Abstract

Hippocampal pyramidal cells encode memory engrams which guide adaptive behavior. Selection of engram-forming cells is regulated by somatostatin-positive dendrite-targeting interneurons, which inhibit pyramidal cells that are not required for memory-formation. Here, we found that GABAergic neurons of the mouse nucleus incertus (NI) selectively inhibit somatostatin-positive interneurons in the hippocampus, both mono-synaptically and indirectly via the inhibition of their sub-cortical excitatory inputs. We demonstrated that NI GABAergic neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from brain areas processing important environmental information, and their hippocampal projections are strongly activated by salient environmental inputs in vivo. Optogenetic manipulations of NI GABAergic neurons can shift hippocampal network state and bidirectionally modify the strength of contextual fear memory formation. Our results indicate that brainstem NI GABAergic cells are essential for controlling contextual memories.

INTRODUCTION

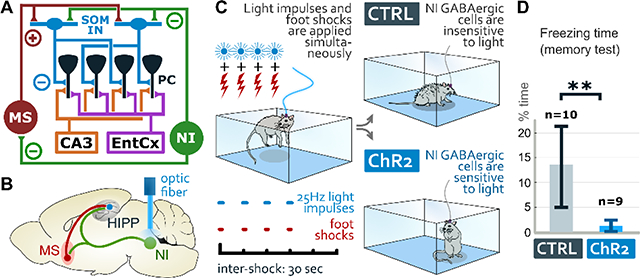

Associative learning is essential for survival and the mammalian hippocampal neurocircuitry has been shown to play a central role in the formation of specific contextual memories. Contrary to the slow, neuromodulatory role commonly associated with brainstem systems, we discovered a highly specific, spatiotemporally precise, inhibitory ascending brainstem pathway that effectively controls hippocampal fear memory formation. Pyramidal neurons of the dorsal hippocampus CA1 region pair multisensory contextual information (Fig. A, CA3) with direct sensory-related inputs (Fig. A, EntCx). Each memory trace is encoded by a specific subset of pyramidal neurons. Remaining pyramidal cells must be actively excluded from the given memory encoding process by direct dendritic inhibition, which is executed by somatostatin-positive (SOM) dendrite-targeting interneurons. SOM interneurons are activated by excitatory inputs from the medial septum (MS) upon salient environmental stimuli. Previous models suggested that the subset of memory-forming pyramidal cells escape this dendritic inhibition only by a stochastic, self-regulatory process, in which some SOM interneurons become inactive. However, we hypothesized that this process must be regulated more actively, and SOM interneurons should be inhibited precisely in time, based on subcortical information, otherwise, under-recruitment of pyramidal neurons would lead to unstable memory formation.

RATIONALE

GABAergic inhibitory neurons of the brainstem nucleus incertus (NI) seemed well suited to counter-balance the activation of SOM interneurons as they specifically project to the stratum oriens of the hippocampus where most SOM cells arborize. Using cell type-specific neuronal tract-tracing, immuno-electron microscopy and electrophysiological methods, we investigated the targets of NI in the mouse hippocampus, and in MS where excitation of SOM cells originates. We also used monosynaptic rabies-tracing to identify the inputs of GABAergic NI neurons. Two-photon calcium imaging was used to analyze the response of GABAergic NI fibers to sensory stimuli in vivo. Finally, we used in vivo optogenetics combined with behavioral experiments or electrophysiological recordings to explore the role of NI in contextual memory formation and hippocampal network activity.

RESULTS

We discovered that NI GABAergic neurons selectively inhibit hippocampal SOM interneurons in stratum oriens both directly and also indirectly via inhibition of excitatory neurons in MS (Fig. A, B). We observed that NI GABAergic neurons receive direct inputs from several brain areas that process salient environmental stimuli, including the prefrontal cortex and lateral habenula and these salient sensory stimuli (e.g. air-puffs, water rewards) rapidly activated hippocampal fibers of NI GABAergic neurons in vivo. Behavioral experiments revealed that optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons or their fibers in hippocampus, precisely at the moment of aversive stimuli (Fig. C), prevented the formation of fear memories, while this effect was absent if light stimulation was not aligned with the stimuli. However, optogenetic inhibition of NI GABAergic neurons during fear conditioning resulted in the formation of excessively enhanced contextual memories. Optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons also changed memory encoding-related hippocampal theta rhythms.

CONCLUSION

A role of NI GABAergic neurons may be fine-tuning of the selection of memory-encoding pyramidal cells, based on the relevance and/or modality of environmental inputs. They may also help filter non-relevant everyday experiences, (e.g. those to which animals have already accommodated), by regulating the sparsity of memory-encoding dorsal CA1 pyramidal neurons. NI GABAergic neuron dysfunction may also contribute to dementia-like disorders or pathological memory formation in certain types of anxiety or stress disorders. Our data represent an unexpectedly specific role of an ascending inhibitory pathway from a brainstem nucleus in memory encoding.

Graphical Abstract

Nucleus incertus (NI) activation prevents memory formation. NI GABAergic neurons regulate contextual memory formation by inhibiting somatostatin interneurons (SOM IN) directly in hippocampus (A) and indirectly via inhibition of their excitatory inputs in the medial septum (MS). Pairing optical stimulation (B) with aversive stimuli (C), eliminates fear memory-formation, while control mice display normal fear (freezing) after exposure to the same environment a day later (D).

Introduction

Fear memories, which allow mice to avoid future aversive events, are formed by associating aversive stimuli (unconditioned stimulus, US) with their environmental context. The dorsal hippocampus (HIPP) plays an essential role in contextual memory encoding and transmits this information mainly via CA1 pyramidal neurons to the cortex (1–3). Dorsal CA1 pyramidal neurons receive the unified representation of the multisensory context at their proximal dendrites from the CA3 subfield inputs (4), while the discrete sensory attribute of the aversive stimulus (US) is primarily conveyed by the direct temporo-ammonic pathway to their distal dendrites (5–7). At the cellular level, the dendritic interactions of these inputs may result in long-term synaptic plasticity in CA1 pyramidal neurons (8–10), a subset of which can form memory engrams to encode contextual fear memories (11). Both intact contextual information processing and direct sensory information related inputs are required for precise episodic memory formation (12–14).

The number of dorsal CA1 pyramidal neurons participating in the formation of a given memory engram component must be delicately balanced (15). The majority of pyramidal cells must be inhibited, (i.e., excluded from memory encoding at the moment of memory formation), because if the US information reaches too many pyramidal cells, engrams may lack specificity, which may engender memory interference (16, 17). Exclusion of US information in hippocampal CA1 is achieved by somatostatin (SOM) expressing oriens-lacunosum moleculare (OLM) inhibitory interneurons (16). OLM cells establish far the most abundant local SOM-positive synapses (16, 18). OLM cells selectively inhibit the distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons, which receive the primary sensory-related inputs from the entorhinal cortex, representing the US (19–22). Indeed, artificial silencing of dorsal CA1 SOM-positive neurons at the moment of US presentation disrupts fear learning (16, 17). OLM cell activity is synchronized with the US via cholinergic and glutamatergic excitatory inputs from the medial septum (MS) and diagonal bands of Broca. Cholinergic neurons are rapidly and reliably recruited by salient environmental stimuli (16, 23) and strongly innervate hippocampal OLM neurons (3, 16, 21), while MS glutamatergic neurons display locomotion-related activity increases, and also innervate hippocampal OLM cells (22, 24).

Conversely, if too many pyramidal neurons are inhibited, allocation to engrams may be insufficient and memory formation would be impaired (25). Thus, to balance the sparsity of hippocampal engrams, activation of OLM neurons must be adequately controlled. Inhibitory regulation of OLM neurons would ideally arise also from an extra-hippocampal area that integrates relevant environmental information, yet the source of such balancing inhibitory input to OLM neurons was, until now, unknown.

The pontine nucleus incertus (NI), characterized by expression of the neuropeptide, relaxin-3 (26–28), sends an ascending GABAergic pathway to the septo-hippocampal system. NI neurons display activity related to hippocampal theta rhythm and are thought to play an important role in stress and arousal (29–34).

Here, using cell type-specific neuronal tract-tracing, immunogold receptor localization and electrophysiological methods, we discovered that NI GABAergic neurons selectively inhibit hippocampal SOM-positive neurons both mono-synaptically and also indirectly via inhibition of excitatory glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons in the MS. Using monosynaptic rabies-tracing, we observed that NI receives direct inputs from several brain areas that process salient environmental stimuli, and indeed, using in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in head-fixed awake mice, we demonstrated that such stimuli rapidly activated hippocampal fibers of NI GABAergic neurons. Behavioral conditioned fear experiments revealed that optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic cells or their fibers in the dorsal HIPP, precisely at the moment of US presentation, prevented the formation of contextual fear memories. In parallel, optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons decreased the power and frequency of the encoding-related hippocampal theta rhythm in vivo. In contrast, optogenetic inhibition of NI GABAergic neurons during fear conditioning, resulted in the formation of excessively enhanced contextual memories. These findings demonstrate the fundamental importance of NI GABAergic neurons in hippocampus-dependent episodic memory formation.

Results

NI GABAergic neurons selectively inhibit hippocampal SOM-positive interneurons

We injected Cre-dependent adeno-associated tracer virus (AAV5, see Supplementary Materials and Methods) into the NI of vesicular GABA transporter (vGAT)-Cre mice to reveal the projections of GABAergic neurons of NI (Fig. 1A). It demonstrated that NI GABAergic fibers selectively project to the stratum oriens of the HIPP and the hilus of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 1B). SOM neurons are typically found only in these sub-regions of HIPP (35). GABAergic NI nerve terminals were all positive for the neuropeptide, relaxin-3 (Fig. 1C). Double retrograde tracing in wild-type (WT) mice, using the retrograde tracers FluoroGold (FG) and Choleratoxin B (CTB), revealed that NI and HIPP are connected almost exclusively ipsilaterally (Fig. S1A–C). Using Cre-dependent AAV5 viral tracing, we also confirmed that brainstem areas surrounding NI do not send GABAergic projections to the HIPP (Fig. S2A–F) and NI GABAergic neurons do not use glutamate, glycine, acetylcholine, serotonin or other monoamines as neurotransmitters (Fig. S2G–J).

