Abstract

Background

Telerehabilitation, an emerging method, extends rehabilitative care beyond the hospital, and facilitates multifaceted, often psychotherapeutic approaches to modern management of patients using telecommunication technology at home or in the community. Although a wide range of telerehabilitation interventions are trialed in persons with multiple sclerosis (pwMS), evidence for their effectiveness is unclear.

Objectives

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of telerehabilitation intervention in pwMS for improved patient outcomes. Specifically, this review addresses the following questions: does telerehabilitation achieve better outcomes compared with traditional face‐to‐face intervention; and what types of telerehabilitation interventions are effective, in which setting and influence which specific outcomes (impairment, activity limitation and participation)?

Search methods

We performed a literature search using the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the Central Nervous System Review Group Specialised Register( 9 July, 2014.) We handsearched the relevant journals and screened the reference lists of identified studies, and contacted authors for additional data.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) that reported telerehabilitation intervention/s in pwMS and compared them with some form of control intervention (such as lower level or different types of intervention, minimal intervention, waiting‐list controls or no treatment (or usual care); interventions given in different settings) in adults with MS.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies and extracted data. Three review authors assessed the methodological quality of studies using the GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008) for best‐evidence synthesis. A meta‐analysis was not possible due to marked methodological, clinical and statistical heterogeneity between included trials and between measurement tools used. Hence, we performed a best‐evidence synthesis using a qualitative analysis.

Main results

Nine RCTs, one with two reports, (N = 531 participants, 469 included in analyses) investigated a variety of telerehabilitation interventions in adults with MS. The mean age of participants varied from 41 to 52 years (mean 46.5 years) and mean years since diagnosis from 7.7 to 19.0 years (mean 12.3 years). The majority of the participants were women (proportion ranging from 56% to 87%, mean 74%) and with a relapsing‐remitting course of MS. These interventions were complex, with more than one rehabilitation component and included physical activity, educational, behavioural and symptom management programmes.

All studies scored 'low' on the methodological quality assessment. Overall, the review found 'low‐level' evidence for telerehabilitation interventions in reducing short‐term disability and symptoms such as fatigue. There was also 'low‐level' evidence supporting telerehabilitation in the longer term for improved functional activities, impairments (such as fatigue, pain, insomnia); and participation measured by quality of life and psychological outcomes. There were limited data on process evaluation (participants'/therapists' satisfaction) and no data available for cost effectiveness. There were no adverse events reported as a result of telerehabilitation interventions.

Authors' conclusions

There is currently limited evidence on the efficacy of telerehabilitation in improving functional activities, fatigue and quality of life in adults with MS. A range of telerehabilitation interventions might be an alternative method of delivering services in MS populations. There is insufficient evidence to support on what types of telerehabilitation interventions are effective, and in which setting. More robust trials are needed to build evidence for the clinical and cost effectiveness of these interventions.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Middle Aged, Telemedicine, Multiple Sclerosis, Multiple Sclerosis/rehabilitation, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Telerehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis

Review questions

Does telerehabilitation achieve better outcomes in persons with multiple sclerosis compared with traditional face‐to‐face intervention? What types of telerehabilitation interventions are effective, in which setting and influence which specific outcomes?

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common disease of the nervous system among young adults, with no cure and causing long‐term disability. Rehabilitation provides treatments and therapies to lessen the impact of any disability and improve function. Despite recent advances in MS care including rehabilitation, many people with MS are unable to access these developments due to limited mobility, fatigue and related issues, and costs associated with travel.Telerehabilitation is a newer approach to delivering rehabilitation programmes at the patient’s home or in the community, using telecommunication technology such as phone lines, video technology, internet applications and others. A wide range of telerehabilitation interventions are trialed in persons with multiple sclerosis, however, evidence for their effectiveness is still unclear.

Study characteristics

This review looked for evidence on how telerehabilitation interventions work in adults with MS. We searched widely for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), a particular kind of study where participants are placed in treatment groups by chance (that is, randomly) because in most settings these provide the highest quality evidence. We were interested in studies that compared a telerehabilitation programme with standard or minimal care, or with different kinds of rehabilitation programmes.

Key results

We found nine relevant RCTs covering 531 participants (469 included in the analyses), evaluating a wide variety of telerehabilitation interventions in persons with MS. The telerehabilitation interventions evaluated were complex, with more than one rehabilitation component and included physical activity, educational, behavioural and symptom management programmes. These interventions had different purposes and used different technologies, so a single overall definite conclusion was not possible. The methodological quality of the included studies is low and varied among the studies.

Quality of evidence

There was 'low‐quality' evidence from the included RCTs to support the benefit of telerehabilitation in reducing short‐term disability and managing symptoms such as fatigue in adults with MS. We found limited evidence to support the benefit of telerehabilitation interventions in improving disability, reducing symptoms and improving quality of life in the longer term. Furthermore, the interventions and outcomes being investigated in the included studies were different to each other. No studies reported any serious harm from telerehabilitation and there was no information on the associated costs.

There is a need for further research to assess the effects of the range of telerehabilitation techniques and to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of these interventions in people with MS. The evidence in this review is up to date to July 2014.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Telerehabilitation for persons with multiple sclerosis | |||

|

Patient or population: People with multiple sclerosis Settings: Participants' home, MS regional centres Intervention: Telerehabilitation Comparison: Standard care in rehabilitation centres, participants in wait‐list, other type/intensity of rehabilitation intervention |

|||

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) | Effect of telerehabilitation interventions for people with multiple sclerosis | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) # |

| Change in functional activity | |||

| Change in disability directly post‐intervention Measures: GLTEQ, DGI, BBS, ARAT, NHPT, 25FWT, CES, VPR Follow‐up: depended on the type of intervention; range from (1 month – 12 weeks) | 232 (intervention group = 122) (6 studies) | Two studies (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011, N = 99) with same cohort of participants showed significant improvement in physical activity in the treatment group at post‐intervention assessment as measured by GLTEQ (P < 0.01). Weekly step count (pedometer) increased significantly in the treatment group at post‐intervention assessment (P < 0.001) One study (Frevel 2014, N = 18) showed significant improvement in dynamic and static balance capacity compared to baseline values in both intervention group (e‐training) (DGI: P = 0.016, BBS: P = 0.011) and control (hippotherapy) group (DGI: P = 0.011, BBS: P = 0.011). There was no difference between groups One study (Huijgen 2008, N = 35) showed no statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups in arm function as measured by ARAT (mean change 1.26, 90% CI ‐1.90 to 4.42) and NHPT (mean change 7.24, 90% CI ‐6.55 to 23.25) One study (Paul 2014, N = 30) showed that gait speed measured using 25FWT increased in the intervention group compared to the control group but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.170); and the intervention group showed a statistically significant improvement in the physical subscale of the MSIS (P = 0.048) One study (Gutíerrez 2013a, N = 50) showed improvements in balance and postural control, with a significant increase in CES of the intervention group (mean change; 8.21 points, P < 0.001), but no significant improvement in the control group (mean change: 1.93, P = 0.123). Visual Preference Ratio (VPR) and the contribution of vestibular information (Vestibular Ratio) improved significantly in the intervention group (P < 0.001), but not in the control group (P > 0.05). There were significant post‐treatment differences between treatment and control groups in the CES (F = 37.873, P < 0.001) and the VPR (F = 12.156, P < 0.001). Significant post‐treatment differences between groups were also found for the ability to accept incorrect visual information expressed by the visual conflict parameter (F = 15.05, P < 0.000). There were no significant between‐group differences in the contribution of the visual system (F = 2.64, P = 0.11) or use of somatosensory information (F = 0.117, P = 0.734) in the maintenance of balance and stability |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

| Change in short‐term disability 3 months or less after the start of the intervention Measures: GLTEQ Follow‐up: up to 3 months | 45 (intervention group = 22) (1 study) | One study (Dlugonski 2012, N = 45) reported that the treatment group showed a significant increase in physical activity at 3‐month follow‐up compared to the control group as measured by GLTEQ (P < 0.001). There was a non‐significant change in assessment scores from post‐intervention to 3‐month follow‐up (P = 0.61) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 |

|

Change in long‐term disability more than 3 months after the intervention Measure:6MWT Follow‐up: 6 months – 2 years |

