Abstract

Microorganisms employ quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms to communicate with each other within microbial ecosystems. Emerging evidence suggests that intraspecies and interspecies QS plays an important role in antimicrobial resistance in microbial communities. However, the relationship between interkingdom QS and antimicrobial resistance is largely unknown. Here, we demonstrate that interkingdom QS interactions between a bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and a yeast, Candida albicans, induce the resistance of the latter to a widely used antifungal fluconazole. Phenotypic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses reveal that P. aeruginosa’s main QS molecule, N-(3-Oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone, induces candidal resistance to fluconazole by reversing the antifungal’s effect on the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. Accessory resistance mechanisms including upregulation of C. albicans drug-efflux, regulation of oxidative stress response, and maintenance of cell membrane integrity, further confirm this phenomenon. These findings demonstrate that P. aeruginosa QS molecules may confer protection to neighboring yeasts against azoles, in turn strengthening their co-existence in hostile polymicrobial infection sites.

Subject terms: Fungi, Microbiology, Antifungal agents, Antimicrobial resistance

Introduction

Microbial communities residing within the human body, either transiently or permanently, play a pivotal role in human health and disease1. In particular, interkingdom polymicrobial infections due to pathogenic fungi and bacteria are relatively common and are seen in the oral cavity, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal system, skin, and urinary tract1,2. For instance, the focal fungal pathogen of our study, Candida albicans, contributes to >50% of the total microbial burden in mixed fungal-bacterial chronic wound infections, and has been frequently co-isolated with bacterial pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus3–5. C. albicans is considered an independent risk factor for ventilator associated pneumonia and co-exists with P. aeruginosa in 26% of these infections6. When superinfected with Candida, the prognosis of P. aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis lungs are significantly poorer compared to the bacterial infection alone7,8. Alarmingly, 27–56% of nosocomial C. albicans blood stream infections are associated with Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. aureus and Enterococcus species9. Moreover, Candida spp. are co-isolated with vaginal streptococci in 20–34% of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, and with oral streptococci in 50–75% of denture stomatitis cases10–12. Candidal-bacterial polymicrobial infections are responsible for a high incidence of mortality and morbidity due to their increased dissemination, antimicrobial resistance, and the lack of sensitive diagnostics9,13. Hence, fungal-bacterial interkingdom infections represent an, as yet, understudied health issue warranting further investigation.

The severity and outcome of polymicrobial infections are dictated not only by the nature and the composition of the constituent microbiota, but also by the chemical communications between co-habitants. Quorum sensing (QS) is a universal chemical messenger system used by microorganisms to interact with each other. QS is defined as a cell-density dependent, coordinated gene expression in microbial communities in response to threshold concentrations of specific chemical signalling molecules (quorum sensing molecules; QSMs) leading to a synchronized population response14. QS is essential for microbes to optimize their survival in dynamic, constantly challenging niches, as the chemical messengers help correlate individual cellular functions to microbial community-based requirements14. These include regulation of biofilm development and maturation, motility and virulence, bacterial sporulation, formation of fungal fruiting bodies, conjugal plasmid transfer and antimicrobial resistance, and antibiotic synthesis15–17. QS interactions can occur among microbes from the same species (intraspecies QS), different species (interspecies QS) or even between members of different kingdoms (interkingdom QS)14. However, most studies have focused on intra- and interspecies QS, and our understanding of interkingdom QS is limited.

Candida QS interactions with the respiratory pathogen P. aeruginosa have been extensively studied due to their frequent co-isolation in cystic fibrosis lungs, wound infections, indwelling devices and nosocomial infections18–20. Farnesol, a major QSM secreted by C. albicans, is known to supress P. aeruginosa by inhibiting its homoserine lactone synthesis that leads to subsequent reduction in bacterial swarming, and pyocyanin and quinolone signaling (PQS, 2-alkyl-4-quinolones)15,20–22. Farnesol also acts on C. albicans itself by inhibiting hyphal development (filamentation) through repression of adenylyl cyclase (Cyr1p) in the Ras1–cyclic AMP–protein kinase A pathway, which positively regulates hyphal growth23. In addition, farnesol triggers cellular oxidative stress and apoptosis in C. albicans. Exposure to azole antifungal agents significantly increases farnesol synthesis in C. albicans24,25, and recent studies have shown that nonlethal concentrations of farnesol enhance the efficacy of azole antifungals by suppressing ABC multidrug efflux transporters and accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS)26,27. Interestingly, among the wide array of QSMs secreted by P. aeruginosa, N-(3-Oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (C16H27NO4, C12AHL) has a significant structural resemblance to farnesol28,29. Therefore, C12AHL also inhibits C. albicans hyphal development using the same mechanism as farnesol28,29. However, despite being structurally similar to farnesol, the effects of C12AHL on C. albicans’ cellular mechanisms upon exposure to antifungal agents, including multidrug efflux activity, cellular fitness, and ergosterol synthesis (the molecular target of azoles), are largely unknown.

We recently demonstrated that the co-delivery of C12AHL with fluconazole in a liposomal drug carrier increases the efficacy of the antifungal agent in elimination of C. albicans biofilms. However, free forms of drug + C12AHL failed to demonstrate similar antifungal efficacy30 suggesting the effects of C12AHL on C. albicans upon exposure to antifungal agents are drug and C12AHL formulation dependent. Owing to the recognized clinical importance of Pseudomonas-Candida interactions in various pathological states, lack of synergistic effects of free C12AHL + fluconazole on C. albicans biofilms observed in our recent study30, and the sparsity of data on the role of Pseudomonas QSMs on C. albicans antifungal sensitivity/resistance, we evaluated the cellular and molecular responses of C. albicans on in vitro exposure to a widely-used anti-fungal fluconazole in the presence of the QSM C12AHL. We assessed the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the active agents (Fluconazole, C12AHL, C12AHL + fluconazole) using broth dilution assay with a checkerboard approach. C. albicans’ multidrug efflux pump activity when exposed to the active agents was quantified by measuring the efflux of an indicator dye, rhodamine 6 g (Rhodamine 6 g Assay) and further verified based on the expression of genes coding for efflux pumps by qPCR. Changes in the C. albicans transcriptome in response to the active agents were assessed using next generation sequencing (RNA-Seq) and their effect on yeast protein synthesis was evaluated via two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. We demonstrate that P. aeruginosa C12AHL induces C. albicans’ fluconazole resistance through multiple mechanisms, predominantly by facilitating fungal ergosterol synthesis and restoring its cell wall integrity.

Results

C. albicans sensitivity to fluconazole decreases in the presence of C12AHL

We hypothesised that C12AHL would make C. albicans more sensitive to fluconazole due to its known inhibitory properties on the yeast, therefore the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC50 and MIC80) for fluconazole in the presence and absence of C12AHL was determined. Unexpectedly, the MIC50 of fluconazole exhibited a 16-fold increase in the presence of 100 µg mL−1 C12AHL (0.156 µg mL−1 vs 2.5 µg mL−1, Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S2) and 8-fold increase in the presence of 12.5–50 µg mL−1 C12AHL (0.156 µg mL−1 vs 1.25 µg mL−1, Supplementary Fig. S1). No MIC80 of fluconazole was observed when C. albicans was exposed to the antifungal agent alongside C12AHL within the concentration ranges assessed in this study. Therefore, MIC80 of fluconazole appears to increase more than 8-fold when treated with C12AHL with a concentration range of 12.5–100 µg mL−1 (1.25 vs >10 µg mL−1, Supplementary Fig S1 and Supplementary Table S2). C12AHL demonstrated a 20% maximum inhibition of C. albicans growth when treated with 100 µg mL−1.

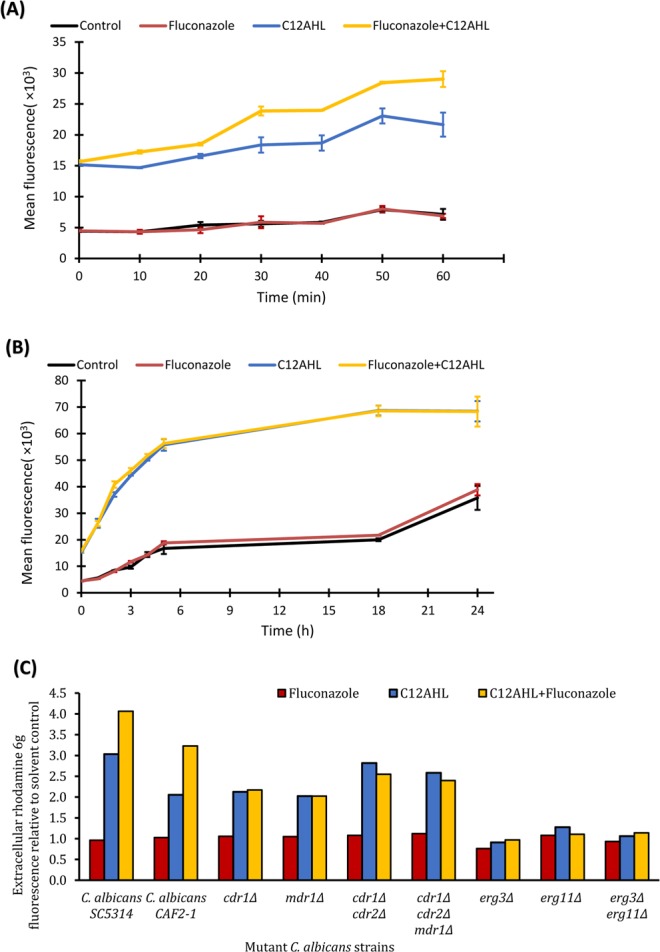

C12AHL stimulates the multidrug efflux activity of C. albicans

Efflux of antifungal drugs via transport proteins is one of the main mechanisms employed by C. albicans when developing antifungal resistance31. Therefore, the activity of transport proteins was assessed in the presence of various treatment groups. When exposed to C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole, C. albicans pumped out significantly higher quantities of the indicator dyeR6G compared to fluconazole treated or the solvent (DMSO) controls for up to an exposure period of 24 h (Fig. 1A,B, P < 0.05). C12AHL + fluconazole exposure showed significantly higher R6G efflux compared to C12AHL treated C. albicans in the early stages of the exposure (up to 1 h of observation, Fig. 1A, P < 0.05). However, the latter difference appeared to wane during prolonged exposure to the QSM ± antifungal (up to 24 h of exposure, Fig. 1B, P > 0.05). In contrast, C. albicans exposed to fluconazole alone did not show any notable changes of rhodamine efflux compared to the control (Fig. 1A,B, P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Mean drug efflux activity of C. albicans when exposed to C12AHL, fluconazole or their combination. (A) 1 h exposure, (B) 24 h exposure. Note the extracellular accumulation of significantly higher quantities of rhodamine 6 g when exposed to C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole compared to solvent control or fluconazole exposed samples. Standard deviations are presented as error bars (n = 18) (C) drug efflux activity of C. albicans mutants for a period of 1 h. There was a 2.0 to 2.8-fold increase in rhodamine 6 g efflux when CDR and MDR mutants were exposed to C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole for 1 h compared to solvent control, and insignificant changes in the ERG mutants (p-value < 0.05). C. albicans CAF2–1, the parental strain of the mutants tested, is included for comparison purposes.

