Abstract

Introduction

Interhospital fragmentation of care occurs when patients are admitted to different, disconnected hospitals. It has been hypothesized that this type of care fragmentation decreases the quality of care received and increases hospital costs and healthcare utilization. This systematic review aims to synthesize the existing literature exploring the association between interhospital fragmentation of care and patient outcomes.

Methods

MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and the Science Citation Index were systematically searched for studies published up to April 30, 2018 reporting the association between interhospital fragmentation of care and patient outcomes. We included peer-reviewed observational studies conducted in adults that reported measures of association between interhospital care fragmentation and one or more of the following patient outcomes: mortality, hospital length of stay, cost, and subsequent hospital readmission.

Results

Seventy-nine full texts were reviewed and 22 met inclusion criteria. Nearly all studies defined fragmentation of care as a readmission to a different hospital than the patient was previously discharged from. The strongest association reported was that between a fragmented readmission and in-hospital or short-term mortality (adjusted odds ratio range 0.95–3.62). Over half of the studies reporting length-of-stay showed longer length of stay in fragmented readmissions. All three studies that investigated healthcare utilization suggested an association between fragmented care and odds of subsequent readmission. The study populations and exposures were too heterogenous to perform a meta-analysis.

Discussion

Our review suggests that fragmented hospital readmissions contribute to increased mortality, longer length-of-stay, and increased risk of readmission to the hospital.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05366-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: readmission, continuity of care, fragmentation of care, patient outcomes, systematic review

Introduction

Increasing national emphasis has been placed on high-value, high-quality patient care, with a focus on reducing hospital readmissions, cost, and waste. When patient care is divided among multiple organizations and providers, fragmentation of care occurs. Fragmentation of care in the outpatient setting has been associated with a range of negative patient outcomes, including increased morbidity,1, 2 more duplicate medications and more drug interactions,3, 4 redundant imaging tests,5 as well as more frequent admissions to the hospital.6–9 Interhospital fragmentation of care, when a patient is readmitted to a different hospital than the one they were previously discharged from, has not been widely studied, and its effects on patient outcomes are not well defined.

Among the few existing studies, interhospital care fragmentation has been reported to be associated with decreased patient satisfaction,10 longer length-of-stay,11–14 increased likelihood of discharge to a care facility,15 increased costs,16, 17 and increased mortality both in the hospital and following discharge from a fragmented readmission.13, 14, 18–20 These studies have been conducted in diverse populations with variable definitions of care fragmentation, and no previous efforts have been made to synthesize this information.

The purpose of this review was to determine if there was an association between fragmentation of hospital care and mortality, hospital length-of-stay, cost, and readmission risk in adult patients. It is essential for health professionals, patients, and other stakeholders to understand the impact of interhospital care fragmentation on patient outcomes in order to more appropriately evaluate the value and quality of care provided, as well as the outcomes patients experience. This systematic review sheds light on this area and identifies important gaps in the evidence around the impact of care fragmentation.

Methods

Registration, Protocol, and Disclosures

This systematic review was registered with Prospero (CRD42018094849) and adheres to PRISMA guidelines. The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Study Search and Selection

We searched MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and the Science Citation Index for English articles published in peer-reviewed journals through April 30, 2018. The following terms were used in our search string: “continuity of patient care,” “patient readmission,” “outcomes,” “fragmentation of care,” “fragmented care,” and “discontinuity of care.” A full example of our search string is included in Appendix 1. Eligible studies were cohort, case control, and cross-sectional studies, conducted in adults that reported an association between fragmentation of care and one or more of the following patient outcomes: mortality, hospital length of stay, cost, and healthcare utilization. Experimental studies, studies on pediatric patients, and qualitative studies were excluded.

One author (ST) reviewed each title and abstract for inclusion. Then two authors (ST and KS) reviewed the selected abstracts and selected studies for full text review. Then, both authors selected a set of studies to be included and disagreements were resolved by consensus. The reference list of the included studies was also hand-reviewed to identify potential additional articles. Both authors then screened these articles for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Outcomes

From the included articles, we recorded the number of patients included in each study, patient characteristics, location of the study or data source, and the definition of care fragmentation used. For each paper, we extracted the odds ratio (OR) or adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for each outcome, when reported. If OR/AOR were not available, we contacted the corresponding author of the article or calculated them from the available data. Each author was contacted up to 3 times over a 4-week period via e-mail. Given that the patient outcomes were heterogeneous, we also abstracted additional data based on the specific outcome; for instance, for studies examining mortality, the mortality follow-up period was recorded. This was not extracted for the studies examining length-of-stay or cost.

