Abstract

Background

Depression is an important consequence of stroke that influences recovery yet often is not detected, or is inadequately treated. This is an update and expansion of a Cochrane Review first published in 2004 and previously updated in 2008.

Objectives

The primary objective is to test the hypothesis that pharmacological, psychological therapy, non‐invasive brain stimulation, or combinations of these interventions reduce the incidence of diagnosable depression after stroke. Secondary objectives are to test the hypothesis that pharmacological, psychological therapy, non‐invasive brain stimulation or combinations of these interventions reduce levels of depressive symptoms and dependency, and improve physical functioning after stroke. We also aim to determine the safety of, and adherence to, the interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Specialised Register of Cochrane Stroke and the Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis (last searched August 2018). In addition, we searched the following databases; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library, 2018, Issue 8), MEDLINE (1966 to August 2018), Embase (1980 to August 2018), PsycINFO (1967 to August 2018), CINAHL (1982 to August 2018) and three Web of Science indexes (2002 to August 2018). We also searched reference lists, clinical trial registers (World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP); to August 2018 and ClinicalTrials.gov; to August 2018), conference proceedings; we also contacted study authors.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing: 1) pharmacological interventions with placebo; 2) one of various forms of psychological therapy with usual care and/or attention control; 3) one of various forms of non‐invasive brain stimulation with sham stimulation or usual care; 4) a pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy with a pharmacological intervention and usual care and/or attention control; 5) non‐invasive brain stimulation and pharmacological intervention with a pharmacological intervention and sham stimulation or usual care; 6) pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy with placebo and psychological therapy; 7) pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation with placebo plus non‐invasive brain stimulation; 8) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus non‐invasive brain stimulation plus usual care and/or attention control; and 9) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus sham brain stimulation or usual care plus psychological therapy, with the intention of preventing depression after stroke.

Data collection and analysis

Review authors independently selected studies, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data from all included studies. We calculated mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous data and risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic and assessed the certainty of evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We included 19 RCTs (21 interventions), with 1771 participants in the review. Data were available for 12 pharmacological trials (14 interventions) and seven psychological trials. There were no trials of non‐invasive brain stimulation compared with sham stimulation or usual care, a combination of pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy with placebo and psychological therapy, or a combination of non‐invasive brain stimulation and a pharmacological intervention with a pharmacological intervention and sham stimulation or usual care to prevent depression after stroke. Treatment effects were observed on the primary outcome of meeting the study criteria for depression at the end of treatment: there is very low‐certainty evidence from eight trials (nine interventions) that pharmacological interventions decrease the number of people meeting the study criteria for depression (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.68; 734 participants) compared to placebo. There is very low‐certainty evidence from two trials that psychological interventions reduce the proportion of people meeting the study criteria for depression (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.94, 607 participants) compared to usual care and/or attention control.

Eight trials (nine interventions) found no difference in death and other adverse events between pharmacological intervention and placebo groups (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.32 to 4.91; 496 participants) based on very low‐certainty evidence. Five trials found no difference in psychological intervention and usual care and/or attention control groups for death and other adverse events (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.91; 975 participants) based on very low‐certainty evidence.

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence suggests that pharmacological interventions and psychological therapy may prevent depression and improve mood after stroke. However, there is very low certainty in these conclusions because of the very low‐certainty evidence. More trials are required before reliable recommendations can be made about the routine use of such treatments after stroke.

Plain language summary

Interventions for preventing depression after stroke

Review question

Do pharmacological, psychological, non‐invasive brain stimulation or a combination of these interventions prevent depression and improve outcomes after stroke?

Background

The role of interventions for preventing depression after stroke is unclear. Depression is a common and important complication of stroke that is often missed or poorly managed. Little is known about whether prevention strategies started early after stroke will reduce the risk of depression and improve recovery for those not depressed at assessment.

Search date

We identified trials using searches conducted on 13 August 2018.

Study characteristics

We included trials which reported on the use of pharmacological and psychological interventions to prevent depression after stroke. Average age of participants ranged from 55 to 73 years. Trials were from Asia (3), Europe (8), North America (5), and Australia (3).

Key results

We included 19 trials (12 pharmacological and seven psychological) involving 1771 participants. Outcome information was available for nine pharmacological and two psychological trials, which suggested that these treatments might reduce the risk of developing depression. A smaller number of studies (eight pharmacological and five psychological studies) found no increase in death or adverse events.

Certainty of evidence

We rated the certainty of evidence as very low due to limitations in study design.

Conclusion

Our ability to generalise these findings to all stroke survivors is limited due to the small proportion of survivors who were eligible to participate in these clinical trials. More well‐designed clinical trials are needed that test practical interventions for preventing depression across all stroke survivors.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) compared to placebo for preventing depression after stroke.

| Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) compared to placebo for preventing depression after stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with stroke Setting: hospital and community Intervention: pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) | |||||

| Depression: meeting study criteria for depression at end treatment (Analysis 1.1) | Study population | RR 0.50 (0.37 to 0.68) | 734 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ||

| 250 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 (92.5 to 170) | |||||

| Scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder at end of treatment (Analysis 1.2) | ‐ | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | No data available. | |

| Depression: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 1.4) | MD 0.59 higher (1.46 lower to 2.63 higher) | ‐ | 100 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | HDRS (high score = more depressed) | |

| Cognition: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 1.6) | MD 0.42 lower (2.60 lower to 1.76 higher) | ‐ | 48 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | MMSE (low score = cognitive impairment) | |

| Activities of daily living: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 1.8) | MD 3.86 lower (9.48 lower to 1.77 higher) | ‐ | 116 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | Barthel Index (high score = more dependent) | |

| Disability: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 1.10) | ‐ | ‐ | 204 (4 studies) | ‐ | No totals. Hemispheric Stroke Scale Total Score (high score = more neurological deficit) Johns Hopkins Functioning Inventory (high score = less function) |

|

| Adverse events: death ‐ at end of treatment Analysis 1.12 | Study population | RR 1.25 (0.32 to 4.91) | 496 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence as the studies were rated as unclear or high risk in multiple risk of bias domains.

bWe downgraded the certainty of evidence because the confidence intervals were wide.

cWe downgraded the certainty of evidence because the confidence intervals were very wide.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 1: Depression: meeting study criteria for depression at end treatment

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 2: Scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder at end of treatment

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 4: Depression: mean scores at end of treatment

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 6: Cognition: Mean scores at end of treatment

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 8: Activities of daily living: mean scores at end of treatment

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 10: Disability: mean scores at end of treatment

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Pharmacological interventions (antidepressants) versus placebo, Outcome 12: Adverse events: death

Summary of findings 2. Psychological therapy compared to usual care and/or attention control for preventing depression after stroke.

