Abstract

Since its recognition in December 2019, covid-19 has rapidly spread globally causing a pandemic. Pre-existing comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are associated with a greater severity and higher fatality rate of covid-19. Furthermore, COVID-19 contributes to cardiovascular complications, including acute myocardial injury as a result of acute coronary syndrome, myocarditis, stress-cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, and cardiac arrest. The cardiovascular interactions of COVID-19 have similarities to that of severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome and influenza. Specific cardiovascular considerations are also necessary in supportive treatment with anticoagulation, the continued use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, arrhythmia monitoring, immunosuppression or modulation, and mechanical circulatory support.

Keywords: systemic inflammatory diseases, cardiac risk factors and prevention, myocarditis

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes covid-19, was first reported to WHO as a pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China, on 31 December 2019.1 While the initial outbreak was mostly confined to the epicentre in China, SARS-CoV-2 quickly spreads internationally causing a global pandemic. By 15 March, the number of cases outside of China surpassed those in China, and as of 12 April 2020, over 1.8 million cases and 110 000 deaths were reported worldwide, affecting 185 countries.2

The most common symptoms of COVID-19 include fever, dry cough, myalgia or fatigue, as is the case in many other viral infections.3 4 According to a study by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention of 44 672 laboratory confirmed, 10 567 clinically diagnosed and 16 186 suspected cases of COVID-19, 81.4% exhibited mild illness (with no or mild symptoms of pneumonia), 13.9% had severe symptoms (dyspnoea with respiratory rate ≥30/min, SpO2 ≤93%, PaO2/FiO2<300 and/or infiltration of lung field >50% within 24–48 hours), and 4.7% were critically ill (respiratory failure, septic shock and/or multiorgan failure).5 In patients with severe or critical disease, viral pneumonia can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multisystem failure accompanied by a cytokine storm.5

Since patients with covid-19 with cardiovascular comorbidities have higher mortality,5 and the severity of COVID-19 disease correlates with cardiovascular manifestations,6 it is important to understand the interaction of COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease (CVD). This review will summarise our current understanding of the cardiovascular manifestations of covid-19, as compared with SARS (caused by SARS-CoV), the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) (caused by MERS-CoV) and influenza. We will also discuss cardiovascular considerations regarding treatment strategies.

Cardiovascular comorbidities

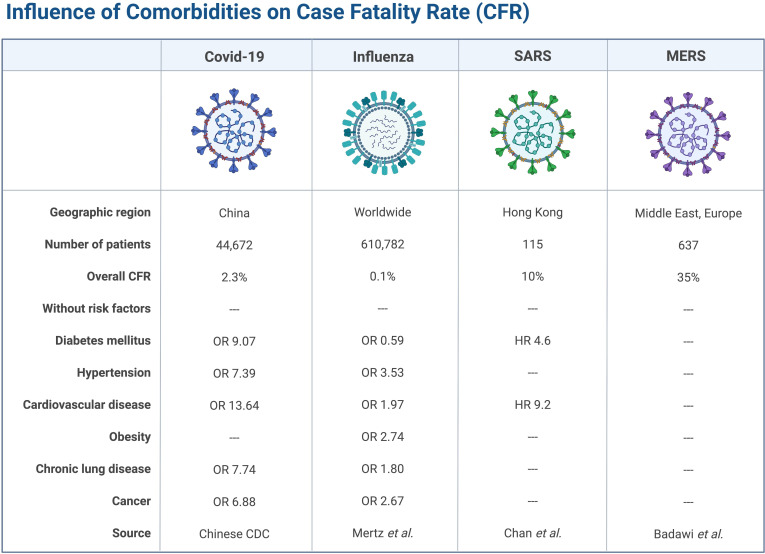

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity in patients with COVID-19 in the USA appear to be higher than in the general population, but the prevalence of CVD appears to be similar (table 1). However, in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 with more severe disease, DM, hypertension and CVD seem to be more prevalent in both the USA and China, similar to MERS and influenza (table 2). A retrospective, single-centre case series of 187 patients with COVID-19 found that patients with underlying CVD were more likely to have cardiac injury (troponin (Tn) elevation) compared with patients without CVD (54.5% vs 13.2%).6 In-hospital mortality was 7.6% for patients without underlying CVD and normal Tn, 13.3% for those with CVD and normal Tn, 37.5% for those without CVD but elevated Tn and 69.4% for those with CVD and elevated Tn.6 These observations suggest that although patients with pre-existing CVD may not be more susceptible to contracting SARS-CoV-2, they are prone to more severe complications of COVID-19 with increased mortality.7 The association of cardiovascular and other comorbidities with case fatality rate is summarised in figure 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of cardiopulmonary comorbidities in covid-19 disease in the USA and China compared with the general population

| Geographic region | COVID-19 | General population | ||

| USA | China | USA (>20 years of age) |

China (>15 years of age) |

|

| Total number | 7162 | 44 672 | 265 million | Various |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10.9% | 5.3% | 9.8% | 10.9% |

| Hypertension | --- | 12.8% | 45.6% | 23.2% |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9.0% | 4.2% | 9.0% | 3.7%* |

| Obesity | 48.3% | --- | 31.2% | 11.9% |

| Chronic lung disease | 9.2% | 2.4% | 5.9%† | 8.6% |

| Source (reference) | CDC74 | Chinese CDC5 |

AHA75

Croft et al 76 |

Hu et al 77 |

*Combination of cerebrovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

†Chronic obstructive lung disease only.