Risk of Bias Assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to assess the quality and risk of bias in each study.21 The scale includes eight questions that address participant selection, the comparability of the cohorts and outcomes. For the selection domain, we assessed if the exposed cohort was representative of the study’s population (1 star) or not representative (0 stars), whether the non-exposed cohort was drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort (1 star) or not (0 stars), how the exposure was ascertained (secure record or interview 1 star, written self-report, no description; or other 0 stars), and if it was demonstrated that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study (yes 1 star; no 0 stars). Next, we examined whether the study controlled for age, sex, and marital status (1 star) and/or other factors (1 star), or if the cohorts were not comparable based on the design or analysis plan of the research (0 stars). Finally, we evaluated if the outcome was assessed by independent blind assessment or record linkage (1 star), or self-report/other (0 stars), if time to follow-up was sufficient for the outcome to occur (yes 1 star; no 0 stars), and how adequate the follow-up of cohorts was—complete (1 star), less than 20% lost to follow-up/those lost to follow up were not different from those followed (1 star), or follow up rate less than 80%, no description of those lost, or no statement (0 stars). The total number of stars was counted: a “good” quality study had 3–4 stars for selection, 1–2 stars in comparability, and 2–3 stars in outcome/exposure, a “fair” study had 2 stars for selection, 1–2 stars for comparability, and 2–3 stars in outcome/exposure, and a “poor” quality study had 0–1 star in selection domain or 0 stars in comparability or 0–1 stars in outcome/exposure.

Due to heterogenous study populations and a small number of articles for several outcomes, we decided to not pool the results for each outcome in a meta-analysis; additional details are provided in the “Results” section.

Results

Study Characteristics

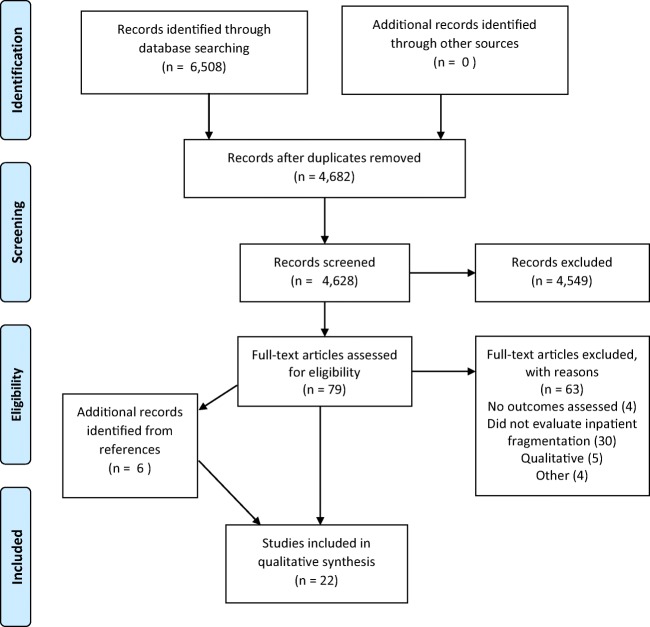

We identified 4682 unique abstracts from our literature search. Of these, 79 full texts were reviewed and 16 were included (Fig. 1). The most common reasons for exclusion were that studies analyzed outpatient continuity of care or fragmentation between physicians or emergency rooms (n = 4592), and that studies did not assess one of the patient outcomes of interest (n = 4056). The most common reason for exclusion of full-text articles reviewed was that they did not assess inpatient fragmentation (n = 30). Six additional articles were identified in the references of included articles and were also included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowsheet for article selection.

Of the 22 included studies, all but one were retrospective observational studies using secondary data. Eighteen studies reported mortality, 6 reported hospital length of stay, 4 reported hospital cost, and 3 reported hospital readmission rates. Some studies were included in multiple groups if they evaluated multiple outcomes. Duration of study follow-up ranged from 30 days to 9 years. Nineteen of the studies were in the USA, 2 in Canada, and 1 in Israel. Characteristics of each study are included in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4. The 18 studies that evaluated patient mortality included 4,248,826 participants with a wide array of diagnoses as described in Table 1. Hence, we determined that study populations were too heterogenous to perform a meta-analysis for this outcome. The other outcomes were limited similarly by heterogenous study populations and a small number of articles in each category.