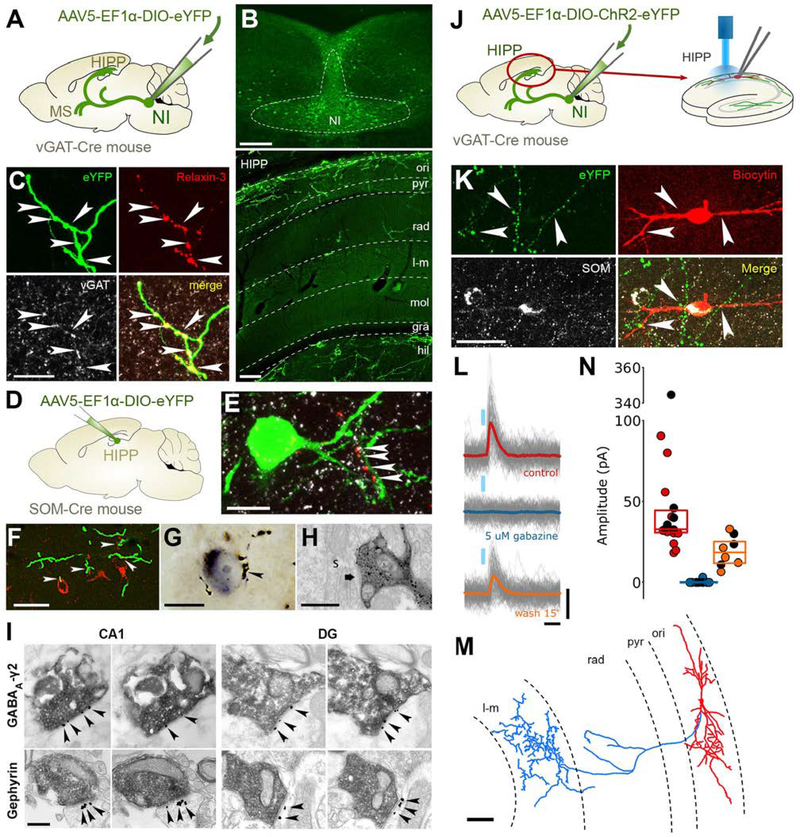

Figure 1: NI neurons target HIPP SOM-positive neurons with GABAergic synapses.

A: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP or AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice (n=7). B: Images illustrate an injection site (upper panel) and the layer-specific distribution pattern of GABAergic NI fibers in the hippocampus (HIPP) stratum oriens and hilus (lower panel) where SOM neurons are known to be abundant. Scale bars: 200 μm. C: NI fibers (green) in the HIPP are immunopositive for relaxin-3 (red) and vGAT (white). Scale bar: 10 μm. (Also see Suppl. Data for Fig. 1). D: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP was injected into the bilateral hippocampus of SOM-Cre mice (n=2). E: Relaxin-3 positive NI fibers (red) establish synaptic contacts, marked by gephyrin (white), on SOM-positive interneurons (green) in the HIPP. Scale bar: 10 μm. (Also see Suppl. Data for Fig. 1). F: eYFP-positive NI GABAergic fibers (green) in the HIPP establishing putative contacts (white arrowheads) with SOM-positive interneurons (red). Scale bar: 20 μm. G: NI GABAergic fiber (labeled with brown silver-gold-intensified-DAB precipitate) establish synaptic contact with a SOM-positive interneuron (labeled with black DAB-Ni precipitate) in the stratum oriens of dorsal CA1. Black arrowhead indicates the NI nerve terminal shown in panel G. Scale bar: 10 μm. H: The same terminal marked in F establishing a symmetrical synaptic contact (black arrow) on the soma (s) of the SOM-positive interneuron. Scale bar: 600 nm. I: EM images of serial sections of AAV-eYFP positive NI terminals (immunperoxidase labeling, black DAB precipitate) that establish symmetrical synaptic contacts in the CA1 stratum oriens or in the hilus (DG), containing the GABAA-receptor γ2 subunit (upper row) and the scaffolding protein gephyrin (lower row). The immunogold particles labeling the postsynaptic proteins are marked by black arrowheads. Scale bar: 300 nm. (See Suppl. Data for Fig. 1). J: For in vitro recordings AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice (n=9). After 6 weeks, 300-μm-thick horizontal slices were prepared from the HIPP and transferred into a dual superfusion chamber. Interneurons located in the stratum oriens were whole-cell patch clamped in voltage clamp mode, and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) evoked by the optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic fibers were measured. (See Supplementary Materials and Methods and Suppl. Data for Fig. 1). K: A representative recorded cell (biocytin labeling, red) identified as a SOM-positive interneuron (white). Note the eYFP-positive NI GABAergic fibers (green) with putative contacts targets this neuron (arrowheads). Scale bar: 30 μm. L: Optogenetically evoked GABAergic IPSCs of interneuron in panel K. 100 consecutive traces evoked by 2 ms light pulses are overlaid with grey in every conditions. Responses are strong in controls (average in red), but that were completely abolished by 5 μM gabazine (average in blue), and partially recovered after 15 min of washout (average in orange). Scale bars: 10 ms, 40 pA. M: Morphological reconstruction of the OLM cell shown in K. Scale bar: 50 μm. N: PSC amplitude distribution from all 18 recorded neurons. Identified O-LM cells are filled black dots. (See Suppl. Data for Fig. 1).

To identify the targets of NI GABAergic fibers in the HIPP, we injected Cre-dependent AAV5 tracer virus into the NI of vGAT-Cre-tdTomato reporter mice (Supplementary Materials and Methods and Fig. S1D). Double immunoperoxidase reactions and correlated light- and electron microscopy revealed that NI fibers establish synaptic contacts with tdTomato-expressing GABAergic interneurons in the HIPP (at least 87% were identified as interneurons, Fig. S1E). Then, using Cre-dependent AAV5 viral-labeling of SOM interneurons in SOM-Cre mice, we found that most of the relaxin-3 positive NI terminals (at least 62%) targeted SOM-positive cells (Fig. 1D–E). The vast majority of SOM-positive CA1 fibers are present in stratum lacunosum-moleculare, which clearly indicated that they originate from OLM cells as described before (16, 18, 36). Using Cre-dependent AAV5 viral-labeling in vGAT-Cre mice, we observed that NI GABAergic fibers establish symmetrical synapses typically with SOM-positive interneurons (Fig. 1F–H) that also contain the previously identified markers (37) metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α (mGluR1α) and parvalbumin (PV, Fig. S1F–H). These results demonstrate that the primary target of NI fibers in the HIPP are the dendrite-targeting SOM-positive interneurons, the local effect of which neurons mostly originate from OLM cells. Using a combination of CTB and Cre-dependent AAV5 in vGAT-Cre mice, we observed that some SOM positive GABAergic interneurons in the HIPP, which project to the subiculum or the MS (38, 39) also receive contacts from the NI (Supplementary Materials and Methods and Fig. S1I–P).

Using correlated light- and immuno-electron microscopic analysis, we found that the synapses of NI fibers are symmetrical, contain GABAA-receptor γ2 subunits and the GABAergic synapse specific scaffolding protein gephyrin, postsynaptically in the HIPP (Fig. 1I).

To investigate the functional properties of these GABAergic synapses, we injected channelrhodopsin (ChR2) containing Cre-dependent AAV5 into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice and 6–12 weeks later, we cut horizontal slices from the HIPP for in vitro optogenetic experiments (Fig. 1J, Supplementary Materials and Methods, Fig. S3A, Fig. S4A). Light stimulation of hippocampal NI GABAergic fibers reliably evoked gabazine-sensitive inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSCs) from voltage-clamped interneurons located to the stratum oriens of CA1 (Fig. 1K–N, Fig. S3B–C), indicating GABAA-receptor-dependent GABAergic neurotransmission in these synapses. Although NI GABAergic neurons express relaxin-3 and HIPP SOM neurons express its receptor (28, 40), gabazine could block all currents at these time scales. Recorded neurons were filled with biocytin and post-hoc neurochemical analysis of filled neurons revealed that at least 12 of 18 cells were clearly SOM-positive (Fig. 1K). Although not all recorded neurons could be fully morphologically reconstructed, 6 of them were unequivocally identified as typical dendrite-targeting OLM neurons (Fig. 1M). Altogether we found, that 14 out of 18 randomly recorded and NI GABAergic cells targeted neurons were either SOM-positive or SOM-false-negative OLM cells, suggesting that at least 78% of the target cells are SOM-positive. Whereas, in immunohistochemistry described above, this number was at least 62%. Because only 14% of CA1 interneurons are SOM-positive (41), these numbers suggest a very high target specificity for SOM-containing interneurons. Light stimulation suggested that NI GABAergic synapses display short-term synaptic depression at higher stimulation frequencies (30–50 Hz: Fig. S3C) that was not observed at lower frequencies (5–20 Hz: Fig. S3C). These data clearly demonstrate that NI fibers directly target SOM positive dendrite-targeting OLM interneurons in the HIPP with functional GABAergic synapses.

NI GABAergic neurons inhibit MS neurons that excite OLM interneurons

HIPP SOM neurons receive their main extra-hippocampal excitatory inputs from glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons of the MS (16, 21, 22). We hypothesized that NI may also inhibit HIPP SOM-positive OLM cells indirectly, by inhibition of these excitatory input neurons in the MS.

Using Cre-dependent AAVs to label GABAergic NI neurons in vGAT-Cre mice (Fig. 2A), we determined that MS is strongly innervated by relaxin-3 positive NI GABAergic fibers (Fig. 2B–C). NI neurons established GABAA-receptor γ2 subunit-positive and gephyrin-positive symmetrical synapses in MS (Fig. 2D). Using Cre-dependent AAV5 viral tracing we also confirmed that brainstem areas surrounding NI do not send GABAergic projections to the MS (Fig. S2A–H).

