Abstract

Background

Hypertension is regarded as a major and independent risk factor of cardiovascular diseases, and numerous studies observed an inverse correlation between vitamin C intake and blood pressure.

Aim

Our aim is to investigate the relationship between serum vitamin C and blood pressure, including the concentration differences and the correlation strength.

Method

Two independent researchers searched and screened articles from the National Library of Medicine, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, VIP databases, and WANFANG databases. A total of 18 eligible studies were analyzed in the Reviewer Manager 5.3 software, including 14 English articles and 4 Chinese articles.

Results

In the evaluation of serum vitamin C levels, the concentration in hypertensive subjects is 15.13 μmol/L lower than the normotensive ones (mean difference = −15.13, 95% CI [-24.19, -6.06], and P = 0.001). Serum vitamin C has a significant inverse relation with both systolic blood pressure (Fisher′s Z = −0.17, 95% CI [-0.20, -0.15], P < 0.00001) and diastolic blood pressure (Fisher′s Z = −0.15, 95% CI [-0.20, -0.10], P < 0.00001).

Conclusions

People with hypertension have a relatively low serum vitamin C, and vitamin C is inversely associated with both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a series of disorders of blood vessels and the heart, primarily including coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and rheumatic heart disease [1]. Owing to its increasingly high worldwide morbidity and gradual tendency in younger people, CVD is considered to be one of the most serious diseases that damaged public health in the 21st century [2]. The number of deaths due to CVD is increasing year by year. For example, a total of 17.9 million individuals died from cardiovascular events in 2015, which is much higher than that in 1990 [3]. In developing countries, it is reported that more than 75% of CVD deaths occur; approximately 41% of total deaths in China are related to CVD with an annual death toll reaching 3.5 million [4–6].

Individuals with a risk of CVD might manifest with a raised blood pressure (BP) [7]. As researches continuing, numerous epidemiological studies have repeatedly recognized that hypertension is a major and independent risk factor of CVD [1, 8, 9]. As the most common chronic noninfectious disease, hypertension is closely related to several risk factors, including genetics [10, 11], family history [12–14], overweight and obesity [15], tobacco smoking [15–18], physical inactivity [19, 20], and unhealthy dietary intake [17, 20]. Nutrient intake and electrolyte level are complex and varied, but population-based evidence has shown that the consumption of magnesium, sodium, potassium, and calcium is inversely associated with BP [21, 22]. Other studies also revealed the relationship between vitamin C and BP, one of which was that hypertensive patients present a lower intake and serum vitamin C [23]. A variety of observational and interventional studies has additionally reported that vitamin C intake and its concentration status were significantly related to a reduction of resting BP [24]. For example, Kamran et al. [25] found that the correlation between vitamin C intake and systolic BP was -0.02 in uncontrolled hypertensive patients. Yet another study by Yoshioka et al. [26] discovered that serum vitamin C had an inverse and the strongest association with systolic BP. Given the potential oxidation resistance of vitamin C, researchers attributed this association to that vitamin C could prevent the formation of free radicals, thereby reducing the vascular oxidative in the progress of hypertension [27]. However, these preliminary findings have not been confirmed, since some researchers drew an opposite conclusion, like the study conducted by Duthie et al. [28]. Even relevant systematical review and meta-analysis articles have not been found regarding the relationship between them.

To consider the controversial role of vitamin C in the prevention and management of hypertension, we are inspired to conduct this meta-analysis, with a purpose to compare serum vitamin C levels between hypertensive and normotensive individuals. Furthermore, we aim to confirm whether there was a correlation between serum vitamin C and BP and calculate the strength of the relationship.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Two independent reviewers comprehensively searched the National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Cochrane Library, Web of Science (WOS), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP databases, and WANFANG databases to obtain relevant studies from their earliest publication up to January 2019. We used the following searching strategy: (Vitamin C OR ascorbic acid OR risk factor) AND (hypertension OR high blood pressure OR blood pressure). There was no limitation to language. All the records were screened and scrutinized independently by two partners. All the studies were screened and selected according to the guidelines for Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies (MOOSE) [29].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The eligible studies should fulfill the inclusion criteria as follows: (1) investigated the relation between serum vitamin C and blood pressure among hypertensive subjects or normotensives; (2) participants were males or females over 18 years old; (3) observational articles including cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, and cohort studies; (4) provided with Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), Spearman's correlation coefficient (rs), or regression coefficient (b); (5) the means and standard deviations (SD) of serum vitamin C were available in case-control studies; and (6) if there were over two similar articles published based on the same sample, the one with higher quality would be included.

Studies were excluded with the following criteria: (1) duplicated or similar articles; (2) nonobservational studies, such as animal testing and intervention experiment; (3) correlation coefficient, means, or SD could not be acquired to calculate the pooled effect size; (4) the level of vitamin C was measured from urine; and (5) participants used supplements with vitamin C beyond the recommended dietary allowances.