Table 1.

Studies with Mortality as an Outcome

| Source | Location | Number of patients | Study population | Definition of care fragmentation | Mortality follow-up period | Ottawa bias assessment | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jia 200722 | Florida | 1818 | Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients diagnosed with acute stroke | VHA + Medicare, VHA + Medicaid, Triple (VHA + Medicare and Medicaid) | 1 year after discharge | Fair |

VHA-Medicare AOR 1.6 (1.0–2.4) VHA-Medicaid AOR 2.8 (1.0–7.4) Triple AOR 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| Wolinsky 200723 | USA | 1522 | Male veterans > 70 | Veterans who self-reported use of both VHA and Medicare (dual use) for inpatient hospitalizations | 9-year mortality | Fair | AHR 1.56 (1.12–2.17) |

| Staples 201424 | Toronto, Canada | 198,149 | All adult patients readmitted to one of 21 acute care hospitals in the Toronto area | Readmission to a hospital different than the one they were discharged from | 30 days | Good |

OR 1.26 (1.23–1.30) AOR 1.06 (1.02–1.10) |

| Saunders 201425 | USA | 6752 | Medicare patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | In-hospital and 30-day mortality | Good |

In-hospital: not reported (per data use agreement) but non-significant 30 days: OR 0.95 (0.56–1.62) |

| Glebova 201426 | Maryland | 115 | Patients undergoing thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair, 2002–2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Mortality during readmission, at 30 days, 1 year, 5 years, until last follow-up | Good |

Non-fragmented vs. fragmented During readmission: 14% (1) vs. 0 30 days: 0 vs. 0 1 year: 43% (3) vs. 8% (2) (p = 0.05) At final follow-up: 43% (3) vs. 15% (4) (p = 0.11) |

| Tsai 201527 | USA (Medicare) | 93,062 | Patients with coronary artery bypass graft, pulmonary lobectomy, endovascular aneurysm repair, open AAA repair, colectomy, total hip replacement with a 30-day readmission | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | 30-day mortality | Good |

Risk and hospital adjusted: OR 1.41 (1.31–1.52) Distance-adjusted: OR 1.48 (1.37–1.59) |

| Brooke 201518 | USA (Medicare) | 1,111,046 | Patients undergoing one of 12 major operations* readmitted within 30 days, 2001–2011 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | 90-day mortality | Good | Pooled AOR (Ref: fragmented readmission) 0.74 (0.66–0.83) |

| Pak 201528 | New York State | 2338 | Patients discharged from one of 100 New York State Hospitals following radical cystectomy between 2009 and 2012 with 30 or 90-day readmissions | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | 30- and 90-day mortality | Good |

30 days OR 3.62 (1.52–8.57) 90 days OR 5.66 (2.63–12.2) |

| Luu 201629 | USA (Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results Program [SEER]-Medicare) | 3399 | Patients who had colon cancer surgery who were readmitted within 30 days of discharge, 2000–2009 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed |

Long-term mortality colon-cancer specific mortality 90-day mortality (all-cause and cancer-specific) |

Good |

Long-term mortality: HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.87–1.12) Colon cancer-specific mortality: 1.09 (95% CI 0.77–1.51) 90-day mortality: 1.18 (95% CI 1.02–1.38) |

| Mays 201630 | Chicago, IL | 780 | Patients with recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis, 2006–2012 | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | Mortality during study period | Good | NR but non-significant in adjusted models |

| Zheng 201631 | California (State Inpatient Database [SID]) | 9233 | Patients with major cancer surgery† readmitted within 30 days, 2004–2011 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | In-hospital mortality | Good |

Adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics: 1.31 (1.03–1.66) Adjusted for diagnoses: 1.24 (0.98–1.58) |

| Kothari 201620 | California and Florida | 2996 | Patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplant readmitted within the first year, 2006–2011 | Readmission to a hospital other than where surgery was performed | 30-day mortality after readmission | Good | OR 1.75 (1.16 to 2.65) |

| Justiniano 201719 | New York State | 20,016 | Patients readmitted within 30 days, 2004–2014 | Readmission to a different hospital than where surgery was performed ± under the care of a different physician | 1-year survival (excluding initial 30-day mortality) | Good | HR 1.57 (1.17–2.11) |

| Stitzenberg 201732 | USA (SEER-Medicare) | 7903 | Patients with cancer‡ who underwent extirpative surgery, 2001–2007 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | 90-day mortality | Good | HR 1.15 (1.10–1.19) |

| Hua 201733 | New York State | 26,947 | Mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients re-hospitalized within 30 days at NY state hospitals between 2008 and 2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | In-hospital mortality | Good | ARR 1.11 (1.03–1.20) |

| McAlister 201712 | Canada | 39,368 | Patients with heart failure readmitted within 30 days, 2004–2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | In-hospital mortality | Good |