82 (intervention group = 41) (1 study with 2 reports) | One study with 2 reports (Pilutti 2014, N = 82) showed a significant and positive effect of the intervention on increase in 6MWT distance relative to those in the control group (P = 0.07). Physical activity increased most in those with mild disability in the intervention group. | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 |

| Change in symptoms or impairments | |||

|

Change in impairments directly post‐intervention

Measures: FIS, FSS, MFIS, MS Symptom Cheklist Follow‐up: depended on the type of intervention; range from (1 month – 12 weeks) |

265 (intervention group = 138) (4 studies) | One study (Finlayson 2011, N = 190) showed a significant reduction in fatigue in intervention group compared to a wait‐list control group immediately after intervention as measured by FIS sub‐scales (Mean (SD): Cognitive ‐3.12 (6.1), P = 0.001; Physical ‐2.53 (6.4), P = 0.014; Social ‐6.01 (12.1), P = 0.002) One study (Egner 2003, N = 27) reported similar fatigue scores (measured using FSS) for all 3 groups (video, telephone and standard care) at 9 weeks post‐intervention; however the video group had significantly lower scores than the other 2 groups at month 6 (P < 0.05; telephone: SE = 0.478; standard care: SE = 0.536) and month 18 (P < 0.05; telephone: SE = 0.569; standard care: SE = 0.624) One study (Frevel 2014, N = 18) reported that fatigue improved significantly in the control (hippotherapy) group (P < 0.05 for all MFIS subscales); while the e‐training group improved only on the MFIS cognitive subscale (P = 0.031). A significant difference between the groups was noted only in the cognitive subscale of the MFIS ( P = 0.012) One study (Paul 2014, N = 30) reported no improvements in symptoms as measured by MS Symptom Checklist. |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 |

| Change in short‐term impairments 3 months or less after the start of the intervention Measures: FIS Follow‐up: up to 3 months | 190 (intervention group = 94) (1 study) | One study (Finlayson 2011, N = 190) showed a reduction in fatigue at 3 months with large effect size as measured by FIS subscales (ES (95% CI): Cognitive 0.58 (0.48 to 0.68); Physical 0.68 (0.55 to 0.82); Social 0.65 (0.53 to 0.77) and FSS scores: ‐0.38 (‐0.45 to ‐0.31)) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 |

|

Change in long‐term impairments more than 3 months after the intervention Measures: FIS, FSS Follow‐up: 6 months – 2 years |

299 (intervention group = 155) (3 studies) | One study (Egner 2003, N = 27) showed a reduction of fatigue measured by FSS in those using video telerehabilitation compared with those using telephone telerehabilitation or standard care groups at 6 months (P < 0.05; telephone: SE = 0.478; standard care: SE = 0.536) and 18 months (P < 0.05; telephone: SE = 0.569; standard care: SE = 0.624). At 12 months follow‐up, there was a significant difference in fatigue scores between the video and standard care groups (P < 0.05; SE = 0.471) One study with 2 reports (Pilutti 2014, N = 82) showed a significant and positive effect of the intervention on fatigue severity (FSS, P = 0.001) and its physical impact (FIS, P = 0.008) at 6‐month post‐intervention. The results also indicated a favourable effect of the intervention on symptoms of pain (MPQ, P =. 0.08) and sleep quality post‐trial (PSQI, P = 0.06), although the differences between groups did not reach statistical significance One study (Finlayson 2011, N = 190) showed reduction in fatigue at 6 months with a large effect size as measured by FIS subscales (ES (95% CI): Cognitive 0.55 (0.46 to 0.64); Physical 0.61 (0.50 to 0.72); Social 0.67 (0.58 to 0.76) and FSS score:: ‐0.33 (‐0.36 to ‐0.30)) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 |

| Change in participation | |||

|

Change in psychological outcomes Measures:CES‐D, HADS, SDMT Follow‐up: variable (range 1 month – 2 years) |

139 (intervention group = 76) (3 studies) |

One study (Egner 2003, N = 27) showed no significant difference in depressive symptoms measured by CES‐D at end of the intervention period (9 weeks). Mean depression scores were lower in those receiving telerehabilitation by video compared with telephone and standard care group symptoms decreased at 6, 8 and 24 months follow‐up. Being male was a significant predictor for an increased depression score at every measurement point except at 24 months (P < 0.05). Mean CES‐D scores fluctuated throughout each measurement point for all groups, but seemed to decrease at 24 months in all 3 groups, but not statistically significant. Mean depression scores were lower in those receiving telerehabilitation by video compared to telephone and standard care groups and depressive symptoms also decreased at the 6‐, 8‐ and 24‐month follow‐ups, but this was not significantly different between groups. One study (Paul 2014, N = 30) reported a small non‐significant improvement in anxiety measured by HADS in the control group compared with the treatment group at post‐treatment (8 ‐ 9 weeks) (P = 0.016) One study with two reports (Pilutti 2014, N = 82) showed a statistically significant group interaction in psychological outcomes on SDMT scores (F = 5.68, P = 0.02), which was moderate in magnitude (partial eta squared (ɳ₂) = 0.08). There was a clinically meaningful improvement in SDMT scores in the subgroup with mild disability in the intervention condition (∼ 6 points increase, moderate effect size (d) = 0.41), whereas those with moderate disability in the intervention condition demonstrated minimal change (∼ 1 point decrease, d = 0.12). There were minimal changes in SDMT scores for those with both mild or moderate disability (∼ 1 point increase, d = 0.10 for both) in the control group. There was also significant improvement in depression and anxiety in the intervention group (with large effect size (ɳ₂ = 0.10 for both) compared with the control group measured by the HADS (depression: F =7.90, P = 0.006; anxiety: F = 8.00, P = 0.006) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 |

|

Change in quality of life Measures: QWB, HAQUAMS, MSIS‐29, SF‐36, LMSQOLS, Follow‐up: variable (range 1 month – 2 years) |

392 (intervention group = 201) (6 studies, 1 with 2 reports) |

One study (Egner 2003, N = 27) reported no significant difference in QoL measured using QWB at the end of the intervention period (9 weeks). Mean QWB scores for each measurement point (6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months) were higher (indicating higher QoL) for those in the video group than for the standard care and telephone groups, but were significantly better in the video group compared to the telephone group at month 12 only (P < 0.05; SE = 0.023). The telephone group and standard care groups reported similar mean QWB scores over the 2‐year follow‐up period. One study (Frevel 2014, N = 18) showed significant improvement in QoL measured by HAQUAMS (cognition: P = 0.026; function of lower limb: P = 0.008; mood: P = 0.045) in the control group (hippotherapy), but not in the intervention group (e‐training) One study (Dlugonski 2012, N = 45) showed non‐significant condition‐by‐time interactions for QoL measured by MSIS‐29. There was no significant correlation between changes in QoL from base line to post‐intervention in either the treatment or control groups One study (Finlayson 2011, N = 190) showed that significant improvement in HRQoL in the intervention group on the SF‐36 subscales except the physical functioning and bodily pain subscales: change score (95% CI): Vitality 6.99 (4.29 to 9.69); Role Emotion 10.08 (4.13 to 16.04); Mental Health 5.78 (3.89 to 7.67); Social Function 7.95 (4.09 to 11.82); General Health 3.61 (1.37 to 5.85); Role Physical 11.12 (6.22 to 16.02) One study (Paul 2014, N = 30) reported non‐significant improvement in HRQoL measured by LMSQOLS in the treatment group compared with control group post‐treatment (8 ‐ 9 weeks) (mean difference ‐0.07 vs 1.0) One study with 2 reports (Pilutti 2014, N = 82) reported that participants in the intervention group perceived a positive change in physical HRQoL measured by MSIS‐29 (P = 0.06) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7 |

| Change in other outcomes | |||

| Cost effectiveness | 531 (intervention group = 277) (9 studies) | Not measured in any of the studies | See 'Impact' |

|

Process evaluation (user satisfaction) Measures: Self‐designed Likert scale, VAS scale Follow‐up: variable (range 1 ‐ 3 months) |