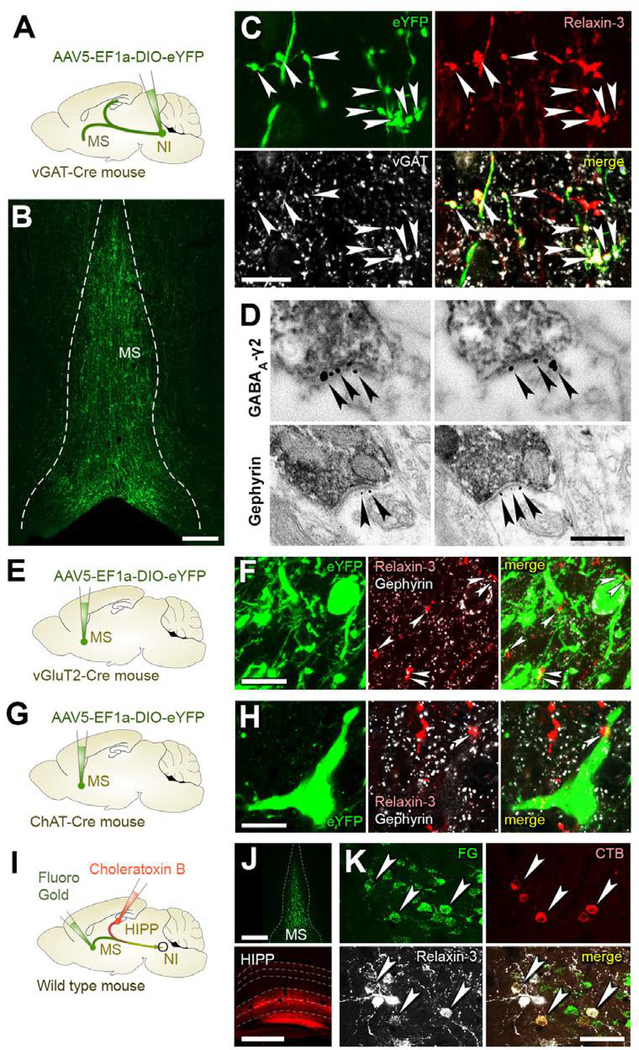

Figure 2: NI GABAergic neurons innervate excitatory medial septal neurons and HIPP simultaneously.

A: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP or AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice (n=7).

B: NI GABAergic fibers strongly innervate the medial septum (MS). Scale bar: 200 μm.

C: NI GABAergic fibers in the MS (green) are immunopositive for relaxin-3 (red) and vGAT (white), indicated by white arrowheads. Scale bar: 10 μm. (For statistical data see Suppl. Data for Fig. 2).

D: EM images of serial sections of relaxin-3 positive NI terminals (immunperoxidase labeling, black DAB precipitate) reveal the presence of symmetrical synapses in the MS, containing the GABAA-receptor γ2 subunit (upper row) or the scaffolding protein gephyrin (lower row). The immunogold particles labeling the postsynaptic proteins are marked by black arrowheads. Scale bar: 300 nm. (Suppl. Data for Fig. 2).

E: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP was injected into the NI of vGluT2-Cre mice (n=2).

F: vGluT2-positive neurons (green) are frequently innervated by relaxin-3 positive fibers (red), establishing gephyrin-positive (white) synaptic contacts (white arrowheads) on their dendrites. Scale bar: 10 μm. (See Suppl. Data for Fig. 2). G: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP was injected into the NI of ChAT-Cre mice (n=2).

H: ChAT-positive neurons (green) were innervated by relaxin-3 positive fibers (red), establishing gephyrin-positive (white) synaptic contacts (white arrowhead) on their dendrites. Scale bar: 10 μm. (See Suppl. Data for Fig. 2).

I: Double retrograde tracing using FG in the MS and CTB in the bilateral hippocampi, respectively, in wild-type mice (n=3).

J: Representative injection sites revealing green FG labeling in the MS and red CTB labeling in the hippocampus, respectively. The border of the MS and the hippocampal layers are labeled with white dashed lines. Scale bars: 500 μm.

K: Dual projecting neurons containing FG labeling (green) and CTB labeling (red) were frequently detected in the NI, the majority of which were relaxin-3 positive (white neurons, indicated by white arrowheads). Although retrograde tracers cannot fill the entire HIPP or MS, at least 50/135 HIPP-projecting neurons also projected to the MS, and the majority of these neurons (at least 34/50) was positive for relaxin-3. Scale bar: 50 μm.

To investigate, whether GABAergic NI fibers target the glutamatergic or cholinergic cells in the MS, we injected Cre-dependent AAV5 into the NI of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGluT2)-Cre (Fig. 2E) or choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-Cre (Fig. 2G) mice. These experiments revealed that relaxin-3 positive terminals of the NI frequently establish gephyrin-positive synapses on glutamatergic (at least 55%, Fig. 2F) and cholinergic (at least 8%, Fig. 2H) cells in the MS, indicating that NI projections can also inhibit the main extra-hippocampal excitatory input to hippocampal OLM cells.

In addition, we performed double retrograde tracing by injecting FG into the MS and CTB into the HIPP of WT mice bilaterally (Fig. 2I–J). We observed that many (at least 37%) of the individual NI GABAergic neurons that target HIPP also send axon collaterals to the MS (Fig. 2K). These data indicate that NI GABAergic neurons can synchronously inhibit HIPP OLM cells both directly in HIPP, and also indirectly by inhibition of their excitatory afferents in the MS.

NI GABAergic fibers in HIPP are rapidly activated by salient environmental stimuli in vivo

These anatomical and in vitro physiological data indicated that NI GABAergic neurons would be ideal to counterbalance the MS activation of OLM cells, which would permit fine-tuned regulation of pyramidal cell participation in memory formation. To test, whether NI GABAergic neurons indeed respond to sensory stimuli and behavioral state, we combined two-photon (2P) calcium imaging with behavioral monitoring in awake mice. We injected AAV2/1-EF1a-DIO-GCaMP6f into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice and implanted a chronic imaging window superficial to the dorsal CA1 of the HIPP (Fig. 3A). After recovery, water restriction and habituation to head-restraint, we engaged mice in two different behavioral paradigms, while imaging the fluorescent activity of GCaMP6f-positive NI boutons in the stratum oriens of the dorsal CA1 (Fig. 3B–C).

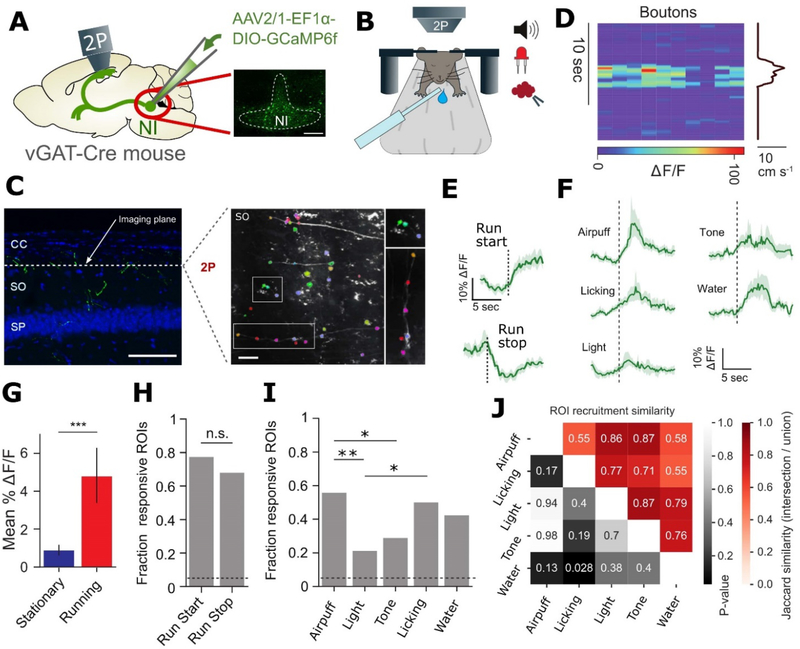

Figure 3: NI fibers are activated by relevant sensory stimuli in vivo.

A: Experimental design of the in vivo 2P calcium-imaging experiments. AAV2/1-EF1a-DIO-GCaMP6f was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice (n=5). After recovery, a cranial window implant was placed over the HIPP, and 2P imaging was performed. The inset on the right illustrates a representative virus injection site in the NI. Scale bar: 200 μm.

B: Schematic of 2P imaging and behavioral apparatus. Mice were head-fixed under a 2P microscope on a linear treadmill and permitted to move freely during random foraging experiments. During salience experiments, mice were immobilized and randomly presented with sensory stimuli (water, airpuffs, auditory tone, and light).

C: Left: laser scanning confocal microscopic image of GCaMP6f expressing fibers (green) along with cell nuclei (blue) in the dorsal CA1 region of the HIPP. Scale bar: 100 μm. CC: corpus callosum, SO: stratum oriens, SP: stratum pyramidale. Right: 2P field of view of GCaMP6f expressing NI GABAergic axons in hippocampal CA1. Exemplary fibers with regions of interest (colored polygons around axonal boutons) are enlarged on the right. Scale bar: 20 μm.

D: A representative random foraging experiment. Left: Fluorescence calcium signal in NI GABAergic axonal boutons; right: animal velocity. E: Running event-triggered signal averages during random foraging experiments (grand mean of ROIs + 99% CI, for ROIs with significant responses to each event, bootstrap test, n=3 mice).

F: Signal averages triggered by delivery of sensory stimuli during movement-restrained salience experiments (grand mean of ROIs + 99% CI, for ROIs with significant responses to each stimulus, bootstrap test, n=3 mice).

G: Average fluorescence during stationary and running periods differed significantly. We measured 54 responsive boutons (***: p<0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). H: Fraction of ROIs responsive to the onset and offset of running. Dashed line indicates the 0.05 chance level of the PETH bootstrap test. There was no statistically significant difference between the two data groups (n.s.: non-significant, p>0.05, Z-test). I: Fraction of ROIs responsive to sensory stimuli. Dashed line indicates the 0.05 chance level of the PSTH bootstrap test. Light stimuli recruited significantly fewer boutons than licking and air-puff, and auditory tones also recruited a smaller fraction of boutons compared to air-puff (*: p < 0.05, **: p <0.01 ***: p<0.001, Z-test between groups, Bonferroni-corrected p-value).

J: Measure of overlap between the set of ROIs with significant responses to each stimulus (Jaccard similarity values indicated in red boxes). Differences among the fractions of responding ROIs depending on different stimuli was tested using permutation test (p-values indicated in grayscale-colored boxes).

