Abstract

Here, we use 30 long-term, high-resolution palaeoecological records from Mexico, Central and South America to address two hypotheses regarding possible drivers of resilience in tropical forests as measured in terms of recovery rates from previous disturbances. First, we hypothesize that faster recovery rates are associated with regions of higher biodiversity, as suggested by the insurance hypothesis. And second, that resilience is due to intrinsic abiotic factors that are location specific, thus regions presently displaying resilience in terms of persistence to current climatic disturbances should also show higher recovery rates in the past. To test these hypotheses, we applied a threshold approach to identify past disturbances to forests within each sequence. We then compared the recovery rates to these events with pollen richness before the event. We also compared recovery rates of each site with a measure of present resilience in the region as demonstrated by measuring global vegetation persistence to climatic perturbations using satellite imagery. Preliminary results indeed show a positive relationship between pre-disturbance taxonomic richness and faster recovery rates. However, there is less evidence to support the concept that resilience is intrinsic to a region; patterns of resilience apparent in ecosystems presently are not necessarily conservative through time.

Keywords: resilience, palaeoecology, forest, Neotropics, disturbance, pollen

1. Background

In the present context of global change, where ecosystems are likely to be exposed to an increase in disturbances [1], a knowledge of the factors that make ecosystems resilient has become increasingly important. Such knowledge is critical for determining landscapes that may be better able to withstand climate change and other environmental disturbances, especially in forested systems, which provide many important ecosystem services [2]. There are two forms of resilience to consider: the first known as ecological resilience [3,4], measured by recovery rates from a disturbance event and calculated in this manuscript, and the second being engineering resilience or persistence [5], referring to how long an ecosystem can withstand a disturbance before changing to an alternative state.

To date, several palaeoecological studies have addressed ecological resilience [6–9], but these have tended to only look at one individual system, and few have attempted regional syntheses to address specific hypotheses regarding the nature and underlying drivers of resilience [6]. In this study, we examined records from 30 high-resolution palaeoecological datasets across Neotropical forest ecosystems. The sites showed evidence of one or more past forest disturbance events, such as fire, hurricanes or anthropogenic impacts, as well as displaying spatial variation in recovery rates to these events. Using these records, we address two hypotheses related to resilience [3]. First, the insurance hypothesis [10], which states that more diverse ecosystems have greater resilience. Second, the hypothesis that resilience is due to a combination of location-specific abiotic factors [11], and thus some locations demonstrate a constancy of resilience through time due to these abiotic features.

2. Methods

(a). Identifying disturbance events

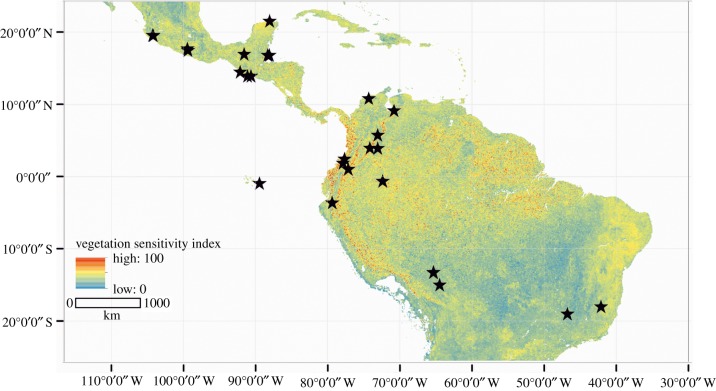

We selected high resolution, well-dated palaeoecological datasets from the Neotropics ([12] figure 1 and table 1) covering the time period from the Late Glacial to the present (i.e. from 13 000 calibrated years before present (cal yr BP)) and spanning a large gradient in vegetation persistence as measured by the vegetation sensitivity index (VSI, [13]). The different forest types under analysis include pine, tropical dry deciduous, tropical semi-deciduous, Andean, Subpáramo, montane, gallery, cloud and rain forests (table 1). To objectively identify disturbance events for each sequence, we applied a threshold method based on the percentage of the sum of pollen from forest taxa per pollen assemblage zone (PAZ). To achieve this, first, the counts of pollen grains per sample belonging to all terrestrial taxa were square-root transformed [39] and hierarchically clustered through time to determine statistically significant PAZs [40] of the pollen sequences. These analyses were done by using the Rioja package [41] in the R software [42]. For each sequence, percentages of the pollen taxa from the main forest type present within the sequence were summed together. Within each PAZ, mean and standard deviation for the sum of percentages of the forest taxa were calculated. Disturbance events within the sequences were defined as: (1) having a forest percentage sum of less than the mean minus one standard deviation per PAZ (i.e. <μ − 1σ, where μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation), making this our threshold value to identify disturbances, (2) displaying more than one sample within a disturbance event, (3) recording a clear start and end of the disturbance event within the sequence and (4) having a mean temporal resolution below 100 years (see details in electronic supplementary material, S1 and S2). The second criterion was added to reduce the probability of counting stochastic variations in pollen percentage sums as a disturbance event, while clear starting and ending points in criterion 3 refer to local maxima in the arboreal sum before and after disturbance [6].

