Abstract

The global fight against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is largely based on strategies to boost immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and prevent its severe course and complications. The human defence may include antibodies which interact with SARS-CoV-2 and neutralize its aggressive actions on multiple organ systems. Protective cross-reactivity of antibodies against measles and other known viral infections has been postulated, primarily as a result of the initial observations of asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 in children. Uncontrolled case series have demonstrated virus-neutralizing effect of convalescent plasma, supporting its efficiency at early stages of contracting SARS-CoV-2. Given the variability of the virus structure, the utility of convalescent plasma is limited to the geographic area of its preparation, and for a short period of time. Intravenous immunoglobulin may also be protective in view of its nonspecific antiviral and immunomodulatory effects. Finally, human monoclonal antibodies may interact with some SARS-CoV-2 proteins, inhibiting the virus-receptor interaction and prevent tissue injury. The improved understanding of the host antiviral responses may help develop safe and effective immunotherapeutic strategies against COVID-19 in the foreseeable future.

Keywords: COVID-19, Comorbidities, Vaccination, Convalescent Serum, Antibodies, Immunotherapy

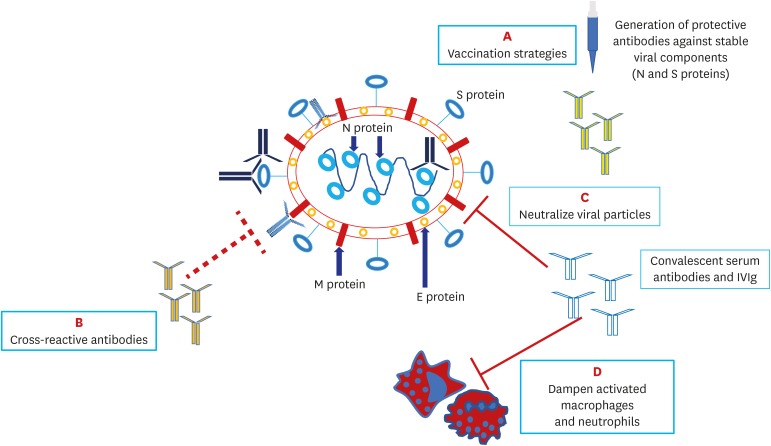

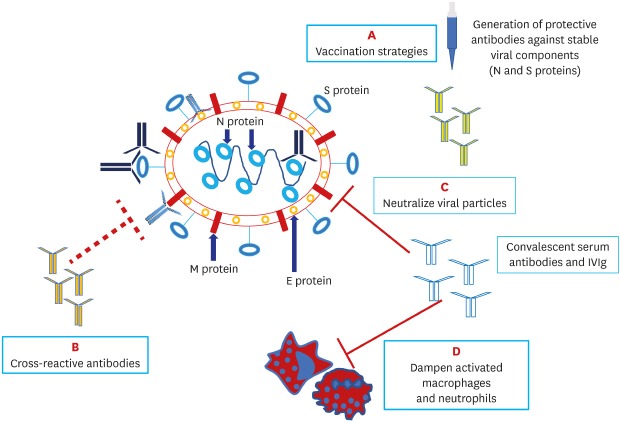

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The global fight against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) requires concerted efforts of all specialists with advanced knowledge and skills in public health, epidemiology, virology and immunology. The improved understanding of the virus structure and its destructive actions with hyperinflammation and dreadful systemic manifestations points to the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach. Such an approach is required for timely diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 and preventing further spread of the virus in the community.

As of May 1, 2020, there are 3,319,856 globally recorded cases of contracting the virus and 234,279 related deaths.1 The USA, Italy, UK, Spain and France are now the five countries with the highest death toll. The high mortality figures in the developed countries can be associated with aging, reduced cardiopulmonary reserves, and immune dysregulations.2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of the current pandemic, has distinctive genetic features, with two subtypes (L and S) and more than 140 mutation points, making it highly contagious and capable of spreading globally.3 Four main proteins in the structure of SARS-CoV-2 are found responsible for human cell interaction and intracellular replication: membrane (M), envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N) and spike (S) proteins. Scientists believe that there are mutation-resistant epitopes in the genes encoding S and N proteins that can be identified in experimental vaccine models and targeted by antibodies (Fig. 1).4

Fig. 1. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 and potential antibody targets.