AHA, American Heart Association; CDC, Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Table 2.

Prevalence of comorbidities in hospitalised patients with severe respiratory viral infections

| Geographic region | COVID-19 | Influenza | SARS | MERS | ||

| USA | China | Italy* | USA | Canada | Middle East, Europe | |

| Total number | 178 | 416 | 1043 | 3271 | 144 | 637 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28.3% | 14% | 17.3% | --- | 11% | 51% |

| Hypertension | 49.7% | 30.5% | 48.8% | --- | --- | 49% |

| Cardiovascular disease | 27.8% | 14.7% | 21.4% | 45.6% | 8% | 31% |

| Obesity | 48.3% | --- | --- | 39.3% | --- | --- |

| Chronic lung disease | 34.6% | 2.9% | 4.0% | 34.5% | 1% | |

| Malignancy or immunocompromised | 9.6% | 2.2% | 7.8% | 17.0% | 6% | |

| Source (reference) | CDC COVID-Net, Garg et al 78 | Shi et al 7 | Grasselli et al 79 | CDC FluServ-Net80 | Booth et al 81 | Badawi and Ryoo73 |

*Only including patients in the intensive care unit.

CDC, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Figure 1.

Influence of cardiovascular and other comorbidities on CFR from respiratory viral infections. CDC, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; CFR, case fatality rate; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome. Data are from Chinese CDC,5 Mertz et al,71 Chan et al 72 and Badawi et al. 73

The higher mortality in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities may be directly attributable to underlying CVD or merely coincident with CVD. CVD may also be a marker of accelerated ageing, immune system dysregulation, or other mechanisms that affect COVID-19 prognosis. Age is both a risk factor for CVD and an important determinant of COVID-19 fatality, which has been found to be 14.8% in patients older than 80 years of age but <4% in patients younger than 70 years of age.5 Patients with elevated Tn levels were older than patients with normal Tn (71.4±9.4 vs 53.5±13.2 years).6 In addition, ageing weakens the immune system, as demonstrated by the lower protective titres after influenza vaccination in 50% of adults older than 65 years of age.8

Pathophysiology of cardiac injury

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus.9 SARS-CoV-2 and other similar coronaviruses use the ACE 2 (ACE2) protein for ligand binding before entering the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis.10 Recent data on viral structure reveal that SARS-CoV-2 has tighter interaction with the human ACE2 receptor binding domain as compared with SARS-CoV, which may explain in part the greater transmissibility of the current virus among humans.11 ACE2 is a membrane protein that serves many physiological functions in the lungs, heart, kidneys and other organs.12 It is highly expressed in type 2 lung alveolar cells, which provides an explanation for the respiratory symptoms experienced by patients with COVID-19.13 More than 7.5% of myocardial cells have positive ACE2 expression, based on single-cell RNA sequencing,14 which could mediate SARS-CoV-2 entry into cardiomyocytes and cause direct cardiotoxicity.

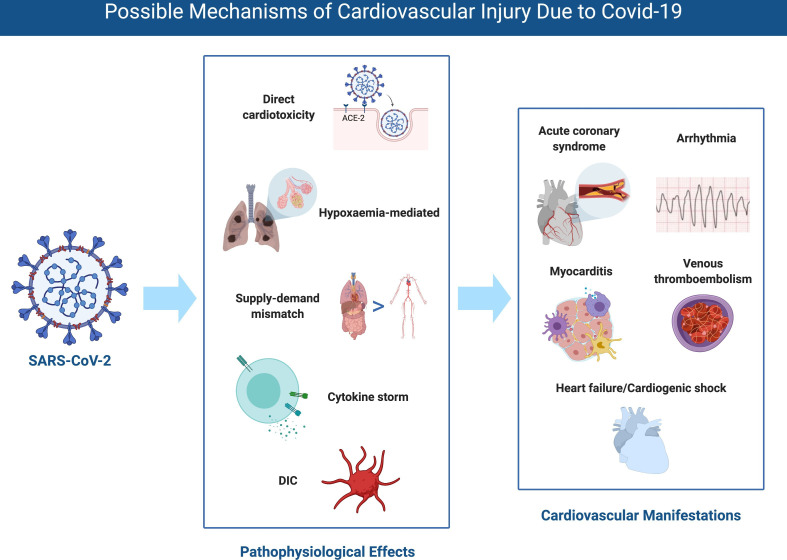

The mechanisms of cardiovascular injury from COVID-19 have not been fully elucidated and are likely multifactorial. SARS-CoV-2 viral particles have been identified by RT-PCR in cardiac tissue in some cases,15 supporting that direct cardiotoxicity may occur. Virally driven hyperinflammation with cytokine release may lead to vascular inflammation, plaque instability, myocardial inflammation, a hypercoagulable state, and direct myocardial suppression.16 17 Other systemic consequences of COVID-19 infection, including sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), may also mediate cardiac injury. Based on postmortem biopsies, the pathological features of covid-19 in multiple organs greatly resemble those seen in SARS18 19 and MERS.20 21 In cardiac tissue, pathological findings vary from minimal change to interstitial inflammatory infiltration and myocyte necrosis (table 3). In the vasculature, microthrombosis and vascular inflammation could be found (table 3).

Table 3.