| Psychological therapy compared to usual care and/or attention control for preventing depression after stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with stroke Setting: hospital and community Intervention psychological therapy Comparison: usual care and/or attention control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care and/or attention control | Risk with psychological therapy | |||||

| Depression: meeting study criteria for depression at end of treatment (Analysis 2.1) | Study population | RR 0.68 (0.49 to 0.94) | 607 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | ||

| 296 per 1000 | 201 per 1000 (145 to 278) | |||||

| Scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder at end of treatment (Analysis 2.2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | (0 RCTs) | ‐ | No data available |

| Depression: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 2.3) | ‐ | ‐ | 132 (2 studies) | ‐ | No totals HDRS (high score = more depressed) MADRS (high score = more depressed) |

|

| Psychological distress: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 2.6) | ‐ | ‐ | 450 (1 RCT) | No totals GHQ‐28 (high score = greater psychological distress) |

||

| General Health: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 2.8) | MD 4.60 higher (21.25 lower to 30.45 higher) | ‐ | 240 (1 study) | ‐ | No totals Nottingham Health Profile (high score = better health) |

|

| Social activities: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 2.10) | MD 0.39 lower (3.81 lower to 3.03 higher) | ‐ | 690 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | Frenchay Activities Index (high score = better level of activity) | |

| Activities of daily living: mean scores at end of treatment (Analysis 2.12) | ‐ | ‐ | 879 (4 studies) | ‐ | No totals Barthel Index (high score = more dependent) Nottingham Extended Activities of daily living (high score = more independent) |

|

| Adverse events: death ‐ at end of treatment (Analysis 2.16) | Study population | RR 1.18 (0.73 to 1.91) | 975 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | ||

| 42 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (30 to 79) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GHQ‐28: 28‐item General Health Questionnaire; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS: Montgomery Aserg Depression Rating Scale; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aWe downgraded the certainty of evidence as the studies were rated high risk in multiple risk of bias domains.

bWe downgraded the certainty of evidence because the confidence intervals were wide.

cWe downgraded the certainty of evidence because the confidence intervals were very wide.

dWe downgraded the certainty of evidence because of substantial heterogeneity observed (I = 80%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 1: Depression: meeting study criteria for depression at end of treatment

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 2: Scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder at end of treatment

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 3: Depression: mean scores at end of treatment

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 6: Psychological distress: mean scores at end of treatment

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 8: General Health: Mean scores at end of treatment

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 10: Social activities: mean scores at end of treatment

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 12: Activities of daily living: mean scores at end of treatment

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapy versus standard care and/or attention control, Outcome 16: Adverse events: death

Background

Description of the condition

Depressive and anxiety disorders are important sequelae of stroke, occurring in up to half of people in the first year after onset, although estimates differ between studies due to varying definitions, populations, exclusion criteria, and the timing of assessments (Ayerbe 2013; Hackett 2014). Although there is much controversy surrounding stroke‐associated depression as a specific type of depressive syndrome, the condition may impede rehabilitation (Parikh 1990; Sinyor 1986), by impairing physical and cognitive function (Robinson 1986), and contributing to stress on carers (Anderson 1995). Furthermore, depression following stroke may also be associated with an increased risk of death (House 2001; Morris 1993), including death by suicide (Stenager 1998). Depressive illness among older people, in general, is associated with greater morbidity and dependency, higher use of drugs and alcohol, increased use of healthcare resources, and poor compliance with treatment of co‐morbid conditions (Katona 1995).

Description of the intervention

We considered three broad interventions in this review.

Pharmacological interventions designed to prevent depression: there are several classes of relevant pharmacological agents including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g. le fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and paroxetine), serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g. venlafaxine, milnacipran, sibutramine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (e.g. moclobemide), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g. nortriptyline, imipramine, and clomipramine), and other antidepressant medications including psychostimulants (e.g. methylphenidate), mood stabilisers (e.g. lithium), or benzodiazepines.

One of various forms of psychological intervention (talking therapy) designed to prevent depression: as there are many potential therapies we included any psychological intervention that involved direct person‐professional interaction. The content of the interaction could vary from counselling to specific psychotherapy provided it was directed at helping people develop their social problem‐solving skills and adjustment to the emotional impact of stroke. All interventions had to have a psychological component ‐ talking, listening, support, advice; be based on a theory of talking therapy; be structured and time‐tabled as a talking therapy; and be delivered by somebody with some explicitly stated training and supervision in therapies. The person‐professional interaction could take place in person, via telephone or other media. We did not include web‐based interventions even if mediated by a health professional. We did not include interventions based upon self‐management or supported self‐management.

Non‐invasive brain stimulation designed to prevent depression: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves the brief passage of an electrical current through the brain via electrodes applied to the scalp to induce a generalised seizure (i.e. a fit or convulsion). The seizure comprises two components: a central element, the ictus involving depolarisation (i.e. discharge of neurotransmitter chemicals) of brain cells, and a peripheral element of convulsive, jerking movements of the body, although this is now modified due to use of a short‐acting anaesthetic and muscle relaxant, as part of what is called modified ECT. Modified ECT replaced the initial crude equipment and techniques of unmodified ECT from the mid‐1950s. The seizure is detected by electrodes placed on the scalp to monitor brain electrical activity (i.e. EEG). The ECT electrodes can be placed on both sides of the head (bilateral placement), or on one side, usually the right side of the head (unilateral placement). The passage of an electrical current through the skull to the brain is necessary to trigger a seizure. In this update, we expanded the review to include other non‐invasive brain stimulation techniques such as 1) transcranial magnetic stimulation or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS or rTMS, where a magnetic 'coil' is placed near the head of the person receiving the treatment without making physical contact); 2) transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS, where a constant, low current is delivered directly to the brain area of interest via small electrodes); 3) cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES, where a small, pulsed electric current is applied across a person's head), and 4) magnetic seizure therapy (MST), a type of convulsive therapy that involves replacing the electrical stimulation used in ECT with a rapidly alternating strong magnetic stimulation.

We further considered these combinations of the three broad interventions.

Pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy with a pharmacological intervention and usual care and/or attention control.

Pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy with placebo and psychological therapy.

Pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation with a pharmacological intervention and sham stimulation or usual care.

Pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation with placebo plus non‐invasive brain stimulation.

Non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus non‐invasive brain stimulation plus usual care and/or attention control.

Non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus sham brain stimulation or usual care plus psychological therapy.

How the intervention might work

Pharmacological interventions are thought to alter the synaptic transmission process in the brain to increase neurotransmission, for example serotonin reuptake SSRIs are intended to block the transport of serotonin, SNRIs are designed to increase the levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, and TCAs are designed to block the reuptake of norepinephrine.

Psychological interventions focus on changing thought, emotional, behavioural, and relationship patterns. During psychological interventions, trained therapists work with individuals to help them see patterns in their thoughts, emotions, behaviours, or relationships that may be problematic. The therapist's role is to help a person understand the patterns and assist them in developing ways to overcome them.

During modified ECT a small amount of electric current is passed briefly across the brain to cause an artificial epileptic fit that affects the entire brain. Repeated ECT is believed to alter chemical pathways in the brain that are responsible for depression. The exact mechanism of action of TMS, rTMS, tDCS, and CES remains unclear. They are thought to induce intracerebral current flow, increase or decrease neuronal excitability and/or activate nerve cells in the specific area being stimulated. MST involves replacing the electrical stimulation used in ECT with a magnetic stimulus, which is purported to produce similar clinical effects but without the cognitive side effects.