Drug efflux pumps in C. albicans are mainly encoded by CDR1, CDR2 and MDR132, therefore, respective mutant strains were used to verify the efflux activity observed with the indicator dye. Efflux pump mutant strains of C. albicans, cdr1Δ (DSY448), mdr1Δ (DSY465), cdr1Δ/cdr2Δ (DSY653), and cdr1Δ/cdr2Δ/mdr1Δ (DSY1050) demonstrated a 2.0 to 2.8-fold increase in rhodamine 6 g efflux when exposed to C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole for 1 h compared to the solvent control (Fig. 1C, P < 0.05). Exposure to fluconazole alone failed to increase R6G efflux significantly (Fig. 1C P > 0.05). Functions of the efflux pumps are known to be affected by the composition of cell membrane sterols (ergosterol in particular)33,34. Therefore, the mutant strains of ERG11 and ERG3, the genes encoding rate limiting enzymes in ergosterol synthesis and sterol intermediates synthesis pathways31 were used to verify the role of sterols and the efflux activity observed with the indicator dye. Ergosterol mutant strains of C. albicans, erg3Δ (DSY1751), erg11Δ (DSY1769), erg3Δ erg11Δ (DSY1764) did not exhibit significant changes in efflux activity when exposed to any of the treatments for 1 h compared to the solvent control (Fig. 1C, P > 0.05).

C12AHL modulates the transcriptomic response of C. albicans when exposed to fluconazole

Transcriptomic sequencing was performed to determine which molecular mechanisms of C. albicans are modified in the presence of the QSM C12AHL, the antifungal fluconazole, or the combination of these molecules. First, an overall comparison of gene expression profiles was performed to assess whether there was an effect of the type of treatment. Then, differentially expressed genes were assessed for each treatment relative to the solvent control [(Fluconazole vs Control), (C12AHL vs Control), and (C12AHL + fluconazole vs Control)], as well as between treatments [(Fluconazole vs C12AHL), (Fluconazole vs C12AHL + fluconazole), and (C12AHL vs C12AHL + fluconazole)] to determine significant up- and/or downregulation of genes across the various treatments groups (adjusted p-value < 1e−5) (Supplementary Tables S3-S7).

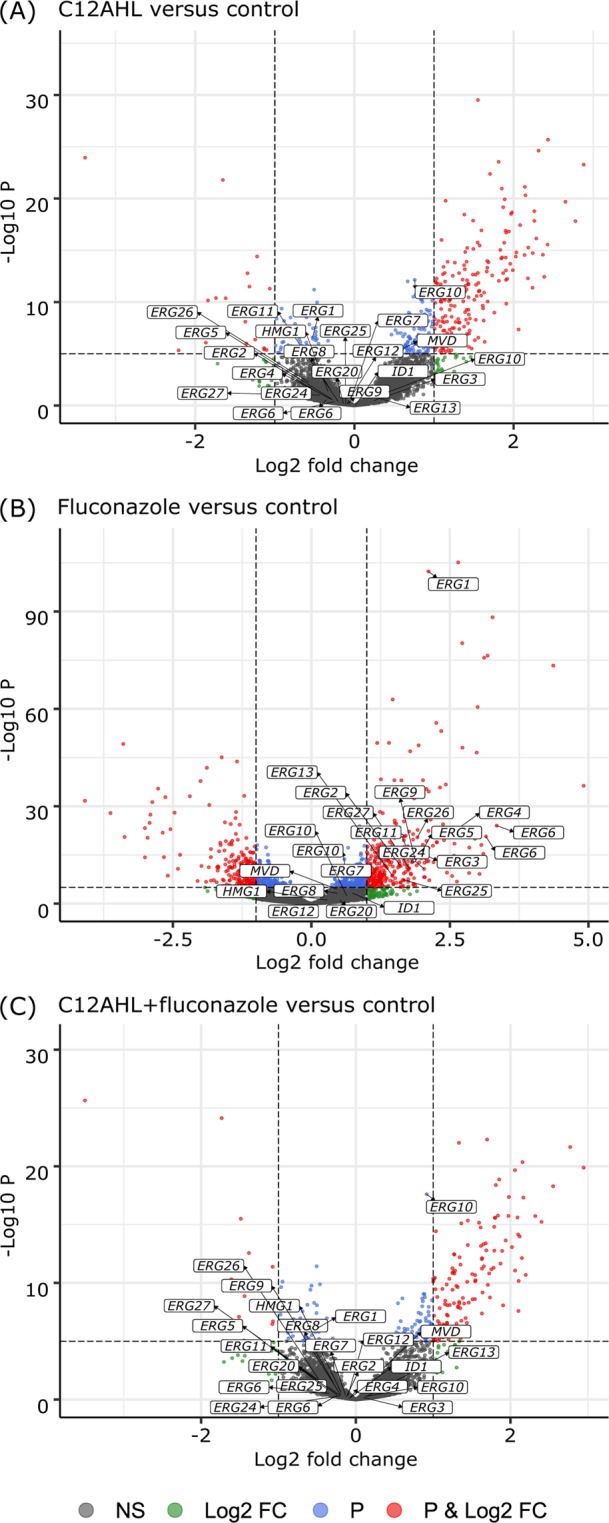

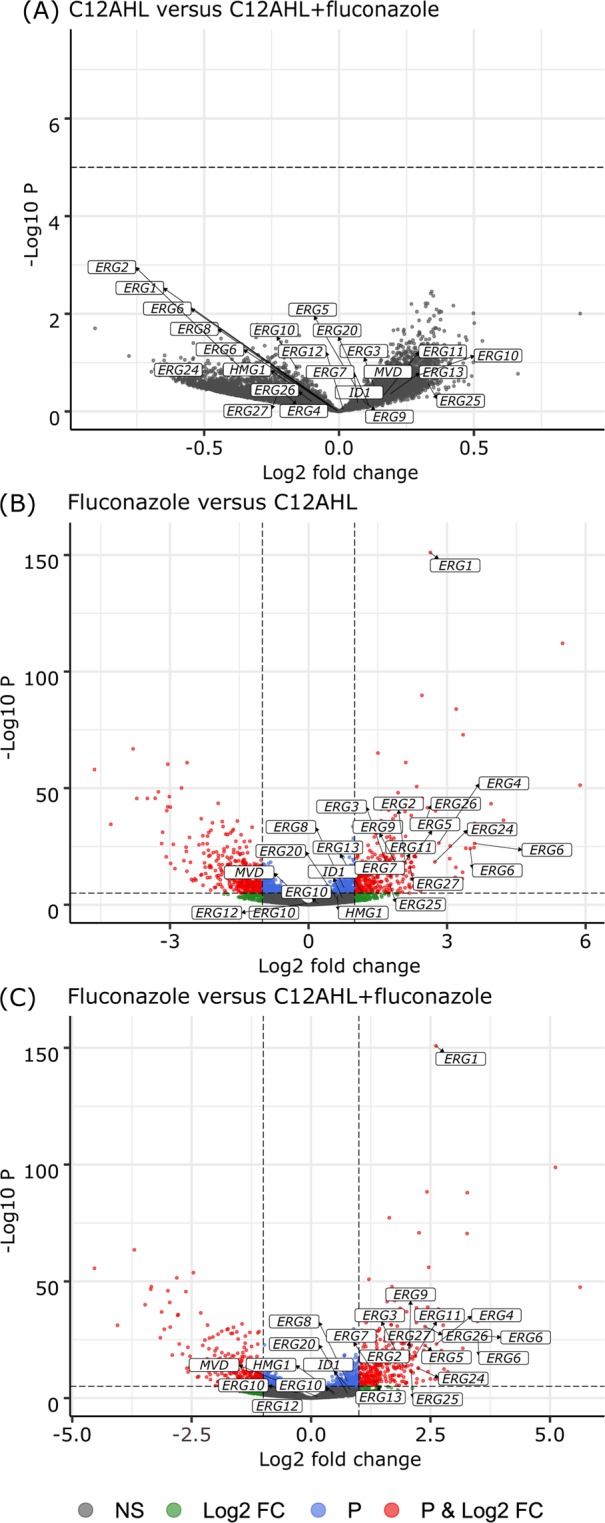

There was a significant influence of the type of treatment on the gene expression, with expression profiles for the fluconazole alone treated C. albicans being significantly different from the control, C12AHL and C12AHL + fluconazole samples (PERMANOVA, p-value < 0.05). This can also be observed graphically in a principle component analysis (Supplementary Fig. S8), where the fluconazole treated samples are statistically distinguishable from the control and other treatments in the second principle component (PC2), which accounts for almost a quarter of the total variation in the data. These results suggest that the effects of fluconazole were being ameliorated in the presence of C12AHL, and this is further confirmed when looking at the differentially expressed genes. Multiple genes were up- or downregulated in each treatment relative to the control samples, including the genes involved in ergosterol synthesis and antifungal resistance (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S9 and S10, Supplementary Tables S3-S7). Genes were also differentially expressed between treatments with the exception of C12AHL vs C12AHL + fluconazole (Tables 1–3, Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10). To determine the mechanisms of how C12AHL may be amending the effects of the antifungal molecule, we examined the differentially expressed pathways in more detail.