2.3. Quality Assessments

Considering that different types of observational studies were included in our meta-analysis, we used two methodological quality checklists. The first one was the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [30], assessing case-control and cohort studies. The assessment of NOS was performed on the items of the selection of study population, comparability between cases and noncases, exposure, and the outcome, with a maximum score of 9. We regarded the article awarded a score ≥5 as a high-quality assessment, owing to that the standard validated criteria have not been established [31]. Cross-sectional studies were assessed using 11 items recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [32]. These items would be answered with “yes,” “unclear,” and “no,” separately scored with 1 and 0.

2.4. Data Extraction

We extracted the following data to describe the main characters of each study, including the first author's name, publication year, country conducted in, the age of subjects, sample size, BP value, study design, outcomes (correlation coefficient or means and standard), and variables adjusted for.

2.5. Data Conversion

If the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was not provided, the Spearman coefficient (rs) and regression coefficient (b) with standard error (SE) could be used to estimate the r value [33]. Details are as follows:

r was calculated if rs was available:

| (1) |

(2) r was calculated if b was available:

“SEb” is the standard error of b, so

| (2) |

We performed Fisher's Z transformation to convert every correlation coefficient to an approximately normal distribution, and then the pooled effect size was weighted with the inverse variance. Fisher's Z transformation was according to the following formulates [34]:

| (3) |

where Z stands for the value of summary Fisher's Z.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The mean difference (MD) was applied for continuous variables in case-control studies (or cross-sectional studies) while Fisher's Z value was applied for correlation coefficients to calculate the pooled effect size; for both, the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were available and the forest plots were used to display the results graphically. Subgroup analyses were performed by sex, with or without hypertension, antihypertensive drugs, level of vitamins A and E, study area, and sample size. All the statistical analysis was conducted with the Reviewer Manager (RevMan) 5.3 software.

Heterogeneity was detected by Q-statistics, derived from the Chi-squared test and I-squared (inconsistency). Notable heterogeneity was indicated when the P value was below 0.05 or an I2 value was above 50%, and in this case, a random-effects model was preferred. Then, a sensitivity analysis would be performed to investigate the potential sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was visually assessed with the funnel plot, and Begg's test and Egger's test could also be applied with the Stata 14.0 software when necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

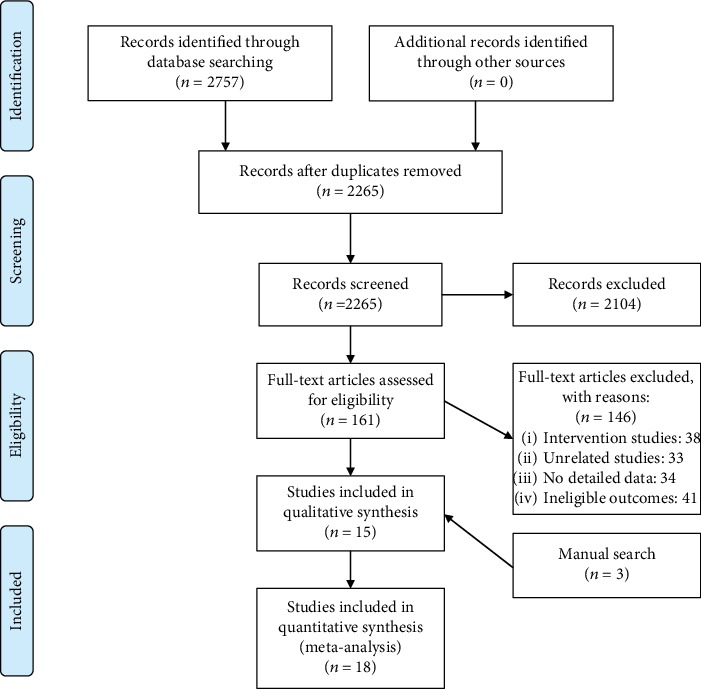

A total of 2757 articles were searched from English and Chinese databases. There were 2104 articles excluded by screening the titles and abstracts, and finally, 18 eligible articles [35–52] were included in our meta-analysis based on full-text review and manual search. The study selection procedure is outlined in Figure 1

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics and Quality

As shown in Table 1, the selected articles included 11 cross-sectional studies and 7 case-control studies. These studies comprised 22200 observational subjects and were conducted from the year 1990 to 2017. Of the 18 articles, 14 were published in the English language, and 4 were in Chinese.

Table 1.

The characters and the quality assessment of included studies.

| First author | Year | Study area | Sample size | Age | BP value | Study design | Outcome | Adjusted variable | Quality score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Overall | (SBP/DBP) | ||||||||

| Zhao | 1990 | China | NA | NA | 416 | 40-59 | NA | Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | / | 5 |

| Moran | 1993 | USA | 60 | 108 | 168 | 19-70 | 111.6 ± 0.9/72.3 ± 0.7 | Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | / | 6 |

| Tse | 1994 | UK | 39 | 34 | 73 | C: 59.6 ± 11.7 N: 51.8 ± 12.3 |

C: 181 ± 27/98 ± 13 N: 125 ± 15/76 ± 9 |

Case-control | M ± SD Regression coefficient |

Age, sex, smoking | 7 |

| Wen | 1996 | Ireland | 32 | 27 | 59 | C: 58.3 ± 19.5 N: 50.6 ± 12.7 |

NA | Case-control | M ± SD | / | 7 |

| Toohey | 1996 | USA | 42 | 126 | 168 | F: 49.0 ± 1.4 M: 44.5 ± 2.1 |

F: 118.8 ± 1.7/77.2 ± 0.9 M: 121.0 ± 3.3/79.0 ± 1.7 |

Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | / | 4 |

| Ness | 1996 | UK | 835 | 1025 | 1860 | 45-75 | 135.8 ± 18.5/82.5 ± 11.3 | Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient Regression coefficient |