OR 0.89 (0.82–0.96) *Reference was fragmented group |

| Graboyes 201715 | California | 561 | Patients readmitted within 30 days of a head and neck cancer surgery, 2008–2010 | Readmission to a hospital other than where surgery was performed | In-hospital mortality | Good | OR 2.1 (1.04–4.26) |

| Burke 201811 | USA (National Readmissions Database [NRD]) | 2,722,821 | Patients readmitted within 30 days in 2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | In-hospital mortality | Good |

OR 1.14 (1.10–1.18) AOR 1.21 (1.17–1.25) |

*Open AAA repair, infra-inguinal arterial bypass, aorto-bifemoral bypass, coronary artery bypass surgery, esophagectomy, colectomy, pancreatectomy, cholecystectomy, ventral hernia repair, craniotomy, hip or knee replacement

†Esophagectomy, gastrectomy, pancreatectomy, hepatectomy, proctectomy, lung resection

‡Bladder, esophagus, lung, pancreas cancer

Table 2.

Studies with LOS as an Outcome

| Reference | Data source and location | Number of patients | Study population | Definition of care fragmentation | Ottawa bias assessment | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galanter 201314 | Chicago | 228,151 | Patients admitted to 5 teaching hospitals 2007–2008 | Admitted to more than one hospital | Fair |

Patients admitted to more than one hospital mean LOS 5.58 ± 8.42 Patients with multiple admissions to one hospital mean LOS 5.77 ± 8.42 |

| Brooke 201518 | USA (Medicare) | 1,111,046 | Patients undergoing one of 12 major operations* readmitted within 30 days, 2001–2011 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Good |

Fragmented vs. not (mean LOS) Vascular: 6.7 vs. 8.2 Cardiothoracic: 5.6 vs. 7.1 General: 6.5 vs. 7.1 Neurosurgery: 6.4 v. 7.4 Orthopedic: NR |

| Flaks-Manov 201634 | Israel | 27,057 | Adult patients with state insurance with at least 1 readmission in 2010 | Readmission to a different hospital (DHR) with or without a health information exchange (HIE) | Good |

DHR without HIE: HR 0.90 (CI 0.86–0.94) DHR with HIE: 0.85 (0.79–0.91) |

| McAlister 201712 | Canada | 39,368 | Patients with heart failure, 2004–2013 readmitted within 30 days | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | Good |

Fragmented mean LOS 11.6 (11.3–12.0) n = 6597 Non-fragmented mean LOS 11.0 (10.1–12.0) n = 32771 |

| Graboyes 201715 | California | 561 | Patients readmitted within 30 days of a head and neck cancer surgery, 2008–2010 | Readmission to a hospital other than where surgery was performed | Good | Median LOS fragmented v. not 4 vs. 5 |

| Burke 201811 | USA (NRD) | 2,722,821 | Patients readmitted within 30 days in 2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the patient was discharged from | Good |

Readmission to non-index adjusted HR 0.87 (0.86–0.88) |

*Open AAA repair, infra-inguinal arterial bypass, aorto-bifemoral bypass, coronary artery bypass surgery, esophagectomy, colectomy, pancreatectomy, cholecystectomy, ventral hernia repair, craniotomy, hip or knee replacement

Table 3.