Figure 1.

Distribution of study sites (black stars) in Mexico, Central and South America. Sites are displayed on top of a map with the current vegetation sensitivity index (VSI) as identified by Seddon et al. [12].

Table 1.

Study site details in latitudinal order from North to South.

| publication | site | lon | lat | altitude (m.a.s.l.) | forest type | number of disturbances per site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aragon-Moreno et al. [14] | Ria Lagartos | −88.07 | 21.58 | 2 | tropical forest with mangroves | 2 |

| Figueroa-Rangel et al. [15] | transitional forest | −104.23 | 19.59 | 1894 | pine–oak dominated forest | 1 |

| Figueroa-Rangel et al. [16] | cloud forest | −104.28 | 19.59 | 1858 | cloud forest | 1 |

| Figueroa-Rangel et al. [17] | pine forest | −104.2 | 19.57 | 2374 | pine forest | 2 |

| Berrío et al. [18] | Lake Huitziltepec | −99.47 | 17.75 | 1430 | dry deciduous forest | 3 |

| Berrío et al. [18] | Lake Tixtla | −99.4 | 17.5 | 1400 | dry deciduous forest | 2 |

| Domínguez-Vázquez & Islebe [19] | Naja Lake | −91.59 | 16.99 | 800 | rain forest | 1 |

| Wooller et al. [20] | Twin Cays, TCC2 | −88.1 | 16.83 | 0 | tropical forest with mangroves | 3 |

| Neff et al. [21] | TIL | −92.17 | 14.5 | 0 | tropical forest with mangroves | 2 |

| Larmon [22] | Iztapa | −90.66 | 13.95 | 4 | tropical forest with mangroves | 2 |

| Neff et al. [21] | Sipacate - SIP99E | −91.15 | 13.93 | 0 | tropical forest with mangroves | 2 |

| Velez et al. [23] | Boca de Lopez | −74.33 | 10.85 | 0 | tropical forest with mangroves | 1 |

| Rull et al. [24] | Piedras Blancas | −70.83 | 9.17 | 4080 | subpáramo forest | 1 |

| Gomez et al. [25] | Pantano de Vargas | −73.07 | 5.78 | 2510 | Andean forest | 3 |

| vdHammen & Hooghiemstra [26] | Laguna La Primavera | −74.16 | 3.98 | 3525 | subpáramo forest | 6 |

| Berrío et al. [27] | Laguna Mozambique | −73.05 | 3.96 | 175 | gallery forest | 1 |

| Velez et al. [28] | Laguna El Caimito | −77.69 | 2.45 | 50 | rain forest | 3 |

| Behling et al. [29] | Laguna Piusbi | −77.93 | 1.88 | 100 | rain forest | 1 |

| Epping [30] | Laguna la Cocha | −77.15 | 1.08 | 2780 | Andean forest | 4 |

| González-Carranza et al. [31] | Laguna La Cocha | −77.152 | 1.079 | 2780 | Andean forest | 3 |

| Berrío et al. [32] | Quebrada del amor | −72.398 | −0.60 | 242 | rain forest | 1 |

| Restrepo et al. [33] | El Junco | −89.48 | −0.895 | 679 | montane forest | 8 |

| Adolf et al. [34] | Laguna Vendada | −79.39 | −3.61 | 3640 | subpáramo forest | 1 |

| Whitney et al. [35] | Laguna La Frontera | −65.35 | −13.23 | 135 | gallery forest | 1 |

| Whitney et al. [35] | Laguna El Cerrito | −65.38 | −13.25 | 140 | gallery forest | 1 |

| Whitney et al. [36] | Laguna San José | −64.5 | −14.95 | 162 | gallery forest | 1 |

| Enters et al. [37] | Lago Alexio | −42.12 | −17.99 | 390 | tropical semi-deciduous forest | 1 |

| Leyden et al. [38] | Lagoa Campestre de Salitre | −46.77 | −19.0 | 1016 | tropical semi-deciduous forest | 1 |

