Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this work is to investigate the improvement of physical function and its determinants in axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) patients treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in a real clinical practice setting.

Methods

An observational study was conducted in patients with axial SpA treated with anti-TNF from 2010 to 2018 with a minimum 6 months of follow-up. All patients fulfilled ASAS or the modified New York criteria. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) were used as objective and self-reported functional indices. The improvement of function and factors associated were evaluated for the present study, as well as disease activity and patient-reported outcome measures.

Results

A total of 183 patients with axial SpA were examined. Among them, 27 were non-radiographic axial SpA, while the remaining 156 were ankylosing spondylitis patients. BASFI and BASMI significantly improved during follow-up. Improvement of metrology index BASMI inverse correlated with disease duration (rho − 0.2, p = 0.009) and directly correlated with the improvement of BASDAI (rho 0.26, p = 0.003) and CRP (rho 0.26, p = 0.0003). Improvement of BASFI significantly inversely correlated with disease duration and directly correlated with the improvement of BASDAI, CRP, and baseline ESR. Male sex, lower disease duration, high ESR, and the improvement of BASDAI were found to be associated with the improvement of BASFI.

Conclusions

Our results showed that in real-life settings, patients improve in BASMI and BASFI. Furthermore, factors associated with this improvement were identified.

Keywords: Axial spondyloarthritis, Anti-TNF, Function, Outcomes

Key Summary Points

| Anti-TNF drugs improve function measures in patients with axial spondyloarthritis in real-life settings. |

| Male sex, shorter disease duration, baseline erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and pain were associated with the extent of functional improvement. |

| These parameters should be carefully evaluated in the management and follow-up of axial spondyloarthritis patients. |

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a group of inflammatory diseases that encompasses ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and non-radiographic axial SpA (nr-axSpA), affecting mainly the axial skeleton [1, 2]. The degree (extent) of inflammatory lesions at entheseal sites and the subsequent new bone formation lead to functional impairment and disability, mainly in those patients who develop extensive syndesmophytes formation [1]. The induction of remission, the maintenance of good quality of life, articular function and workability, together with the impact of fatigue and other self-reported symptoms are of crucial importance in the long-term management of axSpA patients [3, 4]. Randomized clinical trials with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) antagonists and interleukin (IL) 17A inhibitors showed the efficacy of these drugs in the induction of clinical response and in the achievement of a state of clinical remission in most of the patients [5–9]. Furthermore, factors associated with a better response to treatment such as high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, male sex, and the extent of inflammation at MRI were identified [10–12]. Improvement of function and quality of life was also shown in short- and long-term clinical trials using biologic drugs. Studies coming from registries have already shown that functional status, which represents one of the most important long-term outcomes of this disease, is related to both presence of structural damage of the spine and to the persistence of high disease activity [13]. However, despite the potential “cause–effect” association between the reduction of spinal mobility due to the inflammatory process and quality of life, few studies assessed the improvement of function and the associated clinical factors in a real-life setting. Therefore, the assessment of clinical and laboratory factors potentially associated to the achievement of better physical function could be important in the management of SpA patients.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the level of functional improvement assessed with the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) [14] and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) [15] in a group of axSpA patients treated with TNFα antagonists in a real clinical practice setting. Secondary end-points were the assessment of the potential clinical determinants of functional improvement.

Methods

Study Design

An observational study was conducted in five Italian tertiary referral rheumatology centers (Campobasso, Milano, Padova, Potenza, and Reggio Emilia) where a SpA clinic was carried out and with expertise in research studies on these conditions. Subject’s written consent for the use of personal data was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Data on effectiveness and safety of axial SpA patients treated with their first TNFα blockers with a minimum of 6 months of follow-up from 2010 to 2018 were collected in all five centers. All patients fulfilled ASAS [2] or the modified New York criteria [16] for the classification of axial SpA or AS, respectively.

At the time of initiation and at follow-up visits of anti TNFα treatment, the main patient's data were collected including age, sex, diagnosis, disease duration, extra-articular manifestations (EAM) (i.e., uveitis, inflammatory bowel diseases -IBD-, psoriasis), BASMI, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [17], BASFI, patient’s visual analog scale (VAS) on global disease activity spinal pain (0–10 cm), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP, clinical predominant pattern (axial, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis), swollen (out of 66) and tender (out of 68) joints, as well as radiological data recorded as positive/negative for sacroiliac joints.