Age, sex and BMI | 4 |

| Pierdomenico | 1998 | Italy | NA | NA | 42 | C: 46 ± 6 N: 47 ± 6 |

C: 148 ± 11/96 ± 4 N: 122 ± 4/76 ± 4 |

Case-control | M ± SD | / | 7 |

| Sakai | 1998 | Japan | 919 | 1266 | 2185 | ≥40 | F: 128.3 ± 20.8/75.8 ± 11.4 M: 134.0 ± 20.0/81.0 ± 11.7 |

Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, physical activity | 5 |

| Bates | 1998 | UK | NA | NA | 541 | ≥65 | 152.1 ± 23.2/78.2 ± 13.1 | Cross-sectional | Regression correlation | / | 4 |

| Tang | 1998 | China | NA | NA | 84 | 30-60 | NA | Case-control | Correlation coefficient | / | 6 |

| Sherman | 2000 | USA | 31 | 21 | 52 | C: 49 ± 12 N: 5 ± 11 |

NA | Case-control | M ± SD | / | 8 |

| Langlois | 2001 | Belgium | 96 | 123 | 219 | 69 ± 9 | C: 147 ± 15/91 ± 12 N: 126 ± 10/75 ± 8 |

Case-control | M ± SD | / | 7 |

| Chen | 2002 | USA | NA | NA | 15317 | ≥20 | C: 144.8 ± 0.49/81.4 ± 0.31 N: 115.6 ± 0.18/71.9 ± 0.18 |

Cross-sectional | M ± SE OR |

Age, sex, race, education, alcohol, BMI | 7 |

| Chen | 2004 | China | 28 | 72 | 100 | 19-40 | NA | Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | / | 4 |

| Rodrigo | 2007 | Chile | 66 | / | 66 | 35-60 | C: 137.5 ± 0.2/91.9 ± 1.3 N: 119.5 ± 0.8/78.2 ± 0.8 |

Cross-sectional | M ± SD Correlation coefficient |

/ | 5 |

| Kumar | 2014 | Malaysia | NA | NA | 690 | 56-64 | C: 143.57 ± 11.31/91.87 ± 8.77 N: 119.71 ± 5.67/76.78 ± 4.62 |

Case-control | M ± SD | / | 8 |

| Zhou | 2014 | China | 28 | 72 | 100 | 19-40 | NA | Cross-sectional | Correlation coefficient | / | 5 |

| Naregal | 2017 | India | NA | NA | 60 | 60-80 | C: 146.03 ± 11.37/75.33 ± 5.21 N: 113.76 ± 3.18/71.70 ± 5.17 |

Cross-sectional | M ± SD Correlation coefficient |

/ | 5 |

C: case, N: non-case, F: female, M: male, M: mean, SD: standard deviation, SE: standard error, OR: odds ratio.

Assessed with NOS, all the case-control studies yield a high quality averaging with 7.143 scores. And the result of AHRQ indicates a moderate quality with all cross-sectional studies scoring between 4 and 7.

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Outcome

3.3.1. Serum Vitamin C Concentration

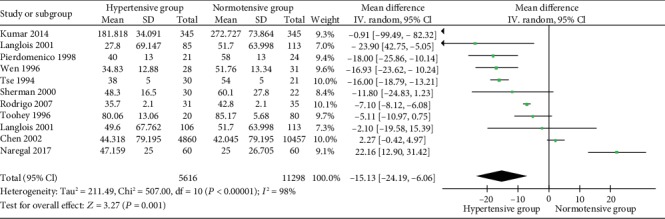

The level of serum vitamin C between hypertensive subjects and normotensives is described in Figure 2, which involved 10 studies composing of 16914 participants [37, 40, 43–46, 50]. Owing to high heterogeneity (Cochrane Q test = 507.00, degrees of freedom (df) = 10, P < 0.00001, I2 = 98%), the analysis was conducted on the random-effects model. It was obvious that the serum level of vitamin C of hypertensive subjects was 15.13 μmol/L lower than the normotensives (MD = −15.13, 95% CI [-24.19, -6.06], P = 0.001).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of serum vitamin C concentration in hypertensive and normotensive subjects.

Due to the high heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was conducted, in which one single study was omitted at a time while the others were recalculated to estimate if the result could affect markedly. We found that the average level of vitamin C concentration in Kumar's study [50] was several times higher than the others, which might indicate to some mistakes in raw data. It was additionally found that vitamin C intake between the groups was significantly different. The I2 value reduced from 98% to 94% after removing this study, whereas it remained stable after omitting other studies. A subgroup analysis was subsequently performed, revealing that hypertensive subjects who took antihypertensive drugs had a 15.97 μmol/L lower serum vitamin C compared with normotensive ones. And no obvious heterogeneity was found.