Pathological findings of the cardiopulmonary systems in death related to coronaviruses

| Study | Region | Disease | Age/Sex | Lung | Heart | Vasculature |

| Yao et al 15 | China | Covid-19 | 63/M, 69/M, 79/F |

Alveolar exudates, interstitial inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis, hyaline membrane formation. Positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2, positive viral inclusions. |

Myocardial hypertrophy and multifocal necrosis, interstitial inflammatory infiltration. No viral inclusions; negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2. |

Diffused hyaline thrombosis in microcirculation in multiple organs. |

| Xu et al 82 | China | COVID-19 | 50/M | Bilateral diffuse alveolar damage with cellular fibromyxoid exudates, desquamation of pneumocytes and hyaline membrane formation, pulmonary oedema, interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltration. | A few interstitial inflammatory infiltrations. | NA |

| Tian et al 83 | China | COVID-19 | 78/F, 74/M, 81/M, 59/M |

Diffused alveolar damage, hyaline membrane formation and vascular congestion, inflammatory cellular infiltration, focal interstitial thickening (case 3), large area of intra-alveolar haemorrhage and intra-alveolar fibrin cluster formation (case 4). Positive RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 in 1/3 patients. |

Various degrees of focal oedema, interstitial fibrosis and myocardial hypertrophy; no inflammatory infiltration. Positive RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 in 1/2 patients (both patients with elevated troponin). | Fibrinoid necrosis of the small vessels of lung (case 4). |

| Fox et al 84 | USA | COVID-19 | Four patients, range: 44–76 years |

Pleural effusion, bilateral pulmonary oedema, patches of haemorrhage, diffuse alveolar damage, lymphocytic infiltration, hyaline membrane and fibrin. Viral inclusion. | Pericardial effusion, cardiomegaly with RV dilatation, scattered individual myocyte necrosis. | Thrombi and lymphocytic infiltration of small vessels of lung. |

| Lang et al 85 | China | SARS | 73/M, 64/F, 69/F |

Oedema and homogeneous fibrinous deposition of alveolar walls, desquamation of pneumocyte; exudate in alveolar space, hyaline membrane formation; inflammatory infiltration. Positive RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-1 in all three patients. |

Atrophy of cardiac muscle, lipofuscin deposition in cytoplasm, proliferation of interstitial cells and lymphocytes. | Fibrous thrombi in pulmonary vessels. |

| Ding et al 18 | China | SARS | 62/F, 25/M, 57/M |

Extensive consolidation, pulmonary oedema, haemorrhagic infarction, desquamative alveolitis and bronchitis, exudation, hyaline membrane formation, focal necrosis. Viral inclusion. | Myocardial stromal oedema, inflammatory infiltration, hyaline degeneration and lysis of cardiac muscle. | Diffused inflammatory infiltration of vessel walls, edematous endothelial cells, fibrinoid necrosis of veins in multiple organs, mixed thrombi in small veins and hyaline thrombi in microvessels. |

| Farcas et al 19 | Canada | SARS | 21 patients | Diffuse alveolar damage. Positive RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-1 in 9/13 patients. |

Positive RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-1 in 7/18 patients. | NA |

| Ng et al 21 | UAE | MERS | 45/M | Diffuse alveolar damage with denuding of bronchiolar epithelium, prominent hyaline membranes, alveolar fibrin deposits. | Diffuse myocyte hypertrophy, patchy fibrosis. | NA |

| Alsaad et al 20 | Saudi Arabia | MERS | 33/M | Hyaline membrane formation, diffuse alveolar damage, parenchymal necrosis. Viral inclusion. | No significant inflammatory infiltration. | Subendothelial inflammatory infiltration of interstitial arteries of the lung. |

MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; NA, not available; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Cardiovascular manifestations

The clinical cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 include elevation of cardiac biomarkers (ischaemic or non-ischaemic aetiology), cardiac arrhythmia, arterial and venous thromboembolism (VTE), and cardiogenic shock and arrest. The possible mechanisms and cardiovascular manifestations are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Possible mechanisms of cardiovascular injury due to COVID-19. DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Elevation of cardiac biomarkers

Myocardial injury is common among patients with COVID-19 infection and correlates with disease severity. Although somewhat variable, studies on patients with COVID-19 have generally defined myocardial injury as the elevation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) above the 99th percentile of its upper limit of normal or evidence of new electrocardiographic or echocardiographic abnormalities.3 22 Increased levels of hs-cTn correlate with disease severity and mortality rate in COVID-19, even after controlling for other comorbidities.23 A summary of studies with prevalence of myocardial injury and risk of severe disease or mortality is shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Studies on troponin elevation and risk of severe disease or death in COVID-19

| Study | Region | Dates of study | Number | Age* | Male (%) | Tn elevation (%) | Arrhythmia (%) | Death (%) | OR of death or severe disease‡ with Tn elevation |

| Huang et al 3 | China | 16 December 2019–2 January 2020 | 41 (with 17.1% censored) | 49 [41–58] | 73.2 | 12.2 | --- | 14.6 | 12.0 [1.2 - 121.8]‡ |

| Zhou et al 22 | China | 29 December 2020–31 January 2020 | 191 | 56 [46–67] | 62.3 | 16.6 | --- | 28.3 | 80.1 [10.3 - 620.4] |

| Wang et al 4 | China | 1 January 2020–28 January 2020 | 138 (with 61.6% censored) | 56 [42–68] | 54.3 | 7.2§ | 16.7 | 4.3 | 14.3 [2.9 - 71.1]‡ |

| Shi et al 7 | China | 20 January 2020–10 February 2020 | 416 (with 76.7% censored) | 64 (21–95)† | 49.3 | 19.7 | --- | 14.1 | 53.2 [11.4 - 248.0] |

| Guo et al 6 | China | 23 January 2020–3 February 2020 | 187 | 59±15 | 48.7 | 27.8 | 16.7 | 23.0 | 15.1 [6.7 - 34.1] |

| Chen et al 86 | China | January 2020–February 2020 | 150 | 59±16 | 56.0 | 14.7 | --- | 7.3 | 28.3 [9.2 - 87.2]‡ |

*Expressed as median [IQR] or mean±SD.