Studies with Cost/Charges as an Outcome

| Reference | Data source and location | Number of patients | Study population | Definition of care fragmentation | Ottawa bias assessment | Outcome assessed | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glebova 201426 | Maryland | 115 | Patients undergoing thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair, 2002–2013 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Good | Total charges for readmission |

Fragmented total: 20,000 ± 4400 Non-fragmented total: 42,000 ± 8800 |

| Luu 201629 | USA (SEER-Medicare) | 3,399 | Patients who had colon cancer surgery who were readmitted within 30 days of discharge, 2000–2009 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Good | Cost of care for up to 1 year after index admission |

Difference $8405 (95% CI − $4202 to $23,114) |

| Stitzenberg 201732 | USA (SEER-Medicare) | 7903 | Patients with cancer* who underwent extirpative surgery, 2001–2007 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Good | Total costs incurred in the 90 days post-index discharge |

Fragmented v. not Medical diagnoses: $37,806 ± $55,730 vs. $36,052 ± $37,541 Surgical diagnoses: $50,465 ± $75,710 vs. $56,559 ± $62,438 |

| Parreco 201717 | USA (NRD) | 110,854 | Patients admitted with a principal diagnosis of trauma in 2013–2014 | Readmission to a different hospital than the one they were previously discharged from | Good | Total cost of readmission |

Fragmented (median) $8568 (IQR $4935–$16,078) Non-fragmented (median) $8298 (IQR $4899–$14,911) |

*Bladder, esophagus, lung, pancreas cancer

Table 4.

Studies with Readmissions as an Outcome

| Reference | Data source and location | Number of patients | Study population | Definition of care fragmentation | Ottawa bias assessment | AOR/OR for rehospitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jia 200722 | Florida | 1818 | VA patients diagnosed with acute stroke | VHA + Medicare, VHA + Medicaid, Triple (VHA + Medicare and Medicaid) | Good |

VHA + Medicare: AOR 1.5 (1.1–1.9) VHA + Medicaid: AOR 2.3 (1.2–4.5) Triple: AOR 13.6 (6.1–30.1) |

| Axon 201635 | USA | 13,977 | Veterans with heart failure hospitalized at the VA or non-VA facilities, 2007–2011 | Dual use | Good | AOR 1.93 (1.85–2.01) |

| Zheng 201631 | California (SID) | 9233 | Patients with major cancer surgery* readmitted within 30 days | Readmission to a different hospital than the one where the surgery was performed | Good |

Adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics: 1.17 (1.03–1.34) Adjusted for patient characteristics: 1.16 (1.02–1/32) |

*Esophagectomy, gastrectomy, pancreatectomy, hepatectomy, proctectomy, lung resection

Study Risk of Bias

All studies generally had a clear research question, study population, and appropriate exposures and outcomes. Most of the studies (86%) were characterized as good quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment tool and 14% were fair quality (Supplemental Table 1).

Mortality

Eighteen of the included articles utilized mortality as a primary endpoint (Table 1). All but two22, 23 defined care fragmentation as a readmission to a different hospital than the index admission. Seven studies examined in-hospital mortality, 6 studies examined mortality 30 days post-discharge, and 9 studies examined mortality follow-up periods 90 days or longer (some studies included multiple endpoints). Of the studies examining in-hospital mortality, 4 report fragmented readmissions was associated with 10% to two times higher mortality odds (AOR 1.11–2.1).11, 12, 15, 24 One study had variable results depending on the factors adjusted for in analyses,25 while two did not find significant associations between fragmentation and mortality.26, 27 Of the studies examining mortality post-discharge, 4 reported that fragmentation was associated with 6% to over three-fold higher odds for death within 30 days (AOR 1.06–3.62).20, 28–30 Among 6 studies, fragmentation was associated with no increased odds to five-fold higher odds for death beyond 30 days after a fragmented readmission (AOR 1.0–5.66).18, 19, 22, 23, 30, 31

Overall, 11 studies looked at mortality following a fragmented postoperative readmission, and 7 of these included cancer-related surgeries. Among the 5 studies that included only patients with cancer,15, 25, 30–32 3 showed post-operative fragmentation associated with 18% to five-fold higher mortality odds (AOR 1.18–5.66). In 4 studies that included both cancer-related and non-cancer-related surgeries,19, 20, 26, 27 only 2 found post-operative care fragmentation was associated with increased odds of mortality, but the increase was notable: 50 to 75% higher mortality odds (OR 1.57–1.75).