SARS-CoV-2 has four major targets: the N protein covering the viral ribonucleic acid (RNA), the E protein encompassing the viral envelope, the M protein protruding from the cell membrane and the S protein that engages with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor on host cells. Specific neutralizing IgG antibodies to N and S proteins, which are less prone to mutate, may provide successful host immunity; these are also potential targets for future vaccination strategies (A). Antibodies to E and M proteins, which often mutate, may not be protective against SARS-CoV-2. Cross-reactive antibodies which are generated in response to measles and other known viral vaccines may offer a degree of anti-SARS-CoV-2 protection (B). Intravenous immunoglobulin and neutralizing antibodies in convalescent serum may block the virus entry to host cells (C) and dampen hyperinflammation (D).

SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, N = nucleocapsid, E = envelope, M = membrane, S = spike.

Although all age groups are susceptible to the virus, the incidence of COVID-19 in children (1.3%) is three times lesser than that in adults (3.5%).3 Also, with the exception of those with cardiovascular and other comorbidities, children are generally less prone to severe COVID-19 and related mortality,5,6 which could be due to the peculiarities of their adaptive immune system and low prevalence of cytokine storm syndromes.7 Rare cases of COVID-19 in children at the early stage of the pandemic are likely associated with lower exposure to the virus which increased with exponential growth of the number of infected individuals.8

Physiological disbalance in T-helper 1 and 2 reactions with dominance of the latter during pregnancy makes pregnant women vulnerable to COVID-19 and other viral infections.9 Maternal antiviral antibody production can be suppressed until after delivery,10 further complicating the serodiagnostics of COVID-19.

Patients with rheumatic diseases, particularly those on immunosuppressive therapies, form another high-risk group. Preliminary observational research points to the risk of severe COVID-19 and death in adult rheumatic patients with preexisting comorbidity (lung involvement), although the true extent of such risk remains to be ascertained.11,12,13

The most dreadful complication of COVID-19 is the cytokine storm syndrome, which is often experienced by high-risk individuals with obesity, hypertension, diabetes, history of smoking and lung disease. The syndrome rapidly develops as an excessive immune response to the virus, triggered by inflammatory cells infiltration in the lungs, activation of T-helper 1 reactions and abundant release of proinflammatory cytokines into the circulation.14 Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive drug therapies along with cardiorespiratory fitness are viewed as potential strategies for limiting the destructive effects of cytokine storm in COVID-19.15

While results of evidence-based research studies are expected to accumulate in the coming weeks and months, physicians confronting COVID-19 are now offered practice recommendations based on uncontrolled case series and expert opinion. In the absence of the long-term prospective studies, hypotheses are generated to launch cohort studies and trials on prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Some of these hypotheses may lack justification and pose ethical challenges. The interpretation of such hypotheses needs to be done through the prism of research reporting standards.16

In the absence of highly effective antiviral drugs and approved COVID-19 vaccines, the urgent response to the virus spread may include boosting the immune system and utilizing virus-neutralizing antibodies. In this article, we overview perspectives of antibody production and immune therapy in COVID-19.

CROSS-REACTIVITY

A good example is a hypothesis associating mandatory vaccinations against measles and other known viral diseases with cross-resistance to COVID-19 in children.17 The idea of the cross-reactivity is based on an observation suggesting that subjects who recover from measles and those vaccinated with measles, mumps and rubella vaccine produce antibodies to a variety of HIV-1 proteins.18 This hypothesis might shed light on milder or asymptomatic course of COVID-19 and low mortality in Chinese children who are mandatory vaccinated against measles.19 Although harshly criticized and withdrawn for revision, a preprint of structural similarities between some glycoproteins of the novel coronavirus and HIV-1 may provide a point further stimulating the global interest toward the cross-reactivity phenomenon.20 The hypothesized structural similarities may justify the empirical use of HIV protease inhibitors, such as lopinavir and ritonavir, that proved effective in some COVID-19 patients.21 Additionally, the first case of early clearance of the novel coronavirus in a patient with HIV and hepatitis C virus co-infection and successful recovery from COVID-19 pneumonia also points to a crucial role of cross-reactive antibodies.22

BCG VACCINATION

An interesting hypothesis is generated suggesting that multiple doses of tuberculosis vaccine bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) could be protective against COVID-19 due to the so-called trained immunity phenomenon.23 The same strategy is proved to be safe and effective in autoimmune disorders, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and multiple sclerosis. A recent preprint revealed nonspecific beneficial effects of universal BCG vaccination on hindering COVID-19 spread and its complications in some countries (e.g., Japan).24 The observed differing COVID-19 mortality rates across countries allow hypothesizing that increasing/implementing BCG vaccination may be protective during this pandemic, particularly in countries with no mandatory vaccination policy. The nonspecific protective effect of BCG vaccine can be clarified when results of the two ongoing trials become available.25,26 Both are phase 3 studies associated with vulnerability at hospital settings, particularly due to the no intervention.