Why it is important to do this review

Although depression may influence recovery and outcome following stroke, many, perhaps most, people do not receive effective treatment because their mood disorder is undiagnosed or inadequately treated (Ebrahim 1987; Hackett 2005a; House 1989). This is due in part to the problems with the diagnosis of a significant mood state among older people with disability. Even in otherwise healthy individuals, the assessment of abnormal mood is fraught with difficulty. Information from the general population suggests that, despite the severity and possible complications, only half of those with depression will seek professional help (WHO 2000). This may be due to the stigma associated with a diagnosis, people not realising they are unwell, or feeling their condition is beyond help, a natural part of ageing or a consequence of stroke. Given the problems inherent with diagnosis, that people are at high risk of developing depression after stroke, and the uncertainty about the balance of benefit and risks of treatment, there is interest in therapies commenced early after the onset of stroke that prevent abnormal mood and improve outcome. We undertook a systematic review of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), both published and unpublished, of pharmacological agents, psychological interventions, non‐invasive brain stimulation, or their combination for the prevention of depression associated with stroke. This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2004 (Anderson 2004), and last updated in 2008 (Hackett 2008).

Objectives

Primary objective

To determine whether pharmacological therapy, psychological therapy, non‐invasive brain stimulation or combinations of these interventions prevent the incidence of diagnosable depression after stroke.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether pharmacological therapy, psychological therapy, non‐invasive brain stimulation or combinations of these interventions reduce levels of depressive symptoms, improve physical and neurological function and health‐related quality of life, and reduce dependency after stroke.

To assess the safety of, and adherence to such treatments.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We restricted the review to all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). There was no restriction on eligibility of RCTs on the basis of language, sample size, duration of follow‐up, or publication status. Trials that met all the inclusion criteria, but in which no outcome data were available (either from the report of the trial or from the authors), could not contribute meaningfully to a pooled estimate of effect. These trials were regarded as 'dropouts' rather than ineligible and we have listed them in an additional table to indicate that they have not been overlooked (Table 3).

1. Characteristics of dropout studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Bramanti 1989 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: protirelin tartrate (TRH‐T) Control arm: placebo | Geographical location: Italy Setting: unclear Number of participants: 30 Stroke criteria: acute stroke Method of stroke diagnosis: not reported Inclusion criteria: not reported Exclusion criteria: not reported Depression criteria: not reported Number included in treatment group: unclear (63% male, mean age 72.2, SD not reported of the overall cohort) Number included in control group: unclear (63% men, mean age 72.2, SD not reported of the overall cohort) | Treatment: protirelin tartrate (TRHT) 2 mg/day Control: placebo Duration: 2 weeks Follow‐up: none |

|

Results not available in format suitable for the review |

| Downes 1995 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 3 Experimental arm 1: information + counselling Experimental arm 2: information pack Control arm: usual care | Geographical location: UK

Setting: outpatient

Number of participants: 62

Stroke criteria: not reported

Method of stroke diagnosis: not reported

Inclusion criteria: 1) lived at home; 2) had an informal carer; 3) stroke increase mRS; 4) post‐stroke mRS score of 2 to 5

Exclusion criteria: 1) not living at home; 2) not having an informal carer; 3) having no increase in disability or change in lifestyle/dependency Depression criteria: HADS score > 11 Number included in treatment group 1: 22 (50% men, age not reported) Number included in treatment group 2: 22 (55% men, age not reported) Number included in control group: 18 (44% men, age not reported) |

Treatment 1: information plus counselling. Egan's problem‐solving approach, individual is helped to explore concerns, clarify problems, set goals, and take appropriate action. Protocol discussed first and formulated into a counsellor/client contract. Information pack containing information on physical, cognitive, behavioural and emotional effects of stroke, carer well‐being, and local services.

Treatment 2: information only: information pack containing information on physical, cognitive,behavioural, and emotional effects of stroke, carer well‐being, and local services.

Control: usual care, no visit(s) or information pack provided

Duration: information session consisted of 1 visit and provision of the information pack. Counselling consisted of up to 8 counselling sessions over 4 to 6 months

Administered by: nurse counsellor Supervision: unclear Follow‐up: none |

|

Unable to isolate outcome data for non‐depressed participants at randomisation |

| Friedland 1992 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: psychoeducational support Control arm: usual care |

Geographical location: Canada

Setting: outpatient Number of participants: 88 Stroke criteria: all subtypes Method of stroke diagnosis: via clinical signs Inclusion criteria: 1) completed formal inpatient rehabilitation and a period of rehabilitation provided by a home care programme Exclusion criteria: 1) history of psychiatric admission, 2) previously on antidepressant medication, 3) aphasia with limited ability to communicate verbally Depression criteria: unclear Number included in treatment group: 48 (44% men, mean age 69 years, SD 11) Number included in control group: 40 (44% men, mean age 69 years, SD 11) |

Treatment: psychoeducational, with participant and members of their support team; work to improve social support, establish new supports, emotional support offered

Control: usual care, no visits

Duration: treatment continued for 6 to 12 sessions over approximately 3 months

Administered by: specially trained social support intervention therapist Supervision: unclear Follow‐up: 6 months (3 months post intervention) |

|

Results not available |

| Graffingo 2003 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: sertraline (SSRI) Control arm: matched placebo |

Geographical location: unclear

Setting: unclear Number of participants: unclear Stroke criteria: unclear Method of stroke diagnosis: unclear Inclusion criteria: unclear Exclusion criteria: unclear Depression criteria: unclear Number included in treatment group: unclear Number included in control group: unclear |

Treatment: sertraline (SSRI)

Control: matched placebo

Duration: unclear Follow‐up: unclear |

|

Results not available |

| Hadidi 2014 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: problem‐solving therapy (PST) Control arm: weekly telephone calls | Geographical location: USA Setting: inpatient Number of participants: 22 Stroke criteria: first time diagnosis of ischaemic stroke < 48 hours Method of stroke diagnosis: not reported Inclusion criteria: 1) Mini‐Cog score of 3; ≥ 50 years of age; 2) able to read and write in English Exclusion criteria: 1) previous history of mental health problems; 2) diagnosis of severe aphasia as identified by a speech pathologist; 3) haemorrhagic stroke or transient ischaemic attack; 4) medical instability requiring transfer to critical care Depression criteria: CES‐D score measured at baseline but patients recruited regardless of their CES‐D score. If CES‐D score > 10, or suicidal ideation the primary physician was notified Number included in treatment group: 11 (18% men, mean age 73) Number included in control group: 11 (45% men, mean age 69) |

Treatment: one‐on‐one problem solving therapy sessions lasting 1‐2 hours. Therapy entails providing patient information on impact and guidance to enable the patient to: identify and define the problem; brainstorm all potential solutions; select the most appropriate and feasible solution; create and implement a SMART (Specific, Measureable,

Achievable, Realistic and Timely) goal; evaluate and re‐view progress in follow‐up sessions