Significant clinical improvement for the BASFI value (defined as a difference of at least two points at last follow-up visit in respect to baseline evaluation) and improvement in BASMI (defined as at least 1 point of improvement) were investigated.

Details of past and present anti-rheumatic therapies, such as conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or analgesics, and current comorbidities have also been recorded.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Molise. (protocol n. 0001-09-2017).

Statistical Analysis

After testing for normal distribution of data, descriptive results were reported as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) values for continuous variables, and number (percentages) for categorical ones.

To assess improvement of functional indices between baseline and follow-up, t test for paired data or Wilcoxon test were used for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. When comparing patients with or without a clinically significant improvement in BASFI or BASMI, for continuous variables, the significance of the differences was determined using Student’s t test for unpaired data for variables normally distributed and the Mann–Whitney U test for unpaired samples for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were analyzed by χ-square test with Yates’ correction or Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between the level of improvement of physical function with clinical and laboratory characteristics were assessed by using the Spearman rho correlation coefficient.

Determinants of function improvement were explored using both univariate and multivariate analysis (logistic regression analysis). p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

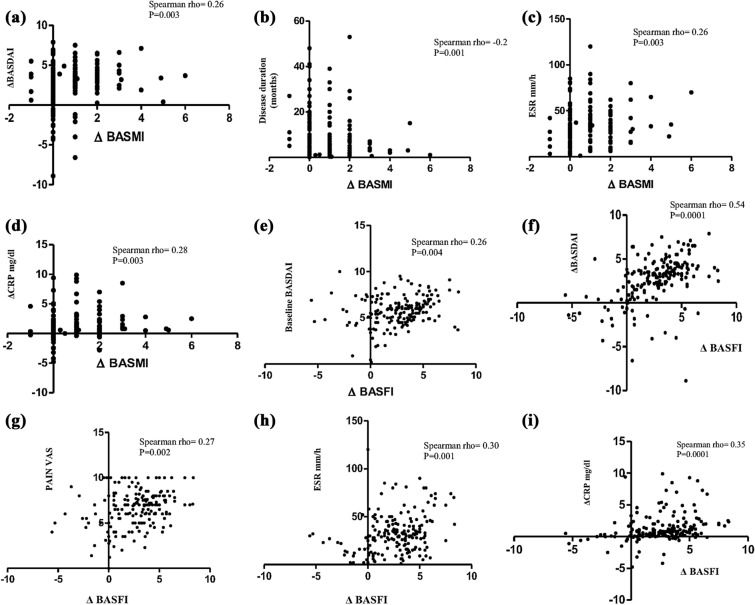

A total of 183 patients with axial SpA, including nr-axSpA (n = 27) and AS (n = 156) treated with TNF inhibitors fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were selected from our databases. The baseline characteristics of these groups of patients are shown in Table 1. These patients represent a typical axial SpA group with an HLA-B27 rate of 70.4%. During a median (IQR) follow-up of 3 (1–4.5) years, 89 (48.6%) patients had a BASMI improvement of at least 1 point, while 118 (64.4%) had a BASFI improvement of at least 2 points. Figure 1 shows the difference in the two functional indices between baseline and follow-up visit: median BASFI and BASMI significantly improved during follow-up. Mean (SD) change from baseline to follow-up was − 0.86 (0.95) for the BASMI and − 2.6 (2.4) for the BASFI. Improvement (Δ) of metrology index BASMI inverse correlated with disease duration (rho = − 0.2, p = 0.001) and directly correlated with baseline ESR (rho = 0.26, p = 0.0003), with the improvement (Δ) of BASDAI (rho = 0.26, p = 0.003) and with the improvement (Δ) of CRP (rho 0.28, p = 0.003). Improvement (Δ) of BASFI significantly direct correlated with baseline patient VAS on spinal pain, with baseline value of the BASDAI and with the improvement (Δ) of BASDAI, and CRP (Fig. 2). At univariate analysis, male sex, lower disease duration, high ESR value, pain, overall global disease activity on physician VAS, and the magnitude of the improvement in disease activity indices were found to be associated with the improvement of BASFI as showed in Table 2. However, male sex was not found to be associated with BASMI improvement. Logistic regression analysis is shown in Table 3. This analysis confirms the association between male sex, shorter disease duration, baseline ESR, and VAS pain with the extent of functional improvement.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of axSpA (n = 183) patients at baseline