BCG-CORONA (Reducing Health Care Workers Absenteeism in COVID-19 Pandemic Through BCG Vaccine) trial is expected to enrol 1,500 healthcare workers exposed to the virus within the coming 6 months and randomize them into BCG intradermal vaccination and placebo groups; number of days of unplanned absenteeism for any reason is primary outcome of the trial.25 BRACE trial (BCG Vaccination to Protect Healthcare Workers Against COVID-19) is set to enrol 4,170 participants, randomize them into intervention and no intervention groups, and record COVID-19 incidence and its severe course in the 12 months following randomization.26 These studies testing the effects of the nonspecific vaccination on the course of COVID-19 in adults may raise serious ethical concerns due to the risks of exposing vaccinated and non-vaccinated to the virus.

VACCINATION AGAINST INFLUENZA AND PNEUMOCCAL PNEUMONIA

In the face of the current pandemic, it is recommended to optimize coverage of healthy children and adults with influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations to mitigate the effects of community-acquired pneumonia.27 The same vaccination strategy is strongly recommended for the majority of patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases prior to the administration of immunosuppressive therapy.28 However, there are no studies suggesting the cross-resistance to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals vaccinated against influenza or pneumococcal pneumonia.

INTRAVENOUS IMMUNOGLOBULIN

An entirely different approach is proposed by experts hypothesizing that intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) can be effective for the treatment of COVID-19.29 Currently marketed IVIg preparations contain antibodies that cross-react against SARS-CoV-2 and other virus antigens in-vitro.30 IVIg preparations that contain proteins collected from thousands of healthy donors ameliorate the course of autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases by blocking Fc-gamma receptors and neutralizing inflammatory cytokines. The safety profile of IVIg therapy can be improved by switching to subcutaneous administration. The initial cases of high-dose IVIg therapy (25 g/day for 5 days) combined with antivirals (lopinavir/ritonavir) and methylprednisolone in severe COVID-19 in Wuhan, China demonstrated elevation of lymphocyte counts, decrease of inflammatory markers, partial/complete resolution of specific lung affections, and negative nasal and oropharyngeal swab tests within a few days of therapy.31

CONVALESCENT SERUM

To increase the efficiency of the virus-neutralizing antibody therapies, it is proposed to collect and utilize hyperimmune IgG antibodies from subjects who have recovered from COVID-19 and produced high amount of the antibodies.32 Due to the existence of different strains of the virus variably spread across cities and countries, potential plasma donors should be from the same geographical area as the recipient patients. Passive antibody therapy can modulate phagocytosis and cytotoxicity and exert additive virus-neutralizing effect in combination with antiviral drugs.33

The required amount of antibodies in convalescent serum and duration of therapy depend on the viral load and severity of COVID-19. It is believed that virus-neutralizing antibodies, even in small quantities, can be effective when used for prevention or treatment of early symptoms of COVID-19. The emergency administration of the serum is primarily indicated in individuals with chronic underlying diseases, healthcare workers, and healthy subjects who have contacted infected patients. The resultant passive immunity may last for weeks and months.33 Although antibodies can be collected and stored for a long time, timing for their optimal use depends on the likelihood of mutations that may change the virus characteristics. Ideally, antibodies should be used within days of collection. The same antibodies cannot be effective if used beyond a seasonal outbreak.34

A big issue is the shortage of convalescent serum with high titers of virus-neutralizing antibodies. An unpublished study of 175 Chinese patients who recovered from mild COVID-19 revealed that about 6% of the patients do not produce detectable level of neutralizing antibodies and about 30% of them present with very low titers.35 In all these patients, antibody production increased at day 10 to 15 after disease onset. Surprisingly, elderly (60–85 years) and middle-age (40–59) patients, who presented with lower lymphocyte counts and higher level inflammatory markers, produced significantly higher amounts of neutralizing antibodies than younger (15–39) patients.35 Another Chinese cohort study demonstrated that 9% of recovered patients repetitively present with SARS-CoV-2 positivity and COVID-19 symptoms within 17 days of recovery, pointing to high baseline viral load, various immune dysfunctions, and virus persistence.36 Interestingly, a large Chinese study (n = 173) of seroconversion and SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection rates revealed that total antibodies against the virus were present in about 40% of patients within 1st week of disease onset and in all patients after 2 weeks.37 During the same periods, RNA detectability decreased from 67% to 45%,36 raising concerns that not all specific antibodies are able to neutralize the virus. Variable timing and deficiency of antibody production in a sizable proportion of COVID-19 patients pose yet another challenge, questioning the utility of antibody tests and related “immunity passports” in the general population.38

Potential serum donor candidates are individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 with high SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies (above 1:160) and free of any viral and bacterial infections.39 An initial uncontrolled case series of 5 critically-ill Chinese patients with COVID-19 demonstrated the efficiency and safety of convalescent plasma with high levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies combined with antivirals and methylprednisolone.40 Plasma transfusion resulted in improving the patients' clinical status, decreasing viral load, and increasing titers of neutralizing antibodies within 12 days.