Administered by: a doctoral nursing student who received PST training through a 13‐ module online program adapted from a standard 3‐day in person training Supervision: principal investigator who had undergone in person PST training Intervention fidelity: not reported Control: weekly telephone calls to assess CES‐D and FIM scores Duration: once per week for 10 weeks Follow‐up: 3 months |

|

Unable to isolate outcome data for non‐ depressed participants at randomisation |

| Kim 2017 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: escitalopram (SSRI) Control arm: placebo |

Geographical location: South Korea Setting: inpatient Number of participants: 478 Stroke criteria: ischaemic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage Method of stroke diagnosis: confirmed by MRI or CT Inclusion criteria: 1) > 20 years, 2) had an acute ischaemic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage within the previous 21 days, 3) mRS score of 2 or greater at the time of screening, 4) agreed to participate Exclusion criteria: 1) history of diagnosed depression or other psychiatric diseases before the index stroke, 2) severe dementia, 3) cognitive dysfunction (stages 5‐7 of the Global Deterioration Scale), 4) aphasia, 5) on antimigraine or antiepileptic medication, 6) suicidal thoughts (a combined MADRS score > 8, 7) pregnant or lactating, 8) participation in another clinical trial Depression criteria: MADRS Number included in treatment group: 241 Number included in control group: 237 |

Treatment: oral escitalopram (SSRI) 10 mg/day Control: placebo Duration: 3 months Follow‐up: 6 months |

|

Unable to isolate outcome data for non‐ depressed participants at randomisation |

| Leathley 2003 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 4 Experimental arm 1: social support Experimental arm 2: psychological support (cognitive therapy based problem solving) Experimental arm 3: social support and psychological support Control arm: usual care |

Geographical location: UK

Setting: outpatient Number of participants: unclear Stroke criteria: unclear Method of stroke diagnosis: unclear Inclusion criteria: unclear Exclusion criteria: unclear Number included in treatment group 1: unclear Number included in treatment group 2: unclear Number included in treatment group 3: unclear Number included in control group: unclear |

Treatment 1: social support (information, practical advice, service liaison)

Treatment 2: psychological support (cognitive therapy based problem solving)

Treatment 3: social support and psychological support

Control: usual care, no visits

Duration: unclear

Administered by: unclear Supervision: unclear Follow‐up: unclear |

|

Results not available in format suitable for this review |

| McCafferty 2000 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: psychosocial intervention Control arm: usual care |

Geographical location: USA

Setting: inpatient Number of participants: 40 Stroke criteria: unclear Method of stroke diagnosis: unclear Inclusion criteria: unclear Exclusion criteria: unclear Number included in treatment group: 20 Number included in control group: 20 |

Treatment: psychosocial, addresses cognitive, behavioural and family factors associated with post stroke depression

Control: usual care, no visits

Duration: treatment continued for 6 weeks

Administered by: unclear Supervision: unclear Follow‐up: unclear |

|

Results not available |

| Ohtomo 1985 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: tiapride Control arm: placebo | Geographical location: Japan

Setting: unclear

Number of participants: 188

Stroke criteria: all subtypes

Method of stroke diagnosis: diagnosis via clinical signs and CT

Inclusion criteria: 1) > 40 years of age, high blood pressure (> 160/90 mmHg) and hypertensive changes on fundoscopy changes; 2) stable neuroleptic, minor tranquilliser, antidepressant, brain metabolic activators, cerebro‐vasodilators washed out for 3 to 7 days prior to randomisation Exclusion criteria: 1) severe aphasia; 2) severe dementia; 3) drug dependence; 4) inadequate conditions for the study Depression criteria: not reported Number included in treatment group: 141 (54% men, mean age not reported) Number included in control group: 147 (61% men, mean age not reported) |

Treatment: tiapride, 75 mg daily for 1 week, dose escalation to 150 mg to 225 mg daily for 5 weeks according to clinical response Control: matched placebo Duration: 6 weeks |

|

Results not available in format suitable for the review |

| Ostwald 2014 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: home‐based psychoeducational programme Control arm: monthly mailed letter |

Geographical location: USA Setting: outpatient Number of participants: 159 Stroke criteria: stroke <12 months ago, subtype unclear Method of stroke diagnosis: unclear Inclusion criteria: 1) > 50 years of age Exclusion criteria: 1) global aphasia, 2) patient or carer had comorbidity that took priority, 3) < 6 months life expectancy Depression criteria: none Number included in treatment group: 79 (69% men, mean age 67 years) Number included in control group: 80 (81% men, mean age 66 years) |

Treatment: home‐based psychoeducational programme for stroke‐care‐giving dyads post‐discharge. The intervention involved home visits by advance practice nurses, occupational and physical therapists Administered by: advance practice nurses, occupational and physical therapists Supervision: not reported Control: 1 letter a month for 12 months Duration: 6 months Follow‐up: 6 months |

|

Unable to isolate outcome data for non‐ depressed participants at randomisation |

| Raffaele 1996 | Study design: parallel design Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: trazodone Control arm: placebo | Geographical location: Italy Setting: outpatient Number of participants: 22 Stroke criteria: unclear Method of stroke diagnosis: not reported Inclusion criteria: not reported Exclusion criteria: not reported Depression criteria: ZDS Number included in treatment group: 11 (45.4% men, mean age 69.5, SD 2.3) Number included in control group: 11 (72.7% men, mean age 70.4, SD 3.0) | Treatment: trazodone 300 mg/day Control: placebo Duration: 30‐45 days Follow‐up: unclear |

|

Unable to isolate outcome data for non‐ depressed participants at randomisation. |

BI: Barthel Index

CES‐D: Center for Epidemiological Studies‐ Depression

CT: computed tomography

FIM: Functional Independence Measure

GDS: 15‐item Geriatric Depression Scale

GHQ‐12: 12 item General Health Questionnaire

GHQ‐28: 28 item General Health Questionnaire

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

MADRS: Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

mRS: modified Rankin Scale

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

SD: Standard Deviation

SF‐36: 36‐item Short Form Questionnaire

SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

ZDS: Zund Depression Scale

Types of participants

We included all participants with a confirmed history of stroke where there was an explicit intention to provide an intervention to prevent depression associated with stroke. Stroke was defined according to clinical criteria. The criteria included cerebral infarction, intracerebral haemorrhage, and uncertain pathological subtypes, but excluded studies of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) only, which has a different natural history and management strategy to other stroke subtypes. We included studies with small numbers of participants with SAH. We excluded trials that included mixed populations (such as stroke and head injury or other central nervous system disorders) unless separate results for participants with stroke were identified. We excluded participants with a diagnosed depressive disorder or a mood score above the standard cut‐off score for depressive disorder at baseline, but included them in a review of pharmacological, psychological and non‐invasive brain stimulation interventions for treating depression after stroke (Allida 2020). We excluded participants if they were treated primarily for a stroke‐associated pain syndrome or other physical disorder, even if depression was measured as a secondary outcome.

Types of interventions

We included the following interventions.

Comparison between a pharmacological intervention and placebo for the prevention of depression after stroke. Specific pharmacological agents included tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. nortriptyline, imipramine, and clomipramine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g. fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (e.g. moclobemide), and other antidepressant medications. We included psychostimulants (e.g. methylphenidate), mood stabilisers (e.g. lithium), benzodiazepines, and combined preparations, but analysed these separately.