†Expressed as median (range).

‡OR of severe disease with troponin elevation.

§ Acute myocardial injury defined as biomarker above the 99th percentile upper reference limit or new abnormalities in electrocardiography or echocardiography

IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation; Tn, troponin.

The pattern in the rise of cTn levels is also significant from a prognostic standpoint. Non-survivors had a higher level of Tn elevation which continued to rise until death (mean time from symptom onset to death was 18.5 days (IQR 15–20 days)), while Tn levels for survivors remained unchanged.22 This finding may support the monitoring of cTn levels every few days in hospitalised patients.

It is a challenging task to differentiate potential aetiologies of cardiac injury: acute coronary syndrome (ACS) due to plaque rupture or thrombosis (type I myocardial infarction (MI)) or supply-demand mismatch (type II MI), myocardial injury due to DIC, and non-ischaemic injury (myocarditis, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, or cytokine release syndrome).

Ischaemic myocardial injury

Myocardial infarction

Severe viral infections can cause a systemic inflammatory response syndrome that increases the risk of plaque rupture and thrombus formation, resulting in either an ST-elevation MI or non-ST-elevation MI.24 In a study of 75 patients hospitalised with SARS, acute MI was the cause of death in two of five fatal cases.25 There is also a significant association between acute MI and influenza. As compared with the prevalence of acute MI occurred 1 year before or 7 days to 1 year after influenza, the incidence ratio of acute MI within 7 days of influenza infection was 6.1 (95% CI: 3.9 to 9.5).26 Although reports of type I MI in patients with COVID-19 have not yet been published, anecdotal report was presented.27 Treatment of ACS in COVID-19 should be according to the updated Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions guidelines.28

Severe respiratory viral infections can also lead to decreased oxygen delivery to the myocardium via hypoxaemia and vasoconstriction, as well as the haemodynamic effects of sepsis with increased myocardial oxygen demand. This supply and demand mismatch may lead to sustained myocardial ischaemia in patients with underlying coronary artery disease. However, a rise and/or fall of hs-cTn is not sufficient to secure the diagnosis of acute MI as seen in MI with non-obstructive coronaries, even in the absence of COVID-19. Therefore, the diagnosis of acute MI should also be based on clinical judgement, symptom/signs, ECG changes, and imaging studies.

Myocardial injury with DIC

DIC is a life-threatening condition present in 71.4% (15/21) of non-survivors with COVID-19 and 0.6% (1/162) of survivors.29 A marker of severe sepsis, DIC further perpetuates multiorgan damage through thrombosis, reduced perfusion, and bleeding, DIC has been implicated in the thrombosis of coronary arteries (epicardial vessels and microvasculature), focal necrosis of the myocardium, and severe cardiac dysfunction.30 Myocardial injury with DIC has been recently reported in two critically ill patients with COVID-19.31 Both patients had significantly elevated Tn and brain natriuretic peptide, which normalised after treatment with heparin, mechanical ventilation, and antiviral agents.

Non-ischaemic myocardial injury

Myocarditis and stress-induced cardiomyopathy

Myocardial injury from SARS-CoV-2 infection may also be mediated by non-ischaemic mechanisms, such as acute and fulminant myocarditis and stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Reports of various presentations of non-ischaemic myocardial injury in COVID-19 are summarised in table 5. The distinction between myocarditis and stress-induced cardiomyopathy can be challenging, since cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) and/or biopsy are not available in most cases. Fried et al and Sala et al each reported a patient with COVID-19 with mid-left ventricular (LV) or basal-to-mid LV hypokinesis, a pattern of mid-ventricular, or reverse Takotsubo stress cardiomyopathy, respectively.32 33 The incidence of acute heart failure was 33% (7/21) in critically ill patients with COVID-19 without a past history of LV systolic dysfunction in Washington state.34 Importantly, cardiomyopathy can develop in COVID-19 with mild or absent respiratory symptoms.35

Table 5.

