Abstract

Critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia suffered both high thrombotic and bleeding risk. The effect of SARS-CoV-2 on coagulation and fibrinolysis is not well known. We conducted a retrospective study of critically ill patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) a cause of severe COVID-19 pneumonia and we evaluated coagulation function using rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) on day of admission (T0) and 5 (T5) and 10 (T10) days after admission to ICU. Coagulation standard parameters were also evaluated. Forty patients were enrolled into the study. The ICU and the hospital mortality were 10% and 12.5%, respectively. On ICU admission, prothrombin time was slightly reduced and it increased significantly at T10 (T0 = 65.1 ± 9.8 vs T10 = 85.7 ± 1.5, p = 0.002), while activated partial thromboplastin time and fibrinogen values were higher at T0 than T10 (32.2 ± 2.9 vs 27.2 ± 2.1, p = 0.017 and 895.1 ± 110 vs 332.5 ± 50, p = 0.002, respectively); moreover, whole blood thromboelastometry profiles were consistent with hypercoagulability characterized by an acceleration of the propagation phase of blood clot formation [i.e., CFT below the lower limit in INTEM 16/40 patients (40%) and EXTEM 20/40 patients (50%)] and significant higher clot strength [MCF above the upper limit in INTEM 20/40 patients (50%), in EXTEM 28/40 patients (70%) and in FIBTEM 29/40 patients (72.5%)]; however, this hypercoagulable state persists in the first five days, but it decreases ten day after, without returning to normal values. No sign of secondary hyperfibrinolysis or sepsis induced coagulopathy (SIC) were found during the study period. In six patients (15%) a deep vein thrombosis and in 2 patients (5%) a thromboembolic event, were found; 12 patients (30%) had a catheter-related thrombosis. ROTEM analysis confirms that patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia had a hypercoagulation state that persisted over time.

Highlights

Severe COVID-19 pneumonia had an hypercoagulation state that persists over time

Standard coagulation profile may not highlight the severe thrombotic state of COVID-19 patients

Further studies are needed to confirm these data based on evaluation in vivo fibrinolysis and to establish antithrombotic regime

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an evolving pandemic. Approximately one-fifth of the infected individuals develops severe to critical disease requiring intensive care support a cause of pneumonia [1]. As recent literature data described, severe COVID-19 is commonly complicated with coagulopathy with elevated D-dimer [1–4]; moreover, a pooled analysis showed that D-dimer values are considerably higher in COVID-19 patients with severe disease than those without [5].

Viral acute infections are associated with a procoagulant state, and the resultant hypercoagulability may in severe cases accelerate leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [6]. The excessive activation of coagulation involves consumption of platelets and coagulation factors, which may shift the hypercoagulant state into a hypocoagulant state [6].

Conventional coagulation and fibrinolytic tests, as prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and D-dimer value, only reflect limited parts of the coagulation system [7].

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) is point-of-care device that evaluate viscoelastic changes during coagulation [8], and it provides detailed information on clotting kinetics from clot formation through degradation [9]. Recently, there has been a growing interest in its use either to study hypo [10] as well as hypercoagulable conditions [11].

Until now, the effect of COVID-19 infection on haemostatic functions remains unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate consequences of severe COVID-19 infection on global haemostasis using standard coagulation parameters and whole blood ROTEM over time.

Methods

This single-centre, retrospective, observational study was done at Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit (ICU), Santa Maria Annunziata Hospital (Bagno a Ripoli, Tuscany, Italy), which is one of the designated hospitals to the Tuscany Region to treat patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Forty consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with severe COVID-19 admitted to ICU between February 28, 2020 (i.e., when the first patient was admitted), and 10 April 2020, were retrospectively enrolled.

The diagnosis of severe COVID-19 pneumonia was according to World Health Organization (WHO) [12] interim guidance and it was confirmed by RNA detection of the SARS-CoV-2 in clinical laboratory of Santa Maria Annunziata Hospital (Bagno a Ripoli, Italy).

The Ethics Commission of Area Vasta Centro (Tuscany, Italy) approved this retrospective study. Written informed consent was waived due to the emergence of this infectious disease in Italy.