3.3.2. The Correlation between Vitamin C and Blood Pressure

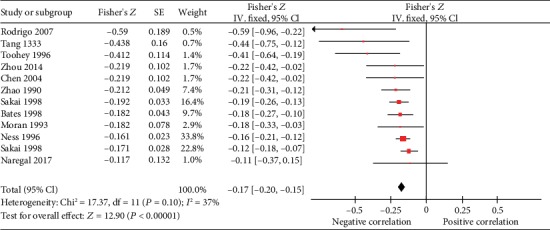

(1) Systolic Blood Pressure. The correlation between serum vitamin C and the systolic blood pressure (SBP) was described in 12 studies, 1 of which was excluded in our meta-analysis for the missing value of SE [47]. As illustrated in Figure 3 the analysis was conducted with fixed-effects model due to a low heterogeneity (Cochrane Q test = 17.37, df = 11, P = 0.10, I2 = 37%). The pooled Fisher's Z was -0.17 (Fisher′s Z = −0.17, 95% CI [-0.20, -0.15], P < 0.00001), indicating a reverse relation between serum vitamin C concentration and SBP significantly. And the summary r value was -0.168 calculated with the formula above.

Figure 3.

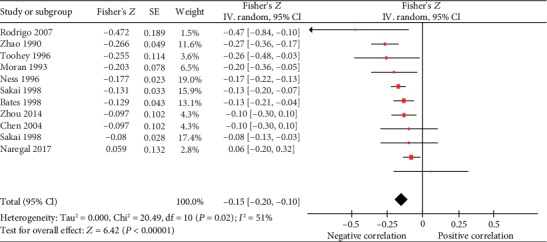

(2) Diastolic Blood Pressure. By conducting on a random-effects model, serum vitamin C concentration was inversely correlated to diastolic blood pressure (DBP) with Fisher's Z value of -0.15 (Fisher′s Z = −0.15, 95% CI [-0.20, -0.10], P < 0.00001). The summary r was -0.149, and there was a moderate heterogeneity (Cochrane Q test = 20.49, df = 10, P = 0.02, I2 = 51%) (Figure 4

Figure 4.

(3) Subgroup Analysis. Reflected in Table 2, the subgroup analyses of the association between plasma vitamin C and blood pressure were carried out based on gender, with or without hypertension, antihypertensive drugs, level of vitamins A and E, study areas, and the sample size. Results of all subgroups revealed that serum vitamin C was negatively correlated to SBP and DBP, with significance. In the analysis of SBP, the heterogeneity in each subgroup was not quite high, except for male subjects (Cochrane Q test = 12.39, df = 5, P = 0.03, I2 = 60%) and hypertensive subjects (Cochrane Q test = 7.00, df = 1, P = 0.008, I2 = 86%). In the analysis of DBP, there was an obvious heterogeneity in male (Cochrane Q test = 14.24, df = 5, P = 0.01, I2 = 65%), female (Cochrane Q test = 3.76, df = 1, P = 0.05, I2 = 73%), and studies in Asia area (Cochrane Q test = 12.96, df = 5, P = 0.02, I2 = 61%).

Table 2.

The outcomes of subgroup analysis and adjustment of confounders.

| Subgroups | SBP | DBP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (n) | Fisher's Z | 95% CI | I 2 (%) | P h | Studies (n) | Fisher's Z | 95% CI | I 2 (%) | P h | ||

| All studies | 11 | -0.17 | (-0.20, -0.15) | 37 | 0.10 | 10 | -0.15 | (-0.20, -0.10) | 51 | 0.02 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Sex | Male | 5 | -0.20 | (-0.28, -0.12) | 60 | 0.03 | 6 | -0.15 | (-0.24, -0.06) | 65 | 0.01 |

| Female | 2 | -0.13 | (-0.17, -0.09) | 0 | 0.63 | 2 | -0.12 | (-0.20, -0.04) | 73 | 0.05 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Hypertension | Yes | 2 | -0.16 | (-0.36,0.03) | 86 | 0.008 | 2 | -0.23 | (-0.42, -0.03) | 57 | 0.13 |

| No | 6 | -0.24 | (-0.32, -0.17) | 0 | 0.54 | 5 | -0.20 | (-0.28, -0.13) | 11 | 0.34 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Antihypertensive drugs | Unclear | 4 | -0.15 | (-0.18, -0.12) | 18 | 0.30 | 4 | -0.10 | (-0.14, -0.06) | 0 | 0.69 |

| No | 7 | -0.22 | (-0.27, -0.16) | 14 | 0.32 | 7 | -0.17 | (-0.23, -0.12) | 35 | 0.16 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Level of vitamin A and vitamin E | Normal | 2 | -0.53 | (-0.79, -0.28) | 0 | 0.69 | 2 | -0.26 | (-0.51, -0.00) | 59 | 0.12 |