Clinical characteristics of non-ischaemic myocardial injury in covid-19

| Study | Region | Age | Sex | Comorbidities | Symptoms/Signs | ECG | Other diagnostic studies | Biomarkers | Dx | Treatment | Outcome |

| Zeng et al 87 | China | 63 | M | Allergic cough | Fever, cough, dyspnoea | Sinus tachycardia | TTE: diffuse dyskinesia, LVEF: 32%, PAP: 44 mm Hg, RV normal | TnI, IL-6, BNP elevated | Myocarditis? | Antiviral, CRRT, corticosteroid, immunoglobulin, high-flow oxygen | Recovered, LVEF 68% |

| Inciardi et al 35 | Italy | 53 | F | None | Fever, dry cough, fatigue, hypotensive, normal oxygen saturation | Low voltage, diffuse ST-elevation, ST depression in V1 and aVR | CXR: normal; CMR: LVH, BiV hypokinesis LVEF: 35%, BiV myocardial oedema, diffuse LGE |

hs-TnT, NT-proBNP, elevated | Myopericarditis | Antiviral, corticosteroid, CQ, dobutamine, medical treatment for HF | Improved, LVEF 44% on day 6 |

| Fried et al 32 | USA | 64 | F | HTN, hyperlipidaemia | Chest pressure, afebrile, no respiratory symptoms, normal oxygen saturation | Sinus tachycardia, low QRS voltage, diffuse ST and PR elevations, ST depression in aVR | CXR: normal Cath: non-obstructive RHC: RA: 10 mm Hg, PCWP 21 mm Hg, CI: 1 L/min/m2. TTE: LVH, LVEF 30%, severe hypokinetic RV. |

TnI elevated | Myopericarditis, with cardiogenic shock | IABP, dobutamine, HCQ | Recovered, LVEF 50% on day 10 |

| Fried et al 32 | USA | 38 | M | DM | Cough, chest pain, dyspnoea, rapidly deteriorated respiratory status | SVT, Sinus tachycardia, AIVR | CXR: bilateral pulmonary opacities TTE normal (before VV ECMO), TTE: LVEF 20%–25%, akinesis of mid-LV segments; mildly reduced RV function |

TnT, IL-6, ferritin, CRP elevated | Stress cardiomyopathy | HCQ, invasive ventilation and VV ECMO, after LV function deterioration, change to VAV ECMO | Decannulated from ECMO after 7 days, stable, remain on mechanical ventilation |

| Fried et al 32 | USA | 64 | F | NICM with normal LVEF, AF, HTN, DM | Non-productive cough, afebrile, dyspnoea, oxygen saturation 88% | Sinus, PVC, PAC, lateral T inversion, QTc 528 ms | CXR: bibasilar opacities, vascular congestion TTE: severely reduced LV function |

TnT, NT-proBNP, ferritin elevated | Decompensated heart failure | Broad-spectrum antibiotics, nitroglycerin, furosemide, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor | Remain intubated on day 9 |

| Fried et al 32 | USA | 51 | M | Heart and renal transplant | Fever, dry cough, dyspnoea | New T-wave inversion | TTE: normal cardiac allograft function | hs-TnT, IL-6, NT-proBNP, ferritin elevated | Myocarditis? | MMF discontinued, HCQ, azithromycin, ceftriaxone | Discharged |

| Sala et al 33 | Italy | 43 | F | None | Chest pain, dyspnoea, oxygen saturation 89% | Sinus, new non-specific T-wave changes | CXR: multifocal bilateral opacities; Coronary CTA normal; 3D CT: mid-basal LV hypokinesia, normal apical function TTE: LVEF 43%, inferior wall hypokinesis; CMR on D7: LVEF 64%, mild hypokinesia at mid and basal LV, diffuse myocardial oedema, no LGE; EMB: lymphocytic infiltration, interstitial oedema, limited foci of necrosis, no SARS-CoV-2 genome within myocardium |

hs-TnT, NT-proBNP elevated | Myocarditis | CPAP, antiviral, HCQ | Discharged |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AIVR, accelerated idioventricular rhythm; BiV, biventricular; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CI, cardiac index; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CQ, chloroquine; CRP, C reactive protein; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; CTA, computed tomography angiogram; CXR, chest X-ray; DM, diabetes mellitus; Dx, diagnosis; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EMB, endomyocardial biopsy; HCQ, hydrochloroquine; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; NICM, non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy; NT-proBNP, N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide; PAC, premature atrial complex; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVC, premature ventricular complex; RHC, right heart catherisation; RV, right ventricle; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; Tn, troponin; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; VAV, veno-arterial-venous; VV, veno-venous.

Myocardial injury with cytokine release syndrome

Similar to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 can elicit the intense release of multiple cytokines and chemokines by the immune system.3 36 Cytokine release syndrome (aka ‘cytokine storm’), a poorly understood immunopathological process caused by hyperinduction of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, T helper 1 cytokine interferon-gamma, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), has been reported in the setting of SARS, MERS, and influenza.37–39 It is postulated that proinflammatory cytokines depress myocardial function immediately through activation of the neural sphingomyelinase pathway and subacutely (hours to days) via nitric oxide-mediated blunting of beta-adrenergic signalling.40 Accumulating evidence suggest that a subgroup of patients with severe COVID-19 can develop cytokine storm.36 Plasma levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α have been found to be significantly higher in patients with COVID-19.3 The clinical and biochemical profiles of non-survivors in patients with COVID-19 with highly elevated ferritin and IL-6 also suggest that cytokine release contribute to mortality.41

Arrhythmia

Arrhythmia could be the first presentation of COVID-19, and new-onset and/or progressive arrhythmia could indicate cardiac involvement. A study of 137 patients in Wuhan showed that 7.3% had experienced palpitations as one of their presenting symptoms for COVID-19.42 The prevalence of unspecified arrhythmia in two additional studies is listed in table 4. Arrhythmias were found to be more common in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 (44.4%) than non-ICU patients (6.9%).4 Patients with elevated Tn also had a higher incidence of malignant arrhythmia (haemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) than those with normal Tn levels (11.5% vs 5.2%, p<0.001).6