In a previous study from the tropics that used recovery rates following disturbance in fossil pollen records to measure resilience [6], the recovery rates were defined as a percentage increase of arboreal pollen abundance per year relative to the pre-disturbance level. We applied this previously published equation [6] (equation (2.1); electronic supplementary material, S2),

| 2.1 |

which uses the following identifiable points within the sequences: the lowest forest percentage within a disturbance (Fmin), the highest forest percentage after recovery (Fmax), the percentage sum prior to the disturbance start (Fpre) and the time of recovery (Trec, i.e. from Fmin to Fmax) in calibrated years before present (cal yr BP). We calculated recovery rates per disturbance and mean recovery rates per study site. In addition, in order to assess whether forests recovered to a similar community assemblage as their pre-disturbance state or to a different assemblage, we calculated squared chord distance coefficients [43] between pre- and post-disturbance samples following the approach of Bennion et al. [44]. Samples with a coefficient of 0 indicate communities that are identical to each other, while those with a coefficient of 2 are completely different. As in [44], we chose the 5th percentile cut-off value of 0.48, below which there is insignificant assemblage change between samples. For more details about dataset selection, chronology, statistics, overall methodology and raw data, please refer to electronic supplementary material, S3 and S4 and [45].

(b). Extracting pollen richness and vegetation sensitivity index for each location and disturbance event

To test the insurance hypothesis, i.e. that more diverse ecosystems have greater resilience, pollen richness, a proxy for vegetation richness [46–49] before each disturbance event was estimated using the counts of pollen belonging to terrestrial taxa and this was compared to recovery rates. We hypothesized that those sites with higher pre-disturbance pollen richness would have faster recovery rates. To reduce the sampling bias that affects richness estimations, which occurs when analysts count different amounts of pollen grains per sample, we performed rarefaction analysis [50] on all sequences by using a minimum pollen sum of 100 grains. We used a generalized linear model with variance weighting by study site to test the relationship between pollen richness and log10(x + 1)-transformed recovery rates. The log transformation was chosen to reduce the effect of outliers [51]. The following variables: richness, latitude, altitude and sample resolution, were included in the initial model and tested for significance and influence on model performance following the Akaike information criterion [52].

To test the abiotic hypothesis, i.e. that resilience is due to a combination of location-specific abiotic factors, we used a linear regression model to test the relationship between spatial patterns in present-day vegetation persistence, as measured by the VSI [13] to recovery rates from the past at the same locations. The VSI quantifies vegetation sensitivity over 14 years (2000–2013) in terms of productivity to solely abiotic factors (i.e. climatic factors such as water availability, air temperature and cloudiness) on a 5 km resolution at the global scale, whereby a high sensitivity value indicates low persistence and vice versa. To link this measure up with longer-term vegetation dynamics as obtained from the fossil pollen sequences extracted from the lake sediments [53], we extracted the VSI value from the point location of the fossil study site from the shapefile version of the VSI by using ArcGIS (v. 10.6), software. We hypothesized that those sites with faster recovery rates in the past also show greater persistence to climatic perturbations from 2000 to 2013. All model calculations were done in the nlme package available in R software [41,54].

3. Results

We analysed 30 sedimentary records from the Neotropics (figure 1) and a total of 59 disturbance events. Three sequences were excluded from further analyses for not meeting the disturbance identification criteria (electronic supplementary material, S1). During the extracted disturbance events, all of these records were sampled at a high temporal resolution, with a mean sample resolution across sequences of one sample every ca 40 years (37.7 ± 27.5 years, electronic supplementary material, S1). This high temporal sample resolution is crucial to ensure that the generational change of trees in these forested environments is captured and to reduce the possibility of missing consequent disturbance events. For example, previous studies have identified that it takes between 30 to over a 1000 years for tropical forests to recover following disturbance [6].

