7% (122) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (N = 974 responses) | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 50.0% (495) | 17.0% (81) | 0.023 | 60.0% (247) | < 0.001 | 69.0% (302) | 0.011 | 73.0% (323) | 0.003 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 30.0% (293) | 13.0% (37) | 77.0% (207) | 72.0% (202) | 64.0% (178) | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 9.0% (90) | 8.0% (7) | 64.0% (50) | 69.0% (59) | 58.0% (50) | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 6.0% (60) | 16.0% (9) | 69.0% (35) | 76.0% (44) | 73.0% (43) | ||||

| Mixed race and other | 3.0% (36) | 27.0% (12) | 75.0% (30) | 93.0% (39) | 84.0% (37) | ||||

| Education level (N = 985 responses) | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 13.0% (127) | 27.0% (31) | 0.001 | 60.8% (59) | 0.001 | 85.0% (85) | < 0.001 | 87.3% (89) | 0.201 |

| High school grad or GED | 20.0% (193) | 21.7% (39) | 65.4% (102) | 74.1% (129) | 86.2% (156) | ||||

| Some college or vocational school | 36.0% (350) | 13.8% (47) | 66.0% (208) | 85.4% (281) | 87.8% (288) | ||||

| Completed college or higher | 32.0% (315) | 13.9% (42) | 78.4% (225) | 89.7% (271) | 91.8% (281) | ||||

P values are for chi-square tests of difference in proportions across categories of patient characteristics displayed in the adjacent column and section. Results are displayed as counts (percentages) throughout table

Table 2.

Patient’s Attitudes and Perceptions of Social Needs’ Impact on Health and Health System’s Role for Addressing Social Needs, Adjusted Multivariable Logistic Regression Results

| Outcome | Agreed social needs impact health (N = 1002 responses) | Agreed health system should ask about one or more social needs (N = 1062 responses) | Agreed health system should help with one or more social needs (N = 1074 responses) | Agreed health system should use social needs information (N = 1027 responses) | Agreed health system should use financial resources from its budget to address social needs (N = 960 responses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) | |||||

| No social need in the last year | Reference | ||||

| Social needs in the last year | 10.2 (5.4–19.2)*** | 3.7 (2.0–6.9)*** | 3.6 (2.2–5.8)*** | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | 1.6 (0.7–3.4) |

| Male | Reference | ||||

| Female | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9)* | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)*** | 1.7 (1.5–2.0)*** | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) |

| Under 40 years old | Reference | ||||

| 41–60 years old | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1)* |

| 61 or more years old | 0.7 (0.6–0.9)** | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) |

| White, non-Hispanic | Reference | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.4 (0.3–0.5)*** | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 2.3 (1.7–3.2)*** | 1.8 (1.4–2.3)*** |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.5 (0.3–0.9)* | 1.4 (0.6–3.1) | 1.3 (0.6–2.7) | 1.8 (1.1–3.0)* | 2.4 (1.5–3.7)*** |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.4 (0.3–0.6)*** | 0.7 (0.6–0.9)** | 0.6 (0.5–0.9)** | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0)** |

| Less than high school | Reference | ||||

| High school graduate or GED | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.7 (0.5–1.2) |

| Some college or vocational school | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.7 (0.5–0.8)*** | 0.5 (0.4–.6)*** |

| Completed college or Higher | 2.9 (1.4–6.2)** | 1.4 (1.0–2.1) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 1.7 (1.4–3.1)* | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

Results shown are adjusted odds ratios from five separate multivariable logistic regression models, one for each of the outcomes listed at the top of each of the five right-most columns. Italicized font indicates statistical significance; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