In the first experiment, the random foraging task, mice ran on a cue-less burlap belt in search of water rewards, which were delivered at 3 random locations on each lap. Bouton fluorescence was elevated during periods of running (Fig. 3D), consistent with previous observations of increased neural activity in the NI during hippocampal theta rhythm (32). To investigate how calcium dynamics in NI GABAergic axon terminals are modulated by locomotion state transitions, we examined GCaMP6f fluorescence changes in NI-GABAergic boutons in relation to the onset and offset of locomotion. We calculated peri-event time histograms (PETHs) aligned to running-start and running-stop events (Fig. 3E) and found that the majority of dynamic NI boutons were similarly modulated by the onset and offset of running (Fig. 3H).

In the second behavioral paradigm, the salience task, we explored whether discrete stimuli of various sensory modalities also modulate the activity of NI GABAergic axonal boutons in the HIPP, while the mouse was stationary (16, 42). The movements of mice were restrained while different sensory cues (aversive air-puffs, water rewards, auditory tones and light flashes) were randomly presented to them (Fig. 3B, F). We calculated peri-stimulus time histograms (PSTHs) and observed calcium responses in NI boutons to all types of stimuli. Salient stimuli with special valence such as aversive air-puff and water reward had particularly strong effects on bouton calcium dynamics (Fig. 3F), and also activated a larger fraction of NI boutons (Fig. 3I).

Finally, to determine the stimulus-dependent variability of the responses of NI terminals in the HIPP, we analyzed the Jaccard similarity of boutons in the salience experiments, based on their stimulus preference. Although all stimuli recruited an overlapping population of boutons, we detected some differences between the activated bouton populations (Fig. 3J).

NI GABAergic neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from areas processing salient environmental stimuli

Above mentioned data demonstrate that NI GABAergic neurons transmit information on salient environmental modalities from the brainstem to the HIPP. To directly identify upstream brain areas containing neurons that synaptically target the GABAergic neurons of NI, we used mono-trans-synaptic rabies tracing (43). We used Cre-dependent helper viruses and G-protein deleted rabies virus in vGAT-Cre mice (Supplementary Materials and Methods, Fig. 4A). These studies assessed the level of convergence onto NI GABAergic neurons, and thus the type of inputs that can fine-tune HIPP memory formation via the modulation of NI GABAergic cells. The specificity of the virus expression was tested in WT mice (Fig. 4B).

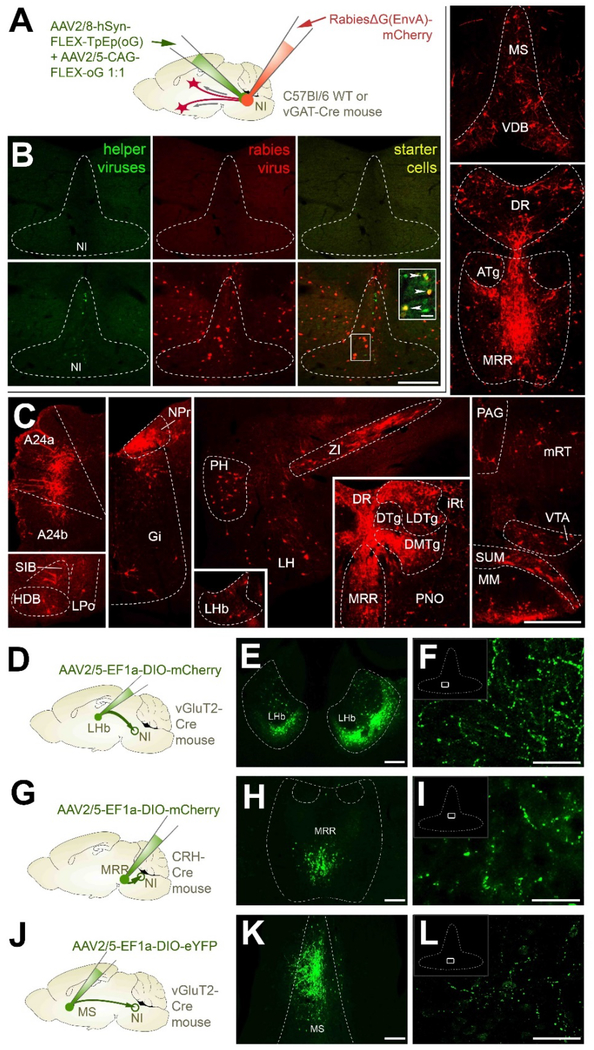

Figure 4: NI receives monosynaptic input from brain areas processing salient environmental stimuli.

A: A cocktail of helper viruses (AAV2/8-hSyn-FLEX-TpEp(oG) + AAV2/5-CAG-FLEX-oG in a ratio 1:1) was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre (n=3) or C57Bl/6 WT (n=2) mice, followed by an injection of RabiesΔG(EnvA)-mCherry 2 weeks later.

B: Representative injection sites show the lack of virus expression in WT mice, while there is a strong helper (green) and rabies (red) virus expression present in the NI of vGAT-Cre mice. Inset illustrates some starter neurons expressing both viruses, indicated by white arrowheads. Scale bar for large images: 200 μm. Scale bar for inset: 20 μm.

C: Confocal images illustrate neurons in different brain areas that establish synapses on NI GABAergic neurons. (For abbreviations see Suppl. Data for Fig. 4).

D: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry was injected into the LHb of vGluT2-Cre mice (n=2).

E: A representative injection site reveals mCherry-expression in the vGluT2-positive neurons of the bilateral LHb. Visualized in green for better visibility. Scale bar: 200 μm.

F: Fibers of LHb vGluT2-positive cells heavily innervate NI. Scale bar: 100 μm.

G: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry was injected into the MRR of CRH-Cre mice (n=3).

H: A representative injection site illustrates mCherry-expression in the CRH-positive neurons of the MRR. Visualized in green for better visibility. Scale bar: 200 μm.

I: Fibers of MRR CRH-positive neurons heavily innervate NI. Scale bar: 100 μm.

J: AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP was injected into the MS of vGluT2-Cre mice (n=2).

K: A representative injection site reveals eYFP-expression in the vGluT2-positive neurons of the MS.

Scale bar: 200 μm.

L: Fibers of MS vGluT2-positive neurons heavily innervate NI. Scale bar: 100 μm.

We detected an extensive convergence of inputs onto NI GABAergic neurons, with prominent synaptic inputs from several brain areas highly relevant to associated behaviors, including the prefrontal cortex, lateral habenula, zona incerta, mammillary areas, and raphe regions. These afferent regions play essential roles in movement, aversive or rewarding stimulus processing, and memory encoding (Fig. 4C, for details see Table S6). We did not find rabies labeled neurons in the HIPP, confirming the lack of direct output from HIPP to NI.

Rabies labeling revealed that NI GABAergic neurons are targeted by the lateral habenula (LHb; Fig. 4C), which plays a fundamental role in aversive behavior (44, 45). To confirm that the glutamatergic neurons of the LHb target the NI, we injected Cre-dependent AAV5 into the LHb of vGluT2-Cre mice (Fig. 4D–E) and detected strong fiber labeling in NI (Fig. 4F).

Rabies tracing also revealed that NI GABAergic neurons receive a strong monosynaptic input from the median raphe region (MRR, Fig. 4C, Table S6). HIPP memory formation is sensitive to stress, and NI neurons express functional corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor 1 that plays a role in stress processing (32, 46). MRR contains a small CRH-positive cell population (47). Injection of Cre-dependent AAV5 into the MRR of CRH-Cre mice (Fig. 4G–H) revealed that MRR is a prominent source of CRH signaling in the NI (Fig. 4I).

MS cholinergic neurons are known to transmit a rapid and precisely timed attention signal to cortical areas (23), while the activity of MS glutamatergic (vGluT2-positive) neurons is correlated with movement and HIPP theta rhythm (22, 24). We observed that virtually none of the NI projecting rabies-labeled MS neurons were positive for ChAT, parvalbumin or calbindin (Table S7). Injections of Cre-dependent AAV5 into the MS of ChAT-Cre mice confirmed the lack of cholinergic innervation of NI from MS.

Because vGluT2 is not detectable in neuronal cell bodies, we directly labeled MS vGluT2 positive glutamatergic cells, using injections of Cre-dependent AAV5 into the MS of vGluT2-Cre mice (Fig. 4J–K) and observed that MS glutamatergic neurons provide a strong input into the NI (Fig. 4L).

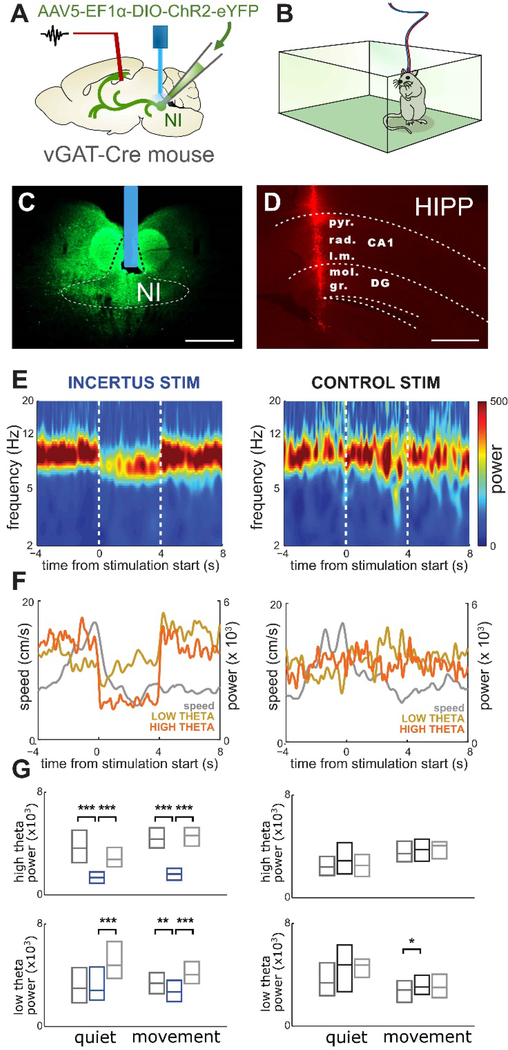

NI GABAergic cells regulate hippocampal network activity

HIPP theta activity is essential for contextual memory formation (25, 48) and typical during exploration (49, 50), therefore, we investigated the effects of NI GABAergic neurons on HIPP theta activity. We injected ChR2-containing Cre-dependent AAV5 into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice. Later, we implanted an optic fiber over the NI (Fig. S4A) and placed a multichannel linear probe into the dorsal HIPP (Fig. 5A–D). After recovery and habituation, HIPP rhythmic activities were recorded in an open field or on a linear track, where mice could behave freely (Fig. 5B). Blue light stimulation was triggered by the experimenter during every recording condition, while electrophysiological activity in HIPP was continuously recorded.