Table 2.

Gene expression data; The C. albicans genes that were significantly affected by both fluconazole only and C12AHL + fluconazole exposure compared to untreated controls [(Fluconazole vs Control) vs (C12AHL + fluconazole vs Control)]. Genes highlighted in blue are known to be associated with antifungal resistance/sensitivity. (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

| Gene Name | Annotation | C12AHL-Fluconazole treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value | Fluconazole treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3_03460C_A | Protein of unknown function | 3.45 | 3.54E-23 | 3.35 | 5.16E-23 |

| IFD6 | Aldo-keto reductase | 3.00 | 2.14E-21 | 1.75 | 6.62E-08 |

| ATX1 | Putative cytosolic copper metallochaperone | 2.74 | 3.92E-14 | −2.22 | 8.01E-10 |

| C1_01510W_A | Protein of unknown function | 2.41 | 1.41E-11 | 2.78 | 1.81E-16 |

| SRR1 | Two-component system response regulator | 2.15 | 1.81E-10 | 1.62 | 1.27E-06 |

| WOR4 | Predicted C2H2 zinc finger protein | 2.08 | 6.53E-11 | 2.09 | 7.17E-12 |

| RME1 | Zinc finger protein | 1.98 | 9E-07 | −1.95 | 4.98E-07 |

| NRG1 | Transcription factor/repressor | 1.95 | 9.01E-13 | 1.86 | 1.93E-12 |

| CSH1 | Aldo-keto reductase | 1.91 | 3.78E-07 | 3.36 | 5.11E-23 |

| CDR4 | Putative ABC transporter superfamily | 1.76 | 1.68E-11 | −1.43 | 2.18E-08 |

| LPG20 | Aldo-keto reductase family protein | 1.71 | 3.87E-06 | 2.44 | 4.3E-13 |

| C1_04010C_A | Protein with a NADP-dependent oxidoreductase domain | 1.57 | 1.54E-06 | 2.67 | 1.06E-19 |

| RGS2 | Protein of RGS superfamily | 1.17 | 7.97E-06 | 1.29 | 1.1E-07 |

| CR_10230W_A | Histone acetyltransferase activity | 1.07 | 8.15E-09 | 0.85 | 3.82E-06 |

| ENA21 | Predicted P-type ATPase sodium pump | −1.59 | 9.11E-06 | −2.00 | 1.19E-09 |

| PHHB | Putative 4a-hydroxytetrahydrobiopterin dehydratase | −1.78 | 1.04E-07 | −1.62 | 5.69E-07 |

| IFR2 | Zinc-binding dehydrogenase | −1.82 | 4.01E-08 | −1.79 | 2.02E-08 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of gene expression profiles between each treatment and the control. Volcano plots showing RNA-Seq data from each treatment [(A) C12AHL, (B) fluconazole and (C) C12AHL + fluconazole] relative to the control. The dashed lines represent the cut-off values for p-value (=10−6) and log2 fold change (=2) to identify significantly different gene expression. The plots are coloured so that non-significant differentially expressed genes are represented in grey, those with log2 fold change >2 are shown in green, genes with p-value < 10−6 are coloured in blue, and those with both log2 fold change >2 and p-value < 10−6 are shown in red. Genes that represent proteins involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway have been labelled in the plots.

Table 1.

Gene expression data; The C. albicans genes that were significantly affected by both fluconazole only and C12AHL only exposure compared to untreated controls [(Fluconazole vs Control) vs (C12AHL vs Control)]. Genes highlighted in blue are known to be associated with antifungal sensitivity/resistance. (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

| Gene Name | Annotation | Fluconazole treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value | C12AHL treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSH1 | Aldo-keto reductase | 3.36 | 5.11E-23 | 1.87 | 5.61E-07 |

| C3_03460C_A | Protein of unknown function | 3.35 | 5.16E-23 | 3.19 | 4.58E-20 |

| C1_01510W_A | Protein of unknown function | 2.78 | 1.81E-16 | 2.46 | 2.65E-12 |

| C1_04010C_A IFD1/IFD6 alias | Protein with a NADP-dependent oxidoreductase domain | 2.67 | 1.06E-19 | 1.68 | 1.47E-07 |

| LPG20 | Aldo-keto reductase family protein | 2.44 | 4.3E-13 | 1.65 | 8.38E-06 |

| CRH11 | GPI-anchored cell wall transglycosylase | 2.30 | 7.62E-08 | −2.36 | 1.36E-07 |

| WOR4 | Predicted C2H2 zinc finger protein | 2.09 | 7.17E-12 | 2.40 | 1.18E-14 |

| NRG1 | Transcription factor/repressor | 1.86 | 1.93E-12 | 2.18 | 4.02E-16 |

| IFD6 | Aldo-keto reductase | 1.75 | 6.62E-08 | 3.02 | 1.11E-21 |

| SRR1 | Two-component system response regulator | 1.62 | 1.27E-06 | 2.24 | 1.98E-11 |

| C2_01750C_A | Protein with a life-span regulatory factor domain | 1.33 | 8.99E-07 | 1.51 | 4.57E-08 |

| RGS2 | Protein of RGS superfamily | 1.29 | 1.1E-07 | 1.39 | 3.28E-08 |

| BCR1 | Transcription factor | 1.26 | 3.25E-07 | 1.21 | 3.28E-06 |

| CR_10230W_A | Histone acetyltransferase activity | 0.85 | 3.82E-06 | 1.36 | 2.94E-14 |

| CDR4 | Putative ABC transporter superfamily | −1.43 | 2.18E-08 | 1.70 | 6.09E-11 |

| PHHB | Putative 4a-hydroxytetrahydrobiopterin dehydratase | −1.62 | 5.69E-07 | −1.72 | 2.87E-07 |

| IFR2 | Zinc-binding dehydrogenase | −1.79 | 2.02E-08 | −1.78 | 8.07E-08 |

| RME1 | Zinc finger protein | −1.95 | 4.98E-07 | 2.17 | 3.28E-08 |

| ATX1 | Putative cytosolic copper metallochaperone | −2.22 | 8.01E-10 | 2.75 | 2.42E-14 |

Table 3.

Gene expression data; The C. albicans genes that were significantly affected by both C12AHL only and C12AHL + fluconazole exposure compared to untreated controls [(C12AHL vs Control) vs (C12AHL + fluconazole vs Control)]. Genes highlighted in blue are known to be associated with antifungal resistance/sensitivity. (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

| Gene Name | Annotation | C12AHL-Fluconazole treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value | C12AHL treated compared to control: log2FoldChange | Adjusted P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3_03460C_A | Protein of unknown function | 3.45 | 3.54E-23 | 3.19 | 4.58E-20 |

| IFD6 | Aldo-keto reductase | 3.00 | 2.14E-21 | 3.02 | 1.11E-21 |

| UGT51C1 | UDP-glucose:sterol glucosyltransferase | 2.20 | 1.95E-19 | 2.38 | 1.45E-22 |

| CRZ2 | C2H2 transcription factor | 2.30 | 2.41E-14 | 2.51 | 2.86E-17 |

| ATX1 | Putative cytosolic copper metallochaperone | 2.74 | 3.92E-14 | 2.75 | 2.42E-14 |

| ALK2 | N-Alkane inducible cytochrome P450 | 1.93 | 2.75E-13 | 1.63 | 1.09E-09 |

| NRG1 | Transcription factor/repressor | 1.95 | 9.01E-13 | 2.18 | 4.02E-16 |

| C1_01510W_A | Protein of unknown function | 2.41 | 1.41E-11 | 2.46 | 2.65E-12 |

| CDR4 | Putative ABC transporter superfamily | 1.76 | 1.68E-11 | 1.70 | 6.09E-11 |

| YOR1 | ABC-type plasma membrane transporter | 1.35 | 3.45E-11 | 1.41 | 2.33E-12 |

| WOR4 | Predicted C2H2 zinc finger protein | 2.08 | 6.53E-11 | 2.40 | 1.18E-14 |

| ADA2 | Zinc finger and homeodomain transcriptional coactivator | 1.51 | 8.98E-11 | 1.67 | 2.43E-13 |

| C6_02100W_A | Secreted protein | −3.73 | 1.15E-10 | −3.54 | 9.31E-10 |

| OPT3 | Oligopeptide transporter | 2.16 | 1.39E-10 | 2.15 | 1.60E-10 |

| SRR1 | Two-component system response regulator | 2.15 | 1.81E-10 | 2.24 | 1.98E-11 |

| C7_04090C_A | Predicted mitochondrial cardiolipin-specific phospholipase | 2.33 | 2.33E-10 | 2.35 | 1.59E-10 |

| C1_09210C_A | Putative transporter | 1.72 | 2.42E-10 | 1.47 | 8.96E-08 |

| C3_05450C_A | Protein of unknown function | 2.38 | 4.54E-10 | 2.53 | 2.17E-11 |

| ZCF1 | Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor | 1.43 | 6.29E-10 | 1.59 | 2.33E-12 |

| RFG1 | HMG domain transcriptional repressor | 1.81 | 7.32E-10 | 1.94 | 3.12E-11 |