80 (intervention group =46) (2 studies) |

One study (Dlugonski 2012, N = 45) showed that participants were most satisfied with (mean ± SD): the overall programme: 4.8 ± 0.4, staff: 4.9 ± 0.2 and pedometer: 4.7 ± 0.6, but slightly less satisfied with the website itself: 4.1 ± 0.9 One study (Huijgen 2008, N = 35) reported that overall, both participants and therapists were satisfied with the intervention (over 55% in all 6 items). Both participants and therapists were less satisfied with the aesthetic aspect of the system and had difficulty completing tasks |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low8 |

| Serious adverse events | 531 (intervention group = 277) (9 studies) | No serious adverse events reported | See 'Impact' |

| Caregivers‐related outcomes | 531 (intervention group = 277) (9 studies) | Not measured in any of the studies | See 'Impact' |

| ARAT: Action Research Arm Test; CES: Composite Equilibrium Score; CES‐D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CI: Confidence interval;DGI: Dynamic Gait Index; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; ES: Effect size; FIS: Fatigue Impact Scale; FSS: Fatigue Severity Score; GLTEQ: Godin Leisure‐Time Exercise Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAQUAMS: Hamburg QoL Questionnaire in MS; HRQoL: Health related quality of life; IQR: inter quartile range; LMSQOLS: Leeds MS Quality of Life Scale; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; MS: Multiple Sclerosis;MSIS‐29: MS Impact Scale; NHPT: Nine Hole Peg Test; PSQI: Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index;QoL: quality of life; QWB: Quality of Well‐ Being Scale; SD: Standard deviation; SDMT: Symbol Disit Modalities Test; SE: Standard Error; SF‐36: 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey; SOT: Sensory organisation Test; VPR: Visual Preference Ratio; 6MWT: 6 Meters Waltk Test;25FWT: 25 Feet Walk Test; 95% CI: 95 percent confidence interval | |||

| # GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1Methods of randomisation not described or poorly described in 4 studies, only 1 study reported blinding of the assessor, and allocation concealment was described in only 1 study

2Unclear randomisation procedure, allocation concealment not reported, no blinding of the participants or assessors

3Methods of randomisation not described or poorly described in 1 study, none of the studies reported blinding of the participants or assessor, and allocation concealment was not described or unclear in 2 studies

4No blinding of the participants or assessors, high risk of attrition bias (> 20% drop‐out)

5Methods of randomisation and allocation concealment not described or poorly described in 2 studies, all 3 studies did not report blinding of the participants or assessor

6Methods of randomisation not described or poorly described in 2 studies, none of the studies reported blinding of the participants or assessor and allocation concealment procedure

7Methods of randomisation not described or poorly described in 3 studies, allocation concealment procedure described only in 2 studies, and none of the studies reported blinding of the participants or assessor

8Methods of randomisation and allocation concealment procedure not described or poorly described, and blinding of the participants or assessor not reported in both studies

Background

Description of the condition

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological disease, characterised by patchy inflammation, gliosis and demyelination within the central nervous system (CNS), that affects approximately 1.3 million people worldwide (WHO 2008). The median estimated incidence of MS globally is 2.5 per 100,000 (with a range of 1.1 to 4) (WHO 2008), the prevalence is about 30 per 100,000 population (range 5 to 80), with a female preponderance (female to male ratio of 3:1) (Trisolini 2010; WHO 2008).

The patterns of presentation in MS are heterogeneous and include: ‘relapsing remitting’ (RR) MS (85%), characterised by exacerbations and remissions; ‘secondary progressive’ (SP) MS with progressive disability acquired between attacks (in 70% to 75% who start with RR, it is estimated more than 50% will develop SPMS within 10 years, and 90% within 25 years); ‘primary progressive’ (PP) MS (10%), where persons develop progressive disability from the onset; and ‘progressive relapsing’ (PR) MS (5%), where persons begin worsening gradually and subsequently start to experience discrete attacks (MS Australia 2012; Weinshenker 1989). The prognosis in MS is variable and difficult to predict, and depends on the type, severity and location of demyelinating lesions within the CNS (Hammond 2000; MS Australia 2012). Various factors such as older age at onset, progressive disease course, multiple onset symptoms, pyramidal or cerebellar symptoms and a short interval between onset and first relapse are associated with worse prognosis (Hammond 2000). Persons with MS (pwMS) have a prolonged median survival time from the time of diagnosis of approximately 40 years (Weinshenker 1989). Therefore, issues related to progressive disability (physical and cognitive), psychosocial adjustment and social re‐integration progress over time. These have implications for pwMS, their carers, treating clinicians and society as a whole, in terms of healthcare access, provision of services and financial burden (Pfleger 2010; Trisolini 2010).

The pwMS can present with various combinations of deficits such as physical (motor weakness, spasticity, sensory dysfunction, visual loss, ataxia), fatigue, pain (neurogenic, musculoskeletal and mixed patterns), incontinence (urinary urgency, frequency), cognitive (memory, attention), psychosocial, behavioural and environmental problems, which limit a person’s activity (function) and participation (Khan 2007). Cognitive and behavioural problems can be subtle and often precede physical disability requiring long‐term care (Beer 2012). The care needs in this population are complex due to cumulative effects of the impairments and disabilities, the ‘wear and tear’ and the impact of aging with a disability. Longer‐term multidisciplinary management is recommended, both in hospital and in community settings to maintain functional gains and social re‐integration (participation) over time (Khan 2007; Khan 2010a; WHO 2008). Despite recent advances in MS management, many pwMS are unable to access these developments due to limited mobility, fatigue and related issues, plus costs associated with travel. With increasing financial constraints on healthcare systems, alternative methods of service delivery in the community and over a longer term are now a priority. Telerehabilitation for pwMS has potential as a tool to improve health care with reduction in care costs (Zissman 2012). The emerging advances in information and communication technology (ICT) may present as an alternative efficient and cost‐effective method to deliver rehabilitation treatment in a setting convenient to the patient, such as their home.

Description of the intervention

The terminology used in ICT in health care is often used interchangeably and includes: ‘telemedicine’, ‘telehealth’, ‘telehealthcare’, ‘e‐Health’, ‘e‐medicine’, ‘telerehabilitation’ etc. (Currell 2000; McLean 2010; McLean 2011; Winters 2002). In this review we define the term ‘telerehabilitation’ as ‘the use of information and communication technologies as a medium for the provision of rehabilitation services to sites or patients that are at a distance from the provider' (Rogante 2010; Theodoros 2008). The applications to date encompass systems ranging from low‐bandwidth, low‐cost videophones to highly expensive, fully immersive virtual reality systems with haptic interfaces (Theodoros 2008).

Telerehabilitation extends rehabilitative care beyond the hospital process and facilitates multifaceted, often psychotherapeutic approaches to modern management of pwMS at home or in the community (Huijgen 2008). It provides equal access to individuals who are geographically remote and to those who are physically and economically disadvantaged (Hailey 2011; Rogante 2010) and can improve the quality of rehabilitation delivered (Hailey 2011; Kairy 2009; McCue 2010; Rogante 2010; Steel 2011). It can give healthcare providers an opportunity to evaluate the intervention previously prescribed, monitor adverse events and identify areas in need of improvement. The treating therapists can monitor patients’ progress and optimise the timing, intensity and duration of therapy as required, which may not always be possible within the constraints of face‐to‐face treatment protocols in the current health systems (Hailey 2011; Steel 2011).

How the intervention might work

Telerehabilitation is an emerging method of delivering rehabilitation that uses technology to serve patients, clinicians and systems by minimising the barriers of distance, time and cost. The driving force behind this has been the need for an alternative to face‐to‐face intervention, enabling service delivery in the natural environment – that is, in patients’ homes (Hailey 2011). This method of in vivo delivery of healthcare services can address associated issues of efficacy, problems of generalisation and increasing patient participation and satisfaction with treatment.