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Male/female | 133/50 |

| Age; years (mean/SD) | 43.3 (12.5) |

| Median disease duration; years; median (IQR) | 6 (1.6–12.5) |

| Presence of HLA-B27; n (%) | 129 (70.4) |

| CRP; mg/dl; median (IQR) | 1.3 (0.8–2.6) |

| ESR mm/I h; median (IQR) | 30 (17–42) |

| BASDAI; median (IQR) | 5.9 (4.8–6.8) |

| BASMI; median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| BASFI; median (IQR) | 5.5 (4.1–6.8) |

| PtGA; median (IQR) cm | 6.7 (5.5–7.7) |

| VAS physician; median (IQR) cm | 6 (5–6.5) |

| VAS back pain; median (IQR) cm | 7 (5.2–8) |

| Presence of grade IV sacroiliitis; n (%) | 46 (25.1) |

| Presence of extra-articular manifestations (IBD, psoriasis, uveitis); n (%) | 50 (27.3) |

| Therapy; n (%) | |

| INF | 78 (42.6) |

| ADA | 36 (19.6) |

| ETA | 58 (31.7) |

| GOL | 11 (6.1) |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, PtGA Patient’s Global Assessment, VAS visual analog scale, INF infliximab, ADA adalimumab, ETA etanercept, GOL golimumab

Fig. 1.

Improvement of BASMI and BASFI indices (box and whiskers-median/IQR) between baseline and last follow-up visit

Fig. 2.

Correlations (Spearman rho) between the extent (Δ) of BASMI improvement with Δ values of BASDAI (a), disease duration (b), baseline ESR (c), and Δ values of CRP (d). Correlations (Spearman rho) between the extent (Δ) of BASFI improvement with baseline BASDAI (e), Δ values of BASDAI (f), baseline pain VAS (g), baseline ESR (h), and Δ values of CRP (i)

Table 2.

Comparison between patients with and without functional improvement (BASMI and BASFI) (t test or Mann–Whitney U test for unpaired samples)

| Patients with BASMI improvement (n = 89) |

Patients with no BASMI improvement (n = 91) |

p value | Patients with BASFI improvement (n = 117) |

Patients with no BASFI improvement (n = 64) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 51.8% | 48.2% | n.s | 69.9% | 31.1% | 0.01 |

| Female sex | 40% | 60% | 50% | 50% | ||

| Age; median (IQR) | 43 (33–54.5) | 41.5 (33–52) | n.s | 41.(33–52.2) | 44 (33.5–55.5) | n.s |

| Disease duration; median (IQR) | 4 (1.2–9) | 8 (2.25–15) | 0.02 | 5 (1.2–12) | 8 (3–15) | 0.03 |

| PtGA; median (IQR) | 6.8 (6–7.8) | 6.7 (5.5–7-9) | n.s | 6.8 (6–7.7) | 6.7 (5.5–8) | n.s |

| VAS pain; median (IQR) | 7 (6–8) | 6.9 (5–8.2) | n.s | 7 (6–8) | 6.5 (5–8.3) | 0.01 |

| Physician VAS; median (IQR) | 6 (5.5–6.5) | 5.5 (4.5–6.5) | 0.02 | 6 (5–6.5) | 5.5 (4.4–6.5) | 0.02 |

| BASDAI (baseline); median (IQR) | 6 (5–6.7) | 5.9 (4.6–5.2) | n.s | 6 (5.1–6.7) | 5.6 (4.4–7.2) | 0.04 |

| change in BASDAI score; median (IQR) | − 3.5 (2.4–4.4) | − 2.9 (0.75–3.89) | < 0.01 | − 3.5 (2.8-.4) | − 1.1 (− 0.5 to 2.9) | < 0.01 |

| Baseline CRP (mg/dl); median (IQR) | 1.4 (1.05–2.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | n.s | 1.3 (0.87–2.8) | 1.4 (0.75–2.45) | n.s |

| Baseline ESR (mm/h); median (IQR) | 34 (26.5–45.5) | 26.5 (13–35.2) | < 0.01 | 32 (23–45) | 25 (11.5–35.5) | < 0.01 |

| Presence of enthesitis* | 57.1% | 42.8% | n.s | 68.8% | 32.2% | n.s |

| Absence of enthesitis | 41.9% | 58.1% | 60.9% | 39.1% | ||

| Presence of grade IV sacroiliitis | 43.4% | 56.6% | n.s | 71.7% | 28.3% | n.s |

| Absence of grade IV sacroiliitis | 51.2% | 48.8% | 65.5% | 34.5% | ||

| Diagnosis: AS | 48% | 52% | n.s | 64.9% | 35.1% | n.s |

| Diagnosis: SpA | 51.8% | 48.2% | 66.6% | 33.4% |

IQR interquartile range, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, PtGA Patient’s Global Assessment, VAS visual analog scale

*Defined as a MASES score ≥ 1

Table 3.