| MOH1 | Ortholog of S. cerevisiae Moh1 | 1.61 | 2.14E-09 | 1.68 | 2.64E-10 |

| CR_09100C_A | Aldo-keto reductase | 2.30 | 4.70E-09 | 2.35 | 1.36E-09 |

| FBA1 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | −1.79 | 5.31E-09 | −1.64 | 8.92E-08 |

| EFG1 | bHLH transcription factor | 1.88 | 7.64E-09 | 1.97 | 9.31E-10 |

| CR_10230W_A | Ortholog(s) have histone acetyltransferase activity | 1.07 | 8.15E-09 | 1.36 | 2.94E-14 |

| HSP78 | Heat-shock protein | 2.23 | 1.33E-08 | 2.22 | 1.27E-08 |

| RPN4 | C2H2 transcription factor | 1.34 | 1.56E-08 | 1.40 | 3.13E-09 |

| SNQ2 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Snq2p transporter | 1.74 | 1.56E-08 | 1.55 | 6.73E-07 |

| CR_06140W_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.96 | 1.56E-08 | 1.98 | 1.08E-08 |

| C7_00770W_A | Protein of unknown function | 2.19 | 1.73E-08 | 1.81 | 6.81E-06 |

| HSP104 | Heat-shock protein | 2.54 | 1.83E-08 | 2.47 | 3.99E-08 |

| GOR1 | Ortholog(s) have glyoxylate reductase activity | 2.16 | 1.86E-08 | 2.00 | 2.37E-07 |

| IFR2 | Zinc-binding dehydrogenase | −1.82 | 4.01E-08 | −1.78 | 8.07E-08 |

| AAF1 | Possible regulatory protein | 2.13 | 5.63E-08 | 2.18 | 2.21E-08 |

| YIM1 | Protein similar to protease of mitochondrial inner membrane | 1.95 | 6.00E-08 | 2.00 | 2.04E-08 |

| PHHB | Putative 4a-hydroxytetrahydrobiopterin dehydratase | −1.78 | 1.04E-07 | −1.72 | 2.87E-07 |

| ERO1 | Ortholog of S. cerevisiae Ero1 | 1.91 | 1.20E-07 | 2.00 | 1.82E-08 |

| MNN42 | Protein of unknown function | 1.25 | 1.48E-07 | 1.43 | 6.88E-10 |

| HAL9 | Putative Zn(II)2Cys6 transcription factor | 1.35 | 2.48E-07 | 1.40 | 5.22E-08 |

| ADH3 | Putative NAD-dependent (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase | 3.05 | 2.81E-07 | 3.25 | 2.36E-08 |

| INO2 | Transcriptional activator | 1.76 | 3.13E-07 | 1.92 | 1.24E-08 |

| CSH1 | Aldo-keto reductase | 1.91 | 3.78E-07 | 1.87 | 5.61E-07 |

| C6_00290W_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.54 | 4.63E-07 | 1.67 | 2.04E-08 |

| GRP2 | Methylglyoxal reductase | 2.50 | 4.86E-07 | 2.62 | 8.07E-08 |

| ISA1 | Putative mitochondrial iron-sulfur protein | 1.39 | 7.93E-07 | 1.55 | 1.62E-08 |

| RME1 | Zinc finger protein | 1.98 | 9.00E-07 | 2.17 | 3.28E-08 |

| C1_04010C_A | Protein with a NADP-dependent oxidoreductase domain | 1.57 | 1.54E-06 | 1.68 | 1.47E-07 |

| GAL102 | UDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | 1.85 | 1.54E-06 | 2.05 | 3.84E-08 |

| C5_04030W_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.85 | 2.15E-06 | 2.08 | 3.99E-08 |

| C4_03020W_A | Putative mitochondrial GTPase | 0.98 | 2.64E-06 | 1.18 | 4.87E-09 |

| ALS7 | ALS family protein | 0.95 | 2.83E-06 | 1.12 | 1.07E-08 |

| MNN12 | Predicted alpha-1,3-mannosyltransferase | −1.90 | 2.89E-06 | −1.93 | 1.55E-06 |

| C3_02630C_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.20 | 3.87E-06 | 1.42 | 1.29E-08 |

| SIS1 | Putative Type II HSP40 co-chaperone | 1.98 | 3.87E-06 | 1.94 | 5.25E-06 |

| LPG20 | Aldo-keto reductase family protein | 1.71 | 3.87E-06 | 1.65 | 8.38E-06 |

| HSP90 | Essential chaperone | 1.71 | 3.87E-06 | 1.85 | 2.86E-07 |

| MHP1 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Mhp1p | 1.10 | 3.93E-06 | 1.09 | 4.69E-06 |

| C3_00360W_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.43 | 4.78E-06 | 1.88 | 2.21E-10 |

| C1_03990W_A | Ortholog(s) have proteasome binding activity | 1.64 | 6.48E-06 | 1.95 | 2.07E-08 |

| CR_06960W_A | Ortholog(s) have ATP binding, DNA replication origin binding activity | 1.29 | 6.48E-06 | 1.35 | 1.73E-06 |

| C1_01130W_A | Putative ubiquitin ligase complex component | 1.06 | 7.23E-06 | 1.09 | 2.80E-06 |

| RGS2 | Protein of RGS superfamily | 1.17 | 7.97E-06 | 1.39 | 3.28E-08 |

| CR_07480W_A | Predicted auxin family transmembrane transporter | 1.02 | 9.33E-06 | 1.22 | 2.41E-08 |

| C4_02740W_A | Protein of unknown function | 1.48 | 9.33E-06 | 1.54 | 2.80E-06 |

Figure 3.

Comparison of gene expression profiles between the different treatments. Volcano plots showing the comparison of RNA-Seq data between the different treatments [(A) C12AHL vs C12AHL + fluconazole, (B) fluconazole vs C12AHL, and (C) fluconazole vs C12AHL + fluconazole]. The dashed lines represent the cut-off values for p-value (=10−6) and log2 fold change (=2) to identify significantly different gene expression. The plots are coloured so that non-significant differentially expressed genes are represented in grey, those with log2 fold change >2 are shown in green, genes with p-value < 10−6 are coloured in blue, and those with both log2 fold change >2 and p-value < 10−6 are shown in red. Genes that represent proteins involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway have been labelled in the plots.

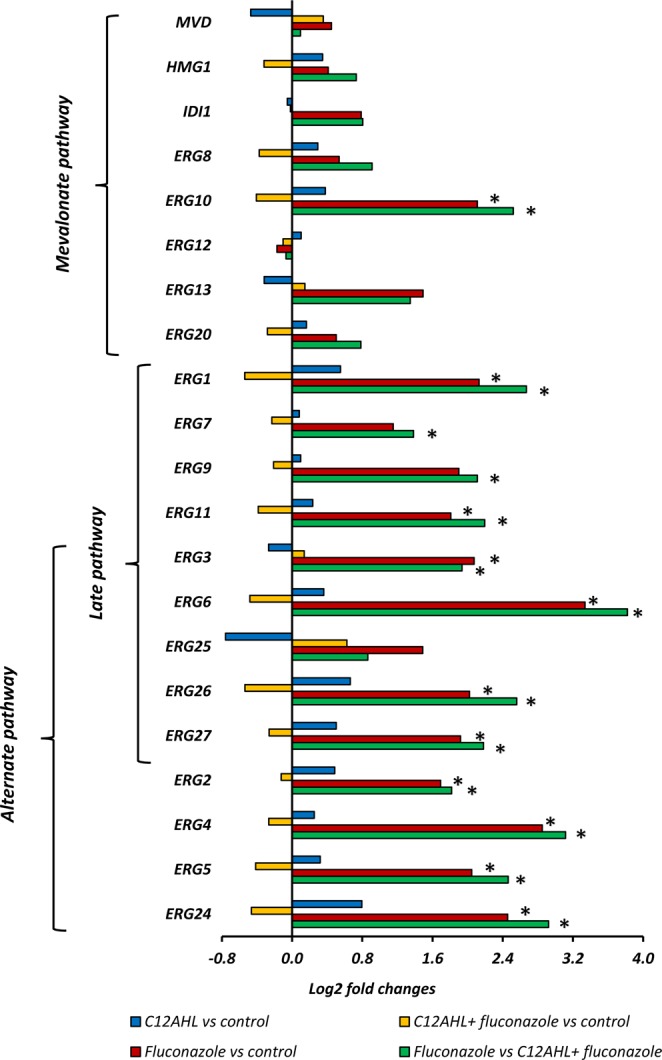

C12AHL modulates gene expression in the C. albicans ergosterol synthesis pathway upon exposure to fluconazole

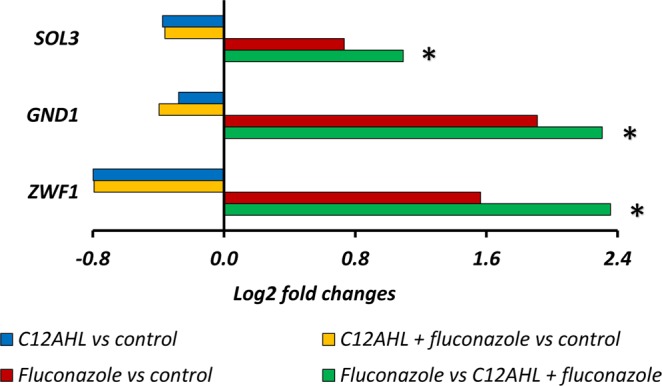

The C. albicans genes were collated into 156 different molecular pathways using published data from the Candida Genome Database. Once grouped, two molecular pathways in particular showed significant differences when comparing treatments, i.e. the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway and the pentose phosphate pathway. Comparison of genes involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (as shown in Fig. 4) revealed significant upregulation of ERG1, ERG2, ERG4, ERG5, ERG6, ERG10, ERG11, ERG24, ERG26, and ERG27 in fluconazole treated samples compared to solvent controls, C12AHL treated, and C12AHL + fluconazole treated C. albicans. ERG3 was upregulated in fluconazole treated C. albicans compared to solvent controls, while ERG7 and ERG9 were upregulated in fluconazole treated C. albicans compared to C12AHL + fluconazole treated samples (Fig. 4). Genes involved in the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway (SOL3, GND1, ZWF1), were significantly upregulated in fluconazole treated C. albicans compared to C12AHL treated and C12AHL + fluconazole treated C. albicans (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

C. albicans molecular pathways analyses; The genes in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway that are affected by fluconazole, C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole exposure. Comparisons denoted with * are significant (adjusted p-value < 1e−5). ERG1: Squalene epoxidase, ERG2: C-8 sterol isomerase, ERG3: C-5 sterol desaturase, ERG4: sterol C-24 reductase, ERG5: C-22 sterol desaturase, ERG6: Delta (24)-sterol C-methyltransferase, ERG7: 2,3-epoxysqualene-lanosterol cyclase (lanosterol synthase), ERG8: phosphomevalonate kinase, ERG9: farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyl transferase (squalene synthase), ERG10: Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, ERG11: Lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase, ERG12: mevalonate kinase, ERG13: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase, ERG20: farnesyl pyrophosphate synthetase, ERG24: C-14 sterol reductase, ERG25: C-4 methyl sterol oxidase, ERG26: C-3 sterol dehydrogenase, ERG27: 3-Keto sterol reductase, HMG1: HMG-CoA reductase, IDI1: isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase, and MVD: Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase.