| Abnormal | 3 | -0.19 | (-0.25, -0.13) | 45 | 0.16 | 3 | -0.18 | (-0.24, -0.12) | 57 | 0.10 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Area | America | 3 | -0.31 | (-0.42, -0.20) | 55 | 0.08 | 3 | -0.23 | (-0.34, -0.11) | 0 | 0.45 |

| Europe | 2 | -0.17 | (-0.21, -0.13) | 0 | 0.67 | 2 | -0.16 | (-0.20, -0.12) | 0 | 0.38 | |

| Asia | 6 | -0.17 | (-0.20, -0.13) | 22 | 0.26 | 5 | -0.13 | (-0.20, -0.05) | 61 | 0.02 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Sample size | <100 | 4 | -0.37 | (-0.50, -0.25) | 32 | 0.21 | 3 | -0.16 | (-0.30, -0.02) | 53 | 0.09 |

| 100-500 | 4 | -0.21 | (-0.28, -0.14) | 0 | 0.99 | 4 | -0.21 | (-0.28, -0.14) | 20 | 0.29 | |

| >500 | 3 | -0.16 | (-0.19, -0.13) | 4 | 0.37 | 3 | -0.13 | (-0.16, -0.10) | 54 | 0.09 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Adjusted Confounders | |||||||||||

| Age | Male | 2 | -0.12 | (-0.17, -0.07) | 75 | 0.04 | 2 | -0.12 | (-0.16, -0.07) | 51 | 0.15 |

| Female | 2 | -0.10 | (-0.14, -0.06) | 14 | 0.28 | 2 | -0.09 | (-0.14, -0.05) | 46 | 0.17 | |

| Age+sex | 2 | -0.11 | (-0.14, -0.08) | 0 | 0.65 | 2 | -0.11 | (-0.14, -0.08) | 0 | 0.85 | |

| Age+BMI | Male | 2 | -0.11 | (-0.16, -0.07) | 78 | 0.03 | 2 | -0.10 | (-0.15, -0.06) | 67 | 0.08 |

| Female | 2 | -0.09 | (-0.13, -0.04) | 0 | 0.52 | 2 | -0.09 | (-0.13, -0.05) | 6 | 0.30 | |

| Age+sex+BMI | 2 | -0.09 | (-0.12, -0.06) | 0 | 0.50 | 2 | -0.10 | (-0.13, -0.07) | 0 | 0.72 | |

P h: P value of heterogeneity.

(4) Adjustment of Main Confounders. Two studies [38, 41] provided correlation coefficients adjusting for potential factors. After adjustment for the confounders of age, sex, and body mass index (BMI), the association remained the same. As displayed in Table 2, there was a significant negative correlation between serum vitamin C and SBP with low or moderate heterogeneity, except for male adjusted with age or age and BMI. The association between DBP and plasma vitamin C were inverse and stable after adjustment for confounders.

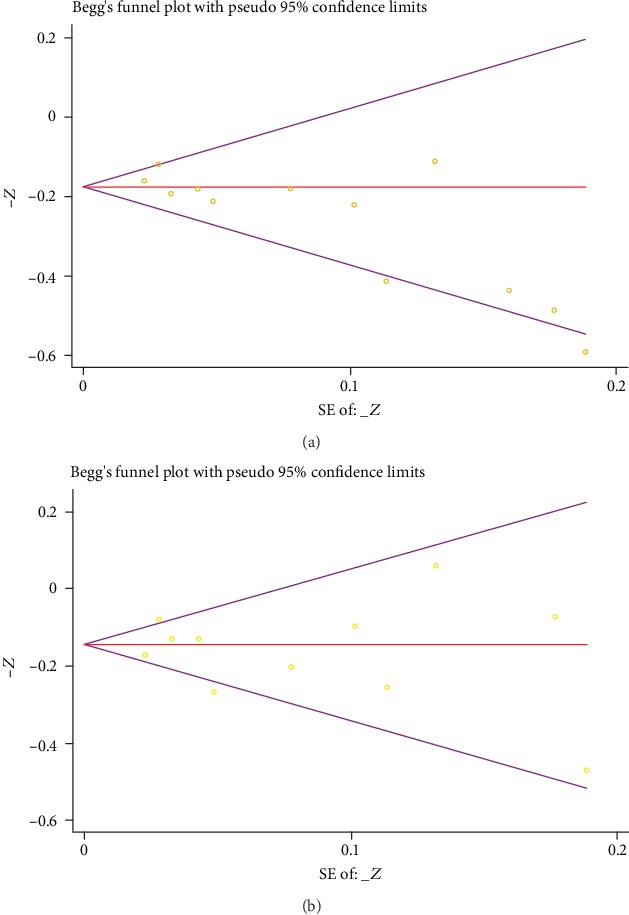

3.4. Publication Bias

The funnel plot in the comparison of plasma vitamin C and SBP is suggestive of publication bias, and thus, we conducted Begg's test and Egger's test after that. Summarized in Figure 5(a), the results of Begg's test (P = 0.015) and Egger's test (P = 0.003) showed notable evidence of publication bias. But in the comparison of plasma vitamin C and DBP, the results of Begg's test (P = 0.819) and Egger's test (P = 0.725), as well as a funnel plot, manifested no distinctive publication bias (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have observed an elevation of plasma marker of oxidative stress in the elderly hypertensive subjects, suggesting that oxidative stress may be the mechanism of hypertension. For this reason, antioxidants prevent free radicals from oxidizing or reduce free radical formation, thus, protecting cell membrane pumps from oxidative damage, which might be the reason and evidence for using it in treating hypertension. As a result, vitamin C, the most effective water-soluble antioxidant in human plasma, is regarded to have a protective role against hypertension disease and CVDs [53].