Another study of 6 cases of plasma therapy in patients with COVID-19 and respiratory failure at a median 21.5 days after the virus detection in nasopharyngeal swabs demonstrated viral clearance within 3 days in all patients.41 Eventually, only 1 patient recovered and 5 patients died, possibly due to the delayed transfusion of convalescent plasma.

Finally, a case series of 10 patients with severe COVID-19 treated with convalescent plasma revealed clinical and chest radiology improvement in all patients. Two out of three patients who required mechanical ventilation could further be weaned off this.42

Major limitation of all reported case series is the absence of matched control subjects who were not on convalescent plasma therapy. Although empirical experience with plasma therapies during previous coronavirus epidemics alerted physicians of the risk of anaphylactic reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and hemolysis,43 no serious adverse effects have been reported during the current pandemic.

MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES

Specific human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) blocking SARS-CoV-2 interaction with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2) receptors and virus entry to human cells may offer more targeted options.44 Collecting B lymphocytes from patients who have recovered from COVID-19, identifying cells capable of producing the required neutralizing antibodies, and cloning blocking mAbs is a labor-intensive task. Identifying and standardizing the required mAbs is even more sophisticated task since the variability of the receptor-binding proteins can yield irreproducible results.45 One of the initial in-vitro studies that aimed to clone mAbs reported high titers of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) 1 subunit of the surface protein and its receptor-binding locus in the majority of recovered patients.46 Reportedly, only a small fraction of these antibodies potently blocks the interaction with ACE2. The results of harvesting these blocking mAbs by using human B cells are promising, although no any attempt has been made to conduct related clinical study and explore the risk of adverse effects such as transfusion-related acute lung injury.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitates mobilizing all available resources for containing the virus spread. It is apparent that isolation, social distancing, use of personal protective equipment, and proper individual and population hygiene decrease exposure to the deadly virus and minimize risk of severe COVID-19. Such protective measures can primarily save lives of high-risk individuals, such as children, pregnant women, medics, patients with underlying immunosuppressive and other chronic diseases, and the elderly. It is hypothesized that individuals regularly vaccinated against some infections, such measles and tuberculosis, may demonstrate better outcomes when exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Considering all safety issues, high-risk populations should undergo regular vaccinations to train their immunity and actively produce antibodies that may cross-react with SARS-CoV-2. Given the limitations of the cross-reactivity, particularly exhaustion of active immune response over time and with aging, passive antibody therapy can be indicated in subjects with early symptoms of COVID-19 and those with recent contacts with patients. Observational studies suggest that convalescent plasma with high amount of virus-neutralizing antibodies is effective for emergency use, well before the virus-related multiple organ affections become evident.

Several attempts are being made to use IVIg and monoclonal antibodies in COVID-19. However, both approaches are expensive. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 is capable of mutating, further challenging the use of specific antibody therapies.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any institution or association.

- Conceptualization: Gasparyan AY, Yessirkepov M, Zimba O.

- Methodology: Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Zimba O.

- Project administration:

- Writing - original draft: Gasparyan AY, Zimba O.

- Writing - review & editing: Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Yessirkepov M, Zimba O.