Figure 5.

C. albicans molecular pathways analyses; Genes in the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway that are affected by fluconazole, C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole exposure. Comparisons denoted with * are significant (adjusted p-value < 1e−5). ZWF1: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, GND1: 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and SOL3: 6-phosphogluconolactonase.

C12AHL alters protein expression in C. albicans exposed to fluconazole

In order to further assess the findings of the transcriptomic analyses, protein expression of C. albicans exposed to fluconazole with/without C12AHL was investigated. According to 2-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometric data, addition of C12AHL led to differential expression of a variety of C. albicans proteins in the presence of fluconazole. A total of 17 under-expressed (Supplementary Table S11) and seven over-expressed (Supplementary Table S12) proteins were identified in the C12AHL + fluconazole treated C. albicans compared to the fluconazole only control (p-value < 0.05).

Several proteins that are known to be induced by fluconazole and/or other antifungals exposure (Gcy1p, Lsc1p, Pda1p, Atp1p, Mxr1p and Ach1p) were identified in fluconazole only treated C. albicans whereas they were absent in C12AHL + fluconazole treated samples (Supplementary Tables S11 and S12).

C12AHL upregulates multidrug efflux pumps-coding genes in C. albicans exposed to fluconazole

Surprisingly, there was no indication of significantly increased expression of multidrug efflux pump genes at either the RNA or protein level after 24 h exposure to fluconazole in the presence of C12AHL. This is despite the observed increase in indicator dye efflux activity of the C. albicans strain in the presence of C12AHL + fluconazole. To understand whether there was any involvement of multidrug efflux pump genes on indicator dye efflux activity at the early stages of C12AHL + fluconazole exposure (1 h), the expression of these genes was assessed using qPCR32. Exposure to C12AHL + fluconazole for 1 h significantly upregulated C. albicans CDR1 (2.4-fold) and CDR2 (5-fold) genes compared to solvent controls (Supplementary Fig. S13, P < 0.05). C12AHL treated C. albicans also showed upregulation of CDR2 (1.9-fold), however, CDR1 and MDR1 were downregulated compared to solvent controls. In contrast, both CDR genes were downregulated when exposed to fluconazole alone (CDR1:2.5 fold and CDR2:1.4-fold). MDR1 expression was not affected by C12AHL + fluconazole treatment.

Discussion

In host-associated environments, fungi and bacteria interact physically (e.g. co-aggregation) and chemically (e.g. quorum sensing), thereby impacting their immediate surroundings as well as the host immune response35. Such mutualistic/synergistic interactions have evolved to facilitate epithelial cohabitation and efficient use of metabolic by-products, while competitive antagonistic approaches have also developed during co-colonization36. Although the fundamental role of QS in optimizing microbial survival in polymicrobial environments has been well-studied, very little is known of the interactions and effects of interkingdom QS systems during antimicrobial therapy. Here we studied the effect of the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing molecule, C12AHL, on the cellular and molecular responses of C. albicans when exposed to the anti-fungal molecule fluconazole.

The role of C12AHL in interactions between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa has been increasingly studied in recent years. For example, it is known that P. aeruginosa cells preferentially adhere to C. albicans hyphae using their surface adherence proteins37,38. Using C12AHL defective mutants, Ovchinnikova et al. (2012) demonstrated that C12AHL is essential for the expression of P. aeruginosa adhesion proteins, and therefore is critical for adherence to C. albicans hyphae in a mixed fungal-bacterial environment37. Previous studies based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometric analyses, have reported that P. aeruginosa biofilms may contain over 600 µM (~178.5 µg mL−1) of peak C12AHL28,39. It is also noteworthy that QSM concentrations within the microbial populations vary depending on the different stages of biofilm growth, with lower concentrations during early stages of biofilm formation and biofilm dispersal, and higher concentrations during maturation. Subsequent studies have further suggested that >200 μM of C12AHL (59.5 µg mL−1) suppresses C. albicans hyphal growth whilst >500 μM (148.5 µg mL−1) of C12AHL inhibits fungal growth completely28. Hence, from the range of concentrations tested, we used sub-growth and sub-hyphal inhibitory concentration (50 µg mL−1, 168 µM) of C12AHL throughout our study. The inability to form hyphae with concentrations of C12AHL used (12.5–100 µg mL−1) was confirmed via a germ tube assay (Data not shown).

The 16-fold measured increase in the MIC of fluconazole indicates that C. albicans sensitivity to fluconazole decreases when it is simultaneously exposed to the antifungal and C12AHL (100 µg mL−1). Indeed, even at lower concentrations (12.5–50 µg mL−1) C12AHL induced fluconazole resistance in C. albicans compared to fluconazole-treated controls (Fig. 1A, p-value < 0.05). In our latest published work, we witnessed this lack of inhibitory properties of C12AHL and fluconazole when delivered to C. albicans biofilms as free forms without encapsulating into a drug carrier molecule (i.e. liposomes)30. Although the exact mechanism is yet to decipher, the synergy we observed with fluconazole and C12AHL in the form of liposomes is likely to be attributed to the characteristics of the liposomal formulation (i.e. enhanced penetration), slow and sustained drug release, the encapsulated dosage of the active agents and the intrinsic properties of Candida biofilm phenotype. This evidence further supported aforementioned hypothesis of fluconazole and C12AHL antagonism. In line with this finding, recent studies have also shown an increase in C. albicans’ antifungal resistance in C. albicans-P. aeruginosa mixed species biofilms via upregulated C. albicans proteins associated with drug resistance and virulence40. However, it is known that C. albicans exhibits distinctive responses to antifungal agents and the environmental stresses (such as to bacterial QSMs) based on its physiological forms (i.e. biofilm vs planktonic phases). Therefore, in part, the lack of C. albicans inhibition observed with C12AHL ± fluconazole in our study compared to the existing Candida biofilm literature is likely to be associated the variations in the experimental design as this study focuses on planktonic phenotype, the usage of sub-growth and sub-hyphal inhibitory concentrations of C12AHL and other unknown fungal mechanisms. Accordingly, cautions must be taken when generalised inferences are made.

Intracellular R6G indicator dye accumulation is commonly used to identify azole-resistant C. albicans strains as it has been shown that the retention of R6G within fungal cells is inversely correlated with the expression of the drug efflux pump protein, Cdr1p, in C. albicans41,42. Our R6G assay reveals for the first time that exposure to the QSM C12AHL can upregulate the efflux activity of C. albicans. The presence of fluconazole in combination with C12AHL further enhances this increased efflux activity, indicating a potential mechanism of C12AHL-mediated fluconazole resistance in the yeast. Unlike C12AHL, its structural analogue farnesol produced by C. albicans is known to inhibit C. albicans drug efflux during fluconazole exposure, thereby potentiating the activity of the antifungal drug26,27. This result demonstrates the functional diversity of C12AHL and farnesol, despite their structural resemblance43.

C. albicans possesses three major plasma membrane drug efflux pump proteins: Cdr1p, Cdr2p [ATP-binding cassette (ABC) pumps] and Mdr1p [the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters] that are known to regulate azole efflux32. Using a set of isogenic C. albicans strains lacking the genes for one or more of these drug efflux pumps (CDR1, CDR2 and MDR1), Mukherjee et al. concluded that drug efflux pumps play a significant role in candidal resistance to fluconazole in early planktonic and biofilm phases (0–6 h)44. Our qPCR data indicated that short-term exposure (1 h) of C. albicans (azole-sensitive strain) to fluconazole in the presence of C12AHL upregulates the expression of CDR1 and CDR2. This observation supports a previous study that showed upregulation of CDR1 in C. albicans biofilms when exposed to P. aeruginosa secretory factors45. Taken together, these findings suggest that C12AHL ± fluconazole triggers phenotypic and transcriptional changes in multidrug efflux mechanisms in C. albicans within a short period of exposure (~1 h), suggesting a potential mechanism of early azole resistance. Further mechanistic investigations on C. albicans early antifungal resistance are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

In contrast to previous reports on the temporal nature of the efflux activity and the absence of significant expression of CDR1 and CDR2 in the latter stages of planktonic/biofilm phases (e.g. 24 h), we noted that the efflux activity in C. albicans remained significantly higher for 24 h upon exposure to C12AHL ± fluconazole. Interestingly, transcriptomic data did not show significant changes in CDR1, CDR2, MDR1, FLU1 or TAC1 gene expression after 24 h treatment. In addition, we also noted that C. albicans cdr1Δ, mdr1Δ, cdr1Δ/cdr2Δ, and cdr1Δ/cdr2Δ/mdr1Δ strains continued to transport R6G outside of the cell, albeit to a lesser degree compared to the wild type, despite the respective mutations. Hence, the persistent efflux activity observed here is likely regulated via another mechanism(s).