The benefits and advantages of telerehabilitation have been well documented (Bendixen 2009; Brennan 2009; Chumbler 2012; Constantinescu 2010; Johansson 2011; Kairy 2009; Lai 2004; Legg 2004; Russell 2011; Steel 2011). A home‐based physical telerehabilitation programme was considered feasible and effective in improving function in pwMS (Finkelstein 2008). Telemedicine in pwMS as a tool has the potential for improved health care with reduction in care costs (Zissman 2012). A systematic review that analysed rehabilitation therapies delivered at home in stroke survivors showed positive outcomes, with a reduction in the risk of deterioration, improved ability to perform activities of daily living, reduced costs and duration of rehabilitation in a frail elderly population (Legg 2004). Other reports used telerehabilitation to direct multidisciplinary co‐ordinated, goal‐directed treatment to monitor clinical progress for patients at a distance (Hailey 2011; Kairy 2009; McCue 2010; Rogante 2010; Steel 2011). In these cases, telerehabilitation offered an opportunity to provide an individualised rehabilitation intervention beyond the hospital setting, by regular monitoring and evaluation of the patients' needs and progress, with a range of services suited to the individual and their environment (Hailey 2011; Kairy 2009; McCue 2010; Rogante 2010; Steel 2011). Telerehabilitation also provides health outcomes comparable to traditional in‐person patient encounters, including improved patient satisfaction (Egner 2003; Finkelstein 2008; Hailey 2011; Huijgen 2008; Kairy 2009). It can encompass single or multiple interventions, or both, aimed at improving the patient experience at the level of impairment, activity or participation, and can educate patients (and carers) in their ongoing self management.

Why it is important to do this review

There is strong evidence to support the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes for pwMS (Khan 2007; Khan 2010a). With increasing financial constraints on healthcare systems, alternative methods of service delivery in the community and over a longer term are now a priority. Telerehabilitation was reported to be effective in various neurological conditions including MS (Egner 2003; Finkelstein 2008; Huijgen 2008). However, there is as yet no systematic review of telerehabilitation interventions in pwMS to guide treating clinicians on evidence for its validity, reliability, effectiveness and efficiency in this population.

This review analyses published and unpublished clinical trials relating to MS and telerehabilitation, identifies the evidence base for its use, and discusses issues for future expansion of the evidence base by traditional research and other methods.

Objectives

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of telerehabilitation intervention in persons with multiple sclerosis (pwMS) for improved patient outcomes.

Specifically, the review addresses the following questions:

Does telerehabilitation achieve better outcomes compared with traditional face‐to‐face intervention?

What types of telerehabilitation interventions are effective, in which setting and influence which specific outcomes (impairment, activity limitation and participation)?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs), including quasi‐randomised and quasi‐experimental designs with comparative controls (where the method of allocation is known but is not considered strictly random).

Types of participants

We included studies in pwMS (18 years and over) with a confirmed diagnosis of MS (Mc Donald 2001; Polman 2005; Poser 1983) and all disease subgroups (relapsing remitting, secondary progressive and progressive MS).

Types of interventions

We considered all modalities (type, duration, frequency and intensity) of telerehabilitation intervention, using telecommunication technology as the delivery medium, such as internet, videoconferencing, telephone and virtual reality, aimed at achieving patient‐centred goals or enhancing function and participation. These included: (a) individual (unidisciplinary) treatments, e.g. physical interventions: exercise, self‐management education, etc., and (b) multidisciplinary rehabilitation, i.e. delivered by two or more disciplines: occupational therapy, physiotherapy, exercise physiology, orthotics, other allied health and nursing, in conjunction with medical input.

The settings of telerehabilitation intervention included the following:

outpatient or day treatment settings in community rehabilitation centres;

home‐based settings, in the patients' own homes and local community.

Control conditions included the following:

no treatment;

placebo/sham;

any type of traditional face‐to face rehabilitation treatment in outpatient or day treatment settings.

We excluded studies if they investigated:

acute medical/surgical/pharmacological interventions for pwMS provided via telemedicine technology in isolation, unless it was administered as a concomitant intervention along with the telerehabilitation intervention, which was administered in the same way in both control and treatment groups;

studies on telerehabilitation targeting mental health conditions or substance abuse;

studies on home care (or tele‐home care) with no rehabilitation objectives;

studies on satisfaction with or acceptance of telerehabilitation technology;

studies on technical development or feasibility of telerehabilitation;

studies exploring telerehabilitation technology for intra‐professional communication (such as for second opinions) and for passive information provision, e.g. online education, where there is no direct interaction or involvement of a healthcare professional with the patient.

Types of outcome measures

We identified diverse outcomes, given the varied presentations of MS‐related problems and goals of treatment related to MS severity. The specific outcome measures per se were not part of the exclusion criteria for this review. We report and list all outcome measures used in studies in Table 2.

1. List of outcome measures used in the included studies*.

| Outcome Measures |

| Function |

| Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) |

| Berg Balance Scale (BBS) |

| Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP) |

| Composite Equilibrium Score (CES) |

| Dynamic gait Index (DGI) |

| Exercise Self‐Efficacy Scale (EXCE) |

| Godin Leisure‐Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) |

| Late‐Life Function and Disability Instrument (LL‐FDI) |

| Motor Control Test (MCT) |

| Multidimensional Outcomes Expectations for Exercise Scale (MOEES) |

| Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale – 12 (MSWS‐12) |

| Nine‐Hole Peg Test (NHPT) |

| Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PARQ) |

| Sensory organisation Test (SOT) |

| Six Meter Walk Test (6MWT) |

| Tineti Scale (TS) |

| Timed Up and Go (TUG) |

| Two Meter Walk Test (2MWT) |

| Twenty‐five Foot Walk Test (25‐FWT) |

| Visual Preference Ratio (VPR) |

| Impairment and symptoms |

| Fatigue impact scale (FIS) |

| Fatigue severity scale (FSS) |

| Modified Fatigue impact scale (MFIS) |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) |

| MS related symptom check list |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) |

| Participation |

| Quality of Life |

| Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis (HAQUAMAS) |

| Leeds Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Scale (LMSQOL) |

| Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS‐29) |

| Quality of Well‐ Being Scale (QWB) |

| 36 item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF 36) |

| Psychological |

| Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) |

| Other |

| Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) |

| Energy Conservation Questionnaire (ECQ) |

| Exercise Goal setting Scale (EGS) |

| Muscle strength |

| Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) |

| Self‐Efficacy for Energy Conservation (SEEC) |

| Satisfaction with the intervention |

| Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) |

*Outcome measures are categorised according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF, WHO 2001)

Primary outcomes

We categorised primary outcomes according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO 2001), and included:

improvement in functional activity; such as activities of daily living (ADL), mobility, continence, etc.;

improvement in symptoms or impairments, e.g. pain, spasm frequency, joint range of movement, involuntary movements, spasticity, etc.;

improvement in participation and environmental or personal context, or both; e.g. quality of life (QoL), psychosocial function, employment, education, social and vocational activities, patient and carer mood, relationships, social integration, etc.

We included the measure of achievement of intended goals for treatment, e.g. goal attainment scaling or other measure of goal achievement.

It should be noted, however, that some outcome scales crossed boundaries between these ICF concepts, for example, items relating both to impairment (symptoms) and activity.

Secondary outcomes

These reflect compliance with the intervention, service utilisation, and cost effectiveness of telerehabilitation compared with traditional rehabilitation interventions.

We report all adverse events that may have resulted from the intervention. A serious adverse event is defined 'as an event that is life‐threatening or requires prolonged hospitalisation' (Khan 2007). We also explored carer‐related issues, such as carer strain.

Timing of outcome measures The time points for outcome assessments were: short‐term (immediately after intervention or up to three months) and long‐term (greater than three months) from the start of the intervention. We considered patient follow‐up assessments similarly as short‐term (up to three months) and long‐term follow‐up (greater than three months) after cessation of the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

We considered articles in all languages with a view to translation, if necessary. We extracted trials coded with the specific key words and considered them for inclusion in the review.