On the bases of free radical theory, researchers demonstrated that ascorbic-free radicals are first formed and then converted to dehydroascorbic acids and semidehydroascorbic acids, scavenging highly reactive free radicals and oxides, including superoxide anions (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH·), organic free radicals (R·), and peroxy radical (ROO·). Therefore, vitamin C may bring vascular endothelial cells injured by oxidization into a reduced state to recover their functionality and keep the vessels pliable [54, 55]. Apart from this, the oxidation resistance of vitamin C may also manifest itself in the facilitation of glutathione (GSH) synthesis, while both the reduction of GSH and the decreased activity of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) would probably trigger hypertension [56, 57]. Currently, studies observed a relatively lower concentration in hypertensive subjects, and the results of our meta-analysis confirmed it. Just as our results exhibited, the mean serum vitamin C level of hypertension was 15.13 μmol/L lower compared to nonhypertensions. Additionally, both the hypertensive and the normotensive subjects have a significant inverse correlation to SBP and DBP.

Even though vitamin C has an antihypertensive effect by decreasing oxidative stress and improving vascular endothelial function, there is still no validated conclusion from it. Yet, several limitations and weaknesses in our research findings were aroused, which would be a research field or main concerns in the future.

First of all, there is an obvious individual difference. This difference is embodied in two aspects: serum vitamin C concentration and correlation coefficient. To be specific, hypertensives' serum vitamin C ranges from 27.800 ± 69.147 μmol/L to 181.818 ± 34.091 μmol/L, while normotensives' ranges from 25.000 ± 26.705 μmol/L to 272.727 ± 73.864 μmol/L. Besides, the r value of SBP is from -0.53 to -0.016, while DBP's r value is between -0.269 and 0.059. We speculated this difference may come from the age or the individual differences in population; therefore, subgroup analysis of age and race should be conducted if provided in original studies.

In the next place, causal associations between plasma vitamin C and BP cannot be inferred, because all the studies included in our meta-analysis are case-control and cross-sectional studies. What is more, the association is not very strong. The summary r value between serum vitamin C and DBP was -0.149. In terms of our included literature, serum vitamin C presents a weak correlation to SBP with a comprehensive r value of -0.168, whereas DBP showed a correlation of -0.149. And it is notable that the correlation to SBP in hypertensive ones is insignificant (Fisher′s Z = −0.16, 95% CI [-0.36, 0.03], P = 0.10).

Last, due to the heterogeneity and publication bias existing in our meta-analysis, we should be more cautious before jumping to any conclusion. In the evaluation of serum vitamin C, despite a lower concentration was identified in hypertensive subjects, there is a high heterogeneity. Through the subgroup analysis, all hypertensive subjects sticking with antihypertensive drugs consistently showed much lower serum vitamin C (15.97 μmol/L), whereas those who did not take drugs showed high heterogeneity. We speculated that antihypertensive drugs might consume serum vitamin C. It was additionally found that the serum level of vitamins A and E did not cause the heterogeneity mainly, and it was similar in the correlation analysis. Hence, after comprehensively considering the heterogeneity and publication bias, the results are more stable in females, nonhypertensives, or hypertensives taking antihypertensive drugs, but it calls for more original studies to verify.

For all mentioned above, more details should be considered in further studies. On one hand, prospective studies with high qualities are required to link vitamin C deficiency to the risk of HBP; on the other, a meta-analysis should be conducted on the relation between vitamin C intake and hypertension.

5. Conclusion

Hypertensives are exposed in a lower serum vitamin C concentration. Serum vitamin C generally shows a negative relation to SBP and DBP.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Construction Project of the Cultivate Discipline of Chinese Preventive Medicine of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2012 (170)) and the Key Project of the Comprehensive Investment in Food Hygiene and Nutrition of the Tianjin 13th Five-Year Plan. The authors thank Dr. Bin Wang for assistance with data extraction.

Abbreviations

- CVDs:

Cardiovascular diseases

- BP:

Blood pressure

- PubMed:

National Library of Medicine

- WOS:

Web of Science

- CNKI:

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- MOOSE:

Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies

- SD:

Standard deviations

- NOS:

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- AHRQ:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- SE:

Standard error

- MD:

Mean difference

- CI:

Confidence intervals

- RevMan:

Reviewer Manager

- SBP:

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

Diastolic blood pressure

- BMI:

Body mass index

- AA:

Ascorbic acid

- GSH:

Glutathione

- GSH-Px:

Glutathione peroxidase.

Contributor Information

Ye Zhao, Email: zakzy@163.com.