Comparison between psychological therapy and usual care (or attention control) for the prevention of depression after stroke. We included any psychological therapy that involved direct person‐professional interaction. The content of the interaction could vary from counselling to specific psychological therapy, provided it was directed at helping people develop their social problem‐solving skills and adjustment to the emotional impact of stroke. All interventions had to have a psychological component, such as talking, listening, support, advice; be based on a theory of talking therapy; be structured and time‐tabled as a talking therapy; and be delivered by somebody with some explicitly stated training and supervision in therapies.

Comparison between non‐invasive brain stimulation and sham stimulation or usual care for the prevention of depression associated with stroke. We found no trials of non‐invasive brain stimulation interventions. Any future trials will be included but analysed separately.

Alternatively, we included their combinations.

Pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus pharmacological intervention plus usual care and/or attention control.

Pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus placebo plus psychological therapy.

Pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus pharmacological intervention plus sham stimulation or usual care.

Pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus placebo plus non‐invasive brain stimulation.

Non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus non‐invasive brain stimulation plus usual care and/or attention control.

Non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus sham brain stimulation or usual care plus psychological therapy.

Exclusions included the following.

Interventions with an agent or therapy that was being primarily evaluated for other reasons (for example, to improve physical function, provide neuroprotection, or to facilitate neuro‐regeneration) with a mood endpoint.

Interventions with the sole purpose of educating or providing information.

Occupational therapy (including leisure therapy and other rehabilitation services).

Acupuncture or electro‐acupuncture.

Herbal medicines.

Interventions which involved visits from stroke support workers, unless there was a clearly defined psychological component.

Attention control in psychological therapy trials can include non‐specific interventions such as relaxation classes, or follow‐up with a clinician who has no psychological training.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary analyses focus on the proportion of people who met the diagnostic categories of depression that were applied by the authors of the trial, at the end of the treatment period. These included:

meeting the criteria for depression, dysthymia or minor depression as defined by the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IIIR, DSM‐IV, DSM V; APA 1987; APA 1994; APA 2013) or similar standard diagnostic criteria;

scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder, as defined by symptom scores on standard mood rating scales.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were:

depression score, as measured on scales such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS, Hamilton 1960), Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS, Montgomery 1979), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, Gompertz 1993), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck 1961), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS Depression sub‐scale, Zigmond 1983) at the end of treatment/follow‐up;

psychological distress, as measured on composite scales such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ, Goldberg 1972);

general health, as measured on composite scales such as the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP, Hunt 1986);

cognition, as measured on scales such as the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE, Folstein 1975);

social activities, as measured on scales such as the Frenchay Activities Index (FAI, Wade 1985);

activities of daily living, as measured on scales such as the Barthel Index (BI, Mahoney 1965);

disability, as measured on scales such as the Hemispheric Stroke Scale (HSS, Adams 1990);

disadvantages of treatment, recorded as adverse events; grouped by death, all, and leaving the study early (including death).

We examined the reason for participants withdrawing from the studies as a marker of acceptance.

We have identified additional outcomes, where measured, for use in further reviews.

Anxiety, as measured on scales such as the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS Anxiety sub‐scale, Zigmond 1983).

Search methods for identification of studies

This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane Review updated in 2008 (Hackett 2008; Appendix 1). The first published review was in 2004 (Anderson 2004). For this update, we searched all databases from inception until August 2018. We searched for relevant trials in all languages and arranged for translation of trial reports when necessary.

Specialised Register of Cochrane Stroke

See the methods for the Cochrane Stroke Group Specialised register. The Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist searched the Specialised Register of Cochrane Stroke on 13 August 2018.

Electronic searches

We searched the following bibliographic databases.

Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis Trials Register (last searched August 2018)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 8), in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 2)

MEDLINE (OVID):1966 to August 2018 (Appendix 3)

Embase (OVID): 1980 to August 2018 (Appendix 4)

PsycINFO (OVID): 1967 to August 2018 (Appendix 5)

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, CINAHL (EBSCO): 1982 to August 2018 (Appendix 6)

Science Citation Index ‐ Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) in Web of Science (ISI): 2002 to August 2018 (Appendix 7)

Biological Abstracts has now been superseded by ISI Web of Science, which includes the Arts and Humanities Index. Several databases/citation indexes (Applied Science and Technology Plus; Biological Abstracts; BIOSIS Previews; General Science Plus; Dissertations and Theses) listed in Appendix 1 were not used for this update.

We also searched the following ongoing trials registers and registries using 'stroke' or 'brain infarction' or 'depression' or 'low mood' from inception to August 2018.

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform ( WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/)

Searching other resources

In addition, we also searched abstracts and conference proceedings from the following international conferences for relevant studies.

European Stroke Organisation Conference (2015 to 2018)

Stroke Society of Australasia Annual Scientific Meetings (2008 to 2018)

World Stroke Congress (2000 to 2016)

Asia Pacific Stroke Conference (2011 to 2017)

The full search strategies for other resources are presented in Appendix 8.

Personal communication

We contacted the study authors for information on ongoing and 'dropout' trials or to request additional study data and in some instances, additional analyses.

Reference lists

We searched the reference lists of relevant trials, systematic reviews and reviewed chapters in books on the prevention and treatment of depression and management of stroke, including but not limited to, reviews of the management of stroke, books specifically directed at the treatment or prevention of depression, and those on stroke and old age.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