Fungal ABC superfamily efflux pump proteins (Cdr1p in particular) are sensitive to imbalanced lipid composition in the yeast plasma membrane, and their mutual interactions with membrane sterols (mainly ergosterol) are critical for the sorting and functioning of efflux pump proteins in C. albicans33,34. Therefore, we hypothesized that increased efflux pump activity of C. albicans when exposed to C12AHL ± fluconazole is likely to be associated with changes in ergosterol biosynthesis. In order to test this, we assessed the R6G efflux activity of two mutant C. albicans strains with knockout of key genes involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (ERG11 and ERG3). Interestingly, we noted that erg11Δ, erg3Δ and erg3Δ/erg11Δ strains were incapable of altering their efflux activity in response to 1 h exposure to C12AHL ± fluconazole, in contrast to the wild type. This suggests that the effect of C12AHL ± fluconazole on efflux pump activity may be associated with changes in the ergosterol synthesis pathway.

Azoles and many other antifungal drugs primarily target ergosterol biosynthesis in C. albicans. The sterol biosynthesis pathway possesses three distinct sub-pathways; mevalonate, late and alternate pathways (Supplementary Fig. S14). The mevalonate pathway, the first step in the sterol synthesis process, entails the production of farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) from acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA)46. The resulting FPP is fed into many different cellular pathways as it is an essential intermediate in the biosynthesis of sterols (i.e. ergosterol), heme, ubiquinone, dolichol, and prenylated proteins46,47. The pathway responsible for the catalysation of FPP to synthesise ergosterol is identified as the late pathway. When antifungal agents such as azoles interfere with the late pathway, it branches out to the alternate pathway that produces sterol intermediates instead of ergosterol. Some of these sterol intermediates are known to be toxic and their intracellular accumulation arrests cell growth48,49.

Fluconazole suppresses C14α-demythylase encoded by ERG11 in the late pathway, which normally catalyzes lanosterol to C14-demethyl-lanosterol and would ultimately lead to the synthesis of ergosterol. Suppression of ERG11 reroutes the late pathway to the alternate pathway by expressing C24 methyl transferase (ERG6) with the synthesis of various sterol intermediates as a result. One particular intermediate is the toxic compound 14α-methyl-3,6-diol, which is catalysed by C5 desaturase (ERG3) in the final step and ultimately arrests fungal growth46. Ergosterol is a major sterol component of the yeast cell wall and mitochondrial membrane, and is vital in maintaining membrane fluidity and permeability, enzyme activity, cell cycle progression and cell morphology50. In addition, sterols and sphingolipids together form lipid rafts, i.e. a type of microdomain located in the fungal cell membrane, that is enriched with numerous molecules such as efflux pumps, sodium and potassium pumps, receptors, and nutrient transporters51,52.

In this study, gene and protein expression data provided strong evidence to suggest that C12AHL mediated induction of fluconazole resistance in C. albicans is associated with ergosterol biosynthesis. Previous studies have established that prolonged exposure to azoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, clotrimazole, and miconazole) can trigger over expression of ERG11 and other genes associated with the alternate pathway of sterol synthesis (ERG9, ERG1, ERG7, ERG3), particularly during the logarithmic growth phase of the yeast50,53,54. Our gene expression data also demonstrated similar findings, for example, all genes of both the late and alternate pathways (except ERG25) of sterol biosynthesis were significantly upregulated when C. albicans was exposed to fluconazole but remained unaffected with either C12AHL + fluconazole or C12AHL exposure. Therefore, these results suggest that the effect of fluconazole on C. albicans’ late and alternate pathways of sterol synthesis is suppressed in the presence of C12AHL. Functional investigations using relevant key mutant strains of the ergosterol synthesis pathway could provide valuable mechanistic insights to further support the observed changes in gene expression.

The enzymes that catalyse the sterol biosynthesis pathway are regulated in part by the zinc-cysteine finger transcription factor paralogs Upc2p in C. albicans55,56. Upc2p senses sterol levels within the yeast and when these levels are reduced, for example due to fluconazole interference, it activates genes for sterol biosynthesis and uptake55,56. Our gene expression data confirmed significant upregulation of UPC2 (codes for Upc2p) in fluconazole treated C. albicans as a result of fluconazole-mediated inhibition of ergosterol synthesis. This finding explains why not only genes in the alternate pathway were upregulated in the fluconazole treated samples, but there was also indirect upregulation of the genes in the late pathway. Experiments using UPC2 mutant C. albicans could be performed to further confirm this observation.

Notably, neither C12AHL nor C12AHL + fluconazole treated samples elicited the changes observed in the presence of fluconazole alone, indicating that the regulation of sterol biosynthesis/uptake in the yeast in the presence of the QSM was unaffected. This is further evidenced by no significant change in the expression of ECM33 relative to the control, which codes for protein molecules within lipid rafts that are sensitive to changes in the cell membrane composition. The maintenance of lipid rafts is critically important for proper functioning of a variety of cellular processes, cell signalling, protein sorting, virulence, stress responses, and environmental adaptations33,34,51,57. ECM33 is known to be significantly upregulated during exposure to fluconazole as observed in our data58. We also noted an upregulation of UGT51C1 in C12AHL + fluconazole treated but not in fluconazole treated C. albicans. UGT51C1 codes for UDP-glucose:sterol glucosyltransferase that catalyses the biosynthesis of sterol glycosides from ergosterol59. Upregulation of this gene indicates that there is likely to be a continual supply of ergosterol as substrate to the enzyme, thus further supporting the hypothesis of unaffected ergosterol synthesis in C. albicans by fluconazole when C12AHL is present.

C. albicans can use three antioxidant systems (i.e. catalase, thioredoxin and glutathione) and two major oxidative stress signalling pathways (i.e. Cap1 and Hog 1) to respond to oxidative stress induced by antifungals. Oxidative stress induced by antifungals stimulates NADPH production in C. albicans via the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)60–62. NADPH is an essential cofactor for glutathione- and thioredoxin-dependent enzymes in antioxidant systems (thioredoxin and glutathione, respectively) that neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS)63–65. Therefore, the oxidative branch of the PPP is critical for fungal survival against oxidative stress66,67. Glucose-6-phosphate-1-dehydrogenase coded by ZWF1 regulates the rate limiting first step of the oxidative branch of PPP68 and the gene expression profiles from this experiment showed significant upregulation of genes in the oxidative arm of the PPP, in particular ZWF1, in the fluconazole treated samples. This effect was however not observed when C12AHL was present. In addition, as observed in the protein expression data, several key proteins that play a role in protecting the fungus from oxidative stress, Sod1p (superoxide dismutase69), Pst1p (Flavodoxin-like protein70), Mxr1p (methionine sulfoxide reductase62, Adh4p (alcohol dehydrogenase71), and Cyp5p (Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase72), were downregulated in C. albicans treated with C12AHL + fluconazole compared to fluconazole alone treated samples. These results suggest that the presence of C12AHL prevents the oxidative stress otherwise imposed by fluconazole on the yeast cells.

Another interesting finding was that the presence of C12AHL appears to increase the overall fitness of C. albicans when challenged with fluconazole. For instance, we observed significant upregulation of genes GAL102, C2_00770W_A, and DAG7 that lower the sensitivity of the yeast to toxic sterol analogues accumulated via the alternate pathway73,74. Similarly, GAL102 plays an important role in yeast cell wall synthesis and resistance to antifungal drugs by stabilizing the cell wall73. Upregulation of GAL102 together with other genes that are known to regulate yeast cell wall synthesis and repair (i.e. INO2, ADA2, PHR1 and MNN12) may further indicate that the presence of C12AHL prevents the impact of fluconazole on yeast cell wall integrity and improves the overall cellular fitness75,76.

In summary, our data suggest that the presence of C12AHL favorably affects C. albicans challenged with fluconazole by preventing changes in sterol biosynthesis, increasing drug efflux pump activity, reducing the oxidative stress response, and maintaining yeast cell membrane integrity. These conclusions are largely based on our transcriptomic data; therefore, appropriate functional assessments as indicated are necessary to verify these claims. Further investigations on sterol analyses (including total cellular sterol and sterol intermediates) as well as changes in plasma membrane composition of the yeast are necessary to confirm this hypothesis. In addition, recent studies have highlighted some of the complex interactions between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa in polymicrobial infections. For example, certain compounds produced by C. albicans, that remain to be characterized, have been shown to stimulate the synthesis of virulence factors (e.g. phenazine production) by Pseudomonas spp., as well as to reduce swarming motility which leads to enhanced biofilm development20,77. Therefore, further investigations on C. albicans and P. aeruginosa cocultured in a polymicrobial biofilm environment would be beneficial to understand the specific interactions between these two microorganisms when exposed to fluconazole. Selective physical interactions between P. aeruginosa and C. albicans filaments, together with mutual inhibitory and beneficial effects of the QSMs C12AHL and farnesol, speak to the importance of co-existence and the interdependence of P. aeruginosa and C. albicans for their survival in mixed microbial communities. Hence, the core finding of our study, that C12AHL induces antifungal resistance in C. albicans, thereby protecting the fungal population, is likely to be another control mechanism employed by P. aeruginosa in optimizing its survival in challenging polymicrobial environments.

Material and methods

Microorganisms and quorum sensing molecules

C. albicans SC5314 (a fluconazole sensitive strain) was used throughout this study. Microbial identity was reconfirmed with commercially available API 32 C for Candida strains (Biomérieux, Mercy I’Etoile, France). Mutant C. albicans strains DSY448, DSY465, DSY654, DSY1050, DSY1751, DSY1764, DSY1769 and parental strain C. albicans CAF2–1 (Supplementary Table S15) were kindly gifted by Associate Professor Dominique Sanglard from the Institute of Microbiology, University Hospital Lausanne, Switzerland. All isolates were stored in multiple aliquots at –70 °C, after confirming their purity.