Electronic searches

The review authors, along with the Trials Search Co‐ordinator, searched the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the Central Nervous System Group Specialised Register, last searched on 9 July 2014, which contains the following:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014 Issue 7).

MEDLINE (PubMed) (1966 to 9 July 2014).

EMBASE (EMBASE.com) (1974 to 9 July 2014).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCO host) (1981 to 9 July 2014).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database (LILACS) (Bireme) (1982 to 9 July 2014).

Clinical trial registries; clinicaltrials.gov.

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

The keywords used to search for studies for this review are listed in Appendix 1.

Information on the Trial Register of the Review Group and details of search strategies used to identify trials can be found in the 'Specialised Register' section within the Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the Central Nervous System Group module.

Searching other resources

We performed an expanded search to identify articles potentially missed through the database searches and articles from ‘grey literature' from 1996 to latest date. This included the following:

handsearches of reference lists of all retrieved articles, texts and other reviews on the topic;

handsearches of the most relevant journals related to MS and spasticity research and treatment (such as, but not limited to: Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, Journal of Neurology, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, Clinical Rehabilitation, Neurology, Physical Therapy, Multiple Sclerosis, Telemedicine Journal and e‐Health, Journal of Medical Internet Research and others);

searches using the 'Related articles' feature (via PubMed);

searches of ProQuest Dissertations and Theses;

searches of Web of Science for citation of key authors;

searches of System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE);

contacting local and foreign experts for further information, such as MS Groups/Associations, the Cochrane MS Group, key authors of publications in this review;

contacting authors and researchers active in this field.

We also searched the following websites for ongoing and unpublished trials:

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com);

UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database (public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (BA, FK) independently screened and short‐listed all abstracts and titles of studies identified by the search strategy for appropriateness based on the selection criteria. We independently evaluated each study from the shortlist of potentially appropriate studies for inclusion or exclusion. We obtained the full text of the article for further assessment to determine if the trial met the inclusion criteria. If we could not reach a consensus about the inclusion or exclusion of any individual study, we made a final consensual decision by discussion amongst all the review authors. We had intended to submit the full article to the editorial board for arbitration when there was no consensus regarding the inclusion or exclusion of a study between the review authors; however, this was not necessary. We were not masked to the name(s) of the study author(s), institution(s) or publication source at any level of the review.

We had planned to seek further information, where necessary, about the method of randomisation or a complete description of the telerehabilitation interventions from the trialists, but this was not required.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (BA, FK) independently extracted data from each study that met the inclusion criteria, using a standardised data collection form, with other review authors (JK, MG) making a final check. We had intended to contact the primary authors of eligible studies to provide data and clarification where adequate data were not reported, but this was not required. We summarise all studies that met the inclusion criteria in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table provided in Review Manager 5 software developed by Cochrane (Review Manager 2014), and include details on design, participants, interventions and outcomes.

We report the following information from individual studies:

publication details;

study design, study setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, method of allocation, risk of bias;

participant population, e.g. age, type of MS, disease duration, disability (according to Kurtzke's Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score (Kurtzke 1982);

details of intervention;

outcome measures (primary and secondary);

withdrawals, compliance, length and method of follow‐up and number of participants followed up.

We extracted data for every participant assessed for each outcome measure, and for dichotomous data the number in each treatment group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest where possible. We extracted data for intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis from each study, and where ITT data were not available, we retrieved 'on‐treatment’ data or the data of those who completed the trial. We resolved any disagreement by recourse to other review authors (JK, MG) and through discussion, with reference to the original report. We had planned to contact study authors for additional information and data if necessary, but this was not required. We present the results in a tabulated format in the Table 1.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (BA, FK, MG) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011) for sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, therapists and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. Further, we also checked baseline data amongst the study groups for stability.

We considered a study to be of 'high' methodological quality if the risks of bias for all domains were low. We termed this a 'high‐quality study'. We rated a study as being of 'low' methodological quality where there was a lack of clarity or a high risk of bias for one or more domains, and termed this as a 'low‐quality study'. If we rated most domains at high risk of bias, we rated the study as a 'very low‐quality study'. We resolved any disagreements by consensus between the review authors. We present results using 'Risk of bias' summary figures.

Measures of treatment effect

A quantitative analysis was not possible due to clinical heterogeneity (see below), the use of diverse methodology, interventions and outcome measures, and insufficient data available. We entered and analysed all data in Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We qualitatively summarised the studies in the Characteristics of included studies tables, presented the results of primary and secondary outcomes of included studies, categorised according to the ICF framework, in the Table 1. We describe the results in a narrative form in the Discussion section below. If studies had been available, and if meta analyses become feasible in future updates, we will analyse treatment effects as described in the protocol version of this review (Khan 2013).

Unit of analysis issues

For each study, we assessed the appropriate units of analysis, which included the level at which randomisation occurred (e.g. parallel‐group design, cluster‐randomised trials, cross‐over trials, etc.), type, duration, intensity and setting of telerehabilitation interventions.

Dealing with missing data

We provide information about missing data related to participants dropping out or lost to follow‐up in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We contacted the primary authors to obtain additional information and clarification by personal communication (email), to clarify possible overlapping of the data in the four eligible studies. We did not perform imputation of missing data as we were not able to perform meta‐analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining the characteristics of studies, the similarity between the types of participants, settings, interventions (frequency, intensity, duration) and outcomes, as specified in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. Due to apparent clinical heterogeneity, a comprehensive quantitative analysis (meta‐analysis) was not possible. We did not assess statistical heterogeneity and presented the studies separately. We will consider both clinical and statistical heterogeneity, if data become available in future updates, as described in the protocol version of this review (Khan 2013).

Assessment of reporting biases

We used a comprehensive search strategy, which included searching for unpublished studies (grey literature), and searching trials registers (See Search methods for identification of studies) to avoid reporting biases and publication bias (Egger 1998). We did not analyse trial data using funnel plots to investigate the likelihood of publication bias, due to the small number of included studies.

Data synthesis

There was a wide variation in several variables of the included studies, such as MS course and severity, content; frequency, duration, mode of delivery and aim of the interventions; outcome measures used; presentation of results; and methodological quality. Because of the observed heterogeneity, we did not pool data for a quantitative analysis. If studies had been available and if data become available in future updates, we will attempt a quantitative analysis, as described in the protocol version of this review (Khan 2013). We have highlighted the strength of study findings, discussed gaps in the current literature and identified future research directions in the Discussion section.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We were unable to perform subgroup analysis for the following subgroups, owing to the lack of available data:

Type of telerehabilitation intervention (unidisciplinary or multidisciplinary, or both).

Type of MS (relapsing remitting, progressive)

Severity of MS (i.e. EDSS < 6; > 6)

Duration of follow‐up of participants (≤ 3 months; > 3 months)

Sensitivity analysis

We were not able to conduct sensitivity analyses due to our narrative presentation of the results of the included studies. If studies had been available, and heterogeneity existed across trials, we would have conducted sensitivity analyses by omitting trials with a high risk of bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If meta‐analyses become feasible in future updates, we will perform sensitivity analyses as described in the protocol version of this review (Khan 2013).