The range of recovery rates (in percentage of forest pollen abundance increase per year relative to the levels prior to disturbance) varied from 0.1 to 24.6 (or 0.04 to 1.41 after log10(x + 1) transformation, electronic supplementary material, S5), while pre-disturbance palynological richness values (RichnessPre) ranged between 3.7 to 25.3 different pollen taxa per sample, being highest close to the equator. The range of VSI included in our study went from 8.1, indicating highest persistence to climatic factors to 55.7, displaying lowest persistence to climatic perturbations (electronic supplementary material S1, table 1).

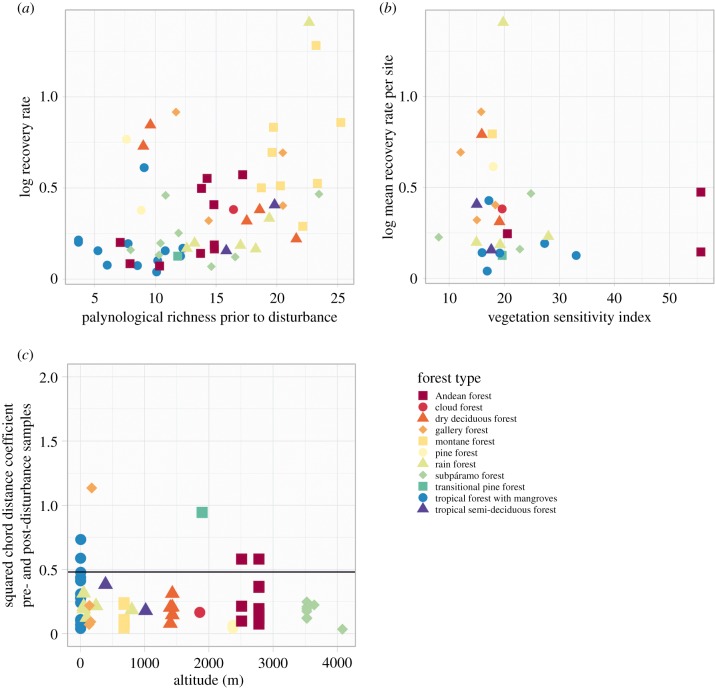

Taking all disturbances together, the variables RichnessPre and the mean temporal resolution of samples within a disturbance (TResolDist) were significant in explaining recovery rates (p-value < 0.001, figure 2a and table 2; electronic supplementary material, S6). This indicates that a high sampling resolution may enable a more accurate detection of forest recovery, while a potential earlier recovery might be missed in records that have a longer time interval between samples. Despite this effect of sampling resolution on the calculated recovery rates, RichnessPre still has a significant positive effect on the calculated recovery rates.

Figure 2.

The relationships describing the two hypotheses to be tested. (a) Palynological richness (number of different pollen taxa per sample), as a proxy for vegetation richness, versus recovery rates (percentage of forest pollen abundance increase per year, relative to pre-disturbance levels, log10(x + 1)-transformed). (b) Vegetation sensitivity index (VSI) versus mean recovery rate (log10(x + 1)-transformed) per each study site. (c) Squared chord distance coefficient measuring similarity between pre- and post-disturbance samples along an altitudinal gradient. The horizontal black line represents the 5th percentile cut-off value of 0.48, below which there is insignificant assemblage change between samples.

Table 2.

Results of generalized least-squares model to test Hypothesis 1. Model equation: log10(RR + 1) ∼ RichnessPre + TResolDist, variance weighted by site (i.e. weights = varIdent(form = ∼1 | site) as used in package ‘nlme’ [54] in the R software); n = 59. RR, recovery rates; RichnesPre, palynological richness per sample prior to disturbance; TResolDist, mean temporal resolution of samples within a disturbance.

| variables | coefficient | standard error | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 0.3467423 | 1.261944 × 10−5 | 27476.85 | <0.001 |

| RichnessPre | 0.0067004 | 5.372250 × 10−7 | 12472.26 | <0.001 |

| TResolDist | −0.0038703 | 8.149000 × 10−8 | −47493.63 | <0.001 |

Regarding our second hypothesis, there is a slightly negative relationship between mean recovery rates per study site (log10(x + 1)-transformed) and VSI at the corresponding sites (figure 2b), which would be in agreement with our second hypothesis. However, VSI was not a significant variable within the linear regression model (table 3).

Table 3.