Venous thromboembolism

Due to prolonged immobilisation, hypercoagulable status, active inflammation, and propensity for DIC, patients with COVID-19 are at increased risk of VTE. The prevalence of ultrasound-confirmed deep venous thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 is 22.7%43 and 27% in ICU patients.44 Patients with cCOVID-19 have been shown to have significant higher level of D-dimer, fibrin degradation products (FDP), and fibrinogen, compared with healthy controls.45 In addition, D-dimer and FDP titres were higher in patients with severe COVID-19 than those with milder disease.45 A retrospective, multicentre cohort study demonstrated that D-dimer >1 µg/mL on admission was associated with in-hospital death (OR: 18.4, 95% CI: 2.6 to 128.6, p=0.003).22 Thus, in the setting of critically ill COVID-19 patients with clinical deterioration, VTE (including pulmonary embolism) should be considered.

Treatment considerations

There is currently no proven therapy for COVID-19, although many are under investigation. We focus our discussion here on supportive therapies and considerations of potential therapies relevant to the cardiovascular system, summarized in table 6.

Table 6.

Cardiovascular considerations in treatment

| Cardiovascular concerns | Treatment considerations |

| STEMI and NSTEMI | Primary PCI vs thrombolytics |

| Myocardial injury | Worse prognosis, monitoring rising trends |

| Hypercoaulable state | Thromboprophylaxis |

| ACEI or ARB use | Continue treatment currently, await further studies |

| HCQ, CQ and/or azithromycin use | QTc monitoring, avoid other QTc prolonging drugs |

| Immunosupression/Immunomodulation | Maybe helpful in selected patients with cytokine storm |

| MCS | IABP and VA ECMO might be used for support in cardiogenic shock |

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CQ, chloroquine; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutanous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; VA ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Anticoagulant therapy

Due to the high rate of associated arterial thromboembolism and VTE, prophylactic anticoagulation is essential in the management of hospitalised patients with COVID-19,44 46 although the optimal thromboprophylaxis regimen is unclear. In a retrospective study of 449 patients with severe COVID-19, 99 patients received unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin for at least 7 days.47 No difference in overall 28-day mortality was observed, but in subgroups of patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy score ≥4, or D-dimer >sixfold of upper limit of normal, the heparin group had lower mortality compared with the no-heparin group (40.0% vs 64.2%, p=0.029), (32.8% vs 52.4%, p=0.017), respectively.47 Another concern regarding thromboprophylaxis is the drug-drug interaction between some antiviral treatments (such as ribavirin, lopinavir and ritonavir) and direct oral anticoagulants. Low molecular weight heparin is likely preferred in critically ill patients with COVID-19, if anticoagulation is used.

ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers

Since SARS-CoV-2 uses the ACE2 protein for ligand binding before entering the cell,10 there are concerns regarding the use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors that may increase ACE2 expression.13 48 The relationship between ACE2 expression and SARS-CoV-2 virulence is uncertain. After cell entry via ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 appears to subsequently downregulate ACE2 expression, which is vital to maintenance of cardiac function.49 In mouse models, reduction in ACE2 expression is associated with increased severity of lung injury induced by influenza.50 Whether higher expression of ACE2 increases susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection or confers cardioprotection remains controversial.51 Furthermore, experimental animal models and few studies in humans have yielded conflicting results as to whether RAAS inhibition increases ACE2 expression.52 53 Based on the uncertainty regarding the overall effect of RAAS inhibitors (ACE inhibitor (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy) in COVID-19, multiple specialty societies currently recommend that RAAS inhibitors be continued in patients in otherwise stable condition.51

Hydroxychloroquine/Chloroquine and azithromycin

Chloroquine is a versatile bioactive agent with antiviral activity in vitro against DNA viruses as well as various RNA viruses, including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, prompting it to be studied for patients with COVID-19.54 Similar to chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine confers antiviral effects and has an additional modulating effect on activated immune cells to decrease IL-6 expression.55 Non-randomised, observational studies of >100 patients at 10 hospitals in China suggest that chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine is superior to the control treatment in resolving pneumonia (based on clinical and imaging findings), promoting conversion to viral negative status and shortening the disease course.56 In a small open-label, non-randomised study conducted in France, 70% of hydroxychloroquine-treated patients with COVID-19 had undetectable viral titres at 6 days, compared with 12.5% in the control group (p=0.001),57 although there were major methodological concerns with the study. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic which acts against Zika and Ebola viruses in vitro58 and suppresses inflammatory processes,59 has been proposed as an effective adjunct to hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 through unclear mechanisms.57 Although the preliminary evidence for quinoline antimalarials may be promising, it should be taken with caution until randomised clinical trials are completed.