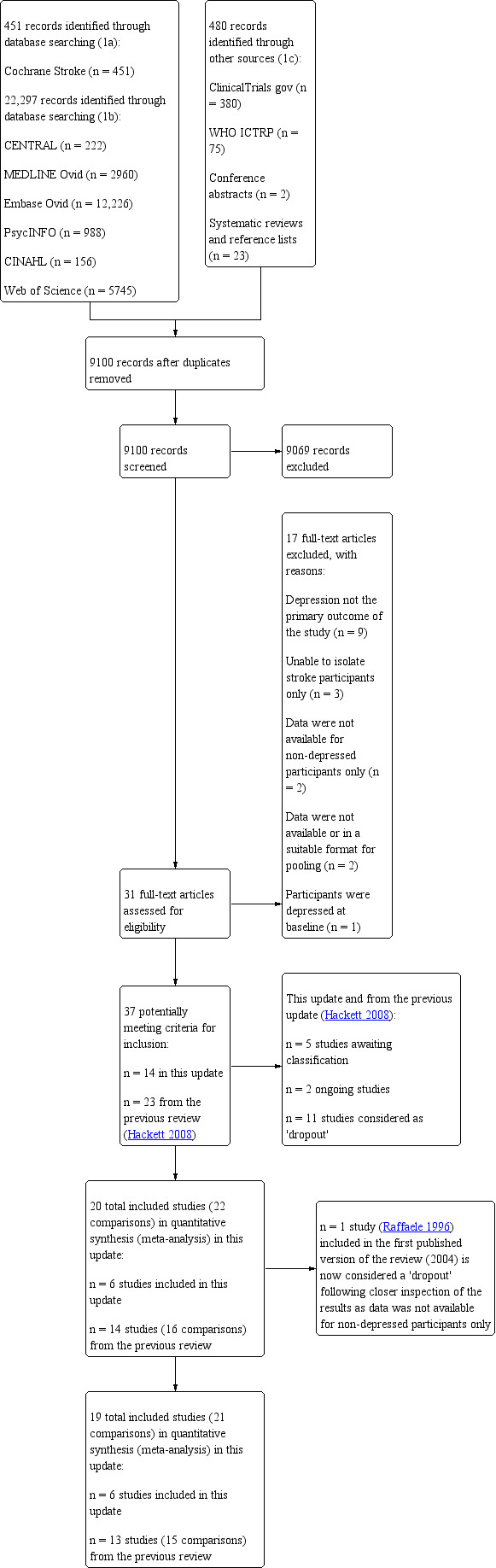

Two review authors (SA, KC) reviewed all citations for this update and discarded those that were irrelevant, based on the title of the publication and its abstract. In the presence of any suggestion that an article was possibly relevant, we retrieved the full‐length article for further assessment. Two review authors (SA, KC) independently selected the trials for inclusion in the review from the culled citation list. Potentially relevant Chinese language articles were translated by another study author (C‐FH). We resolved disagreements by discussion, and MH and AH confirmed the final list and adjudicated any persisting differences of opinion. The selection process is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). We listed the included studies under Characteristics of included studies, and studies that we ultimately excluded under Characteristics of excluded studies and provided the primary reasons for exclusion.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Four review authors (SA, KC, C‐FH, MH) independently extracted the study characteristics and outcome data from studies included in this update, on specially designed forms. We cross‐checked and entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).We resolved disagreements by discussion or through consultation with two other review authors (AH or MH). We obtained missing information from the study authors when possible. Information on funding sources are mentioned in the notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table.

We collected data on:

the report: author, year, and source of publication;

the study: sample characteristics, social demography, definition and criteria used for depression;

the participants: stroke sequence (first ever versus recurrent), social situation, time elapsed since stroke onset, history of psychiatric illness, current neurological status, current treatment for depression, and a history of coronary artery disease;

the research design and features: sampling mechanism, treatment assignment mechanism, adherence, non‐response, and length of follow‐up;

the intervention: type, duration, dose, timing, and mode of delivery;

the effect size: sample size, nature of outcome, estimate and standard error on x dy = SD.

To allow for intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, we sought the data irrespective of adherence, fidelity of the intervention to the protocol, and regardless of whether the participants were subsequently deemed ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow‐up. Where study authors used multiple measures to assess depression, we extracted data from the measure the study authors stated was used to assess the primary outcome. For measures assessing secondary outcomes, we extracted data from the most commonly used measure. Where data for the same trial endpoint were conflicting across multiple publications, we extracted data from the first publication reporting data for that outcome. We checked all the extracted data for agreement between review authors. We obtained missing information from the primary investigators whenever possible. To avoid introducing bias, we obtained this unpublished information in writing, on forms designed for the purpose, and entered it into RevMan.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (SA, KC, C‐FH) independently assessed risk of bias for each new study using the criteria outlined in Section 8.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (MH). Although there are a number of scales devised for assessing the quality of RCTs, there is no convincing evidence that complex and time‐consuming scales are more effective than simple scales (Verhagen 2001). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment: If allocation was performed using opaque envelopes we also categorised this as ’high risk’ as it is not tamper‐proof.

Blinding of participants and personnel: For psychological interventions, we recognise that participants are unlikely to remain blinded however, we also categorised this as ’high risk’.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting: when a published trial protocol was not available we categorised this as unclear risk.

Other bias.

We also provided a quote from the study to justify our judgment in the 'Risk of bias in included studies' table. When considering treatment effects, we have taken into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For all dichotomous outcomes, we calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where appropriate, using random‐effects analyses.

Continuous data

For continuous data, if ordinal scale data appeared to be normally distributed, or if the analysis suggested parametric tests were appropriate, we treated the outcome measures as continuous. If there were at least two trials that reported the same outcomes, then we calculated a mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs across the trials. Where different outcome measures were used, we calculated a standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We predicted that randomisation would occur at the level of the individual participant in most, if not all, trials. Outcomes are reported at the end of treatment, and the end of follow‐up, where data are available. Where trials included two or more active intervention arms and only one control arm (placebo, attention control, or usual care), we compared data from each treatment arm with data from the total number of participants in the control group, divided by the number of active intervention groups. The comparisons are presented as separate trials.

Dealing with missing data

We wrote to the authors of all included, ongoing, and dropout trials requesting data that were unavailable or ambiguous in the published articles. We received responses with additional data from the study authors of four new trials (Hoffman 2015; Kerr 2018; Robinson 2008; Wichowicz 2017). In 2008, we received responses with additional data from authors of two trials (Almeida 2006; Watkins 2007). In 2004 we received responses about six trials (Downes 1995; Forster 1996; Friedland 1992; House 2000; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a; Sitzer 2002). We received a response from one further author, but no additional data had been provided by the time of publication (Rasmussen 2003). We received no responses from the remaining authors. We also wrote to all pharmaceutical companies known to produce, or have a licence to produce, pharmacological interventions in 2004. We received nine replies identifying no new trials, so we did not repeat this in the 2008 or current update.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by examining the study characteristics. We used the I2 statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis (Deeks 2011). If there were at least two trials that reported the same outcomes, we reviewed the data for appropriateness of pooling. We interpreted the amount of heterogeneity as low (0% to 29%), moderate (30% to 49%), substantial (50% to 89%), and considerable (90% to 100%) I2 values. We reported similarities between interventions, participants, design, and outcomes in the included trials subsection.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias by a funnel plot only if there were 10 or more included trials (Higgins 2019), using depression as the outcome of interest. We attempted to avoid language bias by including trials irrespective of language of publication, and translation was performed where needed by native speakers of that language. Review author (C‐FH) translated and extracted data for the Chinese language papers. In some cases, similarities between trial reports indicated the possibility of multiple publications from the same trial. We contacted the authors to check whether the publications were duplicates. In the absence of a response and explicit cross‐referencing, we judged articles to be from the same trial if they met the following criteria: 1) there was evidence of overlapping recruitment sites, study dates, and grant funding numbers, and 2) there were similar or identical reported participant characteristics in the trials.

Data synthesis

We analysed data using Review Manager software and pooled data for meta‐analysis when trials assessed similar treatments and had similar outcomes (Review Manager 2014). We conducted a meta‐analysis using available calculated mean difference (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) for continuous outcomes, and risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes using a random‐effects analyses. In the results we included measures of uncertainty, such as 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and estimates of I2. For all summary statistics in this review, please refer to the effects at the end of intervention, or at the end of follow‐up.

Summary of findings and certainty of the evidence

We also assessed the certainty of evidence according to GRADE (Atkins 2004), by constructing a 'Summary of findings' table for the main outcomes per comparison using the GRADEPro tool (GRADEproGDT 2015; Schünemann 2019). We reported the relevant outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table for each comparison.