Figure 5: NI regulates HIPP network activity.

A: Experimental design of optogenetic in vivo experiments in freely-moving mice. AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was injected into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice (n=5), and an optic fiber was implanted over the NI, with a linear probe implanted into the dorsal CA1.

B: Five (5) days later, mice were placed into an open field, and their behavior was monitored under freely-moving conditions. NI was stimulated with blue laser pulses, and concurrent hippocampal network activity was recorded.

C: A representative injection site illustrating AAV2/5-EF1a-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (ChR2) expression (green) and the position of the implanted optic fiber (blue) in the NI of a vGAT-Cre mouse. Scale bar: 500 μm.

D: A representative coronal section from the dorsal HIPP CA1 and dentate gyrus (DG) regions illustrating the location of the linear probe. Scale bars: 500 μm.

E: Theta power was reduced by optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic cells in ChR2-expressing mice, as revealed by the time-frequency decomposition of pyramidal LFP with continuous wavelet transform. Frequency range of 1–20 Hz is shown, for expanded scale, see Fig. S5C. Averages of all NI GABAergic neurons (left) and control (right) stimulation sessions in one representative mouse during running are shown. Boundaries of the stimulation periods are marked with white dashed lines.

F: Separate analysis of NI stimulation on low theta (5–8 Hz, yellow graph) and high theta (8–12 Hz, orange graph) band power with concurrent speed (grey graph). NI GABAergic cell stimulation was controlled manually, while mice were running on a linear track, and tests started when mice started to demonstrate active exploratory behaviour. NI stimulation strongly reduced high theta band power and also moderately reduced low theta band power, independently from the speed of the animal (left). This effect was absent in control stimulations (left). The mean of all stimulation sessions in 4 mice are shown.

G: High (top) and low (bottom) theta power during quiet (speed < 4 cm/s) and movement (speed > 4 cm/s) periods of stimulation sessions. Theta power during 4s stimulation versus 4s pre- and post-stimulation segments was compared. Medians and interquartile ranges are shown. The instant power values were averaged per stimulation sessions. Statistical difference between the segments was tested by two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001).

As revealed by wavelet analysis of the HIPP local field potentials (LFP), stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons significantly decreased the power of HIPP theta activity (Fig. 5E–G, Fig. S5A–D), while no such effect occurred after introduction of light into a dummy fiber implanted in the same mice (Supplementary Materials and Methods, Fig. 5E–G, Fig. S5C–D). The effect was most prominent in the high theta range (8–12Hz), less in the low theta range (5–8Hz), while it was generally stronger when mice actively explored their environment (Fig. 5G). Stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons also reduced HIPP theta power during REM sleep (Fig. S5D–E). Current source density analysis revealed a prominent effect on the magnitude of apical dendritic sinks and sources, excluding the possibility of general silencing of CA1, instead implying a stimulus-triggered alteration of excitation – inhibition balance (Fig. S5F–I). Importantly, none of these effects were observed when we stimulated the NI GABAergic neurons in urethane-anaesthetized mice.

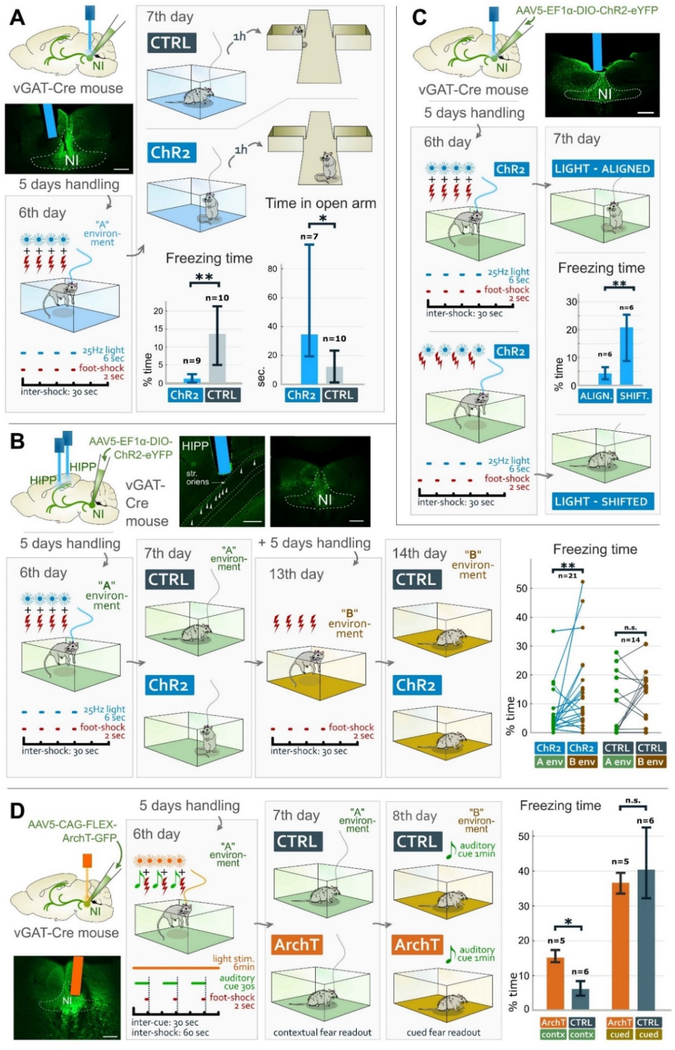

NI GABAergic neurons bi-directionally regulate hippocampus-dependent contextual memory formation

Our findings above indicated that NI GABAergic neurons can integrate behavioral modalities from several key brain areas and are activated by salient environmental inputs, while they inhibit HIPP OLM cells both directly and indirectly. These findings suggest that this brainstem projection is ideally suited to provide the sub-cortical inhibition of these HIPP SOM-positive dendrite-targeting neurons for balancing the selection of HIPP pyramidal cells that participate in memory formation.

To test this possibility, first we injected ChR2-containing Cre-dependent AAV5 (ChR2-mice) or control Cre-dependent AAV5 (CTRL-mice) into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice and implanted an optic fiber over the NI (Fig. 6A, Fig. S4A). After handling, mice were placed into a new multisensory context (environment “A”), where they received four foot-shocks and light stimulation of NI precisely aligned to foot-shocks (Supplementary Materials and Methods, Fig. 6A). All mice displayed equally strong immediate reactions to foot-shocks. 24 h later, mice were placed into the same environment “A”, where CTRL-mice displayed strong freezing behavior as expected, while ChR2-mice displayed almost no freezing behavior (Fig. 6A). An elevated plus-maze test, 1 hour later, revealed significantly lower anxiety levels in ChR2-mice compared to CTRL-mice (Fig. 6A). These findings indicated that contextual fear memory formation can be severely impaired or blocked if NI GABAergic neurons are strongly activated precisely at the time of US presentation.

Figure 6: NI regulates the establishment of contextual fear memories.

A: Experimental design of contextual fear conditioning experiments with optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons. ChR2 expressing mice spent significantly less time freezing in the environment ”A” and significantly more time in the open arm of the elevated plus maze than CTRL mice. Confocal image represents one of the injection sites to label NI GABAergic neurons and the blue area represents the position of the optic fiber. Scale bar: 200 μm. Medians and interquartile ranges are shown on the graphs. (For statistical details see Suppl. Data for Fig. 6).

B: Experimental design of contextual fear conditioning experiments with light stimulation of NI GABAergic fibers in the bilateral HIPP. Illustration of the two sets of experiments in environment “A” and “B” with and without light stimulation of the HIPP fibers of NI GABAergic neurons. Pairwise comparison reveals that ChR2 expressing mice displayed significantly more freezing in environment ”B”, where they received no light stimulation, than in environment ”A”. This was not observed in CTRL mice. Insets illustrate a representative injection site and optic fiber localization; white arrowheads mark NI GABAergic fibers in the HIPP stratum oriens. Scale bars: 200 μm. Data from individual mice are shown in the graphs. (For statistical details see Suppl. Data for Fig. 6).

C: Experimental design of contextual fear conditioning experiments with optogenetic stimulation of NI GABAergic neurons “aligned” to or 15 seconds “shifted” after foot-shocks. “Light-aligned” mice displayed significantly less freezing than “Light-shifted” mice, demonstrating the importance of timing. The inset illustrates a representative injection site and optic fiber localization. Scale bar: 200 μm. Medians and interquartile ranges are shown on the graphs. (For statistical details see Suppl. Data for Fig. 6).

D: Experimental design of delayed cued fear conditioning experiments with optogenetic inhibition of NI GABAergic neurons. Light inhibition of NI GABAergic neurons caused significantly stronger contextual freezing behavior in ArchT-mice in environment ”A” compared to CTRL mice. However, there was no difference in HIPP-independent cued fear freezing levels between the two groups in environment ”B”. The inset illustrates a representative injection site and optic fiber localization. Scale bar: 200 μm. Medians and interquartile ranges are shown on the graphs. (For statistical details see Suppl. Data for Fig. 6).

In an additional control experiment, we conducted the same contextual fear conditioning experiment with the same cohorts of ChR2- and CTRL-mice one week later, in a different environment “B” (Fig. S6A) without light stimulations. On the second day of the experiment, both ChR2- and CTRL-mice displayed high freezing behavior (Fig. S6A–B), confirming that ChR2-mice could also display appropriate fear behavior.

To confirm that NI GABAergic cells act directly on HIPP SOM-positive cells, we created a second cohort of ChR2- and CTRL-mice as described above (Fig. 6B). However here, optic fibers were implanted bilaterally above the dorsal HIPP (Fig. 6B, Fig. S4A–B). In similar contextual fear conditioning experiments described above, ChR2-mice again displayed significantly lower freezing levels in environment “A”, where they received NI light stimulation during foot-shocks, than in environment “B”, where NI was not stimulated (Fig. 6B). This effect was absent in CTRL mice (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that dorsal HIPP fibers of NI GABAergic neurons can inhibit the formation of contextual memory directly in the HIPP.