'Summary of findings' table

These outcomes are included in the Table 1:

Change in disability (post‐intervention, ≤ 3 months, > 3 months)

Change in impairments (post‐intervention, ≤ 3 months, > 3 months)

Change in participation (psychological outcomes, QoL)

Cost effectiveness

Process evaluation

Serious adverse events

Caregivers'‐related outcomes

We used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contribute data to the meta‐analyses for prespecified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008). We justified all decisions to downgrade or upgrade the quality of studies by using footnotes, and we made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review when necessary.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

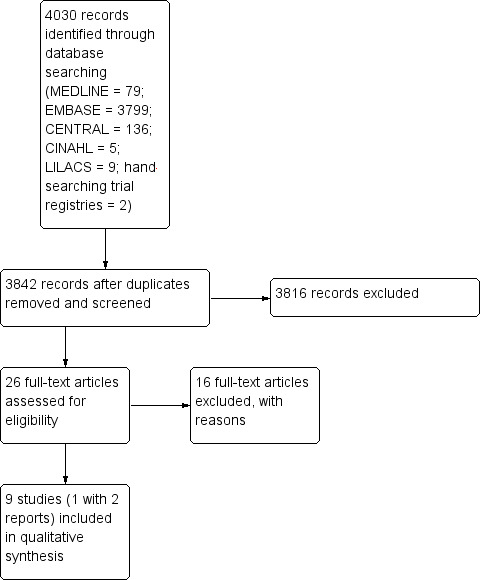

Electronic and manual searches identified 4030 references (MEDLINE = 79; EMBASE = 3799; CENTRAL = 136; CINAHL = 5; LILACS = 9; CRD database = 0; Cochrane Opportunity Fund Project = 0; Trial Registries via WHO Portal = 0; handsearching journals = 0; handsearching trial registries = 2) with our search criteria. After elimination of duplicates records, we screened the remaining 3842 for closer scrutiny. Of these, we retrieved the full text of 29 articles for further assessment to determine inclusion in the review. We did not identify any ongoing or unpublished studies awaiting classification. See: Figure 1 for Study flow chart.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

In total, nine RCTs, one with two reports (Pilutti 2014; Sandroff 2014), published between 2003 and 2014 (Dlugonski 2012; Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011; Frevel 2014; Gutíerrez 2013a; Huijgen 2008; Motl 2011; Paul 2014; Pilutti 2014) fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Five of the included studies were conducted in the United States (Dlugonski 2012; Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011; Motl 2011; Pilutti 2014); one each was conducted in Spain (Gutíerrez 2013a), Germany (Frevel 2014) and the United Kingdom (Paul 2014), while one was a multicentre study conducted in three different countries (Italy, Spain and Belgium; Huijgen 2008). Three studies were conducted by the same group of authors in the same setting and with the same cohort of participants recruited from a single database (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011; Pilutti 2014), of which one reported different outcomes in two different articles (Pilutti 2014).

Participants

Participants' detailed information, including inclusion/exclusion criteria and baseline demographics, are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. The nine included studies involved a total of 531 participants (277 participants in the treatment groups and 254 in the control groups). The number of participants in the studies ranged from 27 to 190 (median 45). As expected, there were more women, with their proportion ranging from 56% to 87% (mean 74%). The mean age of participants varied from 41 to 52 years (mean 46.5 years) and mean years since diagnosis from 7.7 to 19.0 years (mean 12.3 years). The majority of participants had a relapsing‐remitting course of MS (RRMS), two studies involved only people with RRMS (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011) and two studies did not provide details of MS type (Egner 2003; Huijgen 2008). The study inclusion criteria varied between trials. All trials included participants with definite MS, although only two trials specified the commonly‐used McDonald's criteria (Mc Donald 2001) (Frevel 2014; Gutíerrez 2013a). One study reported secondary data regarding MS participants which were collected as part of a larger study of a telerehabilitation intervention in people with severe mobility impairment (Egner 2003).

Intervention

Detailed information about interventions in the included studies is presented in the Characteristics of included studies tables and is further summarised in Table 3. The various telerehabilitation interventions in the included studies consisted generally of physical activity and educational components.

2. Summary of telerehabilitation interventions in the included studies.

| Study | Telerehabilitation interventions | |||

| Contents | Settings | Technology | Duration/intensity | |

| Dlugonski 2012 | Same as Motl 2011 ( see below) | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | 12 weeks Same as Motl 2011 ( see below) |

| Egner 2003 | Structured in‐home education and counselling session delivered by a rehabilitation nurse, which included individual rehabilitation education sessions | Participants' home | Telephone or video | 30 to 40 minutes, weekly for 5 weeks, then once every 2 weeks for 1 month. |

| Finlayson 2011 | Group‐based fatigue management programme, facilitated by a licensed Occupational Therapist | Rehab centre | Teleconference | 70‐minute weekly for 6 weeks |

| Frevel 2014 | Training programme: balance, postural control exercises and strength training with additional interactive sessions | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | 2 training sessions/(45 minutes) weekly for 12 weeks |

| Gutíerrez 2013a | Monitored telerehabilitation programme, which included gaming protocol, proposing activities that involve integrating proprioceptive, visual, and vestibular sensory information. Experimental group attended at home | Participants' home | Virtual reality system via video‐conference using the Xbox 360 and Kinect console | 40 sessions, 4 sessions per week (20 minutes per session) |

| Huijgen 2008 | Home Care Activity Desk (HCAD) – a telerehabilitation intervention for arm/hand function and additional features for videoconferencing and recording. HCAD system | Participants' home | Virtual telerehabilitation programme and video‐conference, comprising a hospital‐based server and portable unit installed at participant’s home | 1 month of usual care followed by HCAD‐ 1 session (30 minutes)/day for 5 days per week for 1 month |

| Motl 2011 | Same as Dlugonski 2012 (see above) | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | Same as Dlugonski 2012 (see above) |

| Paul 2014 | Individualised physiotherapy programme consisting of exercise page containing a video and text explaining the exercise, an audio description of the exercise and a timer | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | Twice per week for 12 weeks |

| Pilutti 2014 | Same as in Motl 2011 (see above), in addition, participant wore a Yamax SW‐401 Digiwalker pedometer, completed a log book and used Goal Tracker software, and received a web‐cam, and website information | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | 15 scheduled one‐on‐one video coaching sessions for 6 months |

| Sandroff 2014 | Same as in Motl 2011, Pilutti 2014 (see above). In addition, website materials were delivered in a titrated manner over the 6‐month period such that new content became available 7 times during the first 2‐month period, 4 times during the second 2‐month period, and twice during the final 2 months of the intervention. | Participants' home | Internet‐delivered | Weekly one‐on‐one behavioural coaching sessions via Skype (15 scheduled sessions) for 6 months |

Three studies used similar internet‐delivered, social cognitive theory‐based behavioural intervention to increase physical activity (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011; Pilutti 2014)

One study evaluated a structured in‐home education and counselling session delivered via telephone or video by a rehabilitation nurse (Egner 2003)

One study examined a group‐based, teleconference‐delivered fatigue management programme (Finlayson 2011)

One study evaluated a telerehabilitation intervention for arm/hand function at home ‐ the 'Home Care Activity Desk' (HCAD), which consists of a set of exercises for functional activity of the upper limb (Huijgen 2008)

One study evaluated the effectiveness of an individualised web‐based physiotherapy programme (Paul 2014)

One study published in two different journals by the same authors (Gutíerrez 2013a; Gutierrez 2013b) examined the effectiveness of an individualised virtual reality telerehabilitation programme for improvement in postural control

One study examined the effectiveness of an internet‐based home training programme (e‐Training) in comparison with hippotherapy to improve balance (Frevel 2014)

The duration and intensity of the telerehabilitation interventions varied significantly depending on the nature of the intervention, and ranged from one to six months (median 12 weeks). None of the studies reported the recruitment time period. The follow‐up periods varied between trials, but all studies assessed the participants immediately after intervention. Only one trial reported long‐term follow‐up of up to 24 months (Egner 2003). For details of assessment time points for each trial refer to the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 studies after appraisals of the full reports (listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables). The primary reason for exclusion was:

10 studies addressed mental health care as a primary intervention (Amato 2014; Beckner 2010; Cerasa 2013; Fischer 2013; Mohr 2000; Mohr 2005; Mohr 2007; Moss‐Morris 2012; Solari 2004; Stuifbergen 2012)

One study had a medical‐care intervention only (Zissman 2012)

One study evaluated the effectiveness of an online fatigue self‐management programme for people with various chronic neurological conditions including MS, but did not provide a subgroup analysis for the MS cohort (Ghahari 2010)

Two studies assessed counselling interventions for health promotion and major depression (Bombardier 2008; Bombardier 2013)