Results of linear regression model to test Hypothesis 2. Model equation: log10(mRR + 1) ∼ VSI. mRR, mean recovery rates per site; VSI, vegetation sensitivity index.

| variables | coefficient | standard error | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 0.475075 | 0.132312 | 3.591 | 0.00135 |

| VSI | −0.004270 | 0.005505 | −0.776 | 0.44494 |

Our dissimilarity analyses showed that only six of 59 assemblages showed significant change pre- and post-disturbance (figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, S1 and table 1). This indicates that forests seemed to recover to a similar composition as found before the disturbance.

4. Discussion

Our study indicates that within our analysed temporal scale of several thousands of years, resilience properties of a system are generally not location specific and seem not to be associated with the unique set of abiotic factors present. Rather, other factors related to the vegetation assemblage itself, such as biodiversity, appear to be more important.

Previous research has already found a positive effect of biodiversity on the resilience of plant communities, however, most of this research has focused on ecosystems with short generation times (i.e. grasslands, agricultural systems) and on recent timescales [55,56]. To our knowledge, this is the first time this relationship has been demonstrated across the Neotropics through time.

Even though the records chosen in this study have not been sampled continuously, the mean resolution of samples within disturbances (ca 40 years) roughly corresponds to rates of disturbance i.e. from fire in highly fire prone ecosystems (e.g. fire return intervals of 30 years in Mediterranean ecosystems [57]). In our study of tropical forests, the insurance hypothesis [10], stating that more complex systems recover faster from disturbance, is supported by our results, showing the importance of biodiversity to enable forests to recover from disturbances. Our findings are also in agreement with dynamic simulation modelling results of temperate forest ecosystems, which have previously demonstrated that tree diversity positively influences stable forest productivity over time [58]. Possible explanations as to why biodiversity increases ecosystem's resilience include the positive effect of different responses of species to fluctuations, also taking into account different response speeds [58,59] and the fact that there will be a number of species with similar functions thus able to replace the functions of the species lost [10]. Using long-term data from palaeoecological records, as has been done in this study, could provide important further avenues of research into these relationships by looking, for example, at individual taxon traits in those records that demonstrate faster recovery rates.

The lack of a strong relationship between current vegetation persistence patterns at sites and faster recovery rates in the past, may possibly be explained by shifting ecotone boundaries and baselines. Thus, under different climatic conditions in the past, these boundaries have shifted, as can be seen in changing treeline altitudes through time [60], displacing the physical location at which an ecosystem is more sensitive to change. However, we also need to consider the differences in the temporal scale that affect our analyses. We have compared a VSI based on 14 years of data, which in most cases, will not record a single generation of trees, to recovery rates issuing from forest dynamics covering thousands of years and representing multiple generations. Additionally, differences in the pollen source area from large to small lakes and the pixel size of 5 km2 of the VSI data will not always be comparable and smaller-scale abiotic features such as soil type or slope and aspect cannot be reflected on such large pixels. Nevertheless, a result emerging from our study is that the persistence apparent in these ecosystems presently is not necessarily conservative through time. Thus abiotic factors cannot alone be used to explain patterns of resilience; rather our results indicate that pre-disturbance taxonomic diversity is a better indicator of resilience of the system (as measured by recovery rates). This result suggests that conservation management efforts which aim to create resilient ecosystems by maintaining and enhancing biodiversity are a good approach.

5. Conclusion

We have identified biodiversity of forests to be important for their resilience, highlighting the necessity of promoting diverse ecosystems to ensure their provision of ecosystem services in a changing environment. Additionally, further research into which vegetation traits are associated with resilient ecosystems would be an important step towards managing resilient ecosystems for the future, as well as further insights into ecosystem stability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all authors that have made their data available on Neotoma, to Peter Long for his help with the VSI index shapefile, to Dirk Enters for his advice regarding the record of Lago Alexio and to Daniele Colombaroli for sharing parts of his R-code [49] for diversity calculations.

Data accessibility

All R scripts and parts of datasets (details on accessing Neotoma datasets are in the electronic supplementary material) used for analyses are available under: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.xwdbrv19c [45]. Description of the datasets can be found in electronic supplementary material, S7.