The balancing of the selection of pyramidal cells that associate US with environmental context should be timed precisely during US presentation. To test the importance of timing, we injected ChR2-containing Cre-dependent AAV5 into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice and implanted an optic fiber over the NI (Fig. 6C, Fig. S4A). Mice were divided into two groups: one group received NI GABAergic neuron stimulation aligned to foot-shocks as described above (“light-aligned-mice”), while a second group received light stimulation exactly between foot-shocks (i.e. 15 seconds after each foot-shock, “light-shifted-mice”, Fig. 6C). “Light-shifted-mice” displayed significantly higher freezing levels compared to “light-aligned-mice”, indicating that activation of NI GABAergic neurons needs to occur precisely during US presentation to be effective (Fig. 6C).

Finally, we investigated whether inhibition of NI GABAergic neurons during contextual fear conditioning induced opposite effects, i.e. whether it can create inadequately strong fear. We injected archaerhodopsinT-3 (ArchT 3.0)-containing Cre-dependent AAV5 (ArchT-mice) or control Cre-dependent AAV5 (CTRL-mice) into the NI of vGAT-Cre mice and implanted an optic fiber over the NI (Fig. 6D, Fig. S3D and Fig. S4A). After handling, mice were tested in a delay cued fear conditioning paradigm. First, we placed mice into environment “A”, where they received three auditory tones, at the end of which mice received foot-shocks. NI received a constant yellow light during the experiments. 24 h later, mice were placed back into environment “A” to test their hippocampus-dependent contextual fear memories. We observed that ArchT-mice displayed significantly stronger freezing behavior than CTRL-mice (Fig. 6D). The auditory cue dependent fear component of established fear memories is known to be hippocampus-independent (51). Therefore, on the next day, we placed these mice into a different neutral environment “B” and presented them with the auditory cues (Fig. 6D). At this time, however, we found no difference between the freezing levels of the two groups, further suggesting that the effect of NI GABAergic neurons on contextual memory formation was hippocampus-dependent.

Discussion

Encoding of episodic memories is essential for the survival of animals. HIPP pyramidal neurons of the dorsal CA1 region play a key role in this process (1, 25, 52), by pairing multisensory contextual information with direct sensory-related inputs (e.g. an US) at the cellular level, via long-term synaptic plasticity mechanisms (8, 10, 15). However, if too many pyramidal neurons receive the same direct sensory-related inputs, information pairing is not specific enough and the memory trace will be lost (16). Therefore, only a subpopulation of pyramidal neurons participate in this process by forming cell-assemblies that encode memory engrams (11, 15), while the direct sensory-related input must be excluded from most of the pyramidal neurons (16).

HIPP SOM-positive OLM neurons selectively inhibit the distal dendrites of pyramidal neurons to filter out direct sensory-related excitatory inputs from the entorhinal cortex (3, 16, 22). Upon salient environmental stimuli, OLM cells are activated by glutamatergic and cholinergic inputs from the MS (3, 16, 19–22), therefore dendrite-targeting OLM cells can efficiently block direct sensory-related inputs to most pyramidal cells at the time of memory formation, thereby leaving only a subpopulation of pyramidal neurons to form engrams.

However, the selection of these pyramidal neurons must be precisely balanced. We hypothesized that dorsal CA1 dendrite-targeting OLM interneurons should also be precisely inhibited in time based on sub-cortical information, because otherwise, under-recruitment of pyramidal neurons will lead to unstable engrams (17, 25, 52). We discovered that NI GABAergic neurons are well suited to counter-balance the activation of OLM cells in a time- and sensory stimulus-dependent manner.

We demonstrated that NI GABAergic neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from several brain areas that process salient environmental stimuli and that they are activated rapidly by such stimuli in vivo. We revealed that these NI GABAergic neurons provide a selective, direct inhibition of HIPP SOM-positive interneurons, the vast majority of which CA1 fibers originate from dendrite-targeting OLM interneurons (16, 18). Although other types of HIPP neurons have little contribution to the local SOM-positive innervation of the CA1 area, some SOM-positive bistratified interneurons may also support the inhibition of pyramidal cell dendrites, in addition to extra-hippocampal projecting GABAergic neurons, the rare local collaterals of which also target pyramidal cell dendrites (53).

MS cholinergic cells release GABA, immediately followed by a strong cholinergic excitatory component (54), which results in an effective net activation of OLM cells (16). Here we revealed that medial septal glutamatergic and cholinergic excitatory inputs to OLM neurons are also inhibited by NI GABAergic neurons simultaneously, which facilitates the effective and precisely timed inhibition of hippocampal OLM cells. We also demonstrated that many of these direct and indirect inhibitory actions are provided by collaterals of the same NI GABAergic neurons, further facilitating a highly synchronous inhibition.

Although OLM cells in intermediate and ventral HIPP seem to regulate memory formation differently (17), previous studies agree that direct inhibition of dorsal CA1 OLM neurons resulted in weaker memory formation (16, 17). Indeed, we found that dorsal CA1 OLM neurons can be inhibited by activating brainstem NI GABAergic neurons. Our behavioral data revealed that the precisely-timed activation of NI GABAergic neurons could lead to an almost complete inhibition of the formation of contextual fear memories.

In contrast, NI-lesioned rats display pathologically strong memory formation, indicated by impaired fear extinction and increased fear generalization (55, 56). In this regard, we also observed stronger contextual fear memory formation after inhibition of GABAergic NI neurons.

We described that NI GABAergic neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from several brain areas that process salient environmental stimuli and our analysis of our 2P calcium imaging data revealed that different environmental inputs activated different fractions of NI fibers. Emotionally more salient inputs were more effective. Furthermore, our Jaccard similarity analysis suggested that NI fibers may be activated by different sensory stimuli. Previous studies have also shown heterogeneity amongst the NI cells based on their activity patterns or based on their CRH receptor / relaxin-3 content (30, 32). Therefore, one may speculate that different subset of NI GABAergic neurons could enforce the disinhibition of a different subset of pyramidal neurons, leading to the selection of different sets of memory-encoding pyramidal cell populations, which would be beneficial to encode different contextual memories more specifically.

The activity of medial septal glutamatergic neurons is positively correlated with the running speed of the animal and with the frequency of hippocampal theta rhythm (22, 24, 57). NI neurons also display firing phase-locked to hippocampal theta (32, 58, 59). Our results reveal that MS glutamatergic neurons innervate the NI, and that the activity of NI GABAergic fibers is elevated during running, active exploration and new episodic memory formation. Therefore, MS glutamatergic neurons may support the phase-locking of NI GABAergic neurons to HIPP theta rhythm.

We observed that activation of NI GABAergic neurons partly inhibited and reorganized HIPP theta rhythmic activity, which rhythm is known to be essential for episodic memory formation (25), further suggesting a role of NI GABAergic neurons in memory formation. This effect on theta activity may be facilitated by one of the different populations of septo-hippocampal parvalbumin-positive GABAergic neurons (60–63). Although it is unclear, which one of them receives GABAergic synapses from NI, some of them express metabotropic relaxin-3 receptors and may be inhibited by NI (64, 65). Different types of MS parvalbumin cells target different HIPP interneurons in a rhythmic fashion and they mostly target HIPP basket cells that are known to be fundamental in modulating HIPP theta rhythms (63, 66–68).

In the rat, NI GABAergic neurons that express CRH-R1 are activated by different stressors (29, 32, 33, 56). Our results demonstrate that NI GABAergic neurons receive inputs from several brain areas, some of them related to stress regulation, and amongst which, the projection from CRH-expressing neurons of the median raphe region, was previously unknown. Therefore, CRH-dependent activation of NI GABAergic neurons might contribute to impaired episodic memory formation observed under stressful conditions (46, 69).

Pathological neurodegeneration of NI GABAergic neurons may result in hyperthymesia-like symptoms, in which the unnecessarily encoded detailed memories of everyday life cause cognitive problems in patients (70, 71). NI GABAergic neuron dysfunction may also contribute to general anxiety-like syndromes or post-traumatic stress disorders, where pathologically strong episodic memory formation is present. On the other hand, over-activity of NI GABAergic neurons may lead to dementia-like disorders.

An important physiological role of NI GABAergic neurons may be the fine-tuning of the selection of memory-encoding pyramidal cells, based on the relevance and/or modality of environmental inputs. NI GABAergic neurons may also help filter out non-relevant everyday experiences, to which animals have already accommodated, by regulating the population sparsity of memory-encoding dorsal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Our data represent an unexpectedly specific role of an ascending inhibitory pathway from a brainstem nucleus in memory encoding.

Methods Summary

Ethical considerations and used mouse strains

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Ethical Codex and the Hungarian Act of Animal Care and Experimentation guidelines (40/2013, II.14), which are in concert with the European Communities Council Directive of September 22, 2010 (2010/63/EU). All two-photon (2P) imaging experiments were conducted in accordance with the United States of America, National Institutes of Health guidelines and with the approval of the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The following mouse strains were used in the experiments: C57Bl/6J wild type, ChAT-iRES-Cre, CRH-iRES-Cre, vGAT-iRES-Cre, vGAT-iRES-Cre::Gt(ROSA26)Sor-CAG/tdTomato, vGluT2-iRES-Cre (72), GlyT2-iRES-Cre and SOM-iRES-Cre. We used at least 6 weeks-old mice from both genders in our experiments.

Stereotaxic surgeries for viral gene transfer and retrograde tracing

Mice were deeply anesthetized and were then mounted and microinjected using a stereotaxic frame. We used one of the following viruses: AAV2/1-EF1a-DIO-GCaMP6f; AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP; AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry; AAV2/5-CAG-FLEX-ArchT-GFP; AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP. For retrograde tracing experiments we injected 2% FluoroGold or 0.5% Cholera toxin B subunit into the target areas. The coordinates for the injections were defined by a stereotaxic atlas (73).