Length of Stay

Six of the included articles used length-of-stay(LOS) as an outcome (Table 2). All defined care fragmentation as a readmission to a different hospital than the index admission. The studies varied widely in how they reported LOS, with some reporting median or mean LOS and others reporting the hazard ratio for discharge on a given day. One study reported a longer mean LOS of less than 1 day in fragmented readmissions versus non-fragmented readmissions. (11.6 days vs. 11.0 days),12 and 2 studies reported a hazard ratio of 10–15% less for discharge on a given day in fragmented readmissions (HR 0.90–0.85).11, 33

Costs and Charges

Four of the included studies examined cost or charges as a primary or secondary outcome (Table 3). These studies varied in their timeframe of measurement: 2 examined in-hospital costs or charges, 1 examined costs for a year following cancer diagnosis, and 1 examined costs for 90 days following surgery. The differences in costs/charges between fragmented and non-fragmented readmissions ranged from $270 to $22,000. Only 1 found statistically significantly higher costs in patients with fragmented readmissions in adjusted models, with a median cost of a fragmented readmission of $8568 and the median cost of a non-fragmented readmission of $8298.17

Hospital Readmission

Three papers examined the association of care fragmentation and hospital readmission (Table 4). They found that patients with fragmented readmissions were between 16% and twice as likely to experience a third admission than patients who did not experience interhospital care fragmentation (AOR 1.16–2.3).23, 25, 34 Notably, one subgroup who accessed care at the VA and also held Medicare and Medicaid insurance was reported to have an AOR of 13.6 (95% CI 6.1–30.1) for a third admission following a fragmented readmission.23

Discussion

In this systematic review, we analyzed 22 studies examining patient outcomes during and following a fragmented hospital readmission. Overall, 11 of the 18 studies that examined patient mortality found increased odds of mortality during or following a fragmented readmission, 1 had mixed results, and 6 did not show a difference in the odds of mortality. Three of the 6 studies reporting length-of-stay found a longer length-of-stay or decreased hazard ratio for discharge in fragmented readmissions. Among studies examining cost/charges, 1 study reported higher costs during a fragmented readmission, 1 had mixed results, and 2 reported higher costs/charges during or after non-fragmented readmissions. Finally, all three papers that investigated the odds of a third hospital readmission following a fragmented readmission found higher odds of a third admission in patients who experienced fragmentation, compared to patients who had a non-fragmented readmission. Overall, this systematic review suggests that fragmented hospital readmissions contribute to increased mortality, longer length-of-stay, and increased risk of future readmission to the hospital.

Our systematic review adds to the previous reviews of the association between continuity of care and patient outcomes.2, 35 Previous reviews have focused on outpatients only or on continuity during transitions of care (i.e., inpatient to outpatient). Van Walraven et al.2 performed a systematic review of studies examining continuity of care, healthcare use, and patient satisfaction, primarily focused on continuity following hospital discharge and in the outpatient setting. They found that there were significant associations between improved provider continuity, decreased healthcare use, and increased patient satisfaction. Our review is the first to synthesize the literature on fragmented hospital readmissions and adds to the existing literature by including papers that address different types of continuity.23, 33

Our study is subject to limitations. Our definition of interhospital care fragmentation was narrow in an effort to make studies as comparable as possible, which may have excluded some studies looking at other types of hospital-based fragmentation (i.e., fragmentation across providers in a hospital or interhospital transfers). Notably, many of the included studies examined very specific populations (i.e., postoperative from cancer surgery), making the results less generalizable. Finally, because of the retrospective nature of most of the included studies, we are unable to know whether fragmentation was the cause or an effect of a patient’s poor outcomes.2 This is especially true regarding hospital readmissions—if the patient had a poor experience during their index admission, they may actively seek care elsewhere, leading to a fragmented readmission. If they remain dissatisfied following the readmission or their health has not improved, they may seek care at yet another hospital.

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that interhospital care fragmentation may be a contributor to increased mortality, longer lengths-of-stay, and readmissions. These results support the need for improved care coordination and should increase provider awareness of the role of interhospital care fragmentation on our patients and hospitals. Interhospital care fragmentation should be considered when designing interventions to reduce duplicative care and waste, and when evaluating provider and hospital outcomes.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 13 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

(DOC 63 kb)