C12AHL from P. aeruginosa (Catalogue No. O9139) and fluconazole (Catalogue No. F8929) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20 °C until further use.

Growth media

Sabouraud dextrose agar and yeast nitrogen base with amino acids (YNB; Catalogue No. Y1250; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) solution supplemented with 100 mm glucose were used for culturing C. albicans. RPMI 1640 media supplemented with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) was used for broth microdilution assays.

Yeast inocula

Before each experiment, both C. albicans wild type and mutant strains were subcultured on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar for 18 h at 37 °C. A single colony from overnight C. albicans growth was inoculated into YNB medium and incubated for 18 h in an orbital shaker (150 rpm) at 37 °C. The resultant culture was harvested, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) and resuspended in YNB. Cell suspensions were adjusted to 1 × 107 cells mL−1 (standard unless otherwise specified) by spectrophotometry and confirmed by hemocytometric counting.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC was determined by a broth microdilution assay in accordance with the CLSI guidelines78. Briefly, C. albicans suspensions (1 × 103 cells mL−1) were treated with fluconazole, C12AHL or both using a checker-board approach (C12AHL: 12.5 µg mL−1–100 µg mL−1 and Fluconazole: 0.078 µg mL−1–80 µg mL−1) and incubated in a 96-well microtiter plate for 24 h at 37 °C. At the end of this incubation, the optical density of the fungal growth was measured spectrometrically at 595 nm and MICs were determined. The MIC50 and MIC80 were defined as the lowest concentration of the tested agent that inhibited 50% and 80%, respectively, of fungal growth compared to solvent controls. The assay was performed as quadruplicates three separate times (n = 12).

Treatment groups and doses

Three test groups (fluconazole, C12AHL, fluconazole+C12AHL) and one solvent control group (DMSO; the solvent for C12AHL and fluconazole) were used. Following concentrations were used throughout the study unless otherwise specified; 1.25 µg mL−1 fluconazole, 50 µg mL−1 C12AHL, 1.25 µg mL−1 fluconazole + 50 µg mL−1 C12AHL, or DMSO (Control, 2% V/V). The chosen concentration of fluconazole is the minimum concentration required to inhibit 80% of C. albicans cells (MIC80). A sub-growth and sub-hyphal inhibitory concentration of C12AHL (50 µg mL−1, 168 µM)28 was chosen to prevent growth or hyphae development associated effects on C. albicans.

Drug efflux activity assay

The activity of C. albicans drug efflux pumps when treated with C12AHL and/or fluconazole was assessed using an indicator dye, rhodamine 6 g (R6G), as described by Holmes, A. R. et al. 201879. Briefly, standard suspensions of C. albicans SC5314 and mutant strains DSY448, DSY465, DSY654, DSY1050, DSY1751, DSY1764 and DSY1769 were prepared in PBS and starved for 2 h at room temperature (25 °C). R6G was added (10 µM final concentration) and incubated in dark conditions for further 1 h at 37 °C and 200 rpm. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS, resuspended and 100 µl was added to wells in a 96 well plate. Rhodamine 6 g loaded C. albicans were treated with either fluconazole, C12AHL, C12AHL + fluconazole, or DMSO and the plate was incubated at 37 °C in the dark. After 5 min of post-treatment, 1 mM glucose was added to each well and further incubated. The cell suspensions were removed at given time points (every 10 min up to 1 h, hourly up to 5 h, 18 h, and 24 h), centrifuged (10 min, 13000 rpm, 25 °C), and the amount of R6G released into the supernatant was read using a spectrophotometer at 485 nm excitation/535 nm emission. Each assay was conducted in sextuplicate at 3 different occasions (n = 18).

Gene expression analyses

Next generation sequencing (RNA-Seq)

Changes in the C. albicans transcriptome were assessed with next generation sequencing (RNA-Seq). C. albicans SC5314 standard suspension was prepared as described above, treated with either fluconazole, C12AHL, C12AHL + fluconazole, or DMSO and incubated at 37 °C statically for 24 h. Cells were washed 3 times in PBS and total RNA was extracted using the SV total RNA isolation system (Catalog No. Z3100, Promega, Madison, WI). Three biological replicates were processed for each treatment group. RNA-Seq libraries were prepared using Illumina ScriptSeq Complete Gold (Yeast) Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. One µg of total RNA from each sample was used for library preparation. All libraries were sequenced 2 ×150 bp high output v2 kit (100 Gb) on the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform.

Reads were mapped to the Candida genome using the RNA-seq processing pipeline STAR v2.5.2a80 in AlignReads mode with a maximum intron size of 30Kb. Gene expression was quantified by counting reads using htseq v0.6.180 for all genes in the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org, Stanford Genome Technology Centre) gene model C. albicans SC5314 version A22-s07-m01-r30. RNA-Seq data was analyzed in R v3.6.1 (https://www.R-project.org/)81 by broadly exploring differences between samples using principle component analysis after normalizing read counts into centered log ratio values. Statistical comparison of gene expression between treatment types was performed using PERMANOVA. Differentially expressed genes were then identified using DESeq. 2 v1.14.182, with the sample group set as the design formula and contrasts between groups used to identify differentially abundant genes, and visualized using EnhancedVolcano v1.2.0 (https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano)83. The Candida genome database was used to determine pathways affected by the different treatments, using an adjusted p-value < 1e−5 as the cut-off for statistically significant gene expression comparison.

Real‐time PCR assay

Changes in the expression of CDR1, CDR2 and MDR1 (the genes coding C. albicans drug efflux pumps) when exposed to fluconazole, C12AHL or C12AHL + fluconazole for a shorter duration (1 h) were quantitatively assessed by real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). C. albicans SC5314 suspensions (1 × 103 cells mL−1) were prepared as mentioned above and treated with fluconazole, C12AHL or both (C12AHL + fluconazole) for 1 h at 37 °C in static conditions. Cells were harvested, washed 3 times with PBS, and RNA was extracted using the SV total RNA isolation system (Catalog No. Z3100, Promega, Madison, WI) using 2 μg template for reverse transcription with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). qPCR was performed as described previously84 using primers shown in Supplementary Table S16. Relative gene expression was quantified using EFB1 as the housekeeping (reference) gene85. All experiments were carried out in duplicate on three different occasions (n = 6).

Protein expression analysis

The changes in C. albicans protein expression when treated with C12AHL + fluconazole compared to fluconazole were assessed with 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. C. albicans SC5314 standard suspension was prepared as described above, treated with either fluconazole or C12AHL + fluconazole and incubated at 37 °C statically for 24 h. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed 3 times with PBS and total protein were extracted, after which first‐ and second-dimension electrophoreses were performed as described previously84. Protein gels derived from three biological replicates (with three technical replicates) from each group were analysed using a two‐dimensional analysis software (PD Quest; Bio‐Rad Laboratories). Protein spots were identified using default settings and verified manually to eliminate background noise and artefacts. Only consistent and reproducible protein spots (in all replicates) were progressed for further analysis, and spots that were missing in either fluconazole or fluconazole + C12AHL samples (in all replicates) were considered as differentially expressed in C. albicans in response to respective exposure84.

Proteins that were differentially expressed were in-gel digested, peptides were extracted and subjected to tandem mass spectrometry as described previously84. Briefly, matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization time‐of‐flight mass spectroscopy/mass spectroscopy (MALDI TOF MS/MS) was performed using a Bruker Autoflex III MALDI TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and Dionex UltiMate 3000 nano‐LC system using a 50‐Hz frequency laser beam. Candidate proteins were identified in the NCBI nr database using Mascot software (http://www.matrixscience.com/) (parameters used: Type of search: MS/MS Ion Search, Enzyme: Trypsin/P, Fixed modifications: Carbamidomethyl (C), Variable modifications: Oxidation (M), Mass values: Monoisotopic, Protein Mass: Unrestricted, Peptide Mass Tolerance: ±50 ppm, Fragment Mass Tolerance: ±0.5 Da, Max Missed Cleavages: 1, Instrument type: MALDI‐TOF‐TOF). Protein scores were derived from ion scores as a non‐probabilistic basis for ranking the protein hits at a significance level of p-value < 0.0584. Identified proteins were functionally characterized, and encoding genes were determined using the Candida genome database, NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SWISSPROT and TrEMBL non‐redundant protein databases (http://www.expasy.ch/sport/)84.

Statistical analyses

All other assays not mentioned in the sections above were performed using nonparametric Mann—Whitney U-tests with SPSS software (version 16.0) for comparison of test conditions to corresponding control groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Nicola Angel (Australian Centre for Ecogenomics, the University of Queensland, Australia) for her assistance in RNA-Seq and Associate Professor Dominique Sanglard (the University Hospital Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing C. albicans mutant strains.

Author contributions

H.M.H.N.B. and L.P.S. conceptualized the study; H.M.H.N.B., B.P.K.C. and D.L.A.W. designed the experiments; H.M.H.N.B. and B.P.K.C. performed experiments; H.M.H.N.B., I.V., B.P.K.C., D.L.A.W., P.H. and L.P.S. analyzed and interpreted data; H.M.H.N.B., D.L.A.W. and I.V. wrote the manuscript; I.V., P.H. and L.P.S. revised the manuscript.

Data availability

Sequencing data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRNA) under Bio Project Accession No. PRJNA599446. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/599446).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-64761-3.