These data were available for comparison: (1) pharmacological interventions versus placebo; and (2) one of various forms of psychological therapy versus usual care and/or attention control.

For the comparison 'Pharmacological intervention versus placebo', we reported the certainty of evidence for the following outcomes: meeting the study criteria for depression, scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder, mean depression scores, mean cognition scores, mean activities of daily living scores, and death at the end of treatment.

For the comparison 'Psychological interventions versus usual care and/or attention control', we reported the certainty of evidence for the following outcomes: meeting the study criteria for depression, scoring above cut‐off points for a depressive disorder, mean depression scores, mean psychological distress scores, mean general health scores, mean social activities score, and death at the end of treatment.

We had no data for the remaining comparisons: (3) non‐invasive brain stimulation and sham stimulation or usual care; (4) pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus pharmacological intervention plus usual care and/or attention control; (5) pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus placebo plus psychological therapy; (6) pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus pharmacological intervention plus sham stimulation or usual care; (7) pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus placebo plus non‐invasive brain stimulation; (8) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus non‐invasive brain stimulation plus usual care and/or attention control; and (9) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus sham brain stimulation or usual care plus psychological therapy. See Types of interventions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to undertake subgroup analyses to explore the influence of date of publication, sample size, duration of follow‐up, treatment type, high (over 20%) number of dropouts, and blinded versus unblinded outcome assessors. We performed subgroup analyses by method of assessment and outcome measures used to assess depression, psychological distress, general health, cognition, social activities, activities of daily living (ADL), disability, and anxiety for all comparisons.

If there were at least two trials that reported the same outcomes, we reviewed the data for appropriateness of pooling. If there was definite evidence of heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we explored the potential reasons for the differences by performing subgroup analyses and meta‐regression (Normand 1999). If the heterogeneity could not be explained, we combined the trials using random‐effects analyses with cautious interpretation, or did not combine them at all. Where possible, we performed subgroup analyses to examine the impact of treatment type and duration, and of stroke severity.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to explore the sensitivity of the combined estimate of individual trials by leaving out one study if there was high risk of bias and methodological differences. We then calculated the combined effect of the remaining trials, and compared the results with the combined effect based on all the trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In total, we identified 23,228 records, of these we retrieved 22,297 through database searching. We found 931 additional references by searching other resources. After duplicates were removed, we screened 9100 titles and abstracts and excluded 9069 irrelevant records. We retrieved full‐text reports for the remaining 31 studies. After reading the full‐texts, we excluded 17 studies as they did not meet the review eligibility criteria. We have provided the primary reasons for exclusions in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and Figure 1. We identified two trials that met the inclusion criteria (Hadidi 2014; Kim 2017). However, data were not available for non‐depressed participants only. These trials are considered 'dropouts' (Table 3).

In the previous published version of this review (Hackett 2008), eight trials (Bramanti 1989; Downes 1995; Friedland 1992; Graffingo 2003; Leathley 2003; McCafferty 2000; Ohtomo 1985; Raffaele 1996) met the inclusion criteria but were considered ’dropouts’ as data were not available for non‐depressed participants only (Downes 1995; Raffaele 1996), and were either not available or not in a suitable format for meta‐analysis (Bramanti 1989; Friedland 1992; Graffingo 2003; Leathley 2003; McCafferty 2000; Ohtomo 1985). See Table 3 for a more detailed information on these trials.

We received responses with additional data from authors of three new trials (Kerr 2018; Hoffman 2015; Wichowicz 2017).

Included studies

From the first published version of this review, there were a total of 12 included trials (14 interventions) (Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Forster 1996; Goldberg 1997; Grade 1998; House 2000; Palomaki 1999; Raffaele 1996; Rasmussen 2003; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Roh 1996). We included two trials in the 2008 update (Almeida 2006; Watkins 2007), resulting in 14 included trials (16 interventions), with 1515 participants at entry. Two trials compared two active treatments with placebo (Dam 1996a; Robinson 2000a). We compared data from both treatment arms in these trials with data from half the number of participants in the control groups, and presented the results as two separate studies (Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b). One trial included an attention control (where the time participants in the treatment group spent with a trained therapist was controlled for by attention control participants spending equal time with an untrained volunteer) as well as a control (usual care) group (House 2000). We combined data from the attention control and control group and compared these with data from the treatment group. One trial (Raffaele 1996) included in the first published version of the review (2004) is considered a 'dropout' following closer inspection of the results as data was not available for non‐depressed participants only. More detailed information is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

In this update, we included six new trials with 417 participants (Hoffman 2015; Kerr 2018; Robinson 2008; Tsai 2011; Wichowicz 2017; Xu 2006). In total, 19 trials (21 interventions) involving 1771 participants are included.

Participants

All trials in this review included men and women. The average age of participants ranged from 55 to 73 years. Most of the trials reported the time between stroke and randomisation into the trial, with the range covering 'within three days' to six months. Most of the trials included participants with ischaemic stroke, diagnosed using a combination of standard clinical and computed tomography (CT) criteria. For more detailed information on each included study, please refer to the Characteristics of included studies table.

Interventions

Twelve trials (14 interventions) assessed pharmacological interventions compared to placebo (Almeida 2006; Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Grade 1998; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996; Tsai 2011; Xu 2006), and seven assessed psychological interventions compared to usual care and/or attention control (Forster 1996; Goldberg 1997; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Watkins 2007; Wichowicz 2017). Results from these trials are presented and discussed separately.

There were no trials reporting on the remaining comparisons: (3) non‐invasive brain stimulation and sham stimulation or usual care; (4) pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus pharmacological intervention plus usual care and/or attention control; (5) pharmacological intervention and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus placebo plus psychological therapy; (6) pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus pharmacological intervention plus sham stimulation or usual care; (7) pharmacological intervention and non‐invasive brain stimulation versus placebo plus non‐invasive brain stimulation; (8) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus non‐invasive brain stimulation plus usual care and/or attention control; and (9) non‐invasive brain stimulation and one of various forms of psychological therapy versus sham brain stimulation or usual care plus psychological therapy. (See Types of interventions).

Pharmacological interventions

Among trials of pharmacological interventions, six compared a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) against placebo (fluoxetine: Dam 1996a; Robinson 2000a; sertraline: Almeida 2006; Rasmussen 2003; escitalopram: Robinson 2008), and paroxetine: Xu 2006), one compared a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor against placebo (trazodone: Reding 1986), one compared a tricyclic antidepressant against placebo (nortriptyline: Robinson 2000b), and one compared a serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor against placebo (milnacipran: Tsai 2011). Other treatments with antidepressant effects were used in five trials (piracetam: Creytens 1980; maprotiline: Dam 1996b; mianserin: Palomaki 1999; indeloxazine: Roh 1996), and a psychostimulant (methylphenidate: Grade 1998). Four trials (five interventions) used a fixed dosing regimen (Almeida 2006; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Roh 1996; Xu 2006), and eight (nine interventions) used a flexible (Grade 1998; Rasmussen 2003; Robinson 2008), or escalating (Creytens 1980; Palomaki 1999; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Tsai 2011), regimen. Treatment duration varied from four weeks (Grade 1998; Reding 1986), to 52 weeks (Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Robinson 2008; Tsai 2011).