Two studies assessed interventions with no rehabilitation objectives, such as education, self management (Miller 2011; Wiles 2003)

Risk of bias in included studies

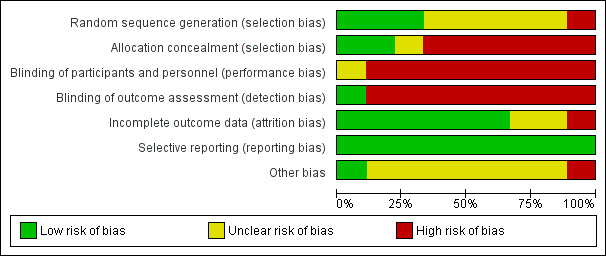

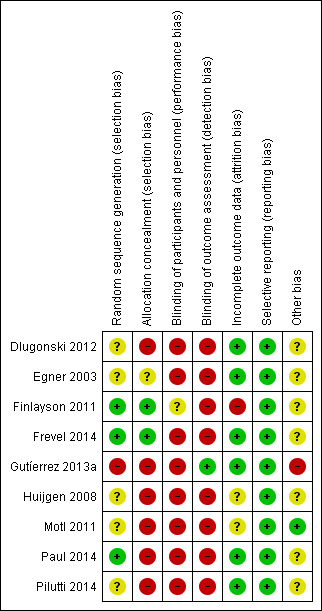

See: ’Risk of bias’ tables in the Characteristics of included studies and Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 represent the review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item, presented as percentages across all included studies and a summary of the risk of bias, respectively. Where studies failed to report sufficient methodological detail to assess the potential risk of bias, we graded them as being at 'unclear’ risk (presented as symbol '?' in Figure 3). The methodological quality of the nine included trials was 'low’, with substantial flaws in the methodological design and a high risk of bias related to their randomisation procedure; blinding of participants, therapists and outcome assessors, and outcome analysis.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Although all included studies stated that the procedure was randomised, the methods of randomisation were adequately reported in only six studies (one with two reports) (Dlugonski 2012; Finlayson 2011; Frevel 2014; Motl 2011; Paul 2014; Pilutti 2014).

Two studies used a random number generator for randomisation (Dlugonski 2012; Pilutti 2014)

One study used a random permutated block design (Finlayson 2011)

One randomly allocated the participants using simple allocation by drawing lots of preshuffled opaque envelopes (Frevel 2014)

One study used a series of random numbers generated in Microsoft Excel (consecutive numbers allocated, where even numbers represented the intervention group and odd numbers the control group) (Paul 2014)

Only three studies described in detail concealment of allocation prior to entry to the study (Finlayson 2011; Frevel 2014; Motl 2011). Other studies either gave little or no information about the randomisation procedure, or used non‐random components like alternation, assignment to comparable groups with respect to clinical and demographic factors, or allocation of participants to the intervention group after initial randomisation.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and treating personnel can be challenging in rehabilitation trials, because of the characteristics of interventions. However, blinding of outcome assessors is possible and highly desirable (Amatya 2013). The blinding of participants and personnel was insufficiently reported in most of the studies. Only one study took measures to blind participants to group allocation (Finlayson 2011). None of the studies attempted to blind the treating personnel. One study mentioned blinding of the outcome assessors, but provided no details (Gutíerrez 2013a).

Incomplete outcome data

The drop‐out rate of participants during the trial period ranged from 0% to 21%. In four studies, there were no or minimal losses to follow‐up (Dlugonski 2012; Egner 2003; Gutíerrez 2013a; Paul 2014). Drop‐outs and withdrawals were higher than 20% in only one study (Finlayson 2011), which recruited the highest number of participants. One study which included MS participants as one of the subgroups failed to report the attrition rate (Huijgen 2008). Most of the studies did not conduct intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Selective reporting

All the included studies reported prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes (see Table 2 and Table 4 for a list of the outcome measures).

3. Summary of outcome assessed in the included studies.

|

Study |

Outcome assessed* | |||

| Function | Impairment | Participation | Others | |

| Dlugonski 2012 | GLTEQ, MSWS‐12 | MSIS‐29 | PDDS, SATISFACTION | |

| Egner 2003 | FSS | QWB, CES‐D | ||

| Finlayson 2011 | FIS, FSS | SF‐36 | ECQ, PDDS | |

| Frevel 2014 | BBS, DGI, TUG, 2MWT | MFIS | HAQUAMAS | Muscle strength |

| Gutíerrez 2013a | SOT, MCT, BBS, TS | |||

| Huijgen 2008 | ARAT, NHPT | VAS satisfaction survey | ||

| Motl 2011 | GLTEQ, LL‐FDI, EXCE, MOEES | EGS, PDSS | ||

| Paul 2014 | 25 FWT, BBS, TUG | MS related symptom check list | MSIS, LMSQOL, HADS | |

| Pilutti 2014 | GLTEQ | MFIS, FSS, MPQ, PSQI | MSIS‐29, HADS | PDDS |

| Sandroff 2014 | 6MWT, IPAQ | SDMT | PDDS | |

*Categorised according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF, WHO 2001)

ARAT: Action Research Arm Test; BBS: Berg Balance Scale;CDP: Computerized Dynamic Posturography; CES: Composite Equilibrium Score; CES‐D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DGI: Dynamic gait Index;ECQ: Energy Conservation Questionnaire; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; EGS: Exercise Goal setting Scale;EXSE: Exercise Self‐Efficacy Scale; FIS: Fatigue Impact Scale; FSS: Fatigue Severity Score; GLTEQ: Godin Leisure‐Time Exercise Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAQUAMS: Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis; IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire; LMSQOLS: Leeds Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Scale;LL‐FDI: Late‐Life Function and Disability Instrument; MCT: Motor Control Test; MOEES: Multidimensional Outcomes Expectations for Exercise Scale; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; MSIS‐29: Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale; MSWS‐12: Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale–12; NHPT: Nine Hole Peg Test; PARQ: Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire; PDDS: Patient Determined Disease Steps; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; QWB: Quality of Well‐ Being Scale; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SF‐36: 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey; SOT: Sensory organisation Test; TS: Tineti Scale; TUG: Timed Up and Go;VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; 6MWT: 6 minute walk test; 25FWT: 25 Foot Walk Test

Other potential sources of bias

Sample sizes were small (< 40 participants) in four studies (Egner 2003; Frevel 2014; Huijgen 2008; Paul 2014). A series of three studies was conducted by the same group of authors, which recruited selective participants who volunteered for research through a single database for the same institutions (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011; Pilutti 2014). Although none of these studies mentioned overlapping of the recruited participants, we cannot rule out the possibility of inclusion of the same participants in different trials. Furthermore, this series of studies published one trial (Pilutti 2014) with different outcomes in another report (Sandroff 2014). Most included studies had short‐term follow‐up, and were restricted to immediate post‐treatment assessments. Most studies seemed to be underpowered and only one study performed a sample size calculation (Finlayson 2011). One study (Egner 2003 ) failed to report the participant recruitment process and methodology in detail, and allocation of participants to treatment and control groups was unbalanced in two studies (Egner 2003; Huijgen 2008).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Meta‐analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the included studies mentioned earlier. The included studies used a range of telerehabilitation approaches in pwMS (see Table 3 for the summary of telerehabilitation interventions) and a broad range of outcome measures (see Table 4 for a list of outcome measure used). A summary of the findings of the included trials is presented based on primary and secondary outcomes categorised according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework in the Table 1. Pooling of data from the included studies was confounded by the differences between interventions and the use of different outcome measures, as highlighted above.

Primary outcomes

Improvement in functional activity

All studies except two (Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011) assessed the first prespecified primary endpoint to improve functional activity in pwMS (N = 314 participants,low quality evidence). All studies evaluated participants immediately after the intervention, using different instruments (see Table 4 and Table 1), with intervention periods ranging from one to six months. Overall six studies assessed the functional endpoint post‐intervention up to 12 weeks (Dlugonski 2012; Frevel 2014; Gutíerrez 2013a; Huijgen 2008; Motl 2011; Paul 2014).