Factors associated with functional improvement (BASMI and BASFI) (logistic regression analysis)

| BASMI | BASFI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.03 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.20 | 3.34 | 1.57–7.11 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | 0.41 |

| Disease duration (years) | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.03 |

| HLA-B27 | 0.96 | 0.94–1.3 | 0.2 | 0.95 | 0.92–1.03 | 0.16 |

| Physician VAS | 1.23 | 0.93–1.63 | 0.15 | 1.12 | 0.84–1.51 | 0.44 |

| VAS pain | 1.26 | 1.02–1.57 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.90–1.38 | 0.32 |

| Baseline ESR | 1.02 | 1–1.03 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.10 |

| Baseline BASDAI | 0.83 | 0.63–1.10 | 0.20 | 1.25 | 0.93–1.67 | 0.13 |

| Baseline CRP mg/dl | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.06 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.08 |

BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, OR odds ratio, VAS visual analog scale, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

Discussion

The concept of disease remission plays a relevant role in the management of axSpA. Remission should consider different aspects of the disease such as clinical disease activity, objective inflammation and, probably, function and structural damage. This concept of remission has demonstrated to be an achievable target in axSpA [5, 6]. A previous definition of remission was developed by the ASAS group: partial remission considers four domains (patient global assessment, pain, physical function, and inflammation) in which function has a key role [18]. More recently, the ASAS group developed the composite index Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) in which there is no mention on function, as the aim was to develop composite index that is focused mainly on disease activity, with higher sensitivity to change and in order to avoid the possible confounding role of damage in the assessment [19]. However, the assessment of physical function remains central in the management of SpA patients [20] and, with the development of new drugs that might be more active on function and, possibly even on damage, the assessment of factors associated with the improvement of physical function are of great importance. Anti-TNFα clinical trials in axSpA demonstrated the efficacy of these drugs in long-term improvement of function. Four years of follow-up data of the Rapid-axSpA trial showed a mean reduction of 2.3 points in the BASFI score and 0.86 point in the BASMI score in patients treated with the anti-TNF certolizumab pegol [21]. Studies with other compounds confirm these results [22]. Our results, obtained in a clinical setting and with a long median follow-up, also confirm this trend with similar data. Furthermore, recent data coming from registries showed the effectiveness of anti-TNF in the improvement of function in long-term follow-up. In the DESIR cohort, Moltò et al. showed a mean change in BASFI score of 12.9 in 197 early axial SpA patients treated with anti-TNF over a follow-up of 24 months. However, BASMI was not included in this analysis [23]. Baraliakos et al. found sustained low levels over the 7 years of the study in BASFI and BASMI measures. Both measures decrease from baseline respectively of two and one points after anti-TNF treatment [24].

In a recent work, improvements in quality of life in a large real-world population treated with anti-TNF, higher ASDAS, elevated CRP, and younger age were associated with the improvement of function [25]. On the other hand, in a study performed using 2 years of follow-up data from the GESPIC cohort, authors demonstrated that 27.5% and 12% of patients experienced a worsening of BASMI and BASDAI during follow-up. Moreover, this worsening was associated with worsening of disease activity assessed with BASDAI [26]. In our study, we showed specular results with the improvement of physical function directly correlated with improvement of disease activity evaluated by BASDAI and CRP. Furthermore, male sex, shorter disease duration, and high values of ESR at the time of anti-TNF initiation were found to be associated with the improvement of BASFI. Cansu et al. previously showed that higher CRP values were associated with poor functional status, and it was wide demonstrated that high CRP levels were associated with a progression of radiographic damage [27]. However, despite this, high CRP levels were a well-known predictive factor for a better response to anti-TNF treatment and we demonstrated that reduction of CRP levels and high baseline ESR levels correlate, and were associated with, better functional outcome. Interestingly, patient-reported outcomes such as baseline pain VAS were correlated with the extent of BASMI improvement.