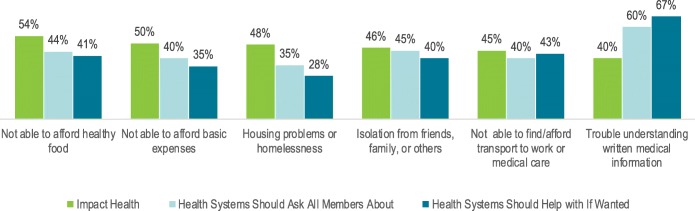

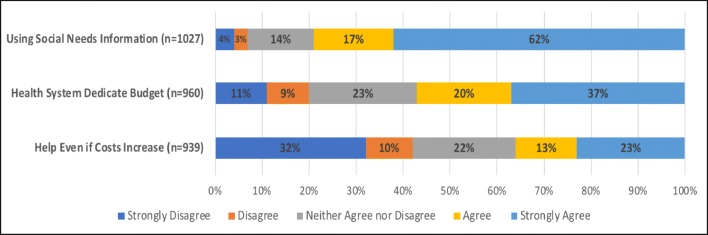

Most participants (69.0%, 694) responded that one or more social needs have an impact on health. Patients were most likely to think the inability to afford healthy food (54.0%) and basic expenses (50.0%) affected health. Seventy-nine percent (812) agreed or strongly agreed that their health system should use social needs information to improve care for patients (Fig. 1). Eighty-five percent (900) were in favor of the health system asking patients about one or more social need, and 88.0% (949) were in favor of their health system intervening to help address one or more social needs (Table 1). A majority (57.0%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed the health care system should dedicate part of its budget to help patients with their social needs, but a minority (36.0%) of respondents supported these efforts if social needs interventions increased their individual healthcare costs (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Patients’ perceptions of health systems’ role in addressing specific social needs, overall sample

Figure 2.

Patients’ support for health systems’ role in addressing social needs, overall sample

Results by Patient Characteristics and Social Needs Experiences

The sections below present study findings organized by participant characteristics, including experience of social needs in the last year.

Patients with Recent Social Needs

Patients who had experienced any social need in the last year were over 10 times as likely to agree that social needs have an impact on health (10.2 OR; p < 0.001) compared to those with no reported social needs in adjusted models. These participants were over three times as likely to agree that their health system should ask about (3.7 OR; p < 0.001) and help address social needs (3.6 OR; p < 0.001). However, there was not a statistically significant increase in likelihood of patients with recent social needs supporting their health system using social needs information, dedicating part of its budget, or using its dollars to address social needs (Table 2).

Findings by Gender and Age

Participants who identified as female were more likely than males in multivariable logistic models to support the health system asking about and helping to address social needs (asking: 1.4 OR; p < 0.05; helping address: 1.7 OR; p < 0.001). Women were also more likely to support the health system using social needs information to improve care for patients (1.7 OR; p < 0.001). There was no significant increase in likelihood of women wanting their health system to use financial resources from its budget or increasing patients’ costs to address social needs. Participants who were 61 and older were less likely to believe that social needs have an effect on health than those 40 years or younger (0.7 OR; p < 0.01). Also, individuals between the ages 41–60 were more likely to agree that their health system should dedicate financial resources to address social needs compared to those 40 years or younger. However, there were no clear, significant patterns seen by participant age in terms of attitudes toward asking or screening for social needs, intervening to address social needs, using social needs information, or increasing costs to patients to address social needs (Table 2).

Findings by Patient Race and Ethnicity

Patients who identify as Hispanic (0.4 OR; p < 0.001), Asian/Pacific Islander (API) (0.4 OR; p < 0.001), and Black, non-Hispanic (0.5 OR; p < 0.05) were less likely to perceive that social needs have an impact on health than non-Hispanic White patients in the adjusted logistic regression model. Patients of API descent were less likely to agree that their health system should ask about or help address social needs (ask: 0.7 OR, p < 0.01; help address: 0.6 OR; p < 0.01). Patients who identified as Hispanic (2.3 OR; p < 0.001) and African American (1.8 OR; p < 0.05) were roughly two times more likely to support using social needs information. They, along with API patients, were also more likely to support their health system dedicating part of its budget to social needs interventions (Hispanic: 1.8 OR; p < 0.001; African Americans: 2.4 OR; p < 0.001; Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.5 OR; p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Findings by Education Level