Two studies (Dlugonski 2012; Motl 2011) conducted in different time periods with the same cohort of participants showed significant improvement in physical activity in the treatment group at the post‐intervention assessment, as measured by the Godin Leisure‐Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) (P < 0.01). The authors' reported increase in physical activity was sustained at three‐month follow‐up compared with the control group (P < 0.001) (Motl 2011).

One study (Frevel 2014) comparing two interventions, e‐training and hippotherapy, showed significant improvement in dynamic and static balance capacity compared with baseline values in both the intervention (e‐training) (Dynamic Gait Index (DGI): P = 0.016, Berg Balance Scale (BBS): P = 0.011) and control (hippotherapy) groups (DGI: P = 0.011, BBS: P = 0.011). However, there was no difference between groups.

Huijgen 2008 showed no statistically significant differences between the intervention using telerehabilitation for arm functions (Home Care Activity Desk (HCAD)) and control groups in arm function as measured by Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) (mean change 1.26, 90% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.90 to 4.42) and Nine‐Hole Peg Test (NHPT) (mean change 7.24, 90% CI ‐6.55 to 23.25).

Paul 2014 reported an increase in gait speed using the 25 Foot Walk Test (25FWT) in the intervention group compared with the control group, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.170). The intervention group had a statistically significant improvement in the physical subscale of the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS) (P = 0.048).

Another study (Gutíerrez 2013a) showed improvements in balance and postural control, with a significant increase in Composite Equilibrium Score (CES) in the intervention group (mean change 8.21 points, P < 0.001), but not in the control group (mean change 1.93, P = 0.123). Visual Preference Ratio and contribution of vestibular information (VEST, Vestibular Ratio) improved significantly in the intervention group (P < 0.001), but not in the control group (P > 0.05). There were significant post‐treatment differences between treatment and control groups in the CES (F = 37.873, P < 0.001) and the VEST (F = 12.156, P < 0.001). Significant post‐treatment differences between groups were also found for the ability to accept incorrect visual information expressed by the visual conflict parameter (F = 15.05, P < 0.000), which demonstrates that the treatment group showed a greater ability to accept post‐treatment afferent inputs compared with the control groups. There were no significant between‐group differences in the contribution of the visual system (F = 2.64, P = 0.11) or use of somatosensory information (F = 0.117, P = 0.734) in the maintenance of balance and stability.

One study (Sandroff 2014) evaluating an internet‐delivered behavioural intervention, showed a significant positive effect of the intervention on the Six Minute Walk (6MW) test relative to the control group (P = 0.07). The authors also found physical activity increased most in those with mild disability.

Improvement in impairments

Five studies assessed the prespecified primary endpoint (improvement in impairments) using different measures (N = 347 participants;low quality evidence) (Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011; Frevel 2014; Paul 2014; Pilutti 2014).

Fatigue was the primary outcome in three studies (Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011; Pilutti 2014), all reporting significant differences between groups in favour of the intervention group. One study (Finlayson 2011) showed a significant reduction in fatigue in the intervention group immediately after intervention compared to a wait‐list control group as measured by the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) in all three subscales: mean difference (SD): Cognitive ‐3.12 (6.1), P = 0.001; Physical ‐2.53 (6.4), P = 0.014; Social ‐6.01 (12.1), P = 0.002. These changes were maintained with large effect sizes in all FIS subscales at three‐month follow‐up: Effect Size (95% CI): Cognitive 0.58 (0.48 to 0.68); Physical 0.68 (0.55 to 0.82); Social 0.65 (0.53 to 0.77), and at six‐month follow‐up: Cognition: 0.55 (0.46 to 0.64); Physical: 0.61 (0.5 to 0.72) and Social: (0.67 (0.58 to 0.76). There was also a significant reduction in the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) scores at all three time periods.

Egner 2003 analysed the impact of a telerehabilitation intervention (structured in‐home counselling and education) delivered via telephone or video, and reported similar fatigue scores (measured using FSS) for all three groups (video, telephone and standard care) at nine weeks post‐intervention; however, the participants in the video group had significantly lower scores than the other two groups at six months (P < 0.05) and at 18 months (P < 0.05).

One study (Pilutti 2014) showed a significant positive effect of the behavioural intervention on fatigue severity (FSS, P = 0.001) and its physical impact (FIS, P = 0.008) at six‐month post‐intervention. There was a favourable effect of the intervention on symptoms of pain (McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), P = 0.08) and sleep quality post‐trial (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), P = 0.06), although the differences between groups did not reach statistical significance.

Frevel 2014 reported significant improvement in fatigue in the control group (hippotherapy) (P < 0.05) for all subscales of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), while the intervention group (e‐training) improved only on the MFIS cognitive subscale (P = 0.031). A significant difference between the groups was noted only in the cognitive subscale of the MFIS ( P = 0.012).

One study (Paul 2014) reported no improvements in symptoms as measured by the MS Symptom Checklist.

Improvement in participation

Psychological outcomes

Overall three studies (one with two reports), assessed cognitive functions as one of the outcomes (N = 139 participants, low quality evidence) (Egner 2003; Paul 2014; Pilutti 2014).

Egner 2003 showed that a telerehabilitation intervention (structured in‐home counselling and education) delivered via telephone or video, improved depressive symptoms as measured by the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) at the end of the intervention period (nine weeks) in both groups. Mean CES‐D scores fluctuated, but decreased at 24 months in all three groups. This was, however, not statistically significant. Mean depression scores were lower in those receiving telerehabilitation by video compared with telephone and standard‐care groups, and depressive symptoms also decreased at the six‐, eight‐ and 24‐months follow‐ups, but this was not significantly different between groups. The authors reported that being male was a significant predictor for increased depression score at every measurement point except at 24 months (P < 0.05) (Egner 2003).

Paul 2014 reported a small non‐significant improvement in anxiety measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the control group compared to the treatment group post‐treatment (eight to nine weeks) (P = 0.016).

One study with two reports (Pilutti 2014) showed a statistically significant group interaction in psychological outcomes on Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) scores (F = 5.68, P = 0.02), which was moderate in magnitude (partial eta squared (ɳ₂) = 0.08). There was a clinically meaningful improvement in SDMT scores in the subgroup with mild disability in the intervention condition (∼ 6 points increase, moderate effect size (d) = 0.41), whereas those with moderate disability in the intervention condition demonstrated minimal change (∼ 1 point decrease, d = 0.12). There were minimal changes in SDMT scores for those with mild or moderate disability (∼ 1 point increase, d = 0.10 for both) in the control group. There was also significant improvement in depression and anxiety in the intervention group (with large effect size (ɳ₂ = 0.10 for both) compared with the control group measured by the HADS (depression: F =7.90, P = 0.006; anxiety: F = 8.00, P = 0.006) (Pilutti 2014).

Quality of life

Six studies assessed quality of life (QoL), using different outcome measures (N = 392 participants;low quality evidence) (Dlugonski 2012; Egner 2003; Finlayson 2011; Frevel 2014; Paul 2014; Pilutti 2014).

Egner 2003 reported no significant difference in QoL between the treatment groups (video or telephone) and control group (standard care) measured using the Quality of Well‐Being Scale (QWB) at the end of the intervention period (nine weeks). However, mean QWB scores for each measurement point (6‐, 9‐, 12‐, 18‐ and 24‐months) were higher (indicating higher QoL) for participants in the video group than for those in the standard care and telephone groups. There were significantly higher QWB scores in the video compared with the telephone groups at 12 months follow‐up only (P < 0.05; standard error (SE) = 0.023). The telephone group and standard‐care groups reported similar mean QWB scores over the two‐year follow‐up period (Egner 2003).

One study (Frevel 2014) showed significant improvement in QoL measured by the Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis (HAQUAMS) (in subscales ‐ Cognition: P = 0.026; Function of lower limb: P = 0.008; Mood: P = 0.045) in the control group (hippotherapy), but not in the intervention group (e‐training).