Both chloroquine and azithromycin have generally favourable safety profiles, but they are known to cause cardiovascular side effects including prolongation of QT interval.60 Although azithromycin interferes minimally with the cytochrome P-450 system in vitro,61 chloroquine is metabolised by CYP2C8 and CYP3A4/5,62 and there is a potentially enhanced risk of significant QT prolongation induced by combination therapy. Guidance for managing QTc prolongation in COVID-19 pharmacotherapies and other cardiac electrophysiology issues related to covid-19 has recently been published by the Heart Rhythm Society.63

Immunosuppressive therapy

As for SARS and MERS, corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for COVID-19 and might exacerbate the resulting lung injury.64 However, given the detrimental effects of the cytokine release syndrome associated with COVID-19 on the cardiopulmonary system, immunosuppressive therapy to dampen the hyperinflammatory response may be beneficial.36 Screening patients with COVID-19 using laboratory data (increasing ferritin and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and decreasing platelets) and a proposed score for the hemophagocytic response (HScore)65 for hyperinflammation may help to identify patients for whom immunosuppression might improve survival.36

IL-6 inhibitors may have a role as immunomodulators. Tocilizumab, an inhibitor of the IL-6 receptor, was shown to effectively improve symptoms and prevent clinical deterioration in a retrospective case series study of 21 COVID-19 patients with severe or critical disease.66 Several clinical trials are ongoing to assess the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab (NCT04317092)67 or sarilumab, another IL-6 inhibitor (NCT04327388)68 in patients with COVID-19.

Mechanical cardiopulmonary support

Mechanical cardiopulmonary support in respiratory failure has been reported with variable survival rates. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry is being adapted to investigate COVID-19 in prospective observational studies addressing the role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in these critically ill patients.69

In the setting of cardiogenic shock related to COVID-19, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), or veno-arterial ECMO should be considered. During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Japan, 9 out of 13 patients with fulminant myocarditis receiving emergent mechanical circulatory support (IABP and/or percutaneous cardiopulmonary support) survived, while all four patients with fulminant myocarditis treated without mechanical circulatory support died.70 A case has been reported of a patient with COVID-19 without respiratory symptoms presenting with cardiogenic shock attributed to acute myopericarditis and successfully treated with IABP support.32 Perhaps a more likely scenario is the conversion of veno-venous ECMO for ARDS to veno-arterial-venous ECMO on development of cardiogenic shock, as described in another case report.32 Regardless of the mode of mechanical support, patient selection should involve consideration of comorbidities and potential complications.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is similar to SARS and MERS with regard to host vulnerability, specifically in those with substantial cardiovascular comorbidities. Greater transmissibility of COVID-19 has resulted in a worldwide pandemic, a record number of infected individuals and an excess mortality that far exceeded previous coronavirus-related outbreaks. Myocardial injury is common in COVID-19 and portends a worse prognosis. Differentiating between the various causes of myocardial injury is crucial to determining the treatment course. The cardiovascular considerations for treatment, including anticoagulation, ACEI or ARB use, anti-arrhythmic management, immunosuppression/modulation, and haemodynamic support, are important and continue to evolve.

Footnotes

Twitter: @tiffchenMD

Contributors: YK, TC, DM, and YH drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. WHO Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation Report-1, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4

- 2. JHU Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases by the center for systems science AD engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. Available: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Accessed 12 Apr].

- 3. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ChinaCDC The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly 2020;2:113–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Govaert TM, Thijs CT, Masurel N, et al. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. JAMA 1994;272:1661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270–3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [Epub ahead of print: 04 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:586–90. 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Esler M, Esler D. Can angiotensin receptor-blocking drugs perhaps be harmful in the COVID-19 pandemic? J Hypertens 2020;38:781–2. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med 2020. 10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0. [Epub ahead of print: 12 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yao XH, Li TY, He ZC, et al. [A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2020;49:E009. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prabhu SD. Cytokine-induced modulation of cardiac function. Circ Res 2004;95:1140–53. 10.1161/01.RES.0000150734.79804.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levi M, van der Poll T, Büller HR. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation 2004;109:2698–704. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131660.51520.9A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ding Y, Wang H, Shen H, et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J Pathol 2003;200:282–9. 10.1002/path.1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farcas GA, Poutanen SM, Mazzulli T, et al. Fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome is associated with multiorgan involvement by coronavirus. J Infect Dis 2005;191:193–7. 10.1086/426870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alsaad KO, Hajeer AH, Al Balwi M, et al. Histopathology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronovirus (MERS-CoV) infection - clinicopathological and ultrastructural study. Histopathology 2018;72:516–24. 10.1111/his.13379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ng DL, Al Hosani F, Keating MK, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of a fatal case of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am J Pathol 2016;186:652–8. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zheng YY, YT M, Zhang JY, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Warren-Gash C, Hayward AC, Hemingway H, et al. Influenza infection and risk of acute myocardial infarction in England and Wales: a caliber self-controlled case series study. J Infect Dis 2012;206:1652–9. 10.1093/infdis/jis597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peiris JSM, Chu CM, Cheng VCC, et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 2003;361:1767–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med 2018;378:345–53. 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. ACC ACC/Chinese cardiovascular association COVID-19 Webinar 1. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjEhV68GcD8