Those who completed college were almost three times as likely to believe social needs impact health (2.9 OR; p < 0.01) in multivariable models. While no differences were seen by education level in terms of support for social needs screening or intervention, those with some college education but not a four-year degree were less likely to support their health system using social needs information to improve medical care (0.7 OR; p < 0.001) or dedicating parts of its budget to social needs interventions (0.5 OR; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In our study, most patients surveyed in a large integrated health system believed social needs have an impact on health and supported health systems asking about and addressing social needs. The results suggest that most patients see the connection between social needs and overall health even if they have not personally experienced a social need. Furthermore, most supported health system intervention to tackle patients’ social needs, even if it meant using financial resources from the health system budget. This finding indicates widespread support and desire from patients for their health system to both screen and develop interventions that address patient social needs. There was less support for addressing social needs if it resulted in an increase in costs to the patient. This suggests patients want health systems to address social needs through programs that are cost efficient.

Patient perceptions regarding whether the health system should intervene on social needs varied (Fig. 2). Implementation of social needs interventions may require patient education regarding the role health systems could play in addressing specific social domains and likely impact on health. Patients who had experienced recent social needs were especially aware of their health impact and strongly supportive of health systems asking about and intervening upon social needs. Although there is a small percentage of responders in this study who identified having a social need, it is important to note that social risk or social need status is not a static metric. A person can have a social need at any time. Therefore, it seems that as individuals experience social needs, they gain better understanding of the effect that social needs have on health and the potential role health systems can play in addressing social needs.

Some racial/ethnic minority patients in this study were less likely to perceive social needs impacting health compared to non-Hispanic White patients. Yet, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian/Pacific Islanders supported their health system dedicating part of its budget to advance social need efforts. Women were more likely to believe that the health system should ask, address, and use the social need information to improve care for patients despite the absence of a gender difference in rates of belief that social needs impact health. No clear patterns across survey items emerged regarding the relationships between age or education and support for social needs screening and intervention—though older patients and those with some college education but no degree appeared to be more opposed than younger patients and those with other levels of education, respectively. We found statistically significant associations between patients’ education and belief that social needs impact health but no such association with education and beliefs that the health system should intervene. We hypothesize that educated patients may expect other entities to address such needs.

Ultimately, our findings suggest that socially marginalized groups, such as those who have recent social needs, racial/ethnic minorities, and women, may be more likely to support social needs interventions in healthcare. The reasons for this could stem from having more experience with structural inequities that are the root cause of social needs.20–24 Although they less often reported that these social inequities affect individual health, women and racial/ethnic minorities recognized the importance of the health system surfacing and addressing these social needs in our study.

As health systems introduce social needs interventions in the care delivery setting, our study indicates there is a need to raise awareness of the linkage between health outcomes and social needs among patients generally. Patients may need more assistance understanding the rationale behind health systems actually intervening to address social needs. These nuances may be helpful as staff both develop language to introduce social interventions and create strategies to make these interventions acceptable and feasible for implementation in the healthcare setting. Additionally, implementers must also consider strategies for those who may be less receptive to screening and addressing social needs. Tactics focused on cultural competency will be essential for engaging socially marginalized groups less supportive of interventions focused on social needs.

LIMITATIONS

While the study included seven sites, this study was conducted among English- and Spanish-speaking, insured patients from ambulatory clinics in a single health system in California, which may limit generalizability. Narrowed translation may result in missing socially marginalized patients experiencing a social need in the past year. Yet, our study sample represents a diverse group of adult patients seen in a primary care clinic setting where many health systems deploy social needs screening and intervention. Study survey questions were not previously validated since a validated, published survey tool on this topic was not previously available. Item non-response could lead to some bias, but the participation rate minimizes that possibility. In assessing patient attitudes toward health system social needs programs and investment, our study captures the patients’ perspective by design but does not capture patients’ views, knowledge, or understanding of health system decisions regarding investment in social needs programs.