References

- 1.Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 2.Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. African American COVID-19 mortality: a sentinel event. J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.She J, Liu L, Liu W. COVID-19 epidemic: disease characteristics in children. J Med Virol. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed SF, Quadeer AA, McKay MR. Preliminary identification of potential vaccine targets for the COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on SARS-CoV immunological studies. Viruses. 2020;12(3):E254. doi: 10.3390/v12030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licciardi F, Giani T, Baldini L, Favalli EG, Caporali R, Cimaz R. COVID-19 and what pediatric rheumatologists should know: a review from a highly affected country. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-00422-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedrich CM. COVID-19 - Considerations for the paediatric rheumatologist. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108420. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagarro A, Epalza C, Santos M, Sanz-Santaeufemia FJ, Otheo E, Moraleda C, et al. Screening and severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children in Madrid, Spain. JAMA Pediatr. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1346. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dashraath P, Wong JL, Lim MX, Lim LM, Li S, Biswas A, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alzamora MC, Paredes T, Caceres D, Webb CM, Valdez LM, La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra DP, Agarwal V, Gasparyan AY, Zimba O. Rheumatologists' perspective on coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) and potential therapeutic targets. Clin Rheumatol. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05073-9. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favalli EG, Agape E, Caporali R. Incidence and clinical course of COVID-19 in patients with connective tissue diseases: a descriptive observational analysis. J Rheumatol. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200507. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favalli EG, Ingegnoli F, Cimaz R, Caporali R. What is the true incidence of COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic diseases? Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217615. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zbinden-Foncea H, Francaux M, Deldicque L, Hawley JA. Does high cardiorespiratory fitness confer some protection against pro-inflammatory responses after infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity (Silver Spring) doi: 10.1002/oby.22849. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mukanova U, Yessirkepov M, Kitas GD. Scientific hypotheses: writing, promoting, and predicting implications. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(45):e300. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salman S, Salem ML. Routine childhood immunization may protect against COVID-19. Med Hypotheses. 2020;140:109689. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baskar PV, Collins GD, Dorsey-Cooper BA, Pyle RS, Nagel JE, Dwyer D, et al. Serum antibodies to HIV-1 are produced post-measles virus infection: evidence for cross-reactivity with HLA. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111(2):251–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradhan P, Pandey AK, Akhilesh Mishra A, Gupta P, Tripathi PK, Menon MB, et al. WITHDRAWN: uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.30.927871v1. [DOI]

- 21.Nutho B, Mahalapbutr P, Hengphasatporn K, Pattaranggoon NC, Simanon N, Shigeta Y, et al. Why are lopinavir and ritonavir effective against the newly emerged coronavirus 2019?: atomistic insights into the inhibitory mechanisms. Biochemistry. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00160. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J, Liao X, Wang H, Wei L, Xing M, Liu L, et al. Early virus clearance and delayed antibody response in a case of COVID-19 with a history of co-infection with HIV-1 and HCV. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa408. Forthcoming 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayoub BM. COVID-19 vaccination clinical trials should consider multiple doses of BCG. Pharmazie. 2020;75(4):159. doi: 10.1691/ph.2020.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sala G, Miyakawa T. Association of BCG vaccination policy with prevalence and mortality of COVID-19. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.30.20048165v1.full.pdf. [DOI]

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov. Reducing health care workers absenteeism in COVID-19 pandemic through BCG vaccine (BCG-CORONA) [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04328441.

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov. BCG vaccination to protect healthcare workers against COVID-19 (BRACE) [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04327206.

- 27.Mendelson M. Could enhanced influenza and pneumococcal vaccination programs help limit the potential damage from SARS-CoV-2 to fragile health systems of southern hemisphere countries this winter? Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:32–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, Agmon-Levin N, van Assen S, Bijl M, et al. 2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):39–52. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jawhara S. Could Intravenous immunoglobulin collected from recovered coronavirus patients protect against COVID-19 and strengthen the immune system of new patients? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):E2272. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Díez JM, Romero C, Gajardo R. Currently available intravenous immunoglobulin (Gamunex®-C and Flebogamma® DIF) contains antibodies reacting against SARS-CoV-2 antigens. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.07.029017v2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Cao W, Liu X, Bai T, Fan H, Hong K, Song H, et al. Dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(3):a102. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. COVID-19 - navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1268–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(4):1545–1548. doi: 10.1172/JCI138003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roback JD, Guarner J. Convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19: possibilities and challenges. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu F, Wang A, Liu M, Wang Q, Chen J, Xia S, et al. Neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a COVID-19 recovered 2 patient cohort and their implications. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed May 1, 2020]. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.30.20047365v2.full.pdf. [DOI]

- 36.Ye G, Pan Z, Pan Y, Deng Q, Chen L, Li J, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reactivation. J Infect. 2020;80(5):e14–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W, Liao X, Su Y, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallapaty S. Will antibody tests for the coronavirus really change everything? Nature. 2020;580(7805):571–572. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01115-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Pang R, Xue X, Bao J, Ye S, Dai Y, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus antibody levels in convalescent plasma of six donors who have recovered from COVID-19. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(8):6536–6542. doi: 10.18632/aging.103102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J, et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1582. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng QL, Yu ZJ, Gou JJ, Li GM, Ma SH, Zhang GF, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on viral shedding and survival in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan K, Liu B, Li C, Zhang H, Yu T, Qu J, et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9490–9496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Q, He Y. Challenges of convalescent plasma therapy on COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104358. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shanmugaraj B, Siriwattananon K, Wangkanont K, Phoolcharoen W. Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38(1):10–18. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian X, Li C, Huang A, Xia S, Lu S, Shi Z, et al. Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):382–385. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen X, Li R, Pan Z, Qian C, Yang Y, You R, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]