Demographic and clinical information were collected, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), preexisting illness (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), onset of symptom to hospital admission and to ICU admission, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) on ICU admission, PaO2/FiO2 on ICU admission, need to non-invasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation, total length of ICU and hospital stay, and ICU and hospital mortality. The Sepsis Induced coagulopathy (SIC) score system including prothrombin time (PT), platelet count and SOFA was calculated and a SIC criteria total score ≥ 4 was considered, as suggested by International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [13].

At the time of admission (T0) and 5 (T5) and 10 (T10) days later, peripheral venous blood sample was taken and routine blood examinations with hemoglobin level, platelet count, coagulation parameters including PT, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen levels, D-dimer values, antithrombin III, interleukin-6 (IL-6), procalcitonin, were collected. An additional venous blood sample was placed into citrate-containing tubes (BD Vacutainer®; BD Plymouth, UK) and analyzed by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM® gamma; Tem Innovations GmbH, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation cascades were evaluated by using the EXTEM and INTEM tests, respectively. The influence of fibrinogen on clot firmness was estimated by using the platelet inactivating FIBTEM test. The following ROTEM® parameters were analyzed: 1) clotting time (CT, s), time from the beginning of the coagulation analysis until an increase in amplitude of thromboelastogram of 2 mm; 2) clot formation time (CFT, s), time between an increase in amplitude of thromboelastogram from 2 to 20 mm; 3) A5 and A10, clot strength at 5 and 10 min, 4) maximum clot firmness (MCF, mm) or the maximum amplitude (mm) reached in the thromboelastogram and 5) maximum lysis (ML, %), measure of fibrinolysis.

All patients received antiviral and appropriate supportive therapies on the day of the admission and throughout the hospital stay.

Thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH, 40–60 mg enoxaparin/day) was used in according to guidelines of Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2016 [14].

Bilateral extended compression ultrasound (ECUS) from common femoral vein through the popliteal vein up to the calf veins confluence was performed in each of the included patients on day of admission and five days after, using GE Logiq-e1 Vision scanner (GE, Healthcare, Italy). Moreover, at the same time, ultrasound screening was helpful for detecting catheter-related thrombosis.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage), wherever appropriate. Normally distributed data were compared by Student’s t-tests. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software version 25.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Forty patients were enrolled into the study. The mean age was 61 ± 13 years; most of them were male (60%). Sixteen patients (40%) had two chronic underlying diseases, including hypertension and diabetes. On admission, the mean of SOFA was 4 ± 1 and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 156 ± 50. Four patients died in the ICU (10%) and one patient died during hospitalization, after ICU discharge. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of studied patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

| Total patients (n = 40) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 61 ± 13 |

| Sex | |

| Male n(%) | 24 (60) |

| Female, n (%) | 16 (40) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 4.7 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 16 (40) |

| Diabetes | 16 (40) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (30) |

| COPD | 4 (10) |

| Onset of symptoms to: | |

| Hospital admission (days) | 9.4 ± 1.6 |

| ICU admission (days) | 11.6 ± 4 |

| SOFA score on ICU admission | 4 ± 1 |

| PaO2/FiO2 on ICU admission | 156 ± 50 |

| Non invasive ventilation, n (%) | 36 (90) |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 4 (10) |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 8 ± 2.3 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 22.3 ± 5.5 |

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 4 (10) |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 5 (12.5) |

Data are expressed by mean ± SD or number (percentage)

Among standard coagulation parameters, on admission, PT value was slightly reduced and it increased significantly at T10 (T0 = 65.1 ± 9.8 vs T10 = 85.7 ± 1.5, p = 0.002); moreover, aPTT value was normal and it decreased at T10 ( 32.2 ± 2.9 vs 27.3 ± 2.1, p = 0.017). Platelet count was normal and increased over time. Fibrinogen value was greatly increased in all patients and, subsequently, it decreased (T0 = 895.7 ± 110 vs T10 = 332.5 ± 50, p = 0.002). On ICU admission, 28 patients (70%) had a D-dimer value above the upper limit of normal range (Table 2). D-dimer value at T10 was lower than T0, even if not statistically significant (p = 0.392). AT levels remained in the normal value and none of the patients receiving AT concentrate supplementation.

Table 2.