References

- 1.Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;69:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhamgaye S, Qu Y, Peleg AY. Polymicrobial infections involving clinically relevant Gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1716–1722. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalan L, Grice EA. Fungi in the Wound Microbiome. Adv. Wound Care. 2018;7:247–255. doi: 10.1089/wound.2017.0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chellan G, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of fungi infecting deep tissues of lower-limb wounds in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2097–2102. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02035-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowd SE, et al. Survey of fungi and yeast in polymicrobial infections in chronic wounds. J. Wound Care. 2011;20:40–47. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2011.20.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay E, et al. Candida colonization of the respiratory tract and subsequent Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129:110–117. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamet M, et al. Candida spp. airway colonization could promote antibiotic-resistant bacteria selection in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1272–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro J, et al. Factors associated with poor pulmonary function: cross-sectional analysis of data from the ERCF. European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2001;18:298–305. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00068901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klotz SA, Chasin BS, Powell B, Gaur NK, Lipke PN. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections involving Candida species: analysis of patients and review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;59:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esim Buyukbayrak E, et al. Diagnosis of vulvovaginitis: comparison of clinical and microbiological diagnosis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;282:515–519. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchta V, Spacek J. Microbiological findings in patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in the Hradec Kralove Faculty Hospital 1995-2002. Ceska Gynekol. 2004;69:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cumming CG, Wight C, Blackwell CL, Wray D. Denture stomatitis in the elderly. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 1990;5:82–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1990.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pammi M, Zhong D, Johnson Y, Revell P, Versalovic J. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections in the neonatal intensive care unit are associated with increased mortality: a case-control study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014;14:390. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandara HM, Lam OL, Jin LJ, Samaranayake L. Microbial chemical signaling: a current perspective. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;38:217–249. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.652065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diggle SP, Crusz SA, Camara M. Quorum sensing. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R907–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuqua, W. C., Winans, S. C. & Greenberg, E. P. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J. Bacteriol.176, 269–275, 10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Whitehead NA, Barnard AM, Slater H, Simpson NJ, Salmond GP. Quorum-sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2001;25:365–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fourie R, et al. Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Interaction, with Focus on the Role of Eicosanoids. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:64. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Azizi MA, Starks SE, Khardori N. Interactions of Candida albicans with other Candida spp. and bacteria in the biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;96:1067–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAlester G, O’Gara F, Morrissey JP. Signal-mediated interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:563–569. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickerson KW, Atkin AL, Hornby JM. Quorum sensing in dimorphic fungi: farnesol and beyond. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2006;72:3805–3813. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02765-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cugini C, et al. Farnesol, a common sesquiterpene, inhibits PQS production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:896–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis-Hanna A, Piispanen AE, Stateva LI, Hogan DA. Farnesol and dodecanol effects on the Candida albicans Ras1-cAMP signalling pathway and the regulation of morphogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67:47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hornby JM, Nickerson KW. Enhanced production of farnesol by Candida albicans treated with four azoles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2305–2307. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2305-2307.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirtliff ME, et al. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2392–2401. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01551-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma M, Prasad R. The quorum-sensing molecule farnesol is a modulator of drug efflux mediated by ABC multidrug transporters and synergizes with drugs in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4834–4843. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00344-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cernakova L, Dizova S, Gaskova D, Jancikova I, Bujdakova H. Impact of Farnesol as a Modulator of Efflux Pumps in a Fluconazole-Resistant Strain of Candida albicans. Microb. Drug. Resist. 2019 doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hogan DA, Vik A, Kolter R. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1212–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall RA, et al. The quorum-sensing molecules farnesol/homoserine lactone and dodecanol operate via distinct modes of action in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2011;10:1034–1042. doi: 10.1128/EC.05060-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandara HMHN, Hewavitharana AK, Shaw PN, Smyth HDC, Samaranayake LP. A novel, quorum sensor-infused liposomal drug delivery system suppresses Candida albicans biofilms. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;578:119096. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkow EL, Lockhart SR. Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: a current perspective. Infect. Drug. Resist. 2017;10:237–245. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S118892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannon, R. D. et al. Efflux-mediated antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 22, 291-321, Table of Contents, 10.1128/CMR.00051-08 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay K, et al. Membrane sphingolipid-ergosterol interactions are important determinants of multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1778–1787. doi: 10.1128/aac.48.5.1778-1787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasrija R, Panwar SL, Prasad R. Multidrug transporters CaCdr1p and CaMdr1p of Candida albicans display different lipid specificities: both ergosterol and sphingolipids are essential for targeting of CaCdr1p to membrane rafts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:694–704. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00861-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peleg AY, Hogan DA, Mylonakis E. Medically important bacterial-fungal interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, O’May GA, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. Polymicrobial interactions: impact on pathogenesis and human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25:193–213. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ovchinnikova ES, Krom BP, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Force microscopic and thermodynamic analysis of the adhesion between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans. Soft Matter. 2012;8:6454–6461. doi: 10.1039/C2SM25100K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogan DA, Kolter R. Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science. 2002;296:2229–2232. doi: 10.1126/science.1070784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlton, T. S. et al. A novel and sensitive method for the quantification of N-3-oxoacyl homoserine lactones using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: application to a model bacterial biofilm. Env. Microbiol.2, 530–541, 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00136.x (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Trejo-Hernandez A, Andrade-Dominguez A, Hernandez M, Encarnacion S. Interspecies competition triggers virulence and mutability in Candida albicans-Pseudomonas aeruginosa mixed biofilms. ISME J. 2014;8:1974–1988. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gbelska Y, Toth Hervay N, Dzugasova V, Konecna A. Measurement of Energy-dependent Rhodamine 6G Efflux in Yeast Species. Bio-protocol. 2017;7:e2428. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maesaki S, Marichal P, Vanden Bossche H, Sanglard D, Kohno S. Rhodamine 6G efflux for the detection of CDR1-overexpressing azole-resistant Candida albicans strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1999;44:27–31. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boon C, et al. A novel DSF-like signal from Burkholderia cenocepacia interferes with Candida albicans morphological transition. ISME J. 2008;2:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Kuhn DM, Ghannoum MA. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:4333–4340. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4333-4340.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holcombe LJ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted factors impair biofilm development in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 2010;156:1476–1486. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharya, S., Esquivel, B. D. & White, T. C. Overexpression or Deletion of Ergosterol Biosynthesis Genes Alters Doubling Time, Response to Stress Agents, and Drug Susceptibility in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. MBio9, 10.1128/mBio.01291-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Albertsen L, et al. Diversion of flux toward sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by fusion of host and heterologous enzymes. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2011;77:1033–1040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vale-Silva LA, et al. Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Δ(5),(6)-desaturase gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1960–1968. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05720-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lupetti A, Danesi R, Campa M, Del Tacca M, Kelly S. Molecular basis of resistance to azole antifungals. Trends Mol. Med. 2002;8:76–81. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henry KW, Nickels JT, Edlind TD. Upregulation of ERG genes in Candida species by azoles and other sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2693–2700. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.10.2693-2700.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mollinedo F. Lipid raft involvement in yeast cell growth and death. Front. Oncol. 2012;2:140. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kodedova M, Sychrova H. Changes in the Sterol Composition of the Plasma Membrane Affect Membrane Potential, Salt Tolerance and the Activity of Multidrug Resistance Pumps in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song JL, Harry JB, Eastman RT, Oliver BG, White TC. The Candida albicans lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase (ERG11) gene promoter is maximally induced after prolonged growth with antifungal drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1136–1144. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1136-1144.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogers, P. D. & Barker, K. S. Genome-wide expression profile analysis reveals coordinately regulated genes associated with stepwise acquisition of azole resistance in Candida albicans clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.47, 1220–1227, 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1220-1227.2003 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Yang H, et al. Structural mechanism of ergosterol regulation by fungal sterol transcription factor Upc2. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silver PM, Oliver BG, White TC. Role of Candida albicans transcription factor Upc2p in drug resistance and sterol metabolism. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:1391–1397. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1391-1397.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin SW, Konopka JB. Lipid raft polarization contributes to hyphal growth in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2004;3:675–684. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.675-684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu TT, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of the response to azole, polyene, echinocandin, and pyrimidine antifungal agents in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2226–2236. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2226-2236.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warnecke D, et al. Cloning and functional expression of UGT genes encoding sterol glucosyltransferases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, Pichia pastoris, and Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13048–13059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enjalbert B, et al. Role of the Hog1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1018–1032. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ralser M, et al. Metabolic reconfiguration precedes transcriptional regulation in the antioxidant response. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:604–605. doi: 10.1038/nbt0709-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petti AA, Crutchfield CA, Rabinowitz JD, Botstein D. Survival of starving yeast is correlated with oxidative stress response and nonrespiratory mitochondrial function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E1089–1098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101494108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, et al. Cap1p is involved in multiple pathways of oxidative stress response in Candida albicans. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chechik G, et al. Activity motifs reveal principles of timing in transcriptional control of the yeast metabolic network. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1251–1259. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee J, et al. Yap1 and Skn7 control two specialized oxidative stress response regulons in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16040–16046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minard KI, McAlister-Henn L. Sources of NADPH in yeast vary with carbon source. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:39890–39896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Minard KI, McAlister-Henn L. Antioxidant function of cytosolic sources of NADPH in yeast. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:832–843. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christensen B, Gombert AK, Nielsen J. Analysis of flux estimates based on (13)C-labelling experiments. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:2795–2800. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hwang CS, et al. Copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase (Cu/ZnSOD) is required for the protection of Candida albicans against oxidative stresses and the expression of its full virulence. Microbiology. 2002;148:3705–3713. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li L, Naseem S, Sharma S, Konopka JB. Flavodoxin-Like Proteins Protect Candida albicans from Oxidative Stress and Promote Virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005147. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cowen LE, et al. Population genomics of drug resistance in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9284–9289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102291099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sen M, et al. UDP-glucose 4, 6-dehydratase activity plays an important role in maintaining cell wall integrity and virulence of Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002384. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Skrzypek, M. S. et al. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res.45, D592–D596, 10.1093/nar/gkw924 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]