Psychological therapy

Varying forms of psychological therapy were used in the included trials. Two trials stated explicitly that the intervention was problem‐solving therapy (Forster 1996; House 2000), or cognitive behavioural coping therapy (Hoffman 2015). Two trials provided an intervention that was more broadly defined (home‐based therapy: Goldberg 1997; and solution‐focused brief therapy: Wichowicz 2017), and two provided motivational interviewing (Kerr 2018; Watkins 2007). Five trials used 'usual care' as the control comparison (Forster 1996; Goldberg 1997; Hoffman 2015; Kerr 2018; Watkins 2007), and one used usual care and attention control groups (House 2000). One trial stated that participants in the control comparison did not receive any psychotherapeutic interventions. The interventions were delivered by a variety of trained professionals, including specialist nurses (Forster 1996; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Watkins 2007; Wichowicz 2017), and a mixed team of therapists (Goldberg 1997; Watkins 2007). Treatment duration varied from one visit per week for four weeks (Watkins 2007), to monthly home visits over one year (Goldberg 1997).

Outcomes

Primary outcome: depression

Thirteen assessment scales were used to diagnose the proportion of people meeting the criteria for depression or scoring above the cut‐off points for a depressive disorder in the 19 trials (21 interventions). The most commonly used measures were the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Almeida 2006; Dam 1996a; Dam 1996b; Grade 1998; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Robinson 2000a; Robinson 2000b; Robinson 2008; Tsai 2011), and the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (Hoffman 2015; Kerr 2018; Wichowicz 2017). Seven trials used two or more scales to assess abnormal mood or depression (Grade 1998; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Watkins 2007), and two older trials relied on a clinical or physician assessment (Reding 1986; Roh 1996).

Secondary outcomes

A variety of additional outcomes were assessed in each trial. Several studies assessed and reported outcome data for depression (Almeida 2006; Dam 1996a; Dam 1996b; Grade 1998; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996; Tsai 2011; Watkins 2007; Wichowicz 2017; Xu 2006), psychological distress (House 2000; Watkins 2007), general health (Forster 1996), cognition (Almeida 2006; Grade 1998; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b), social activities (Forster 1996; House 2000), activities of daily living Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Forster 1996; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Reding 1986; Watkins 2007; Xu 2006), disability (Almeida 2006; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Grade 1998; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b), and anxiety (Hoffman 2015; Kerr 2018; Wichowicz 2017). A wide variety of additional measures were used in the trials (see Characteristics of included studies). Although most trials reported data from all the scales and assessments that were stated as used, these data were often not presented in a format that was easily collated for this review. We sought additional data from study authors if possible. Adverse events were reported in many studies (Almeida 2006; Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Grade 1998; House 2000; Palomaki 1999; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996;Tsai 2011; Watkins 2007); however, it was difficult to determine whether recording and reporting of adverse events were systematic. In other studies, adverse events were not reported by randomised group (Reding 1986), or only in a selected manner (Forster 1996; Goldberg 1997; Rasmussen 2003).

Ongoing studies

Two trials are ongoing (Sitzer 2002: pharmacological intervention; Kirkevold 2018: psychological therapy).

Studies awaiting classification

From the previous published version of this review, there were two trials listed as awaiting classification (Evans 1985; Katz 1998). We were unable to obtain more information or outcome data from these trials, despite multiple attempts to contact the study authors. In the present review, there are four additional trials listed as awaiting classification (Chang 2011; IRCT201112228490N1; Ostwald 2014; Razazian 2016). We were unsure if depression was the primary outcome in two trials (IRCT201112228490N1; Razazian 2016). In the other two trials, no information regarding supervision was provided for the psychological therapy component of the intervention to help us determine if they meet our review criteria (Chang 2011; Ostwald 2014).

Dropout studies

In the previous published version of this review (Hackett 2008), seven trials met the inclusion criteria but were considered 'dropouts' as data were not available for non‐depressed participants only (Downes 1995); or were either not available or not in a suitable format for meta‐analysis (Bramanti 1989; Friedland 1992; Graffingo 2003; Leathley 2003; McCafferty 2000; Ohtomo 1985). See Table 3 for more detailed information on these trials.

We identified two new trials that met the inclusion criteria; however, data were not available for non‐depressed participants only (Hadidi 2014; Kim 2017; Ostwald 2014). These trials are considered 'dropouts' (Table 3). One trial (Raffaele 1996) previously included in the first published version of the review (2004) is now considered a 'dropout' following closer inspection of the results as data was not available for non‐depressed participants only.

We contacted the study authors of the dropout studies to request data for non‐depressed participants only. However, we did not receive any responses.

Excluded studies

For this update, we excluded 17 trials at the full‐text review stage. Reasons for exclusion include: 1) depression was not the primary outcome (n = 9); 2) unable to isolate data for stroke participants (n = 3); 3) data were not available for non‐depressed participants at baseline (n = 2); 4) data were not available or in a suitable format for pooling (n = 2) and; 5) participants were depressed at baseline (n = 1). We have listed the excluded studies, and their reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We present a graphical summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments performed by review authors for the included studies, based on the seven risk of bias domains (Figure 2). Figure 3 provides a summary of risk of bias for each included study. The reasons for judgements are provided in the 'Risk of bias' section in Characteristics of included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The randomisation sequence was appropriately generated in 10 trials (Almeida 2006; Goldberg 1997; Grade 1998; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Reding 1986; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996; Wichowicz 2017), thus we rated these as low risk. However, nine trials (11 interventions) did not describe their method of sequence generation; we rated these as unclear risk (Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Forster 1996; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Tsai 2011; Watkins 2007; Xu 2006).

We rated six trials as low risk as an appropriately generated and clearly concealed allocation procedure was used (Almeida 2006; Grade 1998; House 2000; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996; Tsai 2011). Twelve trials (10 interventions) did not describe their method of allocation concealment and so we rated them as unclear risk (Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Forster 1996; Goldberg 1997; Hoffman 2015; Rasmussen 2003; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Wichowicz 2017; Xu 2006). One trial used opaque sealed envelopes (Watkins 2007), while another trial used coloured paper to conceal allocation (Kerr 2018), and one trial used sealed envelopes as their method of allocation concealment (Palomaki 1999), so they were all rated as high risk.

Blinding

Nine trials (10 interventions) reported that participants and personnel were blinded to the treatment allocation and so we rated these as low risk (Almeida 2006; Grade 1998; Palomaki 1999; Rasmussen 2003; Reding 1986; Robinson 2000a/Robinson 2000b; Robinson 2008; Roh 1996; Tsai 2011). Four trials (five interventions) did not provide information about blinding of participants and personnel so we rated them as unclear risk (Creytens 1980; Dam 1996a/Dam 1996b; Forster 1996; Xu 2006). We rated six trials as high risk (Goldberg 1997; Hoffman 2015; House 2000; Kerr 2018; Watkins 2007; Wichowicz 2017): due to the nature of the intervention in these trials, it is very unlikely that the participants and personnel remained blinded to the treatment allocation.