Laboratory characteristics of COVID-19 pneumonia patients during follow-up period

| T0 (n = 40) | T5 (n = 40) | T10 (n = 33) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (gr/dL) | 11.4 ± 2.4 | 11.4 ± 1.9 | 11.4 ± 2.3 | 0.460 |

| Platelet count, × 109 per L | 317.5 ± 168 | 461 ± 200.9 | 486.6 ± 335 | 0.068 |

| Prothrombin time (PT), % | 65.1 ± 9.8 | 74.4 ± 8.5 | 85.7 ± 1.5 | 0.002* |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), s | 32.2 ± 2.9 | 28.4 ± 2.7 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 0.017* |

| ATIII, % | 87.2 ± 13.5 | 114.7 ± 23.2 | 98 ± 15.2 | 0.097 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 895.7 ± 110 | 496.5 ± 32 | 332.5 ± 50 | 0.002* |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 1556 ± 1090 | 1122 ± 311 | 752 ± 110 | 0.392 |

| Il-6, pg/ml | 108.4 ± 91.1 | 50.3 ± 41 | 16.6 ± 30.8 | 0.017* |

| Procalcitonin, µg/L | 0.52 ± 0.25 | 0.28 ± 0.17 | 0.38 ± 0.2 | 0.078 |

| SIC score (≥ 4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

Data are expressed by mean ± SD or percentage

*p value < 0.05, between T0 and T10

Bio humoral parameters at T0 showed high level of IL-6 that resulted significantly reduced at T10 (108.4 ± 91.1 vs 16.6 ± 30.8, p = 0.017). Procalcitonin was not increased (0.52 ± 0.25 vs 0.38 ± 0.2) in the follow-up period (Table 2).

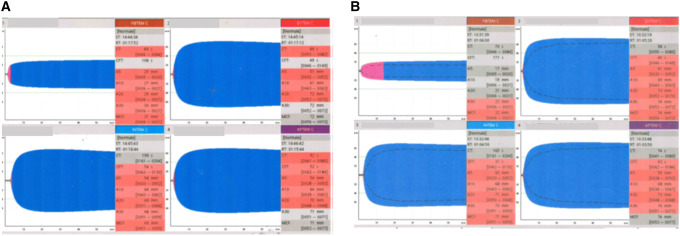

ROTEM analysis showed normal CT and CFT mean values both INTEM and in EXTEM, but MCF in FIBTEM higher than normal (35.9 ± 5.9) (Table 3). Sixteen patients (40%) and 20 (50%) had CFT values lower than the lower limit of the normal range in INTEM and EXTEM, respectively; moreover, 29 (72.5%) showed a value of MCF in FIBTEM above the upper limit of normal range (Table 4). Figure 1 showed typical ROTEM tracings in a patient with a COVID-19 pneumonia, on ICU admission and on ICU discharge.

Table 3.

ROTEM parameters at T0, T5 and T10

| Reference | T0 (n = 40) | T5 (n = 40) | T10 (n = 33) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTEM | |||||

| CT, s | 100–240 | 174.6 ± 26.2 | 181 ± 20 | 166 ± 8.1 | 0.383 |

| CFT, s | 30–110 | 38.8 ± 12.1 | 24.3 ± 18.6 | 37 ± 3.1 | 0.405 |

| A5, mm | 38–57 | 61.4 ± 9.5 | 65.3 ± 2.5 | 63.5 ± 5.7 | 0.709 |

| A10, mm | 44–66 | 70 ± 7.6 | 75.6 ± 2 | 70.3 ± 3.3 | 0.187 |

| MCF, mm | 50–72 | 74.5 ± 6.9 | 75.7 ± 2.1 | 79.5 ± 13.3 | 0.189 |

| EXTEM | |||||

| CT, s | 38–79 | 78.3 ± 17.2 | 78.7 ± 14 | 64.5 ± 5.8 | 0.229 |

| CFT, s | 34–159 | 41.6 ± 11.4 | 37.6 ± 3.2 | 36.3 ± 5.3 | 0.434 |

| A5, mm | 34–55 | 63.2 ± 8.5 | 67.3 ± 3.2 | 63.8 ± 5 | 0.766 |

| A10, mm | 43–65 | 71.4 ± 7.5 | 74 ± 2 | 71 ± 2 | 0.567 |

| MCF, mm | 50–72 | 76.6 ± 6.4 | 77.3 ± 0.6 | 73.5 ± 3.5 | 0.471 |

| ML % 60 | 9.4 ± 6.6 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 5 ± 1.2 | 0.028* | |

| FIBTEM | |||||

| MCF, mm | 9–25 | 35.9 ± 5.9 | 32.3 ± 8.3 | 23 ± 3.3 | 0.017* |

*p value < 0.05 between T0 and T10

Table 4.