- 28. Szerlip M, Anwaruddin S, Aronow HD, et al. Considerations for cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic perspectives from the Society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions emerging leader mentorship (ScaI elm) members and graduates. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2020. 10.1002/ccd.28887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:844–7. 10.1111/jth.14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sugiura M, Hiraoka K, Ohkawa S, et al. A clinicopathological study on cardiac lesions in 64 cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Jpn Heart J 1977;18:57–69. 10.1536/ihj.18.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang YD, Zhang SP, Wei QZ, et al. [COVID-19 complicated with DIC: 2 cases report and literatures review]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2020;41:E001. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation 2020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sala S, Peretto G, Gramegna M, et al. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J 2020. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa286. [Epub ahead of print: 08 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020;395:1033–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Z, Zhang A, Wan Y, et al. Early hypercytokinemia is associated with interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 dysfunction and predictive of fatal H7N9 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:769–74. 10.1073/pnas.1321748111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wong CK, Lam CWK, Wu AKL, et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 2004;136:95–103. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim ES, Choe PG, Park WB, et al. Clinical progression and cytokine profiles of middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:1717–25. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mann DL. Innate immunity and the failing heart: the cytokine hypothesis revisited. Circ Res 2015;116:1254–68. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.302317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu K, Fang Y-Y, Deng Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J 2020. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [Epub ahead of print: 07 Feb 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shi Z, Fu W. Diagnosis and treatment recommendation for novel coronavirus pneumonia related isolated distal deep vein thrombosis. Shanghai Medical Journal, 2020. Available: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1366.R.20200225.1444.004.html

- 44. Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [Epub ahead of print: 10 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Han H, Yang L, Liu R, et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020. 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [Epub ahead of print: 16 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shanghai Clinical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19 [Comprehensive treatment and management of coronavirus disease 2019: expert consensus statement from Shanghai]. Chin J Infect 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020. 10.1111/jth.14817. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sommerstein RGC. Preventing a COVID-19 pandemic: ACE inhibitors as a potential risk factor for fatal COVID-19. BMJ 2020;368:M810-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 2002;417:822–8. 10.1038/nature00786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang P, Gu H, Zhao Z, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) mediates influenza H7N9 virus-induced acute lung injury. Sci Rep 2014;4:7027. 10.1038/srep07027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation 2005;111:2605–10. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Luque M, Martin P, Martell N, et al. Effects of captopril related to increased levels of prostacyclin and angiotensin-(1-7) in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1996;14:799–805. 10.1097/00004872-199606000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020;30:269–71. 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sahraei Z, Shabani M, Shokouhi S, et al. Aminoquinolines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;105945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 2020;14:72–3. 10.5582/bst.2020.01047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;105949:105949. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 58. Retallack H, Di Lullo E, Arias C, et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:14408–13. 10.1073/pnas.1618029113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simoens S, Laekeman G, Decramer M. Preventing COPD exacerbations with macrolides: a review and budget impact analysis. Respir Med 2013;107:637–48. 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. White NJ. Cardiotoxicity of antimalarial drugs. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:549–58. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70187-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fohner AE, Sparreboom A, Altman RB, et al. PharmGKB summary: macrolide antibiotic pathway, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2017;27:164–7. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim K-A, Park J-Y, Lee J-S, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C8 and CYP3A4/5 are involved in chloroquine metabolism in human liver microsomes. Arch Pharm Res 2003;26:631–7. 10.1007/BF02976712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Gopinathannair R, et al. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from the heart rhythm Society COVID-19 Task force; electrophysiology section of the American College of cardiology; and the electrocardiography and arrhythmias Committee of the Council on clinical cardiology, American heart association. Circulation 2020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047063. [Epub ahead of print: 31 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet 2020;395:473–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2613–20. 10.1002/art.38690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. ChinaXiv 2020:20200300026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. National Cancer Institute Naples Tocilizumab in COVID-19 pneumonia (TOCIVID-19). Available: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04317092

- 68. Sanofi Sarilumab COVID-19. Available: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04327388

- 69. Ramanathan K, Antognini D, Combes A, et al. Planning and provision of ECMO services for severe ARDS during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Respir Med 2020. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30121-1. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ukimura A, Ooi Y, Kanzaki Y, et al. A national survey on myocarditis associated with influenza H1N1pdm2009 in the pandemic and postpandemic season in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2013;19:426–31. 10.1007/s10156-012-0499-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mertz D, Kim TH, Johnstone J, et al. Populations at risk for severe or complicated influenza illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f5061. 10.1136/bmj.f5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chan JWM, Ng CK, Chan YH, et al. Short term outcome and risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes in adults with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Thorax 2003;58:686–9. 10.1136/thorax.58.8.686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Badawi A, Ryoo SG. Prevalence of comorbidities in the middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2016;49:129–33. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. CDC Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 — United States 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2020 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2020;141:e139–596. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Liu Y, et al. Urban-Rural County and State Differences in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:205–11. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hu S, Gao R, Liu L, et al. Summary of the 2018 report on cardiovascular disease in China. Chinese Circulation Journal 2019;34. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:458–64. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [Epub ahead of print: 06 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. CDC FluServ-Net Weekly U.S. influenza surveillance report. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/

- 81. Booth CM, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA 2003;289:2801–9. 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:420–2. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tian S, Xiong Y, Liu H, et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through post-mortem core biopsies. Preprints 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fox SE, Akmatbekov A, Harbert JL, et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in Covid-19: the first autopsy series from new Orleans. medRxiv 2020:2020.04.06.20050575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lang Z-W, Zhang L-J, Zhang S-J, et al. A clinicopathological study of three cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Pathology 2003;35:526–31. 10.1080/00313020310001619118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chen C, Chen C, Yan JT, et al. [Analysis of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 and association between concomitant cardiovascular diseases and severity of COVID-19]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2020;48:E008. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200225-00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zeng JHL, Yuan Y, Wang J, et al. First case of COVID-19 infection with fulminant myocarditis complication: case report and insights. Preprints, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]