Our study had some limitations. First, the design that could lead to selection and/or potential information bias; second, the lack of the assessment of radiographic progression that was not available in all patients although it is one of the major determinants of disability. Finally, we did not have the possibility to assess disease activity with the more recent composite index ASDAS because some of the enrolled patients in 2010 did not have available data of ASDAS components. However, the long median follow-up and the results showed confirm that improvements in disease activity are strictly associated with the possibility of having an improvement of function, since, mainly in patients with shorter disease duration, a great part of functional impairment is caused by inflammatory activity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, functional status in patients with axial SpA improved after treatment with anti-TNF drugs and the extent of improvement was correlated with the improvement of disease activity and with disease duration. Our results confirm that, by acting in the early stage of disease in patients with high inflammatory burden, a better outcome could be obtained.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All authors should have made substantial contributions to all of these sections: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Disclosures

Ennio Lubrano, Fabio Massimo Perrotta, Maria Manara, Salvatore D’Angelo, Roberta Ramonda, Leonardo Punzi, Olga Addimanda, Carlo Salvarani, and Antonio Marchesoni have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Molise. (protocol n. 0001-09-2017).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11791917.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2017;390:73–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–883. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:978–991. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lubrano E, De Socio A, Perrotta FM. Unmet needs in axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;55:332–339. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spadaro A, Lubrano E, Marchesoni A, et al. Remission in ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-TNF-α drugs: a national multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1914–1919. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lubrano E, Perrotta FM, Marchesoni A, et al. Remission in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α drugs: an Italian multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:258–263. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callhoff J, Sieper J, Weiß A, Zink A, Listing J. Efficacy of TNFα blockers in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1241–1248. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, MEASURE 1 study group et al. Effect of secukinumab on clinical and radiographic outcomes in ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results from the randomised phase III MEASURE 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1070–1077. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubrano E, Perrotta FM. Secukinumab for ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1587–1592. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vastesaeger N, van der Heijde D, Inman RD, et al. Predicting the outcome of ankylosing spondylitis therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:973–981. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.147744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudwaleit M, Schwarzlose S, Hilgert ES, Listing J, Braun J, Sieper J. MRI in predicting a major clinical response to anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1276–1281. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubrano E, Perrotta FM, Manara M, et al. The sex influence on response to tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors and remission in axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:195–201. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.17666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poddubnyy D, Listing J, Haibel H, Knüppel S, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. Functional relevance of radiographic spinal progression in axial spondyloarthritis: results from the GErman SPondyloarthritis Inception Cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:703–711. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, Kennedy LG, Garret SL, Calin A. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1694–1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garret S, Jenkinson T, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1876–1886. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1876::AID-ART326>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukas C, Landewé R, Sieper J, et al. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:18–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heijde D, Calin A, Dougados M, Khan MA, Linden S, Bellamy N. Selection of instruments in the core set for DC-ART, SMARD, physical therapy, and clinical record keeping in ankylosing spondylitis. Progress report of the ASAS Working Group. Assessments in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:951–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Landewé R, et al. Sustained efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes of certolizumab pegol in axial spondyloarthritis: 4-year outcomes from RAPID-axSpA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:1498–1509. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun J, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:661–667. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moltó A, Paternotte S, Claudepierre P, Breban M, Dougados M. Effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor α blockers in early axial spondyloarthritis: data from the DESIR cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1734–1744. doi: 10.1002/art.38613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baraliakos X, Haibel H, Fritz C, Listing J, Heldmann F, Braun J, Sieper J. Long-term outcome of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis with etanercept-sustained efficacy and safety after seven years. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R67. doi: 10.1186/ar4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van den Bosch F, Flipo RM, Braun J, Vastesaeger N, Kachroo S, Govoni M. Clinical and quality of life improvements with golimumab or infliximab in a real-life ankylosing spondylitis population: the QUO-VADIS study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37:199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poddubnyy D, Haibel H, Listing J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. Identification of determinants of the functional outcome in patients with early axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. 2013.

- 27.Cansu DU, Calışır C, Savaş Yavaş U, Kaşifoğlu T, Korkmaz C. Predictors of radiographic severity and functional disability in Turkish patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:557–562. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.