Hippocampal cranial window implants for two-photon imaging experiments

We implanted an imaging window/head-post as described previously (16). Briefly, under anesthesia, a 3-mm diameter craniotomy was made in the exposed skull over the left dorsal hippocampus and the underlying cortex was slowly aspirated. A custom-made sterilized cylindrical steel imaging cannula with a glass cover slip window (3-mm diameter × 1.5-mm height, as described in (42)) was inserted into the craniotomy and was cemented to the skull. Analgesia was administered during and after the procedure for three days.

Optic fiber implantations for behavioral experiments

For behavioral experiments, optic fibers were implanted into the brain. Their positions are illustrated in Fig. S4A–B. After the surgeries, mice received meloxicam analgesia, and were placed into separate cages until experiments or perfusions.

Stereotaxic surgeries for electrophysiological recordings in freely moving mice

AAV2/5-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-YFP transfected vGAT-IRES-Cre male mice received optical fibers above their nucleus incertus and a multichannel (16 or 32) linear type silicon probe into the dorsal hippocampus. Stainless steel wires above the cerebellum served as reference for the electrophysiological recordings. An additional optical fiber with the tip in the dental acrylate above the skull was used for control illumination sessions. Analgesia was administered during and after the procedures.

Mono-trans-synaptic rabies tracing

We used the monosynaptic rabies tracing technique published by Wickersham et al. (43). Briefly, C57Bl/6 and vGAT-Cre mice were prepared for stereotaxic surgeries as described above, and 30 nl of the 1:1 mixture of the following viruses was injected into the NI: AAV2/8-hSyn-FLEX-TVA-p2A-eGFP-p2A-oG and AAV2/5-CAG-FLEX-oG. These viruses contain an upgraded version of the rabies glycoprotein (oG) that has increased trans-synaptic labeling potential (74). After 2–3 weeks of survival, mice were injected with the genetically modified Rabies(ΔG)-EnvA-mCherry at the same coordinates. After 10 days of survival, mice were prepared for perfusions.

Antibodies and perfusions

The list and specifications of the primary and secondary antibodies used can be found in Supplementary Table 1–3. Combinations of the used primary and secondary antibodies in the different experiments are listed in Supplementary Table 4–5. Mice were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline solution for 2 min followed by 4% freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde solution; or with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) for 2 min. After perfusion, brains were removed from the skull, and were immersion-fixed in 4% PFA with or without 0.2% glutaraldehyde (GA) for 2 h. Brains were cut into 50 or 60 μm sections using a vibrating microtome.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry and laser-scanning confocal microscopy

Perfusion-fixed sections were washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) and then incubated in a mixture of primary antibodies for 48–72 h. This was followed by extensive washes in tris buffered saline (TBS), and incubation in the mixture of appropriate secondary antibodies overnight. For visualizing cell layers in the hippocampus, nuclear counterstaining was done on forebrain sections using Draq5 according to the manufacturer`s protocol. Following this, sections were washed in TBS and PB, dried on slides and covered with Aquamount (BDH Chemicals Ltd) or with Fluoromount-G Mounting Medium (Invitrogen). Sections were evaluated using a Nikon A1R confocal laser-scanning microscope system built on a Ti-E inverted microscope operated by NIS-Elements AR 4.3 software. Regions of interests were reconstructed in z-stacks. In case of the monosynaptic rabies tracing experiments, coronal sections were prepared from the whole brain for confocal laser-scanning microscopy, and labeled cells were scanned using a Nikon Ni-E C2+ confocal system.

Immunogold-immunoperoxidase double labeling and electron microscopy

For synaptic detection of GABAA-receptor γ2 subunit, sections were pepsin-treated mildly and were blocked in 1% HSA in TBS, followed by incubation in a mixture of primary antibodies. After washes in TBS, sections were incubated in blocking solution and in mixtures of secondary antibody solutions overnight. After washes in TBS, the sections were treated with 2% glutaraldehyde. The immunoperoxidase reaction was developed using 3–3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Immunogold particles were silver-enhanced. The sections were contrasted using osmium tetroxide solution, dehydrated and embedded in Durcupan. 70–100 nm serial sections were prepared using an ultramicrotome and documented in electron microscope.

Silver-gold intensified and nickel-intensified immunoperoxidase double labeling (SI-DAB/DAB-Ni)

Perfusions, sectioning and incubations of sections in primary antibody solutions were performed as described above. The SI-DAB reaction was followed by subsequent washes and incubation in secondary antibody solutions. Labeling was developed using ammonium nickel sulphate-intensified 3–3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB-Ni) and intensified with silver-gold (SI/DAB) as described in detail in Dobó et al. (75). After washes in TBS, sections were blocked in 1% HSA and incubated in primary antibody solutions for the second DAB-Ni reaction. This was followed by incubation with ImmPRESS secondary antibody solutions overnight. The second immunoperoxidase reaction was developed by DAB-Ni, resulting in a homogenous deposit, which was clearly distinguishable from the silver-gold intensified SI-DAB at the electron microscopic level (75). Further dehydration, contrasting and processing of the sections for electron microscopy was performed as described above.

In vitro slice preparation

In all slice studies, brains were removed and placed into an ice-cold cutting solution, which had been bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 (carbogen gas) for at least 30 min before use. Then 300–450 μm horizontal slices of ventral hippocampi or 300 μm coronal brainstem slices containing the nucleus incertus were cut using a vibrating microtome. After acute slice preparation, slices were placed in an interface-type holding chamber for recovery (76). This chamber contained standard artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 35°C that was gradually cooled to room temperature, and saturated with carbogen gas.

Intracellular recordings

To record GABAergic currents, membrane potential was clamped far (~0 mV) from GABA reversal potential. In case of intracellular recordings, fast glutamatergic transmission was blocked by adding the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-receptor antagonist NBQX and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor antagonist AP-5 to the recording solution. To test GABAA-receptor dependent synaptic transmission, we administered the GABAA-receptor antagonist gabazine into the ACSF. All drugs were administered from stock solutions via pipettes into the ACSF containing superfusion system. For ChR2 illumination, we used a blue laser diode attached to a single optic fiber positioned above the hippocampal slice. For ArchT illumination, we used a red laser diode with optic fiber positioned above NI. Cells recorded in current clamp configuration were depolarized above firing threshold to test the effectivity of ArchT mediated inhibition on action potential generation.

In vivo two-photon calcium imaging

Calcium imaging in head-fixed, behaving mice was performed using a two-photon microscope equipped with an 8 kHZ resonant scanner and a Ti:Sapphire laser tuned to 920 nm. For image acquisition we used a Nikon 40× NIR Apo water-immersion objective (0.8 NA, 3.5 mm WD) coupled to a piezo-electric crystal. Fluorescent signals were collected by a GaAsP photomultiplier tube.

Behavior for two-photon calcium imaging

For the in vivo head-fixed 2P calcium-imaging experiments, behavioral training of the mice was started three days after implantation surgery. Mice were hand habituated, water restricted (>90 % of their pre-deprivation body weight) and trained for 5–7 days to run on a 2 m-long cue-less burlap belt on a treadmill for water rewards, while being head-fixed. Mice were also habituated to the 2P setup and the scanner and shutter sounds prior to the actual 2P imaging experiments. The treadmill was equipped with a lick-port for water delivery and lick detection. Locomotion was recorded by tracking the rotation of the treadmill wheel using an optical rotary encoder. Stimulus presentation and behavioral read-out were driven by microcontroller systems, using custom made electronics. During random foraging experiments three water rewards were presented per lap in random locations, while mice were running on a cue-less burlap belt. In salience experiments, discrete stimuli were presented as described (42), with slight modifications. Stimuli were repeated 10× for each modality in a pseudorandom order during one experiment. The acquired 2P imaging data were pre-processed for further analysis using the SIMA software package (77). Motion correction and extraction of dynamic GCaMP6f fluorescent signals were conducted as described (78). Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn manually over the time-averages of motion corrected time-series to isolate the bouton calcium signals of GCaMP6f-expressing axons.

Optogenetics and contextual fear conditioning (CFC)

After optic fiber implantations, mice received 5 days of handling. On the 6th day, mice were placed into the first environmental context (environment “A”) in a plexiglass shock chamber, where they received 4 foot-shocks. Optogenetic stimulation was precisely aligned with the shocks, starting 2 seconds before shock onset and finishing 2 seconds after shock offset. For the “ChR2-shifted” group, this laser stimulation was shifted by 15 seconds after shock onset. On the 7th day, mice were placed back into the first environment for 3 minutes to record freezing behavior. This was followed by 5 days of extensive handling to achieve full fear extinction that reset freezing behavior to a normal baseline. On the 13th day, mice were placed into the second environmental context (environment “B”), composed of another set of cues. Baseline freezing levels were recorded for 3 minutes, followed by 4 shocks without optogenetic stimulation. 24 h later, freezing behavior was recorded in the second environment for 3 minutes. The behavior of the mice was recorded and freezing behavior was analyzed manually. Freezing behavior was recorded when mice displayed only respiration-related movements for at least 2 seconds.

Optogenetics and delay cued fear conditioning (CuedFC)

After optic fiber implantations, mice received 5 days of handling. On the 6th day, mice were placed into the first environmental context (environment “A”) in a plexiglass shocking chamber, where they received 3 shocks paired with an auditory cue. The footshocks and the auditory cues were co-terminated each time. During the experiment, lasting 6 minutes, mice received a continuous yellow laser light illumination. On the 7th day, mice were placed back into the first environment for 3 minutes to record freezing behavior related to the contextual fear memories. 24 h later, on the 8th day, mice were placed into a second environmental context (environment “B”). Here, mice were presented with the auditory cue for 1 minute to record freezing behavior related to the cued fear memories.

Elevated plus maze (EPM) after optogenetic CFC

One hour after freezing behavior assessment in the first environment (7th day) we placed the mice into an EPM to test their anxiety levels. The cross-shaped EPM apparatus consisted of two open arms with no walls and two closed arms and was on a pedestal 50 cm above floor level (Fig. 6A). The behavior of the mice was recorded camcorder and evaluated using an automated system (Noldus Ethovision 10.0; Noldus Interactive Technologies). Behavior was measured as total time in the open and closed arms.