Patients observation based on ROTEM values (lower and upper normal range limits) during follow-up period

| Lower/upper limits | T0 (n = 40) | T5 (n = 40) | T10 (n = 33) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTEM | ||||

| CFT, patients (%) | ≤ 30 | 16/40 (40%) | 12/40 (30%) | 6/33 (18.1%) |

| MCF, patients (%) | ≥ 72 | 20/40 (50%) | 24/40 (60%) | 9/33 (27.2%) |

| EXTEM | ||||

| CFT, patients (%) | ≤ 34 | 20/40 (50%) | 8/40 (2%) | 9/33 (27.2%) |

| MCF, patients (%) | ≥ 72 | 28/40 (70%) | 27/40 (67.5%) | 6/33 (18.1%) |

| FIBTEM | ||||

| MCF, patients (%) | ≥ 25 | 29/40 (72.5%) | 24/40 (60%) | 3/33 (9%) |

Fig. 1.

Typical ROTEM tracings in a patients with a COVID-19 pneumonia. a on ICU admission b on ICU discharge

In six patients (15%), a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and in two patients (5%) a thromboembolic event, were found; 12 patients (30%) had a catheter-related thrombosis. None of patients meet the SIC criteria.

Discussion

In our study the whole blood thromboelastometry profiles of critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were consistent with hypercoagulability characterized by an acceleration of the propagation phase of blood clot formation (i.e., reduction of CFT in INTEM and EXTEM) and significant higher clot strength (i.e., increase in MCF in INTEM, EXTEM and FIBTEM); however, this hypercoagulable state persists in the first days, but it decreases over time. No sign of secondary hyperfibrinolysis at ROTEM analysis was found during the study period.

ROTEM technology provides a rapid and dynamic assessment of haemostasis in vitro. It is emerging as a quick, portable, and well-validated device for clinicians in making an early diagnosis of a specific coagulopathy and a decision of the most appropriate treatment [15]. ROTEM also measures hypercoagulability in various clinical scenarios including major surgery, malignancy, which is not detected by routine coagulation tests [16].

Sepsis-induced coagulopathy is characterized by a predominant activation of the tissue factor pathway with a remarkable consumption of coagulation factors, platelet activation and fibrinolysis [17, 18]. However, traditional coagulation tests (i.e. prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, platelet count) have shown several limitations in their ability to reliably and consistently detect coagulation disorders in sepsis [19].

Severe COVID-19 may be complicated with DIC or SIC; development of SIC would lead to secondary hyperfibrinolysis associated to lengthening to PT, reduction of platelet count and fibrinogen level [3]. Tang et al. [3] reported 11.5% mortality in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and noted that 71.4% of non-survivor patients had abnormal coagulation profile consistent with DIC. A meta-analysis [20] found that a low platelet count was associated with over fivefold increased risk of severe disease (OR, 5.1; 95% CI 1.8–14.6) and an even lower platelet count was associated with mortality in those patients. In our study, laboratory tests did not show a significant alteration of hemostatic parameters such as PT and aPTT; platelet count and fibrinogen values were high over time.

However, 15% of patients presented DVT confirmed by ultrasonography and two patients presented an incidental thromboembolic event documented with pulmonary computer tomography at hospitalization; moreover, 30% of patients suffered from related catheter thrombosis. Klok et al. [21] have found in a population of 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, a DVT incidence of 27% and 81% of pulmonary embolism (PE). Probably, our lower incidence of DVT than Klok was correlated to the lower number of patients included in the study. Moreover, in our study two cases of PE were incidental; therefore, we cannot really establish the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in these patients.