Huaien Bu, Email: huaienbu@tjutcm.edu.cn.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and concept, performed the literature searches, wrote the manuscript and critiqued the successive versions, and approved the final manuscript. HEB coordinated the effort and integrated the sections and comments. Li Ran and Wenli Zhao contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Whelton P. K. Epidemiology of hypertension. British Medical Journal. 1952;1(4765):962–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S., Reddy S., Ounpuu S., Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2746–2753. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iburg K. M. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W., Hu S. S., Kong L. Z., et al. Summary of report on cardiovascular diseases in China, 2012. Biomedical and environmental sciences. 2014;27(7):552–558. doi: 10.3967/bes2014.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xi B., Liu F., Hao Y., Dong H., Mi J. The growing burden of cardiovascular diseases in China. International Journal of Cardiology. 2014;174(3):736–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhakaran D., Jeemon P., Roy A. Cardiovascular diseases in India: current epidemiology and future directions. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1605–1620. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagard R. H. Epidemiology of hypertension in the elderly. The American Journal of Geriatric Cardiology. 2007;11(1):23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2002.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendis S., Puska P., Norrving B., Mendis S., Puska P., Norrving B. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens S. L., Wood S., Koshiaris C., et al. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:p. i4098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kathiresan S., Srivastava D. Genetics of human cardiovascular disease. Cell. 2012;148(6):1242–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikpay M., Goel A., Won H. H., et al. A comprehensive 1000 genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nature Genetics. 2015;47(10):1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedlander Y., Kark J. D., Stein Y. Family history of myocardial infarction as an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. Heart. 1985;53(4):382–387. doi: 10.1136/hrt.53.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guanglin W., Huimin Y., Xiuying Q., Zhenlin J. A case-control for the association between change in weight, family history and hypertension at different ages. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2001;13(2):96–99. doi: 10.1177/101053950101300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tozawa M., Oshiro S., Iseki C., et al. Family history of hypertension and blood pressure in a screened cohort. Hypertension Research. 2001;24(2):93–98. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niskanen L., Laaksonen D. E., Nyyssönen K., et al. Inflammation, abdominal obesity, and smoking as predictors of hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;44(6):859–865. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000146691.51307.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caspersen C. J., Bloemberg B. P. M., Saris W. H. M., Merritt R. K., Kromhout D. The prevalence of selected physical activities and their relation with coronary heart disease risk factors in elderly men: the Zutphen study, 1985. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;133(11):1078–1092. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson R. L., Margetts B. M., Wood D. A., Jackson A. A. Cigarette smoking and food and nutrient intakes in relation to coronary heart disease. Nutrition Research Reviews. 1992;5(1):131–152. doi: 10.1079/NRR19920011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowman T. S., Gaziano J. M., Buring J. E., Sesso H. D. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of incident hypertension in women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(21):2085–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu G., Barengo N. C., Tuomilehto J., Lakka T. A., Nissinen A., Jousilahti P. Relationship of physical activity and body mass index to the risk of hypertension: a prospective study in Finland. Hypertension. 2004;43(1):25–30. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000107400.72456.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernard K. S., Wolf K. N., Wexler R. K., Taylor C. A. Differences in dietary intake habits of African American adults by hypertension status. Topics in Clinical Nutrition. 2011;26(1):34–44. doi: 10.1097/TIN.0b013e318209e34b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joffres M. R., Reed D. M., Yano K. Relationship of magnesium intake and other dietary factors to blood pressure: the Honolulu heart study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;45(2):469–475. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajjar I. M., Grim C. E., George V., Kotchen T. A. Impact of diet on blood pressure and age-related changes in blood pressure in the US population: analysis of NHANES III. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(4):589–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness A. R., Chee D., Elliott P. Vitamin C and blood pressure–an overview. Journal of Human Hypertension. 1997;11(6):343–350. doi: 10.1.38/sj.jhh.1000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh S. K., Ekpo E. B., Shah I. U., Girling A. J., Jenkins C., Sinclair A. J. A double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel trial of vitamin C treatment in elderly patients with hypertension. Gerontology. 2004;40(5):268–272. doi: 10.1159/000213595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamran A., Shekarchi A. A., Sharifian E., Heydari H. The comparison of dietary behaviors among rural controlled and uncontrolled hypertensive patients. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2016;2016:7. doi: 10.1155/2016/7086418.7086418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshioka M., Matsushita T., Chuman Y. Inverse association of serum ascorbic acid level and blood pressure or rate of hypertension in male adults aged 30-39 years. International Journal for Vitamin & Nutrition Research. 1998;54(4):343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar K. V., Das U. N. Are free radicals involved in the pathobiology of human essential hypertension? Free Radical Research Communications. 1993;19(1):59–66. doi: 10.3109/10715769309056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duthie S. J., Duthie G. G., Russell W. R., et al. Effect of increasing fruit and vegetable intake by dietary intervention on nutritional biomarkers and attitudes to dietary change: a randomised trial. European Journal of Nutrition. 2018;57(5):1855–1872. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroup D. F., Berlin J. A., Morton S. C., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in Epidemiology. A proposal for Reporting. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ownby R. L., Crocco E., Acevedo A., John V., Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer Disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):p. 530. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cemal Y., Jewell S., Albornoz C. R., Pusic A., Mehrara B. J. Systematic review of quality of life and patient reported outcomes in patients with oncologic related lower extremity lymphedema. Lymphatic Research and Biology. 2013;11(1):14–19. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2012.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rupinski M. T., Dunlap W. P. Approximating Pearson product-moment correlations from Kendall's tau and Spearman's rho. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1996;56(3):419–429. doi: 10.1177/0013164496056003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao X., Wang H., Li J., Shan Z., Teng W., Teng X. The Correlation between polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and thyroid hormones in the general population: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):p. e0126989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guangsheng Z., Bangqiang G., Xiaoyuan Y., Youwen H., Li W., Meixiang Z. The relationship between plasma vitamin A, E, C and blood pressure in five populations in China. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science) 1990;10(2):106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran J. P., Cohen L., Greene J. M., et al. Plasma ascorbic acid concentrations relate inversely to blood pressure in human subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1993;57(2):213–217. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse W. Y., Maxwell S. R., Thomason H., et al. Antioxidant status in controlled and uncontrolled hypertension and its relationship to endothelial damage. Journal of Human Hypertension. 1994;8(11):843–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ness A. R., Khaw K. T., Bingham S., Day N. E. Vitamin C status and blood pressure. Journal of Hypertension. 1996;14(4):503–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toohey L., Harris M. A., Allen K. G. D., Melby C. L. Plasma ascorbic acid concentrations are related to cardiovascular risk factors in African-Americans. The Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126(1):121–128. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen Y., Killalea S., McGettigan P., Feely J. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant vitamins C and E in hypertensive patients. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 1996;165(3):210–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02940252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakai N., Yokoyama T., Date C., Yoshiike N., Matsumura Y. An inverse relationship between serum vitamin C and blood pressure in a Japanese community. Journal Of Nutritional Science And Vitaminology. 1998;44(6):853–867. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.44.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates C. J., Walmsley C. M., Prentice A., Finch S. Does vitamin C reduce blood pressure? Results of a large study of people aged 65 or older. Journal of Hypertension. 1998;16(7):925–932. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiaowu T., Wanchun Y., Lianzi C. Preliminary study on the effects of vitamin C on blood pressure. Chinese Journal of Disease Control and Prevention. 1998;2(3) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierdomenico S. D., Costantini F., Bucci A., De Cesare D., Cuccurullo F., Mezzetti A. Low-density lipoprotein oxidation and vitamins E and C in sustained and white-coat hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;31(2):621–626. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.31.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherman D. L., Keaney J. F., Jr., Biegelsen E. S., Duffy S. J., Coffman J. D., Vita J. A. Pharmacological concentrations of ascorbic acid are required for the beneficial effect on endothelial vasomotor function in hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35(4):936–941. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.4.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langlois M., Duprez D., Delanghe J., De Buyzere M., Clement D. L. Serum vitamin C concentration is low in peripheral arterial disease and is associated with inflammation and severity of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1863–1868. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.14.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J., He J., Hamm L., Batuman V., Whelton P. K. Serum antioxidant vitamins and blood pressure in the United States population. Hypertension. 2002;40(6):810–816. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000039962.68332.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhaochang C., Hongxia Y. Correlation between serum vitamin C level and blood pressure. Chinese Primary Health Care. 2004;18(3) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodrigo R., Prat H., Passalacqua W., Araya J., Guichard C., Bachler J. P. Relationship between oxidative stress and essential hypertension. Hypertension Research. 2007;30(12):1159–1167. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar A. Correlation between anthropometric measurement, lipid profile, dietary vitamins, serum antioxidants, lipoprotein (a) and lipid peroxides in known cases of 345 elderly hypertensive South Asian aged 56–64 y–A hospital based study. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2014;4(Supplement 1):S189–S197. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014D153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yunmei Z. Correlation between serum vitamin C level and blood pressure. China Hwalth Care & nutrition. 2014;24(3):p. 1287. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naregal G. V. Elevation of oxidative stress and decline in endogenous antioxidant defense in elderly individuals with hypertension. Journal of Clinical And Diagnostic Research. 2017;11(7):C9–C12. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2017/27931.10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ran L., Zhao W., Wang J., et al. Extra dose of vitamin C based on a daily supplementation shortens the common cold: a meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:12. doi: 10.1155/2018/1837634.1837634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 54.Padayatty S. J., Katz A., Wang Y., et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention. Journal of The American College of Nutrition. 2003;22(1):18–35. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhalla N. S., Temsah R. M., Netticadan T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Hypertension. 2000;18(6):655–673. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MB M., DM A., IB J., Pesut O. J., DP M., Stojanov V. J. Blood and plasma selenium levels and GSH-Px activities in patients with arterial hypertension and chronic heart disease. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology. 1998;17(3-4):285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ji S., Xu H., Wang Y., Qin J. Clinical significance of changes of serum SOD, LPO and GSH-PX levels in patients with hypertension. Journal of Radioimmunology. 2004;17:261–262. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.