Author’s Contribution

No one contributed to the article who is not listed as an author.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Weir DL, McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT. The interplay between continuity of care, multimorbidity, and adverse events in patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2016;54(4):386–393. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, Forster AJ. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):947–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo J-Y, Chou Y-J, Pu C, Pu C. Effect of continuity of care on drug-drug interactions. Med Care. 2017;55(8):744–751. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai Y-R, Yang Y-S, Tsai M-L, et al. Impact of potentially inappropriate medication and continuity of care in a sample of Taiwan elderly patients with diabetes mellitus who have also experienced heart failure. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;16(10):1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekelis K, Roberts DW, Zhou W, Skinner J. Fragmentation of care and the use of head computed tomography in patients with ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):430–436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879–1885. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao Y-H, Wu S-C. STROBE-compliant article: is continuity of care associated with avoidable hospitalization in older asthmatic patients? Medicine. 2016;95(38):e4948–7. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin I-P, Wu S-C. Effects of long-term high continuity of care on avoidable hospitalizations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Health Policy. 2017;121(9):1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missios S, Bekelis K. Outpatient continuity of care and 30-day readmission after spine surgery. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1309–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan VS, Burman M, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. JGIM. 2005;20(3):226–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke RE, Jones CD, Hosokawa P, Glorioso TJ, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Influence of nonindex hospital readmission on length of stay and mortality. Med Care. 2018;56(1):85–90. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAlister FA, Youngson E, Kaul P. Patients with heart ailure readmitted to the original hospital have better outcomes than those readmitted elsewhere. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5):e004892–e004897. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flaks-Manov N, Shadmi E, Bitterman H, Balicer R. Readmission to a different hospital—risk factors and impact on length of stay. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A148. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galanter WL, Applebaum A, Boddipalli V, et al. Migration of patients between five urban teaching hospitals in Chicago. J Med Syst. 2013;37(2):1989–8. doi: 10.1007/s10916-013-9930-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graboyes EM, Kallogjeri D, Saeed MJ, Olsen MA, Nussenbaum B. Postoperative care fragmentation and thirty-day unplanned readmissions after head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2016;127(4):868–874. doi: 10.1002/lary.26301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chappidi MR, Kates M, Stimson CJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Pierorazio PM. Quantifying nonindex hospital readmissions and care fragmentation after major urological oncology surgeries in a nationally representative sample. J Urol. 2017;197(1):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parreco J, Buicko J, Cortolillo N, Namias N, Rattan R. Risk factors and costs associated with nationwide nonelective readmission after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):126–134. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooke BS, Goodney PP, Kraiss LW, Gottlieb DJ, Samore MH, Finlayson SRG. Readmission destination and risk of mortality after major surgery: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):884–895. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Justiniano CF, Xu Z, Becerra AZ, et al. Long-term deleterious impact of surgeon care fragmentation after colorectal surgery on survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(11):1147–1154. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kothari AN, Loy VM, Brownless SA, et al. Adverse effect of post-discharge care fragmentation on outcomes after readmissions after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(1):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolinsky FD, Miller TR, An H, Brezinski PR, Vaughn TE, Rosenthal GE. Dual use of Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration: are there adverse health outcomes? BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):651–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia H, Zheng Y, Reker DM, et al. Multiple system utilization and mortality for veterans with stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(2):355–360. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254457.38901.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua M, Ng Gong M, Miltiades A, Wunsch H. Outcomes after rehospitalization at the same hospital or a different hospital following critical illness. AJRCCM. 2017;195(11):1486–1493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-0912OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng C, Habermann EB, Shara NM, et al. Fragmentation of care after surgical discharge: non-index readmission after major cancer surgery. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2016;222(5):780–789.e782. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders RS, Fernandes-Taylor S, Kind AJH, et al. Rehospitalization to primary versus different facilities following abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(6):1502–1510.e1502. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glebova NO, Hicks CW, Taylor R, et al. Readmissions after complex aneurysm repair are frequent, costly, and primarily at nonindex hospitals. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(6):1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staples JA, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier DA. Site of hospital readmission and mortality: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(2):E77–E85. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Care Fragmentation in the postdischarge period. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):59–6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pak JS, Lascano D, Kabat DH, et al. Patterns of care for readmission after radical cystectomy in New York State and the effect of care fragmentation. Urol Oncol. 2015;33(10):426.e13–426.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stitzenberg KB, Chang Y, Smith A, Meyers MO, Nielsen ME. Impact of location of readmission on outcomes after major cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(2):319–329. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luu N-P, Hussain T, Chang H-Y, Pfoh E, Pollack CE. Readmissions after colon cancer surgery: does it matter where patients are readmitted? JOP. 2016;12(5):e502–e512. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flaks-Manov N, Shadmi E, Hoshen M, Balicer R. Health information exchange systems and length of stay in readmissions to a different hospital. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(6):401–406. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Everett CJ, Heidenreich P, Hunt K. Dual health care system use is associated with higher rates of hospitalization and hospital readmission among veterans with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2016;174(C):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;1219-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

(DOC 63 kb)