In vivo electrophysiological recordings in freely behaving mice

Electrophysiological recordings commenced 7-day after surgery and habituation to connections to the head-stage. The signal from the silicon probe was multiplexed and sampled at 20 kHz. The movement of the mouse was tracked by a marker-based, high speed 4-camera motion capture system and reconstructed in 3D. After home cage recording, mice were placed into an open arena and into a linear track. Recordings were repeated 1–7 days later. In each recording situation, blue light stimulation was triggered manually by the experimenter. Mice were recorded in 3 – 9 sessions for 2 – 5 weeks. Then mice were processed for histological verification of the viral transduction zone and implantation. The analysis was performed in MATLAB environment by custom-written functions and scripts. Time-frequency decomposition of pyramidal LFP with continuous wavelet transform (79) and subsequent bias correction of spectral power (80) was used to calculate instant power.

Data and code availability

Data generated and analysed during the current study are presented in the manuscript or in the Supplementary Materials file, while additional datasets and custom written codes for in vivo electrophysiological recordings, 2P-imaging and data analysis are available from the following links: https://figshare.com/s/9fb345fc23ac2ac94fcd and https://figshare.com/s/5b0c6be2431caf10272b

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Thomas Reardon (CTRL-Labs, NY) for the AAV2/1-EF1a-DIO-GCaMP6f virus (16) used in this study and Dr Darcy S. Peterka and Luke Hammond (ZI Cellular Imaging, CU, New York) for providing microscopy support. We thank Dr Dóra Zelena for her help with CRH-Cre mice. We thank Dr Sébastien Arthaud (INSERM, Lyon, France) for his help with vGluT2-Cre mice. We thank Prof Hanns Ulrich Zeilhofer (UZ, Zürich) for his help with GlyT2-IRES-Cre mice. We thank Prof Josh Huang (CSHL, New York) for his help with SOM-IRES-Cre mice. Viruses used in this study are subject to a material transfer agreement. We thank Dr. László Barna, the Nikon Microscopy Center at IEM, Nikon Austria GmbH and Auro-Science Consulting Ltd. for technical support for fluorescent imaging. We thank Dr. Kornél Demeter and the Behavior Studies Unit of the IEM-HAS for the support for behavioural experiments. We thank Dr. Zsuzsanna Erdélyi and Dr. Ferenc Erdélyi and the staff of the Animal Facility and the Medical Gene Technology Unit of the IEM-HAS for their expert technical help with the breeding and genotyping of the several mouse strains used in this study. We thank Zsuzsanna Bardóczi, Zsuzsanna Hajós, Emőke Szépné Simon, Katalin Lengyel, Márton Mayer, Nándor Kriczky for their help with experiments and Andrea Kriczky, Katalin Iványi and Győző Goda for other assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2011-ADG-294313, SERRACO), the National Research, Development and Innovation Office, Hungary (OTKA K119521, OTKA K115441, OTKA K109790, OTKA KH124345 and VKSZ_14–1-2O15–0155), the National Institutes of Health, USA (NS030549), the Human Brain Project, EU (EU H2020 720270) and the Hungarian Brain Research Program (2017–1.2.1-NKP-2017–00002). B.P. is supported by UNKP-16–2-13 and D.S. is supported by the UNKP-16–3-IV New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities, Hungary. A.S was supported by the ÚNKP-17–3-III-SE-9 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities. A.L. is supported by NIMH 1R01MH100631, 1U19NS104590, 1R01NS094668, and the Zegar Family Foundation Award.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability

Viruses AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-eYFP, AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-mCherry, AAV2/5-CAG-FLEX-ArchT-GFP were obtained under an MTA with the UNC Vector Core. Virus AAV2/5-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was obtained under an MTA with the Penn Vector Core. Viruses AAV2/8-hSyn-FLEX-TVA-p2A-eGFP-p2A-oG, AAV2/5-CAG-FLEX-oG, Rabies(ΔG)-EnvA-mCherry were obtained under an MTA with the Salk GT3 Vector Core. The GlyT2-iRES-Cre mouse strain was obtained under an MTA with the University of Zürich.

References

- 1.Eichenbaum HB, The hippocampus and declarative memory: cognitive mechanisms and neural codes. Behav. Brain Res 127, 199–207 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen P, The Hippocampus Book (Oxford University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haam J, Zhou J, Cui G, Yakel JL, Septal cholinergic neurons gate hippocampal output to entorhinal cortex via oriens lacunosum moleculare interneurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115, 1886–1895 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitamura T et al. , Entorhinal cortical ocean cells encode specific contexts and drive context-specific fear memory. Neuron. 87, 1317–1331 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lisman JE, Relating hippocampal circuitry to function: Recall of memory sequences by reciprocal dentate-CA3 interactions. Neuron. 22, 233–242 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suh J, Rivest AJ, Nakashiba T, Tominaga T, Tonegawa S, Entorhinal cortex layer III input to the hippocampus is crucial for temporal association memory. Science (80-. ). 1415, 1415–1421 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura T et al. , Island cells control temporal association memory. Science (80-. ). 343, 896–901 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bittner KC et al. , Conjunctive input processing drives feature selectivity in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat. Neurosci 18, 1133–1142 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bittner KC, Milstein AD, Grienberger C, Romani S, Magee JC, Behavioral time scale synaptic plasticity underlies CA1 place fields. Science (80-. ). 357, 1033–1036 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudman JT, Tsay D, Siegelbaum SA, A role for synaptic inputs at distal dendrites: instructive signals for hippocampal long-term plasticity. Neuron. 56, 866–879 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy DS et al. , Distinct neural circuits for the formation and retrieval of episodic memories. Cell. 170, 1000–1012.e19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maren S, Fanselow MS, Electrolytic lesions of the fimbria/fornix, dorsal hippocampus, or entorhinal cortex produce anterograde deficits in contextual fear conditioning in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 149, 142–149 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kesner RP, Behavioral functions of the CA3 subregion of the hippocampus. Learn. Mem 14, 771–781 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maren S, Phan KL, Liberzon I, The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 14, 417–428 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka KZ et al. , The hippocampal engram maps experience but not place. Science (80-. ). 361, 392–397 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovett-Barron M et al. , Dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus supports fear learning. Science (80-. ). 1, 857–864 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siwani S et al. , OLMα2 Cells Bidirectionally Modulate Learning. Neuron. 99, 404–412 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royer S et al. , Control of timing, rate and bursts of hippocampal place cells by dendritic and somatic inhibition. Nat. Neurosci 15, 769–775 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakauchi S, Brennan RJ, Boulter J, Sumikawa K, Nicotine gates long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region via the activation of α2* nicotinic ACh receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci 25, 2666–2681 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia Y, Yamazaki Y, Nakauchi S, Sumikawa K, α2 Nicotine receptors function as a molecular switch to continuously excite a subset of interneurons in rat hippocampal circuits. Eur. J. Neurosci 29, 1588–1603 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leão RN et al. , OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat. Neurosci 15, 1524–1530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuhrmann F et al. , Locomotion, theta oscillations, and the speed-correlated firing of hippocampal neurons are controlled by a medial septal glutamatergic circuit. Neuron. 86, 1253–1264 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A, Central cholinergic neurons are rapidly recruited by reinforcement feedback. Cell. 162, 1155–1168 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justus D et al. , Glutamatergic synaptic integration of locomotion speed via septoentorhinal projections. Nat. Publ. Gr (2016), doi: 10.1038/nn.4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misane I, Kruis A, Pieneman AW, Ögren SO, Stiedl O, GABA-A receptor activation in the CA1 area of the dorsal hippocampus impairs consolidation of conditioned contextual fear in C57BL/6J mice. Behav. Brain Res 238, 160–169 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto M, Swanson LW, Canteras NS, Connections of the nucleus incertus. J. Comp. Neurol 438, 86–122 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma S et al. , Relaxin-3 in GABA projection neurons of nucleus incertus suggests widespread influence on forebrain circuits via G-protein-coupled receptor-135 in the rat. Neuroscience. 144, 165–190 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith CM et al. , Distribution of relaxin-3 and RXFP3 within arousal, stress, affective, and cognitive circuits of mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol 518, 4016–4045 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka M et al. , Neurons expressing relaxin 3/INSL 7 in the nucleus incertus respond to stress. Eur. J. Neurosci 21, 1659–1670 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nuñez A, Cervera-Ferri A, Olucha-Bordonau F, Ruiz-Torner A, Teruel V, Nucleus incertus contribution to hippocampal theta rhythm generation. Eur. J. Neurosci 23, 2731–2738 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teruel-Martí V et al. , Anatomical evidence for a ponto-septal pathway via the nucleus incertus in the rat. Brain Res. 1218, 87–96 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma S, Blasiak A, Olucha-Bordonau FE, Verberne AJM, Gundlach AL, Heterogeneous responses of nucleus incertus neurons to corticotrophin-releasing factor and coherent activity with hippocampal theta rhythm in the rat. J. Physiol 591, 3981–4001 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma S et al. , Nucleus incertus promotes cortical desynchronization and behavioral arousal. Brain Struct. Funct 222, 515–537 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-Díaz C et al. , Nucleus incertus ablation disrupted conspecific recognition and modified immediate early gene expression patterns in ‘social brain’ circuits of rats. Behav. Brain Res 356, 332–347 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freund TF, Buzsáki G, Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 6, 347–470 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanovsky Y, Sergeeva OA, Freund TF, Haas HL, Activation of interneurons at the stratum oriens/alveus border suppresses excitatory transmission to apical dendrites in the CA1 area of the mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience. 77, 87–96 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferraguti F et al. , Immunolocalization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α (mGluR1α) in distinct classes of interneuron in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. Hippocampus. 14, 193–215 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gulyás AI, Hájos N, Katona I, Freund TF, Interneurons are the local targets of hippocampal inhibitory cells which project to the medial septum. Eur. J. Neurosci 17, 1861–1872 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jinno S et al. , Neuronal diversity in GABAergic long-range projections from the hippocampus. J. Neurosci 27, 8790–804 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haidar M et al. , Relaxin-3 inputs target hippocampal interneurons and deletion of hilar relaxin-3 receptors in floxed-RXFP3 mice impairs spatial memory. Hippocampus. 27, 529–546 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jinno S, Kosaka T, Cellular architecture of the mouse hippocampus: A quantitative aspect of chemically defined GABAergic neurons with stereology. Neurosci. Res (2006), doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaifosh P, Lovett-Barron M, Turi GF, Reardon TR, Losonczy A, Septo-hippocampal GABAergic signaling across multiple modalities in awake mice. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1182–4 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]