Authors' contributions

K.J.W. and C.A. conceived the study and lead the writing process; C.A. performed numerical analyses and wrote the R code with assistance and data-interpretation input from C.T. and N.K., H.B., J.C.B., G.D-.V., B.F.-R., Z.G.-C., G.A.I., H.H., H.N., M.O.-V., B.W. and M.J.W. provided their datasets along with interpretation advice. All authors made important contributions to the final manuscript. All authors agree to be held accountable for the manuscript's content and have approved its final version.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by grant no. P2BEP2_178414 to C.A. by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

- 1.Diaz S, et al. (eds). 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES. See https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/2020-02/ipbes_global_assessment_report_summary_for_policymakers_en.pdf.

- 2.Jeffers ES, Nogué S, Willis K. 2015. The role of palaeoecological records in assessing ecosystem services. Quat. Sci. Rev. 112, 17–32. ( 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.12.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimm SL. 1984. The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 307, 321–326. ( 10.1038/307321a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies AL, Streeter R, Lawson IT, Roucoux KH, Hiles W. 2018. The application of resilience concepts in palaeoecology. Holocene 28, 1523–1534. ( 10.1177/0959683618777077) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holling CS. 1973. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 1–23. ( 10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole LESS, Bhagwat SA, Willis KJK. 2014. Recovery and resilience of tropical forests after disturbance. Nat. Commun. 5, 3906 ( 10.1038/ncomms4906) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gil-Romera G, Lopez-Merino L, Carrion JS, Gonzalez-Samperiz P, Martin-Puertas C, Lopez Saez JA, Fernandez S, Anton MG, Stefanova V. 2010. Interpreting resilience through long-term ecology: potential insights in western Mediterranean landscapes. Open Ecol. J. 3, 43–53. ( 10.2174/1874213001003020043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virah-Sawmy M, Gillson L, Willis KJ. 2009. How does spatial heterogeneity influence resilience to climatic changes? Ecological dynamics in southeast Madagascar. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 557–574. ( 10.1890/08-1210.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrión JS, Andrade A, Bennett KD, Navarro C, Munuera M. 2001. Crossing forest thresholds: inertia and collapse in a Holocene sequence from south-central Spain. Holocene 11, 635–653. ( 10.1191/09596830195672) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yachi S, Loreau M. 1999. Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: the insurance hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1463–1468. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwantes AM, Parolari AJ, Swenson JJ, Johnson DM, Domec JC, Jackson RB, Pelak N, Porporato A. 2018. Accounting for landscape heterogeneity improves spatial predictions of tree vulnerability to drought. New Phytol. 220, 132–146. ( 10.1111/nph.15274) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams J, et al. 2018. The Neotoma Paleoecology Database, a multiproxy, international, community-curated data resource. Quat. Res. 89, 156–177. ( 10.1017/qua.2017.105) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seddon AWRR, Macias-Fauria M, Long PR, Benz D, Willis KKJ. 2016. Sensitivity of global terrestrial ecosystems to climate variability. Nature 531, 229–232. ( 10.1038/nature16986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aragón-Moreno AA, Islebe GA, Torrescano-Valle N. 2012. A ∼3800-yr, high-resolution record of vegetation and climate change on the north coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 178, 35–42. ( 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2012.04.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa-Rangel BL, Willis KJ, Olvera-Vargas M. 2012. Late-Holocene successional dynamics in a transitional forest of west-central Mexico. Holocene 22, 143–153. ( 10.1177/0959683611414929) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figueroa-Rangel BL, Willis KJ, Olvera-Vargas M. 2010. Cloud forest dynamics in the Mexican Neotropics during the last 1300 years. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1689–1704. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02024.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figueroa-Rangel BL, Willis KJ, Olvera-Vargas M. 2008. 4200 years of pine-dominated forest dynamics in the uplands of western-central Mexico: a human or natural legacy? Ecology 89, 1893–1907. ( 10.1890/07-0830.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrío JC, Hooghiemstra H, Van Geel B, Ludlow-Wiechers B.. 2006. Environmental history of the dry forest biome of Guerrero, Mexico, and human impact during the last c. 2700 years. Holocene 16, 63–80. ( 10.1191/0959683606hl905rp) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domínguez-Vázquez G, Islebe GA. 2008. Protracted drought during the late Holocene in the Lacandon rain forest, Mexico. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 17, 327–333. ( 10.1007/s00334-007-0131-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wooller MJ, Morgan R, Fowell S, Behling H, Fogel M. 2007. A multiproxy peat record of Holocene mangrove palaeoecology from Twin Cays, Belize. Holocene 17, 1129–1139. ( 10.1177/0959683607082553) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neff H, Pearsall DM, Jones JG, Arroyo B, Collins SK, Freidel DE. 2006. Early Maya adaptive patterns: mid-late Holocene paleoenvironmental evidence from Pacific Guatemala. Lat. Am. Antiq. 17, 287–315. ( 10.2307/25063054) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larmon JT. 2013. The Pacific coast of Guatemala: a palynological investigation of climate change and human occupation. Master's thesis Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velez MI, Escobar J, Brenner M, Rangel O, Betancourt A, Jaramillo AJ, Curtis JH, Moreno JL. 2014. Middle to late Holocene relative sea level rise, climate variability and environmental change along the Colombian Caribbean coast. Holocene 24, 898–907. ( 10.1177/0959683614534740) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rull V, Salgado-Labouriau ML, Schubert C, Valastro S. 1987. Late holocene temperature depression in the Venezuelan Andes: palynological evidence. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 60, 109–121. ( 10.1016/0031-0182(87)90027-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez A, Berrío JC, Hooghiemstra H, Becerra M, Marchant R. 2007. A holocene pollen record of vegetation change and human impact from Pantano de Vargas, an intra-Andean basin of Duitama, Colombia. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 145, 143–157. ( 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.10.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Der Hammen T, Hooghiemstra H. 1995. The EL abra stadial, a younger dryas equivalent in Colombia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 14, 841–851. ( 10.1016/0277-3791(95)00066-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berrio JC, Hooghiemstra H, Behling H, Botero P, Van der Borg K. 2002. Late-Quaternary savanna history of the Colombian Llanos Orientales from Lagunas Chenevo and Mozambique: a transect synthesis. Holocene 12, 35–48. ( 10.1191/0959683602hl518rp) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velez MI, Wille M, Hooghiemstra H, Metcalfe S, Vandenberghe J, Van Der Borg K.. 2001. Late holocene environmental history of southern Chocó region, Pacific Colombia; sediment, diatom and pollen analysis of core El Caimito. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 173, 197–214. ( 10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00322-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behling H, Hooghiemstra H, Negret AJ. 1998. Holocene history of the Choco rain forest from Laguna Piusbi, southern Pacific lowlands of Colombia. Quat. Res. 50, 300–308. ( 10.1006/qres.1998.1998) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epping I. 2009. Environmental change in the Colombian upper forest belt. Master's thesis University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 31.González-Carranza Z, Hooghiemstra H, Vélez MI. 2012. Major altitudinal shifts in Andean vegetation on the Amazonian flank show temporary loss of biota in the Holocene. Holocene 22, 1227–1241. ( 10.1177/0959683612451183) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berrío JC, Arbeláez MV, Duivenvoorden JF, Cleef AM, Hooghiemstra H. 2003. Pollen representation and successional vegetation change on the sandstone plateau of Araracuara, Colombian Amazonia. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 126, 163–181. ( 10.1016/S0034-6667(03)00083-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Restrepo A, Colinvaux P, Bush M, Correa-Metrio A, Conroy J, Gardener MR, Jaramillo P, Steinitz-Kannan M, Overpeck J. 2012. Impacts of climate variability and human colonization on the vegetation of the Galápagos Islands. Ecology 93, 1853–1866. ( 10.1890/11-1545.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adolf C, Behling H, Erler R, Tinner W. 2011. A new High-Andean Postglacial record of climatic and human influence on vegetation in Southern Ecuador. Master's thesis, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitney BS, Dickau R, Mayle FE, Walker JH, Soto JD, Iriarte J. 2014. Pre-Columbian raised-field agriculture and land use in the Bolivian Amazon. Holocene 24, 231–241. ( 10.1177/0959683613517401) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitney BS, Dickau R, Mayle FE, Soto JD, Iriarte J. 2013. Pre-Columbian landscape impact and agriculture in the Monumental Mound region of the Llanos de Moxos, lowland Bolivia. Quat. Res. (United States) 80, 207–217. ( 10.1016/j.yqres.2013.06.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enters D, Behling H, Mayr C, Dupont L, Zolitschka B. 2010. Holocene environmental dynamics of south-eastern Brazil recorded in laminated sediments of Lago Aleixo. J. Paleolimnol. 44, 265–277. ( 10.1007/s10933-009-9402-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leyden BW, Brenner M, Whitmore TJ, Curtis JH, Piperno DR, Dahlin BH. 1996. A record of long- and short-term climatic variation from northwest Yucatan: Cenote San Jose Chulchaca. In The managed mosaic: ancient Maya agriculture and resource use (ed. Fedick SL.), pp. 30–50. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Legendre P, Birks HJB. 2012. Clustering and partitioning. In Tracking environmental change using lake sediments. Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research, vol 5 (eds Birks HJB, Lotter AF, Juggins S, Smol JP), pp. 167–200. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birks HJB, Gordon AD. 1985. Numerical methods in quaternary pollen analysis. New York, NY: Academic Press; See https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=o7yzAAAAIAAJ. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juggins S. 2017. rioja: Analysis of Quaternary science data. R package version 0.9-15. See http://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/stephen.juggins/. [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team. 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overpeck JT, Webb T, Prentice IC. 1985. Quantitative interpretation of fossil pollen spectra: dissimilarity coefficients and the method of modern analogs. Quat. Res. 23, 87–108. ( 10.1016/0033-5894(85)90074-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennion H, Fluin J, Simpson GL. 2004. Assessing eutrophication and reference conditions for Scottish freshwater lochs using subfossil diatoms. J. Appl. Ecol. 41, 124–138. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2004.00874.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adolf C, et al. 2020. Data from: Identifying drivers of forest resilience in long-term records from the Neotropics Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.xwdbrv19c) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Birks HJB, Felde VA, Bjune AE, Grytnes JA, Seppä H, Giesecke T. 2016. Does pollen-assemblage richness reflect floristic richness? A review of recent developments and future challenges. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 228, 1–25. ( 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.12.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Felde VA, Peglar SM, Bjune AE, Grytnes J-A, Birks HJB. 2015. Modern pollen–plant richness and diversity relationships exist along a vegetational gradient in southern Norway. Holocene 26, 163–175. ( 10.1177/0959683615596843) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birks HJB. 2007. Estimating the amount of compositional change in late-quaternary pollen-stratigraphical data. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 16, 197–202. ( 10.1007/s00334-006-0079-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colombaroli D, Tinner W. 2013. Determining the long-term changes in biodiversity and provisioning services along a transect from Central Europe to the Mediterranean. Holocene 23, 1625–1634. ( 10.1177/0959683613496290) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Birks HJB, Line JM. 1992. The use of rarefaction analysis for estimating palynological richness from quaternary pollen-analytical data. Holocene 2, 1–10. ( 10.1177/095968369200200101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker N, Saveliev AA, Smith GM. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akaike H. 1973. Information theory as an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Second international symposium on information theory (eds Petrov BN, Csaki F), pp. 267–281. Budapest, Hungary: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugita S. 1994. Pollen representation vegetation in in quaternary of vegetation: theory and method in Patchy vegetation. J. Ecol. 82, 881–897. ( 10.2307/2261452) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team. 2017. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-13. See https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=nlme. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hooper DU, et al. 2005. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 3–35. ( 10.1890/04-0922) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cardinale BJ, et al. 2009. Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of ecosystems: a summary of 164 experimental manipulations of species richness. Ecology 90, 854–854. ( 10.1890/08-1584.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vázquez A, Vélez R. 1998. Recent history of forest fires in Spain. In Large forest fire (ed. Moreno JM.), pp. 159–185. Leiden, The Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morin X, Fahse L, de Mazancourt C, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Bugmann H.. 2014. Temporal stability in forest productivity increases with tree diversity due to asynchrony in species dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 17, 1526–1535. ( 10.1111/ele.12357) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loreau M, de Mazancourt C.. 2013. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 16, 106–115. ( 10.1111/ele.12073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tinner W, Theurillat J-P. 2003. Uppermost limit, extent, and fluctuations of the timberline and treeline Ecocline in the Swiss Central Alps during the past 11 500 Years. Arctic, Antarct. Alp. Res. 35, 158–169. ( 10.1657/1523-0430(2003)035[0158:uleafo[2.0.co;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Adolf C, et al. 2020. Data from: Identifying drivers of forest resilience in long-term records from the Neotropics Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.xwdbrv19c) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All R scripts and parts of datasets (details on accessing Neotoma datasets are in the electronic supplementary material) used for analyses are available under: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.xwdbrv19c [45]. Description of the datasets can be found in electronic supplementary material, S7.