CONCLUSION

Most patients in primary care clinics from diverse backgrounds within an integrated health system recognize strong relationships between social needs and health. Most believe their health system should ask about social needs, help address social needs, and use social needs information to improve care for patients. Attitudes differ somewhat by race/ethnicity, gender, education, age, and prior experience of social needs, signaling the importance of developing patient-centered interventions and approaches that are equitably deployed.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 57 kb)

(DOCX 33 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients of Kaiser Permanente for helping us improve care through the use of information collected through our patient surveys. We also appreciate the time and dedication of the staff of the participating clinics. Lastly, we thank Jim Bellows, our project sponsor, and our project management team, Yi Hu, Roger Tang, Mia Griffin, and Lunarosa Peralta, for all of their help and support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Heiman HJ, Artiga S. “Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity - Issue Brief.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Disparities Policy, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 4 Nov. 2015, www.kff.org/report-section/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity-issue-brief/#endnote_link_168746-6.

- 2.Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1641–1642. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on the Recommended Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures for Electronic Health Records. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed]

- 4.Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Publ Health Rep. 2014;129:1_suppl2:19–31. 10.1177/00333549141291s206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Castrucci B, Auerbach J. Meeting Individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Affairs Blog. 2019 10.1377/hblog20190115.234942.

- 6.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities--addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb L, Colvin JD, Fleegler E, Hessler D, Garg A, Adler N. Evaluating the accountable health communities demonstration project. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):345–349. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3920-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlieb L, Ackerman S, Wing H, Manchanda R. Understanding Medicaid Managed Care Investments in Members’ Social Determinants of Health. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(4):302–308. doi: 10.1089/pop.2016.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkowitz SA, Terranova J, Hill C, Ajayi T, Linsky T, Tishler LW, DeWalt DA. Meal Delivery Programs Reduce the Use Of Costly Health Care In Dually Eligible Medicare And Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Affairs. 2018;37(4):535–42. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim S, Singh TP, Hall G, Walters S, Gould LH. Impact of a New York City supportive housing program on housing stability and preventable health care among homeless families. Health Serv Res. 2018. 10.1111/1475-6773.12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hunter SB, Harvey M, Briscombe B, Cefalu M. Evaluation of Housing for Health Permanent Supportive Housing Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2017

- 12.Shannon GR, Wilber KH, Allen D. Reductions in costly healthcare service utilization: Findings from the Care Advocate Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1102–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colvin JD, Bettenhausen JL, Anderson-Carpenter KD, Collie-Akers V, Chung PJ. Caregiver Opinion of In-Hospital Screening for Unmet Social Needs by Pediatric Residents. Acad Pediatr. 2012;16(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser Permanente Southern California Facilities and Resources. May 2019. Kaiser Permanente “Accountable Health Communities---Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11. 10.1056/nejmp1512532. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.California Health Interview Survey. AskCHIS, The California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) and the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Race, ethnicity, and educational attainment rates for Southern California counties, accessed Sept. 2019 at ask.chis.ucla.edu/AskCHIS/

- 16.Hamity CL, et al. Perceptions and Experience of Patients, Staff, and Clinicians with Social Needs Assessment. Permanente J. 2018. 10.7812/tpp/18-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Mathews K, Phelan J, Jones NA, Konya S, Marks R, Pratt BM, Coombs J, Bentley M. National Content Test: Race and Ethnicity Analysis Report. Suitland, MD: US Census Bureau. 2017; 2015. www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/programmanagement/final-analysis-reports/2015nct-race-ethnicity-analysis.pdf. Accessed Sept 2019.

- 18.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, Chao CR, Iyer RL, Smith N, Chen W, Jacobsen SJ. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Permanente J. 2012;16(3):37. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(2):147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradies Y, Truong M, Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):364–87. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2583-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer TM, Brondolo E, Brown P. Systemic racism moderates effects of provider racial biases on adherence to hypertension treatment for African Americans. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):35. doi: 10.1037/a0032777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1172–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert CH, Grande D, Schwartz JS, Liao K, Marcus N, Demeter MB, Shea JA. Prior experiences of racial discrimination and racial differences in health care system distrust. Med Care. 2013;51(2):144. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827310a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 57 kb)

(DOCX 33 kb)