In our patient population we found a significative increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 as well as sepsis induced organ disfunction. Recent evidence showed that “cytokine storms” triggered by COVID-19 infection can cause clotting disorders which may increase the risk of thromboembolism [1]. Sepsis is considered a risk factor for VTE, including upper and lower extremity DVT and PE [22]. The underlying pathogenesis of VTE in sepsis remains incompletely understood but is believed to be the result of multiple factors. In addition to risk factors for hypercoagulability, as originally described by Virchow, incorporating the three original triad (stasis, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulability), severe inflammation observed in patient with sepsis and/or septic shock represents the fourth factor for thromboembolic complications [23]. Inflammation increases pro-coagulant factors, and inhibits natural anticoagulant pathways and fibrinolytic activity, leading to DVT and PE [22]. In fact, the inflammatory process initiated by septic shock may be strained by coexisting tissue hypoxia and systemic inflammation leading to endothelial damages and DVT complications.

In our study the ROTEM analysis showed that an inflammatory state was associated with a state of severe hypercoagulability rather than a consumption coagulopathy; indeed, six patients presented DVT. Probably, standard coagulation parameters fail to highlight the severity of prothrombotic phenotype. ROTEM analysis in addition hypercoagulability can detect impairment in fibrinolysis, expressed as increased lysis indices; coagulation profiles observed in our study population allowed us to conclude that we have not found secondary hyperfibrinolysis condition.

Further randomized studies, based on evaluation in vivo fibrinolysis, are needed to establish whether patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, could benefit of an early anticoagulant therapy, in terms of improving clinical outcomes, in the balance between prothrombotic and hemorrhagic risks.

Acknowledgements

We express our closeness to the patients and their families, and we thank all the nursing staff of Intensive Care Unit of Santa Maria Annunziata Hospital who made it possible to treat patients in this pandemic.

Author contributions

VP and LG conceived the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. MP, CS, TM performed thromboelastometry. FCF collected the data. All authors reviewed data and manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhun. China Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhun, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;2020(18):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin S, Huang M, Li D, Tang N. Difference of coagulation features between severe pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV-2 and non-SARS-CoV2. J Thromb Thrombol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a pooled analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi M. The coagulant response in sepsis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:627–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brummel KE, Paradis SG, Butenas S, Mann KG. Thrombin functions during tissue factors-induced blood coagulation. Blood. 2002;100:148–152. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganter MT, Hofer CK. Coagulation monitoring: current techniques and clinical use of viscoelastic point-of-care coagulation devices. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1366–1375. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318168b367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen MG, Hvans CL, Tonnesen E, Hvas AM. Thromboelastometry as a supplementary tool for evaluation of haemostasis in severe sepsis and septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:525–533. doi: 10.1111/aas.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair SC, Dargaud Y, Chitlur M, Srivastava A. Tests of global haemostasis and their applications in bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2010;16:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiezia L, Marchioro P, Radu C, et al. Whole blood coagulation assessment using rotation thromboelastogram thromboelastometry in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008;19:355–360. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328309044b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. 2000. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. Published January 28.

- 13.Iba T, Levy JH, Warkentin TE, Thachil J, van der Poll T, Levi M. Diagnosis and management of sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(11):1989–1994. doi: 10.1111/jth.14578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Int Care Med. 2017;43:304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt H, Stanworth S, Curry N, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) for trauma induced coagulopathy in adult trauma patients with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;16(2):010438. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010438.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akay OM. The double hazard of bleeding and thrombosis in hemostasis from a clinical point of view: a global assessment by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(6):850–858. doi: 10.1177/1076029618772336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhainaut JF, Shorr AF, Macias WL, et al. Dynamic evolution of coagulopathy in the first day of severe sepsis: relationship with mortality and organ failure. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:341–348. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000153520.31562.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller MC, Meijers JCM, Vroom MB, Juffermans NP. Utility of thromboelastography and/or thromboelastometry in adults with sepsis: a systemic review. Crit Care. 2014;18:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kollef MH, Eisenberg PR, Shannon W. A rapid assay for the detection of circulating D-dimer is associated with clinical outcomes among critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1054–1060. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199806000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan D, Casper TC, Elliott CG, et al. VTE incidence and risk factors in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest. 2015;148:1224–1230. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holley AD, Reade MC. The ‘procoagulopathy’ of trauma: too much, too late? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19:578–586. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]